Abstract

目的

分析酯酰辅酶A合成酶长链家族成员4(ACSL4)在肝癌中的表达,探究铁死亡调控ACSL4对癌细胞增殖能力的影响。

方法

收集肝癌和癌旁正常肝组织临床样本,HE染色病理学鉴定后,微量法检测丙二醛(MDA)含量,RT-qPCR检测ACSL4与增殖细胞核抗原 (PCNA)的mRNA表达,Western blotting检测ACSL4与PCNA的蛋白表达。体外培养Huh-7人肝癌细胞,先分为3组:即铁死亡诱导剂Erastin组、抑制剂 Fer-1组、以及Erastin 与Fer-1联合作用组;其中Erastin或Fer-1组均包含0、20、40、60、80、100 μmol/L共6个浓度,然后采用筛选的Erastin 浓度80 μmol/L+(0、30、60、90 μmol/L)Fer-1,筛选Fer-1浓度后再分为3组:对照组、80 μmol/L Erastin单独处理组、80 μmol/L Erastin+60 μmol/L Fer-1联合处理组,均作用48 h。干预ACSL4、PCNA的表达后,平板克隆实验检测细胞增殖能力的改变,微量法检测MDA含量的变化。

结果

相较于癌旁正常肝组织,肝癌组织中MDA含量降低(P<0.01),ACSL4、PCNA的mRNA和蛋白表达均显著增强(P<0.05);Erastin可抑制ACSL4、PCNA的mRNA和蛋白表达(P<0.01),并抑制细胞增殖(P<0.001)、上调MDA含量(P<0.01);单独使用Fer-1对细胞存活率无影响;但加入Erastin后再应用Fer-1,则可逆转Erastin对ACSL4、PCNA表达(P<0.05),细胞增殖能力的抑制(P<0.001),MDA含量的上调(P<0.05)。

结论

ACSL4在肝癌中表达增强,Erastin可提高MDA含量、下调ACSL4表达,诱导肝癌细胞铁死亡,抑制癌细胞增殖;Fer-1则可逆转Erastin的上述作用。

Keywords: 肝癌, 细胞增殖, Erastin, ACSL4, 铁死亡

Abstract

Objective

To investigate the expression of Acyl-CoA synthetase long-chain family member 4 (ACSL4) in liver cancer and its role in regulating ferroptosis and proliferation of liver cancer cells.

Methods

Clinical samples of liver cancer and adjacent normal liver tissues were examined for malondialdehyde (MDA) contents and for expressions of mRNA and protein expressions of ACSL4 and proliferating cell nuclear antigen (PCNA) using RT-qPCR and Western blotting. Human liver cancer Huh-7 cells were treated with Erastin (a ferroptosis inducer), Fer-1 (a ferroptosis inhibitor), or both, and the changes in expression levels of MDA, ACSL4 and PCNA were detected, and the cell proliferation was assessed with plate cloning assay.

Results

MDA contents were lower and ACSL4 and PCNA expressions were higher significantly in liver cancer tissues than in adjacent liver tissues. In Huh-7 cells, Erastin treatment significantly inhibited mRNA and protein expressions of ACSL4 and PCNA, suppressed cell proliferation, and increased MDA contents. Fer-1 alone did not produce significant effect on cell viability but reversed the effect of Erastin on ACSL4 and PCNA expressions, cell proliferation and MDA contents.

Conclusion

ACSL4 level is significantly overexpressed in liver cancer. Erastin increases MDA contents and down-regulates ACSL4 expression, thereby promoting ferroptosis and inhibiting proliferation of liver cancer cells, and these effects can be reversed by Fer-1.

Keywords: liver cancer, cell proliferation, Erastin, Acyl-CoA synthetase long-chain family member 4, ferroptosis

全球癌症中肝癌位居发病率第6,死亡率第3[1]。当前的治疗手段有手术切除、放射治疗、化学治疗以及介入治疗等[2],但大多数肝癌患者确诊时往往已经处于治疗效果和预后相对较差的中晚期,还容易出现耐药、转移、复发,生存预后差等问题[3-6]。因此,从分子层面去探究肝癌的发生机制,寻找新靶点,可能为其防治提供新的思路和方向。

铁死亡属于一种受铁依赖性调节的细胞死亡形式[7, 8],其主要特征涉及铁积累增加、脂质修复系统受损和脂质过氧化等,最终致使细胞膜被破坏并引发细胞死亡。近年研究[9-12]显示,促进铁死亡发生的同时具有克服传统癌症治疗药物耐药的明显优势。靶向诱导癌细胞铁死亡可能成为一种新的肿瘤治疗手段[13, 14],但具体机制尚不明确。铁死亡包括抑制和激活两条通路[15, 16]。抑制通路中胱氨酸/谷氨酸逆向转运体向细胞内1∶1转入胱氨酸,胱氨酸一旦进入细胞,可被氧化成半胱氨酸,进一步经还原型烟酰胺腺嘌呤二核苷酸磷酸合成谷胱甘肽,谷胱甘肽过氧化物酶4将脂质过化物还原为脂质醇[17, 18]。而激活通路中酯酰辅酶A合成酶长链家族成员4(ACSL4)和溶血磷脂酰基转移酶3,可将多不饱和脂肪酸整合进入磷脂,进而形成含有多不饱和脂肪酸的磷脂,易受脂氧合酶介导的自由基诱发的脂质过氧化,在诱导铁死亡中发挥重要作用[19, 20]。其中ACSL4可将辅酶A插入多不饱和脂肪酸,催化形成脂肪酰基辅酶A,从而导致脂质过氧化,使细胞发生铁死亡[21, 22]。

已有报道[13]提示肝癌的发生发展与铁死亡的关系密切,但铁死亡诱导剂Erastin与抑制剂Fer-1如何经ACSL4调控肝癌细胞增殖?具体机制迄今尚未阐明。本研究从临床组织和体外细胞实验,探究Erastin与Fer-1对ACSL4表达的调控,以明确ACSL4在肝癌中的作用。

1. 材料和方法

1.1. 材料

1.1.1. 肝癌组织样本

收集的临床样本取自2023年3月~2024年2月在桂林医学院第二附属医院接受手术治疗的肝癌患者,分为两组,即肝癌组织和癌旁正常肝组织。其中一份用4%多聚甲醛固定,另一份则保存至-80 ℃冰箱备用。所有样本采集通过桂林医学院伦理委员会批准(伦理批号:GYLL2022025)。

1.1.2. 细胞株

Huh-7人肝癌细胞株购自中国科学院上海细胞库,由本实验室保存。

1.1.3. 主要试剂

丙二醛(MDA)检测试剂盒、超敏ECL化学发光试剂盒、高糖DMEM培养基、Trizol、RT-qPCR上下游引物、BeyoFast™ SYBR Green qPCR Mix (2×)(上海生工生物工程股份有限公司);逆转录试剂盒、结晶紫(上海碧云天生物技术有限公司);兔抗PCNA一抗、4%多聚甲醛(沈阳万类生物科技有限公司);小鼠抗β-actin一抗(北京中杉金桥生物技术有限公司);兔抗ACSL4一抗、山羊抗兔 IgG、山羊抗小鼠IgG(武汉ABclonal生物科技有限公司);Erastin、Fer-1、CCK-8试剂盒(上海陶术生化科技有限公司)。

1.2. 方法

1.2.1. HE染色

通过收集临床组织样本,制备好切片,将组织切片放于二甲苯中脱蜡10 min,梯度乙醇水化;室温苏木精染色2 min,自来水冲洗后,观察染色情况;室温下伊红染色1 min,观察染色情况;之后用梯度乙醇脱水,然后放入二甲苯中使其透明;再用中性树胶封片,显微镜下观察结果。

1.2.2. 细胞培养及分组

采用高糖DMEM培养基体外培养Huh-7人肝癌细胞,先分为3组:即铁死亡诱导剂Erastin组、抑制剂Fer-1组、Erastin与Fer-1联合作用组;其中Erastin或Fer-1组均包含0、20、40、60、80、100 μmol/L共6个浓度,然后采用80 μmol/L Erastin+(0、30、60、90 μmol/L)Fer-1;之后实验则分为3组:对照组、80 μmol/L Erastin单独处理组、80 μmol/L Erastin+60 μmol/L Fer-1联合处理组,均作用48 h。

1.2.3. MDA含量检测

称取约0.1 g组织或收集5×106个细胞收集到离心管,加入1 mL提取液进行冰浴、匀浆,8500 r/min、4 ℃,10 min,取上清,置冰上待测。后续步骤严格按照试剂盒说明书操作,最后按照公式计算MDA含量。

1.2.4. Western blotting实验

剪切各组肝组织或收集各组细胞,在冰上裂解提取蛋白。上样,电泳80 V,约30 min,120 V电泳约1h,后转至PVDF膜2 h。室温5%脱脂牛奶封闭约1 h,分别加入兔抗ACSL4、PCNA一抗、小鼠抗β-actin一抗(稀释比均为1∶1000),4 ℃孵育过夜。次日取出,TBST洗3次,加入对应的山羊抗兔或抗小鼠二抗(稀释比均为1∶5000),室温孵育1 h,通过显影液在显影仪中显影。

1.2.5. RT-qPCR

剪切各组肝组织以及收集各组细胞,通过Trizol法在冰上提取总RNA,随后用逆转录试剂盒将RNA逆转录成cDNA,加入对应引物配制成qPCR反应体系,置荧光定量PCR仪中反应。引物序列ACSL4(人)F:5'-CATCCCTGGAG CAGATACTCT-3',R:5'-T CACTTAGGATTTCCCTG GTCC-3';PCNA(人)F:5'-CCTGCTGGGATATTAG CTCCA-3',R:5'-CAGCGG TAGGTGTCGAAGC-3';GAPDH(人)F:5'-TGCAC CACCACTGCTTAGC-3',R:5'-GGCATGGACTGTG GTCATGAG-3'。

1.2.6. CCK-8检测细胞增殖能力

将Huh-7细胞按5×103/孔接种于96孔板,每组设4~6个复孔,将仅有相同体积培养基而无细胞的孔作为空白对照组。分别加入不同浓度的Erastin、Fer-1培养48 h。避光,每孔加入CCK-8检测试剂孵育,置酶标仪上测吸光度,计算IC50。

1.2.7. 平板克隆实验

将Huh-7细胞分组处理48 h后,胰酶消化并重悬,按1×103/孔接种于6孔板中,置于细胞培养箱,待细胞贴壁。观察细胞生长情况,继续培养7~14 d后取出。4%多聚甲醛固定30 min后弃除,结晶紫染色15 min,PBS清洗多余染料,倒置晾干后观察拍照。

1.2.8. 统计学方法

使用 GraphPad Prism 9.0、Image J和SPSS 26.0软件进行图表分析,数据处理采用均数±标准差表示,使用独立样本t检验进行两组间比较,单因素方差分析用于多组间比较,P<0.05表示差异具有统计学意义。

2. 结果

2.1. 临床肝组织HE染色及MDA含量检测

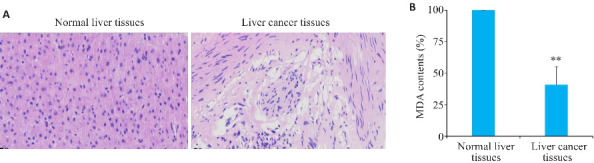

HE染色结果显示,肝癌组织样本的细胞核形状不规则,且排列紊乱,细胞核质比明显增大,细胞出现空泡化,且有癌巢(图1A)。相较于癌旁正常肝组织,肝癌组织中作为铁死亡检测指标之一的MDA含量降低(P<0.01,图1B)。

图1.

临床肝组织HE染色及MDA含量检测

Fig.1 HE staining and MDA contents detection in liver cancer and adjacent tissues. A: HE staining (Original magnification: ×40). B: MDA contents in the tissues (n=6). **P<0.01 vs Normal liver tissues.

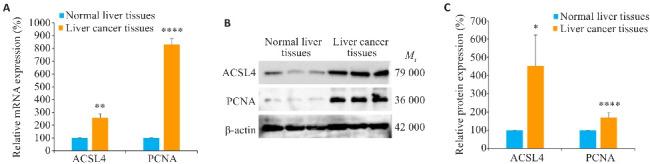

2.2. 临床肝组织中ACSL4、PCNA的mRNA和蛋白表达

RT-qPCR结果表明,与癌旁正常肝组织相比,肝癌组织中ACSL4与PCNA的mRNA表达均呈增强(P<0.01,图2A);Western blotting的检测结果进一步显示,ACSL4与PCNA的蛋白表达增强(P<0.05, 图2B、C)。

图2. 临床肝组织中ACSL4、PCNA的mRNA和蛋白表达.

Fig.2 mRNA and protein expressions of ACSL4 and PCNA in liver cancer and adjacent tissues. A: mRNA expressions of ACSL4 and PCNA in liver cancer and adjacent tissues detected by RT-qPCR. B: Protein expressions of ACSL4 and PCNA in the tissues detected by Western blotting. C: Relative protein expression levels. *P<0.05, **P<0.01,****P<0.0001 vs Normal liver tissues.

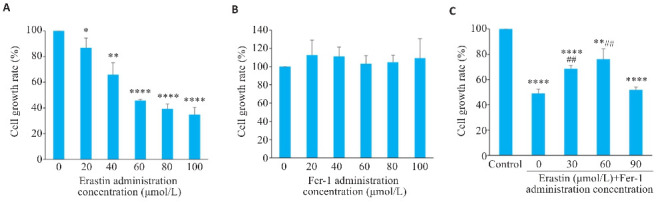

2.3. 铁死亡调控对Huh-7细胞活力的影响

CCK-8检测结果显示,与0 µmol/L Erastin相比,铁死亡诱导剂Erastin对Huh-7细胞增殖的抑制作用呈浓度依赖性增强,计算IC50为75 µmol/L(P<0.05,图3A),故后续实验采用80 µmol/L作为Erastin的给药浓度。单独使用铁死亡抑制剂Fer-1处理Huh-7细胞,对细胞活力的抑制作用不明显(图3B);但采用80 μmol/L Erastin处理后的Huh-7细胞加入0、30、60、90 μmol/L Fer-1,发现与对照组或与Erastin单独用药组(即图中0 μmol/L Fer-1)相比,则表现为Fer-1可以逆转 Erastin 对 Huh-7 细胞增殖能力的抑制(P<0.01,图3C),以浓度60 µmol/L时效果最为明显。

图3.

铁死亡调控对Huh-7细胞活力的影响

Fig.3 Effects of Erastin and Fer-1 on viability of Huh-7 cells assessed using CCK-8 assay. A: Effects of different concentrations of Erastin on viability of Huh-7 cells (*P<0.05, **P<0.01, ****P <0.0001 vs 0 µmol/L). B: Effects of different concentrations of Fer-1 on viability of Huh-7 cells. C: Effects of Erastin combined with Fer-1 on viability of Huh-7 cells (**P<0.01, ****P<0.0001 vs Control; ## P<0.01 vs 0 µmol/L Fer-1).

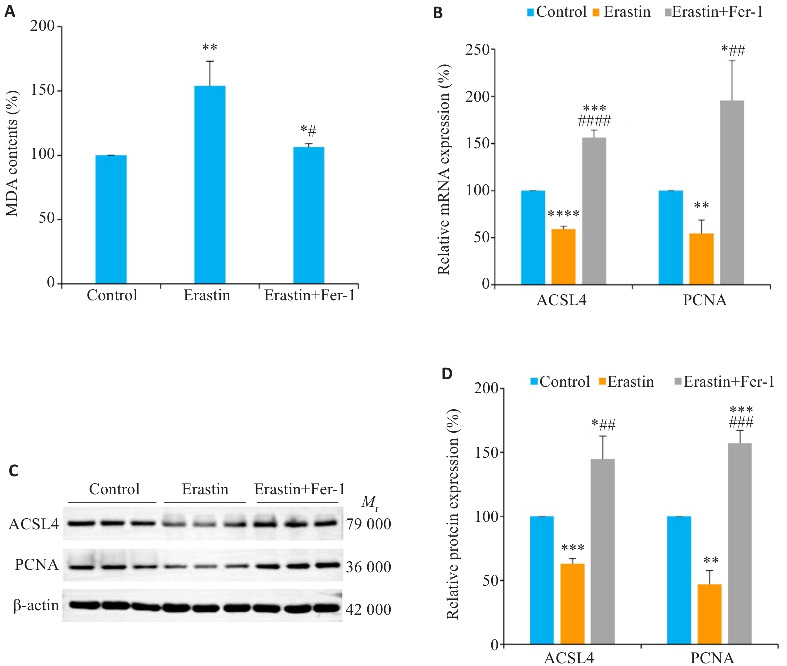

2.4. 铁死亡调控ACSL4对Huh-7细胞MDA含量及PCNA表达的影响

Huh-7细胞中仅加入Erastin,与对照组相比,MDA含量升高的同时(P<0.01,图4A),还可下调ACSL4与增殖标志物PCNA的mRNA和蛋白表达(P<0.01,图4B~D);Erastin预处理后加入Fer-1,发现,Fer-1可逆转Erastin的上述作用(P<0.05,图4A~D)。

图4.

铁死亡调控ACSL4对Huh-7细胞MDA含量及PCNA表达的影响

Fig. 4 Effects of Erastin and Fer-1 on MDA contents and ACSL4 and PCNA expressions in Huh-7 cells. A: Effects of Erastin and Fer-1 on MDA contents in Huh-7 cells. B: Effects of Erastin and Fer-1 on mRNA expressions of ACSL4 and PCNA (RT-qPCR). C: Effects of Erastin and Fer-1 on protein expressions of ACSL4 and PCNA (Western blotting). D: Relative protein expression levels of ACSL4 and PCNA. *P<0.05, **P<0.01, ***P<0.001, ****P<0.0001 vs Control; # P<0.05, ## P<0.01, ### P<0.001, #### P<0.0001 vs Erastin.

2.5. 铁死亡调控ACSL4对Huh-7细胞增殖能力的影响

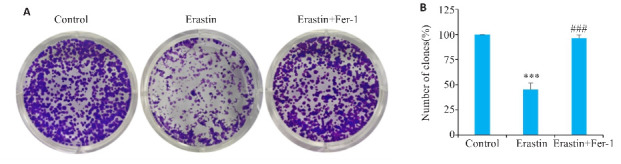

平板克隆实验结果表明,相较于对照组,单独给予Erastin 能够显著抑制Huh-7细胞的集落形成(P<0.001,图5B),采用Erastin加Fer-1联合用药后,与Erastin组相比,Fer-1可以逆转Erastin对Huh-7细胞增殖能力的抑制作用(P<0.001,图5B)。

图5.

铁死亡调控ACSL4对Huh-7细胞增殖能力的影响

Fig.5 Effects of Erastin and Fer-1 on proliferation ability of Huh-7 cells. A: Plate cloning assay of the cells treated with Erastin and Fer-1. B: Number of cell clones. ***P<0.001 vs Control; ### P<0.001 vs Erastin.

3. 讨论

MDA含量作为铁死亡的关键检测指标,反映细胞内Fe2+浓度提示铁死亡的发生。本研究通过收集临床肝癌患者手术切除的组织样本,发现相较于癌旁正常肝组织,癌组织中作为铁死亡检测指标之一的MDA含量显著降低;而且肝癌增殖标志物PCNA mRNA与蛋白高表达的同时 ACSL4的表达也呈显著增强。说明铁死亡关键因子ACSL4伴随肝癌增殖标志物 PCNA的表达同步改变,与文献[23]通过生物信息学分析获得的趋势一致;且生存曲线表明高表达ACSL4的患者预后不良[23]。因此,ACSL4将为肝癌的诊断与防治提供又一潜在新靶标。

铁死亡诱导剂Erastin能有选择性地作用于肿瘤细胞,产生抗肿瘤活性[24],并通过抑制胱氨酸/谷氨酸反向转运体活性,阻止细胞外的胱氨酸进入细胞内部,阻断细胞内谷胱甘肽的合成,使细胞的抗氧化能力被削弱,最终诱导铁死亡[25, 26]。本研究通过肝癌细胞体外实验,明确Erastin可提升细胞中MDA含量,下调 ACSL4与PCNA的表达,诱导铁死亡并抑制肝癌细胞增殖。

Fer-1具有抗氧化活性[27],可以逆转由Erastin介导的脂质活性氧积累[28],从而抑制Erastin诱导的细胞铁死亡[29]。本研究结果显示,Erastin预处理后采用Fer-1处理细胞,Fer-1可逆转单独给予Erastin 对Huh-7细胞的抑制作用,包括细胞增殖能力,细胞中ACSL4、PCNA表达的上调,以及MDA含量的降低,从而抑制癌细胞铁死亡。结合文献[23],干预SMMC-7721和Huh-7两种肝癌细胞中ACSL4的表达,结果发现siRNA敲减ACSL4的表达可显著抑制癌细胞增殖、侵袭和迁移,而过表达则趋势恰好相反。说明ACSL4确能对肝癌细胞增殖发挥关键作用。该研究中还通过荧光素酶报告基因检测等结果进一步展示,ACSL4靶向调控Sp1介导的PAK2转录。铁螯合剂介导的肝脏铁代谢可主要通过下调c-MYC和ACSL4表达,抑制代谢相关脂肪性肝炎进展过程中的肝脏铁死亡[30]。上述研究提示ACSL4及其下游相关信号通路在铁死亡中的重要作用,但其中的具体机制仍有待进一步的研究证实。

因此,ACSL4在肝癌中表达显著增强,Erastin可上调MDA含量、下调ACSL4,诱导肝癌细胞铁死亡,抑制癌细胞增殖;Fer-1则可逆转Erastin的上述作用。

基金资助

国家自然科学基金(82060662);广西区自然科学基金(2022JJA140776,2022JJA140639)

Supported by National Natural Science Foundation of China (82060662).

参考文献

- 1. Bray F, Laversanne M, Sung H, et al. Global cancer statistics 2022: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries [J]. CA Cancer J Clin, 2024, 74(3): 229-63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Yin Y, Feng WB, Chen J, et al. Immunosuppressive tumor microenvironment in the progression, metastasis, and therapy of hepatocellular carcinoma: from bench to bedside [J]. Exp Hematol Oncol, 2024, 13(1): 72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Yi JZ, Li BB, Yin XM, et al. CircMYBL2 facilitates hepatocellular carcinoma progression by regulating E2F1 expression [J]. Oncol Res, 2024, 32(6): 1129-39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Li Y, Lu LQ, Tu J, et al. Reciprocal Regulation Between Forkhead Box M1/NF‑κB and Methionine Adenosyltransferase 1A Drives Liver Cancer [J]. Hepatology, 2020, 72(5): 1682-700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. 刘叶琴, 周志刚, 杨明辉, 等. FOX家族促进肝纤维化的研究进展[J]. 华夏医学, 2023, 36(06): 170-4. [Google Scholar]

- 6. McGlynn KA, Petrick JL, Groopman JD. Liver Cancer: Progress and Priorities [J]. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev, 2024, 33(10): 1261-72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Zhu XY, Sha XD, Zang Y, et al. Current Progress of Ferroptosis Study in Hepatocellular Carcinoma [J]. Int J Biol Sci, 2024, 20(9): 3621-37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Li SW, Zhang GX, Hu JK, et al. Ferroptosis at the nexus of metabolism and metabolic diseases [J]. Theranostics, 2024, 14(15): 5826-52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Jiang YL, Yu YX, Pan ZY, et al. Ferroptosis: a new hunter of hepatocellular carcinoma [J]. Cell Death Discov, 2024, 10(1): 136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Li XD, Meng FG, Wang HK, et al. Iron accumulation and lipid peroxidation: implication of ferroptosis in hepatocellular carcinoma [J]. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne), 2024, 14: 1319969. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Liu RJ, Yu XD, Yan SS, et al. Ferroptosis, pyroptosis and necroptosis in hepatocellular carcinoma immunotherapy: Mechanisms and immunologic landscape (Review) [J]. Int J Oncol, 2024, 64(6): 63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. 葛树杰, 胡永全, 周晓静, 等. GPX4介导铁死亡在上皮性卵巢癌顺铂耐药细胞中的作用 [J]. 华夏医学, 2023, 36(4): 42-6. [Google Scholar]

- 13. Xu QP, Ren LQ, Ren N, et al. Ferroptosis: a new promising target for hepatocellular carcinoma therapy [J]. Mol Cell Biochem, 2023, 11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Zhang W, Jiang BP, Liu YX, et al. Bufotalin induces ferroptosis in non-small cell lung cancer cells by facilitating the ubiquitination and degradation of GPX4 [J]. Free Radic Biol Med, 2022, 180: 75-84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Rochette L, Dogon G, Rigal E, et al. Lipid peroxidation and iron metabolism: Two corner stones in the homeostasis control of ferroptosis [J]. Int J Mol Sci, 2022, 24 (1): 449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Nie JH, Lin BL, Zhou M, et al. Role of ferroptosis in hepatocellular carcinoma [J]. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol, 2018, 144(12): 2329-37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Xu XT, Zhang XY, Wei CQ, et al. Targeting SLC7A11 specifically suppresses the progression of colorectal cancer stem cells via inducing ferroptosis [J]. Eur J Pharm Sci, 2020, 152: 105450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Yan XY, Liu YD, Li CC, et al. Pien-Tze-Huang prevents hepatocellular carcinoma by inducing ferroptosis via inhibiting SLC7A11-GSH-GPX4 axis [J]. Cancer Cell Int, 2023, 23 (1): 10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Toshida K, Itoh S, Iseda N, et al. Impact of ACSL4 on the prognosis of hepatocellular carcinoma: Association with cancer-associated fibroblasts and the tumour immune microenvironment [J]. Liver Int, 2024, 44(4): 1011-23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Zhang L, Luo YL, Xiang Y, et al. Ferroptosis inhibitors: past, present and future [J]. Front Pharmacol, 2024, 15: 1407335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Ding KY, Liu CB, Li L, et al. Acyl-CoA synthase ACSL4: an essential target in ferroptosis and fatty acid metabolism [J]. Chin Med J (Engl), 2023, 136(21): 2521-37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Viswanathan VS, Ryan MJ, Dhruv HD, et al. Dependency of a therapy-resistant state of cancer cells on a lipid peroxidase pathway [J]. Nature, 2017, 547(7664): 453-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Wu DD, Zuo ZZ, Sun XN, et al. ACSL4 promotes malignant progression of Hepatocellular carcinoma by targeting PAK2 transcription [J]. Biochem Pharmacol, 2024, 224: 116206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Sun YW, Deng RR, Zhang CW. Erastin induces apoptotic and ferroptotic cell death by inducing ROS accumulation by causing mitochondrial dysfunction in gastric cancer cell HGC‑27 [J]. Mol Med Rep, 2020, 22(4): 2826-32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Hang TD, Hung HM, Beckers P, et al. Structural investigation of human cystine/glutamate antiporter system xc‑(Sxc‑) using homology modeling and molecular dynamics [J]. Front Mol Biosci, 2022, 9: 1064199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Cao JY, Dixon SJ. Mechanisms of ferroptosis [J]. Cell Mol Life Sci, 2016, 73: 2195-209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Maeda H, Miura K, Aizawa K, et al. Apomorphine Suppresses the Progression of Steatohepatitis by Inhibiting Ferroptosis [J]. Antioxidants (Basel), 2024, 13(7): 805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Dixon SJ, Lemberg KM, Lamprecht MR, et al. Ferroptosis: an iron-dependent form of nonapoptotic cell death [J]. Cell, 2012, 149 (5): 1060-72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Chu J, Liu CX, Song R, et al. Ferrostatin-1 protects HT-22 cells from oxidative toxicity [J]. Neural Regen Res, 2020, 15(3): 528-36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Tao L, Yang XY, Ge CD, et al. Integrative clinical and preclinical studies identify FerroTerminator1 as a potent therapeutic drug for MASH [J]. Cell Metab, 2024, S1550-4131(24): 00284-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]