Abstract

Cardiovascular diseases, characterized by high morbidity, disability, and mortality rates, are a collective term for disorders affecting the heart’s structure or function. In clinical practice, physicians often manually delineate the left ventricular border on echocardiograms to obtain critical physiological parameters such as left ventricular volume and ejection fraction, which are essential for accurate cardiac function assessment. However, most state-of-the-art models focus excessively on pushing the boundaries of segmentation accuracy at the expense of computational complexity, overlooking the substantial demand for high-performance computing resources required for model inference in clinical applications. This paper introduces a novel left ventricle echocardiographic segmentation model that efficiently combines the SwiftFormer Encoder and U-Lite Decoder to reduce network parameter count and computational complexity. Additionally, we incorporate the Spatial and Channel reconstruction Convolution (SCConv) module through spatial and channel reconstruction during downsampling and replace the Binary Cross Entropy Loss (BCELoss) with Polynomial Loss (PolyLoss) to achieve superior segmentation performance. On the EchoNet-Dynamic dataset, our network achieves a Dice similarity coefficient of 0.92714 for left ventricle segmentation, with FLoating-point Operations Per Second (FLOPs) and Parameters of just 4472.55 M and 28.96 M respectively. Extensive experimental results on the EchoNet-Dynamic dataset demonstrate that the proposed modifications deliver competitive performance at a lower computational cost.

Keywords: Left ventricular segmentation, SwiftFormer, U-Lite, SCConv, PolyLoss

Subject terms: Cardiology, Image processing, Machine learning

Introduction

Echocardiography is a non-invasive imaging technique that utilizes ultrasound to visualize cardiac structures and functions. This technology provides real-time images of the heart, assisting physicians in evaluating its structure, systolic and diastolic function, output, and capacity. Among the parameters obtained, left ventricular end-diastolic volume (LVEDV) and left ventricular end-systolic volume (LVESV) are crucial for assessing cardiac pumping function and diagnosing cardiovascular diseases; these measurements help clinicians understand the heart’s contractile and relaxation capabilities, as well as its overall functional status. However, due to the requirement for specialized training and experience in operating and interpreting echocardiograms, measurements can vary between different operators, introducing subjectivity and variability. Furthermore, image quality in echocardiography is influenced by factors such as patient body habitus, lung overlay, and chest wall thickness, which may compromise image clarity and, consequently, the accuracy of left ventricular volume measurements. Therefore, capturing accurate left ventricular volumes during echocardiographic examinations presents a significant challenge.

Since the mid-2010s, deep learning has emerged as the predominant tool in machine learning, finding broad application across various research domains, particularly in image analysis and computer vision. This era has been marked by significant breakthroughs in deep learning technologies, exemplified by Schmidhuber’s comprehensive review of deep learning in neural networks1. Notably, in 2012, AlexNet achieved remarkable success in the ImageNet competition, propelling the application and development of deep learning in the field of image recognition2. Subsequently, deep learning-based segmentation of ultrasonic images demonstrated tremendous potential, capable of directly processing ultrasonic images, automatically learning abstract features from raw ultrasonic data, and segmenting parts of the image with special significance. This capability provides reliable diagnostic references for clinicians during diagnosis and treatment, aiding medical professionals in making more accurate and objective diagnoses. As deep learning technology continues to advance in the medical field, ultrasonic image segmentation has become an essential technique for ultrasonic image analysis3–5.

Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) are the most widely applied deep learning method in the field of image segmentation. In traditional CNN architectures, convolution kernels are used to extract feature information from images, followed by pooling layers that reduce the size of feature maps and increase their dimensionality, culminating in fully connected layers for image classification tasks6. This approach requires fixed input image sizes and can only capture local information, leading to redundant pixel computations across image patches, resulting in large computational loads and suboptimal precision. In many visual tasks, there is a desire for neural networks to classify each individual pixel of an image, i.e., directly outputting segmentation results through a segmentation network, simplifying the image segmentation process. Networks capable of such functionality are referred to as end-to-end networks. End-to-end segmentation networks can be categorized into two types: those based on dilated convolution frameworks, exemplified by DeepLab7, and those based on encoder-decoder frameworks, represented by UNet8.

Compared to traditional CNNs, end-to-end networks, when applied to image segmentation, match the receptive field to the size of the segmentation target, often achieving higher recognition accuracy and superior performance on numerous tasks. Xu, Mengqi et al.9; Li, Xiaodi and Yue Hu10; Chen, Wei, et al.11 have introduced extensive research utilizing end-to-end segmentation methods, where segmentation outcomes have reached satisfactory levels in natural images. However, the precision requirements for segmentation in medical images far exceed those of natural images. While precise segmentation masks might not be critical in natural images, even minor edge segmentation errors in medical images can impact user experience in clinical settings. To address this, Isensee et al.12 introduced nnU-Net, a self-adaptive framework capable of automatically adjusting hyperparameters and optimizing training strategies, significantly enhancing U-Net’s performance across various medical image segmentation tasks. Peng, Yaopeng et al.13 enhanced the skip connections within the U-Net architecture, intensifying the injection of semantic information into low-level features while refining the details of high-level features, and improving segmentation accuracy on skin lesion and polyp datasets. Qi, Yaolei, et al.14 proposed a network (DSCNet) based on dynamic snake convolution and topological geometric constraints, which, by adaptively focusing on local features of tubular structures and fusing multi-view features, significantly improved the segmentation accuracy and topological continuity of tubular structures in medical images. Despite these advancements, the performance of these methods varies considerably, indicating that differences in imaging principles and tissue characteristics directly influence the design of medical segmentation algorithms, the selection of image preprocessing steps, and segmentation accuracy.

Left ventricular segmentation in echocardiography, as a subfield of medical image segmentation, confronts distinct challenges. From an imaging perspective, the variability in echocardiographic image quality, morphological changes induced by the cardiac cycle, and blurred boundaries caused by cardiac motion necessitate highly robust algorithms capable of adapting to diverse image qualities and complex physiological variations15–17. Regarding data, clinicians typically provide annotations for only two frames per video – end-diastole (ED) and end-systole (ES) frames – which makes echocardiographic image segmentation more challenging than other medical image segmentation tasks18,19. Targeting the unique characteristics of echocardiographic images, Ouyang, David, et al.20 employed a 3D convolutional neural network to capture spatiotemporal patterns for left ventricular semantic segmentation, enhancing the consistency and real-time capability of cardiac function evaluation, albeit at a higher computational cost compared to 2D convolutional neural networks. Thomas, S., et al.21 introduced EchoGraphs, leveraging graph convolutional networks to detect anatomical keypoints for predicting ejection fractions and segmenting the left ventricle, balancing local appearance and global shape, but also imposing limitations due to strong dependence on annotated data. Painchaud et al.22 enforced temporal smoothness in the post-processing step of video segmentation outputs to improve average segmentation performance, yet it still relies on prior segmentation methods that might require high-quality annotated data for training. Addressing the issue of limited supervised labels for echocardiogram data, recent studies have adopted self-supervised learning techniques to effectively utilize unannotated echocardiogram frames. Saeed et al.23employed contrastive pre-training for self-supervised echocardiogram learning, which can enhance left ventricular segmentation performance under limited annotation data for downstream tasks, but their solution retained the shortcomings of basic end-to-end segmentation models with high computational and parameter costs. Currently, there remains significant room for improvement in left ventricular echocardiographic image segmentation methodologies, particularly in terms of streamlining networks to maintain segmentation performance while applying algorithms in clinical diagnostics with resource-constrained environments24.

In this work, we introduce a lightweight segmentation network pretrained with contrastive learning, thereby reducing the demand for data and computational resources in high-performance left ventricular echocardiographic image segmentation algorithms. The network enhances representative feature learning by incorporating SCConv convolution units and adopts a loss function framework named PolyLoss during loss computation to regulate the shape and gradient of the loss function. Moreover, we investigated the performance of various lightweight encoder-decoder combinations in the task of left ventricular echocardiographic image segmentation. We found that the model combining a SwiftFormer encoder with a ULite decoder, along with SCConv units and the PolyLoss loss function, outperformed all other models on the EchoNet-Dynamic dataset, boasting advantages in terms of both parameter count and computational load compared to most models.

In summary, our contributions in this paper can be outlined as follows:

We introduced PolyLoss into our model, a novel loss function that adjusts the importance of different polynomial bases by viewing the loss function as a linear combination of polynomial functions, achieving a significant improvement over the commonly used cross-entropy loss in the left ventricular segmentation task.

During the design of the downsampling module, we adopted a Depthwise convolution operation called SCConv, which sequentially combines SRU (Spatial Reconstruction Unit) and CRU (Channel Reconstruction Unit) to extract features after standard convolution operations in CNNs. It has been proven that SCConv significantly enhances the quality of feature extraction, thereby boosting the model’s performance in left ventricular segmentation tasks.

We conducted comparisons among 10 different model design choices on the EchoNet-Dynamic dataset, pairing 7 encoders with 4 decoders in a staged manner. Ultimately, the combination of a SwiftFormer encoder with a ULite decoder, integrated with SCConv units and the PolyLoss loss function, was determined to be the optimal model architecture.

Methods

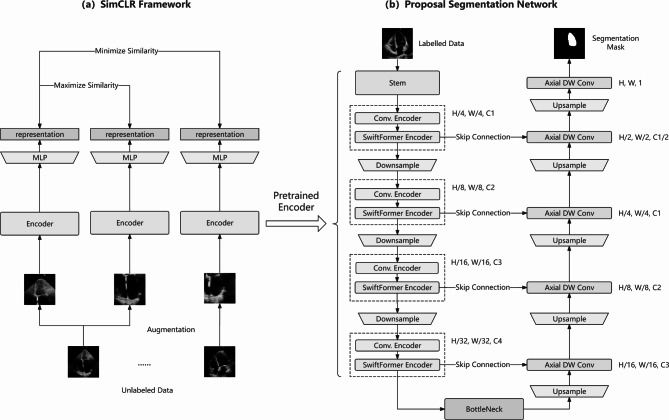

In this paper, we utilized the largest publicly available human cardiac apical four-chamber (A4C) view echocardiography dataset, EchoNet-Dynamic. An overview of the overall model is illustrated in Fig. 1. Initially, we trained the encoder using SimCLR on unlabelled data, then loaded the pretrained weights into the model’s Encoder to train on labelled data for the left ventricular segmentation task.

Fig. 1.

Architecture Overview.

During the pretraining phase, as depicted in Fig. 1(a), we attempted to apply contrastive learning via SimCLR on unlabelled images from the EchoNet-Dynamic dataset. Firstly, for each input sample, a series of data augmentation techniques were applied to create two randomly transformed copies, including random cropping, color distortion, graying, among others, aiming to increase data diversity. Subsequently, the augmented images from the same sample within the same batch were passed through the same encoder network and projection head to derive feature representations. During training, the contrastive loss function encouraged representations from the same sample to be close in the feature space while repelling those from different samples. After training, the parameters of the Encoder contained meaningful feature representations learned from the data, which could enhance the model’s generalization ability in downstream tasks.

In the downstream segmentation stage, as shown in Fig. 1(b), we removed the projection head from the contrastive learning network, appended a decoder that maps features back to the original image size behind the encoder, and fine-tuned the model for the segmentation task by loading the weights obtained from pretraining. In this paper, we employed a symmetric encoder-decoder architecture model, primarily consisting of four components: a downsampling module combining SCConv for feature map spatial and channel reconstruction, a SwiftFormer encoder that replaced matrix multiplication of self-attention with element-wise multiplication, a ULite decoder with axial separable convolutions, and PolyLoss that adjusts the contribution of different polynomial terms to the gradients to optimize model performance.

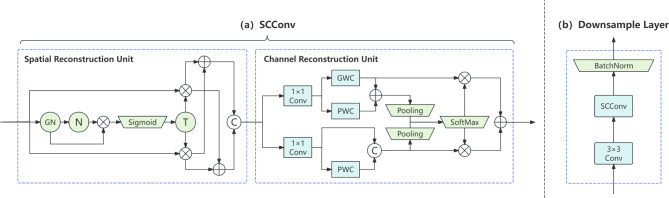

Scconv module

SCConv is a novel convolution layer design aimed at reducing feature redundancy and enhancing the efficiency of convolutional neural networks25. The core idea of SCConv involves introducing spatial and channel reconstruction mechanisms into conventional convolutional layers to minimize redundant information in feature representations, enabling the model to learn features more effectively.

Specifically, as illustrated in Fig. 2(a), SCConv comprises two modules: the Spatial Reconstruction Unit (SRU) and the Channel Reconstruction Unit (CRU). The SRU reduces redundancy in the spatial dimensions through a separate-reconstruct operation. It employs scaling factors from Group Normalization to evaluate the information content of different feature maps, subsequently dividing them into high-information and low-information subsets using learnable weights for cross-reconstruction, thus enriching the representation. Within the SRU, the scaling factors from the Group Normalization (GN) layer26 assess the information content of distinct feature maps, where N denotes normalization along the batch axis, C signifies concatenation along the channel axis, and T stands for threshold. The separation operation, as shown in Eq. (1), involves passing the input feature map X through GN and N, then reweighting it. The resulting weights are mapped to the range (0, 1) using the sigmoid function. These weights are then thresholded to split them into informative weights W1 and non-informative weights W2. The reconstruction operation, as shown in Eq. (2), involves multiplying the input feature map X by W1 and W2 to obtain their weighted features. These weighted features are then split into two parts along the channel dimension and cross-added to produce Xw1 and Xw2. Finally, they are concatenated along the channel dimension to obtain the spatially refined feature map Xw. The CRU adopts a divide-transform-combine strategy to diminish redundancy in the channel dimensions. It partitions the channels of the feature map into two segments, one undergoing efficient convolution operations to extract rich features, while the other undergoes shallow convolution operations to supplement detail information. These two segments are then merged adaptively through a soft attention mechanism. Within the CRU, group-wise convolution (GWC)27 is utilized to connect each output channel to only a subset of input channels as a substitute for expensive full convolution operations, point-wise convolution (PWC) maintains information flow between channels, and dimensionality reduction is achieved by decreasing the number of filters.

|

1 |

|

2 |

Fig. 2.

SCConv Module Architecture.

When designing the downsampling layer, we incorporated the sequential combination of the SRU and CRU modules following the downsampling convolution, as shown in Fig. 2(b), to reduce spatial and channel redundancies in the feature maps while enhancing discriminative features, thereby augmenting the model’s representational capacity. The application of the SCConv module not only boosts the accuracy and reliability of left ventricular segmentation but also elevates model efficiency with minimal additional computational resources and storage space.

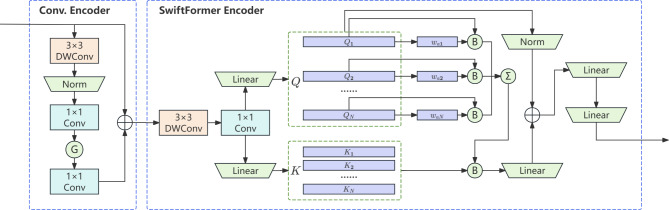

Swiftformer block

SwiftFormer is a novel, lightweight, and efficient visual model optimized for mobile real-time applications. It introduces the SwiftFormer module, designed based on the Transformer architecture, which significantly enhances model performance while maintaining efficient inference28.

The SwiftFormer module is geared towards learning rich local-global representations. As depicted in Fig. 3, it takes the feature maps output by the convolutional encoder as input. First, a local convolution layer is employed to extract local features, followed by feeding the feature maps into the Efficient Additive Attention module to learn global contextual information. Here, G represents the activation function GeLU; B represents broadcasted element-wise multiplication, used to multiply the query matrix by a learnable weight-pooling to generate global queries. The Efficient Additive Attention module replaces the matrix multiplication operation in the standard self-attention mechanism with linear element-wise multiplication, substantially reducing computational complexity. By omitting key-value interactions and retaining only query-key interactions, the model achieves linear computational complexity relative to token quantity, striking a good balance between speed and accuracy.

Fig. 3.

Swiftformer Module Architecture.

By combining the convolutional encoder with the SwiftFormer module, SwiftFormer’s encoder adopts a consistent hybrid design, enabling the extraction of hierarchical image features and learning of global contexts. This design allows the model to achieve outstanding performance while possessing the capability for rapid inference, making it suitable for real-time left ventricular segmentation tasks on edge devices.

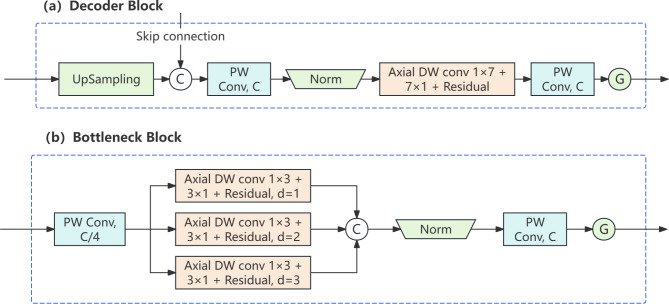

U-Lite

U-Lite is a lightweight, CNN-based medical image segmentation model that significantly reduces the number of model parameters compared to conventional U-Nets by employing Axial Dilated Depthwise Convolution modules to expand the model’s receptive field, while achieving commendable performance in medical image segmentation tasks29.

The decoder part of U-Lite adopts the design principle of Axial Dilated Depthwise Convolution, extracting features at different levels through a combination of convolutional layers, activation function layers, and normalization layers while restricting the use of unnecessary operators. As shown in Fig. 4(a), C represents connection; G represents the activation function GeLU. Each decoder block incorporates a batch normalization layer and concludes with a GELU activation function. The bottleneck section of U-Lite similarly employs Axial Dilated Depthwise Convolution but uses different dilation rates to capture multi-scale feature representations. As depicted in Fig. 4(b), the kernel size of the Axial Dilated Depthwise Convolution is n = 3, with dilation rates of d = 1, 2, 3 applied. When using dilated convolutions with varying rates to capture multi-spatial representations of underlying high-level features, it offers superior performance.

Fig. 4.

U-Lite Decoder and Bottleneck Architecture.

Overall, U-Lite adopts a classic encoder-decoder structure, implementing the Axial Dilated Depthwise Convolution design in both the decoder and bottleneck sections. The entire model structure is simple and efficient, achieving good segmentation results while maintaining a small parameter count and computational load.

Polyloss

PolyLoss is a novel loss function framework designed for classification tasks30, whose central concept involves utilizing Taylor expansion to represent both cross-entropy loss and focal loss as a linear combination of polynomial functions, with each polynomial function (1-Pt)j weighted by its corresponding coefficient αj, thus providing a unified approach to understand and design loss functions.

The PolyLoss framework allows for the adjustment of the importance of each polynomial coefficient αj based on different tasks and datasets, naturally encompassing cross-entropy loss and focal loss as special cases. As shown in Eq. (3), the Poly-1 loss function proposed under the PolyLoss framework was utilized in the experiments of this paper, adjusting only the coefficient of the first polynomial in the cross-entropy loss function. This modification was achieved by introducing a hyperparameter ε1, enabling a simple yet effective alteration of the shape of the loss function.

|

3 |

Experiments and results

Implementation detail

Dataset

The EchoNet-Dynamic dataset20is a large-scale cardiac motion video resource for medical machine learning. This dataset encompasses 10,030 echocardiography videos, along with annotations by human experts (including measurements, tracking, and calculations), designed to serve as a benchmark for studying cardiac motion and chamber size24. The videos cover a range of typical echocardiography laboratory imaging conditions and are matched with the results computed and measured in clinical reports. Every video in the dataset is associated with clinical measurements and calculations, and the left ventricular contours, ejection fraction (EF), end-systolic (ES) frames, and end-diastolic (ED) frames are labeled by echocardiographers certified at level 3 in the standard clinical workflow.

To ensure a fair comparison and patient-wise split, our data partitioning method mirrors the setup described in the original EchoNet-Dynamic paper. Unlabeled frames between ES and ED encompass the complete systole-diastole process; for each patient, we sampled a random frame between ES and ED for pre-training, yielding 116,917 images for training, 20,619 images for validation, and 20,360 images for testing. The two annotated ES and ED frames from each video were designated for the downstream segmentation task, producing 14,839 images for training, 2,561 images for validation, and 2,540 images for testing. The envelope within the curve formed by sequentially connecting key points at the endocardial border served as the ground truth for the left ventricular segmentation task.

Training strategy

We implemented our model on a 24GB NVIDIA RTX A5000 GPU using the Pytorch-Lightning framework. For both pretraining and downstream tasks, all images were resized to 224*224 pixels, with bilinear interpolation applied to input images and nearest neighbor interpolation to masks.

To enhance the model’s ability to extract image features, we leveraged unlabelled data from the EchoNet-Dynamic dataset, employing self-supervised learning to enable the model to learn as accurate feature representations as possible with a limited number of samples. To prevent overfitting during the 300-epoch training phase of pretraining, we augmented the data through various techniques such as random rotation, horizontal flipping, and vertical flipping at the data loading stage. We trained using the Sophia optimization algorithm31with an initial learning rate of 1e-3, setting the batch size to 64, and utilizing the nt_xent_loss function32. The nt_xent_loss is a variant of the InfoNCE loss function, designed to measure the similarity between two input samples in the embedding space, enabling the model to better learn how to distinguish samples of different classes. The mathematical representation of nt_xent_loss is shown in Eq. (4).

|

4 |

In the nt_xent_loss formula, zi and zj represent the embedded representations of a pair of positive samples; Sim( zi zj ) denotes the cosine similarity between the two vectors; τ is the temperature parameter; [1[k≠i]] is an indicator function that excludes the case of comparing with itself in the denominator; 2N indicates that two views of each sample are generated through data augmentation.

In the downstream segmentation task, the batch size was set to 32, with an initial learning rate of 1e-4. Training was carried out using the Madgrad optimizer, and the performance of BCELoss and PolyLoss in the segmentation task was compared. Grid search was employed to optimize the training iterations, initial learning rate, and weight decay factor for each model.

Evaluation metric

To evaluate model performance, we employed the most popular metrics in semantic segmentation tasks, namely the Dice Similarity Coefficient (DSC), floating-point operations per second (FLOPs), and Parameters (Params). In fields such as medical image segmentation, DSC is a critical metric for assessing model accuracy because it reflects the model’s capability to distinguish between different structures. DSC is typically used to gauge the overlap between predicted labels and ground truth labels, with values ranging from 0 to 1, where 1 indicates perfect overlap and 0 indicates no overlap. The calculation formula for the DSC is shown in Eq. (5).

|

5 |

Where |X| and |Y| are the number of elements in the predicted label and ground truth label, respectively, and |X∩Y| represents the number of common elements between the predicted and ground truth labels. FLOPs refer to the number of floating-point operations performed per second when the model executes computations, serving as a measure of computational complexity. FLOPs are a crucial metric for evaluating model efficiency, particularly when considering computational resources and energy consumption in practical applications. Lower FLOPs values generally indicate a more efficient model that is easier to run on resource-constrained devices. Params denote the total number of all trainable parameters in the model, essentially the size of the model. Params impact the model’s capacity and complexity. More parameters usually signify greater representational power but can also lead to overfitting and higher computational costs. Consequently, Params are a significant consideration in model selection and design.

Results and analysis

To substantiate the superior performance of our proposed model, we compared it against other models on the left ventricular segmentation task using the EchoNet-Dynamic test set, evaluating each model based on DSC, FLOPs, and Params, and contrasting the outcomes of echocardiographic left ventricular instance segmentation using various lightweight decoders.

We optimized the model performance based on SwiftFormer. By using SimCLR pre-training, we achieved a DCS of 0.92187 in our cardiac ultrasound image segmentation model based on SwiftFormer, which represents a 0.3% improvement over the SwiftFormer segmentation model without SimCLR pre-training, where the DCS was 0.91826. This demonstrates that SimCLR pre-training can better assist cardiac ultrasound image segmentation models in achieving performance improvements.

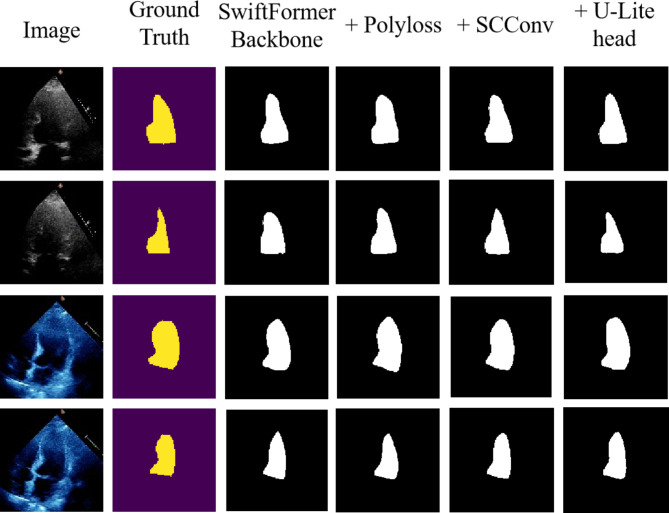

Building upon the foundation of SimCLR pre-training, we explored the impact of introducing various model improvements on model performance, thereby providing a better understanding of how the model operates. Table 1 illustrates the performance shifts in our model upon incorporating various new components, benefiting from SimCLR pre-training or improvements across different network sections on top of the SwiftFormer Backbone, including the Polyloss loss function, SCConv module, and U-Lite decoder. We observed that the introduction of each new component increases the DCS compared to the SwiftFormer backbone network, as visually demonstrated in Fig. 5. When multiple new components were combined during training, the model’s performance improved even further than when introducing single enhancements, indicating that each improvement was necessary and effective for model performance. When all new components were integrated into the model training, the segmentation performance could be further enhanced relative to the SwiftFormer Backbone, despite reduced computational load and parameter count.

Table 1.

Ablation experiment.

| Method | DCS (95% CI) |

p-value | FLOPs (M) |

Params (M) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SwiftFormer Backbone |

Polyloss | SCConv | U-Lite head |

||||

| √ |

0.92187 (0.9216, 0.9221) |

- | 5528.60 | 32.54 | |||

| √ | √ |

0.92493 (0.9246, 0.9252) |

< 0.001 | 5528.60 | 32.54 | ||

| √ | √ | √ |

0.92552 (0.9251, 0.9258) |

< 0.001 | 5659.69 | 33.24 | |

| √ | √ | √ |

0.92249 (0.9220, 0.9229) |

0.009 | 4341.46 | 28.26 | |

| √ | √ | √ |

0.92583 (0.9252, 0.9263) |

0.003 | 5659.69 | 33.23 | |

| √ | √ | √ |

0.92511 (0.9249, 0.9252) |

0.129 | 4341.46 | 28.26 | |

| √ | √ | √ | √ |

0.92714 (0.9265, 0.9277) |

0.002 | 4472.55 | 28.96 |

Fig. 5.

Comparison of segmentation performance for ablation experiment.

To demonstrate that the addition of different components has statistically significant improvements on model performance, we combined the results from multiple experiments and performed an independent samples t-test on the two samples before and after component addition. The p-values are listed in Table 1 to show whether the results are significant. Additionally, to help us better understand and interpret the data, we calculated the 95% confidence interval (95% CI) for the DCS of each model using the t-distribution. We observed that, except for the improvement when adding the U-Lite head on top of Polyloss, the p-values for the DCS of all other component additions were less than 0.05, indicating statistically significant differences. The p-value for the DCS of the model with the improvement of adding the U-Lite head on top of Polyloss was 0.129, which is not statistically significant, but it still effectively reduced the model’s FLOPs and Params, making it a meaningful improvement.

With the decoder fixed as Unet-Decoder, we compared various encoder combinations. To ensure fair results in the comparative experiments, all models in this experiment underwent SimCLR pre-training. In Table 2, the SwiftFormer encoder improved with SCConv and PolyLoss is referred to as SwiftFormer(SCConv). Experimental results indicate that when employing our proposed SwiftFormer(SCConv), the model achieves a DCS of 92.58%, 5659.69 M FLOPs, and 33.23 M Params. Compared to U-Net, the most commonly used model in medical image segmentation, SwiftFormer(SCConv) improves DCS performance by 0.73%; relative to DeepLab-V3, the model with the closest DCS, SwiftFormer(SCConv) enhances DCS by 0.06%; and in contrast to ShuffleNet-V233and MobileNet-V334, designed specifically for mobile devices, SwiftFormer(SCConv) boosts DCS by 0.297% and 0.956%, respectively. SwiftFormer(SCConv) excels in both maintaining optimal segmentation performance and achieving commendable lightness; its FLOPs are roughly one-sixth of those of DeepLab-V3, while its number of parameters is comparable to some recently proposed lightweight models, such as SwiftFormer28with 32.54 M parameters and EdgeNeXt35 with 22.81 M parameters.

Table 2.

Encoder Comparison under the U-shape Segmentation Network.

| Encoder | Decoder | DCS (95% CI) |

p-value | FLOPs (M) |

Params (M) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DeepLab-V3[7] | Unet-Decoder |

0.9252 (0.9245, 0.9258) |

0.081 | 31413.71 | 39.63 |

| Unet[8] |

0.9185 (0.9161, 0.9208) |

< 0.001 | 30767.52 | 17.27 | |

| ShuffleNet-V2[33] |

0.92286 (0.9222, 0.9234) |

< 0.001 | 2893.19 | 16.28 | |

| MobileNet-V3[34] |

0.91627 (0.9158, 0.9166) |

< 0.001 | 558.82 | 3.41 | |

| EdgeNeXt[35] |

0.9178 (0.9162, 0.9193) |

< 0.001 | 6381.26 | 22.81 | |

| SwiftFormer[28] |

0.92187 (0.9214, 0.9222) |

< 0.001 | 5528.60 | 32.54 | |

| SwiftFormer(SCConv) |

0.92583 (0.9252, 0.9263) |

- | 5659.69 | 33.23 |

We performed independent samples t-tests on the DCS results of various models listed in Table 2 relative to SwiftFormer(SCConv), and listed the p-values in the table to demonstrate whether the differences in DCS results due to different encoders are significant. The table also includes the 95% confidence intervals (95% CI) for the DCS of each model calculated using the t-distribution. We observed that the p-value for the DCS of DeepLab-V3 relative to SwiftFormer(SCConv) is 0.081, which is not statistically significant. However, SwiftFormer(SCConv) has a one-sixth advantage in FLOPs over DeepLab-V3, once again highlighting SwiftFormer(SCConv)’s ability to maintain optimal segmentation performance while remaining lightweight.

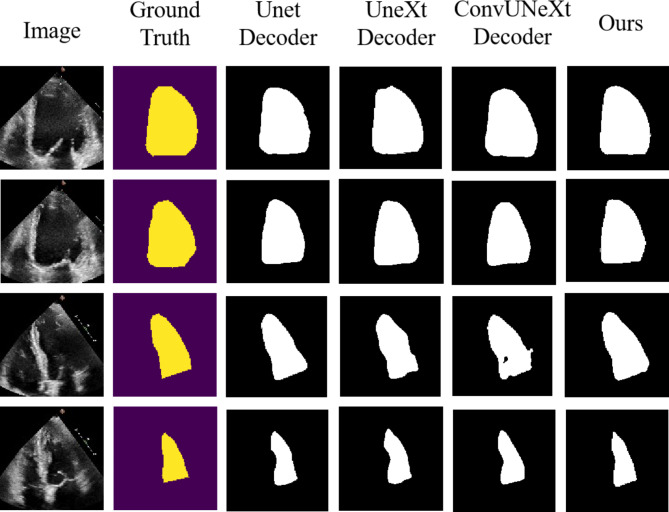

In the encoder comparison experiments, we determined that the SwiftFormer(SCConv), enhanced through SCConv and PolyLoss, was the optimal encoder. To achieve the best model combination, we compared experimental results with different lightweight decoders on top of SwiftFormer(SCConv), as detailed in Table 3. The results revealed that the U-Lite decoder, featuring Axial Dilated Depthwise Convolution, delivered the best performance. We refer to the combined network of SwiftFormer(SCConv) encoder and the U-Lite decoder as ULVSeg (U-Shape Network for Left Ventricular Segmentation). Compared to models using the conventional UNet decoder, ULVSeg increased DCS by 0.131% while reducing Params by 4.27 M; compared to the UneXt36decoder incorporating Tokenized MLP modules, ULVSeg achieved the highest DCS improvement of 0.206%, albeit with inferior Params; compared to the ConvUNeXt37 decoder model, which employs gating mechanisms and linear layer computations for attention weights, ULVSeg increased DCS by 0.084% while decreasing Params by 2.53 M. Overall, ULVSeg maintains high DCS performance while achieving a commendable level of parameter lightness.

Table 3.

Head Comparison under the U-shape Segmentation Network.

| Encoder | Decoder | DCS (95% CI) |

p-value | FLOPs (M) |

Params (M) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SwiftFormer (SCConv) | Unet-Decoder[8] |

0.92583 (0.9250, 0.9265) |

0.004 | 5659.69 | 33.23 |

| UneXt-Decoder[36] |

0.92508 (0.9243, 0.9257) |

< 0.001 | 1912.09 | 3.26 | |

| ConvUNeXt-Decoder[37] |

0.9263 (0.9255, 0.9270) |

0.033 | 5224.35 | 31.49 | |

| U-Lite-Decoder[29] |

0.92714 (0.9265, 0.9277) |

- | 4472.55 | 28.96 |

We performed independent samples t-tests on the DCS results of the models listed in Table 3 relative to U-Lite-Decoder, and listed the p-values in the table to demonstrate whether the differences in DCS results due to different decoders are significant. We also displayed the 95% confidence intervals (95% CI) for the DCS of each model calculated using the t-distribution. We observed that the p-values for the DCS of U-Lite-Decoder relative to all other models are less than 0.05, indicating statistically significant differences. Therefore, it can be concluded that U-Lite-Decoder effectively improves the DCS of the models.

Figure 6 displays qualitative segmentations of representative images from the test set of the EchoNet-Dynamic dataset. To further illustrate the performance of the proposed model, we also showcase the segmentation outcomes of individual decoder models. From the segmentation masks in each figure, it becomes evident that the predictions rendered by our proposed model are closer to the ground truth compared to models utilizing the remaining decoders.

Fig. 6.

Comparison of segmentation performance for different decoding modules.

On the test set of EchoNet-Dynamic, ULVSeg outperforms recently proposed methods for left ventricular segmentation, as detailed in Table 4. Specifically, ULVSeg achieves an impressive DCS score of 0.92714, surpassing not only traditional strong models such as DeepLabv3+38, TDNet39, and EMANet40, but also advanced models designed specifically for medical imaging, including EchoNet, TransUNet41, and DCUNet42. This accomplishment highlights the significant improvement in image segmentation accuracy offered by ULVSeg. In terms of computational efficiency, ULVSeg boasts a FLOPs count of just 4472.55 M, demonstrating high efficiency when compared to Contrastive-Echo’s 31413.71 M. This low computational demand makes ULVSeg particularly suitable for rapid deployment and application in resource-constrained environments, offering robust technical support for real-world clinical scenarios. Additionally, with only 28.96 M parameters, ULVSeg maintains compactness while ensuring high accuracy, significantly lower than competing models like DeepLabv3 + with 61.39 M parameters and TransUNet with 93.19 M. This lightweight design strategy reduces memory footprint, accelerates training and inference processes, and enhances the model’s deployability and scalability.

Table 4.

Performance comparison with state-of-the-art left ventricular segmentation models.

| Model | DCS (95% CI) |

p-value | FLOPs(M) | Params(M) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| DeepLabv3+[38] |

0.9154 (0.9123, 0.9184) |

< 0.001 | 8502 | 61.39 |

| TDNet[39] |

0.9162 (0.9131, 0.9192) |

< 0.001 | 9042 | 59.36 |

| EMANet[40] |

0.9168 (0.9145, 0.9190) |

< 0.001 | 22,057 | 53.77 |

| EchoNet[20] |

0.9170 (0.9166, 0.9173) |

< 0.001 | 15,681 | 39.63 |

| TransUNet[41] |

0.9205 (0.9191, 0.9218) |

< 0.001 | 12,344 | 93.19 |

| DCUNet[42] |

0.9207 (0.9185, 0.9228) |

< 0.001 | 10,990 | 10.26 |

| EchoGraphs[21] |

0.9210 (0.9185, 0.9234) |

< 0.001 | - | 27.1 |

| Contrastive-Echo[23] |

0.9252 (0.9245, 0.9258) |

< 0.001 | 31413.71 | 39.63 |

| UDeep[43] (112*112) |

0.9290 (0.9276, 0.9303) |

0.007 | 8568 | 55.83 |

| ULVSeg (Ours) |

0.92714 (0.9265, 0.9277) |

- | 4472.55 | 28.96 |

We performed independent samples t-tests on the DCS results of the models listed in Table 4 relative to our ULVSeg, and also displayed the 95% confidence intervals (95% CI) for the DCS of each model calculated using the t-distribution. The results in Table 4 show that the p-values for the DCS of all other models relative to ULVSeg are less than 0.05, indicating statistically significant differences. This demonstrates that ULVSeg offers meaningful performance improvements over other models.

In two related studies, namely UDeep43and SimLVSeg-3D44, the input size specifications for segmentation networks were set at 3*112*112, considerably smaller than the commonly used 3*224*224 for current models. Given this discrepancy in dimensions, direct comparisons of FLOPs and Params between these studies and our study are not feasible. It is noteworthy, however, that despite UDeep opting for a lightweight backbone network and its image inputs being one-fourth the size in all dimensions compared to those used in our study, the model’s FLOPs and Params are nearly double those of ULVSeg, reaching 8568 M and 55.83 M, respectively. This phenomenon underscores ULVSeg’s ability to achieve more economical computational and storage requirements, reflecting our notable success in balancing model efficiency and performance.

Discussion

Automated left ventricular (LV) segmentation is crucial for timely, reproducible, and accurate delineation of cardiac volumes. Despite the superior performance demonstrated by deep learning approaches over conventional methods in recent years, automatic LV segmentation remains an open challenge. The left ventricles of different patients appear in varying shapes, sizes, and positions in echocardiographic images, rendering prior knowledge useless. Moreover, deep learning methods require substantial training datasets and computational resources. In practical applications, there is a need for a model that delivers competitive performance within a limited computational budget.

Unfortunately, as shown in Table 4, high-performing methods tend to prioritize segmentation performance at the cost of high computational resources. For instance, Contrastive-Echo requires 31413.71 M FLOPs for inference, leading to high computational costs and lower adoption rates. Inspired by these observations, we introduce lightweight networks to significantly reduce computational costs. We experimented with various combinations of encoders and decoders, further reducing the number of parameters through efficient feature processing modules. Our model configuration outperforms others in terms of balancing computational cost and segmentation performance.

Specifically, we compare the performance of different lightweight encoder-decoder combinations for the task of left ventricular segmentation in echocardiographic images. We found that the model combining the SwiftFormer encoder with the ULite decoder, along with SCConv units and PolyLoss function, outperforms all other models on the EchoNet-Dynamic dataset, with advantages in parameter count and computational load. Specifically, the SwiftFormer encoder, with its efficient attention mechanism and parameter sharing strategy, significantly reduces the number of parameters, while the ULite decoder, through its streamlined design, lowers computational costs. In addition, as shown by the visual results in Fig. 5, the introduction of the SCConv unit enhances the model’s ability to capture image details, while the PolyLoss loss function helps the network better learn edge features, thereby improving the accuracy of segmentation. To the best of our knowledge, this combination of lightweight architectures has not been studied on this dataset before. It aligns with the trend of medical imaging solutions transitioning from laboratories to patient bedside, where efficient model designs can enable real-time image segmentation on mobile devices or embedded systems, providing instant support for clinical decision-making.

It is clear from Table 4 that our proposed method is both competitive and efficient in terms of computational resources. As shown in Table 1, our novel improvements, whether introduced individually or combined, enhance the model’s segmentation performance. Visual inspection in Fig. 6 indicates an overall high quality of our method’s segmentation. Occasionally, our approach fails to segment small regions of the left ventricle. In the future, we will attempt to improve segmentation performance using ensembles of lightweight models.

Conclusion

In this work, we investigate the performance of representative encoder/decoder architectures on the task of left ventricular segmentation. When comparing encoders, we find that combining Polyloss with the SwiftFormer backbone always yields superior performance compared to BCELoss. The SwiftFormer module exhibits strong capabilities in feature extraction from images, but there is still room for enhancement; by incorporating SCConv modules during downsampling, the model’s performance becomes even more competitive. Conversely, in the decoder comparison, U-Lite emerges as the overall winner, by combining Axial Depthwise Convolution modules with point convolutions, slightly increasing segmentation accuracy while reducing the parameter count and computational complexity of the upsampling modules. Experiments on the EchoNet-Dynamic dataset demonstrate that our model has fewer parameters and lower computational complexity, achieving promising results.

Acknowledgements

This research was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant number 32460389), Yunnan Fundamental Research Projects (grant number 202201AT070006), and Yunnan Postdoctoral Research Fund Projects (grant number ynbh20057).

Author contributions

Z.Q. designed and performed the experiments and wrote the first draft of the manuscript. T.H. conceptualized the study and revised the manuscript. J.W. provided the experimental setting, offered guidance, and was responsible for reviewing, editing, revising the manuscript, and providing financial support. Z.Y. reviewed the manuscript and provided supervision.

Data availability

The data supporting the findings of this study are derived from the open-source dataset EchoNet-Dynamic, which can be accessed at https://echonet.github.io/dynamic/. Permission is granted to view and use the EchoNet-Dynamic dataset without charge for personal, non-commercial research purposes only.

Declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Schmidhuber, J. Deep learning in neural networks: an overview. Neural Netw.61, 85–117. 10.1016/j.neunet.2014.09.003 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Krizhevsky, A., Sutskever, I. & Hinton, G. E. ImageNet classification with deep convolutional neural networks. In 2012 Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems (NeurIPS). 25 (2012).

- 3.Wang, Z. Deep learning in medical ultrasound image segmentation: A review. Preprint at (2020). https://arxiv.org/abs/2002.07703

- 4.Fiorentino, M. C., Villani, F. P., Cosmo, M. D., Frontoni, E. & Moccia, S. A review on deep-learning algorithms for fetal ultrasound-image analysis. Med. Image Anal.83, 1361–8415. 10.1016/j.media.2022.102629 (2023). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Muñoz, M., Cosarinsky, G., Cruza, J. F. & Camacho, J. Deep learning-based lung ultrasound image segmentation for real-time analysis. In 2023 IEEE International Ultrasonics Symposium (IUS). 1–4 (2023).

- 6.Hu, Y. et al. Beyond one-to-one: Rethinking the referring image segmentation. In. Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV). 4067–4077 (2023). (2023).

- 7.Chen, L. C. et al. Semantic image segmentation with deep convolutional nets, atrous convolution, and fully connected CRFs. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell.40 (4), 834–848. 10.1109/TPAMI.2017.2699184 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ronneberger, O., Fischer, P. & Brox, T. U-net: Convolutional networks for biomedical image segmentation. In 2015 Medical image computing and computer-assisted intervention (MICCAI). 234–241 (2015).

- 9.Xu, M., Ma, Q., Zhang, H., Kong, D. & Zeng, T. MEF-UNet: an end-to-end ultrasound image segmentation algorithm based on multi-scale feature extraction and fusion. Comput. Med. Imaging Graph. 114, 102370. 10.1016/j.compmedimag.2024.102370 (2024). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Li, X., Hu, Y. & Cooperative-Net An end-to-end multi-task interaction network for unified reconstruction and segmentation of MR image. Comput. Methods Programs Biomed.245, 108045. 10.1016/j.cmpb.2024.108045 (2024). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chen, W., Li, Y., Dang, B., Zhang, Y. & EHSNet End-to-end holistic learning network for large-size remote sensing image semantic segmentation. Preprint at (2022). https://arxiv.org/abs/2211.11316

- 12.Isensee, F. et al. nnU-Net: Self-adapting framework for U-Net-based medical image segmentation. Preprint at (2018). https://arxiv.org/abs/1809.10486

- 13.Peng, Y., Sonka, M. & Chen, D. Z. U-Net v2: Rethinking the skip connections of U-Net for medical image segmentation. Preprint at (2023). https://arxiv.org/abs/2311.17791

- 14.Qi, Y., He, Y., Qi, X., Zhang, Y. & Yang, G. Dynamic snake convolution based on topological geometric constraints for tubular structure segmentation. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV). 6070–6079 (2023). (2023).

- 15.Painchaud, N., Duchateau, N., Bernard, O. & Jodoin, P. Echocardiography segmentation with enforced temporal consistency. IEEE Trans. Med. Imaging. 41 (10), 2867–2878. 10.1109/TMI.2022.3173669 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ali, Y., Janabi-Sharifi, F. & Beheshti, S. Echocardiographic image segmentation using deep Res-U network. Biomed. Signal. Process. Control. 64, 102248. 10.1016/j.bspc.2020.102248 (2021). [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lei, Y. et al. Echocardiographic image multi-structure segmentation using Cardiac-SegNet. Med. Phys.48 (5), 2426–2437. 10.1002/mp.14818 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wu, H. et al. Semi-supervised segmentation of echocardiography videos via noise-resilient spatiotemporal semantic calibration and fusion. Med. Image Anal.78, 102397. 10.1016/j.media.2022.102397 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fatima, N., Afrakhteh, S., Iacca, G. & Demi, L. Automatic segmentation of 2D echocardiography ultrasound images by means of generative adversarial network. IEEE Trans. Ultrason. Ferroelectr. Freq. Control. 10.1109/TUFFC.2024.3393026 (2024). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ouyang, D. et al. Video-based AI for beat-to-beat assessment of cardiac function. Nature580 (7802), 252–256. 10.1038/s41586-020-2145-8 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Thomas, S., Gilbert, A. & Ben-Yosef, G. Light-weight spatio-temporal graphs for segmentation and ejection fraction prediction in cardiac ultrasound. In International Conference on Medical Image Computing and Computer-Assisted Intervention (MICCAI). 380–390 (2022). (2022).

- 22.Leclerc, L. et al. Deep learning for segmentation using an open large-scale dataset in 2D echocardiography. IEEE Trans. Med. Imaging. 38 (9), 2198–2210. 10.1109/TMI.2019.2900516 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Saeed, M., Muhtaseb, R. & Yaqub, M. Contrastive pretraining for echocardiography segmentation with limited data. In 2022 Medical Image Understanding and Analysis (MIUA). 680–691 (2022).

- 24.Ouyang, D. et al. Echonet-dynamic: a large new cardiac motion video data resource for medical machine learning. In 2019 NeurIPS ML4H Workshop. 1–11 (2019).

- 25.Li, J., Wen, Y., He, L. & Scconv Spatial and channel reconstruction convolution for feature redundancy. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR). 6153–6162 (2023). (2023).

- 26.Wu, Y. & He, K. Group normalization. In 2018 Proceedings of the European conference on computer vision (ECCV). 3–19 (2018).

- 27.Mohsen, H., El-Dahshan, E. A., El-Horbaty, E. M. & Salem, A. M. Classification using deep learning neural networks for brain tumors. Fut Comput. Inf. J.3 (1), 68–71. 10.1016/j.fcij.2017.12.001 (2018). [Google Scholar]

- 28.Shaker, A. et al. Swiftformer: Efficient additive attention for transformer-based real-time mobile vision applications. In. Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV). 17425–17436 (2023). (2023).

- 29.Dinh, B., Nguyen, T., Tran, T. & Pham, V. 1 M parameters are enough? A lightweight CNN-based model for medical image segmentation. In 2023 Asia Pacific Signal and Information Processing Association Annual Summit and Conference (APSIPA ASC). 1279–1284 (2023).

- 30.Leng, Z. et al. Polyloss: a polynomial expansion perspective of classification loss functions. Preprint at. (2022). https://arxiv.org/abs/2204.12511

- 31.Liu, H. et al. A scalable stochastic second-order optimizer for language model pre-training. Preprint at. (2023). https://arxiv.org/abs/2305.14342

- 32.Chen, T., Kornblith, S., Norouzi, M. & Hinton, G. A simple framework for contrastive learning of visual representations. In 2020 International conference on machine learning (PMLR). 1597–1607 (2020).

- 33.Ma, N., Zhang, X., Zheng, H. & Sun, J. Shufflenet v2: Practical guidelines for efficient cnn architecture design. In Proceedings of the European conference on computer vision (ECCV). 116–131 (2018). (2018).

- 34.Kavyashree, P. S. P. & El-Sharkawy, M. Compressed mobilenet v3: a light weight variant for resource-constrained platforms. In 2021 IEEE 11th annual computing and communication workshop and conference (CCWC). 0104–0107 (2021).

- 35.Maaz, M. et al. Edgenext: efficiently amalgamated cnn-transformer architecture for mobile vision applications. In 2022 European conference on computer vision (ECCV). 3–20 (2022).

- 36.Valanarasu, J. M. J., Patel, V. M. & Unext Mlp-based rapid medical image segmentation network. In 2022 International conference on medical image computing and computer-assisted intervention (MICCAI). 23–33 (2022).

- 37.Han, Z., Jian, M., Wang, G. & ConvUNeXt An efficient convolution neural network for medical image segmentation. Knowl. -Based Syst.253, 109512. 10.1016/j.knosys.2022.109512 (2022). [Google Scholar]

- 38.Chen, L., Zhu, Y., Papandreou, G., Schroff, F. & Adam, H. Encoder-decoder with atrous separable convolution for semantic image segmentation. In Proceedings of the European conference on computer vision (ECCV). 801–818 (2018). (2018).

- 39.Hu, P. et al. Temporally distributed networks for fast video semantic segmentation. In 2020 Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR). 8818–8827 (2020).

- 40.Li, X. et al. Expectation-maximization attention networks for semantic segmentation. In 2019 Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF international conference on computer vision (ICCV). 9167–9176 (2019).

- 41.Chen, J. et al. Transunet: Transformers make strong encoders for medical image segmentation. Preprint at (2021). https://arxiv.org/abs/2102.04306

- 42.Lou, A., Guan, S. & Loew, M. DC-UNet: rethinking the U-Net architecture with dual channel efficient CNN for medical image segmentation. In Medical Imaging 2021: Image Processing. 11596, 758–768 (2021).

- 43.Chen, E., Cai, Z. & Lai, J. Weakly supervised semantic segmentation of echocardiography videos via multi-level features selection. In 2022 Chinese Conference on Pattern Recognition and Computer Vision (PRCV). 388–400 (2022).

- 44.Maani, F. et al. Simplifying left ventricular segmentation in 2D + time echocardiograms with self- and weakly-supervised learning. Preprint at (2023). https://arxiv.org/abs/2310.00454 [DOI] [PubMed]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data supporting the findings of this study are derived from the open-source dataset EchoNet-Dynamic, which can be accessed at https://echonet.github.io/dynamic/. Permission is granted to view and use the EchoNet-Dynamic dataset without charge for personal, non-commercial research purposes only.