Abstract

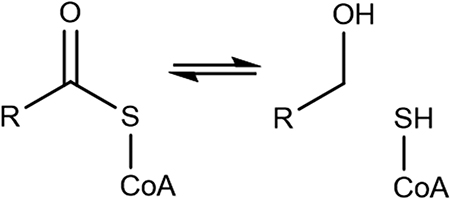

Thiohemiacetals are key intermediates in the active sites of many enzymes catalyzing a variety of reactions. In the case of Pseudomonas mevalonii 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl coenzyme A reductase (PmHMGR), this intermediate connects the two hydride transfer steps where a thiohemiacetal is the product of the first hydride transfer and its breakdown forms the substrate of the second one, serving as the intermediate during cofactor exchange. Despite the many examples of thiohemiacetals in a variety of enzymatic reactions, there are few studies that detail their reactivity. Here, we present computational studies on the decomposition of the thiohemiacetal intermediate in PmHMGR using both QM-cluster and QM/MM models. This reaction mechanism involves a proton transfer from the substrate hydroxyl to an anionic Glu83 followed by a C–S bond elongation stabilized by a cationic His381. The reaction provides insight into the varying roles of the residues in the active site that favor this multistep mechanism.

Graphical Abstract

INTRODUCTION

Sulfur-based compounds play a key role in biochemical processes of prokaryotic and eukaryotic cells.1–3 These compounds serve a broad range of purposes from serving as building blocks in fatty acid biosynthesis to post-translational modification.4,5 Enzymes have also evolved to make and manipulate the carbon–sulfur bonds.6 For example, cysteine residues in catalytic sites can serve as nucleophiles for acyl groups resulting in the formation of thiohemiacetals—a common tetrahedral intermediate.7 In these cases, thiohemiacetal intermediates are covalently bound enzyme–substrate (ES) complexes.8–10 The decomposition of these tetrahedral intermediates facilitates other chemical reactions such as hydride and acetyl transfers in an enzyme catalytic site.10,11

Thiohemiacetal intermediates are found in a variety of enzyme classes (Table 1). Cysteine peptidases cleave a carbon–sulfur bond through covalent catalysis involving an active site cysteine.12,13 UDP-glucose and some aldehyde dehydrogenases form a covalently bound ES thiohemiacetal complex using an active site cysteine, which is hydrolyzed by an activated water molecule.8–10 Thioester and carboxylic acid reductases are NAD(P)H dependent and use an alternative nucleophile such as a negatively charged residue to decompose the thiohemiacetal intermediate.14–17 Thioesterases, a class of enzymes that cleave a C–S bond, have a thioorthoester tetrahedral intermediate.18,19 Glutathione dependent human glyoxalase I and II enzymes catalyze thiohemiacetal decomposition through a metal ion coordination and active site water molecules.20–22 While the molecular mechanism of the glutathione independent human protein deglycase (DJ-1) is not clear, they are known to have a conserved cysteine and form a thiohemiacetal intermediate during the detoxification of methylglyoxal to D-lactate.23–26 The structures of most enzymes summarized in Table 1 with a cocrystallized thiohemiacetal ligand are not available even though experimental studies suggest that these reactions proceed through a thiohemiacetal intermediate.27 This is presumably due to the rapid decomposition of the tetrahedral thiohemiacetal intermediates that makes it challenging to isolate the intermediate. As a result, the mechanistic details of these reactions, such as the role of the active site residues or the transition state geometries are not well understood.

Table 1.

Examples of Enzymes with Thiohemiacetal Intermediates

UDP-glucose 6-dehydrogenase |

Aldehyde dehydrogenase (AMSDH) |

Cysteine Peptidase |

Alcohol forming fatty acyl-CoA reductase |

Short chain reductase |

HMG-CoA reductase |

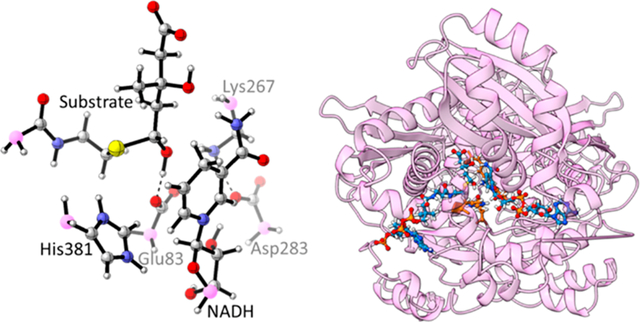

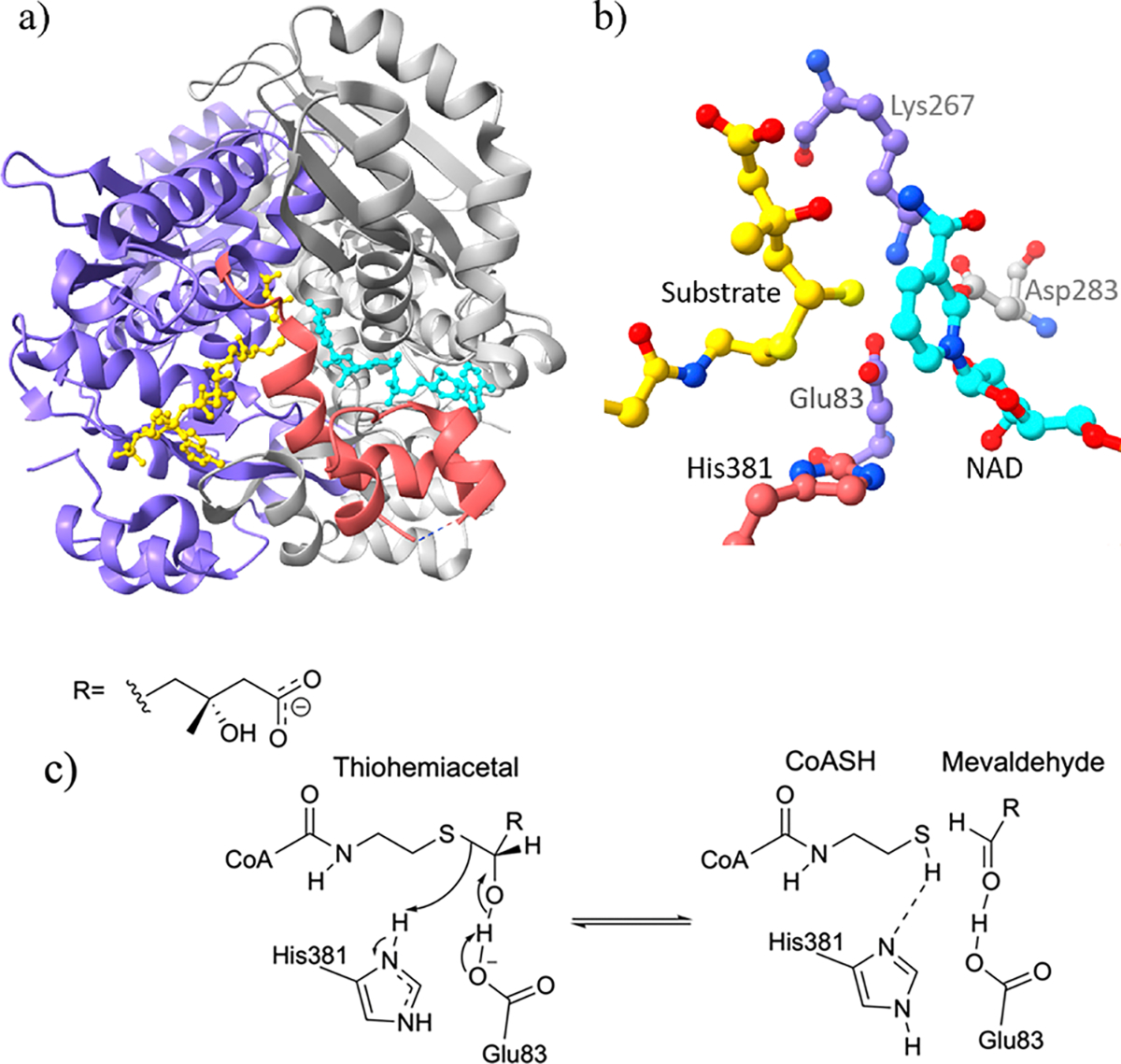

This paper provides a case study of a base-catalyzed thiohemiacetal decomposition in Pseudomonas mevalonii 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl coenzyme A reductase (PmHMGR).28,29 This enzyme, shown in Figure 1a,b, is a homodimer with a flexible three-helix C-terminal domain that catalyzes the first committed step of the mevalonate pathway for the synthesis of isoprenoids in bacteria.30–32 Thiohemiacetal decomposition converts the product of the first hydride transfer that is likely to be present during the cofactor exchange into the substrate of the second hydride transfer (Figure S1).33 This entails two proton transfers and a C–S bond cleavage producing coenzyme A and mevaldehyde from mevaldyl-CoA (thiohemiacetal) (Figure 1c). Based on previous work, Glu83 accepts the proton and His381 donates the proton to the thiolate anion.29,34–36 Glu83 was also found to be the proton acceptor as it resulted in geometries that are similar to the active site in the crystal structures.37 Models with Lys267 as the proton acceptor result in interaction between the unprotonated Glu83 and protonated His381—an interaction not observed in the crystal structures. Because His381 is not oriented toward the thiolate sulfur atom, the negative charge development is not effectively stabilized.37 Based on this previous work and our suggested PmHMGR mechanism,33,34 the protonation state of Glu83 was modeled as negatively charged and His381 was modeled as positively charged. Through site-directed mutagenesis experiments, the role of cysteine residues in this reaction mechanism was concluded to be maintenance of structural stability rather than catalytic activity.38

Figure 1.

(a) PmHMGR crystal structure (PDB: 4i4b39) showing two monomers (chain A in purple), flap domain in pink ribbon, and ligands in ball–stick models (NAD in cyan and dithiohemiacetal in yellow). (b) PmHMGR catalytic site showing ligands and conserved residues. (c) The mevaldyl-CoA decomposition reaction showing Glu83 as the proton acceptor and His381 as the proton donor.

Both thiohemiacetal decomposition and cofactor exchange occur between the two hydride transfers. A similar case is suggested for UDP-glucose dehydrogenase which also favors NAD+/NADH exchange only after thiohemiacetal formation.27 The cofactor (NADH/NAD+) maintains the active site geometry, and its oxidation state affects the site pH.28 Based on the proposed reaction mechanism, thiohemiacetal decomposition only occurs in the presence of NADH.34 The product of thiohemiacetal decomposition—mevaldehyde—is absent in solution implying that the flap domain remains closed while mevaldehyde is bound to the catalytic site.28,30,40,41 For mevaldehyde to be transformed into mevalonate during the second hydride transfer, an additional NADH molecule is required which can only be obtained by exchanging an oxidized cofactor (NAD+) for a reduced one (NADH).33 This cofactor exchange is suggested to occur before the thiohemiacetal decomposition (Figures S1 and S2). Therefore, the models discussed in this paper contain NADH as the cofactor while the results for models with NAD+ are summarized in the Supporting Information and resemble those of NADH models.

COMPUTATIONAL METHODS

There are two major approaches to computational studies of enzymatic reactions: QM-cluster/theozyme and QM/MM.42,43 Both have their own set of advantages, challenges, and methods to offset the challenges. QM-cluster methods are much faster and can be used with more accurate DFT functionals but do not describe the effects of the protein environment.42 This challenge is minimized by use of a dielectric constant similar to a protein environment. While QM/MM does have the protein electrostatic environment, it has the challenge of treating the QM/MM boundary/partition, for instance, how the charges in the MM layer interact with QM density.43 This has been minimized by electronic embedding of MM layer charges. In our case, we use both methods to confirm the transition state geometry of the thiohemiacetal decomposition in PmHMGR.

Theozyme Models.

Theoretical enzymes or “theozymes” are simplified enzyme active site models that contain the reactive moieties of ligands and the active site residues capped with a terminal methyl group.44–46 The terminal methyl group’s carbon is frozen in place to mimic attachment of the functional moiety to the rest of the protein or ligand (Figure 2). Theozymes are constructed by averaging an equilibrated segment of an all-atom molecular dynamics (MD) simulation trajectory of a crystal structure (for details, see the inpcrd and prmtop files in the Supporting Information). These models enable a study of the enzymatic reaction mechanism using electronic structure methods whose cost and time of calculation scale with the number of atoms in a system.42 For this reason, it is crucial to limit the selection of ligand and residue moieties to those that conserve the active site conformation of the enzyme. The theozyme model constructed for this reaction are shown in Figure 2 and contain 86 atoms.

Figure 2.

Theozyme model for PmHMGR thiohemiacetal decomposition highlighting the frozen carbon atoms (pink) which mimic attachment to the rest of the protein. Other colors: gray = C, white = H, blue = N, red = O, and yellow = S.

We used the crystal structure of PmHMGR with a dithiohemiacetal ligand (Figure 1b)—a slow substrate—and the NADH cofactor (PDB ID: 4i4b; resolution 1.78 Å) to construct the theozyme model (Figure 2) for the decomposition of mevaldyl-CoA to mevaldehyde.39 The thiol group of the dithiohemiacetal was changed to hydroxyl to give the native mevaldyl-CoA intermediate. We calculated the transition structure (TS) for the thiohemiacetal decomposition involving the breakage of the C–S bond in the theozyme models using DFT calculations in Gaussian16 at both the B3LYP/6–31G(d,p) and M06/6–31G(d,p) levels of theory47,48 to control for the influence of dispersion. The reactant and product geometries are optimized to a minimum. The solvent effects on the energies of the reactant, TS, and products are incorporated using a polarizable continuum model (PCM) within the self-consistent reaction field framework (SCRF). The internal dielectric constant (ε) was set to 4, which mimics the internal dielectric constant of a protein.49

The transition state was verified by vibrational frequency analysis corresponding to the proton transfer (from substrate hydroxyl oxygen to Glu83 carbonyl oxygen) and C–S bond elongation. Analysis of bond lengths and restrained electrostatic potential (RESP) partial charges highlight the difference in the reactant, transition state, and product geometries.50,51

QM/MM Models.

The intermediates and transition states of reactions in the active sites of enzymes are stabilized by extensive hydrogen-bonding networks and noncovalent interactions that inherently lower the energy of activation of a given reaction.52 The hybrid QM/MM method partitions the protein system into a QM layer, similar to the theozyme model (Figure 2), and an MM layer which contains a large number of residues around the QM layer/defined active site.53 To verify that the theozyme constructed was a good model for studying this reaction, we identified the transition state in a protein environment using the ONIOM methods with the electronic embedding scheme, which incorporates the MM layer partial charges in the QM Hamiltonian.54,55 The QM layer in this study was again treated with two exchange-correlation functionals (B3LYP/6–31G(d,p) and M06/6–31G(d,p)) while the MM layer was treated with the Amber force field (FF99SB).48,56 The partition between the QM and MM layer was only between C–C bonds for all residues using the hydrogen atom link-atom boundary scheme.43 All systems were prepared using TAO and optimized in Gaussian16.47,57

An equilibrated structure of 4i4b was used to construct this model by selecting all residues within an 8 Å radius (shown as the gray surface model in Figure 3a) of the catalytic residues (Glu83, Lys267, His381, and Asp283) (orange stick model in Figure 3a) and ligands (blue ball and stick model in Figure 3a). The entire system had 1157 atoms (Figure 3a, gray surface), and the QM layer included 106 atoms (Figure 3b). All residues in the MM layer beyond 4 Å of the QM layer atoms were frozen in place, which was shown to be a reasonable approximation by a systematic study of frozen residues in the studies of enzymatic reactions.58 The MM layer composed of a few unfrozen residues—such as Ser85—provided an insight into the protein environment as it adjusted to the transition state geometry. The reactant and product QM/MM models were optimized to a minimum while the transition state was verified as having exactly one imaginary frequency corresponding to the reaction coordinate.

Figure 3.

(a) QM/MM model composed of the 8 Å core (gray surface model) of 4i4b measured from the ligands and residues (ball and stick models). (b) QM layer with 106 atoms highlighting the atoms (pink) at the QM/MM partition.

RESULTS

When determining the essential residues to include in the theozyme model, omitting Asp283 resulted in Lys267 donating a proton to the oxygen atom. This suggests that Asp283 positions the amine group of Lys267 for stabilizing the developing negative charge on the thiohemiacetal oxygen atom. Lys267 also holds Glu83 in place by forming a hydrogen bond with the carboxylate oxygen not involved in the proton transfer. Eliminating Lys267, Asp283, or cofactor NADH resulted in the distortion of the enzymatic active site geometry. These moieties provide electrostatic interactions that are necessary to stabilize the transition state geometry. The first amide of the substrate was included to regulate the magnitude of C–S bond elongation making the theozyme model more representative of the enzyme active site.

Theozyme Transition State Model.

The TS geometry for the thiohemiacetal decomposition (Figure 4) shows a deprotonated Glu83 accepting a proton from the hydroxyl group of mevaldyl-CoA. As the O–H bond length in the hydroxyl group increases from 1.0 to 1.3 Å, a negative charge develops on this oxygen atom as indicated by the change in RESP partial atomic charges from −0.58 to −0.64 (Table 2).

Figure 4.

Reactant, transition state, and product geometries for mevaldyl-CoA decomposition calculated at M06/6–31G** showing the changes in bond lengths.

Table 2.

RESP Calculated at PW6B95/aug-cc-pVTZ ε = 4 for Theozyme and QM Layer Geometries Optimized at M06/6-31G** (Substrate Atoms Are Marked with *)

| theozyme |

QM layer |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| atom | R | TS | P | R | TS | P |

|

| ||||||

| O (Glu) | −0.72 | −0.63 | −0.63 | −0.78 | −0.15 | −0.44 |

| H* | 0.40 | 0.38 | 0.37 | 0.41 | 0.11 | 0.29 |

| O* | −0.58 | −0.64 | −0.52 | −0.59 | −0.56 | −0.43 |

| C* | 0.17 | 0.22 | 0.37 | 0.19 | 0.43 | 0.37 |

| S* | −0.45 | −0.60 | −0.68 | −0.46 | −0.64 | −0.27 |

| N (His) | −0.01 | −0.03 | −0.03 | −0.20 | −0.11 | −0.59 |

The previously single C–O bond of mevaldyl-CoA shortens from 1.37 to 1.32 Å, which results in elongation of the C–S single bond from 1.94 to 2.13 Å—an indication of C–S bond scission (Figure 4). The partial atomic charge analysis shows the developing negative charge on the S* atom as a positive charge develops on the C* (Table 2). The Nδ group of His381 stabilizes the negative charge on the thiolate S* atom to accommodate the greater negative partial charges on S* from −0.45 to −0.60 (Table 2). There is no significant change in the Nδ–H–S angle in the theozyme reactant, TS, and product geometries.

The crystal structure of PmHMGR (pdb code 4i4b) shows the imidazole ring of His381 to be parallel to the substrate sulfur atom. The MD simulation (details in the Supporting Information) from which these models were constructed showed the existence of both the parallel and the perpendicular orientations of His381 relative to S*. All reactant, TS, and product geometries in the theozyme model favor the perpendicular orientation as a result of the favored electrostatic interaction between the negative charge on S* and a more positive charge on Nδ of His381 relative to Nε (Figure 4).

QM/MM Transition State Model.

There are some differences between the theozyme and QM/MM TS geometry such as a relatively shorter C*–O* (1.26 Å compared to theozyme’s 1.32 Å) and Glu83 O–H* bonds in the QM layer (Figures 4 and S4). The theozyme TS has a greater negative charge on the thiohemiacetal oxygen atom relative to the charge in the QM/MM models. This could be a result of not only the shorter C–O bond lengths in the QM/MM model but also the amine group of the Lys267 residue having an extra methylene group in the QM layer which allows for greater flexibility and better stabilization of the developing negative charge. The partial atomic charge on C* is more positive (0.43) for the QM layer geometry than that on the theozyme geometry (0.22) (Table 2). Another major difference is that the cofactor ribose ring, included in the QM layer but not in the theozyme, limits the His381 imidazole ring rotation (Figure 5). The hydrogen bond between the Nε of His381 and the hydroxyl of the ribose is maintained for all R, TS, and P geometries (Figure S4).

Figure 5.

Overlay of the TS geometries from the theozyme and QM/MM models.

The geometry of the product in the QM layer (Figure S4) shows a neutral His381 and a thiol CoASH resulting from a second proton transfer. In contrast, the theozyme product geometry does not show the proton transfer from His381 to the CoA thiolate anion (Figure 4). This could be because the theozyme product is trapped in a local minimum, which also explains the energy difference between the QM layer and theozyme products (Figure 6). The QM/MM models could not be optimized to a low-energy (minimum) intermediate (INT), possibly due to the smaller difference in the relative energy of the INT and product state/lower deltaG for the second proton transfer in the protein environment.

Figure 6.

Activation and reaction energies (SCF single point calculations, relative to reactant, in kcal/mol) for the theozyme and QM layer (structures illustrated in Figures 4 and S4).

Single point energy calculations performed with different density functionals reveal a higher energy of activation for the theozyme model relative to the QM layer (Figures 6 and S3). Figure 6 highlights the energy at the best level of theory. Both calculations were performed in a polarized continuum solvent model with a dielectric constant of 4. The single point energy calculations indicate an endergonic reaction for the theozyme model but an exergonic reaction for the QM layer from QM/MM models. This is a result of the product state of the theozyme models being an intermediate at a minimum before the second proton transfer from His381 to the thiolate anion. The difference in energy between product geometries of the theozyme versus QM layer of the QM/MM model is about 6.7 kcal/mol (Figure 6; for results at other levels of theory see Figure S2). The activation energy of this reaction is comparable, with a difference of 2.2 kcal/mol, in the theozyme or QM/MM models (Figure 6).

DISCUSSION

Thiohemiacetal decomposition is not the rate-limiting reaction within PmHMGR, making experimental studies of the mechanism of this step of the overall reaction difficult. As a result, the computational studies presented here provide unique insights into the thiohemiacetal breakdown, many of which are expected to be transferable to the other enzymecatalyzed reactions involving thiohemiacetals (Tables 1 and S1). Previous computational studies on the first hydride transfer indicate a much higher energy of activation of 19–21 kcal/mol,33 which is consistent with the experimental rate of reaction of 1 s−1 to 1 m−1.38 The first hydride transfer is likely the rate-limiting step because the formation of the thiohemiacetal intermediate initiates the cofactor exchange followed by thiohemiacetal decomposition forming mevaldehyde, a subsequent intermediate that accepts the second hydride. MM/GBSA studies indicate that the thiohemiacetal–NADH complex has a lower binding energy relative to the thiohemiacetal–NAD+ complex.33 This favors the cofactor exchange (NAD+ to NADH) after the first hydride transfer but before thiohemiacetal decomposition. While the NAD theozyme model (Supporting Information) has a similar TS geometry to the NADH theozyme model, the former has the non-proton-accepting carboxyl oxygen of Glu83 oriented toward Asp283 and NAD+ instead of being right below Lys267 amine as in the latter case. The energy barrier for the NAD theozyme model when compared to the NADH theozyme model (calculated at B3LYP/6–31G**) was 2 kcal/mol higher. As suggested by studies on human HMGR, the proximity of Glu83 to Asp283 increases its pKa, which in thiohemiacetal decomposition would favor Glu83 to be protonated.59 Computational studies on the human HMGR also indicate the lowest activation free energies for a neutral Glu83 residue in the first hydride transfer.60 Glu83 is stabilized in the presence of NAD+ such that proton transfer is not favored, which could explain the higher binding energy and the orientation of the carboxyl oxygen in the theozyme models.

The computational studies allow dissection of the suggested roles of the individual catalytic residues of HMGR for conversion of the substrates and intermediates in the enzyme active site.29,36,40,61 Similar to the hydride transfer step the positively charged Lys267 serves as the oxyanion hole, stabilizing the negative charges developing on the substrate hydroxyl oxygen and the Glu83 carboxyl oxygen. Asp283 holds Lys267 in place, thereby maintaining the position of the oxyanion hole during catalysis. His381—a catalytic residue on the flap domain—has diverse roles that could enable processing multiple substrates and intermediates within the same active site of HMGR.33 During the first hydride transfer, His381 has a hydrogen bond with the carboxyl closer to the first amide of HMG-CoA.33 As seen from the crystal structures, Ser85 interacts with the first amide of CoA, orienting the substrate in place in the active site.39 Computational studies illustrate how the extensive hydrogen bond network between His381, Ser85, and the substrate amide controls the substrate orientation in the active site.33 The QM/MM geometry (Figure 5) shows that during the thiohemiacetal decomposition Ser85 sustains the hydrogen bond with the first amide of the substrate allowing the positively charged His381 to stabilize the negative charges on the thiolate. This orientation of the imidazole ring of His381 (Figures 5 and S4) not only favors proton donation (by Nδ) but also maintains the hydrogen bond network with the cofactor (using Nε). Experimental studies on the second hydride transfer of mammalian HMGR (class I) show a higher activity (WT enzyme) in the presence of CoASH.35 Conversely, there is a higher activity for the second reduction for the H865Q (equivalent to His381 in PmHMGR) mutant in the absence of CoA thiol.35 Previous computational studies on the second hydride transfer have shown that a neutral His381 maintains electrostatic interactions with CoA thiol.33 The product geometry of the QM/MM models (Figure S4) indicates a similar interaction between the Nδ of neutral His381 and the CoA thiol after proton transfer. The charged imidazole ring enables versatility of His381 in HMGR. The computational models in this work illustrate the transition/interplay of the suggested roles of His381, thereby contributing to our understanding of the mechanism/dynamics of the catalytic residues.

Hydrolysis of the thiohemiacetal intermediate with a water molecule is not a possible mechanism in HMGR because there is no conserved water molecule in the catalytic site. The thiohemiacetal intermediate can be exposed to the solvent during the cofactor exchange, but such a mechanism would also result in the mevaldehyde being hydrated as soon as it was formed which is unfavorable for the second hydride transfer.28 Mevaldehyde has been used to run half-reactions (one reduction in HMGRs) to give mevalonate, but extensive experimental studies have indicated that this intermediate does not leave the active site.30,38,40,62 While it is possible for this thiohemiacetal to be hydrolyzed by a water molecule, the subsequent reaction does not favor it, thereby making this a less favorable decomposition mechanism. Time-dependent crystallographic experiments also lack electron densities for conserved water molecules, show different orientations for catalytic residues, and show formation of C–S bond after a hydride transfer to mevalonate.63

Similar to other enzymes with thiohemiacetal intermediates,9,10,12,13 PmHMGR has cysteine residues, but unlike these enzymes, PmHMGR’s cysteine residues (Cys156 and Cys296) showed minimal effect on the enzyme activity when mutated to alanine.38 This verifies that PmHMGR thiohemiacetal decomposition is not facilitated by these cysteines.

HMGR is classified as an oxidoreductase, but its active site residues have similarities with dehydrogenases and thioesterases. Dehydrogenases commonly have a catalytic Cys and two basic residues, and thioesterases have at least one acidic residue to neutralize the thiolate anion.64 UDP-glucose 6-dehydrogenase, for instance, has both Asp and Glu in the active site that facilitate a proton transfer from the substrate and a nucleophilic attack on the thioester carbon, respectively.8,9,27 Acyl-CoA thioesterase—with a common hotdog fold—uses a cationic His and Ser to neutralize the thiolate anion resulting from the nucleophilic attack on the thioester carbon by an Asp activated water.18 Glutathione-dependent glyoxalase I and II enzymes bind Zn2+ and multiple Glu/Asp and His residues for catalysis of thiohemiacetals to carboxylic acids.20–22,65 The decomposition of the thiohemiacetal discussed here provides an alternative mechanism for active sites with at least one basic residue, one acidic residue, and no conserved water molecules or metal ions. NAD(P)H dependent thioester reductases, including fatty acyl-CoA reductases and some short chain reductases that catalyze the decomposition of the thiohemiacetal with a two- or four-electron reduction, would have a similar mechanism.14–16,66–69

CONCLUSION

In this work, we have investigated the base-catalyzed thiohemiacetal decomposition mechanism for PmHMGR that occurs in between two hydride transfers. This reaction is initiated by a negatively charged Glu83 accepting a proton from the thiohemiacetal hydroxyl. The resulting negative charge on the oxygen favors double-bond character between C*–O* (substrate), which promotes the C*–S* bond cleavage. A positively charged imidazole ring of His381 orients away from Ser85 and toward the thiolate to stabilize the negative charge while maintaining the electrostatic interactions with the ribose of NADH. For the PmHMGR active site, the thiohemiacetal decomposition has a barrier of about 7 kcal/mol, and the mechanism discussed here can serve as a model for other similar catalytic sites such as fatty alcohol forming fatty acyl-CoA reductase.16,67,68 The results described here will also serve as a starting point for the development of transition state force fields that allow microsecond MD simulations at the transition state of a reaction to study larger-scale changes of the protein structure to stabilize the transition state.70,71

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health grant (R01GM111645) to C.V.S., P.H., and O.W. H.N.P and B.E.H. are fellows of the Chemistry-Biochemistry-Biology Interface (CBBI) program at the University of Notre Dame, supported by training grant T32GM075762 from NIGMS.

Footnotes

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

ASSOCIATED CONTENT

Supporting Information

The Supporting Information is available free of charge at https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acs.jpcb.2c08969.

Additional figures; reactant, transition state, and product geometries of NAD+ theozyme models, NADH theozyme models, and NADH QM-layer (from QM/MM models) (PDF)

Input (topology and input coordinate) and RMSD analysis files for MD simulations in Amber (ZIP)

Complete contact information is available at: https://pubs.acs.org/10.1021/acs.jpcb.2c08969

Contributor Information

Himani N. Patel, Department of Chemistry and Biochemistry, University of Notre Dame, Notre Dame, Indiana 46556, United States

Brandon E. Haines, Department of Chemistry, Westmont College, Santa Barbara, California 93108, United States

Cynthia V. Stauffacher, Department of Biological Sciences, Purdue University, West Lafayette, Indiana 47907, United States

Paul Helquist, Department of Chemistry and Biochemistry, University of Notre Dame, Notre Dame, Indiana 46556, United States.

Olaf Wiest, Department of Chemistry and Biochemistry, University of Notre Dame, Notre Dame, Indiana 46556, United States.

REFERENCES

- (1).Burini RC; Kano HT; Yu Y-M The Life Evolution on the Sulfur Cycle: From Ancient Elemental Sulfur Reduction and Sulfide Oxidation to the Contemporary Thiol-Redox Challenges. In Glutathione in Health and Disease; IntechOpen: 2018; pp 9–26. [Google Scholar]

- (2).Mueller EG Trafficking in Persulfides: Delivering Sulfur in Biosynthetic Pathways. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2006, 2, 185–194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (3).Richter M Functional Diversity of Organic Molecule Enzyme Cofactors. Nat. Prod. Rep. 2013, 30, 1324–1345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (4).Beld J; Sonnenschein EC; Vickery CR; Noel JP; Burkart MD The Phosphopantetheinyl Transferases: Catalysis of a Post-Translational Modification Crucial for Life. Nat. Prod. Rep. 2014, 31, 61–108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (5).Shigi N Biosynthesis and Functions of Sulfur Modifications in TRNA. Front. Genet. 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (6).Dunbar KL; Scharf DH; Litomska A; Hertweck C Enzymatic Carbon-Sulfur Bond Formation in Natural Product Biosynthesis. Chem. Rev. 2017, 117, 5521–5577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (7).Cleary JA; Doherty W; Evans P; Malthouse JPG Quantifying Tetrahedral Adduct Formation and Stabilization in the Cysteine and the Serine Proteases. Biochim. Biophys. Acta - Proteins Proteomics 2015, 1854, 1382–1391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (8).Huang W; Llano J; Gauld JW A DFT Study on the Catalytic Mechanism of UDP-Glucose Dehydrogenase. Can. J. Chem. 2010, 88, 804–814. [Google Scholar]

- (9).Eixelsberger T; Brecker L; Nidetzky B Catalytic Mechanism of Human UDP-Glucose 6-Dehydrogenase: In Situ Proton NMR Studies Reveal That the C-5 Hydrogen of UDP-Glucose Is Not Exchanged with Bulk Water during the Enzymatic Reaction. Carbohydr. Res. 2012, 356, 209–214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (10).Huo L; Davis I; Liu F; Andi B; Esaki S; Iwaki H; Hasegawa Y; Orville AM; Liu A Crystallographic and Spectroscopic Snapshots Reveal a Dehydrogenase in Action. Nat. Commun. 2015, 6, 1–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (11).Paiva P; Sousa SF; Ramos MJ; Fernandes PA Understanding the Catalytic Machinery and the Reaction Pathway of the Malonyl-Acetyl Transferase Domain of Human Fatty Acid Synthase. ACS Catal. 2018, 8, 4860–4872. [Google Scholar]

- (12).Gisdon FJ; Bombarda E; Ullmann GM Serine and Cysteine Peptidases: So Similar, Yet Different. How the Active-Site Electrostatics Facilitates Different Reaction Mechanisms. J. Phys. Chem. B 2022, 126, 4035–4048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (13).Shokhen M; Khazanov N; Albeck A The Mechanism of Papain Inhibition by Peptidyl Aldehydes. Proteins 2011, 79, 975–985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (14).Chhabra A; Haque AS; Pal RK; Goyal A; Rai R; Joshi S; Panjikar S; Pasha S; Sankaranarayanan R; Gokhale RS Nonprocessive [2 + 2]e - off-Loading Reductase Domains from Mycobacterial Nonribosomal Peptide Synthetases. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2012, 109, 5681–5686. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (15).Mullowney WM; McClure RA; Robey MT; Kelleher NL; Thomson RJ Natural Products from Thioester Reductase Containing Biosynthetic Pathways. Nat. Prod. Rep. 2018, 35, 847–878. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (16).Willis RM; Wahlen BD; Seefeldt LC; Barney BM Characterization of a Fatty Acyl-CoA Reductase from Marinobacter Aquaeolei VT8: A Bacterial Enzyme Catalyzing the Reduction of Fatty Acyl-CoA to Fatty Alcohol. Biochemistry 2011, 50, 10550–10558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (17).Gahloth D; Dunstan MS; Quaglia D; Klumbys E; Lockhart-Cairns MP; Hill AM; Derrington SR; Scrutton NS; Turner NJ; Leys D Structures of Carboxylic Acid Reductase Reveal Domain Dynamics Underlying Catalysis. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2017, 13, 975–981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (18).Cantu DC; Ardevol A; Rovira C; Reilly PJ Molecular Mechanism of a Hotdog-Fold Acyl-CoA Thioesterase. Chem.—Eur. J 2014, 20, 9045–9051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (19).Chisuga T; Miyanaga A; Kudo F; Eguchi T Structural Analysis of the Dual-Function Thioesterase SAV606 Unravels the Mechanism of Michael Addition of Glycine to an α,β-Unsaturated Thioester. J. Biol. Chem. 2017, 292, 10926–10937. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (20).Himo F; Siegbahn PEM Catalytic Mechanism of Glyoxalase I: A Theoretical Study. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2001, 123, 10280–10289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (21).Cameron AD; Ridderström M; Olin B; Kavarana MJ; Creighton DJ; Mannervik B Reaction Mechanism of Glyoxalase I Explored by an X-Ray Crystallographic Analysis of the Human Enzyme in Complex with a Transition State Analogue. Biochemistry 1999, 38, 13480–13490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (22).Jafari S; Ryde U; Irani M Catalytic Mechanism of Human Glyoxalase I Studied by Quantum-Mechanical Cluster Calculations. J. Mol. Catal. B Enzym. 2016, 131, 18–30. [Google Scholar]

- (23).Ghosh A; Kushwaha HR; Hasan MR; Pareek A; Sopory SK; Singla-Pareek SL Presence of Unique Glyoxalase III Proteins in Plants Indicates the Existence of Shorter Route for Methylglyoxal Detoxification. Nat. Sci. Reports 2016, 6, 1–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (24).Andreeva A; Bekkhozhin Z; Omertassova N; Baizhumanov T; Yeltay G; Akhmetali M; Toibazar D; Utepbergenov D The Apparent Deglycase Activity of DJ-1 Results from the Conversion of Free Methylglyoxal Present in Fast Equilibrium with Hemithioacetals and Hemiaminals. J. Biol. Chem. 2019, 294, 18863–18872. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (25).Maksimovic I; Finkin-Groner E; Fukase Y; Zheng Q; Sun S; Michino M; Huggins DJ; Myers RW; David Y Deglycase-Activity Oriented Screening to Identify DJ-1 Inhibitors. R. Soc. Chem. Med. Chem. 2021, 12, 1232–1238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (26).Choi D; Kim J; Ha S; Kwon K; Kim E-H; Lee H-Y; Ryu K-S; Park C Stereospecific Mechanism of DJ-1 Glyoxalases Inferred from Their Hemithioacetal-containing Crystal Structures. FEBS J. 2014, 281, 5447–5462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (27).Egger S; Chaikuad A; Klimacek M; Kavanagh KL; Oppermann U; Nidetzky B Structural and Kinetic Evidence That Catalytic Reaction of Human UPD-Glucose 6-Dehydrogenase Involves Covalent Thiohemiacetal and Thioester Enzyme Intermediates. J. Biol. Chem. 2012, 287, 2119–2129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (28).Veloso D; Cleland WW; Porter JW PH Properties and Chemical Mechanism of Action of 3-Hydroxy-3-Methylglutary Coenzyme A Reductase. Biochemistry 1981, 20, 887–894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (29).Darnay BG; Wang Y; Rodwell VW Identification of the Catalytically Important Histidine of 3-Hydroxy-3- Methylglutaryl-Coenzyme A Reductase. J. Biol. Chem. 1992, 267, 15064–15070. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (30).Qureshi N; Dugan RE; Cleland WW; Porter JW Kinetic Analysis of the Individual Reductive Steps Catalyzed by Beta-Hydroxy-Beta-Methylglutaryl-Coenzyme A Reductase Obtained from Yeast. Biochemistry 1976, 15, 4191–4197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (31).Boucher Y; Huber H; L’Haridon S; Stetter KO; Doolittle WF Bacterial Origin for the Isoprenoid Biosynthesis Enzyme HMGCoA Reductase of the Archaeal Orders Thermoplasmatales and Archaeoglobales. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2001, 18, 1378–1388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (32).Bochar DA; Stauffacher CV; Rodwell VW Sequence Comparisons Reveal Two Classes of 3-Hydroxy-3- Methylglutaryl Coenzyme A Reductase. Mol. Genet. Metab. 1999, 66, 122–127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (33).Haines BE; Steussy CN; Stauffacher CV; Wiest O Molecular Modeling of the Reaction Pathway and Hydride Transfer Reactions of HMG-CoA Reductase. Biochemistry 2012, 51, 7983–7995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (34).Haines BE; Wiest O; Stauffacher CV The Increasingly Complex Mechanism of HMG-CoA Reductase. Acc. Chem. Res. 2013, 46, 2416–2426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (35).Frimpong K; Rodwell VW Catalysis by Syrian Hamster 3-Hydroxy-3-Methylglutaryl-Coenzyme A Reductase. Proposed Roles of Histidine 865, Glutamate 558, and Aspartate 766. J. Biol. Chem. 1994, 269, 11478–11483. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (36).Omkumar RV; Rodwell VW Phosphorylation of Ser871 Impairs the Function of His865 of Syrian Hamster 3-Hydroxy-3-Methylglutaryl-CoA Reductase. J. Biol. Chem. 1994, 269, 16862–16866. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (37).Haines BE Computational Studies on the Mechanism of HMG-CoA Reductase and the Grignard SRN1 Reaction. Ph.D. Dissertation, University of Notre Dame, Notre Dame, IN, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- (38).Jordan-Starck TC; Rodwell VW Role of Cysteine Residues in Pseudomonas Mevalonii 3-Hydroxy-3-Methylglutaryl-CoA Reductase. Site-Directed Mutagenesis and Characterization of the Mutant Enzymes. J. Biol. Chem. 1989, 264, 17919–17923. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (39).Steussy CN; Critchelow CJ; Schmidt T; Min J-K; Wrensford LV; Burgner JW; Rodwell VW; Stauffacher CV A Novel Role for Coenzyme A during Hydride Transfer in 3-Hydroxy-3-Methylglutaryl-Coenzyme A Reductase. Biochemistry 2013, 52, 5195–5205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (40).Bensch W; Rodwell VW Purification and Properties of 3-Hydroxy-3-Methylglutaryl Coenzyme A Reductase from Pseudomonas. J. Biol. Chem. 1970, 245, 3755–3762. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (41).Retey J; Stetten E; Coy U; Lynen F A Probable Intermediate in the Enzymic Reduction of 3-Hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl Coenzyme A. Eur. J. Biochem. 1970, 15, 72–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (42).Siegbahn PEM; Himo F The Quantum Chemical Cluster Approach for Modeling Enzyme Reactions. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. Comput. Mol. Sci. 2011, 1, 323–336. [Google Scholar]

- (43).Senn HM; Thiel W QM/MM Methods for Biomolecular Systems. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2009, 48, 1198–1229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (44).Tantillo DJ; Jiangang C; Houk KN Theozymes and Compuzymes: Theoretical Models for Biological Catalysis. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol. 1998, 2, 743–750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (45).Mulholland AJ; Grant GH; Richards WG Computer Modelling of Enzyme Catalysed Reaction Mechanisms. Protein Eng. 1993, 6, 133–147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (46).Wiest O; Houk KN Stabilization of the Transition State of the Chorismate-Prephenate Rearrangement: An Ab Initio Study of Enzyme and Antibody Catalysis. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1995, 117, 11628–11639. [Google Scholar]

- (47).Frisch MJ; Trucks GW; Schlegel HB; Scuseria GE; Robb MA; Cheeseman JR; Scalmani G; Barone V; Petersson GA; Nakatsuji H; et al. Gaussian 16; Gaussian, Inc.: Wallingford, CT, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- (48).Zhao Y; Truhlar DG The M06 Suite of Density Functionals for Main Group Thermochemistry, Thermochemical Kinetics, Noncovalent Interactions, Excited States, and Transition Elements: Two New Functionals and Systematic Testing of Four M06-Class Functionals and 12 Other Function. Theor. Chem. Acc. 2008, 120, 215–241. [Google Scholar]

- (49).Li L; Li C; Zhang Z; Alexov E On the Dielectric “Constant” of Proteins: Smooth Dielectric Function for Macromolecular Modeling and Its Implementation in DelPhi. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 2013, 9, 2126–2136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (50).Bayly CI; Cieplak P; Cornell WD; Kollman PA A Well-Behaved Electrostatic Potential Based Method Using Charge Restraints for Deriving Atomic Charges: The RESP Model. J. Phys. Chem. 1993, 97, 10269–10280. [Google Scholar]

- (51).Wang J; Cieplak P; Kollman PA How Well Does a Restrained Electrostatic Potential (RESP) Model Perform in Calculating Conformational Energies of Organic and Biological Molecules? J. Comput. Chem. 2000, 21, 1049–1074. [Google Scholar]

- (52).Suzuki H How Enzymes Work - from Structure to Function; Pan Standford Publishing: 2015. [Google Scholar]

- (53).Warshel A; Levitt M Theoretical Studies of Enzymic Reactions: Dielectric, Electrostatic and Steric Stabilization of the Carbonium Ion in the Reaction of Lysozyme. J. Mol. Biol. 1976, 103, 227–249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (54).Dapprich S; Komáromi I; Byun KS; Morokuma K; Frisch MJ A New ONIOM Implementation in Gaussian98. Part I. The Calculation of Energies, Gradients, Vibrational Frequencies and Electric Field Derivatives. J. Mol. Struct. 1999, 461–462, 1–21. [Google Scholar]

- (55).Chung LW; Sameera WMC; Ramozzi R; Page AJ; Hatanaka M; Petrova GP; Harris TV; Li X; Ke Z; Liu F; et al. The ONIOM Method and Its Applications. Chem. Rev. 2015, 115, 5678–5796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (56).Kollman PA; Massova I; Reyes C; Kuhn B; Huo S; Chong L; Lee M; Lee T; Duan Y; Wang W; et al. Calculating Structures and Free Energies of Complex Molecules: Combining Molecular Mechanics and Continuum Models. Acc. Chem. Res. 2000, 33, 889–897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (57).Tao P; Schlegel HB A Toolkit to Assist ONIOM Calculations. J. Comput. Chem. 2010, 31, 2363–2369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (58).Calixto AR; Ramos MJ; Fernandes PA Influence of Frozen Residues on the Exploration of the PES of Enzyme Reaction Mechanisms. J. Chem. Theory Comput 2017, 13, 5486–5495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (59).Istvan ES; Deisenhofer J The Structure of the Catalytic Portion of Human HMG-CoA Reductase. Biochim. Biophys. Acta, Mol. Cell Biol. Lipids 2000, 1529, 9–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (60).Oliveira EF; Cerqueira NMFSA; Ramos MJ; Fernandes PA QM/MM Study of the Mechanism of Reduction of 3-Hydroxy-3-Methylglutaryl Coenzyme A Catalyzed by Human HMG-CoA Reductase. Catal. Sci. Technol. 2016, 6, 7172–7185. [Google Scholar]

- (61).Tabernero L; Bochar DA; Rodwell VW; Stauffacher CV Substrate-Induced Closure of the Flap Domain in the Ternary Complex Structures Provides Insights into the Mechanism of Catalysis by 3-Hydroxy-3-Methylglutaryl-CoA Reductase. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 1999, 96, 7167–7171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (62).Durr IF; Rudney H The Reduction of β-Hydroxy-β-Methylglutaryl Coenzyme A to Mevalonic Acid. J. Biol. Chem. 1960, 235, 2572–2578. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (63).Purohit V Elucidating the HMG-CoA Reductase Reaction Mechanism Using PH-Triggered Time-Resolved X-Ray; Purdue University: West Lafeyette, IN, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- (64).Caswell BT; Carvalho CC; Nguyen H; Roy M; Nguyen T; Cantu DC Thioesterase Enzyme Families: Functions, Structures, and Mechanisms. Protein Sci. 2022, 31, 652–676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (65).Chen SL; Fang WH; Himo F Reaction Mechanism of the Binuclear Zinc Enzyme Glyoxalase II - A Theoretical Study. J. Inorg. Biochem. 2009, 103, 274–281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (66).Awodi UR; Ronan JL; Masschelein J; De Los Santos ELC; Challis GL Thioester Reduction and Aldehyde Transamination Are Universal Steps in Actinobacterial Polyketide Alkaloid Biosynthesis. Chem. Sci. 2017, 8, 411–415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (67).Foo JL; Rasouliha BH; Susanto AV; Leong SSJ; Chang MW Engineering an Alcohol-Forming Fatty Acyl-CoA Reductase for Aldehyde and Hydrocarbon Biosynthesis in Saccharomyces Cerevisiae. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2020, 8, 1–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (68).Rowland O; Zheng H; Hepworth SR; Lam P; Jetter R; Kunst L CER4 Encodes an Alcohol-Forming Fatty Acyl-Coenzyme A Reductase Involved in Cuticular Wax Production in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 2006, 142, 866–877. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (69).Domergue F; Vishwanath SJ; Joubes J; Ono J; Lee JA; Bourdon M; Alhattab R; Lowe C; Pascal S; Lessire R; Rowland O Three Arabidopsis Fatty Acyl-Coenzyme A Reductases, FAR1, FAR4, and FAR5, Generate Primary Fatty Alcohols Associated with Suberin Deposition. Plant Physiol. 2010, 153, 1539–1554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (70).Quinn TR; Steussy CN; Haines BE; Lei J; Wang W; Sheong FK; Stauffacher CV; Huang X; Norrby P-O; Helquist P; et al. Microsecond Timescale MD Simulations at the Transition State of Pm HMGR Predict Remote Allosteric Residues. Chem. Sci. 2021, 12, 6413–6418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (71).Quinn TR; Patel HN; Koh KH; Haines BE; Norrby P-O; Helquist P; Wiest O Automated Fitting of Transition State Force Fields for Biomolecular Simulations. PLoS One 2022, 17, e0264960. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.