Summary

Alpha-synuclein (α-Syn) is an important molecule in the pathogenesis of Parkinson’s and Alzheimer’s disease-related dementias such as Lewy body dementia, forming multiple pathological species. In vitro disease models, including human neurons and α-Syn-transfected cells, are instrumental to understand synucleinopathies or test new therapies. Here, we provide a detailed protocol to generate human neurons derived from induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs), and HEK cells, with α-Syn mutations. We also describe multiple assays to determine the various α-Syn forms.

Subject areas: Biotechnology and bioengineering, Molecular Biology, Neuroscience, Stem Cells

Graphical abstract

Highlights

-

•

Methods to generate PD cell models with multiple α-Syn species in vitro

-

•

Protein extraction and media collection from induced neurons and transfected cells

-

•

Guide for analysis of intracellular and extracellular levels of α-Syn via ELISA

-

•

Instructions for investigating major α-Syn species using immunoblotting

Publisher’s note: Undertaking any experimental protocol requires adherence to local institutional guidelines for laboratory safety and ethics.

Alpha-synuclein (α-Syn) is an important molecule in the pathogenesis of Parkinson’s and Alzheimer’s disease-related dementias such as Lewy body dementia, forming multiple pathological species. In vitro disease models, including human neurons and α-Syn-transfected cells, are instrumental to understand synucleinopathies or test new therapies. Here, we provide a detailed protocol to generate human neurons derived from induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs), and HEK cells, with α-Syn mutations. We also describe multiple assays to determine the various α-Syn forms.

Before you begin

The protocols below describe methods to qualitatively and quantitatively investigate different species of α-Synuclein (α-Syn) in human neurons (HN) and transfected HEK293T cells (HEK). Before starting the experiments, researchers should have the appropriate plasmid, iPSC lines, reagents, and equipment to perform each procedure described below. Plasmids or iPSC lines carrying other PD-related mutations can be used as well; however, optimizations are required to ensure a positive outcome of each experiment.

Plasmid DNA preparation

Timing: 2 h (for step 1)

Timing: 1.5 days (for step 2)

-

1.Transformation.

-

a.Thaw out a vial containing ∼20–50 μL of DH5-alpha Competent E. coli cells from −80°C and keep it on ice (at 4°C).

CRITICAL: The competent cells must be stored at −80°C.

CRITICAL: The competent cells must be stored at −80°C. -

b.Gently flick the vial after thawing out on ice and add 1–5 μL containing 50 ng of Synuclein alpha (SNCA) A53T plasmid to the cell mixture.

-

c.Gently flick the tube to ensure a proper mix of cells and DNA. Let the mixture sit on ice for 30 min.

CRITICAL: Vortexing is not advised.

CRITICAL: Vortexing is not advised. -

d.Heat shock the cells by placing the vial at 42°C for 30 s. Immediately transfer it on ice for 5 min.

-

e.Pipette 950 μL of S.O.C. (Super Optimal broth with Catabolite repression) Medium at room temperature (RT) into the mixture.

-

f.Place the vial at 37°C for 60 min. Shake vigorously (∼250 rpm).

-

g.Place Petri dishes with agar at RT or 37°C to warm them up.

-

h.Using a pipette with a sterile tip, transfer 10–50 μL from the vial onto a selection plate with LB agar and spread the mixture using sterile glass beads.Alternatives: Other tools such as cell spreaders can be used as well.

CRITICAL: The amount of plasmid will significantly affect the number of colonies that will grow in the agar plate. A very low volume may not be optimal for significant clone numbers, while a high volume may lead to merge of single clones. Thus, it is important to check the copy number of the plasmid and optimize the amount plated on the plate.

CRITICAL: The amount of plasmid will significantly affect the number of colonies that will grow in the agar plate. A very low volume may not be optimal for significant clone numbers, while a high volume may lead to merge of single clones. Thus, it is important to check the copy number of the plasmid and optimize the amount plated on the plate.-

i.LB Agar should be prepared in a flask (125–500 mL) before starting the experiment.

-

ii.The LB Agar final concentration is 37 g/L. Prepare the amount needed in distilled water.

-

iii.Autoclave at 121°C.

-

iv.Cool down the flask to around 50°C before use. Then transfer the flask to RT before adding the corresponding antibiotic.

CRITICAL: Agar will polymerize if kept for too long at RT the temperature with the temperature dropping below 50°C.Alternatives: If longer time is required for the preparation of the Petri dishes, the flask containing agar can be kept in a water bath at 50°C–55°C.

CRITICAL: Agar will polymerize if kept for too long at RT the temperature with the temperature dropping below 50°C.Alternatives: If longer time is required for the preparation of the Petri dishes, the flask containing agar can be kept in a water bath at 50°C–55°C. -

v.Add the antibiotic to the agar when still warm and mix the content.Note: The antibiotic to be used varies depending on the plasmid employed. In this study for the SNCA A53T plasmid, we used 100 μg/mL Ampicillin.

CRITICAL: Ampicillin is heat-sensitive, so it should be added when the solution reaches 50°C–55°C (when the flask is not too hot).

CRITICAL: Ampicillin is heat-sensitive, so it should be added when the solution reaches 50°C–55°C (when the flask is not too hot). -

vi.Pour gently the agar into the Petri dishes and let them cool down at RT.

-

i.

-

i.Incubate the dishes overnight at 37°C.

-

a.

-

2.Plasmid DNA extraction.

-

a.Inspect Petri dishes after 24 h and pick a single colony using a sterile 10 μL tip.Note: If single colonies are not visible, repeat from step 1. Ensure the good quality of competent cells (i.e. vials stored at −80°C, that have not undergone multiple freeze-thaw cycles) and/or optimize the amount of plasmid DNA been used.

-

b.Prepare a sterile bacterial 15 mL tube with 3 mL of LB broth supplemented with 100 μg/mL of the resistance antibiotic.

-

i.LB broth should be prepared in a bottle (500–1,000 mL) before starting the experiment.

-

ii.The LB final concentration is 25 g/L. Prepare the amount needed in distilled water and autoclave at 121°C. Cool down at RT before use.Note: The unused LB broth needs to be well sealed and can be stored at 4°C for about a month.

-

i.

-

c.Immerge the tip in the LB broth and pipette up and down multiple times.

-

d.Shake the tube at ∼250 rpm at 37°C.

-

e.After 8–10 h inspect the tube and, if turbidity is visually detected, transfer the content to a bigger flask (50–400 mL) adding LB broth supplemented with 100 μg/mL of ampicillin.Alternatives: A more accurate way to measure the amount of growth (determined by turbidity) involves the use of spectrophotometer; however, for this purpose, visual inspection is considered acceptable.Note: The amount of LB broth in the bigger flask depends on the kit used for the plasmid DNA extraction and the amount of plasmid DNA needed for the experiment. In general, we recommend transferring by 1:500–1:1,000 ratio. For this study, using Maxiprep, we used 300 mL as final volume.

CRITICAL: The incubation time varies depending on the copy number of the plasmid and the initial amount of LB broth. If no turbidity is detected, repeat from step a and transfer a larger volume to the bigger flask.

CRITICAL: The incubation time varies depending on the copy number of the plasmid and the initial amount of LB broth. If no turbidity is detected, repeat from step a and transfer a larger volume to the bigger flask. -

f.Shake the flask overnight (around 12–14 h) at ∼250 rpm at 37°C.Note: The flask can be sealed with aluminum foil, cotton or cork plugs.

-

g.Pellet down the cells by centrifugation at ≥ 3,400 × g for 10 min and discard the supernatant.

-

h.Perform plasmid extraction as indicated by the manufacturer’s instructions.Alternatives: ZymoPURE Plasmid Kits Miniprep (#4212), Midiprep (#D4200) and Maxiprep (#D4202) can be used following the manufacturer's instructions (Protocol:_d4202_d4203_zymopure_ii_plasmid_maxiprep.pdf (zymoresearch.com)).

Pause point: The eluted plasmid DNA can be stored at ≤ −20°C.

Pause point: The eluted plasmid DNA can be stored at ≤ −20°C.

-

a.

HEK cells transfection

Timing: 3–4 days

Transfection of HEK293T cells with calcium phosphate method.

Alternatives: Other transfection protocols (i.e., lipofectamine) can be used.1 Each methodology should be optimized for each specific experiment. Different reagents and transfection efficiency are also the factors that should be considered.

-

3.

Measure plasmid concentration using Nanodrop according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Protocol: NanoDrop 2000/2000c Spectrophotometers - User Manual (thermofisher.com)).

CRITICAL: Ensure the sample is good enough to be used in the experiment. In general, for a Maxiprep, a yield ≥ 500 ng/μL and A260/280 ratio between 1.8–2.0 is considered acceptable. If these criteria are not met, repeat the plasmid DNA extraction.

-

4.

Change the appropriate culture vessel with fresh media (DMEM with 10% FBS).

CRITICAL: To ensure an optimal transfection, cell confluency should be around 60%–80%.

-

5.

Verify the correct amount of DNA and other solutions according to the culture vessel used (Table 1).

-

6.For 1 μg of plasmid, prepare the DNA/CaCl2 mix by using one 1.5 mL Eppendorf tube with plasmid and 5 μL 2.5 M CaCl2, completed to 50 μL sterile water.

-

a.Pipette 1 μg of plasmid DNA into a sterile 1.5 mL Eppendorf tube.

-

b.Add 5 μL of 2.5 M CaCl2 to the tube containing the plasmid DNA.

CRITICAL: This adding order allows the CaCl2 to interact directly with the DNA, facilitating the formation of DNA/CaCl2 complexes.

CRITICAL: This adding order allows the CaCl2 to interact directly with the DNA, facilitating the formation of DNA/CaCl2 complexes. -

c.Add sterile water to the tube to bring the total volume to 50 μL.

-

d.Gently mix the contents by pipetting up and down or by flicking the tube to ensure the solution is homogeneous.

-

e.Incubate at RT for 5 min to allow the formation of DNA/CaCl2 complexes.

-

a.

-

7.

Prepare another Eppendorf tube containing 50 μL 2X HBS.

-

8.

Add content from the DNA/CaCl2 mix to the tube with 2X HBS very slowly drop-by-drop. Then mix by bubble-in way. Incubate the transfection mix for 30 min at RT.

CRITICAL: The preparation of the transfection mix should be done carefully to avoid disturbing the integrity of the transfection complex.

-

9.

Take the culture vessel out from the incubator and add the transfection mix dropwise to the medium. Shake gently to evenly distribute the transfection mix.

-

10.

Around 8 h after transfection, replace with fresh media.

Note: The time (8–16 h) depends on different factors, including the type of cells used, the culture vessel, the transfection method, and the reagent concentration. Indeed, some cells are more sensitive to transfection and the surface area-to-volume ratio in different vessels can also affect the timing.

-

11.

48–72 h after transfection, start antibiotic selection by adding the antibiotic to the fresh media.

Note: This step is usually performed to obtain a stable line. For the purpose of this study, we used a transient expression system.

Table 1.

Optimal DNA concentration and other information for transfection using different culture vessels

| Culture vessel | Approx. Surface () | DNA amount (μg) | Media (mL) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 6-well plate | 10 | 3–5 | 2 |

| 12-well plate | 4 | 1–2.5 | 1 |

| 24-well plate | 2 | 0.25–1.25 | 0.5 |

| T25 flask | 25 | 8–10 | 6 |

| T75 flask | 75 | 20–35 | 12 |

| T175 flask | 175 | 60–70 | 24 |

Neuron induction from human iPSCs

Timing: 30–45 days

Please refer to a previous work for the efficient (>90%) generation of glutamatergic neurons.2 A brief description is shown in Figure 1 with minor modifications.

Figure 1.

Differentiation of human neurons (HN) from iPSCs

(A) The combination of lentiviral vectors leads to tetracycline-inducible expression of Ngn2 driven by a tetO promoter. Overexpression of Ngn2 promotes the generation of glutamatergic cortical-like neurons resembling neurons in cortical layers 2/3.

(B) Glutamatergic neurons derived from iPSCs are rapidly generated due to overexpression of the single transcription factor Ngn2. A homogeneous population is ensured using puromycin selection and addition of AraC to inhibit the proliferation of non-neuronal cells.

(C) Mature cells express typical neuronal markers, both nuclear (NeuN) and cytoplasmic (MAP2) after 4 weeks of induction. Scale bar: 50 μm (Confocal) and 100 μm (Bright field).

iPSCs (healthy line and lines carrying SNCA A53T/TRPL mutation) are seeded in a Matrigel pre-coated 12-well plate at a density of 50,000 with lentiviral vectors for doxycycline-dependent overexpression of Neurogenin2 (Ngn2).

Note: The working solution of Matrigel (Corning, Cat#356234) is prepared by diluting 1 mL of the Matrigel matrix into 49 mL of cold DMEM/F12 (Gibco, Cat#11320033). Mix well. For a 6-well plate we recommend adding 1 mL of the working solution per well; while for a 12-well plate 0.5 mL per well. The wells must be coated in the hood and the plate can be gently shaken to ensure a homogeneous distribution of Matrigel. The plate can then be returned at 37°C, 5% CO2 and used after 2 h.

CRITICAL: The stock vial of Matrigel should be always kept on ice to avoid polymerization. The working solution can be prepared after Matrigel is thawed out and aliquoted overnight on ice at 4°C. Also, all plastic consumables that come into contact with Matrigel need to be pre-cold.

After 24 h differentiation medium (DM) containing doxycycline can be added to the wells. Puromycin (5 μg/mL) selection follows for 48 h. During differentiation, media is changed to maturation medium (MM) supplemented with cytosine arabinoside (AraC) (50 nM) and puromycin (2 μg/mL) to inhibit the proliferation of remaining stem cells/non-neuronal cells. Media can be half-changed every 2–3 days until the day of experiment. For media composition, please see the materials and equipment section.

Note: These modifications were applied to improve the purity and the confluency of the neurons. The conditions of this protocol vary depending on different cell lines (i.e. iPSCs carrying other PD-related mutations).

Note: Loss of dopaminergic (DA) neurons is a primary hallmark of PD3; however, cortical and subcortical glutamatergic signals have been also shown to play an important role in PD symptomatology.4,5,6 The differentiation method employed in this study, able to rapidly generate mature glutamatergic neurons that express multiple α-Synuclein forms, has been extensively used as an in vitro platform to study synucleinopathies and test therapeutics targeted at clearing synuclein from cells.7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14

Key resources table

| REAGENT or RESOURCE | SOURCE | IDENTIFIER |

|---|---|---|

| Antibodies | ||

| NeuN (1:1,000) | Abcam | RRID: AB_10711153 Cat#ab104224 |

| MAP2 (1:2,000) | Abcam | RRID: AB_2138153 Cat#ab5392 |

| MJFR1 (1:1,000) | Abcam | RRID: AB_2537217 Cat#ab138501 |

| LB509 (1:500) | Abcam | RRID: AB_727020 Cat#ab27766 |

| pS129 (1:500) | Abcam | RRID: AB_869973 Cat#ab51253 |

| IRDye 680RD Goat anti-rabbit (1:3,000) | LI-COR Inc. | Cat#926-68071 |

| IRDye 680RD Goat anti-mouse (1:3,000) | LI-COR Inc. | Cat#926-68070 |

| IRDye 800CW Goat anti-rabbit (1:3,000) | LI-COR Inc. | Cat#926-32211 |

| IRDye 800CW Goat anti-mouse (1:3,000) | LI-COR Inc. | Cat#926-32210 |

| Bacterial and virus strains | ||

| 5-alpha Competent E. coli | New England Biolabs | Cat#C2987H |

| pTet-O-Ngn2-puro (Lentivirus) | VectorBuilder | Cat# LVL(pLV201222-1003ssm)-C |

| FUW-M2rtTA (Lentivirus) | VectorBuilder | Cat# LVL(pLV201222-1004wmx)-C |

| Chemicals, peptides, and recombinant proteins | ||

| DMEM | Invitrogen | Cat#11965-092 |

| Fetal bovine serum | Genesee Scientific Corporation | Cat#25514H |

| LB Broth | Apex Bioresearch Products | Cat#25514H |

| Luria-Bertani Agar | Bioworld | Cat#306200421 |

| Ampicillin | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat#A5354 |

| mTeSR plus | STEMCELL Technologies | Cat#100-0276 |

| DMEM/F12 | Gibco | Cat#11320033 |

| N2 supplement | Gibco | Cat#17502048 |

| MEM NEAA | Gibco | Cat#11140050 |

| Human BDNF | PeproTech | Cat#450-02 |

| Human NT-3 | PeproTech | Cat#450-03 |

| Mouse laminin | Gibco | Cat#23017015 |

| Doxycycline | Clontech Labs | Cat#631311 |

| Accutase | STEMCELL Technologies | Cat#07922 |

| Thiazovivin | Selleckchem | Cat#S1459 |

| Neurobasal plus | Gibco | Cat#A3582901 |

| B27 supplement | Gibco | Cat#17504044 |

| GlutaMAX | Gibco | Cat#35050061 |

| Puromycin | InvivoGen | Cat#ant-pr-1 |

| Cytosine β-D-arabinofuranoside (AraC) | Sigma | Cat#C1768 |

| RIPA lysis and extraction buffer | Thermo Scientific | Cat#89900 |

| Halt Protease Inhibitor Cocktail (100X) | Thermo Scientific | Cat#78429 |

| 2-Mercaptoethanol | Sigma | Cat#516732 |

| 4x Laemmli sample buffer | Bio-Rad | Cat#1610747 |

| NuPAGE MES SDS Running Buffer | Invitrogen | Cat#NP0002 |

| Glutaraldehyde solution | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat#G5882 |

| 10% Tween 20 solution | Bio-Rad | Cat#1610781 |

| Dry milk powder | Research Products International | Cat#M17200 |

| Critical commercial assays | ||

| Pierce BCA Protein Assay Kits | Thermo Scientific | Cat#23225 |

| ZymoPURE II Plasmid Midiprep Kit | Zymo Research | Cat#D4200 |

| LEGEND MAX Human α-Synuclein (Colorimetric) ELISA Kit | BioLegend | Cat#448607 |

| Experimental models: cell lines | ||

| HEK293T | ATCC | Cat# CRL 1573 |

| SNCA_A53T (iPSCs) | Dr. Rudolf Jaenisch | Soldner et al., 201315 |

| SNCA_Triplication (iPSCs) | NINDS | Cat# ND34391 |

| 2135 (healthy/CTRL iPSCs line) | Dr. Joseph Mazzulli | Mazzulli et al.16 |

| Recombinant DNA | ||

| pcDNA3.1 SNCA_A53T | Dr. Joseph Mazzulli | Mazzulli et al.17 |

| Software and algorithms | ||

| Graphpad Prism 10.2.0 | GraphPad Software Inc., San Diego, USA | https://www.graphpad.com/updates/prism-10-2-0-release-notes |

| ImageJ | https://github.com/imagej/ImageJ | https://imagej.net/ij/ |

| Microsoft Excel | Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, USA | https://www.microsoft.com/en-us/microsoft-365/excel |

| Other | ||

| Midi Gel Tank | Invitrogen | Cat#A25977 |

| NuPAGE 4%–12%, Bis-Tris gels | Invitrogen | Cat#NP0336PK2 |

| [PM2500] ExcelBand 3-color regular range protein marker (9–180 kDa) | Smobio | Cat#PM2500 |

| iBlot 2 Dry blotting system | Invitrogen | Cat#IB21001 |

| SPECTRAmax PLUS microplate spectrophotometer | Molecular Devices | Cat#0112-0056 |

| LICOR CLx | LI-COR Inc. | https://www.licor.com/bio/odyssey-clx/ |

Materials and equipment

10X PBS, pH 7.4–7.6

| Reagent | Final concentration | Amount |

|---|---|---|

| NaCl | 1370 mM | 80 g |

| KCl | 27 mM | 2 g |

| Na2HPO4 | 100 mM | 17.8 g |

| KH2PO4 | 18 mM | 2.4 g |

| ddH2O | N/A | Up to 1,000 mL after salts are dissolved |

| Total | N/A | 1,000 mL |

Store at RT for short-term and 4°C for long-term (up to 1 month). Autoclave for cell culture-related uses.

10X TBS, pH 7.4–7.6

| Reagent | Final concentration | Amount |

|---|---|---|

| Tris base | 200 mM | 24 g |

| NaCl | 1500 mM | 88 g |

| ddH2O | N/A | Up to 1,000 mL after salts are dissolved |

| Total | N/A | 1,000 mL |

Store at RT for short-term and 4°C for long-term (up to 1 month).

5% Milk PBST/TBST, pH 7.4–7.6

| Reagent | Final concentration | Amount |

|---|---|---|

| 10X PBST/TBST | 1X | 50 mL |

| 10% Tween 20 Solution | 0.1X | 5 mL |

| Dry milk powder | N/A | 25 g |

| ddH2O | N/A | 445 mL |

| Total | N/A | 500 mL |

Store at 4°C for 2 weeks.

2.5 M CaCl2, pH 7.4–7.6

| Reagent | Final concentration | Amount |

|---|---|---|

| CaCl2·2H2O | 2.5M | 36.75 g |

| ddH2O | N/A | 100 mL |

| Total | N/A | 100 mL |

Filter-sterilize, aliquot and store at −20°C.

2X HBS, pH 7.0

| Reagent | Final concentration | Amount |

|---|---|---|

| NaCl | 270 mM | 4 g |

| KCl | 10 mM | 0.18 g |

| Na2HPO4 | 1.5 mM | 0.05 g |

| Dextrose | 10 mM | 0.5 g |

| HEPES | 40 mM | 2.5 g |

| ddH2O | N/A | 250 mL |

| Total | N/A | 250 mL |

Filter-sterilize, aliquot and store at −20°C.

Complete RIPA buffer, pH 7.4–7.6

| Reagent | Final concentration | Amount |

|---|---|---|

| 1X RIPA | 1X | 9.9 mL |

| Halt Protease Inhibitor Cocktail (100X) | 1X | 100 μL |

| Total | N/A | 10 mL |

Make fresh buffer before use. Store at 4°C for short-term.

Differentiation medium (DM), pH 7.4–7.6

| Reagent | Final concentration | Amount |

|---|---|---|

| DMEM/F12 | N/A | 488.4 mL |

| N2 supplement | 1X | 5 mL |

| NEAA MEM | 1X | 5 mL |

| BDNF | 10 ng/mL | 500 μL (from 1000X) |

| NT3 | 10 ng/mL | 500 μL (from 1000X) |

| Laminin | 0.2 μg/mL | 100 μL (from 5000X) |

| Doxycycline | 2 μg/mL | 500 μL (from 1000X) |

| Total | N/A | 500 mL |

Store at 4°C.

Maturation medium (MM), pH 7.4–7.6

| Reagent | Final concentration | Amount |

|---|---|---|

| Neurobasal plus | N/A | 483.4 mL |

| B27 supplement | 1X | 10 mL |

| Glutamax | 1X | 5 mL |

| BDNF | 10 ng/mL | 500 μL (from 1000X) |

| NT3 | 10 ng/mL | 500 μL (from 1000X) |

| Laminin | 0.2 μg/mL | 100 μL (from 6000X) |

| Doxycycline | 2 μg/mL | 500 μL (from 1000X) |

| Total | N/A | 500 mL |

Store at 4°C.

Step-by-step method details

Samples collection from harvested cells

Timing: 1–2 h

-

1.

Label and arrange 1.5 mL Eppendorf tubes on ice for both lysates and media collection.

-

2.

Add Halt Protease and Phosphatase Inhibitor Cocktail to the tubes that will be used to collect the media (1X or 10 μL / 1 mL of media from 100X).

-

3.

Prepare 1X RIPA assuming the right amount of volume to the well/flask/dish.

Note: For a well of a 12-well plate containing around 50,000 neurons, 150–200 μL/well of 1X RIPA is an appropriate volume and can be added directly to the well after one wash with 1X PBS. For a T25 flask containing around 2 million HEK cells, first detach the cells using 0.05% trypsin-EDTA, briefly spin down in a 15 mL tube and wash the pellet with 1X PBS. Spin down again and add 500–600 μL of 1X RIPA. A larger amount of 1X RIPA can be prepared and stored at −20°C.

CRITICAL: Inspect the cells under the microscope before collection. Verify the condition of the culture and if the number of neurons is similar in all the wells as this may affect the results of the experiment. See problem 1 in troubleshooting section.

-

4.

Take the plate out of the incubator and place it on a tank filled with ice.

-

5.

Transfer the media of each well into the tubes with protease and phosphatase inhibitor cocktail.

-

6.

Gently wash the cells by adding 1X pre-cold PBS to the culture vessel/tube.

Note: For neurons in a well of a 12-well plate, 500 μL of 1X PBS is the recommended volume for washing. HEK cells are washed before 1X RIPA is added (step 3).

CRITICAL: This step needs to be taken quickly to prevent the cells from drying out and carefully avoid dislodging the cells.

-

7.Aspirate the PBS and add 1X pre-cold RIPA to wells.

-

a.Shake the plate by hand to ensure homogeneous distribution of the extraction buffer.

-

b.Keep it on ice for 30–45 min. See problem 2 in troubleshooting section.

-

a.

-

8.Spin down the tubes containing the media at 4°C for 5 min at 3,000–5,000 rpm.

-

a.Collect the supernatant in a new tube and discard the cell debris. Store at −20°C.

-

a.

-

9.Collect the cells into fresh 1.5 mL tubes and spin down at 4°C for 20 min at 14,000–15,000 rpm.

-

a.Collect the supernatant in a new tube and discard the cell debris. Store at −20°C.

-

a.

Note: The extraction buffer can be pipetted up and down in the well until all cells are collected. Be careful not to introduce any bubbles.

Alternatives: Cell scrapers can be used as well.

Determining protein concentration

Using the Pierce BCA Protein Assay Kit (Thermo Scientific, Cat#23225), determine protein concentration as it follows.

-

10.

Keep the lysates on ice while working with the kit.

-

11.

In the first lane of a 96-well plate, prepare the mix of 8 Standards (S1–8) using diluted albumin (BSA) and extraction buffer (1X RIPA). Gently pipette up and down for each well. Transfer 10 μL into two wells. See below the table for dilutions (Table 2).

-

12.

Pipette up and down each sample to mix well before transferring 10 μL into two wells.

-

13.

Prepare by mixing 50 parts of BCA reagent A with 1 part of BCA reagent B (working solution).

Note: It is advised to prepare a larger volume of working solution, but keep in mind that it cannot be stored and it should be prepared fresh for each experiment.

-

14.

Add 190 μL of the working solution to each well containing standards and unknown samples. The solution will start to turn purple.

-

15.

Wrap the 96-well plate with aluminum foil and incubate the plate at 37°C for 30 min.

-

16.

Measure the absorbance using the appropriate instrument set at 562 nm. See problem 3 in troubleshooting section.

-

17.Determine protein concentrations by using curve-plotting software.

-

a.Create a standard curve for the target protein by plotting the mean absorbance (optical density, OD) on the y-axis and protein concentration (μg/mL) on the x-axis.

-

b.Draw a best-fit curve through the points in the graph to generate the equation for calculating the concentration (x) from a given absorbance (y) in the range of the standard curve.

-

c.Calculate the sample concentrations based on the ODs obtained and equation obtained in the previous step.

-

a.

Table 2.

Dilutions required for BCA

| S1 | S2 | S3 | S4 | S5 | S6 | S7 | S8 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| μg/mL | 2,000 | 1,500 | 1,000 | 750 | 500 | 250 | 125 | 0 |

| Volume BSA (μL) | 50 | 37.5 | 25 | 18.8 | 12.5 | 6 | 3.1 | – |

| Volume Extraction buffer (μL) | – | 12.5 | 25 | 31.2 | 37.5 | 44 | 46.9 | 50 |

ELISA—Dilution tests and total α-synuclein determination

Timing: 5–6 h

This step ensures that an optimal amount of protein/volume of media is established before each experiment. The kit is stored at 4°C (except for the Stop Solution) and, before each use, every reagent should be brought at RT. Please refer to the manufacturer’s protocol (Protocol: 448607_Manual_R01_Hu_aSynuclein_colorimetric_LEGEND_MAX.pdf (d1spbj2x7qk4bg.cloudfront.net)).

Alternatives: Similar ELISA kits targeting total human alpha-synuclein can be used (i.e. Abcam #ab260052 and Invitrogen #KHB0061) but protocols vary from kit to kit. Please refer to the manufacturer’s instructions and perform optimizations if required.

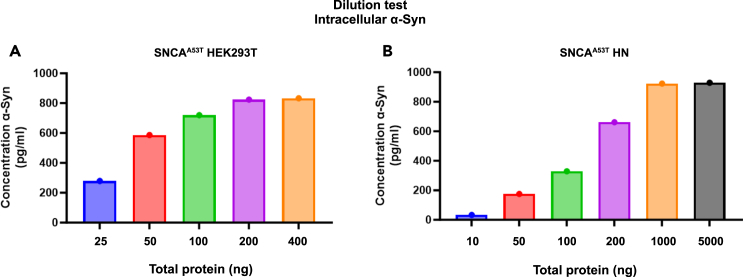

Before starting each experiment, dilutions tests should be performed for both media and lysates. An example of the lysates’ dilution test is shown in Figure 2.

-

18.

Prepare 1X Wash Buffer and 1X Diluent Buffer from stocks using deionized water.

-

19.

Reconstitute the lyophilized Human α-Synuclein Standard by adding 1X Diluent Buffer to make the 75 ng/mL standard stock solution. Let it sit at RT for 15–20 min, then briefly vortex to mix completely.

CRITICAL: The volume to be added varies from lot to lot, and so it is important to check the concentration of the lyophilized Human α-Synuclein Standard on the manufacturer’s website. DO NOT MIX REAGENTS FROM DIFFERENT LOTS. The unused standard stock can be aliquoted into polypropylene tubes and stored at −80°C for up to one month. Do not repeat freeze-thaw cycles.

-

20.Take 8 Eppendorf tubes and place them on a rack at RT.

-

a.Add 991 μL of 1X Diluent Buffer in one tube and name it S1 (Standard 1).

-

b.Add 200 μL of 1X Diluent Buffer in the other tubes.

-

c.Transfer 8.7 μL from the standard stock solution to the S1 tube, mix well. The final concentration of S1 is 650 pg/mL.

-

d.Prepare the standards by transferring 200 μL from one standard to the next (S1 to S7, six two-fold dilutions), mixing well between each dilution as shown in Figure 3.

-

a.

Note: There is a slight variation in terms of OD readings between different lots. A top standard with ODs between 2 to 3 can be considered acceptable. Also, not all standards need to be used when plotting the curve, in fact it is important to consider the linear range of the curve as well as the sensitivity of the assay. This applies to ODs of the samples as well, values above and below the linear range should not be used for analysis.

-

21.

Take the plate out from the foil pouch. Remove the excess strips by pressing up from underneath each strip and put them back in the pouch.

-

22.Wash the plate 4 times with 400 μL of 1X Wash Buffer per well.

-

a.Wait for 30 s between each wash.

-

b.Firmly reverse the plate in a tank or sink to remove the buffer.

-

c.Tap the plate upside down on absorbent paper.

-

a.

-

23.

Add 50 μL of Reagent Diluent (1X) to each well. Then add 50 μL of standards or samples to the appropriate wells.

Note: For this study, the optimal amount of total protein loaded for HEK293T cells can be varies from 25 ng to 100 ng/well. For both human iPSCs-derived neurons we loaded 50 ng/well. Regarding the media, since BCA cannot be performed, the optimal amount was determined similarly using different volumes. The working volume was selected according to the optical density readings (data not shown). 5 μL was loaded for each condition, and the volume of 1X Diluent buffer was increased to 95 μL (to keep the same volume with the standards).

-

24.

Seal the plate with a Plate Sealer provided in the kit and incubate the plate for 2 h at RT while shaking on an orbital shaker at 60–100 rpm.

-

25.

Discard the contents of the plate, then wash as in step 22.

-

26.

Add 100 μL of Human α-Synuclein Detection Antibody solution to each well, seal the plate and incubate at RT for 1 h while shaking.

-

27.

Discard the contents of the plate, then wash as in step 22.

-

28.

Add 100 μL of Avidin HRP solution to each well, seal the plate and incubate at RT for 30 min while shaking.

-

29.

Discard the contents of the plate, then wash as in step 22.

Note: For this step, wait 30 s to 1 min between washes. An additional wash (for a total of 5 washes) is also recommended.

-

30.

Add 100 μL of Substrate Solution F to each well and incubate for 20 min keeping the plate in the dark. Sealing the plate is not required. The wells will start turning blue. See problem 4 in troubleshooting section.

-

31.

Stop the reaction by adding 100 μL of Stop Solution to each well. The solution’s color will turn yellow.

-

32.

Read absorbance at 450 nm within 30 min. An example is shown in Figure 4.

Note: If the instrument has a filter capable of reading at 560–570 nm, these readings can be subtracted to the 450 nm readings for correction.

Figure 2.

Lysate dilution, for optimizing the assay and determining the amount to load for the experiment

The optimal protein concentration should be determined by performing several dilutions before each experiment.

(A) For HEK293T A53T 25 ng was the best dilution, based on the ODs of the samples compared to the standards.

(B) For neurons, the optimal range was between 50–100 ng/well. Please refer to the expected outcomes section.

Figure 3.

Preparation of the standards for the α-Syn ELISA

The preparation of the standards is a critical step to ensure accuracy of the assay. The reconstitution of the stock solution varies from lot to lot, refer to the Lot-Specific Certificate of Analysis. Prepare 1000 μL of the 650 pg/mL standard 1 (S1) by adding 8.7 μL of the stock solution into 991 μL Reagent Diluent (1X). Six two-fold dilutions should be performed as indicated in the Figure. 1X Reagent Diluent serves as the zero standard.

Figure 4.

Example results of α-Syn ELISA in HN and HEK cells

The optimal protein concentration for HN was determined previously by performing several dilutions (Figure 1).

(A) For both HN A53T and TRPL we used 50 ng/well and the ODs were in the linear range thus providing reliable data.

(B) Conditioned media can represent a challenge since it is not possible to determine an exact concentration. As for medium, different dilutions were performed to identify the best amount (data not shown). Values are expressed as mean ± SEM (n = 3 biological replicates).

Immunoblotting—Sample preparation

Timing: 1–2 h

-

33.

Prepare a sample buffer master mix (BME/Laemmli) using 900 μL of 4X Laemmli and 100 μL of 2-betamercaptoethanol.

CRITICAL: This master mix should be prepared fresh every time is needed, since 2-mercaptoethanol is highly volatile.

-

34.According to the different forms of synuclein (see below), dilute the required sample volume with extraction buffer.

-

a.Mix sample with BME/Laemmli by a 3:1 ratio.

-

b.Prepare all samples in 1.5 mL Eppendorf Snap-Cap Microcentrifuge Safe-Lock Tubes.

-

a.

Note: For the detection of oligomers, the samples should be prepared for two simultaneous runs as described later in the text.

CRITICAL: Snap-caps are optimal for this procedure as the regular Eppendorf tubes may open during the boiling phase.

-

35.

Boil the samples at 96°C for 8 min. Then let them cool down to RT.

-

36.

Mix well and spin down the samples.

-

37.

Prepare Invitrogen Mini or Midi Gel Tank and pour 1X NuPAGE MES SDS Running Buffer.

Note: The running buffer should be prepared fresh; however, the Buffer can be stored at 4°C for one week.

-

38.

Take out precast NuPAGE 4%–12%, Bis-Tris Gels from the plastic container, remove the white tape at the bottom of the cast, and gently remove the comb.

Note: It is advised to remove gel debris inside the wells by pipetting the Running Buffer inside the wells using 1000 μL pipette.

-

39.

Add the protein marker/ladder, which can be used to identify the protein of interest and housekeeping protein.

Note: The marker should be selected depending on the protein of interest. For α-Synuclein markers covering 10–200 kDa are advised.

-

40.

Mix the samples well, without introducing bubbles, and load them using long gel tips round sterile 200 μL.

-

41.

Connect the tank to the power supply and run for 2 h (midi gel) or 1.5 h (mini gel) at 60 V for 15 min, then 100 V for the remaining time. Use constant voltage (CV) and max ampere (400 mA). See problem 5 in troubleshooting section.

-

42.

Once the marker is clearly visible, and the proteins have reached the bottom of the gel, transfer the precast gel to a tank filled with distilled water or running buffer.

-

43.

Carefully open the cassette using a gel knife, remove unnecessary parts of the gel or loose ends at the bottom and top, then carefully detach the gel using a gel remover.

Note: It is advised to do so in a tank with distilled water/running buffer. The best way to handle the cassette is to open the 4 corners first outside the tank and then completely open it in solution. This ensures that the gel would not break. Removing the gel can also be challenging, especially for midi gels which are thinner and more fragile. With the cassette completely immersed in the tank, insert the gel remover on a side of the gel (where no marker or samples are present). Then gently slide the remover through the whole gel. For the transfer, the gel can be taken by the extremities and gently put on the stack.

-

44.

Using iBlot 2 Dry Blotting System, transfer the gel using mini or midi transfer stacks. See problem 6 in troubleshooting section.

Note: Longer time allows for the transfer of big proteins (>60 kDa). The type of membrane also depends on the protein of interest. Polyvinylidene fluoride (PVDF) is preferred for non-abundant proteins (i.e., some phosphorylated proteins), small (<15 kDa) and big (>60 kDa) proteins.

Immunoblotting—Detection of multiple forms of α-Synuclein

Timing: 2 days

Although challenging, the detection of multiple species of α-Synuclein is essential for monitoring disease progression and investigating synucleinopathies.18,19,20 Among the different approaches, crosslinking is one of the most commonly employed methods in the field. However, the information on crosslinking is scattered, with authors using various chemicals and conditions.21,22,23 Below, we provide step-by-step instructions for investigating the major synuclein species using immunoblotting.

For the detection of the intracellular monomeric α-Synuclein, the recombinant antibody MJFR1 can be used. 10–15 μg of total protein is sufficient to visualize monomeric α-Syn.

-

45.

From previous step, transfer gel to nitrocellulose (NC) membrane at 23V for 4–5 min.

-

46.

Quickly transfer the membrane to a dark box containing Blocking Solution (5% Milk in 1X PBS-0.1% Tween). Shake membrane at low speed (40–60 rpm) for 1 h at RT.

Note: A transparent box can also be used in this step; however, it should be wrapped with aluminum foil or substituted with a dark box during the secondary antibody incubation.

-

47.

Dilute primary antibodies in Blocking Solution (1:500–1,000) and keep the box on orbital shaker at 4°C overnight.

Note: The antibody dilutions can vary; we observed a good signal with 1:1,000 of MJFR1.

-

48.

The following day, collect the solution containing the primary antibodies in a falcon tube and store at −20°C.

-

49.

Wash with 1X PBS-0.1% Tween 3 times for 10 min each.

Note: Milk with primary antibodies can be stored at −20°C and reused up to 4/5 times for the detection of abundant proteins. Alternatively, 0.02%–0.05% Sodium Azide can be added, and the milk stored at 4°C. We observed that for phosphorylated forms, recycled milk drastically impacts the detection of the protein of interest.

-

50.

Dilute secondary antibodies in Blocking Solution (1:2,000–5,000), apply to well-washed membrane and keep the box on orbital shaker for 1–2 h at RT.

Note: For the protein of interest, the secondary antibodies can be diluted 1:2,000/3,000; for the housekeeping protein higher dilutions can be used.

-

51.

Wash with 1X PBS-0.1% Tween 3 times for 10 min each.

-

52.

Visualize the blot using the appropriate imaging system (Figure 5A).

Figure 5.

Detection of multiple α-Syn species via immunoblotting

(A and B) Monomeric α-Syn and pS129 α-Syn (17 kDa) can be detected in both transfected HEK293T cells and HN lines.

(C) Oligomeric α-Syn species can be clearly detected in aged iPSCs-derived neurons carrying PD mutations but not in healthy neurons and HEK293T. The forms detected in HN lines include dimers (34 kDa) and high molecular weight forms (100–180 kDa). Nonspecific bands (ns), as an effect of the transfer conditions and crosslinking, can be observed in the PVDF membranes. 4 wk: 4-week-old HNs; 6 wk: 6-week-old HNs.

The recombinant phosphor-Serine 129 (pS129) antibody can be used to specifically detect alpha synuclein phosphorylated on Ser129. 20–30 μg of total protein is sufficient to visualize monomeric pS129.

-

53.

From step 46, transfer gel to PVDF membrane at 15V for 7 min.

-

54.

Quickly transfer the membrane to a dark box containing 1% Glutaraldehyde (prepared in distilled water or 1X PBS). Shake membrane at low speed (40–60 rpm) for 1 h at RT.

-

55.

Wash with 1X TBS-0.1% Tween 1 time for 2 min. Add Blocking Solution (5% Milk in 1X PBS-0.1% Tween). Shake membrane at low speed (40–60 rpm) for 1 h at RT.

Note: TBS is recommended when working with phosphoproteins as the antibody raised against the phosphorylated protein may bind to the phospho groups present in the buffer rather than to the phospho antigen itself.

Note: If Blocking Solution is added directly after 1% Glutaraldehyde incubation, the solution will turn brown. It is advised to wash with 1X TBS for 2 min before the primary antibody incubation.

-

56.

Dilute primary antibodies in Blocking Solution (1:250–500) and keep the box on orbital shaker at 4°C overnight.

-

57.

The following day, collect the solution containing the primary antibodies in a falcon tube and store at −20°C. Wash with 1X TBS-0.1% Tween 3 times for 10 min each.

-

58.

Dilute secondary antibodies in Blocking Solution (1:2,000–5,000) and keep the box on orbital shaker for 1–2 h at RT.

-

59.

Wash with 1X TBS-0.1% Tween 3 times for 10 min each.

Note: Additional washes may be required to reducing the background signal, especially when using PVDF membranes. An additional wash in 1X TBS is advised as well.

-

60.

Visualize the blot using the appropriate imaging system (Figure 5B). See problem 7 in troubleshooting section.

For the detection of the intracellular oligomers of α-Synuclein, the monoclonal antibody LB509 can be used. 25–30 μg of total protein is sufficient to visualize multimers. Aged neurons (6 wk) are more likely to exhibit elevated levels of α-Syn oligomeric species.

Note: Due to the nature of this protocol, for the detection of oligomers it is advised to run two gels simultaneously using the same samples. One can be processed separately to detect housekeeping proteins and the other can undergo the following steps.

-

61.

From step 46, transfer gel to PVDF membrane using the following procedure (iBlot system): 20 V for 1 min, 23 V for 4 min, and 25 V for 2 min.

-

62.

Quickly transfer the membrane to a dark box containing 1% glutaraldehyde. Shake membrane at low speed (40–60 rpm) for 1 h at RT.

-

63.

Wash with 1X PBS-0.1% Tween 1 time for 2 min. Add Blocking Solution (5% Milk in 1X PBS-0.1% Tween). Shake membrane at low speed (40–60 rpm) for 1 h at RT.

-

64.

Dilute primary antibody (LB509 only) in Blocking Solution (1:250–500) and keep the box on orbital shaker at 4°C overnight.

-

65.

The following day, collect the solution containing the primary antibodies in a falcon tube and store at −20°C. Wash with 1X PBS-0.1% Tween 3 times for 10 min each.

-

66.

Dilute secondary antibodies in Blocking Solution (1:3,000–5,000) and keep the box on orbital shaker for 1–2 h at RT.

-

67.

Wash with 1X PBS-0.1% Tween 3 times for 10 min each.

-

68.

Visualize the blot using the appropriate imaging system.

-

69.

Re-incubate the blot in primary antibody (housekeeping protein) in Blocking Solution (1:3,000–5,000) and keep the box on orbital shaker at RT for 2 h.

Note: Using this type of transfer and crosslinking, housekeeping proteins < 40–50 kDa may not be detected in the same blot (i.e. GAPDH or beta-actin). Proteins with higher molecular weight like TUBB3 can be used instead.

-

70.

Collect the milk containing the primary antibody in a falcon tube and store at −20°C. Wash with 1X PBS-0.1% Tween 3 times for 10 min each.

-

71.

Dilute secondary antibody in Blocking Solution (1:3,000–5,000) and keep the box on orbital shaker for 1–2 h at RT.

-

72.

Wash with 1X PBS-0.1% Tween 3 times for 10 min each.

-

73.

Visualize the blot (Figure 5C). See problem 8 in troubleshooting section.

Alternatives: Instead of re-incubating the membrane, two runs can be performed simultaneously using the same samples and conditions. One can be used for LB509 detection and the other for housekeeping proteins. For this experiment we used these conditions.

Note: If the housekeeping protein needs to be detected in the same blot, users should be aware that this type of protocol does not allow for the detection of housekeeping proteins <40–50 kDa (i.e. GAPDH or actin). Alternatively, higher molecular weight markers as TUBB3/TUJ1 can be used (Figure 6).

Figure 6.

Alternative method for the detection of housekeeping proteins via oligomers α-Syn immunoblotting

After imaging the blot for LB509 (α-Syn multimers), this can be re-incubated in 5% PBST milk containing the primary antibody of the housekeeping protein. The long transfer time and crosslinking may hinder the detection of low-medium housekeeping proteins (10–40 kDa). 4-week-old HNs.

Expected outcomes

The present protocols have been validated using multiple cell types, including HEK293T and iPSCs-derived neurons. The efficiency of the protocols mainly relies on procedural optimizations and quality of the cells. This includes robust cell differentiation, right amount used for ELISA/Immunoblot, low passage cells, the number and quality of the cells.

ELISA

For the ELISA assay, multiple dilutions are required before starting each experiment to determine the optimal concentration. Tables 3, 4, 5, and 6 depict the ODs of standards and samples loaded at different concentrations (Figure 2). “OD1” and “OD2” refer to technical replicates, while the “Rep” refers to biological replicates.

Table 3.

ODs corresponding to standards for HEK-A53T samples

| Standards (pg/mL) | OD 1 | OD 2 | OD mean |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 0.078 | 0.081 | 0.080 |

| 10.2 | 0.119 | 0.123 | 0.121 |

| 20.3 | 0.168 | 0.184 | 0.176 |

| 40.6 | 0.273 | 0.291 | 0.282 |

| 81.3 | 0.522 | 0.598 | 0.560 |

| 162.5 | 1.159 | 1.171 | 1.165 |

| 325 | 1.760 | 2.060 | 1.910 |

| 650 | 2.926 | 2.997 | 2.962 |

Table 4.

ODs corresponding to different amounts of HEK-A53T lysate protein

| Samples | OD 1 | OD 2 | OD mean | Conc. (pg/mL) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HEK-A53T - 25 ng | 1.718 | 1.182 | 1.450 | 278.554 |

| HEK-A53T - 50 ng | 2.835 | 2.893 | 2.864 | 585.957 |

| HEK-A53T - 100 ng | 3.451 | 3.510 | 3.481 | 719.978 |

| HEK-A53T - 200 ng | 3.912 | 4.000 | 3.956 | 823.348 |

| HEK-A53T - 400 ng | 4.000 | 4.000 | 4.000 | 832.913 |

Table 5.

ODs corresponding to standards for HN-A53T samples

| Standards (pg/mL) | OD 1 | OD 2 | OD mean |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 0.079 | 0.078 | 0.079 |

| 10.2 | 0.098 | 0.153 | 0.126 |

| 20.3 | 0.148 | 0.150 | 0.149 |

| 40.6 | 0.270 | 0.251 | 0.261 |

| 81.3 | 0.431 | 0.433 | 0.432 |

| 162.5 | 0.743 | 0.856 | 0.800 |

| 325 | 1.556 | 1.741 | 1.649 |

| 650 | 2.685 | 2.861 | 2.773 |

Table 6.

ODs corresponding to different amounts of HN-A53T lysate protein

| Samples | OD 1 | OD 2 | OD mean | Conc. (pg/mL) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HN A53T - 5 μg | 4.000 | 4.000 | 4.000 | 928.786 |

| HN A53T - 1 μg | 3.976 | 3.978 | 3.977 | 923.310 |

| HN A53T - 200 ng | 2.874 | 2.878 | 2.876 | 661.167 |

| HN A53T - 100 ng | 1.439 | 1.523 | 1.481 | 329.024 |

| HN A53T - 50 ng | 0.897 | 0.775 | 0.836 | 175.452 |

| HN A53T - 10 ng | 0.232 | 0.241 | 0.237 | 32.714 |

The assay can be performed after determining the optimal amount to load for each sample (total protein for lysates and volume for media). Tables 7, 8, 9, and 10 depict optimal ODs of different cell lines’ lysates compared to the standards, while Tables 11 and 12 show the optimal volumes for media (Figure 4). Overall, ODs between 0.3–1.5 can be considered optimal and in the linear range.

Table 7.

ODs corresponding to standards for intracellular α-Syn in HN-A53T

| Standards (pg/mL) | OD 1 | OD 2 | OD mean |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 0.076 | 0.076 | 0.076 |

| 10.2 | 0.127 | 0.119 | 0.123 |

| 20.3 | 0.175 | 0.168 | 0.172 |

| 40.6 | 0.301 | 0.294 | 0.298 |

| 81.3 | 0.530 | 0.537 | 0.534 |

| 162.5 | 0.886 | 0.968 | 0.927 |

| 325 | 1.775 | 1.792 | 1.784 |

| 650 | 2.925 | 2.934 | 2.930 |

Table 8.

ODs corresponding to intracellular α-Syn in HN-A53T

| Samples | OD 1 | OD 2 | OD mean | Conc. (pg/mL) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HN A53T-Rep 1 | 0.665 | 0.665 | 0.665 | 118.222 |

| HN A53T-Rep 2 | 0.728 | 0.720 | 0.724 | 131.333 |

| HN A53T-Rep 3 | 0.782 | 0.802 | 0.792 | 146.444 |

Table 9.

ODs corresponding to standards for intracellular α-Syn in HN-TRPL

| Standards (pg/mL) | OD 1 | OD 2 | OD mean |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 0.076 | 0.077 | 0.077 |

| 10.2 | 0.090 | 0.088 | 0.089 |

| 20.3 | 0.124 | 0.123 | 0.124 |

| 40.6 | 0.197 | 0.196 | 0.197 |

| 81.3 | 0.318 | 0.352 | 0.335 |

| 162.5 | 0.710 | 0.698 | 0.704 |

| 325 | 1.381 | 1.280 | 1.331 |

| 650 | 2.550 | 2.457 | 2.504 |

Table 10.

ODs corresponding to intracellular α-Syn in HN-TRPL

| Samples | OD 1 | OD 2 | OD mean | Conc. (pg/mL) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HN TRPL-Rep 1 | 1.370 | 1.410 | 1.390 | 350.579 |

| HN TRPL-Rep 2 | 1.457 | 1.442 | 1.450 | 366.237 |

| HN TRPL-Rep 3 | 1.340 | 1.408 | 1.374 | 346.368 |

Table 11.

ODs corresponding to standards for extracellular α-Syn in HN-A53T

| Standards (pg/mL) | OD 1 | OD 2 | OD mean |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 0.079 | 0.079 | 0.079 |

| 10.2 | 0.131 | 0.128 | 0.130 |

| 20.3 | 0.188 | 0.179 | 0.184 |

| 40.6 | 0.280 | 0.277 | 0.279 |

| 81.3 | 0.535 | 0.482 | 0.509 |

| 162.5 | 0.914 | 0.87 | 0.892 |

| 325 | 1.597 | 1.563 | 1.580 |

| 650 | 2.706 | 2.675 | 2.691 |

Table 12.

ODs corresponding to extracellular α-Syn in HN-A53T and HN-TRPL

| Samples | OD 1 | OD 2 | OD mean | Conc. (pg/mL) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HN A53T-Rep 1 medium | 1.378 | 1.378 | 1.378 | 302.415 |

| HN A53T-Rep 2 medium | 1.288 | 1.270 | 1.279 | 278.268 |

| HN A53T-Rep 3 medium | 1.352 | 1.345 | 1.349 | 295.220 |

| HN TRPL-Rep 1 medium | 1.158 | 1.225 | 1.192 | 256.927 |

| HN TRPL-Rep 2 medium | 1.101 | 1.151 | 1.126 | 240.951 |

| HN TRPL-Rep 3 medium | 1.244 | 1.246 | 1.245 | 269.976 |

Immunoblotting

The monomeric form of α-Syn is extensively investigated both in mice and cultured cells, as it represents the easiest and most direct approach to study different aspects of PD and PD-related diseases.17,24,25 On the contrary, pS129 α-Syn can be easily detected in tissue samples but may require further processing to be detected in cell lysates via immunoblotting.21,22,23 Here we describe a straightforward approach to detect both monomeric α-Syn and pS129 α-Syn in both transfected HEK cells and iPSCs-induced neurons.

To our knowledge, the existing protocols do not clearly indicate detailed assays for the detection of multiple species of α-Syn in cultured cells using immunoblotting. The oligomerization of α-Syn is generally promoted in classic and rapid cell models (HEK and SH-SY5Y) using chemical/pharmacological approaches26 or through the exposure of pre-formed fibrils.27 On the other hand, it can be generally detected in aged iPSCs-derived neurons.27,28 Here we describe a new methodology to visualize multimeric forms of α-Syn in both transfected HEK cells and iPSCs-induced neurons. The approach includes dry transfer and crosslinking the PVDF immunoblot membrane using glutaraldehyde.

In this study, we show different step-by-step approaches to study multiple species of α-Syn via ELISA and immunoblotting. Detecting and investigating multiple forms of α-Syn, particularly pS129 and oligomers, is important in the context of PD and other synucleopathies, as these species are generally considered toxic and have been implicated in synaptic dysfunction, mitochondrial dysfunction, and cell-to-cell transmission.25,29,30,31 In Lewy Body Dementia (LBD) and Alzheimer’s Disease-related dementias, α-Syn exacerbates disease progression by forming Lewy bodies and enhancing the pathologies of Amyloid-β and Tau.32 Studying these forms can provide insights into disease mechanisms and significantly contribute to the development and testing of potential therapeutic interventions aimed at targeting these toxic forms.

Limitations

These protocols were specifically designed for cultured cells and induced neurons; therefore, it is expected to find some differences when working with other biological sources (e.g., cerebrospinal fluid or mouse brain). Adjustments should be considered due to the intrinsic differences of samples (e.g., increasing or decreasing the amount of total protein for ELISA/immunoblotting or optimizing the differentiation protocol according to new cell lines). Several ELISA kits are commercially available and may be used for quantification of α-Syn forms, and immunoblotting represents a great alternative or complementary approach to visualize and quantify these forms simultaneously.

Troubleshooting

Problem 1

Non-neuronal cells are present in the wells or the number of neurons looks different among the wells in the same plate (Step 3, CRITICAL, pg. 12).

Potential solution

-

•

Repeat the induction and increase the amount of virus used for the transduction.

-

•

Increase the amount of puromycin or extend the selection time.

-

•

If the number of neurons looks different in wells within the same plate, repeat the induction mixing well the solution paying more attention to the cell seeding.

Problem 2

The RIPA buffer does not cover the whole well of the plate (Step 7b, pg. 12).

Potential solution

-

•

Add more volume to the wells but this will dilute the samples.

-

•

Scrape the cells and incubate in a 1.5 mL Eppendorf tube.

Problem 3

ODs are not similar among the replicates (Step 16, pg. 13).

Potential solution

-

•

Repeat BCA assay to ensure reliability of the assay.

-

•

Ensure cell culture conditions are consistent among the wells. Repeat induction ensuring checking equal cell number/well/plate.

Problem 4

The solution in the samples’ wells appears darker than the standards (OD values exceed the OD of highest standard/detection range) (step 31, pg. 15).

Potential solution

-

•

Repeat the assay loading a less protein amount. Ideally, this problem should be addressed during the dilution test.

Problem 5

The bands in the blot appear misshapen or uneven (Step 42, pg. 17).

Potential solution

-

•

Repeat the sample preparation and mix well the solution containing samples with extraction buffer and master mix.

-

•

The protein concentration of the samples is too high. Add more 1X RIPA buffer to the working solution when preparing the samples.

-

•

Stop the run and add more running buffer to the tank. Ensure the gel is completely covered and there are no leaks.

Problem 6

The transfer is not optimal: the ladder is curved and/or the blot displays bubbles (Step 45, pg. 17).

Potential solution

-

•

When preparing the stack, make sure the gel remains in the same position. Issues can occur when the gel and the stacks are rolled improperly.

-

•

During gel transfer, avoid excessive squeezing/pressing of the gel.

Problem 7

The image of the blot shows darker areas and lighter areas, and/or there is too much background signal (Step 61, pg. 19).

Potential solution

-

•

The membrane dried out during processing (i.e., transfer, incubation, and so on). Repeat the membrane processing and ensure that the blot is always fully immersed in solution.

-

•

Reduce the concentration of primary/secondary antibody and wash more the blot.

-

•

Make sure you use a fresh blocking buffer. Also, if not properly mixed milk can form clumps that can be bound with antibodies.

Problem 8

The image shows many different non-specific bands (Step 74, pg. 20).

Potential solution

-

•

Reduce the concentration of primary/secondary antibody, and/or optimize the washing conditions and duration.

Resource availability

Lead contact

Further information and requests for resources and reagents should be directed to the lead contact, Dr. Abraam Yakoub (ayakoub@bwh.harvard.edu).

Technical contact

Further information and requests for resources and reagents should be directed to the technical contact, Dr. Abraam Yakoub (ayakoub@bwh.harvard.edu).

Materials availability

This study did not generate new unique reagents.

Data and code availability

This study did not generate/analyze data and/or code.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Joseph Mazzulli (Northwestern University) for kindly providing the A53T alpha-synuclein plasmid and the 2135 (healthy line) iPSCs. We also thank Dr. Rudolf Jaenisch (Whitehead Institute for Biomedical Research, Massachusetts Institute of Technology) for kindly providing iPSCs carrying the SNCA A53T mutation. We thank Dr. David Sulzer (Columbia University) for useful comments on the manuscript. We gratefully acknowledge funding from the National Institutes of Health (NIH), grant no. R01AG074899 and R01HL163814 to A.M.Y.

Author contributions

F.V.N. designed research, performed experiments, and wrote the first draft of the manuscript; G.M. performed experiments and revised the manuscript; Y.Z. provided training on experimental procedures and revised the manuscript; B.L. provided important comments and revised the manuscript; A.M.Y. designed research, revised the manuscript, and entirely supervised the project.

Declaration of interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

References

- 1.Jiang P., Ren L., Zhi L., Hu X., Xiao R.P. Protocol for cell preparation and gene delivery in HEK293T and C2C12 cells. STAR Protoc. 2021;2 doi: 10.1016/j.xpro.2021.100497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zhang Y., Pak C., Han Y., Ahlenius H., Zhang Z., Chanda S., Marro S., Patzke C., Acuna C., Covy J., et al. Rapid single-step induction of functional neurons from human pluripotent stem cells. Neuron. 2013;78:785–798. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2013.05.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Surmeier D.J. Determinants of dopaminergic neuron loss in Parkinson's disease. FEBS J. 2018;285:3657–3668. doi: 10.1111/febs.14607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Li L.X., Li Y.L., Wu J.T., Song J.Z., Li X.M. Glutamatergic Neurons in the Caudal Zona Incerta Regulate Parkinsonian Motor Symptoms in Mice. Neurosci. Bull. 2022;38:1–15. doi: 10.1007/s12264-021-00775-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chegao A., Guarda M., Alexandre B.M., Shvachiy L., Temido-Ferreira M., Marques-Morgado I., Fernandes Gomes B., Matthiesen R., Lopes L.V., Florindo P.R., et al. Glycation modulates glutamatergic signaling and exacerbates Parkinson's disease-like phenotypes. NPJ Parkinsons Dis. 2022;8:51. doi: 10.1038/s41531-022-00314-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gardoni F., Di Luca M. Targeting glutamatergic synapses in Parkinson's disease. Curr. Opin. Pharmacol. 2015;20:24–28. doi: 10.1016/j.coph.2014.10.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Taguchi Y.V., Liu J., Ruan J., Pacheco J., Zhang X., Abbasi J., Keutzer J., Mistry P.K., Chandra S.S. Glucosylsphingosine Promotes alpha-Synuclein Pathology in Mutant GBA-Associated Parkinson's Disease. J. Neurosci. 2017;37:9617–9631. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1525-17.2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Imberdis T., Negri J., Ramalingam N., Terry-Kantor E., Ho G.P.H., Fanning S., Stirtz G., Kim T.E., Levy O.A., Young-Pearse T.L., et al. Cell models of lipid-rich alpha-synuclein aggregation validate known modifiers of alpha-synuclein biology and identify stearoyl-CoA desaturase. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2019;116:20760–20769. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1903216116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sanyal A., Novis H.S., Gasser E., Lin S., LaVoie M.J. LRRK2 Kinase Inhibition Rescues Deficits in Lysosome Function Due to Heterozygous GBA1 Expression in Human iPSC-Derived Neurons. Front. Neurosci. 2020;14:442. doi: 10.3389/fnins.2020.00442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ho G.P.H., Ramalingam N., Imberdis T., Wilkie E.C., Dettmer U., Selkoe D.J. Upregulation of Cellular Palmitoylation Mitigates alpha-Synuclein Accumulation and Neurotoxicity. Mov. Disord. 2021;36:348–359. doi: 10.1002/mds.28346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fonseca-Ornelas L., Stricker J.M.S., Soriano-Cruz S., Weykopf B., Dettmer U., Muratore C.R., Scherzer C.R., Selkoe D.J. Parkinson-causing mutations in LRRK2 impair the physiological tetramerization of endogenous alpha-synuclein in human neurons. NPJ Parkinsons Dis. 2022;8:118. doi: 10.1038/s41531-022-00380-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hallacli E., Kayatekin C., Nazeen S., Wang X.H., Sheinkopf Z., Sathyakumar S., Sarkar S., Jiang X., Dong X., Di Maio R., et al. The Parkinson's disease protein alpha-synuclein is a modulator of processing bodies and mRNA stability. Cell. 2022;185:2035–2056.e33. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2022.05.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Suzuki H., Egawa N., Imamura K., Kondo T., Enami T., Tsukita K., Suga M., Yada Y., Shibukawa R., Takahashi R., Inoue H. Mutant alpha-synuclein causes death of human cortical neurons via ERK1/2 and JNK activation. Mol. Brain. 2024;17:14. doi: 10.1186/s13041-024-01086-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.White A.J., Clark K.A., Alexander K.D., Ramalingam N., Young-Pearse T.L., Dettmer U., Selkoe D.J., Ho G.P.H. A stem cell-based assay platform demonstrates alpha-synuclein dependent synaptic dysfunction in patient-derived cortical neurons. NPJ Parkinsons Dis. 2024;10:107. doi: 10.1038/s41531-024-00725-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Soldner F., Laganière J., Cheng A.W., Hockemeyer D., Gao Q., Alagappan R., Khurana V., Golbe L.I., Myers R.H., Lindquist S., et al. Generation of isogenic pluripotent stem cells differing exclusively at two early onset Parkinson point mutations. Cell. 2011;146:318–331. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.06.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mazzulli J.R., Mishizen A.J., Giasson B.I., Lynch D.R., Thomas S.A., Nakashima A., Nagatsu T., Ota A., Ischiropoulos H. Cytosolic catechols inhibit alpha-synuclein aggregation and facilitate the formation of intracellular soluble oligomeric intermediates. J. Neurosci. 2006;26:10068–10078. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0896-06.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mazzulli J.R., Zunke F., Isacson O., Studer L., Krainc D. alpha-Synuclein-induced lysosomal dysfunction occurs through disruptions in protein trafficking in human midbrain synucleinopathy models. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2016;113:1931–1936. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1520335113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Magalhaes P., Lashuel H.A. Opportunities and challenges of alpha-synuclein as a potential biomarker for Parkinson's disease and other synucleinopathies. NPJ Parkinsons Dis. 2022;8:93. doi: 10.1038/s41531-022-00357-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Menon S., Armstrong S., Hamzeh A., Visanji N.P., Sardi S.P., Tandon A. Alpha-Synuclein Targeting Therapeutics for Parkinson's Disease and Related Synucleinopathies. Front. Neurol. 2022;13 doi: 10.3389/fneur.2022.852003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Calabresi P., Mechelli A., Natale G., Volpicelli-Daley L., Di Lazzaro G., Ghiglieri V. Alpha-synuclein in Parkinson's disease and other synucleinopathies: from overt neurodegeneration back to early synaptic dysfunction. Cell Death Dis. 2023;14:176. doi: 10.1038/s41419-023-05672-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sasaki A., Arawaka S., Sato H., Kato T. Sensitive western blotting for detection of endogenous Ser129-phosphorylated alpha-synuclein in intracellular and extracellular spaces. Sci. Rep. 2015;5 doi: 10.1038/srep14211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dettmer U., Newman A.J., Luth E.S., Bartels T., Selkoe D. In vivo cross-linking reveals principally oligomeric forms of alpha-synuclein and beta-synuclein in neurons and non-neural cells. J. Biol. Chem. 2013;288:6371–6385. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.403311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Newman A.J., Selkoe D., Dettmer U. A new method for quantitative immunoblotting of endogenous alpha-synuclein. PLoS One. 2013;8 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0081314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Guan Y., Zhao X., Liu F., Yan S., Wang Y., Du C., Cui X., Li R., Zhang C.X. Pathogenic Mutations Differentially Regulate Cell-to-Cell Transmission of alpha-Synuclein. Front. Cell. Neurosci. 2020;14:159. doi: 10.3389/fncel.2020.00159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bengoa-Vergniory N., Roberts R.F., Wade-Martins R., Alegre-Abarrategui J. Alpha-synuclein oligomers: a new hope. Acta Neuropathol. 2017;134:819–838. doi: 10.1007/s00401-017-1755-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Harischandra D.S., Rokad D., Neal M.L., Ghaisas S., Manne S., Sarkar S., Panicker N., Zenitsky G., Jin H., Lewis M., et al. Manganese promotes the aggregation and prion-like cell-to-cell exosomal transmission of alpha-synuclein. Sci. Signal. 2019;12 doi: 10.1126/scisignal.aau4543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Frey B., AlOkda A., Jackson M.P., Riguet N., Duce J.A., Lashuel H.A. Monitoring alpha-synuclein oligomerization and aggregation using bimolecular fluorescence complementation assays: What you see is not always what you get. J. Neurochem. 2021;157:872–888. doi: 10.1111/jnc.15147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Delenclos M., Burgess J.D., Lamprokostopoulou A., Outeiro T.F., Vekrellis K., McLean P.J. Cellular models of alpha-synuclein toxicity and aggregation. J. Neurochem. 2019;150:566–576. doi: 10.1111/jnc.14806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Stojkovska I., Mazzulli J.R. Detection of pathological alpha-synuclein aggregates in human iPSC-derived neurons and tissue. STAR Protoc. 2021;2 doi: 10.1016/j.xpro.2021.100372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Killinger B.A., Melki R., Brundin P., Kordower J.H. Endogenous alpha-synuclein monomers, oligomers and resulting pathology: let's talk about the lipids in the room. NPJ Parkinsons Dis. 2019;5:23. doi: 10.1038/s41531-019-0095-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Alam P., Bousset L., Melki R., Otzen D.E. alpha-synuclein oligomers and fibrils: a spectrum of species, a spectrum of toxicities. J. Neurochem. 2019;150:522–534. doi: 10.1111/jnc.14808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Shim K.H., Kang M.J., Youn Y.C., An S.S.A., Kim S. Alpha-synuclein: a pathological factor with Abeta and tau and biomarker in Alzheimer's disease. Alzheimer's Res. Ther. 2022;14:201. doi: 10.1186/s13195-022-01150-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

This study did not generate/analyze data and/or code.