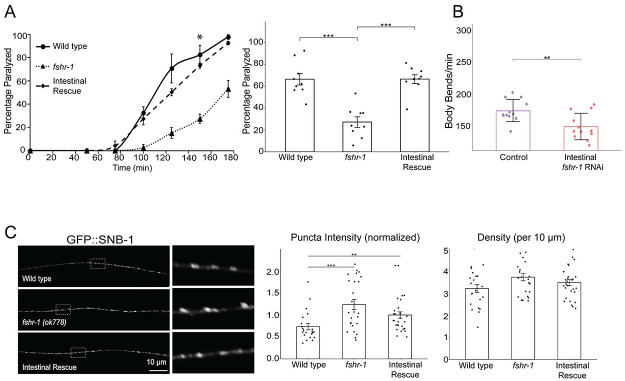

Fig 4. fshr-1 expression in the intestine is necessary and sufficient for neuromuscular function and structure.

(A, C) Intestinal rescue (Pges-1, ibtEx35) and (B) Intestine-specific RNAi [Pnhx-2::rde-1; rde-1(ne219)] effects on fshr-1 neuromuscular phenotypes. (A) (Left panel) Representative aldicarb assays showing the mean percentage of wild type, fshr-1(ok778) mutant, and intestinal rescue worms paralyzed on 1mM aldicarb ± s.e.m. for n = 3 plates of approximately 20 young adult animals per strain. (Right panel) Bar graphs showing cumulative data ± s.e.m.pooled from 3 independent aldicarb experiments for worms paralyzed at the timepoint indicated by an asterisk (*) in the left panel. Scatter points show individual plate averages. (B) Mean body bends per minute ± S.D. obtained in swimming experiments done on L4440 vector only-treated (Control) or fshr-1 RNAi-treated worms (Intestinal fshr-1 RNAi). (C) Wild type, fshr-1(ok778) mutant, and intestinal rescue worms that also expressed GFP::SNB-1 in ACh neurons were imaged using a 100x objective. (Left panels) Representative images of the dorsal nerve cords halfway between the vulva and the tail of young adult animals. Boxed areas are shown in higher resolution to the right of the main images. (Right panels) Quantification of normalized puncta (synaptic) intensity and puncta density (per 10 μm) ± s.e.m. Scatter points show individual worm means (n = 22–29 animals per genotype). One-way ANOVA and Tukey’s post hoc were used to compare the means of the datasets; *p ≤ 0.05, **p ≤ 0.01, ***p ≤ 0.001, **** p ≤ 0.0001, n.s., not significant.