Abstract

Background

Inflammation and nutrition are strongly linked to respiratory diseases, but the link between inflammation and nutrition-based indicators and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) and its mortality has not been reported.

Methods

We recruited adults no younger than 20 years old from the NHANES 1999–2018. Inflammation and nutrition-based indicators included NAR, PNI, MAR, RAR, HALP, and ALI. COPD were assessed through a self-report questionnaire. Participants’ mortality rates were determined by association with the National Death Index.

Results

A total of 46,572 individuals were collected in this study, including 1,549 COPD patients. NAR, MAR, and RAR were positively linked with the prevalence of COPD. However, PNI and HALP were negatively linked with the prevalence of COPD. In participants with COPD, the highest quartile of NAR (HR = 1.43 [1.04–1.97]), MAR (HR = 1.66 [1.23–2.26]), and RAR (HR = 2.45 [1.90–3.17]) were linked with an increased risk of all-cause mortality compared to the lowest quartile. However, the highest quartile of PNI (HR = 0.48 [0.38–0.61]) and HALP (HR = 0.56 [0.44–0.71]) were linked with a decreased risk of all-cause mortality compared to the lowest quartile. Randomized survival forests (RSF) showed that RAR had the strongest predictive power for all-cause mortality in COPD individuals among all indicators.

Conclusion

We found that inflammation and nutrition-based indicators were linked to prognosis in COPD patients, with RAR having the highest predictive value.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s41043-024-00709-x.

Keywords: RAR, COPD, Mortality, NHANES

Introduction

Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease (COPD) is a common respiratory disease that poses a huge burden on global public health [1]. According to research data, COPD is the third most common fatal disease in the world, leading to approximately 3 million deaths annually [2]. Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease (COPD) is a collective term for a group of lung diseases that share the common feature of pathological damage to lung tissue, leading to a decline in lung function [3]. COPD is mainly characterised by chronic cough, sputum, dyspnoea and chest tightness, as well as systemic symptoms such as weight reduction and loss of appetite [4]. COPD is mainly comprised of two types, chronic bronchitis and emphysema, and its pathogenesis is complex, often linked to environmental factors such as cigarette smoking, air pollution, and genes [5]. In addition to these known risk factors, inflammation and nutritional status may also be involved in the progression of COPD [6].

Inflammation is an essential feature of the pathophysiological process of COPD [7]. In the airways and lung tissues of COPD patients, chronic inflammatory responses are often present, including the release of cytokines, chemokines, and inflammatory mediators, which lead to narrowing of the airways and destruction of the alveolar [8]. These inflammatory responses not only aggravate the obstruction of the airways, but may also cause the occurrence of dyspnoea, thus aggravating the condition of COPD patients [9]. This inflammatory response is not limited to the lungs, but can also be detected in the peripheral blood as an increase in the number of pro-inflammatory cytokines, acute phase reactants, oxidative stress and activated inflammatory cells [10]. Nutritional status has been associated with the progression and prognosis of COPD [11]. COPD patients are often accompanied by abnormalities in nutritional status, including basal metabolic rate and metabolism [12]. Malnutrition not only affects immune function, but may also affect lung function, thus exacerbating COPD [13]. Therefore, it is significant to explore the link between inflammation and nutritional status and COPD to gain a new understanding of the pathogenesis of COPD.

In recent years, the relationship between inflammation and nutrition-related indicators and COPD has garnered significant attention from clinicians. While these composite indices are commonly used to assess the inflammatory and nutritional status of patients, most studies have focused on their inflammatory components, given the role of albumin as an acute phase protein. Few studies have systematically explored and compared the predictive value of these indices in relation to both COPD prevalence and all-cause mortality in COPD patients. The aim of this study was to evaluate whether these inflammation- and nutrition-based indicators are associated with COPD prevalence and to assess their utility in predicting all-cause mortality risk in COPD patients. Using data from adults who participated in the 1999–2018 National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES), we analyzed the associations beween six composite inflammation- and nutrition-based indicators and COPD prevalence. Additionally, we investigated the value of these indicators in predicting all-cause mortality among COPD patients, recognizing the dual role of these markers in reflecting both inflammatory processes and nutritional status.

Materials and methods

Study population

NHANES is a large cross-sectional survey based on the U.S. population designed to collect data on the nutrition, diet, and health status of the nation’s population [14]. The study is conducted by the National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS) and has been collecting data biennially since 1971. NHANES uses a complex, stratified, multi-stage whole population sample to collect relevant data including demographic, socio-economic, and physiological assessments, laboratory tests, and other nutritional health information. The study was approved by the NCHS Ethics Review Board and all participants signed an informed consent form.

For the 1999–2018 NHANES, we excluded participants younger than 20 years old and without information on COPD related assessment data (n = 46,240), participants without data for inflammation and nutritional indicators (n = 7,133), and participants who were pregnant (n = 1,289). After excluding participants did not complete follow-up (n = 82), a total of 46,572 participants were used for analysis (Figure S1).

Assessment of inflammation and nutrition-based indicators

Red cell distribution width (RDW) reflects the heterogeneity of erythrocyte volume and has traditionally been used in the differential diagnosis of anaemia [15]. Neutrophil-albumin ratio (NAR) is a composite indicator of peripheral blood neutrophil and lymphocyte counts, representing a state of systemic inflammation [16]. Prognostic nutritional index (PNI), a novel immunonutritional risk indicator calculated from albumin and total lymphocyte counts, was first proposed in 1984 and was initially used to assess cancer prognosis [17]. Monocyte-albumin ratio (MAR), calculated from the ratio of monocytes to albumin, reflects systemic inflammation and nutritional status [18]. Red cell distribution width-albumin ratio (RAR) is a newly identified risk marker and has been linked with prognosis in a wide range of inflammatory diseases [19]. Hemoglobin, albumin, lymphocyte, and platelet (HAlP) is a novel immunonutritional marker to predict clinical outcomes in oncology patients [20]. Advanced lung cancer inflammation index (ALI), originally used to assess systemic levels of inflammation in cancer patients, is a combination of body weight, albumin, and neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio index [21]. Table S1 demonstrates the calculation methods of combination in each inflammation and nutrition-based indicators.

Assessment of COPD and all-cause mortality

Participants with COPD were defined as meeting at least one of the following criteria: (1) having ever been told by a healthcare provider that they had emphysema, or (2) being over 40 years old, having a history of smoking or a diagnosis of chronic bronchitis, and using medications commonly prescribed for COPD (such as selective phosphodiesterase-4 inhibitors, mast cell stabilizers, leukotriene modifiers, or inhaled corticosteroids) [22].

NHANES records deaths through linkage to the National Mortality Index, and follow-up ends on December 31, 2019. All-cause death was defined as the total death from all causes within a given period.

Covariates

Information on age, sex, race, education, and marital status was collected. According to age, participants were divided into three groups (20–39 years, 40–59 years, and ≥ 60 years). According to marital status, they were divided into married/living with partner and single/divorced/widowed. The comprehensive definition of other covariates can be found in the supplementary materials, including family poverty income ratio (PIR, ≤ 1.0, 1.1–3.0, or > 3.0), smoking status (never, former, or current smoker), drinking status (nondrinker, former drinker, or current drinker), physical activity (inactive, insufficiently active, or active), healthy eating index (HEI), and Charlson comorbidity index (CCI) [23–28].

Statistical analysis

The demographic descriptive statistics were calculated using sampling weights. Normally distributed continuous variables are described as means ± SEs, and continuous variables without a normal distribution are presented as medians [interquartile ranges]. Categorical variables are presented as numbers (percentages). Continuous variables were compared using Student’s t-test (for normal distribution) or Mann-Whitney U test (for non-normal distribution), while categorical variables were compared using the chi-square test. The correlation coefficients between inflammation and nutrition-based indicators and other parameters were calculated using Spearman’s correlation analysis. All analyses were performed using R (version 4.2.0) and P-values less than 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Logistic regression analyses were used to examine the link between inflammation and nutrition-based indicators and the prevalence of COPD. COX proportional hazard regression analyses were used to assess the link of inflammation and nutrition-based indicators with all-cause mortality in COPD patients. Restricted cubic spline curve (RCS) is used to investigate whether there is a non-linear link in the above relationships. The log-rank test was performed to assess survival in various groups using Kaplan-Meier survival curves. The ability of these metrics to predict all-cause mortality in COPD patients was assessed by receiver operating characteristic curves (ROC). The usefulness of inflammation and nutrition-based indicators in predicting all-cause death in COPD patients was compared using a random subsistence forest method. In addition, we analysed the link between inflammation and nutrition-based indicators and other parameters with the prevalence of COPD and all-cause mortality.

Results

Baseline characteristics of the participants

Table 1 summarizes the initial traits of 46,572 individuals, including 1,549 COPD patients. The percentage of participants aged 20–39 years was 37%, 40–59 years was 38.13%, and ≥ 60 years was 24.87%. 51.98% were female and 48.92% were male. Participants with COPD were older, more likely to be non-Hispanic White, highly educated, medium economic level, less active, former or current smokers, and had highly CCI. Notably, NAR, MAR, RAR, and ALI were significantly higher in COPD patients, while PNI and HALP was significantly lower in COPD patients (P < 0.05). Table S1 presents baseline characteristics of participants with COPD according to all-cause mortality.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of adult participants according to COPD in NHANES 1999–2018

| Characteristics | Total | COPD | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No (n = 45023) | Yes (n = 1549) | |||

| Age, % | < 0.01 | |||

| 20–39 years | 15,221(37.00) | 15,185(38.06) | 36(2.87) | |

| 40–59 years | 15,317(38.13) | 14,845(38.11) | 472(38.67) | |

| ≥ 60 years | 16,034(24.87) | 14,993(23.83) | 1041(58.46) | |

| Sex, % | 0.04 | |||

| Female | 23,476(51.08) | 22,736(50.97) | 740(54.70) | |

| Male | 23,096(48.92) | 22,287(49.03) | 809(45.30) | |

| Race/ethnicity, % | < 0.01 | |||

| Non-Hispanic White | 20,806(68.90) | 19,792(68.50) | 1014(81.95) | |

| Non-Hispanic Black | 9413(10.55) | 9164(10.66) | 249(7.07) | |

| Other race | 16,353(20.54) | 16,067(20.84) | 286(10.98) | |

| Marital status, % | < 0.01 | |||

| Married/living with partner | 18,446(35.94) | 17,707(35.77) | 739(41.18) | |

| Single/divorced/widowed | 28,126(64.06) | 27,316(64.23) | 810(58.82) | |

| Education level, % | < 0.01 | |||

| Below high school | 12,537(17.17) | 12,004(16.88) | 533(26.35) | |

| High school | 10,774(24.03) | 10,388(23.95) | 386(26.42) | |

| Above high school | 23,261(58.80) | 22,631(59.16) | 630(47.23) | |

| Family PIR, % | < 0.01 | |||

| ≤ 1.0 | 9572(14.27) | 9171(14.10) | 401(19.79) | |

| 1.1–3.0 | 19,712(36.20) | 18,984(35.99) | 728(43.04) | |

| > 3.0 | 17,288(49.53) | 16,868(49.91) | 420(37.16) | |

| Smoking status, % | < 0.01 | |||

| Never smoker | 25,126(53.61) | 24,918(54.83) | 208(14.34) | |

| Former smoker | 11,608(24.78) | 10,791(23.97) | 817(51.01) | |

| Current smoker | 9838(21.61) | 9314(21.20) | 524(34.65) | |

| Drinking status, % | 0.12 | |||

| Nondrinker | 10,661(18.55) | 10,306(18.47) | 355(21.10) | |

| Low-to-moderate drinker | 32,123(71.85) | 31,069(71.94) | 1054(69.01) | |

| Heavy drinker | 3788(9.60) | 3648(9.59) | 140(9.90) | |

| Physical activity, % | < 0.01 | |||

| Inactive | 12,645(21.87) | 11,975(21.30) | 670(40.22) | |

| Insufficiently active | 17,267(40.17) | 16,797(40.46) | 470(30.68) | |

| Active | 16,660(37.96) | 16,251(38.24) | 409(29.10) | |

| HEI-2015 score | 49.66(40.52,59.48) | 49.70(40.57,59.48) | 48.61(38.99,58.41) | 0.04 |

| CCI | 0.85(0.01) | 0.82(0.01) | 2.08(0.07) | < 0.01 |

| Inflammation and nutritional indicators | ||||

| Neutrophil, 103/µL | 4.00(3.20,5.10) | 4.00(3.10,5.10) | 4.60(3.50,5.70) | < 0.01 |

| Lymphocyte, 103/µL | 2.00(1.60,2.50) | 2.00(1.60,2.50) | 2.00(1.50,2.50) | < 0.01 |

| Monocyte, 103/µL | 0.50(0.40,0.70) | 0.50(0.40,0.70) | 0.60(0.50,0.70) | < 0.01 |

| Hemoglobin, g/dL | 14.40(13.40,15.40) | 14.40(13.40,15.40) | 14.20(13.20,15.20) | 0.04 |

| RDW, % | 12.80(12.30,13.50) | 12.80(12.30,13.50) | 13.30(12.70,14.10) | < 0.01 |

| Platelet, 103/µL | 246.00(210.00,290.00) | 246.00(210.00,290.00) | 252.00(209.00,303.00) | 0.03 |

| Serum albumin, g/L | 43.00(41.00,45.00) | 43.00(41.00,45.00) | 42.00(40.00,44.00) | < 0.01 |

| Body mass index, kg/m2 | 27.66(24.06,32.12) | 27.62(24.04,32.07) | 28.60(24.47,34.10) | < 0.01 |

| Inflammation/nutrition-based indicators | ||||

| NAR | 0.09(0.07,0.12) | 0.09(0.07,0.12) | 0.11(0.08,0.14) | < 0.01 |

| PNI | 53.50(50.50,56.50) | 53.50(50.50,56.50) | 51.50(48.50,55.00) | < 0.01 |

| MAR | 0.01(0.01,0.02) | 0.01(0.01,0.02) | 0.01(0.01,0.02) | < 0.01 |

| RAR | 0.30(0.28,0.33) | 0.30(0.28,0.32) | 0.32(0.30,0.36) | < 0.01 |

| HALP score | 50.58(38.95,65.67) | 50.68(39.11,65.73) | 47.04(33.38,62.84) | < 0.01 |

| ALI | 238.33(173.88,326.72) | 237.33(173.48,324.76) | 280.27(194.81,411.57) | < 0.01 |

Abbreviations: HEI-2015, Healthy Eating Index 2015; CCI, Charlson Comorbidity Index; RDW, red cell distribution width; NAR, neutrophil-albumin ratio; PNI, prognostic nutritional index; MAR, monocyte-albumin ratio; RAR, red cell distribution width-albumin ratio; HALP, hemoglobin, albumin, lymphocyte, and platelet; ALI, advanced lung cancer inflammation index. Normally distributed continuous variables are described as means ± SEs, and continuous variables without a normal distribution are presented as medians [interquartile ranges]. Categorical variables are presented as numbers (percentages). N reflect the study sample while percentages reflect the survey-weighted data

The link between inflammation and nutrition-based indicators and COPD prevalence

In the crude model, we observed positive links between NAR, MAR, RAR, ALI, and the prevalence of COPD (Table 2). However, we observed negative links between PNI, HALP, and the prevalence of COPD. After adjusting for some confounding factors, including age, sex, race/ethnicity, marital status, education level, family PIR, drinking status, smoking status, physical activity, HEI, and CCI, these relationships remained statistically significant. Compared to the first quartile, the fourth quartile of NAR (OR = 1.71 [1.35–2.18]), MAR (OR = 1.38 [1.09–1.76]), and RAR (OR = 2.11 [1.65–2.70]) were positively linked with the prevalence of COPD after multivariable adjustment. However, the fourth quartile of PNI (OR = 0.75 [0.59–0.95]) and HALP (OR = 0.64 [0.53–0.77]) were negatively linked with the prevalence of COPD, compared to the first quartile. RCS analysis showed that the relationship between NAR, PNI, MAR and COPD prevalence was linear (P for non-linearity > 0.05), whereas the relationship between RAR, HALP and COPD prevalence was non-linear, with inflection points of 0.32 and 44.41 (P for non-linearity < 0.05) (Figure S2). We further analyzed the association between specific components of inflammation and nutritional status (e.g., neutrophils, monocytes, RDW, platelets, and serum albumin) and the prevalence of COPD (Table S3), finding a strong correlation with COPD prevalence.

Table 2.

Logistic regression analysis of the relationship between inflammation/nutrition-based indicators and the prevalence of COPD among adults in NHANES 1999–2018

| Quartiles of inflammation/nutrition-based indicators | P trend | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR | OR (95% CI) | OR (95% CI) | OR (95% CI) | ||

| NAR | |||||

| Crude | 1 [Reference] | 1.31 (1.04–1.66) | 1.79 (1.45–2.21) | 2.93 (2.35–3.65) | < 0.01 |

| Model 1 | 1 [Reference] | 1.20 (0.95–1.52) | 1.60 (1.29–1.98) | 2.78 (2.23–3.47) | < 0.01 |

| Model 2 | 1 [Reference] | 1.06 (0.84–1.34) | 1.23 (0.98–1.54) | 1.71 (1.35–2.18) | < 0.01 |

| PNI | |||||

| Crude | 1 [Reference] | 0.57 (0.47–0.69) | 0.50 (0.42–0.60) | 0.44 (0.36–0.54) | < 0.01 |

| Model 1 | 1 [Reference] | 0.72 (0.59–0.87) | 0.77 (0.64–0.93) | 0.85 (0.69–1.06) | 0.06 |

| Model 2 | 1 [Reference] | 0.74 (0.60–0.92) | 0.81 (0.66–0.99) | 0.75 (0.59–0.95) | 0.02 |

| MAR | |||||

| Crude | 1 [Reference] | 1.09 (0.86–1.37) | 1.64 (1.30–2.07) | 2.41 (1.94-3.00) | < 0.01 |

| Model 1 | 1 [Reference] | 1.06 (0.84–1.35) | 1.48 (1.17–1.86) | 1.96 (1.57–2.45) | < 0.01 |

| Model 2 | 1 [Reference] | 0.98 (0.77–1.25) | 1.26 (0.98–1.61) | 1.38 (1.09–1.76) | < 0.01 |

| RAR | |||||

| Crude | 1 [Reference] | 2.28 (1.82–2.85) | 2.98 (2.36–3.77) | 5.02 (4.01–6.29) | < 0.01 |

| Model 1 | 1 [Reference] | 1.63 (1.30–2.05) | 1.89 (1.49–2.41) | 3.04 (2.41–3.84) | < 0.01 |

| Model 2 | 1 [Reference] | 1.51 (1.19–1.90) | 1.56 (1.23–1.97) | 2.11 (1.65–2.70) | < 0.01 |

| HALP | |||||

| Crude | 1 [Reference] | 0.61 (0.51–0.73) | 0.57 (0.47–0.70) | 0.58 (0.49–0.69) | < 0.01 |

| Model 1 | 1 [Reference] | 0.70 (0.59–0.84) | 0.73 (0.59–0.89) | 0.80 (0.66–0.95) | 0.03 |

| Model 2 | 1 [Reference] | 0.71 (0.58–0.86) | 0.69 (0.55–0.86) | 0.64 (0.53–0.77) | < 0.01 |

| ALI | |||||

| Crude | 1 [Reference] | 0.91 (0.71–1.17) | 1.20 (0.97–1.48) | 1.89 (1.54–2.32) | < 0.01 |

| Model 1 | 1 [Reference] | 0.82 (0.63–1.06) | 1.01 (0.81–1.25) | 1.43 (1.17–1.75) | < 0.01 |

| Model 2 | 1 [Reference] | 0.84 (0.64–1.09) | 0.98 (0.79–1.22) | 1.23 (0.99–1.53) | < 0.01 |

Abbreviations: NAR, neutrophil-albumin ratio; PNI, prognostic nutritional index; MAR, monocyte-albumin ratio; RAR, red cell distribution width-albumin ratio; HALP, hemoglobin, albumin, lymphocyte, and platelet; ALI, advanced lung cancer inflammation index; Model 1: Adjusted for age (20–39, 40–59, or ≥ 60 years), sex (male or female), and race/ethnicity (non-Hispanic White, non-Hispanic Black or other race); Model 2: Model 1 + marital status (married/living with partner, or single/divorced/widowed), education level (below high school, high school, or above high school), family PIR (≤ 1.0, 1.1–3.0, or > 3.0), drinking status (nondrinker, former drinker, or current drinker), smoking status (never smoker, former smoker, or current smoker, physical activity (inactive, insufficiently active, or active), HEI (in quartiles), and CCI (continous)

Association of inflammation and nutrition-based indicators with all-cause mortality in participants with COPD

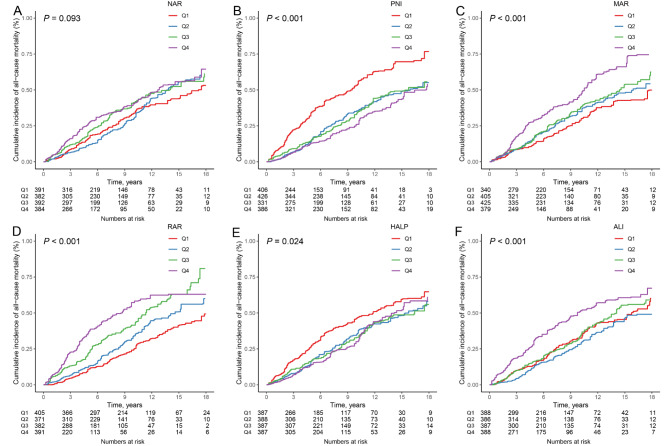

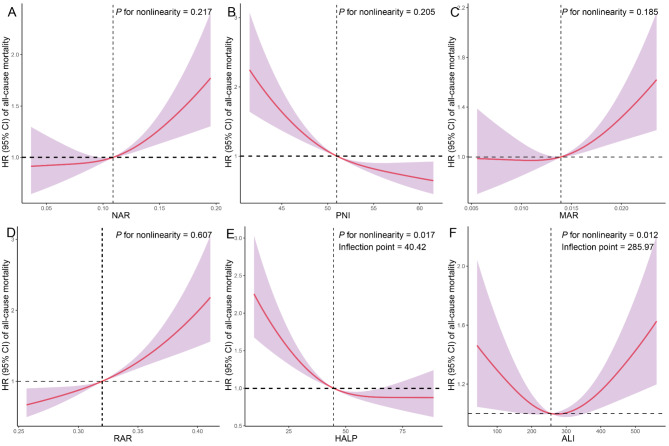

During a median follow-up of 6.92 years, 657 all-cause deaths were observed. Kaplan-Meier survival curves for inflammation and nutrition-based indicators and all-cause mortality in COPD participants are shown in Fig. 1A-F. As can be seen, participants with COPD who had high NAR, MAR, and RAR had the highest risk of all-cause mortality compared with participants who did not have COPD (log-rank P < 0.001). However, participants with COPD who had high PNI and HALP had the lowest risk of all-cause mortality compared with participants who did not have COPD (log-rank P < 0.001). In the crude model and model 1, participants with COPD in the highest quartile of NAR, MAR, and RAR were associated with a significantly increased risk of all-cause mortality compared to those in the lowest quartile (Table 3). However, all-cause mortality was significantly decreased in COPD participants with high PNI and HALP compared with controls. In participants with COPD, the highest quartile of NAR (HR = 1.43 [1.04–1.97]), MAR (HR = 1.66 [1.23–2.26]), and RAR (HR = 2.45 [1.90–3.17]) were linked with an increased risk of all-cause mortality compared to the lowest quartile after multivariable adjustment. However, the highest quartile of PNI (HR = 0.48 [0.38–0.61]) and HALP (HR = 0.56 [0.44–0.71]) were linked with a decreased risk of all-cause mortality compared to the lowest quartile. RCS analyses showed that the relationship between NAR, PNI, MAR, RAR and all-cause mortality in COPD patients was linear (P for non-linearity > 0.05), whereas the relationship between HALP and all-cause mortality in COPD patients was non-linear, with inflection points of 0.32 and 40.42 (P for non-linearity < 0.05) (Fig. 2A-F). We also looked at the relationship between specific components of inflammation and nutritional status and all-cause mortality in COPD patients (Table S4 and Figure S3).

Fig. 1.

Kaplan-Meier survival curves for quartiles of inflammation and nutrition-based indicators (A: NAR; B: PNI; C: MAR; D: RAR; E: HALP; F: ALI) and all-cause mortality in patients with COPD. NAR, neutrophil-albumin ratio; PNI, prognostic nutritional index; MAR, monocyte-albumin ratio; RAR, red cell distribution width-albumin ratio; HALP, hemoglobin, albumin, lymphocyte, and platelet; ALI, advanced lung cancer inflammation index

Table 3.

COX regression analysis of the relationship between inflammation/nutrition-based indicators and all-cause mortality among adults with COPD in NHANES 1999–2018

| Quartiles of inflammation/nutrition-based indicators | P trend | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR | HR (95% CI) | HR (95% CI) | HR (95% CI) | ||

| NAR | |||||

| Crude | 1 [Reference] | 1.06 (0.80–1.41) | 1.27 (0.94–1.70) | 1.46 (1.07–2.01) | 0.01 |

| Model 1 | 1 [Reference] | 0.98 (0.72–1.33) | 1.34 (0.97–1.85) | 1.65 (1.20–2.27) | < 0.01 |

| Model 2 | 1 [Reference] | 0.87 (0.64–1.17) | 1.15 (0.81–1.63) | 1.43 (1.04–1.97) | 0.01 |

| PNI | |||||

| Crude | 1 [Reference] | 0.51 (0.39–0.66) | 0.50 (0.37–0.66) | 0.41 (0.32–0.53) | < 0.01 |

| Model 1 | 1 [Reference] | 0.56 (0.44–0.71) | 0.52 (0.40–0.69) | 0.52 (0.41–0.67) | < 0.01 |

| Model 2 | 1 [Reference] | 0.56 (0.45–0.71) | 0.50 (0.37–0.67) | 0.48 (0.38–0.61) | < 0.01 |

| MAR | |||||

| Crude | 1 [Reference] | 1.23 (0.87–1.73) | 1.33 (0.99–1.79) | 2.08 (1.54–2.80) | < 0.01 |

| Model 1 | 1 [Reference] | 1.03 (0.73–1.46) | 1.14 (0.86–1.51) | 1.70 (1.28–2.25) | < 0.01 |

| Model 2 | 1 [Reference] | 1.08 (0.76–1.55) | 1.08 (0.79–1.48) | 1.66 (1.23–2.26) | < 0.01 |

| RAR | |||||

| Crude | 1 [Reference] | 1.39 (1.06–1.82) | 2.03 (1.51–2.72) | 2.86 (2.13–3.86) | < 0.01 |

| Model 1 | 1 [Reference] | 1.35 (1.05–1.75) | 1.66 (1.23–2.23) | 2.77 (2.10–3.67) | < 0.01 |

| Model 2 | 1 [Reference] | 1.34 (1.04–1.74) | 1.50 (1.12–2.01) | 2.45 (1.90–3.17) | < 0.01 |

| HALP | |||||

| Crude | 1 [Reference] | 0.71 (0.55–0.93) | 0.68 (0.48–0.97) | 0.65 (0.47–0.91) | 0.02 |

| Model 1 | 1 [Reference] | 0.68 (0.53–0.86) | 0.64 (0.48–0.87) | 0.68 (0.53–0.86) | < 0.01 |

| Model 2 | 1 [Reference] | 0.63 (0.50–0.79) | 0.61 (0.45–0.81) | 0.56 (0.44–0.71) | < 0.01 |

| ALI | |||||

| Crude | 1 [Reference] | 0.81 (0.60–1.10) | 1.05 (0.81–1.38) | 1.69 (1.25–2.28) | < 0.01 |

| Model 1 | 1 [Reference] | 0.85 (0.64–1.13) | 0.87 (0.67–1.14) | 1.43 (1.05–1.96) | 0.01 |

| Model 2 | 1 [Reference] | 0.82 (0.64–1.06) | 0.89 (0.69–1.14) | 1.36 (0.99–1.85) | 0.01 |

Abbreviations: NAR, neutrophil-albumin ratio; PNI, prognostic nutritional index; MAR, monocyte-albumin ratio; RAR, red cell distribution width-albumin ratio; HALP, hemoglobin, albumin, lymphocyte, and platelet; ALI, advanced lung cancer inflammation index; Model 1: Adjusted for age (20–39, 40–59, or ≥ 60 years), sex (male or female), and race/ethnicity (non-Hispanic White, non-Hispanic Black or other race); Model 2: Model 1 + marital status (married/living with partner, or single/divorced/widowed), education level (below high school, high school, or above high school), family PIR (≤ 1.0, 1.1–3.0, or > 3.0), drinking status (nondrinker, former drinker, or current drinker), smoking status (never smoker, former smoker, or current smoker), physical activity (inactive, insufficiently active, or active), HEI (in quartiles), and CCI (continous)

Fig. 2.

Restricted cubic spline (RCS) analysis with multivariate-adjusted associations of inflammation/nutrition-based indicators (A: NAR; B: PNI; C: MAR; D: RAR; E: HALP; F: ALI) with all-cause mortality in patients with COPD. Models are adjusted for age (20–39, 40–59, or ≥ 60 years), sex (male or female), race/ethnicity (non-Hispanic White, non-Hispanic Black or other race), marital status (married/living with partner, or single/divorced/widowed), education level (below high school, high school, or above high school), family PIR (≤ 1.0, 1.1–3.0, or > 3.0), drinking status (nondrinker, former drinker, or current drinker), smoking status (never smoker, former smoker, or current smoker), physical activity (inactive, insufficiently active, or active), HEI (in quartiles), and CCI (continous). NAR, neutrophil-albumin ratio; PNI, prognostic nutritional index; MAR, monocyte-albumin ratio; RAR, red cell distribution width-albumin ratio; HALP, hemoglobin, albumin, lymphocyte, and platelet; ALI, advanced lung cancer inflammation index; GNRI, geriatric nutrition risk index; CONUT, controlling nutritional status

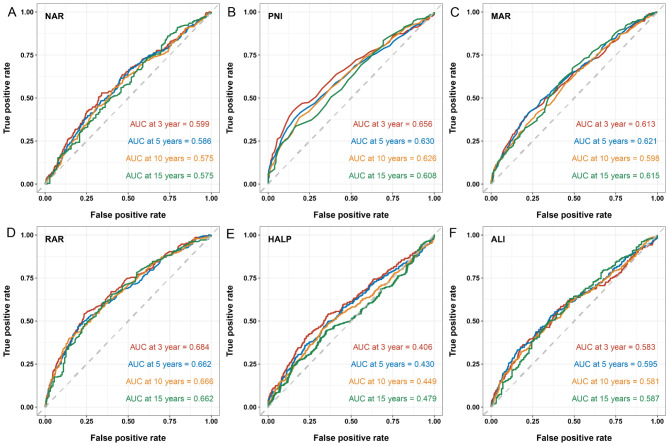

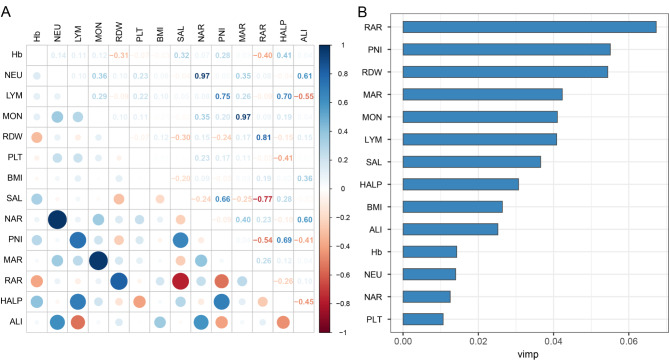

The value of inflammation and nutrition-based indicators in assessing the risk of all-cause mortality in patients with COPD

Based on the ROC curve analysis, we found that RAR was the strongest predictor of all-cause mortality in COPD patients (AUC at 3 years = 0.68) (Fig. 3A-F). The correlations between inflammation and nutrition-based indicators and other parameters were showed in Fig. 4A. We found a strong positive link between PNI and HALP (r = 0.69) and a strong negative link between PNI and RAR (r=-0.54). Among all inflammation and nutrition-based indicators and other parameters, RAR has the highest value in predicting all-cause mortality in COPD patients (Fig. 4B).

Fig. 3.

Predictive value of time-dependent ROC assessment of inflammation and nutrition-based indicators (A: NAR; B: PNI; C: MAR; D: RAR; E: HALP; F: ALI) for 3-, 5-, and 10-year all-cause mortality. NAR, neutrophil-albumin ratio; PNI, prognostic nutritional index; MAR, monocyte-albumin ratio; RAR, red cell distribution width-albumin ratio; HALP, hemoglobin, albumin, lymphocyte, and platelet; ALI, advanced lung cancer inflammation index

Fig. 4.

Prognostic value of inflammation and nutrition-based indicators. (A) Spearman correlation analysis was used to calculate the correlation coefficients among inflammation and nutrition-based indicators and other parameters. (B) A random subsistence forest method was used to compare the value of inflammation and nutrition-based indicators and other parameters in predicting all-cause mortality in COPD patients

Discussion

A total of 46,572 individuals were collected in this study, including 1,549 COPD patients. We found that NAR, MAR, and RAR were positively linked with the prevalence of COPD. However, PNI and HALP were negatively linked with the prevalence of COPD. In participants with COPD, high NAR, MAR, and RAR were linked with an increased risk of all-cause mortality. However, high PNI and HALP were linked with a decreased risk of all-cause mortality. Among these, RAR is the strongest inflammation and nutrition-based indicator to predict the risk of death in COPD patients.

Poor nutritional status and systemic inflammatory response are known to be linked to poor prognosis in COPD patients [29]. Of the six inflammation and nutrition-based indicators we examined, several have been shown to be linked to COPD. PNI is an indicator of immunonutritional status. Suzuki’s study showed that a low PNI was linked to worsening of the disease in COPD patients [30]. HALP is a new indicator of systemic inflammation and nutritional status. Han et al. showed that low HALP scores were linked to an increased risk of death in patients with acute exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (AECOPD) [31]. In our study, compared to the first quartile, COPD prevalence increased by 171.4%, 138.2%, and 210.7% in the fourth quartile of NAR, MAR, and RAR, respectively. However, COPD prevalence decreased by 24.9% and 26.2% in the fourth quartile of PNI and HALP, respectively. In participants with COPD, compared to the lowest quartile, all-cause mortality increased by 143.3%, 166.4%, and 245.3% in the highest quartile of NAR, MAR, and RAR, respectively. However, all-cause mortality decreased by 51.9% and 44.3% in the fourth quartile of PNI and HALP, respectively. It is noteworthy that RAR not only shows a high correlation with the prevalence of COPD, but is also the best predictor of the risk of death in COPD patients.

RAR is defined as the ratio of RDW to albumin [32]. Previous studies have shown that high RDW and hypoalbuminaemia are markers of poor prognosis in patients with COPD. RDW reflects the degree of heterogeneity in erythrocyte volume and has been found to link to the prognosis of a variety of respiratory diseases [15]. Early studies have shown that elevated RDW is linked to the severity of COPD and the risk of mortality [33, 34]. Epstein et al. also confirmed that RDW is an independent prognostic factor for poor outcome in AECOPD patients [35]. Hypoxia is a common complication in patients with advanced COPD. Acute episodes of hypoxia can stimulate the production of erythropoietin, which induces erythrocytosis and may contribute to an increase in RDW in COPD patients [36]. Serum albumin levels are linked to the nutritional status of the organism and play an essential role in the maintenance of body homeostasis [37]. COPD is a chronic inflammatory disease and albumin is susceptible to oxidation under conditions of oxidative stress and chronic inflammation, leading to marked hypoalbuminaemia [38]. Serum albumin levels are a valid parameter for assessing post-hospital mortality and long-term survival in patients with AECOPD [39]. Lower albumin was identified as one of the strongest predictors of mortality in patients with AECOPD in a retrospective cohort study that included 574 participants [40].

RAR has been linked to clinical results in a range of respiratory illnesses. Yoo et al. showed that RAR was significantly linked to 60-day mortality in patients with acute respiratory distress syndrome [41]. Jeong et al. demonstrated that in critically ill patients with pneumonia, a higher RAR ratio was linked to a significantly increased 28-day mortality rate [42]. Currently, the link between RAR and COPD is controversial. Eraslan et al. showed that RAR was higher in COPD patients who were hospitalised for 10 days or more, but there was no significant correlation with 30-day mortality [43]. However, their study sample size was small and susceptible to selective bias. Qiu et al. found that higher RAR was linked to an increased risk of death in COPD patients in the intensive care unit. They demonstrated that RAR can independently predict in-hospital mortality in critically ill COPD patients [44]. Our study also found that RAR was more effective than other inflammation and nutrition-based indicators in predicting mortality in COPD patients. We hypothesised that the mechanism by which RAR predicts mortality in COPD may be related to hypoxia, inflammation and malnutrition. COPD patients suffer from long-term chronic inflammation, and the systemic inflammatory process can lead to catabolic stress in the patients [45]. Under the influence of systemic inflammatory stress, COPD patients are at significantly increased risk of malnutrition [46]. Malnutrition in COPD patients leads to impairment of respiratory muscle function, progression of disease severity, and also has a negative impact on mortality rates [47].

This study has several strengths. First, this study used a representative sample of the US population, and all measurements were performed according to a standardised protocol, which is highly persuasive. Second, we not only examined the links between the six inflammation and nutrition-based indicators and the prevalence of COPD, but also conducted prognostic analyses to explore the links between the inflammation and nutrition-based indicators and all-cause mortality in patients with COPD. Although this study found an association between inflammation and nutrition and COPD and its all-cause mortality, we have to acknowledge some limitations of the study. First, the data for this study were extracted from a public database and were limited to the US population. Second, this study only analysed single-measurement inflammation and nutrition-based indicators and did not analyse their dynamically evolving values, ignoring the impact of dynamic changes in these indicators. Third, the absence of consistent data on C-reactive protein (CRP) or other acute phase reactants across all NHANES survey cycles limited our ability to directly account for acute inflammation in the analysis. Therefore, the potential effects of unmeasured acute inflammatory responses cannot be entirely ruled out. Fourth, the specific causes of COPD in participants, particularly those diagnosed before age 39, could not be confirmed. Factors such as alpha-1 antitrypsin deficiency may have contributed to early-onset COPD, potentially influencing the interpretation of the findings. Finally, differentiating between asthma and COPD in this population-based study posed a challenge due to the overlapping clinical features of these conditions. Although we employed a multi-criteria approach based on age, smoking history, self-reported emphysema, chronic bronchitis, and medication use, the possibility of misclassification remains, potentially introducing inclusion bias. Future studies using more precise diagnostic criteria or longitudinal data could help mitigate this issue and improve differentiation between these respiratory conditions.

Conclusion

This study demonstrated that inflammation and nutrition-based indicators are significantly associated with the prevalence of COPD. High NAR, MAR, RAR, and ALI were positively linked with the prevalence of COPD, whereas high PNI and HALP showed an inverse association. Among individuals with COPD, higher levels of NAR, MAR, and RAR were associated with an increased risk of all-cause mortality, while higher levels of PNI and HALP were linked to a decreased risk. Notably, RAR was identified as the strongest predictor of mortality risk among all indicators.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

We appreciate the people who contributed to the NHANES data we studied.

Author contributions

The authors’ responsibilities were as follows—XC: designed the research, and had primary responsibility for the final content; KC: conducted analyses and wrote the first draft of the paper; XM: revised the manuscript; and all authors: read and approved the final manuscript and approved the final submitted version.

Funding

None.

Data availability

NHANES data described in this manuscript are available at https://wwwn.cdc.gov/nchs/nhanes/..

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

All participants provided written informed consent and study procedures were approved by the National Center for Health Statistics Research Ethics Review Board (Protocol Number: Protocol #98-12, Protocol #2005-06, and Protocol #2011-17).

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

*Corresponding author:

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.May SM, Li JT. Burden of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: healthcare costs and beyond. Allergy Asthma Proc. 2015;36(1):4–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mortality GBD, Causes of Death C. Global, regional, and national life expectancy, all-cause mortality, and cause-specific mortality for 249 causes of death, 1980–2015: a systematic analysis for the global burden of Disease Study 2015. Lancet. 2016;388(10053):1459–544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rabe KF, Watz H. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Lancet. 2017;389(10082):1931–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Christenson SA, Smith BM, Bafadhel M, Putcha N. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Lancet. 2022;399(10342):2227–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ritchie AI, Wedzicha JA. Definition, causes, Pathogenesis, and consequences of Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease exacerbations. Clin Chest Med. 2020;41(3):421–38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Qian Y, Cai C, Sun M, Lv D, Zhao Y. Analyses of Factors Associated with Acute exacerbations of Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease: a review. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2023;18:2707–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fujimoto K, Yasuo M, Urushibata K, Hanaoka M, Koizumi T, Kubo K. Airway inflammation during stable and acutely exacerbated chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Eur Respir J. 2005;25(4):640–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Garudadri S, Woodruff PG. Targeting Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease Phenotypes, Endotypes, and biomarkers. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2018;15(Suppl 4):S234–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bagdonas E, Raudoniute J, Bruzauskaite I, Aldonyte R. Novel aspects of pathogenesis and regeneration mechanisms in COPD. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2015;10:995–1013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Andreassen H, Vestbo J. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease as a systemic disease: an epidemiological perspective. Eur Respir J Suppl. 2003;46:s2–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Riley CM, Sciurba FC. Diagnosis and Outpatient Management of Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease: a review. JAMA. 2019;321(8):786–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kaluzniak-Szymanowska A, Krzyminska-Siemaszko R, Deskur-Smielecka E, Lewandowicz M, Kaczmarek B, Wieczorowska-Tobis K. Malnutrition, Sarcopenia, and malnutrition-Sarcopenia Syndrome in older adults with COPD. Nutrients 2021;14(1). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 13.van Iersel LEJ, Beijers R, Gosker HR, Schols A. Nutrition as a modifiable factor in the onset and progression of pulmonary function impairment in COPD: a systematic review. Nutr Rev. 2022;80(6):1434–44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Paulose-Ram R, Graber JE, Woodwell D, Ahluwalia N. The National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES), 2021–2022: Adapting Data Collection in a COVID-19 environment. Am J Public Health. 2021;111(12):2149–56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Salvagno GL, Sanchis-Gomar F, Picanza A, Lippi G. Red blood cell distribution width: a simple parameter with multiple clinical applications. Crit Rev Clin Lab Sci. 2015;52(2):86–105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fest J, Ruiter TR, Groot Koerkamp B, Rizopoulos D, Ikram MA, van Eijck CHJ, Stricker BH. The neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio is associated with mortality in the general population: the Rotterdam Study. Eur J Epidemiol. 2019;34(5):463–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ning Y, Pan D, Guo J, Su Z, Wang J, Wu S, Gu Y. Association of prognostic nutritional index with the risk of all-cause mortality and cardiovascular mortality in patients with type 2 diabetes: NHANES 1999–2018. BMJ Open Diabetes Res Care 2023;11(5). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 18.Zhang ZL, Guo QQ, Tang JN, Zhang JC, Cheng MD, Song FH, Liu ZY, Wang K, Jiang LZ, Fan L et al. Monocyte-to-albumin ratio as a novel predictor of long-term adverse outcomes in patients after percutaneous coronary intervention. Biosci Rep 2021;41(7). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 19.Jian L, Zhang Z, Zhou Q, Duan X, Ge L. Red cell distribution Width/Albumin ratio: a predictor of In-Hospital all-cause mortality in patients with Acute myocardial infarction in the ICU. Int J Gen Med. 2023;16:745–56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Farag CM, Antar R, Akosman S, Ng M, Whalen MJ. What is hemoglobin, albumin, lymphocyte, platelet (HALP) score? A comprehensive literature review of HALP’s prognostic ability in different cancer types. Oncotarget. 2023;14:153–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tu J, Wu B, Xiu J, Deng J, Lin S, Lu J, Yan Y, Yu P, Zhu J, Chen K, et al. Advanced lung cancer inflammation index is associated with long-term cardiovascular death in hypertensive patients: national health and nutrition examination study, 1999–2018. Front Physiol. 2023;14:1074672. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Toren K, Murgia N, Olin AC, Hedner J, Brandberg J, Rosengren A, Bergstrom G. Validity of physician-diagnosed COPD in relation to spirometric definitions of COPD in a general population aged 50–64 years - the SCAPIS pilot study. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2017;12:2269–75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Qiu Z, Chen X, Geng T, Wan Z, Lu Q, Li L, Zhu K, Zhang X, Liu Y, Lin X, et al. Associations of serum carotenoids with risk of Cardiovascular Mortality among individuals with type 2 diabetes: results from NHANES. Diabetes Care. 2022;45(6):1453–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zhao H, Pan Y, Wang C, Guo Y, Yao N, Wang H, Li B. The effects of Metal exposures on Charlson Comorbidity Index using zero-inflated negative Binomial Regression Model: NHANES 2011–2016. Biol Trace Elem Res. 2021;199(6):2104–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kirkpatrick SI, Reedy J, Krebs-Smith SM, Pannucci TE, Subar AF, Wilson MM, Lerman JL, Tooze JA. Applications of the Healthy Eating Index for Surveillance, Epidemiology, and Intervention Research: considerations and caveats. J Acad Nutr Diet. 2018;118(9):1603–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kim CY, Sivasundaram L, LaBelle MW, Trivedi NN, Liu RW, Gillespie RJ. Predicting adverse events, length of stay, and discharge disposition following shoulder arthroplasty: a comparison of the Elixhauser Comorbidity measure and Charlson Comorbidity Index. J Shoulder Elb Surg. 2018;27(10):1748–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Okosun IS, Annor FB, Seale JP, Eriksen MP. Abdominal adiposity and family income-to-poverty ratio in American women. Obes Res Clin Pract. 2014;8(3):e201–298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Beddhu S, Baird BC, Zitterkoph J, Neilson J, Greene T. Physical activity and mortality in chronic kidney disease (NHANES III). Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2009;4(12):1901–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yoshikawa M, Fujita Y, Yamamoto Y, Yamauchi M, Tomoda K, Koyama N, Kimura H. Mini Nutritional Assessment Short-Form predicts exacerbation frequency in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Respirology. 2014;19(8):1198–203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Suzuki E, Kawata N, Shimada A, Sato H, Anazawa R, Suzuki M, Shiko Y, Yamamoto M, Ikari J, Tatsumi K, et al. Prognostic Nutritional Index (PNI) as a potential Prognostic Tool for Exacerbation of COPD in Elderly patients. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2023;18:1077–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Han H, Hu S, Du J. Predictive value of the hemoglobin-albumin-lymphocyte-platelet (HALP) index for ICU mortality in patients with acute exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (AECOPD). Intern Emerg Med. 2023;18(1):85–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zhao N, Hu W, Wu Z, Wu X, Li W, Wang Y, Zhao H. The red blood cell distribution width-albumin ratio: a promising predictor of Mortality in Stroke patients. Int J Gen Med. 2021;14:3737–47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tertemiz KC, Ozgen Alpaydin A, Sevinc C, Ellidokuz H, Acara AC, Cimrin A. Could red cell distribution width predict COPD severity? Rev Port Pneumol (2006). 2016;22(4):196–201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Seyhan EC, Ozgul MA, Tutar N, Omur I, Uysal A, Altin S. Red blood cell distribution and survival in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. COPD. 2013;10(4):416–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Epstein D, Nasser R, Mashiach T, Azzam ZS, Berger G. Increased red cell distribution width: a novel predictor of adverse outcome in patients hospitalized due to acute exacerbation of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Respir Med. 2018;136:1–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ycas JW, Horrow JC, Horne BD. Persistent increase in red cell size distribution width after acute diseases: a biomarker of hypoxemia? Clin Chim Acta. 2015;448:107–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Nicholson JP, Wolmarans MR, Park GR. The role of albumin in critical illness. Br J Anaesth. 2000;85(4):599–610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Magzal F, Sela S, Szuchman-Sapir A, Tamir S, Michelis R, Kristal B. In-vivo oxidized albumin- a pro-inflammatory agent in hypoalbuminemia. PLoS ONE. 2017;12(5):e0177799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gunen H, Hacievliyagil SS, Kosar F, Mutlu LC, Gulbas G, Pehlivan E, Sahin I, Kizkin O. Factors affecting survival of hospitalised patients with COPD. Eur Respir J. 2005;26(2):234–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Tokgoz Akyil F, Gunen H, Agca M, Gungor S, Yalcinsoy M, Sucu P, Akyil M, Sevim T. Patient outcome after Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease exacerbations requiring non-invasive ventilation during hospitalization. Arch Bronconeumol. 2016;52(9):470–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Yoo JW, Ju S, Lee SJ, Cho YJ, Lee JD, Kim HC. Red cell distribution width/albumin ratio is associated with 60-day mortality in patients with acute respiratory distress syndrome. Infect Dis (Lond). 2020;52(4):266–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Jeong JH, Heo M, Lee SJ, Jeong YY, Lee JD, Yoo JW. Clinical usefulness of red cell distribution Width/Albumin ratio to Discriminate 28-Day mortality in critically ill patients with Pneumonia receiving invasive mechanical ventilation, compared with Lacate/Albumin ratio: a retrospective cohort study. Diagnostics (Basel) 2021;11(12). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 43.Eraslan BZ, Cengiz SK, Sagmen SB, Yalcinkaya KZ, Kiral N, Comert S. The importance of the erythrocyte distribution width/albumin ratio in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease exacerbation. Saudi Med J. 2024;45(1):27–33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Qiu Y, Wang Y, Shen N, Wang Q, Chai L, Liu J, Chen Y, Li M. Association between Red Blood cell distribution width-albumin ratio and Hospital Mortality in Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease patients admitted to the Intensive Care Unit: a retrospective study. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2022;17:1797–809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Donaldson GC, Seemungal TA, Patel IS, Bhowmik A, Wilkinson TM, Hurst JR, Maccallum PK, Wedzicha JA. Airway and systemic inflammation and decline in lung function in patients with COPD. Chest. 2005;128(4):1995–2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hoffer LJ, Bistrian BR. Nutrition in critical illness: a current conundrum. F1000Res. 2016;5:2531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Mete B, Pehlivan E, Gulbas G, Gunen H. Prevalence of malnutrition in COPD and its relationship with the parameters related to disease severity. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2018;13:3307–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

NHANES data described in this manuscript are available at https://wwwn.cdc.gov/nchs/nhanes/..