Abstract

Background

Postoperative sore throat is a frequent and distressing complication caused by airway instrumentation during general anesthesia. The discomfort can lead to immediate distress, delayed recovery and reduce patient satisfaction. The objective of this study was to determine the effectiveness of preoperative ketamine gargle on the occurrence of postoperative sore throat among adult patients who underwent surgery under general anesthesia with endotracheal tube.

Method

PubMed, Cochrane Library, Google Scholar, and World Clinical Trial Registry were searched to find the eligible randomized control trials comparing the effect of preoperative ketamine gargle and placebo gargle on the occurrence of postoperative sore throat after surgery with endotracheal tube in adult patients. We utilized Review Manager Version 5.4 to perform statistical analyses. Cochrane risk of bias tool for randomized control trials was used to assess the risk of bias of included studies. We explored heterogeneity using the I2 test. In addition to this, subgroup analysis, and sensitivity analysis was conducted to confirm the robustness of findings. The risk of publication bias was tested using funnel plot Pooled risk ratio along with 95% confidence interval (CI) was used to analyze the outcome.

Result

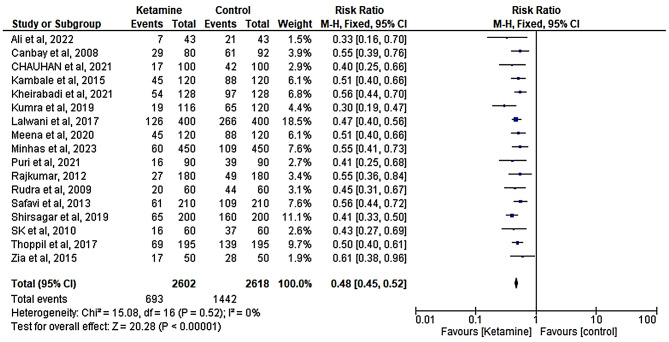

In the present systematic review and metanalysis, seventeen [17] randomized controlled trials (RCTs) with 1552 participants were included. Compared with placebo, preoperative ketamine gargle is effective to reduce postoperative sore throat (RR = 0.48; 95%CI [0.45, 0.52] in adult patients undergoing surgery under general anesthesia with endotracheal tube.

Conclusion

Preoperative ketamine gargle before induction of general anesthesia is effective to reduce the occurrence of postoperative sore throat in adult patients undergoing surgery under general anesthesia with an endotracheal tube. Further studies with large sample size, better study quality and optimal reporting could be conducted to determine the long-term efficacy and safety of ketamine gargle in different surgical populations.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s12871-024-02837-7.

Keywords: Postoperative sore throat, General anesthesia, Endotracheal tube, Ketamine gargle, Systematic review and metanalysis

Introduction

Postoperative sore throat (POST) refers to a combination of broad range of ailments that usually appear in the early postoperative phase. The clinical presentations include cough, hoarseness, dysphagia, pharyngitis, laryngitis, and tracheitis [1]. Postoperative sore throat is a frequent and distressing complication caused by airway instrumentation during general anesthesia [2]. A systematic review study stated that the prevalence of postoperative sore throat could reach up to 62% following general Anesthesia [3].

Study showed that postoperative sore throat (POST) could increase immediate distress and extends recovery periods, potentially leading to delayed resumption of normal activities. Various strategies have been explored to reduce the occurrence and severity of POST. The interventions include both pharmacological and non-pharmacological methods like modifications in intubation techniques. Use of small sized endotracheal tube [4], careful airway management [5], spraying the endotracheal tube cuff with lidocaine and beclomethasone [6], the use of muscle relaxant [7], adjusting endotracheal tube cuff pressure [8], benzydamine hydrochloride and aspirin gargles decreased the occurrence of POST [9]. However, a definitive solution that effectively addresses this issue while upholding patient safety and well-being remains an ongoing concern in perioperative medicine [10].

Ketamine is one of the most common N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) receptor antagonists that is a commonly used agent for anesthesia [11]. It is a newly proposed adjunct to manage postoperative pain during anesthesia [12]. Gargling is a simple and easy method with less time requirement and can be performed by most patients. Previous studies showed that ketamine gargle may reduce the incidence of postoperative sore throat but there is limited metanalysis. Therefore, this meta-analysis aims to generate comprehensive evidence regarding the effectiveness of preoperative ketamine gargle to reduce postoperative sore throat based on available randomized control trials. Our research question was, “in adult patients who underwent surgery under general anesthesia with an endotracheal tube, does preoperative ketamine gargle effective in reducing postoperative sore throat?”

Methods

Search strategies and selection criteria

We performed systematic research of medical literatures to identify, screen, and include Randomized Clinical Trials comparing the effect of preoperative ketamine gargle and placebo on postoperative sore throat. The search was conducted according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis (PRISMA) guidelines [13].We searched relevant RCT studies in PubMed, Cochrane Database of Clinical Trials, Google Scholar, and World Clinical Trial Registry from the inception to May 2024. The mentioned databases were searched using a combination of keywords; adult patients, surgery, general anesthesia, endotracheal tube, and postoperative sore throat. Assessment of the population, intervention, comparator, and outcomes was made based on population, intervention, comparison and outcome (PICO) questions and a literature search. The search was limited to RCT studies. In addition, reference lists of previous systematic review and met-analysis were cheeked.

Eligibility criteria

Inclusion criteria

Randomized controlled trials (RCTs) conducted on adults (≥ 18 years old) who underwent surgery under general anesthesia with an endotracheal tube were included. We accepted any time of application, and duration of application.

Exclusion criteria

Animal studies, all studies other than RCTs; RCT studies among patients underwent surgery with a laryngeal mask airway; RCT studies conducted among patients underwent surgery with double lumen tube; RCT studies that lack placebo as a comparator were excluded from this study.

Selection of included studies

Based on the above inclusion and exclusion criteria, two authors (MAT and FSk) reviewed articles title and abstract and excluded studies not related to the research question. Studies that meet the research question were read in detail to find the relevant information. Conflicts in the final inclusion of a study were resolved by discussion with a second author (AAA). Furthermore, the appropriate studies added after the two (MAT and FSK) authors reviewed references of the selected articles and other relevant articles.

Data extraction and retrieval

Two authors FSK and MAT independently collected the data from included studies. The authors independently extracted the number of patients developing postoperative sore throat among patients who take ketamine or placebo gargle. In addition, First author, year of publication, country, sample size, ASA classification, size of endotracheal tube, dose and volume of ketamine and placebo were extracted. Furthermore, time of application of the ketamine and placebo, duration of application of ketamine and placebo, surgical procedure, duration of surgery, and the conclusion of the study were collected.

Assessment of the quality of included studies

Two investigators (AAA and MAT) independently evaluated the quality of included RCTs by using the Cochrane Risk of Bias (RoB) 2 Tool [14]. A value of high, unclear, or low risk of bias were given to the following items; sequence generation, allocation concealment, blinding, incomplete outcome data, selective outcome reporting, and other sources of bias. The included trials were judged as ‘overall low risk of bias when all bias domains were judged as low risk of bias. Conversely, trials were judged as ‘overall high risk of bias when at list one domain has high risk of bias and some concerns when the trial is judged to raise some concerns in at least one domain [15]. We discussed and found ways to resolve differences. We assessed publication bias using funnel plot.

Assessment of postoperative sore throat (POST)

POST is a common complication following surgery, characterized by pain or discomfort, particularly within the first 24 h after airway procedures [16, 17]. Studies have assessed POST using the visual analogue scale (VAS) or numeric rating scale (NRS). In these studies, VAS scores were measured using a four-point scale starting from zero= “none” to three= “severe POST” or one= “none” to four= “sever POST” [10, 18–34]. NRS measured POST on 11-point scale, ranging from “0” (none) to “10” (worst) [35]. One study found that VAS scores of ≥ 1 were linked to hoarseness and dysphagia compared to those with VAS score = 0 [5]. Another study indicated that VAS scores of ≥ 1 were associated with decreased postoperative ambulation and reduce patient satisfaction [36]. Optimal symptom management is essential regardless of severity, as effective treatment can prevent pain escalation and chronicity [37], enhance health-related quality of life [38], improve sleep quality [39], decrease requirement of strong opioids [36], and lower hospital costs [36]. All studies included in this metanalysis used VAS or NRS scores of ≥ 1 to identify POST [10, 18–34]. Consequently, for this meta-analysis, we calculated the sum of mild, moderate, and severe cases from each included RCTs to diagnose POST [40].

Characteristics of included studies

We showed the study characteristics and predefined outcome data of the included RCTs using (Tables 1 and 2). In this meta-analysis, 17 RCT studies published between 2008 and 2023 with a sample size of 40 to 300 patients were included. All studies used a placebo as a comparator. To reduce heterogeneity between studies, we exclude one study, which were conducted among patients who underwent thoracic surgery under double lumen endotracheal tube [41]. In both the control and experimental group, 1552 patients were included across 17 RCTs. The rest 3668 contribute to calculate pooled relative risk. Most studies use preoperative ketamine gargle from 40 to 50 mg except one study which compares 50 mg ketamine and 100 mg ketamine with saline gargle [42]. Since the higher dose of preoperative ketamine, gargle may have different pharmacologic effect we exclude the findings of a study with 100 mg preoperative ketamine gargle. Most studies reported preoperative ketamine gargling or drinking water placebo gargle for 30 s 5 min before induction except [27, 28, 43]. Studies included in this meta-analysis have variable follow-up times starting from immediate postoperative, 1 h, 2 h, 4 h, 6 h, 8 h, 12 h, and 24 h. Generally, all studies [10, 18–34, 44] have a postoperative follow-up for 24 h. Due to failure to meet the inclusion criteria, only one study [44] reported missed data among patients in the ketamine group (Table 1).

Table 1.

Characteristics of included studies

| Serial number | Author/Year/Country | Age (Mean ± SD) (years) | ASA | ETT Size in cm | Ketamine gargle dose | Control | Sample Size | Time of application (minute) | Duration of application (seconds) | Surgical Procedure | Duration of surgery in minutes | Study conclusion | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| K | C | M | F | K | C | K | C | K | C | |||||||

| 1. | Ali, [43], Pakistan | 38.58 ± 7.57 | 38.21 ± 7.33 | I, II | 8.5 | 7.5 | 50mg in 29ml drink water | 30ml drink water | 43 | 43 | No | 40 |

Abdominal or pelvic surgery |

62.81 ± 12.75 | 61.58 ± 12.2 | Ketamine gargle is effective in prevention of POST |

| 2. | Canbay, [44], Turky | 25.6 (19–38) | 23.6 (18–30) | I, II | 8–9 | 7–8 | 40mg in 30ml saline | saline 30ml | 23 | 23 | 5 | 30 | Septorhinoplasty | 55.8 (14.8) | 54.1 ± 14.4 | Ketamine gargle reduced the occurrence and severity of POST. |

| 3. | Chauhan, [18], India | 32.76 ± 8.24 | 32.72 ± 9.43 | I, II | 8-8.5 | 7-7.5 | K: 50mg in 29ml saline | 30ml saline | 25 | 25 | 5 | 30 | Elective surgery | 90 | 90 | Ketamine gargles is effective in attenuating POST, cough and HOV. |

| 4. | Kamble, [19], India | 31.07 ± 7.168 | 32.03 ± 7.015 | I, II | 8.5 | 7 | 50mg in 30ml saline | 30ml saline | 30 | 30 | 5 | 30 | Abdominal or pelvic surgery | 121.3 ± 26.09 | 124.4 ± 26.5 | Preoperative ketamine gargling is effective in reducing the occurrence and severity of POST. |

| 5. | Kheirabadi et al, [21], Iran | 35.12 ± 12.26 | 32.84 ± 13.50 | I, III | 8 | 7 | 50mg in 29ml saline | 30ml saline | 32 | 32 | 5 | 30 | Septoplasty | No | No | Ketamine gargle 5 min before tracheal intubation can reduce the severity and occurrence of POST. |

| 6. | Kumar, [22], India | 38.93 | 37.67 | I, II | 8 | 7 | 40mg in 24ml saline | 25ml saline | 29 | 30 | 5 | 30 | Elective abdominal surgery | No | No | Ketamine gargle significantly reduces the occurrence and severity of POST. |

| 7. | Lalwani, [23], India | 32.74+/-8.68 | 35.62+/-8.71 | I, II | 8-8.5 | 7-7.5 | 50mg in 29ml saline | 30ml saline | 100 | 100 | 5 | 30 | Elective surgery | 114.4+/-29.9 | 147.7+/-31.5 | Gargling with ketamine decreases the occurrence and severity of POST,HOV and cough. |

| 8. | Meena, [45] India | 54.1 ± 13.5 | 36.7 ± 12.5 | I, II | 8-8.5 | 7-7.5 | 40mg in 30ml saline | 30ml saline | 30 | 30 | 5 | 30 | Elective surgery | 71.4 ± 27 | 68.8 ± 25.9 | Ketamine gargle significantly attenuated POST. |

Hint: ASA: American society of Anesthesiologist, C: Control, ETT: Endotracheal Tube, K: ketamine, F: Female, M: Male, POST: Post-operative Sore Throat, HOV: Hoarseness of Voice

Table 2.

Characteristics of included studies

| Serial number | Author/Year/ Country | Age (Mean ± SD) years | ASA | ETT Size | Ketamine gargle | Placebo gargle | Sample size | Time of application (minutes) | Duration of application (seconds) | Surgical procedure | Duration of surgery (minutes) | Study conclusion | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| K | C | M | F | K | C | K | C | |||||||||

| 9. | Minhas, [10], India | 45.6 ± 7.2 | 46.2 ± 7.5 | I-III | No | No | 50 mg in 10 ml saline | 10 ml saline | 150 | 150 | 5 | 30 | Elective surgery | No | No | Ketamine gargle effectively reduced the occurrence and severity of POST, improved analgesic consumption, recovery time, and patient satisfaction. |

| 10. | Puri, [25], India | No | No | I, II | 7 | 8 | 40 mg in 29 ml saline | 30 ml saline | 30 | 30 | No | No | Elective ear surgery | No | No | Ketamine gargle effectively attenuate POST. |

| 11. | Rajkumar, [34], India | 42.31 ± 12.5 | 41.80 ± 13 | I, II | 7.5–8.5 | 7–8 | 40 mg in 30 ml saline | 30 ml saline | 45 | 45 | 5 | 30 | Cholecystectomy | 51.91 ± 17.2 | 49.64 ± 11.4 | Preoperative ketamine gargle reduce the incidence and severity of POST. |

| 12. | Rudra, [27], India | 37.5 ± 12.5 | 36.7 ± 12.3 | I, II | 8.5 | 7.5 | 50 mg in 29 ml saline | 30 ml saline | 20 | 20 | 5 | 40 | Elective surgery | 85.1 ± 19.0 | 86.6 ± 14.7 | Ketamine gargles is effective in prevention of POST. |

| 13. | Safavi, [32], Iran | 33.5 ± 13.4 | 34.5 ± 13.4 | I, II | 7–8 | 7–8 | 40 mg in 30 ml saline | 30 ml saline | 35 | 35 | 5 | 30 | Elective surgery | 60–300 | 60–300 | Ketamine was effective to reduce the occurrence and severity of POST and hoarseness of voice. |

| 14. | Shirsagar, [28], India | No | No | I, II | No | No | 50 mg in 30 ml saline | 30 ml saline | 50 | 50 | 5 | 30 | Elective surgery | No | No | Preoperative gargling of ketamine prior to 5–10 min of induction attenuates occurrence of POST. |

| 15. | SK, [25], Nepal | 36.8 ± 12.3 | 32.9 ± 7.7 | I, II | No | No | 50 mg in 30 ml saline | 30 ml saline | 20 | 20 | 5 | 30 | Abdominal or orthopedic surgery | 2.1 ± 0.6 | 2.4 ± 0.6 | Gargling ketamine decreases the occurrence and severity of POST. |

| 16. | Thoppil, [30], India | No | No | I, II | 8-8.5 | 7-7.5 | 50 mg in 29 ml saline | 30 ml saline | 65 | 65 | 5 | 30 | Elective surgery | 180 | 180 | Gargling ketamine five minutes prior to induction reduces POST. |

| 17. | Zia, [31], India | 31.54 ± 8.15 | 29.74 ± 8.40 | I | 7-7.5 | 7-7.5 | 50 mg in 29 ml saline | 30 ml saline | 50 | 50 | 5 | 30 | Septoplasty | No | No | Ketamine gargle 5 min before induction decrease POST. |

Hint: ASA: American society of Anesthesiologist, C: Control, ETT: Endotracheal Tube, K: ketamine, F: Female, M: Male, POST: Post-operative Sore Throat, HOV: Hoarseness of Voice

Statistical methods

Revman version 5.4 was used to conduct statistical analysis. Some studies reported the overall prevalence of POST [20, 24, 26, 42, 46, 47]. Other studies did not report the overall prevalence of POST and therefore we computed pooled prevalence for each study. We used pooled relative risk (RR) for treatment effect of dichotomous outcomes at 95% confidence interval (CI). Higgins’ I-squared (I²) was used (considering I2 values as follows: (low: <25%, moderate: 25–50%, or high: >50%) for assessment of study heterogeneity [48]. The fixed effect model was used since Higgins’ I-squared (I²) is 0%. Subgroup analysis were conducted to explore the robustness and the factors of postoperative sore throat. Since some studies did not reporte duration of intubation and duration of surgery separately we used mean duration of surgery or mean duration of intubation (less than 90 min and 90 min and above) for subgroup analysis. Other variables for subgroup analysis include the dose of ketamine (40mg or 50 mg), and type of blinding (single-blind or double-blind clinical trial). Further sensitivity analyses were performed by sequentially removing data from the final model. To assess for the potential of publication bias we used funnel plot. P value < 0.05 were considered statistically significant in all cases.

Results

Bibliographic search results are shown in the PRISMA diagram [13]. The initial search identified 658 articles: Among the identified studies, we removed 637 articles based on reviews of title and abstract. The reason for exclusion include research titles that are not in line with our study, wrong study designs and language barrier. After retrieval, we exclude duplicate studies. We reviewed 15 studies for eligibility and one study were excluded since the study was conducted among patients with double lumen endotracheal tube (DLT). In addition to this, we looked the references listed in other studies and included three RCT studies. Finally, 17 RCT studies were selected for a review and all studies were included in this meta-analysis (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Selection process for randomized controlled trials (RCTs) included in the meta-analysis. Hint: DLT: Double Lumen Tube, LMA = Laryngeal Mask Airway

Qualities of included studies

Nine studies has a concern about bias where six studies were evaluated as high risk. Studies from high to low risk of bias were included in this meta-analysis to provide comprehensive evidence. We presented the details on the risk of bias assessment in (Fig. 7).

Fig. 7.

The risk of bias assessment of the included studies

Publication bias

The funnel plot demonstrate the absence of significant publication bias for the effect of preoperative ketamine gargle to reduce the occurrence of postoperative sore throat [Fig. 2].

Fig. 2.

Funnel plot of postoperative sore throat

Outcomes

Occurrence of postoperative sore throat

This meta-analysis revealed that preoperative ketamine gargle is effective in reducing the occurrence of postoperative sore throat (RR; 0.48, 95% CI, (0.45 to 0.52); I2 = 0%; P < 0.001 (Fig. 3). Even though there is no heterogeneity between studies, we conducted subgroup analysis across predefined key clinical factors and study characteristics. In addition, we conducted a sensitivity analysis. In general, all the subgroup analyses and sensitivity analyses confirmed the absence of significant variation of the effect estimate (See Table 3).

Fig. 3.

Forest plot showing the effect of preoperative ketamine gargle on post-operative sore throat. Hint: M-H: Mantel-Haenszel, RR: Risk Ratio, CI: Confidence Interval

Table 3.

Sensitivity analysis of RCT studies on preoperative ketamine gargle and POST

| Omitted study | Ketamine | Control | RR(95%CI) | I2 | P | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Event | Total | Event | Total | ||||

| Ali et al., [43] | 7 | 43 | 21 | 43 | 0.49(0.45, 0.52) | 0% | < 0.001 |

| Canbay et al., [44] | 29 | 80 | 61 | 92 | 0.48(0.45, 0.52) | 0% | < 0.001 |

| Chauhan et al., [18] | 17 | 100 | 42 | 100 | 0.49(0.45, 0.52) | 0% | < 0.001 |

| Kamble et al., [19] | 45 | 120 | 88 | 120 | 0.48(0.46, 0.52) | 0% | < 0.001 |

| Kheirabadi et al., [21] | 54 | 128 | 97 | 128 | 0.48(0.44,0.52) | 0% | < 0.001 |

| Kumara et al., [22] | 19 | 116 | 65 | 120 | 0.49(0.46, 0.53) | 0% | < 0.001 |

| Lawani et al., [23] | 126 | 400 | 266 | 400 | 0.49(0.45, 0.53) | 0% | < 0.001 |

| Meena et al., [45] | 40 | 120 | 79 | 120 | 0.48(0.45, 0.52) | 0% | < 0.001 |

| Minhas et al., [10] | 60 | 450 | 109 | 450 | 0.48(0.45, 0.51) | 0% | < 0.001 |

| Puri et al., [25] | 16 | 90 | 39 | 90 | 0.49(0.49, 0.52) | 0% | < 0.001 |

| Rajkumar et al., [34] | 27 | 180 | 49 | 180 | 0.48(0.45,0.52) | 0% | < 0.001 |

| Rudra et al., [27] | 20 | 60 | 44 | 60 | 0.49(0.46, 0.53) | 0% | < 0.001 |

| Safavi et al., [32] | 61 | 210 | 109 | 210 | 0.48(0.44, 0.52) | 0% | < 0.001 |

| Shirsagar et al., [28] | 65 | 200 | 160 | 200 | 0.49(0.46, 0.53) | 0% | < 0.001 |

| SK et al., [29] | 16 | 60 | 37 | 60 | 0.49(0.45, 0.52) | 0% | < 0.001 |

| Thoppil et al., [30] | 69 | 195 | 139 | 195 | 0.48(0.45, 0.52) | 1% | < 0.001 |

| Zia et al., [31] | 17 | 50 | 28 | 50 | 0.48(0.45, 0.52) | 0% | < 0.001 |

Subgroup analysis

We conducted subgroup analysis by considering the dose of preoperative ketamine gargle (40 mg vs. 50 mg), mean duration of intubation or surgery (< 90 min vs. ≥ 90 min) and method of blinding (single blind vs. double blind). The subgroup analysis confirmed the absence of significant change of the effect estimate (Figs. 4, 5 and 6).

Fig. 4.

Subgroup analysis for 40 mg and 50 mg preoperative ketamine gargle on postoperative sore throat. Hint: M-H: Mantel-Haenszel, RR: Risk Ratio, CI: Confidence Interval

Fig. 5.

Duration of intubation or duration of surgery on postoperative sore throat

Fig. 6.

Subgroup by type of blinding and Postoperative sore throat. Hint: M-H: Mantel-Haenszel, RR: Risk Ratio, CI: Confidence Interval

Sensitivity analysis

The sensitivity analysis assessed the impact of individual studies on the overall effect of preoperative ketamine gargle in reducing postoperative sore throat. The results were summarized using the relative risk (RR) and 95% confidence intervals (CI) for each study, along with the I² statistic and p-values.

Discussion

This meta-analysis was conducted to compare the effectiveness of preoperative ketamine gargle and preoperative placebo gargle to reduce the occurrence of postoperative sore throats in adult patients undergoing surgery under general anesthesia with endotracheal intubation. In this study, preoperative ketamine gargle is found to reduce the occurrence of postoperative sore throat compared to placebo (saline or drink water) gargle. The finding of this metanalysis is supported by another meta-analysis of RCT studies (RR = 0.53 and p < 0.015) [49]. Compared to this metanalysis, the previous metanalysis include five RCT studies and small sample size for analysis. In addition, to this, the robustness of findings were not confirmed by advanced statistical tests (test of heterogeneity, subgroup analysis and sensitivity analysis) [49].

Moreover, RCT study conclude that the onset of POST after extubation was significantly longer for patients in ketamine gargling compared to patients in lidocaine jelly [50]. This may be explained by the mechanism of action of ketamine, which has both central nervous system (block of N-methyl-D-aspartate receptors (NMDA)) and peripheral nervous system (block ion channels and receptors, modulate transporters and anti-inflammatory action) actions to produce analgesic [51] compared to a local [52] effect of lidocaine jelly.

Studies also stated that other formulation of ketamine are effective to reduce postoperative sore throat. A network metanalysis stated that nebulized magnesium, corticosteroids and ketamine are effective to reduce postoperative sore throat but corticosteroids are superior to magnesium and ketamine [53]. Another network metanalysis study stated that the use of topical pharmacologic agents including magnesium, ketamine, corticosteroids and non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs are more effective to reduce POST compared to lidocaine [40].

On the other hand another RCT study stated that the incidence of postoperative sore throat in preoperative ketamine gargle is higher compared to preoperative magnesium gargle [54]. This may be explained by the muscle relaxant effect of magnesium [55]. Similarly, a double blind RCT study stated that prophylaxis intravenous combination use of dexamethasone and ketamine gargle significantly reduce postoperative sore throat compared to using ketamine gargle alone [56]. This may be attributed to blockade of additional pain pathways (inhibition of peripheral phospholipase) by dexamethasone which ketamine does not address [57]. Another single blind RCT conclude that nebulized ketamine is more effective to reduce the incidence and severity of POST compared to ketamine gargle [58]. This may be explained by nebulized ketamine can reach deeper into the airway has more efficient absorption to the blood stream compared to ketamine gargle [59].

Conclusion

Administration of preoperative 40-50 mg ketamine gargle before induction of anesthesia reduce the occurrence of postoperative sore throat among adult patients undergoing various surgery under general anesthesia with an endotracheal tube.

Strengths and limitations of the study

The major strengths of this study include comprehensive and adherence to PRISMA guideline for reporting of systematic review and metanalysis [13]. In addition to this, the current study incorporate 17 RCT studies, which is larger than a similar previous study conducted, by incorporating five RCT studies. To enhance the generalizability of the study, we include RCT studies conducted among adult patients undergoing different types of surgery. This study has the following limitations. First majority of the included RCT studies did not report the incidence of new cases at each observation; as a result, we did not report the effectiveness of preoperative ketamine gargle to reduce the severity of POST. Second, most of included RCT studies did not report adverse events associated with preoperative ketamine gargle as a result this metanalysis did not address the safety of preoperative ketamine gargle. Third, the result of this metanalysis was not based on adjusted estimates; results that are more accurate would be obtained from adjustment of the following confounders, age, gender, BMI, the size of endotracheal tube, the duration of intubation, the duration of surgery and the type of surgery. The finding of our study is limited by the quality of included studies by which nine out of seventeen included studies has a concern of bias out of which six has high risk of bias.

Recommendation

Based on available evidences, the present systematic review and meta-analysis comprehensively assessed the effectiveness of preoperative ketamine gargle to reduce POST in adult patients undergoing surgery with endotracheal intubation. These evidences showed that 40-50 mg of preoperative ketamine gargle have been found effective to prevent postoperative sore throat. Further studies with large sample size, better study quality and optimal reporting could be conducted to determine the long-term efficacy and safety of ketamine gargle in different surgical population.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Abbreviations

- POST

Post-operative sore throat

- RR

Relative risk

- CI

Confidence interval

- RCT

Randomized controlled trials

- PRISMA

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review and Meta-analysis

Author contributions

MAT conceived the study, extracted the data, performed statistical analyses, and drafted the manuscript. AAA and FSK extracted the data. EA, LM and DO have reviewed the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

The authors declare that they have no funding for this research.

Data availability

The data generated and analyzed for this study can be found in the databases were individual articles were searched and can be submitted by the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

It is not applicable for this study.

Research registration

The metanalysis was registered with registration number (reviewregistry1836).

Consent for publication

It is not applicable for this study.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Mazzotta E, Soghomonyan S, Hu L-Q. Postoperative sore throat: prophylaxis and treatment. Front Pharmacol. 2023;14:1284071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lehmann M, Monte K, Barach P, Kindler CH. Postoperative patient complaints: a prospective interview study of 12,276 patients. J Clin Anesth. 2010;22(1):13–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.El-Boghdadly K, Bailey CR, Wiles MD. Postoperative sore throat: a systematic review. Anaesthesia. 2016;71(6):706–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Maria Jaensson R, Anil Gupta M. Risk factors for development of postoperative sore throat and hoarseness after endotracheal intubation in women: a secondary analysis. AANA J. 2012;80(4):S67. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Piriyapatsom A, Dej-Arkom S, Chinachoti T, Rakkarnngan J, Srishewachart P. Postoperative sore throat: incidence, risk factors, and outcome. J Med Assoc Thai. 2013;96(8):936–42. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Banihashem N, Alijanpour E, Hasannasab B, Zarei A. Prophylactic effects of Lidocaine or Beclomethasone Spray on Post-operative Sore Throat and Cough after Orotracheal Intubation. Iran J Otorhinolaryngol. 2015;27(80):179–84. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wang Y, Xu C, Zhao H, Liang T, Liu S, Qiu J et al. Effect of intraoperative use of muscle relaxants on postoperative pharyngeal discomfort after intubation anesthesia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. 2023.

- 8.Ganason N, Sivanaser V, Liu CY, Maaya M, Ooi JSM. Post-operative Sore Throat: comparing the Monitored Endotracheal Tube Cuff pressure and pilot balloon palpation methods. Malays J Med Sci. 2019;26(5):132–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jaensson M, Olowsson LL, Nilsson U. Endotracheal tube size and sore throat following surgery: a randomized-controlled study. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 2010;54(2):147–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Minhas HSBM, Rastogi B, Bharti E. Efficacy of ketamine gargle in prevention of postoperative sore throat in patients undergoing general anaesthesia-a one year double blind randomized control study. J Cardiovasc Disease Res. 2023;14(8):1501–8. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zorumski CF, Izumi Y, Mennerick S. Ketamine: NMDA receptors and beyond. J Neurosci. 2016;36(44):11158–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zanos P, Gould T. Mechanisms of ketamine action as an antidepressant. Mol Psychiatry. 2018;23(4):801–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, Boutron I, Hoffmann TC, Mulrow CD et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ. 2021;372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 14.Minozzi S, Cinquini M, Gianola S, Gonzalez-Lorenzo M, Banzi R. The revised Cochrane risk of bias tool for randomized trials (RoB 2) showed low interrater reliability and challenges in its application. J Clin Epidemiol. 2020;126:37–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Higgins JP, Savović J, Page MJ, Elbers RG, Sterne JA. Assessing risk of bias in a randomized trial. Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions. 2019:205 – 28.

- 16.Calder A, Hegarty M, Erb TO, von Ungern-Sternberg BS. Predictors of postoperative sore throat in intubated children. Pediatr Anesth. 2012;22(3):239–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.SHARMA A, SINGH M, Rajitha J. Comparison of incidence of postoperative Sore Throat after Nebulisation with ketamine, Lignocaine and Magnesium Sulphate-A Randomised Controlled Trial. J Clin Diagn Res. 2020;14(6).

- 18.Chauhan D, Mankad A, Mehta J, Sharma TH. Effects of ketamine gargle for post-operative sore throat, hoarseness of voice and cough under general anaesthesia-a randomised control study. J Clin Diagn Res. 2021;15(6):UC05–8. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kamble NP, Gajbhare MN. Efficacy of ketamine gargles in the prevalence of postoperative Sore Throat after Endotracheal Intubation. Indian J Clin Anaesth. 2015;2(4):251. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kang HY, Seo DY, Choi JH, Park SW, Kang WJ. Preventive effect of ketamine gargling for postoperative sore throat after endotracheal intubation. Anesthesiology pain Med. 2015;10(4):257–60. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kheirabadi D, Ardekani MS, Honarmand A, Safavi MR, Salmasi E. Comparison Prophylactic effects of Gargling different doses of ketamine on attenuating postoperative Sore Throat: a single-blind randomized controlled trial. Int J Prev Med. 2021;12(1):62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kumar A, Panigrahy S, Routray D. An evaluation of the Efficacy of Ketamine Gargle and Benzydamine Hydrochloride Gargle for Attenuating Post Operative Sore Throat: a prospective Randomized, Placebo Controlled single-blind study. 2019.

- 23.Lalwani J, Thakur R, Tandon M, Bhagat S. To study the effect of ketamine gargle for attenuating post operative sore throat, cough and hoarseness of voice. J Anesth Intensive Care Med. 2017;4(4).

- 24.Muralikrishnan U, Susha T. Efficacy of ketamine gargle for attenuating post-operative sore throat in patient undergoing general anaesthesia with endotracheal intubation. Indian J Anesth Analg. 2017;4:1215–22. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Puri A, Ghosh SK, Singh G, Madan A. Gargling with ketamine preoperatively decreases postoperative sore throat after endotracheal intubation in middle ear surgeries: a prospective randomized control study. Indian J Otolaryngol head neck Surg. 2022;74(Suppl 3):5739–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rabbani MW, Yousaf M. Bushra. Comparison of Ketamine Gargles with Placebo for reducing Postoperative Sore throat. PAKISTAN JOURNAL OF MEDICAL & HEALTH SCIENCES. 2015;9(2):748 – 51.

- 27.Rudra A, Ray S, Chatterjee S, Ahmed A, Ghosh S. Gargling with ketamine attenuates the postoperative sore throat. Indian J Anaesth. 2009;53(1):40–3. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Shirsagar HK, Deshpande SG. Postoperative Sore Throat (POST): efficacy of ketamine gargling for attenuation. Indian J Anesth Analg. 2019;6(2):482–7. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Shrestha SK, Bhattarai B, Singh J. Ketamine gargling and postoperative sore throat. J Nepal Med Association. 2010;50(180). [PubMed]

- 30.Thoppil JV, Imanual SR. Efficacy of ketamine gargle for attenuating postoperative sore throat in patients undergoing general anaesthesia with endotracheal intubation. J Evol Med Dent Sci. 2017;6(81):5707–12. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zia MA, Sheikh F, Kazmi SR. The effect of preoperative ketamine gargles on postoperative sore throat after oral endotracheal intubation. Pakistan J Med Health Sci. 2015;9(1):371–4. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Safavi SM, Honarm A, Fariborzifar A, Barvarz S, Soleimani M. Intravenous dexamethasone vs. ketamine gargle vs. intravenous dexamethasone combined with ketamine gargle for evaluation of post-operative sore throat and hoarseness: a randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blind clinical trial. J Isfahan Med School. 2013;31(242):933–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Jagadish M. Gargling with ketamine attenuates post-operative sore Throat. J Evol Med Dent Sci. 2014;3(62):13632–7. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rajkumar G, Eshwori L, Konyak PY, Singh LD, Singh TR, Rani MB. Prophylactic ketamine gargle to reduce post-operative sore throat following endotracheal intubation. J Med Soc. 2012;26(3):175–9. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Agarwal A, Nath SS, Goswami D, Gupta D, Dhiraaj S, Singh PK. An evaluation of the efficacy of aspirin and benzydamine hydrochloride gargle for attenuating postoperative sore throat: a prospective, randomized, single-blind study. Anesth Analgesia. 2006;103(4):1001–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Liu Y, Xiao S, Yang H, Lv X, Hou A, Ma Y. Postoperative pain-related outcomes and perioperative pain management in China: a population-based study. Lancet Reg Health-West Pac [Internet]. junio de 2023 [citado 29 de agosto de 2023]; 100822. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 37.Liu Y, Xiao S, Yang H, Lv X, Hou A, Ma Y, et al. Postoperative pain-related outcomes and perioperative pain management in China: a population-based study. Lancet Reg Health West Pac. 2023;39:100822. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ludwig H, Bailey AL, Marongiu A, Khela K, Milligan G, Carlson KB, et al. Patient-reported pain severity and health-related quality of life in patients with multiple myeloma in real world clinical practice. Cancer Rep (Hoboken). 2022;5(1):e1429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gerhart JI, Burns JW, Post KM, Smith DA, Porter LS, Burgess HJ, et al. Relationships between Sleep Quality and Pain-related factors for people with chronic low back Pain: tests of reciprocal and time of Day effects. Ann Behav Med. 2017;51(3):365–75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wang G, Qi Y, Wu L, Jiang G. Comparative efficacy of 6 topical pharmacological agents for preventive interventions of postoperative Sore Throat after Tracheal Intubation: a systematic review and network Meta-analysis. Anesth Analgesia. 2021;133(1):58–67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Liang J, Liu J, Qiu Z, Sun G, Xiang P, Hei Z et al. Effect of Esketamine Gargle on Postoperative Sore Throat in Patients Undergoing Double-Lumen Endobronchial Intubation: A Randomised Controlled Trial. Drug Design, Development and Therapy. 2023:3139-49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 42.Kheirabadi D, Ardekani MS, Honarmand A, Safavi MR, Salmasi E. Comparison Prophylactic effects of Gargling different doses of ketamine on attenuating postoperative Sore Throat: a single-blind randomized controlled trial. Int J Prev Med. 2021;12:62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ali A, Ahmed I, Ali K, Raza MH, Mahmood Z, Aftab A. Effectiveness of ketamine gargles in Prevention of Post-operative Sore Throat in patients undergoing endotracheal intubation. Pakistan J Med Health Sci. 2022;16(2):343–5. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Canbay O, Celebi N, Sahin A, Celiker V, Ozgen S, Aypar U. Ketamine gargle for attenuating postoperative sore throat. Br J Anaesthesia: BJA. 2008;100(4):490–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Meena K, Lalaram, Choudhary S, Sharma S, Gaekwad J, Kumari I. Evaluation of prophylactic ketamine gargle for the attenuation of postoperative sore throat following general anaesthesia with orotracheal intubation: a prospective randomized control study. Int J Anesthesiol Sci. 2020;2:11–15.

- 46.Ali A, Ahmed I, Ali K, Raza MH, Mahmood Z, Aftab A. Effectiveness of ketamine gargles in Prevention of Post-operative Sore Throat in patients undergoing endotracheal intubation. Pakistan J Med Health Sci. 2022;16(02):343. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Zia MA, Sheikh F, Kazmi SR, Shah SM, Ashraf R. The effect of preoperative ketamine gargles on postoperative sore throat after oral endotracheal intubation. Pakistan J Med Health Sci. 2015;9(1):371–4. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Patsopoulos NA, Evangelou E, Ioannidis JP. Sensitivity of between-study heterogeneity in meta-analysis: proposed metrics and empirical evaluation. Int J Epidemiol. 2008;37(5):1148–57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Mayhood J, Cress K. Effectiveness of ketamine gargle in reducing postoperative sore throat in patients undergoing airway instrumentation: a systematic review. JBI Database Syst Rev Implement Rep. 2015;13(9):244–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Aigbedia S, Tobi K, Amadasun F. A comparative study of ketamine gargle and lidocaine jelly application for the prevention of postoperative throat pain following general anaesthesia with endotracheal intubation. Niger J Clin Pract. 2017;20(6):677–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Sawynok J. Topical and peripheral ketamine as an analgesic. Anesth Analg. 2014;119(1):170–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Prasant NVSN, Mohapatro S, Jena J, Moda N. Comparison of preoperative nebulization with 4% lignocaine and ketamine in reduction of incidence of postoperative Sore Throat. Anesth Essays Researches. 2021;15(3):316–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Yu J, Ren L, Min S, Yang Y, Lv F. Nebulized pharmacological agents for preventing postoperative sore throat: a systematic review and network meta-analysis. PLoS ONE. 2020;15:e0237174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Arianto AT, Santosa SB, Anindita A. Comparison of Magnesium Sulfat Gargle and Ketamine Gargle on the incidence of Sore Throat and Cough after Extubation. Solo J Anesthesi Pain Crit Care (SOJA). 2022;2(1):23–30. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Dahake JS, Verma N, Bawiskar D. Magnesium sulfate and its versatility in Anesthesia: a Comprehensive Review. Cureus. 2024;16(3):e56348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Safavi M, Honarmand A, Fariborzifar A, Attari M. Intravenous dexamethasone versus ketamine gargle versus intravenous dexamethasone combined with ketamine gargle for evaluation of post-operative sore throat and hoarseness: a randomized, placebo-controlled, double blind clinical trial. Adv Biomedical Res. 2014;3(1):212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Mohtadi A, Nesioonpour S, Salari A, Akhondzadeh R, Masood Rad B, Aslani SM. The effect of single-dose administration of dexamethasone on postoperative pain in patients undergoing laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Anesth Pain Med. 2014;4(3):e17872. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Khan A, Taqi M, Alam A. Comparison of ketamine nebulisation with ketamine gargle in attenuating postoperative sore throat. Med J South Punjab. 2024;5(01):102–7. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Modak A, Rasheed E, Bhalerao N, Devulkar P. Comparison of ketamine nebulisation with ketamine gargle in attenuating Post Operative Sore Throat following General Anaesthesia with Endotracheal Intubation. J Pharm Res Int. 2021;33(52B):129–36. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data generated and analyzed for this study can be found in the databases were individual articles were searched and can be submitted by the corresponding author on reasonable request.