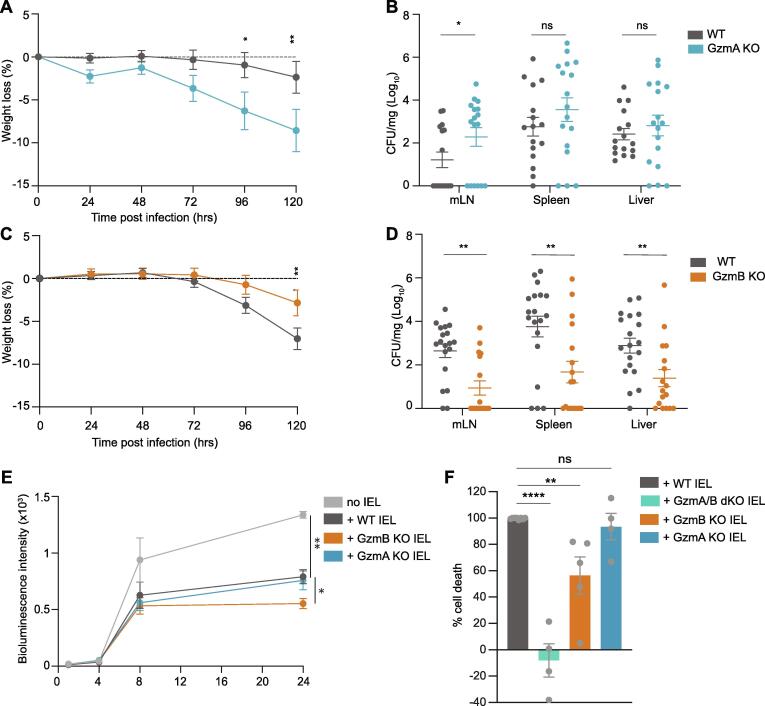

Fig. 4.

Divergent roles of GzmA and GzmB in intestinal infection. A-B. GzmA KO mice (n = 18) and their WT littermate controls (n = 19) were orally infected with SL1344-GFP and culled 5dpi. Weight loss (A) and CFU/mg in mLN, spleen and liver (B) are shown. Data were pooled from 2 independent experiments. C-D. GzmB KO mice (n = 17) and their littermate WT controls (n = 19) were orally infected with SL1344-GFP and culled 5dpi. Weight loss (C) and CFU/mg in mLN, spleen and liver (D) are displayed. Data were pooled from 2 independent experiments. E. MODE-K cells were infected with SL1334-lux for 1 h and then incubated with GzmA or GzmB KO or their WT littermate control IEL (n = 3). Bioluminescence intensity was measured when IEL were added, then after 4 h, 8 h and 24 h. F. Infected MODE-K cells were stained with Crystal violet 24 h after incubation with IEL from WT (n = 8), GzmA/B dKO (n = 4), GzmB KO (n = 5), GzmA KO (n = 4) mice, pooled from 5 independent experiments. The percentage cell death relative to infected MODE-K cells without IEL was normalized to the cell death induced by WT IEL. All data are presented as mean ± SEM. P values were calculated for bacterial counts (B, D) using Mann-Whitney U test to compare ranks, and for all other comparisons, two-way ANOVA was used, with Sidak’s multiple comparisons tests. ns: not significant, * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001, **** p < 0.0001. (For interpretation of the references to colour in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the web version of this article.)