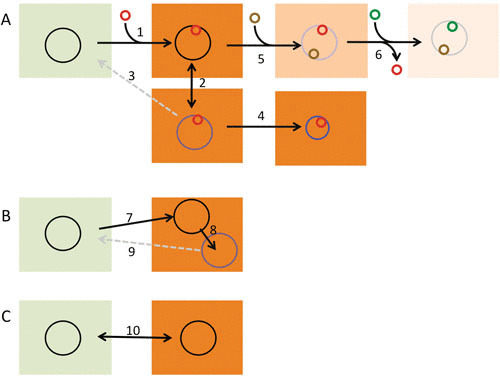

FIGURE 1.

Evolutionary trajectories of bacterial pathogens. (A) The process of speciation of a pathogen (larger circles) such as Y. pestis. This process usually begins with the acquisition, by HGT, of a set of genes (red circle) that allow the shift of the pathogen’s habitat from the environment to an infected host (1). If the rate of transmission is high enough, the newborn pathogen will disseminate among different individuals (2) and evolve by different mechanisms that include mutation and eventually genome reduction (4). These evolutionary processes might cause the deadaptation of the pathogen to its original habitat, in which case the chances of the microorganism recolonizing natural ecosystems will be low (3). Once the organism is a pathogen, it can change host specificity by acquiring novel genes (5) and eventually by losing of determinants unneeded in the novel host (6). In all cases, the integration of the acquired elements into the preformed bacterial metabolic and regulatory networks will be tuned by mutation. (B) The process of short-sighted evolution of opportunistic pathogens with an environmental origin, like P. aeruginosa. These microorganisms infect patients, presenting a basal disease, using virulence determinants already encoded in their genomes (7). During chronic infection, the infective strain evolves mainly by mutation and genome rearrangements (8). However, since it only infects people with a basal disease, transmission rates are usually low, which precludes clonal expansion and further diversification. Since adaptation to the new host is of no value for colonizing the environmental habitat (9), this is a dead-end evolutionary process. (C) The evolution of pathogens such as V. cholerae that present virulence determinants with a dual role in the environment and for infections, in which case the colonization of one of these two habitats does not severely compromise the colonization of the other (10). Reproduced with permission from reference 8.