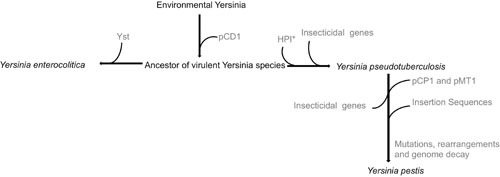

FIGURE 2.

Evolution of Y. pestis. The process of Y. pestis speciation from an environmental, nonpathogenic ancestor is a good example of the evolutionary steps that are involved in the emergence of bacterial pathogens. This process began with the acquisition of the plasmid pCD1 by environmental Yersinia. This plasmid harbors genes encoding virulence determinants such as type III secretion systems and effector Yop proteins. From this ancestor of virulent Yersinia species, two branches have evolved. One diverged through the acquisition of the Yersinia stable toxin (Yst) and led to the speciation of Y. enterocolitica. This species has further evolved through acquisition and loss of genes (not shown in this figure). The other branch diverged through the acquisition of the high pathogenicity island (HPI*), which encodes an iron-uptake system and is present as well in different Enterobacteriaceae, and by the incorporation of insecticidal genes. Y. pestis is a successful clone that emerged recently from Y. pseudotuberculosis through the acquisition of the plasmids pCP1, which encodes the plasminogen activator gene, and pMT1, which allows colonization of the gut of fleas. The loss of insect toxins is an important event for the persistence of Y. pestis in its insect vectors. The acquisition of insertion sequences is the basis of the genome rearrangements and gene loss of Y. pestis. Finally, the entire process of adaptation to a new host is modulated by the mutation-driven optimization of the regulatory and metabolic networks of the pathogen. This evolutionary process is described in more detail in references 33, 37, and 105. Reproduced with permission from reference 8.