Abstract

Polymer-based electronic devices are limited by slow transport and recombination of newly separated charges. Built-in electric fields, which arise from compositional gradients, are known to improve charge separation, directional charge transport, and to reduce recombination. Yet, the optimization of these fields through the rational design of polymeric materials is not prevalent. Indeed, polymers are disordered and generate nonuniform electric fields that are hard to measure, and therefore, hard to optimize. Here, we review work focusing on the intentional optimization of electric fields in polymeric systems with applications to catalysis, energy conversion, and storage. This includes chemical tuning of constituent monomers, linkers, morphology, etc. that result in stronger molecular dipoles, polarizability or crystallinity. We also review techniques to characterize electric fields in polymers and emerging processing strategies based on electric fields. These studies demonstrate the benefits of optimizing electric fields in polymers. However, rational design is often restricted to the molecular scale, deriving new pendants on, or linkers between, monomers. This does not always translate in strong electric fields at the polymer level, because they strongly depend on the monomer orientation. A better control of the morphology and monomer-to-polymer scaling relationship is therefore crucial to enhance electric fields in polymeric materials.

1. Introduction

Electric fields have been widely adopted in the protein community to rationalize enzyme behavior within the context of electrostatic preorganization theory.1−6 Electric fields are also used at an increasing rate to design efficient synthetic enzymes or catalytic constructs.7−9 In this case, and in the context of this review, electric fields refer to internal electric fields, also sometimes called local, interfacial, intrinsic or built-in electric fields.1,10−14 These electric fields arise from the anisotropy in charge distribution within molecules. Therefore, internal electric fields are nonuniform, following the heterogeneity of the macromolecular environment, which contrasts with the uniform, external, electric fields that can be applied to a system between electrodes.15−17

There are two main arguments that make electric fields a powerful tool for molecular design. First, the electric field at a given point in space is proportional to the gradient of the electrostatic potential and, as such, informs on the force exerted on a charge at that location. Electric fields are then directly relevant to reactivity and active processes, improving upon static energy landscapes. Second, electric fields are additive and there exists a natural decomposition into contributions from molecular fragments in the system. Although the language of electric fields has most recently been reserved for the enzyme community, it is not specific to proteins.7,8,15,18,19 For example, built-in electric fields have long been part of the characterization of the performance of electronic devices.20−23 Indeed, electric fields are responsible for the open circuit voltage, Voc, indicating how much energy can be stored in a battery, how much voltage can be used in a solar cell, how strong of a reaction can be catalyzed by a photocatalyst, etc.24−27 In these devices, electric fields promote charge separation and directional charge transport, pushing electrons and holes toward opposite ends of the device to be collected by the appropriate electrodes.28−31 In photoactive devices, electric fields also promote exciton splitting and increase the charge diffusion length, effectively preventing recombination of the newly separated charges.13,32−34 In p–n junctions for example, the photovoltaic effect is achieved by creating an electric field across the interface of two materials with opposing affinities for holes and electrons: a p-doped and n-doped semiconductor with different Fermi levels.20,31,35−37

In molecular electronics and specifically blended polymer devices, built-in electric fields are weaker over the scale of the device but strong locally, across the maximized, distributed interface where excitons split.20,38−40 These local, nanoscale, effects are harder to characterize, which partly explains the secondary role electric fields have taken in designing modern electronics. On the other hand, built-in electric fields offer the opportunity to directly address the fundamental limitations of polymeric materials, namely relatively poor transport properties and high recombination rates. As illustrated in Figure 1, stronger electric fields will reduce recombination and assist directional charge migration across polymer layers, which is indispensable to device performance. Finally, since electric fields directly act on charge migration properties, they have the added advantage of being relevant to all electronic devices, regardless of the application. This makes electric fields a unifying metric for the improvement of electronic device operation.

Figure 1.

Schematic depiction of a polymer-based electronic device with weak (left) and strong (right) built-in electric fields. Built-in electric fields reduce recombination, a major source of current loss in polymers, and improve exciton splitting as well as directional charge transport. Significant device performance improvement can be achieved by optimizing built-in electric fields in these materials.

Ideally, the optimization of electric fields will occur through the rational design of the chemical structure at the molecular scale. This strategy works well in proteins, for example, where single mutations can cause significant increases in local electric fields. For polymeric materials, however, we need better control of the morphology and microstructure, as well as a robust knowledge of the oligomer-to-polymer property scaling. Despite these challenges, many have demonstrated over the years the benefits of using electric fields as an objective function when designing novel materials for catalysis, energy conversion, and energy storage.41−44 Indeed, polymers exist with a multitude of lengths, structural, and conformational properties, allowing many strategies for the intentional design of electric fields. These efforts make the basis of this review, which is centered around electric field effects in polymeric systems. In Section 2, we review the distributed multipole expansion often used to rationalize the role of electric fields in molecular systems, as they pertain to molecular dipoles and polarizability. In Section 3, we review work that describes the optimization of electric fields in polymeric materials for electronic devices. This includes chemical tuning of constituent monomers and linkers, as well as the tuning of supramolecular polymer architecture and film morphology. In Section 4, we review innovative polymer types, such as polyelectrolytes, ferroelectric polymer additives, piezoelectric polymers and crystalline polymers, that could further enable the development of polymeric systems that generate strong electric fields. In Section 5, we review key experimental and theoretical approaches to the characterization of nonuniform electric fields in macromolecular systems. Finally, since polymers generating strong electric fields are also more sensitive to applied, external, electric fields, we review in Section 6 emerging strategies for the synthesis and postprocessing of polymeric materials that rely on external fields.

Although impressive device performance improvements are reported in the literature reviewed here, it is evident that the incorporation of electric fields as a metric for the design of novel polymers needs to be accompanied by better prediction, and control, of the morphology of polymeric materials from chemical structure. Indeed, strong dipoles on monomers do not result in strong electric fields when the overarching microstructure of the material randomizes their orientation. Similarly, emerging polyelectrolyte or piezoelectric polymers seem naturally suited to the generation of electric fields, but more work is needed to provide robust design rules. Finally, the field would benefit from characterization techniques to measure the local strength and orientation of electric fields on polymers, complementing those measuring electric fields across a device.

2. Theory

An electric field is a vector field that arises from the anisotropy in the charge distribution of the system. The electric field vector is proportional to the gradient of the electrostatic potential (eq 1), which quantifies the amount of work needed to move a unit charge from a reference point to a specific location.45−47

| 1 |

where E⃗ is the electric field, Velec the electrostatic

potential, and we use the shorthand notation  for partial derivatives. Eq 1 shows that the electric field vector

is oriented toward regions of lower potentials. At a given location,

the electric field exerts a force on charged particles, proportional

to the magnitude of the charge:

for partial derivatives. Eq 1 shows that the electric field vector

is oriented toward regions of lower potentials. At a given location,

the electric field exerts a force on charged particles, proportional

to the magnitude of the charge:

| 2 |

where F⃗ is the force experienced by the charge q. Therefore, a positive (negative) charge experiences a force in the (opposite) direction of the electric field.

In polymers and other macromolecular systems, the electrostatic potential, and therefore the electric field is nonuniform.15−17,48 Anthony Stone developed the distributed multipole approach to characterize the inherent anisotropy of charge distribution in molecular systems.49−51 We briefly outline below the key steps in the distributed multipoles expansion of the electrostatic potential.

The electrostatic potential arising at R⃗ = (Rx, Ry, Rz) from a point charge, q, located at r⃗, is given by

| 3 |

If we now assume that this charge q is the added effect of a collection of other charges, say partial charges at atomic positions, the electrostatic potential becomes

| 4 |

where the summation is carried over the a partial charges ea located at r⃗a = (rax, ray, raz) and

| 5 |

A Taylor expansion of the electrostatic potential about the origin (i.e., where r⃗a = 0), truncated at the second order, gives

|

6 |

The zeroth order term is simply:

| 7 |

The first order derivative is

| 8 |

which is nonzero only when j = l, and we get:

| 9 |

For k ≠ j, the second order derivative is (the order does not matter):

|

10 |

which is nonzero only when l = k, and we obtain

| 11 |

For k = j, the second order derivative is

| 12 |

Eqs 11 and 12 can be combined into one equation defining the elements of a (3 × 3) traceless matrix:

| 13 |

Overall, it yields for the electrostatic potential:

| 14 |

Considering that the charge, dipole and quadrupole moments can be defined as50,52−56

| 15 |

we can write

|

16 |

Note that since the second derivative is traceless (eq 13), we can use traceless quadrupole moments without a change to the equations.50,53

From eq 16, we see that, for neutral molecules where q = 0, the dipole term is the leading term. However, that term is a dot product with R⃗, meaning that the magnitude of the dipole will increase the electrostatic potential only if its orientation matches that of R⃗. This applies to the quadrupole term as well: at constant electric moments, changes in geometry (i.e., changes in R⃗) will yield significant changes in the electrostatic potential and corresponding electric field. This implies that even if the observable, electric field, is electrostatic in nature, it accounts for a multitude of other effects through the geometry of the system. For example, if the hydrogen bonding network is disrupted, it will affect the relative orientation of the bond donor and acceptor, which in turn, will affect the electrostatic potential. A similar statement can be made about solvation, polarization, and entropic effects, to name a few. In practice, changes in geometry are exacerbated by, but not solely based on, changes in charge distribution within the molecules (through partial charges, dipoles and quadrupoles). This is what makes electric fields a powerful and general metric for material design: every intermolecular and intramolecular interaction will have a signature on the electrostatic potential and underlying electric field.

Eq 16 defined the electrostatic potential at an arbitrary point. If we now consider that another molecule, say M2, is located at R⃗, its own set of charge (qM2), dipole (μ⃗M2) and quadrupole (QM2) will interact with the electrostatic potential generated by the other molecules in the system. In particular, the interaction energy between a molecule M1 at r⃗ and M2 at R⃗ can be written as

|

17 |

Similarly as in eq 16, eq 17 shows that in neutral species where the charge adds up to zero, the interaction energy is dominated by the dipole terms, including the dipole–dipole interaction term:

| 18 |

In addition, if M2 is polarizable, the electric field arising from the other molecules also creates an induced dipole at R⃗:

| 19 |

where α is the polarizability matrix. This means that even apolar (but polarizable) molecules are sensitive to electric fields. The new induced dipole at R⃗ in turn interacts with the original dipole at r⃗ through eq 17, for a mutual polarization of all molecular fragments in the environment.

In summary, the magnitude of the electric fields generated by molecular fragments, polymer constituents in our case, can be increased through greater crystallinity (dependence on R⃗), greater charge imbalance (dependence on electric moments) or greater polarizability (dependence on induced dipoles).57,58 In the following sections, we will review published work that addresses one or several of these factors.

3. Enhancing Electric Fields in Polymeric Materials for Electronic Devices

Open-circuit voltage (Voc)—the voltage difference across a device when it is not connected to any circuit—is a key performance characteristic of electronic devices. A high Voc indicates that positive and negatives charges are separated and efficiently transported to opposite electrodes, where they are collected. Voc scales with application-specific performance metrics, such as power conversion efficiency (PCE) in solar cells,30,59 energy storage in batteries,60 intensity or efficiency of light emission in light-emitting diodes (LEDs) and organic LEDs (OLEDs),61 photocatalyst activity,24,29,33,62−66 and water splitting efficiency in electrochemical cells.33,63

Built-in electric fields are an effective way to achieve high Voc because it directs positive and negative charges in opposite directions and increases the charge diffusion length within a material (see Introduction).21,25,32,67 In photoactive materials, built-in electric fields also assist exciton dissociation, converting bound electron–hole pairs into separated free charge carriers.57,68−72 Strong built-in electric fields are especially important to enhance the Voc of polymer-based materials where geminate recombination of photogenerated charge carriers occurs frequently, limiting device efficiency.69,71 In this section, we will review work that has been done to improve built-in electric fields in polymeric materials. This includes modifications of photoactive layers as well as interface engineering in organic photovoltaics, LEDs, and other electronic devices. Since built-in electric fields are relevant to all electronic devices, the section is organized by strategy employed to increase the fields, rather than by application. To facilitate navigation to those interested in the applications, we summarized the key papers in Table 1.

Table 1. List of Systems and Improvements Due to Electric Fields Reported in the Papers Reviewed in Section 3, by Application and by Strategya.

| Strategy | Application | System | Reported improvement |

|---|---|---|---|

| Monomer design (Section 3.1) | Photocatalyst for H2 production | PCPs65 | μ ∼ 1.5 D, photocatalytic activity ×10 |

| CMPs29,73 | μ + 3.8 D, Yield ×1.5 | ||

| TPPS/PDI74 | Efficiency ×10 | ||

| Active layers in solar cells | PTB775 | Voc + 0.1 V, Efficiency ×3.6 | |

| PTBF1,76 DTFFBT77 | Voc + 0.1 V, Efficiency +2% | ||

| P1, P278,79 | Highest efficiency to date (16%) | ||

| Electrode interlayers | p-PFP/PFN30 | Efficiency +1.3% | |

| PBTA-FN80 | Elec. field +0.1 V | ||

| PDIN-N-FN59 | Efficiency +2.7% | ||

| Linker design (Section 3.2) | Photocatalyst for H2 production | MNBN1, PNBN81 | μ + 7.3 D, surface potential ×8 |

| PDI linkers33,62 | μ + 4.8 D, photocurrent ×30 | ||

| H-bond PDI linkers64 | Photocatalytic activity ×8 | ||

| Active layers in solar cells | DPP, DPP-DTP82−84 | Exciton binding energy –0.4 eV | |

| Y6 derivatives85,86 | Highest efficiency to date (17.2%) | ||

| Supramolecular architecture tuning (Section 3.3) | Lithium batteries | NT-U/NDI39 | Elec. field ×7.3, discharge capacity ×3 |

| CP-PDAB,87 polyimide88 | High specific capacity (>140 mAh g–1) | ||

| PPTS89 | 5000 charge–discharge cycles | ||

| Photocatalysis | PcOp-Fe38 | Surface potential +180 mV | |

| Porphyrin complexes74,90 | Electric field ×10 | ||

| PDI/BiOCl91 | Efficiency ×2 |

3.1. Enhancing Electric Fields by Monomer Design

A rational strategy to enhance a polymer’s internal electric field is through selective tuning of its monomers. As detailed in Section 2, this can be achieved by designing functional groups that will increase the electric moments of the monomers (e.g., charge, dipole, quadrupoles, etc.) or the polarizability. For example, Li et al. emphasized the importance of tuning the internal polarization of acceptor comonomers when constructing donor–acceptor copolymers as photocatalysts for hydrogen production.65 They designed sets of porous conjugated polymer (PCP) networks using 12 different acceptors with a 4,8-di(thiophen-2-yl)benzo[1,2-b:4,5-b’]dithiophene (DBD) donor, as shown in Figure 2. They found that the best performing PCPs were those containing ligands with varied nitrogen atoms such as pyridine and diazine. They attributed this effect to a stronger internal polarization, therefore a stronger dipole (see eq 19), enabling effective charge separation.65 PCP10 and PCP11 exhibited the highest activities with 103.6 and 106.9 μmol h–1, respectively, compared to 1.9–10.1 μmol h–1 for PCP0–PCP3. When comparing the activity of PCP10 and PCP11 to the dipoles of the comonomers, they found that an appropriate range for the dipole was 1.10–1.65 D. However, they also noted that the orientation of the dipole was key when PCP9, despite having a 3.53 D dipole, did not show higher catalytic activity (30.4 μmol h–1) than PCP10 and PCP11.65

Figure 2.

Scheme showing the structures of comonomers (M0–M11) and DBD which were used to prepare polymers PCP0–PCP11. Adapted with permission from Li, L.; Lo, W.-y.; Cai, Z.; Zhang, N.; Yu, L. Donor–acceptor porous conjugated polymers for photocatalytic hydrogen production: the importance of acceptor comonomer. Macromolecules2016, 49, 6903–6909. Copyright 2016 American Chemical Society.

Xu et al. were also successful in improving hydrogen evolution rates by modulating the ratio of pyrene to benzothiadiazole units in a series of donor-π-donor (D-π-D), donor-π-acceptor (D-π-A), and π-acceptor (π-A) conjugated microporous polymers (CMPs). They find the highest rates among the D-π-A CMPs (106.2 μmol h–1), and the lowest rates among the π–A CMPs (0.5 μmol h–1).73 They did not directly attribute their findings to dipole or electric field effects, instead focusing on increased rates brought on by scattering due to the porous nature of the materials.73 Still, structures like the D-π-A system have been implicated in other studies for their ability to increase electric fields.92,93 For example, Wang et al. expanded on the study by Xu et al., investigating the modulation of D-π-A CMPs through the acceptor building block as photocatalysts for the synthesis of benzimidazole.93 Varying the acceptor block between pyridazine (Dz), pyrazine (Pz) and pyrimidine (Py), using benzene (B) as the π-bridge, and carbazole as the donor group (Figure 3), they found that Py-B-CMP produced the highest yield (95.5%) compared to Pz-B-CMP (30%) and Dz-B-CMP (21%). They attributed the superior performance of Py-B-CMP to the built-in electric fields resulting in increased photogenerated carrier separation.93 Although the magnitude of the dipole of the Dz-B-CMP monomer (3.27 D) was much larger than those of Py-B-CMP (2.23 D) and Pz-B-CMP (0.018 D), the electric field of Dz-B-CMP was perpendicular to the molecule, hindering separation.93 In contrast, Py-B-CMP had a dipole direction along the polymer chain, which assisted in separation and migration of electron hole pairs along the chain (Figure 4).93

Figure 3.

Scheme showing the synthesis of CMPs with the varied acceptors shown in red, π-bridges (benzene) in black, and carbazole in blue. Reproduced with permission from ref (93). Copyright 2024 Elsevier.

Figure 4.

Dipole moments and molecular electrostatic potential maps of the CMP monomers. Adapted with permission from ref (93). Copyright 2024 Elsevier.

In another proof-of-concept study, the monomer core structure of CMPs that had poor photocatalytic activity due to high exciton binding energies was modified to increase molecular dipoles and built-in electric fields.29 The carbazole-based monomers 1,4-di(9H-carbazol-9-yl) benzene (DCB), (2,6-di(9H-carbazol-9-yl) anthracene-9,10-dione (DCD), and (2,7-di(9H-carbazol-9-yl)-9H-fluoren-9-one (DCF) were polymerized to form the photocatalytic polymers denoted as CbzCMP-7, CbzCMP-8, and CbzCMP-9 respectively, shown in Figure 5. Using density functional theory (DFT) they calculated the dipoles of the monomers to be 0.0021, 0.0776, and 3.7819 D, respectively, and found that they correlate with the relative built-in electric field intensity observed experimentally.29 Overall, the yield for the photocatalytic construction of the thiocyano chromones was improved to 95% for CbzCMP-9 (highest dipole), 64% for CbzCMP-7 (lowest dipole), and 82% for CbzCMP-8.29

Figure 5.

Scheme showing the tested polymers along with calculated dipoles and general catalytic mechanism. Reprinted (adapted) with permission from Deng, Z.; Zhao, H.; Cao, X.; Xiong, S.; Li, G.; Deng, J.; Yang, H.; Zhang, W.; Liu, Q. Enhancing built-in electric field via molecular dipole control in conjugated microporous polymers for boosting charge separation. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces2022, 14, 35745–35754. Copyright 2022 American Chemical Society.

In a similar vein, Carsten et al. investigated how the dipole of a polymer influences its performance as the active material in a solar cell.75 They predicted that poly(bi[thieno[3,4-b]thiophenyl]-2,2′-dicarboxylic acid bis(2-butyl-octyl) ester-co-di(2-butyl-octyl)benzo[1,2-b:4,5-b’]dithiophene) (PBB3) and poly(3-fluoro-thieno[3,4-b]thiophene-2-carboxylic acid 2-butyl-octyl ester-co-di(2-butyl-octyl)benzo[1,2-b:4,5-b’]dithiophene) PTB7 had the smallest and greatest change in ground state to excited state dipole moment (0.47 and 3.92 D, respectively), defined as follows:

| 20 |

where Δμge is the change in dipole moment from the ground state to excited state, μgx,y,z and μex,y,z are each of the directional vector components of the ground state and excited state dipole moments, respectively. They reported the Voc of PTB7 at 0.74 V and its PCE at 7.40%, whereas the Voc of PBB3 was 0.63 V and its PCE 2.04%.75 PBB3 also exhibited the fastest charge recombination rate when analyzed using transient absorption spectroscopy (Figure 6). Conversely, PTB7 showed a long-lived state that could not be measured on the time scale of the experiments.75 Overall, the work by Carsten et al. supports the fact that the increased dipole of PTB7 generates a stronger built-in electric field in the polymeric active layer, which reduces charge recombination and increases the performance of the solar cell.

Figure 6.

A scheme representing the influence of monomer/polymer dipole on power conversion efficiency. Reprinted (adapted) with permission from Carsten, B.; Szarko, J.M.; Son, H.J.; Wang, M.; Lu, L.; He, H.; Rolczynski, B.S.; Lou, S.J.; Chen, L.X.; Yu, L. Examining the effect of the dipole moment on charge separation in donor–acceptor polymers for organic photovoltaic applications. J. Am. Chem. Soc.2011, 133, 20468–20475. Copyright 2011 American Chemical Society Copyright 2011 American Chemical Society.

The same research group expanded upon the above work, investigating poly(thienothiophene-co-benzodithiophene) with varied fluorination, as shown in Figure 7a.76 PTBF2 and PTBF3 were predicted by DFT to have the smallest inter-ring dihedral angle (179.5° and 179.8°, respectively), owing to sulfur–fluorine interactions. When cast as films from dichlorobenzne/1,8-diiodooctane, PTBF1 demonstrated the highest PCE of 7.2% and a Voc of 0.74 V, both of which exceeded PTBF0 (5.1% and 0.58 V, respectively).76 However, despite their increased planarization, PTBF2 and PTBF3 demonstrated a lower PCE (3.2% and 2.3%, respectively) than PTBF1 and PTBF0. Transmission electron microscopy revealed phase separation between PTBF2/PTBF3 and PC71BM with domains ranging from 50 to 200 nm, which far exceeds the expected exciton diffusion length of 10 nm. This phase separation was attribtuted to the increased fluorine content making it less compatible with PC71BM than PTBF0 or PTBF1. In parallel, Stuart et al. designed variably fluorinated benzothiadiazole polymers, as shown in Figure 7b.77 They found that Δμge increased with fluorination, yielding 1.20 D for polymers without fluorines, 15.18 D for the monofluorinated polymer, and 16.02 D for the difluorinated polymer. They also reported the difluorinated polymer to have the greatest Voc (0.90 V), PCE (6.64%), and the least geminate recombination. By comparison, the unfluorinated polymer yielded Voc = 0.78 V, PCE = 4.33%, and the most geminate recombination.77

Figure 7.

Polymers based on (a) thienothiophene,76 (b) benzthiadiazole acceptors,77 and their fluorinated analogues. (c) Examples of alokxy substitued bithiophenes and bithiazoles.78

Guo et al. investigated alkoxybithiazole monomers with a similar motivation.78 The inter-ring dihedral angle of the alkoxybithiophene monomer (P1) was predicted to be 23°, whereas the alkoxybithiazole (P2) was predicted to be 0°, facilitated by a weak C–H–N hydrogen bond in addition to the S–O interaction that is present in both (Figure 7c).78 Recently, Wu et al. utilized these alkoxybithiazole comonomers toward all-polymer solar cells.79 They observed similar results, where the alkoxybithiazoles (0.3°–0.7°) increased the planarity compared to bithiophene (8.8°–11.6°) and exhibited even less geminate recombination. This enabled the highest performing printed all polymer solar cell for its time (in 2024) with a PCE of 16.0%.79

The above studies reported on innovations to increase the dipole moment of polymer constituents to enhance electric fields in the photoactive layers of electronic devices. Others have instead engineered better interlayers between the photoactive material and the electrodes. Interlayers are routinely used in polymer solar cells, tuning the Fermi level of the metal electrodes and improving the collection efficiency of the photogenerated charges. Interlayers are charge transporting layers (CTLs), traditionally composed of conducting polymers like poly(3,4-ethylenedioxythiophene) doped with poly(styrene-sulfonate) (PEDOT:PSS)94−97 or metal oxides.20,98−100 Lee et al. conceived a new type of paired electric dipole layers (EDLs), to serve as cathode and anode interlayers, with conjugated polyelectrolyes (CPEs) and non-CPE polymers.30 For the anode interlayer, they tested CPEs based on p-doped poly[9,9-bis(4′-sulfonatobutyl)fluorene-alt-1,4-phenylene] (p-PFPs). The designed polymers varied in self-doping levels, reported as p-PFP-WD, p-PFP-MD, p-PFP-HD, for weakly (WD), moderately (MD), and highly (HD) doped, and p-PFP-O containing phenyl-OMe as a tethering functional group (O). For the cathode interlayer, they compared amine-based CPE poly[(9,9-bis(3′-(N,N-dimethylamino)propyl)-2,7-fluorene)-alt-2,7-(9,9-dioctylfluorene)] (PFN) and non-CPEs polyallylamine (PAA) and polyethyleneimine (PEI). They found that paired EDLs maximized the electric field across the photoactive layer, and therefore the Voc of the corresponding solar cell. Ultimately, they were able to construct a polymer solar cell with 9.8% PCE, which improves significantly upon the 8.5% PCE of the solar cells made with traditional CTLs.30

Similarly, Liu et al. aimed to optimize the efficiency of organic solar cells with an alcohol-soluble conjugated polymer named PBTA-FN.101 PBTA-FN is derived from poly[(9,9-bis(3′-(N,N-dimethylamino)propyl)-2,7-fluorene)-alt-2,7-(9,9-dioctylfluorene)] (PFN), a polymer previously reported as successful cathode interlayer in diodes,80 with fluorene and benzotriazole (BTA) groups. They found that the electron-deficient and amino groups in PBTA-FN yield larger interface dipoles compared to PFN. Consequently, they measured an increase in built-in electric field across the device, going from 0.72 V for PFN to 0.81 V for PBTA-FN, which inhibits bimolecular recombination and enhances device performance.101

The same research group later designed other cathode interlayers using self-doping CPEs based on naphthalenediimide (NDI).59 They systematically modified the NDI-based monomer pendant groups to synthesize three CPEs: poly[(2,7-bis(2'-butyloctyl)naphthalenediimide-4,9-diyl)-alt-(9,9-bis(3-N,N-dimethylaminopropyl)-9H-fluorene-2,7-diyl)] (PNDI-FN), poly[(2,7-bis(3-(dimethylamino)propyl)naphthalenediimide-4,9-diyl)-alt-(9,9-dioctyl-9H-fluorene-2,7-diyl)] (PNDI-N-F) and poly[(2,7-bis(3-(dimethylamino)propyl) naphth-alenediimide-4,9-diyl)-alt-(9,9-bis (3-N,N-dimethylaminopropyl)-9H-fluorene-2,7-diyl)] (PNDI-N-FN). They report that modulating the polymer dipoles through the number and position of polar groups boosted built-in electric fields, improving conductivity, work function tunability and interfacial interactions. The solar cells made from these CPEs exhibited PCEs of 8.27% (PNDI-FN), 8.48% (PNDI-N-F), and 9.01% (PDIN-N-FN), a significant increased compared to the PCE of solar cells in absence of CPEs (6.31%).59

Yang et al. boosted photocatalytic H2 evolution by constructing an electron donor–acceptor (D-A) interface between tetra(4-sulfonatophenyl)porphyrin (TPPS) and PDI, which resulted in an evolution rate of 546.54 μmol h–1, 9.95 times higher than pure TPPS and 9.41 times higher than PDI.74 The interfacial electric field from PDI to TPPS facilitates charge transfer, increasing exciton separation efficiency and hydrogen production.74 The internal electric field was found to be 3.76 times higher in TPPS/PDI than in pure PDI and 3.01 times higher than pure TPPS.74

Hwang et al. used ultrafast electronic spectroscopy to monitor the formation of charge-transfer excitons in two conjugated polymers.102 The absorption for poly(N-11″-henicosanyl-2,7-carbazole-alt-5,5-(4′,7′-dithienyl-2’,1’,3′-benxothiadiazole) (PCDTBT) red-shifted in a more polar solvent, which suggests an increase in the dipole moment through eq 21:

| 21 |

where μe2 and μe1 are the equilibrium and nonequilibrium dipole moments respectively, ϵ0 is the permittivity, a is the interaction cavity radius, ϵ is the dielectric constant, and n is the refractive index. From this they found that the change in polymer dipole changes by 3.3 D upon excited state equilibration, which was corroborated by changes in the excited state structure using DFT.102 While not explicitly measured in the above study, they allude to the change in dipole explaining why PCDTBT-based solar cells demonstrate efficiency without an exogenous acceptor.103 Cheng et al. also leveraged ultrafast spectroscopy to study the electron dynamics in a friedel-crafts polymerized dibenzothiophene.104 Upon photoexcitation, the sulfur atoms can spontaneously oxidize in the presence of air to form sulfones, changing from a homopolymer to a donor–acceptor copolymer in situ. As such, the dipole moment was predicted to increase from 0.62 to 6.17 D by DFT, and this helped facilitate charge separation as determined by TAS.104 Upon this change they also observe an increase in the photocatalytic production of H2O2 from 841 μM h–1 (homopolymer) to 1321 μM h–1 (donor–acceptor copolymer), which they attribute to the change in structure and its impact on properties.

3.2. Enhancing Electric Fields by Linker Design

The molecular dipole of a polymer, and its corresponding ability to generate electric fields, can also be optimized through the linkers between monomers. Willems et al. tested a library of 19 diketopyrrolopyrrole (DPP)-based copolymers with varying linkers between DPP units in bulk heterojunction solar cells.82 Using their novel DPP-based polymers as donor and phenyl-C61-butyric acid methyl ester (PCBM) as acceptor, they found a correlation between the electronic properties of the polymers, namely the oxidation potential, and the Voc of the corresponding solar cells. The same research group later expanded this work to π-conjugated linkers in DPP-dithieno[3,2-b:2′,3′-d]pyrrole (DTP) copolymers. Interestingly, they reported that the nature of the linker influences the exciton binding energy, which ranged from 0.09 eV with a phenyl linker to 0.44 eV with a thiazole linker (Figure 8a).83 Although the authors did not explicitly refer to enhanced molecular dipoles, the reduction in exciton binding energy they observed when changing the linker is consistent with an increased compositional gradient across the distributed interface within the bulk heterojunction solar cell and therefore, an increased electric field supporting the separation of photogenerated charges.

Figure 8.

(a) Structures for two of the DPP copolymers with different π linkers.83 (b) Structures for two Y6 copolymers.85

Although it is recognized that a large change in dipole moment in donor-π-acceptor copolymers promotes charge carrier generation, the rational design of polymers with such electronic properties is not trivial.84,105,106 Roy et al. identified thiophene coplanarity as a primary structural factor to increase the dipole moment of poly(DPP-co-benzodithiophene), as shown in Figure 9a.84 Using femtosecond stimulated Raman spectroscopy, they showed that the absorbance band at 1228 cm–1, corrersponding to the thiophene C–H bending mode, and the one at 1422 cm–1, corresponding to the thiopohene C = C stretching mode, red-shifted by 5 and 4 cm–1, respectively, upon excitation. Using DFT, they were able to demonstrate that the relative intensity of the signal at 1228 cm–1 vs 1422 cm–1 correlates with changes in the thiophene bridge angle, as shown in Figure 9b. Their ultrafast spectroscopic data further supported that the π-bridge torsion angle influence the exciton dissociation rate through fine-tuning of the polymer dipole moment (Figure 9c).84 From this data, they suggest that designing π-bridges in conjugated polymers that quickly planarize upon excitation (ie. assisted through noncovalent interactions) will improve exciton dissociation and device efficiencies.

Figure 9.

(a) The polymer structure investigated. (b) The ratio of the two tihophene Raman absorptions as a function of dihedral angle as predicted by DFT (B3LYP/6-31+G). (c) Scheme for the proposed intramolecular charge transfer mechanism. Reprinted (adapted) with permission from ref (84). Copyright 2017 Springer Nature.

The optimization of π-bridge linkers was also pursued in the development of novel nonfullerene acceptors for organic solar cells. Indeed, independent groups have reported that π-bridge linker design for nonfullerene acceptors enables better exciton dissociation, charge extraction, and charge transport.85,107,108 To this end, several small molecule acceptors copolymerized with a π-bridge unit have been proposed.85,109−112 In particular, Yuan et al, reported polymers based on the small molecule acceptor (2,20-((2Z,20Z)-((12,13-bis(2-ethylhexyl)-3,9-diundecyl-12,13-dihydro-[1,2,5]thiadiazolo[3,4-e]thieno[2,”3”:4′,50]thieno[20,30:4,5] pyrrolo[3,2-g]thieno[20,30:4,5]thieno[3,2-b]indole-2,10-diyl)bis(methanylylidene))bis(5,6-difluoro-3-oxo-2,3-dihydro-1H-indene-2,1-diylidene))dimalononitrile) (Y6) using thiophene and difluorthiophene as linkers.113 Y6 derivatives, including polymerized small molecule acceptors with difluorene substituents on the thiophene π-bridge linker (Figure 8b) resulted in solar cells with 17.24% PCE, which was among the highest efficiencies reported for all-polymer solar cells in 2022.85 Alternatively, Fan et al. demonstrated that selenophene π – linkers yields solar cells with 15.1% PCE, compared to selenophene-free polymer acceptors with 13.0%.86 This group of studies reveals a strong correlation between the introduction of polar groups in π-bridge linkers, thereby modulating the dipole of the corresponding copolymer, and enhanced transport properties across electronic devices.

More recently, Ru et al. investigated how changing a simple phenyl-linker for a pyridyl-linker enhanced the built-in electric field in a conjugated polymer for photocatalytic hydrogen production.81 More specifically, they characterized the properties of phenyl-linked napthalene (MNCC1), pyridyl-linked napthalene (MNNC1), and pyridyl-linked aminonapthalene (MNBN1), as shown in Figure 10a. The molecular dipoles were predicted by DFT to be 0.13, 1.90, and 4.96 D, for the MNCC1, MNNC1, and MNBN1 monomers, respectively (Figure 10b).81 They rationalized the increased dipole moment by the presence of the relatively electron deficient pyridyl-linkers, an effect exacerbated by the presence of an amino-group through the planarization of the two rings. Kelvin probe force microscopy (KPFM) was used to measure the surface potential of the corresponding polymers: PNCC (19.8 mV), PNNC (31.7 mV), and PNBN (55.7 mV), as shown in Figure 10c. Meanwhile, their zeta potential was −12.91 mV, −13.29 mV, and −32.36 mV, respectively (Figure 10d). Both of these potentials are proportional to the magnitude of the built-in electric fields across the films, with PNBN having the greatest of the three polymers studied, consistent with its higher dipole moment. Correspondingly, they observed a photocurrent density for PNBN of 0.24 μA cm–2, which was 10 and 30 times greater than that of PNNC and PNCC, respectively (Figure 10e). This work builds upon existing literature that leverages B → N coordination to simultaneously planarize the backbone and modify the distribution of electron density,114−117 but specifically emphasizes the influence this has on the resulting electric field.81 Overall, their work highlights the importance of internal electric fields as a design principle for conjugated polymers.

Figure 10.

(a) Schematic of the three polymers investigated. (b) DFT (B3LYP/6-311G(d,p) calculated dipole moments and electrostatic potential maps for each of the corresponding monomers. Kelvin probe force microscopy (c), zeta potentials (d), and current density plots (e) of the three polymers.81 Reprinted (adapted) with permission from ref (81). Copyright 2022 John Wiley and Sons.

Linkers can also be used to intentionally decrease the planarity between symmetric monomers (i.e., with low dipole moment), which yields a more pronounced net dipole moment for the polymer. For example, Chen et al. recently investigated perylene diimide (PDI) polymers for hydrogen evolution.33 PDI polymers and other perylene-based polymers are commonly studied in photocatalysis,24,33,62−64,66,91,118 OLED,61 and other electronic device applications.119 PDI linkers such as urea62 and triazine24 have shown to increase the photo-oxidation rate of water and phenol, respectively, due to increased internal electric fields derived from improved crystallinity. In their work, Chen et al. used one of three simple phenyl-linker motifs to construct ortho- (oPDI), meta- (mPDI), or para- (pPDI) substituted poly(PDI), as shown in Figure 11a.33 They predicted the dipole moment of dimers with DFT. Starting from the PDI unit at 0.00026 D, they found increasing dipole moments of 0.0017, 3.9, and 7.3 D as the phenyl substitution goes from p-, to m-, to oPDI and the coplanarity decreases, as shown in Figure 11b.33 Similar trends were observed with trimers where the pPDI trimer exhibited a small dipole moment of 0.00055 D, owing to its planarity, and mPDI trimers were reported at 3.33 D (pseudotrans isomer) and 6.6 D (pseudocis isomer). Interestingly, the calculation of the dipole moment of oPDI trimer yielded 6.4 and 0.0014 D, depending on the configuration. However, the oPDI tetramer was predicted to have a dipole moment of 7.2 D, providing further insight on how to extrapolate these results from oligomers to polymer properties.33 They characterized the polymeric materials with KPFM, which showed a surface potential of 62.02 mV for oPDI. This was 1.82 and 8.36 times greater than that for mPDI and pPDI, respectively (Figure 11c).33 Zeta potential measurements followed a similar trend, with oPDI reported at −30.2 mV, which was 1.67 and 1.59 times greater than that of mPDI and pPDI, respectively (Figure 11d).33 Both the surface and zeta potentials generally agree with the predicted dimer dipole moments, highlighting the influence of the molecular level dipole on the polymer electric field.

Figure 11.

(a) Schematic representation of the o- m-, and pPDI polymer syntheses. (b) DFT (RB3LYP/6-31G(d,p)) predicted dipole moments of a PDI monomer, as well as dimers and trimers of the various PDI polymers. THe surface potential (c) and zeta potential (d) of the three PDI polymers. Reprinted (adapted) with permission from ref (33). Copyright 2023 John Wiley and Sons.

Zhang et al. explored the influence of the nature of linkers between PDI units on their photocatalytic properties.62 As opposed to varied disubstituted phenyl-linkers, this synthesized an ethylene linker, a direct nitrogen-to-nitrogen PDI coupling, and a urea linker (Figures 12a and b), following previously reported protocols.119,120 This study built upon previous work using small molecule PDI systems, which assembled through noncovalent interactions,121,122 as well as a small molecule porphyrin system.123 They reported surface potential measurements of 8.75 mM, 15.31 mV, and 30.88 mV, respectively (Figure 12c). The same trend persisted for zeta potentials, which were reported at −0.15 mV, −26.23 mV, and −44.05 mV, respectively (Figure 12d). Therefore, each of these linkers contributed to an increased built-in electric field, which was purported to yield greater catalytic efficiency.62

Figure 12.

Structure of the three polymers (a) and a schematic of the impact of the BIEF effect (b). The surface potentials (c) and zeta potentials (d). Reprinted (adapted) with permission from ref (62). Copyright 2020 John Wiley and Sons.

Wang et al. also investigated how noncovalent tethers would impact similar PDI systems.124 They attached carboxylic acid pendents from the PDI units, which formed dimer-like hydrogen bonds between units. The PDI units were then able to π–π stack to form a supramolecular network. Zhu later used this design motif in conjunction with fullerene to enhance its photocatalytic activity 8.24 times compared to designs without the PDI species.64

3.3. Enhancing Electric Fields by Supramolecular Architecture Tuning

In the previous section, we discussed how linkers can influence polymer morphology and its impact on electric fields. This has largely been in the context of intramolecular interactions like backbone planarization that aligns the dipoles of the side chains. However, electric field effects in polymeric materials are also highly susceptible to intermolecular and interchain interactions such as π–π stacking. Indeed, Chen et al. demonstrated that layer-stacked polyimide had high crystallinity, which significantly enhanced built-in electric fields across the material in a lithium ion battery.39 They showed that these higher electric fields improved charge transport dynamics and electrochemical performance, highlighting the importance of morphology control. The linkers investigated in their work were an ethlyene- (NT-E) and a carbonyl-linker which generated a urea motif (NT-U) between each NDI unit.39 This motif is not unique,62 but their study brings built-in electric fields into focus. They predicted the molecular dipole of NT-E and NT-U dimers with DFT, yielding μ = 0.11 and 2.60 D, respectively (Figures 13a and b).39 The larger NT-U dipole moment compounds, where three dimers coordinated by a π–π stacking interaction exhibit a dipole of μ = 8.10 D, which is more than three times that of its components. Interestingly, the NT-U dimers are predicted to have a smaller dipole moment than oPDI discussed above,33 though the previously mentioned study did not investigate the influence of π–π stacking. The same effect for NT-E yields an increase from 0.11 to 0.64 D, which is more than five times greater than the components. However, the overall dipole magnitude of the NT-E trimer is still notably less than NT-U.39 X-ray diffraction data showed that NT-U was much more crystalline, which agrees well with the predicted dipolar alignment. They measured surface potentials with KPFM (Figures 13c and d) and found that NT-U exhibits a greater surface potential than NT-E. Coupled with zeta potential measurements, they found that NT-U generate an electric field 7.29 times greater than NT-E (Figure 13e).39 This increased electric field was then linked to the observed enhancement of charge transport in the same polymers when tested as a cathode in lithium ion batteries. NT-U showed greater initial theoretical discharge capacity of 60% (152/245 mAhg–1) compared to NT-E at 19% (31/163 mAhg–1). This example ties in the influence of linkages on the crystallinity of polymeric materials, achieved via π–π stacking, and their impact on built-in electric fields.

Figure 13.

Molecular dipole of NT-E (a) and NT-U (b) with different layers and degrees of polymerization based on DFT calculations (B3LYP/6-311+G(d,p)). The surface potential of NT-E (c) and NT-U(d) measured using KPFM. (e) Analysis of the built-in electric field for each polymer. Reprinted (adapted) with permission from ref (39). Copyright 2024 Elsevier.

Although they did not explicitly measure the corresponding built-in electric field, several other groups have investigated polymers with extended conjugation, yielding to higher crystallinity and enhanced electrochemical performance.87−89,125 Chen and Wang postulate that the higher crystallinity of polymeric materials is beneficial for cathodic materials in sodium or lithium ion batteries.126 Indeed, Pang et al. proposed conjugated porous polyimide poly(2,6-diaminoanthraquinone) benzamide (CP-PDAB), shown in Figure 14a, as an organic cathode material for sodium ion batteries.87 They demonstrated that the porous and loose structure of CP-PDAB enabled high cycling stability, achieving a specific capacity of 141 mAh g–1 at 500 mA g–1.87 Similarly, Ba et al. synthesized polyimide derivatives bearing anhydride with benzoquinone for lithium ion batteries (Figure 14b), realizing a reversible specific capacity of 145 mAh g–1 at 0.1 C.88 This performance enhancement was attributed to the micromorphology of the material after addition of the conjugated carbonyl groups from benzoquinone. Tang et al. reported the same result with poly(pentacenetetrone sulfide) (PPTS) (Figure 14c), which achieved a reversible specific capacity of 290 mAh g–1 at a current rate of 100 mA g–1.89 Importantly, these properties were largely retained after as many as 5000 charge–discharge cycles. Wang et al. further explored this idea with poly(NDI-co-phenylene) and an amide linkage between the two aromatic motifs (Figure 14d). This polymer also showed exceptional reversible capacity of 213.4 mAh g–1 at a current rate of 50 mA g–1. Interestingly, most of the polymers discussed above are predicted to have a small monomeric dipole moment.87−89,126

Figure 14.

(a) Poly(pyromellitic diimide-co-anthraquinone),87 (b) benzoquinone-based copolymer,88 (c) poly(pentacenetetrone sulfide),89 and (d) poly(NDI-co-phenylene) with an amide linkage.125

In the context of photocatalysis and energy storage, many higher-dimensional conjugated materials are promising due to their inherently strong crystallinity and organization through π–π stacking. For example, 2D Phthalocyanine (Pc) polymers are an exciting material owing to their extended π-conjugation and rigid structure.127,128 Further, Pcs can be modified with various metal cations, which bind to the macrocyclic isoindoles, to tune their local electron density and alter their properties.127−129 Miao et al. recently studied Pc polymers and the impact of incorporating iron ions to modify its intrinsic electric field.38 The iron containing Pc polymer (PcOP-Fe) was prepared with a facile approach130 by combining benzene-1,2,4,5-tetraacbronitrile (BTC) with FeCl3 suspended in ethylene glycol and DBU, and allowed to react in a microwave reactor for three minutes (Figure 15a). A metal-free derivative (PcOP) was also prepared as a control. The surface voltages were measured to be −10 mV and 170 mV for PcOP and PcOP-Fe, respectively, as shown in Figures 15b and c. Further, zeta potentials were observed to be −0.40 mV and +0.87 mV, respectively. The greater magnitude of both surface and zeta potentials demonstrate that the presence of iron in the Pc macrocycle increases the built-in electric field in PcOP-Fe, compared to PcOP. PcOP is predicted to have high electron density on the nitrogen atoms linking each isoindole unit, with greater cationic character on the outerlying aromatic rings and at the center of the macrocycle (Figure 15c). For PcOP-Fe, the positive charge is concentrated in the center, with the outerlying benzene rings being relatively more electron-rich (Figure 15d). The more uniform charge distribution in PcOP-Fe is purported to reduce electronic dispersion and generate an electric field from the center to the perimeter, which ensures faster transfer kinetics when used as a photocatalyst.38

Figure 15.

(a) Schematic representation of the FePc polymer synthesis. Surface voltage measurements for the iron-free (b) and iron-containing (c) Pc polymers. Surface electrostatic potentials for the iron-free (d) and iron-containing (e) Pc polymers, calculated by DFT (B3LYP/cc-PVTZ). Reprinted (adapted) with permission from ref (38). Copyright 2022 Elsevier.

Jing et al. have also studied donor–acceptor type porphyrin complexes of Zinc tetraphenyl porphyrrin and tetrakis(4-hydroxyphenyl) porphyrin. The composite material generated an interfacial electric field that was 3.1 and 3.8 times greater than either of the respective components.90 Later, Yang et al. studied donor–acceptor type porphyrin-PDI complexes to a similar effect, generating an interfacial electric field that was 9.95 times greater than tetraphenyl porphyrin sulfonate, and 9.41 times greater than PDI alone.74 While these are small molecule systems, the enhanced internal electric fields may be promising when applied to polymers. Meanwhile, Gao et al. developed a PDI/BiOCl photocatalyst for the degredation of phenols.91 By using a weight ratio of 0.3 BiOCl:PDI, they found that PDI/BiOCl self-assembled with π–π stacking. Under full-spectrum light, PDI/BiOCl improved organic pollutant removal efficiency by 2.2 times compared to BiOCl and 1.6 times compared to PDI.91 PDI/BiOCl also had a photocurrent intensity of 4.17 μA cm–2 compared to 0.37 μA cm–2 for pure BiOCl and 0.76 μA cm–2 for PDI, showing that the donor-to-acceptor nature present in PDI/BiOCl benefitted the charge separation of photogenerated carriers.91

3.4. Opportunities for Electric Field Optimization

Supramolecular organization effects are relevant in the condensed phase as well as the solid-state. In earlier sections, we discussed how built-in electric fields often result from monomers with prominent dipoles and the way they organize. As such, it is reasonable to expect strong electric fields in supramolecular polymers, where monomer units arrange into a long chain due to short-range noncovalent interactions.131 However, electric fields in these systems are largely unexplored. In this section, we survey examples of supramolecular polymer architectures that leverage design principles (i.e., monomer dipole alignment, π–π stacking toward crystallinity) similar to those required for the generation of strong electric fields. This aims to highlight potential gaps in knowledge for future exploration in the field.

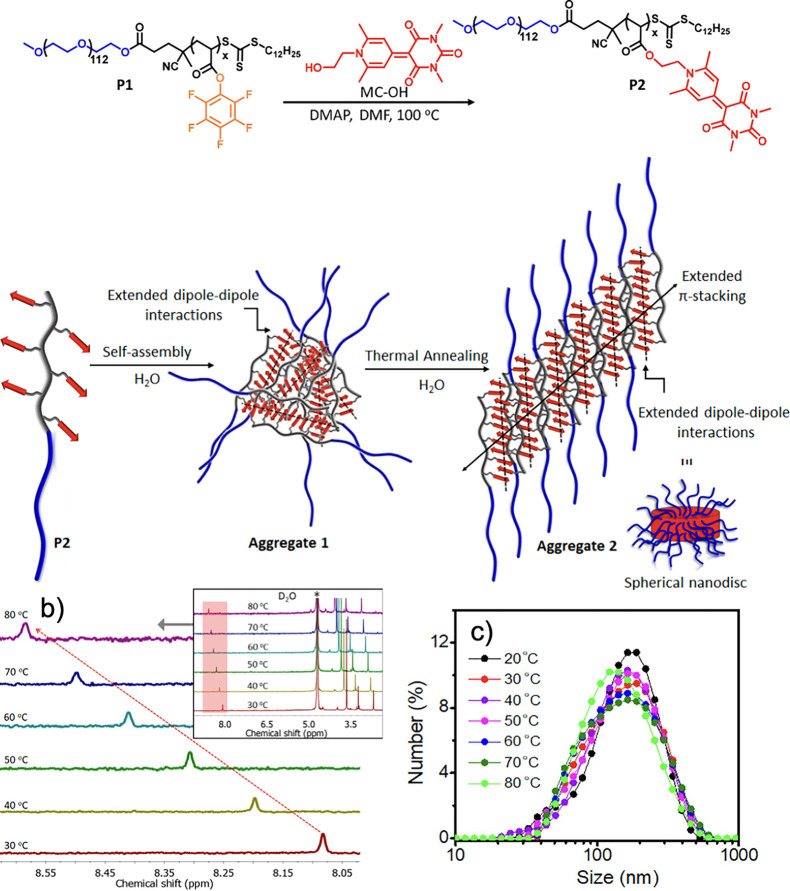

Merocyanines are a common chemical motif in supramolecular polymers due to their large intrinsic dipole moments, often exceeding 7 D, that cause self-assemblly through dipole–dipole interactions (Figure 16).132 Merocyanine structures are diverse and highly tunable, making them ideal for use in an array of chemical environments.133−136 However, examples demonstrating long-range organization through these dipolar interactions are limited.137−140 Recently, Rajak and Das synthesized a block copolymer with a segment containing merocyanine pendents to leverage dipole–dipole interactions, achieving long-range order and organization (Figure 17a).141 They observe a broad distribution of polymer aggregates by dynamic light scattering (DLS), which increase in size and become more uniform upon thermal annealing in chloroform. Both variable temperature 1H NMR spectroscopy (Figure 17b) and DLS (Figure 17c) suggest that while small structural changes occur, the strong π–π stacking interactions between merocyanine pendents sustain the spherical aggregates at elevated temperatures. However, the introduction of a small amount of THF was able to disrupt the antiparallel merocyanine stacking.141 Meanwhile, Xu et al. developed a stimuli-responsive supramolecular polymer by appending urea to 2,3,2′,3′-tetrahydro-[1,1’]biindenylidene.142 The biinidenylene undergoes a cis–trans isomerization upon irradiation with 385 nm light, which is reversed with 365 nm light. The urea pendents intramolecularly hydrogen bond in the cis conformation, but intermolecularly hydrogen bond when isomerized to the trans conformation, yielding a gel.142 Although not explicitly mentioned, these supramolecular constructs are likely to enhance electric fields across the materials through enhanced crystallinity.

Figure 16.

A depiction of the dipole–dipole driven dimerization of merocyanine molecules. Reprinted (adapted) with permission from Würthner, F. Dipole–dipole interaction driven self-assembly of merocyanine dyes: from dimers to nanoscale objects and supramolecular materials. Acc. Chem. Res.2016, 49, 868–876. Copyright 2016 American Chemical Society

Figure 17.

(a) Merocyanine containing block copolymer and its resulting aggregates. Variable temperature NMR (b) and DLS (c) analysis of aggregate 2. Reprinted (adapted) with permission from Rajak, A.; Das, A. Programmed macromolecular assembly by dipole–dipole interactions with aggregation-induced enhanced emission in aqueous medium. ACS Polym. Au2022, 2, 223–231. Copyright 2022 American Chemical Society.

Korevaar et al. designed a dynamic supramolecular helical polymer, wherein the helicity is kinetically gated.143 Their S-chiral oligo(p-phenylenevinylene) (SOPV), first forms dimers through hydrogen bonding, followed by small disordered aggregates that propagate to form M- or P-helices, assembled through π–π stacking interactions of the aromatic core. M-helices can be converted to P-helices upon addition of S-chiral dibenzoyl tartaric acid with gentle heating, and subsequently cooling to 0 °C. The opposite transformation can be achieved through heating P-helices above 25 °C.143 Kulkarni et al. investigated dynamic helicity as well through solvent clathrate interactions.144 The cornonene bisimides assemble through π–π stacking as well. Without chiral substituents, the supramolecular polymer only formed a helix in the presence of n-heptane, which was shown to bind in between the alkyl pendents. This effect was temperature dependent, forming P-helices at (relatively) higher temperatures (−5 °C) and M-helices at lower temperatures (below −30 °C).144

Supramolecular block copolymers can also be formed, as demonstrated by Wagner et al.145 This was achieved by leveraging electron-rich and electron-deficient PDIs to favor π–π stacking between them (Figure 18a). Similarly, Adelizzi et al. designed supramolecular block copolymers with boron and nitrogen cores (Figure 18b).146 These supramolecular copolymers exhibited interesting optical properties. However, considering the electric field improvements reported in Section 3.2, these constructs could also yield higher electric fields owing to increased order afforded by favorable B ← N interactions, as well as the resultant B–N bond dipole. Liao et al. investigated alternating supramolecular copolymers, highlighting the versatility of accessible supramolecular assemblies.147 They achieved this by using anthracene and tetracene based π-cores with R- and S- chiral substituents respectively, forming through a combination of π–π stacking interactions and steric clash to drive the alternating supramolecular polymer.

Figure 18.

(a) NDI-based supramolecular block copolymers with different subtituents to tune their electronic structure, where the green structures are methoxy-substitued and the red block are chloro-substituted. Reprinted (adapted) with permission from Wagner, W.; Wehner, M; Stepanenko, V.; Würthner, F. Supramolecular block aopolymers by seeded living polymerization of perylene bisimides. J. Am. Chem. Soc.2019, 141, 12044–12054. Copyright 2019 American Chemical Society. (b) B–N interaction based supramolecular block copolymers. Reprinted (adapted) with permission from Adelizzi, B.; Chidchob, R.; Tanaka, N.; Lamers, B.A.G.; Meskers, S.C.J.; Ogi, S.; Palmans, A.R.A.; Yamaguchi, S.; Meijer, E.W. Long-lived charge-transfer state from B–N frustrated lewis pairs enchained in supramolecular copolymers. J. Am. Chem. Soc.2020, 142, 16681–16689. Copyright 2020 American Chemical Society.

Despite the reliance on dipole or π−π stacking interactions in the structure of supramolecular polymer networks, they are seldom studied in the context of electric fields. Future work leveraging these effects may be beneficial in improving the performance of devices using, identifying new applications for, or aiding in the synthesis of supramolecular polymers.

4. Novel Polymer Classes to Enhance Electric Fields

In this section, we review emerging ideas to enhance electric fields in polymeric systems, including the incorporation of polyelectrolytes, ferroelectric, piezoelectric or polaron-conducive polymers. Although not directly designed to enhance electric fields, these innovative materials have the potential to make significant advances in that space. The papers reviewed here provide a starting point for future work focused on optimizing electric fields in polymeric materials.

4.1. Nonconjugated Polyelectrolytes

In Section 3, we discussed how conjugated polyelectrolytes could make efficient interlayers in electronic devices, boosting device performance by enhancing built-in electric fields. Here, we discuss nonconjugated polyelectrolytes in a solid state application and beyond, as they are also natural candidates for electric field analyses due to their inherent charges. For example, Qi et al. demonstrated that utilizing chitosan as a polyelectrolyte hydrogel boosted heavy metal removal through interfacial and built-in electric fields.148 The electric fields, generated by the counterions, allowed for diffusion and rapid removal of heavy metal pollutants. They found that gradient hydrogels prepared with acrylamide, protonated chitosan, and UiO-66 MOFs improved performance compared to traditional hydrogels containing acrylamide, neutral chitosan, and UiO-66 MOFs (Figure 19).148 However, poor adsorption of heavy metals was observed in high ionic strength media due to Debye screening. They addressed this issue in a follow-up study, opting for further optimization through the tuning electrostatic interactions.149 They fabricated a salt-tolerant gradient hydrogel, poly[(3-acrylamidopropyl)trimethylammonium chloride-benzyl acrylate] (P(APTC-BZA)), whose built-in potential maintained around 130 mV at NaCl concentrations up to 700 mM. The removal efficiency of Sb(V) only decreased from 69% at 0 mM NaCl, to 55% at 500 mM NaCl, with an initial concentration of 0.5 mg L–1 of Sb(V). In comparison, hydrogels made with gradient salt-intolerant P(APTC) decreased from 38% at 0 mM NaCl, to 10% at 500 mM NaCl, in the same environment. This study emphasizes the importance of not only enhancing electric fields in polymers, but also the importance of maintaining these fields in a variety of environments.

Figure 19.

Comparisons of anionic heavy metal removal performance by gradient and homogeneous hydrogels, and Sb(V) was selected as model pollutant. (a) Effect of chitosan (CS) concentrations. (b) Effect of initial Sb(V) concentrations. (c) O 1 s and Sb 3d XPS spectra of gradient hydrogel after eliminating of Sb(V) where HD is higher (network) density, and LD is lower density. (d) Effect of ionic strength. (e) Effect of pH values. (f) Removal kinetics. Reproduced with permission from ref (148). Copyright 2022 Elsevier.

Wang et al. developed gradient p-polyanion/n-polycation heterojunction hydrogels with built-in electric fields in regards to self-powered iontronic devices.150 The gradient hydrogels were created from the same materials used to synthesize conventional homogeneous hydrogels, poly(acrylamide-2-acrylamide-2-methylpropane sulfonic acid) (P(AM-co-AMPS)) and poly(acrylamide-2-methylpropane acryloyloxyethyl trimetyl ammonium chloride (P(AM-co-ATAC)). The gradient was prepared by applying an external electric field to assist free radical polymerization and to allow migration of the AMPS toward the anode in the polycation gel to create gradient P(AM-co-AMPS) and ATAC toward the cathode in the polyanion gel to create gradient P(AM-co-ATAC). They combined the two gels at the low density sides of each gradient to create their overall hydrogel (Figure 20). When comparing the gradient ionic diode-based device with devices using the conventional homogeneous hydrogels, the output voltage increased from 4.1–135 mV in homogeneous hydrogels, to 306.35 mV in their gradient hydrogel device. Power density and pressure-perception sensitivity of their devices also increased by 162.76% and 128.71% (to 50.16 μW cm–2 or 250.8 μW cm–3 and 43582 mV MPa–1), respectively.

Figure 20.

Schematic depiction of (a) conventional ionic diode, (b) gradient ionic diode, (c) simultated potential profile within conventional ionic diode and (d) gradient ionic diode. Reproduced with permission from ref (150). Copyright 2024 John Wiley and Sons.

Polyelectrolytes also exhibit utility in altering the dynamics of water at interfaces. He et al. studied the effects of diffused counterions on heterogeneous ice nucleation (HIN) using polyelectrolyte brushes (PB).151 By soaking the PB surface in a solution of anionic or cationic counterions, the PB could be reversibly converted to the cationic poly[2-(methacryloyloxy)-ethyltrimethylammonium] (PMETA) or anionic poly(3-sulfopropyl methacrylate) (PSPMA), respectively (Figure 21). They found that the HIN temperature trend with anionic counterions (SO2–4 < F– < Ac– < HPO2–4 < Cl– < Br– < SCN– < NO3– < I–) nearly followed the Hofmeister series when using PMETA as the PBs. For example, when switching the counterions from I– to SO2–4, the HIN temperature dropped from −23.8 °C to −26.4 °C. To investigate this trend further, they performed MD simulations with three representative anions, F–, Cl–, and I–. Although the electric fields at the brush/water interface induced by the counterions (with magnitudes of 100–1000 kV cm–1) matched the trend of HIN temperatures, the magnitudes were deemed not great enough to significantly impact HIN as the required electric field magnitude to induce ice nucleation is on the order of 10000 kV cm–1. Instead, electric fields played an indirect role with stronger electric fields generated by thicker PBs imposing higher attractive potential on the counterions, preventing them from escaping into the brush/water interface. This effect is more pronounced in weakly hydrated ions like I–.151 With the subsequent increase in anion charge density, the orientation relaxation of water molecules at the interface decays more slowly with PMETA-I and PMETA-Cl having 8% and 6% more ice-like water molecules than PMETA-F.151 The investigation of polyelectrolyte effects on HIN by He et al. exemplifies analysis of the interplay between electric fields and another property, ion density in this case, that offers insight on an elusive phenomenon.

Figure 21.

Illustration of HIN on cationic and anionic PB surfaces with different counterions. The counterions on the PMETA and PSPMA brush surfaces can be successfully exchanged by immersing the brush surface into a solution containing expected counterions. Reproduced with permission from ref (151). Copyright 2016 The American Association for the Advancement of Science.

Wei et al. studied tuning friction using PBs that experience conformational changes in response to counterions (Figure 22).152 Friction coefficients increased from orders of 10–3 to 10° depending on the counterion.152 The PBs contained charged groups that generated internal electric fields, influencing interactions between the PBs and the counterions. The internal electric fields also modulated the distribution and orientation of water molecules within the brush, further contributing to the conformational changes in the PBs. The size, hydration, and polarizability of the counterions determined the strength of the ion-pairing interactions where hydrophobic counterions, such as TFSI–, weakened the internal electric fields through formation of stronger ion pairs. This led to a collapse of the polymer chains and an increase in the friction coefficient. Hydrated ions, such as Cl–, contrastingly allowed the PBs to remain extended and hydrated, allowing for low friction coefficients. This study provides an example of how electric field tuning influences polyelectrolyte properties and structure to create materials with tailored characteristics.

Figure 22.

Illustration showing the conformational changes in the PBs induced by counterions. Reproduced with permission from Wei, Q.; Cai, M.; Zhou, F.; Liu, W. Dramatically tuning friction using responsive polyelectrolyte brushes. Macromolecules2013, 46, 9368–9379. Copyright 2013 American Chemical Society.

4.2. Ferroelectric Polymer Additives

Ferroelectric polymers, which have been polarized through cosolvent recrystallization without a poling process, have been studied by Kumari et al. for their ability to increase halogen-free organic solar cell efficiency through induced built-in electric fields.10 Ferroelectric materials feature spontaneous polarization that can be switched by applying an external electric field.10,153,154 They found that through the induction of polarization by polyvinylidene difluoride (PVDF)-based ferroelectric additives in o-xylene/N-methylpyrrolidone (NMP), high efficiencies were attained, 11.02% and 11.76% for fullerene (PTB7-Th:PC71BM) and nonfullerene (PM6:IT-4F) bulk-heterojunction solar cells, respectively.10 They also extended the use of ferroelectric additives to a p-n-like bilayer solar cell, demonstrating an efficiency of 11.83%.10 In the process of ferroelectric polarization, Kumari et al. saw enhancements of photovoltaic properties such as short-circuit current density (Jsc) and fill factor (FF) as summarized in Table 2. The ferroelectric additives improved PCE with the exception of P1 where using NMP alone exhibited better performance. The worsening in the performance was attributed to aggressively large aggregation in OSCs with P1 added compared to the other OSCs.

Table 2. Summary of Device Parameters for Bulk-Heterojunction (BHJ) OSCs with and without PVDF-Based Ferroelectric Additives under AM 1.5G Irradiation at 100 mW cm–2a.

| Additive | Concentration | Jsc (mA cm–2) | Voc (V) | FF (%) | PCE (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| As-castb | – | 11.84 ± 0.68 | 0.790 ± 0.005 | 45.3 ± 1.5 | 4.23 ± 0.44 (4.67) |

| NMP onlyb | 3.0 vol % | 19.13 ± 0.30 | 0.796 ± 0.003 | 65.4 ± 0.3 | 9.96 ± 0.24 (10.20) |

| P1b | 1.5 wt % | 19.83 ± 0.36 | 0.803 ± 0.001 | 61.5 ± 0.7 | 9.79 ± 0.31 (10.10) |

| P2b | 1.5 wt % | 20.01 ± 0.29 | 0.810 ± 0.002 | 66.1 ± 0.4 | 10.72 ± 0.30 (11.02) |

| P3b | 2.0 wt % | 19.75 ± 0.32 | 0.794 ± 0.001 | 65.0 ± 0.8 | 10.20 ± 0.30 (10.50) |

| P4b | 1.5 wt % | 19.78 ± 0.31 | 0.805 ± 0.002 | 66.4 ± 0.4 | 10.58 ± 0.25 (10.83) |

| As-castc | – | 17.01 ± 0.15 | 0.829 ± 0.004 | 62.1 ± 1.2 | 8.84 ± 0.20 (9.04) |

| P2c | 1.0 wt % | 18.94 ± 0.15 | 0.829 ± 0.002 | 73.9 ± 0.3 | 11.61 ± 0.15 (11.76) |

Ferroelectric additives are marked in bold. Data corresponds to the average value of 10 devices and deviation from its maximum; data in parentheses corresponds to the maximum values.

PTB7-Th:PC71BM based OSC devices.

PM6:IT-4F based OSC devices. Adapted with permission from ref (10). Copyright 2020 Elsevier.

Yuan et al. also exploited the anomalous photovoltaic effect with ferroelectric polymers, enhancing efficiency in organic solar cells.69 More specifically, they showed that inserting an ultrathin ferroelectric layer in the cell decreased the recombination in the CTE through an augmented electric field, thus increasing the Voc.69 Deng et al. also saw enhanced built-in electric field through the addition of PVDF as a ferroelectric additive into nonfullerene solar cells.153,155 They tested various different active layers such as PM6:Y6, PM6:BTP-eC9, PM6:IT-4F and PTB7-Th:Y6, resulting in an efficiency of 17.72% for a PM6:Y6-based organic solar cell and 18.17% for a PM6:BTP-eC9-based cell, as summarized in Table 3.155 The added electric field promoted exciton separation, charge transport, and improved film morphology, with a mechanistic overview shown in Figure 23.

Table 3. Photovoltaic Performance of the Different Active Layers OSCs with PVDF Additive Treatment under AM 1.5 G Illumination at 100 mW cm–2.

| Active layers | PVDFa | Voc (V) | Jsc (mA cm–2) | Jcalsc (mA cm–2) | FF (%) | PCE (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PM6:Y6 | – | 0.852 | 25.62 | 24.87 | 73.43 | 15.92 ± 0.08 (16.03) |

| 1 wt % | 0.860 | 25.96 | 25.22 | 75.86 | 16.78 ± 0.12 (16.95) | |

| 5 wt % | 0.862 | 26.81 | 26.10 | 76.66 | 17.59 ± 0.11 (17.72) | |

| 10 wt % | 0.862 | 26.19 | 25.48 | 76.09 | 17.09 ± 0.08 (17.18) | |

| PM6:BTP-eC9 | – | 0.840 | 26.58 | 26.01 | 77.22 | 17.14 ± 0.17 (17.25) |

| 1 wt % | 0.839 | 27.01 | 26.41 | 78.09 | 17.51 ± 0.14 (17.69) | |

| 5 wt % | 0.842 | 27.16 | 26.68 | 79.46 | 17.95 ± 0.15 (18.17) | |

| 10 wt % | 0.840 | 27.12 | 26.57 | 78.56 | 17.71 ± 0.13 (17.89) | |

| PM6:IT-4F | – | 0.851 | 20.14 | 19.60 | 75.53 | 12.62 ± 0.25 (12.94) |

| 1 wt % | 0.860 | 20.89 | 20.26 | 77.04 | 13.57 ± 0.23 (13.84) | |

| 5 wt % | 0.859 | 21.10 | 20.42 | 76.75 | 13.68 ± 0.16 (13.91) | |

| 10 wt % | 0.853 | 20.62 | 20.19 | 76.95 | 13.32 ± 0.19 (13.53) | |

| PTB7-Th:Y6 | – | 0.627 | 24.71 | 23.96 | 66.07 | 10.12 ± 0.11 (10.23) |

| 1 wt % | 0.632 | 25.44 | 24.80 | 66.99 | 10.57 ± 0.15 (10.77) | |

| 5 wt % | 0.632 | 25.85 | 25.11 | 67.77 | 10.89 ± 0.15 (11.07) | |

| 10 wt % | 0.631 | 25.14 | 24.41 | 68.85 | 10.77 ± 0.12 (10.92) |

Polarized at 1.5 V for 2 min. The values in parentheses stand for the maximum PCEs out of 20 devices. Adapted with permission from ref (155). Copyright 2022 John Wiley and Sons.

Figure 23.

Scheme showing (a) the polymer structures and (b) energy transfer processes where the orange solid lines represent acceleration, and the blue dashed lines represent inhibition. Adapted with permission from ref (155). Copyright 2022 John Wiley and Sons.

Meanwhile, Zhang et al. used polarized ferroelectric polymers including polyvinylidene difluoride-trifluoroethylene polymer (PVDF-TrFE) to reduce recombination in perovskite solar cells. They were able to achieve a PCE of 21.38% and a Voc of 1.14 V when applying a 2.0 V μm–1 external electric field with optimal directionality using P(VDF-TrFE) as an interlayer and integrating methylammonium lead iodide (MAPbI3) in the active layer. With the same electric field applied, the ferroelectric-doped active layer alone improved the short-circuit current (Jsc) to 22.92 mA cm–2 and PCE to 19.19% from 22.80 mA cm–2Jsc and 19.18% PCE without the dopant.156 Without an external electric field, the doped layer exhibited 1.08 V Voc, 22.53 mA cm–2Jsc, 0.75% fill factor (FF), and 18.17% PCE while the undoped device exhibited a Voc, Jsc, FF, and PCE of 1.06 V, 22.22 mA cm–2, 0.73%, and 17.21%, respectively.156 Not only did the ferroelectric polymers regulate nonradiative recombination, they also improved the crystallization of the MAPbI3 layer.

Lee et al. also modulated light emission leveraging built-in electric potentials that arose from the nonvolatile polarization of PVDF-TrFE as a polymer film.157 Their device is designed to operate under an alternating, rather than direct, current due to the insulating properties of the ferroelectric layer.153,157,158 This allows for efficient charge carrier injection and light emission upon exciton recombination.157 PVDF-TrFE was also used by Nalwa et al., who showed that device efficiency was improved (2.5% to 3.9%) through higher Jsc (9.6 mA cm–2 to 11.3 mA cm–2) and FF (48% increased to 60%) when including 10 wt % PVDF-TrFE in the bulk of the active layers.159

4.3. Piezoelectric Polymers

The piezoelectric effect refers to a material becoming electrically polarized in response to mechanical stress. The magnitude of a material’s piezoelectricity is represented by piezoelectric coefficicents dij. In this notation, i and j range from 1 to 6 for compression in the x-, y-, and z-axes (1–3) as well as the sheer of their respective axes (4–6). Further, j refers to the direction of mechanical action and i refers to the direction of the resulting electric field.160 The most commonly reported piezoelectric coefficients are d31 (transverse mode) and d33 (compression mode) and is expressed in units of C/N.

While commonly observed in ceramic materials,161 polymers have become increasingly popular in the study and development of piezoelectric materials owing to their flexibility and ease of processing.160,162,163 Monomers with a strong intrinsic dipole moment are frequently used to synthesize piezoelectric polymers. Examples of common piezoelectric polymers are poly(vinylidene difluoride) (PVDF) and odd-numbered Nylons (ie. Nylon-7 and Nylon-11). The collective monomer dipole moment grows with the polymer chain, resulting in a small-scale electric field. In this subsection we begin by highlighting background on piezoelectric polymers to contextualize later examples of their emerging applications.

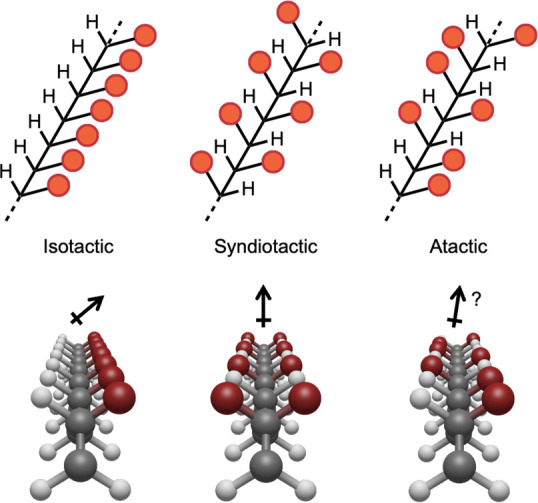

PVDF possesses a C–F rich backbone, which gives rise to its piezoelectric response. While first mentioned by Kawai in 1969,164 Kepler and Anderson reported important mechanistic insight into the piezoelectricity of PVDF.165 They observed an inverse piezoelectric response by applying a voltage to the film and measuring the change in thickness, yielding a d33 coefficient of −31.5 pC/N. Odd-numbered nylons (Nylon-7, Nylon-11), are another common piezoelectric polymer. Even-numbered nylons like Nylon-6 are not piezoelectric owing to their amides generally facing opposite directions in a minimized structure as shown in Figure 24. Naturally occurring biopolymers like wood166 and collagen167 have demonstrated piezoelectricity as well, further expanding the variety of available piezoelectric polymers.

Figure 24.

Bond-line structures of Nylon-6 and Nylon-7, highlighting the carbonyl dipoles and their effect on the net polymer dipole.

Exemplifying this, Newman et al. calculated the dipole density of Nylon-11 to be 1.5 D/100 Å3,168 using a structure reported from their previous work.169 They measured a d31 piezoelectric coefficient of 3.2 pC/N,168 which is notably less than PVDF (d31 = 21.4 pC/N).165 More recently, Adjokatsse et al. simulated structures of Nylon-11, −7, and −5, calculating the dipole densities to be 1.34, 2.06, and 2.94 D/100 Å3, respectively.170 This makes sense as shorter alkyl spacers bring the carbonyls in closer proximity, and this also agrees well with the predicted 1.5 D/100 Å3 for Nylon-11 nearly 30 years prior.168

While the piezoelectric coefficients for PVDF, and more notably odd-numbered nylons, are less than common piezoelectric ceramic materials (ie. BaTiO3d31 = −79.1 pC/N, d33 = 191 pC/N),171 they are still sufficiently strong for use in devices. For example, Wang et al. leveraged the piezoelectricity of PVDF to catalyze the degradation of antibiotics in water.172 They designed a ZnO/Carbon quantum dot (CQD)/PVDF composite pipe. Water flowing through the pipe generated pressure on PVDF and polarized it, which facilitated the ZnO/CQD to generate radical species from water to degrade tetracycline (Figure 25).172 This material was shown to have its own antibacterial properties as well.

Figure 25.

Schematic depiction of the piezocatalyzed degradation of tetracycline by ZnO/CQD. Reprinted with permission from ref (172). Copyright 2023 Elsevier.