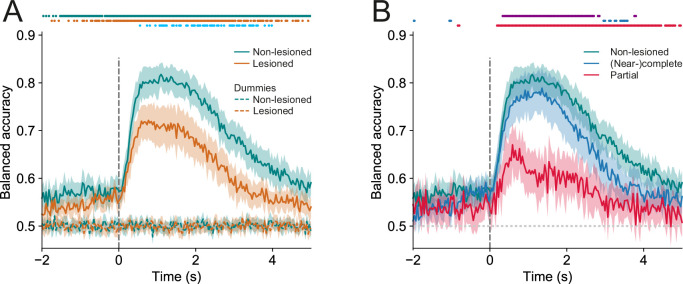

Figure 6. Trial outcomes can be accurately decoded from neural activity in lesioned and non-lesioned mice.

(A) Average decoding accuracy of logistic regression models as a function of time against dummy models with a score of 0.5 meaning chance performance and a score of 1 being the maximum. Data shown depict the mean model accuracy across 37 (lesioned) and 38 (non-lesioned) sessions, respectively. Dots at the top indicate the time points (frames) where the model performance was significantly different between trained and dummy models for non-lesioned mice (teal) or lesioned mice (orange) (p<0.05, one-sided Wilcoxon signed-rank test or paired t-test with Bonferroni correction, depending on whether normality assumption was met), and between the trained models for non-lesioned vs lesioned mice (blue) (p<0.05, one-sided Mann-Whitney U test or t-test with Bonferroni correction, depending on whether normality assumption was met). (B) Same as (A) but the average model accuracy is plotted separately for mice with (near-)complete (22 sessions) and partial lesions (15 sessions). Dots at the top indicate the time points where the model performance was significantly different between partial vs (near-)complete mice (purple), (near-)complete vs non-lesioned mice (blue), and partial vs non-lesioned mice (red) (p<0.05, one-sided Mann-Whitney U test or t-test with Bonferroni correction, depending on whether normality assumption was met). Shaded areas represent 95% confidence intervals.