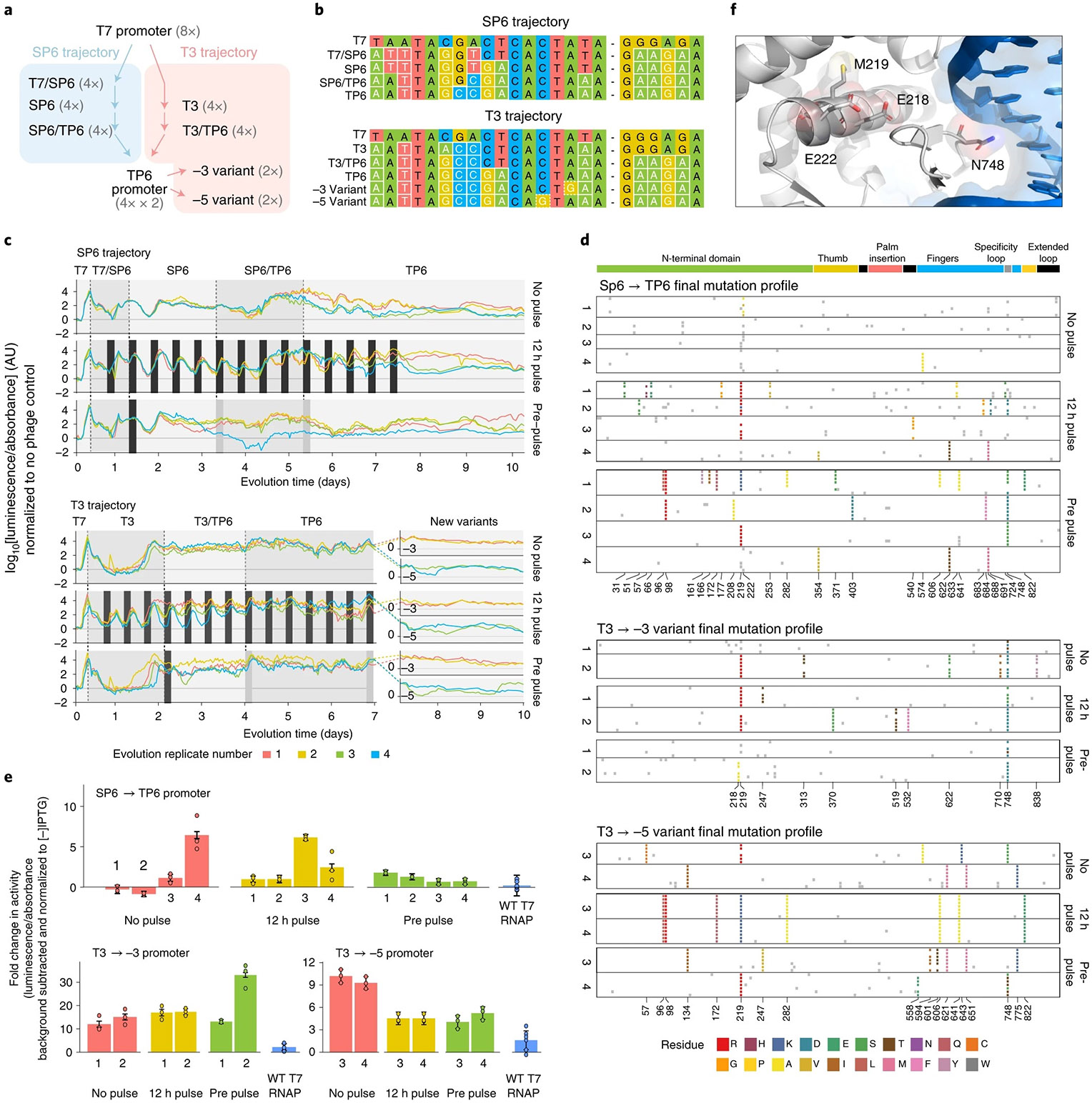

Fig. 6 ∣. Long-term evolution.

a, Thirty-two populations of phage encoding T7 RNAP were evolved to bind new promoters. Evolution proceeded first along two different paths, being challenged to bind either SP6 or T3-derived promoters. All populations were then evolved to bind the TP6 promoter. The 16 populations that traversed the T3 path were then split in half and challenged to bind novel promoters with mutations at highly conserved −3 or −5 locations. b, Genotypes of the promoters used in this evolution. Changes from the WT T7 promoter are highlighted. c, Real-time monitoring of the 48 populations undergoing three different stringency management schemes in which psp-pIII bacteria are periodically spiked into populations for 3-h intervals (dark gray bars) to increase population size. d, Genotypes of subclones obtained from each population (replicate populations labeled 1–4) from each evolution trajectory with each of the three stringency management schemes. Dominant (>50% of population) variants are highlighted and colored by their AA mutation. Nondominant (that is background mutations) are shown in light gray. The x axis is annotated by dominant mutations that appear within a given trajectory. e, Normalized luciferase activity of individual subclones from populations (1-4) from each trajectory, compared to WT T7 RNAP (blue). Luciferase reporter vectors are driven by the TP6 promoter, −3 variant promoter and −5 variant promoters. Data are presented as mean values ± s.e.m. for n = 3 biologically independent samples. Genotypes of subclones are listed in Supplementary Table 3. f, E218, M219 and E222 in the WT T7 RNAP structure (PDB 1CEZ, ref. 46), near the promoter specificity loop.