Abstract

Background and aims

The objective of this study was to assess the associations of birth weight with cardiac structure and function in adults with dextro-transposition of the great arteries (D-TGA) who underwent the arterial switch operation (ASO).

Methods and results

Thirty-nine ASO patients (age 24.4 ± 3.3 years) were included during routine clinical follow-up from July 2019 to December 2021. All patients underwent cardiopulmonary exercise testing and cardiac magnetic resonance imaging at rest and during exercise. Early-life characteristics, including birth weight, were extracted from electronic medical health records. Linear regression analysis showed that lower birth weight was associated with smaller left ventricular (LV) and right ventricular (RV) end-diastolic volume index (LV: −14.5 mL/m2 [95 % confidence interval, CI: −26.5 to −2.5] per 1-kg decrease in birth weight, p = 0.04; RV: −11.2 mL/m2 [-20.7 to −1.7] per 1-kg decrease in birth weight, p = 0.03). Lower birth weight was associated with greater LV and RV ejection fraction at rest (LV: +8.5 % [+4.4 to +12.5] per 1-kg decrease in birth weight, p < 0.001); RV: +8.1 % [+2.8 to +13.4] per 1-kg decrease in birth weight, p = 0.005). Furthermore, lower birth weight was associated with an attenuated increase in LV stroke volume index from rest to peak exercise (−5.2 mL/m2 [-9.3 to −1.2] per 1-kg decrease in birth weight, p = 0.02).

Conclusions

Birth weight may be a novel risk factor for adverse cardiac remodeling in adult ASO patients. Further research is needed to delineate the mechanisms underlying the associations between birth weight and cardiac remodeling ASO patients as well as the broader adult CHD population.

Keywords: Cardiac remodeling, Congenital heart disease, Magnetic resonance imaging, Prematurity, Transposition of the great arteries, Arterial switch operation, Exercise

Graphical abstract

Abbreviations

- ASO

arterial switch operation

- BSA

body surface area

- CHD

congenital heart defect

- CI

confidence interval

- CMR

cardiac magnetic resonance

- CPET

cardiopulmonary exercise testing

- D-TGA

dextro-transposition of the great arteries

- EDVi

end-diastolic volume indexed to body surface area

- ESVi

end-systolic volume indexed to body surface area

- IQR

interquartile range

- LV

left ventricle or left ventricular

- RV

right ventricle or right ventricular

- SVi

stroke volume indexed to body surface area

1. Introduction

Dextro-transposition of the great arteries (D-TGA) occurs in 0.2 per 1000 live births and accounts for 5–7% of all CHDs, constituting one of the most prevalent cyanotic congenital heart defects (CHDs) worldwide [[1], [2], [3], [4]]. In D-TGA, the aorta arises from the morphological right ventricle (RV), while the pulmonary artery arises from the morphological left ventricle (LV) [5]. This circulation carries a 90 % risk of mortality during the first year of life if left unpalliated and therefore requires neonatal surgery.[6] The surgical treatment of choice – the arterial switch operation (ASO) – involves repositioning the great arteries and reimplanting the coronary arteries to restore the function of the LV as the systemic ventricle [7,8]. Although associated with good long-term survival, a large proportion of patients suffer from increased hemodynamic burden, develop LV or RV dysfunction, and require reinterventions over time [7,9,10].

In order to improve outcomes for ASO patients, it is crucial to implement risk stratification, optimize follow-up, and incorporate targeted treatment strategies. While the risk factors for early postoperative outcomes have been described extensively, it remains uncertain which D-TGA patients after ASO would benefit the most from targeted follow-up into adulthood. One possible long-term risk factor is low birth weight (<2.5 kg), which affects approximately 10 % of all patients with D-TGA [11,12]. Although the associations between low birth weight and short-term mortality and morbidity are well-described [[13], [14], [15]], the long-term effects remain unexplored.

Preterm birth (<37 weeks of gestation) and low birth weight have both been associated with altered cardiac structure and function that reach into adulthood in the general population [[16], [17], [18]]. These alterations include smaller LV and RV volumes [[19], [20], [21], [22], [23]], LV diastolic dysfunction [20,24], RV systolic dysfunction [20,25], and increased myocardial fibrosis [24]. Recent evidence from children with a functional single right ventricle also suggests that CHD patients born preterm may demonstrate changes in cardiac structure in comparison with those born at term [26]. Whether prematurity and low birth weight are associated with an altered cardiac phenotype in adult CHD patients – including D-TGA after ASO – remains unknown. To address these knowledge gaps, we leveraged cardiac magnetic resonance (CMR) imaging in a cohort of ASO patients to assess whether birth weight is associated with cardiac structure and function at rest and during exercise in this high-risk population.

2. Methods

2.1. Study population

As described previously [27], all ASO patients who visited the adult congenital heart disease clinic of UZ Leuven (Leuven, Belgium) between July 2019 and December 2021 were consecutively invited to participate in the present study. Patient inclusion was discontinued during the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020 and resumed in December 2020 [28]. Patients with Taussig-Bing anomaly or congenitally corrected transposition of the great arteries were excluded, as were pregnant patients, patients with a pacemaker or implantable cardioverter defibrillator, and patients with other contraindications to CMR imaging. All included patients underwent cardiopulmonary exercise testing (CPET) and CMR imaging at rest and during exercise. To ensure all patients were able to provide maximal exercise efforts, the study was organized using a two-day protocol with CPET on day 1 and CMR imaging on day 2. The Ethics Committee of UZ/KU Leuven approved the study (S62434). The study protocol adhered to the Declaration of Helsinki, and written informed consent was obtained from all study participants.

2.2. Data collection

2.2.1. Exposures

The primary exposure was birth weight as a continuous variable. In addition, each participant was categorized as having low birth weight (<2.5 kg) or normal birth weight (≥2.5 kg) [29]. Because the low birth weight group consisted of only 3 participants, direct group comparisons of low vs. normal birth weight patients were considered exploratory. In addition, as birth weight is determined by both gestational age and birth weight percentile corrected for gestational age and sex (i.e., intrauterine growth), both were tested as secondary exposures. Each patient's birth weight and gestational age were verified using birth records obtained from electronic medical health records. Birth weight percentiles adjusted for sex and gestational age were calculated using reference values from the INTERGROWTH-21st project [30].

2.2.2. CMR acquisition

CMR was performed using a 1.5-T magnetic resonance imaging scanner (Achieva, Philips Medical Systems, Best, The Netherlands). For each participant, short-axis and horizontal long-axis steady‐state free precession cine images with cardiac gating were acquired. Ventricular volumes were delineated using short‐axis images, and trabeculations and papillary muscles were included in the blood pool. CMR variables included LV and RV volumes, ejection fraction, and cardiac index. All volumes (end-diastolic volume [EDV], end-systolic volume [ESV], and stroke volume [SV]) were indexed to body surface area (BSA; indicated by the suffix -i). Cardiac index was defined as the product of SVi and heart rate.

In addition to the resting exam, all participants underwent exercise CMR imaging. All patients performed a supine bicycle stress test during which images were obtained using real-time CMR imaging. It was previously demonstrated that 66 % of maximal power output closely corresponds to the maximal sustainable exercise intensity in a supine position during CMR imaging [31,32]. Consequently, exercise CMR efforts at 66 % of maximal power output were defined as "peak intensity" and were used in the acquisition of exercise CMR images. All resting and exercise CMR imaging studies were analyzed using the in-house developed software RightVol (KU Leuven, Leuven, Belgium) [31].

2.2.3. Cardiopulmonary exercise testing

All participants underwent CPET using a graded exercise protocol on an upright cycle ergometer. CPET was discontinued upon exhaustion. The graded exercise protocol consisted of a baseline workload of 20W and gradually increased by 20W per minute [34]. Breath‐by‐breath analyses provided estimates of peak oxygen consumption (VO2), the ventilatory equivalent for carbon dioxide (VE/VCO2 slope), and maximal workload. Oxygen pulse was defined as the ratio of oxygen consumption (VO2) to heart rate. Peak VO2 was also expressed as a percentage of the predicted peak VO2, calculated using the Wasserman equation, and was used as a measure of exercise performance. In addition, anaerobic threshold, maximal heart rate, systolic and diastolic blood pressure at rest and peak exercise, and oxygen pulse were also collected and analyzed.

2.3. Statistical analysis

Baseline and outcome data were summarized for the entire cohort and stratified by birth weight (low vs. normal birth weight). Continuous variables were tested for normality using the Shapiro-Wilk test. Normally distributed variables were presented as mean ± standard deviation while skewed variables were presented as median (interquartile range, IQR). Categorical variables are expressed as frequency (percentage).

Linear regression was used to examine the associations of birth weight as a continuous variable with CMR and CPET variables; unstandardized regression coefficients (B) are presented with corresponding 95 % confidence intervals (CIs). Pearson's and Spearman's correlations were calculated to assess the correlations of birth weight as a continuous variable with parametric and nonparametric variables, respectively; correlation coefficients (R) are presented with corresponding p-values. In exploratory analyses, direct group comparisons were carried out using parametric (t-test) or nonparametric (Kruskal-Wallis) tests, as appropriate, for continuous variables, and using Χ2-test or Fisher exact tests, as indicated, for categorical variables. Additional exploratory analyses to estimate the independent effects of birth weight on CMR indices were carried using multivariable-adjusted linear regression models with sex, age, and BMI as covariates. Post-hoc power analyses (G*Power, version 3.1.9.7) revealed that effect sizes of |r|>0.42, d > 1.52, d > 2.06, and w > 0.58 were needed to achieve statistical significance for continuous bivariate correlation tests, continuous parametric independent group tests, continuous non-parametric independent group tests, and categorical independent group tests, respectively. All analyses were performed using R Statistical Software (version 4.1.3, Foundation for Statistical Computing). A 2-tailed p-value ≤0.05 was considered statistically significant throughout.

3. Results

3.1. Patient characteristics

As reported previously [27], a total of 106 patients were consecutively screened for study participation. Of those, 52 patients met the inclusion criteria. Eight eligible patients refused to participate in the study and five had no information on birth weight, leading to a final study cohort of 39 young adults (age 24.4 ± 3.3 years) who underwent an ASO during the neonatal period. Table 1 shows baseline demographic and perinatal characteristics of the study cohort. Three participants (7.7 %) were born with low birth weight (<2.5 kg; Supplemental Figure 1 and Supplemental Table 1). The median birth weight percentile among ASO patients was 68.1 % (IQR, 48.1–82.7 %). All patients were in NYHA functional class I and the median NT-proBNP level was 58.0 ng/L. One patient with normal birth weight was prescribed angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors, while no one was taking angiotensin receptor blockers or beta-adrenergic antagonists at the study visit.

Table 1.

Demographic and perinatal characteristics. Normally distributed variables were presented as mean ± standard deviation while non-normally distributed variables were presented as median (interquartile range). Categorical variables are expressed as frequency (percentage).

| Variable | ASO patients (N = 39) |

|---|---|

| Demographics/anthropometrics | – |

| Sex, n (%) | – |

| Male | 29 (74.4 %) |

| Female | 20 (25.6 %) |

| Age, years | 24.4 ± 3.3 |

| Height, m | 1.76 (1.67–1.79) |

| Weight, kg | 70.7 ± 14.8 |

| BSA, m2 | 1.84 ± 0.21 |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 23.4 ± 4.1 |

| Associated lesions | – |

| Ventricular septal defect, n | 7 (17.9 %) |

| Atrial septal defect, n | 23 (59.0 %) |

| Patent foramen ovale, n | 3 (7.7 %) |

| Coronary anomalies, n | 10 (25.6 %) |

| Patent ductus arteriosus, n | 33 (84.6 %) |

| Interventions | – |

| Neoaortic valve intervention, n | 1 (2.6 %) |

| Pulmonary valve intervention, n | 12 (30.8 %) |

| Coronary revascularization, n | 0 (0.0 %) |

| Perinatal characteristics | – |

| Time from birth to ASO, days | 8 (6–11) |

| Birth weight, g | 3408 ± 479 |

| Gestational age, weeks | 39 (38–40) |

| Preterm (<37 weeks), n (%) | 3 (7.7 %) |

| Birth weight percentile, % | 68.1 (48.1–82.7) |

ASO indicates arterial switch operation; BMI, body mass index; BSA, body surface area.

3.2. Association of birth weight with cardiovascular magnetic resonance imaging at rest and exercise

Results from correlation analyses in which birth weight was used as exposure and CMR parameters as outcomes are listed in Table 2. Linear regression analyses showed that lower birth weight was significantly associated with smaller LVEDVi and RVEDVi (LV: −14.5 mL/m2 [95%CI, −26.5 to −2.5] per 1-kg decrease in birth weight, R = 0.34, p = 0.04; RV: −11.2 mL/m2 [95%CI, −20.7 to −1.7] per 1-kg decrease in birth weight, R = 0.36, p = 0.03). In addition, lower birth weight was associated with smaller LVESVi and RVESVi (LV: −13.0 mL/m2 [95%CI, −21.1 to −4.9] per 1-kg decrease in birth weight, R = 0.35, p = 0.03; RV: −16.0 mL/m2 [95%CI, −25.9 to −6.1] per 1-kg decrease in birth weight, R = 0.48, p = 0.002), as well as greater LV and RV ejection fraction at rest (LV: +8.5 % [95%CI, +4.4 to +12.5] per 1-kg decrease in birth weight, R = −0.56, p < 0.001); RV: +8.1 % [95%CI, +2.8 to +13.4] per 1-kg decrease in birth weight, R = −0.44, p = 0.005) (Fig. 1). Although birth weight was significantly associated with these measures of LV and RV structure and function, they were still highly variable at any given birth weight (Fig. 1). Multivariable-adjusted models adjusted showed that the associations of birth weight with LVEDVi and RVEDVi, as well as those with LV and RV ejection fraction, were largely independent of age, sex, and BMI (Supplemental Table 2). Even though power was limited in these sensitivity analyses, associations of birth weight with LV and RV ejection fraction were statistically significant. Among different potential confounding factors (i.e., prior defects, prior interventions, and time from birth to ASO), only the presence of an atrial septal defect was associated with LVEDVi, RVEDVi, and LVEF (Supplemental Table 3). Linear regression analyses testing the association of birth weight with the aforementioned measures of cardiac volumes and function found consistent associations throughout (Supplemental Table 4).

Table 2.

Association of birth weight with exercise cardiovascular magnetic resonance imaging parameters in ASO patients. Normally distributed variables were presented as mean ± standard deviation while non-normally distributed variables were presented as median (interquartile range). Categorical variables are expressed as frequency (percentage).

| Variable | At rest |

At peak exercise |

Change from rest to exercise |

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Low birth weight (n = 3) | Normal birth weight (n = 36) | Between-group P-valuea | Correlationb | Low birth weight (n = 3) | Normal birth weight (n = 36) | Between-group P-valuea | Correlationb | Low birth weight (n = 3) | Normal birth weight (n = 36) | Between-group P-valuea | Correlationb | |

| HR, bpm | 80.7 ± 17.5 | 70.3 ± 12.1 | NS |

R = −0.23, p=NS |

161.0 ± 15.6 | 153.4 ± 20.6 | NS |

R=-0.11, p=NS |

79.0 (78.0–82.0) | 87.5 (72.8–99.2) | NS |

R=0.03, p=NS |

| LVEDVi, mL/m2 | 73.1 (65.5–75.8) | 87.9 (79.3–97.6) | 0.05 |

R = 0.34, p=0.04 |

66.0 (61.1–72.5) | 86.3 (80.1–97.6) | 0.03 |

R=0.37, p=0.02 |

−2.8 ± 3.9 | −0.9 ± 2.1 | NS |

R=0.14, p=NS |

| LVESVi, mL/m2 | 28.0 (20.4–28.4) | 39.2 (34.8–44.9) | 0.02 |

R = 0.35, p=0.03 |

18.7 ± 10.2 | 28.0 ± 11.1 | NS |

R=0.29, p=NS |

−5.3 (−6.1 to −3.3) | −10.4 (−15.0 to −8.9) | 0.02 |

R=-0.21, p=NS |

| LVSVi, mL/m2 | 46.6 ± 3.4 | 49.2 ± 8.5 | NS |

R = 0.08, p=NS |

48.5 (43.5–53.3) | 58.2 (51.9–64.8) | NS |

R=0.28, p=NS |

1.8 ± 6.8 | 11.1 ± 5.9 | NS |

R=0.38, p=0.02 |

| LVEF, % | 67.6 ± 9.1 | 55.8 ± 6.4 | NS |

R = −0.56, p < 0.001 |

72.7 ± 14.1 | 69.1 ± 8.2 | NS |

R=-0.30, p=NS |

5.2 ± 6.4 | 13.3 ± 5.6 | NS |

R=0.24, p=NS |

| LVCI, mL/min/m2 | 3.7 ± 0.6 | 3.4 ± 0.7 | NS |

R = −0.10, p=NS |

7.4 (7.2–8.1) | 8.9 (7.6–10.7) | NS |

R=0.19, p=NS |

4.0 ± 1.5 | 5.9 ± 2.0 | NS |

R=0.23, p=NS |

| RVEDVi, mL/m2 | 65.9 ± 8.0 | 86.5 ± 14.4 | 0.03 |

R = 0.36, p=0.03 |

62.5 ± 8.2 | 85.7 ± 14.2 | 0.02 |

R=0.40, p=0.01 |

−1.1 (−5.4 to −0.3) | −0.6 (−1.6 to 0.1) | NS |

R=0.22, p=NS |

| RVESVi, mL/m2 | 22.6 (17.4–24.1) | 36.9 (31.9–44.0) | 0.01 |

R = 0.48, p=0.002 |

15.1 (11.6–20.3) | 27.5 (22.9–37.9) | NS |

R=0.35, p=0.03 |

−4.1 (−5.8 to −2.1) | −8.0 (−11.3 to −5.0) | NS |

R=-0.06, p=NS |

| RVSVi, mL/m2 | 45.7 ± 4.5 | 47.9 ± 7.8 | NS |

R = 0.04, p=NS |

46.2 ± 12.8 | 55.6 ± 7.7 | NS |

R=0.18, p=NS |

0.5 ± 8.8 | 7.7 ± 5.8 | NS |

R=0.20, p=NS |

| RVEF, % | 69.9 ± 8.4 | 56.0 ± 7.9 | NS |

R = −0.44, p=0.005 |

73.5 ± 15.9 | 65.9 ± 10.0 | NS |

R=-0.32 p=0.05 |

3.6 ± 8.8 | 9.9 ± 6.5 | NS |

R=0.08, p=NS |

| RVCI, mL/min/m2 | 3.6 ± 0.5 | 3.3 ± 0.7 | NS |

R = −0.13, p=NS |

7.3 ± 1.5 | 8.6 ± 1.8 | NS |

R=0.10, p=NS |

3.7 ± 1.9 | 5.2 ± 1.5 | NS |

R=0.16, p=NS |

-CI, cardiac index; -EF, ejection fraction.

P-values represents between-group comparisons using parametric (t-test) or nonparametric (Kruskal-Wallis) tests, as appropriate, for continuous variables, and using Χ2-test or Fisher exact test, as indicated, for categorical variables.

P-values are associated with the indicated correlation coefficients (i.e., R).

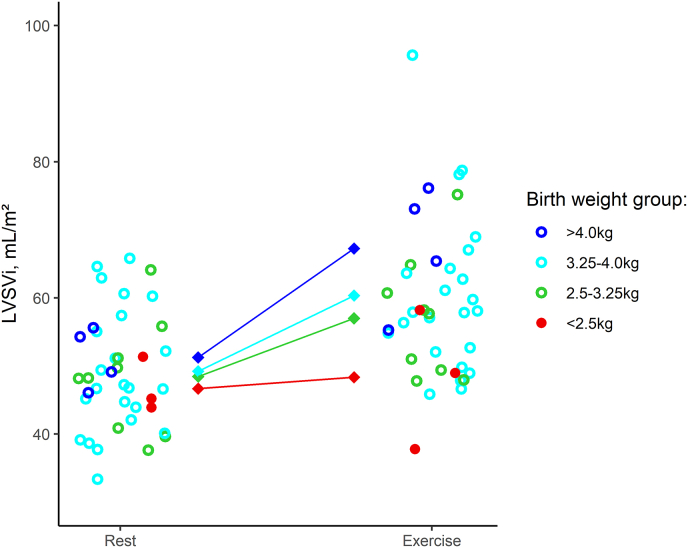

Fig. 1.

Scatter plots demonstrating correlations between birth weight and cardiovascular magnetic resonance imaging parameters at rest. The dots represent the differences in LVSVi from rest to exercise in the individual patients. The line represents the linear regression slope with 95%CI. -EF, ejection fraction.

At peak exercise, lower birth weight was statistically significantly associated with LVEDVi (−15.5 mL/m2 [95%CI, −27.0 to −3.9] per 1-kg decrease in birth weight, R = 0.37, p = 0.02), whereas associations of birth weight with LVESVi (−11.0 mL/m2 [95%CI, −21.9 to −0.2] per 1-kg decrease in birth weight, R = 0.29, p = 0.07) and LV ejection fraction (+5.3 % [95%CI, −0.2 to +10.8] per 1-kg decrease in birth weight, R = −0.30, p = 0.07) attenuated slightly (Fig. 2). In addition, birth weight was significantly associated with RVEDVi (−12.5 mL/m2 [95%CI, −21.8 to −3.2] per 1-kg decrease in birth weight, R = 0.40, p = 0.01), RVESVi (−11.0 [95%CI, −21.9 to −0.2] per 1-kg decrease in birth weight, R = 0.35, p = 0.03), and RV ejection fraction (+7.0 % [95%CI, +0.3 to +13.6] per 1-kg decrease in birth weight, R = −0.32, p = 0.05). Finally, lower birth weight was associated with an attenuated increase in LVSVi from rest to peak exercise (−5.2 mL/m2 [95%CI, −9.3 to −1.2] per 1-kg decrease in birth weight, R = 0.38, p = 0.02) (Fig. 3, Fig. 4).

Fig. 2.

Scatter plots demonstrating the correlations between birth weight and cardiovascular magnetic resonance imaging parameters at peak exercise. The dots represent the differences in LVSVi from rest to exercise in the individual patients. The line represents the linear regression slope with 95%CI. -EF, ejection fraction.

Fig. 3.

Scatter plot demonstrating the correlation between birth weight and change in LV stroke volume index from rest to exercise. The dots represent the differences in LVSVi from rest to exercise in the individual patients. The line represents the linear regression slope with 95%CI.

Fig. 4.

Increase in LV stroke volume index from rest to exercise across different birth weight categories. The circles represent the individual LVSVi values for ASO patients at rest and during exercise. The centrally connected squares represent the mean values for each birth weight group at rest and exercise, respectively.

Since birth weight is determined by gestational age and intrauterine growth (i.e., birth weight percentile corrected for gestational age and sex), secondary analyses consisted of linear regression and correlation analyses in which gestational age and birth weight percentile were used as exposures and CMR parameters as outcomes (Supplemental Figures 2-6). While directions of associations were consistent across the different early-life exposures, the associations between gestational age and indexed LV and RV end-diastolic (LV: −3.9 mL/m2 [95%CI, −7.5 to −0.3] per 1-week decrease in gestational age, R = 0.33, p = 0.06; RV: −3.2 mL/m2 [95%CI, −5.9 to −0.4] per 1-week decrease in gestational age, R = 0.37, p = 0.03) and end-systolic (LV: −3.0 mL/m2 [95%CI, −5.7 to −0.4] per 1-week decrease in gestational age, R = 0.31, p = 0.07; RV: −2.9 mL/m2 [95%CI, −6.2 to −0.4] per 1-week decrease in gestational age, R = 0.21, p = 0.23) volumes at rest were not as strong as those between birth weight and the same parameters. Nevertheless, gestational age was significantly and inversely associated with LV ejection fraction at rest (+1.7 % [95%CI, +0.4 to +3.1] per 1-week decrease in gestational age, R = −0.39, p = 0.02). None of the correlations between birth weight percentile and indexed LV and RV volumes at rest reached statistical significance, except RVESVi, which was higher in those born at the latest gestations (−2.9 mL/m2 [95%CI, −6.2 to +0.4] per 1-week decrease in gestational age, R = 0.42, p = 0.01).

Between-group comparisons of patients with low vs. normal birth weight showed that ASO patients born with low birth weight had smaller LV and RV end-diastolic (LV: median 73.1 vs. 87.9 mL/m2, p = 0.05; RV: mean 65.9 vs. 86.5 mL/m2, p = 0.03) and end-systolic (LV: median 28.0 mL/m2 vs. 39.2 mL/m2, p = 0.02; RV: median 22.6 mL/m2 vs. 36.9 mL/m2, p = 0.01) volumes at rest (Table 1). At peak exercise, their LVEDVi and RVEDVi remained smaller compared to their counterparts with normal birth weight (LV: median 66.0 mL/m2 vs. 86.3 mL/m2, p = 0.03; RV: mean 62.5 mL/m2 vs. 85.7 mL/m2, p = 0.02). The decrease in LVESVi from rest to exercise was more limited in the low-birth-weight group (median −5.3 vs. −10.4 mL/m2, p = 0.02).

3.3. Cardiopulmonary exercise testing

All participants also performed cardiopulmonary exercise testing. The median (IQR) respiratory exchange ratio was 1.20 (1.16 to 1.24), indicating high exercise intensity. Correlation analyses demonstrated that lower birth weight was associated with lower anaerobic threshold (−25.8W [95%CI, −45.7 to −5.9] per 1-kg decrease in birth weight, R = 0.39, p = 0.02), peak power output (−37.6W [95%CI, −69.7 to −5.5] per 1-kg decrease in birth weight, R = 0.35, p = 0.03), and oxygen pulse (−4.2mL/beat [95%CI, −4.2 to −0.6] per 1-kg decrease in birth weight, R = 0.39, p = 0.01) (Supplemental Table 5 and Supplemental Figure 6). This was confirmed by comparisons between ASO patients born at low vs. those born at normal birth weight, as the former group performed significantly worse regarding these measures in comparison with subjects with normal birth weight. There were no associations of lower birth weight with peak VO2 (either in mL/kg/min or as a percent of the predicted value), although lower birth weight was associated with significantly lower oxygen pulse values. Between-group comparisons showed that low vs. normal birth weight subjects had a significantly lower peak VO2 (inmL/kg/min; mean 24.4 vs. 33.4 mL/kg/min, p = 0.03). No significant difference could be observed in peak VO2 expressed as a percent of the predicted value (mean 74.0 vs. 81.2 %, p = 0.68).

4. Discussion

The present study showed that birth weight was significantly associated with indexed LV and RV volumes at rest and during exercise. Indeed, LV and RV volumes were smaller in ASO patients born at lower birth weights, with the most pronounced alterations observed in patients with low birth weight (i.e., <2.5 kg). In addition, lower birth weight was associated with a blunted increase in LVSVi from rest to exercise. These findings indicate that low birth weight is associated with smaller indexed ventricular volumes and an impaired cardiac response to exercise in ASO patients, without significant effects on exercise capacity.

These findings have several implications. First, findings from the current study suggest that early-life factors may affect the cardiac phenotype of ASO patients in adulthood, extending previous findings that individuals without CHD born preterm or with low birth weight have cardiac alterations vs. those born at term or with normal birth weight [16,17,[19], [20], [21], [22], [23]]. These studies indicate that preterm birth and small-for-gestational-age status are associated with smaller indexed LV and RV volumes [17,[19], [20], [21], [22], [23]], which corresponds to findings of the present study. Furthermore, although birth weight did not explain all variance in LV and RV ejection fraction at rest, we still observed strong associations of birth weight with these parameters. This indicates that patient with low birth weight function—on average—had an increased ejection fraction compared to those with normal birth weight. Similarly, prior work has shown that preterm-born adults may exhibit an exaggerated contractile response when exposed to physiologic stress [33]. It has been suggested that this contractile reserve may help compensate the impaired volumetric reserve observed in adults born preterm [17,33]. We also observed that low birth weight subjects had a blunted SVi increase from rest to exercise, corresponding to prior work demonstrating that preterm-born adults demonstrate a blunted response in LV systolic function when exposed to exercise stress [34]. These findings collectively suggest that early-life exposures such as birth weight and gestational age may affect cardiac phenotype in the general as well as adult CHD population.

Second, birth weight may be an early predictor of adverse cardiac remodeling in adult ASO patients. It is well-established that low birth weight is associated with short-term mortality and morbidity in infants who undergo the ASO [[13], [14], [15]]. Although much work has focused on early postoperative outcomes after the ASO, the number of studies investigating risk factors for adverse cardiac remodeling and exercise tolerance in adult ASO patients remains relatively low. Current guidelines do not recommend targeted screening but rather advocate for general surveillance of ASO patients [35,36]. However, incorporating early risk factors in adult risk stratification could inform intensity of follow-up in ASO patients. Although the present study suggests that birth weight may be associated with adverse cardiac remodeling in adult ASO patients, more work is needed to further delineate the cardiovascular outcomes associated with low birth weight and preterm birth, as well as the potential benefits associated with implementing birth weight in the risk stratification of ASO patients.

Third, findings from the present study may spur further research into the long-term consequences of early-life exposures in adult CHD patients. A recent study using data from the Single Ventricle Reconstruction trial has identified preterm birth as a significant risk factor for adverse cardiac remodeling in patients with a functional single right ventricle [26]. Indeed, preterm-born individuals with a functional single right ventricle had significantly lower RVEDVi values at birth, but eventually surpassed their term-born counterparts by 14 months of age. While this secondary analysis was limited by a relatively short follow-up period and could therefore not assess the effects of preterm birth on cardiac structure and function in older individuals, this evidence supports the idea that early-life exposures may influence long-term cardiac remodeling in CHD patients. Of note, birth weight rather than gestational age was the strongest predictor of cardiac structure and function in the current study, likely due in part to birth weight reflecting both intrauterine growth restriction and low gestational age. Nevertheless, these findings collectively imply that further work on the long-term effects of prematurity and low birth weight in adult CHD patients may be warranted.

4.1. Strengths and limitations

The present study benefits from a number of strengths. All participants included in this study underwent CMR imaging, the current golden standard for the assessment of cardiac structure and function. In addition, early-life exposures were ascertained from patient birth records, which is more accurate than ascertainment through patient self-report, a method often used in larger but less well-characterized populations. Some limitations must also be considered when interpreting the findings of this study. First, our study is limited by a small sample size, precluding in-depth exploration of the reported analyses. It would be of interest to perform adequately powered multivariable-adjusted analyses to examine whether adjusting for other perinatal or clinical variables modifies the associations of birth weight with cardiac structure and function, and to test whether the observed relationships were driven by potential confounders. However, although not statistically significant, mean BSA estimates were higher in the normal birth weight group, implicating that the observed differences are not the product of between-group differences in BSA. Second, even though our study was under-powered for multivariable-adjusted analyses, exploratory results suggested the association of birth weight with cardiac remodeling to be independent of age, sex, and BMI. Third, this study involved multiple tests, which increases the risk of type I errors and may result in spurious findings. However, given strong correlations between various measures of cardiac structure and function, and because we had prespecified hypotheses regarding the association between birth weight and these cardiac measures, we opted to use a more lenient threshold for statistical significance (p < 0.05). Throughout the analysis, we prioritized the interpretation of effect sizes and directions rather than strict adherence to p-values alone. Fourth, we cannot exclude the possibility that certain factors we did not account for (e.g., maternal factors, surgical details) affected the observed associations. Finally, the number of participants with low birth weight was relatively low (n = 3), impeding thorough assessment of cardiac changes in ASO patients born at the lowest birth weights or earliest gestations. As previous work suggests that individuals born at the earliest gestations may have the most pronounced changes in cardiac structure and function [26], future studies are needed to investigate these relationships in individuals who underwent the ASO.

5. Conclusions

This study demonstrates that lower birth weight is associated with smaller indexed LV and RV volumes in ASO patients. While lower birth weight was associated with a blunted increase in LVSVi from rest to exercise, there were no significant associations of birth weight with peak VO2. Future research should be directed toward exploring the mechanisms driving the association of between birth weight with long-term outcomes in individuals who underwent the ASO, as well as the broader adult CHD population.

Data availability statement

Data supporting the analyses presented in this manuscript are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare the following financial interests/personal relationships which may be considered as potential competing interests: Art Schuermans reports financial support was provided by Belgian American Educational Foundation Inc. Xander Jacquemyn reports financial support was provided by Belgian American Educational Foundation Inc. If there are other authors, they declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper, other than one of the authors (WB) being an IJCCHD Editorial Board Member, but had no involvement with the handling of this paper.

Acknowledgements

None.

Funding sources

A. Schuermans and X. Jacquemyn were supported by the Belgian American Educational Foundation.

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijcchd.2024.100550.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following is the Supplementary data to this article:

References

- 1.Villafane J., Lantin-Hermoso M.R., Bhatt A.B., Tweddell J.S., Geva T., Nathan M., et al. D-transposition of the great arteries: the current era of the arterial switch operation. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2014;64:498–511. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2014.06.1150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Samanek M. Congenital heart malformations: prevalence, severity, survival, and quality of life. Cardiol Young. 2000;10:179–185. doi: 10.1017/s1047951100009082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Long J., Ramadhani T., Mitchell L.E. Epidemiology of nonsyndromic conotruncal heart defects in Texas, 1999-2004. Birth Defects Res A Clin Mol Teratol. 2010;88:971–979. doi: 10.1002/bdra.20724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Digilio M.C., Casey B., Toscano A., Calabro R., Pacileo G., Marasini M., et al. Complete transposition of the great arteries: patterns of congenital heart disease in familial precurrence. Circulation. 2001;104:2809–2814. doi: 10.1161/hc4701.099786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Warnes C.A. Transposition of the great arteries. Circulation. 2006;114:2699–2709. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.592352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brida M., Diller G.P., Gatzoulis M.A. Systemic right ventricle in adults with congenital heart disease: anatomic and phenotypic spectrum and current approach to management. Circulation. 2018;137:508–518. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.117.031544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Santens B., Van De Bruaene A., De Meester P., Gewillig M., Troost E., Claus P., et al. Outcome of arterial switch operation for transposition of the great arteries. A 35-year follow-up study. Int J Cardiol. 2020;316:94–100. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2020.04.072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Morfaw F., Leenus A., Mbuagbaw L., Anderson L.N., Dillenburg R., Thabane L. Outcomes after corrective surgery for congenital dextro-transposition of the arteries using the arterial switch technique: a scoping systematic review. Syst Rev. 2020;9:231. doi: 10.1186/s13643-020-01487-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Baruteau A.E., Vergnat M., Kalfa D., Delpey J.G., Ly M., Capderou A., et al. Long-term outcomes of the arterial switch operation for transposition of the great arteries and ventricular septal defect and/or aortic arch obstruction. Interact Cardiovasc Thorac Surg. 2016;23:240–246. doi: 10.1093/icvts/ivw102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fricke T.A., d'Udekem Y., Richardson M., Thuys C., Dronavalli M., Ramsay J.M., et al. Outcomes of the arterial switch operation for transposition of the great arteries: 25 years of experience. Ann Thorac Surg. 2012;94:139–145. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2012.03.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lara D.A., Fixler D.E., Ethen M.K., Canfield M.A., Nembhard W.N., Morris S.A. Prenatal diagnosis, hospital characteristics, and mortality in transposition of the great arteries. Birth Defects Res A Clin Mol Teratol. 2016;106:739–748. doi: 10.1002/BDRA.23525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Castellanos D.A., Lopez K.N., Salemi J.L., Shamshirsaz A.A., Wang Y., Morris S.A. Trends in preterm delivery among singleton gestations with critical congenital heart disease. J Pediatr. 2020;222:28–34.e4. doi: 10.1016/J.JPEDS.2020.03.003/ATTACHMENT/0CCD9074-CDE3-4D74-A1F4-0914FA89382F/MMC1.XML. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Laas E., Lelong N., Thieulin A.C., Houyel L., Bonnet D., Ancel P.Y., et al. Preterm birth and congenital heart defects: a population-based study. Pediatrics. 2012;130:e829–e837. doi: 10.1542/peds.2011-3279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Qamar Z.A., Goldberg C.S., Devaney E.J., Bove E.L., Ohye R.G. Current risk factors and outcomes for the arterial switch operation. Ann Thorac Surg. 2007;84:871–878. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2007.04.102. ; discussion 878-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Salna M., Chai P.J., Kalfa D., Nakamura Y., Krishnamurthy G., Quaegebeur J.M., et al. Outcomes of the arterial switch operation in </=2.5-kg neonates. Semin Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2019;31:488–493. doi: 10.1053/j.semtcvs.2018.03.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Schuermans A., Lewandowski A.J. Understanding the preterm human heart: what do we know so far? Anat Rec. 2022 doi: 10.1002/ar.24875. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Schuermans A., den Harink T., Raman B., Smillie R.W., Bch B., Alsharqi M., et al. Differing impact of preterm birth on the right and left atria in adulthood. J Am Heart Assoc. 2022;11 doi: 10.1161/JAHA.122.027305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lewandowski A.J., Levy P.T., Bates M.L., McNamara P.J., Nuyt A.M., Goss K.N. Impact of the vulnerable preterm heart and circulation on adult cardiovascular disease risk. Hypertension. 2020;76:1028–1037. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.120.15574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lewandowski A.J., Augustine D., Lamata P., Davis E.F., Lazdam M., Francis J., et al. Preterm heart in adult life: cardiovascular magnetic resonance reveals distinct differences in left ventricular mass, geometry, and function. Circulation. 2013;127:197–206. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.112.126920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lewandowski A.J., Bradlow W.M., Augustine D., Davis E.F., Francis J., Singhal A., et al. Right ventricular systolic dysfunction in young adults born preterm. Circulation. 2013;128:713–720. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.113.002583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Goss K.N., Haraldsdottir K., Beshish A.G., Barton G.P., Watson A.M., Palta M., et al. Association between preterm birth and arrested cardiac growth in adolescents and young adults. JAMA Cardiol. 2020;5 doi: 10.1001/jamacardio.2020.1511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Crispi F., Rodríguez-López M., Bernardino G., Sepúlveda-Martínez Á., Prat-González S., Pajuelo C., et al. Exercise capacity in young adults born small for gestational age. JAMA Cardiol. 2021;6:1308–1316. doi: 10.1001/JAMACARDIO.2021.2537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sarvari S.I., Rodriguez-Lopez M., Nunez-Garcia M., Sitges M., Sepulveda-Martinez A., Camara O., et al. Persistence of cardiac remodeling in preadolescents with fetal growth restriction. Circ Cardiovasc Imaging. 2017;10 doi: 10.1161/CIRCIMAGING.116.005270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lewandowski A.J., Raman B., Bertagnolli M., Mohamed A., Williamson W., Pelado J.L., et al. Association of preterm birth with myocardial fibrosis and diastolic dysfunction in young adulthood. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2021;78:683–692. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2021.05.053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mohamed A., Lamata P., Williamson W., Alsharqi M., Tan C.M.J., Burchert H., et al. Multimodality imaging demonstrates reduced right-ventricular function independent of pulmonary physiology in moderately preterm-born adults. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2020;13:2046–2048. doi: 10.1016/j.jcmg.2020.03.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Schuermans A., Van den Eynde J., Jacquemyn X., Van De Bruaene A., Lewandowski A.J., Kutty S., et al. Preterm birth is associated with adverse cardiac remodeling and worse outcomes in patients with a functional single right ventricle. J Pediatr. 2023;255:198–206.e4. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2022.11.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Santens B., Van De Bruaene A., De Meester P., Claessen G., Moons P., Claus P., et al. Decreased cardiac reserve in asymptomatic patients after arterial switch operation for transposition of the great arteries. Int J Cardiol. 2023;388 doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2023.131153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Moons P., Goossens E., Luyckx K., Kovacs A.H., Andresen B., Moon J.R., et al. The COVID-19 pandemic as experienced by adults with congenital heart disease from Belgium, Norway, and South Korea: impact on life domains, patient-reported outcomes, and experiences with care. Eur J Cardiovasc Nurs. 2022;21:620–629. doi: 10.1093/EURJCN/ZVAB120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.O WH. ICD-11: International Classification of Diseases 11th revision (11th revision).Available at: https://icd.who.int/.

- 30.Villar J., Cheikh Ismail L., Victora C.G., Ohuma E.O., Bertino E., Altman D.G., et al. International standards for newborn weight, length, and head circumference by gestational age and sex: the Newborn Cross-Sectional Study of the INTERGROWTH-21st Project. Lancet. 2014;384:857–868. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)60932-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.La Gerche A., Claessen G., Van De Bruaene A., Pattyn N., Van Cleemput J., Gewillig M., et al. Cardiac MRI: a new gold standard for ventricular volume quantification during high-intensity exercise. Circ Cardiovasc Imaging. 2013;6:329–338. doi: 10.1161/CIRCIMAGING.112.980037/-/DC1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Claessen G., Schnell F., Bogaert J., Claeys M., Pattyn N., De Buck F., et al. Exercise cardiac magnetic resonance to differentiate athlete's heart from structural heart disease. Eur Heart J Cardiovasc Imaging. 2018;19:1062–1070. doi: 10.1093/EHJCI/JEY050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Barton G.P., Corrado P.A., Francois C.J., Chesler N.C., Eldridge M.W., Wieben O., et al. Exaggerated cardiac contractile response to hypoxia in adults born preterm. J Clin Med. 2021;10 doi: 10.3390/jcm10061166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Huckstep O.J., Williamson W., Telles F., Burchert H., Bertagnolli M., Herdman C., et al. Physiological stress elicits impaired left ventricular function in preterm-born adults. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2018;71:1347–1356. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2018.01.046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sarris G.E., Balmer C., Bonou P., Comas J.V., da Cruz E., Di Chiara L., et al. Clinical guidelines for the management of patients with transposition of the great arteries with intact ventricular septum. Eur J Cardio Thorac Surg. 2017;51:e1–e32. doi: 10.1093/EJCTS/EZW360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Baumgartner H., De Backer J., Babu-Narayan S.V., Budts W., Chessa M., Diller G.-P., et al. ESC guidelines for the management of adult congenital heart disease: the task force for the management of adult congenital heart disease of the European society of cardiology (ESC). Endorsed by: association for European paediatric and congenital cardiology (AEPC), international society for adult congenital heart disease (ISACHD) Eur Heart J. 2020;42:563–645. doi: 10.1093/EURHEARTJ/EHAA554. 2021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Data supporting the analyses presented in this manuscript are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.