Abstract

Subcellular compartmentalization is a universal feature of all cells. Spatially distinct compartments, be they lipid‐ or protein‐based, enable cells to optimize local reaction environments, store nutrients, and sequester toxic processes. Prokaryotes generally lack intracellular membrane systems and usually rely on protein‐based compartments and organelles to regulate and optimize their metabolism. Encapsulins are one of the most diverse and widespread classes of prokaryotic protein compartments. They self‐assemble into icosahedral protein shells and are able to specifically internalize dedicated cargo enzymes. This review discusses the structural diversity of encapsulin protein shells, focusing on shell assembly, symmetry, and dynamics. The properties and functions of pores found within encapsulin shells will also be discussed. In addition, fusion and insertion domains embedded within encapsulin shell protomers will be highlighted. Finally, future research directions for basic encapsulin biology, with a focus on the structural understand of encapsulins, are briefly outlined.

Keywords: Encapsulin, Nanocompartment, Protein shell, Protein capsid, HK97

Encapsulin nanocompartments are one of the most diverse and widespread classes of prokaryotic protein compartments. This review focuses on the structural diversity of encapsulins with a focus on shell structure, pore properties, and domain insertions and fusions found within the encapsulin shell protein.

1. Introduction

Intracellular compartmentalization is one of the defining features of life.[ 1 , 2 ] As prokaryotes do generally not possess lipid‐based organelles, they have evolved alternative, often protein‐based, strategies to compartmentalize and spatially organize their cell interiors.[ 3 , 4 , 5 ] One such approach, widely found across many bacteria and archaea, are protein compartments – self‐assembling protein structures consisting of a protein shell and encapsulated enzymes or whole metabolic pathways. [6] Physical sequestration of biochemical reactions facilitates their spatial and temporal regulation.[ 7 , 8 , 9 ] Compartmentalization in general enables the dynamic storage of nutrients and the sequestration of unwanted compounds, the transport of molecules within or between cells, and the creation of distinct reaction spaces optimized for a given biological process.[ 10 , 11 ]

Bacterial microcompartments (BMCs) were the first class of protein compartments recognized in prokaryotes. [5] BMC protein shells consist of multiple kinds of hexameric, pentameric, and trimeric shell protomers, assemble into (quasi)‐icosahedral structures, and can exceed diameters of 100 nm.[ 12 , 13 ] BMCs either fulfill an anabolic role as carbon‐fixing organelles called carboxysomes[ 14 , 15 ] or participate in catabolic pathways as metabolosomes involved in carbon and nitrogen source utilization.[ 16 , 17 , 18 ]

More recently, another widespread protein compartment type, called encapsulin nanocompartments or encapsulins for short, has been discovered.[ 8 , 19 , 20 ] Encapsulins self‐assemble into generally icosahedral protein compartments with diameters between ca. 20 and 50 nm.[ 20 , 21 , 22 ] The eponymous feature of encapsulins is their ability to encapsulate dedicated cargo enzymes.[ 23 , 24 , 25 , 26 ] Two different cargo loading mechanisms have been identified so far. First, native cargo proteins can contain short and conserved, ten to twenty residues long, peptide sequences at their termini – called targeting peptides (TPs) or cargo‐loading peptides (CLPs) – that mediate cargo loading during shell self‐assembly. [23] Alternatively, cargo proteins can contain extended, mostly disordered domains, often hundreds of residues in length, exhibiting short, five to ten residues long, conserved motifs that facilitate cargo encapsulation.[ 27 , 28 , 29 ] Encapsulins are found in many bacterial and archaeal phyla and are involved in oxidative stress resistance,[ 25 , 30 , 31 , 32 ] iron metabolism and storage,[ 20 , 21 , 22 , 33 , 34 , 35 ] sulfur metabolism,[ 27 , 29 ] and secondary metabolite biosynthesis.[ 28 , 36 ] What differentiates encapsulins from BMCs and other well‐known protein cages like ferritin or lumazine synthase is the fact that the encapsulin shell protein shares the HK97 phage‐like fold, suggesting an evolutionary connection between encapsulins and viruses.[ 8 , 19 , 20 ]

This review focuses on the structural diversity of encapsulin protein shells. Encapsulin biology,[ 8 , 9 , 37 ] the structural and mechanistic details of encapsulin cargo loading, [23] and advances in encapsulin engineering[ 38 , 39 , 40 , 41 , 42 , 43 , 44 , 45 , 46 ] have recently been reviewed and will not be covered here. Special focus will be placed on encapsulin shell symmetry, composition, and dynamics. Shell pores, which mediate the selective movement of small molecule substrates and products of encapsulated cargo enzymes into and out of the shell, will also be discussed. Finally, fusion and insertion domains found within the encapsulin shell protomer, whose functions largely remain to be elucidated, will be highlighted. In closing, future research directions will be briefly outlined.

2. Encapsulin Protomer and Shell Structure

Based on sequence and structural similarity as well as operon organization and genome neighborhood conservation, encapsulins have been grouped into four families (Figure 1A).[ 8 , 19 ] Family 1 contains the best studied encapsulins, with experimental data available for multiple systems regarding their shell structures, associated cargo function, and cargo loading mechanisms. Family 1 encapsulins are present in over 30 prokaryotic phyla, with the majority found in Pseudomonadota, Actinomycetota, and Bacillota. Cargo loading in Family 1 systems is almost always based on short (ca. 10 residues) C‐terminal targeting peptides. Recently, the first experimental data focused on Family 2 encapsulins have begun to emerge.[ 27 , 28 , 29 , 36 ] Family 2 can be divided into two sub‐families based on the absence (Family 2 A) or presence (Family 2B) of a cyclic nucleotide‐binding fold domain (CBD) [47] and a recently identified metal‐binding sub‐domain (MBD), [28] both inserted into the HK97 phage‐like fold. However, in comparison to Family 1 systems, little information is available for Family 2 encapsulins. Similar to Family 1 systems, Family 2 encapsulins are broadly found across prokaryotic phyla and are especially common in members of the Actinomycetota and Pseudomonadota. Cargo loading in Family 2 encapsulins is mediated by extended (ca. 50–300 residues) N‐ or C‐terminal cargo loading domains. Family 3 encapsulin systems currently lack experimental validation and remain putative. Family 3 encapsulins are always embedded in secondary metabolite biosynthetic gene clusters, primarily found in members of the Actinomycetota and Myxococcota. No obvious targeting peptides or domains have been identified in the surrounding operon components. Family 4 encapsulins represent heavily truncated versions of the HK97 phage‐like fold and one Family 4 structure, determined as part of a structural genomics project, is currently available. Family 4 systems have been identified in the archaeal phylum Euryarchaeota and the bacterial phylum Bacteroidota.

Figure 1.

Encapsulin classification and protomer structures. (A) Encapsulin classification scheme based on sequence and structural homology as well as genome neighborhood conservation. Accessory genes represent non‐cargo but conserved operon components. Question marks indicate lack of experimental evidence. Enc: encapsulin shell protein. (B) Structures of Family 1 encapsulin protomers. Examples of protomers found in T=1, T=3, and T=4 shells are shown. Core domains of the HK97 phage‐like fold (A‐domain, P‐domain, and E‐loop) are colored consistently throughout all panels. PDB IDs for all structures shown in parentheses. (C) Family 2 encapsulin protomers. A Family 2 A protomer (left) and a Family 2B protomer (right) are shown. Distinct domains are highlighted by color. (D) Alpha Fold (AF)‐predicted structure of a putative Family 3 encapsulin shell protein. A unique N‐terminal extension consisting of an N‐helix and a N‐β‐strand are highlighted in pink. UniProt ID shown above the protomer. (E) Family 4 encapsulin protomer structure.

Family 1 (Figure 1B), Family 2 (Figure 1C), and Family 3 (Figure 1D) encapsulin shell protomers exhibit strong structural homology to HK97‐type viral capsid proteins[ 8 , 19 ] and share three universally conserved structural features – the axial domain (A‐domain), peripheral domain (P‐domain), and the extended loop (E‐loop). In contrast, Family 4 protomers exhibit a heavily truncated HK97 phage‐like fold, with only the triangular A‐domain still being present (Figure 1E). All Family 1 encapsulin shell proteins contain an N‐terminal helix (N‐helix) that together with the P‐domain, forms the TP binding site, crucial for directing and anchoring cargo proteins to the interior of the shell.[ 4 , 24 , 25 , 26 , 48 ] The primary structural difference between Family 1 protomers is the conformation of the E‐loop, which can either point away from the A‐domain in encapsulin shells with a triangulation number (T number) of T=1, or towards the A‐domain in T=3 and T=4 shells (Figure 1B).[ 20 , 22 , 33 ] In contrast to Family 1 systems, Family 2 protomers can contain an extended N‐terminus consisting of an N‐arm, N‐helix, and an up to eighty residues long disordered N‐extension (Figure 1C), features similar to the N‐termini found in many HK97‐type viral capsid proteins. [29] While all Family 2 protomer sequences contain this extended N‐terminus, in some Family 2B shell structures, it is not resolved (Figure 1C).[ 28 , 49 ] The abovementioned CBD and MBD insertions that differentiate 2B from 2 A systems are both embedded into the E‐loop with the MBD located below the CBD, making substantial contacts with the A‐domain and P‐domain. No structural data for Family 3 encapsulins is currently available. However, based on Alpha Fold predictions, [50] the HK97 phage‐like fold is conserved in Family 3 protomers (Figure 1D). An about fifty residues long N‐terminal extension, dissimilar to Family 1 or Family 2 systems, is predicted to be present in Family 3 shell proteins. Parts of this extension form a fourth β‐strand extending the three‐strand P‐domain β‐sheet while a short helix occupies a similar position as the N‐helix in Family 1 protomers. In Family 4 encapsulins, only the A‐domain of the HK97 phage‐like fold is present (Figure 1E). The single available Family 4 encapsulin structure suggests that Family 4 protomers form dimers and not protein shells. However, their structural homology, co‐localization within operons with conserved enzyme components, and the fact that they are part of the same Pfam clan as the other encapsulin families (CL0373), [51] has resulted in their annotation as a divergent class of encapsulins.

All studied Family 1 and Family 2 encapsulins assemble into closed protein shells, generally exhibiting icosahedral symmetry. These encapsulin shells share many characteristics with viral capsids assembled from HK97‐type protomers. [8] The HK97 phage‐like fold is found in the major capsid proteins of bacteriophages of the order Caudovirales,[ 52 , 53 ] in capsid proteins of tailed archaeal viruses, [54] and in the floor domains of animal‐infecting viruses of the order Herpesviridae. [55] Encapsulins represent the only non‐viral assemblies known to exhibit the HK97 phage‐like fold.[ 8 , 19 , 20 ] The structural versatility and plasticity of the HK97 phage‐like fold is highlighted by the fact that its three core structural features, the A‐domain, P‐domain, and E‐loop, are conserved in proteins with low sequence similarity while a range of insertion and extension domains can be embedded at various positions within HK97‐type proteins.[ 56 , 57 ] So far, Family 1 encapsulin shells with T=1, T=3, and T=4 icosahedral symmetry have been characterized consisting of 60, 180, or 240 protomers, respectively (Figure 2A). All icosahedral protein shells or capsids contain twelve five‐fold, twenty three‐fold, and thirty two‐fold axes of symmetry. While T=1 shells can be assembled from twelve pentamers alone, icosahedra with T numbers greater than T=1 require both pentamers and hexamers to tile a closed shell or capsid.[ 58 , 59 ] In addition to twelve pentamers, T=3 shells contain twenty, and T=4 shells thirty, hexamers. T numbers also reflects the number of unique protomers occupying quasi‐equivalent positions within the asymmetric unit (ASU) of a given protein shell, one for T=1, three for T=3, and four for T=4 shells (Figure 2B). The structures of distinct protomers within T=3 and T=4 ASUs are highly similar. This quasi‐equivalency, first introduced by Caspar and Klug, [58] as well as subtle shifts between ASUs, are responsible for a single type of shell protomer being able to form both pentameric and hexameric interfaces resulting in shells with different T numbers. While pentamers always align with the icosahedral five‐fold axes of symmetry, hexamers can either be arranged around the three‐fold (T=3) or two‐fold (T=4) symmetry axes (Figure 2C). All so far characterized Family 2 encapsulins, both 2 A and 2B systems, exhibit T=1 icosahedral symmetry (Figure 2D).[ 27 , 28 , 29 , 49 ] In comparison to Family 1 shells, Family 2 A encapsulins have a less spherical appearance caused by a more pronounced turret‐like conformation of the twelve shell pentamers. Family 2B shells exhibit a similar assembly of the core HK97 phage‐like fold as compared to Family 2 A systems, however, the presence of the CBD and MBD insertions results in a strikingly different appearance. CBD/MBD domains are externally displayed, and one pair of CBD/MBD domains is arranged around all thirty two‐fold axes of symmetry (Figure 2D).[ 28 , 49 ]

Figure 2.

The diversity of encapsulin assemblies. (A) Family 1 encapsulin shells. T=1, T=3, and T=4 shells are shown. Pentamers are colored in blue, hexamers in grey. The number of pentamers and hexamers necessary to form a shell of a given triangulation (T) number is shown. (B) The symmetry and organization of icosahedral encapsulin shells with different T numbers. Asymmetric units (ASUs) are shown in red. (C) T=3 (left) and T=4 (right) Family 1 hexamers are shown highlighting their ability to occupy both three‐fold (T=3) and two‐fold (T=4) symmetrical positions. (D) Family 2 A (left) and 2B (right) shells. External CBD/MBDs are shown in green. (E) Family 1 encapsulin shell with a bound flavin mononucleotide (FMN) cofactor. FMN binding sites are arranged around the three‐fold symmetry axis (left). FMN binding site (right). (F) Schematic of the complex assembly of mixed two‐component encapsulin shells. Numbers highlight unique interactions around the 2‐, 3‐, and 5‐fold axes (G) Structurally characterized dimeric assembly of a Family 4 encapsulin.

While most Family 1 encapsulin shells are currently assumed to exclusively function as selectively permeable diffusion barriers, the Thermotoga maritima T=1 shell has been found to contain a flavin, likely flavin mononucleotide (FMN), binding site (Figure 2E).[ 60 , 61 ] FMNs are bound at protomer interfaces close to the three‐fold axis of symmetry for a total of sixty flavins per 60mer T=1 shell. The FMN binding site is formed by a conserved tryptophan residue and an arginine residue sandwiching the FMN isoalloxazine ring via π‐stacking interactions (Figure 2E). The precise function of this FMN in the context of the iron‐precipitating T. maritima encapsulin is currently unknown. However, it has been proposed to play a role in electron transport through the shell to enable the reduction and release of stored iron.[ 61 , 62 ]

Nearly all characterized HK97 phage‐like fold assemblies are formed by a single major capsid or shell protein. There is one characterized virus – bacteriophage T4 – that utilizes two distinct HK97‐type capsid proteins for distinct structural roles, forming either homo‐pentamers or homo‐hexamers.[ 63 , 64 ] Genome‐mining studies have identified many Family 2B encapsulin operons encoding two distinct encapsulin shell proteins.[ 8 , 19 ] Recently, it was shown that such a Family 2B system found in Streptomyces lydicus does indeed form two‐component mixed shell assemblies with variable shell composition (Figure 2F). [49] In contrast to the bacteriophage T4 capsid, the two S. lydicus encapsulin shell components form a quasi‐icosahedral T=1 shell where both shell protomers can occupy any position and engage in all possible inter‐protomer interactions. The ability of these two protomers to form hetero‐pentamers with variable relative compositions results in the irregular tiling of the T=1 shell, thus deviating from strict icosahedral symmetry.

As mentioned above, Family 4 encapsulins do not seem to form icosahedral shells but instead dimeric assemblies (Figure 2G). The interaction between the two Family 4 proteins is different from the interaction between two adjacent A‐domains found in the context of an HK97‐type shell or capsid. This is not surprising as most features of the HK97 phage‐like fold have been lost in Family 4 encapsulins.

3. Pores in Encapsulin Shells

All so far studied Family 1 and Family 2 encapsulin shells contain pores. As is the case for other protein compartments like ferritins and BMCs, encapsulin pores are thought to be crucial for controlling the flux of small molecules and ions into and out of the encapsulin shell. Encapsulin pores are generally smaller than 20 Å in diameter which generally prevents any protein from gaining access to the encapsulin lumen once the shell is assembled (Figure 3A).[ 20 , 21 , 22 , 25 , 26 , 32 , 33 , 48 , 60 , 61 , 65 , 66 , 67 ] Static pores smaller than ca. 4.5 Å are essentially closed for small molecule flux but may still transmit inorganic ions.[ 7 , 68 ] Thus, the encapsulin shell acts as a selectively permeable diffusion barrier, allowing small molecules and ions, necessary for encapsulin function, to enter the shell via its pores while excluding all other, potentially interfering, cellular components from the shell interior. This can create specific nano‐environments inside the encapsulin shell, optimized for a given process. For example, a recently characterized Family 2 A encapsulin shell was found to exclude the ubiquitous cellular reducing agent glutathione, thus creating a more oxidizing interior environment, necessary for the biological function of the system. [27]

Figure 3.

Pores in Family 1 encapsulins. (A) Identified pore positions in T=1, T=3, and T=4 encapsulin shells (left) and summary of all pores identified in structurally characterized Family 1 shells highlighting their pore diameters (right). PDB IDs shown on the x‐axis. 2‐fold_a: two‐fold adjacent; 5‐fold_a: five‐fold adjacent; PHH: pentamer‐hexamer‐hexamer interface. (B) Representative examples of exterior and interior surface views of all pore types identified in Family 1 encapsulins. Electrostatic surfaces are shown. (C) Five‐fold pore dynamics with discrete closed (left) and open (right) states identified in the Haliangium ochraceum T=1 encapsulin. (D) Pore dynamics of the Acidipropionibacterium acidipropionici T=1 shell.

While open pores (>4.5 Å) at the five‐fold axis of symmetry (5‐fold) can be found in all so far characterized Family 1 encapsulin shells, open pores located at the three‐fold symmetry axis (3‐fold) are only found in some T=1 and T=4 shells (Figure 3A). Two‐fold pores (2‐fold) are generally very small and likely only able to transmit ions. Another type of pore found exclusively in Family 1 T=1 shells are two‐fold adjacent pores (2‐fold_a). They often represent the largest pores in T=1 shells. A pore type only found in T=3 shells are five‐fold adjacent pores (5‐fold_a) located within pentamers. With T=3 and T=4 shells containing both pentamers and hexamers, they can form another pore type located at the pseudo‐three‐fold interface between a pentamer and two hexamers (PHH). Overall, encapsulin pore sizes range from essentially closed up to 18 Å in diameter. Across different Family 1 shell sizes and cargo types, the electrostatic charge at the exterior and interior of pores is mostly negative to neutral, rarely positive (Figure 3B). While the details of how pore size and charge influence the functioning of native encapsulin systems remains to be elucidated, a number of mutational studies, focused on five‐fold pore residues, have found that altering pore properties has a clear effect on the diffusion of small molecules and ions across the shell.[ 7 , 68 , 69 , 70 ] In addition, changing pore residues can often disrupt proper shell assembly or even result in alternative assembly geometries, deviating from icosahedral symmetry. [71] This highlights the importance of pore residues for mediating shell assembly and overall shell stability.

Recent structural analyses of Family 1 T=1 encapsulin shells have highlighted that five‐fold pores are not static but dynamic. Discrete closed (7OE2) and open (7OEU) conformations could be resolved for the Haliangium ochraceum T=1 encapsulin shell under physiological conditions with a substantial difference in pore diameter between the two states of ca. 6 Å (Figure 3C). [65] Similarly, the T=1 encapsulin shell of the acid‐tolerant bacterium Acidipropionibacterium acidipropionici was found to display two resolvable five‐fold pore states – closed and open – at physiological pH while under strongly acidic conditions, only a single closed state could be observed (Figure 3D). [67] The difference in pore diameter is over 10 Å, with the A. acidipropionici open pore state representing the largest so far identified pore in Family 1 encapsulin shells. In both of these systems displaying dynamic five‐fold pores, a conformational change of the pore‐loop connecting the protomer helices α6 and α7 within the A‐domain, in combination with a concerted backwards tilt of the pentameric protomers away from the five‐fold symmetry axis, allows for the switch between closed and open five‐fold pore states.

As highlighted above, the HK97‐type domain of Family 2 A and 2B encapsulins is highly similar.[ 27 , 28 , 29 , 49 ] This similarity extends to their five‐ and three‐fold pores (Figure 4A and B) which, at 4–8 Å in diameter, are comparable to Family 1 pores. In general, pores in Family 2 systems are less strongly negatively charged and the pore transits are relatively electrostatically neutral. A major difference between both Family 1 and Family 2 encapsulins as well as 2 A and 2B systems are their two‐fold pores. While the two‐fold pores in Family 1 encapsulins are formed by the E‐loops of two protomers, in Family 2 systems, two‐fold pore structure depends on the N‐arms of two neighboring shell proteins. In Family 2 A encapsulins, the N‐arms and N‐helices of two protomers interact and surround the two‐fold axis of symmetry, forming a relatively small two‐fold pore (<4.5 Å) (Figure 4C).[ 27 , 29 ] The two N‐arms/N‐helices are stabilized by overlapping E‐loops of neighboring protomers in a chainmail‐like fashion. [53] In contrast, in the Streptomyces griseus Family 2B shell (9BHV), a markedly different two‐fold pore can be observed. [28] The fact that the N‐arm, N‐helix, and N‐extension are not structured in the S. griseus system results in a very large and elongated two‐fold pore, with dimensions of ca. 15×50 Å (Figure 4D). While the externally displayed CBDs, inserted into E‐loops, partially occlude this Family 2B two‐fold pore when viewed from the shell exterior (Figure 2D), the pore is not affected by CBDs and is in fact completely open. In the recently characterized two‐component Family 2B system from S. lydicus, [49] two conformationally distinct two‐fold pores states are present (Figure 4E), further adding to the complexity of this mixed quasi‐icosahedral shell assembly. Specifically, an open state with unstructured N‐terminus, similar to the Family 2B S. griseus system, and a closed state with clearly resolved N‐terminus, reminiscent of Family 2 A shells, could be observed.

Figure 4.

Pores in Family 2 encapsulins. (A) Exterior and interior surface views of all pore types identified in the Acinetobacter baumannii Family 2 A encapsulin. Electrostatic surfaces are shown. (B) Five‐ and three‐fold pores found in the Streptomyces griseus Family 2B shell are shown as electrostatic surface. (C) Detailed exterior and interior view of a two‐fold pore found in a Family 2 A shell. The N‐arm and N‐helix are shown in red. E‐loops are shown in yellow. Both ribbon and surface representations are shown. (D) The open two‐fold pore of the S. griseus Family 2B encapsulin. The position of CBDs above the two‐fold pores is outlined in green. Besides their outline, CBDs are fully transparent. (E) The different two‐fold pore states observed in the Streptomyces lydicus two‐component Family 2B shell – open (left) and closed (right). CBDs omitted for clarity. The N‐arm and N‐helix are shown in red.

4. Domain Fusions and Insertions

Beyond the ability to form icosahedral capsids and shells of vastly different size, ranging from T=1 to T=52, the HK97 phage‐like fold is also able to accommodate a diverse range of different insertion and fusion domains.[ 56 , 72 ] For example, the bacteriophage T4 HK97‐type capsid protein exhibits an externally displayed chitin‐binding‐like insertion domain within its E‐loop [73] while the bacteriophage 029 capsid protein contains an immunoglobulin‐like fusion domain at its C‐terminus. [74] Bacteriophages P22,[ 75 , 76 ] Sf6, [77] and CUS‐3 [78] all contain external insertion domains within the A‐domains of their HK97 phage‐like fold coat proteins. The most striking example of a C‐terminal fusion, partially interwoven with the HK97 phage‐like fold A‐domain, can be found in viruses of the order Herpesviridae where large middle and upper domains protrude from the HK97‐type floor domain to form over 10 nm high external towers.[ 79 , 80 , 81 , 82 , 83 ] N‐terminal fusions are also observed in HK97‐type viral capsids – called Δ‐domains – that act as fusion scaffolding domains enabling the formation of capsids with T number larger than 1.[ 84 , 85 ]

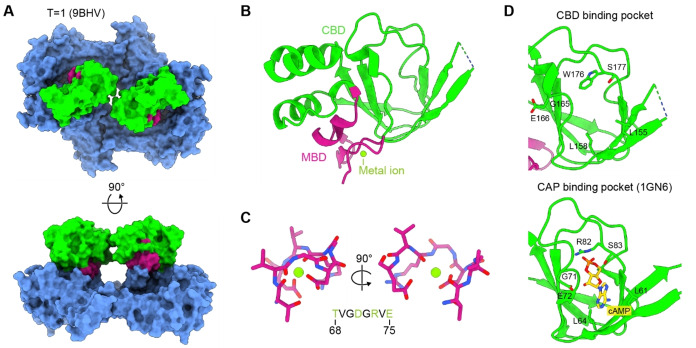

Similar to HK97‐type viral capsid proteins, encapsulin shell proteins have also been found to contain a number of different types of insertion or fusion domains.[ 8 , 19 , 21 , 86 ] So far, only one type of domain – the CBD/MBD insertion found in Family 2B shells – has been structurally characterized in the context of the encapsulin shell.[ 27 , 49 ] As mentioned above, CBD/MBD insertions are embedded into the E‐loop of the HK97 phage‐like fold of the encapsulin shell protein at the genetic level. They are displayed externally and arranged around all two‐fold symmetry axes of the icosahedral Family 2B shell (Figure 5A). The MBD can be described as a sub‐domain within the CBD (Figure 5B) and makes substantial contacts with the A‐domain of the HK97 phage‐like fold. The MBD does not share any significant sequence or structural homology to any characterized domain. A metal ion – based on coordination geometry, likely a magnesium ion – is bound within the MBD by a set of four conserved residues located within a tight loop (Figure 5C). It has been hypothesized that the MBD may play a role in mediating CBD‐HK97 phage‐like domain interactions and might be important for controlling CBD conformation.[ 27 , 49 ] While CBDs share sequence and structural similarity with cyclic adenosine monophosphate (cAMP)‐binding domains,[ 87 , 88 ] especially the catabolite activator protein (CAP) found in Escherichia coli,[ 89 , 90 ] Family 2B CBDs do not seem to bind cAMP. [28] This is supported by multiple types of orthogonal in vitro binding experiments which all showed no detectable affinity of cAMP towards CBDs. In addition, analysis of the putative cAMP binding site indicates that a crucial and conserved arginine residue found in E. coli CAP (R82) and other confirmed cAMP‐binding domains is missing in Family 2B CBDs (Figure 5D). Instead, a conserved tryptophan residue (W176) is found in the equivalent position, likely preventing cAMP binding. These facts indicate that Family 2B CBDs likely bind a, yet to be identified, small molecule ligand, different than cAMP. Regarding the function of CBDs, it has been suggested that ligand binding might result in a conformational change of the CBDs themselves and/or the E‐loop, resulting in the opening or closing of the two‐fold pores. [28] Considering that distinct open and closed two‐fold pore states have already been reported, albeit both in the absence of any detectable ligand, this hypothesis seems possible. [49] By allowing or restricting substrate flux into the encapsulin shell, distinct pore states may modulate the activity of encapsulated cargo enzymes. In essence, the function of CBDs may be to receive an external signal, in the form of a small molecule ligand, which in turn is used by the Family 2B shell to control the activity of internalized cargo enzymes.

Figure 5.

CBD and MBD insertions in Family 2B encapsulins. (A) Top and side views of externally displayed CBD/MBD E‐loop insertions arranged around the two‐fold axis of symmetry. Surface representation is shown. MBDs highlighted in pink, CBDs shown in green. MBD: metal‐binding domain. CBD: cyclic nucleotide‐binding fold domain. (B) A single CBD/MBD insertion shown in ribbon representation. The metal ion coordinated by the MBD is highlighted. (C) Close‐up view of the metal‐binding loop within the MBD highlighting metal coordination. Residues shown in stick representation. The sequence of the metal binding loop within the S. griseus MBD is shown (bottom) and residues involved in metal coordination are highlighted in green. (D) Comparison of the putative CBD ligand binding pocket and the cAMP binding site found in E. coli catabolite activator protein (CAP). cAMP (yellow) and key binding site residues are shown in stick representation.

The very first encapsulin shell structure reported – at the time not recognized as an encapsulin but described as a virus‐like particle – was a Family 1 T=3 encapsulin found in the hyperthermophilic archaeon Pyrococcus furiosus (2E0Z). [21] This archaeal Family 1 encapsulin is now recognized to be part of a class of fusion encapsulins carrying N‐terminal ferritin‐like protein (Flp) fusion domains (Figure 6A).[ 8 , 19 ] As the Family 1 N‐terminus is located on the interior of the assembled shell, all N‐terminal fusions will be localized to the encapsulin lumen, similar to non‐fusion cargo proteins. No other separate cargo proteins have so far been identified for archaeal Flp fusion encapsulins. In the original P. furiosus T=3 shell structure, determined via x‐ray crystallography, the Flp fusion domains could not be resolved. This was likely caused by the Flp domain being flexibly tethered to the N‐terminus of the HK97 phage‐like fold, resulting in substantial mobility of internalized Flp domains, thus deviating from crystallographic symmetry. A predicted Alpha Fold structure of the P. furiosus protomer highlights that the N‐terminal domain consists of a two‐helix bundle in isolation (Figure 6B). Recent structural studies of the P. furiosus Flp cargo protein alone – with the HK97‐type domain removed – show that it forms a D5 symmetrical homo‐decameric helical assembly (Figure 6C) which has been suggested to be also present in the natively assembled Flp fusion encapsulin. [35] To realize decameric Flp assemblies within the context of the T=3 geometry of the P. furiosus shell, consisting of twelve pentamers and twenty hexamers, the five Flp domains of a given pentamer and one Flp domain each of the five surrounding hexamers would have to form a decameric Flp complex (Figure 6D). With full engagement at the pentamers, resulting in twelve Flp decamers per shell, sixty Flp domains would remain free. It remains to be seen if this model is correct and if so, what the function of the uncomplexed Flp domains may be.

Figure 6.

Fusion encapsulin systems. (A) Domain organization of archaeal Family 1 Flp fusion encapsulins. Flp: ferritin‐like protein. (B) Alpha Fold prediction of the P. furiosus Flp fusion protomer. All predicted structures are colored based on pLDDT scores. (C) Homo‐decameric helical assembly of the excised P. furiosus Flp. (D) Schematic highlighting individual Flps (red dot) involved in the formation of decameric complexes located below the five‐fold axis in the context of an assembled T=3 shell. (E) Domain organization of Family 1 cEnc encapsulins found in anammox bacteria. (F) Predicted Alpha Fold structure of a cEnc protomer. (G) Alpha Fold prediction of the diheme cytochrome c fusion domain (Cytc) highlighting the two stacked heme groups in stick representation. (H) Domain organization of helical domain (HD)‐containing Family 3 encapsulins. (I) Alpha Fold prediction of an HD‐containing fusion protomer. (J) Alpha Fold‐predicted pentamer highlighting the formation of a helical bundle above the five‐fold pore.

Another N‐terminal fusion domain found in Family 1 encapsulins has previously been computationally identified in the genomes of anammox bacteria of the phylum Planctomycetes.[ 36 , 86 , 91 ] These unusual encapsulins – called cEnc – carry a diheme cytochrome c fusion domain (Cytc) at their N‐terminus, connected to the HK97 phage‐like fold via a flexible linker (Figure 6E). Often, a conserved enzyme component, annotated as a copper reductase‐hydroxylamine oxidoreductase fusion protein, can be found right next to the cEnc‐encoding gene and may represent a cEnc cargo protein. Anammox bacteria are able to carry out anaerobic ammonium oxidation inside a lipid‐based intracellular organelle called the anammoxosome.[ 92 , 93 , 94 ] Proteins targeted to the anammoxosome interior usually carry N‐terminal signal peptides necessary for translocation. Such a signal peptide is also found in cEnc protomers, indicating that these unusual encapsulins are localized to the interior of the anammoxosome organelle (Figure 6E). Alpha Fold‐based structure prediction of the cEnc protomer suggests that the Cytc domain directly interacts with the P‐domain and N‐helix of the HK97 phage‐like domain (Figure 6F). The diheme Cytc domain is predicted to form a compact globular fold with the two covalently bound heme groups stacked parallel to one another (Figure 6G). Diheme Cytc domains in anammox bacteria are often involved in electron transfer reactions between anammox‐related enzymes.[ 92 , 93 ] In analogy, Cytc domains within cEnc might be able to transfer electrons across the encapsulin shell. This might be necessary for the activity of any putative cargo enzymes. cEnc has also been suggested to be able to mineralize iron within the anammoxosome through a so far unknown mechanism. Iron‐rich electron‐dense puncta, too large to be ferritins, are often observed within the anammoxosome in electron microscopy thin sections which could represent cEnc encapsulins.[ 93 , 95 , 96 ]

Computational searches have identified another type of putative fusion encapsulin classified as a Family 3 system. [19] These fusion encapsulins carry a C‐terminal helical domain (HD) and are found in the genus Mesorhizobium (Figure 6H). Genome neighborhood analysis indicates that they are always embedded within small molecule biosynthetic gene clusters of unknown function. The HD at the C‐terminus is predicted to contain four helices with partial membrane helix character, containing a substantial number of hydrophobic residues (Figure 6I). Considering that the C‐terminus within the HK97 phage‐like fold protrudes to the shell exterior and is located close to the symmetry axes and that within the context of an icosahedral encapsulin shell, pentamers and hexamers could be formed, five or six helical domains may interact with one another. Indeed, an Alpha Fold prediction of five copies of the Mesorhizobium delmotii protomer yields an assembled pentamer with HDs forming an external channel‐like protrusion located on top of the five‐fold pore (Figure 6J). Similar structures are predicted for hexameric assemblies. Within a putative pentamer, the exterior helical channel consists of twenty helices with the outside of the helical bundle predicted to exhibit substantial surface hydrophobicity. While no experimental data is available for these systems, these structure predictions may suggest that HD‐containing Family 3 encapsulins are able to interact with lipid membranes and that their HDs can act as channels for transmitting small molecules into and out of the encapsulin shell.

5. Summary and Outlook

While substantial progress has been made over the past five years with respect to the structural understanding of encapsulin assemblies, many challenges remain. One of them is to elucidate the dynamics of encapsulin pores and the triggers that favor one pore state over another. This includes both Family 1 five‐fold and Family 2 two‐fold pores, and potentially other types of pores. Advanced computational tools for the analysis of discrete and continuous heterogeneity in cryo‐electron microscopy data are now available and will likely be indispensable for addressing these questions. The dynamics of CBD/MBD insertions and their role in determining the two‐fold pore state in Family 2B shells is currently not well understood and could likewise be addressed through detailed analyses of CBD/MBD conformational flexibility. In addition, the identification of CBD ligands and how ligand binding influences Family 2B shell conformation and biological function should be prioritized in the future. The recent discovery of two‐component Family 2B encapsulin shells further adds to the complexity of these assemblies and detailed future studies are needed to better understand their assembly constraints and structural states. While information about the assembly mechanisms of some HK97‐type viral capsids is currently available, how individual encapsulin protomers associate and self‐assemble into closed icosahedral shells is still unknown. Progress could be made through in vitro studies of engineered protomers or in vitro disassembly and reassembly assays using pH or ionic strength shifts. Ideally though, shell assembly could be followed in situ using cryo‐electron tomography to capture native assembly intermediates.

Currently, no or limited structural information is available for Family 3 and Family 4 encapsulins. Future efforts should be focused on investigating these systems in general and determining their assembly states and structures in particular. As most of these uncharacterized encapsulins are found in high GC Gram‐positive organisms (Family 3) or hyperthermophilic and anaerobic archaea (Family 4), innovative heterologous expression or native isolation strategies might need to be employed to produce these systems in native‐like states for downstream characterization. Similarly, as no structural information for cEnc and HD fusion encapsulins is available at the moment, their structural characterization should also be prioritized.

Basic studies investigating encapsulin structure, self‐assembly, and cargo loading have so far provided a tremendously useful molecular toolbox for encapsulin engineering aimed at utilizing encapsulin‐based systems for applications in biomedicine, biocatalysis, and bionanotechnology. It is likely that continued discovery‐ and curiosity‐driven work on encapsulins will expand this toolbox and lead to novel innovative and impactful synthetic biology use cases of engineered encapsulins with real‐world impact.

Conflict of Interests

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Biographical Information

Tobias W. Giessen obtained his Diplom (BS/MS) in Chemistry at Phillips University Marburg in 2010 and his PhD in Biochemistry at the same institution in 2013, working with Mohamed A. Marahiel. Following postdoctoral research at Harvard Medical School and the Wyss Institute at Harvard in the group of Pamela A. Silver, Tobias started his independent career at the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor in 2019. His research interests are currently focused on encapsulin biology and engineering, enzyme filaments, and natural product biosynthesis.

Acknowledgments

I acknowledge funding from the NIH (R35 GM133325), NSF (2342136), and the UM Research Scouts program (OORRS033123). Molecular graphics analyses were performed using UCSF ChimeraX developed by the Resource for Biocomputing, Visualization, and Informatics at the University of California, San Francisco, with support from the National Institutes of Health R01 GM129325 and the Office of Cyber Infrastructure and Computational Biology, National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases.

Giessen T. W., ChemBioChem 2024, 25, e202400535. 10.1002/cbic.202400535

References

- 1. Cornejo E., Abreu N., Komeili A., Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 2014, 26, 132–138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Diekmann Y., Pereira-Leal J. B., Biochem. J. 2013, 449, 319–331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Gabaldón T., Pittis A. A., Biochimie 2015, 119, 262–268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Aussignargues C., Pandelia M. E., Sutter M., Plegaria J. S., Zarzycki J., Turmo A., Huang J., Ducat D. C., Hegg E. L., Gibney B. R., Kerfeld C. A., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2016, 138, 5262–5270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Kerfeld C. A., Heinhorst S., Cannon G. C., Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 2010, 64, 391–408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Greening C., Lithgow T., Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2020, 18, 677–689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Adamson L. S. R., Tasneem N., Andreas M. P., Close W., Jenner E. N., Szyszka T. N., Young R., Cheah L. C., Norman A., MacDermott-Opeskin H. I., O'Mara M. L., Sainsbury F., Giessen T. W., Lau Y. H., Sci. Adv. 2022, 8, eabl7346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Giessen T. W., Annu. Rev. Biochem. 2022, 91, 353–380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Nichols R. J., Cassidy-Amstutz C., Chaijarasphong T., Savage D. F., Crit. Rev. Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2017, 52, 583–594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Giessen T. W., Silver P. A., J. Mol. Biol. 2016, 428, 916–927. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Govindarajan S., Nevo-Dinur K., Amster-Choder O., FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 2012, 36, 1005–1022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Melnicki M. R., Sutter M., Kerfeld C. A., Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 2021, 63, 1–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Ochoa J. M., Yeates T. O., Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 2021, 62, 51–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Turmo A., Gonzalez-Esquer C. R., Kerfeld C. A., FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 2017, 364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Liu L. N., Trends Microbiol. 2022, 30 (6), 567–580, 10.1016/j.tim.2021.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Bobik T. A., Lehman B. P., Yeates T. O., Mol. Microbiol. 2015, 98, 193–207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.B. Ferlez, M. Sutter, C. A. Kerfeld, mBio 2019, 10 (1), e02327-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 18. Prentice M. B., Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 2021, 63, 19–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Andreas M. P., Giessen T. W., Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 4748. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.M. Sutter, D. Boehringer, S. Gutmann, S. Günther, D. Prangishvili, M. J. Loessner, K. O. Stetter, E. Weber-Ban, N. Ban, M. Sutter, D. Boehringer, S. Gutmann, S. Günther, D. Prangishvili, M. J. Loessner, K. O. Stetter, E. Weber-Ban, N. Ban, Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2008, 15 (9), 939–48, 10.1038/nsmb.1473. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 21. Akita F., Chong K. T., Tanaka H., Yamashita E., Miyazaki N., Nakaishi Y., Suzuki M., Namba K., Ono Y., Tsukihara T., Nakagawa A., J. Mol. Biol. 2007, 368, 1469–1483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Giessen T. W., Orlando B. J., Verdegaal A. A., Chambers M. G., Gardener J., Bell D. C., Birrane G., Liao M., Silver P. A., Elife 2019, 8, e46070. doi: 10.7554/eLife. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Jones J. A., Benisch R., Giessen T. W., J. Mater. Chem. B 2023, 11, 4377–4388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Altenburg W. J., Rollins N., Silver P. A., Giessen T. W., Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 4951. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Jones J. A., Andreas M. P., Giessen T. W., Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 2558. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Kwon S., Andreas M. P., Giessen T. W., J. Struct. Biol. 2023, 215, 108022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Benisch R., Andreas M. P., Giessen T. W., Sci. Adv. 2024, 10, eadk9345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.M. P. Andreas, T. W. Giessen, bioRxiv 2024, 2024.2004.2023.590730.

- 29. Nichols R. J., LaFrance B., Phillips N. R., Radford D. R., Oltrogge L. M., Valentin-Alvarado L. E., Bischoff A. J., Nogales E., Savage D. F., Elife 2021, 10, e59288, doi: 10.7554/eLife.59288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Lien K. A., Dinshaw K., Nichols R. J., Cassidy-Amstutz C., Knight M., Singh R., Eltis L. D., Savage D. F., Stanley S. A., Elife 2021, 10, e74358. doi: 10.7554/eLife.74358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Rahmanpour R., Bugg T. D., FEBS J. 2013, 280, 2097–2104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Tang Y., Mu A., Zhang Y., Zhou S., Wang W., Lai Y., Zhou X., Liu F., Yang X., Gong H., Wang Q., Rao Z., Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A 2021, 118(16), e2025658118. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2025658118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. McHugh C. A., Fontana J., Nemecek D., Cheng N., Aksyuk A. A., Heymann J. B., Winkler D. C., Lam A. S., Wall J. S., Steven A. C., Hoiczyk E., EMBO J. 2014, 33, 1896–1911. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. He D., Hughes S., Vanden-Hehir S., Georgiev A., Altenbach K., Tarrant E., Mackay C. L., Waldron K. J., Clarke D. J., Marles-Wright J., Elife 2016, 5, e18972. doi: 10.7554/eLife.18972. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. He D., Piergentili C., Ross J., Tarrant E., Tuck L. R., Mackay C. L., McIver Z., Waldron K. J., Clarke D. J., Marles-Wright J., Biochem. J. 2019, 476, 975–989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Andreas M. P., Giessen T. W., MethodsX 2022, 9, 101787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Wiryaman T., Toor N., J. Struct. Biol. X 2022, 6, 100062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Chmelyuk N. S., Oda V. V., Gabashvili A. N., Abakumov M. A., Biochemistry (Mosc) 2023, 88, 35–49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Quinton A. R., McDowell H. B., Hoiczyk E., Adv. Appl. Microbiol. 2023, 125, 1–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. McDowell H. B., Hoiczyk E., J. Bacteriol. 2022, 204, e0034621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Rodriguez J. M., Allende-Ballestero C., Cornelissen J., Caston J. R., Nanomaterials (Basel) 2021, 11 (6), 1467. doi: 10.3390/nano11061467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Jones J. A., Giessen T. W., Biotechnol. Bioeng. 2021, 118, 491–505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Gabashvili A. N., Chmelyuk N. S., Efremova M. V., Malinovskaya J. A., Semkina A. S., Abakumov M. A., Biomolecules 2020, 10(6), 966. doi: 10.3390/biom10060966. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Demchuk A. M., Patel T. R., Biotechnol. Adv. 2020, 41, 107547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Giessen T. W., Silver P. A., Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 2017, 46, 42–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Giessen T. W., Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol. 2016, 34, 1–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Shabb J. B., Corbin J. D., J. Biol. Chem. 1992, 267, 5723–5726. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Eren E., Wang B., Winkler D. C., Watts N. R., Steven A. C., Wingfield P. T., Structure 2022, 30, 551–563 e554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.C. A. Dutcher, M. P. Andreas, T. W. Giessen, bioRxiv 2024.04.25.591138.

- 50. Abramson J., Adler J., Dunger J., Evans R., Green T., Pritzel A., Ronneberger O., Willmore L., Ballard A. J., Bambrick J., Bodenstein S. W., Evans D. A., Hung C. C., O'Neill M., Reiman D., Tunyasuvunakool K., Wu Z., Zemgulyte A., Arvaniti E., Beattie C., Bertolli O., Bridgland A., Cherepanov A., Congreve M., Cowen-Rivers A. I., Cowie A., Figurnov M., Fuchs F. B., Gladman H., Jain R., Khan Y. A., Low C. M. R., Perlin K., Potapenko A., Savy P., Singh S., Stecula A., Thillaisundaram A., Tong C., Yakneen S., Zhong E. D., Zielinski M., Zidek A., Bapst V., Kohli P., Jaderberg M., Hassabis D., Jumper J. M., Nature 2024, 630, 493–500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Mistry J., Chuguransky S., Williams L., Qureshi M., Salazar G. A., Sonnhammer E. L. L., Tosatto S. C. E., Paladin L., Raj S., Richardson L. J., Finn R. D., Bateman A., Nucleic Acids Res. 2021, 49, D412–D419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Liu Y., Demina T. A., Roux S., Aiewsakun P., Kazlauskas D., Simmonds P., Prangishvili D., Oksanen H. M., Krupovic M., PLoS Biol. 2021, 19, e3001442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Wikoff W. R., Liljas L., Duda R. L., Tsuruta H., Hendrix R. W., Johnson J. E., Science 2000, 289, 2129–2133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Pietilä M. K., Laurinmäki P., Russell D. A., Ko C.-C., Jacobs-Sera D., Hendrix R. W., Bamford D. H., Butcher S. J., Pietilä M. K., Laurinmäki P., Russell D. A., Ko C.-C., Jacobs-Sera D., Hendrix R. W., Bamford D. H., Butcher S. J., Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2013, 110(26), 10604–9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1303047110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Baker M. L., Jiang W., Rixon F. J., Chiu W., J. Virol. 2005, 79, 14967–14970. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Suhanovsky M. M., Teschke C. M., Virology 2015, 479–480, 487–497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Zhou Z. H., Hui W. H., Shah S., Jih J., O'Connor C. M., Sherman M. B., Kedes D. H., Schein S., Structure 2014, 22, 1385–1398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Caspar D. L., Klug A., Cold Spring Harbor Symp. Quant. Biol. 1962, 27, 1–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Johnson J. E., Speir J. A., J. Mol. Biol. 1997, 269, 665–675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Wiryaman T., Toor N., IUCrJ 2021, 8, 342–350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. LaFrance B. J., Cassidy-Amstutz C., Nichols R. J., Oltrogge L. M., Nogales E., Savage D. F., Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 22810. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Zinelli R., Soni S., Cornelissen J., Michel-Souzy S., Nijhuis C. A., Biomolecules 2023, 13(1), 174. doi: 10.3390/biom13010174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Fokine A., Leiman P. G., Shneider M. M., Ahvazi B., Boeshans K. M., Steven A. C., Black L. W., Mesyanzhinov V. V., Rossmann M. G., Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A 2005, 102, 7163–7168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Yap M. L., Rossmann M. G., Future Microbiol. 2014, 9, 1319–1327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Ross J., McIver Z., Lambert T., Piergentili C., Bird J. E., Gallagher K. J., Cruickshank F. L., James P., Zarazua-Arvizu E., Horsfall L. E., Waldron K. J., Wilson M. D., Mackay C. L., Basle A., Clarke D. J., Marles-Wright J., Sci. Adv. 2022, 8, eabj4461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Loncar N., Rozeboom H. J., Franken L. E., Stuart M. C. A., Fraaije M. W., Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2020, 529, 548–553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Jones J. A., Andreas M. P., Giessen T. W., Biomacromolecules 2023, 24, 1388–1399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Kwon S., Andreas M. P., Giessen T. W., ACS Nano. 2024, 18(37), 25740–25753. doi: 10.1021/acsnano.4c08186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Williams E. M., Jung S. M., Coffman J. L., Lutz S., ACS Synth. Biol. 2018, 7, 2514–2517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Jenkins M. C., Lutz S., ACS Synth. Biol. 2021, 10, 857–869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Szyszka T. N., Andreas M. P., Lie F., Miller L. M., Adamson L. S. R., Fatehi F., Twarock R., Draper B. E., Jarrold M. F., Giessen T. W., Lau Y. H., Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A 2024, 121, e2321260121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Duda R. L., Teschke C. M., Curr. Opin. Virol. 2019, 36, 9–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Fokine A., Chipman P. R., Leiman P. G., Mesyanzhinov V. V., Rao V. B., Rossmann M. G., Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A 2004, 101, 6003–6008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Morais M. C., Choi K. H., Koti J. S., Chipman P. R., Anderson D. L., Rossmann M. G., Mol. Cell 2005, 18, 149–159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Parent K. N., Khayat R., Tu L. H., Suhanovsky M. M., Cortines J. R., Teschke C. M., Johnson J. E., Baker T. S., Structure 2010, 18, 390–401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Chen D. H., Baker M. L., Hryc C. F., DiMaio F., Jakana J., Wu W., Dougherty M., Haase-Pettingell C., Schmid M. F., Jiang W., Baker D., King J. A., Chiu W., Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A 2011, 108, 1355–1360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Parent K. N., Gilcrease E. B., Casjens S. R., Baker T. S., Virology 2012, 427, 177–188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Parent K. N., Tang J., Cardone G., Gilcrease E. B., Janssen M. E., Olson N. H., Casjens S. R., Baker T. S., Virology 2014, 464–465, 55–66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Homa F. L., Huffman J. B., Toropova K., Lopez H. R., Makhov A. M., Conway J. F., J Mol. Biol. 2013, 425, 3415–3428. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. Hui W. H., Tang Q., Liu H., Atanasov I., Liu F., Zhu H., Zhou Z. H., Protein Cell 2013, 4, 833–845. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. Zhou Z. H., Chen D. H., Jakana J., Rixon F. J., Chiu W., J. Virol. 1999, 73, 3210–3218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82. Zhou Z. H., Dougherty M., Jakana J., He J., Rixon F. J., Chiu W., Science 2000, 288, 877–880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83. Dai X., Zhou Z. H., Science 2018, 360 (6384), eaao7298. doi: 10.1126/science.aao7298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84. Duda R. L., Martincic K., Hendrix R. W., J. Mol. Biol. 1995, 247, 636–647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85. Effantin G., Boulanger P., Neumann E., Letellier L., Conway J. F., J. Mol. Biol. 2006, 361, 993–1002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86. Giessen T. W., Silver P. A., Nat. Microbiol. 2017, 2, 17029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87. Berman H. M., Ten Eyck L. F., Goodsell D. S., Haste N. M., Kornev A., Taylor S. S., Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A 2005, 102, 45–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88. Kannan N., Wu J., Anand G. S., Yooseph S., Neuwald A. F., Venter J. C., Taylor S. S., Genome. Biol. 2007, 8, R264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89. Passner J. M., Schultz S. C., Steitz T. A., J. Mol. Biol. 2000, 304, 847–859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90. Popovych N., Tzeng S. R., Tonelli M., Ebright R. H., Kalodimos C. G., Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A 2009, 106, 6927–6932. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91. Tracey J. C., Coronado M., Giessen T. W., Lau M. C. Y., Silver P. A., Ward B. B., Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 20122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92. Kartal B., Keltjens J. T., Trends Biochem. Sci. 2016, 41, 998–1011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93. van Niftrik L., Antonie Van Leeuwenhoek 2013, 104, 489–497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94. Kuenen J. G., Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2008, 6, 320–326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95. van Niftrik L., Geerts W. J., van Donselaar E. G., Humbel B. M., Yakushevska A., Verkleij A. J., Jetten M. S., Strous M., J. Struct. Biol. 2008, 161, 401–410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96. Strous M., Pelletier E., Mangenot S., Rattei T., Lehner A., Taylor M. W., Horn M., Daims H., Bartol-Mavel D., Wincker P., Barbe V., Fonknechten N., Vallenet D., Segurens B., Schenowitz-Truong C., Medigue C., Collingro A., Snel B., Dutilh B. E., Op den Camp H. J., van der Drift C., Cirpus I., van de Pas-Schoonen K. T., Harhangi H. R., van Niftrik L., Schmid M., Keltjens J., van de Vossenberg J., Kartal B., Meier H., Frishman D., Huynen M. A., Mewes H. W., Weissenbach J., Jetten M. S., Wagner M., Le Paslier D., Nature 2006, 440, 790–794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]