Abstract

Background

Gasdermin D (GSDMD) is a key effector molecule that activates pyroptosis through its N terminal domain (GSDMD-NT). However, the roles of GSDMD in colorectal cancer (CRC) have not been fully explored. The role of the full-length GSDMD (GSDMD-FL) is also not clear. In this study, we observed that GSDMD modulates CRC progression through other mechanisms in addition to activating GSDMD-NT.

Methods

Clinical CRC samples and human-derived CRC cell lines were used in this study. GSDMD expression was evaluated by RT-qPCR, Western blot and immunohistochemical (IHC) analysis. GSDMD knockdown and overexpression stable cell lines were established by Lentiviral transduction. CCK-8 assay, flow cytometry analysis for cell cycle, Transwell assay, and cell scratch assay were performed in vitro to explore the impact of GSDMD on CRC progression. Mouse subcutaneous transplantation tumor models were constructed to assess the role of GSDMD in vivo. Intestinal epithelial cell (IEC)-specific knockout of Gsdmd mice (GsdmdΔIEC) was used to evaluate the effect of GSDMD on intestinal adenoma formation in AOM-DSS and Apcmin/+ mouse models. RNA sequencing was performed to explore the regulatory pathways associated with the role of GSDMD in CRC cells. Co-Immunoprecipitation (CO-IP), Western blot and immunofluorescence (IF) were conducted to investigate the interactions between GSDMD and EGFR. Exogenous addition of Gefitinib was used to evaluate the effect of GSDMD on autophosphorylation of EGFR at the Tyr1068 site.

Results

GSDMD was highly expressed in clinical CRC tissues and human-derived CRC cell lines. GSDMD knockdown inhibited the viability, cell cycle changes, invasion ability and migration ability of CRC cell lines in vitro and vivo, whereas GSDMD overexpression had the opposite effects. Intestinal adenoma development was reduced in GsdmdΔIEC mice in both AOM-DSS and Apcmin/+ mouse models. GSDMD-FL interacted with EGFR and promoted CRC progression by inducing autophosphorylation of EGFR at the Tyr1068 site, subsequently activating ERK1/2. Exogenous Gefitinib abrogated the tumorigenic properties of GSDMD.

Conclusions

GSDMD-FL promotes CRC progression by inducing EGFR autophosphorylation at the Tyr1068 site, subsequently activating the downstream ERK1/2. Inhibition of GSDMD is a potential strategy for the treatment of colorectal cancer.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s12967-024-05984-0.

Keywords: CRC, EGFR Tyr1068, ERK1/2, GSDMD-FL

Highlights

What is already known on this topic?

•GSDMD-NT is a key effector molecule for activating pyroptosis.

•GSDMD has a dual role in colitis-associated cancer (CAC) progression.

What this Study Adds?

•GSDMD-FL has a nonpyroptotic role in CRC progression.

•GSDMD interacts with EGFR.

•GSDMD causes EGFR Tyr1068 phosphorylation and ERK1/2 phosphorylation.

How might this study affect research, practice, or policy?

•This study indicates that targeting GSDMD is a potential strategy for treating colorectal cancer.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s12967-024-05984-0.

Introduction

Gasdermin D (GSDMD) is a key effector molecule that activates pyroptosis. Activated inflammasomes, such as NLRP3, cleave several inflammatory caspases and activate them [1]. Subsequently, these inflammatory caspases cleave GSDMD, releasing its N-terminal domain (GSDMD-NT). The GSDMD-NT domain is recruited to the plasma membrane to form the pores, promoting inflammatory cellular pyroptosis and inducing the release of inflammatory factors [2]. Several studies report that GSDMD has a significant role in various diseases, including different cancer types [3], infections [4] and inflammatory diseases [5]. These studies demonstrated that GSDMD plays a tumor suppressor role by promoting tumor cell pyroptosis through the GSDMD-NT domain. Some studies also revealed that GSDMD can induce anti-tumor immunity in immune cells [6], a critical step in tumor progression and treatment [7, 8]. The role of GSDMD in CRC has not been fully elucidated. Some studies demonstrate that GSDMD inhibits CRC development through the activation of pyroptosis by the GSDMD-NT domain [9]. However, previous findings also indicate that GSDMD activation can trigger colorectal tumorigenesis [10], implying that GSDMD may have a dual role in CRC progression.

CRC is a cancer type with a high incidence and mortality rate both globally and in China [11]. GLOBOCAN 2022 indicates that colorectal cancer incidence ranks third globally, following lung and breast cancer. The China’s Cancer Center 2024 data demonstrate that colorectal cancer is the second leading type of cancer in China [12]. Currently, surgical resection is the primary CRC treatment strategy, supplemented by a combination of adjuvant therapy, neoadjuvant chemotherapy, radiotherapy, targeted therapy, and immunotherapy [13]. Notably, approximately 25% of colorectal cancer cases are diagnosed during advanced stages when metastasis has occurred. Approximately 20% of these cases are inoperable due to metastasis, resulting in poor prognosis [14]. Currently, there are no effective therapeutic strategies for this group of patients. Therefore, it is imperative to explore novel and effective strategies for CRC treatment further.

This study found an unexpected role of GSDMD-FL in CRC development. Most previous studies evaluated the role of GSDMD-NT in CRC progression. In this study, we observed that GSDMD knockdown inhibited CRC cell proliferation without producing the GSDMD-NT domain. In addition, overexpressing GSDMD can promote CRC progression without producing the GSDMD-NT domain. The findings indicated that IEC-derived Gsdmd knockout inhibited intestinal adenoma development in experimental CRC models. CRC development involves several pathways and molecules [15], including epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR). EGFR overactivation is associated with colorectal cancer development and progression [16]. EGFR testing has become a standard practice to guide treatment decisions for colorectal cancer. Therapies targeting EGFR, including the EGFR tyrosine kinase inhibitors (EGFR-TKI), have been developed [17]. However, some patients are insensitive or resistant to EGFR-TKI treatment [18]. Consequently, further research is required to explore more effective treatment strategies. Therefore, medical research should focus on the world to communicate and exchange medical research to advance clinical goals [19, 20]. In this study, we observed that GSDMD-FL interacts with EGFR and promotes its phosphorylation at the Tyr1068 site, ultimately activating ERK1/2. Exogenous Gefitinib inhibited the pro-oncogenic ability of GSDMD. These findings highlight novel pro-oncogenic pathways modulated by GSDMD-FL, indicating that GSDMD is a potential target for CRC treatment.

Materials and methods

Animal models

In this study, all mice were reared in an SPF grade animal-controlled environment. Three mouse models of colorectal cancer were established in this study. The first model comprised the cell-derived xenografts established using six- to eight-week-old BALB/c-Nude mice. Thus, HCT116 stable cell lines (1–5 × 106/100 µL) were subcutaneously injected into the back of the BALB/c-Nude mice.

The azoxymethane (AOM)-dextran sulfate sodium (DSS) mouse model [21] was established by crossing C57BL/6J Gsdmdflox/flox mice with Villin-cre mice to achieve IEC-specific knockout of Gsdmd mice (GsdmdΔIEC) [22]. Based on previous conditional knockout mouse studies, Gsdmdflox/flox was considered the control group, and GsdmdΔIEC was the knockout group [23]. In this mouse model, Gsdmdflox/flox (n = 4) and GsdmdΔIEC (n = 5) were first injected intraperitoneally with AOM (10 mg/kg). At two-week intervals, the mice were fed for one week with water containing DSS (1.8%).

The Apcmin/+ mouse model [24] was established by crossing C57BL/6J Apcmin/+ mice with Gsdmdflox/flox and GsdmdΔIEC mice to obtain Gsdmdflox/flox;Apcmin/+ (n = 6) and GsdmdΔIEC;Apcmin/+ (n = 6) mice, respectively. The Ethics Committee of Laboratory Animal Center, Jiangnan University approved the animal breeding and experiments (JN.No20231115m0330301[554], JN.No20231215m0620701[610]).

Human samples

This study used 56 pairs of colorectal cancer and corresponding paracancerous tissues (≥ 5 cm from the tumor margins). The tissues, collected and recorded in detail, were definitively diagnosed as colorectal cancer by a pathologist after surgery. The patients were informed and signed consent forms, and the samples were collected with the consent of the Medical Ethics Committee of the People’s Hospital of Dezhou City, Dezhou, China, with the ethical review approval number 20,210,108.

Cell culture

Human-derived colorectal cancer cell lines, including HT29, HCT116, Caco2, Lovo, SW620, and normal colonic epithelial cell lines NCM460, were purchased from the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC). NCM460 cell line was cultured in 1640 medium (Hyclone, USA), and the other cell lines were cultured in DMEM medium (Hyclone, USA), containing 10% fetal bovine serum (Gibco, USA) and 1% penicillin-streptomycin (Hyclone, USA).

siRNA transfection

Six small interfering RNAs (siRNAs) targeting the GSDMD coding sequence (CDS) were purchased from Hanheng Biotechnology (Shanghai, China). siRNA transfection was performed using Lipo8000™ Transfection Reagent (Beyotime, Shanghai, China) in a six-well plate. Briefly, the medium was replaced with a fresh, complete medium before transfection, following the manufacturer’s instructions. The transfection mixture (125 µL of antibiotic- and serum-free medium, 100 pmol of siRNA, and 4 µl of Lipo8000™ Transfection Reagent per well) was added to whole wells dropwise and incubated at room temperature for 20 min. The mixture was further transfected and incubated for approximately 2 days before detecting the siRNA down-regulation efficiency on target genes using RT-qPCR and Western blot. The six GSDMD siRNAs sequences are:

siGSDMD-1: GCAGGAGCUUCCACUUCUA TT (sense);

UAGAAGUGGAAGCUCCUGC TT (antisense);

siGSDMD-2: GAAUGUGUACUCGCUGAGUGU TT (sense);

ACACUCAGCGAGUACACAUUC TT (antisense);

siGSDMD-3: CCUUCUCUUCCCGGAUAAGAA TT (sense);

UUCUUAUCCGGGAAGAGAAGG TT (antisense);

siGSDMD-4: GGAGACCAUCUCCAAGGAATT (sense);

UUCCUUGGAGAUGGUCUCCTT (antisense);

siGSDMD-5: GGAACUCGCUAUCCCUGUUTT (sense);

AACAGGGAUAGCGAGUUCCTT (antisense);

siGSDMD-6: CGUGGUGACUGAGGUGCUATT (sense);

UAGCACCUCAGUCACCACGTT (antisense).

Lentiviral transduction

Lentiviral solutions containing HBLV-h-GSDMD-3xflag plasmid and GSDMD-specific shRNA plasmid (harboring puromycin resistance and GFP fluorescence) were purchased from Hanheng Biotechnology (Shanghai, China). After achieving a 50% cell density, the lentiviral solution and polybrene (5 µg/mL) were mixed with 1/2 of the original medium volume of the complete medium and infected the cells. The complete medium was replenished after 4 h and replaced with a fresh complete medium after 24 h. GFP fluorescence intensity was evaluated after 48 h. After achieving a 60–70% cell density, the complete medium containing an appropriate puromycin concentration was replaced to screen the cells and construct stable cell lines for subsequent experiments. shGSDMD sequence: CGUGGGUGACUGAGGUGCUATT (sense); UAGCACCUCAGUCACCACGTT (antisense).

Reverse transcription quantitative PCR (RT-qPCR)

Total RNA was extracted from tissues or cells using the FastPure Cell/Tissue Total RNA Isolation Kit V2 (Vazyme, Nanjing, China). The RNA quality and concentration were determined. The RNA was reverse transcribed to obtain cDNA using the RT SuperMix for qPCR (Vazyme, Nanjing, China), which was used to perform RT-qPCR using the Taq Pro Universal SYBR Qpcr Master Mix (Vazyme, Nanjing, China). Related primer sequences:

h-GSDMD forward: GAGTGTGGCCTAGAGCTGG;

h-GSDMD reverse: GGCTCAGTCCTGATAGCAGTG;

β-actin forward: TGACGTGGACATCCGCAAAG;

β-actin reverse: CTGGAAGGTGGACAGCGAGG;

h-EGFR forward: AGGCACGAGTAACAAGCTCAC;

h-EGFR reverse: ATGAGGACATAACCAGCCACC.

Western blotting

Total proteins from cells and tissues were extracted using Western and IP lysates (Meilunbio, Shanghai), phosphatase inhibitor mixtures, and PMSF (Beyotime, Shanghai). Protein samples with consistent concentrations were used to perform SDS-PAGE. Related consumables and reagents include SDS-PAGE gels (Yeasen, Nanjing, China), PVDF membranes (Millipore, USA), 5% skimmed milk (BD, America), 5% BSA (Solarbio, Beijing), ECL chromatography (Yeasen, Nanjing). The relevant primary antibodies include GSDMDC1 (1:1000, NBP2-80427, Rabbit, Novus Biologicals, America), GSDMD (1:1000, 39754, Rabbit, Cell Signaling Technology, America), Anti-cleaved N-terminal GSDMD (1:1000, ab215203, Rabbit, Abcam, UK), Gasdermin D (N terminal) (1:1000, HA721144, Rabbit, Huabio, Hangzhou), EGFR (1:5000, 66455-1-Ig, Mouse, Proteintech, Wuhan), EGFR (1:1000, WL0682a, Rabbit, Wanleibio, Shenyang), phospho-EGFR (Tyr1068) (1:1000, 3777 S, Rabbit, Cell Signaling Technology, America), phospho-EGFR (Tyr1045) (1:1000, 2237 S, Rabbit, Cell Signaling Technology, America), phospho-EGFR (Tyr1173) (1:1000, 4757 S, Rabbit, Cell Signaling Technology, America), Erk1/2 (1:1000, 4695 S, Rabbit, Cell Signaling Technology, America), phospho-Erk1/2 (1:1000, 4370 S, Rabbit, Cell Signaling Technology, America), GAPDH (1:50000, 60004-1-Ig, Mouse, Proteintech, Wuhan). The secondary antibodies were horseradish peroxidase-labeled rabbit/mouse secondary antibodies (1:5000, Univ, Shanghai, China).

Hematoxylin and eosin (HE) and immunohistochemical (IHC) staining

The tissue samples were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde overnight, rinsed with running water for half an hour, then dehydrated, embedded and sectioned. The sections were dewaxed, hydrated and stained with hematoxylin-eosin staining solution (Yulu, Nanchang). For IHC staining, the sections were dewaxed, hydrated, and blocked with endogenous peroxidase. Antigen repair was also performed. Subsequently, the sections were incubated with primary antibodies overnight at 4 °C and further incubated with horseradish peroxidase-labeled secondary antibody (Absin, Shanghai, China). Enhanced DBA Display Kit (Solarbio, Beijing, China) was used to detect proteins in the sections based on the various antibodies. Relevant primary antibodies include GSDMDC1 (1:100, NBP2-80427, Rabbit, Novus Biologicals, America), Ki-67 (1:50, AB16667, Rabbit, Abcam, UK).

Immunofluorescence (IF)

After cell attachment, cells were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde, then sequentially permeabilized, blocked, and incubated with primary antibody overnight at 4 ℃. Subsequently, the cells were incubated with secondary antibody, followed by DAPI staining using DAPI (40728ES03, Yeasen, Nanjing). The samples were stored away from light, and the fluorescence signal was detected using a fluorescence microscope. Related reagents include 1% Triton X-100 (Beyotime, Shanghai, China) and 10% normal goat serum (Gibco, USA). The primary antibodies include GSDMD (1:100, 39754, Rabbit, Cell Signaling Technology, America) and EGFR (1:100, 66455-1-Ig, Mouse, Proteintech, Wuhan). The secondary antibodies include Goat anti-Rabbit IgG-Cy3 Antibody (1:100, abs20024, Absin, Shanghai, China), Goat anti-Mouse IgG-FITC Antibody (1:100, abs20012, Absin, Shanghai, China).

Co-immunoprecipitation (CO-IP)

Protein samples were prepared, and the concentration was determined as described in the western blotting section. Antigen-antibody binding samples were prepared using the Protein A/G Magnetic Beads Reagent (MCE, USA) following the manufacturer’s instructions. The supernatants were subjected to SDS-PDGA. The primary antibodies include GSDMD (1:100, 39754, Rabbit, Cell Signaling Technology, America), Anti-rabbit IgG (1:100, 7074P2, Rabbit, Cell Signaling Technology, America) and EGFR (1:50, WL0682a, Rabbit, Wanleibio, Shenyang).

Cell proliferation CCK-8 assay

Cells were transferred to three 96-well plates at a density of 1 × 103 cells per well. Subsequently, 10 µL of the Cell Counting Kit (CCK8) reagent (Yessen, Nanjing, China) was added to each well at 24, 48, and 72 h, respectively. The samples were incubated for 1 h at 37 °C in an incubator, and the absorbance was measured at 450 nm using an enzyme labeling instrument (Thermo, America) to compare the cell viability.

Flow cytometry analysis for cell cycle

Cells were fixed with 75% ethanol overnight at 4 °C and then resuspended with PI/RNase Staining Buffer (BD, USA). Subsequently, the cells were incubated at room temperature for 15 min away from light, and flow cytometry (BD FACSArica III, BD, USA) was performed.

Transwell assay

Serum-free cell suspension was added to the upper chamber of the Transwell plate and a complete medium containing 20% serum was added to the lower chamber. The samples were incubated for 48–72 h and stained with crystal violet working solution (Solaibio, Beijing, China). Subsequently, 3–5 fields of view were randomly selected under the microscope and Image J software was used for statistical analysis.

Cell scratch assay

Three horizontal lines were drawn on the bottom of the dish with a marker, and then a monolayer of cells was spread in a six-well plate after achieving a 90% cell density. Three lines were vertically and rapidly scratched using a 200 µL pipette tip. Fields of view were randomly selected at the top and bottom of the intersections of the scratches and the horizontal lines for observation and imaging under an Inverted microscope (Zeiss, Germany). The medium was replaced with low serum medium, and photographs were taken during incubation at 0, 24, 48, and 72 h. The fields of view were consistent each time. The rate of change of scratch area over time and the percentage of wound healing were determined using Image J software.

Statistical analysis

Between-group differences were performed using the Student’s t-test, and survival curve analysis was performed using the Log-rank test in GraphPad Prism software. The data are presented as mean values ± SD or SEM of three independent experiments. Significant differences are indicated by *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001 and ****p < 0.0001. The IHC, IF, Transwell assay, and cell scratch assay data were analyzed using Image J software.

Results

GSDMD is highly expressed in human colorectal cancer (CRC) samples and cell lines

In this study, we obtained clinical CRC samples and evaluated the GSDMD expression level to explore the role of GSDMD in CRC. The RT-qPCR (Fig. S1A), Western blot (Fig. S1B), and IHC (Fig. S1C) were used to analyze clinical CRC and normal colon samples. The results revealed that GSDMD was significantly upregulated in CRC samples compared with corresponding paracancerous normal colon samples. Moreover, the RT-qPCR (Fig. S1D) and Western blot (Fig. S1E) analysis of several human-derived CRC and the control NCM460 cell lines showed that GSDMD mRNA and proteins are upregulated in CRC than the control cell line.

GSDMD knockdown and overexpression stable cell lines were constructed to further investigate the role of GSDMD in human-derived CRC cell lines. We selected the HCT116 cell line, which exhibited the highest relative expression of GSDMD and the Caco2 cell line, exhibiting the lowest relative expression of GSDMD for subsequent analyses. Before constructing the knockdown stable cell lines, we selected six siRNAs targeting the CDS of GSDMD, performed siRNA transfection, and detected the knockdown efficiency of siRNAs by RT-qPCR (Fig. S2A) and Western blot (Fig. S2B). The results showed that only siGSDMD-6 could effectively knock down the GSDMD mRNA and protein expression in HCT116 cells. We, therefore, constructed of GSDMD-specific shRNA plasmid based on the sequence of siGSDMD-6. We transfected GSDMD-specific shRNA plasmid in the HCT116 cell line to establish a stable cell line with GSDMD knockdown (shGSDMD stable cell lines and shNC stable cell lines). Furthermore, we transfected the HBLV-h-GSDMD-3xflag plasmid and the HBLV empty vector plasmid in the Caco2 cell line to establish a stable cell line with GSDMD overexpression (HBLV-h-GSDMD stable cell lines and HBLV stable cell lines). The GSDMD knockdown and overexpression were verified after transfection by fluorescence microscopy (Fig. S2C and F), RT-qPCR (Fig. S2D and G), and Western blot (Fig. S2E and H).

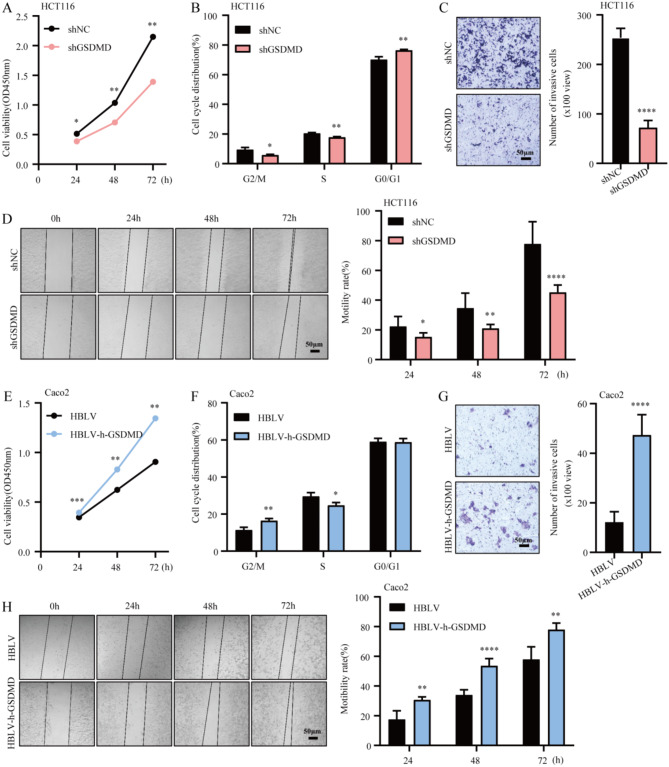

GSDMD promotes proliferation of human-derived CRC cells in vitro and in vivo

We performed the CCK-8 assay to explore the role of GSDMD on cell proliferation and flow cytometry to determine its function in cell cycle using HCT116 stable cell line with GSDMD knocked down. The results revealed that the knockdown of GSDMD significantly inhibited cell viability (Fig. 1A) and increased the proportion of cells arrested at the G0/G1 phase (Fig. 1B). Transwell assay and cell scratch assay demonstrated that the cell invasion ability (Fig. 1C) and migration ability (Fig. 1D) of the shGSDMD group were significantly inhibited compared to the shNC group. These findings imply that GSDMD has pro-carcinogenic effects on CRC cells. Functional assays using Caco2 stable cell line with overexpressed GSDMD showed that GSDMD overexpression promoted cell viability (Fig. 1E), increased the proportion of cells arrested at G2 (Fig. 1F), and promoted invasion ability (Fig. 1G) and migration ability (Fig. 1H) of Caco2 cell line. These results indicate that GSDMD promotes the proliferation of CRC cells in vitro. We performed GSDMD compensation by transiently transfecting h-GSDMD plasmid in the HCT116 stable cell line, further characterizing the above roles of GSDMD in human CRC cells. GSDMD compensation was verified by RT-qPCR (Fig. S3A) and Western blot (Fig. S3B) analysis. Functional assays showed that the GSDMD rescue group (shGSDMD-RES) enhanced cell viability (Fig. S3C) and invasion ability (Fig. S3D), decreased the proportion of cells arrested at the G0/G1 phase (Fig. S3E) than the shGSDMD group.

Fig. 1.

GSDMD promotes the development of human-derived CRC cell lines in vitro. Knocking down GSDMD in HCT116 cell line, and overexpressing GSDMD in Caco2 cell line. A-D The cell viability (A), cell cycle changes (B), invasion ability (x100 views) (C), and migration ability (x50 views) (D) of HCT116 cell lines were tested by CCK-8 assay, flow cytometry for cell cycle, Transwell assay, and cell scratch assay, respectively. E-H The cell viability (E), cell cycle changes (F), invasion ability (x100 views) (G), and migration ability (x50 views) (H) of Caco2 cell lines were tested by CCK-8 assay, flow cytometry for cell cycle, Transwell assay, and cell scratch assay, respectively. All assays verified three times. Data are presented as mean ± SEM. Differences between the two groups were analyzed using the Student’s t-test. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, ****P < 0.0001

In addition, we constructed mouse subcutaneous transplantation tumor models using HCT116 stable cell line after GSDMD knockdown to explore whether GSDMD promoted CRC cell proliferation in vivo. The results showed that GSDMD knockdown reduced the size (Fig. 2A) and weight (Fig. 2C) of the mouse tumors, but the weight of the mice did not change (Fig. 2B). IHC analysis showed that the expression of GSDMD and ki67 positivity in transplanted tumors were downregulated after GSDMD knockdown (Fig. 2D and E). These results demonstrate that GSDMD promotes the proliferation of CRC cells and increases CRC malignancy in vivo. In summary, GSDMD promotes the proliferation of human-derived CRC cells in vitro and in vivo.

Fig. 2.

GSDMD promotes the growth of CRC cell lines in vivo. A-E Subcutaneous transplantation tumor mouse models were constructed with HCT116 stable cell line after GSDMD knockdown. A Representative images of subcutaneous transplantation tumors (n = 5). B The body weight of mice with subcutaneous tumor transplantation. C The weight of subcutaneous transplantation tumors. D-E The positive rate of GSDMD (D) and Ki67 (E) in subcutaneous transplantation tumors were detected by IHC assay. G-K The results were derived from AOM-DSS mouse model. F, G GSDMD and GSDMD-NT knockout efficiency was confirmed by Western blotting. H Mouse body weight changes during AOM-DSS modeling. I Representative images of tumour bearing intestine and statistics of intestinal tumor number. J The positive rate of Ki67 in mouse colon tissue was detected by IHC assay. K HE staining of AOM-DSS mouse colon tissue. Data are presented as mean ± SEM. Differences between the two groups were analyzed using the Student’s t-test. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, ****P < 0.0001

Epithelial GSDMD promotes tumor progression in CRC mice models

We established IEC-specific knockout of Gsdmd mice models (GsdmdΔIEC) to explore the role of IEC-derived GSDMD in CRC development in vivo. GSDMD and GSDMD-NT knockout efficiency was confirmed by Western blotting (Fig. 2F and G). The effects of Gsdmd knockout in the AOM-DSS mouse model, a typical experimental CRC mouse model, were explored. The body weights of mice were recorded during the establishment of the AOM-DSS model, indicating the reduction in weight for both Gsdmdflox/flox and GsdmdΔIEC mice during DSS administration compared to the period before DSS administration. Notably, the weight loss was more significant in Gsdmdflox/floxmice (Fig. 2H). The results showed that GsdmdΔIEC mice had significantly fewer intestinal adenomas in the small intestine and colon compared to Gsdmdflox/flox mice (Fig. 2I). HE and IHC-Ki67 staining of mouse intestinal tissues demonstrated that intestinal adenomas were less malignant in GsdmdΔIEC mice than in Gsdmdflox/flox mice (Fig. 2J and K). In conclusion, epithelial GSDMD can promote tumor progression in experimental CRC development.

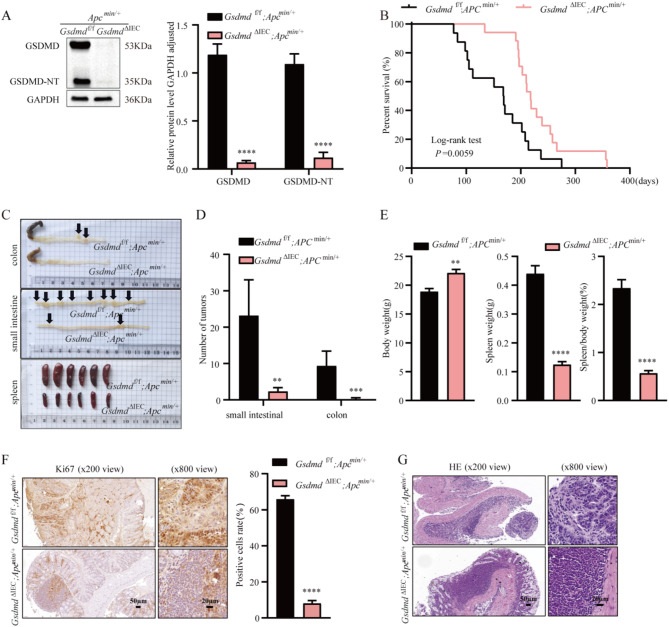

Notably, the AOM-DSS mouse model is an inflammation-associated experimental CRC mouse model [25]. Therefore, we explored whether the effects observed were indirectly caused by the impact of GSDMD on intestinal inflammation or if they were due to the direct promotion of tumor cell progression by GSDMD. Subsequently, we crossed GsdmdΔIEC mice with Apcmin/+ mice to generate IEC-specific Gsdmd knockout mice in the context of Apcmin/+ (GsdmdΔIEC;Apcmin/+). Western blotting was performed to determine the GSDMD and GSDMD-NT knockout efficiency (Fig. 3A). The survival cycles of the model mice were recorded during the modeling period. The results showed that GsdmdΔIEC;Apcmin/+ mice had a relatively longer survival time compared to Gsdmdflox/flox;Apcmin/+ mice (Fig. 3B). Notably, this model presented similar results to the AOM-DSS model described above. The number of intestinal adenomas in the small intestine and colon was significantly reduced in GsdmdΔIEC;Apcmin/+ mice compared to Gsdmdflox/flox;Apcmin/+ mice (Fig. 3C and D). In addition, the spleen size and weight gain were significantly reduced in GsdmdΔIEC;Apcmin/+ mice compared to Gsdmdflox/flox;Apcmin/+ mice (Fig. 3C and E). Increased spleen size and weight are indicators of chronic anemia [26]. The degree of body weight loss was significantly reduced in GsdmdΔIEC;Apcmin/+ mice than Gsdmdflox/flox;Apcmin/+ mice (Fig. 3E). Anemia symptoms and weight loss are manifestations of end-stage cachexia in Apcmin/+ mice [27]. The present findings indicated that the degree of end-stage cachexia was significantly reduced in GsdmdΔIEC;Apcmin/+ mice. HE and IHC-Ki67 staining of mouse intestinal tissues showed that intestinal adenomas were less malignant in GsdmdΔIEC;Apcmin/+ mice compared to Gsdmdflox/flox;Apcmin/+ mice (Fig. 3F and G). This is primarily because Apcmin/+ mice model is a model of spontaneous experimental CRC [28], with intestinal adenomas developing independent of intestinal inflammatory factors. These results demonstrate that GSDMD is directly involved in the tumor progression in experimental CRC rather than solely affecting intestinal inflammation.

Fig. 3.

GSDMD plays a role in tumor progression in experimental CRC. A-G All results were derived from Gsdmdflox/flox;Apcmin/+ (n = 6) and GsdmdΔIEC;Apcmin/+ (n = 6) mice. A GSDMD and GSDMD-NT knockout efficiency was confirmed by Western blotting. B The survival cycles of mice were recorded. Data were analysed by Log-rank test in GraphPad Prism. C Representative images of tumour bearing intestine and spleen from Gsdmdflox/flox;Apcmin/+ and GsdmdΔIEC;Apcmin/+ mice. D The statistics of intestinal tumor number. E The mouse body weight, spleen weight and the ratio of spleen weight to body weight. F The positive rate of Ki67 in mouse colon tissue was detected by IHC assay. G HE staining of Apcmin/+ mouse colon tissue. Data are presented as mean ± SEM. Differences between the two groups were analyzed using the Student’s t-test. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, ****P < 0.0001

GSDMD knockdown impairs the activation of EGF receptor signaling

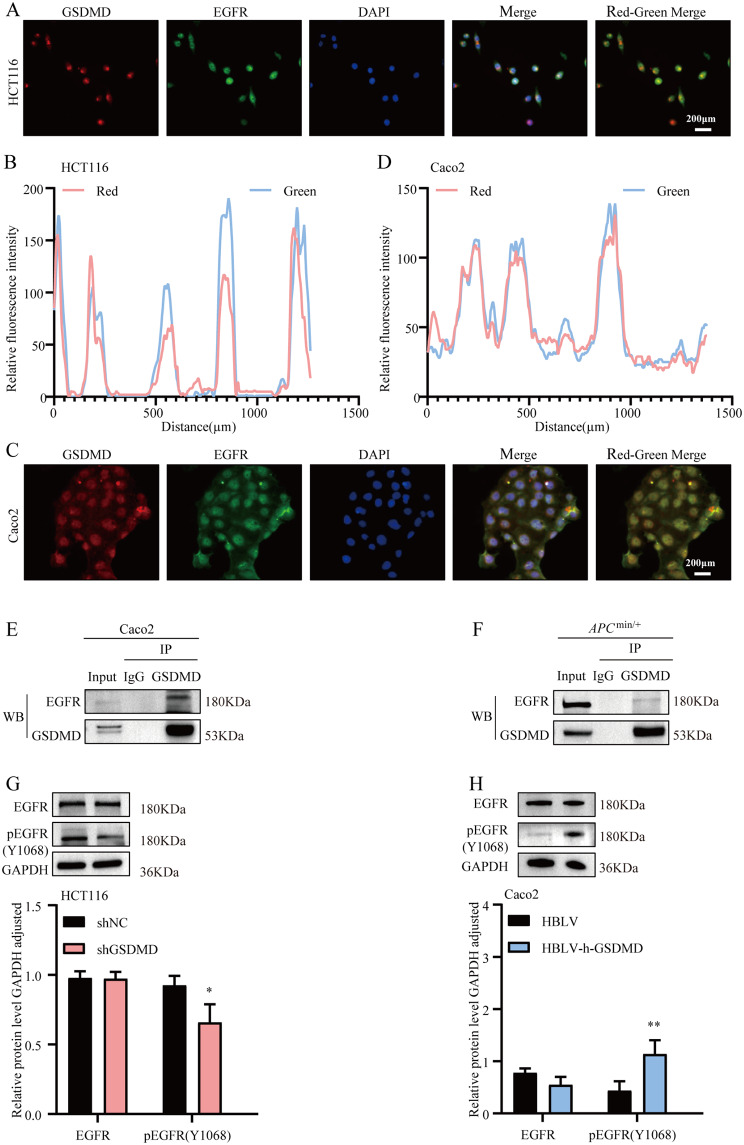

We performed RNA-Seq analysis and compared the transcription levels of various genes in a stable HCT116 cell line with GSDMD knockdown to explore the regulatory pathways associated with the role of GSDMD in CRC. The results showed that the expression of 42 genes was downregulated, and 145 genes were upregulated in the shGSDMD group compared to the shNC group (p-value < 0.05 and log2 fold change|>1) (Fig. 4A and B). GO/KEGG enrichment analysis demonstrated that GSDMD knockdown was associated with significant enrichment of the PPAR signaling pathway, Ras signaling pathway, PI3K-Akt signaling pathway and EGFR tyrosine kinase inhibitor resistance (Fig. 4C). The Ras and PI3K-Akt signaling pathways are the two major downstream signaling cascade axes activated by EGFR (epidermal growth factor receptor) in CRC development [29]. Moreover, monoclonal EGFR-TKI resistance is currently a challenge for clinical CRC treatment [30]. All these gene-enriched pathways are seemingly associated with EGFR, a member of the ErbB family [31], which is involved in CRC pathogenesis. Meanwhile, some studies have shown that GSDMD can affect tumor development by regulating the EGFR pathway [32]. RT-qPCR (Fig. 4D) and Western blot (Fig. 4E) analysis showed that EGFR was upregulated at the mRNA and protein levels in multiple CRC cell lines. The localization of GSDMD and EGFR in CRC cell lines was evaluated by IF staining (Fig. 5A and C). The results showed that GSDMD and EGFR were mainly localized in the nucleus, and their fluorescence intensity distributions exhibited significant overlapped (Fig. 5B and D). CO-IP of Caco2 cell line and tissues from Apcmin/+ mice showed that GSDMD interacted with EGFR (Fig. 5E and F). Western blotting showed that GSDMD knockdown reduced the autophosphorylation level of EGFR at the Tyr1068 site (Fig. 5G). However, GSDMD knockdown did not affect EGFR autophosphorylation levels at Tyr1045 and Tyr1173 sites (Fig. S3F). Conversely, GSDMD overexpression promoted EGFR autophosphorylation at the Tyr1068 site (Fig. 5H) but did not affect the autophosphorylation level at the Tyr1045 and Tyr1173 sites (Fig. S3G). These findings imply that GSDMD promotes EGFR gene mutations, leading to structural changes in the Tyr1068 site of the intracellular segment of the EGFR protein, which is a ligand-independent tyrosine kinase activation.

Fig. 4.

RNA-seq reveals a downregulation of EGFR tyrosine kinase inhibitor resistance. The transcriptome datas were from HCT116 shNC and HCT116 shGSDMD cell lines (n = 3). A Volcano mapping of gene expression profiles. There were 42 down-regulated genes (blue) and 145 up-regulated genes (red) in the shGSDMD group compared to the shNC group (p-value < 0.05 and |log2-fold change|>1). B Heatmap of differential gene groupings. Orange color indicates relatively highly expressed genes and blue color indicates relatively low expressed genes. C Go/KEGG enrichment analysis of down-regulated signaling pathways significantly enriched for differentially expressed genes. D RT-qPCR assay to detect EGFR mRNA level. E Western blotting assay to detect EGFR protein levels. Data are presented as mean ± SEM. Differences between the two groups were analyzed using the Student’s t-test. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, ****P < 0.0001

Fig. 5.

GSDMD knockdown impaires the activation of EGF receptor signaling. A, C Representative immunofluorescence microscopic images of HCT116 (A) and Caco2 (C) cell lines, red color represents GSDMD, green color represents EGFR, blue color represents DAPI, Red-Green color merge shows the co-localization of GSDMD and EGFR. B, D The results of EGFR and GSDMD co-localization analysis in HCT116 (B) and Caco2 (D) cell lines. E, F Analysis of the presence of EGFR and GSDMD interactions in Caco2 cell line (E) and intestinal tissues of Apcmin/+ mice (F) by CO-IP assay. G, H The EGFR and pEGFR (Tyr1068) protein expression levels in HCT116 knockdown GSDMD stable cell line (G) and Caco2 overexpression GSDMD stable cell line (H) were detected by Western blotting. Data are presented as mean ± SEM. Differences between the two groups were analyzed using the Student’s t-test. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, ****P < 0.0001

Gefitinib inhibits the oncogenicity of GSDMD

We selected Gefitinib [33], an EGFR tyrosine kinase inhibitor, to investigate whether GSDMD expression modulates the activation of EGFR signaling in CRC. Caco2 HBLV and HBLV-h-gsdmd-3xflag stable cell lines were treated with Gefitinib, and their oncogenic properties were evaluated. Western blotting showed that GSDMD overexpression promoted EGFR autophosphorylation at the Tyr1068 site and increased ERK1/2 phosphorylation levels. Conversely, Gefitinib inhibited the autophosphorylation of EGFR at the Tyr1068 site and ERK1/2 phosphorylation induced by GSDMD overexpression (Fig. 6A). We performed CCK-8 assay, flow cytometry, Transwell assay and cell scratch assay to explore the impact of Gefitinib in modulating the role of GSDMD in the Caco2 cell line. The results indicated that Gefitinib significantly inhibited the cell viability (Fig. 6B), increased the proportion of cells arrested at G0/G1 (Fig. 6C), inhibited the cell migration ability (Fig. 6D) and inhibited the cell invasion ability (Fig. 6E) of Caco2 HBLV group and HBLV-h-gsdmd group in vitro. We found that after inhibition by gefitinib, comparing to the HBLV group, the HBLV-h-GSDMD group was more migratory and invasive, with the less proportion of cells stopping at the G0/G1 phase. In summary, GSDMD activated EGFR tyrosine kinase activity by promoting phosphorylation at the Tyr1068 site, which in turn promoted ERK1/2 phosphorylation in CRC cells. Notably, the exogenous addition of Gefitinib inhibited the oncogenic effect of GSDMD in CRC cells.

Fig. 6.

Gefitinib inhibits the oncogenicity of GSDMD. All results were derived Caco2 HBLV and HBLV-h-gsdmd-3xflag stable cell line which were untreated or treated with Gefitinib (5 µM). A The GSDMD, EGFR, pEGFR (Tyr1068), ERK1/2 and pERK1/2 protein levels were detected by Western blotting. B-E The cell viability (B), cell cycle changes (C), migration ability (x50 views) (D), and invasion ability (x100 views) (E) were tested by CCK-8 assay, flow cytometry analysis for cell cycle, cell scratch assay, and Transwell assay, respectively. All assays verified three times. Data are presented as mean ± SEM. Differences between the two groups were analyzed using the Student’s t-test. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, ****P < 0.0001

Discussion

GSDMD is a key effector molecule that activates pyroptosis, affecting the tumorigenesis [34], prognosis [35], and drug resistance of various tumors [36]. Several studies have shown that GSDMD is associated with CRC development, but the role and mechanism of GSDMD in CRC have remained unclear. Thus, this study established that GSDMD-FL promotes CRC progression by regulating EGFR autophosphorylation at the Tyr1068 site.

GSDMD is highly expressed in human clinical CRC tumor tissues, consistent with a previous study [37]. We constructed GSDMD knockdown and overexpression stable cell lines and rescued the GSDMD level on the GSDMD knockdown stable cell line. Functional assays demonstrated that GSDMD promotes the viability, invasion ability, and migration ability of CRC cells in vitro and in vivo. However, GSDMD exhibited this effect without the inflammatory stimulation that releases GSDMD-NT. Therefore, GSDMD-FL possibly affects the tumor development independent of GSDMD-NT-triggered pyroptosis.

Previous studies also concluded that GSDMD-FL depends on cleavage by inflammatory caspases for activating and releasing GSDMD-NT to trigger pyroptosis [38]. Inactivated GSDMD-FL is in a state of autoinhibition [1]. However, Shao’s team first proposed in 2016 that gasdermin protein could autonomously induce pyroptosis, which could also be induced by a caspases-independent cleavage [39]. Shao (2024) identified two novel types of activation mechanisms for GSDM proteins-peroxiredox regulation or paired intermolecular interaction mechanisms [40]. Meanwhile, Wu et al. also revealed another activation mechanism of GSDMD-palmitoylation modification [41]. All three mechanisms release the pore-forming activity of GSDMD-FL by non-caspase cleavage. This study established that GSDMD can interact with EGFR and regulate the autophosphorylation of EGFR at the Tyr1068 site. EGFR is a very important membrane receptor that is highly expressed in CRC and is an important target for CRC therapy [42]. Furthermore, EGFR autophosphorylation can promote CRC metastasis [43]. The EGFR intracellular segment mainly has several autophosphorylation sites, such as Tyr1068, Tyr1173, and Tyr1045 [44]. We observed that GSDMD mainly affects the Tyr1068 phosphorylation site. Activating this site mainly mediates the EGFR binding to Grb2, activating the Ras pathway, which in turn phosphorylates 1/2ERK [45]. Besides, the tyrosine kinase inhibitor Gefitinib inhibits the oncogenic properties of GSDMD in CRC. Therefore, the oncogenic properties of GSDMD in CRC development are associated with EGFR autophosphorylation at the Tyr1068 site. However, the specific GSDMD site that activates EGFR autophosphorylation remains unknown. Whether other modalities in this process do not depend on caspase cleavage to induce GSDMD-FL and produce pyroptosis also remains unknown.

We explored the role of epithelial-derived GSDMD in two CRC mouse models. We found that in the AOM/DSS and Apcmin/+ model mice, intestinal adenomas were less numerous and malignant in GsdmdΔIEC mice compared to Gsdmdflox/flox mice. However, when the AOM/DSS model was constructed in Gsdmd-deficient (Gsdmd−/−) mice, intestinal adenomas were larger and more numerous in Gsdmd−/− than in WT mice [46], differing from our findings in the AOM-DSS model mice. This difference may be because AOM/DSS is an inflammatory CRC model where GSDMD expression in immune cells affects intestinal adenoma development. Unlike GsdmdΔIEC mice, the expression of GSDMD in immune cells was knocked out in Gsdmd−/− mice. Wang et al. showed that inflammation can stimulate macrophages to enter an “hyperactivated” state, releasing specific lipid molecules through the GSDMD pore to promote the repair of tissue damage [47]. Notably, another study showed that intestinal adenomas were reduced in Gsdmd−/− mice than in Gsdmd+/− mice in the Apcmin/+ model [37], consistent with the our observation in Apcmin/+ mice. We believe this trend is because Apcmin/+ is a spontaneous CRC model in which the development of intestinal adenomas is genetically driven [25] and more responsive to the role of epithelial GSDMD. Thus, this study performed intestinal epithelial-specific knockouts of Gsdmd (GsdmdΔIEC) in two CRC animal models to investigate the role of epithelial GSDMD in CRC development. The study referenced the conditional knockout mice grouping setup from a previous study [25], using GsdmdΔIEC as the knockout and Gsdmdflox/flox as the control. In the Cre/flox system [48], knockout can only be achieved by Cre recombinase deleting both alleles. Therefore, from the experimental design rigor, it is more appropriate to add the Gsdmdflox/+;Villin-cre group. In the Cre/lox system principle knocks out only one allele in Gsdmdflox/+;Villin-cre mice, probably affecting the development of intestinal adenomas in Gsdmdflox/+;Villin-cre mice. However, whether this is indeed the case requires further investigation.

Conclusion

In conclusion, this study showed that GSDMD promotes CRC development by activating EGFR phosphorylation at the Tyr1068 site. The result provides new insights for the future development of CRC therapeutic strategies targeting GSDMD-mediated EGFR autophosphorylation. However, the specific GSDMD site that activates EGFR autophosphorylation remains unknown. Whether there are other protease-shear-independent ways in which GSDMD-FL induces cellular focal death during this process also remains unknown.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

Thanks to Dr. Kai Shan for his assistance in breeding transgenic mice.

Abbreviations

- CRC

Colorectal cancer

- GSDMD

Gasdermin D

- IEC

intestinal epithelial cell

- GsdmdΔIEC

IEC-specific knockout of Gsdmd

- AOM

Azoxymethane

- DSS

Dextran sulfate sodium

- GSDMD-NT

N terminal domain of Gasdermin D

- GSDMD-FL

Full-length GSDMD

- EGFR

Epidermal growth factor receptor

- ERK1/2

Extracellular-regulated kinase 1/2

Author contributions

Xiaoying Wang was responsible for the planning, design and implementation of the entire study. Ying Li contributed to the research methodology, experimental design, data collection, statistical analysis, manuscript writing, manuscript revision and manuscript review. Jiayao Chen participated in the study design, method selection and statistical analysis. Huijun Liang assisted in data collection and analysis. Qindan Du and Jingjie Shen participated in the revision of the paper.

Funding

This research was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation Grant 81902857(XYW).

Data availability

Data are available on reasonable request.

Declarations

Ethical approval

The patients were informed and signed a consent form, and the samples were collected with the consent of the Medical Ethics Committee of the People’s Hospital of Dezhou City, Dezhou, China, with the ethical review approval number: 20210108. The animal breeding and experiments were approved by the Ethics Committee of Laboratory Animal Center, Jiangnan University (JN.No20231115m0330301[554], JN.No20231215m0620701[610]).

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Shi J, Zhao Y, Wang K, Shi X, Wang Y, Huang H, Zhuang Y, Cai T, Wang F, Shao F. Cleavage of GSDMD by inflammatory caspases determines pyroptotic cell death. Nature. 2015;526:660–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Broz P, Pelegrín P, Shao F. The gasdermins, a protein family executing cell death and inflammation. Nat Rev Immunol. 2020;20:143–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lv T, Xiong X, Yan W, Liu M, Xu H, He Q. Targeting of GSDMD sensitizes HCC to anti-PD-1 by activating cGAS pathway and downregulating PD-L1 expression. J Immunother Cancer 2022;10(6):e004763. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 4.Liu X, Zhang Z, Ruan J, Pan Y, Magupalli VG, Wu H, Lieberman J. Inflammasome-activated gasdermin D causes pyroptosis by forming membrane pores. Nature. 2016;535:153–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Platnich JM, Chung H, Lau A, Sandall CF, Bondzi-Simpson A, Chen HM, Komada T, Trotman-Grant AC, Brandelli JR, Chun J, et al. Shiga Toxin/Lipopolysaccharide activates Caspase-4 and gasdermin D to trigger mitochondrial reactive oxygen species Upstream of the NLRP3 inflammasome. Cell Rep. 2018;25:1525–e15361527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ning H, Huang S, Lei Y, Zhi R, Yan H, Jin J, Hu Z, Guo K, Liu J, Yang J, et al. Enhancer decommissioning by MLL4 ablation elicits dsRNA-interferon signaling and GSDMD-mediated pyroptosis to potentiate anti-tumor immunity. Nat Commun. 2022;13:6578. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Aghapour sa, Torabizadeh M, Bahreiny SS, Saki N, Jalali Far MA, Yousefi-Avarvand A, et al. Investigating the dynamic interplay between cellular immunity and tumor cells in the fight against cancer: an updated comprehensive review. Iran J Blood Cancer 2024;16(2):84–101.

- 8.Aghaei M, Khademi R, Far MAJ, Bahreiny SS, Mahdizade AH, Amirrajab N. Genetic variants of dectin-1 and their antifungal immunity impact in hematologic malignancies: a comprehensive systematic review. Curr Res Transl Med. 2024;72:103460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Guan X, Liu R, Wang B, Xiong R, Cui L, Liao Y, Ruan Y, Fang L, Lu X, Yu X, et al. Inhibition of HDAC2 sensitises antitumour therapy by promoting NLRP3/GSDMD-mediated pyroptosis in colorectal cancer. Clin Transl Med. 2024;14:e1692. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chen J, Singh N, Ye X, Theune EV, Wang K. Gut microbiota-mediated activation of GSDMD ignites colorectal tumorigenesis. Cancer Gene Ther. 2024;31:1007–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Akimoto N, Ugai T, Zhong R, Hamada T, Fujiyoshi K, Giannakis M, Wu K, Cao Y, Ng K, Ogino S. Rising incidence of early-onset colorectal cancer - a call to action. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2021;18:230–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.He S, Xia C, Li H, Cao M, Yang F, Yan X, Zhang S, Teng Y, Li Q, Chen W. Cancer profiles in China and comparisons with the USA: a comprehensive analysis in the incidence, mortality, survival, staging, and attribution to risk factors. Sci China Life Sci. 2024;67:122–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Keum N, Giovannucci E. Global burden of colorectal cancer: emerging trends, risk factors and prevention strategies. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2019;16:713–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sánchez-Gundín J, Fernández-Carballido AM, Martínez-Valdivieso L, Barreda-Hernández D, Torres-Suárez AI. New trends in the Therapeutic Approach to Metastatic Colorectal Cancer. Int J Med Sci. 2018;15:659–65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jeong WJ, Ro EJ, Choi KY. Interaction between Wnt/β-catenin and RAS-ERK pathways and an anti-cancer strategy via degradations of β-catenin and RAS by targeting the Wnt/β-catenin pathway. NPJ Precis Oncol. 2018;2:5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Spano JP, Lagorce C, Atlan D, Milano G, Domont J, Benamouzig R, Attar A, Benichou J, Martin A, Morere JF, et al. Impact of EGFR expression on colorectal cancer patient prognosis and survival. Ann Oncol. 2005;16:102–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Napolitano S, Martini G, Ciardiello D, Del Tufo S, Martinelli E, Troiani T, Ciardiello F. Targeting the EGFR signalling pathway in metastatic colorectal cancer. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2024;9:664–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zhang Y, Liang S, Xiao B, Hu J, Pang Y, Liu Y, Yang J, Ao J, Wei L, Luo X. MiR-323a regulates ErbB3/EGFR and blocks gefitinib resistance acquisition in colorectal cancer. Cell Death Dis. 2022;13:256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Saki N, Haybar H, Aghaei M. Subject: motivation can be suppressed, but scientific ability cannot and should not be ignored. J Transl Med. 2023;21:520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Aghaei M, Khademi R, Bahreiny SS, Saki N. The need to establish and recognize the field of clinical laboratory science (CLS) as an essential field in advancing clinical goals. Health Sci Rep. 2024;7:e70008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tao Y, Wang L, Ye X, Qian X, Pan D, Dong X, Jiang Q, Hu P. Huang Qin decoction increases SLC6A4 expression and blocks the NFκB-mediated NLRP3/Caspase1/GSDMD pathway to disrupt colitis-associated carcinogenesis. Funct Integr Genomics. 2024;24:55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zhang J, Yu Q, Jiang D, Yu K, Yu W, Chi Z, Chen S, Li M, Yang D, Wang Z, et al. Epithelial gasdermin D shapes the host-microbial interface by driving mucus layer formation. Sci Immunol. 2022;7:eabk2092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wang X, Xie X, Ni JY, Li JY, Sun XA, Xie HY, et al. USP11 promotes renal tubular cell pyroptosis and fibrosis in UUO mice via inhibiting KLF4 ubiquitin degradation. Acta Pharmacol Sin 2024;0:1–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 24.Moser AR, Luongo C, Gould KA, McNeley MK, Shoemaker AR, Dove WF. ApcMin: a mouse model for intestinal and mammary tumorigenesis. Eur J Cancer. 1995;31a:1061–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gamez-Belmonte R, Mahapatro M, Erkert L, Gonzalez-Acera M, Naschberger E, Yu Y, Tena-Garitaonaindia M, Patankar JV, Wagner Y, Podstawa E, et al. Epithelial presenilin-1 drives colorectal tumour growth by controlling EGFR-COX2 signalling. Gut. 2023;72:1155–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Xu W, Han Q, Liang S, Li L, Sun X, Shao M, Yao X, Xu W. Modified Shenlingbaizhu decoction reduces intestinal adenoma formation in adenomatous polyposis coli multiple intestinal neoplasia mice by suppression of hypoxia-inducible factor 1α-induced CD4 + CD25 + forkhead box P3 regulatory T cells. J Tradit Chin Med. 2018;38:22–32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zhang Q, Chen C, Ma Y, Yan X, Lai N, Wang H, et al. PGAM5 interacts with and maintains BNIP3 to license cancer-associated muscle wasting. Autophagy 2024;20:2205–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 28.Zhu Y, Gu L, Lin X, Zhang J, Tang Y, Zhou X, et al. Ceramide-mediated gut dysbiosis enhances cholesterol esterification and promotes colorectal tumorigenesis in mice. JCI Insight 2022;7(3):e150607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 29.Krasinskas AM. EGFR Signaling in Colorectal Carcinoma. Patholog Res Int. 2011;2011:932932. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Venook AP, Niedzwiecki D, Lenz HJ, Innocenti F, Fruth B, Meyerhardt JA, Schrag D, Greene C, O’Neil BH, Atkins JN, et al. Effect of First-Line Chemotherapy Combined with Cetuximab or Bevacizumab on overall survival in patients with KRAS Wild-Type Advanced or metastatic colorectal Cancer: a Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA. 2017;317:2392–401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Friedlaender A, Subbiah V, Russo A, Banna GL, Malapelle U, Rolfo C, Addeo A. EGFR and HER2 exon 20 insertions in solid tumours: from biology to treatment. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2022;19:51–69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gao J, Qiu X, Xi G, Liu H, Zhang F, Lv T, Song Y. Downregulation of GSDMD attenuates tumor proliferation via the intrinsic mitochondrial apoptotic pathway and inhibition of EGFR/Akt signaling and predicts a good prognosis in non–small cell lung cancer. Oncol Rep. 2018;40:1971–84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wang Y, Wei J, Feng L, Li O, Huang L, Zhou S, Xu Y, An K, Zhang Y, Chen R, et al. Aberrant m5C hypermethylation mediates intrinsic resistance to gefitinib through NSUN2/YBX1/QSOX1 axis in EGFR-mutant non-small-cell lung cancer. Mol Cancer. 2023;22:81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wang WJ, Chen D, Jiang MZ, Xu B, Li XW, Chu Y, Zhang YJ, Mao R, Liang J, Fan DM. Downregulation of gasdermin D promotes gastric cancer proliferation by regulating cell cycle-related proteins. J Dig Dis. 2018;19:74–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Xu W, Song C, Wang X, Li Y, Bai X, Liang X, Wu J, Liu J. Downregulation of mir-155-5p enhances the anti-tumor effect of cetuximab on triple-negative breast cancer cells via inducing cell apoptosis and pyroptosis. Aging. 2021;13:228–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wang X, Li H, Li W, Xie J, Wang F, Peng X, Song Y, Tan G. The role of Caspase-1/GSDMD-mediated pyroptosis in Taxol-induced cell death and a taxol-resistant phenotype in nasopharyngeal carcinoma regulated by autophagy. Cell Biol Toxicol. 2020;36:437–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gao H, Li W, Xu S, Xu Z, Hu W, Pan L, Luo K, Xie T, Yu Y, Sun H, et al. Gasdermin D promotes development of intestinal tumors through regulating IL-1β release and gut microbiota composition. Cell Commun Signal. 2024;22:511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wang K, Sun Q, Zhong X, Zeng M, Zeng H, Shi X, Li Z, Wang Y, Zhao Q, Shao F, Ding J. Structural mechanism for GSDMD Targeting by Autoprocessed caspases in Pyroptosis. Cell. 2020;180:941–e955920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ding J, Wang K, Liu W, She Y, Sun Q, Shi J, Sun H, Wang DC, Shao F. Pore-forming activity and structural autoinhibition of the gasdermin family. Nature. 2016;535:111–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Li Y, Hou Y, Sun Q, Zeng H, Meng F, Tian X, He Q, Shao F, Ding J. Cleavage-independent activation of ancient eukaryotic gasdermins and structural mechanisms. Science. 2024;384:adm9190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Du G, Healy LB, David L, Walker C, El-Baba TJ, Lutomski CA, Goh B, Gu B, Pi X, Devant P, et al. ROS-dependent S-palmitoylation activates cleaved and intact gasdermin D. Nature. 2024;630:437–46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Liu YF, Feng ZQ, Chu TH, Yi B, Liu J, Yu H, Xue J, Wang YJ, Zhang CZ. Andrographolide sensitizes KRAS-mutant colorectal cancer cells to cetuximab by inhibiting the EGFR/AKT and PDGFRβ/AKT signaling pathways. Phytomedicine. 2024;126:155462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sun M, Jiang Z, Gu P, Guo B, Li J, Cheng S, Ba Q, Wang H. Cadmium promotes colorectal cancer metastasis through EGFR/Akt/mTOR signaling cascade and dynamics. Sci Total Environ. 2023;899:165699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Voldborg BR, Damstrup L, Spang-Thomsen M, Poulsen HS. Epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) and EGFR mutations, function and possible role in clinical trials. Ann Oncol. 1997;8:1197–206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Chen X, Xu P, Zhang H, Su X, Guo L, Zhou X, Wang J, Huang P, Zhang Q, Sun R. EGFR and ERK activation resists flavonoid quercetin-induced anticancer activities in human cervical cancer cells in vitro. Oncol Lett. 2021;22:754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Tanaka S, Orita H, Kataoka T, Miyazaki M, Saeki H, Wada R, Brock MV, Fukunaga T, Amano T, Shiroishi T. Gasdermin D represses inflammation-induced colon cancer development by regulating apoptosis. Carcinogenesis. 2023;44:341–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Chi Z, Chen S, Yang D, Cui W, Lu Y, Wang Z, Li M, Yu W, Zhang J, Jiang Y, et al. Gasdermin D-mediated metabolic crosstalk promotes tissue repair. Nature. 2024;634:1168–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Vergunst AC, Jansen LE, Hooykaas PJ. Site-specific integration of Agrobacterium T-DNA in Arabidopsis thaliana mediated by cre recombinase. Nucleic Acids Res. 1998;26:2729–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Data are available on reasonable request.