Abstract

Background

Carpal tunnel syndrome (CTS) is a prevalent cumulative strain injury associated with occupational risk factors such as vibration, repetitive and forceful wrist movements, and awkward wrist postures. This study aimed to identify Ontario workers at elevated risk for CTS and to explore sex differences in CTS risk among workers.

Methods

The Occupational Disease Surveillance System (ODSS) links accepted lost time compensation claims to health administrative databases. CTS cases were identified from physician billing (Ontario Health Insurance Plan) records and defined as at least one record for CTS surgery (fee code N290) between 2002 and 2020. A 3-year washout period and restricted follow-up period of 3 years were applied. A total of 792,769 workers were included in the analytical cohort. Cox proportional hazards models were used to estimate hazard ratios (HRs) and 95% confidence intervals (CI) for CTS by occupation and industry, adjusted for age and birth year, stratified by sex.

Results

A total of 3,224 CTS cases among females (f) and 2,992 cases among males (m) were identified in the cohort. We observed elevated risks of CTS in many occupations requiring repetitive and forceful manual work: slaughtering and meat cutting, canning, curing and packing (HRf = 2.28, 95%CI = 1.42–3.68; HRm = 1.95, 95%CI = 1.33–2.85); welding and flame cutting (HRf = 1.83, 95%CI = 1.01–3.32; HRm = 1.65, 95%CI = 1.35–2.01); motor vehicle fabricating and assembling (HRf = 2.14, 95%CI = 1.74–2.62; HRm = 2.43, 95%CI = 2.04–2.89); and packaging (HRf = 2.06, 95%CI = 1.43–2.97; HRm = 1.82, 95%CI = 1.12–2.98). Elevated risks were observed among males employed as nursing aides and orderlies (HRm = 1.72, 95%CI = 1.13–2.62), in mining (HRm = 1.57, 95%CI = 1.01–2.45), and in construction (HRm = 1.32, 95%CI = 1.19–1.47). Elevated risks were observed among females in mineral, metal, chemical processing (HRf = 1.58, 95%CI = 1.27–1.97), textile processing (HRf = 1.89, 95%CI = 1.22–2.94), wood machining (HRf = 2.84, 95%CI = 1.47–5.45), and females employed as janitors, charworkers and cleaners (HRf = 1.50, 95%CI = 1.32–1.71). Findings by industry were consistent with occupation results.

Conclusion

The risk of CTS varied by occupation, industry, and sex in this large cohort. Workers engaged in highly repetitive and forceful manual work were at elevated CTS risk, highlighting the need to further understand and reduce ergonomic hazards among identified groups. Future studies should also explore CTS risk by sex, with a focus on female workers.

Keywords: Carpal tunnel syndrome, Occupation, Worker’s compensation, Cumulative strain injury, Industry

Background

Carpal tunnel syndrome (CTS) is the most common entrapment neuropathy with a prevalence of about 4–5%. It primarily affects females and working-age populations, peaking around 50–54 years of age [1–3]. Personal risk factors include obesity, rheumatoid arthritis, wrist injury, diabetes, hypothyroidism, and pregnancy [4–6]. There is sufficient evidence that work-related factors also contribute to the risk of CTS [7–11]. Highly repetitive work was found to increase CTS risk nearly two-fold, especially when combined with high levels of force, a work cycle less than 10 s (performing repetitive tasks with the hands that last for less than 10 s), and high levels of velocity (fast acceleration of the wrist when it moves through space relative to its starting position) [8, 10–12]. Performing tasks with extreme wrist postures, whether flexed or extended, also contribute to the risk of CTS [8, 11]. Hand-arm vibration from prolonged use of handheld vibratory tools may further increase the risk of CTS [7–11]. Additionally, psychosocial factors may contribute to CTS risk [12, 13]. A systematic review that included six studies focusing on the association between work-related psychosocial factors and CTS risk, identified high distress, high work demands, and job strain as being positively associated with CTS risk [13].

The prevalence of CTS varies significantly, ranging from 0.6 to 61% among worker populations [14, 15]. These studies have found that around 50–90% of CTS cases are attributable to work, with higher attributable fractions among male workers [14, 16].

Historically, studies focusing on specific occupation groups have found elevated CTS risk among meat and fish processing [17, 18], forestry [19], and dental workers [20, 21]. A more recent case–control study from Sweden observed that blue-collar workers had a 67% higher risk of CTS compared to white-collar workers. This study also identified a dose–response relationship between the level of manual work and CTS risk, with heavy manual work associated with nearly twice the risk compared to light manual work [22]. Similar trends were observed in a prospective cohort study from Finland, which found that lower clerical workers (defined as lower-level employees with administrative and clerical occupations), as well as farmers and manual workers, were at significantly elevated risk for CTS, with an even more prominent risk among male workers [23]. A Danish cohort study also observed significantly elevated CTS risk among most clerical and manual labour workers, including those in construction, manufacturing, and processing, when compared to teachers [24].

In Canada and elsewhere, occupational studies on CTS mainly focused on specific occupation groups and were cross-sectional in design [20, 25, 26], or assessed CTS cases captured in workers’ compensation records [27–30]. A historical study on the population of the Island of Montreal identified elevated risk of CTS surgery among all manual workers, housekeepers, data processing operators, material handlers, lorry and bus drivers, and among food and beverage processing, childcare, and service workers, compared to non-manual workers [16]. This study also observed sex-differences: elevated risks among males in most occupations, except for food and beverage processing [16]. A more recent study in Manitoba by Kraut and colleagues examined the risk of CTS in the Manitoba Occupational Disease Surveillance System (MODSS), a surveillance system that is similar to the Ontario Occupational Disease Surveillance System (ODSS) used in this paper [31]. The Manitoba ODSS observed elevated CTS risk among workers in processing, product fabricating, construction occupations, and the mining industry.

Most studies evaluating occupational CTS risk applied a cross-sectional design and focused only on specific workers. This is the largest prospective cohort study to date that can assess CTS risk across many specific worker groups in the diverse labour force. Our study also captures the most severe cases of CTS requiring surgery that were not recognized in worker’s compensation claims. We aimed to identify both broad and more specific occupation and industry groups at elevated risk for severe CTS. Our large cohort also allowed for exploring potential sex-differences in CTS risks.

Methods

Study population

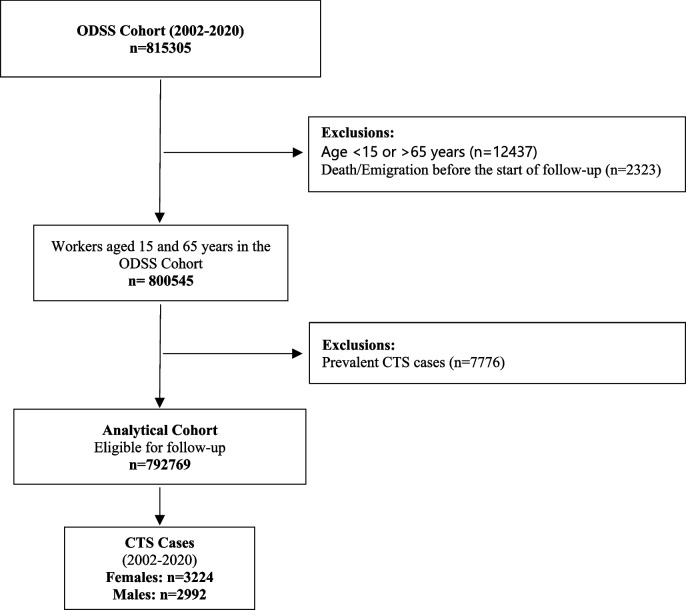

The methods of establishing the ODSS is described elsewhere in more detail [32]. Briefly, over 2 million workers were identified using the Workplace Safety and Insurance Board (WSIB) accepted lost time compensation claims records (1983–2019) and linked to the Registered Persons Database (RPDB) and health administrative databases. Accepted claims for carpal tunnel syndrome were excluded, as these were considered prevalent cases (n = 30,038). Workers were eligible for inclusion in this analysis if they had a compensation claim for an injury or diagnosis that occurred between January 1, 2002, and December 31, 2019 (n = 815,305) (Fig. 1). Workers aged less than 15 years and over 65 years were excluded, to reflect the working age population (n = 12,437). Workers who emigrated out of the province or died before the start of their follow-up were excluded (n = 2,323), leaving 800,545 workers eligible for inclusion in the study.

Fig. 1.

Identification of carpal tunnel syndrome cases in the Occupational Disease Surveillance System (ODSS) (2002–2020)

Exposure

Occupation and industry reported at the time of the WSIB accepted lost time compensation claim were coded by WSIB according to the 1971 Canadian Classification Dictionary of Occupations (CCDO) and the 1970 and 1980 Canadian Standard Industry Classification (SIC). These coding systems consist of three levels of classification with increasing specificity: division (broad), major (intermediate) and minor (specific) levels [32]. For occupation, workers were categorized into 22 division level groups, 80 groups at the major level and 483 groups at the minor level. We only reported industry results for division (n = 10) and major level industry groups (n = 49).

Case definition

CTS cases were identified in physician billing records from the Ontario Health Insurance Plan’s (OHIP) eClaims database using the International Classification of Diseases, 9th revision (ICD-9) coding system [33]. Although CTS cases could be identified as early as January 1, 1999, the earliest follow-up date of January 1, 2002 was used as this was consistent with the start of the at-risk period for CTS after applying a 3-year washout period (also known as look-back period) to identify and exclude prevalent cases (n = 7,776), similar to previous studies [22, 31]. A worker was considered a case if they had at least one billing code of ‘N290’ (decompression median nerve at wrist, indicating surgery for CTS) between 2002 and 2020 [26, 34]. This definition captures more severe and persistent cases of CTS [35]. The date of the first OHIP eClaim was recorded as the date of diagnosis.

Statistical analysis

Workers were followed from their claim date between January 1, 2002 and December 31, 2019 until the date of CTS diagnosis, death, emigration out of province, age 65 years, or end of the 3-year follow-up period, whichever occurred first. The restricted 3-year follow-up was applied to reduce the likelihood of workers changing jobs between their accepted claim and the end of follow-up [31, 36]. Cox proportional hazard models, adjusted for age at the start of follow-up and birth year, were used to calculate hazard ratios (HRs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for occupation groups at the division, major and minor levels, and industry groups at the division and major levels. The analysis was also stratified by sex to examine risk among females and males separately. In a further analysis, an interaction between sex and occupation was included in the models. For each analysis, the comparison group was all other workers in the ODSS. Case counts below six and corresponding risk estimates were not reported in accordance with agency reporting guidelines [37]. Analyses were completed using SAS V.9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, North Carolina, USA).

Sensitivity analyses

Multiple sensitivity analyses were conducted. We investigated if changing the follow-up time to 5 years would impact the findings of our study. We also explored if excluding secondary CTS cases (related to injury, malignancy, thyroid disease or diabetes) modified our results. Additionally, we examined CTS cases from hospital (Discharge Abstract Database (DAD)) and ambulatory care records (National Ambulatory Care Reporting System (NACRS)), using the International Classification of Diseases, 10th revision (ICD-10) coding system. CTS cases were identified between 2006 and 2020 based on data availability and defined as workers with 2 or more records in NACRS or at least one record in DAD with the ICD-10 diagnosis code G56.0 [38]. Due to low case counts, results could not be examined by sex.

Results

Overall, 6,216 CTS cases were identified among workers from 2002 to 2020 (Table 1). CTS cases were older at the start of follow-up and had a shorter follow-up period than non-cases. The mean age at CTS diagnosis was 47.4 years (SD: 9.2) for females and 45.6 years (SD: 10.8) for males.

Table 1.

Characteristics of carpal tunnel syndrome cases and the overall ODSS cohort, by sex (2002–2020)

| Carpal tunnel syndrome cases | ODSS overall | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Females | Males | Females | Males | |

| Total | 3224 | 2992 | 308177 | 484592 |

| Year of birth median (IQR) | 1962 (1956–1969) | 1963 (1957–1973) | 1967 (1959–1979) | 1970 (1960–1981) |

| Age at start of follow-up median (IQR) | 46 (39–52) | 44 (35–51) | 42 (31–51) | 38 (27–48) |

| Age at end of follow-up median (IQR) | 49 (41–54) | 47 (38–54) | 46 (35–55) | 42 (31–52) |

| Years of follow-up median (IQR) | 1 (1–3) | 1 (0–3) | 3 (3–3) | 3 (3–3) |

Abbreviations: IQR Interquartile Range, ODSS Occupational Disease Surveillance System

Occupation

Elevated risks were observed among both female and male workers in various occupations. At the division level, both males and females were at elevated risk in food, wood and textile processing; machining and related; and product fabricating, assembling and repairing (Table 2). In food, wood and textile processing, significantly elevated risks were observed in the food and beverage and related processing, and other processing major level groups, and in the slaughtering and meat cutting, canning, curing and packing; and labouring and other elemental work minor level occupations (Table 3). In the machining and related occupation group, elevated risks were observed among both males and females in metal shaping and forming, which was driven by workers in the welding and flame cutting minor level occupation group. In product fabricating, assembling and repairing, we found elevated risks among both sexes in the metal product fabricating major level group, which was driven by motor vehicle fabricating at the minor level. Both female and male workers had an elevated risk of CTS in the packaging minor level group. There were also reduced risks among both sexes in social sciences and protective services, driven by those working as guards and watchmen.

Table 2.

Risk of carpal tunnel syndrome by division and major-level occupation groups, stratified by sex (2002–2020)

| Females | Males | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Occupation Group | Cases | HR (95% CI)a | Cases | HR (95% CI)a |

| Managers and administration | 77 | 0.71 (0.57–0.90) | 37 | 0.81 (0.58–1.12) |

| Natural sciences, engineering, mathematics | 24 | 0.96 (0.64–1.43) | 38 | 0.90 (0.65–1.24) |

| Social sciences and related | 88 | 0.75 (0.60–0.92) | 6 | 0.36 (0.16–0.79) |

| Teaching and related | 145 | 0.61 (0.52–0.73) | 19 | 0.74 (0.47–1.16) |

| Medicine and health | 456 | 0.88 (0.79–0.97) | 55 | 1.37 (1.05–1.79) |

| Nursing therapy | 412 | 0.90 (0.81–1.00) | 45 | 1.32 (0.98–1.78) |

| Other medicine and health | 73 | 0.96 (0.76–1.21) | 10 | 1.45 (0.78–2.70) |

| Artistic, literacy, and recreational | 25 | 0.85 (0.57–1.26) | 12 | 0.61 (0.34–1.07) |

| Clerical and related | 340 | 0.94 (0.84–1.06) | 157 | 0.91 (0.77–1.07) |

| Stenographic and typing | 33 | 1.26 (0.89–1.78) | 0 | – |

| Bookkeepers, tellers, cashiers, and other clerks | 103 | 1.03 (0.84–1.25) | 11 | 1.23 (0.68–2.22) |

| Material recording scheduling and distributing | 43 | 0.92 (0.68–1.24) | 100 | 1.05 (0.86–1.28) |

| Reception, information, mail and message distribution | 69 | 1.06 (0.83–1.35) | 26 | 0.57 (0.39–0.84) |

| Other clerical | 106 | 0.83 (0.68–1.01) | 27 | 1.01 (0.69–1.48) |

| Sales | 306 | 0.96 (0.85–1.08) | 101 | 0.72 (0.59–0.87) |

| Commodities | 293 | 0.98 (0.87–1.10) | 90 | 0.68 (0.55–0.83) |

| Other sales | 13 | 0.60 (0.35–1.04) | 12 | 1.33 (0.75–2.34) |

| Services | 690 | 1.09 (1.00–1.19) | 298 | 0.92 (0.81–1.03) |

| Protective services | 28 | 0.62 (0.42–0.89) | 61 | 0.69 (0.53–0.89) |

| Other service | 278 | 1.45 (1.28–1.64) | 171 | 1.10 (0.94–1.29) |

| Farming, horticulture, and animal husbandry | 38 | 1.12 (0.81–1.54) | 65 | 1.01 (0.79–1.30) |

| Forestry and logging | < 6 | – | 6 | 0.61 (0.27–1.36) |

| Mining and quarrying | < 6 | – | 20 | 1.57 (1.01–2.45) |

| Processing (mineral, metal, chemical) | 82 | 1.58 (1.27–1.97) | 111 | 1.12 (0.93–1.36) |

| Metal processing | 15 | 2.22 (1.33–3.68) | 49 | 1.18 (0.89–1.57) |

| Chemicals petroleum rubber plastic | 68 | 1.54 (1.21–1.96) | 56 | 1.12 (0.86–1.46) |

| Processing (food, wood, textile) | 194 | 1.91 (1.65–2.21) | 141 | 1.39 (1.17–1.65) |

| Food and beverage and related processing | 155 | 1.87 (1.59–2.20) | 85 | 1.28 (1.03–1.60) |

| Wood processing, except paper pulp | < 6 | – | 14 | 1.70 (1.00–2.87) |

| Pulp and papermaking | < 6 | – | 14 | 2.27 (1.34–3.84) |

| Textile processing | 20 | 1.89 (1.22–2.94) | 8 | 1.04 (0.52–2.09) |

| Other processing | 12 | 1.78 (1.01–3.13) | 26 | 1.53 (1.04–2.25) |

| Machining and related | 95 | 1.77 (1.44–2.17) | 287 | 1.21 (1.06–1.37) |

| Metal machining | 10 | 1.27 (0.68–2.36) | 52 | 0.88 (0.67–1.16) |

| Metal shaping and forming except machining | 72 | 1.72 (1.36–2.17) | 226 | 1.32 (1.15–1.52) |

| Wood machining | 9 | 2.84 (1.47–5.45) | 14 | 1.05 (0.62–1.78) |

| Other machining | 7 | 2.09 (0.99–4.39) | 14 | 0.96 (0.57–1.62) |

| Product fabricating, assembling, and repairing | 255 | 1.67 (1.47–1.90) | 530 | 1.49 (1.35–1.64) |

| Metal products | 109 | 1.97 (1.62–2.38) | 162 | 1.95 (1.66–2.29) |

| Mechanics and repairers except electrical | 12 | 1.31 (0.74–2.31) | 225 | 1.35 (1.17–1.55) |

| Other product fabricating assembling and repairing | 69 | 1.52 (1.19–1.93) | 86 | 1.16 (0.94–1.44) |

| Construction trades | 16 | 1.01 (0.62–1.66) | 425 | 1.32 (1.19–1.47) |

| Excavating grading paving | < 6 | – | 40 | 1.19 (0.87–1.62) |

| Other construction trades | 9 | 0.82 (0.43–1.58) | 341 | 1.38 (1.23–1.55) |

| Transport and equipment operating | 76 | 1.15 (0.92–1.45) | 314 | 1.00 (0.88–1.12) |

| Air transport operating | < 6 | – | 6 | 0.36 (0.16–0.81) |

| Motor transport operating | 30 | 1.03 (0.72–1.47) | 270 | 1.07 (0.94–1.22) |

| Other transport equipment operating | 47 | 1.40 (1.05–1.87) | 47 | 0.94 (0.71–1.26) |

| Materials handling and related | 102 | 1.26 (1.03–1.54) | 193 | 1.01 (0.87–1.17) |

| Other crafts and equipment operating | 14 | 0.95 (0.56–1.61) | 27 | 0.84 (0.58–1.24) |

Division level occupations are bolded, major level occupations are indented

Statistically significant (α = 0.05) increased risks are bolded, and statistically significant decreased risks are italicized

Abbreviations: HR hazard ratio, CI confidence interval

aA 3-year washout and a 3-year follow-up period were applied, with adjustments for birth year and age at start of follow-up

Table 3.

Risk of carpal tunnel syndrome by minor-level occupation groups, stratified by sex (2002–2020)

| Females | Males | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Occupation Group | Cases | HR (95% CI)a | Cases | HR (95% CI)a |

| Managers and administration | ||||

| Officials and administrators unique to government, n.e.c | 8 | 0.55 (0.28–1.11) | < 6 | – |

| Other managers and administrators | 9 | 0.82 (0.43–1.58) | 9 | 0.91 (0.47–1.76) |

| Accountants, auditors and other financial officers | 7 | 0.91 (0.43–1.90) | < 6 | – |

| Inspectors and regulatory officers, non-government | 9 | 1.36 (0.70–2.61) | 11 | 1.65 (0.91–2.98) |

| Occupations related to management and administration, n.e.c | 24 | 0.77 (0.52–1.16) | < 6 | – |

| Natural sciences, engineering, mathematics | ||||

| Architectural and engineering technologists and technicians | 12 | 1.16 (0.66–2.05) | 20 | 0.95 (0.61–1.48) |

| Social sciences and related | ||||

| Social workers | 22 | 1.11 (0.73–1.69) | < 6 | – |

| Welfare and community services | 51 | 0.74 (0.56–0.97) | < 6 | – |

| Social sciences and related fields, n.e.c | 12 | 0.72 (0.41–1.27) | < 6 | – |

| Teaching and related | ||||

| University teaching and related, n.e.c | 8 | 0.73 (0.36–1.45) | < 6 | – |

| Elementary and kindergarten teachers | 55 | 0.52 (0.40–0.68) | 8 | 0.80 (0.40–1.60) |

| Secondary school teachers | 14 | 0.49 (0.29–0.83) | < 6 | – |

| Elementary and secondary school teaching and related, n.e.c | 73 | 0.79 (0.62–1.00) | < 6 | – |

| Medicine and health | ||||

| Nurses, registered, graduate and nurses-in-training | 125 | 0.83 (0.69–0.99) | 6 | 1.14 (0.51–2.54) |

| Nursing assistants | 60 | 0.95 (0.73–1.22) | < 6 | – |

| Nursing aides and orderlies | 222 | 1.01 (0.88–1.16) | 22 | 1.72 (1.13–2.62) |

| Nursing, therapy and related assisting | 51 | 1.02 (0.77–1.35) | 16 | 1.04 (0.64–1.71) |

| Dietitians and nutritionists | 7 | 1.82 (0.87–3.83) | 0 | – |

| Medical laboratory technologists and technicians | 43 | 0.82 (0.61–1.11) | 7 | 1.79 (0.85–3.76) |

| Other medicine and health, n.e.c | 17 | 1.41 (0.87–2.27) | < 6 | – |

| Artistic, literacy, and recreational | ||||

| Attendants, sport and recreation | 12 | 1.10 (0.63–1.95) | 8 | 1.01 (0.50–2.02) |

| Clerical and related | ||||

| Secretaries and stenographers | 26 | 1.14 (0.77–1.67) | 0 | – |

| Typists and clerk-typists | 7 | 1.93 (0.92–4.04) | 0 | – |

| Bookkeepers and accounting clerks | 7 | 0.90 (0.43–1.88) | 0 | – |

| Tellers and cashiers | 80 | 1.11 (0.89–1.38) | 7 | 1.59 (0.76–3.34) |

| Bookkeeping, account-recording, n.e.c | 13 | 0.96 (0.56–1.66) | 0 | – |

| Production clerks | 7 | 1.28 (0.61–2.69) | 6 | 1.23 (0.55–2.73) |

| Shipping and receiving clerks | 17 | 0.78 (0.48–1.25) | 63 | 0.98 (0.76–1.25) |

| Stock clerks and related | 17 | 1.11 (0.69–1.79) | 31 | 1.44 (1.01–2.05) |

| Receptionists and information clerks | 14 | 1.02 (0.60–1.73) | 0 | – |

| Mail carriers | 24 | 0.96 (0.64–1.43) | 12 | 0.53 (0.30–0.94) |

| Mail and postal clerks | 24 | 1.07 (0.72–1.60) | 7 | 0.57 (0.27–1.19) |

| Messengers | 9 | 1.48 (0.77–2.84) | 12 | 0.86 (0.49–1.51) |

| General office clerks | 42 | 0.98 (0.73–1.34) | < 6 | – |

| Other clerical and related, n.e.c | 60 | 0.90 (0.70–1.16) | 16 | 0.90 (0.55–1.47) |

| Sales | ||||

| Supervisors: sales, commodities | 61 | 0.96 (0.74–1.24) | 19 | 0.79 (0.50–1.24) |

| Salesmen and salespersons, commodities, n.e.c | 224 | 0.97 (0.85–1.11) | 52 | 0.52 (0.39–0.68) |

| Sales clerks, commodities | 17 | 0.96 (0.60–1.55) | 19 | 1.81 (1.15–2.84) |

| Driver-salesmen | 0 | – | 8 | 3.28 (1.64–6.57) |

| Other sales, n.e.c | 10 | 1.17 (0.63–2.18) | < 6 | – |

| Services | ||||

| Fire-fighting | < 6 | – | 22 | 1.00 (0.66–1.53) |

| Policemen and detectives, government | 12 | 0.80 (0.45–1.40) | 21 | 0.64 (0.42–0.99) |

| Guards and watchmen | 16 | 0.59 (0.36–0.96) | 17 | 0.50 (0.31–0.80) |

| Supervisors: food and beverage preparation and related | 31 | 1.16 (0.81–1.65) | 6 | 0.92 (0.41–2.05) |

| Chefs and cooks | 70 | 1.25 (0.99–1.58) | 46 | 1.27 (0.94–1.70) |

| Waiters, hostesses and stewards | 51 | 0.82 (0.62–1.09) | < 6 | – |

| Food and beverage preparation and related service, n.e.c | 128 | 1.14 (0.95–1.36) | 14 | 0.56 (0.33–0.95) |

| Personal service, n.e.c | 154 | 0.98 (0.83–1.15) | < 6 | – |

| Laundering and dry cleaning | 22 | 1.27 (0.83–1.93) | < 6 | – |

| Supervisors: other service | 8 | 0.86 (0.43–1.71) | 19 | 1.84 (1.17–2.88) |

| Janitors, charworkers and cleaners | 256 | 1.50 (1.32–1.71) | 140 | 1.10 (0.93–1.31) |

| Labouring and other elemental work, services | 24 | 1.55 (1.04–2.32) | 18 | 0.94 (0.59–1.49) |

| Other service, n.e.c | < 6 | – | 7 | 0.90 (0.43–1.88) |

| Farming, horticulture, and animal husbandry | ||||

| Foremen | < 6 | – | 8 | 1.66 (0.83–3.33) |

| Farm workers | 19 | 1.52 (0.97–2.39) | 24 | 1.00 (0.67–1.50) |

| Nursery and related workers | 10 | 0.74 (0.40–1.38) | 31 | 0.91 (0.64–1.30) |

| Other farming, horticultural and animal husbandry, n.e.c | 6 | 0.98 (0.44–2.18) | < 6 | – |

| Mining and quarrying | ||||

| Cutting, handling and loading | 0 | – | 6 | 1.88 (0.85–4.19) |

| Mining and quarrying, n.e.c | < 6 | – | 13 | 1.76 (1.02–3.03) |

| Processing (mineral, metal, chemical) | ||||

| Foremen, metal processing and related | < 6 | – | 6 | 2.77 (1.24–6.15) |

| Moulding, coremaking and metal casting | < 6 | – | 15 | 1.52 (0.92–2.53) |

| Metal processing and related, n.e.c | 12 | 3.08 (1.75–5.43) | 25 | 1.06 (0.71–1.57) |

| Forming: clay, glass and stone | 0 | – | 6 | 1.16 (0.52–2.59) |

| Labouring and other elemental work, chemicals, petroleum, rubber, plastic and related materials processing | 15 | 1.25 (0.75–2.08) | 15 | 1.21 (0.73–2.02) |

| Chemicals petroleum rubber plastic and related, n.e.c | 55 | 1.67 (1.28–2.19) | 37 | 1.03 (0.75–1.43) |

| Processing (food, wood, textile) | ||||

| Baking, confectionery making and related | 33 | 2.05 (1.46–2.89) | < 6 | – |

| Slaughtering and meat cutting, canning, curing and packing | 17 | 2.28 (1.42–3.68) | 27 | 1.95 (1.33–2.85) |

| Fish canning, curing, packing | 6 | 3.93 (1.77–8.76) | < 6 | – |

| Labouring and other elemental work, food, beverage and related | 88 | 1.88 (1.52–2.32) | 45 | 1.42 (1.05–1.90) |

| Food, beverage and related processing, n.e.c | 13 | 0.97 (0.56–1.67) | 11 | 0.78 (0.43–1.41) |

| Sawmill sawyers and related | 0 | – | 6 | 1.90 (0.85–4.24) |

| Textile weaving | 6 | 2.39 (1.07–5.33) | < 6 | – |

| Labouring and other elemental work, textile processing | 10 | 2.00 (1.08–3.72) | < 6 | – |

| Labouring and other elemental work, other processing | 10 | 1.57 (0.84–2.92) | 26 | 1.57 (1.07–2.31) |

| Machining and related | ||||

| Tool and die making | < 6 | – | 10 | 0.69 (0.37–1.29) |

| Machinist and machine tool setting-up | 6 | 1.75 (0.79–3.91) | 30 | 0.97 (0.68–1.40) |

| Machine tool operating | < 6 | – | 15 | 0.89 (0.54–1.48) |

| Forging | 0 | – | 6 | 1.28 (0.57–2.85) |

| Sheet metal workers | < 6 | – | 15 | 1.12 (0.67–1.86) |

| Metalworking-machine operators, n.e.c | 51 | 1.86 (1.41–2.45) | 80 | 1.10 (0.88–1.37) |

| Welding and flame cutting | 11 | 1.83 (1.01–3.32) | 104 | 1.65 (1.35–2.01) |

| Boilermakers, platers and structural metal workers | < 6 | – | 7 | 0.72 (0.34–1.50) |

| Metal shaping and forming, n.e.c | 7 | 0.93 (0.44–1.96) | 40 | 1.48 (1.08–2.02) |

| Planing, turning, shaping and related | 9 | 3.30 (1.71–6.34) | 11 | 1.01 (0.56–1.83) |

| Filing, grinding, buffing, cleaning and polishing, n.e.c | < 6 | – | 7 | 1.01 (0.48–2.13) |

| Product fabricating, assembling, and repairing | ||||

| Motor vehicle fabricating and assembling, n.e.c | 95 | 2.14 (1.74–2.62) | 136 | 2.43 (2.04–2.89) |

| Industrial, farm, construction and other mechanized equipment and machinery | 8 | 1.57 (0.78–3.14) | 15 | 1.36 (0.82–2.26) |

| Labouring and other elemental work –metal products | < 6 | – | 7 | 2.27 (1.08–4.76) |

| Other fabricating and assembling, metal products, n.e.c | < 6 | – | 10 | 0.92 (0.50–1.72) |

| Foremen: electrical, electronic equipment fabricating, assembling, installing and repairing | < 6 | – | 8 | 1.58 (0.79–3.16) |

| Electrical equipment fabricating and assembling | 19 | 1.54 (0.98–2.42) | 18 | 1.25 (0.79–1.99) |

| Electrical equipment installing and repairing, n.e.c | < 6 | – | 27 | 1.39 (0.95–2.03) |

| Electronic equipment installing and repairing, n.e.c | 17 | 1.69 (1.05–2.73) | 11 | 0.76 (0.42–1.37) |

| Cabinet and wood furniture makers | < 6 | – | 15 | 0.92 (0.56–1.54) |

| Labouring and other elemental work: wood products | < 6 | – | 9 | 1.94 (1.01–3.73) |

| Fabricating, assembling and repairing, wood products, n.e.c | < 6 | – | 16 | 1.43 (0.87–2.34) |

| Sewing machine operators, textile and similar materials | 22 | 1.28 (0.84–1.96) | < 6 | – |

| Motor vehicle mechanics and repairmen | < 6 | – | 132 | 1.43 (1.20–1.70) |

| Aircraft mechanics and repairmen | 0 | – | 7 | 1.19 (0.57–2.50) |

| Industrial, farm and construction machinery | < 6 | – | 78 | 1.13 (0.90–1.42) |

| Mechanics and repairmen, except electrical, n.e.c | < 6 | – | 28 | 1.73 (1.19–2.51) |

| Foremen: product fabricating, assembling and repairing, n.e.c | < 6 | – | 6 | 1.65 (0.74–3.67) |

| Paper product fabricating and assembling | 8 | 2.34 (1.17–4.68) | 6 | 0.81 (0.36–1.81) |

| Painting and decorating, except construction | 6 | 1.41 (0.63–3.14) | 17 | 1.05 (0.65–1.69) |

| Other product fabricating, assembling and repairing, n.e.c | 54 | 1.49 (1.13–1.95) | 54 | 1.17 (0.89–1.54) |

| Construction trades | ||||

| Foremen: excavating, grading, paving | 0 | – | 10 | 2.31 (1.24–4.30) |

| Excavating, grading | < 6 | – | 28 | 1.22 (0.84–1.77) |

| Construction electricians and repairmen | < 6 | – | 32 | 1.08 (0.76–1.54) |

| Wire communications equipment installing and repairing | < 6 | – | 16 | 1.00 (0.61–1.63) |

| Electrical power, lighting and wire communications equipment erecting, installing and repairing, n.e.c | 0 | – | 6 | 0.98 (0.44–2.19) |

| Foremen: other construction trades | 0 | – | 20 | 1.51 (0.97–2.35) |

| Carpenters | < 6 | – | 66 | 1.53 (1.19–1.95) |

| Brick and stone masons and tile setters | 0 | – | 11 | 1.02 (0.56–1.84) |

| Concrete finishing | 0 | – | 7 | 1.59 (0.76–3.33) |

| Plasterers | 0 | – | 12 | 1.16 (0.66–2.04) |

| Painters, paperhangers | < 6 | – | 12 | 1.08 (0.61–1.90) |

| Roofing, waterproofing | 0 | – | 15 | 1.46 (0.88–2.43) |

| Pipefitting, plumbing | < 6 | – | 39 | 1.44 (1.05–1.98) |

| Structural metal erectors | 0 | – | 9 | 1.82 (0.94–3.49) |

| Glaziers | 0 | – | 6 | 1.25 (0.56–2.78) |

| Labouring and other elemental work, other construction trades | 0 | – | 30 | 1.29 (0.90–1.85) |

| Other construction trades, n.e.c | 6 | 1.22 (0.55–2.73) | 167 | 1.44 (1.23–1.68) |

| Transport and equipment operating | ||||

| Air transport operating, n.e.c | < 6 | – | 6 | 0.43 (0.19–0.96) |

| Taxi drivers and chauffeurs | < 6 | – | 6 | 1.26 (0.56–2.80) |

| Truck drivers | 19 | 1.04 (0.66–1.64) | 245 | 1.15 (1.00–1.31) |

| Motor transport operating, n.e.c | < 6 | – | 46 | 1.02 (0.76–1.37) |

| Other transport and related equipment operating, n.e.c | 47 | 1.40 (1.05–1.87) | 47 | 0.95 (0.71–1.27) |

| Materials handling and related | ||||

| Hoisting occupations, n.e.c | 0 | – | 11 | 1.49 (0.83–2.70) |

| Longshoremen, stevedores and freight handlers | < 6 | – | 34 | 1.15 (0.82–1.61) |

| Materials handling equipment operators, n.e.c | < 6 | – | 12 | 1.01 (0.57–1.79) |

| Packaging occupations, n.e.c | 29 | 2.06 (1.43–2.97) | 16 | 1.82 (1.12–2.98) |

| Labouring and other elemental work, materials handling | 69 | 1.08 (0.85–1.37) | 133 | 0.93 (0.78–1.11) |

| Materials handling and related, n.e.c | < 6 | – | 11 | 1.13 (0.62–2.05) |

| Other crafts and equipment operating | ||||

| Printing press | < 6 | – | 12 | 1.24 (0.71–2.19) |

| Bookbinders and related | 7 | 1.83 (0.87–3.84) | 0 | – |

| Stationary engine and utilities equipment operating, n.e.c | < 6 | – | 8 | 0.73 (0.37–1.47) |

Division level occupations are bolded, minor level occupations are indented

Statistically significant (α = 0.05) increased risks are bolded, and statistically significant decreased risks are italicized

Abbreviations: HR hazard ratio, CI confidence interval, n.e.c. not elsewhere classified

aA 3-year washout and a 3-year follow-up period were applied, with adjustments for birth year and age at start of follow-up

There were some findings where only females demonstrated an elevated risk of CTS. Females in the mineral, metal and chemical processing division level occupation group were at elevated CTS risk, driven by those in the metal processing; and chemicals, petroleum, rubber and plastic processing major level occupation groups. Additionally, females had an elevated risk in textile processing at the major level, and related minor level occupations (textile weaving; labouring, and other elemental work in textile processing) and in the other services major group, driven by minor level occupation groups such as janitors, charworkers and cleaners; and labouring and other elemental work in services. We also observed elevated risk among females in various minor level occupations, such as baking and confectionery making; fish canning, curing, packing; and metalworking-machine operators. There were various minor level occupational groups where females were at elevated risk, while males were at a non-significantly reduced risk (e.g., electronic and related equipment installing and repairing; paper product fabricating and assembling). Reduced risks were also only observed among female workers in teaching and medicine and health at the division level, and related minor level groups: elementary and kindergarten teachers; secondary school teachers; elementary and secondary school teaching and related, n.e.c. (not elsewhere classified); and among nurses (registered, graduate and nurses-in-training).

There were also some occupational groups where only males had an elevated risk of CTS. Males had elevated risks at various occupational levels in mining and quarrying, and construction occupations (foremen in excavating, grading and paving; carpenters and related). Also, only males had an elevated risk in some minor level groups, such as labouring and other elemental work in wood product fabricating and assembling; among motor vehicle mechanics and repairmen; and mechanics and repairmen, except electrical. We observed too few cases among females to assess risks in these groups. Only males, but not females were at elevated risk in various minor level occupations, such as labouring and other elemental work in other processing; metal shaping and forming n.e.c., and among truck drivers. Also, some occupational groups at the major and minor levels demonstrated elevated risk of CTS among males, where there was no elevated risk at the division level, such as those employed as stock clerks, sales clerks in commodities, drives-salesmen, and foremen in metal processing and related.

Sex-differences analysis

When examining the interaction between sex and occupation, we found statistically significant differences in risks between females and males in medicine and health (nursing therapy and related) sales (commodities and other sales), services (other service), processing (metal processing, and food and beverage and related processing); and machining (wood machining) (Table 4). There were only a few groups where significant differences occurred, and both males and females were at elevated risk: food, wood and textile processing (also in the food and beverage and related processing at the major level); and machining and related occupations. The risk estimates were higher among females, compared to males in most of these groups, except in medicine and health, where CTS risk was significantly reduced among females, while significantly elevated among males, compared to other workers in the ODSS. However, due to low case counts among females, sex-differences could not be assessed in strongly male dominated occupations, such as mining and quarrying and construction.

Table 4.

Risk of carpal tunnel syndrome by division and major level occupation and sex, with an occupation-sex interaction (2002–2020)

| Females | Males | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Occupation Group | Cases | HR (95% CI)a | Cases | HR (95% CI)a | p-valueb |

| Managers and administration | 77 | 0.71 (0.56–0.89) | 37 | 0.85 (0.62–1.18) | 0.3524 |

| Officials and administrators unique to government | 9 | 0.50 (0.26–0.96) | < 6 | – | – |

| Other managers and administrators | 26 | 0.65 (0.44–0.96) | 21 | 0.85 (0.56–1.31) | 0.3624 |

| Management and administration | 42 | 0.81 (0.60–1.10) | 15 | 1.13 (0.68–1.87) | 0.2762 |

| Natural sciences, engineering, mathematics | 24 | 0.96 (0.64–1.43) | 38 | 0.92 (0.67–1.27) | 0.8734 |

| Architects and engineers | < 6 | – | 6 | 0.84 (0.38–1.88) | – |

| Architecture and engineering | 14 | 1.24 (0.74–2.10) | 23 | 0.94 (0.62–1.41) | 0.4051 |

| Other mathematics statistics systems analysis and related fields | 6 | 0.96 (0.43–2.13) | < 6 | – | – |

| Social sciences and related | 88 | 0.75 (0.60–0.92) | 6 | 0.37 (0.17–0.82) | 0.0915 |

| Social sciences | 6 | 1.27 (0.57–2.83) | < 6 | – | – |

| Social work and related fields | 68 | 0.80 (0.63–1.02) | < 6 | – | – |

| Library, museum and archival services | 6 | 0.73 (0.33–1.63) | < 6 | – | – |

| Other in social sciences and related | 12 | 0.58 (0.33–1.02) | < 6 | – | – |

| Teaching and related | 145 | 0.61 (0.52–0.72) | 19 | 0.77 (0.49–1.22) | 0.3393 |

| University teaching | 8 | 0.63 (0.32–1.26) | < 6 | – | – |

| Elementary and secondary school teaching | 134 | 0.61 (0.52–0.73) | 14 | 0.69 (0.41–1.17) | 0.6738 |

| Other teaching and related | 9 | 0.70 (0.36–1.35) | < 6 | – | – |

| Medicine and health | 456 | 0.87 (0.79–0.97) | 55 | 1.40 (1.07–1.83) | 0.0013 |

| Nursing therapy and related | 412 | 0.90 (0.81–1.00) | 45 | 1.34 (1.00–1.80) | 0.0123 |

| Other medicine and health | 73 | 0.96 (0.76–1.21) | 10 | 1.53 (0.82–2.84) | 0.1650 |

| Artistic, literacy, and recreational | 25 | 0.86 (0.58–1.28) | 12 | 0.62 (0.35–1.09) | 0.3411 |

| Fine and commercial art photography and related | 7 | 1.72 (0.82–3.61) | < 6 | – | – |

| Sport and recreation | 15 | 0.76 (0.46–1.26) | 8 | 0.72 (0.36–1.45) | 0.9207 |

| Clerical and Related | 340 | 0.94 (0.84–1.05) | 157 | 0.91 (0.78–1.07) | 0.7871 |

| Stenographic and typing | 33 | 1.23 (0.88–1.74) | 0 | – | – |

| Bookkeepers, tellers, cashiers, and other clerks | 103 | 1.03 (0.84–1.25) | 11 | 1.21 (0.67–2.19) | 0.6052 |

| Material recording scheduling and distributing | 43 | 0.92 (0.68–1.24) | 100 | 1.05 (0.86–1.28) | 0.4681 |

| Reception, information, mail and message distribution | 69 | 1.05 (0.83–1.34) | 26 | 0.59 (0.40–0.87) | 0.0121 |

| Other clerical and related | 106 | 0.83 (0.68–1.00) | 27 | 1.03 (0.71–1.51) | 0.3028 |

| Sales | 306 | 0.96 (0.85–1.08) | 101 | 0.71 (0.58–0.87) | 0.0105 |

| Commodities | 358 | 0.98 (0.87–1.11) | 90 | 0.67 (0.54–0.83) | 0.0022 |

| Other sales | 20 | 0.60 (0.35–1.04) | 12 | 1.34 (0.76–2.37) | 0.0450 |

| Services | 690 | 1.09 (1.00–1.19) | 298 | 0.92 (0.82–1.04) | 0.0290 |

| Protective services | 28 | 0.62 (0.43–0.91) | 61 | 0.70 (0.54–0.90) | 0.6241 |

| Food and beverage preparation and related | 259 | 1.08 (0.95–1.22) | 64 | 0.84 (0.65–1.07) | 0.0772 |

| Personal service | 161 | 0.90 (0.77–1.06) | 7 | 0.78 (0.37–1.64) | 0.7134 |

| Apparel and furnishing service | 26 | 1.29 (0.88–1.90) | < 6 | – | – |

| Other service | 278 | 1.43 (1.27–1.62) | 171 | 1.13 (0.97–1.33) | 0.0219 |

| Farming, horticulture, and animal husbandry | 38 | 1.14 (0.83–1.57) | 65 | 1.01 (0.79–1.30) | 0.5708 |

| Other farming, horticultural and animal husbandry | 37 | 1.14 (0.83–1.58) | 61 | 0.97 (0.76–1.26) | 0.4449 |

| Forestry and logging | < 6 | – | 6 | 0.61 (0.27–1.35) | – |

| Mining and quarrying | < 6 | – | 20 | 1.59 (1.02–2.46) | – |

| Processing (mineral, metal, chemical) | 82 | 1.58 (1.27–1.97) | 111 | 1.12 (0.92–1.35) | 0.0204 |

| Metal processing and related | 15 | 2.21 (1.33–3.67) | 49 | 1.18 (0.89–1.57) | 0.0345 |

| Clay glass and stone processing forming and related | 0 | – | 14 | 1.32 (0.78–2.24) | – |

| Chemicals petroleum rubber plastic and related | 68 | 1.53 (1.20–1.95) | 56 | 1.11 (0.85–1.45) | 0.0790 |

| Processing (food, wood, textile) | 194 | 1.90 (1.64–2.20) | 141 | 1.38 (1.16–1.64) | 0.0050 |

| Food and beverage and related processing | 155 | 1.87 (1.59–2.20) | 85 | 1.28 (1.03–1.60) | 0.0068 |

| Wood processing, except paper pulp | < 6 | – | 14 | 1.69 (1.00–2.86) | – |

| Pulp and papermaking and related | < 6 | – | 14 | 2.28 (1.35–3.85) | – |

| Textile processing | 20 | 1.87 (1.21–2.91) | 8 | 1.03 (0.52–2.07) | 0.1547 |

| Other processing | 12 | 1.79 (1.01–3.15) | 26 | 1.47 (1.00–2.16) | 0.5742 |

| Machining and Related | 95 | 1.76 (1.43–2.16) | 287 | 1.20 (1.06–1.36) | 0.0018 |

| Metal machining | 10 | 1.26 (0.68–2.35) | 52 | 0.88 (0.67–1.16) | 0.2989 |

| Metal shaping and forming except machining | 72 | 1.71 (1.35–2.16) | 226 | 1.31 (1.14–1.51) | 0.0558 |

| Wood machining | 9 | 2.83 (1.48–5.44) | 14 | 1.04 (0.61–1.75) | 0.0186 |

| Other machining and related | 7 | 2.08 (1.00–4.37) | 14 | 0.97 (0.58–1.65) | 0.1001 |

| Product fabricating, assembling, and repairing | 255 | 1.66 (1.46–1.89) | 530 | 1.50 (1.36–1.65) | 0.2190 |

| Metal products, n.e.c | 109 | 1.96 (1.62–2.38) | 162 | 1.95 (1.66–2.29) | 0.9626 |

| Electrical and electronic and related equipment | 36 | 1.36 (0.98–1.89) | 66 | 1.25 (0.98–1.60) | 0.6942 |

| Wood products | 8 | 1.28 (0.64–2.56) | 35 | 1.16 (0.83–1.63) | 0.8121 |

| Textile fur and leather products | 34 | 1.27 (0.91–1.79) | 10 | 1.26 (0.68–2.35) | 0.9776 |

| Rubber plastic and related | < 6 | – | 14 | 1.32 (0.78–2.23) | – |

| Mechanics and repairers except electrical | 12 | 1.31 (0.75–2.32) | 225 | 1.36 (1.18–1.56) | 0.9066 |

| Other product fabricating assembling and repairing | 69 | 1.51 (1.19–1.92) | 86 | 1.17 (0.95–1.46) | 0.1273 |

| Construction trades | 16 | 1.02 (0.62–1.67) | 425 | 1.33 (1.20–1.48) | 0.2975 |

| Excavating grading paving and related | < 6 | – | 40 | 1.22 (0.89–1.67) | – |

| Electrical power lighting and wire communications Equipment erecting installing and repairing | < 6 | – | 57 | 1.08 (0.83–1.40) | – |

| Other construction trades | 9 | 0.83 (0.43–1.60) | 341 | 1.39 (1.23–1.56) | 0.1328 |

| Transport and equipment operating | 76 | 1.15 (0.91–1.44) | 314 | 1.03 (0.91–1.16) | 0.3881 |

| Air transport operating | < 6 | – | 6 | 0.36 (0.16–0.80) | – |

| Motor transport operating | 30 | 1.02 (0.71–1.47) | 270 | 1.10 (0.97–1.25) | 0.7112 |

| Other transport and related equipment operating | 47 | 1.39 (1.04–1.86) | 47 | 0.99 (0.74–1.32) | 0.0983 |

| Materials handling and related | 121 | 1.26 (1.03–1.53) | 193 | 1.01 (0.87–1.17) | 0.0779 |

| Other crafts and equipment operating | 14 | 0.94 (0.56–1.60) | 27 | 0.86 (0.59–1.25) | 0.7713 |

| Printing and related | 12 | 0.99 (0.56–1.75) | 17 | 0.94 (0.58–1.51) | 0.8879 |

| Stationary engine and utilities equipment operating | < 6 | – | 9 | 0.75 (0.39–1.44) | – |

Division level occupations are bolded, major level occupations are indented

Statistically significant (α = 0.05) increased risks are bolded, and statistically significant decreased risks are italicized

Abbreviations: HR hazard ratio, CI confidence interval

aA 3-year washout and a 3-year follow-up period were applied, with adjustments for birth year, age at start of follow-up and an interaction between occupation and sex

bp-value for interaction term between occupation and sex

Industry

Industry results were similar to findings among occupational groups (Table 5). A higher risk was observed in manufacturing for both sexes, driven by many intermediate (major) industry groups (e.g., food and beverage, wood). An elevated risk was observed among males and females in finance, insurance and real estate, driven by those working in insurance agencies and real estate. There were also reduced risks observed in both sexes in public administration and defense, specifically among females in federal administration, and males in provincial administration. Other sex-differences were also observed among industry groups. Females in agriculture and in some manufacturing, driven by those in leather and allied, textile, furniture and fixture, paper and allied, and electrical product manufacturing, metal fabricating, and knitting mills, were at elevated risk of CTS. On the other hand, females in community, business and other utilities (specifically in education and related services) had a reduced risk. Males in mines, quarries and oil wells (specifically in metal mines); and construction industries (both general and special trade contractors) had elevated risk of CTS.

Table 5.

Risk of carpal tunnel syndrome by division and major-level industry groups, stratified by sex (2002–2020)

| Females | Males | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Industry Group | Cases | HR (95% CI)a | Cases | HR (95% CI)a |

| Agriculture | 35 | 1.42 (1.01–1.98) | 38 | 0.92 (0.67–1.27) |

| Forestry, fishing and trapping | 0 | – | 14 | 1.31 (0.77–2.21) |

| Forestry | 0 | – | 13 | 1.29 (0.75–2.23) |

| Finance, insurance, and real estate | 45 | 1.44 (1.07–1.93) | 44 | 1.53 (1.14–2.07) |

| Finance industries | < 6 | – | < 6 | – |

| Insurance agencies and real estate | 44 | 1.59 (1.18–2.14) | 39 | 1.60 (1.16–2.19) |

| Mines (including milling), quarries and oil wells | < 6 | – | 46 | 1.97 (1.47–2.64) |

| Metal mines | < 6 | – | 23 | 2.16 (1.43–3.26) |

| Quarries and sandpits | 0 | – | 11 | 1.74 (0.96–3.14) |

| Services incidental to mining | 0 | – | 9 | 1.84 (0.96–3.55) |

| Manufacturing | 604 | 1.71 (1.56–1.87) | 852 | 1.43 (1.30–1.56) |

| Food and beverage | 118 | 1.60 (1.33–1.92) | 107 | 1.26 (1.04–1.53) |

| Rubber and plastic products | 77 | 1.69 (1.35–2.12) | 59 | 1.15 (0.89–1.50) |

| Leather and allied | 12 | 2.53 (1.43–4.46) | 0 | – |

| Textile | 39 | 2.26 (1.64–3.10) | 15 | 1.15 (0.69–1.90) |

| Knitting mills | 6 | 2.26 (1.02–5.04) | 0 | – |

| Clothing industries | 9 | 0.86 (0.45–1.66) | 0 | – |

| Wood | 21 | 1.79 (1.17–2.75) | 74 | 1.39 (1.10–1.75) |

| Furniture and fixture | 25 | 1.58 (1.07–2.35) | 31 | 0.81 (0.57–1.15) |

| Paper and allied | 21 | 1.83 (1.19–2.82) | 31 | 1.23 (0.87–1.76) |

| Printing, publishing and allied | 30 | 1.26 (0.88–1.81) | 26 | 1.06 (0.72–1.55) |

| Primary metal | 13 | 2.11 (1.23–3.64) | 60 | 1.37 (1.06–1.77) |

| Metal fabricating | 75 | 1.46 (1.16–1.83) | 186 | 1.11 (0.96–1.29) |

| Machinery | < 6 | – | 13 | 1.74 (1.01–3.00) |

| Electrical product | 42 | 1.42 (1.05–1.93) | 43 | 1.35 (1.00–1.82) |

| Transportation equipment | 124 | 1.82 (1.52–2.18) | 220 | 1.80 (1.56–2.07) |

| Non-metallic products | < 6 | – | 31 | 0.98 (0.68–1.39) |

| Chemical and chemical product | 19 | 1.00 (0.64–1.58) | 33 | 1.35 (0.95–1.90) |

| Miscellaneous manufacturing | 39 | 1.34 (0.97–1.84) | 98 | 1.50 (1.23–1.84) |

| Construction | 39 | 1.17 (0.85–1.60) | 385 | 1.28 (1.15–1.43) |

| General contractors | 17 | 1.09 (0.68–1.76) | 141 | 1.35 (1.14–1.60) |

| Special trade contractors | 22 | 1.22 (0.80–1.86) | 274 | 1.24 (1.10–1.41) |

| Trade | 488 | 1.00 (0.90–1.10) | 507 | 1.03 (0.93–1.14) |

| Wholesale trade | 128 | 0.99 (0.83–1.18) | 238 | 0.96 (0.84–1.10) |

| Retail trade | 358 | 0.98 (0.87–1.09) | 294 | 1.11 (0.98–1.26) |

| Transportation, communication, and other utilities | 125 | 0.90 (0.75–1.07) | 286 | 0.91 (0.81–1.04) |

| Transportation | 66 | 0.81 (0.64–1.04) | 219 | 0.95 (0.83–1.10) |

| Communication | 43 | 0.97 (0.72–1.31) | 22 | 0.56 (0.37–0.86) |

| Electric power, gas and water utilities | 9 | 1.54 (0.80–2.96) | 37 | 1.24 (0.90–1.72) |

| Storage | 7 | 0.81 (0.39–1.71) | 17 | 0.83 (0.51–1.34) |

| Community, business, and personal service | 1251 | 0.83 (0.77–0.89) | 433 | 0.96 (0.86–1.07) |

| Education and related services | 201 | 0.68 (0.59–0.79) | 60 | 0.82 (0.63–1.06) |

| Health and welfare services | 561 | 0.91 (0.83–1.00) | 62 | 1.11 (0.86–1.43) |

| Amusement and recreation | 36 | 0.94 (0.68–1.31) | 28 | 1.08 (0.75–1.57) |

| Business management | 116 | 0.95 (0.79–1.14) | 141 | 1.00 (0.84–1.19) |

| Personal services | 30 | 1.22 (0.85–1.74) | 8 | 0.84 (0.42–1.68) |

| Accommodation and food | 286 | 1.06 (0.94–1.20) | 82 | 0.89 (0.71–1.11) |

| Miscellaneous | 96 | 1.04 (0.85–1.28) | 80 | 1.09 (0.87–1.37) |

| Public administration and defense | 228 | 0.84 (0.73–0.96) | 167 | 0.82 (0.70–0.97) |

| Federal administration | 31 | 0.62 (0.44–0.89) | 21 | 0.88 (0.57–1.35) |

| Provincial administration | 55 | 0.94 (0.72–1.22) | 26 | 0.64 (0.43–0.94) |

| Local administration | 142 | 0.87 (0.74–1.04) | 124 | 0.90 (0.75–1.08) |

| Other government offices | < 6 | – | 7 | 0.98 (0.46–2.05) |

Division level industry groups are bolded, major level occupations are indented

Statistically significant (α = 0.05) increased risks are bolded, and statistically significant decreased risks are italicized

Abbreviations: HR hazard ratio, CI confidence interval

aA 3-year washout and a 3-year follow-up period were applied, with adjustments for birth year and age at start of follow-up

Sensitivity analyses

We applied a 5-year follow-up period to compare findings to the main analysis with a 3-year follow-up (results not shown). The direction of associations remained mostly consistent. We also examined CTS cases reported in hospitalization (DAD) and emergency department visits (NACRS) in comparison to cases in the main analysis (identified through physician billing records, OHIP). The results remained somewhat consistent, however, there were fewer cases among hospitalization and emergency department visits, limiting the number of groups that could be evaluated. When we excluded secondary CTS cases, we found that the risk estimates did not change substantially.

Discussion

This study aimed to identify occupational and industry groups at elevated risk for CTS and identify sex-differences in a large Ontario cohort. Our study identified elevated risks among occupations and industries that were previously suggested in existing literature, such as construction; mining and quarrying; processing; machining and related; and product fabricating, assembling, and repairing [16, 23, 24, 31]. Our study also observed higher risks among females than among males across many occupations (e.g. food processing; janitors, charworkers and cleaners; wood machining), while higher risk among males than females was observed in other occupations (e.g. nursing aides and orderlies, stock clerks, sales clerks in commodities, metal shaping and forming, motor vehicle fabricating, construction).

Repetitive wrist movements have been associated with elevated CTS risk, especially when combined with forceful exertion. A meta-analysis that included 12 prospective cohort studies concluded with high certainty that performing repetitive wrist movements at work increased the risk of CTS by 87%, while performing tasks requiring force was associated with an 84% elevated CTS risk [10]. A more recent systematic review that only included prospective studies also found evidence that repetition in combination with high force may be related to CTS risk, and identified high levels of velocity to be a contributing factor [12]. We found elevated risk of CTS among workers that are likely to perform repetitive and/or forceful wrist movements, such as janitors, charworkers and cleaners; welders and flame cutters; mechanics; workers in many product fabricating occupations; and packaging [39–42]. The risk of CTS was also elevated in the manufacturing industries in our cohort. In a study by Rossignol et al. from Montreal, an elevated risk of CTS surgery was reported among food and beverage processing workers [16]. In a recent paper on CTS risk in the Manitoba ODSS, Kraut et al. also observed elevated risk among similar workers, such as butchers, meat cutters and fishmongers (retail and wholesale); industrial butchers and meat cutters, poultry preparers and related workers; welders and related machine operators; workers in manufacturing and utilities occupations; and in the manufacturing industry [31]. Battista et al. examined employment, demographic, and injury data from the Bureau of Labor Statistics in the United States and found that workers in the manufacturing industry were at elevated risk for work-related CTS, compared to clerical workers [43].

Performing tasks that require awkward wrist posture may also contribute to CTS risk. A systematic review by van Rijn et al. evaluated the association between work-related physical and psychosocial factors and CTS, and concluded that wrist posture, more specifically prolonged wrist flexion or extension may be associated with elevated CTS risk [8]. Such wrist posture might also be required with computer and mouse use. Several systematic reviews evaluated the relationship between computer/mouse use and CTS [44–46]. In a 2008 systematic review, Thomsen et al. concluded that the epidemiological evidence was insufficient to establish a relationship between CTS and computer work [44]. In a more recent meta-analysis, Mediouni et al. examined six studies and found no significant association between CTS and computer, keyboard or mouse use [45]. Additionally, a meta-analysis by Shiri et al. did not find an association between computer work and CTS in studies where office workers were compared to the general population [46]. However, in the same study, when office workers were compared to other office workers, a 34% elevated risk was identified with computer/typewriter use, a 93% elevated risk for mouse use, an 89% elevated risk for frequent computer use, an 84% higher risk for frequent mouse use and 92% elevated risk with more years of computer work [46]. In our study, no elevated risks were observed among clerical occupations where typing is prevalent, such as among secretaries and stenographers, typists and clerk-typists. However, we found that clerical workers were overrepresented in the WSIB lost time compensation claims for CTS among females. Therefore, many of the CTS cases among clerical workers had already been removed as prevalent cases, which may explain our results.

Hand-arm vibration has also been associated with elevated CTS risk in workers in several studies. A systematic review by Palmer et al. identified seven reports looking at the association between using hand-held vibratory tools and CTS and observed elevated risk with prolonged use [7]. Another meta-analysis by Nilsson et al. examining hand-arm vibration found that all four included studies observed elevated risk of CTS and overall, hand-arm vibration was found to increase CTS risk by almost threefold [47]. Our study found elevated CTS risk in workers likely exposed to vibration, such as those in mining and quarrying, slaughtering and meat cutting, canning, curing and packing; fish canning, curing, packing; foremen in excavating, grading, paving and related; and carpenters and related. In addition to vibration exposure, these workers are likely performing tasks that are highly repetitive and require force, potentially contributing to the higher risk of CTS [12, 48].

The sex-differences that were observed in our study might be attributable to several factors. A study by McDiarmid et al. suggested that sex-differences in CTS risk might be related to performing different tasks in the same occupation, resulting in exposure to different hazards [49]. Exposure to psychosocial hazards in the workplace might also be related to risk differences in females and males. A cross-sectional study by Rigouin et al. observed that high work-related psychological demand was associated with an almost two-fold increase in CTS risk among females, but not males [50]. Additionally, it is hypothesized that males are likely underdiagnosed for carpal tunnel syndrome, as they are less likely to seek medical attention for related symptoms. This could potentially underestimate the incidence of CTS among males in studies that rely on health administrative data [51].

This study focused on severe CTS cases, those requiring release surgery. We explored a broader case definition, using the ICD-9 code ‘354’ to identify cases of CTS (“Mononeuritis of upper limb and mononeuritis multiplex”). However, as very few cases were captured with this broader definition, we opted for using the more specific procedure code and only include CTS surgery cases. A study from Fnais et al. using OHIP eClaims data from 1992–2010 found that the majority of CTS surgery cases did not have a preceding CTS diagnosis (by a positive nerve conduction test result), suggesting that identifying non-surgical cases is challenging [35]. However, studies that relied on surgical CTS case-definitions observed results similar to studies with different case-ascertainment strategies [16, 26].

There are a number of limitations in this study. Information on occupation and industry was captured at only one point in time, through compensation claims records, without information on duration of employment or changing of jobs. To limit the possibility of exposure misclassification by workers changing jobs between the start of follow-up and diagnosis, we restricted follow-up to 3 years in our analysis. We also conducted a sensitivity analysis to assess the effect of restricting to a 5-year follow-up period. The more restrictive our analysis was, the stronger the association was between CTS risk and many occupation groups. As workers in the cohort were identified through accepted lost time compensation claims, high-hazard industries are overrepresented in our cohort, and our results might not be generalizable to the Ontario workforce. There is also a difference in the distribution of manual and non-manual labour occupations between males and females in the ODSS as females are overrepresented in non-manual labour groups, such as teaching, and medicine and health, while males are more likely to be in manual labour occupations. As the reference group consists of all other workers in the ODSS, it is possible that the comparison group for females consists of workers with a lower risk of CTS, while for males, the comparison group may include workers with a higher risk of CTS. This may have impacted our findings by attenuating risk estimates for males and elevating the risk estimates for females. However, it is unlikely that this could have affected our results to the extent that it would change the direction of the association.

An additional limitation of this study is that CTS cases were captured from health administrative data, that is structured primarily for administrative and billing purposes, and not for surveillance or research. This type of data might lack specificity and details about important covariates. Also, changes or differences in coding practices may cause additional gaps in health administrative data. We opted for using a procedure code that is specific to carpal tunnel syndrome, to avoid overestimating the number of cases in our cohort and increase specificity.

A further limitation is that we were unable to obtain information on non-occupational factors, such as socioeconomic, psychosocial, and lifestyle factors due to the limited availability of this information in administrative databases. These risk factors could act as confounders and potentially impact findings. However, our findings were consistent with previous studies that had the ability to adjust for these variables [22, 23].

A strength of this study is the use of a large, linked cohort that includes health administrative data and compensation claims records to capture work-related and health information in Ontario. The use of compensation claims data provide detailed and accurate employment information, often challenging to capture elsewhere. The large cohort size allows for the examination of CTS at various levels of occupation and industry, and by sex, often limited in other studies. Another strength of this study is that it reduces the potential impact of the healthy worker effect by comparing occupation and industry groups to each other, rather than the general population.

Conclusions

In this study, various occupation and industry groups were identified, and in many groups female workers had a higher risk of CTS than male workers. We observed the greatest risk among workers in mining and quarrying, processing, and machining. These workers may perform tasks that were identified as occupational risk factors for CTS in previous studies. Our results suggest that even severe occupational CTS cases in high-risk occupations may not be identified in compensation claims data (as accepted compensation claims for CTS were recognized as prevalent cases and excluded from our study). Moreover, the higher risk implies that ergonomic hazards are still prevalent among these workers. It is important to identify and reduce these hazards where possible. Further research is needed to study less severe occupational CTS to prevent the cases progressing to severe CTS that require surgery. Also, research is needed to assess the higher risks observed among female workers compared to males, and to identify how potential risk factors may affect females and males differently.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Nelson Chong for his work with conducting the data linkage for the ODSS.

Clinical trial number

Not applicable.

Abbreviations

- CCDO

Canadian Classification Dictionary of Occupations

- CI

Confidence interval

- CTS

Carpal tunnel syndrome

- DAD

Discharge Abstract Database

- HR

Hazard ratio

- ICD-9

International Classification of Diseases, 9th revision

- ICD-10

International Classification of Diseases, 10th revision

- MODSS

Manitoba Occupational Disease Surveillance System

- NACRS

National Ambulatory Care Reporting System

- n.e.c.

Not elsewhere classified

- ODSS

Occupational Disease Surveillance System

- OHIP

Ontario Health Insurance Plan

- RPDB

Registered Persons Database

- SIC

Canadian Standard Industry Classification

- WSIB

Workplace Safety and Insurance Board

Authors’ contributions

FRE, the first author, contributed to data preparation, data analysis, interpretation of the work and drafted the manuscript, figure and tables. JS contributed to the acquisition of the data, design and conceptualization of the work, interpretation of the data, and revising of the paper. PAD contributed to the acquisition of the data, provided overall support for the design of this work, interpretation of the data, and revising of the paper. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the Ontario Ministry of Labour, Immigration, Training and Skills Development (14-R-029). The Occupational Cancer Research Centre is supported by the Ontario Ministry of Labour, Immigration, Training and Skills Development, and the Ontario Health agency.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the Ontario Health agency and the Workplace Safety and Insurance Board, but restrictions apply to the availability of these data, which were used under license for the current study, and so are not publicly available. Data are however available from the authors upon reasonable request and with permission from the Ontario Health agency and the Workplace Safety and Insurance Board.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study was approved by the University of Toronto Health Sciences Research Ethics Board, Toronto, Canada (#39013). Our study was conducted in accordance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Atroshi I, Gummesson C, Johnsson R, Ornstein E, Ranstam J, Rosén I. Prevalence of carpal tunnel syndrome in a general population. JAMA. 1999;282(2):153–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chammas M, Boretto J, Burmann LM, Ramos RM, dos Neto FCS, Silva JB. Carpal tunnel syndrome – Part I (anatomy, physiology, etiology and diagnosis). Rev Bras Ortop. 2014;49(5):429–36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Treaster DE, Burr D. Gender differences in prevalence of upper extremity musculoskeletal disorders. Ergonomics. 2004;47(5):495–526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Geoghegan JM, Clark DI, Bainbridge LC, Smith C, Hubbard R. Risk factors in carpal tunnel syndrome. J Hand Surg Br. 2004;29(4):315–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Solomon DH, Katz JN, Bohn R, Mogun H, Avorn J. Nonoccupational risk factors for carpal tunnel syndrome. J Gen Intern Med. 1999;14(5):310–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Aroori S, Spence RA. Carpal tunnel syndrome. Ulster Med J. 2008;77(1):6–17. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Palmer KT, Harris EC, Coggon D. Carpal tunnel syndrome and its relation to occupation: a systematic literature review. Occup Med. 2007;57(1):57–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Van Rijn RM, Huisstede BMA, Koes BW, Burdorf A. Associations between work-related factors and the carpal tunnel syndrome–a systematic review. Scand J Work Environ Health. 2009;35(1):19–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kozak A, Schedlbauer G, Wirth T, Euler U, Westermann C, Nienhaus A. Association between work-related biomechanical risk factors and the occurrence of carpal tunnel syndrome: an overview of systematic reviews and a meta-analysis of current research. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2015;16:231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hassan A, Beumer A, Kuijer PPFM, van der Molen HF. Work-relatedness of carpal tunnel syndrome: systematic review including meta-analysis and GRADE. Health Sci Rep. 2022;5(6):e888. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health. Musculoskeletal disorders and workplace factors. A critical review of epidemiologic evidence for work-related musculoskeletal disorders of the neck, upper extremity, and low back. 1997. https://www.cdc.gov/niosh/docs/97-141/. Accessed 28 Jan 2024.

- 12.Gerger H, Macri EM, Jackson JA, Elbers RG, van Rijn R, Søgaard K, et al. Physical and psychosocial work-related exposures and the incidence of carpal tunnel syndrome: a systematic review of prospective studies. Appl Ergon. 2024;117:104211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mansfield M, Thacker M, Sandford F. Psychosocial risk factors and the association with carpal tunnel syndrome: a systematic review. Hand. 2018;13(5):501–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hagberg M, Morgenstern H, Kelsh M. Impact of occupations and job tasks on the prevalence of carpal tunnel syndrome. Scand J Work Environ Health. 1992;18(6):337–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dale AM, Harris-Adamson C, Rempel D, Gerr F, Hegmann K, Silverstein B, et al. Prevalence and incidence of carpal tunnel syndrome in US working populations: pooled analysis of six prospective studies. Scand J Work Environ Health. 2013;39(5):495–505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rossignol M, Stock S, Patry L, Armstrong B. Carpal tunnel syndrome: what is attributable to work? The Montreal study. Occup Environ Med. 1997;54(7):519–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kim JY, Kim J II, Son JE, Yun SK. Prevalence of carpal tunnel syndrome in meat and fish processing plants. J Occup Health. 2004;46(3):230–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Frost P, Andersen JH, Nielsen VK. Occurrence of carpal tunnel syndrome among slaughterhouse workers. Scand J Work Environ Health. 1998;24(4):285–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bovenzi M, Zadini A, Franzinelli A, Borgogni F. Occupational musculoskeletal disorders in the neck and upper limbs of forestry workers exposed to hand-arm vibration. Ergonomics. 1991;34(5):547–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Liss GM, Jesin E, Kusiak RA, White P. Musculoskeletal problems among Ontario dental hygienists. Am J Ind Med. 1995;28(4):521–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Anton D, Rosecrance J, Merlino L, Cook T. Prevalence of musculoskeletal symptoms and carpal tunnel syndrome among dental hygienists. Am J Ind Med. 2002;42(3):248–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Möllestam K, Englund M, Atroshi I. Association of clinically relevant carpal tunnel syndrome with type of work and level of education: a general-population study. Sci Rep. 2021;11(1):19850. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hulkkonen S, Shiri R, Auvinen J, Miettunen J, Karppinen J, Ryhänen J. Risk factors of hospitalization for carpal tunnel syndrome among the general working population. Scand J Work Environ Health. 2020;46(1):43–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tabatabaeifar S, Svendsen SW, Frost P. Carpal tunnel syndrome as sentinel for harmful hand activities at work: a nationwide Danish cohort study. J Occup Environ Med. 2020;62(5):375–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Harris ML, Sentner SM, Doucette HJ, Brillant MGS. Musculoskeletal disorders among dental hygienists in Canada. Can J Dent Hyg. 2020;54(2):61–7. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Liss GM, Armstrong C, Kusiak RA, Gailitis MM. Use of provincial health insurance plan billing data to estimate carpal tunnel syndrome morbidity and surgery rates. Am J Ind Med. 1992;22(3):395–409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Manktelow RT, Binhammer P, Tomat LR, Bril V, Szalai JP. Carpal tunnel syndrome: cross-sectional and outcome study in ontario workers. J Hand Surg Am. 2004;29(2):307–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Watts RJ, Osei-Tutu KB, Lalonde DH. Carpal tunnel syndrome and workers’ compensation: a cross-Canada comparison. Can J Plast Surg. 2003;11(4):199–202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yassi A, Sprout J, Tate R. Upper limb repetitive strain injuries in Manitoba. Am J Ind Med. 1996;30(4):461–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lippel K. Compensation for musculoskeletal disorders in Quebec: systemic discrimination against women workers? Int J Health Serv. 2003;33(2):253–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kraut A, Rydz E, Walld R, Demers PA, Peters CE. Carpal tunnel syndrome among Manitoba workers: results from the Manitoba occupational disease surveillance system. Am J Ind Med. 2024;67(3):243–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jung JKH, Feinstein SG, Palma Lazgare L, Macleod JS, Arrandale VH, McLeod CB, et al. Examining lung cancer risks across different industries and occupations in Ontario, Canada: the establishment of the Occupational Disease Surveillance System. Occup Environ Med. 2018;75(8):545–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Buck CJ. 2015 ICD-9-CM for Hospitals. Vol. Volumes 1. Elsevier Health Sciences; 2015.

- 34.Ontario Ministry of Health (2023). Schedule of benefits: physician services under the Health Insurance Act. 2023. https://www.ontario.ca/files/2024-01/moh-ohip-schedule-of-benefits-2024-01-24.pdf. Accessed 3 Apr 2024.

- 35.Fnais N, Gomes T, Mahoney J, Alissa S, Mamdani M. Temporal trend of carpal tunnel release surgery: a population-based time series analysis. PLoS One. 2014;9(5):e97499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Abbas S, Ihle P, Köster I, Schubert I. Estimation of disease incidence in claims data dependent on the length of follow-up: a methodological approach. Health Serv Res. 2012;47(2):746–55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Information and Privacy Commissioner of Ontario. De-identification Guidelines for Structured Data. 2016. https://www.ipc.on.ca/sites/default/files/legacy/2016/08/Deidentification-Guidelines-for-Structured-Data.pdf. Accessed 9 Jul 2024.

- 38.Koesterman J. Buck’s 2025 ICD-10-CM for Hospitals, 1st Edition. Elsevier; 2023.

- 39.Guo F, Liu L, Lv W. Biomechanical analysis of upper trapezius, erector spinae and brachioradialis fatigue in repetitive manual packaging tasks: Evidence from Chinese express industry workers. Int J Ind Ergon. 2020;1(80):103012. [Google Scholar]

- 40.CCOHS: Welding - Ergonomics. https://www.ccohs.ca/oshanswers/safety_haz/welding/ergonomics.html. Accessed 6 Nov 2024.

- 41.CCOHS: Mechanic. https://www.ccohs.ca/oshanswers/occup_workplace/mechanic.html. Accessed 6 Nov 2024.

- 42.Industrial Musculoskeletal Injury Reduction Program. Janitor Tool Kit. Industrial Musculoskeletal Injury Reduction Program Society. 1999. https://www.safer.ca/docs/Janitor.pdf.

- 43.Battista EB, Yedulla NR, Koolmees DS, Montgomery ZA, Ravi K, Day CS. Manufacturing workers have a higher incidence of carpal tunnel syndrome. J Occup Environ Med. 2021;63(3):E120–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Thomsen JF, Gerr F, Atroshi I. Carpal tunnel syndrome and the use of computer mouse and keyboard: a systematic review. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2008;9:134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Mediouni Z, De Roquemaurel A, Dumontier C, Becour B, Garrabe H, Roquelaure Y, et al. Is carpal tunnel syndrome related to computer exposure at work? A review and meta-analysis. J Occup Environ Med. 2014;56(2):204–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Shiri R, Falah-Hassani K. Computer use and carpal tunnel syndrome: a meta-analysis. J Neurol Sci. 2015;349(1–2):15–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Nilsson T, Wahlström J, Burström L. Hand-arm vibration and the risk of vascular and neurological diseases—A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2017;12(7):e0180795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Silverstein BA, Fine LJ, Armstrong TJ. Occupational factors and carpal tunnel syndrome. Am J Ind Med. 1987;11(3):343–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.McDiarmid M, Oliver M, Ruser J, Gucer P. Male and female rate differences in carpal tunnel syndrome injuries: personal attributes or job tasks? Environ Res. 2000;83(1):23–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Rigouin P, Ha C, Bodin J, Le Manac’H AP, Descatha A, Goldberg M, et al. Organizational and psychosocial risk factors for carpal tunnel syndrome: a cross-sectional study of French workers. Int Arch Occup Environ Health. 2014;87(2):147–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Padua L, Aprile I, Caliandro P, Tonali P, Padua L. Is the occurrence of carpal tunnel syndrome in men underestimated? Epidemiology. 2001;12(3):369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the Ontario Health agency and the Workplace Safety and Insurance Board, but restrictions apply to the availability of these data, which were used under license for the current study, and so are not publicly available. Data are however available from the authors upon reasonable request and with permission from the Ontario Health agency and the Workplace Safety and Insurance Board.