Abstract

Background and Aims

Soil endemics have long fascinated botanists owing to the insights they can provide about plant ecology and evolution. Often, these species have unique foliar nutrient composition patterns that reflect potential physiological adaptations to these harsh soil types. However, understanding global nutritional patterns to unique soil types can be complicated by the influence of recent and ancient evolutionary events. Our goal was to understand whether plant specialization to unique soils is a stronger determinant of nutrient composition of plants than climate or evolutionary constraints.

Methods

We worked on gypsum soils. We analysed whole-plant nutrient composition (leaves, stems, coarse roots and fine roots) of 36 native species of gypsophilous lineages from the Chihuahuan Desert (North America) and the Iberian Peninsula (Europe) regions, including widely distributed gypsum endemics, as specialists, and narrowly distributed endemics and non-endemics, as non-specialists. We evaluated the impact of evolutionary events and soil composition on the whole-plant composition, comparing the three categories of gypsum plants.

Key Results

Our findings reveal nutritional convergence of widely distributed gypsum endemics. These taxa displayed higher foliar sulphur and higher whole-plant magnesium than their non-endemic relatives, irrespective of geographical location or phylogenetic history. Sulphur and magnesium concentrations were mainly explained by non-phylogenetic variation among species related to gypsum specialization. Other nutrient concentrations were determined by more ancient evolutionary events. For example, Caryophyllales usually displayed high foliar calcium, whereas Poaceae did not. In contrast, plant concentrations of phosphorus were mainly explained by species-specific physiology not related to gypsum specialization or evolutionary constraints.

Conclusions

Plant specialization to a unique soil can strongly influence plant nutritional strategies, as we described for gypsophilous lineages. Taking a whole-plant perspective (all organs) within a phylogenetic framework has enabled us to gain a better understanding of plant adaptation to unique soils when studying taxa from distinct regions.

Keywords: Biogeography, ecophysiology, evolutionary ecology, gypsophile, gypsum, macroecology, mineral nutrition, soil endemics, sulphur

INTRODUCTION

Unique soil types, such as saline, limestone, serpentine and gypsum, often have nutritional imbalances for plants. The unique chemistry of these soil types has profound effects on plant ecology, limiting plant life, but also promoting plant diversification (Rajakaruna, 2018). As a result, many taxa have adapted to the chemistry of unique soils, and they exhibit particular physiological mechanisms to cope with nutritional imbalances (Lambers and Oliveira, 2019). Such is the case for serpentine soils with excess heavy metals and a low Ca:Mg ratio (Whittaker, 1954; Kazakou et al., 2008), saline soils with an excess of salts (Munns and Tester, 2008), or limestone soils with an excess of calcium (Mota et al., 2021). All these unique soils host plants exclusively adapted to them. To understand the physiological mechanisms used by plants to face these nutritional imbalances, foliar nutrient composition is generally analysed (Zhao et al., 2016). However, unique soils occur across regions and even continents, which can mask the evolutionary effect of soil chemistry on foliar composition. Driven by climatic variation and by climate seasonality, differences in mean annual precipitation and temperature among regions can determine foliar composition patterns (Sardans et al., 2016). They also can harbour completely different floras, with phylogeny influencing foliar composition patterns, although mainly at the order or family level (Neugebauer et al., 2018). However, research on plant adaptation to unique soils typically does not span regions, hence it is unclear whether their unique soil chemistry, the effects of climate or phylogeny most strongly control nutritional strategies.

Gypsum soils are among the most widespread unique substrates in the world, occurring in drylands in 112 countries worldwide (Pérez-García et al., 2017). Gypsum regions are particularly common in the Mediterranean Basin and in western and central Asia, but they are also found in eastern and southwestern Africa, Australia, and in the southwestern parts of North America (Mota et al., 2021). Research on gypsum plants has been conducted mainly in two gypsum regions: the Iberian Peninsula and the Chihuahuan Desert Region (Moore et al., 2014), which span different biomes with substantially different rainfall regimes. Gypsum soils of the Iberian Peninsula are included in the mediterranean biome, with most annual rainfall occurring during the cool winter months, whereas gypsum soils of the Chihuahuan Desert Region typically occur in a monsoonal arid desert biome, with most annual rainfall occurring in the hot summer months. Although the biomes are distinct, gypsum soils of both regions significantly alter plant nutrition (Merlo et al., 2019; Palacio et al., 2022).

The moderate solubility of gypsum (~2.4 g L−1) modifies soil characteristics, resulting in highly dynamic soil environments, with dissolution–precipitation sequences that alter physicochemical properties (Casby-Horton et al., 2015). High gypsum levels generate abnormally high ionic concentrations of Ca2+ and SO42− in the soil solution. In turn, the high Ca2+ concentration saturates the cation exchange complex, resulting in nutrient immobilization and low nutrient availability (Guerrero-Campo et al., 1999). However, these edaphic constraints do not preclude the existence of highly diverse plant communities in both regions, with species distributed in several taxonomic orders and families (Moore et al., 2014), but favour adaptive diversification. Consequently, many of the dominant species on gypsum in both the Iberian Peninsula and the Chihuahuan Desert Region are gypsum endemic species (Ochoterena et al., 2020), also known as gypsophiles (Meyer, 1986).

In response to these soil properties, gypsum endemics have unique foliar nutrient signatures, typically having a higher foliar S and Ca, lower K and, sometimes, higher foliar Mg than their cogeneric or cofamilial non-endemic taxa (Muller et al., 2017; Palacio et al., 2022). This unique foliar composition is likely to reflect physiological mechanisms related to being gypsum specialists (Palacio et al., 2007; Cera et al., 2021b). Although some gypsum endemic taxa have chemical signatures more similar to non-endemic taxa (Palacio et al., 2007, 2022; Bolukbasi et al., 2016; Muller et al., 2017), these taxa mainly exhibit a narrow geographical distribution within their gypsum region. Foliar composition and geographical distribution of gypsum endemics thus appear to be related in the Chihuahuan Desert Region and Iberian Peninsula (Escudero et al., 2015). Furthermore, this correlation is hypothesized to be related to the evolutionary history of gypsophilous lineages. Widespread gypsophilous taxa throughout a gypsum region (hereafter, wide gypsophiles) are predicted to belong to older and well-established gypsophilous lineages with specialized adaptations for living on gypsum (i.e. unique foliar composition), whereas narrowly distributed taxa in a gypsum region are predicted to belong mostly to younger gypsophilous lineages with fewer specializations to gypsum soils (Muller et al., 2017), except for a few potentially old and narrow taxa (Escudero et al., 2015).

This evolutionary perspective is important for understanding plant life in gypsum soils. Foliar composition of gypsum plants has been determined by recent and ancient evolutionary events related to adaptation to gypsum soils (Palacio et al., 2022). Plant specialization to gypsum is likely to be fairly recent and has occurred independently many times across different plant linages and in many regions, and it is probably related to certain pre-adaptive mechanisms in some lineages, with a bias towards clade membership in groups such as asterids, Caryophyllales and Brassicales (Moore et al., 2014). Gypsum specialization can be indicated by tolerance to high foliar S, Ca and Mg concentrations, whereas non-endemic taxa seem to use mechanisms that block the movement of S, Ca and Mg from roots to shoots (Cera et al., 2022). However, despite evidence of nutritional convergence among gypsum endemics from different regions and belonging to different families, these results typically stem from separate studies in the Chihuahuan Desert Region or in the Iberian Peninsula. Whether gypsum specialization is stronger in determining plant nutritional composition than climatic differences or evolutionary constraints, such as those imposed by ancient evolutionary events that might be reflected at deeper taxonomical levels (e.g. families or orders), has not been demonstrated thus far.

Consequently, the objective of this study was to describe and compare, for the first time, the nutrient accumulation patterns in different plant organs of field-collected wide gypsophiles, narrow gypsophiles and non-gypsum endemic taxa belonging to different gypsophilous lineages from distinct regions with different rainfall seasonality but similar annual precipitation. The regions studied are drylands in the Iberian Peninsula and the Chihuahuan Desert. We tested the following hypothesis: wide gypsophiles would accumulate high S, Ca and Mg concentrations in all organs, especially leaves, whereas these accumulation patterns would not be observed in confamilial non-gypsum endemic taxa and narrow gypsophiles, regardless of the region or the gypsophilous lineage. The aim of this study was to shed light on plant adaptation to gypsum soils, revealing whether there is a convergence in nutritional strategy in different gypsophilous lineages growing in different regions.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Chihuahuan Desert study sites and species selection

The Chihuahuan Desert Region includes the largest desert in North America and contains extensive gypsum exposures that harbour the largest known gypsophile flora in the world, with well over 200 species restricted to gypsum (Parsons, 1976; Moore et al., 2014; Ochoterena et al., 2020). The Chihuahuan Desert Region has an arid to semi-arid climate, characterized by a monsoonal rainfall pattern, with relatively low mean annual winter precipitation and higher mean annual summer precipitation that peaks in July–September (Supplementary Data Fig. S1). Mean annual winter temperature in the Chihuahuan Desert itself is 9.3 °C, and mean annual summer temperature is 25 °C (Munson, 2013). Gypsum exposures in the Chihuahuan Desert Region occur in a wide variety of habitat types, largely depending upon the elevation of the gypsum exposure. Those at low elevations (<1400 m) occur in desert scrub (or grassland in eastern New Mexico), those at intermediate elevations (1400–2000 m) may be in desert grasslands or piñon–juniper savanna, and those at higher elevations (>2000 m) occur in open pine woodland. Regardless of habitat type, dominant plant taxa on Chihuahuan Desert gypsum soils in the Chihuahuan Desert Region are primarily gypsophile perennial forbs concentrated in four several major plant clades: the asterids, Caryophyllales, Brassicaceae and Poaceae (Moore et al., 2014).

In the Chihuahuan Desert region, sampling focused on genera that include regionally dominant gypsophiles from the families Asteraceae (Dicranocarpus, Gaillardia and Haploësthes), Brassicaceae (Nerisyrenia), Nyctaginaceae (Abronia, Acleisanthes and Anulocaulis), Poaceae (Sporobolus and Bouteloua) and the order Boraginales (Tiquilia and Nama). Each family had representative species in each of three groups: (1) wide gypsophiles; (2) narrow gypsophiles; and (3) gypsovags. We selected congeners when available in order to detect phylogenetic patterns in the data; however, this approach was not possible for all taxonomic groups, because not all families have representative narrow gypsophiles or gypsovags. Plant and soil collections were conducted at several low-elevation sites in the northern Chihuahuan Desert Region near Carlsbad, Roswell and White Sands National Monument, New Mexico, and the Big Bend area, Texas, USA (Supplementary Data Table S1).

Iberian Peninsula study sites and species selection

The Iberian Peninsula is the region with the most extensive gypsum outcrops and the most species-rich gypsophile flora in Europe (Mota et al., 2011). Iberian gypsum ecosystems are also relatively well studied, with the greatest floristic and ecological knowledge of the gypsum flora in the world (Mota et al., 2011; Moore et al., 2014; Escudero et al., 2015). Similar to the Chihuahuan Desert Region, soils in Spain are a mosaic of calcareous and gypsum soils (Mota et al., 2011). The Iberian Peninsula has a semi-arid Mediterranean climate, with wetter, cooler winters and hotter, drier summers (Supplementary Data Fig. S1). Gypsophiles in the Iberian Peninsula are typically sub-shrubs and shrubs (Palacio et al., 2007). Sampling of the Spanish taxa was conducted in a similar fashion to the Chihuahuan Desert taxa. We selected taxa based on their ecological significance in gypsum communities, similarity in growth form and, where possible, phylogenetic relationships. We selected representative congeners and confamilials. We collected species belonging to the families Brassicaceae (Lepidium and Matthiola), Caryophyllaceae (Gypsohila and Herniaria), Cistaceae (Helianthemum) and Fabaceae (Ononis) (Supplementary Data Fig. S1). Collections took place in the regions of Almería (southeastern Spain) and Zaragoza (northeastern Spain), and all plants were collected in gypsum-dominated soils.

Field sampling design

Plant leaves, stems, coarse roots and fine roots were collected from at least five plant replicates per species. We chose isolated individuals randomly from within an area ~50 m × 50 m and ≥20 m from roadsides to minimize the effects of disturbance. Each replicate was ≥10 m away from other sampled replicates of the same species. We selected healthy adult plants with their foliage exposed to full sunlight, between winter and spring in 2016 in the Iberian Peninsula and in August 2016 in the Chihuahuan Desert Region. All plant organs were stored in silica gel for transfer to the laboratory, where they were separated using tweezers and rinsed in tap water (Iberian Peninsula species) or deionized water (Chihuahuan Desert species). Samples were dried at 50 °C to a constant weight for ≥5 days and subsequently ball milled (Retsch MM200, Restch GmbH, Germany) for Iberian Peninsula species and in a Wiley mill for Chihuahuan Desert species to a fine powder prior to elemental analyses.

To compare relative soil nutrient concentration across sites, interspace soils were collected at each Chihuahuan Desert site from the top 0–20 cm, following removal of biological soil crust and O horizons. We sampled soils from three locations per site that represented the spatial extent of the study area, with a minimum distance of 50 m between sampling locations. Each interspace soil sample represented a composite of three subsamples taken from the 0–20 cm layer. We sieved (2 mm) and weighed soils for fine soil and gravel mass. Soil samples were allowed to air dry if collected moist prior to chemical analyses. In the Iberian Peninsula, we collected five samples per site, representing the spatial extent of each plant collection site. Soil samples were air dried for ≥2 months and subsequently sieved through a 2 mm sieve prior to chemical analyses. In both cases, we used the average values per plant collection site in statistical analyses.

Soil and plant chemical analyses

Nitrogen (N) and carbon (C) concentrations were analysed with an elemental analyser (TruSpec CN, LECO, St. Joseph, MI, USA). Elemental concentrations of calcium (Ca), potassium (K), magnesium (Mg), phosphorus (P) and sulphur (S) were measured by extracting samples with HNO3–H2O2 (8:2 for plants and 9:3 for soils) by microwave acid digestion (Speed Ave MWS-3+, BERGHOF, Eningen, Germany), followed by inductively coupled plasma–optical emission spectrometry (Varian ICP 720-ES, Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA, USA). All elemental analyses were performed by EEZ-CSIC Analytical Services.

Phylogenetic tree

Phylogenetic trees for the study species were built using the R package V.PhyloMaker (Jin and Qian, 2019). If our target species were not included in the Angiosperm dated phylogeny provided by V.PhyloMaker, we selected a close relative in the V.PhyloMaker phylogeny for replacement based on the available bibliography (Supplementary Data Table S2).

Statistical analyses

To evaluate nutrient accumulation across organs in plants with contrasting affinity to gypsum, we built different phylogenetic mixed models for each studied mineral nutrient. We included soil nutrient concentration as a covariable to test its effect on plant nutrient concentration. Plant mineral nutrient concentrations were always included as a response variable with a Gaussian distribution. All models accounted for species-level phylogenetic relationships using phylogeny as a random effect. In addition, we accounted for multiple measurements in each species by including species identity as a random effect. All phylogenetic mixed models were fitted with Bayesian Markov chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) techniques implemented in the ‘MCMCglmm’ package in R (Hadfield, 2023). In all phylogenetic mixed models, the MCMC chain ran for 150 000 iterations, with a burn-in period of 1000 iterations. The following priors were used in accordance with Verdú et al. (2011) for the G-structure and R-structure, respectively (variance matrix = 1, degree of believe parameter = 0.02).

To identify differences between wide gypsophiles, gypsovags and narrow gypsophiles in organ nutrient concentration, we ran two different phylogenetic mixed models for each nutrient and organ: an intercept model and a ‘no-intercept’ model. Intercept models were used to estimate differences among gypsum affinity types. No-intercept models were used to estimate average nutrient concentrations for each gypsum affinity group. Comparisons between levels of factors were considered significant when the credible intervals of estimated posterior means did not span zero and more accurate when credible intervals were narrow (Verdú et al., 2011). We present all studied credible intervals and effect sizes, except in the case of the effect of soil nutrient concentration on each organ nutrient concentration, for which we provide only the credible intervals.

Phylogeny can have an important influence on plant nutrient concentration. The inclusion of phylogenetic relationships and species identity as random effects allowed us to interpret the effect of phylogeny on plant nutrient concentration. We partitioned the residual variance into three components: (1) intergeneric variance caused by phylogenetic relationships; (2) non-phylogenetic, interspecific variance; and (3) intraspecific variance. The interspecific phylogenetic variance quantified the variability explained by the relationships among taxa as defined by our phylogenetic hypothesis and, when divided by the total variance, provided a measure of the phylogenetic signal (λ) (Lynch, 1991). Non-phylogenetic intergeneric variance (γ) accounted for the proportion of among-species variability not explained by the phylogeny, and the intraspecific variance (ρ) provided a measure of the proportion of variability caused by intraspecific trait variation (plus any residual error) (Hadfield and Nakagawa, 2010). To interpret the effect of phylogeny on plant nutrient concentration, we used models without fixed effects for each nutrient in each organ, because the effect of random factors was the same with or without fixed effects (Hadfield and Nakagawa, 2010).

Plant organs have different nutritional functions, hence different nutrient concentrations. We ran an intercept phylogenetic mixed model and a ‘no-intercept’ phylogenetic mixed model for each studied mineral nutrient to interpret the differences between organs and to estimate a concentration for each organ, respectively. In addition, we performed a reconstruction using the contMap function to generate a visual representation of the mineral nutrient concentration across the phylogeny for each organ.

RESULTS

Nutrient concentrations among organs

Leaves, stems, coarse roots and fine roots had different nutrient concentrations, regardless of whether the taxon was a wide gypsophile, gypsovag or narrow gypsophile. Leaves generally had the highest nutrient concentration among organs, followed by fine roots (Table 1). Particularly large differences among organs were observed for Mg, S, N and Ca. The Mg concentration was 4-fold greater in leaves than in fine roots; S and N concentrations were 2-fold greater, and the Ca concentration was 0.6-fold greater between these organs. Coarse roots and stems generally had lower nutrient concentrations than leaves and fine roots (Table 2), especially for S, which was ≤4-fold lower in coarse roots and stems than leaves. Ca and N had the lowest concentrations in stems, and K and Mg in coarse roots. Ca also showed similar concentrations between both root types. For P, leaf concentration was always higher than the concentration in stems, coarse roots and fine roots.

Table 1.

Mineral nutrient concentration across organs. Estimated posterior means (θ) and their credible intervals (95 %) for each nutrient are shown. Letters indicate significant differences among organs for each nutrient.

| Nutrient | Leaf (mg/g) | Stem (mg/g) | Coarse root (mg/g) | Fine root(mg/g) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| θ | CI | θ | CI | θ | CI | θ | CI | |

| Calcium | 37.03 | [29.18, 44.80] a | 11.25 | [2.82, 18.80] c | 19.70 | [11.37, 27.29] b | 22.18 | [13.64, 30.02] b |

| Magnesium | 6.11 | [4.15, 7.70] a | 1.59 | [−0.32, 3.30] b | 0.58 | [−1.30, 2.30] c | 2.17 | [0.25, 3.95] b |

| Sulphur | 16.13 | [12.91, 18.89] a | 4.05 | [1.24, 7.09] c | 3.75 | [0.78, 6.65] c | 8.86 | [5.57, 11.86] b |

| Potassium | 10.63 | [7.44, 13.52] a | 7.89 | [4.66, 10.79] b | 5.25 | [1.81, 8.01] c | 7.57 | [4.35, 10.55] b |

| Phosphorus | 0.82 | [0.64, 1.02] a | 0.49 | [0.27, 0.66] b | 0.56 | [0.36, 0.76] b | 0.51 | [0.32, 0.71] b |

| Nitrogen | 21.92 | [15.04, 29.52] a | 7.68 | [0.53, 14.90] c | 9.27 | [2.46, 16.98] b | 9.60 | [2.15, 16.71] b |

Table 2.

Residual variance partitioning for the nutrient concentration in phylogenetic signal (λ), non-phylogenetic variation among species (γ) and intraspecies variability (ρ) forr each organ. Means and lower and upper 95 % credible intervals (CI) are shown.

| Organ | λ | CI | γ | CI | ρ | CI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Leaf | ||||||

| Calcium | 0.44 | [0.00, 0.81] | 0.39 | [0.06, 0.79] | 0.17 | [0.07, 0.27] |

| Magnesium | 0.26 | [0.00, 0.57] | 0.48 | [0.21, 0.78] | 0.26 | [0.21, 0.37] |

| Sulphur | 0.05 | [0.00, 0.26] | 0.84 | [0.63, 0.94] | 0.11 | [0.06, 0.17] |

| Potassium | 0.11 | [0.00, 0.39] | 0.63 | [0.38, 0.84] | 0.26 | [0.14, 0.37] |

| Phosphorus | 0.10 | [0.01, 0.31] | 0.65 | [0.46, 0.81] | 0.24 | [0.14, 0.35] |

| Nitrogen | 0.48 | [0.10, 0.96] | 0.32 | [0.00, 0.64] | 0.20 | [0.04, 0.32] |

| Stem | ||||||

| Calcium | 0.28 | [0.00, 0.74] | 0.61 | [0.18, 0.93] | 0.12 | [0.05, 0.20] |

| Magnesium | 0.14 | [0.00, 0.48] | 0.59 | [0.29, 0.82] | 0.28 | [0.15, 0.41] |

| Sulphur | 0.04 | [0.00, 0.17] | 0.89 | [0.74, 0.96] | 0.08 | [0.04, 0.12] |

| Potassium | 0.18 | [0.00, 0.49] | 0.61 | [0.32, 0.85] | 0.22 | [0.11, 0.32] |

| Phosphorus | 0.11 | [0.01, 0.30] | 0.57 | [0.39, 0.74] | 0.31 | [0.19, 0.44] |

| Nitrogen | 0.10 | [0.00, 0.41] | 0.54 | [0.26, 0.77] | 0.37 | [0.21, 0.53] |

| Coarse roots | ||||||

| Calcium | 0.41 | [0.00, 0.73] | 0.33 | [0.04, 0.63] | 0.26 | [0.11, 0.40] |

| Magnesium | 0.13 | [0.00, 0.40] | 0.41 | [0.17, 0.62] | 0.46 | [0.27, 0.66] |

| Sulphur | 0.12 | [0.00, 0.43] | 0.47 | [0.20, 0.70] | 0.41 | [0.24, 0.59] |

| Potassium | 0.08 | [0.00, 0.34] | 0.73 | [0.49, 0.90] | 0.18 | [0.09, 0.28] |

| Phosphorus | 0.14 | [0.01, 0.35] | 0.51 | [0.30, 0.72] | 0.36 | [0.21, 0.54] |

| Nitrogen | 0.14 | [0.00, 0.58] | 0.53 | [0.16, 0.78] | 0.33 | [0.17, 0.51] |

| Fine roots | ||||||

| Calcium | 0.15 | [0.00, 0.49] | 0.64 | [0.34, 0.89] | 0.21 | [0.10, 0.33] |

| Magnesium | 0.20 | [0.00, 0.67] | 0.42 | [0.05, 0.70] | 0.38 | [0.17, 0.59] |

| Sulphur | 0.04 | [0.00, 0.22] | 0.85 | [0.68, 0.95] | 0.11 | [0.05, 0.18] |

| Potassium | 0.78 | [0.50, 0.96] | 0.05 | [0.00, 0.23] | 0.17 | [0.05, 0.32] |

| Phosphorus | 0.16 | [0.01, 0.45] | 0.61 | [0.33, 0.84] | 0.23 | [0.09, 0.38] |

| Nitrogen | 0.82 | [0.50, 0.96] | 0.04 | [0.00, 0.24] | 0.14 | [0.04, 0.27] |

Differences between wide gypsophiles, gypsovags and narrow gypsophiles

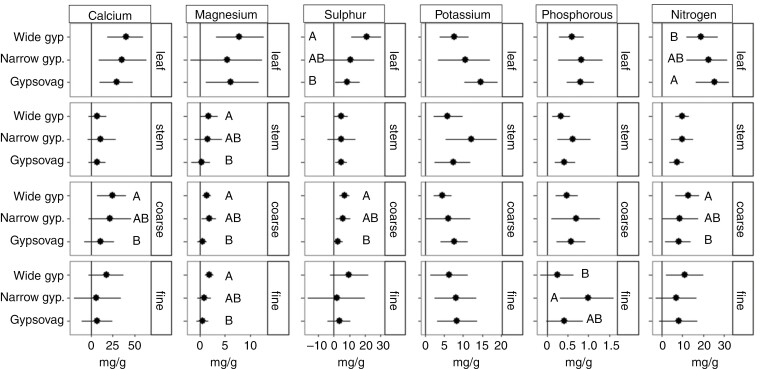

Some organ-level mineral nutrient concentrations varied between wide gypsophiles and gypsovags, whereas narrow gypsophiles often showed broad credible intervals that did not differ significantly from wide gypsophiles and gypsovags. We found that wide gypsophiles and gypsovags differed in leaf S and leaf N (Fig. 1). Wide gypsophiles showed 2.4-fold greater foliar S concentration than gypsovags, whereas gypsovags showed slightly greater leaf N than wide gypsophiles. In stems, we found differences only for Mg concentrations. Wide gypsophiles had 5.8-fold greater Mg concentration than gypsovags. Furthermore, wide gypsophiles had greater coarse root Ca, Mg, S and N concentrations than gypsovags. Wide gypsophiles had 2.7-fold greater fine root Mg concentration than gypsovags, and narrow gypsophiles showed 4.1-fold greater fine root P concentration than wide gypsophiles. Furthermore, in general, there were no differences between wide gypsophiles from the two studied regions, nor were there any differences between gypsovags. However, wide gypsophiles from the Mediterranean showed higher N concentrations in all organs than wide gypsophiles from North America (Supplementary Data Fig. S2).

Fig. 1.

Estimated posterior means (points) and their 95 % credible intervals (lines) of nutrient concentration (in milligrams per gram) for each type of gypsum affinity in each organ. Letters indicate significant differences between gypsum affinity groups.

The effect of phylogeny and species identity

Residual variance partitioning was organ dependent, although phylogeny and species identity had generally determinant effects on plant organ mineral nutrient concentrations (Table 2). Phylogeny generally had a strong effect on foliar and fine root nutrient concentrations but not on stems and coarse roots. Calcium and nitrogen concentrations had stronger phylogenetic signals in leaves (λ > 0.44) than magnesium, potassium, phosphorus or sulphur (Table 2). Focal species belonging to the Caryophyllales showed a high foliar concentration of Ca (Supplementary Data Fig. S3), whereas those of the Poaceae did not, and species of Brassicaceae showed a high N foliar concentration (Supplementary Data Fig. S4), whereas those of the Boraginales did not. In coarse roots, calcium had a strong phylogenetic signal (λ > 0.41), with the Caryophyllales species showing high Ca concentrations and Brassicaceae species having low concentrations (Supplementary Data Fig. S3). In fine roots, nitrogen and potassium showed a strong phylogenetic signal (λ > 0.78), because Brassicaceae species showed high concentrations of both nutrients (Supplementary Data Figs S4 and S5), whereas Caryophyllales and the genus Gaillardia showed only high K concentrations (Supplementary Data Fig. S5).

In contrast, the proportion of non-phylogenetic variation among species (γ; Table 2) was generally large for stem nutrient concentrations (γ > 0.54) and for some nutrients in other organs. Sulphur concentrations in leaves, stems and fine roots were explained mainly by non-phylogenetic variation among species (γ > 0.85). In particular, the wide gypsophiles Haploësthes greggii, Ononis tridentata, Acleisanthes lanceoalata and Lepidium subulatum showed high S concentration in leaves, the gypsovag Abronia angustifolia in stems, and the wide gypsophile Sporobolus nealleyi in fine roots (Supplementary Data Fig. S6). Likewise, the proportion of non-phylogenetic effects was high for K concentration in leaves, stems and coarse roots (γ > 0.61). For example, the gypsovag Anulocaulis eriosolenus showed high K in leaves, stems and coarse roots (Supplementary Data Fig. S5). P concentration in all organs was also explained mainly by non-phylogenetic variation (γ > 0.51). The gypsovag Boerhavia coccinea and the wide gypsophile Gypsophila struthium had higher P concentration in leaves; the gypsovag Anulocaulis eriosolenus and the narrow gypsophile Abronia nealleyi in stems; the gypsovags Anulocaulis eriosolenus and Acleisanthes angustifolia and the wide gypsophile Acleisanthes lanceolata in coarse roots, and the narrow gypsophile Abronia nealleyi in fine roots (Supplementary Data Figs S7 and S8 for Mg). The variation explained by intraspecies variability on nutrient concentration was generally low in all organs (ρ < 0.46; Table 2).

The effect of soil concentration

The mineral nutrient concentration across plant organs was generally not affected by soil nutrient concentration (Supplementary Data Table S3, see means per species). However, foliar sulphur and stem calcium were positively affected by soil sulphur and calcium concentrations, respectively (Table 3). In contrast, foliar and coarse root phosphorus concentrations and stem and coarse root potassium concentrations were negatively and significantly affected by their soil concentrations.

Table 3.

Credible intervals (95 %) of estimated posterior means of soil concentration effect on the nutrient concentration for each organ. Bold type on intervals indicates significant effects.

| Organ | Calcium | Magnesium | Sulphur | Potassium | Phosphorus |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Leaf | [−0.13, 0.81] | [−0.18, 0.59] | [0.06, 0.20] | [−30.04, 10.79] | [−0.24, −0.07] |

| Stem | [0.13, 0.73] | [−0.87, 0.35] | [−0.04, 0.04] | [−37.17, −0.09] | [−0.19, 0.02] |

| Coarse root | [−0.48, 0.66] | [−0.10, 0.43] | [−0.05, 0.03] | [−27.59, −1.29] | [−27.59, −1.29] |

| Fine root | [−0.23, 1.39] | [−0.13, 0.45] | [−0.21, 0.18] | [−13.93, 20.18] | [−0.24, 0.17] |

DISCUSSION

Nutritional convergence among gypsum specialists

Our study highlights that gypsum specialization is strongly correlated with nutrient composition. We observed, for the first time, a nutritional convergence between wide gypsophiles belonging to two different climatic regions (the Iberian Peninsula and the Chihuahuan Desert) and belonging to different gypsophilous lineages. We observed that foliar S concentrations and whole-plant Mg concentrations are explained mainly by non-phylogenetic variation between species. Furthermore, we found higher S and Mg concentrations in wide gypsophiles than in congenerics or confamilial gypsovags, similar to studies in the Iberian Peninsula (Palacio et al., 2022) and the Chihuahuan Desert Region (Muller et al., 2017). These results suggest that dominant, widely distributed gypsophiles are typically gypsum specialists (Palacio et al., 2007) with a unique nutritional composition characterized by high foliar concentrations of sulphur and magnesium, regardless of different climatic regions or lineages. In contrast, we observed broad variability among narrow gypsophiles in nutrient composition, which prevent a classification apart from wide gypsophiles or gypsovags, similar to studies in Spain (Palacio et al., 2007), Turkey (Bolukbasi et al., 2016) and the USA (Muller et al., 2017). The lack of a unique nutrient composition in many narrow gypsophiles might reflect that they belong to young gypsophile lineages and thus have had insufficient time to develop adaptive mechanisms convergent with wide gypsophiles (Moore et al., 2014) or because they are palaeoendemics that found gypsum soils as a refuge soil with low plant competition (Escudero et al., 2015).

Some nutrient concentrations were less explained by gypsum specialization, and in these cases, factors such as phylogeny have a stronger impact. For instance, we found that some nutrient concentrations, such as foliar calcium and nitrogen or fine root potassium, had a strong phylogenetic signal at the order or family level. In contrast, some elements had a low phylogenetic signal, with gypsum specialists and non-specialists having similar concentrations, suggesting species-specific physiology. These findings are in agreement with separate previous studies on foliar composition in the Iberian Peninsula (Palacio et al., 2022) and Chihuahuan Desert Region (Muller et al., 2017). Hence, ancient evolutionary events (e.g. early in the evolution of modern orders and families), recent specialization events and other species-specific adaptations seem to shape nutrient concentrations in unique soils more than climate factors for some elements, as we observed by comparing plants growing in gypsum soils from two distinct climatic regions.

Evolutionary events have strong effects on plant nutrient concentrations

Studying nutrient composition within a phylogenetic framework reveals the importance of evolutionary events in determining plant nutritional strategies. It is well established that phylogeny is strongly correlated with foliar composition at the levels of family and order diversification (Neugebauer et al., 2018; Palacio et al., 2022), as we observed in some nutrient concentrations. This ancestral phylogenetic signal could indicate conservation of certain metabolic processes acquired during the early stages of Angiosperm evolution (Watanabe et al., 2007). Thus, the incorporation of phylogenetic relationships in our studies sheds light on the evolution of edaphic specialists growing in different regions with distinct floras. In our case, it explains why dominant, widely distributed gypsophiles and their unique nutrient composition occur in only certain families or orders (Moore et al., 2014) and might indicate a predisposition of some older clades (e.g. Caryophyllales, asterids) to develop metabolic pathways to adapt to extreme soils. Many gypsophiles belong to Caryophyllales, which accumulate foliar Ca and Mg (White et al., 2018), and Brassicales, which accumulate foliar N and S (Neugebauer et al., 2018). These preserved patterns have previously been studied mainly at the leaf level, but our study emphasizes that they can also be observed within a whole-plant perspective. For example, our Poaceae taxa showed low foliar Ca and S, regardless of their gypsum affinity, but they accumulated these elements in fine roots. This strategy to accumulate excess mineral nutrients in roots, with limited translocation to the above-ground organs, is commonly observed in Poaceae taxa in various ecosystems, such as saltmarshes or metalliferous soils (Tran et al., 2020).

Species identity explained differences in nutrient concentrations, regardless of family, order or intraspecific variation. An ancestral phylogenetic signal was not a determinant of sulphur and magnesium concentrations in various organs, but unrelated gypsum specialists had similar sulphur and magnesium patterns across organs. These results reinforce the nutritional convergence of gypsum specialization at the species level, along with differences between gypsum specialists and non-specialists. In addition, these results agree with previous findings that the recent diversification of Iberian gypsum plants explains the largest proportion of the total variance in plant nutrient composition (Palacio et al., 2022). There was also a strong effect of species identity on the residual variability of phosphorus concentrations in all organs, but unlike sulphur and magnesium, it was not aligned with gypsum specialization. These species-specific patterns might indicate different strategies to enhance phosphorus nutrition (Lambers, 2022), which is very scarce in gypsum soils (Mota et al., 2017; Cera et al., 2021a), especially in the Chihuahuan Desert Region. A strong non-phylogenetic effect was also observed for potassium, but it also was not related with gypsum specialization. Most species belonging to gypsophilous lineages are calcicole species or have calcicole ancestors (Muller et al., 2017; Heiden et al., 2022), with many having a K/Ca ratio below one in leaves (Kinzel, 1989), and probably having different strategies to regulate potassium concentrations. Hence, species identity explains the variation of nutrient concentrations, with some nutrient patterns being related to gypsum specialization, such as sulphur and magnesium, whereas others, such as potassium and phosphorus, might be linked to different strategies to cope with nutritional imbalances in gypsum soils.

Whole-plant composition explains nutritional strategies in gypsum plants

Our study highlights that whole-plant nutrient composition describes plant nutritional strategies better than foliar composition alone. Organs vary in nutrient composition owing to their different functions in mineral nutrition (Rengel et al., 2022), and this distinction among organs was preserved regardless of taxonomical or ecological species classification in our study (Zhao et al., 2016, 2020; Neugebauer et al., 2020). Leaves had the highest concentrations of the studied mineral nutrients, followed by fine roots, then stems and coarse roots. As the photosynthetic organ of most of the study species, leaves require higher concentrations of nitrogen, magnesium, sulphur and phosphorus (Zhao et al., 2016; Rengel et al., 2022). Particularly for specialist species, leaves accumulate and manage high concentrations of nutrients to avoid nutrient imbalances (Hogan et al., 2021). In contrast to leaves, the function of fine roots is mainly nutrient acquisition (Lambers et al., 2008), which requires high metabolic activity, hence nutrients such as nitrogen (Roumet et al., 2016). Fine roots also play an important role in avoiding excessive content of essential and toxic nutrients in above-ground parts (Ricachenevsky et al., 2018), particularly for species growing in atypical soils. In contrast, stems and coarse roots showed the lowest concentrations, probably because they show a lower metabolic activity and are mainly transport and storage organs (Zhao et al., 2020; Rengel et al., 2022).

The nutritional strategy of gypsum plants was explained by foliar and fine root nutrient concentrations. In gypsum soils, calcium, sulphur and, sometimes, magnesium soil availability exceeds plant requirements (Merlo et al., 2019). Plants growing in gypsum soils can retain these nutrients in fine roots to avoid metabolic interferences in leaves, using apoplastic barriers for calcium (Lux et al., 2021) and regulating sulphate and magnesium transporters according to above-ground organ demand (Davidian and Kopriva, 2010; Tang and Luan, 2017). Plants did not accumulate phosphorus or nitrogen in fine roots, probably because they are scarce in gypsum soils (Cera et al., 2021a). Moreover, wide gypsophiles are physiologically adapted to gypsum soil, which is a hypercalcic soil with harsher conditions than other calcareous soils. These specialists might have developed a physiological tolerance mechanism to regulate Ca accumulation and P restriction typical of calcareous soils and accentuated in gypsum soils. Such a physiological tolerance mechanism might involve using excess S and Mg in leaves to regulate excess Ca and prevent its precipitation with P. This strategy would explain the unique plant composition of wide gypsophiles (Cera et al., 2023). Therefore, a whole-plant perspective is required to understand plant–soil interactions, in particular plant specialization, especially studying leaves and fine roots.

Future perspectives in the nutritional strategies of gypsum plants

We confirmed a convergence in the nutritional strategy of gypsum specialists in two different regions. Future studies should address convergence between wide gypsophiles in other regions with gypsum soils, such as Somalia, South Africa, Australia, central Asia or the Middle East. The interpretation of nutrient concentrations within a phylogenetic framework and the comparison between soil specialists and non-specialists from two different climatic regions allowed us to discriminate whether nutrient concentrations were determined by soil specialization, by ancestral evolutionary events and/or by climatic factors. This approach should be incorporated in other ecosystems with unique soils to ascertain the main determinants of nutrient concentrations. Future studies should also test whether leaves and fine roots are useful for describing the nutritional strategies of plants to cope with unique soils (e.g. saline and serpentine soils) within an evolutionary framework, rather than only studying leaves. Additionally, our findings on nutritional strategy are described at the elemental level. Therefore, further studies are needed to establish connections between ion transport, storage, assimilated molecules and other metabolic processes with the ecological and evolutionary patterns described in this work.

SUPPLEMENTARY DATA

Supplementary data are available at Annals of Botany online and consist of the following.

Table S1: species, their family, gypsum affinity group and sampling site. Table S2: list of the ten species included in the initial tree constructed with V.PhyloMaker. Table S3: soil elemental concentration per species. Figure S1: climatic diagrams of closed locations extracted from the study by Zepner et al. (2020) to highlight the seasonality of rainfall. Figure S2: estimated posterior means (points) and their 95 % credible intervals (lines) of nutrient concentration (in milligrams per gram) for each type of gypsum affinity (V vs. W) in each organ and region (NA vs. Med). Figure S3: calcium concentration (in milligrams per gram) across the phylogeny for each organ. Figure S4: nitrogen concentration (in milligrams per gram) across the phylogeny for each organ. Figure S5: potassium concentration (in milligrams per gram) across the phylogeny for each organ. Figure S6: sulphur concentration (in milligrams per gram) across the phylogeny for each organ. Figure S7: phosphorus concentration (in milligrams per gram) across the phylogeny for each organ. Figure S8: magnesium concentration (in milligrams per gram) across the phylogeny for each organ.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank M. Setter and M. Nichols for laboratory analysis guidance and support, N. Pietrasiak for helpful discussion of the research objectives and approaches, and M. Iannucci, S. Pavsek, R. Reicholf, M. Twarog, V. Fung, R. Nielsen, M. McNicholas, G. Montserrat-Martí, E. Lahoz, M. Pérez-Serrano, E. Salmerón-Sánchez, F. J. Pérez-García, M. E. Merlo, F. Martínez-Hernández, A. F. Mendoza-Fernández and N. Heiden for help with sample processing and preparation. We also thank the New Mexico Field Office of the Bureau of Land Management for access to field sites.

Contributor Information

Clare T Muller, Biology Department, John Carroll University, University Heights, OH, USA.

Andreu Cera, UMR 950 EVA, INRAE, Université de Caen-Normandie, Caen, France.

Sara Palacio, Departamento Biodiversidad y Restauración, Instituto Pirenaico de Ecología, Consejo Superior de Investigaciones Científicas, Jaca, Spain.

Michael J Moore, Department of Biology, Oberlin College, Oberlin, OH, USA.

Pablo Tejero, Departamento Biodiversidad y Restauración, Instituto Pirenaico de Ecología, Consejo Superior de Investigaciones Científicas, Jaca, Spain.

Juan F Mota, Departamento de Biología y Geología, Universidad de Almería, Almería, Spain.

Rebecca E Drenovsky, Biology Department, John Carroll University, University Heights, OH, USA.

FUNDING

This work was supported by the National Science Foundation (NSF DEB-1054539), the Native Plant Society of New Mexico, the Ministry of Science, Innovation and Universities (MCIN, Spain, PID2019-111159GB-C3) and the European Commission (H2020-MSCA-RISE-2017 program, project GYPWORLD GA 777803).

LITERATURE CITED

- Bolukbasi A, Kurt L, Palacio S.. 2016. Unravelling the mechanisms for plant survival on gypsum soils: an analysis of the chemical composition of gypsum plants from Turkey. Plant Biology 18: 271–279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casby-Horton S, Herrero J, Rolong NA.. 2015. Chapter four - gypsum soils—their morphology, classification, function, and landscapes. In: Sparks DL, ed. Advances in agronomy. New York: Academic Press, 231–290. [Google Scholar]

- Cera A, Duplat E, Montserrat-Martí G, Gómez-Bolea A, Rodríguez-Echeverría S, Palacio S.. 2021a. Seasonal variation in AMF colonisation, soil and plant nutrient content in gypsum specialist and generalist species growing in P-poor soils. Plant and Soil 468: 509–524. [Google Scholar]

- Cera A, Montserrat-Martí G, Ferrio JP, Drenovsky RE, Palacio S.. 2021b. Gypsum-exclusive plants accumulate more leaf S than non-exclusive species both in and off gypsum. Environmental and Experimental Botany 182: 104294. [Google Scholar]

- Cera A, Montserrat-Martí G, Drenovsky RE, Ourry A, Brunel-Muguet S, Palacio S.. 2022. Gypsum endemics accumulate excess nutrients in leaves as a potential constitutive strategy to grow in grazed extreme soils. Physiologia Plantarum 174: e13738. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cera A, Montserrat-Martí G, Palacio S.. 2023. Nutritional strategy underlying plant specialization to gypsum soils. AoB Plants 15: plad041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davidian J-C, Kopriva S.. 2010. Regulation of sulfate uptake and assimilation—the same or not the same? Molecular Plant 3: 314–325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Escudero A, Palacio S, Maestre FT, Luzuriaga AL.. 2015. Plant life on gypsum: a review of its multiple facets. Biological Reviews of the Cambridge Philosophical Society 90: 1–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guerrero-Campo J, Alberto F, Maestro M, Hodgson J, Montserrat-Martí G, Montserrat-Martí G.. 1999. Plant community patterns in a gypsum area of NE Spain. II. Effects of ion washing on topographic distribution of vegetation. Journal of Arid Environments 41: 411–419. [Google Scholar]

- Hadfield J. 2023. MCMCglmm: MCMC Generalised Linear Mixed Models. https://github.com/jarrodhadfield/MCMCglmm(15 September 2023, date last accessed).

- Hadfield JD, Nakagawa S.. 2010. General quantitative genetic methods for comparative biology: phylogenies, taxonomies and multi-trait models for continuous and categorical characters. Journal of Evolutionary Biology 23: 494–508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heiden N, Cera A, Palacio S.. 2022. Do soil features condition seed germination of gypsophiles and gypsovags? An analysis of the effect of natural soils along an alkalinity gradient. Journal of Arid Environments 196: 104638. [Google Scholar]

- Hogan JA, Valverde-Barrantes OJ, Tang W, Ding Q, Xu H, Baraloto C.. 2021. Evidence of elemental homeostasis in fine root and leaf tissues of saplings across a fertility gradient in tropical montane forest in Hainan, China. Plant and Soil 460: 625–646. [Google Scholar]

- Jin Y, Qian H.. 2019. V.PhyloMaker: an R package that can generate very large phylogenies for vascular plants. Ecography 42: 1353–1359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kazakou E, Dimitrakopoulos PG, Baker AJM, Reeves RD, Troumbis AY.. 2008. Hypotheses, mechanisms and trade-offs of tolerance and adaptation to serpentine soils: from species to ecosystem level. Biological Reviews of the Cambridge Philosophical Society 83: 495–508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kinzel H. 1989. Calcium in the vacuoles and cell walls of plant tissue. Flora 182: 99–125. [Google Scholar]

- Lambers H. 2022. Phosphorus acquisition and utilization in plants. Annual Review of Plant Biology 73: 17–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lambers H, Oliveira RS.. 2019. Introduction: history, assumptions, and approaches. In: Lambers H, Oliveira RS, eds. Plant physiological ecology. Cham: Springer International, 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Lambers H, Chapin FS, Pons TL.. 2008. Mineral nutrition. In: Lambers H, Chapin FS, Pons TL, eds. Plant physiological ecology. New York, NY: Springer, 255–320. [Google Scholar]

- Lux A, Kohanová J, White PJ.. 2021. The secrets of calcicole species revealed. Journal of Experimental Botany 72: 968–970. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lynch M. 1991. Methods for the analysis of comparative data in evolutionary biology. Evolution 45: 1065–1080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merlo ME, Garrido-Becerra JA, Mota JF, et al. 2019. Threshold ionic contents for defining the nutritional strategies of gypsophile flora. Ecological Indicators 97: 247–259. [Google Scholar]

- Meyer SE. 1986. The ecology of Gypsophile endemism in the Eastern Mojave Desert. Ecology 67: 1303–1313. [Google Scholar]

- Moore M, Mota J, Douglas N, Flores-Olvera H, Ochoterena H.. 2014. The ecology, assembly, and evolution of gypsophile floras. In: Plant ecology and evolution in harsh environments. Hauppauge, NY: Nova Science, 97–128. [Google Scholar]

- Mota JF, Sánchez-Gómez P, Guirado JS.. 2011. Diversidad vegetal de las yeseras ibéricas. El reto de los archipiélagos edáficos para la biología de la conservación. Almería: ADIF-Mediterráneo Asesores Consultores. [Google Scholar]

- Mota JF, Garrido-Becerra JA, Merlo ME, Medina-Cazorla JM, Sánchez-Gómez P.. 2017. The Edaphism: gypsum, dolomite and serpentine flora and vegetation. In: Loidi J, ed. Plant and vegetation. The vegetation of the Iberian Peninsula, Vol. 2. Cham: Springer International, 277–354. [Google Scholar]

- Mota J, Merlo E, Martínez-Hernández F, Mendoza-Fernández AJ, Pérez-García FJ, Salmerón-Sánchez E.. 2021. Plants on rich-magnesium dolomite barrens: a global phenomenon. Biology 10: 38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muller CT, Moore MJ, Feder Z, Tiley H, Drenovsky RE.. 2017. Phylogenetic patterns of foliar mineral nutrient accumulation among gypsophiles and their relatives in the Chihuahuan Desert. American Journal of Botany 104: 1442–1450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Munns R, Tester M.. 2008. Mechanisms of salinity tolerance. Annual Review of Plant Biology 59: 651–681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Munson SM. 2013. Plant responses, climate pivot points, and trade-offs in water-limited ecosystems. Ecosphere 4: 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- Neugebauer K, Broadley MR, El‐Serehy HA, et al. 2018. Variation in the angiosperm ionome. Physiologia Plantarum 163: 306–322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neugebauer K, El‐Serehy HA, George TS, et al. 2020. The influence of phylogeny and ecology on root, shoot and plant ionomes of 14 native Brazilian species. Physiologia Plantarum 168: 790–802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ochoterena H, Flores-Olvera H, Gómez-Hinostrosa C, Moore MJ.. 2020. Gypsum and plant species: a marvel of Cuatro Ciénegas and the Chihuahuan Desert. In: Mandujano MC, Pisanty I, Eguiarte LE, eds. Cuatro Ciénegas Basin: an endangered hyperdiverse Oasis. Plant diversity and ecology in the Chihuahuan desert: emphasis on the Cuatro Ciénegas Basin. Cham: Springer International, 129–165. [Google Scholar]

- Palacio S, Cera A, Escudero A, et al. 2022. Recent and ancient evolutionary events shaped plant elemental composition of edaphic endemics. A phylogeny-wide analysis of Iberian gypsum plants. The New Phytologist 235: 2406–2423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palacio S, Escudero A, Montserrat-Martí G, Maestro M, Milla R, Albert MJ.. 2007. Plants living on gypsum: beyond the specialist model. Annals of Botany 99: 333–343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parsons RF. 1976. Gypsophily in plants—a review. The American Midland Naturalist 96: 1–20. [Google Scholar]

- Pérez-García FJ, Martínez-Hernández F, Mendoza-Fernández AJ, et al. 2017. Towards a global checklist of the world gypsophytes: a qualitative approach. Plant Sociology 54(Suppl. 1): 61–76. [Google Scholar]

- Rajakaruna N. 2018. Lessons on evolution from the study of edaphic specialization. The Botanical Review 84: 39–78. [Google Scholar]

- Rengel Z, Cakmak I, White P.. 2022. Marschner’s mineral nutrition of plants. Academic Press. [Google Scholar]

- Ricachenevsky FK, de Araújo Junior AT, Fett JP, Sperotto RA.. 2018. You shall not pass: root vacuoles as a symplastic checkpoint for metal translocation to shoots and possible application to grain nutritional quality. Frontiers in Plant Science 9: 412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roumet C, Birouste M, Picon‐Cochard C, et al. 2016. Root structure–function relationships in 74 species: evidence of a root economics spectrum related to carbon economy. New Phytologist 210: 815–826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sardans J, Alonso R, Carnicer J, Fernández-Martínez M, Vivanco MG, Peñuelas J.. 2016. Factors influencing the foliar elemental composition and stoichiometry in forest trees in Spain. Perspectives in Plant Ecology, Evolution and Systematics 18: 52–69. [Google Scholar]

- Tang R-J, Luan S.. 2017. Regulation of calcium and magnesium homeostasis in plants: from transporters to signaling network. Current Opinion in Plant Biology 39: 97–105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tran TKA, Islam R, Le Van D, Rahman MM, Yu RMK, MacFarlane GR.. 2020. Accumulation and partitioning of metals and metalloids in the halophytic saltmarsh grass, saltwater couch, Sporobolus virginicus. The Science of the Total Environment 713: 136576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verdú M, Gómez-Aparicio L, Valiente-Banuet A.. 2011. Phylogenetic relatedness as a tool in restoration ecology: a meta-analysis. Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences 279: 1761–1767. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watanabe T, Broadley MR, Jansen S, et al. 2007. Evolutionary control of leaf element composition in plants. The New Phytologist 174: 516–523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White PJ, Broadley MR, El-Serehy HA, George TS, Neugebauer K.. 2018. Linear relationships between shoot magnesium and calcium concentrations among angiosperm species are associated with cell wall chemistry. Annals of Botany 122: 221–226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whittaker RH. 1954. The ecology of serpentine soils. Ecology 35: 258–288. [Google Scholar]

- Zepner L, Karrasch P, Wiemann F, Bernard L. 2020. ClimateCharts.net – an interactive climate analysis web platform. International Journal of Digital Earth 14: 338–356. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao N, Yu G, He N, et al. 2016. Coordinated pattern of multi-element variability in leaves and roots across Chinese forest biomes. Global Ecology and Biogeography 25: 359–367. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao N, Yu G, Wang Q, et al. 2020. Conservative allocation strategy of multiple nutrients among major plant organs: from species to community. Journal of Ecology 108: 267–278. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.