Abstract

Since late 2021, a panzootic of highly pathogenic H5N1 avian influenza virus has driven significant morbidity and mortality in wild birds, domestic poultry, and mammals. In North America, infections in novel avian and mammalian species suggest the potential for changing ecology and establishment of new animal reservoirs. Outbreaks among domestic birds have persisted despite aggressive culling, necessitating a re-examination of how these outbreaks were sparked and maintained. To recover how these viruses were introduced and disseminated in North America, we analyzed 1,818 Hemagglutinin (HA) gene sequences sampled from North American wild birds, domestic birds and mammals from November 2021-September 2023 using Bayesian phylodynamic approaches. Using HA, we infer that the North American panzootic was driven by ~8 independent introductions into North America via the Atlantic and Pacific Flyways, followed by rapid dissemination westward via wild, migratory birds. Transmission was primarily driven by Anseriformes, shorebirds, and Galliformes, while species such as songbirds, raptors, and owls mostly acted as dead-end hosts. Unlike the epizootic of 2015, outbreaks in domestic birds were driven by ~46–113 independent introductions from wild birds, with some onward transmission. Backyard birds were infected ~10 days earlier on average than birds in commercial poultry production settings, suggesting that they could act as “early warning signals” for transmission upticks in a given area. Our findings support wild birds as an emerging reservoir for HPAI transmission in North America and suggest continuous surveillance of wild Anseriformes and shorebirds as crucial for outbreak inference. Future prevention of agricultural outbreaks may require investment in strategies that reduce transmission at the wild bird/agriculture interface, and investigation of backyard birds as putative early warning signs.

Introduction

Highly pathogenic avian influenza (HPAI) viruses pose persistent challenges for human and animal health. Since emerging in 1996, highly pathogenic H5N1 viruses of the A/goose/Guangdong lineage have spread globally via endemic transmission among domestic birds in Asia and Africa coupled with long-distance dispersal by wild migrating birds (1,2). In 2005, introduction of poultry-derived H5N1 viruses into wild birds in China led to viral dispersal across Northern Africa and Asia, establishing new lineages of endemic circulation in poultry (3,4). In 2014, wild, migratory birds carried highly pathogenic H5N8 viruses from Europe to North America, sparking an outbreak that resulted in the culling of over 50.5 million commercial birds (5). While this outbreak substantially impacted the agriculture industry, aggressive culling quelled the outbreak, and North America remained free of HPAI for years.

Since December 2021, clade 2.3.4.4b HPAI H5N1 viruses have spread across the Americas, causing a panzootic of significant morbidity and mortality in wild and domestic animals. These viruses were likely first introduced into North America in late 2021 by migratory birds flying across the Arctic Circle from Europe (6,7), after which reassortment with endemic, low-pathogenicity avian influenza (LPAI) North American H5Nx (where Nx refers to various Neuraminidase (NA) subtypes) viruses produced a virus with altered tissue tropism in mammals (8). In contrast to past epizootics, morbidity and mortality has been widespread across a broad range of wild avian species not usually impacted by HPAI (9) such as raptors, owls, passerines (1,10), and Sandwich Terns (11–13). Infections have also occurred in mammal species not typically associated with HPAI, such as foxes, skunks, raccoons, harbor seals, dolphins, bears (1,14), and recently, domestic goats and dairy cattle (15). Putative transmission among marine mammals and domestic dairy cattle pose new challenges for animal health and biosecurity, and highlight the need to understand the ecological factors that lead to spillover (15,16).

Historically, H5N1 transmission has been linked to poultry production, with occasional cross-continental movement by wild birds of the Anseriformes (waterfowl such as ducks and geese) and Charadriiformes (Shorebirds) orders (17–19). Unlike the North American epizootic in 2014–2015, widespread culling of domestic birds has not halted detections in North America, suggesting that patterns of transmission since 2022 may be distinct from past epizootics. Prior work has posited that clade 2.3.4.4b viruses may be better able to infect and transmit among wild bird species, leading to persistent, seasonal circulation in European wild birds (11,13). Early genomic analysis of the United States epizootic linked outbreaks in poultry to wild birds, though the robustness of these results to differences in sampling between wild and domestic birds was not directly examined (10). Designing effective surveillance and intervention strategies hinges on delineating which species are driving transmission in North America, a question that remains understudied. The broad range of affected wild species in this panzootic raises the possibility that new reservoir hosts could be established, necessitating an evaluation of which species should be actively surveilled. Finally, while it is currently thought that cases in mammals likely stem from infections in wild birds, work to formally link infections across species has been sparse.

Viral phylodynamic approaches are emerging as critical tools for outbreak reconstruction (20,21). Viral genomes contain molecular records of transmission histories, allowing them to be used to trace how outbreaks begin and spread. Here we use Bayesian phylogeographic approaches paired with rigorous controls for sampling bias (22,23) to trace how highly pathogenic H5N1 viruses were introduced and disseminated across North America. We capitalize on a dataset of 1,818 Hemagglutinin gene sequences sampled from North American birds and mammals in 2021–2023, and curate additional metadata on geography, migratory flyways, domestic/wild status, host taxonomic order, and migratory behavior to reconstruct transmission between these groups. Using this dataset of HA sequences, we show that the epizootic in North America was driven by ~ 8 independent introductions that descend from outbreaks in Europe and Asia, though only a single introduction spread successfully across the continent. The initial wave of H5N1 transmission spread from east to west by wild, migratory birds between adjacent migratory flyways. Transmission from non-canonical avian species like songbirds and owls was limited and resulted in dead-end transmission chains, suggesting that these species are unlikely to establish as reservoirs. Instead, transmission was primarily sustained by Anseriformes, shorebirds, and Galliformes. In contrast to the outbreak in 2014/2015, outbreaks in agriculture were seeded by ~46–113 independent introductions from wild birds, with some onward transmission. Backyard birds were infected slightly more frequently, and earlier on average, than commercial birds, suggesting that increased backyard bird surveillance could serve as early warning signs for increased incidence. Together, these data pinpoint surveillance in wild aquatic birds as critical for contextualizing outbreaks in mammals and agriculture. Given the increasing role of wild bird transmission in North America, investment in interventions that reduce interactions between domestic and wild animals may now be crucial for limiting future outbreaks in agriculture.

Results

Viral sequence data capture seasonal variation of HPAI detections

In the United States, the United State Department of Agriculture Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service (APHIS) manages HPAI surveillance and testing in wild birds via investigation of reported morbidity and mortality events, hunter-harvested game birds/waterfowl, sentinel species/live bird collection, and environmental sampling of water bodies and surfaces (24,25). As of September 30th 2024, most HPAI detections have been reported in wild birds, which were sampled via testing of sick and dead (5,611), hunter harvested (3,340), and live wild birds (1,127) (Figure S1a). APHIS also surveilles domestic birds using several reporting methods: mandatory testing through the National Poultry Improvement Plan, coordination with state agricultural agencies, routine testing in high-risk areas, and backyard flock surveillance (26). Data on domestic bird detections are reported with information on poultry type (e.g., duck, chicken) and by whether the farm is classified as a commercial operation or backyard flock. Backyard flocks are categorized by the USDA as operations with fewer than 1,000 birds (27,28) and by the World Organization for Animal Health (WOAH) as any birds kept in captivity for reasons other than for commercial production (29). Among domestic birds, detections (1,177 total) came predominantly from commercial chickens (9.3%), commercial turkeys (28.5%), commercial breeding operations (species unspecified) (15.3%), and birds designated WOAH Non-Poultry which refers to backyard birds (42.3%) (Figure S1b). Other domestic bird detections occurred in game bird raising operations (2.5%) and commercial ducks (2.0%). This panzootic has notably impacted a broad range of mammalian hosts, with detections (399) reported in red foxes (24.3%), mice (24.1%), skunks (12.2%), and domestic cats (13.2%). Other mammalian hosts (26.2%) represent a wide range of species including harbor seals, bobcats, fishers, and bears (Figure S1c).

The first detection of HPAI H5N1 viruses in the United States occurred in a wild American wigeon in South Carolina on December 30th, 2021. From January – May 2022, a wave of 2,510 total detections were reported across 43 states and 91 different species (Figure 1). Following a lull in the summer, cases rose again in August 2022, leading to a larger epizootic wave that lasted until March 2023, totaling 8,001 detections across all 48 contiguous U.S. states and Alaska. Case detections peaked in the fall and spring, coinciding roughly with seasonal migration timing for birds migrating between North and South America (30,31). Seasonal case variation could arise due to seasonal bird migration, fluctuating virus prevalence in wild birds, or fledging times of susceptible chicks (32), though continued monitoring is necessary to determine whether these patterns persist in future years.

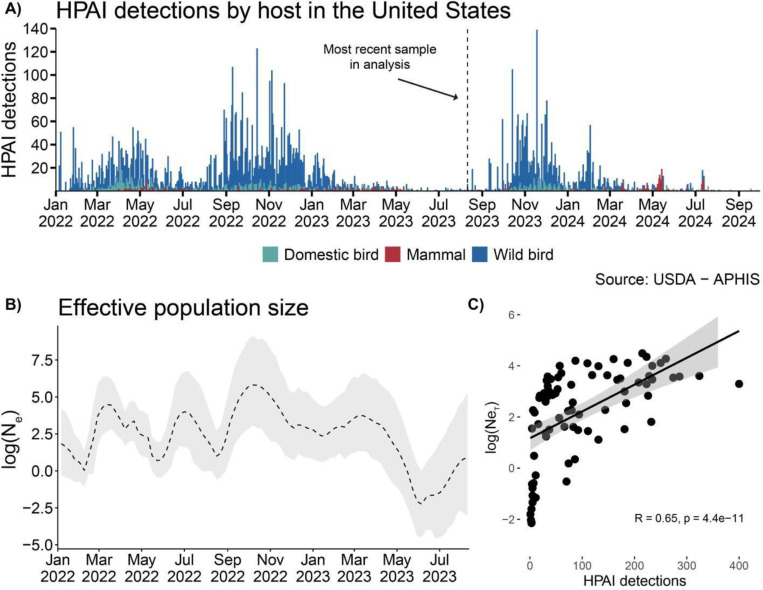

Figure 1. Detections of HPAI in North America show distinct epidemic waves following introduction events in late 2021.

A) Detections of HPAI in wild birds, domestic birds, and non-human mammals. B) The Log-scaled Effective population size (Ne) estimates estimated in BEAST using the Bayesian SkyGrid coalescent for sequences collected between Sep 2021 and Aug 2023. C) Correlation plot of log(Ne) vs HPAI detections by week, spearman correlation displayed.

Sequence data sampled in North America is heavily skewed toward the first 6 months of the outbreak, with 74% of all available sequences sampled from January-July 2022 (Figure S2). To evaluate whether sequence data reflect case detections, we inferred the viral effective population size (Ne), a measure that approximates viral incidence (21). Using 6 datasets of sequences subsampled by host taxonomic order (see Methods for details), we infer that Ne is modestly correlated with detections (highest Spearman rank correlation: 0.65, p=4.4e-11) (Figure 1c)(Figure S3–4), and that peaks in Ne precede peaks in detections by ~1 week (Figure S5), likely reflecting the lag between viral transmission and case detection. These data suggest that despite uneven sequence acquisition across time, the diversity of sampled sequences reflect the amplitude of H5N1 cases. We therefore opted to use sequence data for the entire sampling period for broad inferences on introductions and geographic spread across North America, but supplement these analyses with a series of controls for sampling differences between groups. For more intensive reconstructions of transmission patterns between wild birds, commercial poultry, and backyard birds we focus on the initial 6-month period with the most densely sampled data, coupled with experiments to assess the impacts of sampling on results.

Wild, migratory birds drove expansion of H5N1 across the continent

To reconstruct the number and timings of H5N1 introductions into North America, we constructed a dataset that including HA sequences from North America from domestic and wild birds (n= 1,327 unique isolates, identical sequences were removed), along with contextual sequences from other continents with ongoing outbreaks in 2021 and 2022 (Asia = 294, Europe = 300). We then inferred the number and timings of introductions into North America using a discrete trait phylogeographic model (see Methods for details) (33).

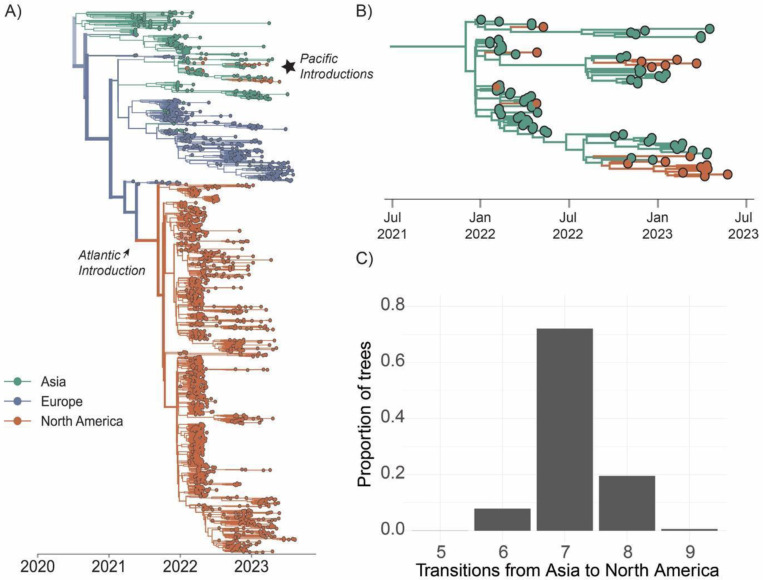

Most sequenced infections in North America (98.5% of tips) descend from a single introduction from Europe in late 2021 (95% Highest Posterior Density (HPD), September 9th – October 7th 2021) (Figure 2a), consistent with reports of infected migratory gulls in Newfoundland and Labrador Canada in November 2021, and subsequent mortality in farmed birds in December of 2021 (6,7,10). Previous surveillance of migratory birds traveling from Europe to North America in October of 2021 recorded detections of HPAI of European origin from wigeons, geese, skua, and gulls (6). We also infer 7 (median = 7, 95% HPD: (6,8)) additional introductions between February and September 2022 that nest within the diversity of viruses circulating in Asia (Figure 2B–C). These introductions represent infections sampled in Alaska, Oregon, California, Wyoming and British Columbia, Canada that failed to disseminate widely and persisted for short periods of time (0.024 – 6.9 months). The western location of these tips suggest potential introduction via the Pacific flyway, consistent with previous reports documenting incursions into North America from Japan via Alaska and the upper Pacific (34)(Figure S6).

Figure 2. Introductions from Europe facilitated the majority of ongoing transmission while Asian introductions did not result in continent-wide onward transmission.

A) Bayesian phylogenetic reconstruction of n=1,921 globally sampled sequences of HPAI clade 2.3.4.4b colored by continent of isolation. Opacity of branches corresponds to posterior support for the discrete trait inferred for a given branch, the thickness corresponds to the number of descendent tips the given branch produces. B) A close-up view of the starred section of the tree in A, focusing on introductions from Asia. C) We inferred the number of transitions from Asia to North America across the posterior set of 9,000 trees. The x-axis represents the number of introductions, and the y-axis represents the proportion of trees across the posterior set with that number of inferred transitions.

Recent analyses of global H5N1 circulation patterns suggest wild birds as increasingly important reservoirs for clade 2.3.4.4b virus evolution and transmission (35). In the Americas, avian migratory routes are classified by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS) into 4 major flyways: the Atlantic, Mississippi, Central, and Pacific (36). If the epizootic were spread predominantly by wild, migratory birds, we reasoned that viruses sampled from the same, or neighboring flyways, should cluster together more closely than viruses sampled from non-adjacent flyways. To test this, we assigned avian sequences to the migratory flyway matching the US state of sampling, assembled a dataset of 250 sequences randomly subsampled for each USFWS flyway (total n=1,000), and implemented a discrete trait diffusion model to estimate transition rates between flyways, a proxy for transmission.

Tips that descend from viruses circulating in Asia (those in Figure 2B) cluster together as a basal clade inferred in the Pacific flyway (orange cluster at top of tree, posterior probability = 0.98), consistent with introduction into the West Coast. The primary introduction from Europe occurred via the Atlantic Flyway, and then spread rapidly across the US (Figure 3A,B). From the inferred time of introduction in the Atlantic flyway between September 9th – October 7th 2021, viruses descending from this introduction had disseminated and been sampled in every major flyway within ~4.8 months.

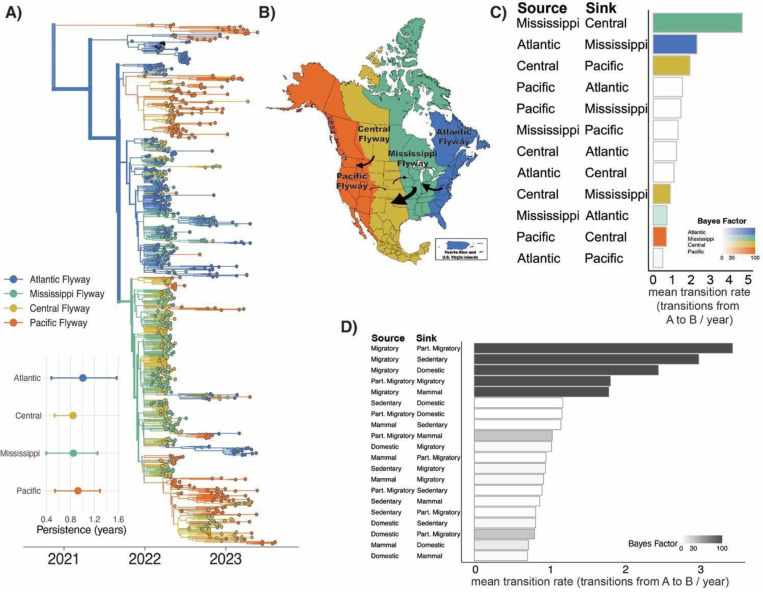

Figure 3. Migratory birds rapidly disseminated H5N1 via migratory flyways.

A) Phylogenetic reconstruction of n=1,000 sequences colored by continental flyway. Inset is the results of the PACT analysis for persistence in each flyway (how long a tip takes to leave its sampled location going backwards on the tree), excluding the Pacific clade to show persistence following Atlantic introduction. B) U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service waterfowl flyways map, with arrows annotated to represent rates with Bayes factor support of at least 100. Here the size of the arrow corresponds to the magnitude of the mean transition rate. C) Mean transition rates from the Bayesian Stochastic Search Variable Selection (BSSVS) of USFWS flyways where color of the bar corresponds to the source population and the opacity corresponds to the Bayes Factor (BF) support (where white corresponds to BF < 3 and full color corresponds to BF > 100). D) Mean transition rates from the BSSVS of migratory behavior of birds.

Sequences clustered strongly by flyway, grouping most closely with others sampled within the same or geographically adjacent flyway (Figure 3A). Transmission was most efficient between adjacent flyways, and primarily proceeded from east to west (Figure 3B–C, Table S1). We calculate the Bayes Factor (BF) support for each possible transition rate, which is calculated by dividing the posterior odds a transition rate is non-zero by the equivalent prior odds. Generally, BF > 30 are considered strong support, indicating that a given rate is 30x more likely to be included in the diffusion network, in this analysis we primarily focus on BF >= 100, or 100x more likely to be included (see Methods for details). We infer the highest supported rates (BF > 100) from the Mississippi to Central flyway (4.69 transitions/year, 95% HPD: (1.67,7.87), Atlantic to Mississippi flyway (2.3 transitions/year, 95% HPD: (0.74,4.08)), and Central to Pacific flyway (1.93 transitions/year, 95% HPD: (0.64,3.48))(Figure 3C, Table S1). Though the Pacific flyway experienced the highest number of introductions during the epizootic, transitions from the Pacific flyway elsewhere were inferred with low magnitude and weak support, and very little transmission occurred from west to east. Indeed, only a single statically supported rate was inferred from the Pacific flyway to the adjacent Central flyway (BF = 3, 0.69 transitions/year, 95% HPD: (0.004, 2.35)). Quantification of the length of times that lineages persisted in each flyway showed slightly longer persistence within the Atlantic and Pacific flyways, potentially due to the habitat and species richness in each flyway allowing for greater interaction of hosts (37). Previous work has shown that within-flyway transmission occurs far more rapidly than transmission between flyways, which may occur over longer time spans (> 5 years) (38–40). We speculate that the strong signal of east to west diffusion could be explained by rapid, exponential spread among naïve wild birds in North America during early panzootic expansion. Limited transmission from the Pacific flyway could also be explained by differential fitness of the lineages introduced into the Pacific vs. Atlantic flyways, ecological isolation of the Pacific flyway, or by differences in host distribution at the time of incursion. Future work will be necessary to differentiate among these hypotheses.

The strong clustering of sequences by flyways is consistent with long-range transmission by wild, migratory birds, but is not a direct measurement of it. To directly test this, we classified wild bird sequences by whether they were sampled from a wild bird considered migratory, partially migratory, or sedentary using the AVONET database (41). We then modeled discrete trait diffusion across 5 categories: wild migratory birds (includes most ducks and geese), wild partially migratory birds (some ducks, raptors, and vultures), wild sedentary birds (owls crows), domestic birds, and non-human mammals. Consistent with the flyways analysis, wild, migratory birds are inferred across the entire tree backbone with high statistical support, indicating that these birds played an important role in sustained transmission and geographic dissemination (Figure S7). Transitions from wild migratory birds were inferred with the highest number and most strongly supported rates (BF > 3000), indicating that migrating wild birds were critical to seeding infections in other species (Figure 3D, Table S2). Taken together, our results show that HPAI H5N1 viruses were repeatedly introduced into North America throughout the epizootic, with incursions into both the Atlantic and Pacific flyways. Following introduction into the Atlantic flyway, H5N1 viruses were rapidly disseminated from east to west by migrating wild birds. These results highlight the capacity of migratory birds to rapidly transmit these viruses across vast geographic areas in North America.

Epizootic transmission is sustained by canonical host species

Previous outbreaks of highly pathogenic H5N1 viruses have been facilitated by wild Anseriformes (waterfowl), wild Charadriiformes (shorebirds), and domestic Galliformes (42–45), though the role of these hosts varies across outbreaks. In the current panzootic, die-offs have occurred across non-canonical host orders like Accipitriformes (raptors, condors, vultures), Strigiformes (owls), and Passeriformes (sparrows, crows, robins, etc.) (9), raising the possibility that these new species could establish as reservoirs that merit surveillance. To determine whether particular host groups played outsized roles in driving transmission in the epizootic, we classified sequences by taxonomic orders that were most well-sampled and modeled transmission between them using a discrete trait model. We consolidated sequences of two orders of raptors, Accipitriformes and Falconiformes, hereafter referred to as “raptors”. We also consolidated two orders of pelagic birds, Charadriiformes and Pelecaniformes, hereafter referred to as “shorebirds”. Following classification, we defined 7 host order groups: Anseriformes, Shorebirds, Strigiformes, Passeriformes, Raptors, Galliformes, and non-human mammals.

Discrete trait approaches assume that the number of sequences in a dataset are representative of the underlying distribution of cases in an outbreak, resulting in faulty inference when this assumption is violated (23,33,46) and bias when groups are unevenly sampled (22,23). To account for differential sampling among these host groups, we therefore considered two, distinct subsampling approaches. The first is a proportional sampling regime in which sequences are sampled proportional to the detections in each host group each month. This common sampling regime assumes that case detections in each group are the closest proxy for the case distribution in the outbreak, and attempts to align sampling with underlying model assumptions. However, this approach may not be appropriate if case detection is heavily biased between groups. For HPAI H5N1 in North America, detections in wild birds are primarily identified when humans report sick or dead birds to wildlife health authorities or wildlife rescues (Figure S1A), which may skew detections towards birds with dedicated rescue services or birds that reside in closer proximity to humans. For example, Anseriformes and raptors comprised 50.2% and 20.3% of all sequences, respectively, which could arise from high case intensity or a higher rate of case acquisition. A second, complementary subsampling approach is to sample sequences equally, meaning that sequences are sampled from each group in perfectly equal numbers. By forcing the number of sequences from each group to be equal, the transmission inference must be driven by the underlying sequence diversity in each group rather than by sampling differences. Given the high variation among detections within each host group, we opted to pursue an equal sampling regime. We performed 3 independent subsamples, each comprised of a dataset of 100 randomly sampled sequences per host group. To account for variation across subsampled datasets, we combined the results for the 3 independent subsamples to summarize statistical support (Figure S9, Table S3–4). Due to similar tree topologies across replicates, we visualize the phylogeny of the subsample with the highest posterior support (equal order subsample 1) below and make the results of all subsamples available in supplement (see Figure S8, Table S5–S10).

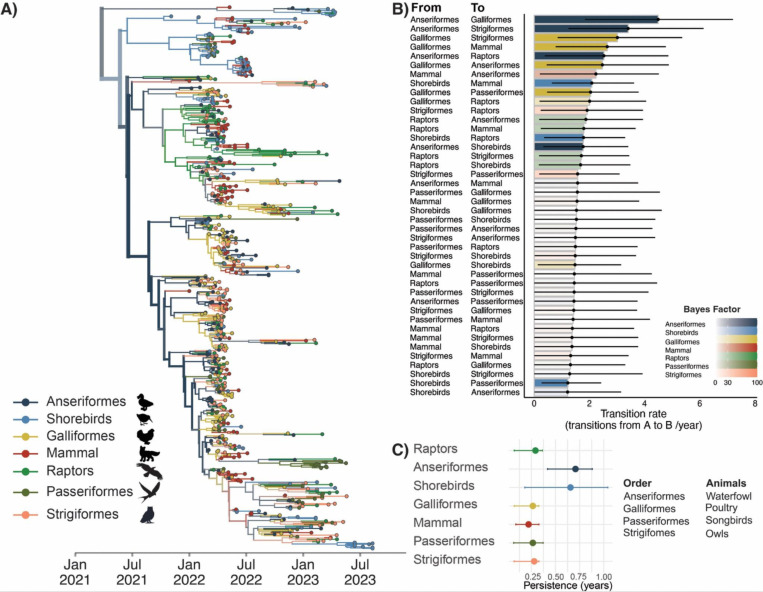

The first introduction into North America is comprised of infections sampled in great black-backed gulls (inferred as a large clade of shorebirds, posterior probability = 0.69), consistent with previous evidence of migratory gulls facilitating transmission from Europe (Figure 4A). This inferred-shorebirds cluster contains 6 sequences from harbor seals sampled from outbreaks in New England, resulting in a highly supported transition rate (BF = 537, posterior probability= 0.99) from shorebirds to non-human mammals (2.09 transitions/year, 95% HPD: (0.99, 4.63), aligning with suggestions that these outbreaks are linked to scavenging or environmental contamination by infected shore-birds (1,16). After this initial cluster of infections, the remainder of the phylogeny backbone is inferred in Anseriformes with high posterior support (0.99), indicating that Anseriformes played an important role in driving sustained transmission and dispersal across North America. We infer Anseriformes as the predominant hosts seeding infections into other species (Figure S10) (Figure 4B) (Table S5–10), with the highest rates to Galliformes (4.49 transitions/year (95% HPD: (1.84, 7.21), BF = 1691, posterior probability = 0.99) and Strigiformes (3.41 transitions/year (95% HPD: (1.24, 6.14), BF = 232, posterior probability = 0.99). Aligning with speculation following mortality events in bald eagles (47), we also infer a highly supported transition rate (BF = 127, posterior probability = 0.95) from Anseriformes to Raptors, consistent with putative links between raptors and the waterfowl they predate. These patterns were preserved in each independent subsample, indicating high robustness to sampling (Figure S8–9). We also infer support for transmission from Galliformes to Anseriformes (2.47 transitions/year (95% HPD: (0.45, 4.88), BF = 147, posterior probability = 0.96), Strigiformes, and nonhuman mammals. In this dataset, Galliformes primarily represent domesticated poultry (98% of sequences), suggesting that transmission from domestic birds back to wild birds and mammals may also have occurred, a hypothesis we investigate in more depth below. However, lineages in Galliformes tended to be short-lived, persisting for 0.26 years on average (95% HPD: 0.07, 0.33 years). In contrast, viral lineages persisted for the longest in Anseriformes, with a mean persistence time of 0.71 years (95% HPD: 0.42, 0.88 years) (Figure 4C), and Shorebirds, with a mean persistence time of 0.654 years (95% HPD: 0.18, 1.04 years). Therefore, while Anseriformes, Shorebirds, and Galliformes all contributed to transmission events to other species, longer-term persistence was primarily driven by transmission in Anseriformes and Shorebirds.

Figure 4. Anseriformes drove outbreak transmission, while new host species represent dead-end infections.

A) Bayesian phylogenetic reconstruction of n=655 sequences subsampled by host order with equal proportions of each host. The color of tips and branches represents taxonomic order, and opacity represents the posterior support for the inferred host group. Thickness of branches correspond to the number of tips descending from a given branch. B) Transition rates from the host group on the left (labelled “From”) to the host on the right (labelled “To”) as inferred from the combined results of three equal orders subsamples. The x location of the dot represents the inferred mean transition rate, and the black lines (whiskers) represent the 95% HPD. The color of each bar represents the “From” host. The opacity represents the Bayes factor support for the inclusion of the rate in the diffusion network. White (opacity of 0) represents any Bayes factors inferred to be less than 3, while a full color (opacity of 1) represents any Bayes factors inferred to be greater than or equal to 100. C) Results of the PACT analysis for persistence in each host order for phylogeny shown in panel A.

One surprising result was that we inferred raptors as a strongly supported source population to Anseriformes (1.87 transitions/year (95%HPD: (0.18, 3.94), BF = 39, posterior probability = 0.87). Previous characterizations of HPAI in Raptors during the 2014/2015 outbreak in North America showed mortality events and neurological symptoms in wild raptors (48). Serological evidence of infections in bald eagles have indicated exposure to influenza A viruses in 5% of birds tested between 2006 and 2010 (49). In the ongoing panzootic, raptors represent the third most prevalent group in wild bird detections in Europe (12% of detections) and second most detected group in North America (20.3%) (13,50). Future work to establish whether the high number of cases among raptors, and potential link to Anseriformes, is driven by efficient case detection vs. changing patterns of viral transmission will be necessary for formulating wildlife management strategies.

We found that Strigiformes (owls) exhibited primarily sink-like behavior with only two supported source transition rates to Passeriformes (BF= 82, posterior probability = 0.93), and Anseriformes (BF=61, posterior probability = 0.91). Surveillance efforts show evidence of transmission of HPAI in owls during previous outbreaks of HPAI globally and have typically been sampled alongside other bird species across several different host orders, primarily from the order Anseriformes (51–53). Overall, we found limited support for the non-canonical host groups songbirds and nonhuman mammals seeding infections in other species. Inference of transitions from these three host groups tended to be less supported and lower in magnitude, suggesting that these species did not play major roles in driving transmission across the continent or to other species (Figure 4B). Instead, these species tended to act as sinks, forming short, terminal transmission chains that did not lead to long-term persistence (Figure 4C and Figure S11). Similarly, mammals served as sinks for viral diversity, supporting very short persistence times of 0.22 years (95%HPD:(0.088, 0.328)), and resulting in only one strongly supported transition rate, to Anseriformes (BF = 53, posterior probability = 0.89). Finally, mammal sequences cluster across the entire diversity of the phylogeny (Figure 4A), and are not associated with one particular cluster of viruses, indicating that mammal infections were not confined to a particular viral lineage. Instead, these findings are most compatible with a model in which wild mammals are infected by direct interaction with wild birds, likely related to scavenging and predation behaviors (14).

Agricultural outbreaks were seeded by repeated introductions from wild birds

Since 2022, the US has culled over 104.4 million domestic birds with agricultural losses estimated between $2.5 to $3 billion USD (54). Understanding the degree to which outbreaks in agriculture have been driven by repeated introductions from wild birds vs. sustained transmission in agriculture is critical for improving surveillance and biosecurity practices. However, differences in sampling between wild and domestic birds challenge this goal. While domestic birds comprise 11% of all detections, they comprise 23.2% of sequences, making them overrepresented in available sequence data. In contrast, though a higher number of detections and sequences have been deposited for wild birds, wild birds are likely to be heavily under sampled due to the challenge of sampling wildlife (9,24). Finally, while each detection in wild birds represents a single infected animal, domestic bird detections usually represent a single infected farm, where the true number of infected animals is unknown. Given these challenges, we designed a “titration” analysis to measure the impact of varying degrees of sampling on transmission inference between wild and domestic birds. We first generated a dataset composed of equal numbers of domestic and wild bird sequences (using all 270 available domestic bird sequences and 270 randomly sampled wild bird sequences) sampled between November 2021 and August 2023. By setting the number of sequences from each group equal, we force the inference to be driven by the sequence data itself, rather than the sampling regime. Next, we added in progressively more wild bird sequences until we reached a final ratio of domestic to wild sequences equal to 1:3, which approximates the ratio of detections in domestic and wild birds during the epizootic (1026 domestic detections vs. 3078 wild detections for study time period). In total, we generated 5 datasets with the following ratios of domestic to wild bird sequences: 1:1, 1:1.5,1:2,1:2.5, and 1:3 (see Methods for more details). For each dataset, we applied a discrete trait diffusion model to infer transmission between wild and domestic birds.

When domestic/wild sequences were included in equal proportions, the backbone of the phylogeny and majority of internal nodes are inferred as wild birds, suggesting that wild birds are inferred as the primary source in the outbreak regardless of sampling (Figure S12A). Under equal sampling, this result is likely driven by higher genetic diversity among viruses sampled from wild birds, consistent with a large, source population. Within the background of wild bird sequences are multiple nested clusters of domestic bird sequences, consistent with some transmission between domestic birds. Transmission is inferred bi-directionally, with similar magnitudes of transmission inferred from domestic to wild birds, and from wild to domestic birds (Figure 5B, Figure S13, Table S11). If these patterns represent the true transmission history in the epizootic, we reasoned that these patterns should remain intact even when additional wild bird sequences are added to the tree. If not, then we hypothesized that some of domestic bird clusters may be disrupted as more wild bird sequences are added into the tree.

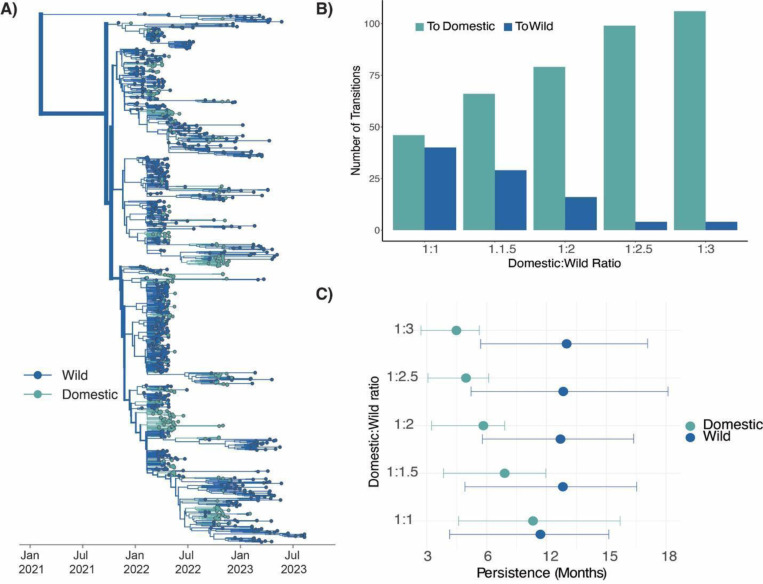

Figure 5. Outbreaks in domestic birds were seeded by repeated introductions from wild birds, with some onward transmission.

A) Phylogenetic reconstruction where taxa and branches colored by wild or domestic host status containing a 1:3 ratio of domestic to wild bird sequences (n=1080). B) Number of transitions from a given trait to another trait inferred through ancestral state reconstruction for each titration. C) Results of the PACT analysis for persistence in domestic and wild birds for each titration.

As wild sequences were progressively added into the tree, most domestic-only clusters became smaller, broken up by wild sequences that interspersed within these clades (Figure S12A–E). The “breaking up” of these domestic clusters results in inference of more transitions from wild to domestic birds, and less transmission between domestic birds (Figure 5B–C, Figure S13). The phylogeny of the final dataset (using a 1:3 ratio of domestic to wild sequences) shows 106 clusters of domestic sequences (Figure 5A, Figure S14–15, Table S11) each inferred as a unique introduction of H5N1 from wild birds into domestic birds. Among these domestic-only clusters, we calculate that lineages persisted for ~4.5 months on average (95% HPD: 2.7, 5.63). In contrast, we infer limited transmission from domestic birds back to wild birds (Figure 5B, Table S11), with only 4 inferred introductions from domestic birds to wild birds (Table S11). Viral lineages in wild birds also persisted for over twice as long as those in domestic birds, persisting for ~10 months (95% HPD: 5.7, 14.07) (Figure 5C).

Commercial turkey operations have been heavily impacted during the epizootic, comprising 53.7% of all detections on commercial farms (55). However, the presence of wild turkeys throughout North America makes categorizing turkey sequences as domestic or wild status ambiguous. 98% of all turkey sequences are not associated with metadata on domestic/wild status, and thus were excluded from the previous analysis. To determine whether this decision could have biased our results, we performed an additional analysis in which any turkey sequence not labeled as “wild turkey” was categorized as “domestic” and combined with the other domestic bird sequences. In this dataset, ~20% of domestic bird sequences were turkeys. We then created a second titration analysis using these domestic sequences to generate datasets of 1:1,1:1.5, and 1:2 ratios of domestic:wild sequences. We then evaluated the impact of the inclusion of turkey sequences on inferred transmission patterns between wild and domestic birds.

Inclusion of turkey sequences did not substantially change inferred transition rates between wild and domestic birds but did increase the inferred persistence times of domestic bird clusters (Figure S13, Table S11). As wild bird sequences were added to the tree, we observed the same “breakup” of domestic clades as in the above analysis, with more wild sequences leading to more inferred introductions into domestic birds, and very few into wild birds. In both titration experiments, the final number of inferred transmission events from domestic to wild birds was 4 (Table S11), indicating minimal transmission back to wild species, regardless of whether turkeys were included (Figure S16, Table S11). Inclusion of turkey sequences resulted in slightly longer inferred persistence times in domestic birds, increasing inferred persistence by 1.29 and 1.54 months in the 1:1.5 and 1:2 titrations (Figure S18). While turkey sequences tended to cluster closely with other domestic sequences, they did form several large turkey-only clusters on the tree (Figure S17), indicating some degree of separation between commercial turkey and non-turkey operations. To more directly estimate the role turkeys played in transmission we built a final 1:2 (domestic:wild) dataset where the number of turkey and domestic poultry where equal which conformed to both a uniform and case proportional dataset. Surprisingly, we found that while most introductions into turkey populations stemmed from wild birds (42 transitions), we infer a high number of transmission events between turkeys and other domestic birds. We estimate ~38 introductions from turkeys to other domestic birds, and 18 in the opposite direction (Figure S19, Table S12), indicating some degree of transmission between distinct poultry operation types. The high degree of transitions from wild birds to turkeys, and from turkeys to other domestic birds suggest a putative role for turkeys in mediating transmission between wild birds and other types of domestic poultry operations. In line with the high number of turkey detections during the epizootic, we infer comparatively larger clusters in turkeys than in other domestic birds, suggesting that turkeys may have played a key role in transmission among domestic populations.

Together, these data suggest a few important conclusions. First, wild birds are inferred strongly as the major drivers of transmission. Wild birds were inferred as the major source of viral dispersal regardless of sampling regime and independent of whether or not turkeys were included in the analysis, indicating strong support for their role in broad dissemination of H5N1. Second, regardless of sampling regime and presence/absence of turkey sequences, we infer that outbreaks in agricultural birds were driven by repeated, independent introductions from wild birds, with some onward transmission between domestic operations. While the exact number of inferred introductions vary across analyses (Table S11, S12), we infer no fewer than 46, and as many as 113 independent introductions into domestic birds. When allowing sampling frequencies to approximate detections (the 1:3 ratio analysis), we resolve a higher number of introductions into domestic birds with shorter transmission chains, though lineages still persisted for an estimated 4–6 months. Analysis of turkey and non-turkey data indicate some degree of transmission between agricultural operations, and a potential role for turkeys in mediating transmission between wild birds and non-turkey domestic birds. Together, these results indicate that while both the 2014/2015 epizootic and the 2022 epizootic involved transmission between domestic premises, that transmission since 2022 has been fundamentally distinct. While the epizootic of 2014/2015 was started by a small number of introductions that rapidly propagated between commercial operations, the epizootic since 2022 has been driven by intensive and persistent transmission among wild birds, resulting in continuous incursions into domestic bird populations that have continuously sparked new outbreaks in agriculture. These results suggest that wild birds may now play an increasing role in H5N1 transmission in North America, potentially necessitating updates to biosecurity, surveillance, and outbreak control.

Spillovers to backyard birds occur earlier and slightly more often than those to commercial birds

The 2014/2015 H5Nx epizootic in the United States was driven by extensive transmission in commercial poultry, prompting a series of biosecurity updates for commercial poultry farms (5,56). However, not all domestic birds are raised in commercial settings. Rearing domesticated poultry in the home setting has become increasingly popular in the United States, with an estimated 12 million Americans owning “backyard birds” in 2022 (57). These birds have been heavily impacted during the ongoing epizootic, with some evidence for distinct transmission chains circulating in backyard birds vs. commercial poultry (10). Because backyard birds generally experience less biosecurity than commercial birds and are more likely to be reared outdoors (27), we hypothesized that spillovers into backyard birds may be more frequent than spillovers directly into commercial poultry.

To test this hypothesis, we used a subset of sequences sampled between January and May of 2022 that contained additional metadata specifying whether they were collected from commercial poultry or from backyard birds (n= 275 from commercial poultry, n=85 from backyard birds). We then built a tree that included an approximately equal number of sequences sampled from domestic and wild birds, but in which the domestic sequences were evenly split between commercial poultry and backyard birds (commercial birds = 85, backyard bird = 85, wild birds=193). As with the previous analysis, we infer wild birds as the primary source population and infer repeated introductions into commercial and backyard birds (Figure S20A). Unexpectedly though, backyard bird sequences appeared to cluster more basally than commercial poultry sequences, and sometimes fell directly ancestral to clusters of commercial poultry sequences (Figure S20A). While every introduction into backyard birds was inferred to descend from wild birds, 10 out of 26 introductions into commercial poultry were inferred to descend from backyard birds (Figure S21A). This pattern was reproducible across multiple replicate subsamples, indicating that it was independent of the exact subset of wild bird sequences included in the tree. We developed two hypotheses that could explain this pattern. The first is that backyard birds “mediated” transmission between wild birds and commercial birds, possibly due to their greater likelihood of outdoor rearing. Under this model, spillovers into backyard birds could be spread to commercial populations via shared personnel, clothing, or equipment, resulting in sequences from backyard birds preferentially nesting between wild and commercial bird sequences on the tree. Alternatively, backyard birds could have simply been infected earlier on average than commercial birds. If transmission in wild birds is persistent and high, and backyard birds have a higher risk of exposure due to lessened biosecurity and increased interactions with wildlife, then it could take less time for a successful spillover event to occur and be detected in these birds, resulting in clustering that is more basal in the tree.

To differentiate between these hypotheses, we performed a second titration analysis. We started with the phylogeny including equal numbers of sequences from commercial and backyard birds, allowing us to directly compare introduction patterns in these two groups. Then, we added in progressively more wild bird sequences into the tree until all available wild bird sequences were added into the tree. We added sequences in increments of 25% (where % refers to percentage of total available wild bird sequences in the time period), resulting in 3 additional analyses that included 50%, 75%, and 100% of all available wild bird sequences. For example, the final dataset included 942 sequences, comprising 85 commercial bird, 85 backyard bird, and 772 wild bird sequences. For each dataset, we inferred the number and timings of transmission events between wild birds, commercial birds, and backyard birds across the posterior set of trees. If backyard birds acted as mediators to outbreaks in commercial birds (hypothesis 1), then the relationship between backyard birds and commercial birds should remain unchanged as more wild bird sequences are added into the tree. Alternatively, if backyard birds and commercial birds were infected independently (hypothesis 2), then additional wild bird sequences should disrupt these clusters, and intersperse between commercial and backyard bird sequences, resulting in more independent introductions that occur earlier in backyard birds.

Throughout the experiment, wild bird sequences attached throughout the phylogeny, disrupting nearly every backyard bird-commercial bird cluster, and dissolving the signal of backyard bird to commercial bird transmission originally observed (Figure S20). The final tree that included all available wild bird sequences resulted in inference of ~82 independent introductions from wild birds to domestic birds, with most clusters containing only commercial (39 clusters) or backyard bird (43 clusters) sequences (Figure 6A–B, Figure S20–21), suggesting that outbreaks in these groups were likely seeded independently. Indeed, of the initial 10 transmission events inferred from backyard birds to commercial birds, only 2 remained undisturbed in the final tree (Figure 6B, Figure S21). These two events represent outbreaks that occurred in the same state within 6 days of each other, so it is plausible that these outbreaks are directly linked. However, all other clusters were disrupted. As wild bird sequences were added into the tree, the number of inferred introductions into backyard birds and commercial birds diverged across the posterior trees for each titration (Figure S22), with backyard birds experiencing slightly more introductions (mean = 43 introductions, 95% HPD: (35, 49)) than commercial poultry (mean = 39 introductions, 95% HPD: (32, 44)) (Figure 6C). This is consistent with the rate of transmission inferred from wild birds into each domestic population with a slightly higher rate to backyard birds (1.83 transitions/year, 95% HPD: (0.282, 3.79), BF = 18,000, posterior probability = 0.99), then to commercial birds (1.6 transitions/year, 95% HPD: (0.23, 3.36), BF = 18,000, posterior probability = 0.99) (Table S13–S15). We infer a low transition rate from backyard birds to commercial birds (0.64 transitions/year (95% HPD: 3.1E-06, 2.05, BF = 4.58, posterior probability = 0.7), and transitions from domestic birds back to wild birds were not statistically well-supported.

Figure 6. Backyard birds are infected by wild birds earlier than commercial birds.

A) Phylogenetic reconstruction of sequences collected between Jan 2022 and May 2023 with all available wild bird sequences and equal proportions of commercial and backyard birds (n= 942) where taxa and branches are colored by host domesticity status. B) Exploded tree view of the phylogeny showing the branches of transmission in each domestic bird type following transmission from wild birds where subtrees represent the traversal of a tree from the root to the tip where the state is unchanged from the initial state (given by the large dot on left) to the tips represented by the smaller dots representing continuous chains of transmission within a given state. C) Proportion of trees from the posterior tree set with a given number of transitions from wild birds to backyard birds and commercial birds (100% available wild sequences). D) Markov rewards trunk proportion for domesticity status showing the waiting time for a given status across branches of the phylogeny over time. E) Cumulative Markov jumps from a given bird type to another over time where each line represents a single phylogeny from the posterior sample of trees.

To directly determine whether spillovers into backyard birds occurred earlier than those into commercial poultry, we estimated the number of transitions between hosts across the phylogeny (“Markov jumps”) and the amount of time that is spent in each host between transitions (“Markov rewards”) (58,59). We infer the highest mean duration in wild birds, representing 87.7% of Markov rewards. Backyard bird and commercial bird sequences showed lower, and similar reward time percentages of 5.3% and 7.0% respectively. Calculation of the Markov reward trunk proportion, a proxy for when transmission occurred in each group, showed that early in the epizootic, transmission in backyard birds preceded transmission in commercial poultry (Figure 6D, Figure S21). Enumeration of the cumulative number of transitions between hosts over time across the posterior set of trees (Markov jumps (59)), again revealed that backyard birds experienced slightly more jumps than commercial poultry (backyard birds = 43 introductions, 95% HPD: 36, 50; commercial birds = 39 introductions, 95% HPD: 32, 44), and that these introductions occurred earlier on average (Figure 6E). The lag time between the cumulative transitions for backyard birds and commercial birds was ~9.6 days, indicating that backyard birds may have been infected ~9 days earlier than commercial birds. Comparison of detections and sequence availability in commercial birds vs backyard birds show no apparent skewing in availability of samples for each group (Figure S23). Taken together, these data confirm that in the first 6 months of the epizootic, outbreaks in backyard bird and commercial bird populations were generally seeded independently, with limited evidence for transmission between them. Spillovers into backyard birds occurred slightly more frequently and about 9 days earlier on average than spillovers into commercial poultry, suggesting that backyard bird populations could potentially act as early warning signals for upticks in transmission. Given the increasing role of wild birds in H5N1 transmission, backyard birds could potentially act as useful sentinel species for gauging increasing transmission in wildlife and increased risk of spillovers into agriculture. Future work will be necessary to investigate the utility of this hypothesis.

Discussion

The 2022 panzootic of HPAI H5N1 has impacted wildlife health, agriculture, and human pandemic risk across the Americas. This panzootic has been distinguished by the high number of infections in wildlife not usually impacted by HPAI, its rapid dissemination across the Americas, and for its persistence despite aggressive culling of domestic birds. In this study, we used a dataset of 1,818 HA sequences paired with curated metadata to reconstruct how H5N1 viruses were introduced and spread throughout North America. We show that H5N1 viruses were introduced ~8 independent times into North America, with repeated incursions into the Pacific flyway that failed to disseminate. A single introduction into the Atlantic flyway spread across the continent within ~4.8 months, transmitting from east to west by wild, migratory birds. Long-range dispersal and persistence were primarily driven by transmission in Anseriforme species, with infections in wild birds like songbirds and owls primarily serving as dead-end hosts. Finally, we show through repeated subsampling experiments that unlike the epizootic of 2014/2015, outbreaks in agriculture were driven by repeated, independent introductions by wild birds, with some onward transmission. Backyard birds experienced slightly more introductions than commercial poultry, and these introductions occurred ~9 days earlier on average. Taken together, our results highlight continuous genomic surveillance in wildlife as critical for accurate outbreak reconstruction, and suggest wild, migratory birds as emerging reservoirs for highly pathogenic H5N1 viruses in North America. Our findings implicate surveillance in these wild, aquatic species as critical for ongoing tracking and response, and suggest that preventing future outbreaks in agriculture may now require layered interventions beyond culling.

We infer that most epizootic transmission descends from a single introduction into the Atlantic flyway in the fall of 2021 (September-October), in line with work describing the first confirmed detections on an exhibition farm in Newfoundland and Labrador Canada (6) and prior work that identified introductions into North America from Europe and Asia (7,60). Though H5N1 was first confirmed in captive birds in early December (December 9, 2021), retrospective testing revealed infection in a great black-backed gull from a nearby pond on November 26, 2021, confirming circulation in wild birds prior to detection on the farm (6). Our analyses suggest that highly pathogenic H5N1 viruses may have been circulating in wild birds in North America as early as September – October of 2021, one to two months prior to the first reported detection. Detailed analysis of species-specific migration patterns have been used to suggest that H5N1 may have been introduced in the autumn migration (6), a hypothesis supported by our data. Clade 2.3.4.4b viruses cause varying degrees of symptoms across avian species, so circulation in birds that experience milder symptoms could have obscured early detection and allowed for some degree of cryptic transmission (61). Species such as herring gulls show obvious neurological deficits such as paralysis, while other species such as Eurasian teals show no detectable clinical signs (11,62). Following introduction into the Atlantic flyway, we estimate that H5N1 viruses were transmitted from east to west, spreading from coast to coast in ~4.8 months. Compared to other avian-transmitted viruses, this is quite rapid. For example, West Nile Virus spread from the Northeast across the continent over the course of 4 years (63). We speculate that the relative rapidity of geographic spread could be explained by one or a combination of the following factors: high inherent transmissibility of clade 2.3.4.4b viruses in wild birds; rapid, long-range migration of wild bird species driving transmission; and rapid expansion across an immunologically naïve population in North America (61). Though limited work has been published on seroprevalence in wild birds, exposure to the current clade 2.3.4.4b viruses in North American wildlife was likely extremely limited prior to 2022 (64), potentially allowing for rapid, exponential growth following a successful incursion. Future work to examine the impacts of prior exposure to endemic, low-pathogenicity H5 viruses to susceptibility to clade 2.3.4.4b viruses may provide insights into future patterns of spread. Continuous surveillance among wild birds will also inform whether the rapid degree of transmission observed early in the panzootic will lessen over time as immunity builds in avian species.

Though a single introduction into the Atlantic flyway accounted for most transmission in the epizootic, the Pacific flyway experienced more independent incursions (~7), and it remains unclear why these failed to disseminate onward. Compared to other studies, we infer more incursions (5 more than previous estimates) into the Pacific flyway, likely due to the higher number of sequences from the Pacific region included in our analysis (65). Early after introduction, the European lineage introduced into the Atlantic flyway reassorted with endemic, low-pathogenicity H5 viruses in North America, resulting in a virus that exhibited altered tissue tropism in mammals (66). Whether this early reassortment event, or subsequent reassortments, also resulted in viruses with enhanced fitness in wild birds is currently unknown, but could explain the success of the Atlantic flyway introduction. Alternatively, the failure of Pacific incursions to spread onward could be explained by ecological isolation of the Pacific flyway, potentially due to land features like the Rocky Mountains. Prior studies of low-pathogenicity avian influenza have shown limited transmission between flyways and strong influence of geography on the restriction of virus dispersal across the North American continent (67–69). In line with this hypothesis, we infer very minimal transmission occurring out of the Pacific flyway, even when inference was performed with an equal number of sequences per flyway. Finally, Pacific flyway introductions could have failed to disseminate due to a lack of suitable host species at the times and locations of the incursions, or simply by chance. Future work that examines the relative fitness of reassortants in wild birds, and that incorporates migratory movement data with the distribution of suitable species across time and space, will likely be necessary to distinguish between these hypotheses.

Our work demonstrates the impact of migratory bird movement on the rapid spread across the North American continent. In North America, transmission was most efficient between neighboring flyways, suggesting strong dissemination through geographic space that correlates to flyway areas. Prior work mapping migratory movements of Anseriformes (specifically, Mallards, Northern pintails, American Green-winged Teals, and Canada geese) showed that these birds exhibited North-South migratory pathways with some overlap between flyways (38,70). Future work to characterize the impact of migration in the western hemisphere is critically important as the range of many migratory birds encompasses several regions which are poorly sampled such as the Caribbean, Central America, and the Amazon basin. Follow-up studies to link finer-scale movement of wild birds to avian influenza transmission pathways may improve resolution of geographic spread and risk modeling, particularly for agricultural areas. Portions of the Atlantic and Mississippi flyways encompass high-density production areas for broiler chickens and turkeys, collectively producing nearly 7.32 billion broiler chickens and 182.2 million turkeys in the US annually (71), areas that have been heavily impacted by the panzootic. Our analysis of viral persistence times showed that viral lineages persisted for the shortest periods of time in the Mississippi and Central flyways and in Galliformes. Combined with our analyses showing that most agricultural outbreaks were driven by repeated introductions from wild birds, these findings suggest that infections in these domestic populations were generally transient. Our data suggest future work to track the movement of highly pathogenic H5 viruses across annual migratory cycles in wild birds as critical for pinpointing time periods that pose the greatest risk for spillover into agricultural settings. Successfully integrating migration timings of major species of Anseriformes, such as mallards, into risk models could allow biosecurity updates to be proactively deployed at times of year predicted to be critical based on time and geography (72,73).

Despite widespread infections in non-canonical avian species, we show that long-range, persistent transmission in this epizootic was driven by classical hosts for avian influenza: Anseriformes. Recent modeling of HPAI risk in Europe identified Anatinae and Anserinae (within the order Anseriformes) species prevalence as the most consistent predictors of HPAI detection across seasons (74), and future work will be necessary to determine whether those patterns hold in the Americas. Anseriformes and Shorebirds are primarily thought to inhabit wetland and shore habitats respectively but have been observed co-mingling in human-made habitats, like urban environments and waste disposal sites (75,76). We observe supported source transmission patterns from raptors, birds which have previously shown susceptibility to clade 2.3.4.4 viruses and exposure to avian influenza viruses more generally (48,49). The severity and exposure risk in bird species in North America may also impacted by LPAI circulation which has been consistent and widespread for decades (75,77,78). The co-circulation of HPAI and LPAI in canonical host species can lead to novel reassortants which increase the pathogenicity of the virus. While this study focused on hemagglutinin sequences, future analysis should also include other gene segments and in particular focus on the reassortment of the virus between different NA subtypes as well as with LPAI viruses. The role of reassortment in the greater North American outbreak is still understudied and could provide important insights into transmission dynamics across different species.

In this study, we find that outbreaks in agriculture were seeded by repeated introductions from wild birds. This pattern held true regardless of sampling regime, and aligns with anecdotal observations that clade 2.3.4.4b viruses are increasingly being maintained by transmission among wild bird species, including now in North America (35,79). These findings contrast with genomic and epidemiologic investigation of the epizootic in 2014/2015, which implicated transmission between commercial poultry operations as the major source of dissemination (5,80). During that epizootic, transmission between farms was putatively linked to virus movement via personnel, equipment, and clothing, prompting updates to recommended biosecurity protocols for large, commercial operations (5,56). That epizootic was also well-controlled by culling domestic flocks, and after culling 50.5 million domestic birds, the epizootic died out. In contrast, at the time of writing, detections in wild and domestic birds in North America have continued despite culling nearly 104.4 million domestic birds. We show that despite some persistence among domestic bird populations, that introductions into domestic populations ultimately led to transmission chains that died out, and that they generally did not result in re-introduction into wild birds. Though detailed epidemiologic analyses are necessary to pinpoint the precise series of events that led to these outbreaks, our data imply that transmission in agricultural settings was fundamentally distinct from past outbreaks. Multiple, independent analyses suggest that transmission was efficient and persistent in wild birds, leading to repeated spillovers into agriculture. Taken together, our findings implicate wild birds as an emerging reservoir for highly pathogenic H5N1 viruses in North America. Continuous transmission in wild birds suggests a plausible explanation for rapid cross-continental spread, and for the lack of control in agriculture despite aggressive culling. In combination with other studies, our data suggest that future prevention of agricultural outbreaks may now require layered interventions that seek to reduce interactions between wild and domestic birds, paired with aggressive biosecurity between farms (18,81). Continuous reseeding from wild birds may also reduce the effectiveness of culling as the primary strategy for control. As highly pathogenic H5N1 viruses continue to circulate in North American wild birds, investment in control methods that reduce successful transmission between wild birds and agricultural animals, including potentially vaccination, should be explored.

We find that spillovers into backyard birds occurred slightly earlier and more frequently than those into commercial farms. Though commercial poultry operations generally operate with higher degrees of biosecurity than backyard flocks, there are some documented locations that could allow for interaction between domestic birds and wildlife (27). Retention ponds on commercial poultry farms are frequently visited by wild waterfowl (82), while natural features such as water bodies and vegetation near residential coops and commercial production sites could also act as potential points of wild to domestic transmission. Though recent data on backyard bird rearing in the US is limited, a large survey of backyard bird populations from 2004 showed that backyard bird flocks often contain multiple species, usually have outdoor access, and that 60–75% of backyard flocks experience regular contact with wild birds (27). 38% of surveyed backyard flocks were on a property that contained a pond that attracted wild waterfowl, providing a clear, plausible link to water bird interaction. The same survey showed that biosecurity precautions tend to be much more limited in backyard bird populations, with 88% of backyard flocks using no precautions (shoe covers, footbaths, clothing changes) at all (27). Analysis of seropositivity to avian influenza in backyard poultry in Maryland showed that exposure to waterfowl resulted in a ~3x higher likelihood of harboring anti-influenza antibodies compared to birds not exposed to waterfowl (83). Early infections during the 2014/2015 epizootic were recorded in backyard birds (84), and backyard birds have been heavily impacted during this epizootic. Because backyard birds are typically reared for egg and meat consumption, infections in backyard birds could also pose a risk for human exposure. Putative links between infected locally reared birds and human infections have been made in Mali and Egypt where backyard flocks are common, serving as an indicator for the potential for exposure to occur in North America (85,86). Given backyard birds’ enhanced likelihood of interaction with wild birds, and our inference of earlier spillovers in those groups, backyard bird populations could be investigated as early warning sentinels for increasing transmission in local wild bird populations. 93% of backyard flocks contain <100 birds, and most backyard bird owners report raising birds for enjoyment and eggs (27). A subset of backyard bird owners may therefore present an opportunity for community engagement that could potentially help identify early detections. If engagement were successful, prompt reporting for illness and infections could be used to alert other nearby operations that highly pathogenic avian influenza is circulating locally, allowing for more advanced warning for heightened biosecurity.

Sampling bias is pervasive across viral outbreak datasets, and no modeling approach can completely overcome inherent biases in data acquisition. In this study, we opted to explore multiple sampling regimes and pair them with experiments to directly assess the impacts of sampling on our results. By combining case proportional subsampling and equal sampling regimes with titration experiments, we attempt to evaluate the biases between case detection and sequence availability that exist in these data, and to report conclusions that were robust to these biases. Even so, an important caveat of our work is that our inferences are limited by the availability of sequence data, and results could change if future data become available. Our results also highlight the necessity of consistent surveillance data from wildlife species. The inferences we make in this study rely on intensive sampling of wild birds from the same time period as agricultural outbreaks. Accurately distinguishing between hypotheses of epizootic spread (e.g., whether agricultural outbreaks are driven by introductions from wild birds or by from farm-to-farm spread) depends on adequate sequence data from wild birds, without which transmission inference is impossible. In our examination of avian host groups, fine-scale analysis of individual species was limited by data availability, necessitating grouping birds into higher level taxonomic orders. As H5N1 viruses continue to evolve and spread globally, investment in surveillance strategies that capture circulating diversity among wild birds will likely be critical for accurately tracking viral evolution, prioritizing vaccine strains, and contextualizing new emergence events, like the recent outbreaks in dairy cattle.

The H5N1 panzootic of 2022 has severely impacted wildlife ecology, agriculture, and human pandemic risk across the Americas. Developing and deploying successful interventions requires disentangling how these viruses spread across the Americas and spilled into new species. Our findings point to wild, migratory birds as emerging reservoirs for highly pathogenic H5N1 viruses in North America, a fundamental shift in ecology with implications for biosecurity and pandemic risk mitigation. Our results highlight the utility of wild bird surveillance for accurately distinguishing hypotheses of epizootic spread, and suggest continuous surveillance as critical for preventing and dissecting future outbreaks. Our data underscore that continued establishment of H5N1 in North American wildlife may now necessitate a shift in risk management and mitigation, with interventions focused on reducing risk within the context of endemic circulation in wild birds. At the time of writing, outbreaks in dairy cattle highlight the critical importance of modeling the ecological interactions within and between wild birds and domestic production. Future work to effectively model viral evolution and spread hinges critically on effective surveillance across wild and domestic species to capture key transmission pathways across large geographic scales. Ultimately, these data are essential for informing biosecurity, outbreak response, and vaccine strain selection.

Materials and Methods

Dataset collection and processing

Genomic data processing and initial phylogenetics

We downloaded all available nucleotide sequence data and associated meta-data for the Hemagglutinin protein of all HPAI clade 2.3.4.4b H5Nx viruses from the GISAID database on 2023-11-25 (87). For each subset of the data described for further phylodynamic modeling the following process was followed. We first aligned sequences using MAFFT v7.5.20, sequence alignments were visually inspected using Geneious and sequences causing significant gaps were removed and nucleotides before the start codon and after the stop codon were removed (88,89). We de-duplicated identical sequences collected on the same day (retaining identical sequences that occurred on different days). We identified and removed temporal outliers for all genomic datasets by performing initial phylogenetic reconstruction in a maximum likelihood framework using IQtree v.1.6.12 and used the program TimeTree v 0.11.2 was used to remove temporal outliers and to assess the clockliness of the dataset prior to Bayesian phylogenetic reconstruction (90,91). This resulted in a dataset of 1818 sequences that were used in further analyses (Figure S24).

AVONET database

We downloaded the AVONET database for avian ecology data and merged it to available host metadata from GISAID for each sequence (41). We used the species if provided to match the species indicated in the AVONET database. If host metadata in GISAID was defined using common name for a bird, we determined the taxonomic species name and used that for further merging with the AVONET data (e.g. “Mallard” was replaced with Anas platyrhynchos) for the given region to match the species to its respective ecological data. We additionally determined the domesticity status of a given using the metadata provided.

Detections by USDA

Data for detections of HPAI in North America were collected from USDA APHIS. Reports for mammals, wild birds, and domestic poultry were all downloaded (download date: 2023-11-25) (50).

Phylodynamic analysis

The following Bayesian phylogenetic reconstructions and analyses were performed using BEAST v.1.10.4 (92).

Empirical tree set estimation and coalescent analysis.

We performed Bayesian phylogenetic reconstruction for each dataset prior to discrete trait diffusion modeling to estimate a posterior set of empirical trees. The following priors and settings were used for each subset of the sequence data. We used the HKY nucleotide substitution model with gamma-distributed rate variation among sites and lognormal relaxed molecular clock model (93,94). The Bayesian SkyGrid coalescent was used with the number of grid points corresponding to the number of weeks between the earliest and latest collected sample (e.g for a dataset collected between 2021-11-04 and 2023-08-11 we would set 92 grid points) (95). We initially ran four independent MCMC chains with a chain-length of 100 million states logging every 10000 states. We diagnosed the combined results of the independent runs diagnosed Tracer v1.7.2. to ensure adequate ESS (ESS > 200) and reasonable estimates for parameters (92). If ESS was inadequate additional independent MCMC runs were run increasing chain length to 150 million states, sampling every 15000 states were performed. We combined the tree files from each independent MCMC run removing 10–30% burn-in and resampling to get a tree file with between 9000 and 10000 posterior trees using Logcombiner v1.10.4. A posterior sample of 500 trees was extracted and used as empirical tree sets in discrete trait diffusion modeling.

Discrete trait diffusion analysis

Dataset subsampling and definition of discrete traits

We characterized the geographic introduction of HPAI into North America by randomly sampling 100 sequences from Europe and Asia for each year between 2021–2023 (total 300 non-North American) and all available North American sequences across the study period. Following removal of temporal outliers this resulted in a dataset of n= 1921 sequences annotated by continent of origin.

To characterize geographic transmission within North America, following introduction, we constructed a dataset of sequences subsampled based on migratory flyway. We used place of isolation data to match the US state or Canadian province the sequence was collected from with the respective U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Migratory Bird Program Administrative Flyway (36). We subsampled 250 sequences for each flyway (Atlantic, Mississippi, Central, and Pacific) to create a dataset of 1000 sequences collected between November 2021 and August 2023.

We classified sequences by host taxonomic order, inferring the host species using designations in the strain name and/or metadata to match species records in AVONET (41). To ensure that each discrete trait had an adequate number of samples for the discrete trait analysis of host orders we combined orders in two instances based on taxonomic and behavioral similarity. The order Falconiformes (n=14), which represents falcons, was added to Accipitriformes (n=363), which includes other raptors such as eagles, hawks, and vultures. Pelecaniformes (n=34) which includes pelicans were grouped with Charadriiformes (n = 74, shorebirds and waders) due to their similar aquatic lifestyles and behaviors. Mammals were kept as a broad non-human classification as most samples were of the order carnivora (foxes, skunks, bobcats etc.), apart from samples of dolphins (Artiodactyla) and Virginia opossum (Didelphimorphia). The following orders were omitted due to low number of sequences: Rheaforimes (n=2), Casuariiformes (n=1), Apodiformes (n=2), Suliformes (n=7), Gaviiformes (n=1), Gruiformes (n=1), Podicipediformes (n=1).

We randomly subsampled 100 sequences for each host order between 2021-11-04 and 2023-08-11 resulting in a dataset of n=655 sequences where all isolates for host orders with less than 100 samples, Passeriformes (n = 57) and Strigiformes (n=99) (removing one temporal outlier), were used (Figure S25). We repeated this random subsampling three times resulting in three separate datasets. We additionally performed three sub-samples of sequences based on the proportion of detections in each host order group which were collected between 2021-11-04 and 2023-08-11. Three random proportional samples were taken each with the following number of sequences for each group: Accipitriformes =133, Anseriformes = 342, Passeriformes = 12, Nonhuman-mammal = 16, Galliformes = 83, Charadriiformes = 40, Strigiformes = 29 (total n=655 sequences).

We defined discrete traits for use in discrete trait diffusion modeling based on the available sequence metadata and merged AVONET data. In addition to taxonomic order, we defined migratory behavior. Birds were classified as sedentary (staying in each location and not showing any major migration behavior), Partially migratory (e.g. small proportion of population migrates long distances, or population undergoes short-distance migration, nomadic movements, distinct altitudinal migration, etc.), or Migratory (majority of population undertakes long-distance migration).

Discrete trait modeling framework