ABSTRACT

Background:

The most prevalent endocrine disorder affecting women is PCOS. Programmed death of ovarian cells has yet to be elucidated. Ferroptosis is a kind of iron-dependent necrosis featured by significantly Fe+2-dependent lipid peroxidation. The ongoing study aimed to reinforce fertility by combining therapy with AgNPs and (Zileuton) in PCOS rats’ model.

Methods:

The study included 75 adult female rats divided into 5 groups; control, PCOS, PCOS treated with AgNPs, PCOS treated with Zileuton, and PCOS group treated with AgNPs and Zileuton. The study investigated the anti-ferroptotic, anti-inflammatory, antioxidant, antiapoptotic, histopathological and immunohistochemical examinations of COX-2 and VEGF.

Results:

The combination of AgNPs and Zileuton showed significant reduction of inflammatory mediators (IL-6, TNF-α, NFk-B) compared with diseased group (P-value < 0.05), regression of ferroptosis marks (Panx1 and TLR4 expression, Fe+2 levels) compared with diseased group (P-value < 0.05), depression of apoptotic marker caspase 3 level compared with diseased animals (P-value < 0.05), depression of MDA level, elevation of HO-1, GPx4 activity, and reduction of Cox2 and VEGF as compared with the diseased, AgNPs or zileuton-treated groups (P-value < 0.05).

Conclusion:

The study showed that the combination of AgNPs and zileuton guards against, inflammation, apoptosis, and ferroptosis in PCO.

KEYWORDS: Ferroptosis, Panx1, TLR4, COX-2, VEGF, AgNPs, Zileuton, PCOS

Introduction

Polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS) is a significant global health concern, it is one of the most popular hormonal disorders that impact females in the reproductive years. Polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS) is a complex condition that encompasses a variety of disorders marked by reproductive, metabolic, and psychological symptoms. Common manifestations include hirsutism, acne, irregular menstrual cycles, and infertility. Although the precise etiology of this multifactorial condition remains unclear, its growth is thought to be greatly influenced by a confluence of environmental factors and genetic predispositions. Insulin resistance, hyperandrogenism, and persistent low-grade inflammation are the main pathophysiological factors that lead to PCOS. These factors hinder the process of follicular-genesis and increase the likelihood of related comorbidities [1].

Ferroptosis is a common type of non-apoptotic cell death that is implicated in many degenerative diseases. Lipid peroxidation, a process that increases reactive oxygen species (ROS) in cells, depends on iron [2]. Recent research has shown substantial evidence that ferroptosis is important for understanding the pathophysiology of several diseases, such as cancer, viral and inflammatory illnesses, and neurological disorders [3].

PCOS-related ovarian dysfunction has been proven to imply exaggerated programmed cell death particularly ferroptosis [4]. Lipoxygenases (LOX) are vital enzymes that help polyunsaturated fatty acyl groups get oxygenated so that lipid hydroperoxides can be formed. The Fe2+-containing enzyme 5-lipoxygenase (5-LO) facilitates both the peroxidation of polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFAs) and the metabolism of arachidonic acid, which is present mainly in cell membranes. Lipid peroxidation and the development of ferroptosis may result from such a mechanism [5].

Lipid and hydrogen peroxides, on the other hand, must be reduced by members of the glutathione peroxidase (GPX) family. As the sole enzyme capable of directly reducing the lipid hydroperoxides found in biological membranes, GPX4 is essential for preserving the redox balance of the cell membrane [6].

The FDA approved zileuton to treat and prevent chronic asthma in people 12 years of age and older. As a 5-lipoxygenase inhibitor, Zileuton prevents the synthesis of leukotrienes B4, C4, D4, and E4 [7]. Recent studies have demonstrated that Zileuton significantly alleviates ferroptosis, along with the associated oxidative and inflammatory conditions [8].

Among other nanoparticle kinds, silver nanoparticles (AgNPs) have been identified for their antibacterial, antifungal, and immunomodulatory characteristics [9]. AgNPs produced from plants that have immunomodulatory and/or antibacterial properties may be used to treat chronic inflammation or diseases that are resistant to antibiotics. Because of its inhibitory effect on pro-inflammatory cytokines synthesis including TNF-α, IL-6, and IL-1β, AgNPs can lessen inflammation brought on by lipopolysaccharide (LPS). Nanoparticles are better at blocking pro-inflammatory cytokines and enzymes that produce inflammation because of their increased surface area-to-volume ratio [10].

Thus, our study’s goal is to explore the cytoprotective effect of AgNPs and Zileuton alone and compare it with their combination, looking for any potential synergistic effects of Zileuton and AgNPs regimen in mitigating PCOS underlying ferroptosis and inflammation.

Material and methods

The Tanta University Faculty of Medicine’s Ethical Committee granted authorization for the study to be conducted (Approval Code Number: 36264PR252/6/23).

Drug and chemicals

− Sigma Pharmaceutical Company supplied carboxymethyl cellulose (CMC) and metformin (MET) in Egypt, whereas Natco Pharma Limited in Hyderabad, India was the source of letrozole.

− Silver nanoparticles, or AgNPs, are measured at 5.0, 1.25, and 0.156 ug/ml and have a particle size of 10 nm (TEM). They are also concentrated at 0.02 mg/ml in aqueous buffer. Sodium citrate is a stabilizing agent (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA, 730785).

− Zileuton was brought from the United States, in St. Louis, Missouri, at Sigma-Aldrich.

− High fat diet (HFD) constituents were purchased from El-Gomhoria Company, Cairo, Egypt and were preserved at 4°C until used.

Experimental animals

This study included 75 adults female Wistar albino rats; their weight ranged from (190 to 200) g. All the animals were allowed to adapt for four days before the experiment. Animals were housed in appropriate cages in the animal house and maintained on a normal laboratory diet, according to both the institutional and national guidelines. Three rats per cage was the maximum number allowed in order to prevent dirty or overcrowded cages. Rats were checked for illness symptoms and cage aggressiveness five times a week. Every technique was carried out in accordance with Tanta University’s ethics committee (Approval Code Number: 36264PR252/6/23).

Experimental design

Rats were categorized into two distinct groups

Group C (n = 15): The rats in this group were fed a normal diet with 3.8 kcal/g, which included 63.4% carbs, 25.6% proteins, and 11.0% fats.

Group on a High-Fat Diet (n = 60): For six weeks, this group was fed a high-fat diet (HFD) consisting of 59.0% fats, 14.9% proteins, and 25.9% carbs with an energy density of 5.4 kcal/g. With a few adjustments, the nutritional content (g/kg diet) was derived from the formulation by Kim et al. [11].

The rats’ body weight and nasal length were measured every week, and their Lee obesity index, which is computed as (3 × √body weight (g) / naso-anal length (cm) × 1000), was also recorded [12].

Letrozole was given via gavage for 21 days straight beginning on day 22 of the HFD at a dose of 1 mg/kg/day dissolved in a 0.5% CMC solution in order to create a PCOS-IR model [13]. Through oral gavage, the control group was given an equal amount of 0.5% CMC. An effective induction of PCOS was confirmed by microscopically examining vaginal smears.

The PCOS-IR rats were split up into four groups, with 15 rats in each.

PCO model group.

PCO treated with AgNPs: For 15 days, PCO animals received a dosage of 50 mg/kg/dose of AgNPs [14].

PCO treated with Zileuton: For 15 days, PCO animals received an oral dosage of 5 mg/kg twice a day of zileuton [15].

PCO treated with AgNPs + Zileuton: For 15 days, animals received an oral dosage of 50 mg/kg of AgNPs and a twice-daily dose of 5 mg/kg of zileuton.

Blood sample and biochemical assessment of lipid profile, hormonal state

Following an overnight fast and day 42 of the high-fat diet, blood samples were taken from the PCOS rats’ tails, and fasting insulin and blood glucose levels were recorded. Calculations were made using the Homeostasis Assessment Model of Insulin Resistance (HOMAIR). Rats bearing HOMA-IR > 2.8 were chosen as PCOS-IR model rats.

The rats were weighed, given an intraperitoneal injection of pentobarbital at a dose of 50 mg/kg to induce anesthesia, killed by cervical dislocation, and blood samples were collected [16]. Following 10-minute centrifugation at 3000 rpm, the serum was separated and transferred into sterile storage tubes for the purpose of measuring the following parameters: total lipid profile by calorimetry (Biodiagnostic, Egypt); insulin (Cat No. ab63820); oestradiol (Cat No. ab108667); progesterone (Cat No. ab108670); FSH (Cat No. CSB-E06869r); LH (Cat No. CSB-E12654r); testosterone (Cat No. ab108666) were assessed using ELISA kit.

Ovarian tissue preparation

After decapitation, abdomens were opened; ovarian tissues were extracted. Ovarian tissues were split into three sections at random. 1st section underwent homogenization and was designated for biochemical parameters examination. The 2nd ovarian section was designated for the real-time study of gene expression. Finally, the 3rd section was designated for histopathological and immunohistopathological studies.

Biochemical analysis of inflammation, apoptosis and OS

After undergoing anesthesia, ovarian tissue samples from rats were obtained, homogenized in cold phosphate-buffered saline (pH 7.4), and centrifuged at 3000 rpm for 10 minutes. The supernatant was separated into individual clean plastic tubes and kept at −80°C, as directed by the manufacturer. Then, it was used for the immunoassay detection of the following indicators of inflammation and apoptosis: IL-6 level (Cat# No. MBS269892), TNF-α (tumor necrosis factor α) (Cat# No. MBS355371), nuclear factor kappa beta (NFk-B) level (Cat# No. MBS287521), and caspase 3 activity (Cat# No ab39401).

Additionally, OS indicators were assessed using the approach outlined by Ohkawa et al. [17] for malondialdehyde (MDA) levels and a commercial colorimetric kit obtained from Biodiagnostic Co., Giza, Egypt, for Gpx4 activity was used.

Biochemical evaluation of ferroptosis

Ovarian Fe 2+: Using a commercial iron assay kit (Abcam, Japan, cat# no. ab83366), the quantity of ovarian Fe 2 + was measured calorimetrically in compliance with the manufacturer’s instructions. Ten milligrams of ovarian tissue were centrifuged in cold PBS, homogenized in iron assay buffer, and the tissue was cleaned by utilizing the supernatant for examination. We utilized 96-well microplates to hold the standards and samples. For every standard or sample, 5 μl of reducing solution or iron buffer was applied in turn. Dish is mixed, then cooked for 30 minutes at 37 °C. The absorbance was measured at 593 nm using a microplate reader after each well was filled with 100 μl of iron probe, mixed, and incubated for 60 minutes at 37°C.

Determination of ovarian heme oxygenase-1 (HO-1) activity

Schenkman and Cinti’s approach [18] was used to isolate ovarian microsomes. Subsequently, they were employed to quantify microsomal HO activity, utilizing the adjusted Tenhunen et al. approach [19].

Quantitative RT–PCR analysis of Panx1, TLR4

Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, Massachusetts, USA, Gene JET RNA Extraction Kit was used to extract total RNA from ovarian tissue in accordance with the manufacturer’s instructions. The optical density at 260 nm and the 260/280 nm ratio were the two metrics used to determine the concentration and purity of the RNA using a Nano-Drop spectrophotometer (Nano Drop Technologies, Inc., Wilmington). Following that, −80°C was used to store the RNA.

Using Revert Aid H Minus Reverse Transcriptase (Thermo Fisher Scientific), Waltham, Massachusetts, USA, the whole RNA was reverse transcribed to produce cDNA. Before being used, the cDNA was then kept frozen at −20°C. Relative expression levels of Panx1 and TLR4 were determined by using cDNA as a template in Step One Plus Real-Time PCR System (Applied Biosystem, Foster City, CA). GAPDH was the reference gene used. The primers of both genes are listed in Table 1.

Table 1.

shows the primer sequences used in the analysis.

| Gene | Foreword | Reverse |

|---|---|---|

| Panx1-1 | 5′ CTGTGGACAAGATGGTCACG 3′ | 3′CAGCAGGATGTAGGGGAAAA 5′ |

| TLR4 | 5′ AGCCAC GCATTCACAGGG 3′ | 5′ CATGGCTGGGATCAGAGTCC 3′ |

| GAPDH | 5′ ATGGGGAAGGTGAAGGTCG 3′ | 3′GAGGTCAATGAAGGGGTCAT 5′ |

Panx1: Pannexin 1, TLR4: toll-like receptor 4, GAPDH: glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase.

A ten-minute denaturation at 95°C was followed by forty consecutive cycles of denaturation for fifteen seconds at 95°C, annealing for thirty seconds at 60 °C, and extension for thirty seconds at 72°C to amplify cDNA.

The 2 − ΔΔCt method was used to determine the relative gene expression after the cycle threshold (Ct) values for the target and housekeeping genes were determined [20].

Histopathological examination and Immunohistochemical examination

Ovarian tissue samples from every group were kept for 24 hours at room temperature in 10% neutral buffered formalin. To prepare the samples for paraffin blocks and histological inspection, a series of histological processes were carried out on them, including dehydration, clearing, infiltration, and embedding in paraffin blocks. Blocks were then sectioned using a microtome, and the 5 μm thick slices were finally stained with haematoxylin and eosin (H&E). A camera attached to the light microscope (Olympus, Japan) was used to take pictures of the slides as they were being inspected [21].

Immunohistochemical analysis

By soaking the sections in secondary antibodies against goats and rabbits at a dilution of 1:300 for 90 minutes at 37°C, you can intensify the signal. (This step was performed using Universal LSABTM + Kit/HRP, Rabbit/Mouse/Goat, Product n K0690, and Bethyle Laboratories, Inc., USA.) To retrieve the antigen, sections were microwave-treated for 30 minutes with a 10 mm citrate buffer (pH 6.0). Primary antibodies (COX-2 goat polyclonal, VEGF goat and rabbit polyclonal) were diluted 1:500 for COX-2 (Abcam, UK) and 1:1000 for VEGF (Abcam, UK) and incubated on the slides for a whole night at 4°C in a humidity chamber.

Sections were subjected to four PBS-T washes before being incubated for ninety minutes at 37°C at a 1:300 dilution to boost the signal. After that, the sections were treated with secondary antibodies against rabbit and goat (Bethyle Laboratories, Inc., USA, and Universal LSABTM + Kit/HRP, Rabbit/Mouse/Goat, Product # K0690).

To get the brown coloration associated with successful outcomes, the slides were treated with DAB for five minutes. After using Mayer’s hematoxylin as a counterstain, the samples were rinsed with water. After that, the slides were mounted, dried off, and covered with slips. The Olympus BX50 Automated light microscope was used in conjunction with an Olympus digital camera to capture the images [22,23].

Morphometric study

Immuno-stained slices were used to assess the Cox2 optical density and VEGF immune-expression area percentage. For the morphometric analysis, five different sections from five different rats per group, each at a × 400 resolution, were submitted using Image J software (Media Cybernetics).

Statistical analysis

Using SPSS, the data were statistically examined to calculate the p-value, mean, and standard deviation. To statistically compare the outcomes between the groups, one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) and Tukey’s post hoc test were employed. P-value less than 0.05 was a significant difference. The sample size of each group was calculated according to DF (degree of freedom) formulas. The acceptable range is minimum (10) and maximum (20) according to Wan Nor et al. [24].

Results

Body weight, Lee index, fasting blood glucose, insulin levels, HOMA-IR and lipid profile

The control group’s body weight logically increased, as Table 2 illustrates. Nonetheless, differences in weight increase were noted between the treated and untreated PCOS model groups. The ultimate body weight of the model group was significantly increased. On the other side, the body weight of the AgNPs and zileuton co-treated group was considerably decreased versus the nontreated PCO group (P-value < 0.05). The Lee index of the PCOS group was significantly higher than that of the control group. On the other hand, compared with the untreated group, the Lee index of the AgNP and zileuton co-treated group decreased significantly (P-value < 0.05).

Table 2.

Body weight, Lee’s index, fasting serum glucose, insulin levels, HOMA-IR & Lipid profile.

| Parameters | I Control (n = 15) |

II PCO (n = 15) |

III PCO treated with AgNPs (n = 15) |

IV PCO treated with Zileuton (n = 15) |

V PCO treated with AgNPs + Zileuton (n = 15) |

P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Final body weight (g) | 192 ± 4.1 | 398.6 ± 4.2 a, c, d, e | 263.6 ± 21.8 a, b, d, e | 312 ± 13.5 a, b, c, e | 19.6 ± 3.5 b, c, d | P < 0.05 |

| Lee’s index (g/cm) | 302.6 ± .6 | 333 ± 4 a, c, d, e | 314.5 ± 1.5 a, b, e | 312.3 ± 1.5 a, b, e | 304 ± 2 b, c, d | P < 0.05 |

| FSG (mg/dl) | 87.3 ± 1.2 | 210.1 ± 2.1 a, c, d, e | 90.4 ± 1.4 a, b, d, e | 168.1 ± 18.4 a, b, c, e | 88.1 ± 0.9 b, c, d | P < 0.05 |

| Fasting insulin (μIU/L) | 10 ± 0.8 | 32.1 ± 2.6 a, c, d, e | 12.6 ± 0.6 a, b, d, e | 14.6 ± 0.6 a, b, c, e | 10.2 ± 0.6 b, c, d | P < 0.05 |

| HOMA-IR (FBG X fasting insulin/405) | 2.2 ± 0.1 | 17.1 ± 0.4 a, c, d, e | 2.5 ± 0.1 a, b, d | 5.7 ± 0.3 a, b, c, e | 2.4 ± 0.2 b, d | P < 0.05 |

| TAG (mg/dl) | 61.6 ± 2 | 132 ± 12.5 a, c, d, e | 69 ± 2.6 a, b, d | 81.6 ± 10.4 a, b, c, e | 63 ± 3.7 b, d | P < 0.05 |

| TC (mg/dl) | 80 ± 1 | 139.3 ± 7.5 a, c, d, e | 93 ± 15.7 a, b, d, e | 114.3 ± 5.1 a, b, c, e | 82.3 ± 4.9 b, c, d | P < 0.05 |

| LDL-c (mg/dl) | 22.8 ± 1.8 | 91.4 ± 3.1 a, c, d, e | 76.1 ± 5.1 a, b, d, e | 67.8 ± 2.3 a, b, c, e | 23.4 ± 1.4 b, c, d | P < 0.05 |

| HDL-c (mg/dl) | 54.06 ± 1.06 | 22.06 ± 3 a, c, d, e | 53.4 ± .6 b | 50.6 ± 5.1 b | 52.4 ± 1.69 b | P < 0.05 |

Note: Data are expressed as mean ± SD. FBG: fasting blood glucose, TAG: triacyl glycerol, TC: total cholesterol, LDL-c: low-density lipoprotein cholesterol, HDL-c: high-density lipoprotein cholesterol.

a p < 0.05 vs. control group I.

b p < 0.05 vs. PCO group II.

c p < 0.05 vs. AgNPs-treated group III.

d p < 0.05 vs. Zileuton-treated group IV.

p < 0.05 vs. AgNPs + Zileuton co- treated group V.

When compared to the control group, the PCOS group’s levels of fasting insulin and FSG increased significantly (P-value < 0.05), as seen in Table 2. However, the group that received AgNPs and zileuton concurrently had a considerable drop in these levels.

When compared to rats who were left untreated, the combination therapy had a more potent antihyperglycemic impact than either AgNP or zileuton alone (P-value < 0.05). Comparing the PCOS group to the control group, HOMA-IR revealed a significant increase in insulin resistance (P-value < 0.05). On the other hand, there was a notable decrease in the groups that received zileuton and AgNPs together. AgNPs and zileuton therapy together demonstrated a stronger anti-inflammatory response than either drug alone (P-value < 0.05).

Regarding lipid profile, the PCOS group showed a significant increase in serum TG, TC, and LDL-C levels with a marked reduction in serum HDLC levels compared to control one (P-value < 0.05). Nevertheless, the AgNPs and zileuton co-treated group displayed a significant decline in serum TG, TC, and LDL-C with a marked rise in HDL-C level compared to the untreated group (P-value < 0.05), as demonstrated in Table 2.

Serum levels of reproductive hormones, ferroptosis, apoptotic and oxido-inflammatory status

The PCOs model group showed significantly decreased estradiol and increased testosterone, which was improved by combined treatment with AgNPs and zileuton [as illustrated in Table 3]. Treatment with AgNPs and zileuton resulted in a more substantial hormonal regulatory effect than treatment with either AgNPs or zileuton alone (P-value < 0.05). There was no discernible difference between the control group and the AgNPs + zileuton group (P-value > 0.05). Comparing the PCOS group to the control group, they had considerably lower levels of FSH and significantly greater levels of LH and the LH/FSH ratio (P-value < 0.05). Rats co-treated with AgNPs + zileuton showed substantially reduced LH and LH/FSH ratios, but significantly greater FSH levels compared to untreated rats (P-value < 0.05). The combination of AgNPs and zileuton presented a more significant hormonal organizing role than AgNPs or zileuton-treated groups (P-value < 0.05).

Table 3.

Reproductive hormones, ferroptosis, apoptotic and oxido-inflammatory status.

| Parameters | I Control (n = 15) |

II PCO (n = 15) |

III PCO treated with AgNPs (n = 15) |

IV PCO treated with Zileuton (n = 15) |

V PCO treated with AgNPs + Zileuton (n = 15) |

P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Estradiol (pg/ml) | 14.5±.85 | 5 ± 1.61 a, c, d, e | 12 ± 1.05 a, b, d, e | 9.4 ± 1.2 a, b, c, e | 13.8 ± 1.7 b, c, d | P < 0.05 |

| Testosterone (ng/ml) | 0.31 ± 0.08 | 2.7 ± 0.25 a, c, d, e | 0.62 ± 0.07 a, b, d, e | 0.82 ± 0.06 a, b, c, e | 0.37 ± 0.03 b, c, d | P < 0.05 |

| LH (mIU/mL) | 0.87 ± 0.07 | 7.6 ± 0.6 a, c, d, e | 3.6 ± 0.6 a, b, e | 4.8 ± 1.4 a, b, e | 1.1 ± 0.2 b, c, d | P < 0.05 |

| FSH (mIU/mL) | 4.6 ± 0.68 | 1.5 ± 0.4 a, c, d, e | 2.2 ± 0.1a, b, e | 2.03 ± 0.3 a, b, e | 3.8 ± 0.45 b, c, d | P < 0.05 |

| LH/FSH ratio | 0.18 ± 0.01 | 5.3 ± 0.2 a, c, d, e | 1.5 ± 0.1 a, b, d, e | 1.2 ± 0.07 a, b, c, e | 0.42 ± 0.16 b, c, d, e | P < 0.05 |

| Fe + 2(nmol/mg tissue) | 0.2 ± 0.01 | 0.46 ± 0.03 a, d, e | 0.49 ± 0.04 a, d, e | 0.21 ± 0.03 b, c | 0.23 ± 0.06 b, c | P < 0.05 |

| HO-1 (nmol bilirubin/mg tissue protein/hour) | 1.6 ± 0.2 | 0.5 ± 0.1 a, d, e | 0.65 ± 0.22 a, d, e | 1.46 ± 0.4 b, c | 1.5 ± 0.3 b, c | P < 0.05 |

| TNF- α (pg/ml) | 49.8 ± 1.1 | 172.8 ± 11 a, c, d, e | 56.5 ± 5.5 b | 51.6 ± 3.08 b | 50.4 ± 6.5 b | P < 0.05 |

| NFκ-B (ng/ml) | 3.5 ± 0.4 | 13.2 ± 0.8 a, b, d, e | 3.8 ± 0.7 b | 3.7 ± 0.7 b | 3.3 ± 0.5 b | P < 0.05 |

| IL-6 (pglml) | 4.33 ± 0.45 | 11.3 ± 1.1 a, c, d, e | 4.6 ± 0.43 b | 4.4 ± 0.4 b | 4 ± 0.1 b | P < 0.05 |

| MDA (nmol/mg protein) | 2.6 ± 0.36 | 9.1 ± 0.3 a, c, d, e | 4.1 ± 0.32 a, b, e | 4.3 ± 0.61 a, b, e | 2.5 ± 0.35 b, c, d | P < 0.05 |

| Caspase 3 (ng/ml) | 2.4 ± 0.26 | 8.6 ± 1.6 a, c, d, e | 2.6 ± 0.7 b | 3.06 ± 1 b | 2.3 ± 0.37 b | P < 0.05 |

| GPX (IU/g tissue) | 26.06 ± 0.25 | 12.6 ± 1.3 a, c, d, e | 24.9 ± 1.9 b | 25.6 ± 0.4 b | 25.2 ± 2.1 b | P < 0.05 |

Note: Mean ± SD is used to represent data. HO-1; heme oxygenase 1, FSH; follicular stimulating hormone, LH; luteinizing hormone. TNF- α; tumour necrosis factor alpha, NFκ-B; nuclear factor kappa beta, IL-6; interleukin 6, MDA; malonaldehyde, GPX; glutathione peroxidase. ap < 0.05 vs. control group I, bp < 0.05 vs. PCO group II, cp < 0.05 vs. AgNPs-treated group III, dp < 0.05 vs. Zileuton-treated group IV, ep < 0.05 vs. AgNPs + Zileuton co-treated group V.

Inflammatory, oxidative stress, and apoptosis markers in Table 3 demonstrated significant elevations in serum levels of TNF-α, NF-κB, and IL-6 in the PCOS-IR group. AgNPs and/or zileuton treatment have reduced the inflammatory impact. However, the combined treatment had a stronger anti-inflammatory effect (P-value < 0.05). In the ovarian tissues of the untreated PCOS group, significant oxidative stress and apoptosis were indicated by high MDA levels, increased caspase activity and decreased GPX4 function compared to the control group (P-value < 0.05). The combined treatment exhibited the greatest improvement in oxidative stress and apoptotic tags (P-value < 0.05).

In PCOS, increased ovarian Fe+2 levels led to significant alterations in ferroptosis mediators Table 3. In PCOs, HO-1 activity was significantly lower in ovarian tissues, suggesting that the balance between pro-oxidants and antioxidants was disrupted and favored oxidative stress propagation. Zileuton treatment led to a greater reduction in ferroptosis markers compared to PCOS and AgNPs treatments (P-value < 0.05). The AgNPs-treated group had a significantly higher level than the other treated groups (P-value < 0.05).

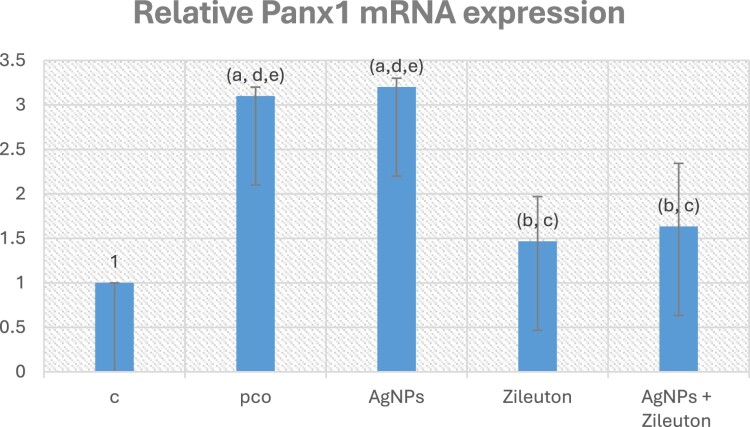

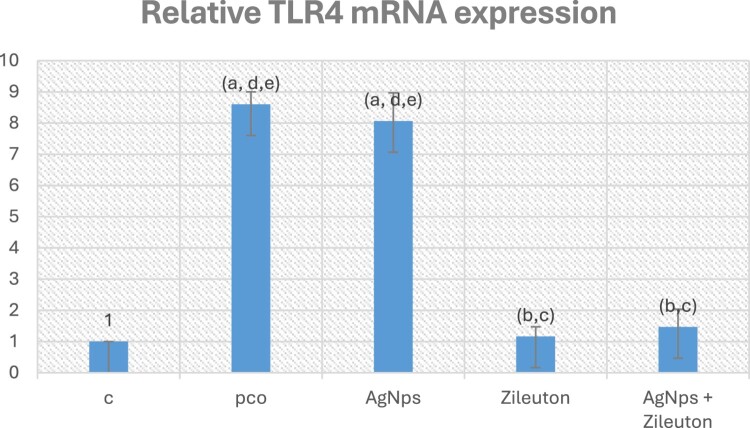

Panx1 and TLR4 mRNA expression

The ovarian tissues of the PCOS and AgNPs treated groups showed a substantial increase in Panx1 [Figure 1] and TLR4 mRNA expression [Figure 2] when compared to the control group. However, therapy with zileuton has mitigated this rise (P-value < 0.05).

Figure 1.

Relative Panx1 mRNA expression. Data are expressed as mean ± SD. Panx1: pannexin 1. a p < 0.05 vs. control group I, b p < 0.05 vs. PCO group II, c p < 0.05 vs. AgNPs- treated group III, d p < 0.05 vs. Zileuton- treated group IV, e p < 0.05 vs. AgNPs + Zileuton co- treated group V.

Figure 2.

Relative TLR4 mRNA expression. Data are expressed as mean ± SD. TLR4: toll-like receptor 4. a p < 0.05 vs. control group I, b p < 0.05 vs. PCO group II, c p < 0.05 vs. AgNPs- treated group III, d p < 0.05 vs. Zileuton- treated group IV, e p < 0.05 vs. AgNPs + Zileuton co- treated group V.

Histopathological and Immuno-histochemical Results

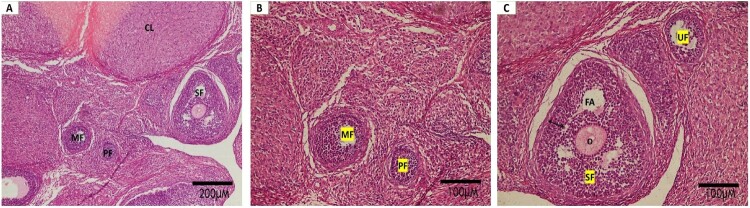

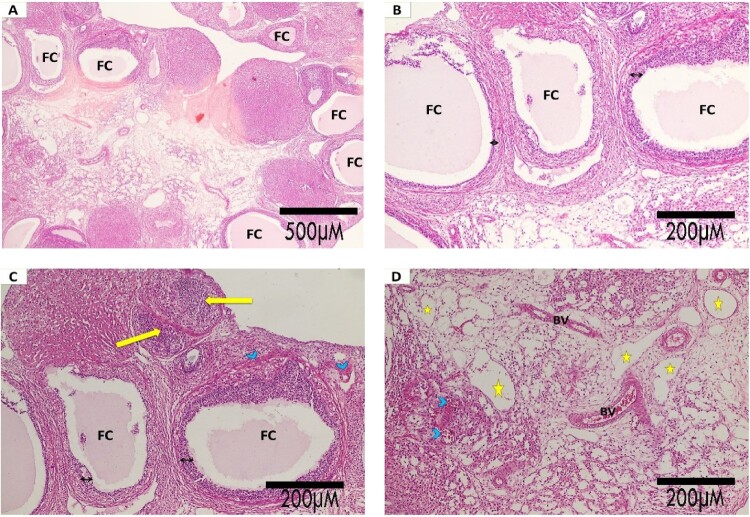

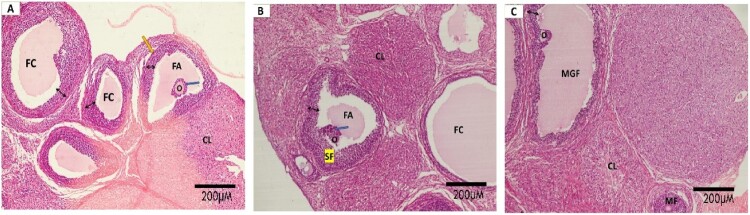

Hematoxylin & Eosin-stained sections of ovaries from the control group showed ovarian follicles in various stages of maturation: primary follicles, multilaminar follicles and secondary follicles which were seen with apparent oocytes surrounded by corona radiata, thick zona granulosa and follicular antrum. Also, corpus luteum was obvious [Figure 3A, B & C]. In the PCOS model group, all sections showed the development of follicular cysts, with absent oocyte and thin granulosa cells with some congested blood capillaries. Also, multiple vacuolations were noticed with areas of hemorrhage and cellular infiltration [Figure 4A, B, C& D]. Sections from PCO treated with AgNPs group demonstrated some cystic follicles, However, mature follicles with thick granulosa, theca cell layer, apparent oocyte and follicular antrum were clearly seen [Figure 5A]. In PCO treated with Zileuton group: mature follicle with an oocyte surrounded by corona radiata, follicular antrum and corpus luteum were obvious. Although, some follicular cysts were still present [Figure 5B]. In the combined treated group (PCO treated with AgNPs + Zileuton): Mature Graffian follicle was clearly seen with an apparent oocyte and thick granulosa layer. Also, multilaminar follicles and corpus luteum were present. No follicular cysts were detected [Figure 5C].

Figure 3.

Photomicrographs of H&E-stained sections of ovaries: Normal control: ovarian follicles in various stages of maturation: primary follicles (PF), multilaminar follicles (MF) and secondary follicles (Sf) which are seen with apparent Oocytes (O) surrounded by corona radiata and follicular antrum (FA). The thick zona granulosa layer (double head arrow) and corpus luteum (CL) are obvious. (a. H&E × 100; scale bar:200 μm, b. and c. H&E × 200; scale bar:100 μm).

Figure 4.

Photomicrographs of H&E-stained sections of ovaries: In the PCOS model group, all sections show the development of follicular cysts (FC), with absent oocyte and thin granulosa cells (double head arrow) with some congested blood capillaries (BV). Also, multiple vacuolations (stars) are noticed with areas of hemorrhage (arrow head) and cellular infiltration (yellow arrow) (a. H&E × 40; scale bar:500μm, b., c. and d. H&E × 100; scale bar:200μm).

Figure 5.

Photomicrographs of H&E-stained ovarian sections from PCO treated with AgNPs group demonstrate some cystic follicles (FC), However, mature follicle with thick granulosa (double head arrow), theca cell layer (yellow arrow), an apparent oocyte (O) surrounded by corona radiata (blue arrow), and follicular antrum (FA) are clearly seen (Figure 5a). In PCO treated with the Zileuton group: mature follicles with an oocyte (O) surrounded by corona radiata (blue arrow), follicular antrum (FA) and corpus luteum (CL) are obvious. Although, some follicular cysts (FC) are present (Figure 5b). In the combined treated group (PCO treated with AgNPs + Zileuton): the Mature Graffian follicle is clearly seen with an apparent oocyte (O) and thick granulosa layer (double head arrow). Also, multilaminar follicles (MF) and corpus luteum (CL) are seen. No follicular cysts are detected (Figure 5c) (H&E × 100; scale bar:200 μm)

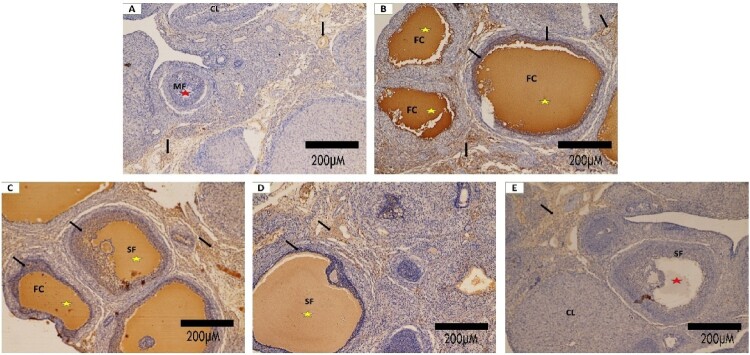

In the control group, COX-2 immunoreactivity was limited to stroma with no expression in the follicles [Figure 6A]. The PCOs sections demonstrated strong immunoreactivity to COX2 in granulosa and theca layers & follicular antrum [Figure 6B]. In PCO treated with AgNPs and PCO treated with Zileuton groups, the immunostaining of COX-2 was shown in the granulosa and theca layers & antrum less intense than in PCOS group but still higher than in control [Figure 6C & D]. However, COX-2 immunostaining in the last combined treated group presented no expression in the follicles in a way similar to the sections of ovaries of the control group [Figure 6E].

Figure 6.

Photomicrographs of COX-2 immunohistochemically stained ovarian sections: (A) In the control group, COX-2 immunoreactivity is limited to stroma with no expression in the follicles. (B) The PCOs sections demonstrate strong immunoreactivity to COX2 in granulosa and theca layers & follicular antrum. (C &D): In PCO treated with AgNPs and PCO treated with Zileuton groups, the immunostaining of COX-2 is shown in the granulosa and theca layers & antrum is less intense than in the PCOS group but still higher than control. (E) COX-2 immunostaining in the last combined treated group presents no expression in the follicles and is limited to stroma in a way similar to the sections of ovaries of the control group. (COX-2; scale bar:200 μm)

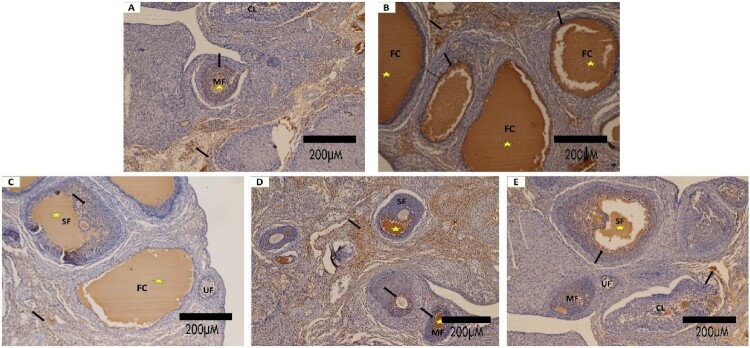

In the control group, the expression of VEGF examined by immunohistochemistry was limited to the stroma and granulosa layer [Figure 7A]. The PCOs showed strong immunoreactivity to VEGF in granulosa and theca layers & follicular antrum, and diffuse expression in ovarian stroma [Figure 7B]. In PCO treated with AgNPs and In PCO treated with Zileuton groups, VEGF showed less expression of VEGF in the follicular antrum than PCO group but still apparently higher than control [Figure 7C & D]. In the last combined treated group, the immunostaining of VEGF was seen in the stroma and very little expression in the follicles similar to the control group [Figure 7E].

Figure 7.

Photomicrographs of VEGF immunohistochemically stained ovarian sections: (A): In the control group, the expression of VEGF is limited to the stroma and granulosa layer. (B): The PCOs show strong immunoreactivity to VEGF in granulosa and theca layers & follicular antrum, and diffuse expression in ovarian stroma. (C&D): In PCO treated with AgNPs and In PCO treated with Zileuton groups, VEGF shows less expression of VEGF in the follicular antrum than PCO group but is still apparently higher than in the control. (E): In the last combined treated group the immunostaining of VEGF is seen in the stroma and very little expression in the follicles similar to the control group. (VEGF; scale bar:200μm)

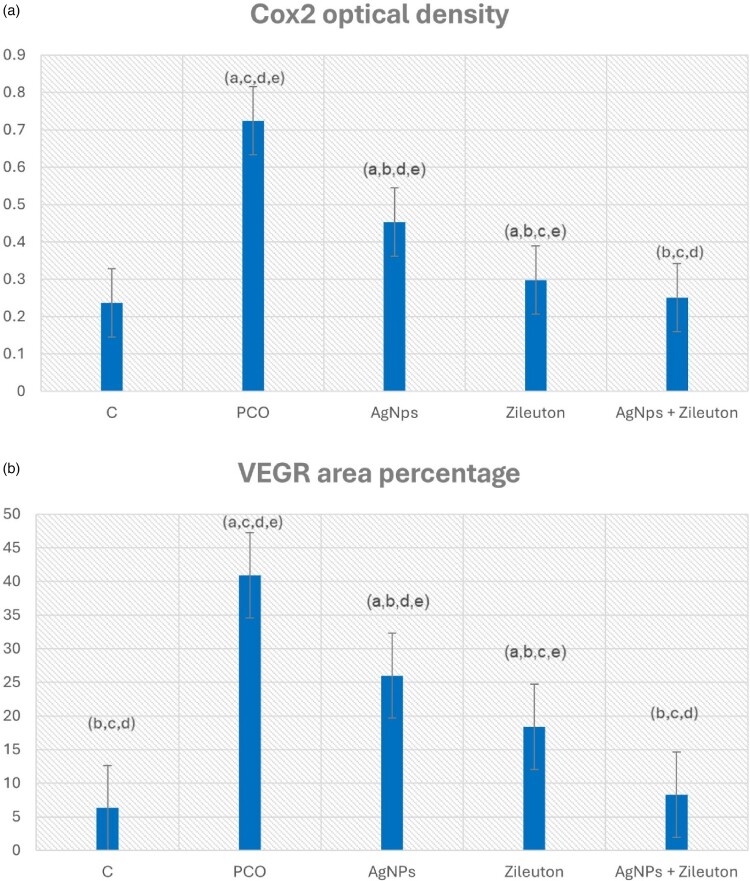

Statistical analysis indicated that Cox2 optical density increased significantly in the PCO group compared with the NC group, while decreased significantly in PCO treated with AgNPs group, PCO treated with Zileuton group & the last combined treated group compared to the PCO group [Figure 8A]. Area percentage of immunoexpression of VEGF was significantly higher in the PCO group than the control group, it decreased significantly in PCO treated with AgNPs group, PCO treated with Zileuton group & the last combined treated group in comparison to the PCO group [Figure 8B].

Figure 8.

(A) Represents Cox2 optical density. Data are expressed as mean ± SD. a p < 0.05 vs. control group I, b p < 0.05 vs. PCO group II, c p < 0.05 vs. AgNPs- treated group III, d p < 0.05 vs. Zileuton- treated group IV, e p < 0.05 vs. AgNPs + Zileuton co- treated group V. (B) Represents VEGR area percentage. Data are expressed as mean ± SD. a p < 0.05 vs. control group I, b p < 0.05 vs. PCO group II, c p < 0.05 vs. AgNPs- treated group III, d p < 0.05 vs. Zileuton- treated group IV, e p < 0.05 vs. AgNPs + Zileuton co- treated group V.

Discussion

Complicating matters, PCOS accounts for 80% of anovulatory infertility in women of reproductive age, making it the most common hormonal condition affecting them. Despite its commonality, the underlying causes and progression of PCOS remain inadequately understood [25]. Various theoretical frameworks have been proposed regarding its etiology, with growing evidence indicating that PCOS may be a multifaceted polygenic condition shaped by genetic predispositions, epigenetic modifications, and environmental factors [26].

The letrozole-induced model of PCOS effectively replicates the characteristics of human PCOS, exhibiting anovulatory cycles, morphological changes associated with the condition, increased body weight, heightened testosterone levels, and disturbances in glucose and lipid metabolism, alongside significant insulin resistance. Letrozole functions as an aromatase inhibitor, obstructing the conversion of testosterone to estradiol, which results in elevated levels of androgens in both the bloodstream and ovaries [27].

It is well known that 5-lipoxygenase (5-LOX) regulates the manufacture of pro-inflammatory mediators’ leukotrienes, which in turn plays a major role in controlling inflammation and immunological responses [28]. Consequently, inhibiting 5-LOX has been associated with protective effects against various inflammatory diseases [29]. Several investigations have verified that the production of leukotriene B4 (LTB4) via the 5-LOX pathway is a major factor in the development of insulin resistance in skeletal muscle, liver, and adipose tissue. Additionally, zileuton’s suppression of 5-LOX has been demonstrated to improve insulin sensitivity via activating the AMPK pathway [30,31].

Ferroptosis is a recently discovered kind of iron-dependent apoptosis characterized by the accumulation of (ROS) and products of lipid peroxidation from iron metabolism. Oocytes, trophoblasts, and granulosa cells are among the reproductive cells whose special features make them more susceptible to ferroptosis under pathological circumstances [32]. Li et al., 2024 showed that intracellular accumulation of Fe2+, release of ROS, lipid peroxidation, mitochondrial damage, up-regulation of the ferroptosis loading receptor and down-regulation of the master repressor of ferroptosis GPX4, result in ferroptosis of granulosa cells in models PCOS clinics [4]. Furthermore, several studies have demonstrated a favorable correlation between ferroptosis proteins and the reproductive outcomes of POCS patients experiencing infertility [33].

Additionally, ferroptotic cells have been shown to increase LOX activity by releasing a large amount of oxidized arachidonic acid for the intracellular production of inflammatory mediators. It also produces ferroptosis inflammation through the production of damage-associated pattern molecules (DAMP), which are immunogenic [34].

Several reports have implicated LOX as the main controller of ferroptotic cell death [5,35]. LOX-derived lipid peroxidation is a significant mechanism for the oxidative damage brought on by GPX4 inactivation that leads to apoptotic factor (AIF)-mediated cell death [36]. By reducing the intracellular redox state, GSH-GPX4 activity and cyst metabolism directly restrict LOX activation [37,38].

Moreover, oxidation of (PUFA) by LOX via an iron pool dependent on the catalytic subunit of phosphorylase kinase gamma 2 PHKG2 is required for ferroptosis, also removal of PUFA hydroperoxides is hindered by covalent inhibition of the catalytic selenocysteine in Gpx4; these findings imply novel approaches to regulate ferroptosis by blocking LOX in various circumstances. Interestingly, the discovery that pharmacological suppression of LOX is cytoprotective serves as the primary basis for the evidence that LOX is involved in ferroptosis. It has also been demonstrated that LOX activity suppression via siRNA, increases cell resistance to ferroptosis [39,40].

Several results demonstrate that the suppression of ferroptosis greatly lowers the amounts of ROS and inflammatory cytokines, such as IL-1β and TNFα, attenuating inflammation and enhancing cell function [41,42]. Mounting recent evidence demonstrated the substantial inhibitory effect of zileuton on ferroptosis; Sun et al., 2023 demonstrated that, through suppression of 5-LOX, zileuton attenuated iron accumulation in addition to lipid peroxidation and mitigated neuronal ferroptosis as well as neuroinflammation with subsequent improvement of motor function recovery after spinal cord injury in mice [43].

Indeed, zileuton anti-ferroptotic effect provided neuroprotection against glutamate oxidative toxicity, resulting in improving outcomes following a hemorrhagic stroke in mice. [44]. Furthermore, suppression of 5-LOX prevents acute retinal degeneration by shielding the retinal pigment epithelium from lipid peroxidation, mitochondrial and DNA damage, and ferroptosis caused by sodium iodate [45] as demonstrated by Lee et al. in 2022. According to recent research by Jung et al., zileuton may have an anti-ferroptotic effect because it upregulates the expression of GPX4, p-AKT, p-mTOR, and ferroptosis-related proteins 4-hydroxynonenal (4-HNE) and heme oxygenase-1 (HO-1) in renal tubular epithelial cells, as well as NRF2. This, in turn, improves renal damage linked to ferroptosis [8].

Beside the anti-inflammatory and inhibitory effect on 5-LOX, zileuton suppresses prostaglandin production by preventing macrophages from releasing arachidonic acid [46]. Consistent with this hypothesis, the present study showed that zileuton significantly reduced ovarian inflammatory markers. Tu et al., 2010 showed that zileuton inhibits the expression of NFk-B and attenuates the release of serum TNF-alpha and IL-1 beta, resulting in an effective anti-inflammatory effect [47]. Numerous investigations have documented the compelling antioxidant properties of zileuton. Zeltipoton reduced lipid peroxidation both in vivo and in vitro, boosted SOD expression and activity, and lowered NADPH oxidase expression and activity [48].

Our analysis confirmed that AgNP had no significant effect on ferroptosis indicators, but it did greatly ameliorate hormonal imbalance and had a major anti-inflammatory effect as indicated by a considerable decrease in the production of TNF-α and NF-κB. This result, as measured by IL-6 levels, is in line with earlier research by Fakhreldin et al., 2017; Syrvatka et al., 2014, which found that Ag-NPs normalized serum levels of FSH, LH, and estradiol in a PCO-affected mouse model. This was because the production of silver ions by silver nanoparticles inhibited ovarian steroidogenesis [49,50]. For instance, Karami et al., 2018 demonstrated that Ag-NPs can prevent PCO by reducing NO expression in the ovary by means of hypothalamic neuronal protection [51].

AgNPs dramatically decreased the inflammatory markers NF-κB, TGF-β, TNF-α, and IL-1β in vitro, according to research by Refaat et al., 2023 [52]. Furthermore, Fehaid et al., 2020 reported that AgNPs had a dose-dependent anti-inflammatory effect. AgNPs also have an antiapoptotic effect by reducing TNFR1 binding on the cell membrane, which depresses TNF-α signal transduction, including its apoptotic and DNA damage effects [53]. Additionally, AgNPs were found by Crisan et al. to reduce IκBα phosphorylation, which in turn suppressed pro-inflammatory cytokines [54]. Surprisingly, Park et al. (2010) discovered that silver nanoparticles (NPs) mitigated airway inflammation and hyperresponsiveness via regulating ROS production. This, in turn, decreases inflammation in mice suffering from allergic airway illness [55].

Our study revealed that a combination of zileuton and AgNPs showed a synergistic effect in the mitigation of the underlying ferroptotic and oxido-inflammatory pathophysiological processes involved in PCOS than each drug alone. Our results set the stage for the future creation of clinical regimens and offer fresh perspectives on possible PCOS treatment approaches.

Conclusion

By using the knowledge gathered, it was shown that using (AgNPs) and 5-lipoxygenase inhibitor (Zileuton) together had a unique therapeutic impact on PCO disorder by focusing on ferroptosis, opening a new avenue for a potential treatment for such a complex, multidimensional disorder.

Limitations

Using ELISA, without confirmation by Western blotting, is considered to be one of the study’s limitations. This leads to a future assessment of the interplay between the chief proteins examined in the current search.

Hypothesis for further work

In order to facilitate data amplification, in vitro studies on clinical applications are needed in order to extend our findings and enhance mechanism deduction. More investigations are needed to clarify the relationship between PCO, ferroptosis/hormonal axis, GPX4 and LOX interactions in future studies.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Data accessibility

Details are available upon request.

References

- 1.Singh S, Pal N, Shubham S, et al. Polycystic ovary syndrome: etiology, current management, and future therapeutics. J Clin Med. 2023;12(4):1454. doi: 10.3390/jcm12041454 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fujii J, Imai H.. Oxidative metabolism as a cause of lipid peroxidation in the execution of ferroptosis. Int J Mol Sci. 2024;25(14):7544. doi: 10.3390/ijms25147544 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sun S, Shen J, Jiang J, et al. Targeting ferroptosis opens new avenues for the development of novel therapeutics. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 2023;8(1):372. doi: 10.1038/s41392-023-01606-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Li X, Lin Y, Cheng X, et al. Ovarian ferroptosis induced by androgen is involved in pathogenesis of PCOS. Human Reproduction Open. 2024;2024(2):hoae013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shah R, Shchepinov MS, Pratt DA.. Resolving the role of lipoxygenases in the initiation and execution of ferroptosis. ACS Cent Sci. 2018;4(3):387–396. doi: 10.1021/acscentsci.7b00589 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Probst L, Dächert J, Schenk B, et al. Lipoxygenase inhibitors protect acute lymphoblastic leukemia cells from ferroptotic cell death. Biochem Pharmacol. 2017;140:41–52. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2017.06.112 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rossi A, Pergola C, Koeberle A, et al. The 5-lipoxygenase inhibitor, zileuton, suppresses prostaglandin biosynthesis by inhibition of arachidonic acid release in macrophages. Br J Pharmacol. 2010;161(3):555–570. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2010.00930.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jung KH, Kim SE, Go HG, et al. Synergistic renoprotective effect of melatonin and zileuton by inhibition of ferroptosis via the AKT/mTOR/NRF2 signaling in kidney injury and fibrosis. Biomol Ther (Seoul). 2023;31(6):599–610. doi: 10.4062/biomolther.2023.062 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tyavambiza C, Elbagory A, Madiehe M, et al. The antimicrobial and anti-inflammatory effects of silver nanoparticles synthesised from cotyledon orbiculata aqueous extract. Nanomaterials. 2021;11(5):1343–1343. doi: 10.3390/nano11051343 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Agarwal H, Nakara A, Shanmugam VK.. Anti-inflammatory mechanism of various metal and metal oxide nanoparticles synthesized using plant extracts: a review. Biomed Pharmacother. 2019;109:2561–2572. doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2018.11.116 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kim J-H, Han Y-J.. Effect of crude saponin of Korea red ginseng on high fat diet-induced obese rats. J Korean Med. 2006;27(3):1–13. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bracco EF, Yang MU, Segal K, et al. A new method for estimation of body composition in the live rat. Proc Soc Exp Biol Med. 1983;174:143–146. doi: 10.3181/00379727-174-2-RC1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rajan RK, M SSK, Balaji B.. Soy isoflavones exert beneficial effects on letrozole-induced rat polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS) model through anti-androgenic mechanism. Pharm Biol. 2017;55:242–251. doi: 10.1080/13880209.2016.1258425 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Janakiraman M. Protective efficacy of silver nanoparticles synthesized from silymarin on cisplatin induced renal oxidative stress in albino rats. Int J App Pharm. 2018;10(5):110–116. doi: 10.22159/ijap.2018v10i5.28023 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Marco F, et al. Pharmacological inhibition of leukotrienes in an animal model of bleomycin-induced acute lung injury. Respir Res. 2006;7:137. doi: 10.1186/1465-9921-7-137 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Allen-Worthington KH, Brice AK, Marx JO, et al. 2015. Intraperitoneal injection of ethanol for the euthanasia of laboratory mice (Mus musculus) and rats (Rattus norvegicus). J Am Assoc Lab Anim Sci; 54:769–778. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ohkawa H, Ohishi N, Yagi K.. Assay for lipid peroxides in animal tissues by thiobarbituric acid reaction. Anal Biochem. 1979;95:351–358. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(79)90738-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Schenkman JB, Cinti DL.. Preparation of microsomes with calcium. Methods Enzymol. 1978;52:83–89. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(78)52008-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tenhunen R, Marver HS, Schmid R.. Microsomal heme oxygenase. Characterization of the enzyme. J Biol Chem. 1969;244:6388–6394. doi: 10.1016/S0021-9258(18)63477-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Livak KJ, Schmittgen TD.. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2−ΔΔCT method. Methods. 2001;25:402–408. doi: 10.1006/meth.2001.1262 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bancroft John D, Layton Christopher Layton. The Hematoxylins and Eosin/connective and other mesenchymal tissues with their stains. In: Bancroft’s theory and practice of histological techniques. 8th ed. New York, London: Elsevier Health Sciences. Churchill Livingstone; 2019. p. 121–132. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ibrahim YF, Toni NDM, Thabet K, et al. Ameliorating effect of tocilizumab in letrozole induced polycystic ovarian syndrome in rats via improving insulin. MJMR. 2020;31(1):336–353. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Karimzadeh L, Nabiuni M, Kouchesfehani HM, et al. Effect of bee venom on IL-6, COX-2 and VEGF levels in polycystic ovarian syndrome induced in Wistar rats by estradiol valerate. J Venom Anim Toxins Incl Trop Dis. 2013;19(1):32. doi: 10.1186/1678-9199-19-32. PMID: 24330637; PMCID: PMC4029518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Arifin WN, Zahiruddin WM.. Sample size calculation in animal studies using resource equation approach. Malays J Med Sci. 2017;24(5):101–105. doi: 10.21315/mjms2017.24.5.11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Stener-Victorin E, Teede H, Norman RJ, et al. Polycystic ovary syndrome. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2024;10(1):27. doi: 10.1038/s41572-024-00511-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bruni V, Capozzi A, Lello S.. The role of genetics, epigenetics and lifestyle in polycystic ovary syndrome development: the state of the art. Reprod Sci. 2022;29(3):668–679. doi: 10.1007/s43032-021-00515-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Xu J, Dun J, Yang J, et al. Letrozole rat model mimics human polycystic ovarian syndrome and changes in insulin signal pathways. Med Sci Mon. 2020;26:e923073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mashima R, Okuyama T.. The role of lipoxygenases in pathophysiology; new insights and future perspectives. Redox Biol. 2015;6:297–310. doi: 10.1016/j.redox.2015.08.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jatana M, Giri S, Ansari MA, et al. Inhibition of NF-κB activation by 5-lipoxygenase inhibitors protects brain against injury in a rat model of focal cerebral ischemia. J Neuroinflammation. 2006;3:1–13. doi: 10.1186/1742-2094-3-12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mothe-Satney I, Filloux C, Amghar H, et al. Adipocytes secrete leukotrienes: contribution to obesity-associated inflammation and insulin resistance in mice. Diabetes. 2012;61(9):2311–2319. doi: 10.2337/db11-1455 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kwak HJ, Choi HE, Cheon HG.. 5-LO inhibition ameliorates palmitic acid-induced ER stress, oxidative stress and insulin resistance via AMPK activation in murine myotubes. Sci Rep. 2017;7(1):5025. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-05346-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Liu M, Wu K, Wu Y.. The emerging role of ferroptosis in female reproductive disorders. Biomed Pharmacother. 2023;166:115415. doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2023.115415 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lin S, Jin X, Gu H, et al. Relationships of ferroptosis-related genes with the pathogenesis in polycystic ovary syndrome. Front Med (Lausanne). 2023;10:1120693. doi: 10.3389/fmed.2023.1120693 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sun Y, Chen P, Zhai B, et al. The emerging role of ferroptosis in inflammation. Biomed Pharmacother. 2020;127:110108. doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2020.110108 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Yang WS, Kim KJ, Gaschler MM, et al. Peroxidation of polyunsaturated fatty acids by lipoxygenases drives ferroptosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2016;113(34):E4966–E4975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Seiler A, Schneider M, Förster H, et al. Glutathione peroxidase 4 senses and translates oxidative stress into 12/15-lipoxygenase dependent-and AIF-mediated cell death. Cell Metab. 2008;8(3):237–248. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2008.07.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Weitzel F, Wendel A.. Selenoenzymes regulate the activity of leukocyte 5-lipoxygenase via the peroxide tone. J Biol Chem. 1993;268(9):6288–6292. doi: 10.1016/S0021-9258(18)53251-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Li C, Deng X, Xie X, et al. Activation of glutathione peroxidase 4 as a novel anti-inflammatory strategy. Front Pharmacol. 2018;9:1120. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2018.01120 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kagan VE, Mao G, Qu F, et al. Oxidized arachidonic and adrenic PEs navigate cells to ferroptosis. Nat Chem Biol. 2017;13(1):81–90. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.2238 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Shintoku R, Takigawa Y, Yamada K, et al. Lipoxygenase-mediated generation of lipid peroxides enhances ferroptosis induced by erastin and RSL3. Cancer Sci. 2017;108(11):2187–2194. doi: 10.1111/cas.13380 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zhang Z, Wu YU, Yuan S, et al. Glutathione peroxidase 4 participates in secondary brain injury through mediating ferroptosis in a rat model of intracerebral hemorrhage. Brain Res. 2018;1701:112–125. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2018.09.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Chai Z, Ma T, Li Y, et al. Inhibition of inflammatory factor TNF-α by ferrostatin-1 in microglia regulates necroptosis of oligodendrocyte precursor cells. NeuroReport. 2023;34(11):583–591. doi: 10.1097/WNR.0000000000001928 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sun P, Zhao T, Qi H, et al. Zileuton ameliorates neuronal ferroptosis and functional recovery after spinal cord injury. Altern Ther Health Med. 2023;29(5):314–319. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Liu Y, Wang W, Li Y, et al. The 5-lipoxygenase inhibitor zileuton confers neuroprotection against glutamate oxidative damage by inhibiting ferroptosis. Biol Pharm Bull. 2015;38(8):1234–1239. doi: 10.1248/bpb.b15-00048 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lee JJ, Chang-Chien GP, Lin S, et al. 5-lipoxygenase inhibition protects retinal pigment epithelium from sodium iodate-induced ferroptosis and prevents retinal degeneration. Oxid Med Cell Longevity. 2022;2022(1):1792894. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kubick N, Pajares M, Enache I, et al. Repurposing zileuton as a depression drug using an AI and in vitro approach. Molecules. 2020;25(9):2155. doi: 10.3390/molecules25092155 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Tu XK, Yang WZ, Wang CH, et al. Zileuton reduces inflammatory reaction and brain damage following permanent cerebral ischemia in rats. Inflammation. 2010;33:344–352. doi: 10.1007/s10753-010-9191-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Czapski GA, Czubowicz K, Strosznajder RP.. Evaluation of the antioxidative properties of lipoxygenase inhibitors. Pharmacol Rep. 2012;64(5):1179–1188. doi: 10.1016/S1734-1140(12)70914-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Fakhreldin MBMR, Bajilan S, Al-naqeeb GD.. Effect of silver nanoparticles on levels of serum fsh, lh and estradiol in pco-induced female mice. World J Pharm Res. 2017;6(11):113–125. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Syrvatka V, Rozgoni I, Slyvchuk Y, et al. Effects of silver nanoparticles in solution and liposomal form on some blood parameters in female rabbits during fertilization and early embryonic development. J Microbiol Biotechnol Food Sci. 2014;3(4):274–278. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Karami M, Salami E, Dehkordi AJ, et al. Protective effect of silver nano particles against ovarian polycystic induced by morphine in rat. Nanomed Res J. 2018;3(4):1179–1188. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Refaat M, Fathy S, Ragaa M, et al. Silver nanoparticles attenuate inflammation aggravation in hepatocellular carcinoma in rats. Arab J Nucl Sci Appl. 2023;56(4):73–80. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Fehaid A, Fujii R, Sato T, et al. Silver nanoparticles affect the inflammatory response in a lung epithelial cell line. Open Biotechnol J. 2020;14(1):113–123. doi: 10.2174/1874070702014010113 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Crisan D, Scharffetter-Kochanek K, Crisan M, et al. Topical silver and gold nanoparticles complexed with Cornus mas suppress inflammation in human psoriasis plaques by inhibiting NF-κB activity. Exp Dermatol. 2018;27:1166–1116. doi: 10.1111/exd.13707 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Park HS, Kim KH, Jang S, et al. Attenuation of allergic airway inflammation and hyperresponsiveness in a murine model of asthma by silver nanoparticles. Int J Nanomed. 2010: 505–515. doi: 10.2147/IJN.S11664 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Details are available upon request.