Abstract

With advancing age, progressive loss of muscle strength, as assessed by hand grip strength, may result in a poorer health-related quality of life. The aim of this study is to determine the associations of hand grip strength with quality of life among people aged 50–90 years from South West Poland. The study group comprised 1 446 people, including 351 men and 1 095 women, aged between 50 and 90 years. The WHOQoL-BREF questionnaire was used to assess quality of life. Hand grip strength of the dominant hand was measured. The general assessment of quality of life shows a significant relationship with hand grip strength. Two domains of quality of life: social and environmental also significantly differentiate hand grip strength. As the number of points in given domains increases, the hand grip strength increases. Among men, the relationship between the environmental domain and hand grip strength is significantly stronger compared to women. Hand grip strength is related to the quality of life among older adults, especially in the social and environmental domains. The results of our study suggest that measures need to be taken to improve the strength of skeletal muscles in adults, which might improve their quality of life.

Keywords: Aging, Hand grip strength, Muscle strength, Quality of life, WHOQoL

Subject terms: Diseases, Health care, Medical research, Risk factors

Introduction

An important biomarker of current health status in older adults is hand grip strength (HGS). It is associated with the overall skeletal muscle strength1,2, bone mineral density3, fractures4, falls5, diabetes5and multimorbidity6,7. In addition, cognitive function8, depression9and sleep10problems show association with hand tightness strength. Hand grip strength is also an important predictor of future outcomes for older adults, and has been reported to be associated with disease occurrence, hospitalisation and mortality11–13.

With advancing age, progressive loss of muscle strength as assessed by hand grip strength may result in a poorer health-related quality of life (HRQoL). Studies have reported a relationship between hand grip strength and quality of life among Swedish14, Italian15, Korean16,17and Brazilian18population. However, such studies are rather rare and come and data are limited to few countries. Furthermore, there are large ethnic and cultural differences between societies from Europe and those from Asia, South America and other continents. These differences are also observed within different regions within Europe suggesting that quality of life and health should be considered in a socio-cultural and economic context. Population health profiles in Europe vary widely and indicate substantial differences in demographic and epidemiological changes across regions and different ageing patterns19. It has been reported that people in Southern European countries tend to enjoy high life expectancy although they exhibit a poorer population health profile compared to people living in Northern and Central Europe20. Data coming from Eastern European countries exhibit even worse health outcomes compared to Southern European countries, but also show the highest mortality rates on the continent19,21. Among European countries using SHARE data (i.e., a longitudinal survey representative of the non-institutionalised population aged 50 years and older), Poland was ranked among the Eastern European countries with the poorest health outcomes in Europe19. One study conducted in Czech Republic reports that people from post-communist countries often maintained an unhealthy lifestyle22and treated physical and mental health less seriously compared to older adults from Western countries22,23. Therefore, the quality of life of older adults in different European countries may vary and the factors determining it may differ.

Current studies in Poland on handgrip strength in adults, including older adults, focus on the relationship between handgrip strength and physical fitness and functional independence24–27, sarcopenia28, frailty syndrome29, hemodynamic parameters30, menopause31, and cognitive functioning and depression26,32. No current studies, to our knowledge, show the relationship between handgrip strength and quality of life in adults and in older adults in Poland.

Muscle strength is one of the components of health-related physical fitness, which includes elements that have a positive effect on health and can be improved by regular physical activity33. Static strength increases in women and men until the age of 45 and then it decreases gently. Age 50 + is a period of late adulthood, in which clear involution processes occur that affect the handgrip strength33.

The aim of this study is to determine the associations of hand grip strength with quality of life among people aged 50–90 years from South West Poland.

Methods

Study design and settings

The study was conducted between the years 2010 and 2016 at the University of Health and Sport Sciences in Wroclaw, in the Laboratory of Biokinetics Research having the Quality Management System Certificate -PIV-EN ISO 9001: 2009 (No. PW 48606-10E). The project was funded by the Ministry of Science and Higher Education (project number N404 075337). The project involved research on the assessment of the physical and biological condition and quality of life of older adults in Poland. The study obtained the approval of the Commission for Ethics of Scientific Research of University of Health and Sport Sciences in Wroclaw (2009, amended in 2015) and complied with the ethical requirements for human experimentation in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. Each participant signed a voluntary and informed consent to participate in the study. The research was conducted by a trained research team of the Department of Biostructure at the University of Health and Sport Sciences in Wroclaw, seminarians and PhD students. The research was retrospectively registered on the ISRCTN platform as 18,225,729.

Participants

This study involved a representative of the population sample of people aged 50–90 years living in South West Poland. The study group comprised 1 446 people, including 351 men and 1 095 women. Participants volunteered for the study advertised in the local media. Invitations were also sent to senior citizens’ centres. The mean age of male and female participants was 66.52 and 64.81 years respectively.

The study used the following inclusion criteria: age 50–90 years, ability to walk independently, good mental contact, no medical contraindications, and voluntary written consent to participate in the study. Exclusion criteria included cancer, acute trauma and infection, febrile states, recent myocardial infarction, other medical contraindications and lack of consent to participate in the study.

Research tools

The WHOQoL-BREF questionnaire in the Polish version34,35was used to assess quality of life (QoL). This scale includes an assessment of overall quality of life, self-assessment of health and 4 domains of quality of life: somatic, psychological, social and environmental. The somatic domain consists of 7 questions, assessing complaints of pain, sleep, and functioning and capacity in daily life. The psychological domain consists of 6 questions, assessing meaning and satisfaction with life and experiencing sadness, anxiety or depression. The social domain consists of 3 questions related to social relationships, intimate and family life as well as support from friends. The environmental domain contains 8 questions and assesses security in daily life, financial status, availability of information, housing, health care facilities and communication. A score of 1 to 5 can be obtained for each question. The higher the domain score, the higher the quality of life. The raw scores were transformed according to the 0–100key to correspond to the WHOQoL-100 scale scores35.

Hand grip strength (HGS) was measured using a hydraulic hand dynamometer (JAMAR, Hand Dynamometer USA) with adjustable handle set to the 2nd position. The grip strength of the dominant hand was measured to the nearest 1 kg. The following recommendations of the American Society of Hand Therapists (ASHT) were used: study participants were seated, the shoulder adducted and neutrally rotated, the elbow flexed at 90◦, and the forearm and the wrist in a neutral position (the wrist between 0◦ and 30◦ of dorsiflexion)36. The measurement was performed twice. Participants were instructed to clench the hand maximally and hold for 3–6 s. The interval between trials was approximately 1 min. During each measurement, participants were verbally motivated to maximally squeeze the grip. The higher value of the two samples was used for analysis. Height was measured to the nearest 0.1 cm and body weight to the nearest 0.1 kg using an electronic balance with an integrated digital stadiometer SECA 764 (Seca GmbH & Co. KG. Germany). The BMI was then calculated.

Statistical methods

Before analysis normality of continuous variables were checked by the Shapiro-Wilks test. To estimate significance of differences between two groups for continuous variables, a t-test for independent sample was used. Mann-Whitney U test was used for data including variables significantly deviated from normal distribution. Effects of a particular variable on HGS of the dominant hand was tested by the means of Generalized Linear Model with logit link function, and significance estimated based on the Wald’s chi-square. The model included second order interactions between sex and scores for a particular domain of quality of life. A significance level of p ≤ 0.05 (two sided) was adopted to assess statistical significance.

Results

Descripitive data

59.6% of study participants had married status, 19.9 were widowed, 12.3 were divorced and remaining 8.5% were single or in separation. 89.6% of study participants had at least college or university education (of whom 44 individuals had PhDs). 50% of participants had one or two children, 44.1% had three or more children and 5.9% did not have children.

Descriptive statistics of continuous variables and frequencies of categories of categorized variables were presented in Tables 1 and 2. HGS, height and BMI, as expected, showed significant sex differences, with males exhibiting higher values. Males were also older and showed significantly higher (mean) values in all domains of quality of life, except for social domain (Table 1).

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics of continuous variables by sex. Sex differences were estimated using Student’s t-test for independent samples.

| Males = 351 | Females = 1095 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | SD | Mean | SD | t / Z | p | |

| HGS dominant hand | 46.28 | 9.91 | 27.26 | 6.84 | 40.45 | < 0.001 |

| Age [years] | 66.52 | 7.69 | 64.81 | 7.14 | 3.97 | < 0.001 |

| Height [cm] | 173.38 | 6.26 | 159.15 | 5.98 | 38.35 | < 0.001 |

| BMI [kg/m2] | 28.80 | 3.59 | 28.28 | 4.75 | 1.88 | 0.060 |

| Somatic d. | 73.76 | 12.95 | 71.39 | 12.62 | 3.53* | < 0.001 |

| Psychological d. | 65.52 | 12.93 | 60.97 | 13.21 | 5.78* | < 0.001 |

| Social d. | 69.39 | 16.11 | 67.62 | 16.85 | 1.28* | 0.110 |

| Environmental d. | 67.56 | 12.26 | 65.36 | 12.07 | 3.13* | < 0.01 |

*test U Mann-Whitney.

Table 2.

Descriptive statistics, frequencies of individual categories of qualitative characteristics by gender. The significance of differences in frequencies in individual categories of variables was assessed using the Pearson Chi-square test.

| Males = 351 | Females = 1095 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | % | N | % | X2 (df) | p | |

|

Age <60 60–69 70–79 >80 |

65 171 103 12 |

18.51 48.72 29.34 3.42 |

222 628 224 21 |

20.28 57.35 20.46 1.92 |

19.85 (4) | < 0.001 |

|

Education level College and higher Trade and basic |

312 39 |

88.89 11.11 |

983 112 |

89.77 10.23 |

0.22 (1) | 0.637 |

|

Quality of life 1 2 3 4 5 |

5 7 62 242 35 |

1.42 1.99 17.66 68.95 9.97 |

5 29 224 761 76 |

0.46 2.65 20.46 69.50 6.94 |

8.30 (4) | 0.081 |

|

Selfassessment of health 1 2 3 4 5 |

3 37 95 193 23 |

0.85 10.54 27.07 54.99 6.55 |

16 126 327 582 44 |

1.46 11.51 29.86 53.15 4.02 |

5.53 (4) | 0.237 |

Among men and women, the most represented age group is 60–69, followed by 70–79 and < 60 age groups (Table 2). Men do not differ significantly from women in terms of education level, general self-assessment of quality of life and health (Table 2).

Main results

The general assessment of the quality of life shows a significant relationship with hand grip strength, regardless of gender, body dimensions, education and self-assessment of health. Moreover, two domains of quality of life: social and environmental also significantly differentiate HGS. As the number of points in given domains increases, the hand grip strength increases (Table 3).

Table 3.

Results of the generalized Linear Model estimating the relationship between hand grip strength and quality of life parameters, controlling for body dimensions, self-assessment of health and education.

| df | Wald’s Χ2 | p | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | 1 | 25,87 | < 0.001 |

| Age (categorised) | 4 | 71,35 | < 0.001 |

| Education level | 1 | 1,60 | 0.205 |

| Quality of life (general) | 4 | 10,09 | 0.038 |

| Selfassessment of health | 4 | 7,14 | 0.128 |

| Height | 1 | 164,45 | < 0.001 |

| BMI | 1 | 14,47 | < 0.001 |

| Somatic domain | 1 | 3,30 | 0.069 |

| Psychological domain | 1 | 0,12 | 0.724 |

| Social domain | 1 | 13,76 | < 0.001 |

| Environmental domain | 1 | 15,96 | < 0.001 |

| Second order interaction with sex | |||

| Somatic domain | 1 | 3,90 | 0.048 |

| Psychological domain | 1 | 3,22 | 0.072 |

| Social domain | 1 | 0,24 | 0.625 |

| Environmental domain | 1 | 9,19 | 0.002 |

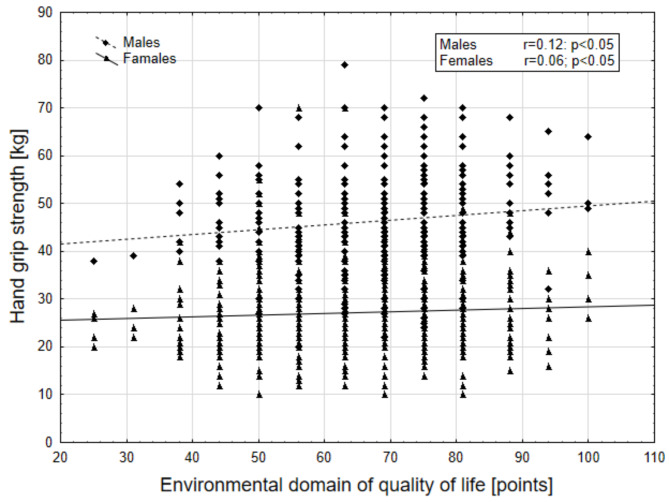

Two domains: somatic and environmental, also show significant relationships with hand grip strength, although this relationship differs in both sexes. In women, the relationship between the social domain and HGS is stronger compared to men. However, the correlation coefficients in both sexes are statistically nonsignificant. In addition, in men the relationship between the environmental domain and HGS is significantly stronger than in women (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Effect of interaction between sex and environmental domain of quality of life on hand grip strength of dominant hand.

Discussion

Studying the relationship between hand grip strength and quality of life has become an important area of research promoting good aging. The progressive loss of muscle strength may result in a poorer quality of life in old age. The aim of the study was to determine the relationship between hand grip strength and the quality of life of people aged 50–90 from South West Poland.

Our research has shown that skeletal muscle strength has a significant relationship with the overall quality of life and with the social and environmental domains. The results of our study show that the greater the hand grip strength, the higher the value of the overall quality of life and thus highlight the importance of skeletal muscle strength in older people. The strength of skeletal muscles not only affects family life, but also influences social relationships with non-kin, such as friends. The relationship between hand grip strength and the environmental domain is stronger in men compared to women. This suggests that, compared to women, men might benefit more from physical strength in terms of environmental functioning. A strong older man feels safer in everyday life and has a good appreciation of his living environment.

In 2015, the World Health Organization (WHO) defined the goal of healthy aging as helping people in “developing and maintaining the functional ability that enables well-being”. Functional ability is determined, among other things, by the internal capabilities of the individual. The significant loss of intrinsic functional ability in older adults is characterized by common problems such as difficulty walking at a normal pace, loss of muscle mass, and impairment of strength and mobility37. Therefore, poor muscle strength reduces the functional abilities and well-being of older adults, which may be associated with a poorer quality of life.

Maintaining the appropriate level of strength and quality of skeletal muscles is extremely important for older people. Thus, muscle strength is an important component of health-related physical fitness38. With age, muscle strength levels deteriorate significantly. Researchers have observed significant decreases in muscle strength in older people39–42. In older adults, functional independence is directly related to physical fitness, and aging is inevitably associated with lower performance of systems and organs that are directly related to physical fitness. For instance, age-related reduced physical fitness and physical activity contributes to the development of sarcopenia5,18,43, frailty syndrome37,38,44, or disability6, which seriously impair quality of life. Maintaining muscle strength at optimal levels can contribute to improved health-related quality of life and can add an important dimension to promoting good aging14. Other researchers also reported the relationship between hand grip strength and quality of life. For example, higher levels of hand grip strength were associated with better quality of life in Korean women and this association was stronger in women who were older (65–79 years), had a higher BMI, and had low physical activity16. Quality of life was found to be positively associated with hand grip strength in Brazilian women and men18, and in Italian older adults over 90 years of age15. Importantly, among Korean older adults with poor hand grip strength were characterized by low quality of life17while in hospitalized patients, hand grip strength was a predictor of quality of life and length of hospital stay45.

It is worth noting that, compared to women, men declared significantly higher quality of life in somatic, psychological and environmental domains. Our findings showing differences in assessment of quality of life depending on gender and lower quality of life exhibited by older women were also supported by other researchers17,46,47. Expectedly, the results of our study also showed that women also have lower hand grip strength compared to men. In older age, when physical fitness deteriorates and muscle strength systematically declines, the risk of losing independence in everyday life increases. The decline in muscle strength observed in older women, especially in physically inactive women, has been reported previously42. For example, among older women from Northern Ireland, the upper limb muscle strength of approximately 10% of the participants was so weak that they were unable to lift an object weighing 20% of their body weight39. Of 17 elderly Polish women from social welfare homes, aged over 85, 6 met the frailty criterion regarding hand grip strength while 16 met the criterion regarding walking speed48suggesting that skeletal muscle strength is therefore an important factor influencing walking speed43. In Danish older adults, hand grip strength decreased with age in both women and men. A significant decrease in strength among women compared to young people has been reported among individuals aged 50–59, while among men only in the group 60–6949.

Hand grip strength may vary among respondents living in different countries as they are exposed to different cultural, social and economic conditions. Russian adults aged 55–89 had weaker hand grip strength compared to individuals from England and Denmark, except for the groups aged 80–8912. Moreover, Russian respondents aged 40–69 showed a lower hand grip strength compared to their Norwegian peers. The largest differences were observed for women and men in the 60–69 age group50. This study also shows that differences in grip strength between Russian and northern European populations become apparent in the 40s before the decline in muscle function that is typically observed in older age50. This suggests a potentially important role of factors influencing the development of peak muscle strength during the first two decades of ontogeny. In the SHARE study, Poland was ranked among the Eastern European countries with the poorest health status in relation to the inhabitants of other European regions19. The first two decades of ontogenetic development, i.e., their childhood and adolescence, took place around the war, under different cultural and socio-economic conditions compared to their peers from Western and Northern Europe. Stress, whether related to a difficult childhood or an uneasy economic situation, can have an important impact on physical strength and quality of life. Therefore, to obtain meaningful data it might be of a critical importance to examine the relationship between hand grip strength and quality of life among older adults from different regions exposed to different cultural, economic and social conditions.

The strength of the study is that it shows the quality of life levels and handgrip strength of older adults and the relationships between them. So far, few studies have examined the relationship between quality of life and hand grip strength among older adults in Poland or in Central and Eastern European countries. Another strength of the study is a large number of seniors surveyed, which allows the findings to be generalized to the entire area of South West Poland. Moreover, the study was carried out in person by the same team of researchers, which makes it possible to assess the actual current quality of life of the respondents.

The study is not free from limitations mainly because the study sample might not be entirely representative of other parts of Poland. Indeed, compared to other parts of Poland, the area of South West Poland consists largely of lands regained after World War II and in the immediate post-war years, there were numerous migrations of Poles to these areas. Therefore, the level of quality of life of respondents may be different from the level of quality of life of older adults throughout Poland. For a more complete characterization of the quality of life of older Poles, research should also cover other regions of the country.

Conclusion

The results of our study show that hand grip strength is related to the quality of life of older adults, especially in the social and environmental domains. Our research suggests that HGS is an important biomarker of the quality of life of older adults.

Our study also suggests that taking specific measures are necessary to improve the strength of skeletal muscles in adults, and thus their quality of life.

Author contributions

A.K. - designed the study, collected the data, interpreted results, wrote the main manuscript text; S. K. - analysed the data, interpreted results, prepared tables and figure; Z. I. - designed the study, interpreted results, edited the manuscript text; All authors reviewed the manuscript and approved the submitted version.

Funding

Ministry of Science and Higher Education (project no. N404 075337).

Data availability

The data presented in this study are available on request. Contact details: Antonina Kaczorowska, University of Opole, Institute of Health Sciences, email: antonina.kaczorowska@uni.opole.pl.

Declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Consent to participants

All participants gave their informed written consent to the study.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Bohannon, R. W. Muscle strength: clinical and prognostic value of hand-grip dynamometry. Curr. Opin. Clin. Nutr.18 (5), 465–470 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Porto, J. M. et al. Relationship between grip strength and global muscle strength in community-dwelling older people. Arch. Gerontol. Geriatr.82, 273–278 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ma, Y. et al. Muscle strength rather than muscle mass is associated with osteoporosis in older Chinese adults. J. Formos. Med. Assoc.117 (2), 101–108 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Denk, K., Lennon, S., Gordon, S. & Jaarsma, R. L. The association between decreased hand grip strength and hip fracture in older people: a systematic review. Exp. Gerontol.111, 1–9 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Vasconcelos, K. S. et al. Handgrip strength cutoff points to identify mobility limitation in community-dwelling older people and Associated factors. J. Nutr. Health Aging. 20 (3), 306–315 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bohannon, R. W. Grip strength: an indispensable biomarker for older adults. Clin. Interv Aging. 14, 1681–1691 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yorke, A. M., Curtis, A. B., Shoemaker, M. & Vangsnes, E. The impact of multimorbidity on grip strength in adults age 50 and older: data from the health and retirement survey (HRS). Arch. Gerontol. Geriatr.72, 164–168 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kobayashi-Cuya, K. E. et al. Observational Evidence of the Association between Handgrip Strength, Hand Dexterity, and cognitive performance in Community-Dwelling older adults: a systematic review. J. Epidemiol.28 (9), 373–381 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ashdown-Franks, G. et al. Handgrip strength and depression among 34,129 adults aged 50 years and older in six low- and middle-income countries. J. Affect. Disord. 243, 448–454 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lee, G., Baek, S., Park, H. W. & Kang, E. K. Sleep quality and attention may correlate with hand grip strength: FARM Study. Ann. Rehabil Med.42 (6), 822–832 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Eekhoff, E. M. W. et al. Relative importance of four functional measures as predictors of 15-year mortality in the older Dutch population. BMC Geriatr.19 (1), 92. 10.1186/s12877-019-1092-4 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Oksuzyan, A. et al. Handgrip strength and its prognostic value for mortality in Moscow, Denmark, and England. PloS ONE. 12 (9), e0182684. 10.1371/journal.pone.0182684 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Martín-Ponce, E. et al. Prognostic value of physical function tests: hand grip strength and six-minute walking test in elderly hospitalized patients. Sci. Rep.4, 7530. 10.1038/srep07530 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Halaweh, H. Correlation between Health-Related Quality of Life and hand grip strength among older adults. Exp. Aging Res.46 (2), 178–191 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Laudisio, A. & Study Working Group. Muscle strength is related to mental and physical quality of life in the oldest old. Arch. Gerontol. Geriatr. 89, 104109; (2020). 10.1016/j.archger.2020.104109 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 16.Hong, Y. S. & Kim, H. Hand grip strength and health-related quality of life in postmenopausal women: a national population-based study. Menopause28 (12), 1330–1339 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Park, H. J. et al. Hand grip strength, osteoporosis, and Quality of Life in Middle-aged and older adults. Med. (Kaunas). 59 (12), 2148. 10.3390/medicina59122148 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Marques, L. P., Confortin, S. C., Ono, L. M., Barbosa, A. R. & d’Orsi, E. Quality of life associated with handgrip strength and sarcopenia: EpiFloripa Aging Study. Arch. Gerontol. Geriatr.81, 234–239 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Solé-Auró, A. & Gumà, J. Healthy) aging patterns in Europe: a Multistate Health Transition Approach. J. Popul. Ageing. 16 (1), 179–201 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Eikemo, T. A., Bambra, C., Judge, K. & Ringdal, K. Welfare state regimes and differences in self-perceived health in Europe: a multilevel analysis. Soc. Sci. Med.66 (11), 2281–2295 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mackenbach, J. P. et al. Trends in health inequalities in 27 European countries. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A. 115 (25), 6440–6445 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mudrak, J., Stochl, J., Slepicka, P. & Elavsky, S. Physical activity, self-efficacy, and quality of life in older Czech adults. Eur. J. Ageing. 13 (1), 5–14 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dragomirecká, E. et al. Demographic and psychosocial correlates of quality of life in the elderly from a cross-cultural perspective. Clin. Psychol. Psychot. 15 (3), 193–204 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wiśniowska-Szurlej, A., Ćwirlej-Sozańska, A., Wołoszyn, N., Sozański, B. & Wilmowska-Pietruszyńska, A. Association between Handgrip Strength, mobility, Leg Strength, Flexibility, and postural balance in older adults under Long-Term Care facilities. BioMed. Res. Int. 1042834. 10.1155/2019/1042834 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 25.Wiśniowska-Szurlej, A. et al. Reference values and factors associated with hand grip strength among older adults living in southeastern Poland. Sci. Rep.11 (1), 9950. 10.1038/s41598-021-89408-9 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wołoszyn, N., Grzegorczyk, J., Wiśniowska-Szurlej, A., Kilian, J. & Kwolek, A. Psychophysical health factors and its correlations in Elderly Wheelchair users who live in nursing homes. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health. 17 (5), 1706. 10.3390/ijerph17051706 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zasadzka, E., Trzmiel, T., Kasior, I. & Hojan, K. Does Hand grip Strength (HGS) Predict Functional Independence differently in patients post hip replacement due to Osteoarthritis versus patients Status Post hip replacement due to a fracture? Clin. Interv Aging. 18, 1145–1154. 10.2147/CIA.S415744 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pachołek, K. & Sobieszczańska, M. Sarcopenia Identification during Comprehensive Geriatric Assessment. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health. 19 (1), 32. 10.3390/ijerph19010032 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ignasiak, Z., Sebastjan, A., Kaczorowska, A. & Skrzek, A. Estimation of the risk of the frailty syndrome in the independent-living population of older people. Aging Clin. Exp. Res.32 (11), 2233–2240 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Krauze, T. et al. Grip strength is associated with markers of central hemodynamics. Scan Cardiovasc. J.54 (4), 248–252 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Fugiel, J., Ignasiak, Z., Skrzek, A. & Sławińska, T. Evaluation of relationships between Menopause Onset Age and Bone Mineral density and muscle strength in women from South-Western Poland. BioMed. Res. Int. 5410253. 10.1155/2020/5410253 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 32.Zasadzka, E., Pieczyńska, A., Trzmiel, T., Kleka, P. & Pawlaczyk, M. Correlation between Handgrip Strength and Depression in older Adults-A systematic review and a Meta-analysis. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health. 18 (9), 4823. 10.3390/ijerph18094823 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Osiński, W. Antropomotoryka (AWF Poznań, 2003). [Google Scholar]

- 34.Skevington, S. M., Lotfy, M., O’Connell, K. A. & WHOQOL Group The World Health. Organization’s WHOQOL-BREF quality of life assessment: psychometric properties and results of the international field trial. A report from the WHOQOL group. Qual. Life Res.13 (2), 299–310 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Jaracz, K. WHOQOL-BREF. Klucz. In Jakość życia w Naukach Medycznych (ed Wołowicka, J.) 276–280 (Akademia Medyczna im. Karola Marcinkowskiego w Poznaniu (2001). [Google Scholar]

- 36.Trampisch, U. S., Franke, J., Jedamzik, N., Hinrichs, T. & Platen, P. Optimal Jamar dynamometer handle position to assess maximal isometric hand grip strength in epidemiological studies. J. Hand Surg. Am.37 (11), 2368–2373 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Beaudart, C. et al. Assessment of muscle function and physical performance in Daily Clinical Practice: a position paper endorsed by the European Society for Clinical and Economic Aspects of Osteoporosis, Osteoarthritis and Musculoskeletal diseases (ESCEO). Calcif Tissue Int.105 (1), 1–14 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kołodziej, M., Sebastjan, A. & Ignasiak, Z. Appendicular skeletal muscle mass and quality estimated by bioelectrical impedance analysis in the assessment of frailty syndrome risk in older individuals. Aging Clin. Exp. Res.34 (9), 2081–2088 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.MacAuley, D. The potential benefit of physical activity in older people. Med. Sport. 5 (4), 229–236 (2001). [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kaczorowska, A. G., Fortuna, M., Katan, A., Kaczorowska, A. J. & Ignasiak, Z. Functional physical fitness and Anthropometric Characteristics of Older Women Living in different environments in Southwest Poland. Ageing Int.48, 367–383 (2023). [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kaczorowska, A. et al. Assessment of Physical Fitness and Risk factors for the occurrence of the Frailty Syndrome among Social Welfare Homes’ residents over 60 years of age in Poland. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health. 19 (12), 7449. 10.3390/ijerph19127449 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Skrzek, A. et al. Structural and functional markers of health depending on lifestyle in elderly women from Poland. Clin. Interv Aging. 10, 781–792 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Bhasin, S. et al. Sarcopenia Definition: the position statements of the Sarcopenia Definition and Outcomes Consortium. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc.68 (7), 1410–1418 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Baek, W. et al. Impact of activity limitations due to fear of falling on changes in frailty in Korean older adults: a longitudinal study. Sci. Rep.14, 19121. 10.1038/s41598-024-69930-2 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.McNicholl, T. et al. Handgrip strength predicts length of stay and quality of life in and out of hospital. Clin. Nutr.39 (8), 2501–2509 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Grassi, L. et al. Quality of life, level of functioning, and its relationship with mental and physical disorders in the elderly: results from the MentDis_ICF65 + study. Health Qual. Life Outcomes. 18 (1), 61. 10.1186/s12955-020-01310-6 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Schmidt, T., Christiansen, L. B., Schipperijn, J. & Cerin, E. Social network characteristics as correlates and moderators of older adults’ quality of life-the SHARE study. Eur. J. Public. Health. 31 (3), 541–547 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kaczorowska, A. et al. Functional capacity and risk of frailty syndrome in 85-year-old and older women living in nursing homes in Poland. Anthropol. Rev.84 (4), 395–404 (2021). [Google Scholar]

- 49.Suetta, C. et al. The Copenhagen Sarcopenia Study: lean mass, strength, power, and physical function in a Danish cohort aged 20–93 years. J. Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle. 10 (6), 1316–1329 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Cooper, R. et al. Between-study differences in grip strength: a comparison of Norwegian and Russian adults aged 40–69 years. J. Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle. 12 (6), 2091–2100 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request. Contact details: Antonina Kaczorowska, University of Opole, Institute of Health Sciences, email: antonina.kaczorowska@uni.opole.pl.