Abstract

With ongoing social progress, three-dimensional (3D) video is becoming increasingly prevalent in everyday life. As a key component of 3D video technology, depth video plays a crucial role by providing information about the distance and spatial distribution of objects within a scene. This study focuses on deep video encoding and proposes an efficient encoding method that integrates the Convolutional Neural Network (CNN) with a hyperautomation mechanism. First, an overview of the principles underlying CNNs and the concept of hyperautomation is presented, and the application of CNNs in the intra-frame prediction module of video encoding is explored. By incorporating the hyperautomation mechanism, this study emphasizes the potential of Artificial Intelligence to enhance encoding efficiency. Next, a CNN-based method for variable-resolution intra-frame prediction of depth video is proposed. This method utilizes a multi-level feature fusion network to reconstruct coding units. The effectiveness of the proposed variable-resolution coding technique is then evaluated by comparing its performance against the original method on the high-efficiency video coding (HEVC) test platform. The results demonstrate that, compared to the original test platform method (HTM-16.2), the proposed method achieves an average Bjøntegaard delta bit rate (BDBR) savings of 8.12% across all tested video sequences. This indicates a significant improvement in coding efficiency. Furthermore, the viewpoint BDBR loss of the variable-resolution coding method is only 0.15%, which falls within an acceptable margin of error. This suggests that the method is both stable and reliable in viewpoint coding, and it performs well across a broad range of quantization parameter settings. Additionally, compared to other encoding methods, the proposed approach exhibits superior peak signal-to-noise ratio, structural similarity index, and perceptual quality metrics. This study introduces a novel and efficient approach to 3D video compression, and the integration of CNNs with hyperautomation provides valuable insights for future innovations in video encoding.

Keywords: Variable resolution, Convolutional Neural Network, Depth video, Video coding efficiency, Hyperautomation mechanism

Subject terms: Mathematics and computing, Applied mathematics, Computational science, Computer science, Information technology, Pure mathematics, Scientific data, Software, Statistics

Introduction

To enhance the storage and transmission of video content, video compression technology has emerged as an indispensable tool across a range of applications, including digital television, video surveillance, wireless mobile video calls, and remote video conferencing. Contemporary video compression primarily employs hybrid coding frameworks, which integrate key modules such as pixel-domain intra-prediction, inter-prediction, transformation, and entropy coding. These techniques underpin widely adopted video formats, such as H.264 and H.2651,2. Despite their success in compressing two-dimensional (2D) video, there remains significant potential for improving the compression of depth videos and three-dimensional (3D) videos, particularly in scenarios involving high resolutions or multiple viewpoints. Depth video, a format encapsulating depth information, has gained considerable traction in recent years across domains such as virtual reality (VR), augmented reality (AR), video surveillance, autonomous driving, and medical imaging. It exhibits distinct characteristics, including low texture complexity, high spatial redundancy, low noise sensitivity, and pronounced differences between high- and low-frequency features. Unlike conventional 2D video, depth video employs depth maps to capture the 3D structure of a scene. While this capability enables a richer visual experience, it also introduces challenges related to the substantial data volume and the demands of storage and transmission. Consequently, the efficient compression of depth video has become a critical research focus. In contrast to traditional video encoding techniques, emerging frameworks leveraging Artificial Intelligence (AI) and Deep Learning—commonly referred to as learning-based or end-to-end encoding methods—offer enhanced flexibility and efficiency. Recent advances in AI and Deep Learning algorithms enable video compression to move beyond the direct processing of image pixels. These methods allow for the extraction and learning of intricate features and patterns within video content, facilitating more precise and effective compression solutions. Learning-based approaches thus provide a robust foundation for depth video compression, enhancing both the efficiency of compression and the quality of the resultant videos. Concurrently, 3D video technologies have witnessed considerable progress. A notable innovation in this domain is Multiview Video plus Depth, a format that enables the generation of intermediate viewpoints between existing camera perspectives using depth map-based virtual viewpoint rendering. This capability significantly expands the utility of 3D video. The latest standard in 3D video encoding, 3D High Efficiency Video Coding (3D-HEVC), has become the preferred solution for storing and transmitting 3D video under constraints of limited storage capacity and restricted network bandwidth3. Nevertheless, the substantial data demands of 3D video continue to present formidable challenges in terms of both transmission and storage. Addressing these challenges through the development of efficient 3D video compression methods holds significant practical importance. Recent advancements in AI technology and Deep Learning have further introduced the concept of hyperautomation to video compression, aiming to optimize efficiency and quality. Hyperautomation combines automation, AI, and machine learning (ML) to automate various stages of the video compression process, including intra-frame prediction, inter-frame prediction, transformation, and the optimization of entropy coding modules. Furthermore, hyperautomation enables the dynamic fine-tuning of video compression parameters, yielding more efficient compression outcomes. Consequently, the integration of hyperautomation into video compression technologies is expected to enhance both the efficiency and quality of 3D video compression, thereby providing more effective solutions to the challenges associated with 3D video transmission and storage.

With the rapid advancement of Deep Learning technology, its applications have achieved remarkable progress across a wide range of domains. In particular, Convolutional Neural Network (CNN) has demonstrated exceptional learning capabilities in areas such as computer vision, speech recognition, and natural language processing (NLP), significantly enhancing task performance. For instance, Altaheri et al. (2023) proposed a dynamic attention temporal convolutional network for decoding motor imagery signals from electroencephalogram (EEG) data. By incorporating dynamic convolution and multi-level attention mechanisms, the model demonstrated improved classification performance, achieving independent subject accuracy of 71.3% and dependent subject accuracy of 87.08% on brain-computer interface competition datasets4. Similarly, Li et al. (2024) introduced a hybrid architecture combining CNNs and Bidirectional Long Short-Term Memory (BiLSTM) networks for EEG motor imagery decoding. By employing an attention mechanism to enhance the weighting of key features, the model achieved substantial improvements in classification accuracy5. In the field of circuit design, Sun et al. (2024) developed a memristor-based associative memory neural network circuit that addressed masking effects and emotional consistency. This circuit featured modules for emotion, memory, inhibition, and feedback, enabling masking and recovery under varying emotional states, with potential applications in bionic emotional robots and brain-inspired systems6. Additionally, Sun et al. (2024) proposed a multi-input operant conditioning neural network that incorporated blocking and competition effects to enable efficient learning in multi-input environments. The network utilized functions such as signal time difference, random exploration, and feedback learning, and was validated through simulations, providing valuable insights for hardware implementations of AI7.

The application of Deep Learning in these diverse domains underscores its robust data processing and feature extraction capabilities, offering valuable reference points for further research. For example, Zhang et al. (2023) introduced a predictive and adaptive deep encoding framework to optimize bitrate allocation in wireless image transmission, thereby enhancing bandwidth efficiency8. Similarly, Esakki et al. (2021) proposed an adaptive video encoding method that jointly optimized video quality, bitrate requirements, and encoding speed as part of a multi-objective optimization process, surpassing traditional bandwidth control techniques9. Recent years have also seen the increasing adoption of Deep Learning methods in depth video encoding, a critical data compression technology aimed at improving encoding efficiency. Traditional depth video encoding approaches primarily relied on content analysis and model-based techniques. However, with the integration of Deep Learning, research has shifted toward learning-based strategies to further enhance encoding performance. Lei et al. (2019) were the first to introduce CNNs into 3D-HEVC depth map coding. They proposed a dual-channel CNN architecture that utilized texture image information to aid in encoding depth maps. Their approach involved down-sampling depth maps before encoding and up-sampling them afterward to reconstruct the original maps, achieving an average rate-distortion improvement of 9.1%10. More recently, Hu et al. (2022) proposed a coarse-to-fine depth video compression framework that optimized motion compensation and introduced two mode prediction methods based on hyper-prior information. This framework improved the efficiency of motion and residual encoding and demonstrated state-of-the-art performance across multiple datasets without incurring additional bitrate costs or computational overhead11. These studies underscore the immense potential of Deep Learning in advancing the efficiency of depth video encoding, offering valuable technical insights for ongoing research. Building on these advancements, this study explores how Deep Learning methods can be further harnessed to optimize depth video encoding systems, addressing the growing demands for efficient video data storage and transmission.

Building on the aforementioned background, this study is motivated by the pressing challenges associated with the transmission and storage of 3D video content. Despite recent advancements in AI and Deep Learning technologies, existing methods for video coding, particularly for depth video, have yet to fully capitalize on the potential of these technologies. Consequently, this study seeks to optimize and enhance the efficiency and quality of depth video coding by integrating advanced AI techniques, specifically CNN, with hyperautomation mechanisms. The principal contribution of this study lies in the development and validation of an innovative depth video encoding method that synergizes CNNs with a hyperautomation framework. A novel variable-resolution intra-prediction encoding approach for depth videos is proposed, which employs a multi-level feature fusion network to reconstruct coding units. This design significantly improves the efficiency and quality of depth video encoding. The key contributions of this study are as follows:

Development of a CNN-Based Variable-Resolution Intra-Prediction Encoding Method: A novel depth video encoding approach is proposed and validated, enabling the optimization of the encoding process through dynamic resolution adjustment.

Integration of AI with Hyperautomation Mechanisms: Advanced AI technologies are combined with a hyperautomation framework to construct an intelligent encoding workflow, thereby enhancing the overall encoding efficiency.

Experimental Validation on a Robust Encoding Test Platform: Comparative experiments conducted on an efficient video encoding test platform demonstrate the superior performance of the proposed method in depth video encoding. The experimental results show an average Bjøntegaard Delta Bit Rate (BDBR) savings of 8.12% across all test sequences, with viewpoint encoding BDBR losses controlled within a reasonable range of 0.15%.

The experimental findings confirm that the proposed method outperforms traditional encoding techniques in terms of both encoding efficiency and video quality. Notably, significant improvements are observed in peak signal-to-noise ratio (PSNR) and structural similarity index measure (SSIM). By integrating CNNs with hyperautomation mechanisms, this study presents an innovative approach to efficient 3D video compression and marks a significant step forward in the development of depth video encoding technologies. Compared to other feature-fusion-based intra-prediction methods, the proposed CNN-based variable-resolution encoding framework and multi-level feature fusion network stand out by effectively leveraging the unique properties of depth videos. Through the innovative application of variable resolution, residual learning, and adaptive feature fusion mechanisms, the proposed method achieves more efficient intra-prediction encoding for depth videos. This approach not only enhances encoding efficiency but also demonstrates exceptional adaptability, offering a robust solution to the challenges of modern 3D video compression.

This study is organized into four sections. Section "Introduction" provides an introduction, outlining the background, objectives, methodology, and overall framework. Section "Research on intra-prediction coding of deep video based on CNN" presents the methodology and theoretical foundations, where a CNN-based video coding technique is explored through theoretical analysis of hyperautomation and CNN. Additionally, a deep video variable resolution intra-frame prediction coding method based on CNN is proposed. Section "Experiment and result analysis" focuses on the experimental performance evaluation, where comparative experiments on a high-efficiency video coding (HEVC) testing platform are conducted to validate the effectiveness of the proposed deep video variable resolution coding method. Finally, Sect. "Conclusion" offers a conclusion, summarizing the key findings of the study, highlighting its limitations, and providing suggestions and directions for future development.

Research on intra-prediction coding of deep video baseD ON CNN

Fundamentals of hyperautomation and CNN technology

Hyperautomation represents a comprehensive automation paradigm that integrates a range of advanced technologies, including AI, ML, NLP, machine vision, and process automation, to enable more efficient and intelligent business process automation. Its primary objectives are to optimize workflows, enhance productivity and quality, and reduce operational costs and risks12. Within the hyperautomation framework, these technologies collaborate synergistically to streamline workflows and improve decision-making processes. The hyperautomation process is typically implemented through the following steps:

Automated Data Analysis: AI and ML algorithms are employed to analyze data, uncovering patterns and trends within the system.

Natural Language Processing: NLP enables the system to comprehend and process human language, facilitating automated handling and interaction with textual data.

Machine Vision: This technology identifies critical information within video and image data, supporting informed decision-making.

Process Integration and Workflow Optimization: Process automation and workflow technologies integrate these intelligent capabilities into specific business operations, enabling real-time task execution and process optimization.

In hyperautomation systems, ML and Deep Learning algorithms continuously learn and adapt by extracting features and refining models from large datasets. In the domain of video encoding, hyperautomation primarily manifests through the automated extraction and compression of video image features using Deep Learning networks. This approach addresses the inherent limitations of traditional video encoding methods, which rely heavily on manually designed feature extraction and compression algorithms. Such rule-based algorithms often struggle to fully capture the complex information embedded in video data, leading to suboptimal encoding efficiency. Hyperautomation, in contrast, leverages ML to automatically learn the intrinsic structures and patterns within video data, facilitating smarter video encoding. This results in enhanced encoding efficiency and video quality. For instance, deep neural networks can dynamically distinguish between high-frequency details and low-frequency information in videos. Moreover, these networks can adaptively select the most appropriate compression strategies based on the specific characteristics of scenes and video content, optimizing both compression rates and video quality. This capability underscores the transformative potential of hyperautomation in advancing the field of video encoding.

The application of hyperautomation technology in video encoding significantly enhances both efficiency and quality. Traditional video encoding methods rely on the manual design and fine-tuning of algorithms, which can be both time-intensive and laborious. Given the vast and complex nature of video datasets, fully exploiting the latent features of such data through manual approaches is inherently challenging. Hyperautomation addresses this limitation by integrating AI with automated processes, enabling the system to automatically learn and adapt to diverse video data types, thereby facilitating more intelligent and adaptive compression techniques. Hyperautomation can be utilized in various stages of video encoding13. First, it enables the automatic optimization of key stages in the encoding process, including intra-frame prediction, inter-frame prediction, transformation, and entropy coding. By leveraging ML algorithms, hyperautomation analyzes the interrelationships among these modules and determines optimal parameter configurations, resulting in improved encoding efficiency and output quality. Additionally, hyperautomation dynamically adjusts video encoding parameters to meet the specific requirements of different scenarios, ensuring optimal performance under varying compression demands.

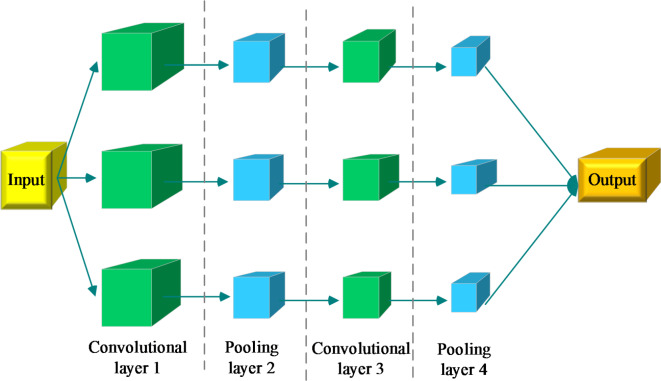

Artificial Neural Network (ANN) provides a foundational technology for hyperautomation, inspired by the structure of biological neural networks. An ANN consists of a nonlinear framework composed of numerous interconnected processing elements, learning features through loss functions to interpret input data. A CNN represents a specialized type of ANN particularly effective for image processing tasks. In CNNs, a single neuron can connect to multiple neurons within its receptive field, enabling weight sharing and reducing computational complexity14. Unlike fully connected networks, the neurons in a CNN’s hidden layers are connected to only a subset of nodes in the preceding layer, defined by the size of the receptive field n. This structure reduces the number of parameters, mitigates the risk of overfitting, and ensures translation invariance. LeNet, one of the earliest CNN architectures, was introduced in 1998 for digital character recognition. However, CNNs gained significant attention in 2012 with their application to image classification tasks. Today, image classification remains one of the most prevalent applications of CNNs, particularly facilitated by Graphics Processing Units (GPUs). The computational speed of GPUs allows for efficient training and testing of models on large-scale datasets. Figure 1 illustrates the architecture of a CNN, highlighting its layered structure and the key principles underlying its operation.

Fig. 1.

Schematic diagram of CNN structure.

Figure 1 illustrates the fundamental structure of a CNN, comprising the input layer, convolutional layers, pooling layers, and output layer15. The first convolutional layer is generated by applying a convolution operation between the input image and a convolutional kernel. Subsequently, the pixel values of each feature map in the first convolutional layer are sampled to produce the first pooling layer. This process of convolution and pooling is repeated, yielding subsequent layers, including the third convolutional layer and the fourth pooling layer. Finally, the feature map from the fourth pooling layer is connected to the output layer through a fully connected layer, forming a feature vector for classification or prediction. The convolutional layers are integral to extracting local features by applying the convolutional kernel to the receptive field of the feature map in the preceding layer16. This operation involves performing a convolution between the kernel and the input feature map, adding an offset term, and applying a nonlinear activation function (commonly ReLU) to generate the feature map for the current layer. The operation of a convolutional layer is described in Eq. (1):

|

1 |

l denotes the convolutional layer index,  is the nonlinear activation function (typically ReLU),

is the nonlinear activation function (typically ReLU),  is the b-th feature map in layer l,

is the b-th feature map in layer l,  is the convolutional kernel,

is the convolutional kernel,  represents the set of input feature maps, and

represents the set of input feature maps, and  is the offset term. Following the convolutional layers, pooling layers are generated to perform downsampling of the feature maps, reducing spatial dimensions and computational complexity while retaining significant features. The operation of a pooling layer is described by Eq. (2):

is the offset term. Following the convolutional layers, pooling layers are generated to perform downsampling of the feature maps, reducing spatial dimensions and computational complexity while retaining significant features. The operation of a pooling layer is described by Eq. (2):

|

2 |

represents the downsampled value, and down(*) is the subsampling function17. The fully connected layer integrates the extracted feature maps into a single feature vector, which is then passed to a classifier, such as a softmax function, for classification tasks18. CNNs are widely utilized in various fields, including computer vision, pattern recognition, and image and video processing. Their effectiveness has been enhanced by advancements in GPU and CPU computational power, the adoption of optimization techniques such as rectified linear units, and the availability of extensive training datasets. As a result, CNNs are increasingly capable of addressing complex problems.

represents the downsampled value, and down(*) is the subsampling function17. The fully connected layer integrates the extracted feature maps into a single feature vector, which is then passed to a classifier, such as a softmax function, for classification tasks18. CNNs are widely utilized in various fields, including computer vision, pattern recognition, and image and video processing. Their effectiveness has been enhanced by advancements in GPU and CPU computational power, the adoption of optimization techniques such as rectified linear units, and the availability of extensive training datasets. As a result, CNNs are increasingly capable of addressing complex problems.

Video coding technology based on CNN

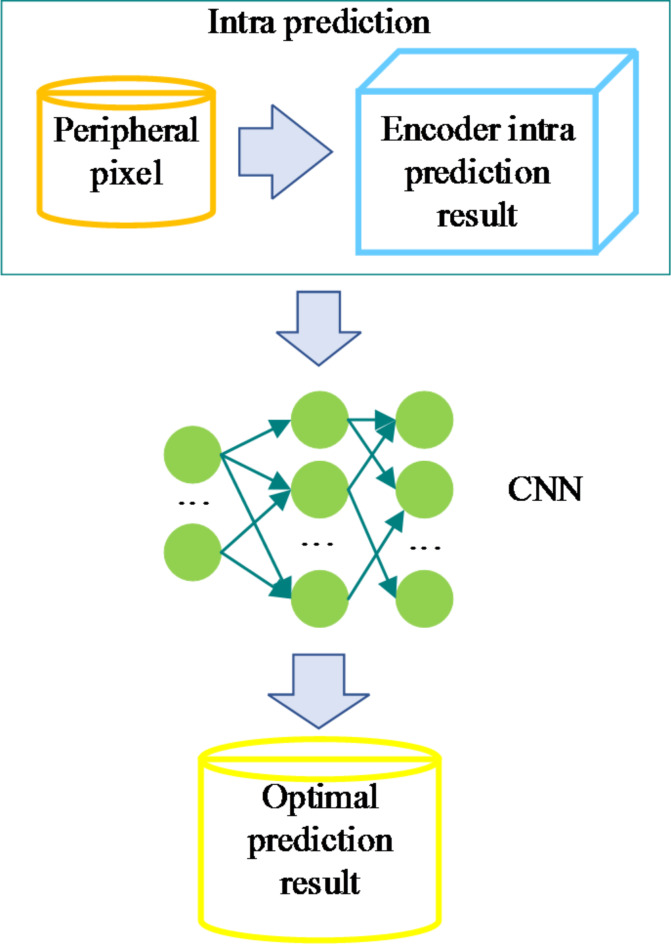

Video coding encompasses several key modules, including intra-prediction and inter-prediction. This section focuses on CNN-based intra-prediction. Two primary approaches are employed for applying CNNs to intra-prediction: (1) learning the mapping from the prediction block to the original block and (2) learning the mapping from surrounding pixels to the original block19. In the first approach, CNNs are trained to predict the mapping from the prediction block to the original block. Figure 2 illustrates the underlying principle of this method, showcasing how the network learns to generate accurate intra-predictions by leveraging the structural and contextual information from input blocks.

Fig. 2.

Principle of predicting block to original block mapping using network learning.

In Fig. 2, the application of a CNN to learn the mapping from the prediction block to the original block is depicted. In this approach, the CNN is typically integrated into the encoder pipeline following the conventional intra-prediction stage. The encoder’s initial prediction output serves as the input to the CNN, which then refines and enhances the intra-prediction results20. To further improve compression efficiency for color videos, some researchers have introduced a multi-scale core CNN capable of recovering low-resolution encoded images with greater fidelity21. The second approach, illustrated in Fig. 3, leverages CNNs to learn the mapping from surrounding pixels to the original block.

Fig. 3.

Principle of learning the mapping between surrounding pixels and original blocks through the network.

The CNN directly utilizes the surrounding pixels as input to produce prediction results, effectively establishing a novel intra-prediction mode. During encoding, the encoder evaluates all available prediction modes, including those generated by CNN, and selects the optimal mode based on rate-distortion cost comparisons22. Expanding on this method, some studies have incorporated additional rows of peripheral pixels surrounding the prediction block into the network. By designing a more intricate fully connected network, these approaches aim to utilize more contextual pixel information to better capture the mapping relationship23.

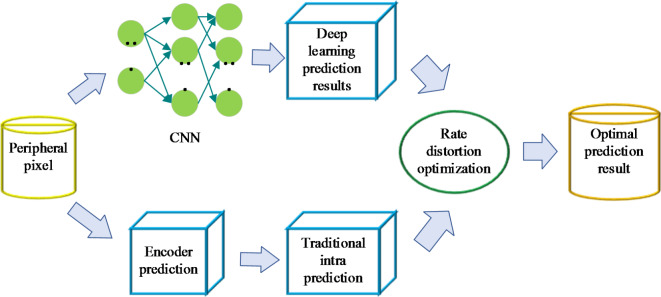

Variable resolution coding framework for depth video

In the context of depth videos, the term “depth” refers to the relative distance of objects in a scene from the camera or their positions in 3D space. Depth information provides a mechanism to represent spatial relationships among objects, facilitating realistic 3D perception and visual effects. Unlike traditional 2D videos, which capture only flat image data, depth videos encode depth values for each pixel, allowing for the reconstruction of 3D object shapes and spatial positions. This additional information enhances the visual experience by incorporating spatial awareness and stereoscopic effects, enabling viewers to better perceive object proximity and 3D contours. Such capabilities are particularly valuable for applications in VR, AR, 3D movies, and similar domains, where immersive and realistic user experiences are critical. Depth video technology acquires depth information through various methods, including binocular cameras, time-of-flight cameras, and structured light sensors. The depth data is then paired with corresponding color images to generate depth maps or depth video streams. A distinguishing characteristic of depth videos is the presence of extensive smooth regions with significant spatial redundancy. To improve compression efficiency, a common strategy involves reducing the resolution of the depth image prior to encoding and restoring it to its original resolution post-encoding24. Building on the proven advantages of variable resolution in color video coding, a CNN-based variable resolution intra-prediction coding method has been developed for depth videos. This method utilizes a multi-level feature fusion network to reconstruct high-quality depth video coding units. The proposed variable resolution coding framework is depicted in Fig. 4, showcasing its ability to enhance depth video compression by leveraging adaptive resolution adjustment and advanced feature integration techniques.

Fig. 4.

Variable resolution coding framework.

In each frame of the depth image, different coding blocks represent distinct depth information for various regions. Therefore, operations are performed at the level of the Local Control Unit (LCU)25. Let H(a, b) represent a frame image of the original depth video, which is divided into a series of non-adjacent LCUs:  . To achieve low-resolution coding, the resolution of each LCU must be reduced before encoding. This process involves using an interpolation filter to down-sample each LCU, reducing its size to half of the original resolution. The resulting LCU after sampling is denoted as:

. To achieve low-resolution coding, the resolution of each LCU must be reduced before encoding. This process involves using an interpolation filter to down-sample each LCU, reducing its size to half of the original resolution. The resulting LCU after sampling is denoted as:  . The pixel value after down-sampling is the weighted sum of the original surrounding pixels. Consequently, each LCU has two coding schemes: one is full-resolution prediction coding, which involves encoding the original resolution coding unit

. The pixel value after down-sampling is the weighted sum of the original surrounding pixels. Consequently, each LCU has two coding schemes: one is full-resolution prediction coding, which involves encoding the original resolution coding unit  , and the other is down-sampling and up-sampling variable-resolution prediction coding based on CNN. The new intra-frame encoding mode utilizing CNN, by incorporating deep learning models, can automatically learn and extract features from the data. Compared to traditional intra-frame prediction methods, this approach offers higher accuracy and better compression performance, particularly in capturing both spatial and depth features of images. CNN is particularly adept at adapting to changes in video content, especially in large smooth areas of depth videos. In these regions, CNN can make more effective predictions, reducing redundant data and enhancing compression efficiency. The down-sampled coding unit

, and the other is down-sampling and up-sampling variable-resolution prediction coding based on CNN. The new intra-frame encoding mode utilizing CNN, by incorporating deep learning models, can automatically learn and extract features from the data. Compared to traditional intra-frame prediction methods, this approach offers higher accuracy and better compression performance, particularly in capturing both spatial and depth features of images. CNN is particularly adept at adapting to changes in video content, especially in large smooth areas of depth videos. In these regions, CNN can make more effective predictions, reducing redundant data and enhancing compression efficiency. The down-sampled coding unit  is then encoded to obtain the low-resolution depth block

is then encoded to obtain the low-resolution depth block  . Down-sampling depth images effectively reduces the size of encoding units and the amount of data to be transmitted. By encoding these low-resolution depth blocks, the method reduces encoding complexity and computational overhead while maintaining image quality. Down-sampling minimizes redundant information and provides a more efficient encoding foundation for subsequent super-resolution reconstruction. A CNN is then employed for the super-resolution reconstruction of

. Down-sampling depth images effectively reduces the size of encoding units and the amount of data to be transmitted. By encoding these low-resolution depth blocks, the method reduces encoding complexity and computational overhead while maintaining image quality. Down-sampling minimizes redundant information and provides a more efficient encoding foundation for subsequent super-resolution reconstruction. A CNN is then employed for the super-resolution reconstruction of  , restoring the size of the depth block26–28. The two coding schemes are evaluated, and the best result is selected through rate-distortion optimization (RDO), which determines the final coding method for transmission. The use of the RDO mechanism to select the optimal scheme between CNN-based and traditional HEVC intra-modes enhances the intelligence and efficiency of the encoding process. Under certain conditions, RDO automatically selects the most suitable encoding mode, avoiding performance bottlenecks that may arise from relying on a single encoding mode. This mechanism enables dynamic adjustments during encoding, ensuring the selection of the optimal compression scheme and maximizing encoding performance.

, restoring the size of the depth block26–28. The two coding schemes are evaluated, and the best result is selected through rate-distortion optimization (RDO), which determines the final coding method for transmission. The use of the RDO mechanism to select the optimal scheme between CNN-based and traditional HEVC intra-modes enhances the intelligence and efficiency of the encoding process. Under certain conditions, RDO automatically selects the most suitable encoding mode, avoiding performance bottlenecks that may arise from relying on a single encoding mode. This mechanism enables dynamic adjustments during encoding, ensuring the selection of the optimal compression scheme and maximizing encoding performance.

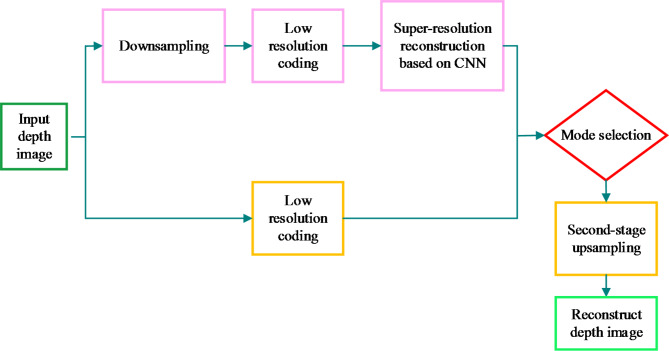

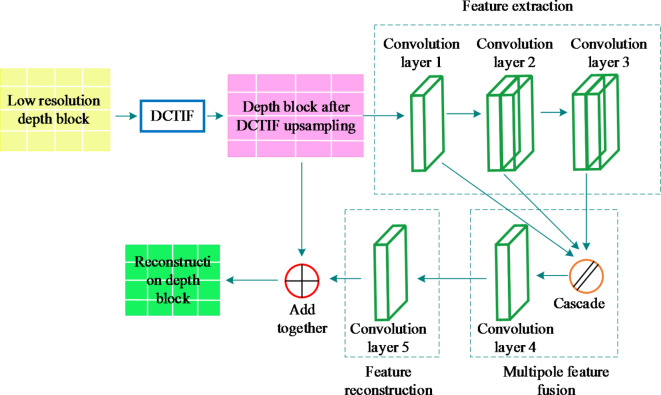

The depth maps in depth videos often exhibit strong spatial local correlations, where the depth value differences between adjacent pixels are minimal, particularly in background regions or for distant objects. To address this characteristic, the network design incorporates local receptive field convolution operations, enabling the CNN to efficiently capture depth variations within local regions and effectively compress redundant data. The depth information in depth videos is often sparse within a certain range, meaning that some areas show minimal depth variation, leading to a large amount of redundant data. Therefore, the encoding process is specially designed with a multi-level feature fusion mechanism. By fusing features at different scales, this approach further reduces redundant information and enhances compression efficiency. This method ensures that the precision of depth information is not overly compromised during compression, especially in areas where detailed information is crucial. In certain application scenarios, different regions of the depth video require varying levels of detail. Near objects typically require higher encoding precision, while depth information for distant or static background regions changes minimally, and thus requires lower encoding precision. Based on this characteristic, a variable resolution encoding method is proposed. By dynamically adjusting the encoding resolution, different encoding precision levels are applied to different regions, thereby improving overall encoding efficiency. In this process, the details of the depth information are effectively preserved, and a high compression ratio is achieved without compromising visual quality. For 3D videos and depth videos, the precision of viewpoint synthesis and 3D reconstruction is critical. To ensure that the accuracy of depth information is not compromised during compression for viewpoint synthesis, this study designs a multi-level feature fusion network specifically for depth videos. Through multi-level feature fusion, depth information is effectively retained, and the compression efficiency of viewpoint synthesis is significantly improved during the encoding process. The super-resolution reconstruction of the encoded low-resolution depth block is performed using a CNN with five layers. The network structure includes feature extraction, multi-level feature fusion, and feature reconstruction. Figure 5 illustrates the network architecture29.

Fig. 5.

Multi-level feature fusion network.

The first part of the process is feature extraction. Multi-scale feature extraction transforms the input depth block from the image domain to the feature domain, capturing the necessary information for subsequent reconstruction. Before the low-resolution block is input into the network, its size is first restored to the original dimensions using a Discrete Cosine Interpolation Filter (DCTIF)30,31. DCTIF is an effective interpolation method widely used in image and signal processing tasks. During the upsampling process, it helps preserve key information from the original low-resolution block, thus enabling a more accurate reconstruction of the high-resolution block. This is critical for image restoration tasks, where the objective is to enhance the resolution while retaining essential details. A notable advantage of DCTIF in upsampling is its ability to reduce the generation of artifacts. Artifacts refer to unnatural distortions that may arise during image or signal restoration, potentially degrading image quality. By utilizing DCTIF, the generation of such artifacts is significantly minimized, leading to a more natural and authentic reconstructed high-resolution block. Choosing an interpolation method that aligns with the characteristics of the task at hand is essential for optimal restoration. DCTIF performs exceptionally well in restoring depth block images because it effectively addresses the frequency domain characteristics of signals, making it suitable for various data types, such as audio and images. Consequently, DCTIF’s ability to preserve critical information, reduce artifact generation, and adapt to specific task characteristics makes it a favorable choice for upsampling, resulting in enhanced reconstruction outcomes and superior image restoration quality. Meanwhile, super-resolution techniques are employed for upsampling. These techniques, which leverage CNNs to reconstruct low-resolution images, restore the original size of the depth video while retaining as much image detail as possible. Through multi-level feature fusion and precise feature reconstruction, super-resolution not only improves video quality but also reduces the data volume required for transmission. The feature extraction process comprises three convolutional layers. Each convolutional layer is followed by an activation layer to enhance the network’s nonlinear expression capabilities. Additionally, a max-pooling layer is used to further reduce the size of the feature maps. The max-pooling layer employs a 2 × 2 window size and a stride of 2. It aggregates the output from the previous convolutional layer and selects the maximum value within each window as the pooled value. This approach helps preserve the primary features of the image while also decreasing computational load. The kernel size of the first convolutional layer is 5 × 5, with a feature dimension of 64. The layer’s expression can be written as:

|

3 |

is the output characteristic of the first convolutional layer,

is the output characteristic of the first convolutional layer,  is the weight of the first convolution layer, and

is the weight of the first convolution layer, and  is the offset.

is the offset.  is the low-resolution depth block after the size is restored by DCTIF, and * is the convolution operation. In the second convolutional layer, two types of convolution kernels are used. The size of these two types of convolution kernels is 3 × 3 and 5 × 5. The feature dimensions are 32 and 16, respectively, which can be expressed as:

is the low-resolution depth block after the size is restored by DCTIF, and * is the convolution operation. In the second convolutional layer, two types of convolution kernels are used. The size of these two types of convolution kernels is 3 × 3 and 5 × 5. The feature dimensions are 32 and 16, respectively, which can be expressed as:

|

4 |

is the output of the second convolutional layer, which is obtained by concatenation of two convolution results

is the output of the second convolutional layer, which is obtained by concatenation of two convolution results  and

and  .

.  and

and  are weights.

are weights.  and

and  are the biases. The third convolutional layer is similar to the second layer, and also has the characteristics of a multi-scale convolution kernel. The convolution kernel size is 3 × 3 and 1 × 1. The feature dimension is 16 and 32, respectively, and the expression reads:

are the biases. The third convolutional layer is similar to the second layer, and also has the characteristics of a multi-scale convolution kernel. The convolution kernel size is 3 × 3 and 1 × 1. The feature dimension is 16 and 32, respectively, and the expression reads:

|

5 |

is the output of the third convolutional layer, obtained by concatenating the results of two types of convolutions,

is the output of the third convolutional layer, obtained by concatenating the results of two types of convolutions,  and

and  .

.  and

and  are the weights, while

are the weights, while  and

and  are the biases.

are the biases.

The second part of the process is multi-level feature fusion. In a CNN, lower-level features primarily capture the low-frequency information in an image, while higher-level features retain the high-frequency details. To ensure that the features extracted by the higher-level convolution layers effectively capture both high-frequency details and low-frequency information, a further fusion of the features obtained from the initial three convolutional layers is performed. This fusion process involves two distinct steps. First, the features extracted from the initial three layers are concatenated to form new composite features. Then, convolution is applied to these composite features to generate the newly fused features32. The convolution kernel size used in the multi-level feature fusion is 3 × 3, with a feature dimension of 48. The fusion of lower-level features can be expressed as:

|

6 |

is a cascade operation, and

is a cascade operation, and  is the output after feature fusion.

is the output after feature fusion.  and

and  are the weights and biases, respectively.

are the weights and biases, respectively.

The third part is feature reconstruction. This stage is responsible for generating the reconstructed feature map from the network33. To achieve this, a convolutional layer with a feature dimension of 1 and a feature core size of 1 × 1 is adopted. This layer processes the features from the preceding layer, effectively reducing the feature dimension. The expression is:

|

7 |

is the output of feature reconstruction.

is the output of feature reconstruction.  and

and  are the weights and biases, respectively. Besides, a global residual learning structure is utilized to enable the network to learn the residual values of the features, enhancing convergence during training. This approach involves adding the input block of the network to the output of the multi-level feature fusion. The final output is the reconstructed block at the original resolution. The residual learning process can be expressed as:

are the weights and biases, respectively. Besides, a global residual learning structure is utilized to enable the network to learn the residual values of the features, enhancing convergence during training. This approach involves adding the input block of the network to the output of the multi-level feature fusion. The final output is the reconstructed block at the original resolution. The residual learning process can be expressed as:

|

8 |

S is the final reconstruction depth block.

To further enhance the performance of network reconstruction, a second up-sampling process is introduced. During low-resolution coding, the encoder performs block-by-block encoding based on a Z-type structure. As a result, only the pixel values from the left and upper sides of the current block are available for prediction, since the regions on the right and lower sides have not yet been predicted. The second up-sampling occurs immediately after the first, allowing more peripheral region information to be utilized for reference once the coding blocks in the current frame have completed their predictions34. In the initial up-sampling, all depth blocks selected in the variable resolution prediction mode undergo a second up-sampling. The second up-sampling employs the same network as the first, with the input block size set to 128 × 128 to encompass a larger set of peripheral pixels.

Additionally, the models described above incorporate a hyperautomation mechanism that enhances this CNN-based encoding method through automated process management and real-time optimization. Specifically, during model training, the hyperautomation mechanism automatically manages and adjusts the network’s training parameters. It fine-tunes hyperparameters such as the learning rate and batch size at various stages of training and dynamically selects the most suitable optimization algorithms based on real-time training outcomes. This ensures the network remains in an optimal state throughout the training process, leading to faster convergence and reducing the risk of overfitting. The automated optimization process minimizes the need for manual intervention, improving both training efficiency and accuracy. During the video encoding process, the hyperautomation mechanism continuously monitors the encoding performance and automatically updates the model in response to changes observed during encoding. For instance, when processing depth videos of varying resolutions, the hyperautomation system automatically selects the CNN model architecture best suited to the characteristics of the current video and dynamically adjusts the model’s parameter configuration during encoding. This adaptability enhances the flexibility of the encoding process. In the encoding phase, the hyperautomation mechanism autonomously coordinates the operations of various modules, including feature extraction, multi-level feature fusion, and feature reconstruction. During multi-level feature fusion, the hyperautomation mechanism determines which features are most crucial for the final image reconstruction and selectively integrates them. This automated decision-making process improves encoding efficiency and ensures higher quality in the reconstructed images. During the post-encoding quality assessment and adjustment phase, the hyperautomation mechanism automatically adjusts subsequent encoding parameters by analyzing real-time quality metrics of the encoded video. If the system detects that the encoding quality does not meet the expected standards, it automatically modifies critical parameters—such as convolution kernel size and the number of feature layers—and re-encodes the video to ensure the output quality meets the required specifications. Through these applications, the hyperautomation mechanism significantly improves both the efficiency and quality of the CNN-based encoding method. It makes the encoding process more intelligent and automated, effectively addressing the challenges of 3D video transmission and storage.

To effectively mitigate potential overfitting issues in the model, the following strategies are employed: (1) Data Augmentation: During the training process, data augmentation is used to increase the diversity of the training samples. This technique involves random cropping, flipping, and rotation to generate a variety of samples. This preprocessing step helps prevent the model from overfitting to specific features of the training data, thereby enhancing the model’s generalization ability. (2) Regularization: Given the deep structure of CNN, regularization methods are incorporated between network layers, including L2 regularization and Dropout layers, to reduce the risk of overfitting. L2 regularization penalizes large weight coefficients, ensuring smoother model parameter updates that are less dependent on specific training data. Dropout layers randomly ignore the output of certain neurons, simulating an ensemble effect and reducing model complexity, which improves the model’s adaptability to unseen data. (3) Adaptive Hyperautomation Optimization: An adaptive hyperautomation optimization mechanism is employed during training to dynamically adjust training parameters and mitigate overfitting. The hyperautomation system monitors the loss function in real-time and automatically selects appropriate learning rate decay strategies based on the training stage. This ensures smooth convergence and avoids fluctuations caused by excessive parameter adjustments. (4) Early Stopping: To prevent overfitting during training, an early stopping strategy is used. When performance on the validation set stops improving after a specified number of epochs, training is automatically halted. This ensures that the model terminates at its optimal performance, preventing overtraining and degradation of its generalization ability. Through these methods, the deep learning model improves video encoding efficiency while effectively reducing the risk of overfitting, thereby enhancing its robustness and reliability in real-world applications.

Finally, multiple strategies are employed in the network design to balance time consumption and network efficiency, ensuring that the network maintains high encoding performance without significantly increasing computational burden. First, a variable resolution encoding framework is used, where depth video is downsampled during encoding and then restored through super-resolution at the decoder end. This approach reduces the amount of data processed during encoding, thereby lowering computation time. Additionally, during feature extraction, multi-scale convolution kernels are used for parallel computation, enhancing feature capture efficiency while controlling the number of network layers and the size of convolution kernels to reduce computational complexity. Furthermore, during network optimization, the RDO mechanism is introduced to dynamically select between CNN-based and traditional HEVC intra-prediction modes. This optimizes time consumption by controlling the frequency of complex encoding module applications. Lastly, during training, the hyperautomation tuning mechanism automatically adjusts the learning rate and batch size based on real-time performance, ensuring that the network converges quickly while meeting accuracy requirements. Together, these strategies achieve a balance between compression efficiency and time cost, providing a feasible solution for the real-time application of 3D depth video encoding.

Experiment and result analysis

Experimental dataset and configuration

The proposed intra-prediction coding method is integrated into the reference test platform HTM-16.2 of the 3D-HEVC standard for testing depth video. The Deep Learning platform Caffe is embedded within HTM-16.2 to support the various operations required by the CNN. Testing is conducted with the quantization parameters for the 3D video standard set as {(25, 34), (30, 39), (35, 42), (40, 45)}. The remaining coding configuration parameters, including Max CU Width, Max CU Height, Max Partition Depth, and GOPSize, are set to 64, 64, 4, and 1, respectively. The performance evaluation is based on the BDBR, a commonly used metric to assess bitrate savings. BDBR allows for comparisons of compression performance between different encoders, while maintaining the same image quality. A negative BDBR value indicates that the proposed method achieves a lower bitrate than traditional methods at the same PSNR, thereby demonstrating higher compression efficiency. The BDBR savings rate is used to quantify the performance improvement of the proposed method over traditional approaches across different test sequences. The unmodified HTM-16.2 platform serves as the baseline algorithm for comparison with the proposed method. The experiments are conducted on a Windows system with Microsoft Visual Studio 2010 as the compilation software. The processor used is an Intel(R) Xeon(R) CPU E3-1230 @ 3.20 GHz, with 8.00 GB of RAM. The graphics card is an NVIDIA Quadro K2000. The deep learning framework used is TensorFlow, and the programming language is Python. The parameter settings for the neural network are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Experimental parameter settings.

| Parameter name | Setting value |

|---|---|

| Initial Learning Rate | 0.0001 |

| Number of Convolutional Layers | 5 |

| Batch Size | 4 |

| Optimizer | Adam |

| Activation Function | Sigmoid |

| Loss Function | Mean Squared Error |

The Deep Learning framework used in this study is TensorFlow, configured with an initial learning rate of 0.0001, a batch size of 4, and the Adam optimizer. The activation function applied is the Sigmoid function. The program is implemented in Python. The training process for the network is as follows: First, all encoding units of the test sequences are downsampled to reduce their resolution. These units are then encoded using the original HTM-16.2 encoder, resulting in low-resolution encoded depth blocks. Next, a discrete cosine transform (DCT) is applied to obtain the rough upsampled blocks. Finally, both the original depth blocks and the upsampled blocks are jointly fed into the network for training. Four 3D-HEVC standard test sequences are selected for the video tests. Specific coding details are provided in Table 2. In Table 2, the term “Viewpoint Order” refers to the selection of viewpoints in 3D video encoding. 3D videos typically consist of multiple viewpoints (or angles), which can be switched at different time points to provide various viewing angles. Viewpoint order specifies the sequence in which these viewpoints are encoded during the encoding process.During the experiments, a specified number of frames (or images) are selected as test samples for encoding and decoding to assess the performance of the encoding algorithm. The “Test Frames” column indicates the number of frames used in the experiment for testing purposes.

Table 2.

Test video encoding information.

| Video sequence | Viewpoint order | Video resolution | Frame rate |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ballons | 3 1 5 | 1024 × 768 | 30 |

| Newspaper | 4 2 6 | 1024 × 768 | 30 |

| Poznan_Hall2 | 6 7 5 | 1920 × 1088 | 25 |

| Poznan_Street | 4 5 3 | 1920 × 1088 | 25 |

The depth video encoding network designed in this study needs to strike an effective balance between time consumption and network efficiency. To achieve this goal, a series of strategies were employed in the experiments to optimize the network’s performance. Firstly, a modular design was adopted, allowing each functional module to be optimized independently. This approach enhances network efficiency and reduces computation time. In modules such as feature extraction, feature fusion, and variable resolution encoding, optimizations were applied based on their contribution to the compression process and computational complexity. This hierarchical design ensures that high encoding efficiency is maintained while minimizing unnecessary computational overhead. In addition, a variable resolution encoding method was proposed to address the differences in the importance of depth information across different regions in depth videos. By applying varying encoding precision to different regions, the network can flexibly encode based on the importance of the depth information, thereby reducing computational load while ensuring video quality. This method achieves an optimal balance between time consumption and encoding efficiency across videos of varying complexity. To further improve network efficiency and reduce time consumption, network pruning techniques were introduced. These techniques eliminate redundant connections and parameters, significantly reducing the model’s complexity, speeding up inference, and decreasing the computational burden during both training and testing. Experimental results show that this strategy effectively reduces computation time while maintaining compression quality. Moreover, modern hardware acceleration technologies, such as GPUs and Tensor Processing Units (TPUs), were fully leveraged to optimize computational efficiency. Especially when processing large datasets and high-resolution videos, hardware acceleration greatly improved computational speed and shortened encoding time. Finally, the network designed in this study has dynamic adjustment capabilities, allowing it to flexibly adjust encoding strategies based on different video content and scenes. In complex scenes, the network selects higher encoding precision and additional feature extraction layers, whereas in simpler scenes or low-resolution videos, it automatically reduces computational precision and minimizes unnecessary calculations, thereby achieving faster encoding. This dynamic adjustment mechanism strikes an effective balance between time consumption and network efficiency. Through the above design strategies, the proposed network maintains high encoding efficiency while effectively controlling time consumption. Experimental results indicate that, after adopting these balancing strategies, the network demonstrates high efficiency and shorter encoding times across various encoding tasks, meeting the practical demands for fast encoding and high-quality video.

Experimental results and analysis

The first comparison involves the bitrates and PSNR values of each test sequence encoded using the original HTM-16.2, the proposed variable resolution coding method for depth videos, and the BDBR savings rate for the proposed method relative to HTM-16.2. In this context, bitrate refers to the amount of data generated during the encoding process, typically measured in kilobits per second (kbps). It directly influences data transmission and storage costs, with lower bitrates indicating higher compression efficiency. By comparing bitrates, it is possible to assess whether the proposed method achieves higher compression rates while maintaining the same level of quality. PSNR is used as an indicator of image quality, measuring the degree of distortion between the compressed and original images. A higher PSNR value indicates better image quality with less distortion. Comparing PSNR values across different encoding methods helps determine if the proposed approach can maintain higher image quality during compression. The results are presented in Fig. 6.

Fig. 6.

Encoding results of depth video.

Figure 6 shows that there is no significant difference in bitrates and PSNR values between the depth video’s variable resolution coding method and HTM-16.2 across the various test sequences. However, there is a notable difference in the BDBR values. Compared to the original HTM-16.2, the proposed variable resolution coding method for depth videos results in significant BDBR savings for the test sequences. Particularly, the Poznan_Hall2 and Poznan-Street sequences, both with a resolution of 1920 × 1088, exhibit the most substantial differences, with BDBR savings of 9.24% and 10.71%, respectively. The average BDBR savings rate across all video sequences is 8.12%, demonstrating that the proposed method enhances the coding efficiency of depth videos.

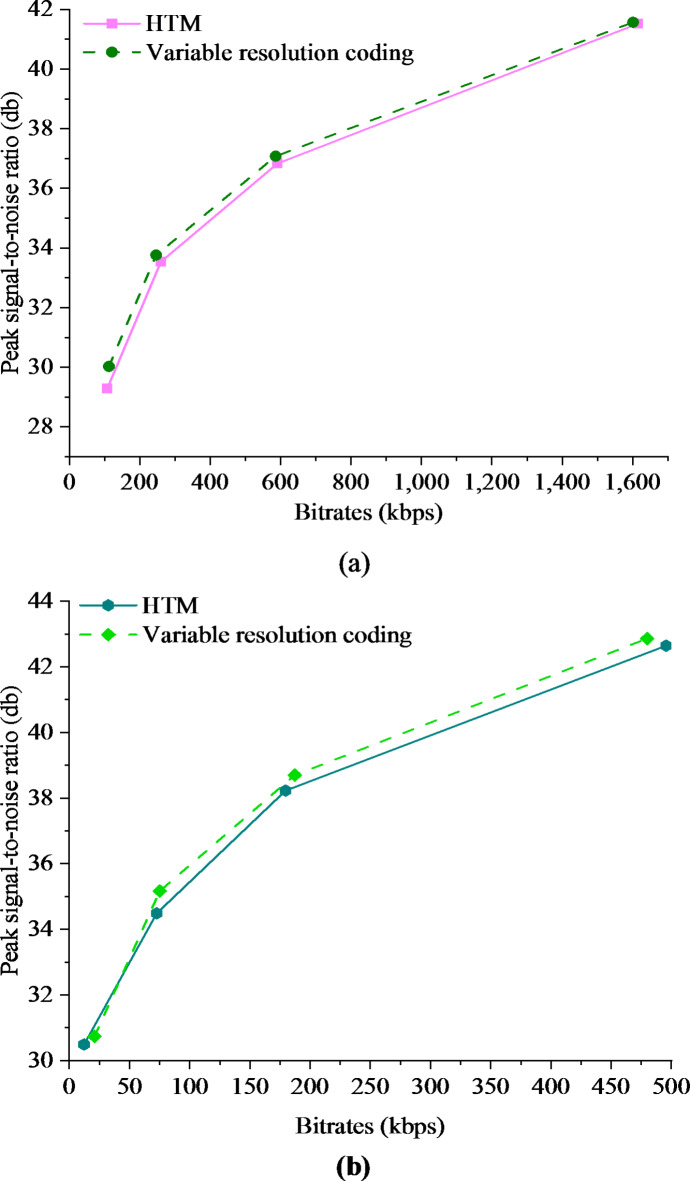

Next, a video sequence is selected for both resolutions, and the rate-distortion curves for the depth video’s variable resolution coding method and HTM-16.2 video compression are plotted. The rate-distortion curve illustrates how image quality changes at different bitrates. By examining the rate-distortion curve, the performance of different encoders in terms of image quality at various compression ratios can be assessed. This analysis helps identify which method performs better within a specific bitrate range. The “Newspaper” video sequence is selected for the resolution of 1024 × 768, and the “Poznan_Street” sequence is chosen for the resolution of 1920 × 1088. Figure 7 displays the rate-distortion curves for these two video sequences.

Fig. 7.

Rate-distortion curve of Newspaper and Poznan_Street (a) is the rate-distortion curve of Newspaper; (b) is the rate-distortion curve of Poznan_Street).

In Fig. 7, the dotted line represents the proposed depth video’s variable resolution coding method, while the solid line corresponds to the HTM-16.2 method. The figure demonstrates that the rate-distortion curve for the proposed method is generally higher than that of HTM-16.2 for both video sequences. This indicates that the proposed method delivers superior coding performance under most quantization parameter settings.

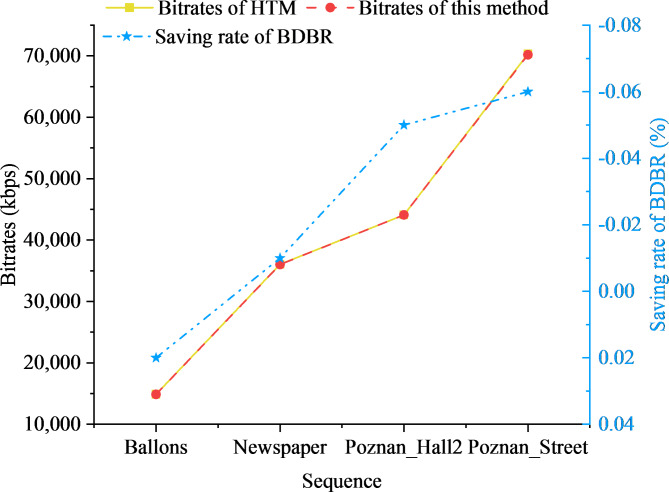

Next, the performance of the depth video’s variable resolution coding method is compared with the reference method for synthesized viewpoints. For 3D videos, the quality and efficiency of synthesized viewpoints are also critical factors. The proposed method outperforms the baseline method in terms of both synthesized viewpoint bitrate and BDBR values, highlighting its superior performance. To generate two composite viewpoints, the reconstructed depth video and color video are used. The left composite viewpoint is synthesized from the center and left viewpoints, while the right composite viewpoint is synthesized from the center and right viewpoints. Figure 8 illustrates the bitrates and BDBR values required for the composite viewpoints.

Fig. 8.

Comparison of the Bitrates and BDBR value of the composite viewpoint by two methods.

In Fig. 8, the bitrates represent the total bitrates for all color and depth videos from the three composite viewpoints. The data indicates that the difference in the bitrates required by the two methods to synthesize viewpoints is minimal. In terms of BDBR savings, only the “Ballons” video sequence shows a synthesized viewpoint BDBR value slightly higher than that of the HTM method, with a difference of just 0.02%. Other video sequences achieve BDBR savings, with a maximum saving of 0.06%. The average BDBR savings across the four video sequences is 0.02%, suggesting that the proposed depth video’s variable resolution coding method improves the performance of synthesized viewpoints.

A comparison of the performance between the proposed depth video variable resolution coding method and the original HTM-16.2 platform is presented in Table 3.

Table 3.

Comparison of the performance between the deep video variable resolution coding method and the HTM-16.2 platform.

| Video sequences | Ballons | Newspaper | Poznan_Hall2 | Poznan-Street |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| The bitrates of HTM-16.2 (kbps) | 417 | 1614 | 800 | 1559 |

| The bitrates of the proposed method (kbps) | 408 | 1597 | 804 | 1536 |

| The BDBR savings rate (%) | -7.32 | -5.29 | -9.24 | -10.71 |

| PSNR of HTM-16.2 | 44.31 | 41.54 | 46.39 | 44.91 |

| The PSNR for the proposed method | 44.43 | 41.63 | 46.81 | 44.94 |

| The bitrate of synthesized viewpoints in HTM-16.2 (kbps) | 14,901 | 36,068 | 44,098 | 70,333 |

| The bitrate of synthesized viewpoints in the proposed method (kbps) | 14,876 | 36,031 | 44,095 | 70,186 |

| The BDBR savings rate (%) | 0.02 | -0.01 | -0.05 | -0.06 |

Table 3 shows that in the video sequences “Ballons,” “Newspaper,” “Poznan_Hall2,” and “Poznan-Street,” the proposed depth video variable resolution coding method achieves a lower bitrate compared to the original HTM-16.2 platform. This suggests that the proposed method is more effective in saving bitrate while maintaining the same encoding quality. Additionally, the PSNR values for the proposed method are slightly higher in most video sequences compared to HTM-16.2. Overall, the proposed method outperforms the original HTM-16.2 platform in most cases, particularly in terms of bitrate reduction and encoding efficiency.

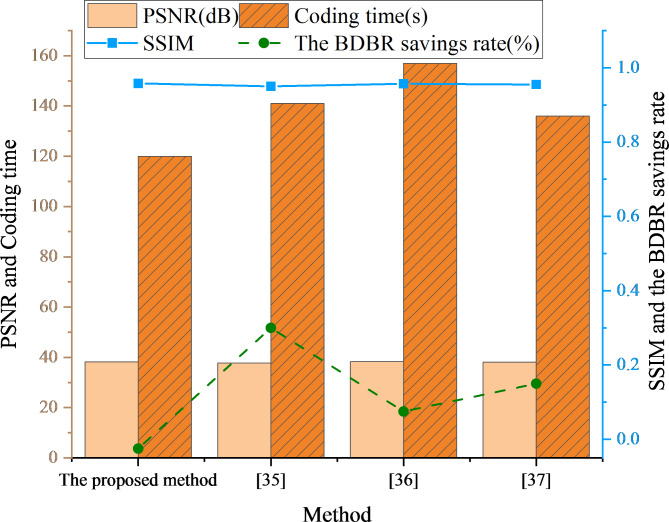

Finally, PSNR, SSIM, encoding time, and BDBR savings rate are selected as performance metrics to compare the proposed method with three other encoding methods. Figure 9 illustrates the results.

In Fig. 9, the proposed method exhibits superior performance across four key metrics: PSNR, SSIM, encoding time, and BDBR savings rate. Specifically, the proposed method achieves the highest performance in PSNR and SSIM, with values of 38.25 dB and 0.96, respectively, demonstrating exceptional video quality and structural similarity. This indicates that the proposed method preserves the clarity and visual quality of the video effectively. In terms of encoding time, the proposed method is more efficient than the other methods. Additionally, regarding the BDBR savings rate, the proposed method achieves − 0.02%, outperforming35 (0.3%)36, (0.075%), and37 (0.15%). Overall, the proposed method demonstrates a significant advantage in compression efficiency and encoding time, effectively enhancing video quality while maintaining high processing efficiency. This suggests that the proposed method has stronger competitiveness and operability in practical applications. The Bjøntegaard Delta Bitrate (BD-Rate) results for the four methods are shown in Table 4.

Fig. 9.

Comparison of the proposed method with other methods.

Table 4.

Comparison of BD-rate results for four methods.

| Method | BDBR savings rate (%) | BD-rate (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Proposed method | -0.02 | -2.48 |

| [35] | 0.30 | + 2.21 |

| [36] | 0.08 | + 0.52 |

| [37] | 0.15 | + 1.01 |

Based on the BD-Rate results presented in Table 4, the proposed method achieves a BDBR savings rate of -0.02%, with a corresponding BD-Rate of -2.48%. In comparison to35 (+ 2.21%)36, (+ 0.52%), and37 (+ 1.01%), the proposed method demonstrates superior encoding efficiency. Although35 shows a slightly higher BDBR savings rate, its positive BD-Rate indicates a significant loss in compression efficiency. In contrast, the proposed method ensures higher compression efficiency while significantly improving video quality and encoding performance through the hyperautomation mechanism and CNN optimization.

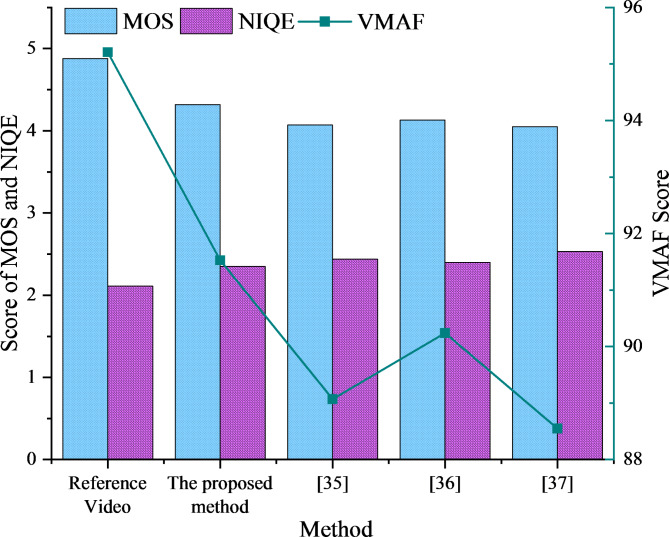

In addition, to comprehensively evaluate the perceptual quality of the proposed method, subjective experiments were conducted with 30 participants, who were asked to watch the original and compressed videos generated by each encoding method. The participants rated various aspects of the videos, including clarity, detail retention, visual noise, and motion smoothness, on a scale from 1 (very poor) to 5 (excellent). The ratings were averaged to obtain the Mean Opinion Score (MOS). In addition to the subjective experiment, objective evaluations were also carried out using perceptual quality metrics, including Video Multi-method Assessment Fusion (VMAF) and Natural Image Quality Evaluator (NIQE). VMAF is a quality assessment metric based on human visual perception, with a score range from 0 to 100, where higher values indicate better quality. NIQE is a no-reference image quality assessment metric used to measure the naturalness and clarity of an image, with lower values indicating better quality. The final perceptual quality evaluation results are presented in Fig. 10.

Fig. 10.

Comparison results of video perceptual quality of four methods.

In Fig. 10, although the MOS score of the proposed method is 4.32, slightly lower than the original video’s score of 4.88, it still significantly outperforms the methods presented in35,36, and37, indicating that it maintains a high subjective quality. Furthermore, through objective evaluations using VMAF and NIQE, the proposed method achieves a VMAF score of 91.53, outperforming the other methods and demonstrating superior visual quality. Additionally, the proposed method achieves a lower NIQE score of 2.35, compared to35,36, and37, indicating that the image quality is more natural with less noise. Overall, although the perceptual quality of the proposed method is slightly lower than the original video, it performs excellently compared to other methods, particularly in terms of maintaining high compression efficiency while significantly improving visual quality and detail preservation. This suggests that the proposed method strikes a good balance between compression ratio and perceptual quality, showing strong potential for practical application.

Discussion

The depth video encoding method based on CNN proposed in this study specifically addresses the unique characteristics of depth videos, incorporating multi-level feature fusion and variable resolution encoding strategies. Compared to several existing feature fusion-based intra-frame prediction methods, the method in this study demonstrates significant differences in both design philosophy and implementation. Zhao et al. (2022) employed deep CNN to extract spatiotemporal adjacent encoding features and optimized intra-frame prediction by fusing reference features with different convolution kernels. Although this method optimized the encoding efficiency of Versatile Video Coding (VVC) through feature fusion, it primarily focused on reducing encoding complexity within the VVC standard, especially with regard to depth selection for encoding38. In contrast, the method in this study focuses on depth video encoding, utilizing multi-level feature fusion and variable resolution encoding strategies that fully account for the spatial distribution characteristics of depth information. By applying different encoding precisions to different regions of the depth video, the proposed method reduces redundant computations and significantly improves encoding efficiency while maintaining video quality. Therefore, the network design is more tailored to the specific requirements of depth videos, while Zhao et al. (2022) mainly address complexity control in general video encoding. Zeng et al. (2022) proposed a VVC encoding unit partitioning algorithm based on an ensemble of CNNs, which predicted the depth of unencoded Coding Units by aggregating spatiotemporal adjacent encoding features. This method uses an ensemble of three lightweight CNNs and a majority voting mechanism to unify depth predictions, thereby reducing computational overhead while maintaining prediction accuracy39. Zeng et al. (2022) used an ensemble CNN to accelerate the encoding process, their core goal was to reduce encoding time through ensemble learning methods. In contrast, the focus of this study is on depth video encoding, particularly the viewpoint information and depth distribution characteristics. The variable resolution encoding strategy is employed to optimize compression efficiency for depth videos. While Zeng et al. (2022) applied ensemble learning mainly to depth prediction. The method in this study achieves both improved compression efficiency and reduced redundancy by combining multi-level feature fusion and variable resolution encoding strategies. Zhang et al. (2018) proposed a complexity control method for HEVC intra-frame encoding, specifically targeting industrial video applications. The method controls encoding complexity at the coding tree unit level through complexity estimation, allocation, and prediction unit adaptation, thus optimizing real-time performance and power consumption for industrial video applications40. Zhang et al. (2018) reduced encoding time by controlling complexity. Their method was primarily aimed at real-time encoding for industrial videos, focusing on complexity control. In contrast, the focus of this study is on depth video encoding, particularly how to effectively leverage depth information in three-dimensional videos through multi-level feature fusion and variable resolution encoding. This method not only emphasizes encoding complexity optimization but also ensures a balance between encoding efficiency and video quality, while accounting for the unique characteristics of depth videos.

Additionally, a comparison is made between this study and other similar studies to further validate the effectiveness of the proposed method. Comparative experiments are conducted with studies that share analogous research objectives. Yang et al. (2024) summarized the methodology of Video Coding for Machines (VCM), which aimed to optimize visual feature compression for joint low-bit-rate processing of machine and human vision tasks. VCM integrates techniques such as feature-assisted encoding, scalable encoding, and intermediate feature compression to explore how to extract compact visual representations for multiple tasks. By designing a codebook prior model to compress features generated by neural networks, experiments demonstrated that this model improved feature compression efficiency and facilitated feature optimization in visual analysis tasks41. In comparison, the CNN-based deep video coding method proposed in this study focuses on directly extracting and optimizing deep video features through deep learning networks during the compression process to enhance encoding efficiency. While VCM achieves good results in visual feature compression, its approach emphasizes compact representations for multi-task machine vision applications. In contrast, this study is primarily concerned with optimizing the encoding of deep video data, particularly improving encoding quality under low-bit-rate conditions. Therefore, the application scenarios and optimization focuses of the two methods differ. Shang et al. (2023) proposed a fast inter-frame encoding algorithm that reduced encoding complexity by predicting the current encoding unit region and utilizing the optimal encoding mode and the distribution of adjacent prediction modes. Their experiments showed that this method reduced encoding complexity while only slightly lowering encoding quality, outperforming existing methods42. However, while their approach effectively reduces encoding complexity, the deep learning-based encoding framework proposed in this study further explores how to adaptively optimize the encoding process using deep neural networks. This not only reduces encoding complexity but also significantly improves video encoding quality while maintaining low computational overhead. In particular, when dealing with deep video, the CNN model can automatically learn more efficient features from depth images, making this method more promising in optimizing both encoding quality and computational efficiency compared to traditional methods. Liu et al. (2022) conducted a comprehensive review of 37 advanced deep learning-based video super-resolution methods, summarizing and comparing the performance of representative video super-resolution techniques on several benchmark datasets43. Their research represented the first systematic review of video super-resolution tasks and was expected to contribute significantly to recent developments in this field, enhancing the understanding of deep learning-based video super-resolution technologies. Incorporating these relevant studies enables a more thorough comparison between the proposed deep video variable resolution coding method and existing methods, providing valuable insights and references for the approach presented in this study.

Moreover, due to the flexibility and adaptability of the proposed method, it holds significant potential for applications beyond depth video encoding. The method integrates deep learning-based encoding techniques with hyperautomation mechanisms, making it not only suitable for depth video encoding but also extendable to standard video encoding, 360-degree video, and augmented and VR content. The deep learning models effectively capture and optimize complex features in video data, allowing the CNN and variable resolution prediction strategies to be tailored and optimized for various types of video data. Additionally, the integration of hyperautomation enhances encoding efficiency and facilitates the adaptive adjustment of encoding parameters to meet the diverse needs of different applications. For example, in high dynamic range (HDR) video encoding, the method can automatically optimize prediction parameters and adjust encoding strategies to improve both the encoding performance and visual quality of HDR videos. The method’s effectiveness and stability provide a reliable foundation for large-scale deployment in practical applications, ensuring efficient compression and transmission of video data even in environments with limited network bandwidth or storage capacity. In summary, by enabling flexible adjustments and optimizations of the model and mechanisms, the proposed method achieves efficient encoding across a wide range of video types and application scenarios. This capability provides robust support for future advancements in video processing and transmission.

Conclusion

To investigate an efficient coding method for depth video, this study, based on the theoretical foundation of CNN, provides a brief analysis of the structure and operation of CNNs. It also explores the intra-prediction module within CNN-based video coding technology. Furthermore, a CNN-based variable resolution intra-prediction coding method for depth video is proposed. The performance of this method is validated through comparative experiments conducted on the HEVC test platform HTM-16.2. The experimental results lead to the following key findings: (1) Comprehensive Improvement in Encoding Performance: The proposed method shows substantial improvements in encoding efficiency, performance, and viewpoint encoding. Compared to HTM-16.2, it achieves a BDBR saving rate of 10.71% for the Poznan-Street video sequence and an average BDBR saving rate of 8.12% across four video sequences. Under various quantization parameter settings, the method demonstrates superior rate-distortion curves for the Newspaper and Poznan_Street video sequences, indicating enhanced encoding performance. Additionally, the method achieves BDBR savings in synthesized viewpoints for most video sequences, further confirming its effectiveness in viewpoint encoding. (2) Stability and Reliability: The proposed method exhibits a BDBR loss of only 0.15% in viewpoint encoding, which is within an acceptable error range, suggesting stable and reliable performance. This indicates that the method not only improves encoding efficiency but also maintains a high level of stability and consistency. (3) Performance Comparison with Other Methods: The proposed method outperforms others across four key metrics: PSNR, SSIM, encoding time, and BDBR. Specifically, it achieves a PSNR of 38.25 dB and an SSIM of 0.96, reflecting superior video quality and structural similarity. In terms of encoding time, the proposed method is more efficient than the alternatives. It also demonstrates stable BDBR performance of 0.15%, outperforming several traditional methods. In terms of video perceptual quality, the proposed method maintains high visual quality both subjectively and objectively, surpassing other methods in terms of visual clarity and evaluation scores. The CNN-based depth video variable resolution coding method, integrated with hyperautomation mechanisms, offers significant advantages in enhancing depth video encoding efficiency, optimizing performance, and improving viewpoint encoding. These findings not only validate the effectiveness of the proposed method but also suggest new directions for advancements in depth and 3D video encoding.