Abstract

Recurrent miscarriage (RM) is a reproductive disorder affecting couples worldwide. The underlying molecular mechanisms remain elusive, even though emerging evidence has implicated endoplasmic reticulum stress (ERS). We investigated RM- and ERS-related genes to develop a diagnostic model that can enhance predictive ability. We utilized the R package GEO query to extract and process Gene Expression Omnibus data, applying batch correction, normalization, and differential gene expression analysis with limma. ERS-related differentially expressed genes (ERSRGs) were identified through Gene Ontology and Kyoto Encyclopedia of genes and genomes analyses, and their diagnostic potential was assessed. Diagnostic models were developed using logistic regression, support vector machines, and least absolute shrinkage and selection operators, complemented by immune infiltration analysis and regulatory network construction. Integrated analysis revealed 1395 differentially expressed genes (DEGs), including 626 upregulated and 769 downregulated genes. Seventeen ERSRGs were identified. KEAP1 and YIPF5 displayed high diagnostic accuracy (area under the curve [AUC] > 0.9). Gene Ontology and Kyoto Encyclopedia of genes and genomes analyses highlighted the role of ESRDEGs in cellular responses to ERS, protein processing, and apoptosis. Diagnostic models demonstrated robust predictive performance (AUC > 0.9). A molecular interaction was found between RM and the ERS response, and the identified ESRDEGs could serve as potential biomarkers for diagnosis.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41598-024-77642-w.

Keywords: Recurrent miscarriage, Endoplasmic reticulum stress, Diagnostic model, Immune Infiltration, Bioinformatics

Subject terms: Computational biology and bioinformatics, Medical research

Introduction

Experiencing a miscarriage twice or more consecutively before 28 weeks of pregnancy is known as recurrent miscarriage (RM), which accounts for approximately 2–5% of total pregnancies1. Despite its prevalence, the etiology of RM remains elusive, with potential contributing factors ranging from genetic abnormalities and endocrine dysfunction to immunological and anatomical issues2. The psychological impact on affected women and their partners is profound, and the condition is associated with a marked increase in healthcare costs3. Current diagnostic strategies for RM are limited, resulting in a considerable number of cases remaining unexplained. This emphasizes the need for improved diagnostic tools and a more comprehensive understanding of the underlying molecular mechanisms4.

Endoplasmic reticulum stress (ERS) is a process by which cells activate a series of signaling pathways in response to conditions such as the accumulation of misfolded and unfolded proteins in the lumen of the ER and disturbances in calcium ion homeostasis5. The role of ERS as part of the cellular stress response in RM has received increasing attention. Abnormal embryonic development may be associated with impaired protein folding and modification in the ER6. When ERS-related differentially expressed genes (ERSRGs) are abnormal, it may result in the accumulation of unfolded or misfolded proteins in the ER, which in turn affects normal embryo development. ERSRGs such as IP3R (inositol trisphosphate receptor), are involved in the process of calcium ion release and reabsorption. Abnormal expression or dysfunction of these genes may lead to disturbance in calcium ion homeostasis, which in turn induces apoptosis and RM7. CHOP (C/EBP homologous protein) is one of the key molecules in ERS-induced apoptosis. When ERSRGs are abnormal, it may lead to the upregulation of the expression of apoptosis-related proteins such as CHOP, which in turn triggers apoptosis and RM8. Abnormal expression or dysfunction of ERSRGs may affect the synthesis and secretion of estrogen and progesterone, which in turn may interfere with the maintenance of pregnancy and normal embryonic development9.

Our findings provide insights into the role of ERSRGs in RM. We identified some promising diagnostic biomarkers that may help in the treatment of the disease. The multidimensional bioinformatics approach used in this paper provides new ideas and targets for the development of new diagnostic methods and therapeutic strategies in the future. By examining the expression levels or functional status of ERSRGs, the risk of RM in patients can be assessed, and interventions targeting these genes may also be a new approach for treating RM.

Results

Merging of RM datasets

In Supplementary Figure S1, we show the flowchart of the study design. First, the GSE22490 and GSE165004 RM datasets were combined using the R package sva. Supplementary Figure S2a–d shows the distribution boxplots and PCA plots used to compare the datasets before and after batch effect removal. When the batch effect of the samples was removed from the RM dataset, the distribution box and PCA plots showed that the batch effect was essentially eliminated.

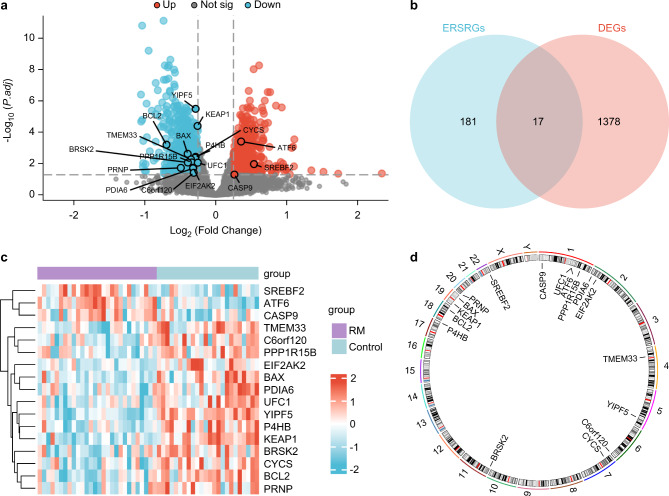

Differentially expressed genes related to ERS in RM

The R package limma was used to analyze the differences in gene expression values between the RM and control groups in the combined Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) datasets. A total of 1,395 met | logFC | > 0.25 and adj.p < 0.05 threshold of differentially expressed genes (DEGs). At this threshold, 626 genes were upregulated (logFC > 0.25 and adj.p < 0.05), and 769 genes were downregulated (logFC < − 0.25 and adj.p < 0.05), as shown in Fig. 1a. To identify the DEGs linked to the ERS-related DEGs (ERSRDEGs), all | logFC | > 0.25, adj.p < 0.05, DEGs, and ERSRGs were intersected and mapped (Fig. 1b). The 17 ERSRDEGs identified were BAX, ATF6, BCL2, P4HB, CASP9, EIF2AK2, PRNP, CYCS, TMEM33, BRSK2, UFC1, C6orf120, PDIA6, KEAP1, SREBF2, YIPF5, and PPP1R15B. The expression of ERSRDEGs between different sample groups in the combined GEO datasets was analyzed using the results, and a heatmap was drawn using the R package heatmap (Fig. 1c). Finally, using the R package RCircos, we analyzed 17 ERSRDEG locations on the human chromosomes (Fig. 1d). Chromosomal mapping showed that more ERSRDEGs were located in chromosome 1, including CASP9, UFC1, ATF6, and PPP1R15B.

Fig. 1.

Differential gene expression analysis. (a) Analysis of DEGs in the combined GEO datasets between RM and control groups using volcano plots. (b) DEGs and ERSRGs in the combined GEO datasets are shown in a Venn diagram. (c) Heat map of ERSRDEGs in combined GEO dataset. (d) Chromosomal mapping of ERSRDEGs. Purple represents the RM group, and blue represents the control group.

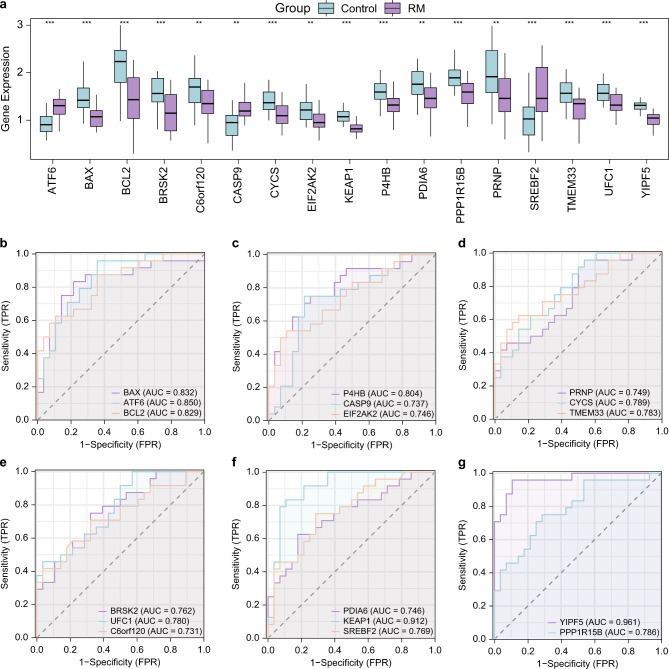

Differential expression and ROC curve analysis

Group comparison revealed the differential expression of 17 ERSRDEGs between the RM and control groups in the combined GEO datasets (Fig. 2a). The differential results showed that all ERSRDEGs were significantly expressed in the RM and control groups in the combined datasets (p-value < 0.05; Fig. 2a). There were 12 ERSRDEGs: ATF6, BAX, BCL2, BRSK2, CYCS, KEAP1, P4HB, PPP1R15B, SREBF2, TMEM33, UFC1, and YIPF5. A highly significant difference was observed between the RM and control groups in the combined datasets (p < 0.001). Five ERSRDEGs, C6orf120, CASP9, EIF2AK2, PDIA6, and PRNP, were significantly different (p < 0.01) between the RM and control groups of the combined GEO datasets. ROC curves were drawn using the R package pROC based on the expression levels of ERSRDEGs in the combined datasets. Figure 2b–g shows the expression levels of two ERSRDEGs, KEAP1 and YIPF5, which showed high accuracy among the different groups (area under the curve [AUC] > 0.9) in the combined datasets. Fifteen ERSRDEGs, BAX, ATF6, BCL2, P4HB, CASP9, EIF2AK2, PRNP, CYCS, TMEM33, BRSK2, UFC1, C6orf120, PDIA6, SREBF2, and PPP1R15B, showed some accuracy between the different groups (0.7 < AUC < 0.9) in the combined datasets.

Fig. 2.

Differential expression validation and ROC curve analysis. (a) Comparison of ERSRDEGs in RM and control groups of combined GEO datasets. (b–g) ROC curves of ERSRDEGs in combined GEO dataset. ** represents p-value < 0.01, highly statistically significant; *** represents p-value < 0.001 and highly statistically significant. AUC > 0.9 had high accuracy, and AUC 0.7–0.9 had moderate accuracy. The RM group is shown in purple, and the control group is shown in blue.

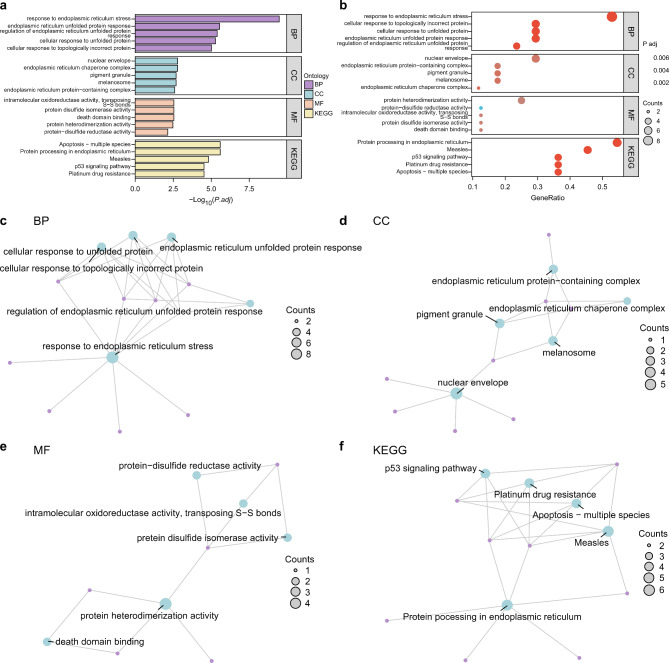

Gene Ontology and Kyoto Encyclopedia of genes and genomes pathway enrichment analyses of RM

Gene Ontology (GO) and Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) enrichment analyses were visualized using a bar graph (Fig. 3a) and bubble plots (Fig. 3b), and the results are presented in Table 1. Additionally, the biological process (BP), cell component (CC), and molecular function (MF) categories of GO and the KEGG biological pathways were illustrated (Fig. 3c–f). The images shown in Fig. 3a and b were sourced from the KEGG database10. Moreover, the pathway enrichment analysis for protein processing in the ER (Supplementary Figure S3a), apoptosis-multiple species (Supplementary Figure S3b), platinum drug resistance (Supplementary Figure S3c), measles (Supplementary Figure S3d), and the p53 signaling pathway (Supplementary Figure S3e) in KEGG were visualized using the Pathview package in R. The pathway images in Supplementary Fig. 3 were sourced from the KEGG database10.

Fig. 3.

GO and KEGG enrichment analysis for ERSRDEGs. (a) ERSRDEG enrichment analysis according to GO and KEGG pathways. (b) Bubble diagram of GO and KEGG enrichment analysis results for ERSRDEGs. (c–f) GO and KEGG enrichment analysis results of the ERSRDEGs network diagram showing BP (c), CC (d), MF (e), and KEGG (f). Blue nodes represent items, purple nodes represent molecules, and lines represent relationships between items and molecules. Screening criteria for GO and KEGG enrichment analyses were adjusted to p < 0.05, FDR value (q value) < 0.25, and Benjamini–Hochberg (BH) was used as the correction method.

Source: KEGG database Project, Kanehisa Laboratories, Ref. No.: 240,567

Table 1.

Results of GO and KEGG enrichment analyses for ERSRDEGs.

| ONTOLOGY | ID | GeneRatio | BgRatio | p-value | p.adjust | q value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BP | GO:0034976 | 9/17 | 257/18,800 | 3.20E-13 | 3.13E-10 | 1.67E-10 |

| BP | GO:0030968 | 5/17 | 76/18,800 | 5.63E-09 | 2.75E-06 | 1.47E-06 |

| BP | GO:1,900,101 | 4/17 | 30/18,800 | 1.24E-08 | 4.02E-06 | 2.15E-06 |

| BP | GO:0034620 | 5/17 | 98/18,800 | 2.04E-08 | 4.99E-06 | 2.67E-06 |

| BP | GO:0035967 | 5/17 | 117/18,800 | 4.99E-08 | 9.75E-06 | 5.21E-06 |

| CC | GO:0034663 | 2/17 | 11/19,594 | 3.88E-05 | 1.58E-03 | 1.03E-03 |

| CC | GO:0005635 | 5/17 | 479/19,594 | 4.15E-05 | 1.58E-03 | 1.03E-03 |

| CC | GO:0042470 | 3/17 | 109/19,594 | 1.08E-04 | 2.04E-03 | 1.33E-03 |

| CC | GO:0048770 | 3/17 | 109/19,594 | 1.08E-04 | 2.04E-03 | 1.33E-03 |

| CC | GO:0140534 | 3/17 | 125/19,594 | 1.61E-04 | 2.45E-03 | 1.60E-03 |

| MF | GO:0070513 | 2/16 | 11/18,410 | 3.88E-05 | 2.94E-03 | 1.81E-03 |

| MF | GO:0003756 | 2/16 | 18/18,410 | 1.07E-04 | 2.94E-03 | 1.81E-03 |

| MF | GO:0016864 | 2/16 | 18/18,410 | 1.07E-04 | 2.94E-03 | 1.81E-03 |

| MF | GO:0046982 | 4/16 | 332/18,410 | 1.59E-04 | 3.26E-03 | 2.01E-03 |

| MF | GO:0015035 | 2/16 | 37/18,410 | 4.63E-04 | 7.60E-03 | 4.68E-03 |

| KEGG | hsa04141 | 6/11 | 171/8164 | 3.28E-08 | 2.45E-06 | 1.06E-06 |

| KEGG | hsa04215 | 4/11 | 32/8164 | 6.29E-08 | 2.45E-06 | 1.06E-06 |

| KEGG | hsa05162 | 5/11 | 139/8164 | 5.67E-07 | 1.47E-05 | 6.36E-06 |

| KEGG | hsa01524 | 4/11 | 73/8164 | 1.85E-06 | 2.89E-05 | 1.25E-05 |

| KEGG | hsa04115 | 4/11 | 73/8164 | 1.85E-06 | 2.89E-05 | 1.25E-05 |

GO, gene ontology; BP, biological process; CC, cellular component; MF, molecular function; KEGG, Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes; ERSRDEGs, endoplasmic reticulum stress-related differentially expressed genes.

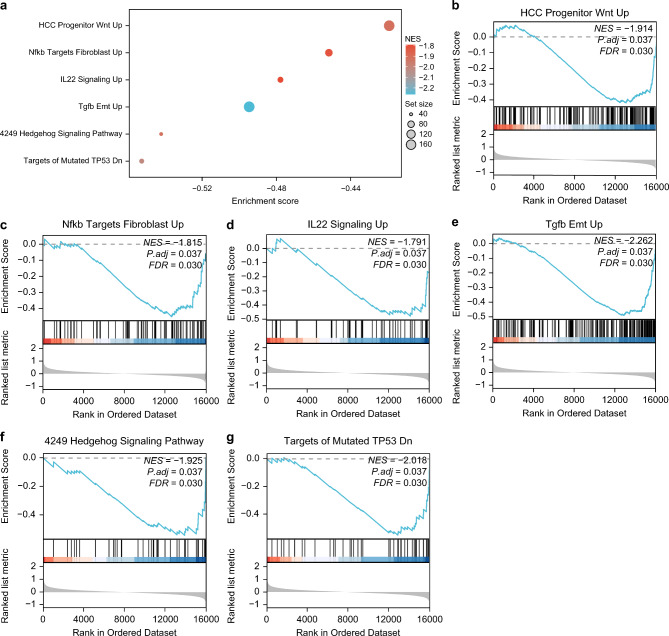

Gene set enrichment analysis of RM

Gene set enrichment analysis (GSEA) was used to investigate the expression of all genes and BP involved in RM in combined datasets. The relationships between the cellular components and MF are shown in Fig. 4a, as well as in Supplementary Table S1. HCC Progenitor Wnt Up significantly enriched all genes in the combined datasets (Fig. 4b), Nfkb Targets Fibroblast Up (Fig. 4c), IL22 Signaling Up (Fig. 4d), Tgfb Emt Up (Fig. 4e), 4249 Hedgehog Signaling Pathway (Fig. 4f), Targets of Mutated TP53 Dn (Fig. 4g), and other biologically related functions and signaling pathways.

Fig. 4.

GSEA for combined datasets. (a) Gene set enrichment analysis (GSEA) 6 biological functions bubble plot presentation of combined GEO dataset. (b–g) GSEA showed that genes from the combined GEO dataset were significantly enriched in HCC Progenitor Wnt Up (b), Nfkb Targets Fibroblast Up (c), IL22 Signaling Up (d), Tgfb Emt Up (e), 4249 Hedgehog Signaling Pathway (f), Targets of Mutated TP53 Dn (g). The screening criteria of GSEA were adj.p < 0.05 and FDR value (q value) < 0.25, and the p-value correction method was BH.

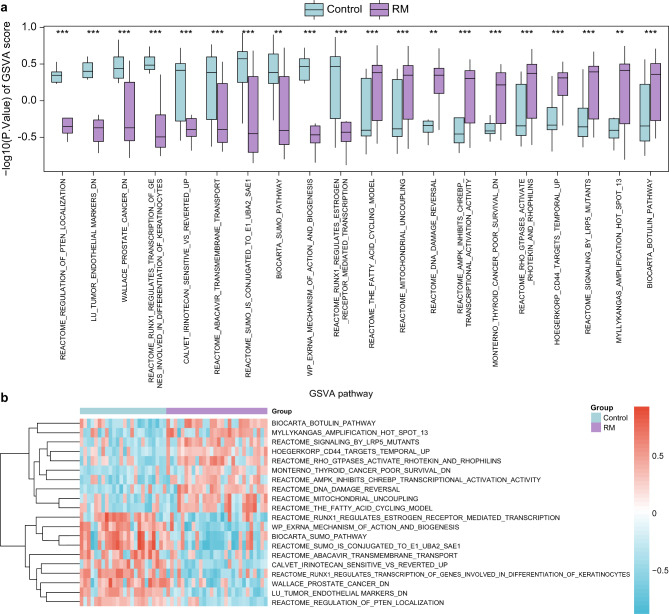

Gene set variation analysis for RM

To investigate the c2.cgp.v2023.2 Hs.symbols.gmt gene set, we integrated and compared genes from combined datasets of the RM and control groups using gene set variation analysis (GSVA), as detailed in Supplementary Table S2. Subsequently, we screened pathways with adj.p < 0.05, positive and negative top10 logFC, and then displayed the results (Fig. 5a). The results of GSVA showed that 17 pathways were highly statistically significant in the RM and control groups (p < 0.001). These pathways include: Regulation of PTEN Localization, Tumor Endothelial Markers Down, Prostate Cancer Down, RUNX1 Regulates Transcription of Genes Involved in Differentiation of Keratinocytes, Irinotecan Sensitive vs. Reverted Up, Abacavir Transmembrane Transport, SUMO is Conjugated to E1 UBA2 SAE1, Exrna Mechanism of Action and Biogenesis, RUNX1 Regulates Estrogen Receptor-Mediated Transcription, The Fatty Acid Cycling Model, Mitochondrial Uncoupling, Ampk Inhibits Chrebp Transcriptional Activation Activity, Thyroid Cancer Poor Survival Down, Rho GTPases Activate Rhotekin and Rhophilins, CD44 Targets Temporal Up, Signaling by LRP5 Mutants, and Biocarta Botulin Pathway. Three pathways—SUMO Pathway, DNA Damage Reversal, and Myllykangas Amplification Hot Spot 13—were highly statistically significant in the RM and control groups (p < 0.01). Finally, according to the results of GSVA, the differential expression of 20 pathways with p < 0.05 and positive or negative top 10 logFC between the RM and control groups was analyzed and visualized in a heatmap (Fig. 5b).

Fig. 5.

GSVA for combined datasets. Boxplot (a) and heat map (b) of group comparison of GSVA results in RM and control. ** represents p-value < 0.01, highly statistically significant; *** represents p-value < 0.001 and highly statistically significant. Screening criteria for GSVA were adj. p < 0.05, positive or negative top10 logFC, and the p-value correction method was BH. The RM group is purple, and the control group is blue.

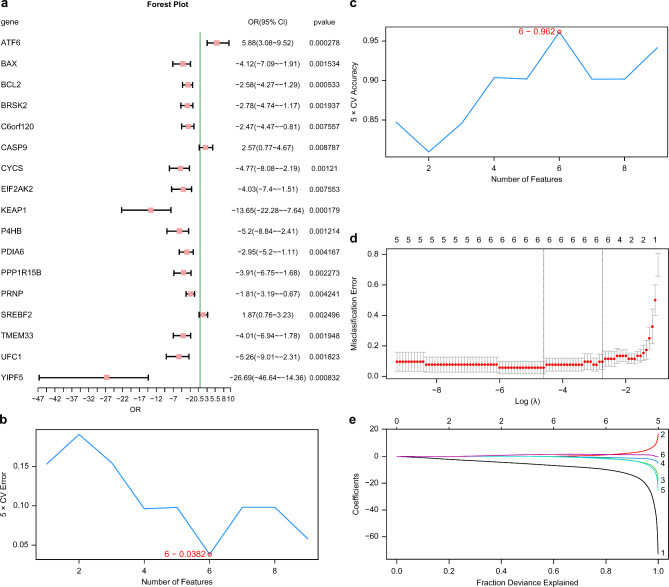

Construction of RM diagnostic model

First, the diagnostic values of 17 ERSRDEGs in RM were assessed using logistic regression and displayed using a forest plot (Fig. 6a). The results showed that 17 ERSRDEGs were statistically significant (p-value < 0.05), namely BAX, ATF6, BCL2, P4HB, CASP9, EIF2AK2, PRNP, CYCS, TMEM33, BRSK2, UFC1, C6orf120, PDIA6, KEAP1, SREBF2, YIPF5, and PPP1R15B. Next, to determine the genes with the lowest error rate (Fig. 6b) and the highest accuracy (Fig. 6c), an SVM model was developed using the 17 ERSRDEGs and the SVM algorithm. The accuracy of the SVM model was highest when six genes were used (YIPF5, CASP9, PPP1R15B, EIF2AK2, CYCS, and ATF6). Thereafter, based on the ERSRDEGs contained in the six-gene SVM model, the LASSO regression model (RM diagnosis model) was constructed. Figure 6d and E illustrate the LASSO regression model and the variable trajectory, respectively. Six ERSRDEGs were included in the LASSO regression model, namely YIPF5, CASP9, PPP1R15B, EIF2AK2, CYCS, and ATF6.

Fig. 6.

Diagnostic model of RM. (a) Logistic regression model for 17 ERSRDEGs included in RM diagnostic model. (b, c) Number of genes with the lowest error rate (b) and highest accuracy (c) determined by the SVM algorithm. (d, e) LASSO regression model diagnostic plots (d) and variable trajectory plots ( e).

Validation of the RM diagnostic model

In the combined datasets, ROC curves were drawn using the R package pROC based on the RiskScore (Supplementary Fig. 4a). The ROC curve shows that the expression level of the RiskScore in the combined GEO datasets exhibits high accuracy between the different groups (AUC > 0.9). The risk score was calculated using the following formula:

|

FRIENDS analysis (functional similarity analysis) was used to identify genes involved in the BP of RM (Supplementary Fig. 4b)11. The results showed that YIPF5 played an important role in RM, which was closest to the cutoff value (0.85). Furthermore, a nomogram based on key genes was constructed to show the interrelationships between the key genes in the combined datasets (Supplementary Fig. 4c). Compared to the other variables, YIPF5 had a significantly higher utility, whereas ATF6 had a significantly lower utility for the RM diagnostic model.

Calibration curves were analyzed to measure the accuracy and discrimination of the RM diagnostic model. As shown in Supplementary Fig. 4d, the predictive effectiveness of the model was evaluated by comparing its actual and predicted probabilities. RM diagnostic models based on the RiskScore were evaluated and presented using decision curve analysis (Supplementary Fig. 4e). The findings indicated that the model’s performance was consistently superior to all positive and negative values within a specific range, resulting in greater net benefit and improved overall effectiveness.

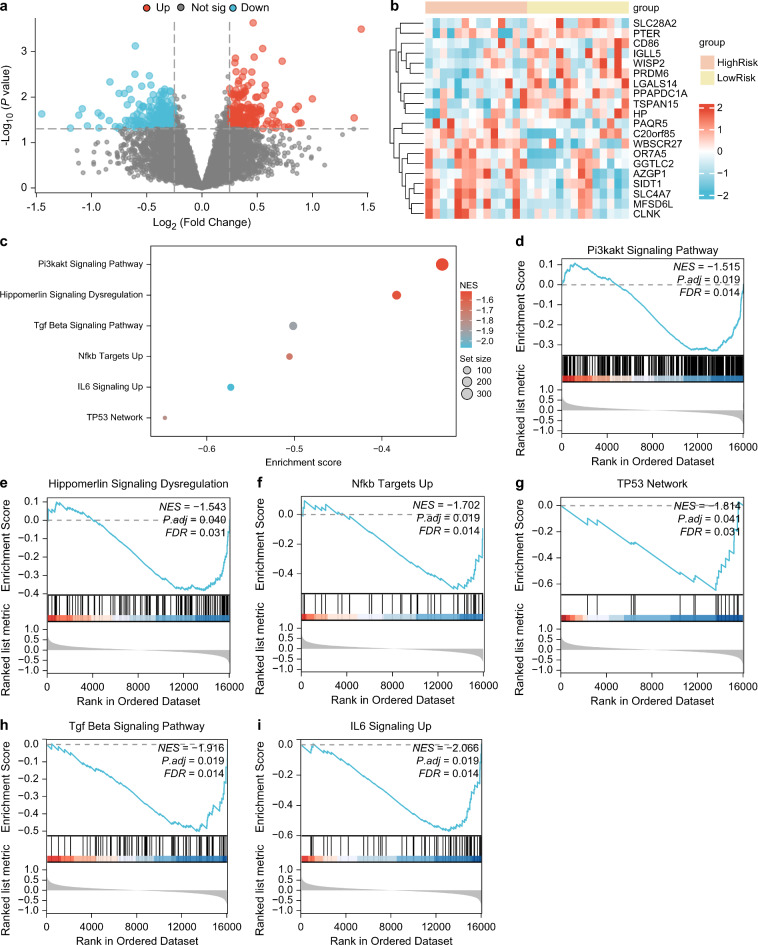

GSEA for high- and low-risk groups

We divided the RM samples from the combined dataset into high- and low-risk groups. We observed DEGs using the R package limma to analyze the differences in gene expression values between these groups in the RM samples of the combined datasets and found a total of 390 DEGs meeting the threshold of | logFC | > 0.25 and p < 0.05. According to the variance analysis results in Fig. 7a, there were 199 DEGs with higher expression (logFC > 0.25 and p < 0.05) and 191 with lower expression (logFC < 0.25 p < 0.05). The expression differences of positive and negative top 10 logFC DEGs in the RM samples of the combined datasets were analyzed (Fig. 7b).

Fig. 7.

GSEA for risk group. (a) Volcano plot of DEGs analysis in high-risk and low-risk groups of RM samples. (b) Heat map of positive and negative top ten logFC DEGs in RM samples from combined GEO dataset. (c) GSEA six biological function bubble plot presentation in RM samples from combined GEO dataset. (d–i) GSEA showed that genes in RM samples of the combined GEO dataset were significantly enriched in Pi3kakt signaling pathway (d). Hippomerlin Signaling Dysregulation (e), Nfkb Targets Up (f), TP53 Network (g), Tgf Beta Signaling Pathway (h), IL6 Signaling Up (i). The screening criteria of GSEA were adj.p < 0.05 and FDR value (q value) < 0.25, and the p-value correction method was BH.

GSEA was used to investigate the association between the expression levels of all the genes in the RM samples of the combined datasets (Fig. 7c). Detailed results are presented in Table 2. All genes in the RM samples of the combined datasets were significantly enriched in the PI3K-AKT signaling pathway (Fig. 7d), hippomerlin signaling dysregulation (Fig. 7e), NFKB targets (Fig. 7f), TP53 network (Fig. 7g), TGF beta signaling pathway (Fig. 7h), and IL6 signaling (Fig. 7i).

Table 2.

Results of GSEA for Risk Group.

| ID | Set size | Enrichment score | NES | p-value | p.adjust | q value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CHARAFE_BREAST_CANCER_LUMINAL_VS_MESENCHYMAL_UP | 401 | 4.07E-01 | 1.99E + 00 | 2.78E-03 | 2.55E-02 | 1.94E-02 |

| REACTOME_BRANCHED_CHAIN_AMINO_ACID_CATABOLISM | 21 | 6.67E-01 | 1.95E + 00 | 2.16E-03 | 2.00E-02 | 1.53E-02 |

| DOANE_BREAST_CANCER_CLASSES_UP | 64 | 5.14E-01 | 1.94E + 00 | 2.17E-03 | 2.02E-02 | 1.54E-02 |

| LIM_MAMMARY_STEM_CELL_DN | 376 | 4.00E-01 | 1.93E + 00 | 2.77E-03 | 2.54E-02 | 1.94E-02 |

| REACTOME_CHOLESTEROL_BIOSYNTHESIS | 24 | 6.23E-01 | 1.90E + 00 | 4.22E-03 | 3.34E-02 | 2.55E-02 |

| HOLLERN_EMT_BREAST_TUMOR_DN | 113 | 4.60E-01 | 1.90E + 00 | 2.34E-03 | 2.16E-02 | 1.65E-02 |

| VETTER_TARGETS_OF_PRKCA_AND_ETS1_UP | 14 | 7.13E-01 | 1.89E + 00 | 2.02E-03 | 1.89E-02 | 1.44E-02 |

| WP_CHOLESTEROL_BIOSYNTHESIS_PATHWAY | 13 | 7.23E-01 | 1.87E + 00 | 4.07E-03 | 3.24E-02 | 2.47E-02 |

| SCHMIDT_POR_TARGETS_IN_LIMB_BUD_UP | 25 | 6.05E-01 | 1.85E + 00 | 4.30E-03 | 3.40E-02 | 2.60E-02 |

| REACTOME_CARNITINE_METABOLISM | 13 | 7.13E-01 | 1.84E + 00 | 4.07E-03 | 3.24E-02 | 2.47E-02 |

| KYNG_ENVIRONMENTAL_STRESS_RESPONSE_DN | 16 | 6.65E-01 | 1.83E + 00 | 4.13E-03 | 3.28E-02 | 2.50E-02 |

| WP_CHOLESTEROL_SYNTHESIS_DISORDERS | 16 | 6.60E-01 | 1.82E + 00 | 4.13E-03 | 3.28E-02 | 2.50E-02 |

| BOYAULT_LIVER_CANCER_SUBCLASS_G12_DN | 15 | 6.60E-01 | 1.79E + 00 | 4.11E-03 | 3.27E-02 | 2.50E-02 |

| KEGG_BUTANOATE_METABOLISM | 33 | 5.45E-01 | 1.78E + 00 | 4.27E-03 | 3.38E-02 | 2.58E-02 |

| WP_PI3KAKT_SIGNALING_PATHWAY | 323 | -3.31E-01 | -1.51E + 00 | 1.58E-03 | 1.85E-02 | 1.42E-02 |

| WP_HIPPOMERLIN_SIGNALING_DYSREGULATION | 114 | -3.83E-01 | -1.54E + 00 | 5.15E-03 | 4.00E-02 | 3.06E-02 |

| MARTIN_NFKB_TARGETS_UP | 40 | -5.05E-01 | -1.70E + 00 | 1.94E-03 | 1.85E-02 | 1.42E-02 |

| WP_TP53_NETWORK | 18 | -6.48E-01 | -1.81E + 00 | 5.76E-03 | 4.11E-02 | 3.14E-02 |

| KEGG_TGF_BETA_SIGNALING_PATHWAY | 81 | -5.01E-01 | -1.92E + 00 | 1.77E-03 | 1.85E-02 | 1.42E-02 |

| DASU_IL6_SIGNALING_UP | 55 | -5.73E-01 | -2.07E + 00 | 1.83E-03 | 1.85E-02 | 1.42E-02 |

GSEA, Gene set enrichment analysis.

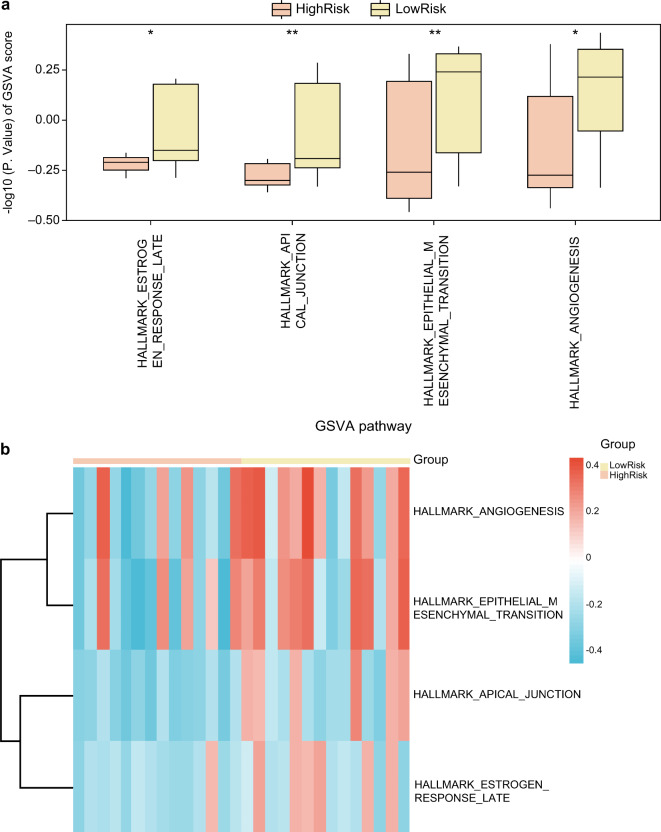

GSVA for high- and low-risk groups

To explore the h.all.v2023.2.Hs.symbols.gmt gene set within RM samples categorized into high- and low-risk groups, a GSVA was conducted on all genes from these combined datasets. Details are presented in Table 3. Subsequently, we screened pathways with a p-value < 0.05 and displayed the findings using a diagram comparing the groups (Fig. 8a). The results of GSVA showed that two pathways, apical junction and epithelial–mesenchymal transition, were highly statistically significant in the high- and low-risk groups (p < 0.01). The two pathways of estrogen response and angiogenesis were statistically significant in the high- and low-risk groups (p < 0.05). Finally, the GSVA results were analyzed and visualized in heat maps showing the differential expression of the four pathways (p < 0.05) between the high- and low-risk groups (Fig. 8b).

Table 3.

Results of GSVA for risk group.

| ID | logFC | AveExpr | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| HALLMARK_APICAL_JUNCTION | 2.31E-01 | -1.67E-01 | 3.47E-03 |

| HALLMARK_ANGIOGENESIS | 2.82E-01 | 3.46E-03 | 1.07E-02 |

| HALLMARK_EPITHELIAL_MESENCHYMAL_TRANSITION | 2.54E-01 | -1.38E-02 | 2.05E-02 |

| HALLMARK_ESTROGEN_RESPONSE_LATE | 1.56E-01 | -1.17E-01 | 4.59E-02 |

GSVA, Gene set variation analysis.

Fig. 8.

GSVA for risk group. Boxplot (a) and heat map (b) of GSVA results for group comparison between high-risk and low-risk groups. *Represents p-value < 0.05, statistically significant; ** represents p-value < 0.01 and is highly statistically significant. Screening criterion for GSVA was p < 0.05. High-(orange) and low-risk (yellow) groups.

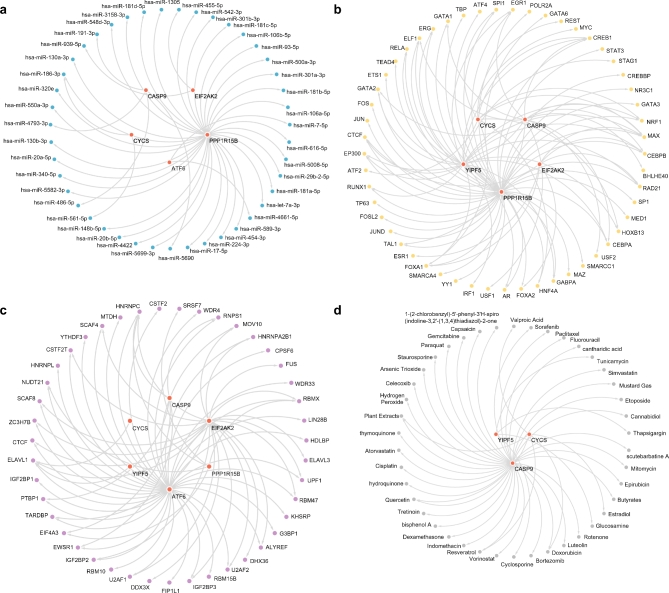

Construction of regulatory network

First, miRNAs associated with important genes, YIPF5, CASP9, PPP1R15B, EIF2AK2, CYCS, and ATF6, were extracted from TarBase, and a network of mRNA-miRNA regulation was constructed and displayed using Cytoscape (Fig. 9a). Among them, there were 5 key genes and 43 miRNAs, and the specific information is shown in Supplementary Table S3. Transcription factors (TFs) combined with key genes were found in the ChIPBase database, and Cytoscape was used to construct and visualize the mRNA-TF regulatory network (Fig. 9b). Among them, there were 5 key genes and 53 TFs (Supplementary Table S4). Thereafter, the RNA-binding protein (RBP) associated with the key genes was predicted using the StarBase database, and the mRNA-RBP regulatory network was constructed and visualized using Cytoscape (Fig. 9c). Among them, there were 6 key genes and 43 RBPs; specific information is shown in Supplementary Table S5. Finally, potential drugs or molecular compounds related to key genes were identified using the CTD database. Cytoscape software was used to construct and visualize the mRNA–drug regulatory network (Fig. 9d). Among them, there were 3 key genes and 42 drugs or molecular compounds (Supplementary Table S6).

Fig. 9.

Regulatory network of key genes. (a) mRNA-miRNA regulatory network of key genes. (b) mRNA-TF regulatory network of key genes. (c) mRNA-RBP regulatory network of key genes. (d) mRNA-drug regulatory network of key genes. mRNAs are shown in red, miRNAs in blue, TFs in yellow, RBP in purple, and drug targets in gray.

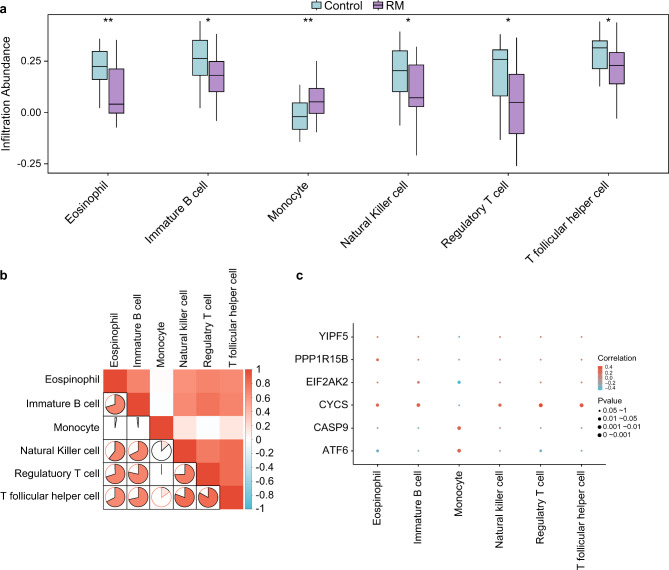

Analysis of immune infiltration in RM

The ssGSEA algorithm was used to calculate the immune infiltration abundance of the 28 immune cells by combining the expression matrices of the combined datasets. We first screened the immune cells with p-values of 0.05 using the group comparison plot and examined differences in immune cell infiltration abundance between groups. The group comparison chart (Fig. 10a) showed that eosinophilia and monocytes of two immune cells were highly statistically significant between the RM group and the control group (p < 0.01); four immune cells were immature B cells, and three immune cells were immature B cells. The numbers of natural killer (NK) cells, regulatory T cells, and T follicular helper cells were significantly different between the RM group and control group (p < 0.05). The correlation results of the combined datasets of six immune cell infiltration abundances in the immune infiltration analysis are illustrated in a heatmap (Fig. 10b). There was a positive correlation between immune cells. A correlation bubble diagram was used to display the relationship between the six key genes and the six immune cells (Fig. 10c). According to the results, most key genes, such as CYCS, are significantly correlated with immune cells.

Fig. 10.

Immune infiltration analysis by ssGSEA algorithm. (a) Immune cells in the RM and Control groups were compared. (b) Combined GEO data correlation heatmap of immune cell infiltration abundance. (c) An analysis of the correlation between key genes and immune cell infiltration abundance in the combined GEO datasets. *Represents p-value < 0.05, statistically significant; ** represents p-value < 0.01 and is highly statistically significant. Absolute values of the correlation coefficient (r-value) < 0.3 were weak or no correlation, 0.3 to 0.5 was a weak correlation, 0.5 to 0.8 was a moderate correlation, and above 0.8 was a strong correlation. In the group comparison diagram, the RM group is shown in purple, and the control group is shown in blue. In the correlation heatmap, red and blue represent positive and negative correlations, respectively.

Analysis of immune infiltration in high- and low-risk groups

Using the CIBERSORT algorithm, we calculated the correlation between 20 immune cell types and high- and low-risk groups of RM samples from the combined datasets. A bar chart of the proportion of immune cells in the combined datasets was drawn based on the results of the immune infiltration analysis (Supplementary Figure S5a). A correlation heatmap showing the infiltration abundance of 20 immune cells between the high- and low-risk groups in RM samples in the immune infiltration analysis is shown in Supplementary Figure S5b, c. A strong negative correlation was observed among most immune cells, whereas a positive correlation was observed among high-risk immune cells. Subsequently, correlation bubble plots were used to display the correlations between the 6 key genes and 20 immune cells (Supplementary Figure S5d, e). In the high-risk group, resting NK cells showed the strongest positive correlation with ATF6, and mast cell activation showed the strongest negative correlation with PPP1R15B. In the low-risk group, CD4 memory resting T cells and the key gene CYCS showed the strongest positive correlation. YIPF5 showed the strongest negative correlation with resting dendritic cells.

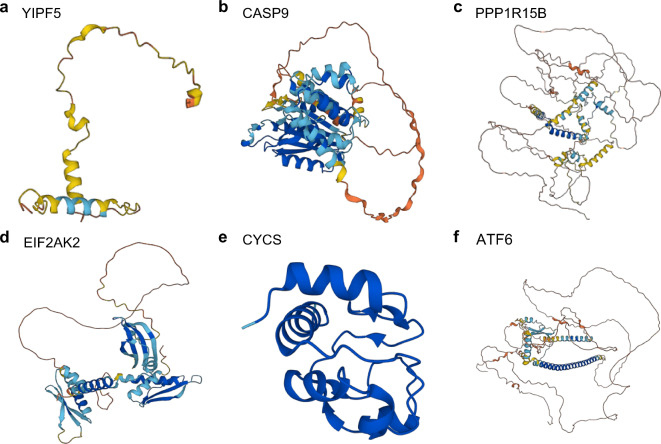

Prediction of protein domains

We used the AlphaFold website to analyze and display the protein results of six key genes in the diagnostic model: YIPF5 (Fig. 11a), CASP9 (Fig. 11b), PPP1R15B (Fig. 11c), EIF2AK2 (Fig. 11d), CYCS (Fig. 11e), and ATF6 (Fig. 11f).

Fig. 11.

Protein domain of key genes. (a–f) Protein domains of key genes YIPF5 (a), CASP9 (b), PPP1R15B (c), EIF2AK2 (d), CYCS (e), and ATF6 (f) are shown. AlphaFold protein structure database generated a confidence score per residue (pLDDT) between 0 and 100. Some regions below 50 pLDDT may be isolated unstructured regions, and when pLDDT < 50 (red area), the model confidence is very low; when 50 < pLDDT < 70 (yellow area), the model confidence is low; when 70 < pLDDT < 90 (light blue area), the model confidence was normal. When 90 < pLDDT (blue area), the model confidence is very high.

Discussion

RM affects approximately 1–2% of women of reproductive age, posing significant emotional distress and healthcare challenges12. Despite its prevalence, the underlying causes remain elusive in more than 50% of cases, often leading to the diagnosis of unexplained recurrent pregnancy loss. The complexity and multifactorial nature of RM highlight the urgent need for advanced research to unravel its pathophysiology and improve diagnostic accuracy, which could lead to better management strategies and therapeutic interventions. The integration of phenotypic data with molecular insights has been instrumental in enhancing our understanding of complex diseases such as RM. A previous study identified ERSRGs as involved in the pathogenesis of various reproductive disorders13.

We aimed to investigate the relationship between RM and ERS. ERSRDEGs were screened through differential expression analysis, and GO analysis, KEGG analysis, GSEA, and GSVA were performed. A prediction model was constructed using a machine-learning algorithm and LASSO, and a regulatory network was constructed. CIBERSORTx and ssGSEA algorithms were used for immune infiltration analysis. The aim of this study was to provide insights into the diagnosis and treatment of RM through a more comprehensive understanding of its molecular mechanism.

In this study, 17 ERSRDEGs were identified: BAX, ATF6, BCL2, P4HB, CASP9, EIF2AK2, PRNP, CYCS, TMEM33, BRSK2, UFC1, C6orf120, PDIA6, KEAP1, SREBF2, YIPF5, and PPP1R15B. The LASSO regression model identified six key diagnostic genes: YIPF5, CASP9, PPP1R15B, EIF2AK2, CYCS, and ATF6. LASSO regression can be used to select the best combination of predictive variables and build a robust diagnostic model. These key genes may be valuable in the diagnosis of RM.

The Bcl-2 family protein BAX plays a pivotal role in the intrinsic pathway of apoptosis by promoting mitochondrial outer membrane permeabilization14. Its involvement in ERS-induced apoptosis suggests that the dysregulation of BAX expression may contribute to the pathogenesis of RM by affecting cell survival and homeostasis15. The identification of BAX among the ERSRDEGs underscores its potential as a biomarker for RM diagnosis and a target for therapeutic interventions to modulate ERS pathways. ATF6, an essential regulator of the unfolded protein response (UPR), is activated when stress occurs in the ER16. ATF6 translocates to the Golgi apparatus during ERS, where it induces genes involved in the folding and degradation of proteins in the ER17. The differential expression of ATF6 in our study highlights its significance in RM pathophysiology and supports its utility as a diagnostic gene for assessing ERS-related disruptions in pregnancy. As an anti-apoptotic gene, BCL2 is integral to cellular resilience to various forms of stress, including ERS. It functions by inhibiting pro-apoptotic factors such as BAX and maintaining mitochondrial integrity18. The altered expression pattern of BCL2 observed among ERSRDEGs might reflect its role in preserving trophoblast viability and preventing miscarriages. Kelch-like ECH-associated protein 1 (KEAP1) negatively regulates the antioxidant response by targeting Nrf2 for ubiquitination and proteasomal degradation under homeostatic conditions19. Under oxidative or electrophilic stress, KEAP1 loses its ability to degrade Nrf2, allowing it to activate ARE-driven genes. The high diagnostic accuracy indicated by ROC analysis suggests that KEAP1 dysregulation may be critically involved in RM’s etiology through imbalances in oxidative stress responses20. Yip1 domain family member 5 (YIPF5) has been implicated in vesicular trafficking within cells. Although less studied than the other genes discussed in the present study, the significant AUC value of YIPF5 indicates that it may play a previously unrecognized role in placental biology or maternal–fetal interface stability. Furthermore, the inclusion of CASP9 in our diagnostic model reflects its importance not only as an indicator of apoptosis but also as a marker for aberrant cell death signaling contributing to RM pathology. PPP1R15B, also known as GADD34, participates in the recovery phase of the UPR by dephosphorylating eIF2α, thus resuming protein synthesis following ERS21. Its presence in our predictive model suggests that PPP1R15B-mediated regulation of translational control might be critical during the early pregnancy stages; disturbances here could lead to miscarriage.

The identification of ERSRDEGs in RM provides a novel perspective on the molecular mechanisms underlying this condition. Enrichment analysis of these ERSRDEGs revealed their significant involvement in cellular responses to ERS, protein processing, and apoptosis pathways. These biological processes are crucial for maintaining cellular homeostasis and proper protein folding and are often disrupted under ERS conditions22.

Prolonged or severe ERS could trigger apoptotic pathways23, which might contribute to RM by affecting placental development and function. The findings of the present study highlight the role of BAX, ATF6, and BCL2 in apoptotic signaling and suggest that any disruption in this process could contribute to RM pathogenesis. BAX is a pro-apoptotic member of the Bcl-2 family known for its role in mitochondrial membrane permeabilization and cytochrome release, leading to cell death24, whereas ATF6 is an ER membrane-bound TF that regulates UPR target genes25. The balance between pro-apoptotic and protective factors, such as BCL2, is critical for cell survival under stress.

The ROC curve analysis highlighted KEAP1 and YIPF5 as potential biomarkers with high diagnostic accuracy (AUC > 0.9). KEAP1, a component of the cellular antioxidant defense system, regulates NRF2 activity in response to oxidative stress26, whereas YIPF5’s role in vesicular trafficking suggests its importance in maintaining ER integrity and function27. The construction of diagnostic models incorporating key genes, such as YIPF5, CASP9, and PPP1R15B, demonstrates not only their individual significance but also their synergistic power. This enhanced the predictive accuracy of RM diagnosis and underscored the potential utility of ERSRDEGs as biomarkers for clinical applications.

In this study, the regulatory network was constructed based on bioinformatics methods and was not experimentally validated. Previous studies have assessed the accuracy and reliability of regulatory networks for idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis constructed by various methods, such as experimental data control, functional enrichment analysis, miRNA expression analysis, gene regulatory network construction, pathway crosstalk analysis, and creation of a dynamic system model, which revealed the pathological mechanism underlying idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis28,29. These studies provided research and clinical application support and can be used as a reference in our subsequent work to confirm the interactions between miRNAs and their target genes, TFs, and RBPs.

In our study, immune infiltration analysis revealed significant differences between RM patients and controls regarding the abundance of different immune cell types. Dysregulation of the immune system is crucial for RM pathogenesis30. Immune cells play a crucial role in RM, where they influence pregnancy maintenance and maternal–fetal immune tolerance through complex interactions. NK cells are most abundant at the maternal–fetal interface, accounting for approximately 70% of the metaphase immune cells31. The meconium NK cells can inhibit the cytotoxic T-cell damage response while promoting endometrial vascular remodeling, which facilitates trophoblast growth and modest invasion into the myometrium. Abnormalities in NK cell number and function are strongly associated with delayed endometrial development, infertility, and RM. Treg cells play an important immunosuppressive role at the maternal–fetal interface, suppressing both maternal specific and non-specific lymphocyte immune responses against the fetus through recruitment, induction, and proliferation32. The number and function of Treg cells are closely related to RM, and their immunosuppressive function contributes to the maintenance of maternal–fetal immune tolerance and the prevention of maternal rejection of the fetus. YIPF5 may be involved in intracellular processes such as substance transport and membrane vesicle formation, which are essential for immune cell activation and functional execution33. ATF6 may be involved in the regulation of immune-related gene expression. Under stressed conditions, ATF6 activation may affect the response and viability of immune cells, which in turn affects pregnancy maintenance and maternal–fetal immune tolerance34.

Our study also highlights the potential diagnostic value of certain ERSRDEGs. Genes such as KEAP1 and YIPF5 showed high accuracy (AUC > 0.9) in the ROC curve analyses for diagnosing RM. KEAP1 is a key regulator of oxidative stress responses35, whereas YIPF5 is involved in protein trafficking processes that can affect cellular homeostasis during stress conditions36.

The integration of immunological insights with molecular findings from ERSRDEGs provides a more comprehensive understanding of RM etiology. This suggests that therapeutic strategies targeting both molecular and immunological aspects are more effective. Our diagnostic models represent promising tools for early detection and intervention, potentially improving patient outcomes by enabling personalized treatment approaches based on individual immunogenetic profiles.

Although this study provides valuable insights into the relationship between ERSRGs and RM, there were some limitations that should be considered. First, the selected datasets contained data generated through microarrays. Although the datasets performed well in terms of stability and reliability, they may not reflect the detailed information available in data derived from the latest gene expression technologies (e.g., RNA sequencing). Second, the results of the study are based on existing data, which may be affected by factors such as sample source, population heterogeneity, and experimental conditions. In addition, the study mainly focused on specific biomarkers, meaning that we may have overlooked other potential molecular regulators. Finally, this study was based on an observational analysis; thus, further experimental studies are needed to verify the causality of the results. In the future, we plan to use high-throughput sequencing technology to explore a wider range of gene expression features and regulatory mechanisms.

In conclusion, the identification of ERSRDEGs and their association with patterns of immune response is an important step toward improving diagnostic and therapeutic strategies for RM. The discovery of key genes not only reveals potential biomarkers but also provides new molecular perspectives on the pathogenesis of RM. Understanding the complex interactions between these molecular factors and the body’s immune environment will be key to developing effective interventions. Particularly in a multifactorial disease such as RM, the balance of the immune system and adaptation of the internal and external environments strongly influence the success of pregnancy.

In the future, more comprehensive and integrated clinical studies incorporating our findings will be crucial. Such studies can validate the applicability and effectiveness of ERSRDEGs in real cases, as well as helping to reveal the interactions between different genes and between genes and immune responses, resulting in a more complex biological network model. Such comprehensive studies will also provide a deeper understanding of the pathophysiological mechanisms underlying RM and advance the development of individualized medicine. The ultimate aim would be to develop personalized treatment plans based on a patient’s unique immunogenomic profile. Through this approach, we will be able to more effectively predict and prevent RM and provide better medical support and improved prognosis for women affected by this disease. This will have far-reaching implications for improving women’s quality of life and psychological well-being.

Methods

Data acquisition

The batch effect analysis included the use of multiple databases and R packages to ensure the quality of the datasets, integrating RM through a stepwise process. Firstly, RM-related datasets GSE2249037 and GSE16500438 (Table 4) were downloaded from the GEO database via the R package GEOquery39. These datasets contain data from Homo sapiens tissue originating from the placenta collected via the microarray platforms GPL570 and GPL16699, respectively. GSE22490 contains four RM samples and six induced abortion samples, whereas GSE165004 contains 24 RM samples, 24 unexplained infertility samples, and 24 control samples. To screen for ERS-related genes, the GeneCards database and PubMed literature were used, with ‘Endoplasmic Reticulum Stress’ as a keyword, resulting in 198 related genes. To eliminate the batch effect in the dataset, the R package sva40 was used, and the integrated dataset consisted of 28 RM samples and 24 control samples. The integrated dataset was normalized and variance analyzed using the R package limma41. ERSRDEGs were finally screened out for subsequent heat map visualization and chromosomal localization analysis. Thus, the combined use of these databases and R packages effectively reduced the impact of batch effects on the study results and provided a solid foundation for analyzing the biological mechanisms underlying RM-associated ERS. PCA was performed on expression matrices42.

Table 4.

GEO microarray chip information.

| GSE22490 | GSE165004 | |

|---|---|---|

| Platform | GPL570 | GPL16699 |

| Species | Homo sapiens | Homo sapiens |

| Tissue | Placenta | Placenta |

| Samples in the RM group | 4 | 24 |

| Samples in the Control group | / | 24 |

| Reference | PMID: 23,290,504 | PMID: 36,369,952 |

GEO, Gene Expression Omnibus; RM, recurrent miscarriage.

Identification of genes related to RM-associated ERS

The GeneCards database (https://www.genecards.org) and related literature were used to identify the ERSRGs. Our search term was “Endoplasmic Reticulum Stress.” A total of 190 ERSRGs were obtained after keeping only the ERSRGs with “Protein Coding” and “Relevance Score > 4”. Similarly, a total of 26 ERSRGs were obtained from PubMed using “Endoplasmic Reticulum Stress” as a keyword43. A total of 198 ERSRGs were obtained after combined deduplication (Supplementary Table S7).

There were two groups of samples in the combined dataset: RM and control. Gene expression levels in the RM and control groups were compared using the R package limma. Upregulated genes had logFC > 0.25 and adj.p < 0.05, and downregulated genes had logFC < − 0.25 and adj.p < 0.05. Differential analysis results were visualized using a volcano plot in the R package ggplot2. To obtain ERSRDEGs associated with RM, the DEGs obtained by variance analysis of all | logFC | > 0.25 and adj. p < 0.05. In the combined datasets, ERSRGs with p < 0.05 were intersected and illustrated using a Venn diagram. Expression patterns were visualized via ‘pheatmap’ heatmaps, and their chromosomal locations were mapped with the ‘RCircos’ R package44.

Differential expression and ROC curve analysis

In the combined datasets, we further explored the differential expression of ERSRDEGs in the RM group compared to the control group. A comparison map was drawn based on the expression levels of ERSRDEGs. We plotted the ROC curves of the ERSRDEGs and calculated the AUC using pROC in the R package. To evaluate the diagnostic effect of ERSRDEGs expression in RM, the AUC under the ROC curve ranged from 0.5 to 1. The accuracy was low when the AUC was between 0.5 and 0.7, moderate when the AUC was between 0.7 and 0.9, and high when the AUC was above 0.9.

GO and KEGG pathway enrichment analyses

It is common to perform GO analysis45 on BP, CC, and MF. KEGG provides information on genomes, biological pathways, diseases, and drugs. ClusterProfiler46 was used to analyze the GO and pathway enrichment of ERSRDEGs. As a statistically significant item, adj.p < 0.05 and FDR value (q value) < 0.25 were used. The Benjamini–Hochberg (BH) test was used to correct the p-values. To visualize the pathway map related to pathway enrichment analysis, we used the R package Pathview47.

Model construction and validation

To generate RM diagnostic models based on the combined datasets, ERSRDEGs were analyzed using logistic regression. We used a p-value < 0.05 to screen for ERSRDEGs and construct a logistic regression model. To construct the SVM model, the SVM algorithm was used48 based on the ERSRDEGs in the logistic regression model. The LASSO risk score was calculated as follows:

|

The combined GEO dataset ROC curves and AUC values were plotted in R using the package pROC. FRIENDS analysis (functional similarity analysis) was performed using the R package GOSemSim49 to evaluate the diagnostic effect of the LASSO RiskScore on RM. Nomograms50 can be used to represent the functional relationships between multiple variables in rectangular coordinate systems. We used a calibration analysis to evaluate the accuracy and discrimination of the RM diagnostic model. Based on the RiskScore, decision curve analysis (DCA) graphs were drawn using the R package ggDCA.

GSEA and GSVA for the DEGs

The genes in the RM samples from the combined GEO datasets were sorted using logFC values. Thereafter, we performed GSEA51 on all genes from the RM samples of the combined datasets using the R package clusterProfiler. The GSEA parameters were as follows: seed: 2020; number of computations: 1000; minimum number of genes per gene set: 10; and maximum number of genes per gene set: 500. We used the Molecular Signatures Database (MSigDB)52 to access c2.all.v2022.1. Hs.symbols.gmt [curated/pathway] (6449) for GSEA. In GSEA, the screening criteria were adjusted to p < 0.05, FDR value (q value) < 0.25, and the p-value correction method was BH. We used the MSigDB Database to access c2.cgp.v2023.2. The gmt gene set of the combined datasets GSVA53 was performed on all genes of the datasets to calculate the difference in functional enrichment between the RM and control groups. The screening criteria for GSVA were adjusted to p < 0.05, and the p-value correction method used was BH.

Multi-factor regulation network construction

The miRNAs related to the key genes were obtained from the TarBase54 database. Only miRNAs with “direct_indirect = DIRECT” and “condition = no treatment (control)” were retained. We visualized the mRNA-miRNA regulatory network using the Cytoscape software. Only TFs with the sum of “Number of samples found (upstream)” and “Number of samples found (downstream)” greater than 8 were retained by searching for TFs in the ChIPBase database55. Based on the StarBase v3.0 database56, the target RBP of key genes was predicted. Finally, the CTD database was utilized to forecast the direct and indirect drug targets of key genes, with visualization of the mRNA-miRNA, mRNA-TF, and mRNA-RBP regulatory networks using Cytoscape.

Infiltration of immune cells

GEO expression profile data were used to measure the presence of immune cells through single-sample GSEA. Activated CD8 + T cells, dendritic cells, gamma delta T cells, NK cells, and regulatory T cells were labeled during infiltration. Secondly, enrichment scores were calculated using ssGSEA to determine the relative abundance of immune cell infiltration. The CIBERSORT57 algorithm was used along with the LM22 feature gene matrix to filter out data with immune cell enrichment scores greater than 0; thereafter, we obtained the specific results of the immune cell infiltration matrix. Finally, correlation heat maps were drawn using the R pheatmap package to show correlations between LM22 immune cells and key genes.

Prediction of protein domain

We used the AlphaFold protein structure database58 to predict and visualize the protein structures of key genes in the diagnostic model. The AlphaFold protein structure database generates a confidence score per residue, and the predicted local distance difference test (pLDDT) is between 0 and 100. Some regions below 50 pLDDT may be isolated as unstructured regions, and when pLDDT < 50 (red area), the model confidence is extremely low. When 50 < pLDDT < 70 (yellow area), the confidence of the model is low. When 70 < pLDDT < 90 (light blue area), the confidence of the model was normal. When 90 < pLDDT (blue area), the confidence of the model was very high.

Statistical analysis

R 4.3.0 was used to process and analyze all data in this study. Continuous variables are presented as means ± SD. The two groups were compared using the Wilcoxon rank-sum test. Unless otherwise specified, the results were calculated as Spearman correlation coefficients between different molecules. Significant difference: p < 0.05.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

This research was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China, Grant Number 82004134 to Xiaodan Yin, and Beijing Natural Science Foundation, Grant Number 7242218 to Xiaodan Yin.

Author contributions

Methodology, W.Y., M.X., and Q.H.; validation, Q.H.; formal analysis, S.G.; investigation, X.Y., W.Y., M.X., and Q.H.; data curation, W.Y., M.X., and Q.H.; writing-original draft preparation, X.Y.; writing-review and editing, J.H.; visualization, X.Y., W.Y. and Q.H.; supervision, J.H. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Data availability

Data for this study are included in the article/supplemental information or are publicly available in the GEO database: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/query/acc.cgi? acc=GSE22490, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/query/acc.cgi? acc=GSE165004.

Declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Practice Committee of the American Society for Reproductive Medicine. Definitions of infertility and recurrent pregnancy loss: A committee opinion. Fertil. Steril.99, 63 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rai, R. & Regan, L. Recurrent miscarriage. Lancet. 368, 601–611 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Biaggi, A., Conroy, S., Pawlby, S. & Pariante, C. M. Identifying the women at risk of antenatal anxiety and depression: A systematic review. J. Affect. Disord. 191, 62–77 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Christiansen, O. B. et al. ESHRE guideline: Recurrent pregnancy loss. Hum. Reprod. Open.2, hoy004 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Oakes, S. A. & Papa, F. R. The role of endoplasmic reticulum stress in human pathology. Annu. Rev. Pathol.10, 173–194 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hetz, C. & Papa, F. R. The unfolded protein response and cell fate control. Mol. Cell.69, 169–181 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zhang, H., Zhu, Y., Suehiro, Y., Mitani, S. & Xue, D. AMPK-FOXO-IP3R signaling pathway mediates neurological and developmental defects caused by mitochondrial DNA mutations. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 120, e2302490120 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 8.Kasamatsu, A. et al. Deficiency of lysyl hydroxylase 2 in mice causes systemic endoplasmic reticulum stress leading to early embryonic lethality. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun.512, 486–491 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jung, E. M., An, B. S., Choi, K. C. & Jeung, E. B. Apoptosis- and endoplasmic reticulum stress-related genes were regulated by estrogen and progesterone in the uteri of calbindin-D(9k) and -D(28k) knockout mice. J. Cell. Biochem.113, 194–203 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kanehisa, M. & Goto, S. Kyoto encyclopedia of genes and genomes. Nucleic Acids Res.28, 27–30 (2000). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zhong, Y. C. et al. Integrative analyses of potential biomarkers and pathways for non-obstructive azoospermia. Front. Genet.13, 988047 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kolte, A. M. et al. Terminology for pregnancy loss prior to viability: A consensus statement from the ESHRE early pregnancy special interest group. Hum. Reprod.30, 495–498 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Salker, M. S. et al. Disordered IL-33/ST2 activation in decidualizing stromal cells prolongs uterine receptivity in women with recurrent pregnancy loss. PLOS ONE. 7, e52252 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Oltvai, Z. N., Milliman, C. L. & Korsmeyer, S. J. Bcl-2 heterodimerizes in vivo with a conserved homolog, Bax, that accelerates programmed cell death. Cell. 74, 609–619 (1993). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lebeaupin, C., Blanc, M., Vallée, D. & Keller, H. Bailly-Maitre, B. BAX inhibitor-1: Between stress and survival. FEBS J.287, 1722–1736 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Haze, K., Yoshida, H., Yanagi, H., Yura, T. & Mori, K. Mammalian transcription factor ATF6 is synthesized as a transmembrane protein and activated by proteolysis in response to endoplasmic reticulum stress. Mol. Biol. Cell.10, 3787–3799 (1999). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ye, J. et al. ER stress induces cleavage of membrane-bound ATF6 by the same proteases that process SREBPs. Mol. Cell.6, 1355–1364 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cory, S., Huang, D. C. S. & Adams, J. M. The Bcl-2 family: Roles in cell survival and oncogenesis. Oncogene. 22, 8590–8607 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Itoh, K. et al. Keap1 represses nuclear activation of antioxidant responsive elements by Nrf2 through binding to the amino-terminal Neh2 domain. Genes Dev.13, 76–86 (1999). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wang, X. J. et al. Nrf2 enhances resistance of cancer cells to chemotherapeutic drugs, the dark side of Nrf2. Carcinogenesis. 29, 1235–1243 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Boyce, M. et al. A selective inhibitor of eIF2⍺ dephosphorylation protects cells from ER stress. Science. 307, 935–939 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hetz, C., Chevet, E. & Harding, H. P. Targeting the unfolded protein response in disease. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 12, 703–719 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Szegezdi, E., Logue, S. E., Gorman, A. M. & Samali, A. Mediators of endoplasmic reticulum stress-induced apoptosis. EMBO Rep.7, 880–885 (2006). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Youle, R. J. & Strasser, A. The BCL-2 protein family: Opposing activities that mediate cell death. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell. Biol.9, 47–59 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yoshida, H., Matsui, T., Yamamoto, A., Okada, T. & Mori, K. XBP1 mRNA is induced by ATF6 and spliced by IRE1 in response to ER stress to produce a highly active transcription factor. Cell. 107, 881–891 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Taguchi, K., Motohashi, H. & Yamamoto, M. Molecular mechanisms of the Keap1–Nrf2 pathway in stress response and cancer evolution. Genes Cells. 16, 123–140 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.De Franco, E. D. et al. YIPF5 mutations cause neonatal diabetes and microcephaly through endoplasmic reticulum stress. J. Clin. Invest.130, 6338–6353 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gangwar, I. et al. Detecting the molecular system signatures of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis through integrated genomic analysis. Sci. Rep.7, 1554 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Randhawa, V. & Kumar, M. An integrated network analysis approach to identify potential key genes, transcription factors, and microRNAs regulating human hematopoietic stem cell aging. Mol. Omics. 17, 967–984 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Seshadri, S. & Sunkara, S. K. Natural killer cells in female infertility and recurrent miscarriage: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Hum. Reprod. Update. 20, 429–438 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sharma, S. Natural killer cells and regulatory T cells in early pregnancy loss. Int. J. Dev. Biol.58, 219–229 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Somerset, D. A., Zheng, Y., Kilby, M. D., Sansom, D. M. & Drayson, M. T. Normal human pregnancy is associated with an elevation in the immune suppressive CD25+ CD4+ regulatory T-cell subset. Immunology. 112, 38–43 (2004). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ran, Y. et al. YIPF5 is essential for innate immunity to DNA virus and facilitates COPII-dependent STING trafficking. J. Immunol.203, 1560–1570 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Conza, G. D., Ho, P. C. & Stress, E. R. Responses: An emerging modulator for innate immunity. Cells. 9, 695 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hayes, J. D. & Dinkova-Kostova, A. T. The Nrf2 regulatory network provides an interface between redox and intermediary metabolism. Trends Biochem. Sci.39, 199–218 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Grieve, A. G. & Rabouille, C. Golgi bypass: Skirting around the heart of classical secretion. Cold Spring Harb Perspect. Biol.3, a005298 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rull, K. et al. Increased placental expression and maternal serum levels of apoptosis-inducing TRAIL in recurrent miscarriage. Placenta. 34, 141–148 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Keleş, I. D. et al. Gene pathway analysis of the endometrium at the start of the window of implantation in women with unexplained infertility and unexplained recurrent pregnancy loss: Is unexplained recurrent pregnancy loss a subset of unexplained infertility? Hum. Fertil. (Camb). 26, 1129–1141 (2023). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Davis, S. M. P. & Meltzer, P. S. GEOquery: A bridge between the Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) and BioConductor. Bioinformatics. 23, 1846–1847 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Leek, J. T., Johnson, W. E., Parker, H. S., Jaffe, A. E. & Storey, J. D. The sva package for removing batch effects and other unwanted variation in high-throughput experiments. Bioinformatics. 28, 882–883 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ritchie, M. E. et al. limma powers differential expression analyses for RNA-sequencing and microarray studies. Nucleic Acids Res. 43, e47 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 42.Ben Salem, K. & Ben Abdelaziz, A. Principal component analysis (PCA). Tunis Med.99, 383–389 (2021). [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Shen, Y., Cao, Y., Zhou, L., Wu, J. & Mao, M. Construction of an endoplasmic reticulum stress-related gene model for predicting prognosis and immune features in kidney renal clear cell carcinoma. Front. Mol. Biosci.9, 928006 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Zhang, H., Meltzer, P. & Davis, S. RCircos: An R package for Circos 2D track plots. BMC Bioinform.14, 244 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Mi, H., Muruganujan, A., Ebert, D., Huang, X. & Thomas, P. D. PANTHER version 14: More genomes, a new PANTHER GO-slim and improvements in enrichment analysis tools. Nucleic Acids Res.47, D419–D426 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Yu, G., Wang, L. G., Han, Y. & He, Q. Y. clusterProfiler: An R package for comparing biological themes among gene clusters. Omics. 16, 284–287 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Luo, W. & Brouwer, C. Pathview: An R/Bioconductor package for pathway-based data integration and visualization. Bioinformatics. 29, 1830–1831 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Sanz, H., Valim, C., Vegas, E., Oller, J. M. & Reverter, F. SVM-RFE: Selection and visualization of the most relevant features through non-linear kernels. BMC Bioinform.19, 432 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Berman, H. M. et al. The Protein Data Bank. Nucleic Acids Res.28, 235–242 (2000). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wu, J. et al. A nomogram for predicting overall survival in patients with low-grade endometrial stromal sarcoma: A population-based analysis. Cancer Commun. (Lond). 40, 301–312 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Subramanian, A. et al. Gene set enrichment analysis: A knowledge-based approach for interpreting genome-wide expression profiles. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A. 102, 15545–15550 (2005). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Liberzon, A. et al. Molecular signatures database (MSigDB) 3.0. Bioinformatics. 27, 1739–1740 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Hänzelmann, S., Castelo, R. & Guinney, J. GSVA: Gene set variation analysis for microarray and RNA-seq data. BMC Bioinform.14, 7 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Vlachos, I. S. et al. Diana-TarBase v7.0: Indexing more than half a million experimentally supported miRNA:mRNA interactions. Nucleic Acids Res.43, D153–D159 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Zhou, K. R. et al. ChIPBase v2.0: Decoding transcriptional regulatory networks of non-coding RNAs and protein-coding genes from ChIP-seq data. Nucleic Acids Res.45, D43–D50 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Li, J. H., Liu, S., Zhou, H., Qu, L. H. & Yang, J. H. starBase v2.0: Decoding miRNA-ceRNA, miRNA-ncRNA and protein-RNA interaction networks from large-scale CLIP-Seq data. Nucleic Acids Res.42, D92–D97 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Newman, A. M. et al. Robust enumeration of cell subsets from tissue expression profiles. Nat. Methods. 12, 453–457 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Jumper, J. et al. Highly accurate protein structure prediction with AlphaFold. Nature. 596, 583–589 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Data for this study are included in the article/supplemental information or are publicly available in the GEO database: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/query/acc.cgi? acc=GSE22490, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/query/acc.cgi? acc=GSE165004.