Abstract

Numerous tick species are undergoing significant range expansion in Canada, including several Dermacentor spp Koch (Acari: Ixodidae). With the recent description of Dermacentor similis Lado in the western United States, additional research is required to determine the current range of this species. Five hundred ninety-eight Dermacentor spp. were collected from companion animals in the western Canadian provinces of British Columbia, Alberta, and Saskatchewan. Ticks were morphologically identified to species, followed by PCR and gel electrophoresis of the ITS-2 partial gene target (n = 595). Ninety-seven percent (n = 579/595) generated valid banding patterns. The banding pattern for the majority (74%, n = 206/278) of Dermacentor spp. from southern British Columbia was consistent with D. variabilis (Say), while 26% (n = 72/278) was consistent with D. andersoni Stiles. For samples from Alberta, 38% (n = 3/8) had banding patterns consistent with D. variabilis and 63% (n = 5/8) with D. andersoni. All (n = 293) ticks from Saskatchewan had banding patterns consistent with D. variabilis. After the description of D. similis was published, DNA sequencing of mitochondrial (16S rDNA gene, COI gene) and nuclear (ITS-2) markers was used to confirm the identity of 40 samples. Twenty-seven samples that had banding patterns consistent with D. variabilis from British Columbia were confirmed to be D. similis. One sample from Alberta and five from Saskatchewan were confirmed to be D. variabilis and seven samples from British Columbia were D. andersoni. The ITS-2 amplicons were not useful for differentiating between D. variabilis and D. similis. These results provide evidence of D. similis in western Canada and highlight that sequences of the mitochondrial genes are effective for distinguishing D. andersoni, D. variabilis, and D. similis.

Keywords: Dermacentor species, western Canada, companion animals

Introduction

Understanding the changing distribution of Dermacentor spp. Koch (Acari: Ixodidae) is important, as they affect the health and welfare of humans and domestic animals (Lindquist et al. 2016). For example, D. variabilis (Say) and D. andersoni Stiles are vectors of pathogens of human and animal health significance, including Francisella tularensis, the causative agent of tularemia, and Rickettsia rickettsii, the causative agent of Rocky Mountain spotted fever (Burgdorfer 1975, Telford and Goethert 2020). Rickettsia rickettsii has only been detected at very low infection prevalence in Dermacentor populations in Canada (Dergousoff et al. 2009, Lindquist et al. 2016).

In North America, several tick species, including some Dermacentor species, have been undergoing significant geographic range expansion, which has been facilitated by climatic and land use changes, coupled with ongoing human and animal movement (Dergousoff et al. 2016, Slabach et al. 2018, Nelder et al. 2022). Prior to the 1970s, the known geographic range of D. variabilis in Canada extended from eastern Saskatchewan eastward to the Atlantic provinces, and the range of D. andersoni extended from southern British Columbia to western Saskatchewan (Cooley 1938, Gregson 1956, Wilkinson 1967, Lindquist et al. 2016). However, D. variabilis populations have been undergoing northward and westward range expansion, so these historical ranges do not adequately reflect the current distribution (Dergousoff et al. 2013, Nelder et al. 2022) and ongoing research is needed.

In the United States, populations of D. variabilis in the west have long been considered genetically distinct from eastern populations (Krakowetz et al. 2010, Kaufman et al. 2018, Lado et al. 2019, Duncan et al. 2021). Recent work, based on an integrated morphological and molecular approach, has proposed that this western population is a distinct species, Dermacentor similis Lado (Lado et al. 2021). Determining the current distribution of D. similis is needed to assess the risk of exposure and is a foundational step in reassessing phenology, host associations, and vector competence, in comparison to D. variabilis.

The range of D. similis in Canada is obscure and requires elucidation. Therefore, the primary objective of this study was to describe Dermacentor species presence in western Canada. Additional study objectives were to test molecular techniques to determine which could be used to differentiate Dermacentor species and describe the infection prevalence of R. rickettsii in Dermacentor spp. from western Canada.

Methods

Sample Collection

Samples were collected through a national study of ticks on companion animals, called the Canadian Pet Tick Survey (CPTS). Veterinary clinics were invited to participate in the CPTS in February 2019. Information about the study was shared via websites (e.g., www.petsandticks.com), presentations (e.g., Ontario Veterinary Medical Association conference), and provincial veterinary associations. Clinics were enrolled until provincial targets were reached (see DeWinter et al. 2023). Participating clinics were requested to submit all ticks collected from companion animals for one year (April 2019 to March 2020). Each submission was accompanied by a questionnaire that documented the suspected geographic location of tick acquisition and the pet’s travel history. One submission is defined as all the ticks collected from an individual companion animal at one time point.

Reference Samples

Additional samples were acquired as reference material for genetic identification. Samples were provided by collaborators in British Columbia (D. andersoni) and the USA (D. similis). Adult D. andersoni were collected from British Columbia by tick drag sampling as part of the Canadian Lyme Sentinel Network (Guillot et al. 2020). The samples from the USA consisted of genomic DNA extracted from adult ticks that were also collected via drag sampling within three western states: California (6 samples), Washington (2 samples), and Oregon (2 samples) (Lado et al. 2019, 2021).

Morphological Identification

Morphological identification was completed to the species level using a stereoscope and a tick identification key (Lindquist et al. 2016). Molecular identification was pursued to validate Dermacentor spp. morphological identification (with the exception of D. albipictus (Packard)), as findings sharply contrasted with previous research on known Dermacentor spp. distribution (Cooley 1938, Gregson 1956, Wilkinson 1967, Dergousoff et al. 2013, Lindquist et al. 2016).

Molecular Identification

Ticks were stored in 70% ethanol following morphological identification. The tick samples were macerated using a scalpel blade and total genomic DNA was purified using the QIAGEN DNEasy Blood and Tissue Kit (Qiagen Inc., Mississauga, Canada), as per the manufacturer’s protocol for animal tissues. A maximum of five ticks from a submission that were identified to be of the same genus and sex were pooled prior to PCR. In cases where there were greater than five from a submission, the ticks were divided into multiple sample pools. Therefore, the term “sample” refers to both pooled ticks that were combined prior to DNA extraction and single tick submissions.

Preliminary identification was conducted via PCR amplification of part of the nuclear internal transcribed spacer 2 region (ITS-2), as per Dergousoff and Chilton (2007). The ITS-2 amplicon for D. andersoni is approximately 70 base pairs longer than for D. variabilis; thus, the resulting banding pattern produced via gel electrophoresis of the PCR product can assist in species differentiation (Dergousoff and Chilton 2007).

Following the description of D. similis as a distinct species (Lado et al. 2021), further molecular analyses were pursued to identify Dermacentor specimens as it was not known if the ITS-2 amplicon was sufficient to differentiate between D. similis and D. variabilis. Single tick samples were prioritized, but occasionally pooled samples were used. A maximum of three samples from the same submission were sent for Sanger sequencing. Only samples from submissions where there was no reported travel history were included.

To have a comparison group of D. variabilis samples for molecular analyses, a subset of morphologically identified D. variabilis samples that were submitted as part of the CPTS from the provinces of Manitoba and eastward were also included in DNA sequencing. Sanger sequencing of two mitochondrial markers, COI gene and 16S rDNA gene, and one nuclear marker, ITS-2, was conducted using previously described forward and reverse primers (Folmer et al. 1994, Norris et al. 1996, 1999, Dergousoff and Chilton 2007, Kaufman et al. 2018). For each of these provinces, genomic DNA from a minimum of five ticks, or 5%, whichever was greater, of the submitted D. variabilis from the province were sent for DNA sequencing. In cases where less than five D. variabilis were submitted from a province, genomic DNA from all ticks from the province was sent for sequencing.

Pathogen Testing

Using real-time qPCR, samples were tested for R. rickettsii using the primers (RRi6_F, RRi6_R) and probe (RRi6_P), as described by Kato et al. (2013). Samples with a cycle threshold value below 40 were classified as positive, and a positive synthetic control (gBlock) (Integrated DNA Technologies, Coralville, United States) and negative control (water) were included in each run (Kato et al. 2013).

Data Analysis

The forward and reverse sequences for each target were trimmed and assembled in Geneious Prime 2023.1.2 (https://geneious.com). In cases where only one direction of sequence was generated, the sequence was trimmed but not paired. Nucleotide sequences were aligned using MAFFT Version 7 (https://mafft.cbrc.jp/alignment/server/) and viewed in MEGA (Version 11.0.13, https://www.megasoftware.net, Tamura et al. 2021). Data display networks were generated in SplitsTree4 (Version 4.19.2, https://software-ab.cs.uni-tuebingen.de/download/splitstree4/welcome.html, Huson and Bryant 2006) from uncorrected p-distances and all characters. Bootstrap support was calculated from 1000 replicates.

The geographic coordinates for each tick, as reported from the CPTS, were spatially projected using QGIS software (Version 3.10.8, http://qgis.org). Only submissions that included specific information on the location of tick acquisition were included. In cases where the suspected location of tick acquisition was described and there was no reported travel history, the sample was mapped to the described location. In cases where the location was described unclearly (e.g., backyard), the sample was mapped to the submitting clinic. If there was a history of travel and the suspected location of tick acquisition matched the travel history, the sample was mapped to the travel location. In all other cases (e.g., if it was unknown if the tick was acquired during travel or not), the sample was not included in the spatial description.

Results

Species Identification

In total, 598 adult Dermacentor specimens were submitted from dogs and cats from British Columbia (n = 292), Alberta (n = 9), and Saskatchewan (n = 297). Of the 598 samples, 3 were identified as D. albipictus: 2 from British Columbia and 1 from Alberta. Further morphological and molecular examination of these samples is described by Duncan et al. (2020). Based on ITS-2 PCR and gel electrophoresis, 77 ticks had banding patterns consistent with D. andersoni and 502 had banding patterns consistent with D. variabilis. Of the samples consistent with D. andersoni, 72 were submitted from British Columbia and 5 from Alberta. Of the samples consistent with D. variabilis, 206 were submitted from British Columbia, 3 from Alberta, and 293 from Saskatchewan. Sixteen Dermacentor ticks (12 from British Columbia and 4 from Saskatchewan) were not able to be identified to species due to inconclusive banding results.

Sanger sequencing was conducted on a subset of samples from each western province (n = 47) (Table 1), as well as the reference samples (British Columbia: n = 24, USA: n = 10), and a subset of samples collected from eastern Canada (Manitoba: n = 20, Ontario: n = 19, Quebec: n = 5, New Brunswick: n = 1, Nova Scotia: n = 21, Prince Edward Island: n = 3). Valid sequences were not generated for all markers for all samples. Seven samples from the western provinces had no valid sequences generated and were not able to be differentiated.

Table 1.

The total number of Dermacentor spp. samples from each western province that underwent PCR of the ITS-2 partial gene target and gel electrophoresis, and Sanger sequencing of three gene fragments. A sample may consist of one or multiple (two to five) ticks. Dermacentor albipictus samples are not included in this table.

| Total number of ticks received | ITS-2 PCR and gel electrophoresis | ITS-2 species identification | Sanger sequencing | Species identitya | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of samples | Individual samples | Pooled samples | Number of samples | Individual samples | Pooled samples | ||||

| Study Samples | |||||||||

| British Columbia | 290 | 206 | 160 | 46 | 206 D. variabilis 72 D. andersoni 12 undetermined |

39 | 20 | 19 | 27 D. similis 7 D. andersoni 5 undetermined |

| Alberta | 8 | 8 | 8 | 0 | 3 D. variabilis 5 D. andersoni |

1 | 1 | 0 | 1 D. variabilis |

| Saskatchewan | 297 | 122 | 55 | 67 | 293 D. variabilis 4 undetermined |

7 | 5 | 2 | 5 D. variabilis 2 undetermined |

| Reference Samples | |||||||||

| Eastern Canada | – | – | – | – | – | 69 | 69 | 0 | 67 D. variabilis 2 undetermined |

| British Columbia | – | – | – | – | – | 24 | 24 | 0 | 24 D. andersoni |

| United States | – | – | – | – | – | 10 | 10 | 0 | 9 D. similis 1 undetermined |

aMitochondrial markers (16S rDNA and/or COI) were used to differentiate D. variabilis and D. similis. Mitochondrial and/or nuclear markers (16S rDNA, COI, and/or ITS-2) were used to confirm D. andersoni.

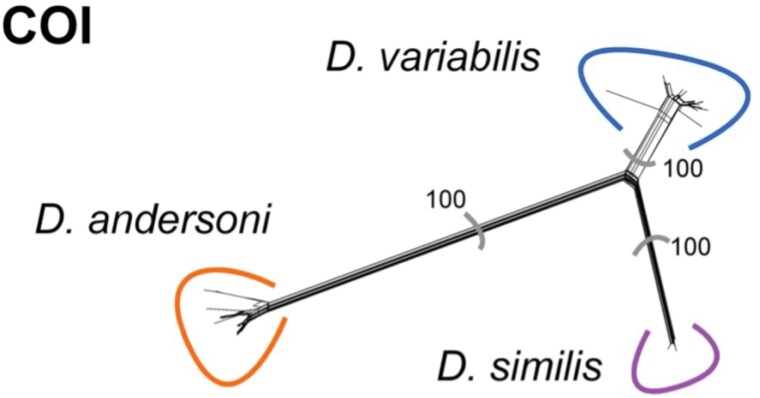

Network analysis resulted in three distinct groupings based on bootstrapping results and uncorrected p-distances when analyzing the mitochondrial markers, i.e., 16S rDNA (Fig. 1) and COI (Fig. 2). All the samples from southern British Columbia that produced ITS-2 banding patterns consistent with D. variabilis grouped with the reference D. similis samples from the USA. Samples from Alberta and Saskatchewan that had banding patterns consistent with D. variabilis grouped with the samples of D. variabilis from the provinces of Manitoba and eastwards. The samples that had banding patterns consistent with D. andersoni from British Columbia grouped with the reference samples of D. andersoni from British Columbia. The nuclear marker, ITS-2, could be used to differentiate D. andersoni samples from D. variabilis and D. similis, but the latter two species could not be differentiated from each other (Fig. 3), forming a cluster comprising only D. similis and a cluster comprising both D. similis and D. variabilis. Therefore, only samples that had valid sequences for at least one of the two mitochondrial markers were considered conclusive results for the differentiation of D. variabilis and D. similis. A valid sequence for any of the three markers was considered conclusive results for D. andersoni.

Fig. 1.

Network created using the COI mitochondrial marker. Line length is calculated from uncorrected p-distances and represents the genetic distance between sequences. Bootstrap values are indicated for each split (1000 replicates). Samples of D. variabilis (n = 68 total (n = 5 study samples, n = 63 reference samples)) are clustered to the top right, D. similis (n = 28 total (n = 21 study samples, n = 7 reference samples)) to the bottom right, and D. andersoni (n = 28 total (n = 4 study samples, n = 24 reference samples)) to the bottom left.

Fig. 2.

Network created using the 16S rDNA mitochondrial marker. Line length is calculated from uncorrected p-distances and represents the genetic distance between sequences. Bootstrap values are indicated for each split (1000 replicates). Samples of D. variabilis (n = 73 total (n = 6 study samples, n = 67 reference samples)) are clustered to the top right, D. similis (n = 34 total (n = 25 study samples, n = 9 reference samples)) to the bottom right, and D. andersoni (n = 28 total (n = 4 study samples, n = 24 reference samples)) to the bottom left.

Fig. 3.

Network created using the ITS-2 nuclear marker. Line length is calculated from uncorrected p-distances and represents the genetic distance between sequences. Bootstrap values are indicated for each split (1000 replicates). Samples of D. variabilis and D. similis (n = 102 total (n = 37 study samples, n = 65 reference samples)) (based on mitochondrial markers) are clustered to the right, and D. andersoni (n = 31 total (n = 7 study samples, n = 24 reference samples)) to the left.

Dermacentor similis sequences that originated from samples that contained only a single tick and for which both sequence directions were generated have been uploaded to GenBank (Accession Numbers: PQ282516-PQ282520 (COI), PQ282513 (16S rDNA), PQ285801-PQ285805 (ITS-2)).

Pathogen Testing

Five hundred ninety-four submitted Dermacentor ticks were tested for R. rickettsii. Ticks that were morphologically identified to be D. albipictus were not tested. No ticks tested positive for the pathogen.

Spatial Description

Both D. andersoni and D. similis were submitted from southern British Columbia, with ticks predominately submitted from the Okanagan region and areas surrounding Kamloops (Fig. 4). In Alberta, D. andersoni were collected in southwestern Alberta near the British Columbia border. One D. variabilis was submitted from southwestern Alberta. Most D. variabilis samples submitted from Saskatchewan were from the eastern portion of the province. In summary, D. variabilis were found in Alberta eastwards, D. andersoni in British Columbia and Alberta, and D. similis in southern British Columbia (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

Dermacentor similis (triangles), D. variabilis (squares) and D. andersoni (circles) from companion animals were submitted from veterinary clinics in western Canada. Samples were confirmed to species using Sanger sequencing of COI and 16S rDNA mitochondrial markers. The map was created using QGIS software (Version 3.10.8, http://qgis.org).

Discussion

This study suggests that the distribution of Dermacentor species in Canada is different from what has historically been reported, particularly in British Columbia. Previously, only D. andersoni and D. albipictus were consistently documented in British Columbia (Wilkinson 1967, Lindquist et al. 2016). Historical samples of D. variabilis from the province, which were limited in number and distribution, were suspected to be due to travel (Lindquist et al. 2016). The majority of samples submitted in this study from British Columbia were identified as D. similis, with a subset as D. andersoni and D. albipictus (Duncan et al. 2020). Given that the 27 samples that had ITS-2 banding patterns consistent with D. variabilis from British Columbia and subsequently underwent further sequencing were confirmed to be D. similis, it is likely that most, if not all, of the 206 samples from British Columbia with banding patterns consistent with D. variabilis were D. similis. Further research is required to confirm the presence of established populations and the geographic range of D. similis. If available, the identity of historical samples of D. variabilis collected in British Columbia should be confirmed using morphological and molecular methods. Field sampling for ticks, including tick dragging and/or small mammal sampling, should be considered in areas from which D. similis was submitted to provide evidence of established D. similis populations and greater geographic precision.

The mechanisms facilitating potential northward range expansion of D. similis are currently unknown. Ticks can be introduced into new areas through the movement of hosts, particularly migratory birds or mammals with large or shifting home ranges (e.g., Ogden et al. 2008, Slabach et al. 2018). Further, the movement of humans and their companion animals through travel could facilitate tick movement (Buczek and Buczek 2021). In this context, migratory birds likely play a lesser role, as Dermacentor spp. do not commonly parasitize birds (Stafford et al. 1995, Lindquist et al. 2016). Adult Dermacentor spp. commonly parasitize larger land mammals and companion animals, so this mechanism is a more likely contributing factor (Bishopp and Trembley 1945, Lindquist et al. 2016). Host capture studies would be of benefit to further describe host associations throughout the geographic range of D. similis.

The mitochondrial molecular markers, 16S rDNA and COI genes, were most useful for identifying Dermacentor species, as demonstrated by three distinct groupings evident on the network analyses. Although nuclear markers have been used to differentiate D. variabilis and D. similis previously (Lado et al. 2021), the ITS-2 network generated in this study did not form distinct groupings for samples of suspected D. variabilis and D. similis. However, D. andersoni was still distinct from the other two species in the ITS-2 network. Additionally, the commonly used PCR and gel electrophoresis of the ITS-2 gene fragment is likely not sufficient to distinguish between D. variabilis and D. similis, as the gene fragments for D. variabilis and D. similis are likely similar in size (Dergousoff and Chilton 2007). Given there is a 72 base pair insertion for D. andersoni, PCR and gel electrophoresis is still valuable to differentiate D. andersoni from the other two species.

None of the samples tested in this study were positive for R. rickettsii, which aligns with past assessments that R. rickettsii exists at very low infection prevalences in Canadian tick populations (Dergousoff et al. 2009, Lindquist et al. 2016). Continued monitoring of pathogen prevalence in Dermacentor species, as well as testing for additional spotted fever group rickettsiae, is critical for ensuring that current reporting regarding the risk of pathogen transmission posed by ticks is up to date. Estimates of infection prevalence occasionally differ between active and passive surveillance studies, so continued monitoring for R. rickettsii should use both surveillance methods (Holcomb et al. 2023). Vector competence studies are needed to determine if there are differences between D. similis and both D. variabilis and D. andersoni (Lado et al. 2021).

Studies that rely on sample and data collection through passive surveillance have some limitations that should be considered. Given the location of acquisition was reported by the pet owners, the precise geographic sources may be uncertain. It can be challenging to determine the exact location from where a tick was acquired, as ticks can be on companion animals for some time before attaching or being discovered. Moreover, although travel history was requested in the questionnaire, it is possible that travel history was not reported. For example, there was one submission of D. variabilis from southwestern Alberta with no reported travel history; however, there is no current evidence of established populations of D. variabilis in this area. One submission is not sufficient to provide evidence of the establishment of this species. In addition to the possibility of unreported travel history, this finding may represent an adventitious tick. Active sampling should be used to determine the presence of a particular tick species in areas where passive sampling suggests ticks have been acquired (Eisen and Paddock 2021, Holcomb et al. 2023). Furthermore, given that samples were collected from hosts, some ticks were heavily engorged, which may impact pathogen detection (Krupa et al. 2024).

Other study limitations relate to the molecular methods. The ITS-2 primers generate a partial sequence by amplifying a short region which includes an insertion in the sequence for D. andersoni relative to the other three Dermacentor species in Canada. This study illustrated that this approach was not sufficient to differentiate D. similis and D.variabilis and thus any samples with banding patterns consistent with D. variabilis without any further analysis need to be interpreted with caution. To provide further evidence for species classification, 16S rDNA and COI sequences were also examined for a subset of samples. Some of the ticks were subjected to DNA sequencing in pools (up to five ticks), which can reduce the chances of detecting multiple species. This risk was mitigated by examining the ticks morphologically. Further, there was no evidence of ambiguous positions within the sequences, and pooled samples grouped well with sequences derived from single tick samples. However, the possibility of only the predominate species in a pooled sample being amplified during sequencing cannot be discounted. Finally, there were samples included in this analysis for which sequences were only generated in one direction. Although this is not ideal, this decision was made to maintain the sample size. Sequences were still trimmed to remove ambiguous sections to reduce erroneous results.

Conclusion

Through this study, it was demonstrated that the range of D. similis extends into Canada, specifically southern British Columbia, and that D. variabilis remains present in Saskatchewan. The infection prevalence of R. rickettsii in Dermacentor ticks is likely still very low in Canada. Sequencing of mitochondrial markers, such as 16S rDNA and COI, provides better utility in differentiating between species than the nuclear marker ITS-2. Field sampling is needed to expand on the findings of this study by investigating D. similis presence in the environment, and subsequently exploring habitat, host, and climatic factors associated with its presence.

Acknowledgments

We would like to sincerely thank the participating veterinary clinics and pet owners who submitted ticks. Thank you to Stefan Iwasawa and Roman McKay for providing reference tick samples.

Contributor Information

Grace K Nichol, Department of Population Medicine, Ontario Veterinary College, University of Guelph, Guelph, ON, Canada.

Paula Lado, Center for Vector-Borne Infectious Diseases, Colorado State University, Fort Collins, CO, USA.

Louwrens P Snyman, Royal Alberta Museum, Edmonton, AB, Canada; Department of Veterinary Microbiology, University of Saskatchewan, Saskatoon, SK, Canada.

Shaun J Dergousoff, Lethbridge Research and Development Centre, Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada, Lethbridge, AB, Canada.

J Scott Weese, Department of Pathobiology, Ontario Veterinary College, University of Guelph, Guelph, ON, Canada.

Amy L Greer, Department of Population Medicine, Ontario Veterinary College, University of Guelph, Guelph, ON, Canada; Department of Biology, Trent University, Peterborough, ON, Canada.

Katie M Clow, Department of Population Medicine, Ontario Veterinary College, University of Guelph, Guelph, ON, Canada.

Author contributions

Grace Nichol (Conceptualization [Lead], Data curation [Lead], Formal analysis [Lead], Investigation [Lead], Methodology [Lead], Project administration [Lead], Software [Lead], Supervision [Lead], Validation [Lead], Visualization [Lead], Writing—original draft [Lead], Writing—review & editing [Lead]), Paula Lado (Resources [Equal], Writing—review & editing [Equal]), Louwrens Snyman (Software [Equal], Visualization [Equal], Writing—review & editing [Equal]), Shaun Dergousoff (Conceptualization [Equal], Validation [Equal], Writing—review & editing [Equal]), Scott Weese (Conceptualization [Equal], Funding acquisition [Equal], Resources [Equal], Writing—review & editing [Equal]), Amy Greer (Conceptualization [Equal], Funding acquisition [Equal], Writing—review & editing [Equal]), and Katie Clow (Conceptualization [Equal], Funding acquisition [Equal], Investigation [Equal], Methodology [Equal], Project administration [Equal], Resources [Equal], Supervision [Equal], Writing—review & editing [Equal]).

Funding

This project was funded by the Ontario Veterinary College Pet Trust and the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada via the One Health Modelling Network for Emerging Infections. G. K. Nichol has received stipend support from the Ontario Veterinary College and the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada.

References

- Bishopp FC, Trembley HL.. 1945. Distribution and hosts of certain North American ticks. J. Parasitol. 31(1):1–54. https://doi.org/ 10.2307/3273061 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Buczek A, Buczek W.. 2021. Importation of ticks on companion animals and the risk of spread of tick-borne diseases to non-endemic regions in Europe. Animals 11(1):6. https://doi.org/ 10.3390/ani11010006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burgdorfer W. 1975. A review of Rocky Mountain spotted fever (tick-borne typhus), its agent, and its tick vectors in the United States. J. Med. Entomol. 12(3):269–278. https://doi.org/ 10.1093/jmedent/12.3.269 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooley RA. 1938. The genera Dermacentor and Otocentor (Ixodidae) in the United States, with studies in variation. US Natl. Inst. Health Bull. 171:1–89. [Google Scholar]

- Dergousoff SJ, Chilton NB.. 2007. Differentiation of three species of ixodid tick, Dermacentor andersoni, D. variabilis and D. albipictus, by PCR-based approaches using markers in ribosomal DNA. Mol. Cell. Probes 21(5-6):343–348. https://doi.org/ 10.1016/j.mcp.2007.04.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dergousoff SJ, Gajadhar AJA, Chilton NB.. 2009. Prevalence of Rickettsia species in Canadian populations of Dermacentor andersoni and D. variabilis. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 75(6):1786–1789. https://doi.org/ 10.1128/AEM.02554-08 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dergousoff SJ, Galloway TD, Robbin LL, et al. 2013. Range expansion of Dermacentor variabilis and Dermacentor andersoni (Acari: Ixodidae) near their northern distributional limits. J. Med. Entomol. 50(3):510–520. https://doi.org/ 10.1603/ME12193 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dergousoff SJ, Lysyk TJ, Kutz SJ, et al. 2016. Human-assisted dispersal results in the northernmost Canadian record of the American dog tick, Dermacentor variabilis (Ixodida: Ixodidae). Entomol. News 126(2):132–137. https://doi.org/ 10.3157/021.126.0209 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- DeWinter S, Bauman C, Peregrine A, et al. 2023. Assessing the spatial and temporal patterns and risk factors for acquisition of Ixodes spp. by companion animals across Canada. Ticks Tick Borne Dis. 14(2):102089–102089. https://doi.org/ 10.1016/j.ttbdis.2022.102089 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duncan KT, Clow KM, Sundstrom KD, et al. 2020. Recent reports of winter tick, Dermacentor albipictus, from dogs and cats in North America. Vet. Parasitol. Reg. Stud. Reports 22:100490. https://doi.org/ 10.1016/j.vprsr.2020.100490 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duncan KT, Saleh MN, Sundstrom KD, et al. 2021. Dermacentor variabilis is the predominant Dermacentor spp. (Acari: Ixodidae) feeding on dogs and cats throughout the United States. J. Med. Entomol. 58(3):1241–1247. https://doi.org/ 10.1093/jme/tjab007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisen RJ, Paddock CD.. 2021. Tick and tickborne pathogen surveillance as a public health tool in the United States. J. Med. Entomol. 58(4):1490–1502. https://doi.org/ 10.1093/jme/tjaa087 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Folmer O, Black M, Hoeh W, et al. 1994. DNA primers for amplification of mitochondrial cytochrome c oxidase subunit I from diverse metazoan invertebrates. Mol. Mar. Biol. Biotechnol. 3(5):294–299. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gregson JD. 1956. The Ixodoidea of Canada. Ottawa (ON, Canada): Science Service, Entomology Division, Canada Department of Agriculture; p. 1–92. https://doi.org/ 10.5962/bhl.title.58947 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Guillot C, Badcock J, Clow K, et al. 2020. Sentinel surveillance of Lyme disease risk in Canada, 2019: results from the first year of the Canadian Lyme Sentinel Network (CaLSeN). Can. Commun. Dis. Rep. 46(10):354–361. https://doi.org/ 10.14745/ccdr.v46i10a08 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holcomb KM, Khalil N, Cozens DW, et al. 2023. Comparison of acarological risk metrics derived from active and passive surveillance and their concordance with tick-borne disease incidence. Ticks Tick Borne Dis. 14(6):102243. https://doi.org/ 10.1016/j.ttbdis.2023.102243 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huson DH, Bryant D.. 2006. Application of phylogenetic networks in evolutionary studies. Mol. Biol. Evol. 23(2):254–267. https://doi.org/ 10.1093/molbev/msj030 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kato CY, Chung IH, Robinson LK, et al. 2013. Assessment of real-time PCR assay for detection of Rickettsia spp. and Rickettsia rickettsii in banked clinical samples. J. Clin. Microbiol. 51(1):314–317. https://doi.org/ 10.1128/JCM.01723-12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaufman EL, Busch JD, Hepp CM, et al. 2018. Range-wide genetic analysis of Dermacentor variabilis and its Francisella-like endosymbionts demonstrates phylogeographic concordance between both taxa. Parasit. Vectors 11(1):306. https://doi.org/ 10.1186/s13071-018-2886-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krakowetz CN, Dergousoff SJ, Chilton NB.. 2010. Genetic variation in the mitochondrial 16S rRNA gene of the American dog tick, Dermacentor variabilis (Acari: Ixodidae). J. Vector Ecol. 35(1):163–173. https://doi.org/ 10.1111/j.1948-7134.2010.00043.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krupa E, Dziedziech A, Paul R, et al. 2024. Update on tick-borne pathogens detection methods within ticks. Curr. Res. Parasitol. Vector Borne Dis. 6:100199. https://doi.org/ 10.1016/j.crpvbd.2024.100199 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lado P, Cox C, Wideman K, et al. 2019. Population genetics of Dermacentor variabilis say 1821 (Ixodida: Ixodidae) in the United States inferred from ddRAD-seq SNP markers. Ann. Entomol. 112(5):433–442. https://doi.org/ 10.1093/aesa/saz025 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lado P, Glon MG, Klompen H.. 2021. Integrative taxonomy of Dermacentor variabilis (Ixodida: Ixodidae) with description of a new species, Dermacentor similis n. sp. J. Med. Entomol. 58(6):2216–2227. https://doi.org/ 10.1093/jme/tjab134 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindquist E, Galloway T, Artsob H, et al. 2016. A handbook to the ticks of Canada. Biological Survey of Canada. [Google Scholar]

- Nelder MP, Russell CB, Johnson S, et al. 2022. American dog ticks along their expanding range edge in Ontario, Canada. Sci. Rep. 12(1):11063. https://doi.org/ 10.1038/s41598-022-15009-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norris DE, Klompen JSH, Keirans JE, et al. 1996. Population genetics of Ixodes scapularis (Acari: Ixodidae) based on mitochondrial 16S and 12S genes. J. Med. Entomol. 33(1):78–89. https://doi.org/ 10.1093/jmedent/33.1.78 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norris DE, Klompen JSH, Black WC IV. 1999. Comparison of the mitochondrial 12S and 16S ribosomal DNA genes in resolving phylogenetic relationships among hard ticks (Acari: Ixodidae). Ann. Entomol. 92(1):117–129. https://doi.org/ 10.1093/aesa/92.1.117 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ogden NH, Lindsay LR, Hanincová K, et al. 2008. Role of migratory birds in introduction and range expansion of Ixodes scapularis ticks and of Borrelia burgdorferi and Anaplasma phagocytophilum in Canada. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 74(6):1780–1790. https://doi.org/ 10.1128/AEM.01982-07 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slabach BL, McKinney A, Cunningham J, et al. 2018. A survey of tick species in a recently reintroduced elk (Cervus canadensis) population in Southeastern Kentucky, USA, with potential implications for interstate translocation of zoonotic disease vectors. J. Wildl. Dis. 54(2):366–370. https://doi.org/ 10.7589/2017-06-135 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stafford KC III, Bladen VC, Magnarelli LA.. 1995. Ticks (Acari: Ixodidae) infesting wild birds (Aves) and white-footed mice in Lyme, CT. J. Med. Entomol. 32(4):453–466. https://doi.org/ 10.1093/jmedent/32.4.453 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tamura K, Stecher G, Kumar S.. 2021. MEGA11: molecular evolutionary genetics analysis version 11. Mol. Biol. Evol. 38(7):3022–3027. https://doi.org/ 10.1093/molbev/msab120 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Telford SR III, Goethert HK.. 2020. Ecology of Francisella tularensis. Annu. Rev. Entomol. 65(1):351–372. https://doi.org/ 10.1146/annurev-ento-011019-025134 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilkinson PR. 1967. The distribution of Dermacentor ticks in Canada in relation to bioclimatic zones. Can. J. Zool. 45(4):517–537. https://doi.org/ 10.1139/z67-066 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]