Abstract

The generation of an active [FeFe]-hydrogenase requires the synthesis of a complex metal center, the H-cluster, by three dedicated maturases: the radical S-adenosyl-l-methionine (SAM) enzymes HydE and HydG, and the GTPase HydF. A key step of [FeFe]-hydrogenase maturation is the synthesis of the dithiomethylamine (DTMA) bridging ligand, a process recently shown to involve the aminomethyl-lipoyl-H-protein from the glycine cleavage system, whose methylamine group originates from serine and ammonium. Here we use functional assays together with electron paramagnetic resonance and electron-nuclear double resonance spectroscopies to show that serine or aspartate together with their respective ammonia-lyase enzymes can provide the nitrogen for DTMA biosynthesis during in vitro [FeFe]-hydrogenase maturation. We also report bioinformatic analysis of the hyd operon, revealing a strong association with genes encoding ammonia-lyases, suggesting important biochemical and metabolic connections. Together, our results provide evidence that ammonia-lyases play an important role in [FeFe]-hydrogenase maturation by delivering the ammonium required for dithiomethylamine ligand synthesis.

Keywords: [FeFe]-hydrogenase, dithiomethylamine, ammonia lyase, ammonium, glycine cleavage system, hyd operon, HydF, GTPase

Hydrogenases are metalloenzymes that catalyze the reversible reduction of protons to H2 and are fundamental for microbial energy metabolism (1). [FeFe]-hydrogenases have attracted attention in the field of renewable energy research as a model catalyst for the production and use of hydrogen (2, 3, 4, 5). H2 formation is catalyzed in the [FeFe]-hydrogenase active site at a biologically unique hexanuclear iron cofactor, the ‘H-cluster,’ which consists of a four-cysteine ligated [4Fe-4S] cluster ([4Fe-4S]H) connected to an organometallic [2Fe] subcluster ([2Fe]H) via a cysteine residue. The iron atoms of the [2Fe]H are coordinated by carbonyl (CO) and cyanide (CN–) ligands, as well as a bridging dithiomethylamine (DTMA) ligand (Fig. 1), and in its oxidized form (denoted Hox; [4Fe-4S]II - [Fe]pI - [Fe]dII) gives an electron paramagnetic resonance (EPR) signal with g = [2.103, 2.044, 1.998] (6, 7, 8). Maturation of the [FeFe]-hydrogenase into an active enzyme requires the assembly of the H-cluster in a complex stepwise process that starts with the insertion of the [4Fe-4S]H cluster into the hydrogenase by housekeeping Fe-S cluster biogenesis machinery (9, 10, 11), followed by assembly and insertion of the [2Fe]H subcluster by three dedicated maturation enzymes: HydG, HydE and HydF (12, 13, 14, 15).

Figure 1.

[FeFe]-hydrogenase from Clostridium pasteurianum (3C8Y) and its active site H-cluster (inset). Atom color, identity: rust, iron; yellow, sulfur; blue, nitrogen; red, oxygen; gray, carbon.

In the first step of [FeFe]-hydrogenase maturation, the radical S-adenosyl-l-methionine (SAM) enzyme HydG lyses tyrosine at the radical SAM (RS) [4Fe-4S] cluster to produce a 4-oxidobenzyl radical and dehydroglycine (16). The dehydroglycine is subsequently cleaved into CO and CN– diatomic ligands which bind to the unique fifth “dangler’’ iron of an auxiliary [5Fe-4S] cluster on HydG, ultimately generating a [FeII(Cys)(CO)2(CN)]– synthon (17, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23). Recent work has shown that the synthon is delivered directly from HydG to the second RS enzyme HydE (24). It was shown that HydE binds a synthetic analog of this synthon (synB) and adenosylates it, similar to the adenosylation reaction HydE catalyzes with thiazolidine substrates (25, 26). The HydE-catalyzed synB adenosylation reaction was shown by EPR spectroscopy to result in the reduction of the [FeII(Cys)(CO)2(CN)]– to an FeI synthon species, and HydE was proposed to subsequently dimerize two FeI synthon units to form the dinuclear [(FeI)2(μ-SH)2(CN)2(CO)4]2– complex ([2Fe]E) (27). The [2Fe]E cluster was then proposed to be transferred to HydF, a multidomain [4Fe-4S] cluster-containing scaffold protein with GTPase activity, prior to the installation of the bridging DTMA ligand (28, 29, 30, 31, 32, 33, 34, 35, 36, 37, 38, 39, 40, 41, 42, 43). Support for this model was provided by recent work demonstrating that the use of a synthetic [Fe2(μ-SH)2(CN)2(CO)4]2– complex, the presumed product of HydE, allowed the maturation of the [FeFe]-hydrogenase in the absence of HydG and HydE (44).

Since the methodology for in vitro maturation of [FeFe]-hydrogenase was first developed in 2008 (45), there has been an absolute requirement for the presence of clarified Escherichia coli (E. coli) lysate, indicating that the lysate was providing one or more unidentified but essential components for maturation. The crucial lysate component was recently identified as the aminomethyl-lipoyl-H-protein (Hmet) of the glycine cleavage system (GCS, Fig. S1), a discovery that led to the development of a lysate-free defined maturation system involving serine hydroxymethyltransferase (SHMT) and the T-protein of GCS in place of the E. coli lysate (Fig. 2) (14). Using this defined system, matured [FeFe]-hydrogenase was produced and characterized by electron-nuclear double resonance (ENDOR) spectroscopy, revealing that serine and ammonium provide the carbon and nitrogen, respectively, of the DTMA ligand of the H-cluster. This result apparently contradicted a prior lysate-based maturation pointing to serine as the source of both the N and C atoms of DTMA but raised the question of whether serine ammonia-lyase in the E. coli lysate might liberate NH3 from serine in reactions containing lysate (14, 46). A fully-defined semisynthetic maturation of the [FeFe]-hydrogenase using the synthetic [(FeI)2(μ-SH)2(CN)2(CO)4]2– cluster to bypass HydE and HydG revealed that [FeFe]-hydrogenase maturation could be accomplished with only the HydF maturase and the GCS components (47). It was suggested that Hmet and the GCS interact with a HydF/[(FeI)2(μ-SH)2(CN)2(CO)4]2– complex to install the DTMA ligand during maturation (47).

Figure 2.

Schematic depiction of the current model for [FeFe]-hydrogenase (HydA) maturation by the maturases HydG, HydE, and HydF, as well as components of the GCS including H-protein, T-protein, and SHMT, which together convert the HydAΔEFGcontaining only the [4Fe-4S]Hcluster to the holo-[FeFe]-hydrogenase.

Here we address the biological origins of the bridgehead nitrogen of the DTMA ligand of the H-cluster during biosynthesis of the H-cluster. We show that in a fully defined maturation system for the [FeFe]-hydrogenase from Chlamydomonas reinhardtii (CrHydA), both serine and aspartate can serve as the source of the bridgehead N of DTMA when the corresponding enzymes serine ammonia-lyase and aspartate ammonia-lyase are included in the maturation assay. Further, analysis of the hyd operon reveals its close association with genes for ammonia-lyases, suggesting that in vivo [FeFe]-hydrogenase maturation is dependent on ammonia-lyases to provide the N atom for DTMA biosynthesis. These results yield important new insights into the biochemical interconnections between [FeFe]-hydrogenase maturation, one-carbon metabolism via the GCS, and nitrogen cycling and energy metabolism via the ammonia lyase enzymes.

Results

Origin of DTMA bridgehead N depends on the presence of lysate

[FeFe]-hydrogenase defined in vitro maturation reactions were carried out under anaerobic conditions in the presence of CrHydA, the Hyd maturases HydE, HydF, HydG, the GCS proteins H-protein and T-protein, and SHMT as the source of carbon to load methylene-THF on the T-protein. Small molecule components included SAM, tyrosine, cysteine, iron, PLP, serine, NH4+, GTP, MgCl2, DTT, and dithionite (see Methods and SI). The maturation reactions were carried out in the presence or in the absence of lysate, and with 15N-serine (which as noted below was also 13C labeled) or 15NH4Cl in place of the unlabeled component. The matured CrHydA was purified from the maturation mixture, oxidized by thionin to the Hox state, and analyzed by EPR (Fig. S2) and ENDOR (Fig. 3) spectroscopies to evaluate the incorporation of the isotopic label into the DTMA of the H-cluster as previously described (14).

Figure 3.

2K Q-band15N Mims ENDOR spectra centered at the15N Larmor frequency and taken at g = 2.01 of mature HydA. A, Maturation in the presence of 15NH4+ (lower two spectra) results in 15N incorporation into DTMA regardless of the presence of lysate, while 15N incorporation from 13C,15N-serine (top two spectra) occurs only in the presence of lysate, indicating a role for an enzyme in the lysate. The bottom spectrum in panel (A) is reproduced from reference (14). (∗) represents harmonics of the 13C ENDOR response (not shown) from 13C incorporated in the DTMA from the doubly labeled serine; (↓) represents Mims ‘holes’ (see Experimental Procedures). B, maturation in the presence of 15N-aspartate and AspA, or 15N-serine and SdaA, results in the incorporation of 15N into DTMA, as revealed by 15N ENDOR spectra.

CrHydA matured in the presence of 15NH4Cl shows a 15N ENDOR response from the labeled DTMA regardless of whether E. coli lysate was present during maturation (Fig. 3A, bottom), indicating that nitrogen from NH4+ is incorporated into DTMA in this defined system. The 1.6 MHz 15N coupling observed for the DTMA nitrogen is comparable to that reported previously (14). However, the results shown in Fig. 3A, bottom, reveal a decreased intensity of the 15N doublet in the 15N ENDOR spectra of CrHydA matured with 15NH4Cl in the presence of lysate, indicating that other sources of unlabeled nitrogen are diluting the labeled nitrogen pool during incorporation into DTMA. CrHydA maturation reactions carried out in the presence of 13C,15N-serine show 15N incorporation into DTMA of the H-cluster, as indicated by the 15N doublet with a 1.6 MHz coupling, only when lysate was added to the defined maturation (Fig. 3A, top); this suggests that 15N can be liberated from 15N-serine for incorporation into DTMA by enzymes found in the cell lysate. The 13C from 13C,15N-serine was previously shown to be incorporated into DTMA via 13C-ENDOR spectroscopy (14). Together, these results point to a potentially important role for E. coli ammonia-lyases in providing the nitrogen for DTMA biosynthesis during in vivo [FeFe]-hydrogenase maturation during heterologous expression with the Hyd maturases, or when E. coli lysate is added to in vitro maturation reactions.

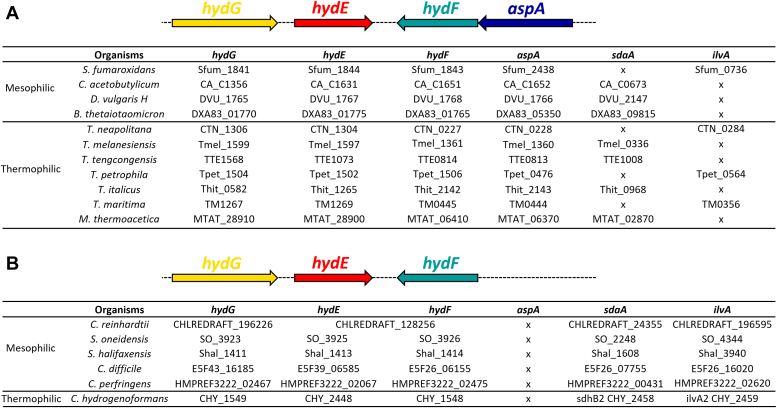

Hyd operon and amino acid ammonia-lyases

Analysis of the hyd operon from a range of mesophilic and thermophilic organisms reveals that it is closely associated with genes encoding amino acid ammonia-lyases (Fig. 4). Of particular note is the gene aspA, coding for aspartate ammonia-lyase (AspA), suggesting that this enzyme could be an important source of ammonia for in vivo DTMA synthesis (48). Organisms we identified as having the aspA gene associated with the hyd operon also invariably have a second ammonia-lyase gene, either sdaA encoding serine ammonia-lyase or ilvA encoding threonine ammonia-lyase, thus presumably providing an alternate source of ammonia for DTMA biosynthesis. Interestingly, some of the [FeFe]-hydrogenase-producing organisms we examined do not have the aspA gene associated with the hyd operon; these organisms are found to instead have both the sdaA and the ilvA genes, thus retaining two potential sources of nitrogen for DTMA biosynthesis in all cases (Fig. 4).

Figure 4.

Select [FeFe]-hydrogenase operons. A, organisms containing the aspA gene. B, organisms without the aspA gene. aspA: aspartate ammonia-lyase gene, sdaA: serine ammonia-lyase gene, ilvA: threonine ammonia-lyase gene. An ‘x’ in the table indicates the corresponding gene is not found.

Bioinformatic analysis of the hyd and amino acid ammonia-lyase genes

In order to analyze more broadly the relationships between the hyd genes and those for the amino acid ammonia-lyases illustrated in Fig. 4, we constructed sequence similarity networks (SSNs) and genomic context networks (GCNs) as described in the Experimental Procedures. The SSN and GCN for hydF (Fig. 5) and hydE (Fig. S3) reveal a significant correlation with ammonia lyase genes in the ± 20 open reading frame (ORF) genome neighborhood, as discussed below.

Figure 5.

Genomic context analysis for HydF. Top, sequence similarity network showing the HydF protein set. The proteins with at least one of the Pfam domains of interest are shown as teal “V’s” and those proteins that have at least one of the hyd gene Pfam domains, but no other Pfam domain of interest are shown as pale purple circles. Each cluster is named with the predominant annotations of proteins in that cluster. Figure created using Cytoscape and a perfuse force-directed layout algorithm. Bottom, a table showing the genes of interest and their associated Pfam domain, the number of nodes for which at least one of those Pfam domains was identified as a genomic neighbor within the ± 10 and ± 20 ORF of hydF, and the percentage of the total number of nodes represented.

A striking association with ammonia-lyase genes is evident from the bioinformatic analysis of hydF genes. For HydF, the number of proteins in the SSN that have at least one of the other hyd genes in the ± 20 ORF vicinity of hydF is 887 out of 1582 (roughly 56%); this is less than 100% since using BLAST to expand on the protein space will inevitably pull back pseudo-HydF proteins, proteins that look very similar to HydF but do not have the HydF function; we assume that the authentic hydF genes are the 887 with adjacent hyd maturase genes. The total number of nodes with at least one of the aspA, ilvA, or sdaA genes (as determined by the Pfam domain membership) is 701, or 79% of the authentic hydF genes, indicating a strong association that supports the hypothesis that these ammonia-lyases play an important role in providing the ammonia needed for DTMA biosynthesis during in vivo [FeFe]-hydrogenase maturation. It is interesting to note that aspA in particular is much more likely to be close to hydF, i.e. within ± 10 ORFs, than either ilvA or sdaA. The correlation of aspA, ilvA, or sdaA genes with hydE is lower (SI), consistent with HydF (and not HydE) being the enzyme involved in DTMA synthesis which requires ammonia as a source of N of DTMA.

Ammonia-lyases support [FeFe]-hydrogenase maturation in the absence of exogenous NH4+

Given the prominence of aspA near the hyd operon in most organisms that have an [FeFe]-hydrogenase, we tested the ability of aspartate ammonia-lyase to provide ammonium during HydA maturation. Aspartate ammonia-lyase is a divalent metal activated enzyme that at alkaline pH catalyzes the reversible reaction of aspartate cleavage into fumarate and ammonium (49, 50). E. coli AspA was overexpressed and purified (Figs. S4 and S5), and then included in a lysate-free maturation reaction containing 15N-aspartate; the matured HydA was analyzed by ENDOR spectroscopy after repurification from the reaction mixture (Fig. 3B). The results reveal a 15N doublet with hyperfine coupling of 1.6 MHz, consistent with the incorporation of 15N from 15N-aspartate into the DTMA of the H-cluster.

Serine ammonia-lyase (SdaA) is a [4Fe-4S] cluster-dependent enzyme present in E. coli lysate that catalyzes the liberation of NH4+ from serine (51). We and others have proposed that SdaA could be responsible for the observed incorporation of nitrogen from serine into DTMA in maturation reactions that include lysate (14, 46). To test this hypothesis, we purified and reconstituted E. coli SdaA (see SI Methods and Figs. S4, S6, and S7) and carried out a maturation reaction in which SdaA and 15N-serine were added to lysate-free maturation reactions that did not contain NH4Cl. ENDOR spectroscopy of the holo-CrHydA purified after maturation reveals the incorporation of 15N from serine into DTMA as evidenced by a 15N doublet with hyperfine coupling of 1.6 MHz, demonstrating that SdaA can provide the nitrogen from serine for use in DTMA biosynthesis (Fig. 3B).

Together, these results show that ammonia-lyases can liberate ammonium from multiple sources for use during HydA maturation, and provide a biochemical connection that reflects the proximity of ammonia-lyase genes to the hyd gene cluster. Further, our findings clarify why previous results have shown that for in vitro maturations that included E. coli lysate, serine is a source of the DTMA nitrogen: because serine ammonia lyase is a component of the lysate (46).

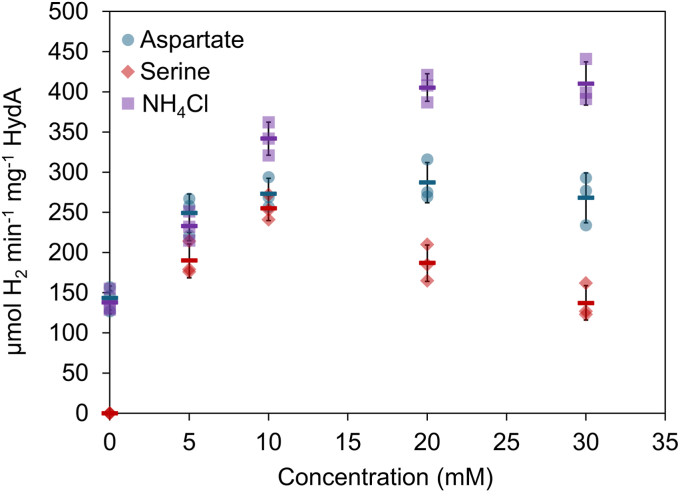

To further probe the involvement of ammonia-lyases as the source of ammonium during defined in vitro HydA maturation reactions, we examined the dependence of HydA maturation on serine and aspartate concentrations, in the presence of their respective ammonia-lyases. The results reveal a dependence of HydA maturation on the concentrations of aspartate and serine that is similar to the ammonium concentration dependence previously reported (Fig. 6). The maturation observed with 0 mM added nitrogen source in the case of the NH4+ (Fig. 6 – purple) and aspartate/AspA (Fig. 6 – blue) reactions could result from co-purification of NH4+ with T-protein, due to the well-defined NH4+ binding site in the T-protein (52). Alternatively, the decomposition of cysteine in the reaction mixture to produce pyruvate, sulfide, and ammonia is a known reaction in the presence of transition metals like iron (53, 54), and promoted in vitro by the addition of PLP (55). Because cysteine, iron, and PLP are all included in these defined in vitro HydA maturation reactions, there is likely always a background level of NH4+ available in solution for DTMA biosynthesis.

Figure 6.

Specific activities of HydA matured under defined conditions using the maturases HydE, HydF, and HydG in the presence of different sources of ammonium. The source of ammonium is indicated by the color (purple, ammonium chloride; blue, aspartate, and AspA; red, serine, and SdaA). Assays were conducted in triplicate; individual results are shown as transparent colored shapes with the mean as a colored line and the error bars are shown in black. Assay conditions are as described in the supplemental methods.

No maturation is detected at 0 mM serine for the SdaA reactions (Fig. 6 – red), which is consistent with the double role of serine as a source of the C (via SHMT and T-protein, Fig. 2) and N (via SdaA) of DTMA under these conditions. The presence of DTMA of 13C from the doubly-labeled serine has been previously reported (14), and is indicated here by the appearance of the 13C harmonic peaks in Fig. 3A. Neither the aspartate/AspA nor the serine/SdaA reactions achieve the same levels of maturation as the NH4+ reactions at concentrations above 10 mM; this likely in part reflects the limitations of the turnover rates of the ammonia-lyases under the conditions of the maturation reactions. In addition, the pyruvate product of serine turnover by SdaA inhibits [FeFe]-hydrogenase maturation in a concentration-dependent manner (Fig. S8), thus explaining the decreased [FeFe]-hydrogenase activity observed at higher concentrations of serine (Fig. 6, red).

Discussion

Our results clarify the source of the bridgehead N of DTMA, by showing that serine can serve as an indirect source of nitrogen via the production of ammonium when serine ammonia-lyase is provided by cell lysate or added in its purified form (46). We further showed that another ammonia-lyase, AspA, also can provide the bridgehead nitrogen of DTMA by releasing ammonium from aspartate. The relatively high degree of conservation of aspA in the hyd operon neighborhood (Figs. 4 and 5) supports an important role for AspA and aspartate as a source of ammonium during HydA maturation in vivo. Of note, organisms that have the aspA gene in the hyd operon also have either serine or threonine ammonia-lyase enzymes, presumably as a supporting ammonium source that may speak to metabolic fluxes during in vivo synthesis of the H-cluster (Fig. 4). Interestingly, many organisms that do not have the aspA gene in the hyd operon have both sdaA and ilvA genes, and could use the resulting ammonia-lyases (serine and threonine respectively) as sources of ammonium for the GCS. Serine ammonia-lyase is closely linked to the GCS and one-carbon metabolism, strongly suggesting that SdaA is a natural source of ammonium during in vivo [FeFe]-hydrogenase maturation (Fig. 7) (56).

Figure 7.

Role of ammonia-lyases in HydA maturation.

The relatively high degree of conservation of aspA in the hyd operon raises a question: why is it conserved over the other ammonia-lyases? Both SdaA and AspA can provide ammonia for the GCS and feed the TCA cycle via their by-products, pyruvate and fumarate respectively, but the fumarate produced by AspA can also be used as an electron acceptor for anaerobic respiration (Fig. 7). Given that most organisms producing the [FeFe]-hydrogenase are anaerobes, there would be an evolutionary advantage to AspA/aspartate over SdaA/serine as the source of nitrogen for DTMA biosynthesis. Consistent with this idea, organisms harboring the hyd operon but no aspA use other electron acceptors than fumarate: Shewanella oneidensis uses FeIII, MnIV, and UVI as terminal electron acceptors, and others use sulfate, sulfur, nitrate, or nitrite (57, 58, 59, 60, 61, 62, 63, 64). In addition, it is interesting to note that the aspA gene is almost always in the immediate proximity of the hydF gene (Figs. 4 and 5) that encodes for the HydF maturase implicated in DTMA synthesis (14, 44). Moreover, HydF was shown to belong to a subclass of GTPase enzymes whose activity is gated by monovalent cations; intriguingly, ammonia was shown to stimulate GTP hydrolysis by HydF (41), further supporting the connection between HydF and AspA.

The recognition of the interconnection between the HydA biosynthetic pathway and ammonia-lyases via the GCS confirms the key physiological roles played by the GCS as an important part of the one-carbon metabolic pathway in microorganisms (65, 66). Indeed, in addition to its central role in ammonium trafficking between the ammonia-lyases and HydA maturation pathway, the GCS is also coupled to SAM synthesis which is required for the catalytic activity of the maturases HydE and HydG: the GCS is coupled through its main intermediates tetrahydrofolate (THF) and methylene-THF to the tetrahydrofolate cycle and the methionine cycle. The methylene-THF can be further reduced to 5-CH3-THF, which is used in the methionine cycle to generate SAM (67).

In the GCS, the methylamine group of Hmet comes from glycine if the system turns towards glycine cleavage, or serine and ammonium if the system turns toward glycine synthesis (Fig. S1). During in vitro HydA maturation, the use of reducing agents such as DTT and NaDT prevents the system from operating in the direction of glycine cleavage via the P-protein, since the substrate of the latter enzyme is the oxidized form of the lipoyl-H-protein. The use of strong reducing agents during in vitro HydA maturation could be one of the contributing factors as to why serine and ammonia have been reported to be the source of the methylamine group of Hmet via SHMT and T-protein (14). Clearly, reducing conditions are required for the enzymatic activity of HydE and HydG, but the downstream redox flux is unclear for HydF, DTMA biosynthesis, and cluster translocation to HydA. This work begins to clarify some of these points. The presence of aspA in the hyd operon and its ability to support maturation reinforces the idea that Hmet produced in vivo from serine and ammonia via the glycine synthase reactions plays a key role in hydrogenase maturation. It is interesting to note that in some anaerobic bacteria like Clostridium acidiurici, Clostridium cylindrosporum, or Clostridium purinolyticum, the GCS runs mostly in the direction of glycine synthesis as invoked here during hydrogenase maturation (66, 68, 69, 70).

Taken together, our results show that ammonia-lyases are the major source of ammonia required for HydA maturation via the GCS and shed light on the central role played by the GCS in HydA maturation. The GCS is coupled to the tetrahydrofolate cycle and central carbon metabolism via the glycine-serine-interconversion and the ammonia-lyases to provide the methylene-THF and the ammonium required to synthesize the CNC backbone of DTMA of the H-cluster. The results herein reveal the physiological processes that are tied to [FeFe]-hydrogenase maturation, and further link fundamental metabolic pathways to the chemistry associated with DTMA biosynthesis. Our results connect the picture of HydA maturation to the metabolic pathways of [FeFe]-hydrogenase-containing organisms and significantly increase our understanding of bacterial metabolism during the HydA maturation process.

Experimental procedures

Expression, purification, and reconstitution of HisTag maturase enzymes

The expression, isolation, and reconstitution of His-tagged Clostridium acetobutylicum (C.a.), Thermotoga maritima (T.m.), and C. reinhardtii (C.r.) maturases followed previously published protocols: TmHydE (48), CaHydF (37), CaHydG (23) and CrHydA (14). Details are provided in the following paragraphs.

BL21(DE3)RIL cells were transformed with pET21b-T.m.hydE. Pre-cultures were started with a single colony selected from the transformation plate in LB media containing 50 μg/ml ampicillin and incubated at 37 °C with 180 rpm shaking overnight. The next day, 10 ml seed culture was used to inoculate 1.5 L phosphate-buffered TB media with 50 μg mL−1 ampicillin and incubated at 37 °C 200 rpm shaking. When OD600 was 0.5 to 0.7, overexpression was induced with 1 mM IPTG. At the time of induction, ∼0.15 mM ferric ammonium citrate was added into each culture flask and incubated at 37 °C 200 rpm shaking. After 30 min, 0.316 mM L-cysteine was added into each flask and kept incubating at 37 °C for 4 h. After that, a second aliquot of ferric ammonium citrate was added to make ∼0.3 mM final in each flask and incubated at 18 °C 200 rpm shaking overnight. The next day the culture was harvested via centrifugation, and the resulting cell pellet was frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80 °C until purification. Cells were lysed in 100 ml 50 mM Tris-HCl pH 8.0, 250 mM KCl buffer containing 8 mg lysozyme, ∼0.1 mg DNase, 200 mg MgCl2, 1000 mg Triton X-100, and two tablets of Pierce protease inhibitor tablets for 30 min, homogenized with 18G needle and syringe, at ambient temperature in a Coy chamber followed by centrifuging for 1 h at 4 °C. Clarified lysate was loaded to the Ni-NTA column and equilibrated with 50 mM Tris-HCl pH 8.0, 250 mM KCl, and 10 mM imidazole. Step gradient was applied with increasing imidazole concentration in buffer (50 mM, 150 mM, 225 mM, and 500 mM). The majority of the protein was eluted with 50 mM Tris-HCl pH 8.0, 250 mM KCl, and 150 mM imidazole. The elution fraction was desalted with a desalting column packed with G-25 resin and concentrated with Amicon 30 kDa MWCO spin filters. The final stock was frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80 °C until reconstitution. HydE was reconstituted by incubating the protein with FeCl3 and Na2S·9H2O in 50 mM Tris-HCl pH 8.0, 250 mM KCl, and 5 mM DTT buffer as previously described (48).

Overnight seed culture was started with BL21(DE3) cells transformed with pRSF-C.a.hydF construct in LB media containing 50 μg mL−1 kanamycin and incubated at 37 °C with shaking overnight. The next day, phosphate-buffered LB media (a total of 9 L distributed equally into 6 2.8 L Fernbach flasks) was supplemented with 5 g L−1 D-glucose and 50 μg mL−1 kanamycin. After inoculation from the seed culture, flasks were incubated at 37 °C with 230 rpm shaking. When OD600 was 0.9 to 1.2, culture flasks were placed into an ice-water bath for 30 min. After cold-shock, cells were induced with 1 mM IPTG, supplemented with ferrous ammonium sulfate, and incubated at 37 °C with 230 rpm shaking for 2.5 h. Then, a second aliquot of FAS was added into each culture flask (∼0.3 mM final FAS concentration in each flask) and sparged with nitrogen gas at 4 °C overnight. The next day cells were harvested by centrifugation at 6000 rpm, 4 °C, and the resulting pellet was frozen in liquid nitrogen. 45 g frozen cell paste was lysed in 90 ml of 50 mM HEPES pH 7.5, 300 mM KCl buffer with 8 mg lysozyme, ∼0.1 mg DNase, 900 mg Triton X-100, 1 mM PMSF, and 180 mg MgCl2. Lysate was incubated for ∼45 min and clarified by centrifuging. Clarified lysate supernatant was loaded to the Ni-NTA column and a step gradient was applied with increasing imidazole concentration in 50 mM HEPES pH 7.5, 300 mM KCl buffer (25 mM, 50 mM, 100 mM, and 225 mM). The target protein was eluted with 50 mM HEPES pH 7.5, 300 mM KCl, 225 mM imidazole, and desalted with a desalting column packed with G-25 resin and concentrated with an Amicon 30 kDa MWCO spin filter. The final desalted protein stock was frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80 °C until reconstitution. HydF was reconstituted by following the previously published protocol (34) by incubating with FeCl3 and Na2S·9H2O in 50 mM HEPES pH 7.5, 300 mM KCl, and 5 mM DTT buffer. The final reconstituted and desalted protein stock was concentrated and stored at −80 °C until further use.

Rosetta(DE3)pLysS cells containing pCDF-C.a.hydG construct were used to start a pre-culture in LB media containing 25 μg mL−1 chloramphenicol and 100 μg mL−1 streptomycin. The culture was incubated at 37 °C with shaking overnight. The next day, after diluting the seed culture in a total of 6 L phosphate buffered TB media with antibiotics, culture flasks were incubated at 37 °C with 180 rpm shaking. Cells were induced with 1 mM IPTG at OD600 0.8 to 1.0 and supplemented with ferrous ammonium sulfate and L-cysteine and incubated at 25 °C with 180 rpm shaking overnight. After harvesting cells by centrifugation, wet cell paste was frozen in liquid nitrogen. 40 g frozen cell pellet was lysed in 80 ml of 50 mM Tris-HCl pH 8.0, 250 mM KCl, 5% glycerol containing 10 to 16 mg lysozyme, ∼0.1 mg DNase, 1 mM PMSF, 92 mg MgCl2, 800 mg Triton X-100. Lysate was clarified by centrifugation as described above for the other proteins and the clarified lysate supernatant was loaded to the Ni-NTA column. A step gradient was applied by increasing the concentration of imidazole in the buffer. Fractions from 100 to 150 mM imidazole wash were pooled and desalted via a desalting column packed with G-25 resin. Desalted protein was concentrated via Amicon 50 kDa MWCO spin filters and frozen in liquid nitrogen, stored at −80 °C until reconstitution. HydG was reconstituted as described previously (23) incubating with FeCl3 and Na2S·9H2O in 50 mM Tris-HCl pH 8.0, 250 mM KCl, 5% glycerol, 5 mM DTT buffer. Reconstituted protein stock was desalted, concentrated with spin filters, and stored at −80 °C until use.

Expression, purification, and reconstitution of StrepTag CrHydA

The preparation of truncated CrHydA (residues 2–56 removed) with a C-terminal StrepTag was performed as described previously (71) with minor modifications (14) as follows. Chemically competent E. coli BL21(DE3) cells were transformed with pETDuet-1-C.r.hydA1 construct and used to start pre-cultures in LB media with 50 μg mL−1 carbenicillin. The culture was incubated at 37 °C with shaking overnight. The next day, 50 ml from pre-culture was inoculated into four Fernbach flasks containing phosphate-buffered 1.5 L TB media (a total of 6 L) supplemented 50 μg mL−1 carbenicillin. Culture flasks were incubated at 37 °C with 180 rpm shaking. When OD600 reached ∼1.1, sterile-filtered IPTG (1 mM final) and ferrous ammonium sulfate (0.5 mM final) were added into each flask and incubated at 37 °C. After 1 h of incubation 0.5 mM L-cysteine was added and kept incubating for 2 h more. After a total of 3 h at 37 °C, the temperature was decreased to 18 °C for overnight incubation with 180 rpm shaking. Cells were pelleted by centrifugation at 7000 rpm at 4 °C. The resulting wet cell paste was frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80 °C. Cells were lysed in 80 ml of 50 mM HEPES pH 8.0, 150 mM KCl buffer containing 8 mg Lysozyme, ∼0.1 mg DNase, 800 mg Triton X-100, 160 mg MgCl2, 1 mM PMSF and incubated at ambient temperature for 30 min with continuous stirring. Lysate was clarified by centrifuging at 18,000 rpm for 1 h. Clarified lysate was loaded to 10 ml StrepTactin-XT column equilibrated with 50 mM HEPES pH 8.0, 150 mM KCl buffer. After all the lysate was loaded, the column was washed with the equilibration buffer and the protein was eluted with 50 mM HEPES pH 8.0, 150 mM KCl, 50 mM D-biotin. Eluent was concentrated with Amicon 30 kDa MWCO spin filters and desalted via PD-10 column to remove biotin. After desalting, protein stock was concentrated with spin filters, frozen in liquid nitrogen, and stored at −80 °C. HydA was reconstituted by following a previously published protocol (23) using FeCl3 as the iron source and Na2S·9H2O as the sulfur source in 50 mM HEPES pH 8.0, 150 mM KCl, and 5 mM DTT. The final protein stock was desalted via a desalting column concentrated with spin filters and stored at −80 °C.

Expression and purification of HisTag E. coli aminomethyltransferase (T-protein)

The preparation of T-protein with a C-terminal HisTag was performed as described previously (14). Chemically competent E. coli cells were transformed with pET23a plasmid containing the E. coli T-protein gene. 45 ml seed culture was diluted in Fernbach flasks containing 1.5 L of phosphate-buffered TB media with 100 μg mL−1 ampicillin (total culture was 6 L). Culture flasks was incubated at 37 °C with 180 rpm shaking. When the optical cell density, OD600, reached 1.1 to 1.9, cells were induced with 1 mM IPTG and incubated at 16 °C overnight with 200 rpm shaking. The next day cells were harvested, frozen in liquid nitrogen, and stored at −80 °C until lysis and purification. 50 g of cell paste was lysed in 100 ml of 50 mM HEPES pH 7.5, 250 mM KCl (Buffer A) containing 8 mg lysozyme, 1000 mg Triton X-100, 1 mM PMSF, 200 mg MgCl2 and 0.1 mg DNase. Lysate was incubated at ambient temperature for ∼1 h and clarified by centrifuging at 17,000 rpm for 1 h. Clarified lysate was loaded to a 20 ml Ni-NTA column equilibrated with 50 mM HEPES pH 7.5, 250 mM KCl, and 10 mM imidazole. A step gradient was applied for the purification of his-tagged T-protein by increasing the concentration of imidazole in Buffer A: 10 mM, 50 mM, 100 mM, and 500 mM imidazole. Elution fractions from 50 mM and 100 mM imidazole were combined, concentrated with Amicon Ultra-15 spin filters, and desalted via HiPrep 26/10 column equilibrated with Buffer A. Desalted protein was aliquoted, frozen with liquid nitrogen, and stored at −80 °C. H-protein co-purifies with the T-protein and thus H-protein is not added separately to the maturation reactions (14).

Expression and purification of HisTag E. coli serine hydroxymethyltransferase (SHMT)

The preparation of SHMT with an N-terminal HisTag was performed as described previously (14). Chemically competent BL21(DE3) cells were transformed with pET14b containing E. coli SHMT gene. After inoculation from seed culture to Fernbach flasks containing 1.5 L phosphate buffered TB media supplemented with 50 μg mL−1 ampicillin, culture flasks were incubated at 37 °C with 180 rpm shaking. Once the cell density, OD600, reached ∼1.0, cells were induced with 1 mM IPTG and incubated at 18 °C overnight with 180 rpm shaking. The lysis and purification followed the method described above with the following minor changes. Clarified lysate was loaded to a 20 ml Ni-NTA column equilibrated with 50 mM HEPES pH 7.5, and 250 mM KCl. A step gradient was applied by increasing the imidazole concentration in Buffer A (10 mM, 50 mM, 150 mM, and 500 mM). The target protein was eluted with Buffer A containing 150 mM imidazole. The yellow elution fraction was desalted with a G-25 resin-packed column and concentrated with Amicon spin filters. The final protein stock was aliquoted, frozen with liquid nitrogen, and stored at −80 °C.

Expression, purification, and reconstitution of E. coli serine deaminase (SdaA)

Pre-cultures of BL21(DE3) cells containing the sdaA gene in pET28a plasmid were started in LB media supplemented with 50 μg mL−1 kanamycin and incubated at 37 °C in a shaker incubator overnight. The next day, 40 ml from the pre-culture was inoculated into each 1.5 L TB media with phosphate buffer containing 2.8 L Fernbach flasks supplemented with 50 μg mL−1 kanamycin (total 4.5 L culture) and cultures were incubated at 37 °C with 250 rpm shaking. When the cell density reached OD600 ∼1.0 to 1.1, culture flasks were placed in an ice-water bath for 45 min, then induced with 1 mM IPTG. At the point of induction, ferrous ammonium sulfate was also added into each flask (212 μM final concentration in each). Cultures were incubated at 16 °C with 200 rpm shaking overnight. Cells were harvested by centrifuging at 4 °C for 10 min. The wet cell pellet was flash-frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80 °C until purification. Cell lysis and isolation of HisTag SdaA took place in a Coy anaerobic chamber. 45 g of frozen cell paste was lysed in 90 ml of lysis buffer: 50 mM HEPES pH 7.5, 100 mM KCl containing 8 mg lysozyme, ∼0.1 mg DNase, 1000 mg Triton X-100, 200 mg MgCl2 and two EDTA-free Pierce protease inhibitor tablets. After 30 min incubation at ambient temperature with continuous stirring, cell lysate was clarified by centrifuging at 17,000 rpm, 4 °C for 1 h. The resulting lysate supernatant was loaded to 20 ml HisPrep FF 16/10 (Cytiva) column equilibrated with 50 mM HEPES pH 7.5, 100 mM KCl, 10 mM imidazole via ÄKTA Start system. A step gradient was applied with increasing concentrations of imidazole (25 mM, 50 mM, 100 mM, 225 mM, and 500 mM) in the buffer. The resulting dark brown elution fraction was desalted through a desalting column packed with Sephadex G-25 resin to remove imidazole, and concentrated with Amicon Ultra-15 centrifugal filter (30 kDa MWCO). The iron content of the desalted and concentrated SdaA stock was determined to be 1.75 ± 0.04 Fe/SdaA monomer via atomic absorption (AA) spectroscopy. As-purified SdaA was chemically reconstituted in 50 mM HEPES pH 7.5, 100 mM KCl buffer supplemented with 0.6 mM ferric chloride (FeCl3), 0.6 mM sodium sulfide nonahydrate (Na2S·9H2O) and 5 mM dithiothreitol (DTT). The reconstitution mixture was incubated on a gel ice pack until the broad absorption peak of [4Fe-4S] at ∼410 nm stabilized (∼2.5 h). Then, the mixture was centrifuged at 13,000 rpm for 10 min and desalted through a desalting column packed with Sephadex G-25 resin to remove excess iron, sulfur, and Fe-S cluster polymers. The resulting stock of SdaA was concentrated with Amicon Ultra-15 Centrifugal Filter (30 kDa MWCO) and the iron content of the protein stock was analyzed with AA spectroscopy. Aliquoted protein stocks were flash-frozen with liquid nitrogen and stored at −80 °C.

Serine deaminase (SdaA)-coupled enzyme activity assay

A previously published protocol was followed with some modifications (51). SdaA catalyzes the cleavage of the Cβ¯NH2 bond of serine to yield pyruvate and ammonium. To determine the activity of SdaA, the deamination reaction was coupled to the NADH-dependent reaction of lactate dehydrogenase (LDH, EC 1.1.1.27) which reduces pyruvate to lactate. L-serine, NADH, and lyophilized LDH were dissolved in 20 mM Tris-HCl pH 8.0 to prepare stock solutions. The final concentration of the reaction components is as follows: 5 mM L-serine, 0.3 mM NADH, 1 U LDH, and 7 nM SdaA in total 1 ml. L-serine, NADH, and LDH were premixed and transferred into a septum-sealed quartz cuvette in the glovebox. Then, the pre-mix was taken outside of the glovebox and placed into a Cary 60 UV-vis spectrometer equipped with RTE-5 refrigerated circulating bath set to 37 °C to equilibrate the pre-mix temperature prior to initiating the reaction by adding SdaA. 10 μl of SdaA was measured in the glovebox and transferred outside the glovebox in a gastight Hamilton syringe. The needle of the syringe was stabbed into an empty crimp vial sealed inside the glovebox. The reaction started by adding 10 μl of SdaA into the 37 °C premix through the septa and mixed quickly. UV-vis scans were recorded, and the reaction was monitored focusing on the decrease in the NADH absorption at 340 nm (ε340nm = 6022 M−1 cm−1). The time-dependent decrease in the absorption of NADH indicates that SdaA cleaves serine and produces pyruvate, then LDH reduces pyruvate leading to oxidation of NADH to NAD+. Absorbance at each time point was used to calculate the amount of NADH remaining (μM) and plotted against time (min). The slope of the linear region was used as the rate of NADH consumption by LDH as a proxy to serine deamination by SdaA. The activity of SdaA towards the deamination of serine was found to be 130 μM serine min−1 which corresponds to a kcat value of 303 s−1.

E. coli aspartate ammonia-lyase (AspA) preparation

The E. coli aspA gene was purchased from Genscript. The DNA sequence was codon-optimized for expression in E. coli and was cloned into a pET-23a vector between the NheI and EcoRI restriction sites, allowing for expression of aspartate ammonia lyase with a C-terminal His6 tag in E. coli BL21(DE3) cells. The corresponding DNA sequence is provided in the Supporting Information.

Pre-cultures were started in 60 ml Luria-Bertani (LB) media supplemented with 100 μg mL−1 ampicillin and incubated at 37 °C overnight. The next day, 40 ml pre-culture was inoculated into each 1.5 L (total 4.5 L) potassium phosphate buffered Terrific-Broth media with 100 μg mL−1 ampicillin and incubated at 37 °C with 250 rpm shaking. When cell density reached OD600 ∼1.2 to 1.3, culture flasks were put into an ice-water bath for 45 min. After cold shock, cells were induced with 1 mM isopropyl ß-D-1-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG) and incubated at 16 °C with 200 rpm shaking overnight. Cells were centrifuged at 4 °C for 10 min. The wet cell pellet was flash-frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80 °C until further use.

To isolate his-tagged AspA, all lysis and purification steps were performed in a Coy anaerobic chamber. Lysis was performed at a ratio of 2 ml lysis buffer per 1 g of cell paste and ambient temperature in 50 mM Tris-HCl pH 7.5, and 100 mM KCl containing the same lysis buffer components outlined above for SdaA. After incubation cell lysate was clarified by centrifuging at 17,000 rpm for 1 h. Clarified lysate was loaded to the Ni-NTA column and equilibrated with 50 mM Tris-HCl pH 7.5, 100 mM KCl, and 10 mM imidazole buffer. Imidazole concentration is increased following a step gradient from 25 mM, 50 mM, 150 mM, 225 mM, and 500 mM. Fraction collected from the elution with 50 mM Tris-HCl pH 7.5, 100 mM KCl at 150 mM imidazole was loaded onto a HiPrep 26/10 desalting column to remove imidazole. Desalted AspA was concentrated with Amicon Ultra-15 centrifugal filter (30 kDa MWCO). The resulting protein was aliquoted and flash-frozen with liquid nitrogen and stored at −80 °C until further use.

Aspartate ammonia-lyase (AspA) coupled activity assay

Aspartate ammonia-lyase catalyzes the deamination of aspartate to ammonia and fumarate. The ammonia production of AspA from L-aspartate was coupled to the NADH-dependent reductive amination of α-ketoglutarate by glutamate dehydrogenase (GDH from beef liver, EC 1.4.1.3). The reaction took place outside of the glovebox at ambient temperature (∼25 °C) in 1 M Tris-HCl pH 8.0 buffer. L-aspartate, α-ketoglutarate, NADH, ADP, and GDH were dissolved in a buffer. The reaction contained 10 mM L-aspartate, 5 mM MgCl2, 10 mM α-ketoglutarate, 0.3 mM NADH, 0.5 mM ADP, 10 U GDH, and 50 nM monomeric AspA. The reaction was initiated with the addition of AspA and the decrease in 340 nm absorption signal of NADH (ε340nm = 6.22 mM−1 cm−1) was monitored. The concentration of NADH at each time point was determined and plotted against time. The rate of the NADH oxidation was calculated as 68 μM NADH min−1, which corresponds to a kcat value of 22.6 s−1.

SAM Synthesis

Preparation of enzymatically synthesized SAM was performed as described previously (72, 73, 74).

In vitro [FeFe]-Hydrogenase maturation reactions

The in vitro maturation reactions were adapted from previously reported procedures (14) as follows. In vitro maturation of CrHydA was carried out at an ambient temperature in an anaerobic MBraun chamber (O2 ≤ 1 ppm). Standard assays contained HydA (4 μM), HydE (5 μM), HydF (5 μM), HydG (25 μM), Fe(II) (6.4 mM), l-cysteine (2 mM), l-tyrosine (2 mM), l-serine (50 mM), NH4Cl (up to 50 mM), SAM (2.5 mM), GTP (20 mM), MgCl2 (20 mM), dithionite (2 mM), PLP (1 mM), DTT (1 mM), T-protein (10 μM), and SHMT (5 μM). For assays involving the amino acid ammonia lyases, NH4Cl was omitted and either AspA and aspartate or SdaA and serine was added, as detailed below. Pyruvate was added at the concentrations indicated for the experiments shown in Fig. S8. Assay components were incubated together (200 μl final volume) for 12 h in a 100 mM HEPES, pH 8.2, 50 mM KCl buffer, prior to removing an aliquot to assay for active hydrogenase.

When in vitro maturation of CrHydA was carried out with AspA, the pH of the stock solution of aspartate (50 mM final concentration) was adjusted to 8 with a solution of KOH and added slowly over 2 h to AspA (23 nM final concentration) before adding the components of HydA maturation (to 20 mM final concentration of aspartate). When in vitro maturation of CrHydA was carried out with SdaA, the latter enzyme (17 nM final concentration) was incubated with 2 mM serine for 2 h before adding the components of HydA maturation along with 20 mM serine.

[FeFe]-hydrogenase activity assays

The [FeFe]-hydrogenase activity assays were carried out in 2 ml reaction mixtures containing 2 μl of the maturation reaction mixture and freshly prepared 20 mM DT and 10 mM methyl viologen in buffer containing 50 mM Tris and 10 mM KCl pH 6.9. After 3 min, headspace gas (100 μl) was removed from the sealed crimp vial with a Hamilton gas-tight syringe. H2 production was quantified using a SHIMADZU GC-2014 equipped with a TCD detector using N2 as a carrier gas.

Re-purification of holo-CrHydA from in vitro maturation experiments

The repurification of strep-tagged holo-CrHydA was carried out anaerobically and followed a previously published protocol (14).

EPR and ENDOR sample preparation

Q-band EPR and ENDOR samples were prepared with freshly purified holo-HydA in an MBraun glovebox with 100% N2 atmosphere. Matured holo-HydA was mixed with 2 mM thionin acetate from a freshly prepared stock solution, then transferred into an EPR tube, capped with a rubber septum, and then immediately transferred from the chamber and flash frozen in liquid N2 within ≤1.5 min. Samples were stored in liquid N2 until spectral acquisition occurred.

EPR and ENDOR spectroscopy

35 GHz pulse EPR/ENDOR spectra were collected on a spectrometer described previously (75, 76) that is equipped with a helium immersion dewar for measurement at 2K. For a single molecular orientation and for the 15N nuclear spin with I = half, the ENDOR transitions for the ms = ±half electron manifolds are observed, to first order, at frequencies, where νn is the nuclear Larmor frequency, and A is the orientation-dependent hyperfine coupling (Equation 1). In the Mims experiment, the ENDOR intensities are modulated by an inherent response factor (R), R ∼ [1 - cos(2πAτ)] where τ is the interval between the first and second pulses in the three-pulse Mims spin-echo sequence. When Aτ = n (n = 0, 1, 2…), the ENDOR response is at a minimum, resulting in hyperfine “suppression holes’’ in the Mims spectra. In Figure 3 these holes are indicated by (↓).

| (1) |

Generation of sequence similarity networks

Each of the HydE proteins from the organisms of interest was run through BLAST using the EBI’s UniProt (77) BLAST webservice (default settings, with an E-Threshold of 0.00001, the maximum number of results 250, and against the full UniProtKB, Release 2024_03. For each BLAST run, the proteins were further filtered to remove any hits below 1e-50 to minimize the chance of pulling in related proteins that are not HydE, as BioB, PylB, and HmdB are all functions that belong to the same subgroup within the radical SAM superfamily (48). This took us to an input list of 1524 proteins.

The list of proteins was combined and made unique, then uploaded to the EFI sequence similarity network tool (78, 79) (https://efi.igb.illinois.edu/efi-est/) using the Accession IDs tab. The SSN threshold was chosen as 1e-95 to minimize the number of edges whilst retaining the maximum connectivity information, and identical proteins (100% sequence identity) were also filtered out, resulting in 1349 nodes and 215,924 edges.

The hydF (1465 nodes and 798,235 edges at 1e-95) network was generated in the same manner.

Building the genomic context networks

Once the SSN had been generated, it was fed into the EFI’s Genome Neighbourhood Tool (https://efi.igb.illinois.edu/efi-gnt/) (78, 79) using the SSN generated in step 1 as the input. The neighborhood size (number of ORFs) was chosen to be ± 10 or ± 20 and includes RNAs in the placement count, although RNA components are discarded from any further analysis by the tool. The versions of underlying databases used in this analysis as part of the EFI’s toolkit is UniProt 2024_01, and the ENA version downloaded in January 2024.

The original SSN was then annotated with the results of the GCN and analyzed using Cytoscape (80).

Each of the genes of interest was examined for conserved Pfam domains (see Fig. 5) and these domains were searched for in the SSN (one of the annotations in the GCN output is the list of the Pfam domains for all the proteins in ± 10 or ± 20 ORFs).

Data availability

Data described in this manuscript has been deposited at https://osf.io/p4znk/and is publicly available.

Supporting information

This article contains supporting information including experimental procedures and supporting data.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest with the contents of this article.

Acknowledgments

We thank Squire J. Booker for the gift of the pET28a plasmid that contains the sdaA gene.

Author contributions

J. B. B., B. M. H., W. E. B., B. B., E. M. S., H. Y., and A. P. writing–review & editing, J. B. B. and W. E. B. writing–original draft, J. B. B., B. M. H., and W. E. B. supervision, J. B. B. and G. L. H. methodology, J. B. B. and B. M. H. funding acquisition, J. B. B. and W. E. B. conceptualization; B. B., E. M. S., H. Y., A. D., and A. P. investigation. G. L. H. formal analysis.

Funding and additional information

This work was supported by the U.S. Department of Energy (DE-SC0005404 to J.B.B.), and by the NIH (GM 2 R01 GM111097 to B.M.H.).

Reviewed by members of the JBC Editorial Board. Edited by Joseph Jez

Supporting information

References

- 1.Lubitz W., Ogata H., Rudiger O., Reijerse E. Hydrogenases. Chem. Rev. 2014;114:4081–4148. doi: 10.1021/cr4005814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Esmieu C., Raleiras P., Berggren G. From protein engineering to artificial enzymes - biological and biomimetic approaches towards sustainable hydrogen production. Sustain. Energ. Fuels. 2018;2:724–750. doi: 10.1039/c7se00582b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kleinhaus J.T., Wittkamp F., Yadav S., Siegmund D., Apfel U.P. [FeFe]-Hydrogenases: maturation and reactivity of enzymatic systems and overview of biomimetic models. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2021;50:1668–1784. doi: 10.1039/d0cs01089h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Land H., Senger M., Berggren G., Stripp S. Current state of [FeFe]-Hydrogenase research: biodiversity and spectroscopic investigations. ACS Catal. 2020;10:7069–7086. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Evans R.M., Siritanaratkul B., Megarity C.F., Pandey K., Esterle T.F., Badiani S., et al. The value of enzymes in solar fuels research - efficient electrocatalysts through evolution. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2019;48:2039–2052. doi: 10.1039/c8cs00546j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Peters J.W., Lanzilotta W.N., Lemon B.J., Seefeldt L.C. X-ray crystal structure of the Fe-only hydrogenase (CpI) from Clostridium pasteurianum to 1.8 angstrom resolution. Science. 1998;282:1853–1858. doi: 10.1126/science.282.5395.1853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nicolet Y., Piras C., Legrand P., Hatchikian C.E., Fontecilla-Camps J.C. Desulfovibrio desulfuricans iron hydrogenase: the structure shows unusual coordination to an active site Fe binuclear center. Structure. 1999;7:13–23. doi: 10.1016/s0969-2126(99)80005-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Reijerse E.J., Pham C.C., Pelmenschikov V., Gilbert-Wilson R., Adamska-Venkatesh A., Siebel J.F., et al. Direct observation of an iron-bound terminal hydride in [FeFe]-Hydrogenase by nuclear resonance vibrational spectroscopy. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2017;139:4306–4309. doi: 10.1021/jacs.7b00686. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mulder D.W., Boyd E.S., Sarma R., Lange R.K., Endrizzi J.A., Broderick J.B., et al. Stepwise [FeFe]-hydrogenase H-cluster assembly revealed in the structure of HydA(DeltaEFG) Nature. 2010;465:248–251. doi: 10.1038/nature08993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mulder D.W., Ortillo D.O., Gardenghi D.J., Naumov A., Ruebush S.S., Szilagyi R.K., et al. Activation of HydAΔEFG requires a preformed [4Fe-4S] cluster. Biochemistry. 2009;48:6240–6248. doi: 10.1021/bi9000563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bai Y., Chen T., Happe T., Lu Y., Sawyer A. Iron-sulphur cluster biogenesis via the SUF pathway. Metallomics. 2018;10:1038–1052. doi: 10.1039/c8mt00150b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.King P.W., Posewitz M.C., Ghirardi M.L., Seibert M. Functional studies of [FeFe] hydrogenase maturation in an Escherichia coli biosynthetic system. J. Bacteriol. 2006;188:2163–2172. doi: 10.1128/JB.188.6.2163-2172.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mulder D.W., Shepard E.M., Meuser J.E., Joshi N., King P.W., Posewitz M.C., et al. Insights into [FeFe]-Hydrogenase structure, mechanism, and maturation. Structure. 2011;19:1038–1052. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2011.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pagnier A., Balci B., Shepard E.M., Yang H., Warui D.M., Impano S., et al. [FeFe]-Hydrogenase: defined lysate-free maturation reveals a key role for lipoyl-H-protein in DTMA ligand biosynthesis. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2022;61 doi: 10.1002/anie.202203413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Posewitz M.C., King P.W., Smolinski S.L., Zhang L., Seibert M., Ghirardi M.L. Discovery of two novel radical S-adenosylmethionine proteins required for the assembly of an active [Fe] hydrogenase. J. Biol. Chem. 2004;279:25711–25720. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M403206200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kuchenreuther J.M., Myers W.K., Stich T.A., George S.J., Nejatyjahromy Y., Swartz J.R., et al. A radical intermediate in tyrosine scission to the CO and CN- ligands of FeFe hydrogenase. Science. 2013;342:472–475. doi: 10.1126/science.1241859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kuchenreuther J.M., Myers W.K., Suess D.L.M., Stich T.A., Pelmenschikov V., Shiigi S.A., et al. The HydG enzyme generates an Fe(CO)2(CN) synthon in assembly of the FeFe hydrogenase H-cluster. Science. 2014;343:424–427. doi: 10.1126/science.1246572. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Suess D.L.M., Bürstel I., De La Paz L., Kuchenreuther J.M., Pham C.C., Cramer S.P., et al. Cysteine as a ligand platform in the biosynthesis of the FeFe hydrogenase H cluster. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2015;112:11455–11460. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1508440112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rao G.D., Tao L.Z., Suess D.L.M., Britt R.D. A [4Fe-4S]-Fe(CO)(CN)-L-cysteine intermediate is the first organometallic precursor in [FeFe] hydrogenase H-cluster bioassembly. Nat. Chem. 2018;10:555–560. doi: 10.1038/s41557-018-0026-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pagnier A., Martin L., Zeppieri L., Nicolet Y., Fontecilla-Camps J.C. CO and CN- syntheses by [FeFe]-hydrogenase maturase HydG are catalytically differentiated events. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2016;113:104–109. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1515842113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Shepard E.M., Duffus B.R., McGlynn S.E., Challand M.R., Swanson K.D., Roach P.L., et al. [FeFe]-Hydrogenase maturation: HydG-catalyzed synthesis of carbon monoxide. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2010;132:9247–9249. doi: 10.1021/ja1012273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Driesener R.C., Challand M.R., McGlynn S.E., Shepard E.M., Boyd E.S., Broderick J.B., et al. [FeFe]-hydrogenase cyanide ligands derived from S-adenosylmethionine-dependent cleavage of tyrosine. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 2010;49:1687–1690. doi: 10.1002/anie.200907047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Shepard E.M., Impano S., Duffus B.R., Pagnier A., Duschene K.S., Betz J.N., et al. HydG, the “Dangler” iron, and catalytic production of free CO and CN: implications for [FeFe]-hydrogenase maturation. Dalton Trans. 2021;50:10405–10422. doi: 10.1039/d1dt01359a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Omeiri J., Martin L., Usclat A., Cherrier M.V., Nicolet Y. Maturation of the [FeFe]-hydrogenase: direct transfer of the (k3-cysteinate)FeII(CN)(CO)2 complex B from HydG to HydE. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2023;62 doi: 10.1002/anie.202314819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rohac R., Amara P., Benjdia A., Martin L., Ruffié P., Favier A., et al. Carbon-sulfur bond-forming reaction catalysed by the radical SAM enzyme HydE. Nat. Chem. 2016;8:491–500. doi: 10.1038/nchem.2490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rohac R., Martin L., Liu L., Basu D., Tao L., Britt R.D., et al. Crystal structure of the [FeFe]-hydrogenase maturase HydE bound to Complex-B. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2021;143:8499–8508. doi: 10.1021/jacs.1c03367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tao L., Pattenaude S.A., Joshi S., Begley T.P., Rauchfuss T.B., Britt R.D. The radical SAM enzyme HydE generates adenosylated Fe(I) intermediates en route to the [FeFe]-hydrogenase catalytic H-cluster. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2020;142:10841–10848. doi: 10.1021/jacs.0c03802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Haas R., Engelbrecht V., Lampret O., Yadav S., Apfel U.-P., Leimkühler S., et al. The [4Fe-4S]-cluster of HydF is not required for the binding and transfer of the diiron site of [FeFe]-hydrogenases. Chembiochem. 2023;24 doi: 10.1002/cbic.202300222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Németh B., Land H., Magnuson A., Hofer A., Berggren G. The maturase HydF enables [FeFe] hydrogenase assembly via transient, cofactor-dependent interactions. J. Biol. Chem. 2020;295:11891–11901. doi: 10.1074/jbc.RA119.011419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Németh B., Senger M., Redman H.J., Ceccaldi P., Broderick J., Magnuson A., et al. [FeFe]-hydrogenase maturation: H-cluster assembly intermediates tracked by electron paramagnetic resonance, infrared, and X-ray absorption spectroscopy. J. Biol. Inorg. Chem. 2020;25:777–788. doi: 10.1007/s00775-020-01799-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Byer A.S., Shepard E.M., Ratzloff M.W., Betz J.N., King P.W., Broderick W.E., et al. H-Cluster assembly intermediates built on HydF by the radical SAM enzymes HydE and HydG. J. Biol. Inorg. Chem. 2019;24:783–792. doi: 10.1007/s00775-019-01709-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Scott A.G., Szilagyi R.K., Mulder D.W., Ratzloff M.W., Byer A.S., King P.W., et al. Compositional and structural insights into the nature of the H-cluster precursor on HydF. Dalton Trans. 2018;47:9521–9535. doi: 10.1039/c8dt01654b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Galazzo L., Maso L., De Rosa E., Bortolus M., Doni D., Acquasaliente L., et al. Identifying conformational changes with site-directed spin labeling reveals that the GTPase domain of HydF is a molecular switch. Sci. Rep. 2017;7:1714. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-01886-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Shepard E.M., Byer A.S., Aggarwal P., Betz J.N., Scott A.G., Shisler K.A., et al. Electron spin relaxation and biochemical characterization of the hydrogenase maturase HydF: insights into [2Fe-2S] and [4Fe-4S] cluster communication and hydrogenase activation. Biochemistry. 2017;56:3234–3247. doi: 10.1021/acs.biochem.7b00169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Shepard E.M., Byer A.S., Broderick J.B. Iron-sulfur cluster states of the hydrogenase maturase HydF. Biochemistry. 2017;56:4733–4734. doi: 10.1021/acs.biochem.7b00735. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Caserta G., Pecqueur L., Adamska-Venkatesh A., Papini C., Roy S., Artero V., et al. Structural and functional characterization of the hydrogenase-maturation HydF protein. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2017;13:779–784. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.2385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Shepard E.M., Byer A.S., Betz J.N., Peters J.W., Broderick J.B. A redox active [2Fe-2S] cluster on the hydrogenase maturase HydF. Biochemistry. 2016;55:3514–3527. doi: 10.1021/acs.biochem.6b00528. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Berggren G., Garcia-Serres R., Brazzolotto X., Clemancey M., Gambarelli S., Atta M., et al. An EPR/HYSCORE, Mössbauer, and resonance Raman study of the hydrogenase maturation enzyme HydF: a model for N-coordination to [4Fe-4S] clusters. J. Biol. Inorg. Chem. 2014;19:75–84. doi: 10.1007/s00775-013-1062-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Joshi N., Shepard E.M., Byer A.S., Swanson K.D., Broderick J.B., Peters J.W. Iron–sulfur cluster coordination in the [FeFe]-hydrogenase H cluster biosynthetic factor HydF. FEBS Lett. 2012;586:3939–3943. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2012.09.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Vallese F., Berto P., Ruzzene M., Cendron L., Sarno S., De Rosa E., et al. Biochemical analysis of the interactions between the proteins involved in the [FeFe]-hydrogenase maturation process. J. Biol. Chem. 2012;287:36544–36555. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.388900. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Shepard E.M., McGlynn S.E., Bueling A.L., Grady-Smith C., George S.J., Winslow M.A., et al. Synthesis of the 2Fe-subcluster of the [FeFe]-hydrogenase H-cluster on the HydF scaffold. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2010;107:10448–10453. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1001937107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.McGlynn S.E., Shepard E.M., Winslow M.A., Naumov A.V., Duschene K.S., Posewitz M.C., et al. HydF as a scaffold protein in [FeFe] hydrogenase H-cluster biosynthesis. FEBS Lett. 2008;582:2183–2187. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2008.04.063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Brazzolotto X., Rubach J.K., Gaillard J., Gambarelli S., Atta M., Fontecave M. The [Fe-Fe]-Hydrogenase maturation protein HydF from Thermotoga maritima is a GTPase with an iron-sulfur cluster. J. Biol. Chem. 2006;281:769–774. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M510310200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Zhang Y., Tao L., Woods T.J., Britt R.D., Rauchfuss T.B. Organometallic Fe2(u-SH)2(CO)4(CN)2 cluster allows the biosynthesis of the [FeFe]-hydrogenase with only the HydF maturase. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2022;144:1534–1538. doi: 10.1021/jacs.1c12506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Boyer M.E., Stapleton J.A., Kuchenreuther J.M., Wang C.-w., Swartz J.R. Cell-free synthesis and maturation of [FeFe] Hydrogenases. Biotechnol. Bioengin. 2008;99:59–67. doi: 10.1002/bit.21511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Rao G., Tao L., Britt R.D. Serine is the molecular source of the NH(CH2)2 bridgehead moiety of the in vitro assembled [FeFe] hydrogenase H-cluster. Chem. Sci. 2020;11:1241–1247. doi: 10.1039/c9sc05900h. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Balci B., O’Neill R.D., Shepard E.M., Pagnier A., Marlott A., Mock M.T., et al. Semisynthetic maturation of [FeFe]-hydrogenase using [(FeI)2(μ-SH)2(CN)2(CO)4]2–: key roles for HydF and GTP. Chem. Comm. 2023;59:8929–8932. doi: 10.1039/d3cc02169f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Betz J.N., Boswell N.W., Fugate C.J., Holliday G.L., Akiva E., Scott A.G., et al. [FeFe]-Hydrogenase maturation: insights into the role HydE plays in dithiomethylamine biosynthesis. Biochemistry. 2015;54:1807–1818. doi: 10.1021/bi501205e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Rudolph F.B., Fromm H.J. The purification and properties of aspartase from Escherichia coli. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 1971;147:92–98. doi: 10.1016/0003-9861(71)90313-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Falzone C.J., Karsten W.E., Conley J.D., Viola R.E. L-Aspartase from Escherichia coli: substrate specificity and role of divalent metal ions. Biochemistry. 1988;27:9089–9093. doi: 10.1021/bi00426a004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Cicchillo R.M., Baker M.A., Schnitzer E.J., Newman E.B., Krebs C., Booker S.J. Escherichia coli L-serine deaminase requires a [4Fe-4S] cluster in catalysis. J. Biol. Chem. 2004;279:32418–32425. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M404381200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Okamura-Ikeda K., Hosaka H., Maita N., Fujiwara K., Yoshizawa A.C., Nakagawa A., et al. Crystal structure of aminomethyltransferase in complex with dihydrolipoyl-H-protein of the glycine cleavage system. J. Biol. Chem. 2010;285:18684–18692. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.110718. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Robbins F.M., Fioriti J.A. Alkaline degradation of cystine, glutathione and sulphur-containing proteins. Nature. 1963;200:577–578. doi: 10.1038/200577a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Kredich N.M., Foote L.J., Keenan B.S. The stoichiometry and kinetics of the inducible cysteine desulfhydrase from Salmonella typhimurium. J. Biol. Chem. 1973;248:6187–6196. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Pagnier A., Nicolet Y., Fontecilla-Camps J.C. IscS from Archaeoglobus fulgidus has no desulfurase activity but may provide a cysteine ligand for [Fe2S2] cluster assembly. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2015;1853:1457–1463. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2014.10.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Zhang X., El-Hajj Z.W., Newman E. Deficiency in L-serine deaminase interferes with one-carbon metabolism and cell wall synthesis in Escherichia coli K-12. J. Bacteriol. 2010;192:5515–5525. doi: 10.1128/JB.00748-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Meshulam-Simon G., Behrens S., Choo A.D., Spormann A.M. Hydrogen metabolism in Shewanella oneidensis MR-1. App. Env. Microbiol. 2007;73:1153–1165. doi: 10.1128/AEM.01588-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Kolker E., Picone A.F., Galperin M.Y., Romine M.F., Higdon R., Makarova K.S., et al. Global profiling of Shewanella oneidensis MR-1: expression of hypothetical genes and improved functional annotations. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2005;102:2099–2104. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0409111102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Myers C.R., Nealson K.H. Bacterial manganese reduction and growth with manganese oxide as the sole electron acceptor. Science. 1988;240:1319–1321. doi: 10.1126/science.240.4857.1319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Muyzer G., Stams A.J.M. The ecology and biotechnology of sulphate-reducing bacteria. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2008;6:441–454. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro1892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Matias P.M., Coelho R., Pereira I.A.C., Coelho A.V., Thompson A.W., Sieker L.C., et al. The primary and three-dimensional structures of a nin-haem cytochrome c from Desulfovibrio desulfuricans ATCC 27774 reveal a new member of the Hmc family. Structure. 1999;7:119–130. doi: 10.1016/S0969-2126(99)80019-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Vandieken V., Finke N., Jorgensen B.B. Pathways of carbon oxidation in an Arctic fjord sediment (Svalbard) and isolation of psychrophilic and psychrotolerant Fe(III)-reducing bacteria. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 2006;322:29–41. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Lovley D.R., Phillips E.J., Lonergan D.J., Widman P.K. Fe(III) and S0 reduction by Pelobacter carbinolicus. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 1995;61:2132–2138. doi: 10.1128/aem.61.6.2132-2138.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Pjevac P., Kamyshny A., Dyksma S., Mussmann M. Microbial consumption of zero-valence sulfur in marine benthic habitats. Environ. Microbiol. 2014;16:3416–3430. doi: 10.1111/1462-2920.12410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Kikuchi G., Motokawa Y., Yoshida T., Hiraga K. Glycine cleavage system: reaction mechanism, physiological significance, and hyperglycinemia. Proc. Jpn. Acad. Ser. B Phys. Biol. Sci. 2008;84:246–263. doi: 10.2183/pjab/84.246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Ren J., Wang W., Nie J., Yuan W., Zeng A.P. Understanding and engineering Glycine cleavage system and related metabolic pathways for C1-based biosynthesis. Adv. Biochem. Eng. Biotechnol. 2022;180:273–298. doi: 10.1007/10_2021_186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Hong Y., Ren J., Zhang X., Wang W., Zeng A.P. Quantitative analysis of glycine related metabolic pathways for one-carbon synthetic biology. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 2020;64:70–78. doi: 10.1016/j.copbio.2019.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Gariboldi R.T., Drake H.L. Glycine synthase of the purinolytic bacterium, Clostridium acidiurici. Purification of the glycine-CO2 exchange system. J. Biol. Chem. 1984;259:6085–6089. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Kikuchi G. The glycine cleavage system: composition, reaction mechanism, and physiological significance. Mol. Cell Biochem. 1973;1:169–187. doi: 10.1007/BF01659328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Kikuchi G., Hiraga K. The mitochondrial glycine cleavage system. Unique features of the glycine decarboxylation. Mol. Cell Biochem. 1982;45:137–149. doi: 10.1007/BF00230082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Mulder D.W., Ratzloff M.W., Bruschi M., Greco C., Koonce E., Peters J.W., et al. Investigations on the role of proton-coupled electron transfer in hydrogen activation by [FeFe]-hydrogenase. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2014;136:15394–15402. doi: 10.1021/ja508629m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Walsby C.J., Hong W., Broderick W.E., Cheek J., Ortillo D., Broderick J.B., et al. Electron-nuclear double resonance spectroscopic evidence that S-adenosylmethionine binds in contact with the catalytically active [4Fe-4S]+ cluster of pyruvate formate-lyase activating enzyme. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2002;124:3143–3151. doi: 10.1021/ja012034s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Walsby C.J., Ortillo D., Broderick W.E., Broderick J.B., Hoffman B.M. An anchoring role for FeS Clusters: chelation of the amino acid moiety of S-adenosylmethionine to the unique iron site of the [4Fe-4S] cluster of pyruvate formate-lyase activating enzyme. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2002;124:11270–11271. doi: 10.1021/ja027078v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Byer A.S., McDaniel E.C., Impano S., Broderick W.E., Broderick J.B. Mechanistic studies of radical SAM enzymes: pyruvate formate-lyase activating enzyme and lysine 2,3-aminomutase case studies. Methods Enzymol. 2018;606:269–318. doi: 10.1016/bs.mie.2018.04.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Werst M.M., Davoust C.E., Hoffman B.M. Ligand spin densities in blue copper proteins by Q-band 1H and 14N ENDOR spectroscopy. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1991;113:1533–1538. [Google Scholar]

- 76.Davoust C.E., Doan P.E., Hoffman B.M. Q-band pulsed electron spin-echo spectrometer and its application to ENDOR and ESEEM. J. Magn. Reson. 1996;119:38–44. [Google Scholar]

- 77.Consortium T.U. UniProt: the universal protein knowledgebase in 2023. Nucl. Acids Res. 2023;51:D523–D531. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkac1052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Zallot R., Oberg N., Gerlt J.A. The EFI web resource for genomic enzymology tools: leveraging protein, genome, and metagenome databases to discover novel enzymes and metabolic pathways. Biochemistry. 2019;58:4169–4182. doi: 10.1021/acs.biochem.9b00735. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Oberg N., Zallot R., Gerlt J.A. EFI-EST, EFI-GNT, and EFI-CGFP: enzyme function initiative (EFI) web resource for genomic enzymology tools. J. Mol. Biol. 2023;435 doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2023.168018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Shannon P., Markiel A., Ozier O., Baliga N.S., Wang J.T., Ramage D., et al. Cytoscape: a software environment for integrated models of biomolecular interaction networks. Genome Res. 2003;13:2498–2504. doi: 10.1101/gr.1239303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Data described in this manuscript has been deposited at https://osf.io/p4znk/and is publicly available.