Abstract

Melanosome transport is regulated by major proteins, including Rab27a, Melanophilin (Mlph), and Myosin Va (Myo-Va), that form a tripartite complex. Mutation of these proteins causes melanosome aggregation around the nucleus. Among these proteins, Mlph is a linker between Rab27a and Myo-Va. There are some studies about the regulation of Mlph transcriptional expression. However, its regulation by post-translational modifications remains unclear. In this study, inhibition of HDACs by SAHA and TSA disrupted melanosome transport, causing melanosome aggregation. Specifically, we identified a novel mechanism in which HDAC5 regulates Mlph expression via Sp1. Knockdown of HDAC5 increased the acetylation of Sp1 and the binding to the Mlph promoter, thereby modulating its expression. This study highlights the crucial role of HDAC5 in melanosome transport through its interaction with Sp1. These findings suggest that HDAC5-mediated deacetylation is pivotal in the post-translational modification of melanosome transport, providing insights into the molecular mechanisms underlying this process.

Keywords: Melanosome transport, Melanophilin, Post-translational modifications, Acetylation, Sp1, HDAC5

Subject terms: Post-translational modifications, Post-translational modifications, RNAi, Transcription, Gene expression, Gene regulation, Gene expression analysis

Introduction

Melanosomes are important organelles responsible for the synthesis, storage, and transport of melanin pigments within skin melanocytes1. Mature melanosomes migrate from the perinuclear region to the dendrites of melanocytes. Rab27a, Melanophilin (Mlph, also known as Slac2a), and Myosin Va (Myo-Va), which form a tripartite complex, are well known to be involved in melanosome transport along actin filaments2,3.

Mlph serves as an effector of Rab27a and Myo-Va, thereby acting as a linker between Rab27a and Myo-Va3. Disruption in the expression or function of any one of those proteins of the tripartite complex results in melanosome aggregation around the nucleus.

Histone deacetylases (HDACs) are composed of 18 members. These are divided into two families: the Zn2+-dependent HDAC family composed of class I (HDACs 1, 2, 3, and 8), class II a/b (HDACs 4, 5, 6, 7, 9 and 10), and class IV (HDAC 11) and zn2+-independent NAD-dependent class III SIRT enzymes. HDACs function as erasers that remove acetyl groups from the histones. Deacetylation of histones by HDACs tightens their interaction with DNA, resulting in a chromatin structure and inactive gene expression. Apart from histones, HDACs also regulate the post-translational acetylation of non-histone proteins like transcription factors4,5.

Specificity protein 1 (Sp1) is a transcription factor that can either activate or repress transcription in response to physiological stimuli. Sp1 binds to GC-rich promoter motifs with high affinity and regulates numerous gene expressions involved in diverse biological processes6. The transcriptional activity or stability of Sp1 is modulated by various post-translational modifications (PTM), including acetylation, phosphorylation, SUMOylation, ubiquitination, and glycosylation7.

Among these PTMs, acetylation at lysine 703 (K703) within the DNA-binding domain of Sp1 is particularly noteworthy. Protein acetylation is an important post-translational modification that adds an acetyl group to specific amino acid residues, notably lysine. This addition could change the properties of proteins in many biological processes, like activity, interaction, function, and expression. Acetylation of Sp1 is involved in regulating gene expression8,9. Thus, it could activate or repress gene expression by interacting with histone deacetylases (HDACs) or histone acetyltransferases (HATs)10,11. Especially, many studies have shown that Sp1 acetylation is associated with a change in DNA binding affinity8,9,12. Sp1 acetylation is associated with loss of DNA binding at promoters in cell cycle arrest and cell death in a colon cell line13.

Recently, many studies have confirmed the regulation of various PTMs in the skin14–16. However, no research has confirmed the relationship between PTMs, especially acetylation, and melanosome transport. Therefore, in this study, we aimed to determine how Sp1 acetylation by HDAC5 inhibition regulates melanosome transport in melanocytes.

Results

Treatment of epigenetic modulators for different epigenetic targets

To investigate the relevance of epigenetic regulation in melanosome transport, epigenetic regulators were administered. Suberoylanilide hydroxamic acid (SAHA), Trichostatin A (TSA) Histone deacetylase inhibitors, and 5-aza-2-deoxycytidine (5-aza) DNA methyltransferase inhibitor were selected and treated to melan-a melanocytes. Cell viability was assessed at various concentrations of SAHA, TSA, and 5-aza in melan-a cells. It was confirmed that SAHA up to 1 μM (Supplementary Fig. 1A), TSA up to 25 nM (Supplementary Fig. 1B), and 5-aza up to 10 μM (Supplementary Fig. 1C) did not exhibit cytotoxicity.

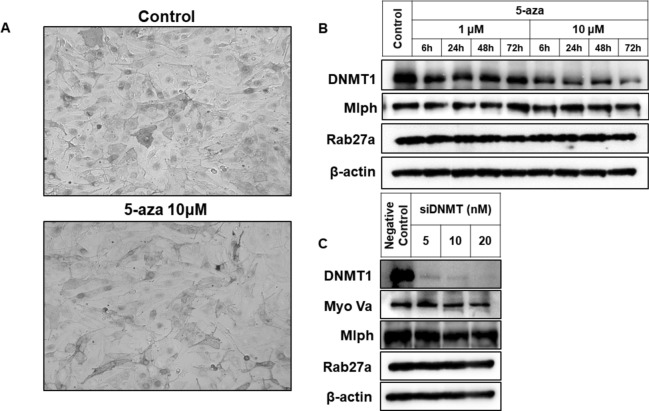

SAHA and TSA inhibit melanosome transport

First, SAHA and TSA, pan-HDAC inhibitors, were administered. As a result, melanosome transport was disrupted, leading to melanosome aggregation around the nucleus by treatment of SAHA (Fig. 1A,B) and TSA (Fig. 1C,D). The expression of three proteins involved in melanosome transport—Rab27a, Mlph, and Myo-Va—was examined. It was found that the protein and mRNA expression of Rab27a and Mlph decreased in a dose- and time-dependent manner following treatment with SAHA (Fig. 1E,F) and TSA (Fig. 1G,H). The protein expression of Myo-Va was not affected by treatment with SAHA and TSA. So, further analysis for the mRNA expression of Myo-Va by treatment with SAHA and TSA was not conducted. In contrast, no melanosome aggregation was observed when the DNMT inhibitor 5-aza was treated (Fig. 2A). Although protein expression of DNMT1 was decreased, no changes in the expression of Myo-Va, Mlph, and Rab27a were confirmed by 5-aza (Fig. 2B). Furthermore, when DNMT1-specific siRNA was transfected, no changes in the expression of these proteins were observed (Fig. 2C). So, further analysis for the mRNA expression of Myo-Va, Mlph, and Rab27a by inhibition of DNMT1 was not conducted. Therefore, these results indicated that SAHA and TSA are involved in the regulation of melanosome transport, suggesting that HDACs play a role in the process.

Fig. 1.

Effect of HDAC inhibition on melanosome transport. (A) Melanosome images by treatment of SAHA were captured in a bright field, and each image was photographed at a magnification of × 100. (B) Quantification of aggregated melanosomes. Values are presented as the mean ± SD of three determinations (n = 3). (C) Melanosome images by treatment of TSA were captured in a bright field, and each image was photographed at a magnification of × 100. (D) Quantification of aggregated melanosomes. Values are presented as the mean ± SD of three determinations (n = 3). (E) The mRNA expression of Rab27a and Mlph was measured by qPCR. Melan-a melanocytes were treated with 0.5 or 1 μM SAHA for indicated times. (F) The protein expression of Rab27a, Mlph, and Myo-Va was analyzed using western blot analysis. Melan-a melanocytes were treated with 0.5 or 1 μM SAHA for indicated times. (G) The mRNA expression of Rab27a and Mlph was measured by qPCR. Melan-a. (H) The protein expression of Rab27a, Mlph, and Myo-Va was analyzed using western blot analysis. Melan-a melanocytes were treated with 10 or 25 nM TSA for indicated times. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001.

Fig. 2.

Effect of DNMT inhibition on melanosome transport. (A) Melanosome images were captured in a bright field, and each image was photographed at a magnification of × 100. (B) The protein expression of Rab27a and Mlph was analyzed using western blot analysis. Melan-a melanocytes were treated 1 or 10 μM 5-aza for indicated times. (C) The protein expression of Rab27a, Mlph, and Myo-Va was analyzed using western blot analysis. Melan-a melanocytes were transfected with 5, 10, or 20 nM of DNMT1-specific siRNA for 72 h.

Screening siRNAs of HDAC to find a specific regulator

To determine which specific HDAC regulates the expression of genes involved in melanosome transport, siRNAs targeting individual HDACs were transfected. Except for sirtuins, NAD+-dependent class III HDACs, other HDACs are composed of 11 HDACs, from HDAC1 to HDAC11. To identify which HDAC specifically regulates gene expression in melanosome transport, siRNAs targeting each HDAC were transfected to the cells. The expression levels of Rab27a and Mlph, which showed a decrease upon SAHA and TSA treatment, were then examined. It was found that, except for HDAC5, none of HDACs-specific siRNA showed a change in expression. Specifically, transfection of siRNA targeting HDAC5 resulted in a decreased expression of Mlph (Supplementary Fig. 2). From these findings, we suggested that HDAC5 is a specific regulator involved in melanosome transport.

HDAC5 regulates melanosome transport

To examine whether HDAC5 regulates melanosome transport, bright-field images showed that melanosomes are aggregated by knockdown of HDAC5 (Fig. 3A,B). There is no cytotoxicity by transfection of 20 nM of HDAC5-specific siRNA (Supplementary Fig. 3). Furthermore, mRNA expression of Mlph was decreased by knockdown of HDAC5 in a time-dependent manner (Fig. 3C). Knockdown of HDAC5 revealed no impact on Rab27a protein expression (Supplementary Fig. 2). So, further analysis for the mRNA expression of Rab27a was not conducted. Protein expression of Mlph was reduced by knockdown of HDAC5 in time- (Fig. 3D,E) and dose- (Fig. 3F,G) dependent manner.

Fig. 3.

Knockdown of HDAC5 regulates melanosome transport. (A) Melanosome images by transfection of siHDAC5 were captured in a bright field, and each image was photographed at a magnification of × 100. (B) Quantification of aggregated melanosomes. Values are presented as the mean ± SD of three determinations (n = 3). (C) The mRNA expression of Mlph and HDAC5 was measured by qPCR. Melan-a melanocytes were transfected with 20 nM of HDAC5-specific siRNA for indicated times. (D) The protein expression of Mlph and HDAC5 was analyzed using western blot analysis. Melan-a melanocytes were transfected with 20 nM of HDAC5-specific siRNA for indicated times. (E) Quantification of the protein expression. Values are presented as the mean ± SD of three determinations (n = 3). (F) The protein expression of Mlph and HDAC5 was analyzed using western blot analysis. Melan-a melanocytes were transfected with 10 or 20 nM of HDAC5-specific siRNA for 72 h. (G) Quantification of the protein expression. Values are presented as the mean ± SD of three determinations (n = 3). *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001.

Sp1 is involved in HDAC5-mediated regulation of Mlph expression

It is well known that transcription is typically activated when histone acetylation increases. However, Mlph expression was decreased by HDAC knockdown (Fig. 3). Therefore, we hypothesized that regulation of Mlph expression by HDAC5 is not through histone acetylation, and another transcription factor may be involved. To investigate the involvement, we used cyclohedximide (CHX), a translation inhibitor. In the presence of CHX, Mlph expression was not affected despite knockdown of HDAC5 (Fig. 4A). Meanwhile, despite the treatment of MG132, a proteasome inhibitor, Mlph expression was also reduced by knockdown of HDAC5 (Fig. 4B). This result means that reduced Mlph expression is not associated with proteasomal degradation and implies that HDAC5 regulates Mlph expression via the involvement of a certain factor.

Fig. 4.

A certain factor is involved in HDAC5-mediated regulation of Mlph expression. (A) Melan-a melanocytes were pre-treated with CHX 35 μM for 30 min, then transfected with HDAC5-specific siRNA. After 72 h, Mlph and HDAC5 expression was analyzed by western blot. (B) Melan-a melanocytes were pre-treated with MG132 100 nM for 30 min, then transfected with HDAC5-specific siRNA. After 72 h, Mlph and HDAC5 expression was analyzed by western blot.

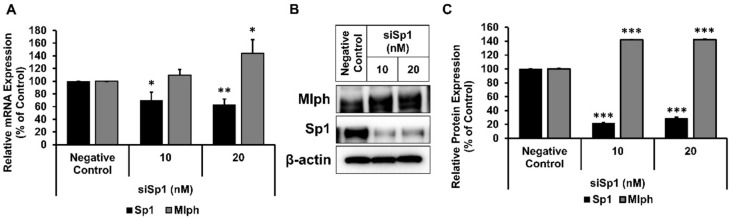

Thus, we predicted the transcription factor that binds to Mlph promoter using Alibaba 2.1 public software tool and chose Sp1 as the transcription factor candidate (Supplementary Fig. 4). We sought to identify Sp1 as a transcription factor involved in HDAC5-mediated regulation. First, to determine the effects of Sp1 on melanosome transport, we transfected Sp1-specific siRNA. mRNA (Fig. 5A) and Protein (Fig. 5B,C) expression of Mlph was increased by knockdown of Sp1. These data provide compelling evidence that Sp1 is involved in the regulation of Mlph expression.

Fig. 5.

Sp1 regulates Mlph expression. (A) The mRNA expression of Mlph and Sp1 was measured by qPCR. Melan-a melanocytes were transfected with 10 or 20 nM of Sp1-specific siRNA for 48 h. (B) The protein expression of Mlph and HDAC5 was analyzed using western blot analysis. Melan-a melanocytes were transfected with 20 nM of Sp1-specific siRNA for indicated times. (C) Quantification of the protein expression. Values are presented as the mean ± SD of three determinations (n = 3). *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001.

Knockdown of HDAC5 does not affect Sp1 expression

HDACs act as a repressor that inactivates transcription17–21. So, we hypothesized that HDAC5 represses Sp1 expression and then regulates Mlph expression. Therefore, it was examined whether Sp1 expression is induced by HDAC5 knockdown. To examine whether HDAC5 affects Sp1 expression, protein expression of Sp1 was confirmed by knockdown of HDAC5. However, Sp1 expression was not changed by knockdown of HDAC5 in a time- (Fig. 6A,B) and dose- (Fig. 6C,D) dependent manner.

Fig. 6.

Sp1 interacts with HDAC5 and its acetylation level is increased by knockdown of HDAC5. (A) The protein expression of Sp1 and HDAC5 was analyzed using western blot analysis. Melan-a melanocytes were transfected with 20 nM of HDAC5-specific siRNA for indicated times. (B) Quantification of the protein expression. Values are presented as the mean ± SD of three determinations (n = 3). (C) The protein expression of Sp1 and HDAC5 was analyzed using western blot analysis. Melan-a melanocytes were transfected with 10 or 20 nM of HDAC5-specific siRNA for 72 h. (D) Quantification of the protein expression. Values are presented as the mean ± SD of three determinations (n = 3). (E) To confirm the interaction of Sp1 and HDAC5, anti-Sp1 immunoprecipitated cells were analyzed using a western blot. To assess the acetylation level of Sp1, anti-acetyl-K immunoprecipitated cells were analyzed using a western blot. Whole-cell lysates were analyzed for total protein levels. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001.

Sp1 interacts with HDAC5 and is acetylated by HDAC5 knockdown

Then, to figure out whether HDAC5 interacts with Sp1, co-immunoprecipitation was performed for protein–protein interaction. Surprisingly, HDAC5 interacts with Sp1, and the acetylation level of Sp1 is increased by transfection of HDAC5-specific siRNA. Above all, the acetylation level of Sp1 increased until 48 h after transfection of HDAC5-specific siRNA and then decreased (Fig. 6E). This indicates that Mlph expression is regulated by the acetylation of Sp1. Furthermore, we confirmed that HDAC5 does not bind Mlph. Taken together, we suggest that HDAC5 regulates Mlph expression by Sp1 acetylation, one of the PTMs, not epigenetic regulation.

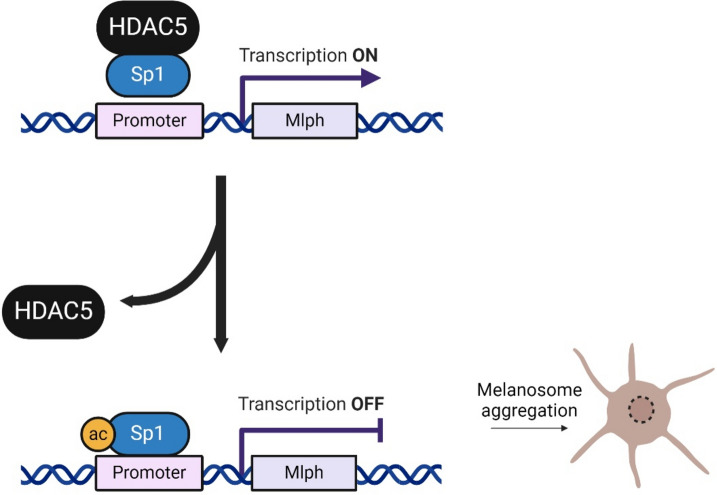

Knockdown of HDAC5 increases Sp1 binding affinity to Mlph promoter

To verify whether HDAC5 affects the binding of Sp1 to the Mlph promoter, we performed Chromatin Immunoprecipitation (ChIP)-PCR. Above all, the binding affinity of Sp1 to Mlph promoter (-176 ~ -35 bp) in the upstream region of the transcription start site (TSS) was examined. The results demonstrated an increase in the binding of Sp1 at the Mlph promoter following HDAC5-specific siRNA transfection (Fig. 7). This indicates that HDAC5 regulates Mlph expression by modulating the binding affinity of Sp1 to the Mlph promoter. As a result, Sp1 functions as a repressor which means the transcriptional activity of Sp1, increased by its acetylation, reduced Mlph expression (Fig. 8).

Fig. 7.

Sp1 acetylation by HDAC5 knockdown increased its transcriptional activity to Mlph promoter region. Binding affinity of Sp1 to the Mlph promoter. Melan-a melanocytes were cultured with siHDAC5 transfection. Chromatin extracts were sheared into < 500 bp. Agarose beads separated fragments bound with Sp1 or IgG from extracts. Sp1 binding affinity was quantified by RT-PCR using primers of the Mlph promoter.

Fig. 8.

Schematic diagram of regulation of Mlph expression by Sp1 acetylation. Figure was created with BioRender.com.

Discussion

Our study investigates the role of Sp1 acetylation in melanosome transport, revealing significant insights into the involvement of HDAC5 and its interaction. Melanosome transport is an important process involving Rab27a, Mlph, and Myo-Va in melanocytes. Mutations in these proteins might lead to Griscelli syndrome, a rare autosomal recessive disease, resulting in abnormal pigmentation22. Above all, the defects of these proteins cause melanosome aggregation around the nucleus. Many attempts have been made to determine the regulation of melanosome transport by regulating Rab27a, Mlph, and Myo-Va expression. Rab27a coordinates actin-dependent transport by controlling organelle-associated motors and assembly proteins23. The glucocorticoid receptor regulates Mlph expression24,25. Exon skipping in Mlph inhibits melanosome transport26. BMP-2 regulates Myosin Va expression through smad in melanocytes27. Despite this interest, there has been little discussion about the association between melanosome transport and PTMs. PTMs could occur on specific amino acids localized within the regulatory domain of target proteins. It could control characteristics of proteins, like stability and activity7. There are some studies about post-translational modifications in the skin. Phosphorylation of Thr328 in hyaluronan synthase2 is required for hyaluronan synthesis14. Especially, in melanocytes, K21 acetylation and Y109 phosphorylation of HINT1 mediates activation of MITF transcriptional activity15. Particularly, our previous study has shown that the absence of Rab27a enhances the ubiquitination of Mlph and induces proteasomal degradation28. Several studies have found that gene expression is regulated by Sp1 DNA binding. Transcriptional repression of E-cadherin is mediated by loss of Sp1 binding at the promoter in nickel-exposed lung epithelial cells9. It has been shown that PTMs of Sp1 could alter its DNA binding. Phosphorylation of Sp1 down-regulates its DNA binding activity upon terminal differentiation of the liver29. Sp1 acetylation is associated with loss of DNA binding at promoters that influence cell cycle arrest and cell death13. Sp1 deacetylation induced by phorbol ester activates 12(s)-lipoxygenase gene expression10. However, an increase of Sp1 binding by its acetylation is still poorly understood. Thus, our study attempts to verify novel mechanisms for melanosome transport regulated by Sp1 acetylation and its transcriptional activity.

Our study has several limitations that should be further researched. First, treatment of SAHA and TSA, not 5-aza, leads to melanosome aggregation and decreases expression of Rab27a and Mlph. However, we examined that HDAC5 specifically regulated only Mlph expression. Therefore, it is needed to understand why Rab27a expression decreases with SAHA and TSA treatment. Second, although there are 18 HDACs including sirtuins, we did not confirm the involvement of sirtuins, to identify the HDACs involved. So, further research is needed on the involvement of sirtuins to determine whether this regulation occurs through post-translational modifications or epigenetic mechanisms. These limitations exist, but we focused on the Mlph expression regulated by protein acetylation by HDAC5 knockdown in this study. Third, our research focuses on the PTMs, not epigenetics. We conducted a study to confirm the association of epigenetic regulation. Contrary to expectations, we demonstrate the association of melanosome transport with acetylation, one of the PTMs. Therefore, further study is required to find a relationship between epigenetic regulation and melanosome transport. Especially, more recent evidence has been revealed in skin melanocytes30–32. MITF functions as a UV-protection timer and is controlled by two negative regulatory loops involving miR-148a and HIF1α33. Likewise, previous work has only focused on melanogenesis, not melanosome transport, in melanocytes. So, it is interesting to demonstrate the epigenetic regulation of melanosome transport. In particular, it seems necessary to further investigate how histone acetyltransferases like P300 perform their function in melanosome transport. Although several studies have investigated epigenetic regulation in the skin through various stimuli34–37, it is necessary to further explore the epigenetic mechanisms in melanocytes under UV or ROS-induced stress to gain a deeper understanding of epigenetic regulation. Nevertheless, this study is the first step towards enhancing our understanding of the action of HDAC on melanosome transport. In addition, the findings have important implications that show novel mechanisms of post-translational acetylation on melanosome transport in skin pigmentation. It may help to develop a novel strategy for anti-pigment targeting Sp1. Besides, Sp1 acetylation, not expression, may also serve as the potential therapeutic target. We think that our findings might be useful for treating skin pigment disorders and give insights into understanding the mechanisms of skin pigment.

Taken together, our study elucidates a distinct role of Sp1 acetylation in regulating Mlph expression by increasing transcriptional activity. Notably, among the examined HDACs, HDAC5 emerged as a specific regulator, as its knockdown not only prevented melanosome aggregation but also reduced Mlph expression. Furthermore, the investigation into the transcriptional regulation of Mlph identified Sp1 as a crucial factor. Increased level of Sp1 acetylation by HDAC5 inhibition indicates that Mlph expression is modulated by HDAC5-mediated sp1 acetylation, thus affecting melanosome transport. Overall, our study highlights the pivotal role of Sp1 as a repressor of Mlph expression and its acetylation reduces Mlph expression by increasing its binding to Mlph promoter region.

Material and methods

Materials

SAHA, TSA, 5-aza (5-aza-2-deoxycytidine), cycloheximide, and MG132 were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (Sigma, Louis, MO).

Cell culture

Melan-a melanocytes are normal, immortalized murine melanocyte cells derived from C57BL/6 mice. Melan-a melanocytes were obtained from Dorothy Bennett (St.George’s Hospital, London, UK). Melan-a melanocytes were maintained in a RPMI-1640 (Welgene, Korea) medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS), 100U/mL penicillin, 100 μg/mL streptomycin, and (p/s; Welgene, Korea), 200 nM phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate (PMA; Sigma-Aldrich).

Small interfering RNAs (siRNAs)

DNMT1 siRNA was purchased from Santa Cruz (Santa Cruz, CA, sc-35203). siRNA oligonucleotides including negative control were synthesized by Bioneer (Daejeon, Korea). The sense and antisense sequences for individual duplexes targeting mouse HDAC1, HDAC2, HDAC3, HDAC4, HDAC5, HDAC6, HDAC7, HDAC8, HDAC9, HDAC10, HDAC11, and Sp1 were as follows:

HDAC1 siRNA sense 5-UGACCAACCAGAACACUAA d(T)d(T)-3′

Antisense 5′-UUAGUGUUCUGGUUGGUCAd(T)d(T)-3′

HDAC2 siRNA sense 5′-CCAAUGAGUUGCCAUAUAAd(T)d(T)-3′

Antisense 5′-UUAUAUGGCAACUCAUUGGd(T)d(T)-3′

HDAC3 siRNA sense 5′-CGGCAGACCUCCUGACGUAd(T)d(T)-3′

Antisense 5′-UACGUCAGGAGGUCUGCCGd(T)d(T)-3′

HDAC4 siRNA sense 5′-GGUUAUGCCUAUCGCAAAUd(T)d(T)-3′

Antisense 5′-AUUUGCGAUAGGCAUAACCd(T)d(T)-3′

HDAC5 siRNA sense 5′-UGACAGCCGUGAUGACUUUd(T)d(T)-3′

Antisense 5′AAAGUCAUCACGGCUGUCAd(T)d(T)-3′

HDAC6 siRNA sense 5′-GGAUGACCCUAGUGUAUUAd(T)d(T)-3′

Antisense 5′-UAAUACACUAGGGUCAUCCd(T)d(T)-3′

HDAC7 siRNA sense 5′-GCUACAAACCCAAGAAAUCd(T)d(T)-3′

Antisense 5′-GAUUUCUUGGGUUUGAUAGCd(T)d(T)-3′

HDAC8 siRNA sense 5′-CAUCGAAGGUUAUGACUGUd(T)d(T)-3′

Antisense 5′-ACAGUCAUAACCUUCGAUGd(T)d(T)-3′

HDAC9 siRNA sense 5′-GCUCCAGGAUUUGUAAUUAd(T)d(T)-3′

Antisense 5′-UAAUUACAAAUCCUGGAGCd(T)d(T)-3′

HDAC10 siRNA sense 5′-GAUGGGAAAUGCCGACUAUd(T)d(T)-3′

Antisense 5′-AUAGUCGGCAUUUCCCAUCd(T)d(T)-3′

HDAC11 siRNA sense 5′-GGUCCGAGCCCAUGAUAUAd(T)d(T)-3′

Antisense 5′-UAUAUCAUGGGCUCGGACCd(T)d(T)-3′

Sp1 siRNA sense 5′-CCACAAGCCCAAACAAUCAd(T)d(T)-3′

Antisense 5′-UGAUUGUUUGGGCUUGUGGd(T)d(T)-3′

siRNA transfection

For transfection, Melan-a melanocytes were seeded in six-well plates at 60% confluency. A mixture of siRNAs and Lipofectamine RNAiMAX Transfection Reagent (Invitrogen, CA) was treated according to the manufacturer’s protocol.

qPCR

Total RNA extracts of Melan-a melanocytes were isolated using TRIZOL (Takara, Shiga, Japan). According to the manufacturer’s protocol. The quality and quantity of each total RNA were measured using a NanoDrop2000 (Thermo Scientific, Rockford, IL). To obtain cDNA, each quantified total RNA was mixed with oligo d(T), followed by denaturation at 65 °C for 5 min and chilling on ice for 5 min. The annealed samples were mixed with reverse transcriptase and 2 mM dNTPs (Fermentas, Waltham, MA, USA) for 1 h at 42 °C. Reverse transcription was terminated at 70 °C for 10 min. mRNA expression was quantified by quantitative real-time PCR using a CFX Connect Real-Time PCR Detection System (Bio-Rad) and FastStart Essential DNA Probes Master (Roche, Mannheim, Germany) was used. The reactions were performed according to the manufacturer’s protocol. TaqMan Pre-Developed Assay Reagents Mouse ACTB (20 X) were used.

Detection and quantification of melanosome aggregation

Melan-a melanocytes were seeded and cultured for 24 h. The cells were then rinsed in DPBS and treated with samples in RPMI-1640 containing 2% FBS for 3 days. Each plate was observed using bright field microscopy. Images were photographed at × 100 magnification using a CELENA S Digital Imaging System (Logos Biosystems, Anyang-si, Korea). Evaluation of melanosome aggregation was performed by counting cells with perinuclear melanosome aggregates in three random microscopic fields per well. Values are presented as the mean ± SD from three wells (n = 3).

Co-immunoprecipitation

Equal amounts of whole cell extracts were rotated and immobilized in protein A/G plus agarose beads (Santacruz, Dallas, TX) with specific antibodies (1–2 μg per 100–500 μg of total proteins) and rotated at 4 °C, overnight. The immobilized agarose beads were washed at least three times with an immunoprecipitation (IP) lysis buffer (Thermo Scientific, Rockford, IL), and then boiled for 5 min. at 95 °C. Equal volumes of supernatants were used for western blotting analysis.

Antibodies

Β-actin antibody (1:10,000, GeneTex, GTX629630), Myosin Va antibody (1:800, Cell Signaling Technology, Beverly, MA, 3402S), Rab27a antibody (1:500, Santa Cruz, CA, sc-74586), Mlph antibody (1:600, Protein Tech Group, Inc, Chicago, IL, 10338-1-AP), DNMT1 antibody (1:1,000, Cell Signaling Technology, Beverly, MA, 5032), Sp1 antibody (1:2,000, Protein Tech Group, Inc, Chicago, IL, 21962–1-AP), and HDAC5 antibody (1:500, Protein Tech Group, Inc, Chicago, IL, 16166-1-AP) were used.

Western blotting

Cells were lysed in a Pierce IP lysis buffer (Thermo Scientific, USA) containing a protease inhibitor cocktail (Sigma, Louis, MO) and 1 mM phenylmethanesulfonyl fluoride (PMSF, Sigma, St. Louis, MO) at 4 °C for 20 min. The lysate was centrifuged at 13,000 rpm for 20 min and the supernatant was obtained. The protein of the supernatant was quantified using a BCA Protein Assay kit with BSA as the standard. Equal amounts of proteins were separated by NuPAGE 4–12% bis–tris gel (Invitrogen, CA, USA) and transferred onto a polyvinylidene fluoride transfer membrane. The blots were blocked with 5% bovine serum albumin (BSA) in Tris Buffered Saline (TBS) containing 10 mM Tris–HCl (pH 7.5), 0.1% Tween-20 and 100 mM NaCl for 1 h at room temperature. Then, the membranes kept at 4 °C with primary antibodies overnight. Horseradish peroxidase conjugated for anti-rabbit (1:20,000, Sigma, St. Louis, MO, USA, A0545) or anti-mouse (1:20,000, Sigma, St. Louis, MO, USA, A9044) were used at 4 °C for 2 h. Binding antibodies were detected using an SuperSignal West Pico PLUS Chemiluminescent substrate (Thermo Scientific, USA). The bands on the membrane were detected with chemiluminescence and visualized using FluorChem E (ProteinSimple, San Jose, CA, USA)38.

Chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) assay

Melan-a melanocytes were fixed with 1% formaldehyde at room temperature for 15 min, followed by the addition of glycine (0.125 M) for 5 min to quench. The harvested cells and precipitated pellets were rinsed twice with ice-cold PBS, and were then resuspended in ice-cold cell lysis buffer (1% SDS, 10 mM EDTA, 50 mM Tris–HCl at pH 8.1 with PIC). The samples were then incubated on ice for 15 min, and then were centrifuged at 13,000 rpm for 1 min. The cell pellets were sonicated to < 500 bp size using a Branson Digital Sonifier SFX 550 (EMERSON, St. Louis, MO, USA) and were then centrifuged at 13,000 rpm for 10 min at 4°C24. An aliquot of each supernatant from the whole cell extracts was acquired as a control. The supernatants were incubated with each antibody against SP1 (Protein Tech Group, Inc, Chicago, IL) and IgG (Invitrogen, CA, USA) at 4 °C overnight. After centrifugation at 13,000 rpm at 4 °C for 10 min, the aggregated pellets were removed. Next, protein A/G beads were incubated on a rotating platform at 4 °C for 45 min. Each bead was rinsed 5 times with ice-cold IP buffer to eliminate non-specific binding. The precipitated material was reverse-crosslinked and boiled with 10% Chelex-100 (Sigma, Louis, MO) for 10 min, after which the tube was briefly centrifuged to acquire the supernatant. The DNA samples obtained were used for PCR and were analyzed by electrophoresis on 2% agarose gels. The primer sequences for Mlph promoter locus were as follows:

Forward 5′-GGTGCCTCTGTCCTCCATAC-3′

Reverse 5′-GCTCAGATCACGTGGGCTAC-3′

Statistical analysis

All data are expressed as the mean ± SD. Statistical significance was determined using Student’s t-test. A value of *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, or ***p < 0.001 was considered statistically significant.

Supplementary Information

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by a grant of the Korea Health Technology R&D Project through the Korea Health Industry Development Institute (KHIDI), funded by the Ministry of Health & Welfare, Republic of Korea (grant number: RS-2023-KH136470)

Author contributions

Conceptualization: CS.Jo and JS.Hwang, Data curation: CS.Jo and HR.Zhao, Formal analysis: CS.Jo, Investigation: CS.Jo, Methodology: CS.Jo, Writing – original draft: CS.Jo, Writing – review&editing: CS.Jo and JS.Hwang, Resources: HR.Zhao, Supervision: JS.Hwang, Project administration: JS.Hwang.

Data availability

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article [and its supplementary information files].

Declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41598-025-86282-7.

References

- 1.Le, L., Sirés-Campos, J., Raposo, G., Delevoye, C. & Marks, M. S. Melanosome biogenesis in the pigmentation of mammalian skin. Integr. Comp. Biol.61, 1517–1545 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fukuda, M. Rab GTPases: Key players in melanosome biogenesis, transport, and transfer. Pigment Cell Melanoma Res.34, 222–235 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hume, A. N., Ushakov, D. S., Tarafder, A. K., Ferenczi, M. A. & Seabra, M. C. Rab27a and MyoVa are the primary Mlph interactors regulating melanosome transport in melanocytes. J. Cell. Sci.120, 3111–3122 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Asmamaw, M. D., He, A., Zhang, L., Liu, H. & Gao, Y. Histone deacetylase complexes: Structure, regulation and function. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta Rev. Cancer6, 189150 (2024). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Krämer, O. H., Göttlicher, M. & Heinzel, T. Histone deacetylase as a therapeutic target. Trends Endocrinol. Metabol.12, 294–300 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Safe, S., Imanirad, P., Sreevalsan, S., Nair, V. & Jutooru, I. Transcription factor Sp1, also known as specificity protein 1 as a therapeutic target. Expert Opinion Therap. Targets18, 759–769 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lee, J. M., Hammarén, H. M., Savitski, M. M. & Baek, S. H. Control of protein stability by post-translational modifications. Nat. Commun.14, 201 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zannetti, A. et al. Coordinate up-regulation of Sp1 DNA-binding activity and urokinase receptor expression in breast carcinoma. Cancer Res.60, 1546–1551 (2000). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zhang, X., Tanwar, V. S., Jose, C. C., Lee, H. & Cuddapah, S. Transcriptional repression of E-cadherin in nickel-exposed lung epithelial cells mediated by loss of Sp1 binding at the promoter. Mol. Carcinog.61, 99–110 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hung, J., Wang, Y. & Chang, W. Sp1 deacetylation induced by phorbol ester recruits p300 to activate 12 (S)-lipoxygenase gene transcription. Mol. Cell. Biol.26, 1770–1785 (2006). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Doetzlhofer, A. et al. Histone deacetylase 1 can repress transcription by binding to Sp1. Mol. Cell. Biol.19, 5504–5511 (1999). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Torigoe, T. et al. Low pH enhances Sp1 DNA binding activity and interaction with TBP. Nucleic Acids Res.31, 4523–4530 (2003). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Waby, J. S. et al. Sp1 acetylation is associated with loss of DNA binding at promoters associated with cell cycle arrest and cell death in a colon cell line. Mol. Cancer9, 1–16 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kasai, K. et al. Phosphorylation of Thr328 in hyaluronan synthase 2 is essential for hyaluronan synthesis. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun.533, 732–738 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Motzik, A. et al. Post-translational modification of HINT1 mediates activation of MITF transcriptional activity in human melanoma cells. Oncogene36, 4732–4738 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kobayashi-Nakamura, K., Kudo, M. & Naito, K. Rhamnazin suppresses melanosome transport by promoting the ubiquitin-mediated proteasomal degradation of melanophilin. J. Dermatol. Sci.105, 45–54 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Choi, J. K. & Kim, Y. Epigenetic regulation and the variability of gene expression. Nat. Genet.40, 141–147 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Xu, W., Parmigiani, R. B. & Marks, P. A. Histone deacetylase inhibitors: Molecular mechanisms of action. Oncogene26, 5541–5552 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chen, H. P., Zhao, Y. T. & Zhao, T. C. Histone deacetylases and mechanisms of regulation of gene expression. Crit. Rev. Oncogenesis20, 1–2 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sada, N. et al. Inhibition of HDAC increases BDNF expression and promotes neuronal rewiring and functional recovery after brain injury. Cell Death Dis.11, 655 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Suzuki, S., Sasaki, K., Fahreza, R. R., Nemoto, E. & Yamada, S. The histone deacetylase inhibitor MS-275 enhances the matrix mineralization of dental pulp stem cells by inducing fibronectin expression. J. Dent. Sci.19, 1680–1690 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Van Gele, M., Dynoodt, P. & Lambert, J. Griscelli syndrome: A model system to study vesicular trafficking. Pigment Cell Melanoma Res.22, 268–282 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Alzahofi, N. et al. Rab27a co-ordinates actin-dependent transport by controlling organelle-associated motors and track assembly proteins. Nat. Commun.11, 3495 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Myung, C. H., Lee, J. E., Jo, C. S., Park, J. I. & Hwang, J. S. Regulation of Melanophilin (Mlph) gene expression by the glucocorticoid receptor (GR). Sci. Rep.11, 16813 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Myung, C., Jo, C. & Hwang, J. Phosphorylation of glucocorticoid receptor induced by 16-kauren-2-beta-18, 19-triol decreases expression of Melanophilin through JNK signalling. Exp. Dermatol.32, 1394–1401 (2023). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kim, J. Y. et al. Inhibition of melanosome transport by inducing exon skipping in melanophilin. Biomol. Therap.31, 466 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Park, J. Y., Jo, C. S., Ku, C. & Hwang, J. S. BMP-2 regulates the expression of myosin Va via smad in melan-a melanocyte. Arch. Dermatol. Res.316, 225 (2024). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Park, J. I. et al. The absence of Rab27a accelerates the degradation of Melanophilin. Exp. Dermatol.28, 90–93 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Leggett, R. W., Armstrong, S. A., Barry, D. & Mueller, C. R. Sp1 is phosphorylated and Its DNA binding activity down-regulated upon terminal differentiation of the liver (∗). J. Biol. Chem.270, 25879–25884 (1995). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zhou, S. et al. Epigenetic regulation of melanogenesis. Ageing Res. Rev.69, 101349 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Raja, D. A. et al. pH-controlled histone acetylation amplifies melanocyte differentiation downstream of MITF. EMBO Rep.21, e48333 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Diener, J. et al. Epigenetic control of melanoma cell invasiveness by the stem cell factor SALL4. Nat. Commun.12, 5056 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Malcov-Brog, H. et al. UV-protection timer controls linkage between stress and pigmentation skin protection systems. Mol. Cell72, 444-456.e7 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kim, S. & Pfeifer, G. P. The epigenetic DNA modification 5-carboxylcytosine promotes high levels of cyclobutane pyrimidine dimer formation upon UVB irradiation. Genome Instabil. Dis.2, 59–69 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Letsiou, S., Kapazoglou, A., Tsaftaris, A., Spanidi, E. & Gardikis, K. Transcriptional and epigenetic effects of Vitis vinifera L. leaf extract on UV-stressed human dermal fibroblasts. Mol. Biol. Rep.47, 5763–5772 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Li, S. et al. UVB drives metabolic rewiring and epigenetic reprograming and protection by sulforaphane in human skin keratinocytes. Chem. Res. Toxicol.35, 1220–1233 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kang, K. A. et al. Korean red ginseng attenuates particulate matter-induced senescence of skin keratinocytes. Antioxidants12, 1516 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Jo, C. S. et al. A novel function of Prohibitin on melanosome transport in melanocytes. Theranostics10, 3880 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article [and its supplementary information files].