Abstract

Visual-language models (VLMs) excel in cross-modal reasoning by synthesizing visual and linguistic features. Recent VLMs use prompt learning for fine-tuning, allowing adaptation to various downstream tasks. TCP applies class-aware prompt tuning to improve VLMs generalization, yet its reliance on fixed text templates as prior knowledge can limit adaptability to fine-grained category distinctions. To address this, we propose Custom Text Generation-based Class-aware Prompt Tuning (CuTCP). CuTCP leverages large language models to generate descriptive, category-specific prompts, embedding richer semantic information that enhances the model’s ability to differentiate between known and unseen categories. Compared with TCP, CuTCP achieves an improvement of 0.74% on new classes and 0.44% on overall harmonic mean, averaged over 11 diverse image datasets. Experimental results demonstrate that CuTCP addresses the limitations of general prompt templates, significantly improving model adaptability and generalization capability, with particularly strong performance in fine-grained classification tasks.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41598-025-85838-x.

Keywords: CLIP, CuTCP, Prompt learning, TCP, VLMs

Subject terms: Computer science, Software

Introduction

Visual-language models (VLMs) have recently become a key focus in the field of artificial intelligence research. Notably, CLIP1 and Align2 were trained on vast image-text pairs, enabling them to integrate visual and linguistic features within a shared feature space. This allows for robust cross-modal understanding and reasoning. Although these pre-trained models exhibit strong generalization, distribution shifts between pre-training and downstream tasks often result in suboptimal performance on new tasks. Thus, improving the adaptability of pre-trained models for downstream applications is a critical area of research. Prompt learning, which began in natural language processing (NLP), guides pre-trained models to generate desired outputs using specific textual prompts. Zhou et al.3 introduced learnable prompts to improve model adaptability, extending prompt learning to VLMs. Recent advancements include TCP4 (Textual-based Class-aware Prompt Tuning), which integrates category-specific knowledge into learnable prompts to enable dynamic adaptation for downstream tasks. However, TCP’s fixed templates lack the depth of prior knowledge needed for nuanced category distinctions, potentially limiting the model’s potential.

To address these limitations, we propose Custom Text Generation-based Class-aware Prompt Tuning (CuTCP). By utilizing large language models to generate expressive, category-specific prompts, CuTCP enhances the model’s capacity to differentiate categories, thus strengthening generalization across downstream tasks.

Related works

Prompt learning originated in natural language processing, where specific prompt templates were designed to reframe downstream tasks as ones the model encountered during pre-training, minimizing the need for parameter adjustments. Within VLMs, prompt learning techniques optimize textual or visual prompts, enabling models to adapt effectively to the distributions of downstream tasks. Recently, prompt learning has been widely applied in VLMs, establishing itself as a highly effective fine-tuning approach.

Zhou et al.3 proposed a method called CoOp, which replaces fixed text prompt templates (“a photo of {class-name}”) with adaptable, learnable textual prompts. This approach keeps the pre-trained model parameters frozen while using backpropagation to optimize prompts specifically for downstream tasks. Other methods incorporate learnable parameters as visual prompts within the input space of images5 or within vision transformers6,7, further broadening prompt learning applications. Although CoOp improves performance on training data, subsequent research8 has shown that the learned prompts can overfit training categories, limiting generalization on unseen categories.

To mitigate this issue, Zhou et al.8 introduced a conditional prompt learning technique that incorporates image features into the textual prompts, making them more dynamic and improving generalization on new categories. Yao et al.9 introduced knowledge-guided consistency constraints to minimize disparities between learned and fixed prompt features, reducing overfitting. Khattak et al.10 further enhanced prompt learning by simultaneously applying it to both textual and visual encoders and utilizing a coupling function to synchronize textual and visual prompts, thereby improving synergy between language and visual modalities. Khattak et al.11 introduced a self-regulating prompt learning framework that uses regularization to maintain consistency between learned prompt features and original VLM features, enhancing both robustness and generalization. Yao et al.4 proposed the Textual Knowledge Embedding (TKE) module, which incorporates category-specific prior knowledge into prompts to generate class-aware textual features, thereby enhancing the model’s ability to generalize.

With advancements in large language models (LLMs), researchers are exploring ways to leverage LLMs’ extensive knowledge to create more effective prompts. Pratt et al.12 generates descriptive prompts from LLMs that capture key category features, enabling better differentiation between fine-grained classes and thus improving zero-shot classification performance. Menon et al.13 generates multiple fine-grained textual descriptions per category, assigns classification decision scores based on feature similarity between images and text, and enhances recognition in complex categories. Novack et al.14 employs LLMs to produce various subclass descriptions, performing zero-shot classification on subclasses and mapping them back to the main category, improving classification accuracy.

Building on TCP, our method diverges by replacing fixed textual templates with custom textual prompts enriched with prior knowledge. These prompts serve as knowledge embeddings, enhancing the model’s ability to distinguish fine-grained semantic differences between categories and improving reasoning and classification for complex and unseen categories.

Methods

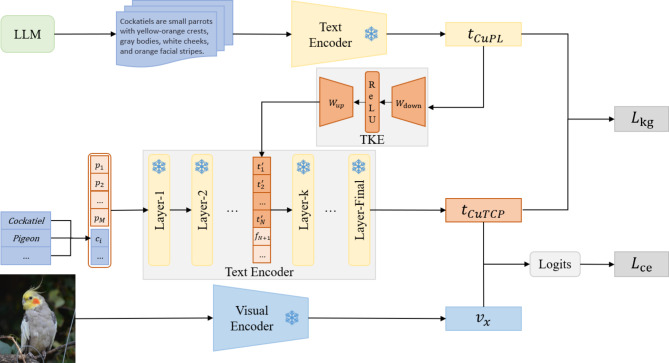

This section introduces CuTCP (Custom Text Generation-based Class-aware Prompt Tuning), our proposed method that integrates recent advancements in prompt learning and fine-tunes the CLIP model. Figure 1 illustrates the overall framework of the CuTCP method.

Fig. 1.

CuTCP overall framework. Combines custom prompts generated by large language models, learning class-aware prompt features through a knowledge embedding module.

Preliminaries

Contrastive Language-Image Pre-training (CLIP)

Most existing VLMs research is based on the CLIP1. which includes two encoders: a text encoder  , typically based on the Transformer15, for encoding input text descriptions into text features, and an image encoder

, typically based on the Transformer15, for encoding input text descriptions into text features, and an image encoder  , typically based on ResNet16 or Vision Transformer6, for encoding input images into visual features. For a classification task with

, typically based on ResNet16 or Vision Transformer6, for encoding input images into visual features. For a classification task with  categories, the visual feature of an image

categories, the visual feature of an image  from dataset

from dataset  is obtained using the visual encoder,

is obtained using the visual encoder,  . The dataset’s category labels

. The dataset’s category labels  are embedded in a text prompt template such as “a photo of {class-name},” generating text embeddings

are embedded in a text prompt template such as “a photo of {class-name},” generating text embeddings  , where

, where  is the label for the

is the label for the  -th category, and

-th category, and  and

and  are the start and end token embeddings. The prompt template features

are the start and end token embeddings. The prompt template features  are then obtained by encoding

are then obtained by encoding  through the text encoder. The model’s predicted probability

through the text encoder. The model’s predicted probability  for the true label

for the true label  of the input image

of the input image  is calculated as shown in Eq. (1):

is calculated as shown in Eq. (1):

|

1 |

where  is the temperature parameter, and

is the temperature parameter, and  denotes cosine similarity.

denotes cosine similarity.

Context optimization (CoOp)

CoOp3 introduces learnable soft text prompts to replace traditional fixed prompt templates. Specifically, CoOp uses learnable word embedding vectors  to replace fixed template word embeddings. These embeddings are combined with the word embedding

to replace fixed template word embeddings. These embeddings are combined with the word embedding  corresponding to the category label

corresponding to the category label  , forming a learnable text embedding

, forming a learnable text embedding  . The learnable text prompt features

. The learnable text prompt features  are then obtained through the text encoder. During training, the text encoder’s parameters are frozen, and the learnable word embeddings are optimized using cross-entropy loss

are then obtained through the text encoder. During training, the text encoder’s parameters are frozen, and the learnable word embeddings are optimized using cross-entropy loss  , as shown in Eq. (2):

, as shown in Eq. (2):

|

2 |

Knowledge-guided Context optimization (kgCoOp)

KgCoOp9 builds on CoOp by applying a knowledge-guided consistency constraint  between the fixed text template features

between the fixed text template features  and the learnable text prompt features

and the learnable text prompt features  to reduce feature discrepancies. This approach prevents overfitting to training data during fine-tuning, preserves general knowledge in VLMs, and improves generalization to unseen categories. The knowledge-guided consistency constraint

to reduce feature discrepancies. This approach prevents overfitting to training data during fine-tuning, preserves general knowledge in VLMs, and improves generalization to unseen categories. The knowledge-guided consistency constraint  is calculated as shown in Eq. (3):

is calculated as shown in Eq. (3):

|

3 |

where  denotes Euclidean distance.

denotes Euclidean distance.

Textual-based Class-aware prompt tuning (TCP)

TCP4 enhances model generalization by integrating category-specific textual knowledge into learnable prompt features via the Textual Knowledge Embedding (TKE) module. The TKE module consists of a down-projection layer  and an up-projection layer

and an up-projection layer  . Given text template features

. Given text template features  , where d is the dimensionality of text features,

, where d is the dimensionality of text features,  first reduces dimensionality to produce lower-dimensional features

first reduces dimensionality to produce lower-dimensional features  , where

, where  represents the reduced feature size. Then,

represents the reduced feature size. Then,  increases the dimensionality, resulting in class-aware textual feature tokens

increases the dimensionality, resulting in class-aware textual feature tokens  , where

, where  and

and  is the length of learnable prompts. The reshaped

is the length of learnable prompts. The reshaped  matches the dimensionality of the learnable prompt features and is added to the k-th layer of the text encoder alongside original input features

matches the dimensionality of the learnable prompt features and is added to the k-th layer of the text encoder alongside original input features  . For each category’s original input feature

. For each category’s original input feature  , the textual features

, the textual features  are combined with corresponding tokens

are combined with corresponding tokens  from

from  , defining the combined feature

, defining the combined feature  as shown in Eq. (4):

as shown in Eq. (4):

|

4 |

where  is the weight for

is the weight for  . This process yields the textual knowledge embedding features

. This process yields the textual knowledge embedding features  for each category. The combined features

for each category. The combined features  form the input

form the input  for the

for the  -th layer. After passing through the remaining layers, this produces the class-aware textual prompt features

-th layer. After passing through the remaining layers, this produces the class-aware textual prompt features  .

.

Custom text generation-based Class-aware prompt tuning

TCP employs a Textual Knowledge Embedding module to incorporate category-level textual knowledge into learnable prompts, producing class-aware features. This method enables the model to utilize richer category-specific knowledge, creating more distinctive textual features, thereby improving classification on base categories and enhancing reasoning on new categories. However, TCP’s use of a fixed template for textual knowledge (e.g., “a photo of {class-name}, a type of flower.“) provides limited semantic specificity, which may restrict fine-grained differentiation, especially within complex or ambiguous categories, and limit overall classification performance.

Inspired by CuPL12, we introduce a large language model to generate detailed, descriptive prompts for each category, embedding these as prior knowledge in the learnable prompt features. This approach infuses the model with knowledge containing fine-grained semantic information, allowing better differentiation between categories and addressing the limitations of general prompt templates to produce more effective class-aware features. Leveraging semantic nuances among categories, the model can exhibit enhanced differentiation on training categories and demonstrate robust reasoning on unseen categories. Even for previously untrained categories, the model can effectively classify them with these semantically rich prompts.

We use GPT-317 as the language model to generate prompts. For each category  , following the CuPL approach, we apply

, following the CuPL approach, we apply  query templates

query templates  to generate custom prompts, such as “Describe what a(n) {class-name} looks like?” and “How can you identify a(n) {class-name}?” Each template

to generate custom prompts, such as “Describe what a(n) {class-name} looks like?” and “How can you identify a(n) {class-name}?” Each template  generates

generates  custom prompts, resulting in

custom prompts, resulting in  prompts for each category

prompts for each category  . These prompts are encoded through the text encoder, and the average feature of all custom prompts is computed as

. These prompts are encoded through the text encoder, and the average feature of all custom prompts is computed as  , defined as shown in Eq. (5):

, defined as shown in Eq. (5):

|

5 |

where  is the

is the  -th custom prompt generated for category

-th custom prompt generated for category  . Subsequently,

. Subsequently,  serves as category-specific prior knowledge and passes through the TKE module to produce class-aware textual tokens

serves as category-specific prior knowledge and passes through the TKE module to produce class-aware textual tokens  . These tokens are added to intermediate layers of the text encoder and combined with learnable text features, ultimately generating class-aware textual features

. These tokens are added to intermediate layers of the text encoder and combined with learnable text features, ultimately generating class-aware textual features  .

.

CuTCP optimization is achieved by combining cross-entropy loss  with a knowledge-guided consistency constraint

with a knowledge-guided consistency constraint  , resulting in the final objective, as shown in Eq. (6):

, resulting in the final objective, as shown in Eq. (6):

|

6 |

where  is consistent with KgCoOp and set to 8.0.

is consistent with KgCoOp and set to 8.0.

Results

Experimental setup

To thoroughly evaluate CuTCP’s performance, we tested it across four benchmarks:

Generalization from base to new classes

We divided each dataset into base and new classes. After training on the base classes, the model was tested on separate test sets for both base and new classes to measure its generalization capability.

Few-shot learning

To assess learning ability under limited data, the model was trained on only a small number of samples in each dataset.

Cross-dataset transfer

After training on ImageNet18, the model’s generalization was evaluated using zero-shot classification on several other datasets.

Domain generalization

We trained the model on ImageNet, then tested it on multiple ImageNet variants with distinct domain distributions to evaluate generalization and robustness across different domains.

Datasets

We used the same image datasets as prior studies. For the generalization from base to new classes, cross-dataset transfer, and few-shot learning benchmarks, we selected 11 image datasets spanning a variety of recognition tasks, including: ImageNet and Caltech10119 for general object classification; OxfordPets20, StanfordCars21, Flowers10222, Food10123, and FGVCAircraft24 for fine-grained classification; SUN39725 for scene recognition; UCF10126 for action recognition; DTD27 for texture classification; and EuroSAT28 for remote sensing. In the domain generalization benchmark, we employed four ImageNet variants with different domain distributions, including ImageNet-V229, ImageNet-Sketch30, ImageNet-A31, and ImageNet-R32.

Implementation details

Our method is based on the CoOp open-source codebase. Following the TCP experimental setup, we used the pre-trained ViT-B/16 CLIP model with a prompt length (M) set to 4, initialized as “X X X X {}”. The model was trained using the Adam optimizer with an initial learning rate of 0.002, a cosine annealing strategy for learning rate decay, a batch size of 32, and a prompt weight ω of 1.0. Using the custom query templates provided by CuPL, GPT-3 DaVinci-002 generates text prompts with the parameters set to a maximum token of 50 and a temperature of 0.99. The generation process stops early upon reaching a period. In tests for generalization from base to new classes and few-shot learning, we trained the model for 50 epochs per dataset; in cross-dataset transfer and domain generalization tests, we used ImageNet as the source dataset and trained for 30 epochs. All training was conducted on a single RTX 4090 GPU. To ensure stability and fairness, experiments were run with three random seeds (1/2/3), and results were averaged.

Generalization from base to new classes

Following prior research, we divided each dataset into base and new class groups. The model was trained on base classes and evaluated on both the base and new class test sets. Each base class consisted of 16 images, and the overall performance was measured using the harmonic mean (HM). TCP was used as the baseline model, and Table 1 compares CuTCP’s performance with other methods in the generalization tests from base to new classes.

Table 1.

Generalization evaluation from base to new classes.

| Dataset | CLIP | CoOp | KgCoOp | TCP | CuTCP | ∆ | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ImageNet | Base | 72.43 | 76.46 | 75.83 | 77.27 | 77.73 | + 0.46 |

| New | 68.14 | 66.31 | 69.96 | 69.87 | 70.50 | + 0.63 | |

| HM | 70.22 | 71.02 | 72.78 | 73.38 | 73.94 | + 0.56 | |

| Caltech101 | Base | 96.84 | 98.11 | 97.72 | 98.23 | 98.47 | + 0.24 |

| New | 94.00 | 93.52 | 94.39 | 94.67 | 95.27 | + 0.60 | |

| HM | 95.40 | 95.76 | 96.03 | 96.42 | 96.84 | + 0.42 | |

| OxfordPets | Base | 91.17 | 94.24 | 94.65 | 94.67 | 95.07 | + 0.40 |

| New | 97.26 | 96.66 | 97.76 | 97.20 | 97.83 | + 0.63 | |

| HM | 94.12 | 95.43 | 96.18 | 95.92 | 96.43 | + 0.51 | |

| StanfordCars | Base | 63.37 | 76.20 | 71.76 | 80.80 | 80.23 | -0.57 |

| New | 74.89 | 69.14 | 75.04 | 74.13 | 74.27 | + 0.14 | |

| HM | 68.65 | 72.49 | 73.36 | 77.32 | 77.13 | -0.19 | |

| Flowers102 | Base | 72.08 | 97.63 | 95.00 | 97.73 | 98.10 | + 0.37 |

| New | 77.80 | 69.55 | 74.73 | 75.57 | 75.58 | + 0.01 | |

| HM | 74.83 | 81.23 | 83.65 | 85.23 | 85.38 | + 0.15 | |

| Food101 | Base | 90.10 | 89.44 | 90.50 | 90.57 | 90.47 | -0.10 |

| New | 91.22 | 87.50 | 91.70 | 91.37 | 91.77 | + 0.40 | |

| HM | 90.66 | 88.46 | 91.09 | 90.97 | 91.11 | + 0.14 | |

| FGVCAircraft | Base | 27.19 | 39.24 | 36.21 | 41.97 | 42.43 | + 0.46 |

| New | 36.29 | 30.49 | 33.55 | 34.43 | 36.37 | + 1.94 | |

| HM | 31.09 | 34.30 | 34.83 | 37.83 | 39.17 | + 1.34 | |

| SUN397 | Base | 69.36 | 80.85 | 80.29 | 82.63 | 83.00 | + 0.37 |

| New | 75.35 | 68.34 | 76.53 | 78.20 | 78.23 | + 0.03 | |

| HM | 72.23 | 74.07 | 78.36 | 80.35 | 80.55 | + 0.20 | |

| DTD | Base | 53.24 | 80.17 | 77.55 | 82.77 | 83.00 | + 0.23 |

| New | 59.90 | 47.54 | 54.99 | 58.07 | 59.40 | + 1.33 | |

| HM | 56.37 | 59.68 | 64.35 | 68.25 | 69.24 | + 0.99 | |

| EuroSAT | Base | 56.48 | 91.54 | 85.64 | 91.63 | 90.87 | -0.76 |

| New | 64.05 | 54.44 | 64.34 | 74.73 | 77.13 | + 2.40 | |

| HM | 60.03 | 68.27 | 73.48 | 82.32 | 83.44 | + 1.12 | |

| UCF101 | Base | 70.53 | 85.14 | 82.89 | 87.13 | 86.87 | -0.26 |

| New | 77.50 | 64.47 | 76.67 | 80.77 | 80.80 | + 0.03 | |

| HM | 73.85 | 73.37 | 79.65 | 83.83 | 83.72 | -0.11 | |

| Avg | Base | 69.34 | 82.63 | 80.73 | 84.13 | 84.21 | + 0.08 |

| New | 74.22 | 67.99 | 73.60 | 75.36 | 76.10 | + 0.74 | |

| HM | 71.70 | 74.60 | 77.00 | 79.51 | 79.95 | + 0.44 | |

Trained with 16 images per class, comparing model performance with other methods. ∆ represents the improvement in classification accuracy of CuTCP compared to TCP, HM is the harmonic mean, and Avg is the average performance across 11 datasets.

As shown in Table 1, CuTCP improves accuracy on new classes compared to TCP across all datasets and increases the HM value on 9 datasets. Across the 11 datasets, CuTCP achieves an average improvement of 0.08% on base classes, 0.74% on new classes, and a 0.44% increase in the HM value. Notably, CuTCP outperforms TCP on both base and new classes in 7 datasets: ImageNet, Caltech101, OxfordPets, Flowers102, FGVCAircraft, SUN397, and DTD. This result suggests that custom prompts enhance the model’s ability to learn fine-grained category differences, yielding better classification performance. The effect is especially evident in tasks requiring fine-grained classification (e.g., OxfordPets, Flowers102, FGVCAircraft) and in complex-background scenes (e.g., SUN397, DTD), where CuTCP’s enriched semantic prompts help to better distinguish category-specific features, thereby enhancing generalization and discrimination.

However, in StanfordCars, Food101, EuroSAT, and UCF101, CuTCP shows a slight decrease in performance on base classes relative to TCP, likely due to the added prompts introducing redundant or non-essential information, diminishing the training effect on base classes. Additionally, in datasets like Food101 and UCF101, where feature distinctions are more apparent, TCP’s original prompting mechanism effectively captures core features, reducing CuTCP’s advantage. Overall, CuTCP achieves notable improvements over TCP in most datasets, with particularly strong gains in new class performance.

Few-shot learning

In the few-shot learning test, we trained each category within a 4-shot setting to assess few-shot learning performance. Table 2 compares CuTCP’s performance with other methods in this test.

Table 2.

Few-shot learning evaluation.

| Dataset | CLIP | CoOp | KgCoOp | TCP | CuTCP | ∆ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ImageNet | 66.73 | 69.38 | 70.19 | 70.48 | 69.93 | -0.55 |

| Caltech101 | 93.30 | 94.44 | 94.65 | 95.00 | 95.43 | + 0.43 |

| OxfordPets | 89.10 | 91.30 | 93.20 | 91.90 | 92.93 | + 1.03 |

| StanfordCars | 65.70 | 72.73 | 71.98 | 76.30 | 76.00 | -0.30 |

| Flowers102 | 70.70 | 91.14 | 90.69 | 94.40 | 94.17 | -0.23 |

| Food101 | 85.90 | 82.58 | 86.59 | 85.30 | 85.83 | + 0.53 |

| FGVCAircraft | 24.90 | 33.18 | 32.47 | 36.20 | 37.40 | + 1.20 |

| SUN397 | 62.60 | 70.13 | 71.79 | 72.11 | 73.60 | + 1.49 |

| DTD | 44.30 | 58.57 | 58.31 | 63.97 | 64.70 | + 0.73 |

| EuroSAT | 48.30 | 68.62 | 71.06 | 77.43 | 74.20 | -3.23 |

| UCF101 | 67.60 | 77.41 | 78.40 | 80.83 | 81.37 | + 0.54 |

| Avg | 65.37 | 73.59 | 74.48 | 76.72 | 76.87 | + 0.15 |

All categories across 11 datasets trained under the 4-shot setting, comparing model performance with other methods.

As shown in Table 2, CuTCP outperforms TCP on 7 datasets, with notable improvements in OxfordPets, FGVCAircraft, and SUN397 of 1.03%, 1.20%, and 1.49%, respectively. This result indicates that CuTCP’s diverse prompts provide the model with enriched prior knowledge, enabling it to capture category features more effectively in data-limited scenarios. However, in the EuroSAT dataset, CuTCP’s performance dropped by 3.23%, likely due to the presence of several visually similar remote sensing categories (e.g., Forest, Pasture, Permanent Crop), which overlap significantly in color and shape. With only 4 images per class, the model finds it challenging to extract distinctive semantic features, leading to noise and reducing classification accuracy. Overall, CuTCP achieved performance gains on most datasets in the few-shot learning tests.

Cross-dataset transfer

In the cross-dataset transfer experiment, we trained all categories in the ImageNet dataset using 16 images per class and then conducted zero-shot classification tests on 10 different target datasets to assess the model’s cross-dataset transfer capability. Table 3 compares CuTCP’s performance with other methods in cross-dataset transfer.

Table 3.

Cross-dataset transfer evaluation.

| Dataset | CLIP | CoOp | KgCoOp | TCP | CuTCP | ∆ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ImageNet | 66.73 | 71.51 | 71.20 | 71.40 | 72.57 | + 1.17 |

| Caltech101 | 93.30 | 93.70 | 93.92 | 93.97 | 94.43 | + 0.46 |

| OxfordPets | 89.10 | 89.14 | 89.83 | 91.25 | 90.67 | -0.58 |

| StanfordCars | 65.70 | 64.51 | 65.41 | 64.69 | 65.33 | + 0.64 |

| Flowers102 | 70.70 | 68.71 | 70.01 | 71.21 | 71.63 | + 0.42 |

| Food101 | 85.90 | 85.30 | 86.36 | 86.69 | 86.53 | -0.16 |

| FGVCAircraft | 24.90 | 18.47 | 22.51 | 23.45 | 24.13 | + 0.68 |

| SUN397 | 62.60 | 64.15 | 66.16 | 67.15 | 67.13 | -0.02 |

| DTD | 44.30 | 41.92 | 46.35 | 44.35 | 44.90 | + 0.55 |

| EuroSAT | 48.30 | 46.39 | 46.04 | 51.45 | 50.70 | -0.75 |

| UCF101 | 67.60 | 66.55 | 68.50 | 68.73 | 68.33 | -0.40 |

| Avg | 65.24 | 63.88 | 65.51 | 66.29 | 66.38 | + 0.09 |

Trained on ImageNet with 16 images per class, comparing cross-dataset transfer performance on 10 target datasets with other methods. Avg indicates the average performance across 10 target datasets.

As shown in Table 3, CuTCP outperforms TCP on 5 datasets, with substantial improvements in StanfordCars, FGVCAircraft, and DTD. However, CuTCP’s performance showed a notable decline on the EuroSAT dataset. Importantly, CuTCP achieved a 1.17% improvement on the source dataset, ImageNet, suggesting that custom prompts assist the model in better distinguishing category features within the source dataset. However, cross-dataset transferability appears to depend on the degree of similarity in feature knowledge shared between source and target datasets, as illustrated by CuTCP’s performance on the satellite remote sensing dataset, EuroSAT.

Domain generalization

In the domain generalization experiment, the model was also trained on the ImageNet dataset with 16 images per class, and tested on four ImageNet variant datasets with the same categories but different domain distributions. Table 4 shows the performance comparison of CuTCP and other methods in domain generalization.

Table 4.

Domain generalization evaluation.

| Dataset | CLIP | CoOp | KgCoOp | TCP | CuTCP | ∆ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ImageNet | 66.73 | 71.51 | 71.20 | 71.40 | 72.57 | + 1.17 |

| ImageNet-V2 | 60.83 | 64.20 | 64.10 | 64.60 | 65.43 | + 0.83 |

| ImageNet-Sketch | 46.15 | 47.99 | 48.97 | 49.50 | 49.53 | + 0.03 |

| ImageNet-A | 47.77 | 49.71 | 50.69 | 51.20 | 51.23 | + 0.03 |

| ImageNet-R | 73.96 | 75.21 | 76.70 | 76.73 | 77.33 | + 0.60 |

| Avg | 57.17 | 59.28 | 60.11 | 60.51 | 60.88 | + 0.37 |

Trained on ImageNet with 16 images per class, comparing domain generalization performance across four ImageNet variant datasets. Avg indicates the average performance across 4 variant datasets.

As shown in the Table 4, CuTCP achieved an improvement of 0.83% on ImageNet-V2 and 0.60% on ImageNet-R compared to TCP, with an average improvement of 0.37% across the four datasets. These results indicate that CuTCP can better capture the common features of the same categories across different domain shifts through customized prompts. However, CuTCP’s improvement on the ImageNet-Sketch and ImageNet-A datasets was limited, likely because ImageNet-Sketch consists of hand-drawn images, and ImageNet-A contains images with noise, occlusions, or extreme angles.

Ablation study

Impact of generative custom prompts vs. prompt templates

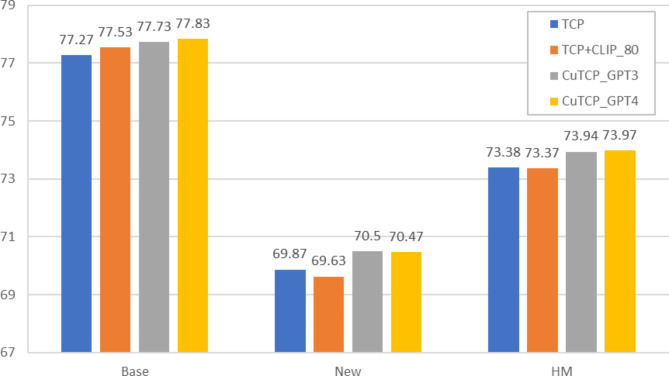

Figure 2 presents the effects of using various prompt templates for generalization from base to new classes in the ImageNet dataset. Compared to TCP with a single fixed template, TCP using 80 CLIP-provided prompt templates improved performance by 0.26% on base classes but decreased it by 0.24% on new classes. In contrast, CuTCP achieved notable gains on both base and new classes, with a 0.63% increase on new classes. This suggests that custom prompts, offering more nuanced category descriptions, improve the model’s generalization capacity over fixed templates. We generated custom prompts for the ImageNet dataset using GPT-4o-mini with the same parameter settings. As shown in the Fig. 2, compared to GPT-3, GPT-4 did not significantly improve performance. This limited enhancement may be due to the use of identical query templates, which resulted in similar semantic information across the generated prompts. As a result, the advanced capabilities of the more advanced LLMs were not fully leveraged, leading to minimal gains in model performance. Thus, for more advanced LLMs, we should further attempt to formulate new prompt generation strategies.

Fig. 2.

Effects of various prompt templates on generalization from base to new classes in the ImageNet dataset.

Impact of prompt length

Figure 3 illustrates the effect of the learnable prompt length (M) on model performance. With longer prompt lengths, base class performance improves while new class performance declines. This trend may be due to longer prompts capturing richer semantic information, enhancing the model’s adaptation to base classes and custom prompts but shifting the learned knowledge towards base classes. The narrow 0.21% gap between the highest and lowest HM values supports TCP’s claim that prompt length minimally affects the TKE module.

Fig. 3.

Effects of different prompt lengths on generalization from base to new classes.

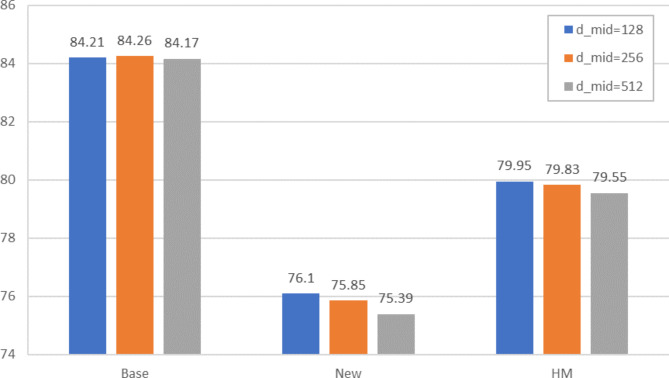

Impact of intermediate layer dimensions

Figure 4 evaluates the effect of varying the intermediate layer dimension on model performance. Consistent with TCP findings, CuTCP performs optimally at =128. Larger dimensions show minimal effect on base class performance but significantly impact new class accuracy, indicating that smaller values more effectively compress prior knowledge in prompt features, enhancing learning of essential information, while larger values may introduce redundant data, reducing new class performance.

Fig. 4.

Effects of different  dimensions on generalization from base to new classes.

dimensions on generalization from base to new classes.

Visualization analysis

We visualized Euclidean distances between image features and category text features for base and new classes in the EuroSAT and OxfordPets datasets. As shown in Fig. 5, each color cluster represents a class, tighter clusters indicate better internal consistency, while clearer boundaries between clusters reflect stronger differentiation. CuTCP’s distance distributions are more concentrated for both base and new classes, with clearer boundaries between categories. These findings further confirm CuTCP’s advantage in enhancing generalization performance through custom prompts.

Fig. 5.

Visualization of Euclidean distances between image features and corresponding category text features in TCP and CuTCP on EuroSAT and OxfordPets datasets.

Training efficiency

During CuTCP training, only a one-time calculation of average features across all custom prompts is needed during model initialization, with no additional computational overhead relative to TCP. Table 5 details the computational costs of custom prompts across different dataset scales. As shown in the table, the computational cost of custom prompts increases linearly with the number of prompts. Nevertheless, this cost remains minimal compared to the overall resource consumption during the training process and is nearly negligible.

Table 5.

Computational cost of prompts.

| FGVCAircraft | SUN397 | ImageNet | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Classes | 100 | 397 | 1,000 |

| Queries | 2 | 3 | 5 |

| Prompts | 2,000 | 11,910 | 50,000 |

| Maximum Tokens | 100,000 | 595,500 | 2,500,000 |

| GFLOPs |

|

|

|

| Time | 0.65s | 2.78s | 8.76s |

Floating-point calculations and total computation time required for using custom prompts on three datasets of varying scales.

Discussion

In this paper, we present CuTCP, an enhanced approach based on TCP that uses large language models to generate custom prompts. By embedding richer semantic information through these custom prompts, CuTCP enables the model to better recognize fine-grained category distinctions, effectively addresses the limitations associated with generic prompt templates. The experimental results demonstrate that CuTCP achieves an average accuracy gain of 0.74% on novel classes and 0.44% increase in the harmonic mean across 11 datasets. This improvement is particularly notable in tasks requiring fine-grained image feature descriptions, such as the FGVCAircraft, DTD, and EuroSAT datasets, where accuracy on new classes increased by 1.33–2.40%.

While CuTCP exhibits performance gains on most datasets, using custom prompts in datasets with pronounced feature differences can lead to information redundancy, potentially hindering the model’s ability to fully utilize embedded prior knowledge. In datasets such as StanfordCars, EuroSAT, and UCF101, accuracy on base classes decreased by 0.26–0.76%, while improvements on datasets like ImageNet-Sketch were relatively modest. To address these challenges, lowering the temperature parameter in LLMs is a promising approach to explore. By enhancing the certainty of generated content, it can improve the relevance and consistency of prompts. Additionally, introducing a filtering mechanism to screen prompt features for semantic relevance helps retain information closely aligned with the target classes while avoiding irrelevant or redundant content. Future work will integrate more advanced LLMs to generate refined prompts, enhancing adaptability to complex classes. Efforts will also focus on improving the TKE module to better utilize semantic information within prompts. Additionally, fine-tuning the visual branch will be explored to better align it with the prompt features in the text branch, further enhancing the model’s generalization across diverse tasks.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Author contributions

M. H.: Research design, methodology, feasibility analysis; C. Y.: Investigation, research design, writing—the manuscript; X. Y.: Data curation, Investigation, writing—the manuscript. All authors discussed and reviewed the manuscript.

Data availability

This research is based on the CoOp codebase provided by Kaiyang Zhou’s team (https://github.com/KaiyangZhou/CoOp). The relevant datasets can be obtained through the following documentation (https://github.com/KaiyangZhou/CoOp/blob/main/DATASETS.md).

Declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Radford, A. et al. Learning transferable visual models from natural language supervision. In International conference on machine learning. PMLR, 8748–8763 (2021).

- 2.Jia, C. et al. Scaling up visual and vision-language representation learning with noisy text supervision. Int. Conf. Mach. Learn. PMLR, 4904–4916 (2021). [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zhou, K., Yang, J., Loy, C. C. & Liu, Z. Learning to prompt for vision-language models. Int. J. Comput. Vision130(9), 2337–2348 (2022). [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yao, H., Zhang, R. & Xu, C. T. C. P. Textual-based Class-aware Prompt tuning for Visual-Language Model. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, 23438–23448 (2024).

- 5.Bahng, H., Jahanian, A., Sankaranarayanan, S. & Isola, P. Exploring visual prompts for adapting large-scale models. arXiv preprint arXiv:2203.17274 (2022).

- 6.Dosovitskiy, A. An image is worth 16x16 words: Transformers for image recognition at scale. arXiv preprint arXiv:11929 (2020). (2010).

- 7.Jia, M. et al. Visual prompt tuning. In European Conference on Computer Vision, 709–727 (2022).

- 8.Zhou, K., Yang, J., Loy, C. C. & Liu, Z. Conditional prompt learning for vision-language models. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF conference on computer vision and pattern recognition, 16816–16825 (2022).

- 9.Yao, H., Zhang, R. & Xu, C. Visual-language prompt tuning with knowledge-guided context optimization. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF conference on computer vision and pattern recognition, 6757–6767 (2023).

- 10.Khattak, M. U. et al. Maple: Multi-modal prompt learning. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, 19113–19122 (2023).

- 11.Khattak, M. U. et al. Self-regulating prompts: Foundational model adaptation without forgetting. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision, 15190–15200 (2023).

- 12.Pratt, S., Covert, I., Liu, R. & Farhadi, A. What does a platypus look like? generating customized prompts for zero-shot image classification. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision, 15691–15701 (2023).

- 13.Menon, S. & Vondrick, C. Visual classification via description from large language models. arXiv preprint arXiv:2210.07183 (2022).

- 14.Novack, Z., McAuley, J., Lipton, Z. C., Garg, S. & Chils Zero-shot image classification with hierarchical label sets. In International Conference on Machine Learning. PMLR. 26342–26362 (2023).

- 15.Vaswani, A. Attention is all you need. Adv. Neural. Inf. Process. Syst. (2017).

- 16.He, K., Zhang, X., Ren, S. & Sun, J. Deep residual learning for image recognition. In Proceedings of the IEEE conference on computer vision and pattern recognition, 770–778 (2016).

- 17.Brown, T. B. Language models are few-shot learners. arXiv preprint arXiv:14165 (2020). (2005).

- 18.Deng, J. et al. Imagenet: A large-scale hierarchical image database. In 2009 IEEE conference on computer vision and pattern recognition, 248–255 (2009).

- 19.Fei-Fei, L., Fergus, R. & Perona, P. Learning generative visual models from few training examples: An incremental bayesian approach tested on 101 object categories. In 2004 conference on computer vision and pattern recognition workshop, pp. 178–178 (2004).

- 20.Parkhi, O. M., Vedaldi, A., Zisserman, A. & Jawahar, C. V. Cats and dogs. In 2012 IEEE conference on computer vision and pattern recognition, 3498–3505 (2012).

- 21.Krause, J., Stark, M., Deng, J. & Fei-Fei, L. 3d object representations for fine-grained categorization. In Proceedings of the IEEE international conference on computer vision workshops, 554–561 (2013).

- 22.Nilsback, M. E. & Zisserman, A. Automated flower classification over a large number of classes. In 2008 Sixth Indian conference on computer vision, 722–729 (2008).

- 23.Bossard, L., Guillaumin, M. & Van Gool, L. Food-101–mining discriminative components with random forests. In Computer vision–ECCV 2014: 13th European conference, 446–461 (2014).

- 24.Maji, S., Rahtu, E., Kannala, J., Blaschko, M. & Vedaldi, A. Fine-grained visual classification of aircraft. arXiv preprint arXiv:1306.5151 (2013).

- 25.Xiao, J., Hays, J., Ehinger, K. A., Oliva, A. & Torralba, A. Sun database: Large-scale scene recognition from abbey to zoo. In 2010 IEEE computer society conference on computer vision and pattern recognition, 3485–3492 (2010).

- 26.Soomro, K. UCF101: A dataset of 101 human actions classes from videos in the wild. arXiv preprint arXiv:1212.0402 (2012).

- 27.Cimpoi, M., Maji, S., Kokkinos, I., Mohamed, S. & Vedaldi, A. Describing textures in the wild. In Proceedings of the IEEE conference on computer vision and pattern recognition, 3606–3613 (2014).

- 28.Helber, P., Bischke, B., Dengel, A., Borth, D. & Eurosat A novel dataset and deep learning benchmark for land use and land cover classification. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Appl. Earth Observations Remote Sens.12(7), 2217–2226 (2019). [Google Scholar]

- 29.Recht, B., Roelofs, R., Schmidt, L. & Shankar, V. Do imagenet classifiers generalize to imagenet? In International conference on machine learning. PMLR. 5389–5400 (2019).

- 30.Wang, H., Ge, S., Lipton, Z. & Xing, E. P. Learning robust global representations by penalizing local predictive power. Advances. in Neural Inform. Process. Syst., 32 (2019).

- 31.Hendrycks, D., Zhao, K., Basart, S., Steinhardt, J. & Song, D. Natural adversarial examples. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF conference on computer vision and pattern recognition, 15262–15271 (2021).

- 32.Hendrycks, D. et al. The many faces of robustness: A critical analysis of out-of-distribution generalization. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF international conference on computer vision, 8340–8349 (2021).

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

This research is based on the CoOp codebase provided by Kaiyang Zhou’s team (https://github.com/KaiyangZhou/CoOp). The relevant datasets can be obtained through the following documentation (https://github.com/KaiyangZhou/CoOp/blob/main/DATASETS.md).