Abstract

Background

Metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease (MASLD) is the most prevalent chronic liver disease and can affect individuals without producing any symptoms. We aimed to explore the value of serum sirtuin-1 (Sirt-1) in the diagnosis of MASLD.

Methods

This case-control study analyzed data collected from 190 individuals aged 20 to 60 years. Anthropometric parameters, demographic information, and serum biochemical variables—including glycemic parameters, lipid profiles, liver enzymes, and Sirt-1 levels—were assessed. The correlation between serum Sirt-1 and biochemical variables was examined using Pearson’s correlation coefficient. Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve analysis was employed to evaluate the diagnostic value of serum Sirt-1 in the context of MASLD.

Results

Serum Sirt-1 levels was significantly lower in the MASLD group (p < 0.001) and was inversely correlated with serum insulin (r = -0.163, p = 0.025), HOMA-IR (r = -0.169, p = 0.020) and triglyceride (r = -0.190, p = 0.009) and positively correlated with serum levels of high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-C) (r = 0.214, p = 0.003). The area under the curve (AUC) of Sirt-1 to predict the presence of MASLD was 0.76 (p < 0.001, 95% CI: 0.69, 0.82) with a sensitivity of 78.9, specificity of 61.1, positive predictive value (PPV) of 67.0%, and negative predictive value (NPV) of 74.0%. The optimal cutoff, determined using Youden’s index, was 23.75 ng/mL. This indicates that serum Sirt-1 levels below 23.75 ng/mL may be indicative of MASLD.

Conclusions

The present study demonstrated that serum Sirt-1 levels were significantly lower in patients with MASLD. Furthermore, these levels were correlated with various metabolic parameters, including insulin resistance and the serum lipid profile. A serum Sirt-1 level below the cutoff of 23.75 ng/mL exhibited a significant association with the presence of MASLD, suggesting its potential utility in identifying patients with this condition.

Keywords: Metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease, Sirtuin 1, Diagnostic biomarker, Case-control

Introduction

Metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease (MASLD) encompasses a spectrum of liver disorders characterized by the excessive accumulation of fat in the liver, known as steatosis. This condition can begin as simple steatosis and may progress to metabolic dysfunction-associated steatohepatitis (MASH), which is marked by inflammation, liver fibrosis, cirrhosis, and ultimately, advanced liver failure or liver carcinoma [1–4]. MASLD is the most prevalent chronic liver disease globally, impacting 30–40% of the U.S. population, 20–44% of the European population, and 29.6% of the Asian population [5, 6]. In Iran, the prevalence of MASLD among adults is 36.9% [7].

Diagnosis and identification of disease causes and pathological mechanisms are essential for disease prevention and treatment. Lifestyle interventions, including calorie restriction, dietary modifications, and increased physical activity, have proven to be highly effective in preventing and treating MASLD [8, 9]. Caloric restriction and weight loss lead to a reduction in body fat tissue and an improvement in metabolic risk factors, including triglyceride levels, low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C), glucose, insulin, inflammatory markers, and blood pressure. The molecular mechanisms by which caloric restriction affects metabolic parameters are not yet fully understood [10]. Research suggests that decreasing calorie intake may enhance the activity of Sirtuin enzymes [10]. Sirtuins are nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NAD+)-dependent deacetylases that function as energy sensors within the cell. An increase in the ratio of cellular NAD+/NADH, which occurs when the cell experiences a loss of energy, enhances Sirtuin activity [11]. In mammals, seven types of Sirtuins, numbered from 1 to 7, have been identified. Among these, Sirtuin 1 (Sirt-1) has been extensively studied in relation to metabolic processes that regulate glucose homeostasis, lipid metabolism, oxidative stress, insulin secretion and sensitivity, inflammation, cellular aging, and apoptosis [12]. Under conditions of calorie restriction, the activity and levels of Sirtuin 1 (Sirt-1) increase in both animal and human tissues [13, 14]. In animal models, enhanced Sirt-1 activity has been linked to a reduction in the expression of lipogenic genes, including sterol regulatory element-binding protein 1c (SREBP-1c), acetyl-CoA carboxylase (ACC), and fatty acid synthase (FAS). This decrease led reduction results in in lower profile and fat and decreased in the liver. Additionally, there was a decrease in the expression of genes associated with oxidative stress, an increase in antioxidant enzyme levels, inhibition of nuclear factor kappa B (NFκB) activity, and a reduction in the production of inflammatory cytokines. Conversely, the decreased expression of the Sirt-1 gene and its serum levels were linked to an increase in the expression of lipogenic genes, obesity, insulin resistance, elevated lipid and cholesterol levels, as well as heightened inflammation and oxidative stress [15]. Another study reported a decrease in the expression of Sirt-1 and reduced plasma levels in individuals with MASLD, which is associated with a greater degree of hepatic steatosis [16]. Animal models have shown that the deletion of the liver Sirt-1 gene may be linked to insulin resistance, elevated lipid and cholesterol levels, liver steatosis, inflammation, and oxidative stress [17–20].

Therefore, given the subtle nature of MASLD and the significant functions and roles of Sirt-1 in liver metabolism, as well as other metabolic pathways involved in the pathogenesis of MASLD, this study was designed to assess the diagnostic value of serum Sirt-1 in MASLD through a case-control study.

Methods

Study samples

This case-control study was conducted on subjects aged 20 to 60 years with a body mass index (BMI) ranging from 25 to 35 kg/m² who attended the Golgasht outpatient polyclinic affiliated with Tabriz University of Medical Sciences in Iran. The minimum required sample size for this study was determined based on preliminary data obtained from the research conducted by Abdelnabi et al. [21]., which focused on serum Sirt-1 levels as a key variable. Considering a 5% Type I error rate, a study power of 90%, and a control-to-case ratio of 1:1, the minimum required sample size was calculated to be 95 subjects in each group.

The case group comprised 95 consecutive patients diagnosed with MASLD by a gastroenterologist. Ultrasonography was employed for both the diagnosis and assessment of MASLD severity. The grading of liver echogenicity was conducted in accordance with the methodology established by van Werven et al. [22]. All procedures were performed by a single expert sonographer using a SonoAce X4 ultrasound system (South Korea).

Patients in the case group who met the following criteria were excluded: long-term dietary modifications, weight loss, or specific illnesses; a history of hepatobiliary disease other than MASLD; hepatitis B and C; renal dysfunction; diabetes; cancer; thyroid disorders; cardiovascular disease; gastrointestinal disorders; and autoimmune diseases. Additionally, pregnant and lactating women, individuals with recent clinical inflammatory or infectious conditions, those taking antioxidant supplements within three months prior to enrollment, and individuals who consumed excessive alcohol or smoked were also excluded.

The control group comprised 95 subjects without a history of MASLD, who were recruited from various outpatient departments, including dermatology and ophthalmology. The inclusion criteria for the control group were established based on liver ultrasonography, which confirmed that they did not suffer from any stage of liver steatosis. Control subjects were matched with cases based on sex, age (± 2 years), and BMI (± 1 kg/m2).

The exclusion criteria for control participants included the presence of any hepatobiliary disease, kidney dysfunction, gastrointestinal disorders, cardiovascular diseases, malignancies, thyroid disorders, pregnancy or lactation, and adherence to special diets. Additionally, individuals who had taken any antioxidant supplements within three months prior to enrollment in the study, as well as those who consumed alcohol or smoked, were not eligible.

All study participants were interviewed by trained staff. A questionnaire administered by the interviewer was utilized to collect relevant demographic information. All participants were informed of the study’s objectives, and written informed consent was obtained from each individual. The study was conducted in accordance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki and received approval from the ethics committee of Tehran University of Medical Sciences (Ethics code number: IR.TUMS.MEDICINE.REC.1402.630).

Anthropometric and biochemical assessment

The participant’s weight was measured while wearing the fewest clothing items possible, using an electronic weighing scale. Their height was recorded in an upright position with a fixed wall scale. BMI was calculated by dividing weight (kg) by height squared (m2). Waist circumference (WC) was measured with an unstretched tape measure, accurate to 0.1 cm. To minimize errors, all measuring instruments were calibrated before each measurement.

After a 10 to 12-hour overnight fast, 10 mL of venous blood was collected from the brachial vein of eligible participants to evaluate serum levels of various biochemical variables. Following clotting at room temperature, the blood samples were centrifuged at 3500 rpm (~ 2000 g) for 10 min to separate the serum. The samples were then stored immediately at − 80 °C. Fasting serum glucose (FSG), as well as serum levels of total cholesterol (TC), triglycerides (TG), high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-C), and low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C), were assessed using a standard enzymatic colorimetric technique on an automatic biochemical analyzer (Hitachi 717, Hitachi Ltd., Tokyo, Japan) with commercial kits (Pars-Azmoon, Iran). Serum insulin levels were measured using an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) kit (DiaMetra, Milano, Italy) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Insulin resistance was estimated using the homeostasis model assessment method (HOMA-IR) with the following equation: HOMA-IR = [fasting insulin (U/L) × fasting glucose (mg/dL)]/405.

Serum levels of alanine aminotransferase (ALT), aspartate aminotransferase (AST), and gamma-glutamyl transferase (GGT) were evaluated using commercially available enzymatic reagents (Pars Azmoon, Tehran, Iran) with an autoanalyzer (Alcyon 300, USA). Serum Sirt-1 levels were measured using relevant enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) kits (Crystal Day Bio-Tec, Shanghai, China).

Statistical analyses

The analyses were conducted using STATA software (version 13.0; Stata Corp.), with P-values less than 0.05 considered indicative of statistical significance. Quantitative variables were reported as means ± standard deviation (SD), while qualitative variables were expressed as frequencies (percentages). The normality of the data was assessed using the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test and histogram charts. Non-normally distributed data were presented as medians and interquartile ranges (IQR). General and biochemical characteristics were compared between groups using independent samples t-tests, Pearson chi-squared tests, or Mann–Whitney U-tests, as appropriate. Correlations between serum Sirt-1 and biochemical variables were examined using the Pearson correlation coefficient. To evaluate the predictive value of serum Sirt-1, we calculated receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves, including area under the curve (AUC) data, sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value (PPV), negative predictive value (NPV), positive likelihood ratio (PLR), negative likelihood ratio (NLR), and accuracy (ACC) using standard methods. Additionally, we determined an optimal cut-off for serum Sirt-1 levels to predict MASLD using Youden’s index.

Results

A total of 190 subjects were included in the final analysis, comprising 95 cases and 95 controls. Among the participants, there were 105 males (55.3%) and 85 females (44.7%). The mean age and BMI of the participants were 39.2 ± 6.4 years and 31.7 ± 3.6 kg/m², respectively.

Table 1 shows the general and biochemical characteristics of the participants. No noticeable difference was found in the mean age, anthropometric variables, FSG, TC, LDL-C and AST values and also the distribution of participants regarding sex between cases and controls. The mean serum levels of insulin (p = 0.006), HOMA-IR (p = 0.007), TG (p = 0.024) and also the median serum levels of ALT (p < 0.001), and GGT (p = 0.003) were significantly higher in the patients with MASLD than healthy controls. Moreover, the patients with MASLD had significantly lower serum levels of HDL-C than healthy controls (p = 0.019). Regarding the disease severity distribution in the patients with MASLD, 33.7%, 34.7%, and 31.6% of them had liver steatosis grades of 1, 2 and 3, respectively.

Table 1.

General and biochemical characteristics of patients with MASLD (cases) and healthy controls

| Variables | Cases (n = 95) |

Controls (n = 95) |

P-value† |

|---|---|---|---|

| Male, n (%) | 55 (57.9) | 50 (52.6) | 0.466‡ |

| Age (years) | 39.8 ± 6.7 | 38.7 ± 6.2 | 0.250# |

| Weight (kg) | 88.5 ± 12.6 | 88.8 ± 11.7 | 0.893# |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 31.4 ± 3.9 | 32.0 ± 3.2 | 0.214# |

| WC (cm) | 103.4 ± 9.3 | 102.3 ± 9.3 | 0.437# |

| FSG (mg/dL) | 103.0 ± 15.0 | 100.8 ± 12.1 | 0.262# |

| Insulin (µU/mL) | 15.8 ± 9.1 | 12.3 ± 8.4 | 0.006# |

| HOMA-IR | 4.1 ± 2.5 | 3.1 ± 2.4 | 0.007# |

| TC (mg/dL) | 204.0 ± 37.9 | 196.3 ± 32.4 | 0.132# |

| TG (mg/dL) | 203.6 ± 91.6 | 176.8 ± 69.3 | 0.024# |

| LDL-c (mg/dL) | 127.5 ± 34.5 | 131.6 ± 14.8 | 0.389# |

| HDL-c (mg/dL) | 43.2 ± 12.6 | 46.8 ± 8.3 | 0.019# |

| ALT (IU/L) | 30 (21, 45) | 21 (16, 30) | < 0.001§ |

| AST (IU/L) | 26 (20, 34) | 24 (16, 35) | 0.171§ |

| GGT (IU/L) | 35 (23, 46) | 26 (18, 38) | 0.003§ |

| Liver steatosis grade, n (%) | |||

| Grade 1 | 32 (33.7) | ||

| Grade 2 | 33 (34.7) | ||

| Grade 3 | 30 (31.6) |

MASLD, metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease; BMI, body mass index; WC, waist circumference; FSG, fasting serum glucose; HOMA-IR, homeostasis model assessment of insulin resistance; TC, total cholesterol; TG, triglyceride; LDL-c, low-density lipoprotein cholesterol; HDL-c, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol; ALT, alanine aminotransferase; AST, aspartate aminotransferase; GGT, gamma glutamyl transferase

Data are shown as mean ± standard deviation for normally distributed data, median (25th and 75th percentiles) for data not normally distributed (i.e. ALT, AST and GGT) and frequency (percentage) for categorical variables

distributed data †p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant

‡Obtained from χ2 test

#Obtained from independent samples t-test

§Obtained from Mann–Whitney U test

There was a significant difference in serum Sirt-1 levels between the study groups and it was significantly lower in the MASLD group (18.4 ± 7.5 vs. 26.3 ± 8.8 ng/mL, p < 0.001) (Fig. 1). The Pearson’s correlation coefficients between serum Sirt-1 levels and biochemical parameters in the participants are exhibited in Table 2. The serum Sirt-1 levels were inversely correlated with serum insulin (r = -0.163, p = 0.025), HOMA-IR (r = -0.169, p = 0.020) and TG (r = -0.190, p = 0.009) and positively correlated with serum HDL-C levels (r = 0.214, p = 0.003).

Fig. 1.

Comparison of serum sirtuin-1 levels between healthy control and patients with MASLD (p < 0.001)

Table 2.

Correlations between serum Sirtuin-1 levels and biochemical parameters in the whole study samples (n = 190)

| r | p | |

|---|---|---|

| FSG (mg/dL) | -0.101 | 0.165 |

| Insulin (µU/mL) | -0.163 | 0.025* |

| HOMA-IR | -0.169 | 0.020* |

| TC (mg/dL) | -0.018 | 0.800 |

| TG (mg/dL) | -0.190 | 0.009* |

| LDL-c (mg/dL) | -0.006 | 0.939 |

| HDL-c (mg/dL) | 0.214 | 0.003* |

| ALT (IU/L) | -0.137 | 0.059 |

| AST (IU/L) | -0.078 | 0.284 |

| GGT (IU/L) | -0.065 | 0.375 |

FSG, fasting serum glucose; HOMA-IR, homeostasis model assessment of insulin resistance; TC, total cholesterol; TG, triglyceride; LDL-c, low-density lipoprotein cholesterol; HDL-c, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol; ALT, alanine aminotransferase; AST, aspartate aminotransferase; GGT, gamma glutamyl transferase

*p < 0.05 statistically significant

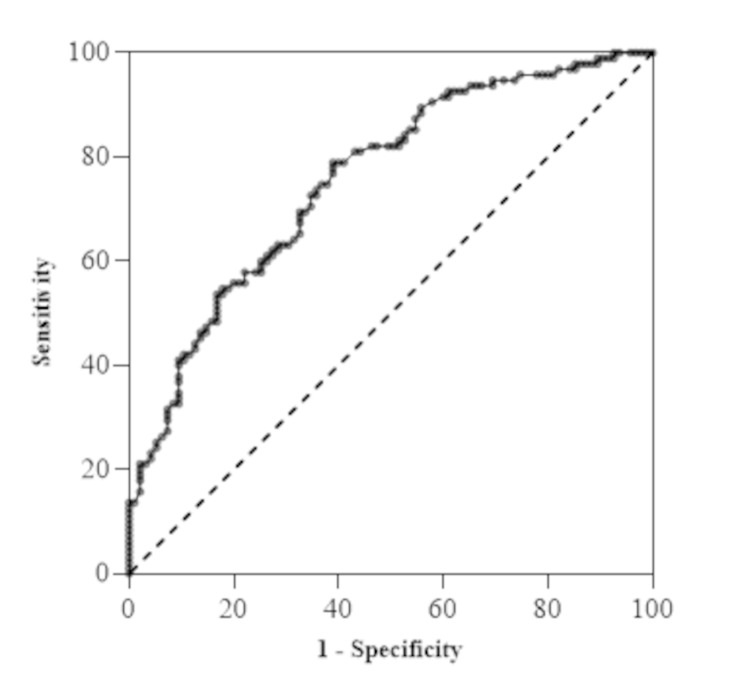

The area under the curve (AUC) of Sirt-1 to predict the presence of MASLD was 0.76 (p < 0.001, 95% CI: 0.69, 0.82) with a sensitivity of 78.9, specificity of 61.1, positive predictive value (PPV) of 67.0%, negative predictive value (NPV) of 74.0%, and accuracy (ACC) of 0.7 (Fig. 2; Table 3). The optimal cutoff, derived from Youden’s index, was 23.75 ng/mL, which indicates that serum Sirt-1 below 23.75 ng/mL predicts MASLD (Table 3).

Fig. 2.

Receiver operating characteristics (ROC) curve for prediction of MASLD. Significant area under the curve (0.76, p < 0.001) with a cutoff of < 23.75, sensitivity 78.9, specificity 61.1

Table 3.

Diagnostic values of serum sirtuin-1 levels in prediction of MASLD

| AUC (95%CI) | Cutoff value | Sensitivity (%) | Specificity (%) | PPV | NPV | PLR | NLR | ACC | Youden index |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.76 (0.69, 0.82) | 23.75 | 78.9 | 61.1 | 0.67 | 0.74 | 2.03 | 0.34 | 0.7 | 0.4 |

MASLD, metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease; AUC, area under curve; CI, confidence interval; PPV, positive predictive value; NPV, negative predictive value; PLR, positive likelihood ratio; NLR, negative likelihood ratio; ACC, accuracy

The association and agreement between serum Sirt-1 cutoff levels and the presence of MASLD are presented in Table 4. A significant association and agreement were observed between serum Sirt-1 levels (with a cutoff level of < 23.75 ng/mL) and the presence of MASLD (p < 0.001). Furthermore, the serum Sirt-1 level in patients with MASLD demonstrated a diagnostic accuracy of 70.0%, with a significant AUC (p < 0.001) at a cutoff value of less than 23.75 ng/mL.

Table 4.

Association and agreement between serum Sirtuin-1 cutoff levels and the presence of MASLD

| Sirt-1 cutoff | Study groups | Total | χ2 | p | Kappa agreement | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cases (n = 95) |

Controls (n = 95) |

||||||

| ≥ 23.75 (ng/mL) | |||||||

| n (%) | 20 (21.1) | 58 (61.1) | 78 (41.1) | 31.406 | < 0.001* | 0.400 | |

| < 23.75 (ng/mL) | |||||||

| n (%) | 75 (78.9) | 37 (38.9) | 112 (58.9) | ||||

MASLD, metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease

*p < 0.05 statistically significant (Obtained from χ2 test)

Discussion

MASLD has been recognized as the hepatic component of metabolic syndrome [23] because it shares common risk factors and is often associated with metabolic disorders such as obesity, diabetes mellitus, and dyslipidemia [24]. Early detection of patients with MASLD within the disease spectrum is crucial not only for effective management but also for preventing further progression to cirrhosis, hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC), and related complications.

In this study, we found that serum Sirt-1 levels in MASLD were significantly lower compared to those in the control group. Additionally, serum Sirt-1 levels were correlated with metabolic parameters in MASLD. Our findings have prompted us to evaluate Sirt-1 as a potential diagnostic biomarker for MASLD, which may have practical implications. Sirt-1 is a member of the sirtuin family and functions as a histone deacetylase. It is also recognized as a sensor of hunger, which is dependent on NAD+ [25]. Recent studies have demonstrated that Sirt-1 is closely associated with MASLD and plays a crucial role in regulating lipid metabolism, oxidative stress, and inflammation in the liver [26, 27]. Several investigations have explored potential therapeutic agents for MASLD concerning their ability to activate Sirt-1 [28–30].

We found that serum Sirt-1 levels in patients with MASLD ranged from 10.9 to 25.9 ng/mL, which is lower than those in the control group. This finding is consistent with the results reported by other researchers studying patients with MASLD [31]. Additionally, this study demonstrates that the area under the ROC curve for Sirt-1 is 0.76, indicating a relatively high sensitivity and specificity for diagnosing the presence of MASLD. This suggests that the diagnostic efficacy of Sirt-1 is substantial. The PPV of 67.0% indicates that, in this population, 67% of individuals with a positive test result actually have the disease. This suggests that Sirt-1 can serve as a relatively independent and clinically relevant evaluation index for the diagnosis of MASLD. We used Youden’s index to identify the optimal cutoff for serum Sirt-1 in diagnosing MASLD. Our findings indicated that a serum Sirt-1 level of less than 23.75 ng/mL demonstrated a diagnostic accuracy of 70.0% for MASLD. Therefore, Sirt-1 may serve as a novel serological marker for the diagnosis of MASLD.

Although there was no significant difference in the mean values of FSG, TC, LDL-C, and AST between the cases and controls, some metabolic markers exhibited differences between patients with MASLD and the control group. Consistent with previous studies [32–34], the findings of this study reinforce the well-established association between insulin resistance and MASLD, as patients with MASLD displayed elevated levels of serum insulin and HOMA-IR. Insulin resistance is a key feature of the pathogenesis of MASLD, as it leads to increased hepatic lipid accumulation and inflammation [35]. Furthermore, insulin levels and HOMA-IR exhibited a significant inverse correlation with serum Sirt-1, suggesting that Sirt-1 may exacerbate the disease. However, previous studies did not demonstrate any correlation between HOMA-IR and Sirt-1 in obese patients with hepatic fat infiltration [31]. Numerous mechanisms have been identified in this context. Increased Sirt-1 expression can inhibit hepatic steatosis by downregulating the expression of genes involved in fat synthesis [36, 37] and by activating fibroblast growth factor 21 (FGF21) [38–40], a hepatokine with metabolic regulatory properties during fasting and feeding [41]. Sirt-1 has also been shown to inhibit the activity of the mammalian target of rapamycin complex 1 (mTORC1), attenuate hepatic steatosis, and reduce endoplasmic reticulum stress [42]. All of these factors contribute to the reduction of hepatic steatosis and, consequently, to a decrease in insulin resistance. Decreased Sirt1 expression has been associated with muscle insulin resistance, in which mitochondrial dysfunction appears to play a role [43]. Conversely, Sirt-1 in adipose tissue has been shown to enhance insulin sensitivity through its anti-inflammatory effects [44, 45], as well as its deacetylase activity, which suppresses genes involved in insulin resistance [46]. Previous studies have identified a positive correlation between Sirt-1 and adiponectin expression in adipocytes, an important mediator of insulin sensitivity [47]. Lastly, Sirt-1 appears to play a crucial role in the function and survival of pancreatic beta cells that secrete insulin [48–52].

MASLD affects lipid metabolism in the liver through insulin resistance and alterations in the activity of enzymes that regulate lipid metabolism, leading to dysregulation of lipid homeostasis [53, 54]. Indeed, MASLD also leads to atherogenic dyslipidemia, characterized by elevated plasma TG and LDL-C levels, along with decreased HDL-C levels, which increases the risk of cardiovascular diseases [54]. Sirt-1 activates liver X receptors (LXRs), which regulate the transfer of cholesterol to the liver, thereby maintaining cholesterol homeostasis [55]. Furthermore, Sirt-1 may improve the lipid profile in patients with MASLD by enhancing insulin sensitivity through the aforementioned mechanisms. However, a well-established mechanism linking Sirt-1 to the serum lipid profile remains to be elucidated. Our study found that patients with MASLD exhibited higher TG levels and lower HDL-C levels, with no significant differences in TC and LDL-C compared to controls. Additionally, serum Sirt- levels were inversely correlated with serum TG levels and positively correlated with serum HDL-C levels. In contrast to our findings, a previous study conducted on obese patients with hepatic fat infiltration did not identify a significant correlation between serum Sirt-1 and any components of the lipid profile [31]. Further research is necessary to fully clarify the mechanisms underlying this association.

Among liver enzymes, ALT is closely associated with hepatic fat accumulation, liver dysfunction, and hepatic insulin resistance, functioning as a gluconeogenic enzyme [56]. GGT serves as a sensitive indicator of liver damage and may contribute to the development of MASLD through oxidative stress [57, 58]. The study also found that individuals with MASLD exhibited higher levels of ALT, and GGT. However, in the correlation analysis, Sirt-1 did not demonstrate any significant correlation with ALT or GGT. This supports previous findings by Mariani et al. [31]., which indicated that serum ALT levels were elevated in obese MASLD patients with severe hepatic steatosis compared to those with mild steatosis, while no significant correlation was observed between ALT and Sirt-1 [31]. This discrepancy can be explained by the findings of the study conducted by Verma et al.., which suggest that ALT is not a reliable marker for diagnosing MASLD [59]. Consequently, many patients with advanced liver disease may present with normal ALT levels, potentially leading to false reassurance and delays in the diagnosis of MASLD. Conversely, patients with elevated ALT levels may undergo unnecessary liver biopsies, which may only reveal mild steatosis [59].

This study was the first to investigate the diagnostic value of serum Sirt-1 in MASLD, providing a new basis for its detection in the diagnosis of MASLD. However, there are some limitations to this study. Due to the unavailability of data on the dietary energy intake of the participants, we were unable to make any adjustments based on this factor. Additionally, we did not assess the correlation between serum Sirt-1 levels and Sirt-1 protein or gene expression in liver tissue.

Conclusions

In conclusion, we found that serum Sirt-1 levels were lower in patients with MASLD. Additionally, these levels were correlated with various metabolic parameters, including insulin resistance and the serum lipid profile. Serum Sirt-1 levels below the cutoff of 23.75 ng/mL demonstrated a significant association and concordance with the presence of MASLD, exhibiting good sensitivity and specificity. This finding suggests that serum Sirt-1 levels could aid in the detection of patients with MASLD. However, further research involving larger patient populations is necessary to validate its potential as a biomarker.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank all the participants for their collaboration and the Research Vice-Chancellor of Tehran University of Medical Sciences for their financial support.

Abbreviations

- MASLD

Metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease

- MASH

Metabolic-dysfunction associated steatohepatitis

- Sirt-1

Sirtuin-1

- BMI

Body mass index

- PPV

Positive predictive value

- NPV

Negative predictive value

- ALT

Alanine aminotransferase

- AST

Aspartate aminotransferase

- GGT

Gamma glutamyl transferase

- LXRs

Liver X receptors

- NFκB

Nuclear factor kappa B

- NAD

Nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide

Author contributions

“F.A.” were involved in the study designing, interpretation of the data, and development of the manuscript.” M.T.” and “B.K.R.” wrote the main manuscript and coordinated in the data collection. “S.H.S.” performed the statistical analysis, and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. “S.A.” provided assistance in the design of the study, coordinated in prepared the manuscript, supervised data collection and edited the manuscript. All of the authors critically reviewed the manuscript and approved the final submitted draft of this manuscript.

Funding

This study was supported by Tehran University of Medical Sciences (TUMS). The funders had no involvement in study design; collection, analysis, and interpretation of data; in the writing of the report; and in the decision to submit the article for publication.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

All experiments were performed in accordance with the declaration of Helsinki and Tehran University of Medical Sciences ethical guidelines and regulations. The research protocol was approved by the Tehran University of Medical Sciences (ethics code number: IR.TUMS.MEDICINE.REC.1402.630). All participants signed a written inform consent before participating in the study.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Hashimoto E, Taniai M, Tokushige K. Characteristics and diagnosis of NAFLD/NASH. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2013;28:64–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Starley BQ, Calcagno CJ, Harrison SA. Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease and hepatocellular carcinoma: a weighty connection. Hepatology. 2010;51(5):1820–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Milić S, Štimac D. Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease/steatohepatitis: epidemiology, pathogenesis, clinical presentation and treatment. Dig Dis. 2012;30(2):158–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Aguilera-Méndez A. Nonalcoholic hepatic steatosis: a silent disease. Rev Med Inst Mex Seguro Soc. 2019;15(6):544–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Younossi Z, Anstee QM, Marietti M, Hardy T, Henry L, Eslam M, et al. Global burden of NAFLD and NASH: trends, predictions, risk factors and prevention. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2018;15(1):11–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Elizabeth LY, Golshan S, Harlow KE, Angeles JE, Durelle J, Goyal NP, et al. Prevalence of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease in children with obesity. J Pediatr. 2019;207:64–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hassanipour S, Amini-Salehi E, Joukar F, Khosousi M-J, Pourtaghi F, Ansar MM, et al. The prevalence of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease in Iranian children and adult population: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Iran J Public Health. 2023;52(8):1600–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cobbina E, Akhlaghi F. Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD)–pathogenesis, classification, and effect on drug metabolizing enzymes and transporters. Drug Metab Rev. 2017;49(2):197–211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Donnelly KL, Smith CI, Schwarzenberg SJ, Jessurun J, Boldt MD, Parks EJ. Sources of fatty acids stored in liver and secreted via lipoproteins in patients with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. J Clin Invest. 2005;115(5):1343–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Faghihzadeh F, Adibi P, Hekmatdoost A. The effects of resveratrol supplementation on cardiovascular risk factors in patients with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease: a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Br J Nutr. 2015;114(5):796–803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wang Y. Molecular links between caloric restriction and Sir2/SIRT1 activation. Diabetes Metab J. 2014;38(5):321–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Colak Y, Ozturk O, Senates E, Tuncer I, Yorulmaz E, Adali G, et al. SIRT1 as a potential therapeutic target for treatment of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Med Sci Monit. 2011;17(5):HY5–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chalkiadaki A, Guarente L. Metabolic signals regulate SIRT1 expression. EMBO Rep. 2011;12(10):985–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chang H-C, Guarente L. SIRT1 and other sirtuins in metabolism. Trends Endocrinol Metab. 2014;25(3):138–45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Noriega LG, Feige JN, Canto C, Yamamoto H, Yu J, Herman MA, et al. CREB and ChREBP oppositely regulate SIRT1 expression in response to energy availability. EMBO Rep. 2011;12(10):1069–76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yamagata K, Yoshizawa T. Transcriptional regulation of metabolism by SIRT1 and SIRT7. Int Rev Cell Mol Biol. 2018;335:143–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wu T, Liu Y-h, Fu Y-c, Liu X-m. Zhou X-h. Direct evidence of sirtuin downregulation in the liver of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease patients. Ann Clin Lab Sci. 2014;44(4):410–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rodgers JT, Puigserver P. Fasting-dependent glucose and lipid metabolic response through hepatic sirtuin 1. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104(31):12861–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Purushotham A, Schug TT, Xu Q, Surapureddi S, Guo X, Li X. Hepatocyte-specific deletion of SIRT1 alters fatty acid metabolism and results in hepatic steatosis and inflammation. Cell Metab. 2009;9(4):327–38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wang R-H, Li C, Deng C-X. Liver steatosis and increased ChREBP expression in mice carrying a liver specific SIRT1 null mutation under a normal feeding condition. Int J Biol Sci. 2010;6(7):682–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Abdelnabi A-SM, Esmayel IM, Hussein S, Ali RM, AbdelAal AA. Sirtuin-1 in Egyptian patients with coronary artery disease. Beni-Suef univ J Basic Appl Sci. 2021;10:1–7. [Google Scholar]

- 22.van Werven JR, Marsman HA, Nederveen AJ, Smits NJ, ten Kate FJ, van Gulik TM, et al. Assessment of hepatic steatosis in patients undergoing liver resection: comparison of US, CT, T1-weighted dual-echo MR imaging, and point-resolved 1H MR spectroscopy. Radiology. 2010;256(1):159–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Marchesini G, Brizi M, Bianchi G, Tomassetti S, Bugianesi E, Lenzi M, et al. Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: a feature of the metabolic syndrome. Diabetes. 2001;50(8):1844–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chalasani N, Younossi Z, Lavine JE, Charlton M, Cusi K, Rinella M, et al. The diagnosis and management of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: practice guidance from the American Association for the study of Liver diseases. Hepatology. 2018;67(1):328–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yang T, Fu M, Pestell R, Sauve AA. SIRT1 and endocrine signaling. Trends Endocrinol Metab. 2006;17(5):186–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.de Gregorio E, Colell A, Morales A, Marí M. Relevance of SIRT1-NF-κB axis as therapeutic target to ameliorate inflammation in liver disease. Int J Mol Sci. 2020;21(11):3858. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ding R-B, Bao J, Deng C-X. Emerging roles of SIRT1 in fatty liver diseases. Int J Biol Sci. 2017;13(7):852–67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Asghari S, Asghari-Jafarabadi M, Somi M-H, Ghavami S-M, Rafraf M. Comparison of calorie-restricted diet and resveratrol supplementation on anthropometric indices, metabolic parameters, and serum sirtuin-1 levels in patients with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: a randomized controlled clinical trial. Am Coll Nutr. 2018;37(3):223–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Daneshi-Maskooni M, Keshavarz SA, Qorbani M, Mansouri S, Alavian SM, Badri-Fariman M, et al. Green cardamom increases Sirtuin-1 and reduces inflammation in overweight or obese patients with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease: a double-blind randomized placebo-controlled clinical trial. Nutr Metab. 2018;15(1):1–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kalhori A, Rafraf M, Navekar R, Ghaffari A, Jafarabadi MA. Effect of turmeric supplementation on blood pressure and serum levels of sirtuin 1 and adiponectin in patients with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: a double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial. Prev Nutr Food Sci. 2022;27(1):37–44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mariani S, Fiore D, Basciani S, Persichetti A, Contini S, Lubrano C, et al. Plasma levels of SIRT1 associate with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease in obese patients. Endocrine. 2015;49:711–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Isokuortti E, Zhou Y, Peltonen M, Bugianesi E, Clement K, Bonnefont-Rousselot D, et al. Use of HOMA-IR to diagnose non-alcoholic fatty liver disease: a population-based and inter-laboratory study. Diabetologia. 2017;60:1873–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gutierrez-Buey G, Núñez-Córdoba JM, Llavero-Valero M, Gargallo J, Salvador J, Escalada J. Is HOMA-IR a potential screening test for non-alcoholic fatty liver disease in adults with type 2 diabetes? Eur J Intern Med. 2017;41:74–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Marchesini G, Brizi M, Morselli-Labate AM, Bianchi G, Bugianesi E, McCullough AJ, et al. Association of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease with insulin resistance. Am J Med. 1999;107(5):450–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Palma R, Pronio A, Romeo M, Scognamiglio F, Ventriglia L, Ormando VM, et al. The role of insulin resistance in fueling NAFLD pathogenesis: from molecular mechanisms to clinical implications. J Clin Med. 2022;11(13):3649. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ponugoti B, Kim D-H, Xiao Z, Smith Z, Miao J, Zang M, et al. SIRT1 deacetylates and inhibits SREBP-1 C activity in regulation of hepatic lipid metabolism. J Biol Chem. 2010;285(44):33959–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Yamazaki Y, Usui I, Kanatani Y, Matsuya Y, Tsuneyama K, Fujisaka S, et al. Treatment with SRT1720, a SIRT1 activator, ameliorates fatty liver with reduced expression of lipogenic enzymes in MSG mice. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2009;297(5):E1179–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Fisher FM, Chui PC, Nasser IA, Popov Y, Cunniff JC, Lundasen T, et al. Fibroblast growth factor 21 limits lipotoxicity by promoting hepatic fatty acid activation in mice on methionine and choline-deficient diets. Gastroenterology. 2014;147(5):1073–83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Li Y, Wong K, Giles A, Jiang J, Lee JW, Adams AC, et al. Hepatic SIRT1 attenuates hepatic steatosis and controls energy balance in mice by inducing fibroblast growth factor 21. Gastroenterology. 2014;146(2):539–49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Li Y, Wong K, Walsh K, Gao B, Zang M. Retinoic acid receptor β stimulates hepatic induction of fibroblast growth factor 21 to promote fatty acid oxidation and control whole-body energy homeostasis in mice. J Biol Chem. 2013;288(15):10490–504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Itoh N. FGF21 as a hepatokine, adipokine, and myokine in metabolism and diseases. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2014;5:107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Li Y, Xu S, Giles A, Nakamura K, Lee JW, Hou X, et al. Hepatic overexpression of SIRT1 in mice attenuates endoplasmic reticulum stress and insulin resistance in the liver. FASEB J. 2011;25(5):1664–79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hong J, Kim B-W, Choo H-J, Park J-J, Yi J-S, Yu D-M, et al. Mitochondrial complex I deficiency enhances skeletal myogenesis but impairs insulin signaling through SIRT1 inactivation. J Biol Chem. 2014;289(29):20012–25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Gillum MP, Kotas ME, Erion DM, Kursawe R, Chatterjee P, Nead KT, et al. SirT1 regulates adipose tissue inflammation. Diabetes. 2011;60(12):3235–45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Yoshizaki T, Milne JC, Imamura T, Schenk S, Sonoda N, Babendure JL, et al. SIRT1 exerts anti-inflammatory effects and improves insulin sensitivity in adipocytes. Mol Cell Biol. 2009;29(5):1363–74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Qiang L, Wang L, Kon N, Zhao W, Lee S, Zhang Y, et al. Brown remodeling of white adipose tissue by SirT1-dependent deacetylation of Pparγ. Cell. 2012;150(3):620–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Song YS, Lee SK, Jang YJ, Park HS, Kim J-H, Lee YJ, et al. Association between low SIRT1 expression in visceral and subcutaneous adipose tissues and metabolic abnormalities in women with obesity and type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2013;101(3):341–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.do Amaral MEC, Ueno M, Oliveira CA, Borsonello NC, Vanzela EC, Ribeiro RA, et al. Reduced expression of SIRT1 is associated with diminished glucose-induced insulin secretion in islets from calorie-restricted rats. J Nutr Biochem. 2011;22(6):554–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Luu L, Dai F, Prentice K, Huang X, Hardy A, Hansen J, et al. The loss of Sirt1 in mouse pancreatic beta cells impairs insulin secretion by disrupting glucose sensing. Diabetologia. 2013;56:2010–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Moynihan KA, Grimm AA, Plueger MM, Bernal-Mizrachi E, Ford E, Cras-Méneur C, et al. Increased dosage of mammalian Sir2 in pancreatic β cells enhances glucose-stimulated insulin secretion in mice. Cell Metab. 2005;2(2):105–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ramachandran D, Roy U, Garg S, Ghosh S, Pathak S, Kolthur-Seetharam U. Sirt1 and mir‐9 expression is regulated during glucose‐stimulated insulin secretion in pancreatic β‐islets. FEBS J. 2011;278(7):1167–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Ramsey KM, Mills KF, Satoh A, Imai, Si. Age-associated loss of Sirt1‐mediated enhancement of glucose‐stimulated insulin secretion in beta cell‐specific Sirt1‐overexpressing (BESTO) mice. Aging Cell. 2008;7(1):78–88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Bechmann LP, Hannivoort RA, Gerken G, Hotamisligil GS, Trauner M, Canbay A. The interaction of hepatic lipid and glucose metabolism in liver diseases. J Hepatol. 2012;56(4):952–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Deprince A, Haas JT, Staels B. Dysregulated lipid metabolism links NAFLD to cardiovascular disease. Mol Metab. 2020;42:101092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Li X, Zhang S, Blander G, Jeanette GT, Krieger M, Guarente L. SIRT1 deacetylates and positively regulates the nuclear receptor LXR. Mol Cell. 2007;28(1):91–106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Vozarova B, Stefan N, Lindsay RS, Saremi A, Pratley RE, Bogardus C, et al. High alanine aminotransferase is associated with decreased hepatic insulin sensitivity and predicts the development of type 2 diabetes. Diabetes. 2002;51(6):1889–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Loomba R, Doycheva I, Bettencourt R, Cohen B, Wassel CL, Brenner D, et al. Serum γ-glutamyltranspeptidase predicts all-cause, cardiovascular and liver mortality in older adults. J Clin Exp Hepatol. 2013;3(1):4–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Whitfield JB. Gamma Glutamyl transferase. Crit Rev Clin Lab Sci. 2001;38(4):263–355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Verma S, Jensen D, Hart J, Mohanty SR. Predictive value of ALT levels for non-alcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH) and advanced fibrosis in non‐alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD). Liver Int. 2013;33(9):1398–405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.