Abstract

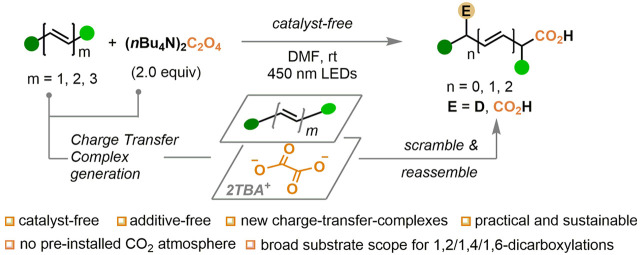

Herein, we report a visible-light-induced charge-transfer-complex-enabled dicarboxylation and deuterocarboxylation of C=C bonds with oxalate as a masked CO2 source under catalyst-free conditions. In this reaction, we disclosed the first example that the tetrabutylammonium oxalate could be able to aggregate with aryl substrates via π–cation interactions to form the charge transfer complexes, which subsequently triggers the single electron transfer from the oxalic dianion to the ammonium countercation under irradiation of 450 nm bule LEDs, releasing CO2 and CO2 radical anions. Diverse alkenes, dienes, trienes, and indoles, including challenging trisubstituted olefins, underwent dicarboxylation and anti-Markovnikov deuterocarboxylation with high selectivity to access valuable 1,2- and 1,4-dicarboxylic acids as well as indoline-derived diacids and β-deuterocarboxylic acids under mild conditions. The in situ generated CO2•– and CO2 molecules from oxalic radical anions could both add to the C=C bond without assistance of any photocatalyst or additives, which made this reaction sustainable, clean, and efficient.

Short abstract

Tetrabutylammonium oxalate (TBAO) works as a carboxylation reagent for 1,2-, 1,4-, and 1,6-difunctionalization of alkene, diene, and triene substrates in the absence of photocatalyst or any additives.

The solar-driven photocatalytic carbon dioxide (CO2) reduction reaction has gained significant attention due to its dual capability to generate high-value fuels while mitigating CO2 pollution.1,2 In organic chemistry fundamental research and the medicine industry, CO2 was widely used as the carbonyl (C1) synthon for alkene dicarboxylation under photocatalytic or electrocatalytic conditions3−11 to forge thermodynamically and kinetically stable C—C bonds, producing value-added dicarboxylic acids (Figure 1).12−14 Since the 1990s, electrocatalysis for alkene dicarboxylation with CO2 was first reported by Duñach and co-workers15 and then developed by several groups employing a sacrificial anode system.16−21 The deep reduction potential generated on the cathode usually caused poor functional group tolerance and therefore limited its applications in organic synthesis (Scheme 1a).22 Recently, photoredox catalysis has emerged as a sustainable alternative to generate highly reductive systems with an exogenous electron donor allowing access to more energy demanding substrates.23−25 In 2021, Yu and co-workers disclosed an elegant reductive photocatalytic system for alkene dicarboxylation with CO2 as the carbonyl source and DIPEA (N,N-diisopropylethylamine) as the electron donor (Scheme 1b).26 In these reactions, excess amounts of CO2 (1 atm of atmosphere, hard to quantify) as the carbonyl source were necessary. The requirement of either sacrificial anodes or stoichiometric electron donors leaves space for improvement of such transformations. A catalyst-free strategy to access diacids from alkenes is still under developed.

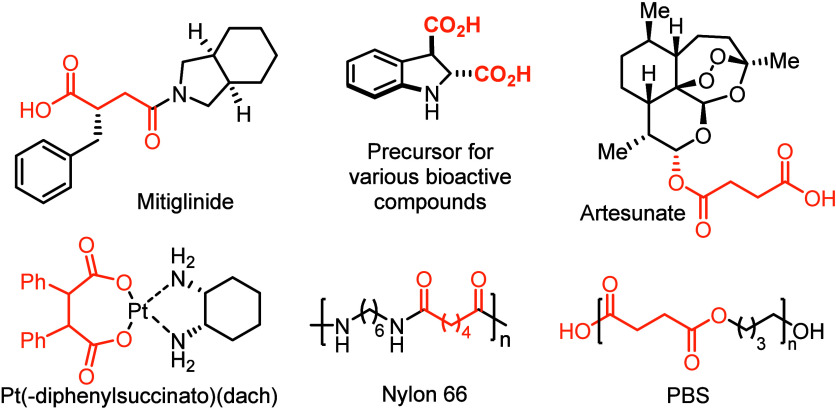

Figure 1.

Representative pharmaceutical drug molecules, synthetic intermediates, and polymers containing 1,2-, 1,4-, or 1,6-dicarboxylic backbones.

Scheme 1. (a) Electrocatalysis and (b) Photocatalysis to Access Diacids from Alkenes with CO2 As the C1 Source, (c) the Model of CO2 Radical Anion Generation, and (d) Photoinduced Additive-Free Protocol with Oxalate (This Work).

Recently, the carbon dioxide radical anion (CO2•–) was exploited as the masked CO2 (C1 source) for carboxylation reactions, as shown in Scheme 1c.27−31 In addition, the polarity of CO2•– is reversed compared with CO2; thus, new reactivities could be expected for this radical anion species.32−40 For example, in 2022, Yu and co-workers reported the first carbo–carboxylation reaction of unactivated alkenes involving formation of the CO2•– species from CO2.41 In such reaction, the CO2•– was generated from CO2 via single electron transfer (SET) under highly reducing conditions (Ered = −2.21 V vs SCE).42 Therefore, certain photocatalysts and excess amounts of DIPEA as the sacrificial electron donor were necessary. From 2021, Li,43−45 Wickens,46−50 Li,51−53 Jui,54,55 Molander,56,57 Glorius,58 Fu,59,60 and Mita61,62 developed a series of carboxylation or reduction reactions with formate, a masked quantitative CO2 reagent, which could generate CO2•– species via hydrogen atom transfer (HAT). However, in the presence of the HAT catalyst, dicarboxylation of alkenes with formate as the sole carbonyl source is still challenging. Development of a new CO2•– precursor/masked CO2 reagent for dicarboxylation of alkenes under mild, clean, and sustainable manner is highly desired.

Light-induced intermolecular charge transfer (CT), or electron (E)–donor (D)–acceptor (A) complexes formed through assembly of two substrates that do not absorb at the desired wavelength individually, was recently applied as a principle to realize a photoredox cycle for synthetic organic chemistry in a photocatalyst-free manner.63−68 Recently, we found that tetrabutylammonium oxalate (TBAO) could act as an electron donor to generate the EDA complexes with electron deficient substrates, such as N-Bz imines, to access amino acids under catalyst-free conditions.69,70 During our further investigation on TBAO, herein, we disclose our recent development on the alkene dicarboxylation reaction with TBAO as the masked CO2 source via a unique electron transfer manner, where the noninnocent countercation played a significant role during the electron transformation process (Scheme 1d).

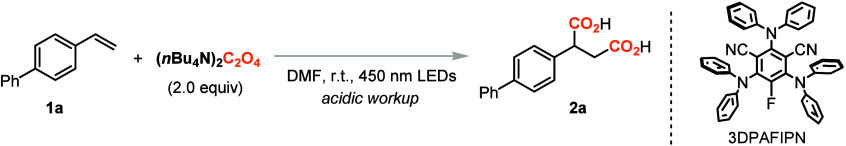

On the basis of the literature71−74 and our previous studies on CO2•– species,75−81 we envisioned that oxalic dianions could interact with aryl alkenes via anion−π interactions and be excited by photoirradiation to undergo SET and generate CO2•– and CO2. As expected, after careful screening of the reaction parameters (see more screening details in the Supporting Information), we realized the diacid product 2a in 73% isolated yield when substrate 1a was treated with tetrabutylammonium oxalate (TBAO) in DMF under 450 nm LED irradiation (Table 1, entry 1). The countercation of the oxalic salt is crucial as the Na+, NH4+, or Et4N+ could not convert the alkene to diacid at all (Table 1, entries 2–4). Two equivalents of TBAO were optimal to give the best yields (Table 1, entries 5 and 6). The wavelength of the light source was also screened, and 450 nm LEDs are the best to give the corresponding product 2a (Table 1, entries 7–9). Without light irradiation, no conversion of 1a was observed (Table 1, entry 10). Interestingly, a similar yield of 2a was obtained when 3DPAFIPN (2,4,6-tris(diphenylamino)-5-fluoroisophthalonitrile) was used as the photocatalyst.

Table 1. Optimization of the Reaction Conditionsa.

| entry | variation of the standard conditions | yield (%)b |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | none | 76(73)c |

| 2 | Na2C2O4 instead of TBAO | 0 |

| 3 | (NH4)2C2O4 instead of TBAO | 0 |

| 4 | (NEt4)2C2O4 instead of TBAO | 0 |

| 5 | 1.2 equiv of TBAO | 46 |

| 6 | 1.5 equiv of TBAO | 60 |

| 7 | 410 nm LEDs | 40 |

| 8 | 430 nm LEDs | 41 |

| 9 | 460 nm LEDs | 52 |

| 10 | no light | 0 |

| 11 | with 3DPAFIPN and CsFd | 76 |

Reaction conditions: 1a (0.2 mmol) and oxalate (2.0 equiv) in DMF (0.13 M) at r.t. for 12 h under N2 atmosphere.

Crude 1H NMR yield with dichloroethane as the internal standard.

Isolated yield.

3DPAFIPN (2.0 mol %) and CsF (5.0 equiv) were used.

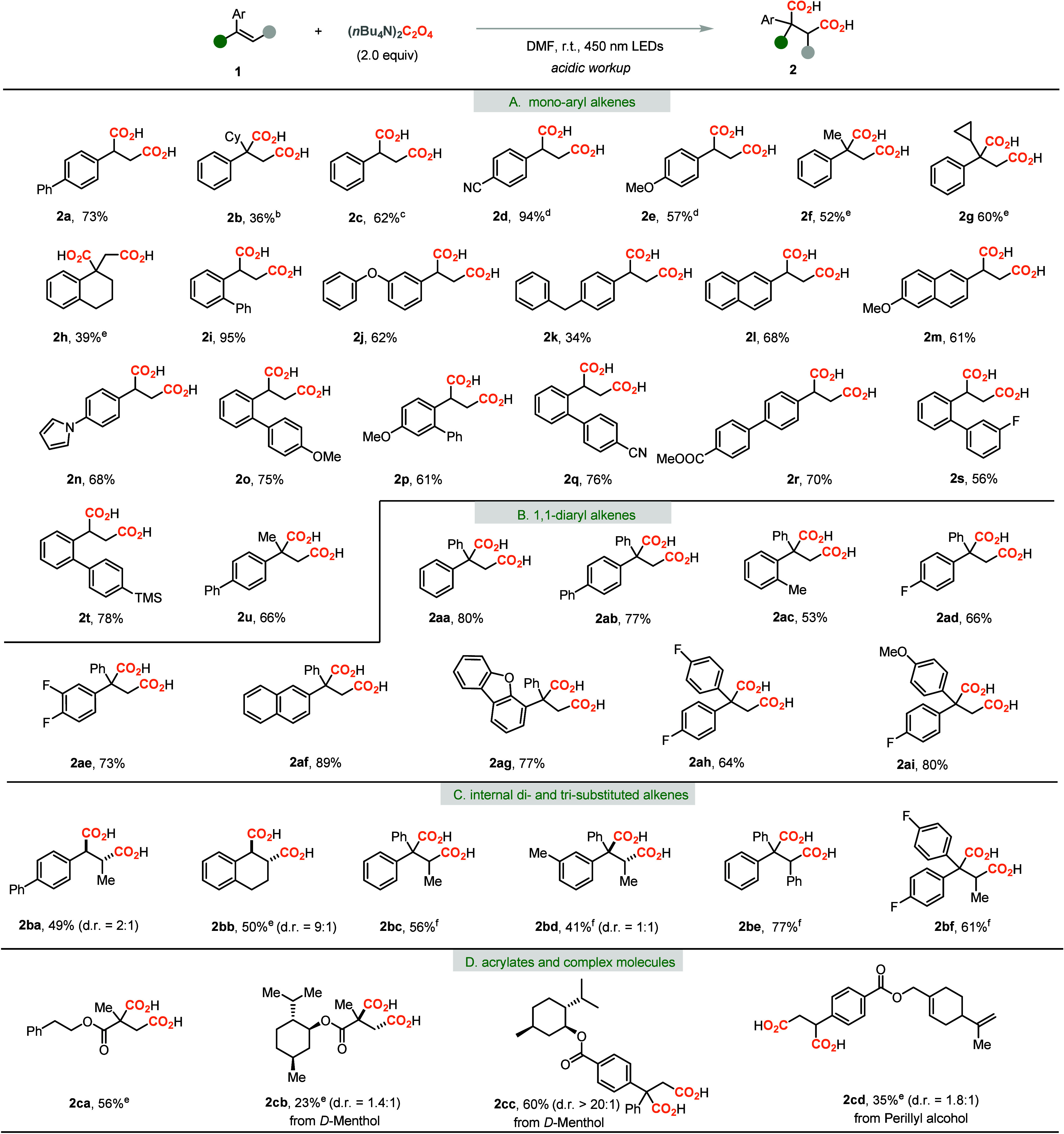

This is encouraging as there was no literature precedent showing that alkenes react with oxalate without any photocatalyst or additive to form the succinic acids. To further understand the reaction mechanism and test the substrate scope, we next treated α-cyclohexyl styrene (1b) with the standard reaction conditions. However, no desired diacid 2b was observed. Interestingly, when the reaction was conducted under a CO2 atmosphere, the desired diacid 2b was isolated in 36% yield. Afterward, the styrene 1c was investigated and the desired diacid 2c was isolated in 62% yield when a catalytic amount of 3DPAFIPN was added in the reaction. For para-MeO or para-CN substituted styrenes (1d and 1e), both the photocatalyst and the CO2 atmosphere were necessary for the dicarboxylation process. It seems that the biaryl structure on substrate 1a is crucial to initiate the reaction. Afterward, some other 1,1-disubstituted monoaryl styrenes 1f–1h were tested, and the corresponding desired diacids could also be obtained in the presence of photocatalyst. With these results in hand, we envisioned that the highly conjugated alkenyl substrate might be crucial to realize the diacids. Therefore, the 2-phenyl aryl alkene 1i was tested and the desired product 2i was isolated in 95% yield in the absence of any additive. The 3-phenoxyl aryl alkene 1j was also a good substrate for the dicarboxylation process to give 2j in 62% yield. When the 4-benzyl aryl alkene 1k was examined, the product 2k was formed, although the yield is only 34%.

The heteroarene pyrrole was also tolerated in this reaction (2n). Afterward, the substituents on the aryl ring of substrates were tested to verify the functional group tolerance and electron density effluences. The methoxy (2o and 2p), cyano (2q), ester (2r), and fluoro (2s) groups were well tolerated and provided the desired diacids in satisfied yields. The vulnerable trimethylsilyl (TMS) group was also retained after the transformation to give product 2t in 78% yield. Moreover, the disubstituted alkene 1u was investigated and the corresponding diacid 2u was obtained in good yield.

To further elaborate the utility of this protocol for dicarboxylation, various 1,1-diaryl alkenes were examined under the optimized reaction conditions. The electron density on the aryl ring did not affect the reaction efficiency, and products 2aa–2ae tethering fluoro or methyl groups were obtained in good yields. The naphthyl and heteroaryl substituents were also tolerated well to give the desired product in up to 89% yield (2af and 2ag). The fluoro and methoxy groups tethered on the aryl rings were also amenable (2ah and 2ai). To our delight, the steric hindered trisubstituted alkenes also worked well to give the diacids in moderate to good yields (Table 2C, 2ba–2bf). In most cases, elevated temperature was required to realize satisfied yields. Then, the acrylate derivative 1ca as well as the d-menthol derived acrylate 1cb were treated with the standard conditions to give the diacids 2ca and 2cb in 56% and synthetically useful yield, respectively, without degradation of the ester motif. The 1,1-diaryl alkene 1cc derived from d-menthol could also be converted to diacid 2cc in 60% yield. Interestingly, the perillyl alcohol derived substrate 1cd, which has multiple alkenyl moieties, could give the chemoselective dicarboxylation product 2cd in synthetically useful yield in the presence of photocatalyst. Overall, various biaryl styrenes and 1,1-diaryl alkenes could be smoothly converted to the corresponding diacids in good yields without a photocatalyst or additives. However, the monoaryl alkenes were inert for this transformation, and addition of photocatalyst is required. The highly conjugated π-system seems crucial in initiating the photocatalyst-free charge transfer process of the reaction. As the CO2 radical anion was generated as a strong reductant during the transformation, dehalogenation or reduction of the carbonyl groups happened and no desired products were isolated from the halo- or carbonyl substrates.

Table 2. Scope of Alkenes and Later Stage Modification of Natural Productsa.

Reaction conditions: 1 (0.2 mmol) and (nBu4N)2C2O4 (2.0 equiv) in DMF (0.13 M) at r.t. for 12–48 h under N2 atmosphere and 450 nm LED irradiation.

CO2 atmosphere.

3DPAFIPN (2.5 mol %) and CsF (8.0 equiv) were used.

3DPAFIPN (2.5 mol %), CsF (5.0 equiv), and CO2 atmosphere were used.

3DPAFIPN (2.5 mol %) and CsF (5.0 equiv) were used.

50 °C instead of r.t.

Aryl dienes also own a highly conjugated π-system that is probably suitable for the catalyst-free dicarboxylation process. As we know, dicarboxylation of dienes would provide unsaturated diacids with diverse functional groups as the modification handles. However, such reactions were rarely disclosed with limited examples and relatively low yields.8 Therefore, various aryl dienes were exploited, as shown in Table 3. When 1,1-diphenyl 1,3-butadiene (3a) was treated with the standard reaction conditions, to our delight, unsaturated dicarboxylic acid 4a was obtained in 90% yield. The substrates bearing a methyl, phenyl, or fluoro group could also react smoothly and gave the 1,3-dicarboxylated products in good yields as the E/Z mixtures (4b–4f). A relatively higher temperature of 50 °C was required to get good regioselectivity, and formation of the 1,4-dicarboxylation product was completely prohibited. When the monoaryl substituted diene 3g was investigated, the 1,4-dicarboxylation product 5g was obtained in 29% yield with excellent regioselectivity and E/Z ratio. When diene 3h was utilized, the desired unsaturated diacid 5h was obtained in 62% yield. The naphthyl substituted diene 3i was also a good candidate for the 1,4-dicarboxylation process. The disubstituted and internal dienes were also tested, and the unsaturated diacids 5k–5l were obtained in good yields. When 1,3-dienes were treated with the standard reaction conditions, the allyl radicals would prefer the isomerization and form the less steric hindered radicals or more stabilized benzylic radicals. Therefore, 1,4-dicarboxylation was observed for dienes 5g–5l. Interestingly, the dicarboxylation process can be applied for the triene system 3m, and the 1,6-dicarboxylation product 5m with a dienyl functionality was isolated in 37% yield with excellent regioselectivity.

Table 3. Scope of Dienes for Selective 1,2- or 1,4-Dicarboxylationa.

Reaction conditions: 1 (0.2 mmol) and (nBu4N)2C2O4 (2.0 equiv) were irradiated with 450 nm LEDs in DMF (0.13 M) at r.t. for 12–48 h under N2 atmosphere.

50 °C was used instead of r.t.

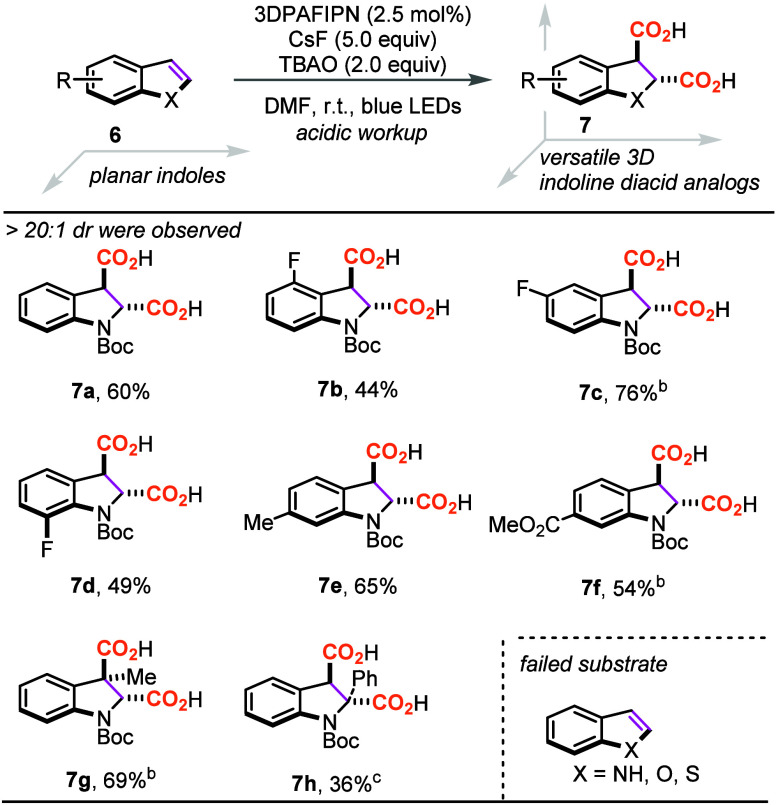

As shown in Table 4, N-Boc protected indole (6a) was then investigated and dearomatization of the indole ring happened in the presence of photocatalyst, providing the dicarboxylated indoline product 6a in 60% yield. Afterward, the effects of the fluoro group on the 4, 5, and 7 positions were examined, and all of them could be converted to the corresponding diacids in moderate to good yields (7b–7d). 6-Methylindole 6e and ester 6f could also be converted to indoline diacids 7e and 7f, respectively, in good yields. The 3-methyl substituted indole 6g, which is sterically hindered, was also amenable to give 7g in 69% yield, although excess amounts of base were required. Interestingly, 2-phenyl indole 6h could provide diacid 7h in 36% yield even in the absence of the photocatalyst. This result suggested again that a highly conjugated π-system could trigger single electron transfer under photoirradiation in the absence of photocatalyst.

Table 4. Scope of Indoles for 1,2-Dicarboxylationa.

Reaction conditions: 6 (0.2 mmol), 3DPAFIPN (2.5 mol %), (nBu4N)2C2O4 (2.0 equiv), and CsF (5.0 equiv) in DMF (0.13 M) at r.t. for 12–48 h under N2 atmosphere and 450 nm LED irradiation.

CsF (8.0 equiv) was used.

Without 3DPAFIPN.

To further elaborate the synthetic utility of this difunctionalization reaction and probe the formation of carbon anion intermediates during the transformation, the deuterocarboxylation of the representative alkenes was investigated, as shown in Table 5. The 1,1-diaryl alkenes were good substrates for deuterocarboxylation to give product 8a in 69% yield with a 90% deuteration ratio. The steric hindered trisubstituted alkene was also amenable to give 8b in good yield and deuteration ratio. It is not surprising that the diene substrate could also be converted to the corresponding deuterocarboxylic acid 8c in a moderate yield and deuteration ratio. When the simple styrene substrates were examined, the deuterocarboxylation products (8d and 8e) could also be obtained. However, the addition of photocatalyst to the reaction system is required.

Table 5. Representative Examples for Deuterocarboxylationa.

Reaction conditions: 1 or 3 (0.2 mmol), (nBu4N)2C2O4 (2.0 equiv), and D2O (2.0–10.0 equiv as indicated in the SI) in DMF (0.13 M) at r.t. or 50 °C under N2 atmosphere and 450 nm LED irradiation.

3DPAFIPN (2.5 mol %) was used.

Moreover, the application of the diacid products obtained in this reaction were conducted as shown in Scheme 2. First, the large-scale reaction of substrate 1a was investigated and the desired diacid 2a was obtained in 56% yield. Afterward, the succinic acid 2aa could be easily converted to the pyrrolidine-2,5-dione 9, which is the precursor for anticonvulsant drug derivatives.82 The unsaturated diacid 4a was first methylated to give diester 10 and the alkenyl moiety could be further converted to functionalized six-membered lactone 11 in the presence of NBS in DMSO. The indoline 7a was methylated and then the Boc group was deprotected under acidic conditions. The rearomatization of the indole ring was realized by treating it with DDQ in dioxane. Indole 14 could be further converted into various biologically active drug molecules.83,84

Scheme 2. Applications of the Reaction.

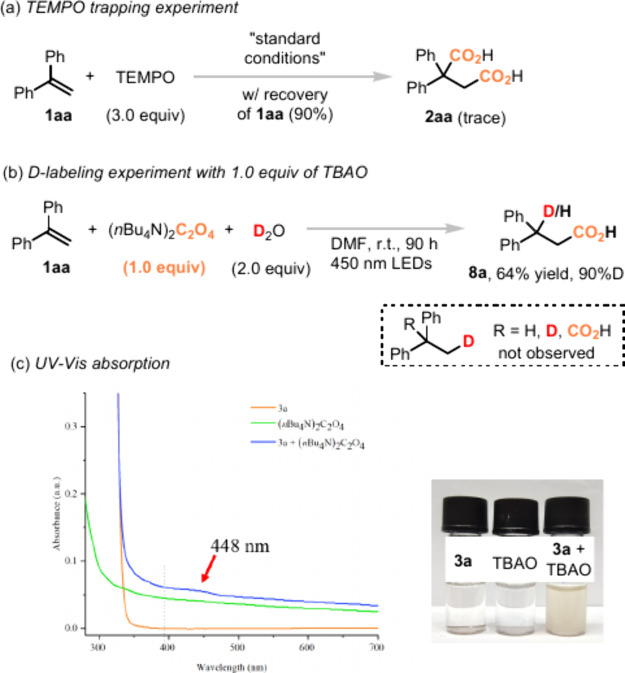

To gain further insights into the reaction mechanism, several control experiments were conducted, as shown in Scheme 3. To see if the reaction proceeded via the generation of radical species, TEMPO (2,2,6,6-tetramethylpiperidinyloxy) was added to the reaction with 1aa. The dicarboxylation process was prohibited, and only a trace amount of 2aa was detected. The TEMPO trapped adduct 15 was not detected, which might be due to the steric hindrance. To see if the electron was transferred directly from the oxalic dianion to the alkene substrate, the deuterium labeling experiment was conducted with D2O, as shown in Scheme 3b. The monocarboxylation product 8a was obtained in 64% yield and 90% deuterium labeling ratio. Only deuteration on the benzyl position was observed, indicating formation of the benzyl anion intermediate during the transformation. It is worth noting that only 1.0 equiv of TBAO was utilized in this reaction, which means both of two electrons from the oxalic dianion were transferred to the final product and no electron was wasted during the transformation.

Scheme 3. Mechanistic Studies.

Combined with the phenomenon that simple monoaryl styrene provided no diacid product in the absence of photocatalyst, we could get the conclusion that the highly conjugated π-system is crucial to trigger the electron transfer process and cause the homolysis of the oxalic radical anion. A new CT or EDA complex was probably formed in this reaction. Indeed, the UV–vis absorption experiments showed that a bathochromic shift of the absorption band was observed (Scheme 3c, blue line). A new absorption peak at a wavelength of 448 nm was detected, meaning that a new complex was formed between the substrate and oxalate, which could be excited at a wavelength of 450 nm LEDs. In the meantime, the color change from colorless to yellow for the mixture of substrate 3a and TBAO was also observed (Scheme 3c).

As shown in Scheme 4, on the basis of the above results, we proposed that the reaction was first initiated by photoexcitation of the EDA complex formed between alkene substrate and TBAO. The C—C bond of the oxalic dianion was fixed in the presence of highly conjugated substrate and not able to freely rotate, which decreased the energy barrier for single electron transfer. Afterward, one electron transfer from the oxalic dianion to the alkene substrate occurred to give the oxalic radical anion and the radical anion form of the alkene substrate (intermediate I). Subsequently, the homolysis of the oxalate radical anion generated CO2 and CO2•–, which underwent radical recombination to the intermediate I within the aggregate and established the first carboxy group, generating the benzylic anion intermediate II. Afterward, the benzyl anion intermediate II could trap the CO2 released from the oxalate and install the second carboxy group to give the diacid product 2aa. In the presence of D2O, deuteration is more favorable than the second carboxylation process, producing deuterated carboxylic acid 8a as the sole product.

Scheme 4. Proposed Mechanism for Dicarboxylation of Alkene 1aa.

In summary, a visible-light-induced additive-free alkene dicarboxylation reaction with TBAO was developed. Formation of the EDA complex between the oxalic dianion and the alkene substrate is crucial to triggering the intramolecular single electron transfer. The radical recombination of CO2•– with the carbon-centered radical showcased a new way to establish the carboxyl group. This is the first example that oxalate acts as both the C1 source and reductant for alkene dicarboxylation via formation of an EDA complex in the absence of any additives. Further applications of TBAO in synthetic organic chemistry under photocatalytic conditions are currently underway in our laboratory.

Acknowledgments

The authors are appreciative of the insightful discussions and suggestions from Prof. Shunsuke Chiba (Nanyang Technological University) and Prof. Shouyun Yu (Nanjing University) on the reaction mechanism. This work was financially supported by the Jiangsu Province Shuangchuang Ph.D. award (JSSCBS20211267, Pei Xu) and the Natural Science Research Project of Jiangsu Universities (23KJB150037, Pei Xu). This work was also sponsored by the Jiangsu Specially-Appointed Professor program (Xu Zhu) and the start-up funding provided by Xuzhou Medical University. The Public Experimental Research Center of Xuzhou Medical University is also acknowledged.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available in the Supporting Information of this article.

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge at https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acscentsci.4c01464.

Experimental procedures including optimization of reaction conditions, synthesis of substrates, acid derivatives, application of the reaction, control experiments, 1H and 13C NMR spectra, and mass data (PDF)

Author Contributions

∇ These authors contributed equally to this work.

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- Fang S.; Rahaman M.; Bharti J.; Reisner E.; Robert M.; Ozin G. A.; Hu Y. H. Photocatalytic CO2 Reduction. Nat. Rev. Methods Primers 2023, 3, 61. 10.1038/s43586-023-00243-w. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fan L.; Xia C.; Yang F.; Wang J.; Wang H.; Lu Y. Strategies in Catalysts and Electrolyzer Design for Electrochemical CO2 Reduction Toward C2+ Products. Sci. Adv. 2020, 6, eaay3111 10.1126/sciadv.aay3111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ye J.-H.; Ju T.; Huang H.; Liao L.-L.; Yu D.-G. Radical Carboxylative Cyclizations and Carboxylations with CO2. Acc. Chem. Res. 2021, 54, 2518–2531. 10.1021/acs.accounts.1c00135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cai B.; Cheo H. W.; Liu T.; Wu J. Light-Promoted Organic Transformations Utilizing Carbon-Based Gas Molecules as Feedstocks. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2021, 60, 18950–18980. 10.1002/anie.202010710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ran C.-K.; Xiao H. Z.; Liao L. L.; Ju T.; Zhang W.; Yu D.-G. Progress and Challenges in Dicarboxylation with CO2. Natl. Sci. Open 2023, 2, 20220024 10.1360/nso/20220024. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yue J.-P.; Xu J.-C.; Luo H.-T.; Chen X.-W.; Song H.-X.; Deng Y.; Yuan L.; Ye J.-H.; Yu D.-G. Metallaphotoredox-enabled Aminocarboxylation of Alkenes with CO2. Nat. Catal. 2023, 6, 959–968. 10.1038/s41929-023-01029-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yuan P.-F.; Yang Z.; Zhang S.-S.; Zhu C.-M.; Yang X.-L.; Meng Q.-Y. Deconstructive Carboxylation of Activated Alkenes with Carbon Dioxide. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2024, 63, e202313030 10.1002/anie.202313030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cao K.-G.; Gao T.-Y.; Liao L.-L.; Ran C.-K.; Jiang Y.-X.; Zhang W.; Zhou Q.; Ye J.-H.; Lan Y.; Yu D.-G. Photocatalytic Carboxylation of Styrenes with CO2 via C=C Double Bond Cleavage. Chin. J. Catal. 2024, 56, 74–80. 10.1016/S1872-2067(23)64583-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yu B.; Liu Y.; Xiao H.-Z.; Zhang S.-R.; Ran C.-K.; Song L.; Jiang Y.-X.; Li C.-F.; Ye J.-H.; Yu D.-G. Switchable Divergent Di- or Tricarboxylation of Allylic Alcohols with CO2. Chem. 2024, 10, 938–951. 10.1016/j.chempr.2023.12.005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Q.; Wang Y.; Liu M.; Chu G.; Qiu Y. Recent Advances in Photochemical/Electrochemical Carboxylation of Olefins with CO2. Chin. J. Chem. 2024, 42, 2249–2266. 10.1002/cjoc.202400008. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Liu X.-F.; Zhang K.; Tao L.; Lu X.-B.; Zhang W.-Z. Recent Advances in Electrochemical Carboxylation Reactions Using Carbon Dioxide. Green Chem. Eng. 2022, 3, 125–137. 10.1016/j.gce.2021.12.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Noji M.; Suzuki K.; Tashiro T.; Suzuki M.; Harada K.; Masuda K.; Kidani Y. Syntheses and Antitumor Activities of 1R,2R-Cyclohexanediamine Pt (II) Complexes Containing Dicarboxylate. Chem. Pharm. Bull. 1987, 35, 221–228. 10.1248/cpb.35.221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arason K. M.; Bergmeier S. C. The Synthesis of Succinic acids and Derivatives. A Review. Org. Prep. Proced. Int. 2002, 34, 337–366. 10.1080/00304940209458074. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Volchegorskii I. A.; Sinitskii A. I.; Miroshnichenko I. Yu.; Rassokhina L. M. Effects of 3-Hydroxypyridine and Succinic Acid Derivatives on Monoamine Oxidase Activity in Vitro. Pharm. Chem. J. 2018, 52, 26. 10.1007/s11094-018-1760-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Derien S.; Clinet J.-C.; Duñach E.; Perichon J. Electrochemical Incorporation of Carbon Dioxide into Alkenes by Nickel Complexes. Tetrahedron 1992, 48, 5235–5248. 10.1016/S0040-4020(01)89021-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Senboku H.; Komatsu H.; Fujimura Y.; Tokuda M. Efficient Electrochemical Dicarboxylation of Phenyl-Substituted Alkenes: Synthesis of 1-Phenylalkane-1,2-Dicarboxylic Acids. Synlett 2001, 3, 418–420. 10.1055/s-2001-11417. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wang H.; Lin M.-Y.; Fang H.-J.; Chen T.-T.; Lu J.-X. Electrochemical Dicarboxylation of Styrene: Synthesis of 2-Phenylsuccinic Acid. Chin. J. Chem. 2007, 25, 913–916. 10.1002/cjoc.200790177. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yuan G.-Q.; Jiang H.-F.; Lin C.; Liao S.-J. Efficient Electrochemical Synthesis of 2-Arylsuccinic Acids from CO2 and Aryl-Substituted Alkenes with Nickel as the Cathode. Electrochim. Acta 2008, 53, 2170–2176. 10.1016/j.electacta.2007.09.023. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Li C.-H.; Yuan G.-Q.; Ji X.-C.; Wang X.-J.; Ye J.-S.; Jiang H.-F. Highly Regioselective Electrochemical Synthesis of Dioic Acids from Dienes and Carbon Dioxide. Electrochim. Acta 2011, 56, 1529–1534. 10.1016/j.electacta.2010.06.057. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- You Y.; Kanna W.; Takano H.; Hayashi H.; Maeda S.; Mita T. Electrochemical Dearomative Dicarboxylation of Heterocycles with Highly Negative Reduction Potentials. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2022, 144, 3685–3695. 10.1021/jacs.1c13032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang W.; Liao L.-L.; Li L.; Liu Y.; Dai L.-F.; Sun G.-Q.; Ran C.-K.; Ye J.-H.; Lan Y.; Yu D.-G. Electroreductive Dicarboxylation of Unactivated Skipped Dienes with CO2. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2023, 62, e202301892 10.1002/anie.202301892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yeung C. S. Photoredox Catalysis as a Strategy for CO2 Incorporation: Direct Access to Carboxylic Acids from a Renewable Feedstock. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2019, 58, 5492–5502. 10.1002/anie.201806285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu X.-Y.; Chen J.-R.; Xiao W.-J. Visible Light-Driven Radical-Mediated C–C Bond Cleavage/Functionalization in Organic Synthesis. Chem. Rev. 2021, 121, 506–561. 10.1021/acs.chemrev.0c00030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allen R. A.; Noten E. A.; Stephenson C. R. J. Aryl Transfer Strategies Mediated by Photoinduced Electron Transfer. Chem. Rev. 2022, 122, 2695–2751. 10.1021/acs.chemrev.1c00388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bellotti P.; Huang H.-M.; Faber T.; Glorius F. Photocatalytic Late-Stage C–H Functionalization. Chem. Rev. 2023, 123, 4237–4352. 10.1021/acs.chemrev.2c00478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ju T.; Zhou Y.-Q.; Cao K.-G.; Fu Q.; Ye J.-H.; Sun G.-Q.; Liu X.-F.; Chen L.; Liao L.-L.; Yu D.-G. Dicarboxylation of Alkenes, Allenes and (Hetero)arenes with CO2 via Visible-Light Photoredox Catalysis. Nat. Catal. 2021, 4, 304–311. 10.1038/s41929-021-00594-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gui Y. Y.; Yan S.-S.; Wang W.; Chen L.; Zhang W.; Ye J. H.; Yu D.-G. Exploring the Applications of Carbon Dioxide Radical Anion in Organic Synthesis. Sci. Bull. 2023, 68, 3124–3128. 10.1016/j.scib.2023.11.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Majhi J.; Molander G. A. Recent Discovery, Development, and Synthetic Applications of Formic Acid Salts in Photochemistry. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2024, 63, e202311853 10.1002/anie.202311853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiao W.; Zhang J.; Wu J. Recent Advances in Reactions Involving Carbon Dioxide Radical Anion. ACS Catal. 2023, 13, 15991–16011. 10.1021/acscatal.3c04125. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wang S.; Xu P.; Zhu X. CO2 Radical Anion in Photochemical Dicarboxylation of Alkenes. ChemCatChem. 2023, 15, e202300695 10.1002/cctc.202300695. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Shen Q.; Cao K.; Wen X.; Li J. Formate Salts: The Rediscovery of Their Radical Reaction under Light Irradiation Opens New Avenues in Organic Synthesis. Adv. Synth. Catal. 2024, 10.1002/adsc.202400682. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Seo H.; Katcher M. H.; Jamison T. F. Photoredox Activation of Carbon Dioxide for Amino Acid Synthesis in Continuous Flow. Nat. Chem. 2017, 9, 453–456. 10.1038/nchem.2690. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seo H.; Liu A.; Jamison T. F. Direct β-Selective Hydrocarboxylation of Styrenes with CO2 Enabled by Continuous Flow Photoredox Catalysis. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2017, 139, 13969–13972. 10.1021/jacs.7b05942. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ye J.-H.; Miao M.; Huang H.; Yan S.-S.; Yin Z.-B.; Zhou W.-J.; Yu D.-G. Visible-Light-Driven Iron-Promoted Thiocarboxylation of Styrenes and Acrylates with CO2. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2017, 56, 15416–15420. 10.1002/anie.201707862. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yan S.-S.; Liu S.-H.; Chen L.; Bo Z.-Y.; Jing K.; Gao T.-Y.; Yu B.; Lan Y.; Luo S.-P.; Yu D.-G. Visible-Light Photoredox-Catalyzed Selective Carboxylation of C(sp3)–F Bonds with CO2. Chem. 2021, 7, 3099–3113. 10.1016/j.chempr.2021.08.004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bo Z.-Y.; Yan S.-S.; Gao T.-Y.; Song L.; Ran C.-K.; He Y.; Zhang W.; Cao G.-M.; Yu D.-G. Visible-Light Photoredox-Catalyzed Selective Carboxylation of C(sp2)–F Bonds in Polyfluoroarenes with CO2. Chin. J. Catal. 2022, 43, 2388–2394. 10.1016/S1872-2067(22)64140-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang W.; Chen Z.; Jiang Y.-X.; Liao L.-L.; Wang W.; Ye J.-H.; Yu D.-G. Arylcarboxylation of Unactivated Alkenes with CO2 via Visible-light Photoredox Catalysis. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 3529. 10.1038/s41467-023-39240-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miao M.; Zhu L.; Zhao H.; Song L.; Yan S.-S.; Liao L.-L.; Ye J.-H.; Lan Y.; Yu D.-G. Visible-Light-Driven Thio-Carboxylation of Alkynes with CO2: Facile Synthesis of Thiochromones. Sci. China Chem. 2023, 66, 1457–1466. 10.1007/s11426-022-1554-x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Xiao H.-Z.; Yu B.; Yan S.-S.; Zhang W.; Li X.-X.; Bao Y.; Luo S.-P.; Ye J.-H.; Yu D.-G. Photocatalytic 1,3-Dicarboxylation of Unactivated Alkenes with CO2. Chin. J. Catal. 2023, 50, 222–228. 10.1016/S1872-2067(23)64468-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao Z.; Liu Y.; Wang S.; Tang S.; Ma D.; Zhu Z.; Guo C.; Qiu Y. Site-Selective Electrochemical C–H Carboxylation of Arenes with CO2. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2023, 62, e202214710 10.1002/anie.202214710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song L.; Wang W.; Yue J.-P.; Jiang Y.-X.; Wei M.-K.; Zhang H.-P.; Yan S.-S.; Liao L.-L.; Yu D.-G. Visible-light Photocatalytic di- and Hydro-carboxylation of Unactivated Alkenes with CO2. Nat. Catal. 2022, 5, 832–838. 10.1038/s41929-022-00841-z. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Koppenol W. H.; Rush J. D. Reduction Potential of the Carbon Dioxide/Carbon Dioxide Radical Anion: a Comparison with Other C1 Radicals. J. Phys. Chem. 1987, 91, 4429–4430. 10.1021/j100300a045. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wang H.; Gao Y.; Zhou C.; Li G. Visible-Light-Driven Reductive Carboarylation of Styrenes with CO2 and Aryl Halides. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2020, 142, 8122–8129. 10.1021/jacs.0c03144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou C.; Wang X.; Yang L.; Fu L.; Li G. Visible-light-driven Regioselective Carbocarboxylation of 1,3-Dienes with Organic Halides and CO2. Geen Chem. 2022, 24, 6100–6107. 10.1039/D2GC01256A. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang F.; Wu X.-Y.; Gao P.-P.; Zhang H.; Li Z.; Ai S.; Li G. Visible-Light-Driven Alkene Dicarboxylation with Formate and CO2 under Mild Conditions. Chem. Sci. 2024, 15, 6178–6183. 10.1039/D3SC04431A. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alektiar S. N.; Wickens Z. K. Photoinduced Hydrocarboxylation via Thiol Catalyzed Delivery of Formate Across Activated Alkenes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2021, 143, 13022–13028. 10.1021/jacs.1c07562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chmiel A. F.; Williams O. P.; Chernowsky C. P.; Yeung C. S.; Wickens Z. K. Non-innocent Radical Ion Intermediates in Photoredox Catalysis: Parallel Reduction Modes Enable Coupling of Diverse Aryl Chlorides. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2021, 143, 10882–10889. 10.1021/jacs.1c05988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alektiar S. N.; Han J.; Dang Y.; Rubel C. Z.; Wickens Z. K. Radical Hydrocarboxylation of Unactivated Alkenes via Photocatalytic Formate Activation. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2023, 145, 10991–10997. 10.1021/jacs.3c03671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams O. P.; Chmiel A. F.; Mikhael M.; Bates D. M.; Yeung C. S.; Wickens Z. K. Practical and General Alcohol Deoxygenation Protocol. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2023, 62, e202300178 10.1002/anie.202300178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mikhael M.; Alektiar S. N.; Yeung C. S.; Wickens Z. K. Translating Planar Heterocycles into Three-Dimensional Analogs by Photoinduced Hydrocarboxylation. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2023, 62, e202303264 10.1002/anie.202303264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang Y.; Hou J.; Zhan L.-W.; Zhang Q.; Tang W.-Y.; Li B.-D. Photoredox Activation of Formate Salts: Hydrocarboxylation of Alkenes via Carboxyl Group Transfer. ACS Catal. 2021, 11, 15004–15012. 10.1021/acscatal.1c04684. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Huang Y.; Zhang Q.; Hua L.-L.; Zhan L.-W.; Hou J.; Li B.-D. A Versatile Catalyst-Free Redox System Mediated by Carbon Dioxide Radical and Dimsyl Anions. Cell Rep. Phys. Sci. 2022, 3, 100994 10.1016/j.xcrp.2022.100994. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Huang Y.; Wan Y.-C.; Shao Y.; Zhan L.-W.; Li B.-D.; Hou J. Catalyst-Free Defluorinative Alkylation of Trifluoromethyls. Green Chem. 2023, 25, 8280–8285. 10.1039/D3GC02547K. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hendy C. M.; Smith G. C.; Xu Z.; Lian T.; Jui N. T. Radical Chain Reduction via Carbon Dioxide Radical Anion (CO2•–). J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2021, 143, 8987–8992. 10.1021/jacs.1c04427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maust M. C.; Hendy C. M.; Jui N. T.; Blakey S. B. Switchable Regioselective 6-endo or 5-exo Radical Cyclization via Photoredox Catalysis. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2022, 144, 3776–3781. 10.1021/jacs.2c00192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell M. W.; Polites V. C.; Patel S.; Lipson J. E.; Majhi J.; Molander G. A. Photochemical C–F Activation Enables Defluorinative Alkylation of Trifluoroacetates and -Acetamides. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2021, 143, 19648–19654. 10.1021/jacs.1c11059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Majhi J.; Matsuo B.; Oh H.; Kim S.; Sharique M.; Molander G. A. Photochemical Deoxygenative Hydroalkylation of Unactivated Alkenes Promoted by a Nucleophilic Organocatalyst. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2024, 63, e202317190 10.1002/anie.202317190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ye J.-H.; Bellotti P.; Heusel C.; Glorius F. Photoredox-Catalyzed Defluorinative Functionalizations of Polyfluorinated Aliphatic Amides and Esters. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2022, 61, e202115456 10.1002/anie.202115456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fu M.-C.; Wang J.-X.; Ge W.; Du F.-M.; Fu Y. Dual Nickel/Photoredox Catalyzed Carboxylation of C(sp2)-Halides with Formate. Org. Chem. Front. 2022, 10, 35–41. 10.1039/D2QO01361D. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ge W.; Wang J.-X.; Fu M.-C.; Fu Y. Photoinduced Dehalocyclization to Access Oxindoles Using Formate as a Reductant. Chin. J. Chem. 2024, 42, 1203–1208. 10.1002/cjoc.202300740. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mangaonkar S. R.; Hayashi H.; Takano H.; Kanna W.; Maeda S.; Mita T. Photoredox/HAT-Catalyzed Dearomative Nucleophilic Addition of the CO2 Radical Anion to (Hetero)Aromatics. ACS Catal. 2023, 13, 2482–2488. 10.1021/acscatal.2c06192. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mangaonkar S. R.; Hayashi H.; Kanna W.; Debbarma S.; Harabuchi Y.; Maeda S.; Mita T. γ-Butyrolactone Synthesis from Allylic Alcohols Using the CO2 Radical Anion. Precis. Chem. 2024, 2, 88–95. 10.1021/prechem.3c00117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lima C. G. S.; de M. Lima T.; Duarte M.; Jurberg I. D.; Paixao M. W. Organic Synthesis Enabled by Light-Irradiation of EDA Complexes: Theoretical Background and Synthetic Applications. ACS Catal. 2016, 6, 1389–1407. 10.1021/acscatal.5b02386. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Morack T.; Mück-Lichtenfeld C.; Gilmour R. Bioinspired Radical Stetter Reaction: Radical Umpolung Enabled by Ion-Pair Photocatalysis. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2019, 58, 1208–1212. 10.1002/anie.201809601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crisenza G. E. M.; Mazzarella D.; Melchiorre P. Synthetic Methods Driven by the Photoactivity of Electron-Donor Acceptor Complexes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2020, 142, 5461–5476. 10.1021/jacs.0c01416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang H.; Ye J.-H.; Zhu L.; Ran C.-K.; Miao M.; Wang W.; Chen H.; Zhou W.-J.; Lan Y.; Yu B.; Yu D.-G. Visible-Light-Driven Anti-Markovnikov Hydrocarboxylation of Acrylates and Styrenes with CO2. CCS Chem. 2021, 3, 1746–1756. 10.31635/ccschem.020.202000374. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang Y.-X.; Liao L.-L.; Gao T.-Y.; Xu W.-H.; Zhang W.; Song L.; Sun G.-Q.; Ye J.-H.; Lan Y.; Yu D.-G. Visible-Light-Driven Synthesis of N-Heteroaromatic Carboxylic Acids by Thiolate-Catalysed Carboxylation of C(sp2)–H Bonds Using CO2. Nat. Synth. 2024, 3, 394–405. 10.1038/s44160-023-00465-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Xue T.; Ma C.; Liu L.; Xiao C.; Ni S.-F.; Zeng R. Characterization of A π–π Stacking Cocrystal of 4-Nitrophthalonitrile Directed toward Application in Photocatalysis. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 1455. 10.1038/s41467-024-45686-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu W.-W.; Xu P.; Jiang H.-X.; Li M.-L.; Hao T.-Z.; Liu Y.-Q.; Zhu S.-L.; Zhang K.-X.; Zhu X. Photochemical Reductive Carboxylation of N-Benzoyl Imines with Oxalate Accelerated by Formation of EDA Complexes. ACS Catal. 2024, 14, 10053–10059. 10.1021/acscatal.4c02007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou M.-H.; Jiang J.; He W.-M. Chin. Chem. Lett. 2025, 36, 110446 10.1016/j.cclet.2024.110446. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kai T.; Zhou M.; Johnson S.; Ahn H. S.; Bard A. J. Direct Observation of C2O4•– and CO2•– by Oxidation of Oxalate within Nanogap of Scanning Electrochemical Microscope. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2018, 140, 16178–16183. 10.1021/jacs.8b08900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu Z.; Wu M.; Zhu K.; Wu J.; Lu Y. Photocatalytic Coupling of Electron-Deficient Alkenes Using Oxalic Acid as a Traceless Linchpin. Chem. 2023, 9, 978–988. 10.1016/j.chempr.2022.12.013. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Matsumoto A.; Maeda N.; Maruoka K. Bidirectional Elongation Strategy Using Ambiphilic Radical Linchpin for Modular Access to 1,4-Dicarbonyls via Sequential Photocatalysis. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2023, 145, 20344–20354. 10.1021/jacs.3c05337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tong X.; Wu Z.; Ang H. T.; Miao Y.; Lu Y.; Wu J. Photocatalytic Reductive Functionalization of Aryl Alkynes via Alkyne Radical Anions. ACS Catal. 2024, 14, 9283–9293. 10.1021/acscatal.4c02638. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Xu P.; Wang X.-Y.; Wang Z.; Zhao J.; Cao X.-D.; Xiong X.-C.; Yuan Y.-C.; Zhu S.; Guo D.; Zhu X. Defluorinative Alkylation of Trifluoromethylbenzimidazoles Enabled by Spin-Center Shift: A Synergistic Photocatalysis/Thiol Catalysis Process with CO2•–. Org. Lett. 2022, 24, 4075–4080. 10.1021/acs.orglett.2c01533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu P.; Wang S.; Xu H.; Liu Y.-Q.; Li R.-B.; Liu W.-W.; Wang X.-Y.; Zou M.-L.; Zhou Y.; Guo D.; Zhu X. Dicarboxylation of Alkenes with CO2 and Formate via Photoredox Catalysis. ACS Catal. 2023, 13, 2149–2155. 10.1021/acscatal.2c06377. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Xu P.; Xu H.; Wang S.; Hao T.-Z.; Yan S.-Y.; Guo D.; Zhu X. Transition-Metal Free Oxidative Carbo-Carboxylation of Alkenes with Formate in Air. Org. Chem. Front. 2023, 10, 2013–2017. 10.1039/D3QO00126A. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Xu C.-W.; Yan S.-Y.; Xu H.; Wang S.; Gu L.-Q.; Xu P.; Yin L.; Zhu X. Photoredox-Neutral Deoxygenative Carboxylation of Acylated Alcohols with Tetrabutylammonium Oxalate. ACS Catal. 2024, 14, 11967–11973. 10.1021/acscatal.4c03396. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Xu P.; Jiang H.-Q.; Xu H.; Wang S.; Jiang H.-X.; Zhu S.-L.; Yin L.; Guo D.; Zhu X. Photocatalytic Deuterocarboxylation of Alkynes with Oxalate. Chem. Sci. 2024, 15, 13041–13048. 10.1039/D4SC03586K. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang X.-Y.; Xu P.; Liu W.-W.; Jiang H.-Q.; Zhu S.-L.; Guo D.; Zhu X. Divergent Defluorocarboxylation of α-CF3 Alkenes with Formate via Photocatalyzed Selective Mono- or Triple C–F Bond Cleavage. Sci. China Chem. 2024, 67, 368–373. 10.1007/s11426-023-1731-x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Xu P.; Liu W.-W.; Hao T.-Z.; Liu Y.-Q.; Jiang H.-X.; Xu J.; Li J.-Y.; Yin L.; Zhu S.-L.; Zhu X. Formate and CO2 Enable Reductive Carboxylation of Imines: Synthesis of Unnatural α-Amino Acids. J. Org. Chem. 2024, 89, 9750–9754. 10.1021/acs.joc.3c02887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Obniska J.; Chlebek I.; Kamiński K. Synthesis and Anticonvulsant Properties of New Mannich Bases Derived from 3,3-Disubstituted Pyrrolidine-2,5-diones. Part IV. Arch. Pharm. Chem. Life Sci. 2012, 345, 713–722. 10.1002/ardp.201200092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monge A.; Aldana I.; Alvarez T.; Font M.; Santiago E.; Latre J. A.; Bermejillo M. J.; Lopez-Unzu M. J.; Fernandez-Alvarez E. New 5H-Pyridazino[4,5-b]indole Derivatives. Synthesis and Studies as Inhibitors of Blood Platelet Aggregation and Inotropics. J. Med. Chem. 1991, 34, 3023–3029. 10.1021/jm00114a010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ladduwahetty T.; MacLeod A. M.. Pyridazino-Indole Derivatives. US 5693640, 1997.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available in the Supporting Information of this article.