Abstract

1. Active Cl- currents were studied in short-circuited toad skin epithelium in which the passive voltage-activated Cl- current is zero. Under visual control double-barrelled microelectrodes were used for impaling principal cells from the serosal side, or for measuring the pH profile in the solution bathing the apical border. 2. The net inward (active) 36Cl- flux of 27 +/- 8 pmol s-1 cm-2 (16) (mean +/- S.E.M (number of observation)) was abolished by 2 mM-CN- (6.3 +/- 3.5 pmol s-1 cm-2 (8)). The active flux was maintained in the absence of active Na+ transport when the latter was eliminated by either 100 microM-mucosal amiloride, replacement of mucosal Na+ with K+, or by 3 mM-serosal ouabain. 3. In Ringer solution buffered by 24 mM-HCO3- -5% CO2 mucosal amiloride reversed the short circuit current (ISC). The outward ISC was maintained when gluconate replaced mucosal Cl-, and it was reversibly reduced in CO2-free 5 mM-Tris-buffered Ringer solution (pH = 7.40) or by the proton pump inhibitor oligomycin. These observations indicate that the source of the outward ISC is an apical proton pump. 4. Amiloride caused principal cells to hyperpolarize from a basolateral membrane potential, Vb, of -73 +/- 3 (22) to -93 +/- 1 mV (26), and superfusion with CO2-free Tris-buffered Ringer solution induced a further hyperpolarization (Vb = -101 +/- 1 mV (26)) which could be blocked by Ba2+. The CO2-sensitive current changes were null at Vb = EK (potassium reversal potential, -106 +/- 2 mV (55)) implying that they are carried by K+ channels in the basolateral membrane. Such a response cannot account for the inhibition of the outward ISC which by default seems to be located to mitochondria-rich (MR) cells. 5. In the absence of mucosal Cl- a pH gradient was built up above MR cells with pH = 7.02 +/- 0.04 (42) and pH increasing to 7.37 +/- 0.02 (10) above principal cells (pH = 7.40 in bulk solution buffered by 0.1 mM-Tris). This observation localizes a proton pump to the apical membrane of MR cells. Using the integrated diffusion equation it was shown that the measured external pH gradient would account within an order of magnitude for measured currents. 6. Standing gradients of protons were eliminated in the presence of mucosal Cl- suggesting that active uptake of Cl- is associated with the exit of base equivalents across the apical membrane of MR cells.(ABSTRACT TRUNCATED AT 400 WORDS)

Full text

PDF

Selected References

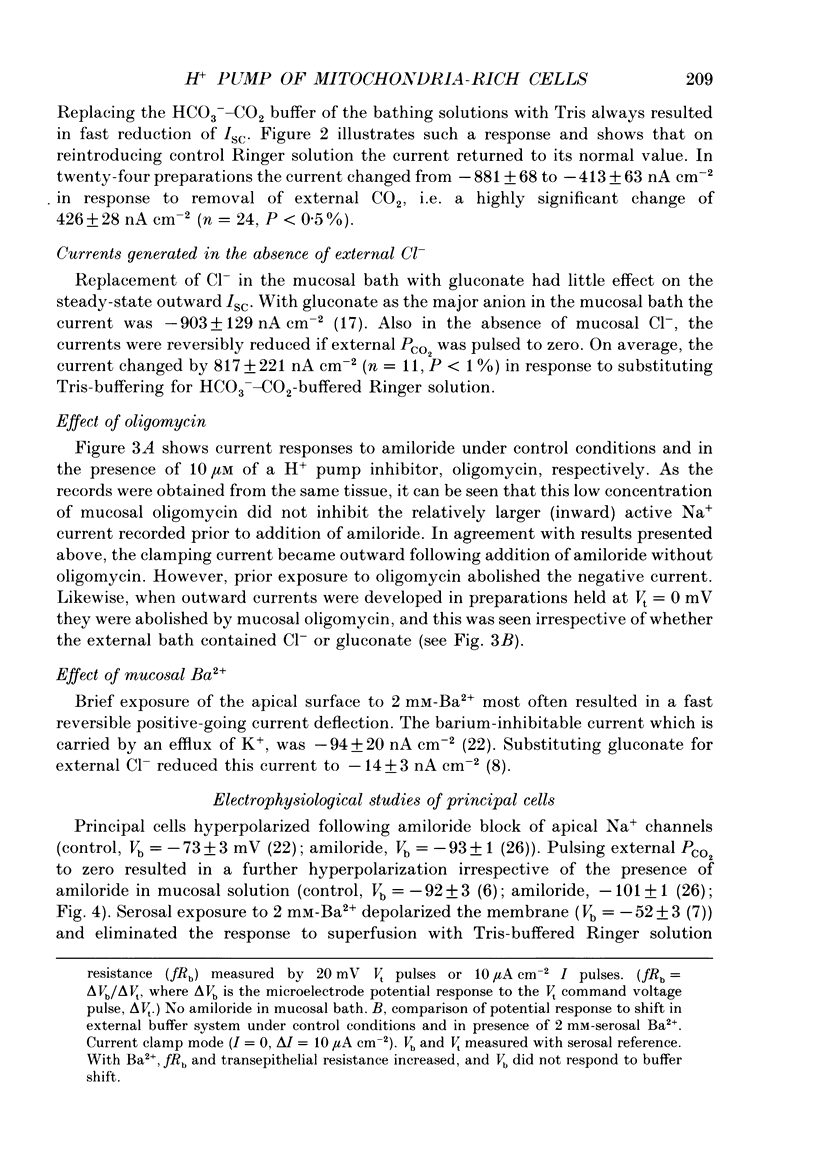

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Andersen O. S., Silveira J. E., Steinmetz P. R. Intrinsic characteristics of the proton pump in the luminal membrane of a tight urinary epithelium. The relation between transport rate and delta mu H. J Gen Physiol. 1985 Aug;86(2):215–234. doi: 10.1085/jgp.86.2.215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beauwens R., Beaujean V., Zizi M., Rentmeesters M., Crabbé J. Increased chloride permeability of amphibian epithelia treated with aldosterone. Pflugers Arch. 1986 Dec;407(6):620–624. doi: 10.1007/BF00582642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berman D. M., Soria M. O., Coviello A. Reversed short-circuit current across isolated skin of the toad Bufo arenarum. Pflugers Arch. 1987 Aug;409(6):616–619. doi: 10.1007/BF00584662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruus K., Kristensen P., Larsen E. H. Pathways for chloride and sodium transport across toad skin. Acta Physiol Scand. 1976 Mar;97(1):31–47. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-1716.1976.tb10233.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christoffersen C. R., Skibsted L. H. Calcium ion activity in physiological salt solutions: influence of anions substituted for chloride. Comp Biochem Physiol A Comp Physiol. 1975 Oct 1;52(2):317–322. doi: 10.1016/s0300-9629(75)80094-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ehrenfeld J., Garcia-Romeu F. Coupling between chloride absorption and base excretion in isolated skin of Rana esculenta. Am J Physiol. 1978 Jul;235(1):F33–F39. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.1978.235.1.F33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ehrenfeld J., Garcia-Romeu F., Harvey B. J. Electrogenic active proton pump in Rana esculenta skin and its role in sodium ion transport. J Physiol. 1985 Feb;359:331–355. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1985.sp015588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ehrenfeld J., Lacoste I., Harvey B. J. The key role of the mitochondria-rich cell in Na+ and H+ transport across the frog skin epithelium. Pflugers Arch. 1989 May;414(1):59–67. doi: 10.1007/BF00585627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emilio M. G., Machado M. M., Menano H. P. The production of a hydrogen ion gradient across the isolated frog skin. Quantitative aspects and the effect of acetazolamide. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1970 Jun 2;203(3):394–409. doi: 10.1016/0005-2736(70)90180-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erlij D. Salt transport across isolated frog skin. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 1971 Aug 20;262(842):153–161. doi: 10.1098/rstb.1971.0086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- García Romeu F., Salibián A., Pezzani-Hernádez S. The nature of the in vivo sodium and chloride uptake mechanisms through the epithelium against sodium and of bicarbonate against chloride. J Gen Physiol. 1969 Jun;53(6):816–835. doi: 10.1085/jgp.53.6.816. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katz U., Larsen E. H. Chloride transport in toad skin (Bufo viridis). The effect of salt adaptation. J Exp Biol. 1984 Mar;109:353–371. doi: 10.1242/jeb.109.1.353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kristensen P. Chloride transport across isolated frog skin. Acta Physiol Scand. 1972 Mar;84(3):338–346. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-1716.1972.tb05185.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larsen E. H. Chloride transport by high-resistance heterocellular epithelia. Physiol Rev. 1991 Jan;71(1):235–283. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1991.71.1.235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larsen E. H., Rasmussen B. E. Chloride channels in toad skin. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 1982 Dec 1;299(1097):413–434. doi: 10.1098/rstb.1982.0141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larsen E. H., Ussing H. H., Spring K. R. Ion transport by mitochondria-rich cells in toad skin. J Membr Biol. 1987;99(1):25–40. doi: 10.1007/BF01870619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Machen T., Erlij D. Some features of hydrogen (ion) secretion by the frog skin. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1975 Sep 16;406(1):120–130. doi: 10.1016/0005-2736(75)90047-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosen S., Friedley N. J. Carbonic anhydrase activity in Rana pipiens skin: biochemical and histochemical analysis. Histochemie. 1973 Jul 19;36(1):1–4. doi: 10.1007/BF00310114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steinmetz P. R. Cellular organization of urinary acidification. Am J Physiol. 1986 Aug;251(2 Pt 2):F173–F187. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.1986.251.2.F173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Willumsen N. J., Larsen E. H. Membrane potentials and intracellular Cl- activity of toad skin epithelium in relation to activation and deactivation of the transepithelial Cl- conductance. J Membr Biol. 1986;94(2):173–190. doi: 10.1007/BF01871197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ZADUNAISKY J. A., CANDIA O. A., CHIARANDINI D. J. THE ORIGIN OF THE SHORT-CIRCUIT CURRENT IN THE ISOLATED SKIN OF THE SOUTH AMERICAN FROG LEPTODACTYLUS OCELLATUS. J Gen Physiol. 1963 Nov;47:393–402. doi: 10.1085/jgp.47.2.393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]