Summary

In recent years, photocatalytic materials with a nanofiber-like morphology have garnered a surge of academic attention due to their distinctive properties, including an expansive specific surface area, a considerable high aspect ratio, a pronounced resistance to agglomeration, superior electron survivability, and robust surface activity. Consequently, the synthesis of photocatalytic nanofiber materials through various methodologies has drawn considerable attention. The electrospinning technique has been established as a prevalent method for fabricating nanofiber-structured materials, owing to its advantageous properties, including the ability for mass production and the assurance of high continuity. This review focuses on metal oxide semiconductor-based materials, which are crucial components of photocatalysts. We summarize several recent studies that explore morphology modulation, surface modification, element doping, and composite construction using uniaxial and coaxial electrospinning techniques. Finally, we present potential approaches for constructing high-activity photocatalytic systems through electrospinning technique.

Subject areas: Catalysis, Materials science, Energy materials

Graphical abstract

Catalysis; Materials science; Energy materials

Introduction

Historically, the earliest catalysts consisted of three-dimensional bulk materials or particle-like structures, typically composed of metals, oxides, or other active substances in a solid state. Although these materials demonstrated certain catalytic capabilities, they were inherently limited by their large particle size and restricted surface area, constraining their catalytic activity and selectivity.1 To overcome these issues, research has increasingly focused on modulating catalyst morphology—by reducing particle size, developing two-dimensional sheets, and creating one-dimensional nanostructures like nanofibers.2,3,4 One-dimensional nanofibers and nanowires, with their high surface area-to-volume ratios arising from their extreme extensiveness in one dimension and thinness in the other two dimensions, have shown remarkable potential in improving catalyst performance by enhancing selectivity, reducing side reactions, and promoting efficient electron transport.5 Consequently, the synthesis of photocatalytic nanofiber materials has attracted considerable attention due to their unique properties, including extensive specific surface area, high aspect ratios, significant resistance to agglomeration, enhanced electron survivability, and robust surface activity, and related works have thus been widely researched to facilitate the exploration of diverse methodologies aimed at optimizing their production.6

Among the various techniques for preparing one-dimensional nanofibers, such as templating, sol-gel, and self-assembly, electrospinning stands out due to its unique advantages, including the ability to modulate the specific surface area of the material, feasibility for mass production, and simplicity of the apparatus, which requires only a syringe, a receiver, and a high-voltage power supply, as shown in Figure 1.7,8

Figure 1.

Schematic diagram of the electrospinning device

The electrospinning technique does not require complex equipment or substantial expense, yet it facilitates the rapid generation of nanofibers within a short time frame, simultaneously ensuring that the fibers exhibit an exceptionally high surface area-to-volume ratio, thus guaranteeing its practicability and scalability. Electrospinning is rapidly differentiating from the single-fluid electrospinning to bi-fluid coaxial and side-by-side electrospinning, and to tri-fluid coaxial, Janus, and their combined electrospinning processes.9,10,11,12,13,14 Meanwhile, electrospinning is also frequently combined with other traditional techniques such as electrospraying and solvent casting for expanding its capability of creating nanofibers.15,16,17 However, the most popular electrospinning processes are uniaxial and coaxial processes, as shown in Figure 2, which have been broadly employed for producing metal oxide semiconductor-based photocatalysts. Relatively speaking, uniaxial electrospinning is limited in producing more complex structures when compared with the coaxial electrospinning. When compared with uniaxial electrostatic spinning, the most notable distinction is that the coaxial needle comprises two parts. One part of the apparatus is loaded with the shell liquid, whereas the other part is loaded with the core liquid. On the other hand, to construct photocatalytic systems with enhanced activities, many modulation strategies have been developed, such as surface modification, element doping, and composite construction. By coaxial spinning or adding additional components into the spinning solution, the above-mentioned modulations can be easily realized through an in situ process.18

Figure 2.

(A and B) Comparison of single-axis and coaxial needles

Based on the above investigation, this review provides a systematic survey and summary of current research on the preparation of highly active photocatalytic systems using electrospinning technology, focusing primarily on enlarging the specific surface area of the materials by modulating their morphology, modifying some functional groups or metal particles on their surface, doping some elements in their structure, and introducing other semiconductor materials to construct composites. At last, we propose a promising strategy for constructing photocatalytic systems with enhanced charge separation properties and catalytic performance through coaxial electrospinning technology.

Morphology modulation

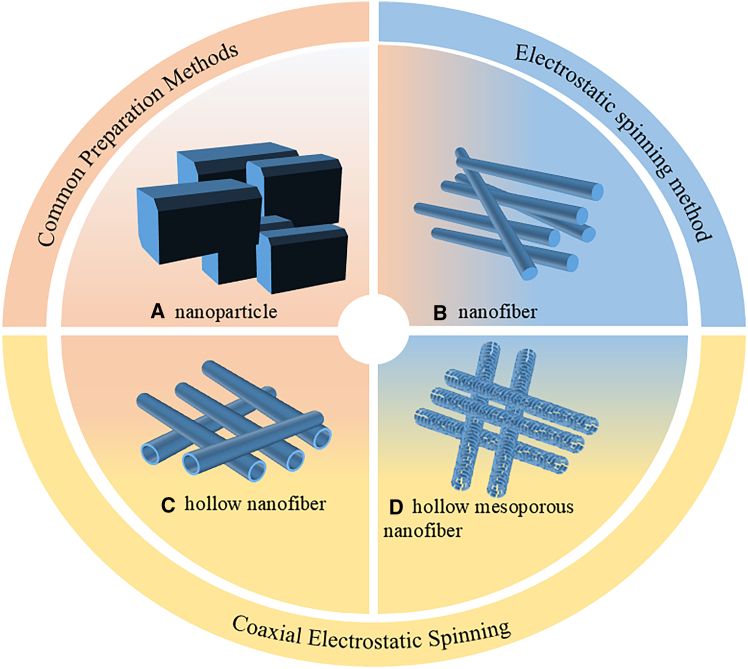

The specific surface area of bulky, large-sized materials is inherently limited, as depicted in Figure 3A, resulting in fewer surface-active sites and reduced contact with reactants. To address this issue, nanofibers produced via electrospinning, as shown in Figure 3B, have been widely researched for their ability to increase the specific surface area.19 By adjusting parameters such as solution viscosity, voltage, and flow rate, it is possible to create materials with varying pore sizes. Among these techniques, coaxial electrospinning (illustrated in Figure 3C) produces hollow or core-shell fibers, which further enhance performance by increasing surface area and facilitating efficient carrier migration.20,21 This structure improves charge separation and reduces electron-hole recombination due to shortened migration pathways. Additionally, hollow porous nanofibers, shown in Figure 3D, provide even greater advantages with their porous structure, introducing additional channels and active sites.22 This configuration promotes reactant diffusion, enhances charge carrier separation, and suppresses electron-hole recombination, resulting in significantly improved photocatalytic efficiency.

Figure 3.

Comparison of the different morphology, including nanoparticle from common preparation methods (A), nanofiber (B), hollow nanofiber (C) and hollow mesoporous nanofiber (D) from electrospinning method.

A number of studies have employed uniaxial electrostatic spinning to fabricate fibrous photocatalysts with a high specific surface area. For example, Juncai Lu et al.23 prepared ZnWO₄ nanofibers using uniaxial electrospinning, achieving a specific surface area of 110 m2 g⁻1, which was significantly higher than the 75 m2 g⁻1 of irregular ZnWO₄ nanoparticles prepared by the same method. This increase in surface area, attributed to the electrospinning process, also led to a higher density of defects and active sites, enhancing the material’s catalytic efficiency. As a result, the ZnWO₄ nanofibers degraded 70% of RhB (10 mg/L) within 45 min, compared with 70 min required by the nanoparticles. The enhanced surface area and accelerated charge separation due to electrospinning are also crucial for improving hydrogen production technologies.

Ling Wang et al.24 synthesized MgTiO₃ nanofibers with a specific surface area of 22.62 m2 g⁻1, about 3.5 times greater than that of MgTiO₃ particles (6.3 m2 g⁻1) prepared via sol-gel and calcination. The high aspect ratio of the nanofibers enhanced light absorption and facilitated rapid migration of photogenerated charge carriers, reducing electron-hole recombination and improving charge transport. This led to a hydrogen production rate of 0.33 mmol g⁻1·h⁻1, four times higher than that of MgTiO₃ particles. The porous structure between nanofibers further enhanced reactant conversion and hydrogen production efficiency.

Shama Perween et al.25 produced ZnTiO₃ nanopowders via uniaxial electrospinning, starting with calcination to form ZnTiO₃ powder, followed by sol formation with a surfactant, and finally electrospinning. The specific surface area of the electrospun ZnTiO₃ (24.47 m2 g⁻1) was significantly higher than that of the sol-gel-prepared sample (1.05 m2 g⁻1). The increased surface area and nanoporous structure, formed by removing organic components during synthesis, contributed to a 1.7-fold improvement in the phenol degradation rate under visible light, showcasing superior photocatalytic performance.

Some studies have utilized coaxial electrospinning to create hollow fiber structures, aiming to further enhance the material’s specific surface area. For instance, Juran Kim et al.26 utilized coaxial electrospinning to fabricate TiO₂ hollow nanofibers, where the transition from solid to hollow structures was controlled by varying the core solution flow rate. When the flow rate was set to zero, the resulting solid fibers had a specific surface area of 16.01 m2 g⁻1, comparable to fibers produced by uniaxial spinning. However, as the core solution flow increased, the fibers transformed into hollow nanofibers, achieving a maximum surface area of 51.28 m2 g⁻1. This hollow architecture, characterized by a larger internal cavity, significantly increased the material’s surface active sites, thereby enhancing its adsorption capacity and catalytic performance. The unique layered structure also facilitated greater exposure of catalytic sites to reactants, allowing for more efficient diffusion and interaction. As a result, the NO removal rate within 60 min reached 66.2%, more than double the 31.2% achieved by the solid fibers. This improvement is largely due to the increased surface area and improved electron transport across the hollow structure, which enhances the availability of reactive species at the active sites.

Shudan Li et al.27 employed a similar coaxial electrospinning method, using air as the core material to produce hollow, mesoporous LaFeO₃ nanofibers with a belt-like structure. The hollow fibers, with their high porosity, differed markedly from the densely packed uniaxial fibers typically formed after calcination. The hollow structure not only provided a larger surface area but also improved light utilization by enhancing the penetration and scattering of light within the fiber matrix, increasing the efficiency of photocatalytic reactions. Moreover, the belt-like structure of the nanofibers facilitated greater contact between the catalyst and the reaction substrate, improving mass transfer. The smaller crystalline domains further contributed to the reduction of photogenerated electron-hole recombination by shortening the distance electrons and holes must travel to reach the surface, thus optimizing the photocatalytic activity. These structural advantages resulted in a methylene blue (MB) degradation efficiency of 59.79% within 2 h, demonstrating the efficacy of hollow, mesoporous fibers in enhancing both light absorption and catalytic performance.

Both uniaxial electrostatic spinning and coaxial electrostatic spinning are feasible methods in regulating the morphology of materials, thereby enhancing their specific surface area. Herein, a summary of some related works is presented as shown in Table 1, including the related spinning conditions, carrier polymers used, and catalytic efficiency.

Table 1.

Morphological modulation using electrostatic spinning

| Photocatalyst | Spinning conditions | Solvents | Carrier polymers | Photocatalytic testing | Test conditions | Activity results | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ZnWO4 | Voltage 15 kV Distance (to needle tip) 15 cm |

DI | PVP | Degrading RhB | RhB solution at 10 mg/L | 70% within 45 min | Lu et al.23 |

| MgTiO3 | Voltage 12 kV Distance 12 cm |

CH3COOH, CH3OH | PVP | Hydrogen production | 300-W Xe lamp | 0.33 mmol g−1·h−1 | Wang et al.24 |

| ZnTiO3 | Voltage 10 kV Distance 12 cm |

CH3COOH | PVA | Degrading C6H6O | Visible light (output power 100 W) | 70% within 1 h | Perween et al.25 |

| TiO2 | Voltage 15 kV Distance 12 cm |

DMF, CH3COOH, C2H5OH | PVP | Degrading RhB | 200-W Xe light RhB solution at 20 mg/L |

99% within 90 min | Kim et al.26 |

| LaFeO3 | Pushing speed 0.4 mL h−1 Distance 12 cm |

CH3COOH, C2H5OH | PVP | Degrading MB | 125-W Xe light MB solution at 5 mg/L |

59.8% within 120 min | Li et al.27 |

| BiVO4 | Voltage 16 kV Distance 14 cm |

DMF, CH3COOH, C2H5OH | PVP | Redox Cr(VI) | Cr(VI) solution concentration 10 mg/L | 95.3% within 80 min | Lv et al.28 |

| ZnO | Voltage 17 kV Distance 11 cm |

DMF | PAN | Degrading MB | MB solution concentration 15 μM | 99% within 60 min | Pantò et al.29 |

| WO3 | Voltage 28 kV Distance 15 cm |

DMF, C2H5OH | PVP | Degrading C6H6O | C6H6O solution at 20 mg/L | 2.87 mg L−1·h−1 | Tong et al.30 |

DI, deionized water; PVP, polyvinyl pyrrolidone; PVA, polyvinyl alcohol; PAN, polyacrylonitrile; DMF, dimethyl formamide.

Surface modification

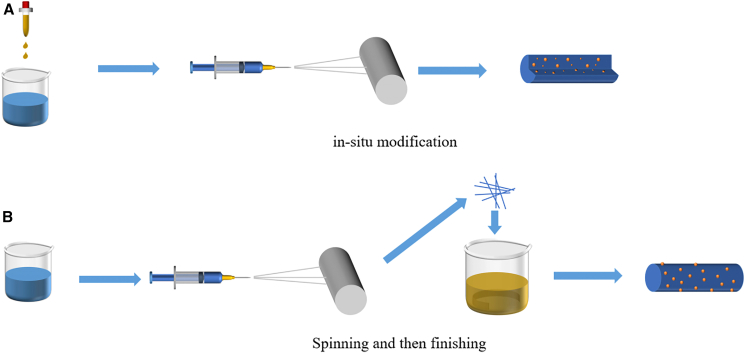

Surface modification of groups, molecules, or metal particles is a widely used method for enhancing charge separation, light absorption, or redox capacity of photocatalysts.31 As illustrated in Figure 4, introducing raw materials into the spinning solution is a feasible method for surface modification.32,33 Besides, in the postmodification method, the fiber-like structure of the catalyst prevents agglomeration, which is also beneficial for subsequent modifications.

Figure 4.

(A and B) Material surface modification methods

Several studies have demonstrated the critical role of electrospinning in tailoring photocatalytic materials by facilitating the incorporation and precise distribution of modifying agents during synthesis. For instance, Chunqie Han and colleagues34 synthesized Ag/Ga2O3 photocatalysts using electrospinning, introducing Ag nanoparticles via in situ surface modification. Although the specific surface area decreased from 19.6 m2/g (pure Ga2O3) to 14.3 m2/g (Ag/Ga2O3), the photocatalytic hydrogen production increased 6-fold. This improvement was driven by the structural benefits from electrospinning, which ensured uniform Ag nanoparticle distribution, enhancing charge separation and reducing electron-hole recombination. Additionally, the plasmonic effects of Ag nanoparticles expanded light absorption into the visible spectrum, compensating for the reduced surface area and boosting photocatalytic activity.

Similarly, Ye Shengjun et al.35 used electrospinning to incorporate multi-walled carbon nanotubes (MWCNTs) into BiVO4 nanofibers. The MWCNTs formed a conductive network that enhanced electron mobility and minimized recombination. Although surface area data were not provided, the structural changes reduced the band gap from 2.35 to 2.16 eV, leading to improved visible light absorption and a 2-fold increase in the photocatalytic degradation of oxytetracycline.

Seonyoung Jo and colleagues36 applied electrospinning to create TiO2 nanofibers modified with perovskite quantum dots (PQDs). The resulting mesoporous structure increased the interaction surface with water, improving hydrophilicity. The uniform distribution of PQDs broadened the light absorption spectrum and improved charge separation, resulting in over 90% degradation of rhodamine B in 1 h, far outperforming commercial TiO₂ (P25).

Several studies have effectively demonstrated the advantages of coaxial electrospinning in enhancing the photocatalytic properties of materials by encapsulating functional modifiers within the outer or inner layers of host nanofibers, as illustrated in Figure 5. For instance, Labeesh Kumar et al.37 used coaxial electrospinning to fabricate hollow Au@TiO2 porous nanofibers with gold nanoparticles encapsulated inside. The porous and hollow structure, created by electrospinning, allowed the catalytic sites (Au nanoparticles) to remain highly active while being protected by the TiO2 shell. Even though the surface area after calcination did not increase dramatically, the hollow structure ensured that the majority of catalytic sites remained accessible, leading to excellent catalytic efficiency and recyclability for the reduction of 4-nitrophenol and Congo red dye.

Figure 5.

Surface modification structure of coaxial spinning material

Similarly, Xiangqian Guo et al.38 used coaxial electrospinning to synthesize Cu-loaded SrTiO3 nanofibers aimed at enhancing the photocatalytic reduction of CO2 to CH3OH. The electrospinning technique facilitated a uniform distribution of Cu across the nanofibers, improving charge separation and electron transfer from SrTiO3 to Cu. Despite the surface area remaining around 10 m2/g, one-dimensional structure and surface modification with Cu significantly enhanced the photocatalytic efficiency. The methanol yield peaked at 8.08 μmol/g/h when 8% Cu was incorporated, highlighting how electrospinning improved charge dynamics and stability, compensating for the relatively low surface area.

Ruyi Xie et al.39 employed coaxial electrospinning to fabricate flexible CQDs-Bi20TiO32/PAN nanofiber membranes. The CQDs-Bi20TiO32 were uniformly anchored to the nanofiber surfaces, while the PAN fibers provided flexibility. Although the surface area increased only modestly (from 7.53 m2/g to 11.18 m2/g), the hierarchical structure of the electrospun fibers, with both macro- and mesoporous features, boosted photocatalytic activity, enabling effective degradation of the herbicide isoproturon under visible light. The robust structure also enhanced the catalyst’s recyclability and durability, critical for environmental remediation applications.

Electrospinning plays a very important role in the surface modification of materials. Both uniaxial and coaxial electrospinning can prepare materials simply and quickly, greatly improving the efficiency of material synthesis. In particular, coaxial electrospinning technology can precisely encapsulate the surface of materials. To summarize the application of electrospinning in surface modification, we have compiled some research and listed it in Table 2.

Table 2.

Surface modification using electrostatic spinning

| Photocatalyst | Spinning conditions | Solvents | Carrier polymers | Photocatalytic testing | Test conditions | Activity results | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ag/Ga2O3 | Voltage +19, −6 kV | C2H5OH | PVP | Hydrogen production | 300-W Xe light | 65.7 mmol within 2 h | Han et al.34 |

| MWCNT/BiVO4 | Voltage 15–20 kV Distance 10–15 cm |

C2H5OH | PVP | Degrading OTC | 500-W Xe light OTC solution at 10 mg/L |

88.8% within 60 min | Ye et al.35 |

| PQDs-modified TiO2 | Voltage 13 kV Distance 12 cm |

C2H5OH | PVP | Degrading RhB | RhB solution at 20 ppm | 97.9% within 2 h | Jo et al.36 |

| Au/TiO2 | Voltage 25 kV Distance 20 cm |

DMF | PVP | Borohydride reduction of 4-NP | 4-NP solution at 0.2 mM | 99% within 20 min | Kumar et al.37 |

| Cu-loaded SrTiO3 | Voltage +18, −3 kV Distance 15 cm |

DMF | PVP | Redox CO2 | 300-W Xe light | 8.08 μmol g−1·h−1 | Guo et al.38 |

| CQDs-Bi20TiO32/PAN | Voltage 20 kV Distance 20 cm |

DMAc | PAN | Degrading isoproturon | 500-W Xe light Isoproturon solution at 15 mg/L |

90.4% within 3 h | Xie et al.39 |

| Bi/BixTiO-TiOyz2/CNFs | Voltage 25 kV Distance 15 cm |

CH3COOH, C2H5OH, DMF | PAN | Degrading RhB | 300-W Xe light RhB solution at 10 mg/L |

97% within 30 min | Yao et al.40 |

| Cu0/S-doped TiO2 | Voltage 18 kV Distance 15 cm |

CH3COOH, C2H5OH | PVP | Hydrogen production | Magnetic stirring under sunlight | 91% within 90 min | Yousef et al.41 |

| Fe2O3-TiO2 | Voltage 15 kV Distance 15 cm |

DMF, CH3COOH, C2H5O | PVP | Degrading CR | Congo red aqueous solution at 10 mg/L | 78.8% within 90 min | Sheikh et al.42 |

OTC, oxytetracycline; DMAc, N,N-dimethylacetamide; CR, congo red.

Element doping

Modulating the structure of the materials through doping element is also a feasible approach for improving their photocatalytic activities as the dopants can introduce some good properties, including promoting charge separation, providing activity cites, and extending light absorption.43,44

Several studies have demonstrated the successful in situ doping of nanofibers by introducing a doping source into the spinning solution, followed by electrostatic spinning to create doped nanostructures with enhanced photocatalytic properties.45 The use of electrospinning, whether uniaxial or coaxial, allows for precise control over the incorporation of dopants, leading to improved material properties such as increased surface area, extended light absorption, and enhanced charge carrier dynamics. For instance, Shaoju Jian et al.46 fabricated La-doped ZnO nanofibers using electrospinning, achieving 94.31% degradation efficiency for rhodamine B under visible light. La doping introduced oxygen vacancies, improving charge separation and extending the material’s light absorption into the visible spectrum. The high surface area and porosity of the electrospun nanofibers enhanced pollutant interaction, reducing recombination and boosting overall photocatalytic performance.

Yan Chen et al.47 synthesized (N,F)-co-doped TiO2-δ nanofibers via electrospinning, achieving a specific surface area of 24.27 m2/g, nearly three times that of commercial TiO2. The electrospinning technique allowed the formation of mesoporous nanofibers, enhancing both light absorption and charge separation. Nitrogen and fluorine doping introduced oxygen vacancies, crucial for extending light absorption into the visible spectrum and improving electron-hole separation, thus preventing recombination. This led to significant improvements in photocatalytic efficiency, with degradation rates of 27.2% for rhodamine B, 40.9% for methylene blue, and 31% for Cr(VI) within 60 min, far outperforming commercial TiO2.

Wei Qi et al.48 developed Zr/Ag co-doped TiO₂ nanofibers through electrospinning, creating a core-shell structure that optimized photocatalytic performance. Zr stabilized the anatase phase of TiO₂, while Ag nanoparticles provided plasmonic effects, extending light absorption into the visible range. The synergistic heterojunction between Zr and Ag further improved charge carrier mobility and electron-hole separation. This resulted in a 12-fold increase in the degradation rate constant for Congo red dye compared with undoped TiO₂.

Some studies have indicated that introducing dopants into the core or shell layer while constructing a heterojunction structure using coaxial electrospinning is a viable strategy to enhance the performance of the product. Sangmo Kang et al.49 used this technique to fabricate Ag⁺-doped rGO/TiO₂ core-shell nanofibers, which exhibited a 25-fold increase in the photocatalytic reduction of CO2 to CH4 compared with undoped TiO₂ nanofibers. This enhancement was due to Ag nanoparticles acting as electron traps, minimizing recombination, while the rGO layer facilitated rapid electron transport thanks to its high conductivity. The core-shell structure also provided a larger surface area for photon absorption and improved interaction with the reactants.

In a notable study by Zi Zhu et al.,50 Ce-doped TiO₂/graphite/g-C₃N₄ heterojunctions were synthesized using a tri-coaxial electrospinning technique. This method allowed for the uniform incorporation of Ce into the TiO₂ matrix, resulting in a hybrid material with superior photocatalytic hydrogen evolution rates. The coaxial electrospinning process played a critical role in achieving the precise doping required for the efficient separation of photogenerated charge carriers, as well as optimizing the interaction between TiO₂, Ce, and the other components in the heterojunction. The polarization effect of the graphite layer further strengthened the internal electric field, enhancing charge transfer and suppressing recombination. The Ce-doped TiO₂ nanofibers prepared by electrospinning exhibited a remarkable hydrogen production rate, four times higher than that of undoped TiO₂, demonstrating the potential of this technique in producing high-performance photocatalytic materials.

The doping of different materials plays an important role in improving the photocatalytic performance, and a summary of related works by electrostatic spinning methods is presented in Table 3.

Table 3.

Doping using electrostatic spinning

| Photocatalyst | Spinning conditions | Solvents | Carrier polymers | Photocatalytic testing | Test conditions | Activity results | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| La-doped ZnO | Voltage 15 kV Distance 20 cm |

DMF | PAN | Degrading RhB | 350-W Xe light RhB solution at 10 mg/L |

94.31% within 510 min | Jian et al.46 |

| (N,F) co-doped TiO2-δ | Voltage 18 kV | DMF | PAN | Degrading MB | 5-W LED light | 40.9% within 60 min | Chen et al.47 |

| Zr/Ag co-doped (TiO2) | Voltage 15 kV Distance 12 cm |

C2H5OH | PVP | Degrading CR | 300-W Xe light CR solution at 30 mg/L |

99.3% within 120 min | Qi et al.48 |

| Ag/TiO2 | Voltage 15 kV Distance 8 cm |

DMF, CH3COOH | PVP | Redox CO2 | 500-W Xe light | 4.301 μmol g−1 in 7 h | Kang et al.49 |

| Ce-doped TiO₂/graphite/g-C₃N₄ | – | DMF, C2H5OH | PVP | Hydrogen -production | 300-W Xe light | 3.05 mmol g−1·h−1 | Zhu et al.50 |

| Sr-doped Bi4O5Br2/Bi2MoO6 | Voltage 20 kV Distance 18 cm |

DMF | PAN | Degrading 4-CP | 300-W visible LED light 4-CP solution at 10 mg/L |

98.7% within 80 min | Pan et al.51 |

| Fe-doped LaMnO3 | Voltage +12, −2 kV Distance 15 cm |

DMF | PVP | Hydrogen production | 300-W Xe light | 767.71 μmol g−1·h−1 | Zhan et al.52 |

| Sc-doped Bi3TiNbO9 | Voltage 20 kV Distance 15 cm |

C2H5OH, CH3COOH | PVP | Degrading RhB | RhB solution at 20 mg/L | 98.55% within 120 min | Song et al.53 |

| C-ZnO | Voltage 15 kV Distance 15 cm |

DMF | PAN | Degrading caffeine | 300-W solar light Caffeine solution at 30 ppm |

80.4% within 120 min | Gadisa et al.54 |

| Bi0.9Gd0.07La0.03FeO3 | Voltage 15 kV Distance 15 cm |

DMF | PVP | Degrading MB | 300-W Xe light MB solution at 20 mg/L |

89% within 90 min | Mani et al.55 |

| Ag/Fe-HAP@CA | Voltage 18 kV Distance 15 cm |

CH3COCH3 | CA | Degrading MB | MB solution at 10 mg/L | Over 90% within 2 h | Shalan et al.56 |

| Fe-doped TiO2 | Voltage 20 kV Distance 20 cm |

C2H5OH | PVP | Degrading MB | 500-W Xe light MB solution at 20 mg/L |

38.3% within 90 min | Na et al.57 |

| Sn4+-doped BiFeO3 | Voltage 17 kV Distance 14 cm |

DMF | PAN | O2 evolution | 300-W Xe light | 516.4 mmol g−1·h−1 | Ren et al.58 |

| Fe-doped ZnO | Voltage 17.5 kV Distance 10 cm |

DW | PVA | Degrading MB | 50-W Xe light MB solution at 10 mg/L |

Above 80% for 6 h | Liu et al.59 |

| Ta-doped TiO2 | Voltage 13 kV | DI, C2H5OH | PVP | Degrading MB | 12-W UV lamp MB solution at 20 μM |

Above 90% for 4 h | Singh et al.60 |

| N-doped In2O3 | Voltage 10 kV Distance 10 cm |

DMF | PVP | Degrading RhB | 150-W Xe light RhB solution at 10 mg/L |

97% within 180 min | Lu et al.61 |

LED, light-emitting diode.

Composite construction

Semiconductor photocatalysts with a wide band gap often face the challenge of limited light absorption, whereas those with a narrow band gap are prone to significant charge recombination. Constructing composite system is a feasible method for solving these problems.62 Electrospinning technology can facilitate an in situ combination by simply mixing the raw materials into the spinning solution and can even produce a one-dimensional core-shell structure through coaxial spinning, which enhances the interaction between the composite materials, and thus has been widely researched.63,64

Several studies have employed uniaxial electrospinning techniques to construct composite systems by modifying the spinning solution composition, highlighting the versatility of this method in enhancing photocatalytic performance. Yinyin Ai et al.64,65 prepared a ZnIn₂Se₄/TiO₂ composite via electrospinning, featuring a Z-scheme heterojunction with ZnIn₂Se₄ nanoparticles tightly bonded to TiO₂ nanofibers through Ti-Se interfacial bonds. This strong interface, formed through uniaxial electrospinning, enhances the internal electric field, promoting efficient charge transfer and reducing electron-hole recombination. As a result, the composite achieved a photocatalytic hydrogen evolution rate of 0.11 mmol/g/h, three times higher than bare TiO₂. The Ti-Se bond and internal electric field make this structure particularly effective for hydrogen production and other catalytic applications. Beyond increasing surface area, electrospinning plays a crucial role in optimizing electron transport pathways, improving overall photocatalytic performance.

Similarly, QingHao Li and colleagues synthesized CS/TiO₂/g-C₃N₄ composite nanofibers via electrospinning,66 achieving a Cr(VI) removal rate of over 90% under visible light, a 50% improvement over pure CS. The synergy between g-C₃N₄ and TiO₂ broadened light absorption and enhanced charge separation, key factors that improved the material’s photocatalytic performance. The composite also maintained high stability and activity over multiple cycles, demonstrating the durability imparted by the electrospinning process, making it suitable for real-world applications.

Lu Wang et al.67 used electrospinning to create g-C₃N₄/Nb₂O₅ composite nanofibers, resulting in a specific surface area of 36.18 m2 g⁻1, 1.2 times higher than that of Nb₂O₅ alone. The heterojunction between g-C₃N₄ and Nb₂O₅ effectively reduced the band gap, extending light absorption into the visible spectrum and leading to an RhB degradation efficiency of 98.1% in two hours—nearly double that of Nb₂O₅ nanofibers. The increased surface area, combined with enhanced charge separation, underscores how electrospinning facilitates the creation of highly efficient catalytic materials by improving both structural and electronic properties.

In certain studies, composite fibers with core-shell structures have been constructed using coaxial spinning technology, in which the precursors of the materials are separately placed in the outer shell and inner core, as shown in the Figure 6. For instance, Yang Yaoyao et al.68 prepared AgCl/ZnO-loaded nanofibrous membranes using coaxial electrospinning. The core-shell structure provided by the coaxial technique allowed for the separation of AgCl in the core and ZnO in the shell, enhancing the material’s stability and active site exposure. This architecture facilitated efficient electron-hole separation and charge transport, resulting in a photocatalytic degradation efficiency of 98% for MB within 70 min, with over 95% efficiency retained across five cycles. The structural control offered by coaxial electrospinning was key in improving both the photocatalytic performance and long-term stability of the nanofibers.

Figure 6.

Coaxial electrostatically core-shell-structured nanofiber

Similarly, Mao Yihang et al.69 developed g-C₃N₄/PAN/PANI@LaFeO₃ core-shell nanofibrous membranes using coaxial electrospinning, where the core-shell design played a critical role in enhancing the photocatalytic properties. The LaFeO₃ was deposited in the outer shell, whereas g-C₃N₄ and PAN/PANI were distributed in the core, forming a Z-scheme heterojunction. This configuration promoted efficient charge separation, extended light absorption, and increased pollutant interaction with the active sites. As a result, the membranes achieved high pollutant removal rates, including 97.0% for MB, 94.3% for methyl violet, and 87.6% for ciprofloxacin. The structured design not only boosted photocatalytic efficiency but also ensured strong mechanical integrity and reusability.

In another example, Bin Jiang et al.70 used coaxial electrospinning to synthesize SnO₂@PW12@TiO₂ core-shell nanofibers, forming a complex three-layer structure. The SnO₂ core, PW12 middle layer, and TiO₂ outer shell were strategically designed to create a Z-scheme heterojunction between the layers, which enhanced charge separation and suppressed recombination. This multilayer structure increased the interaction between the active layers and maximized light absorption, leading to a 73.8% degradation of tetracycline within 30 min, compared with 44.8% for SnO₂@TiO₂ fibers without the PW12 layer. The enhanced photocatalytic performance was largely attributed to the efficient charge transfer pathways enabled by the core-shell architecture, highlighting the structural advantages coaxial electrospinning provides.

Electrostatic spinning is typically employed for the rapid fabrication of composite structures comprising diverse materials, as well as the synthesis of core-shell multilayered composite nanofibers. To facilitate rapid access to multilayered composites, we present a synopsis of composite precursor preparation methods and their catalytic activity in Table 4.

Table 4.

Compounding with electrostatic spinning

| Photocatalyst | Spinning conditions | Solvents | Carrier polymers | Photocatalytic testing | Test conditions | Activity results | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ZnIn₂Se₄/TiO₂ | Voltage +15, −5 kV Distance 20 cm |

CH3COOH, C2H5OH | PVP | Hydrogen production | – | 0.11 mmol g−1·h−1 | – |

| CS/g-C3N4/TiO2 | Voltage 15 kV Pushing speed 5 mL h−1 |

CH3COOH | PEO | Redox Cr(VI) | 800-W Xe light Cr(VI) solution 100 mg/L |

90% within 4 h | Li et al.66 |

| g-C3N4/Nb2O5 | Voltage 18 kV Distance 20 cm |

DMF | PVP | Degrading RhB | – | 98.1% within 120 min | Wang et al.67 |

| AgCl/ZnO | Voltage 10 kV Distance 15 cm |

C2H5OH, DI | PVP | Degrading MB | 300-W Xe lamp | 99.70% within 35 min | Yang et al.68 |

| g-C3N4/PAN/PANI@LaFeO3 | Voltage 18 kV Distance 15 cm |

DMF | PAN | Degrading MB | 500-W Xe lamp MB solution at 20 mg/L |

97% within 75 min | Mao et al.69 |

| m-Hal@Ag3PO4/PAN | Voltage +18, −2 kV Distance 15 cm |

DMF | PAN | Degrading ciprofloxacin | 500-W Xe light Ciprofloxacin solution at 15 mg/L |

99.98% within 200 min | Ma et al.71 |

| SnO2@PW12@TiO2 | – | CH3COOH, C2H5OH, DMF | PVP | Degrading TC | 300-W Xe light TC solution at 20 mg/L |

73.8% within 30 min | Jiang et al.70 |

| NaYF4/Yb/Tm/TiO2 | – | C2H5OH, CH3COOH | PVP | Degrading RhB | RhB solution at 0.01 mmol/L | 99.12% within 2 h | Guo et al.72 |

| TiO2/WO3 | Voltage 15 kV Distance 8 cm Pushing speed 1 mL h−1 |

CH3COOH, C2H5OH | PVP | Degrading MO | UV and visible light MO solution was 4 × 10−5 M |

21.6% within 240 min | Odhiambo et al.73 |

| Fe2O3/TiO2 | Voltage 15 kV Distance 15 cm |

CH3COOH, C2H5OH | PVP | Degrading RhB | RhB solution 5 mg/L | 99% within 90 min | Liu et al.74 |

| CoFe2O4/BiOI | Voltage 12 kV Pushing speed 5 μL min−1 |

DMF, C2H5OH | PVP | Degrading RhB | 150- to 300-W Xe light RhB solution 10 mg/L |

97.2% within 90 min | Chang et al.75 |

| PAN/Bi2MoO6/Ti3C2 | Voltage 20 kV Pushing speed 0.01 mm/s |

DMF | PAN | Degrading tetracycline | 300-W Xe light TC solution 15 mg/L |

90.3% within 4 h | Zhang et al.76 |

| TiO2/WO3/C/N | Voltage 20 kV Pushing speed 1 mL h−1 |

CH3COOH, C2H5OH | PVP | Degrading MB | MB solution 12.6 mg/L | 39.4% within 4 h | Odhiambo et al.77 |

| Au/CeO2 | Voltage 20 kV Pushing speed 0.5 mL h−1 |

DMF | PVP | Degrading PhCHO | UV light | 83.3% within 5 h | Li et al.78 |

| g-C3N4/K0.5Na0.5NbO3 | Voltage 18 kV | C2H5OH | PVP | Hydrogen production | 300-W Xe light | 96.3 μmol g−1·h−1 | Zhang et al.79 |

| CuBi2O4/Bi2O3 | Voltage 18 kV Distance 12 cm |

DMF | PVP | Degrading MO | – | 99.2% within 130 min | Yang et al.80 |

| ZnIn2S4/Ag2MoO4 | Voltage 15 kV Distance 15 cm |

DMF, C2H5OH, CH3COOH | – | Degrading ENR | 300-W Xe light ENR solution at 20 mg/L |

100% within 120 min | Li et al.81 |

| ZnFe2O4/Ag/AgBr | Voltage 17–19 kV | DMF | PVP | Degrading RhB | RhB solution at 100 mg/L | 86.3% within 100 min | Sabzehmeidani et al.82 |

| SiO2/Ga2O3 | Voltage 15 kV Distance 20 cm |

DMF | PAN | Degrading RhB | RhB solution 10 mg/L | 98% within 30 min | Du et al.83 |

| BN/Ce2O3/TiO2 | Voltage 1.25 kV/cm Pushing speed 1 mL h−1 |

C2H5OH | PVP | Hydrogen production | 500-W halogen lamp | 850 μmol g−1·h−1 | Ghorbanloo et al.84 |

| W2N/C/TiO-n | Voltage 13 kV Distance 20 cm |

DMF | PAN | Hydrogen production | 300-W Xe light | 3.11 μmol g−1·h−1 | Gong et al.85 |

| ZnO-In2S3 | Voltage 14 kV Distance 14 cm |

DI | PVA | Hydrogen production | 5-W blue LED | 539.5 μmol g−1·h−1·L−1 | Chang et al.86 |

| ZnO/Ti3C2 | Voltage 14 kV Distance 14 cm |

DMF | PVDF | Degrading CR | 50-W LED light CR solution concentration 20 μM |

96% within 210 min | Sahu and Dhar Purkayastha87 |

| Ni(DMG)2/TiO2 | Voltage 10 kV Distance 15 cm |

DMF | PAN, PVP | Degrading MB | MB solution at 10 mg/L | 97% within 60 min | Lv et al.88 |

| InVO4/CeVO4 | Voltage 20 kV Distance 20 cm |

C2H5OH | PVP | Degrading TC | 800-W Xe light TC solution at 20 mg/L |

100% within 90 min | Ding et al.89 |

| WO2.72/Fe3O4 | Voltage 15 kV Distance 15 cm |

C2H5OH | PVA | Redox Cr(VI) | 500-W Xe light | 100% within 3 h | Motora et al.90 |

| WO3/CdWO4 | Voltage 20 kV Distance 15 cm |

DMF, C2H5OH | PVP | Degrading TC | 500-W Xe light TC solution at 10 mg/L |

81.6% within 90 min | Rong et al.91 |

| PVDF/CdS/TiO2 | Voltage 9.32 kV Distance 15 cm |

DMF, CH3COCH3 | PVDF | Redox Cr(VI) | 350-W Xe light | 96.6% within 40 min | Li et al.92 |

| RGO/TiO2/PANCMA |

Voltage 14 kV Distance 30 cm |

DMF | PANCMA | Degrading MG | MG solution at 100 ng/L | 90.6% within 62 min | Du et al.93 |

| RbxWO3@Fe3O4 | Voltage 15 kV Distance 15 cm |

MC, DMF | PET | Redox Cr(VI) | Cr(VI) solution at 50 mg/L | 100% within 90 min | Naseem et al.94 |

| TiO2(A-R)/ZnTiO3 | Voltage 18 kV Distance 18 cm |

DMF | PVP | Hydrogen production | – | 887.7 μmol g−1·h−1 | Yerli Soylu et al.95 |

| ZnO/ZnFe2O4/Pt | Voltage 17 kV Pushing speed 0.5 mL h−1 |

DMF | PVP | Degrading CIP | 300-W Xe light CIP solution at 10 mg/L |

92% within 2 h | Sobahi et al.96 |

| TiO2-SiO2-Al2O3-ZrO2-CaO-CeO2 | Voltage 20 kV Distance 13 cm |

DMF | PAN | Degrading MB | MB solution at 20 mg/L | 90.7% within 120 min | Yerli Soylu et al.95 |

| BiOI/SiO2 | Voltage 9 kV Pushing speed 10 μL/min |

DI | PVA | Degrading RhB | RhB solution 10 mg/L | 68% within 3 h | Liu et al.97 |

| CeO2/CuS | Voltage 18–19 kV Pushing speed 0.05 mL/min |

DMF, C2H5OH | PVP | Degrading MB | Striped blue LEDs MB solution 3 mg/L |

96.38% within 50 min | Sabzehmeidani et al.98 |

| ZnO/Ag | Voltage 28 kV Pushing speed 1.5 mL/h |

DMF | PVP | Degrading MO | 100-W UV lamp MB solution 10 mg/L |

92% within 15 min | Li et al.99 |

| SrTiO3/TiO2 | Voltage 15 kV Distance 15 cm |

DMF and CH3COOH | PVP | Degrading MO | 25-W UV-C mercury lamp MO solution at 15 mg/L |

93% within 40 min | Zhao et al.100 |

| ZnO/γ-Bi2MoO6 | Voltage 20 kV Needle diameter 0.8 mm |

DI and C2H5OH | PVP | Degrading MB | 500-W Xe lamp | 95.6% within 4 h | Wang et al.101 |

| TiO2@Ag@Cu2O | Voltage 18 kV Needle Pushing speed 1.5 mL/h |

DMF | PAN | Degrading MB | 600-W Xe lamp MB solution at 10 mg/L |

99% within 2.5 h | Li et al.102 |

| Bi2MoO6/S-C3N4/PAN | Voltage 15 kV Pushing speed 0.5 mm/h |

C2H6O2, C2H5OH | PAN | Degrading 4-NP | An LED lamp (10-W, λ ≥ 400 nm) | 83% within 3 h | Chen et al.103 |

| g-C3N4/AuNPs/PVDF | Voltage 20 kV Push speed 1.5 mL/h. |

DI | PVDF | Degrading MB | Two COB LEDs | 98% within 3 h | Saha et al.104 |

| g-C3N4/BiOI | Voltage 10 kV Distance 16 cm |

DMF | PAN | Degrading RhB | Visible light irradiation (λ > 400 nm) | 98% within 90 min | Zhou et al.105 |

| GO/MIL-101(Fe)/PANCMA | Voltage 11 kV Distance 30 cm |

DMF | PAN | Degrading RhB | 16-W UV lamp | 93.7% within 20 min | Huang et al.106 |

| BaTiO3-TiO2 | Voltage 18kV Distance 15 cm |

C2H5OH, CH3COOH | PVP | Degrading RhB | 300-W high pressure mercury lamp | 99.8% within 1 h | Liu et al.107 |

| Co3O4@CeO2 | Voltage 20 ± 0.5 kV | C2H5OH, CH3COOH, DMF | PAN | Degrading levofloxacin |

Levofloxacin concentration at 20 ppm | 93.8% within 14 min | Wang et al.108 |

| CuS QDs/BiVO4@Y2O2S | Voltage 21 kV Distance 18 cm |

DMF | PVP | Degrading RhB | 300-W Xe lamp RhB solution at 10 mg/L |

87.4% within 2 h | Guo et al.109 |

| MoS2/PANI/PAN@BiFeO3 | Voltage 17 kV Distance 15 cm |

DMF | PAN, PANI | Degrading MO | MO solution 15 mg/L | 99.9% within 60 min | Lin et al.110 |

| Tm@ND@TiO2/mSC | – | DMF | PAN/PEG | Degrading MO | MO solution 40 mg/L | 94% within 60 min | Su et al.111 |

| CoMn2O4/HACNFs | Voltage 13 kV Distance 8 cm |

DMF | PMMA, PAN | Degrading RhB | RhB concentration at 50 μM | 84.8% within 200 min | Kang et al.112 |

COB, chip-on-board; MO, methyl orange; ENR, enrofloxacin; PEO, polyethylene oxide; MC, methylene chloride; CIP, ciprofloxacin; PVDF, polyvinylidene fluoride; PEG, polyethylene glycol; PMMA, polymethyl methacrylate; PANCMA, poly(acrylonitrile-co-maleic acid); MG, malachite green.

Summary and outlook

In recent years, electrospinning technology has found widespread application in the preparation of nanofiber-structured photocatalysts.113 This review provides a comprehensive summary of the current application and development status of electrospinning technology in the preparation and modification of photocatalysts. Despite significant efforts, the industrial application of photocatalysis technology remains distant due to inadequate efficiency exhibited by current photocatalysts.5 Constructing a multiple heterojunction compound model represents a potential strategy for designing highly active photocatalysts by enhancing charge separation properties.114 However, the current methods, primarily wet-chemical and in situ growth, do not allow for precise arrangement of the components according to the model. In contrast, coaxial electrospinning technology is a suitable method for effectively constructing a multilayer system due to its ability to arrange materials in layers along the concentric axis. Therefore, the construction of a multicomponent composite system using coaxial electrospinning technology holds great significance for studying a multicomponent photocatalytic system model.

Moreover, electrospinning offers significant potential for large-scale production, particularly in fabricating complex nanostructures such as hollow, core-shell, and mesoporous fibers. These advanced architectures provide enhanced surface area and improved access to active catalytic sites, optimizing interactions between photocatalytic components and boosting reaction efficiency.115 By facilitating better light absorption and charge transport pathways, electrospun nanofibers reduce electron-hole recombination, a key limitation in many photocatalytic systems. Understanding the process-structure-performance relationship—factors such as polymer composition, solution viscosity, applied voltage, and spinning speed—allows for fine-tuning fiber morphology, porosity, and crystallinity, all of which directly impact performance.116 As electrospinning techniques evolve, they offer a scalable, cost-effective solution for producing high-performance photocatalysts, particularly in metal oxide semiconductor systems.117 This approach not only enables industrial-scale production but also paves the way for advanced materials designed for environmental remediation, solar energy harvesting, and other energy applications.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful for financial support from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (22002074), Natural Science Foundation of Shandong Province (ZR2022ME010), and Youth Innovation Team Program in Colleges of Shandong Province (2023KJ144).

Author contributions

Investigation and writing – original draft, F.G.; writing – review & editing, L.H., L.F., B.H., J.N., X.Z., S.C., and B.L.; supervision, X.Z. and S.C.

Declaration of interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Contributor Information

Xuliang Zhang, Email: zhangxl@sdut.edu.cn.

Shuangying Chen, Email: chen05537@qq.com.

Bo Liu, Email: liub@sdut.edu.cn.

References

- 1.Baig N., Kammakakam I., Falath W. Nanomaterials: a review of synthesis methods, properties, recent progress, and challenges. Mater. Adv. 2021;2:1821–1871. doi: 10.1039/d0ma00807a. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wu X., Zhang Q., Li W., Qiao B., Ma D., Wang S.L. Atomic-scale Pd on 2D titania sheets for selective oxidation of methane to methanol. ACS Catal. 2021;11:14038–14046. doi: 10.1021/acscatal.1c03985. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lakhani P., Bhanderi D., Modi C.K. Nanocatalysis: recent progress, mechanistic insights, and diverse applications. J. Nanoparticle Res. 2024;26 doi: 10.1007/s11051-024-06053-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chen X., Cao H., He Y., Zhou Q., Li Z., Wang W., He Y., Tao G., Hou C. Advanced functional nanofibers: strategies to improve performance and expand functions. Front. Optoelectron. 2022;15 doi: 10.1007/s12200-022-00051-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zhong Y., Peng C., He Z., Chen D., Jia H., Zhang J., Ding H., Wu X. Interface engineering of heterojunction photocatalysts based on 1D nanomaterials. Catal. Sci. Technol. 2021;11:27–42. doi: 10.1039/d0cy01847c. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yuan S., Zhang Q. Application of one-dimensional nanomaterials in catalysis at the single-molecule and single-particle scale. Front. Chem. 2021;9 doi: 10.3389/fchem.2021.812287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Li Y., Zhu J., Cheng H., Li G., Cho H., Jiang M., Gao Q., Zhang X. Developments of advanced electrospinning techniques: A critical review. Adv. Mater. Technol. 2021;6 doi: 10.1002/admt.202100410. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Islam M.S., Ang B.C., Andriyana A., Afifi A.M. A review on fabrication of nanofibers via electrospinning and their applications. SN Appl. Sci. 2019;1 doi: 10.1007/s42452-019-1288-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chen S., Zhou J., Fang B., Ying Y., Yu D., He H. Three EHDA processes from a detachable spinneret for fabricating drug fast dissolution composites. Macromol. Mater. Eng. 2023;309 doi: 10.1002/mame.202300361. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chen X., Liu Y., Liu P. Electrospun core–sheath nanofibers with a cellulose acetate coating for the synergistic release of zinc ion and drugs. Mol. Pharm. 2024;21:173–182. doi: 10.1021/acs.molpharmaceut.3c00703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zhou J., Chen Y., Liu Y., Huang T., Xing J., Ge R., Yu D.G. Electrospun medicated gelatin/polycaprolactone Janus fibers for photothermal-chem combined therapy of liver cancer. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024;269 doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2024.132113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wang M., Hou J., Yu D.G., Li S., Zhu J., Chen Z. Electrospun tri-layer nanodepots for sustained release of acyclovir. J. Alloys Compd. 2020;846 doi: 10.1016/j.jallcom.2020.156471. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Xu L., Li Q., Wang H., Liu H., Yu D.-G., Bligh S.-W.A., Lu X. Electrospun multi-functional medicated tri-section Janus nanofibers for an improved anti-adhesion tendon repair. Chem. Eng. J. 2024;492 doi: 10.1016/j.cej.2024.152359. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sun Y., Zhou J., Zhang Z., Yu D.-G., Bligh S.W.A. Integrated Janus nanofibers enabled by a co-shell solvent for enhancing icariin delivery efficiency. Int. J. Pharm. 2024;658 doi: 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2024.124180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yu D.G., Gong W., Zhou J., Liu Y., Zhu Y., Lu X. Engineered shapes using electrohydrodynamic atomization for an improved drug delivery. WIREs Nanomed. Nanobiotechnol. 2024;16:e1964. doi: 10.1002/wnan.1964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sun L., Zhou J., Chen Y., Yu D.-G., Liu P. A combined electrohydrodynamic atomization method for preparing nanofiber/microparticle hybrid medicines. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2023;11 doi: 10.3389/fbioe.2023.1308004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mao H., Zhou J., Yan L., Zhang S., Yu D.-G. Hybrid films loaded with 5-fluorouracil and Reglan for synergistic treatment of colon cancer via asynchronous dual-drug delivery. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2024;12 doi: 10.3389/fbioe.2024.1398730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zhang P., Zhao Y., Li Y., Li N., Silva S.R.P., Shao G., Zhang P. Revealing the selective bifunctional electrocatalytic sites via in situ irradiated x-ray photoelectron spectroscopy for lithium–sulfur battery. Adv. Sci. 2023;10:e2206786. doi: 10.1002/advs.202206786. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ahmadi Bonakdar M., Rodrigue D. Electrospinning: processes, structures, and materials. Macromolecules (Washington, DC, U. S.) 2024;4:58–103. doi: 10.3390/macromol4010004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yoon J., Yang H.S., Lee B.S., Yu W.R. Recent progress in coaxial electrospinning: New parameters, various structures, and wide applications. Adv. Mater. 2018;30:e1704765. doi: 10.1002/adma.201704765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chen Y.-F., Lee Y.-C., Lee J.C.-M., Li J.-W., Chiu C.-W. Coaxial electrospinning of Au@silicate/poly(vinyl alcohol) core/shell composite nanofibers with non-covalently immobilized gold nanoparticles for preparing flexible, freestanding, and highly sensitive SERS substrates amenable to large-scale fabrication. Adv. Compos. Hybrid Mater. 2024;7 doi: 10.1007/s42114-024-00933-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Liu R., Hou L., Yue G., Li H., Zhang J., Liu J., Miao B., Wang N., Bai J., Cui Z., et al. Progress of fabrication and applications of electrospun hierarchically porous nanofibers. Adv. Fiber Mater. 2022;4:604–630. doi: 10.1007/s42765-022-00132-z. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lu J., Liu M., Zhou S., Zhou X., Yang Y. Electrospinning fabrication of ZnWO4 nanofibers and photocatalytic performance for organic dyes. Dyes Pigments. 2017;136:1–7. doi: 10.1016/j.dyepig.2016.08.008. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wang L., Yang G., Peng S., Wang J., Ji D., Yan W., Ramakrishna S. Fabrication of MgTiO3 nanofibers by electrospinning and their photocatalytic water splitting activity. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy. 2017;42:25882–25890. doi: 10.1016/j.ijhydene.2017.08.194. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Perween S., Ranjan A. Improved visible-light photocatalytic activity in ZnTiO3 nanopowder prepared by sol-electrospinning. Sol. Energy Mater. Sol. Cell. 2017;163:148–156. doi: 10.1016/j.solmat.2017.01.020. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kim J. Hollow TiO2/Poly (Vinyl Pyrrolidone) fibers obtained via coaxial electrospinning as easy-to-handle photocatalysts for effective nitrogen oxide removal. Polymers. 2022;14:4942. doi: 10.3390/polym14224942. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Li S., Guo M., Wang X., Gao K. Fabrication and photocatalytic activity of LaFeO3 ribbon-like nanofibers. J. Chin. Chem. Soc. 2019;67:990–997. doi: 10.1002/jccs.201900431. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lv C., Sun J., Chen G., Zhou Y., Li D., Wang Z., Zhao B. Organic salt induced electrospinning gradient effect: Achievement of BiVO4 nanotubes with promoted photocatalytic performance. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 2017;208:14–21. doi: 10.1016/j.apcatb.2017.02.058. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pantò F., Dahrouch Z., Saha A., Patanè S., Santangelo S., Triolo C. Photocatalytic degradation of methylene blue dye by porous zinc oxide nanofibers prepared via electrospinning: When defects become merits. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2021;557 doi: 10.1016/j.apsusc.2021.149830. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tong H.x., Tian X., Wu D.x., Wang C.f., Zhang Q.l., Jiang Z.h. WO3 nanofibers on ACF by electrospun for photo-degradation of phenol solution. J. Cent. South Univ. 2017;24:1275–1280. doi: 10.1007/s11771-017-3532-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Goodarzi N., Ashrafi-Peyman Z., Khani E., Moshfegh A.Z. Recent progress on semiconductor heterogeneous photocatalysts in clean energy production and environmental remediation. Catalysts. 2023;13:1102. doi: 10.3390/catal13071102. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Liu J., Yao H., Chai X., Zhang X., Fu J. Review of electrospinning technology of photocatalysis, electrocatalysis and magnetic response. J. Mater. Sci. 2024;59:10623–10649. doi: 10.1007/s10853-024-09788-x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zhang J., Jiang X., Huang J., Lu W., Zhang Z. Plasmon-enhanced photocatalytic overall water-splitting over Au nanoparticle-decorated CaNb2O6 electrospun nanofibers. J. Mater. Chem. A Mater. 2022;10:20048–20058. doi: 10.1039/d2ta05332b. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Han C., Mao W., Bao K., Xie H., Jia Z., Ye L. Preparation of Ag/Ga2O3 nanofibers via electrospinning and enhanced photocatalytic hydrogen evolution. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy. 2017;42:19913–19919. doi: 10.1016/j.ijhydene.2017.06.076. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ye S., Zhou X., Xu Y., Lai W., Yan K., Huang L., Ling J., Zheng L. Photocatalytic performance of multi-walled carbon nanotube/BiVO4 synthesized by electro-spinning process and its degradation mechanisms on oxytetracycline. Chem. Eng. J. 2019;373:880–890. doi: 10.1016/j.cej.2019.05.109. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Jo S., Kim H., Lee T.S. Decoration of conjugated polyquinoxaline dots on mesoporous TiO2 nanofibers for visible-light-driven photocatalysis. Polymer. 2021;228 doi: 10.1016/j.polymer.2021.123892. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kumar L., Singh S., Horechyy A., Formanek P., Hübner R., Albrecht V., Weißpflog J., Schwarz S., Puneet P., Nandan B. Hollow Au@TiO2 porous electrospun nanofibers for catalytic applications. RSC Adv. 2020;10:6592–6602. doi: 10.1039/c9ra10487a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Guo X., Qiu C., Zhang Z., Zhang J., Wang L., Ding J., Zhang J., Wan H., Guan G. Coaxial electrospinning prepared Cu species loaded SrTiO3 for efficient photocatalytic reduction of CO2 to CH3OH. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2024;12 doi: 10.1016/j.jece.2024.111990. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Xie R., Zhang L., Liu H., Xu H., Zhong Y., Sui X., Mao Z. Construction of CQDs-Bi20TiO32/PAN electrospun fiber membranes and their photocatalytic activity for isoproturon degradation under visible light. Mater. Res. Bull. 2017;94:7–14. doi: 10.1016/j.materresbull.2017.05.040. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Yao L., Sun C., Lin H., Li G., Lian Z., Song R., Zhuang S., Zhang D. Electrospun Bi-decorated BixTiyOz/TiO2 flexible carbon nanofibers and their applications on degradating of organic pollutants under solar radiation. J. Mater. Sci. Technol. 2023;150:114–123. doi: 10.1016/j.jmst.2022.07.066. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Yousef A., Brooks R.M., El-Halwany M.M., El-Newehy M.H., Al-Deyab S.S., Barakat N.A. Cu0/S-doped TiO2 nanoparticles-decorated carbon nanofibers as novel and efficient photocatalyst for hydrogen generation from ammonia borane. Ceram. Int. 2016;42:1507–1512. doi: 10.1016/j.ceramint.2015.09.097. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sheikh F.A., Appiah-Ntiamoah R., Zargar M.A., Chandradass J., Chung W.-J., Kim H. Photocatalytic properties of Fe2O3-modified rutile TiO2 nanofibers formed by electrospinning technique. Mater. Chem. Phys. 2016;172:62–68. doi: 10.1016/j.matchemphys.2015.12.060. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wang W., Du L., Xia R., Liang R., Zhou T., Lee H.K., Yan Z., Luo H., Shang C., Phillips D.L., Guo Z. In situprotonated-phosphorus interstitial doping induces long-lived shallow charge trapping in porous C3−XN4 photocatalysts for highly efficient H2 generation. Energy Environ. Sci. 2023;16:460–472. doi: 10.1039/d2ee02680e. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Khlyustova A., Sirotkin N., Kusova T., Kraev A., Titov V., Agafonov A. Doped TiO2: the effect of doping elements on photocatalytic activity. Mater. Adv. 2020;1:1193–1201. doi: 10.1039/d0ma00171f. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Li Y., Zhu G., Huang H., Xu M., Lu T., Pan L. A N, S dual doping strategy via electrospinning to prepare hierarchically porous carbon polyhedra embedded carbon nanofibers for flexible supercapacitors. J. Mater. Chem. A Mater. 2019;7:9040–9050. doi: 10.1039/c8ta12246f. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Jian S., Tian Z., Hu J., Zhang K., Zhang L., Duan G., Yang W., Jiang S. Enhanced visible light photocatalytic efficiency of La-doped ZnO nanofibers via electrospinning-calcination technology. Adv. Powder Mater. 2022;1 doi: 10.1016/j.apmate.2021.09.004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Chen Y., Li A., Fu X., Peng Z. Electrospinning-based (N,F)-co-doped TiO2-δ nanofibers: An excellent photocatalyst for degrading organic dyes and heavy metal ions under visible light. Mater. Chem. Phys. 2022;291 doi: 10.1016/j.matchemphys.2022.126672. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Qi W., Yang Y., Du J., Yang J., Guo L., Zhao L. Highly photocatalytic electrospun Zr/Ag Co-doped titanium dioxide nanofibers for degradation of dye. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2021;603:594–603. doi: 10.1016/j.jcis.2021.06.109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kang S., Hwang J. rGO-wrapped Ag-doped TiO2 nanofibers for photocatalytic CO2 reduction under visible light. J. Clean. Prod. 2022;374 doi: 10.1016/j.jclepro.2022.134022. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Zhu Z., Zhang H., Teng Y., Lin X., Li M., Li Y. Enhanced photocatalytic hydrogen evolution over Ce–TiO2/graphite/g-C3N4 ternary S-scheme heterojunction. Surface. Interfac. 2023;41 doi: 10.1016/j.surfin.2023.103160. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Pan Q., Wang J., Chen H., Yin P., Cheng Q., Xiao Z., Zhao Y.-Z., Liu H.-B. Piezo-photocatalysis of Sr-doped Bi4O5Br2/Bi2MoO6 composite nanofibers to simultaneously remove inorganic and organic contaminants. J. Water Proc. Eng. 2023;56 doi: 10.1016/j.jwpe.2023.104330. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Zhan M., Fang M., Li L., Zhao Y., Yang B., Min X., Du P., Liu Y., Wu X., Huang Z. Effect of Fe dopant on oxygen vacancy variation and enhanced photocatalysis hydrogen production of LaMnO3 perovskite nanofibers. Mater. Sci. Semicond. Process. 2023;166 doi: 10.1016/j.mssp.2023.107697. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Song Z., Yu S., Wang K., Jiang Z., Xue L., Yang F. Novel Sc-doped Bi3TiNbO9 ferroelectric nanofibers prepared by electrospinning for visible-light photocatalysis. J. Rare Earths. 2023;41:365–373. doi: 10.1016/j.jre.2022.01.010. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Gadisa B.T., Kassahun S.K., AppiahNtiamoah R., Kim H. Tuning the charge carrier density and exciton pair separation in electrospun 1D ZnO-C composite nanofibers and its effect on photodegradation of emerging contaminants. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2020;570:251–263. doi: 10.1016/j.jcis.2020.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Mani A.D., Li J., Wang Z., Zhou J., Xiang H., Zhao J., Deng L., Yang H., Yao L. Coupling of piezocatalysis and photocatalysis for efficient degradation of methylene blue by Bi0.9Gd0.07La0.03FeO3 nanotubes. J. Adv. Ceram. 2022;11:1069–1081. doi: 10.1007/s40145-022-0590-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Shalan A.E., Afifi M., El-Desoky M.M., Ahmed M.K. Electrospun nanofibrous membranes of cellulose acetate containing hydroxyapatite co-doped with Ag/Fe: morphological features, antibacterial activity and degradation of methylene blue in aqueous solution. New J. Chem. 2021;45:9212–9220. doi: 10.1039/d1nj00569c. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Na K.H., Kim B.S., Yoon H.S., Song T.H., Kim S.W., Cho C.H., Choi W.Y. Fabrication and photocatalytic properties of electrospun Fe-Doped TiO2 nanofibers using polyvinyl pyrrolidone precursors. Polymers. 2021;13:2634. doi: 10.3390/polym13162634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Ren J., Zhao D., Liu H., Zhong Y., Ning J., Zhang Z., Zheng C., Hu Y. Electrospinning preparation of Sn4+-doped BiFeO3 nanofibers as efficient visible-light-driven photocatalyst for O2 evolution. J. Alloys Compd. 2018;766:274–283. doi: 10.1016/j.jallcom.2018.06.329. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Liu L., Liu Z., Yang Y., Geng M., Zou Y., Shahzad M.B., Dai Y., Qi Y. Photocatalytic properties of Fe-doped ZnO electrospun nanofibers. Ceram. Int. 2018;44:19998–20005. doi: 10.1016/j.ceramint.2018.07.268. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Singh N., Prakash J., Misra M., Sharma A., Gupta R.K. Dual functional Ta-Doped electrospun TiO2 nanofibers with enhanced photocatalysis and SERS detection for organic compounds. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces. 2017;9:28495–28507. doi: 10.1021/acsami.7b07571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Lu N., Shao C., Li X., Miao F., Wang K., Liu Y. A facile fabrication of nitrogen-doped electrospun In2O3 nanofibers with improved visible-light photocatalytic activity. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2017;391:668–676. doi: 10.1016/j.apsusc.2016.07.057. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Wei S., Wang L., Yue J., Wu R., Fang Z., Xu Y. Recent progress in polymer nanosheets for photocatalysis. J. Mater. Chem. A Mater. 2023;11:23720–23741. doi: 10.1039/d3ta05435g. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Meng X., Qiao J., Liu J., Wu L., Wang Z., Wang F. Core–shell nanofibers/polyurethane composites obtained through electrospinning for ultra-broadband electromagnetic wave absorption. Adv. Compos. Hybrid Mater. 2024;7 doi: 10.1007/s42114-024-00976-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Jiang X., Huang J., Bi Z., Ni W., Gurzadyan G., Zhu Y., Zhang Z. Plasmonic active "hot spots"-confined photocatalytic CO2 reduction with high selectivity for CH4 production. Adv. Mater. 2022;34 doi: 10.1002/adma.202109330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Ai Y., Li Y., Li T., Hou R., Wang Q., Habib A., Shao G., Zhang P. ZnIn2Se4 nanoparticles photocatalyst for efficient solar fuel production. iScience. 2024;27 doi: 10.1016/j.isci.2024.110422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Li Q.H., Dong M., Li R., Cui Y.Q., Xie G.X., Wang X.X., Long Y.Z. Enhancement of Cr(VI) removal efficiency via adsorption/photocatalysis synergy using electrospun chitosan/g-C3N4/TiO2 nanofibers. Carbohydr. Polym. 2021;253 doi: 10.1016/j.carbpol.2020.117200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Wang L., Li Y., Han P. Electrospinning preparation of g-C3N4/Nb2O5 nanofibers heterojunction for enhanced photocatalytic degradation of organic pollutants in water. Sci. Rep. 2021;11 doi: 10.1038/s41598-021-02161-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Yang Y., Zhou S., Cao X., Lv H., Liang Z., Zhang R., Ye F., Yu D. Coaxial electrospun porous core–shell nanofibrous membranes for photodegradation of organic dyes. Polymers. 2024;16:754. doi: 10.3390/polym16060754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Mao Y., Lin L., Chen Y., Yang M., Zhang L., Dai X., He Q., Jiang Y., Chen H., Liao J., et al. Preparation of site-specific Z-scheme g-C3N4/PAN/PANI@LaFeO3 cable nanofiber membranes by coaxial electrospinning: Enhancing filtration and photocatalysis performance. Chemosphere. 2023;328 doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2023.138553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Jiang B., Wang T., Li F., Li D., Yang Y., Yu H., Dong X. Polyoxometalate as pivotal interface in SnO2@PW12@TiO2 coaxial nanofibers: From heterojunction design to photocatalytic and gas sensing applications. Sensor. Actuator. B Chem. 2023;390 doi: 10.1016/j.snb.2023.133928. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Ma J., Jin X., Lu Y., Yang M., Zhao X., Guo M., Zhang H., Li X., Wang B. Preparation of modified halloysite nanotubes@Ag3PO4/polyacrylonitrile electrospinning membranes for highly efficient air filtration and disinfection. Appl. Clay Sci. 2024;253 doi: 10.1016/j.clay.2024.107361. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Guo F., Guo Z., Gao L., Qi D., Yue G., Wang N., Zhao Y., Li N., Xiong J., Low J. Electrospun core-shell hollow structure cocatalysts for enhanced photocatalytic activity. J. Nanomater. 2021;2021:1–7. doi: 10.1155/2021/9980810. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Odhiambo V.O., Ongarbayeva A., Kéri O., Simon L., Szilágyi I.M. Synthesis of TiO2/WO3 composite nanofibers by a water-based electrospinning process and their application in photocatalysis. Nanomaterials. 2020;10:882. doi: 10.3390/nano10050882. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Liu H., Zhang Z.G., Wang X.X., Nie G.D., Zhang J., Zhang S.X., Cao N., Yan S.Y., Long Y.Z. Highly flexible Fe2O3/TiO2 composite nanofibers for photocatalysis and ultraviolet detection. J. Phys. Chem. Solid. 2018;121:236–246. doi: 10.1016/j.jpcs.2018.05.019. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Chang M.J., Cui W.N., Wang H., Liu J., Li H.L., Du H.L., Peng L.G. Recoverable magnetic CoFe2O4/BiOI nanofibers for efficient visible light photocatalysis. Colloids Surf. A Physicochem. Eng. Asp. 2019;562:127–135. doi: 10.1016/j.colsurfa.2018.11.016. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Zhang J.J., Kai C.M., Zhang F.J., Wang Y.R. Novel PAN/Bi2MoO6/Ti3C2 ternary composite membrane via electrospinning with enhanced photocatalytic degradation of tetracycline. Colloids Surf. A Physicochem. Eng. Asp. 2022;648 doi: 10.1016/j.colsurfa.2022.129255. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Odhiambo V.O., Mustafa C.R.M., Thong L.B., Kónya Z., Cserháti C., Erdélyi Z., Lukác I.E., Szilágyi I.M. Preparation of TiO2/WO3/C/N composite nanofibers by electrospinning using precursors soluble in water and their photocatalytic activity in visible light. Nanomaterials. 2021;11:351. doi: 10.3390/nano11020351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Li B., Zhang B., Nie S., Shao L., Hu L. Optimization of plasmon-induced photocatalysis in electrospun Au/CeO2 hybrid nanofibers for selective oxidation of benzyl alcohol. J. Catal. 2017;348:256–264. doi: 10.1016/j.jcat.2016.12.025. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Zhang T., Chen L., Yuan C., Su M., Liu X., Huang S., Jiang M., Su K., Wang D. The photocatalytic hydrogen evolution of g–C3N4/K0.5Na0.5NbO3 nanofibers heterojunction under visible light. J. Photochem. Photobiol. Chem. 2023;435 doi: 10.1016/j.jphotochem.2022.114192. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Yang F., Yu X., Liu Z., Niu J., Zhang T., Nie J., Zhao N., Li J., Yao B. Preparation of Z-scheme CuBi2O4/Bi2O3 nanocomposites using electrospinning and their enhanced photocatalytic performance. Mater. Today Commun. 2021;26 doi: 10.1016/j.mtcomm.2020.101735. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Li S., Dong Z., Wang Q., Zhou X., Shen L., Li H., Shi W. Antibacterial Z-scheme ZnIn2S4/Ag2MoO4 composite photocatalytic nanofibers with enhanced photocatalytic performance under visible light. Chemosphere. 2022;308 doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2022.136386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Sabzehmeidani M.M., Karimi H., Ghaedi M., Avargani V.M. Construction of efficient and stable ternary ZnFe2O4/Ag/AgBr Z-scheme photocatalyst based on ZnFe2O4 nanofibers under LED visible light. Mater. Res. Bull. 2021;143 doi: 10.1016/j.materresbull.2021.111449. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Du F., Yang D., Kang T., Ren Y., Hu P., Song J., Teng F., Fan H. SiO2/Ga2O3 nanocomposite for highly efficient selective removal of cationic organic pollutant via synergistic electrostatic adsorption and photocatalysis. Separ. Purif. Technol. 2022;295 doi: 10.1016/j.seppur.2022.121221. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Ghorbanloo M., Nada A.A., El-Maghrabi H.H., Bekheet M.F., Riedel W., Djamel B., Viter R., Roualdes S., Soliman F.S., Moustafa Y.M., et al. Superior efficiency of BN/Ce2O3/TiO2 nanofibers for photocatalytic hydrogen generation reactions. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2022;594 doi: 10.1016/j.apsusc.2022.153438. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Gong S., Fan J., Cecen V., Huang C., Min Y., Xu Q., Li H. Noble-metal and cocatalyst free W2N/C/TiO photocatalysts for efficient photocatalytic overall water splitting in visible and near-infrared light regions. Chem. Eng. J. 2021;405 doi: 10.1016/j.cej.2020.126913. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Chang Y.C., Syu S.Y., Wu Z.Y. Fabrication of ZnO-In2S3 composite nanofiber as highly efficient hydrogen evolution photocatalyst. Mater. Lett. 2021;302 doi: 10.1016/j.matlet.2021.130435. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Sahu S., Dhar Purkayastha D. 1D/2D ZnO nanoneedles/Ti3C2 MXene enrobed PVDF electrospun membrane for effective water purification. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2023;622 doi: 10.1016/j.apsusc.2023.156905. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Lv H., Zhang M., Wang P., Xu X., Liu Y., Yu D.-G. Ingenious construction of Ni(DMG)2/TiO2-decorated porous nanofibers for the highly efficient photodegradation of pollutants in water. Colloids Surf. A Physicochem. Eng. Asp. 2022;650 doi: 10.1016/j.colsurfa.2022.129561. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Ding W., Lin X., Ma G., Lu Q. Designed formation of InVO4/CeVO4 hollow nanobelts with Z-scheme charge transfer: Synergistically boosting visible-light-driven photocatalytic degradation of tetracycline. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2020;8 doi: 10.1016/j.jece.2020.104588. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Motora K.G., Wu C.-M., Naseem S. Magnetic recyclable self-floating solar light-driven WO2.72/Fe3O4 nanocomposites immobilized by Janus membrane for photocatalysis of inorganic and organic pollutants. J. Ind. Eng. Chem. 2021;102:25–34. doi: 10.1016/j.jiec.2021.06.025. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Rong F., Lu Q., Mai H., Chen D., Caruso R.A. Hierarchically porous WO3/CdWO4 fiber-in-tube nanostructures featuring readily accessible active sites and enhanced photocatalytic effectiveness for antibiotic degradation in water. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces. 2021;13:21138–21148. doi: 10.1021/acsami.0c22825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Li W., Liao G., Duan W., Gao F., Wang Y., Cui R., Wang X., Wang C. Synergistically electronic interacted PVDF/CdS/TiO2 organic-inorganic photocatalytic membrane for multi-field driven panel wastewater purification. Appl. Catal. B: Environ. Energy. 2024;354 doi: 10.1016/j.apcatb.2024.124108. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Du F., Sun L., Huang Z., Chen Z., Xu Z., Ruan G., Zhao C. Electrospun reduced graphene oxide/TiO2/poly(acrylonitrile-co-maleic acid) composite nanofibers for efficient adsorption and photocatalytic removal of malachite green and leucomalachite green. Chemosphere. 2020;239 doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2019.124764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Naseem S., Wu C.-M., Motora K.G. Novel multifunctional RbxWO3@Fe3O4 immobilized Janus membranes for desalination and synergic-photocatalytic water purification. Desalination. 2021;517 doi: 10.1016/j.desal.2021.115256. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Yerli Soylu N., Soylu A., Dikmetas D.N., Karbancioglu Guler F., Kucukbayrak S., Erol Taygun M. Photocatalytic and antimicrobial properties of electrospun TiO2–SiO2–Al2O3–ZrO2–CaO–CeO2 ceramic membranes. ACS Omega. 2023;8:10836–10850. doi: 10.1021/acsomega.2c06986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Sobahi T.R., Amin M.S. Synthesis of ZnO/ZnFe2O4/Pt nanoparticles heterojunction photocatalysts with superior photocatalytic activity. Ceram. Int. 2020;46:3558–3564. doi: 10.1016/j.ceramint.2019.10.073. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Liu J., Chang M.J., Du H.L. Fabrication and photocatalytic properties of flexible BiOI/SiO2 hybrid membrane by electrospinning method. J. Nanosci. Nanotechnol. 2017;17:3792–3797. doi: 10.1166/jnn.2017.14008. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Sabzehmeidani M.M., Karimi H., Ghaedi M. Visible light-induced photo-degradation of methylene blue by n–p heterojunction CeO2/CuS composite based on ribbon-like CeO2 nanofibers via electrospinning. Polyhedron. 2019;170:160–171. doi: 10.1016/j.poly.2019.05.040. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Li Z., Fan X., Meng A., Zhang Y., Zhu K., Li Q. Porous nanofibers formed by heterogeneous growth of ZnO/Ag particles and the enhanced photocatalysis. J. Nanosci. Nanotechnol. 2019;19:7163–7168. doi: 10.1166/jnn.2019.16518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Zhao W., Zhang J., Pan J., Qiu J., Niu J., Li C. One-step electrospinning route of SrTiO3-modified Rutile TiO2 nanofibers and its photocatalytic properties. Nanoscale Res. Lett. 2017;12:371. doi: 10.1186/s11671-017-2130-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Wang Q., Lu Q., Wei M., Guo E., Yao L., Sun K. ZnO/γ-Bi2MoO6 heterostructured nanotubes: electrospinning fabrication and highly enhanced photoelectrocatalytic properties under visible-light irradiation. J. Sol. Gel Sci. Technol. 2017;85:84–92. doi: 10.1007/s10971-017-4519-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Li X., Raza S., Liu C. Directly electrospinning synthesized Z-scheme heterojunction TiO2@Ag@Cu2O nanofibers with enhanced photocatalytic degradation activity under solar light irradiation. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2021;9 doi: 10.1016/j.jece.2021.106133. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Chen G., Hing Wong N., Sunarso J., Wang Y., Liu Z., Chen D., Wang D., Dai G. Flexible Bi2MoO6/S-C3N4/PAN heterojunction nanofibers made from electrospinning and solvothermal route for boosting visible-light photocatalytic performance. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2023;612 doi: 10.1016/j.apsusc.2022.155893. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Saha D., Gismondi P., Kolasinski K.W., Shumlas S.L., Rangan S., Eslami B., McConnell A., Bui T., Cunfer K. Fabrication of electrospun nanofiber composite of g-C3N4 and Au nanoparticles as plasmonic photocatalyst. Surface. Interfac. 2021;26 doi: 10.1016/j.surfin.2021.101367. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Zhou X., Shao C., Yang S., Li X., Guo X., Wang X., Li X., Liu Y. Heterojunction of g-C3N4/BiOI immobilized on flexible electrospun polyacrylonitrile nanofibers: facile preparation and enhanced visible photocatalytic activity for floating photocatalysis. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2018;6:2316–2323. doi: 10.1021/acssuschemeng.7b03760. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Huang Z., Lai Z., Zhu D., Wang H., Zhao C., Ruan G., Du F. Electrospun graphene oxide/MIL-101(Fe)/poly(acrylonitrile-co-maleic acid) nanofiber: A high-efficient and reusable integrated photocatalytic adsorbents for removal of dye pollutant from water samples. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2021;597:196–205. doi: 10.1016/j.jcis.2021.04.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Liu Z., Zhao K., Xing G., Zheng W., Tang Y. One-step synthesis of unique thorn-like BaTiO3–TiO2 composite nanofibers to enhance piezo-photocatalysis performance. Ceram. Int. 2021;47:7278–7284. doi: 10.1016/j.ceramint.2020.11.017. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Wang D., Ding S., He Z., Zhang T., Wang X. Tailor-made Co3O4@CeO2 based nanofibrous membrane with enhanced catalytic reactivity for efficient degradation of antibiotic. Compos. B Eng. 2024;278 doi: 10.1016/j.compositesb.2024.111424. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Guo D., Jiang S., Shen L., Pun E.Y.B., Lin H. Heterogeneous CuS QDs/BiVO4@Y2O2S Nanoreactor for Monitorable Photocatalysis. Small. 2024;20 doi: 10.1002/smll.202401335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Lin L., He Q., Chen Y., Wang B., Zhang L., Dai X., Jiang Y., Chen H., Liao J., Mao Y., et al. MoS2/polyaniline (PANI)/polyacrylonitrile (PAN)@BiFeO3 bilayer hollow nanofiber membrane: Photocatalytic filtration and piezoelectric effect enhancing degradation and disinfection. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2023;644:29–41. doi: 10.1016/j.jcis.2023.04.069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Su Y., Liu L., Wen S. Broadband NaYF4:Yb,Tm@NaYF4:Yb,Nd@TiO2 nanoparticles anchored on SiO2/Carbon electrospun fibers for photocatalytic degradation of organic pollutants. ACS Appl. Nano Mater. 2021;4:12576–12587. doi: 10.1021/acsanm.1c03091. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Kang S., Hwang J. CoMn2O4 embedded hollow activated carbon nanofibers as a novel peroxymonosulfate activator. Chem. Eng. J. 2021;406 doi: 10.1016/j.cej.2020.127158. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Nadaf A., Gupta A., Hasan N., Fauziya, Ahmad S., Kesharwani P., Ahmad F.J. Recent update on electrospinning and electrospun nanofibers: current trends and their applications. RSC Adv. 2022;12:23808–23828. doi: 10.1039/d2ra02864f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Xia M., Zhao X., Zhang Y., Pan W., Leung D.Y.C. Rational catalyst design for spatial separation of charge carriers in a multi-component photocatalyst for effective hydrogen evolution. J. Mater. Chem. A Mater. 2022;10:25380–25405. doi: 10.1039/d2ta06609b. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Zhang Z., Liu H., Yu D.G., Bligh S.W.A. Alginate-based electrospun nanofibers and the enabled drug controlled release profiles: A review. Biomolecules. 2024;14 doi: 10.3390/biom14070789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Ji Y., Zhao H., Liu H., Zhao P., Yu D.G. Electrosprayed stearic-acid-coated ethylcellulose microparticles for an improved sustained release of anticancer drug. Gels. 2023;9 doi: 10.3390/gels9090700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Zhao P., Zhou K., Xia Y., Qian C., Yu D.G., Xie Y., Liao Y. Electrospun trilayer eccentric Janus nanofibers for a combined treatment of periodontitis. Adv. Fiber Mater. 2024;6:1053–1073. doi: 10.1007/s42765-024-00397-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]