Abstract

Background

Streptococcus mutans is recognized as a key pathogen responsible for the development of dental caries. With the advancement of research on dental caries, the understanding of its pathogenic mechanism has gradually shifted from the theory of a single pathogenic bacterium to the theory of oral microecological imbalance. Acidogenic and aciduric microbial species are also recognized to participate in the initiation and progression of dental caries. This study is designed to elucidate the relationship between oral microbiome dysregulation and the initiation of dental caries.

Results

16 S rRNA gene sequencing of saliva and dental plaque from the Specific Pathogen Free Control group and the Specific Pathogen Free sucrose diet group revealed that a sucrose diet significantly influenced the composition of the oral microbiome. At the phylum level, the dominant microbial communities in both groups of mice were Firmicutes, Proteobacteria, Unclassified Bacteria, Actinobacteria, and Bacteroidetes. At the genus level, statistical analysis identified significant differences in the abundance of 18 genera between the two groups. The relative abundance of the Gemella genus was significantly increased in the SPF Sucrose group. The SPF Control group and the Germ-free Control group have no differential bacterial genera in the oral microbiome. Micro-CT examination of the mandibles revealed the development of dental caries in both the SPF Sucrose group and the Germ-free Sucrose group.

Conclusions

This study indicates that a dysbiotic microbial community can lead to the development of caries. Lays the foundation for further research into the etiology of dental caries.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s12866-025-03762-6.

Keywords: Dental caries, Oral microbiome, Dysbiosis, Mouse model

Introduction

The understanding of the etiology of dental caries has gradually shifted from the single pathogen theory to the dysbiosis theory with the advancement of research on dental caries and the development of sequencing technology [1]. Historically, Streptococcus mutans was identified as the predominant pathogen instigating dental caries [2]. However, the progression of molecular biology has unveiled that the sole presence of S. mutans is not adequate to induce dental caries. Additional acidogenic and aciduric microbial species are also recognized to participate in the initiation and progression of dental caries, such as Lactobacillus, Actinomyces, Bifidobacterium, Veillonella, and Propionibacterium [3–5]. The increased pathogenicity of oral microbial communities is typically the result of changes in community composition rather than infections caused by specific pathogens [6–8]. The changes in community composition can further impact the imbalance of the oral microbiome, leading to the development and progression of dental caries.

The disruption of the oral microenvironment is closely related to dietary intake. Although oral microbial communities have resilience [9, 10], frequent sugar intake accelerates microbial metabolism, leading to the accumulation of organic acids and polysaccharides. The sugar accumulation enhances the adhesion of microbial cells to the tooth surface, creating an acidic environment [11]. The acidic environment affects the metabolic activity of relevant oral microbes, resulting in the dominance of acid-producing and acid-tolerant species in the dental biofilm [12], while inhibiting the growth of acid-sensitive species. This further disrupts the homeostatic structure of the oral microbial community [13], driving the formation of cariogenic biofilms [14]. When the pH of the external dental biofilm falls below 5.5, demineralization of the teeth occurs, leading to the development of dental caries [15, 16]. When excessive sugars are consumed by humans, the microbes in dental plaque primarily ferment the sugars into lactic acid and acetic acid [17]. Individuals with active caries experience a more pronounced drop in pH following sugar consumption [18]. The acid produced from sugar metabolism can decrease the pH to as low as 3.9 or below. Furthermore, frequent sugar intake results in repeated decreases in plaque pH, which can enhance the acid tolerance of the microbial community and select acid-tolerant species, thereby increasing the risk of caries [19].

This study aims to develop a rational dental caries model and establish a stable microbial community within it, enabling a comprehensive investigation into the interactions between oral microbiome dysbiosis and the host immune system. Currently, most dental caries models are constructed by Specific Pathogen Free (SPF) grade rats to a sucrose diet and cariogenic microbial inoculations [20–22]. Germ-free (GF) mice are also effective animal models for studying microbial-host interactions because no viable microorganisms or parasites can be detected on the body surface or inside under current detection conditions [23–25]. This experiment used GF mice to establish a dental caries model, colonize the microbiome, and exclude the influence of native microorganisms to study the relationship between oral microbiome dysbiosis and the occurrence of dental caries. In this experiment, a dental caries model was constructed by continuously feeding SPF-grade mice a sucrose diet. Considering that dental plaque and saliva mixtures are aggregative manifestations of characteristic oral microbial communities [26], dental plaque and saliva from caries-affected and non-caries-affected mice were smeared and inoculated into germ-free mice to investigate whether the imbalance in oral microbial homeostasis can directly lead to the occurrence of dental caries.

Materials and methods

Dental caries modeling methods and sample collection

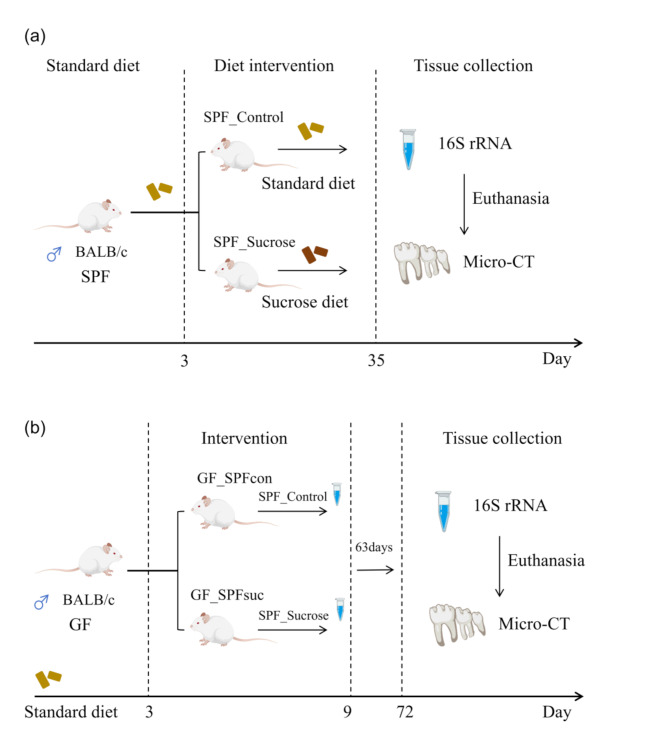

Twelve male Specific Pathogen Free grade BALB/c mice aged 21 days were randomly and averagely divided into the Specific Pathogen Free Control (SPF_Control) and Specific Pathogen Free sucrose diet (SPF_Sucrose) groups. Both groups were given a standard diet for 3 days to acclimate to the laboratory environment. The SPF_Control group continued on a normal diet, while the SPF_Sucrose group was given the National Institutes of Health cariogenic diet 2000 and 5% sucrose water [27]. After 32 days, saliva and dental plaque were collected from three mice in each group for 16 S rRNA gene sequencing. Subsequently, the mice were euthanized, and mandibular bone samples were taken for micro-computed tomography (Micro-CT) examination. Six Germ-free grade male BALB/c mice aged 21 days were given a standard diet for 3 days to acclimate to the laboratory environment and then divided into Germ-free Control (GF_SPFcon) and Germ-free Sucrose (GF_SPFsuc) groups. These groups were correspondingly smeared with the remaining saliva and dental plaque from the SPF_Control and SPF_Sucrose groups for 6 days. After 63 days, mandibular bone samples were taken from the GF mice for Micro-CT examination (Fig. 1). The BALB/c mice were purchased from GemPharmatech Co., Ltd. The mice were euthanized by cervical dislocation after being anesthetized with inhalation of 2% isoflurane. The experimental personnel have been trained to swiftly and humanely end the animals’ lives. The animal protocol was approved by the Ethical Committee of West China Hospital of Stomatology, Sichuan University (Chengdu, China) (Project identification code: WCHSIRB-D-2021-548).

Fig. 1.

Dental Caries Modeling Methods. (a) Specific Pathogen Free mice group fed with standard diet or NIH2000 (National Institutes of Health carcinogenic diet 2000). The Specific Pathogen Free Control (SPF_Control) group was fed a standard diet. The Specific Pathogen Free sucrose diet (SPF_Sucrose) group was administered the National Institutes of Health cariogenic diet 2000 and 5% sucrose water; (b) Germ_Free mice model group fed with standard diet. Continuous corresponding application of saliva and dental plaque from the remaining SPF group mice. (Oral microbiome: saliva and dental plaque)

Micro-CT

Mandibles were processed to harvest the posterior teeth and the associated alveolar bone, with the anterior teeth and alveolar regions being excised. The posterior teeth and alveolar bone were embedded in cylindrical foam matching the diameter of the scanning sample tube, ensuring alignment of the buccal and lingual surfaces in the same direction. The foam-encased samples were then placed into the sample tube for scanning with a high-resolution Micro CT scanner (CANCO MEDICAL AG µCT 50, Switzerland). After scanning, the images underwent rapid three-dimensional reconstruction. Upon completion of this reconstruction for the mandibular samples, a comprehensive analysis was performed using the “SCANCO Medical Evaluation” software. The presence and severity of dental caries were determined by identifying regions of diminished radiopacity within the tomographic sections.

DNA extraction, PCR amplification, and sequencing

Microbial DNA from mouse saliva and dental plaque samples was extracted using the FastDNA® Spin Kit for Soil (MP Biomedicals, Santa Ana, CA, USA). The total DNA was assessed via 1% agarose gel electrophoresis, and its concentration and purity were determined using the NanoDrop 2000 (Thermo Scientific, Wilmington, USA). The V3-V4 variable regions of bacterial 16 S rRNA gene were amplified using primers 338 F (5’-ACTCCTACGGGAGGCAGCAGG-3’) and 806R (5’-GGACTACHVGGGTWTCTAAT-3’). PCR products were recovered using 2% agarose gel electrophoresis (Thermo Scientific, USA), purified with the AxyPrep DNA Gel Extraction Kit (Axygen Biosciences, Union City, CA, USA), eluted with Tris-HCl, and checked for quality by 2% agarose gel electrophoresis. Finally, the purified PCR products were quantified using the QuantiFluor™-ST system (Promega, USA). Libraries were constructed using the NEXTFLEX Rapid DNA-Seq Kit, and paired-end sequencing was performed on the Illumina MiSeq PE300 platform (Illumina, San Diego, USA) following standard protocols. Sequencing was conducted using PE300 chemistry at Majorbio Bio-Pharm Technology Co. Ltd. (Shanghai, China).

Statistical analysis

All analytical procedures were performed on the Majorbio Bioinformatics Cloud Platform (https://cloud.majorbio.com), leveraging the UPARSE software to operationalize taxonomic units (OTUs) from quality-filtered and contiguous sequences at a 97% similarity threshold, while also eliminating chimeric sequences to derive representative OTU sequences. Taxonomic annotations for the OTUs were accomplished using the RDP classifier [28] in conjunction with the silva138/16s_bacteria gene database, set at a 70% confidence interval. The Mothur software package [29] was then engaged to compute Alpha diversity indices, including Simpson and Shannon, with subsequent inter-group Alpha diversity analysis conducted via the Wilcoxon rank-sum test. The structural similarity of microbial communities across samples was evaluated through Principal Coordinates Analysis (PCoA), predicated on Bray-Curtis dissimilarity metrics, alongside ANOSIM tests to ascertain the significance of differences in microbial community configurations between groups. Comparative analyses of the microbial community compositions were further conducted to elucidate distinctions between the two groups.

When the experimental data was not normally distributed, the Wilcoxon rank sum test analysis of variance was been used. Differences were considered statistically significant when P < 0.05. The statistical analysis of the experimental data obtained was performed using GraphPad Prism 9.5.

Result

Sucrose diet induces dental caries

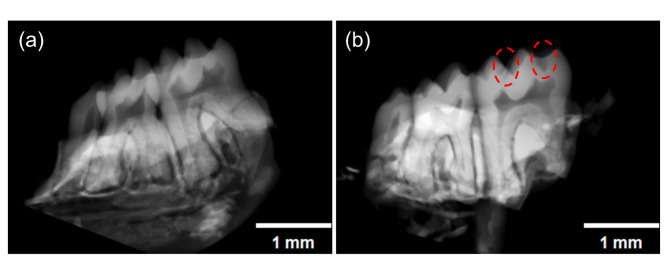

Micro-CT examination of the mandibles from the two SPF mice groups revealed that the SPF_Sucrose group exhibited surface wear and distinct cavities on the teeth (Fig. 2). Mice in the SPF_Control group did not develop dental caries (Fig. 2a). These findings indicate that a sucrose diet can induce the development of dental caries (Fig. 2b).

Fig. 2.

Micro-CT of the Specific Pathogen Free mice. (a) Micro-CT of Specific Pathogen Free Control (SPF_Control) group (n = 3); (b) Micro-CT of Specific Pathogen Free sucrose diet (SPF_Sucrose) group (n = 3). (Dental caries indicated by the red circles) Scale bar: 1 mm

Diversity analysis comparison of two SPF mice groups

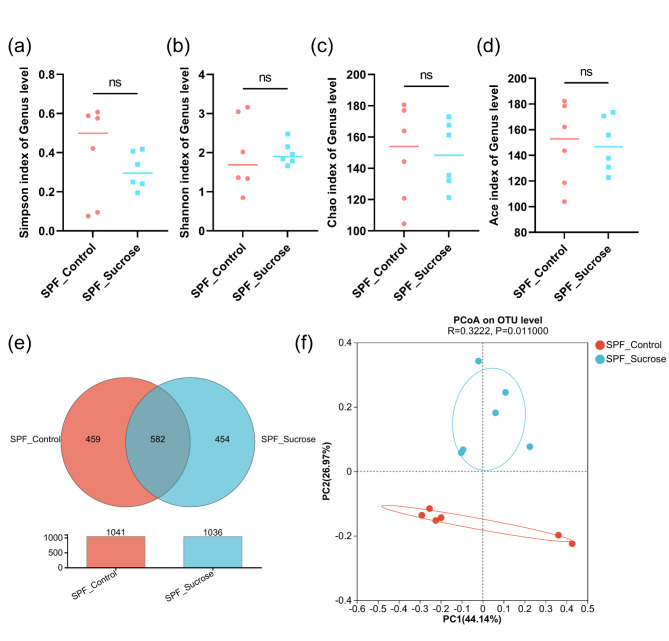

The results revealed no differences in the Alpha diversity indices between the SPF_Control group and the SPF_Sucrose group (P > 0.05), indicating that the diversity and abundance of the oral microbiome are similar between the two groups (Fig. 3a-d). A total of 1459 Operational Taxonomic Units (OTUs) were obtained from the samples. The healthy control group (SPF_Control) had 1041 OTUs, while the Sucrose treatment group (SPF_Sucrose) had 1036 OTUs. There were 582 OTUs shared between the two groups, suggesting similar species richness of the microbiome (Fig. 3e). PCoA analysis of the sequencing data was performed to assess the similarity of the microbial community structure (Fig. 3f). The results showed that there were differences in the composition of the bacterial communities between the two groups.

Fig. 3.

Diversity Analysis Comparison of two Specific Pathogen Free Mice Groups. (a) Alpha diversity of Simpson index; (b) Alpha diversity of Shannon index; (c) Alpha diversity of Chao index; (d) Alpha diversity of Ace index; (e) Venn diagram showing the specific and shared OTUs between the Specific Pathogen Free Control (SPF_Control) and Specific Pathogen Free sucrose diet (SPF_Sucrose) groups; (f) PCoA of community structures from Specific Pathogen Free Control (SPF_Control) and Specific Pathogen Free sucrose diet (SPF_Sucrose) groups. (ns: P > 0.05)

Microbial community abundance of two SPF mice groups

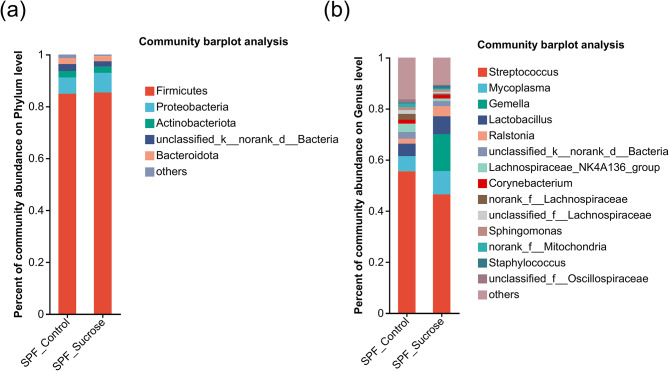

Microbial composition and relative abundance at various taxonomic levels were generated and presented as bar charts.

At the phylum level (Fig. 4a), the most abundant phyla in the SPF_Control group, with an abundance greater than 2%, were Firmicutes (84.9%), Proteobacteria (6.252%), Unclassified_Bacteria (2.65%), Actinobacteriota (2.535%), and Bacteroidota (2.314%).

Fig. 4.

Microbial community structure analysis of two Specific Pathogen Free Mice Groups. (a) Phylum level community composition for the Specific Pathogen Free Control (SPF_Control) and Specific Pathogen Free sucrose diet (SPF_Sucrose) groups; (b) Genus level community composition for the Specific Pathogen Free Control (SPF_Control) and Specific Pathogen Free sucrose diet (SPF_Sucrose) groups

In the SPF_Sucrose group, the phyla with an abundance greater than 2% were Firmicutes (85.37%), Proteobacteria (7.558%), Actinobacteriota (2.443%), Bacteroidota (2.043%), and Unclassified_Bacteria (2.02%).

At the genus level (Fig. 4b), the genera with higher relative abundance in the SPF_Control group included Streptococcus (55.54%), Mycoplasma (5.869%), Lactobacillus (4.918%), Lachnospiraceae_NK4A136_group (3.263%), unclassified_k__norank_d__Bacteria (2.65%), norank_f__Lachnospiraceae (2.276%), and Ralstonia (1.894%). In the SPF_Sucrose group, the genera with higher relative abundance were Streptococcus (46.47%), Gemella (14.45%), Mycoplasma (9.136%), Lactobacillus (6.977%), Ralstonia (3.945%), unclassified_k__norank_d__Bacteria (2.02%), and Corynebacterium (1.415%).

Abundance differences between the two groups were analyzed using the Wilcoxon rank-sum test from the phylum to genus levels (two-sided test, confidence interval 0.95). At the phylum level, Verrucomicrobiota showed a significant difference in abundance (Fig. 5a). The Wilcoxon rank-sum test revealed 18 genera with significant differences in abundance between the control group and the sucrose diet group (Fig. 5b). Among these, the genera with extremely significant differences (P < 0.01) include Gemella, Staphylococcus, Escherichia-Shigella, Faecalibaculum, Bifidobacterium, Facklamia, Psychrobacter, and Coriobacteriaceae_UCG-002. Notably, Gemella showed a significant difference in relative abundance between the two groups, with 14.03% in the SPF_Sucrose group and only 0.02274% in the SPF_Control group, indicating a substantial disparity.

Fig. 5.

Abundance analysis of the Oral microbiome within Specific Pathogen Free Control (SPF_Control) and Specific Pathogen Free sucrose diet (SPF_Sucrose) groups. (a) Abundance differences at the phylum level between the SPF_Control group and SPF_Sucrose group; (b) Abundance differences at the genus level between the SPF_Control group and SPF_Sucrose group. Significance was evaluated using Wilcoxon rank sum tests. (*0.01 < P ≤ 0.05, **0.001 < P ≤ 0.01)

Oral microbiome of SPF_Control group and GF_SPFcon group

16 S rRNA gene sequencing of the oral microbiome in SPF Control and GF_SPFcon groups was performed to verify the successful colonization of saliva and dental plaque from the SPF_Control group into the GF_SPFcon group. The results indicated no significant differences in Alpha diversity indices, including the Simpson index, Shannon index, Chao index, and Ace index (Fig. 6a-d). A total of 243 genera were obtained from the samples, with 201 genera in the SPF_Control group and 123 genera in the GF_SPFcon group, 81 of which were shared between the two groups (Fig. 6e). Beta diversity analysis using Principal Coordinates Analysis (PCoA) also showed no significant differences (Fig. 6f).

Fig. 6.

Diversity analyses of the Oral microbiome in Specific Pathogen Free Control (SPF_Control) Group and Germ-free Control (GF_SPFcon) Group. (a) Alpha diversity of Simpson index; (b) Alpha diversity of Shannon index; (c) Alpha diversity of Chao index; (d) Alpha diversity of Ace index; (e) Venn diagram showing the specific and shared Genus between the SPF_Control group and GF_SPFcon group; (f) PCoA of community structures from SPF_Control group and GF_SPFcon group. (ns: P > 0.05)

The significantly different abundances between the two groups were analyzed by the Wilcoxon rank sum test from the phylum to genus levels (two-sided test, confidence interval 0.95). The findings indicated no significant differences in the abundance of bacterial genera.

Dysbiotic oral microbiome induces dental caries

Mice in the GF_SPFcon group did not develop dental caries (Fig. 7a-c). Mice in the GF_SPFsuc group, following inoculation with saliva and dental plaque from the SPF_Sucrose cohort, exhibited the development of dental caries (Fig. 7d-f).

Fig. 7.

Germ-free (GF) mice Micro-CT. (a-c) Germ-free Control (GF_SPFcon) group Micro-CT (n = 3); (b-d) Germ-free Sucrose (GF_SPFsuc) group Micro-CT (n = 3). (Dental caries indicated by the red circles) Scale bar: 1 mm

Discussion

Dental caries is a biofilm-mediated, sugar-induced multifactorial dynamic disease that leads to demineralization and remineralization of the hard tissues of the teeth [30]. Frequent intake of free sugars can accelerate the occurrence of caries [31, 32], and sucrose is one of the most cariogenic carbohydrates [33]. This study improved the traditional caries model establishment method [27] by feeding mice with the National Institutes of Health cariogenic diet 2000 and 5% sucrose water without the addition of bacteria.

Micro-CT examination of the mandibles of SPF mice on a sucrose diet revealed the presence of distinct carious lesions, indicating that a sucrose diet can lead to the occurrence of dental caries in mice. Saliva and dental plaque from both the SPF_Control group and the SPF_Sucrose group were subjected to 16 S rRNA gene sequencing. The Alpha diversity indices between the SPF_Control and SPF_Sucrose groups indicated no significant difference in oral microbial diversity and richness between the two groups. Some studies have suggested that the alpha diversity of the oral microbiome in patients with dental caries is reduced [34, 35]. However, other studies have indicated no difference in the alpha diversity of the oral microbiome between individuals with and without dental caries [36, 37]. The discrepancy in the results may be due to factors such as the age, lifestyle, and dietary habits of the subjects, or it may be due to the varying degrees of dental caries among the patients. Some research has pointed out that as the severity of dental caries in patients increases, there is a declining trend in oral bacterial diversity [35]. PCoA analysis based on the Bray-Curtis distance algorithm showed differences in the composition of the bacterial communities between the two groups, with changes in species composition, indicating that a sucrose diet has affected the relative abundance of the oral microbiome in mice, which is similar to the results of a previous in vitro study [38].

The Wilcoxon rank sum test was performed to compare the composition of the microbial communities in the two groups of SPF mice. At the phylum level, the predominant components of the microbial communities in both groups were Firmicutes, Proteobacteria, an unclassified bacterium, Actinobacteriota, and Bacteroidota, with no significant variation in relative abundance observed. Despite differences between the Oral microbiomes of humans and mice, the core microbiome retains a degree of similarity [39, 40]. The only phylum that exhibited a significant difference was Verrucomicrobiota. However, it was present in low relative abundance in both groups and has not been detected in the oral cavity, although it is frequently identified in the stomach and intestines [41, 42].

While the overall microbial community structure did not significantly differ between the SPF control and SPF sucrose groups, further analysis revealed a trend towards reduced Streptococcus abundance in the SPF sucrose group. Although this reduction did not reach statistical significance, it may indicate a dietary effect on this specific microbial genus. The relative abundance of Streptococcus was not significantly different between the two groups, which aligns with prior research outcomes [43–45]. This could be attributed to the fact that the Streptococcus genus encompasses a variety of species, including S. mutans, S. sanguis, S. salivarius, and S. gordonii, each with distinct roles in dental caries progression and potential antagonistic interactions. For instance, S. sanguis is capable of producing hydrogen peroxide to suppress the growth of S. mutans, while S. mutans secretes mutacins I and IV to inhibit the viability of S. sanguis [46]. S. gordonii can similarly produce hydrogen peroxide to curb the growth of S. mutans [47], S. mutans releases mutacin IV to eliminate adjacent S. gordonii and assimilate the DNA released by S. gordonii [48]. These interactions likely contribute to the overall maintenance of a stable relative abundance of the Streptococcus genus.

We discovered a genus with a notably elevated relative abundance-Gemella, a finding that corroborates the outcomes of an in vitro study [38]. Gemella has been reported to overgrow in patients with active dental caries [49, 50], and the isolated Gemella species have demonstrated a high capacity for auto-aggregation in experimental settings, which is associated with the generation and progression of dental plaque and biofilms [51]. Consequently, the fluctuation in the Gemella genus within the oral microbiome may correlate with states of health and disease. Differences at the phylum and genus levels suggest that the oral microbiome of caries-prone mice is in a state of dysbiosis.

Saliva and dental plaque from the two groups of SPF mice were inoculated into two groups of GF mice. Due to the lower immune resistance of GF mice, those inoculated with cariogenic bacterial communities succumbed during the experimental process. Thus, we were unable to collect saliva and dental plaque from the GF_SPFsuc group. We proceeded to collect saliva and dental plaque from the SPF_Control group and the GF_SPFcon group for 16 S rRNA gene sequencing. There was no difference in both Alpha and Beta diversity indices between the two groups. The Wilcoxon rank sum test also did not identify any differentially abundant bacterial genera. These findings suggest that the oral microbiome was successfully colonized from SPF mice into the oral cavity of GF mice. Micro-CT scanning analysis of the mandibles of the two groups of GF mice revealed dental caries in the GF_SPFsuc group. The results indicate that the cariogenic bacterial community, that is, a dysbiotic oral microbiome, can induce the occurrence of dental caries in GF mice.

Conclusion

This study demonstrates that a sucrose diet can lead to the development of dental caries in mice, accompanied by changes in the composition of the oral microbiome. The presence of cariogenic bacterial communities, or dysbiosis of the oral microbiome, is characterized by significant alterations in the relative abundance of certain bacterial genera, which may provide a novel approach for assessing the onset of dental caries. The inoculation of dysregulated oral microbiome into germ-free mice illustrates that an imbalanced microbial community can induce the occurrence of dental caries, laying the groundwork for further research into the etiological factors of the disease.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

The 16 S rRNA gene sequencing service was provided by Majorbio Bio-Pharm Technology Co. Ltd. (Shanghai, China).

Abbreviations

- SPF

Specific Pathogen Free

- GF

Germ-free

- Micro-CT

Micro-computed tomography

- SPF_Control

Specific Pathogen Free Control

- SPF_Sucrose

Specific Pathogen Free sucrose diet

- GF_SPFcon

Germ-free Control

- GF_SPFsuc

Germ-free Sucrose

Author contributions

R.L: Conducted all experiments and date analysis, and wrote the manuscript. Y.S.L and J.L.Y: Conducted date analysis, and wrote the manuscript. Y.K.F: Conducted date analysis. Q.G and L.C: Conducted revised the manuscript. J.Z.H and M.Y.L: Conducted conceived and designed the experiments, and revised the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This manuscript was supported by the Sichuan Science and Technology Program No.2021YFH0188 (ML) and No.2020YJ0240 (JH).

Data availability

All data supporting this manuscript are available on request from the corresponding author.Sequence data that support the findings of this study have been deposited in the SRA database with the primary accession code PRJNA1142760.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study was conducted in accordance with the policy of Sichuan University and West China Hospital of Stomatology, and the animal protocol was approved by the Ethical Committee of West China Hospital of Stomatology, Sichuan University (Chengdu, China) (Project identification code: WCHSIRB-D-2021-548, approval date: 11 November 2021). Clinical trial number: not applicable. We have already obtained informed consent from the owner(s) to use the animals in our study.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Jinzhi He, Email: hejinzhi@scu.edu.cn.

Mingyun Li, Email: limingyun@scu.edu.cn.

Reference

- 1.Lamont RJ, Koo H, Hajishengallis G. The oral microbiota: dynamic communities and host interactions. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2018;16(12):745–59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ribeiro AA, Paster BJ. Dental caries and their microbiomes in children: what do we do now? J Oral Microbiol. 2023;15(1):2198433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Aas JA, Griffen AL, Dardis SR, et al. Bacteria of dental caries in primary and permanent teeth in children and young adults. J Clin Microbiol. 2008;46(4):1407–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Krishnan K, Chen T, Paster BJ. A practical guide to the oral microbiome and its relation to health and disease. Oral Dis. 2017;23(3):276–86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.da Costa Rosa T, de Almeida Neves A, Azcarate-Peril MA, et al. The bacterial microbiome and metabolome in caries progression and arrest. J Oral Microbiol. 2021;13(1):1886748. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.He J, Tu Q, Ge Y, et al. Taxonomic and functional analyses of the Supragingival Microbiome from caries-affected and caries-Free hosts. Microb Ecol. 2018;75(2):543–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bostanci N, Grant M, Bao K, et al. Metaproteome and metabolome of oral microbial communities. Periodontol 2000. 2021;85(1):46–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Li Y, Cheng L, Li M. Effects of Green Tea Extract Epigallocatechin-3-Gallate on oral diseases: a narrative review. Pathogens. 2024;13(8):634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rosier BT, Marsh PD, Mira A. Resilience of the oral microbiota in Health: mechanisms that prevent dysbiosis. J Dent Res. 2018;97(4):371–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Morikava FS, Fraiz FC, Gil GS, de Abreu MHNG, Ferreira FM. Healthy and cariogenic foods consumption and dental caries: a preschool-based cross-sectional study. Oral Dis. 2018;24(7):1310–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bowen WH, Burne RA, Wu H, Koo H. Oral biofilms: pathogens, Matrix, and Polymicrobial interactions in Microenvironments. Trends Microbiol. 2018;26(3):229–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Radaic A, Kapila YL. The oralome and its dysbiosis: new insights into oral microbiome-host interactions. Comput Struct Biotechnol J. 2021;19:1335–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wei Y, Qiu W, Zhou XD, et al. Alanine racemase is essential for the growth and interspecies competitiveness of Streptococcus mutans. Int J Oral Sci. 2016;8(4):231–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chen X, Daliri EB, Tyagi A, Oh DH. Cariogenic Biofilm: Pathology-related phenotypes and targeted therapy. Microorganisms. 2021;9(6):1311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mosaddad SA, Tahmasebi E, Yazdanian A, et al. Oral microbial biofilms: an update. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2019;38(11):2005–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yang B, Song B, Liang J, et al. pH-responsive DMAEM Monomer for dental caries inhibition. Dent Mater. 2023;39(5):497–503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Higham SM, Edgar WM. Human dental plaque pH, and the organic acid and free amino acid profiles in plaque fluid, after sucrose rinsing. Arch Oral Biol. 1989;34(5):329–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Stephan RM. Intro-oral hydrogen-ion concentrations associated with dental caries activity. J Dent Res. 1944;23:257–66. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bowen WH. The Stephan Curve revisited. Odontology. 2013;101(1):2–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hsiao J, Wang Y, Zheng L, et al. In vivo Rodent models for studying Dental Caries and Pulp Disease. Methods Mol Biol. 2019;1922:393–403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nomura R, Matayoshi S, Otsugu M, Kitamura T, Teramoto N, Nakano K. Contribution of severe Dental Caries Induced by Streptococcus mutans to the pathogenicity of infective endocarditis. Infect Immun. 2020;88(7):e00897–19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.AL-WAFI H, ALI A S, LOO C Y, et al. Potential role of thymoquinone in management of Dental Caries and Gingival disease in the animal model. Bioscience Res. 2021;18(3):2142–254. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zhao Y, Shuen TWH, Toh TB, et al. Development of a new patient-derived xenograft humanised mouse model to study human-specific tumour microenvironment and immunotherapy. Gut. 2018;67(10):1845–54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Liao X, Song L, Zeng B, et al. Alteration of gut microbiota induced by DPP-4i treatment improves glucose homeostasis. EBioMedicine. 2019;44:665–74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wang X, Wu C, Wei H. Humanized germ-free mice for investigating the intervention effect of commensal microbiome on Cancer Immunotherapy. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2022;37(16–18):1291–302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zheng H, Xie T, Li S, Qiao X, Lu Y, Feng Y. Analysis of oral microbial dysbiosis associated with early childhood caries. BMC Oral Health. 2021;21(1):181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Liu S, Wu T, Zhou X, et al. Nicotine is a risk factor for dental caries: an in vivo study. J Dent Sci. 2018;13(1):30–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wang Q, Garrity GM, Tiedje JM, Cole JR. Naive bayesian classifier for rapid assignment of rRNA sequences into the new bacterial taxonomy. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2007;73(16):5261–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Schloss PD, Westcott SL, Ryabin T, et al. Introducing mothur: open-source, platform-independent, community-supported software for describing and comparing microbial communities. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2009;75(23):7537–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hardiman O, Al-Chalabi A, Chio A, et al. Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2017;3:17085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Giacaman RA. Sugars and beyond. The role of sugars and the other nutrients and their potential impact on caries. Oral Dis. 2018;24(7):1185–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lundtorp Olsen C, Markvart M, Vendius VFD, Damgaard C, Belstrøm D. Short-term sugar stress induces compositional changes and loss of diversity of the supragingival microbiota. J Oral Microbiol. 2023;15(1):2189770. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cai JN, Choi HM, Jeon JG. Relationship between sucrose concentration and bacteria proportion in a multispecies biofilm. J Oral Microbiol. 2021;13(1):1910443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Jiang W, Ling Z, Lin X, et al. Pyrosequencing analysis of oral microbiota shifting in various caries states in childhood. Microb Ecol. 2014;67(4):962–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Xiao C, Ran S, Huang Z, Liang J. Bacterial diversity and community structure of Supragingival Plaques in adults with Dental Health or Caries revealed by 16S pyrosequencing. Front Microbiol. 2016;7:1145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Jiang Q, Liu J, Chen L, Gan N, Yang D. The oral Microbiome in the Elderly with Dental Caries and Health. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 2019;8:442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zheng Y, Zhang M, Li J, et al. Comparative analysis of the Microbial profiles in Supragingival Plaque samples obtained from twins with discordant caries phenotypes and their mothers. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 2018;8:361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Du Q, Fu M, Zhou Y, et al. Sucrose promotes caries progression by disrupting the microecological balance in oral biofilms: an in vitro study. Sci Rep. 2020;10(1):2961. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zaura E, Keijser BJ, Huse SM, Crielaard W. Defining the healthy core microbiome of oral microbial communities. BMC Microbiol. 2009;9:259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Cherkasov SV, Popova LY, Vivtanenko TV, et al. Oral microbiomes in children with asthma and dental caries. Oral Dis. 2019;25(3):898–910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Fujio-Vejar S, Vasquez Y, Morales P, et al. The gut microbiota of healthy Chilean subjects reveals a high abundance of the Phylum Verrucomicrobia. Front Microbiol. 2017;8:1221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Gharechahi J, Sarikhan S, Han JL, Ding XZ, Salekdeh GH. Functional and phylogenetic analyses of camel rumen microbiota associated with different lignocellulosic substrates. NPJ Biofilms Microbiomes. 2022;8(1):46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ling Z, Kong J, Jia P, et al. Analysis of oral microbiota in children with dental caries by PCR-DGGE and barcoded pyrosequencing. Microb Ecol. 2010;60(3):677–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Jiang S, Gao X, Jin L, Lo EC. Salivary microbiome diversity in Caries-Free and caries-affected children. Int J Mol Sci. 2016;17(12):1978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Yang Z, Cai T, Li Y, Jiang D, Luo J, Zhou Z. Oral microbial communities in 5-year-old children with versus without dental caries. BMC Oral Health. 2023;23(1):400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kreth J, Merritt J, Shi W, Qi F. Competition and coexistence between Streptococcus mutans and Streptococcus sanguinis in the dental biofilm. J Bacteriol. 2005;187(21):7193–203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kreth J, Zhang Y, Herzberg MC. Streptococcal antagonism in oral biofilms: Streptococcus sanguinis and Streptococcus gordonii interference with Streptococcus mutans. J Bacteriol. 2008;190(13):4632–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kreth J, Merritt J, Shi W, Qi F. Co-ordinated bacteriocin production and competence development: a possible mechanism for taking up DNA from neighbouring species. Mol Microbiol. 2005;57(2):392–404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Simón-Soro A, Mira A. Solving the etiology of dental caries. Trends Microbiol. 2015;23(2):76–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Li Y, Zou CG, Fu Y, et al. Oral microbial community typing of caries and pigment in primary dentition. BMC Genomics. 2016;17:558. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Shen S, Samaranayake LP, Yip HK. Coaggregation profiles of the microflora from root surface caries lesions. Arch Oral Biol. 2005;50(1):23–32.The font overlaps. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All data supporting this manuscript are available on request from the corresponding author.Sequence data that support the findings of this study have been deposited in the SRA database with the primary accession code PRJNA1142760.