Summary

Protein-RNA interactions play pivotal roles in regulating transcription, translation, and RNA metabolism. Characterizing these interactions offers key insights into RNA dysregulation mechanisms. Here, we introduce Reformer, a deep learning model that predicts protein-RNA binding affinity from sequence data. Trained on 225 enhanced cross-linking and immunoprecipitation sequencing (eCLIP-seq) datasets encompassing 155 RNA-binding proteins across three cell lines, Reformer achieves high accuracy in predicting binding affinity at single-base resolution. The model uncovers binding motifs that are often undetectable through traditional eCLIP-seq methods. Notably, the motifs learned by Reformer are shown to correlate with RNA processing functions. Validation via electrophoretic mobility shift assays confirms the model’s precision in quantifying the impact of mutations on RNA regulation. In summary, Reformer improves the resolution of RNA-protein interaction predictions and aids in prioritizing mutations that influence RNA regulation.

Keywords: RNA-protein interaction, mutation effect, deep learning, transformer, RNA-binding proteins, RBP, eCLIP-seq, single-base resolution, motif discovery, pathogenic variants, motif enrichment

Graphical abstract

Highlights

-

•

Reformer accurately predicts RNA-protein binding at single-base resolution

-

•

Captures diverse motifs, improving motif discovery beyond traditional methods

-

•

Reveals how mutations affect RNA-protein interactions and regulation

-

•

Prioritizes mutations affecting RNA regulation in disease contexts

The bigger picture

RNA-binding proteins (RBPs) are vital regulators of gene expression, controlling RNA splicing, stability, and localization. Dysregulation of RBPs is increasingly recognized as a key factor in the onset and progression of many diseases, making them potential therapeutic targets. While existing methods can map RBP binding sites, they may miss subtle, long-range interactions and motifs outside signal peaks, limiting insights into RNA regulation and mutation effects. Advanced computational tools that combine high-resolution RBP binding site predictions with functional validation, like the one presented in this work, could help drive progress in personalized medicine, RNA-targeted therapeutics, and synthetic biology.

The Reformer model, a transformer-based deep learning approach, predicts RNA-protein interactions at single-base resolution using sequence data alone. This high-resolution model enhances motif discovery, detects mutations that impact RNA regulation, and aids in identifying pathogenic variants linked to RNA-binding-protein dysregulation. Reformer offers a robust framework for studying RNA-protein interactions and prioritizing disease-related mutations.

Introduction

RNA-binding protein (RBPs) are crucial regulators of gene expression and proteogenesis, mediating key aspects of RNA processing, including splicing, stability, localization, editing, and translation.1 Dysregulation of RBP function is linked to various genetic diseases, such as autoimmunity, neuropathic disorders, and cancer.2,3,4,5 Thus, characterizing RBP-RNA interactions from sequence data provides valuable insights into the mechanisms underlying RNA dysregulation and related diseases.

Deep learning methods have emerged as powerful tools for modeling protein-RNA interactions. Early models like DeepBind utilized convolutional neural networks to predict the binding affinity,6 while RNAProt employed recurrent neural networks.7 More recent approaches, such as PrismNet and HDRNet, integrate RNA sequence and structure information using residual networks to predict RBP binding patterns.8,9 However, these models treated RNA-protein interactions as a binary classification (BC) task, distinguishing binding from non-binding regions. Crucially, they lacked the ability to predict RBP-RNA interactions at single-base resolution and typically focused on binding regions around 100 bp,7,9 neglecting the influence of surrounding contextual information known to affect RBP binding.10

In this study, we present Reformer, a transformer-based model11 designed to enhance prediction resolution and capture the flow of information between binding peaks and their surrounding contexts. Reformer predicts protein-RNA binding affinity at single-nucleotide resolution, focusing specifically on regions with strong binding signals. By framing the problem as a binding affinity prediction from sequence data alone, Reformer delivers precise, base-level insights into RNA-protein interactions. Trained on RNA sequences across 155 RBPs from three cell lines, the model achieves a high correlation between predicted and observed binding peaks derived from enhanced cross-linking and immunoprecipitation sequencing (eCLIP-seq) data. Reformer captures diverse RBP binding patterns within peak regions and surrounding contexts and is capable of detecting deleterious mutations that disrupt RNA-protein interactions, with experimental validation supporting its predictions. This model provides a unified framework for characterizing RBP binding and prioritizing mutations that affect RNA regulation at single-base resolution.

Results

Overview of Reformer

We developed Reformer, a deep learning model designed to quantitatively predict RNA-protein binding affinity at single-base resolution from cDNA sequences (Figure 1). The model consists of 12 transformer blocks, each with 12 attention heads (Figure S1). Reformer was trained on a dataset of 225 eCLIP-seq experiments, covering 155 RBPs across three cell lines1 (Figures 1A; Table S1). To identify binding sites, sequences were firstly processed through a binary classifier, Reformer-BC (Figure 1B). Positive sequences identified by Reformer-BC were then further analyzed by Reformer (Figure 1C). The transformer layers computed a weighted sum of representations across all bases, allowing the model to collect information from relevant regions throughout the sequence (Figure 1D). The model outputs binding affinities for each base via a regression layer (Figure 1C).

Figure 1.

Overview of Reformer

(A) Reformer is applied to predict protein-RNA binding affinity using eCLIP-seq data.

(B) Reformer-BC first classifies sequences into binary categories, with positive sequences undergoing single-base resolution analysis for binding affinity prediction.

(C) Reformer architecture is based on a bidirectional encoder designed to predict RNA-protein binding affinity using cDNA sequence as inputs.

(D) Reformer’s self-attention mechanism allows for the calculation of attention weights at individual bases relative to the peak region.

(E and F) Downstream applications of the self-attention mechanism, including motif enrichment analysis and a compilation of motif signatures.

(G) The trained Reformer model is further applied to predict the effects of mutations on RBP binding affinity.

We demonstrate the utility of Reformer in three key applications: (1) conducting motif enrichment analysis in regions of high attention (Figure 1E), (2) generating motif signatures from these regions to construct canonical motifs (Figure 1F), and (3) predicting effects of mutations on RNA-RBP binding by assessing changes in the predicted binding affinity (Figure 1G). These applications offer insights into RNA-RBP regulatory mechanisms and facilitate fine-mapping of human diseases associated with RBP dysregulation.

Reformer accurately predicts RNA-RBP binding affinity at base resolution

For the BC task, Reformer-BC outperformed HDRNet,8 DeepCLIP,12 Prismnet,9 and DEEPBind,6 achieving significantly higher AUC scores on the BC-test set (paired t test, p < 0.05; Figure S2). At single-base resolution, evaluation using the single-base resolution (SR)-test set showed a Spearman correlation of 0.63 between the predicted and actual affinities (Figure 2A). For individual sequences, Reformer demonstrated high predictive precision (mean Spearman r = 0.65), indicating its ability to capture binding affinity variations within the same sequence (Figure 2B). Reformer also captures cell-type-specific binding patterns, with a significantly higher Spearman correlation for affinities within the same cell line compared to different cell lines (paired t test, p = 2 × 10−10; Figure S3). Additionally, Reformer accurately predicted peak widths and binding strengths (Figure 2C) and the overall binding affinity across both aggregated and individual eCLIP-seq experiments (mean Spearman r = 0.76 and 0.65, respectively; Figures 2D and 2E). The predicted and observed peak affinities showed a strong resemblance to biological replicates (Figure S4), with a difference of 0.61, closely matching the difference between biological repeats (0.60; Figures 2F and 2G; paired t test, p = 0.21). Qualitative analysis further supported the high similarity between predicted and experimentally observed peaks (Figure 2H), reinforcing Reformer’s accuracy in modeling RNA-protein interactions. This comparison highlights the consistency between the predicted and experimentally observed affinities, demonstrating that the predicted values closely resemble the biological replicates, providing further validation for the model’s accuracy in capturing RNA-protein interactions.

Figure 2.

Evaluation of Reformer performance on the SR-test set

(A and B) Spearman correlation between reference and predicted base-level binding affinities (log2(1 + x) transformed normalized coverage): (A) correlation calculated across all sequences and (B) correlation calculated for each individual sequence. Violin and box plots are used to represent the distribution of correlation values. The violin plot shows the density distribution, with width indicating data density, while the box plot displays the median, interquartile range (IQR), and whiskers representing 1.5 × IQR.

(C) Examples of reference and predicted genomic tracks for HNRNPK in the K562 cell line.

(D and E) Spearman correlation between reference and predicted peak-level binding affinity: (D) correlation calculated across all eCLIP-seq experiments and (E) correlation calculated for each individual experiment. Violin and box plots in (E) represent the distribution of correlation values, with the violin plot showing data density and the box plot showing the median, IQR, and whiskers representing 1.5 × IQR.

(F) Violin and boxplots showing binding affinity differences between reference and predicted peaks across eCLIP-seq experiments. The violin plot represents the density distribution of differences, while the box plot displays the median, IQR, and whiskers representing 1.5 × IQR.

(G) Dot and boxplot illustrating binding affinity differences between predicted and reference peaks. Each dot represents a benchmark result from an individual eCLIP-seq experiment. The box plot displays the median, IQR, and whiskers representing 1.5 × IQR. Statistical significance was determined by a paired t test.

(H) Examples of reference, predicted, and biologically replicated genomic tracks of TARDBP in the K562 cell line.

See also Figures S2–S4.

Reformer captures RBP binding motifs

The attention mechanism underlying the transformer architecture11 can be leveraged for sequence element discovery.13 To investigate this, we extracted the regions receiving the highest attention from Reformer for each RBP and assessed whether canonical motifs were enriched in these regions (see methods). Of the 960 validated motifs, 872 were significantly enriched in high-attention regions (Figures 3A and 3B; p < 0.05), compared to 486 motifs enriched in eCLIP-seq peak regions (Figures 3A and 3B; p < 0.05). Notably, 392 motifs identified by Reformer were not detected in the eCLIP-seq peak regions (Figure 3C), yet they were located near the eCLIP-seq peaks (Figures 3D and S5). For instance, the canonical U2AF2 target motif “TTTTT” was located to the left of eCLIP-seq peaks (Figure 3D), the HNRNPL motif “ACAA” surrounded the peaks, and the HNRNPC motif “GGATTC” was found between peaks (Figure S5).

Figure 3.

Enrichment of canonical motifs in regions highly attended by Reformer

(A) Stacked bar plot showing target-specific motifs enriched in eCLIP-seq peaks and Reformer’s high-attention regions. Blue indicates motifs enriched only in eCLIP-seq peaks, red indicates motifs enriched only in Reformer’s highly attended regions, and gray indicates motifs enriched in both regions.

(B) Scatterplot comparing the enrichment score of motifs in eCLIP-seq peaks versus high-attention regions. Each dot represents a motif, with enrichment scores shown as −log10(p value) calculated using the analysis of motif enrichment (AME) algorithm.

(C) Left: total number of motifs enriched exclusively in eCLIP-seq peaks, high-attention regions, and both. Right: corresponding RBPs for motifs enriched exclusively in eCLIP-seq peaks, high-attention regions, and both.

(D) Example of U2AF2 motif enrichment in genome tracks (HepG2). The red frame marks the peak region validated by eCLIP-seq experiments, while the blue frame highlights the high-attention regions of layer1 head2 in Reformer.

(E) Bar plot showing the number of attention heads in which motifs are enriched. Each column represents an eCLIP-seq target, with the stack bars indicating the corresponding motifs of the RBP. The color intensity reflects the number of heads where each motif in enriched.

(F) Example showing the enrichment of different motifs of HNRNPA1 across different attention heads.

See also Figures S5–S7 and Table S2.

Additionally, the majority of motifs (93%, 810/872) were encoded across multiple attention heads, while 7% (n = 62) were recognized by individual heads (Figure 3E; see methods). Each attention head preferentially recognized different motifs (Figures 3E, 3F, and S6), reflecting the diverse recognition capabilities of the attention mechanism.

We further conducted motif discovery using both high-attention regions and eCLIP-seq data, analyzing 23 eCLIP-seq datasets from 17 classical RBPs. Reformer outperformed traditional peak-region-based methods in 20 targets, capturing additional sequence features beyond those identified in peak regions (Figure S7).

Deciphering motif signatures from regions highly attended by Reformer

To elucidate the patterns captured by Reformer, we identified motif signatures from highly attended regions. Specifically, cDNA sequences from these regions were extracted and compiled into a consensus sequence per attention head (see methods), which was considered a motif signature. After excluding duplicates, we identified 78 unique motif signatures (Figure S8). The majority (77/78) were significantly distinct from consensus sequences derived from random regions (p < 0.05; Table S3). Although one motif, TTTTT, did not reach statistical significance (p = 0.06), it remains a well-characterized motif associated with multiple RBPs.14,15,16 These results indicate that the motif signatures represent specific sequence patterns recognized by attention heads.

Using the non-negative matrix factor two-dimensional (2D) deconvolution (NMF2D) algorithm,17 we compared 1,312 canonical motifs against these 78 motif signatures, with 1,038 motifs showing significant similarity to the canonical motifs, as determined by the target of motif to motif (TOMTOM) algorithm (q < 0.05; Table S4). Many canonical motifs were reconstructed using multiple motif signatures at varying intensities. For example, the “GCCAA” motif was constructed using signatures 10 and 75 (Figure 4B), and the “AAAGG” motif of TLR3, “TAATT” of A1CF, and “GGGG” of HNRNPH1 were reconstructed using signatures 18, 42, 49, 61, and 77, each with different intensities (Figure 4C).

Figure 4.

Validation of motif signatures and their relevance to RNA regulation

(A) Motif signatures constructed from high-attention regions.

(B and C) Examples of reconstructing known motifs using motif signatures of varying intensities. The similarity between known and reconstructed motifs was determined using the TOMTOM algorithm with q <0.05 considered significant.

(D) Dot plot illustrating the functional and domain specificity of motif signatures. Circle size represents the average contribution score of a signature to RBPs with similar functions, while color indicates whether a signature is significantly enriched in a specific functional category. Significance was assessed using the Wilcoxon rank-sum test, with p <0.05 deemed significant.

(E and F) Heatmap showing the contribution scores of motif signatures to motifs associated with specific functions.

We further explored the relationship between motif signatures and the functional or domain categories of RBPs (see methods). Signatures 1, 66, and 9 were significantly associated with RBPs containing pumilio homology (PUM) domain, K homology (KH) domain, and RNA recognition motif (RRM) domains, respectively (Figure 4D; Wilcoxon rank-sum test, p < 0.05). Notably, signature 1 (“TAACT”) was strongly linked to the motifs of PUM1 and PUM2 (Figure 4E), consistent with independent findings.18 Additionally, signatures 10, 24, 33, 66, and 61 were enriched in motifs related to spliceosome assembly, RNA modification, 3′ end processing, and telomerase binding (Figure 4D; Wilcoxon rank-sum test, p < 0.05). RBPs within similar functional categories exhibited consistent motif patterns corresponding to their respective motif signatures (Figure 4F). Together, these results suggest that Reformer-decoded motif signatures are closely aligned with RBP functional classifications.

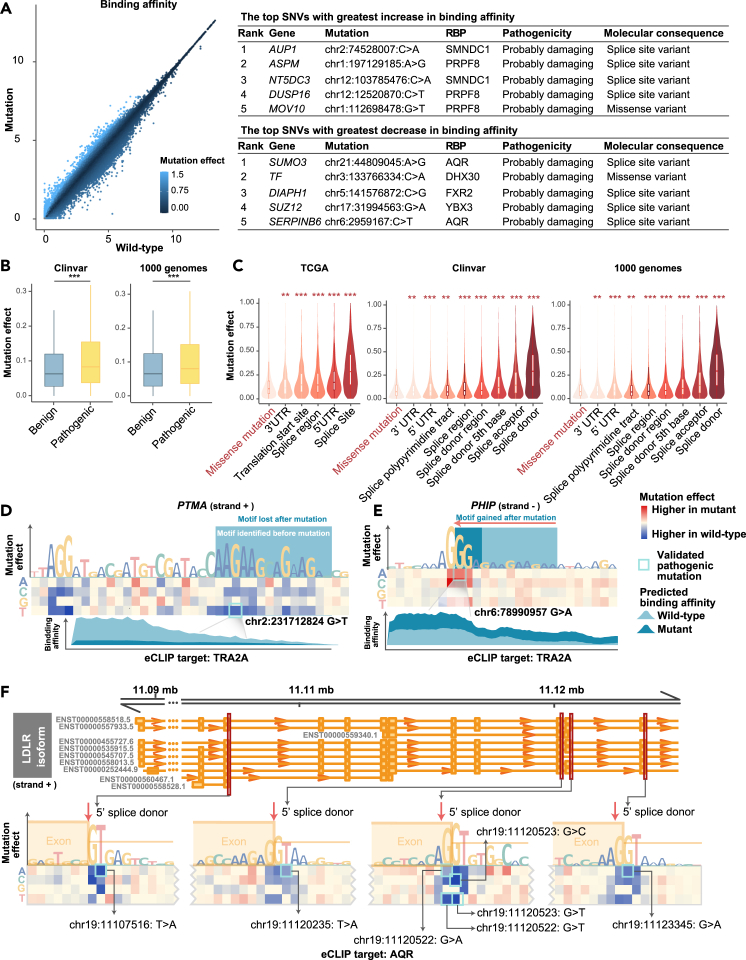

Reformer predicts the effects of RNA mutations on RBP binding

A key application of Reformer is to predict how genetic variations influence RBP interactions. We firstly performed a comprehensive analysis using 553,803 single-nucleotide variants (SNVs) from TCGA, ClinVar, and the 1000 Genomes Project. Reformer was used to evaluate the impact of each SNV on RNA-protein interactions (see methods).19,20 The model showed that the highest-scoring variants were frequently pathogenic or involved in RNA splicing (Figure 5A; Table S5). Expert-curated pathogenic mutations had significantly higher mutation effect scores compared to benign variants (Figure 5B; t test, p < 1 × 10−5). Notably, mutations near splice sites had higher scores than missense mutations (Figure 5C; t test, p <1 × 10−2; Figure S9), and rare splice-site mutations had significantly higher mutational effects compared to common ones (Figure S10; t test, p = 4 × 10−3), suggesting that these mutations are subject to strong negative selection. These findings confirm Reformer’s ability to identify impactful genetic variants.

Figure 5.

Analysis of genomic variants with RNA regulatory potential

(A) Left: predicted binding affinity (log2(1 + x) transformed binding coverage) for wild-type (x axis) and mutated (y axis) sequences. Each dot represents a single-nucleotide variant (SNV), with color density indicating the mutation effect score. Right: top SNVs with the highest mutation effect scores.

(B) Mutation effect scores for benign and pathogenic SNVs, with significance assessed using the Wilcoxon test. ∗∗∗p < 0.001. Box plots display the median, interquartile range (IQR), and whiskers representing 1.5×IQR.

(C) Mutation effect scores for SNVs from different genome locations. The violin plot shows the distribution of mutation effect scores, with the width representing the density of data points. Box plots are overlaid to show the median, interquartile range (IQR), and whiskers representing 1.5×IQR. Significance of the difference in mutation scores between missense and splice-related mutations was assessed using the Wilcoxon test. ∗p < 0.05, ∗∗p < 0.01, and ∗∗∗p < 0.001.

(D–F) Representative examples of SNVs that disrupt RNA regulation. Heatmap shows mutation effects, with known disease-associated SNVs from ClinVar and the 1000 Genomes Project highlighted in blue boxes. Color intensity indicates mutation effect scores. The sequence logo plot height represents the maximum mutation effect score at each position. In (D) and (E), the light blue box indicates motif positions before the mutation, and the dark blue box shows motifs after the mutation. Peaks reflect the predicted impact of clinically validated SNVs (highlighted with blue boxes in the heatmap) on RBP binding affinity.

See also Figures S9–S11 and Table S5.

We then focused on mutations in disease-associated genes. For example, the chr17:43106478A>C (GRCh38) mutation, which increases RBP binding affinity, is located at the donor site of BRCA1 (Figure S11A). This mutation has been linked to tumorigenesis by disrupting BRCA1 function.21 In NF1, high-scoring mutations, such as chr17:31337818G>C (GRCh38) and chr17:31337817A>C (GRCh38), disrupt LIN28B binding, with pathogenic effects confirmed in patients with neurofibroma (Figure S11B).22,23 One prominent example is the chr2:231712824G>T (GRCh38) mutation, which deletes the TRA2A motif (AAGAAGAA), reducing TRA2A binding affinity to RNA (Figure 5D). This mutation was also predicted to be deleterious by PolyPhen and SIFT (Table S5).24,25 Additionally, a gain-of-function mutation creates a TRA2A binding site at the donor site of PHIP (Figure 5E), while the chr19:10681313G>C (GRCh38) mutation in ILF3 disrupts the TRA2A binding site (Figure S11C). The chrX:153690374G>A (GRCh38) variant in SLC6A8 creates a new binding site for HNRNPK, increasing its binding affinity (Figure S11D). Lastly, LDLR and LMNA harbored the highest-scoring mutations, all located at RNA splicing sites (Figures 5F and S11E) and linked to genetic disease.26,27,28 These gene-specific analyses highlight Reformer’s potential to elucidate molecular mechanisms by which mutations alter RNA-protein interactions, contributing to disease development.

Experimental validation of predicted mutations affecting RBP binding

To validate Reformer’s predictions, we performed electrophoretic mobility shift assays (EMSAs) to assess whether pathogenic SNVs predicted to impact PRPF8 binding indeed alter RNA-protein interactions (Figures 6A and 6B; Table S6). For each SNV, we synthesized paired Cy3-labeled RNA probes with either the wild-type or mutant allele. Increasing amounts of recombinant PRPF8 RNA-binding domain (amino acids 1760–1989; Figure S12) were incubated with a fixed amount of Cy3-labeled RNA, and RNA-protein complexes were separated from the free RNA via non-denaturing gel electrophoresis. Fluorescence imaging was used to quantify the free and bound RNA.

Figure 6.

Experimental validation of SNVs altering RBP binding affinity

(A and B) Predicted mutation effects for SNVs affecting PRPF8 interactions. A heatmap shows the mutation effects of SNVs, with color intensity representing mutation effect scores calculated by Reformer. The sequence logo plot height reflects the maximum mutation effect score at each position. Peaks represent the predicted influence of clinically validated SNVs (highlighted with blue boxes in the heatmap) on RBP binding affinity.

(C and D) Left: electrophoretic mobility shift assays (EMSAs) showing PRPF8 binding to RNA substrates, with increasing amount of RBPs. Right: quantification of the proportion of RBP-bound RNA.

(E) Predicted mutation effects for SNVs affecting U2AF2 interaction. The heatmap and sequence logo plot are presented similarly to PRPF8, highlighting the predicted influence of SNVs on U2AF2 binding affinity.

(F) Left: EMSA results of U2AF2 binding to RNA substrates, with increasing amounts of RBPs. Right: quantification of RBP-bound RNA.

Three independent experiments are shown. Data are presented as mean ± SD. ∗p < 0.05, ∗∗p < 0.01, and ∗∗∗p < 0.001, analyzed with a two-way ANOVA test.

See also Figure S12 and Tables S6 and S7.

Consistent with Reformer’s predictions, the mutant ALDH3A2 RNA showed increased PRPF8 binding compared to the wild-type allele, while the mutant GPC3 RNA exhibited reduced PRPF8 binding (p < 0.05; Figures 6C and 6D; Table S7). Similarly, we confirmed that a pathogenic SNV predicted to have a high impact significantly reduced the binding of U2AF2 (amino acids 150–462; Figure S12) to its RNA substrate (Figures 6E and 6F; Table S7). These results demonstrate Reformer’s accuracy in predicting the effects of specific SNVs on RNA-protein interactions, highlighting its potential for identifying candidate mutations for further investigation.

Discussion

Characterizing protein-RNA interactions to unravel the regulatory mechanisms of RBPs has been a long-standing challenge. To address this, we developed Reformer, a model that predicts RNA-protein binding at single-base resolution. Leveraging the attention mechanism, Reformer effectively captures interactions between peaks and surrounding regions, improving the prediction of RBP- and cell-type-specific binding affinities. Our experimental validation demonstrates that Reformer accurately quantifies the effects of mutations on RBP regulation. We anticipate that Reformer will significantly enhance our understanding of RNA regulatory mechanisms, particularly those related to pathogenic mutations.

Our data-centric approach does not rely on predefined biological features, such as peak clustering or flanking regions. Instead, Reformer autonomously identifies motif enrichment in both peak and flanking regions, a finding consistent with previous studies,29 highlighting the importance of considering broader sequence contexts for motif discovery. This underscores Reformer’s ability to uncover biologically relevant patterns without prior knowledge, positioning it as a powerful tool for advancing the study of RNA-protein interactions.

Reformer also provides insights into the rules governing RNA-RBP interactions. We generated reference motif signatures based on the consensus sequences identified by the model, showing that canonical motifs can be reconstructed through these signatures (Figure 4B). For example, signature 32 (TAAAA) is associated with RNA-modifying proteins such as HNRNPA2B1, SRSF3, SRSF10, and A1CF (Figure 4F), suggesting that this signature represents a common binding pattern for RNA modification proteins. Further exploration of these motif signatures may shed light on the underlying mechanisms of RBP regulation.

The mechanisms underlying numerous pathogenic mutations remain poorly understood.20 Our study focuses on mutations predicted to disrupt RNA binding with PRPF8, a protein at the catalytic core of the spliceosome.30 Notably, two mutations (rs2084819840 and rs1057517739), linked to significant protein dysfunction,31 were predicted to have the greatest effect on RNA binding. EMSA experiments confirmed that these mutations altered PRPF8-RNA binding (Figures 6A–6D), revealing their pathogenicity. We also investigated mutations affecting U2AF2, a key pre-mRNA splicing factor.32 The mutation most strongly predicted to disrupt U2AF2 binding affinity has been confirmed to be associated with ataxia-oculomotor apraxia syndrome (rs1563963464), and EMSA confirmed its impact on U2AF2-RNA interactions (Figures 6E and 6F). These findings offer valuable insights into the molecular mechanisms by which these mutations contribute to disease.

Reformer presents several advantages. First, it uses only sequence information as input, simplifying the model and broadening its applicability compared to methods that rely on both sequence and structure.9 As more experimental data become available,1 Reformer has the potential to characterize RNA-protein interactions over a wider range of RBPs and cellular conditions. Second, Reformer predicts binding affinity at single-base resolution, offering more precise insights than previous methods focused on distinguishing binding from non-binding sites.6,9,12 Third, Reformer fits all eCLIP-seq targets with a single model, reducing training costs compared to previous models.6,12 Finally, by expanding the receptive field to 512 bp, Reformer captures long-range contextual information compared to previously studies that focused on peak regions of about 100 bp,6,9,12 thus enhancing its capacity to identify motifs and prioritize pathogenic variants.

Despite its advantages, Reformer has room for improvement. Enhancing the quality of experimental data1 and expanding the receptive field for long-range contextual learning13 would likely improve its performance. Additionally, Reformer’s current architecture may not fully capture the diversity of RNA-protein interactions across different biological contexts. With increased experimental data, its compatibility with various RBPs and conditions will expand. Finally, its sensitivity to genetic mutations could be enhanced by fine-tuning on well-annotated mutation datasets.

We expect Reformer to facilitate the discovery of motifs and the mapping of pathogenic mutations to their effects on RBP regulation. The pre-trained models are publicly available to support these applications. We hope Reformer will contribute to a better understanding of RBP regulatory mechanisms and foster new approaches to disease diagnosis and therapeutic development.

Methods

RBP binding data collection and processing

eCLIP-seq is a high-throughput technique used to identify RNA-protein binding sites genome wide. This is achieved by cross-linking RNA and proteins, followed by immunoprecipitation and sequencing to map binding regions.33 We collected 225 eCLIP-seq experiments from the Encyclopedia of DNA Elements (ENCODE) repository34 before March 2021. These eCLIP-seq experiments include targets from 155 RBPs across three cell lines (see Table S1). Experimental replicates of eCLIP-seq were collected from the ENCODE repository up to October 2022. Among the datasets, five targets (Table S1) have biological replicates available in the ENCODE database, which were used for further validation and comparison.

In eCLIP-seq, fold enrichment coverage is determined by dividing the coverage of RNA-protein interactions in the experimental group by the coverage in the control group, allowing the identification of enriched binding regions. We extracted the fold enrichment coverage for the eCLIP-seq sequences and mapped the peaks to GRCh38.p5 reference sequences. To normalize fold change coverages for each eCLIP-seq experiment, we divided the absolute fold change coverage by the total coverage sum and then multiplied it by 1 × 106. Peak coverages exceeding 2,500 were capped at 2,500. Binding affinity was defined as log2(1 + normalized fold change coverage), with peaks identified as regions with a binding affinity of at least 3 and a −log10(p value) of at least 5, compared to a size-matched control.33 Binding sites were standardized to 511 nucleotides, with shorter regions symmetrically extended from the midpoint and longer regions trimmed symmetrically to this length. Chromosomes were randomly partitioned into SR-training, SR-validation, and SR-test sets, containing 872,618, 23,633, and 94,713 sequences, respectively (Table S1).

For each eCLIP-seq target, in addition to the identified binding sequences, we randomly selected sequences from the transcriptome that did not overlap with any binding sites to serve as negative samples. The number of negative samples matched the number of positive samples, with all sequences standardized to a length of 511 nucleotides. Chromosomes were randomly divided into BC-training, BC-validation, and BC-test sets, consisting of 1,745,538, 42,022, and 180,040 sequences, respectively.

Model architecture of reformer

We used a bidirectional encoder representation from transformers35 for RNA-protein binding prediction. Reformer consists of three key components: (1) a sequence encoder layer, (2) 12 transformer layers, and (3) a linear layer for predicting binding affinity.

The model takes a cDNA sequence with a maximum length of 511 bp as input and predicts the binding affinity at base resolution as output. Each sequence is represented by the nucleotides A, T, C, and G. To tokenize the sequences, we used a 3-mer representation and added the corresponding eCLIP-seq target name as a token before the sequence. Additionally, a special classification (CLS) token was placed at the beginning of the sequence, and a special separator (SEP) token at the end. For example, the DNA sequence “ATCGA” from the SRSF1 target of the K562 cell line was tokenized with six tokens: {[CLS], SRSF1&K562, ATC, TCG, CGA, [SEP]}.

Each token was then embedded into a numerical vector, creating a matrix (M) representation of the sequence. We also incorporated position information by adding absolute position embeddings to the network. These position embeddings were represented as trainable parameters, randomly initialized, and updated during training. The token embeddings and position embeddings were combined and passed through the transformer layers for further processing.

Reformer consists of 12 transformer layers, each with 12 attention heads and 768 hidden units, designed for learning protein-RBP interactions. The transformer layer captures token-token interaction information using a multi-head self-attention mechanism.36 For a given input, the self-attention mechanism assigns an attention weight, denoted as α i,j > 0, to each token pair (i,j), where ∑ j α i,j = 1. The attention in the transformer is bidirectional, meaning it considers relationships between tokens in both directions.

The attention weights α i,j are computed using the scaled dot product of the query vector of token i (Q) and the key vector of token j (K), followed by a softmax operation. These attention weights are then used to generate a weighted sum of the value vectors (V), calculated as

where d k is the dimension of K. In a multi-layer, multi-head setting, the attention scores vary across layers and heads, enabling the model to capture complex, multi-level interactions between tokens in the sequence.

For Reformer, the linear layer predicted the binding affinity for each of the 509 bp sequence, trimming the last 2 bases on the right side, as they were not fully tokenized. The predicted values were then passed through a rectified linear unit (ReLU) activation function, which returns zero for negative input and the input value itself for non-negative inputs,

and a dropout rate of 0.1 was applied to both the transformer layers and the linear layer to prevent overfitting. The detailed model architecture is shown in Figure S1.

Reformer-BC was incorporated as an initial binary classifier to distinguish binding sites from non-binding sites, filtering out sequences unlikely to exhibit protein-RNA interactions. This step reduces noise in the data, allowing the main model, Reformer, to focus on predicting binding affinity at single-base resolution within regions of interest. Incorporating Reformer-BC improves overall prediction accuracy and efficiency by enabling Reformer to concentrate on refining the binding affinity prediction specifically for high-affinity binding sites.

For Reformer-BC, we replaced the final regression layer of Reformer with a linear layer designed for BC. A sigmoid activation function was applied to produce the probability for BC:

Model training and evaluation

Reformer was initialized using parameters from a pre-trained model37 and trained with the SR-training set. The model was optimized to minimize the mean squared error (MSE) loss function, defined as the squared difference between the reference binding affinity (Y) and the predicted affinity (I):

where Y represents the true binding affinity measured from experimental data and I represents the predicted binding affinity generated by Reformer for each base. Reformer was trained at a learning rate of 2 × 10−5 for 30 epochs using the mini-batch stochastic gradient descent algorithm,38 with a weight decay of 1 × 10−4. The model was implemented using PyTorch (v.1.7.1) and the transformers library (v.4.10.0), and it was trained on an NVIDIA DGX A100 system with 8 GPUs, each with 40 GB of memory.

We utilized the SR-validation set to tune the hyperparameters and the SR-test set to evaluate the model’s performance. For Reformer, we employed two evaluation metrics to assess performance: (1) at base resolution, we calculated the Spearman correlation between the log2(1 + x) transformed measured and predicted the base coverage and (2) at the sequence level, we calculated the Spearman correlation between the measured and predicted peak binding affinities, defined as the sum of log2(1 + x) transformed base coverage across the sequence; we also (3) measured the differences between the predicted and measured peak coverage, represented as

where Y and I represent the log2(1 + x) transformed measured and the predicted binding affinity, respectively.

Reformer-BC was trained with the BC-training set with a BC loss function

where Yi is the reference label and Ii is the predicted result. Reformer-BC was trained for 6 epochs using the same hyperparameters as Reformer. Reformer-BC was benchmarked against HDRNet, DEEPBind, PrismNet, and DeepCLIP.6,8,9,12 All models were trained with their default parameters using the BC-training set for fair comparison.

Motif enrichment analysis in regions highly attended by Reformer

For each sequence, we extracted the attention between bases as a 512 × 512 matrix for each attention head (denoted as F i, j, where i and j range from 1 to 512, corresponding to each base in the sequence) using the trained Reformer model. To reduce noise in the attention matrix, we applied average product correlation (APC) regression.39 APC was computed as follows:

where F i, F j, and F represent the sum of attention over the i-th row, j-th column, and entire matrix, respectively.

We defined binding sites as peak regions with a binding affinity greater than 10 and calculated the attention score between the binding sites and other regions using the trained Reformer model. For each base, the attention score was calculated as the sum of attention from that base to all identified binding sites. This attention summation was used to assess how each base attended to the binding regions.

To identify regions highly attended by Reformer, we used a sliding window approach. Each sequence was divided into windows of 10 bp with a 1 bp step size. We summed the attention scores within each window and defined highly attended regions as the top 1% of windows with the highest attention scores. Overlapping windows with at least 1 bp overlap in common were merged iteratively.

We validated whether these highly attended regions were enriched for motifs using the analysis of motif enrichment (AME) algorithm.40 For each eCLIP-seq target, motifs of the corresponding RBP were collected from the ATtRACT database.41 A total of 920 motifs, each less than 10 bp in length, were curated (Table S2). As controls, we randomly selected regions that were not highly attended by Reformer. Motif enrichment analysis was conducted for each motif across all attention heads. For comparison, we also performed motif enrichment analysis in eCLIP-seq peak regions, using non-peak regions within the 511 bp sequence surrounding the peaks as controls. A Fisher’s exact test p < 0.05 was considered significant for motif enrichment.

We performed motif discovery based on high-attention regions. As described previously, high-attention regions were defined for each eCLIP-seq target. Motifs within these regions were identified using the sensitive, thorough, rapid, enrichment motif elicitation (STREME) method. Only motifs that appeared in more than three attention heads were considered for further analysis.

To evaluate the motif discovery accuracy, we compared the motifs discovered in high-attention regions with those identified from traditional peak regions across 23 eCLIP-seq datasets from 17 RBPs. This allowed us to assess how well the high-attention regions captured relevant motifs compared to the conventional peak regions identified through eCLIP-seq data.

Motif signature construction with Reformer

For each attention head in Reformer, we extracted the top 1% of windows with the highest attention scores using the sliding window strategy mentioned above. The window size was set to 5 bp with a step size of 1 bp. For each window, we summed the attention scores for each alphabet (A, C, G, T) at each position and calculated their cross-entropy, which resulted in a position weight matrix (PWM) as a 4 × 5 matrix (p i, j where i = 1, 2, 3, and 4 correspond to A, C, G, and T and j is the site index, 1 ≤ j ≤ 5).

This PWM was used as the motif signature. p values for the motif signatures were calculated using a permutation test, where a test statistic was computed for the motif signature and compared to the distribution of 1,000 test statistics from randomly generated motifs.

We collected 1,312 motifs of ATtRACT database and reconstructed them using the motif signatures through the NMF2D17 algorithm. The NMF2D algorithm was formulated as follows:

where V, Ʌ, W, and H represent the real motif matrix, the reconstructed motif matrix, the motif signature matrix, and the weight matrix, respectively. The objective of NMF2D is to minimize a generalized Kullback-Leibler (KL) divergence to optimize H for reconstructing V:

Vi,j and Ʌ i,j denote the real and reconstructed PWMs for the j-th base in the i-th motif, respectively. p values were calculated using a permutation test, where a test statistic was computed on the motif signature and compared against many permutations of randomly generated signatures.

The similarity between the real motif matrix V and the reconstructed motif matrix Ʌ was measured using the TOMTOM motif similarity algorithm.40 Motifs with a q < 0.05 were considered significant. We validated the motif reconstruction performance for motif signatures ranging from 5 to 10 bp (Table S4), presenting the 5 bp motif signatures in the manuscript.

To investigate whether the motif signatures were associated with specific RNA processing functions, we used the weight matrix H to quantify the contribution of each signature to the motifs. We collected domain and functional annotations of RBPs from previous studies42,43,44,45,46,47,48 and retrieved the corresponding motifs from ATtRACT database.41 Statistical analysis was conducted using the Wilcoxon rank-sum test, with significance defined by a Benjamini-Hochberg adjusted p < 0.05. The motifs with the highest contributions are displayed in Figures 4E and 4F.

Benchmarking mutation effect predictions on saturation mutation data

Disease-related variants were obtained from the ClinVar database,19 the 1000 Genomes Project,20 and TCGA repository as of November 2022. We extracted SNVs for downstream analysis. Variants were selected based on their clinical significance as either pathogenic or benign, and variants with conflicting clinical significance were excluded. A total of 73,022, 84,208, and 396,573 SNVs with curated annotations were retrieved from ClinVar,19 the 1000 Genomes Project,20 and TCGA repository, respectively.

The genome locations of splice sites were extracted from GENCODE genome annotation49 (release 24 of GRCh38). For SNVs in the 1000 Genomes Project, common variants were defined as those with an allele frequency > 1%, while the rare variants were defined as mutations with an allele frequency < 0.1%. To calculate mutation effects, we overlapped the SNP loci with eCLIP-seq binding affinity (log2(1 + normalized fold enrichment coverage) > 10).

For each variant, we evaluated its mutation effect by calculating the change in predicted binding affinity before and after the mutation:

where R and V represent the binding affinity (summation over 100 bp around the mutated nucleotide) before and after the mutation, respectively, as predicted by the trained Reformer.

We validated pathogenic mutations predicted to disrupt RNA binding to PRPF8 using the trained Reformer. Specifically, we focused on mutations from the 1000 Genomes Project where the binding affinity of either the mutant or wild-type RNA to PRPF8 exceeding 150. The top 1 and 3 mutations with the highest predicted impact on PRPF8 binding affinity were selected for experimental validation. Following the same selection process, we experimentally validated the top pathogenic mutation predicted to disrupt RNA binding to U2AF2.

Purification of recombinant human PRPF8 and U2AF2

The cDNA fragments encoding human PRPF8 (amino acids 1760–1989) and U2AF2 (amino acids 150–462) were cloned into the pET28a vector. The PRPF8-pET28a and U2AF2-pET28a expression vectors were transformed into E. coli BL21 (DE3) chemically competent cells (TransGen, CD601-02). Protein expression was induced with 0.1 mM isopropyl β-D-1-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG), and cells were lysed via sonication in ice-cold buffer 1 (25 mM Tris-HCl [pH 7.5], 500 mM NaCl, 5 mM imidazole [pH 7.5], 3 mM 2-mercaptoethanol, 0.1 mM phenylmethanesulfonylfluoride or phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride [PMSF]).

The lysate was centrifuged at 15,000 rpm for 45 min at 4°C. The supernatant was applied to a HIS-Select Nickel Affinity Gel (Sigma, P6611) and washed with buffer 1. The sample was eluted with buffer 2 (25 mM Tris-HCl [pH 7.5], 2,000 mM NaCl, 3 mM 2-mercaptoethanol). The fusion protein was further eluted with buffer 4 (25 mM Tris-HCl [pH 7.5], 500 mM NaCl, 300 mM imidazole [pH 7.5], 3 mM 2-mercaptoethanol).

The concentrated protein was loaded onto a HiTrap Heparin HP column (Cytiva, 17-0407-01) and eluted using a linear gradient of 0.05–1.0 M NaCl. The eluted protein was concentrated by ultrafiltration and visualized using Coomassie brilliant blue staining.

EMSA

DNA substrates labeled with Cy3 (Invitrogen) at the 5′ end (50 nM) were incubated with the indicated amounts of protein in 1× binding buffer (25 mM Tris [pH 7.5], 50 mM NaCl, 5 mM MgCl2, 1 mM DTT, 5% glycerol, and 0.05% Triton X-100) at room temperature for 30 min. The reaction mixture (20 μL total volume) was then mixed with 2 μL of 10× loading dye and resolved on an 8% native acrylamide/Bis gel in cold 0.5× TBE buffer (44.5 mM Tris, 44.5 mM boric acid, and 0.5 mM EDTA [pH 8.3]). Signals were detected using an Alliance Q9 imager, and band intensities were quantified by ImageJ (NIH).

Resource availability

Lead contact

Requests for further information and resources should be directed to and will be fulfilled by the lead contact, Xiangchun Li (lixiangchun@tmu.edu.cn).

Materials availability

All unique reagents generated in this study are available from the lead contact with a completed materials transfer agreement.

Data and code availability

-

•

Our source code is available at GitHub (https://github.com/xilinshen/Reformer) and has been archived at Zenodo.50 A web server of Reformer is available at https://huggingface.co/spaces/XLS/Reformer.

-

•

The eCLIP-seq experiments used in this article are available at the ENCODE repository (https://www.encodeproject.org/). The motifs of RBPs are available at the ATtRACT database (http://attract.cnic.es). Disease-related variants are available at the ClinVar database (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/clinvar/),19 the 1000 Genomes Project (https://www.internationalgenome.org/),20 and TCGA repository (https://portal.gdc.cancer.gov/).

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (32270688 and 31801117), the Program for Changjiang Scholars and Innovative Research Team in University in China (IRT_14R40), the Tianjin Science and Technology Committee Foundation (17JCYBJC25300), and the Chinese National Key Research and Development Project (2018YFC1315600). We want to thank all the researchers for their generosity in making their data publicly available.

Author contributions

X.L., K.C., and L.S. designed and supervised the study. X.L. and X.S. wrote the manuscript. X.L., K.C., L.S., and X.S. revised the manuscript. Y.H., X.W., C.Z., J.L., H.S., and W.W. collected the data. X.S., Y.Y., M.Y., Y.L., and J.Z. processed the data. X.S., X.L., K.C., L.S., Y.Y., M.Y., Y.L., and Y.S. interpreted the results. All authors reviewed and approved the submission of this manuscript.

Declaration of interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Declaration of generative AI and AI-assisted technologies in the writing process

During the preparation of this work, the authors used ChatGPT 4o in order to improve the readability and language of the work. After using this tool, the authors reviewed and edited the content as needed and take full responsibility for the content of the published article.

Published: January 10, 2025

Footnotes

Supplemental information can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.patter.2024.101150.

Contributor Information

Kexin Chen, Email: chenkexin@tmu.edu.cn.

Lei Shi, Email: shilei@tmu.edu.cn.

Xiangchun Li, Email: lixiangchun@tmu.edu.cn.

Supplemental information

The table includes detailed information on the dataset, such as RBP targets, cell lines and replication data, providing a comprehensive summary of the data utilized in model development.

(A–F) represent 5-10mer motif signatures, respectively

(A–F), Mutations with increased (A, C, E) and decreased (B, D, F) effects from ClinVar, 1000 Genomes Project, and TCGA, respectively.

(A–C) represent the binding results for PRPF8 with ALDH3A2, PRPF8 with GPC3, and U2AF2 with APTX, respectively.

References

- 1.Van Nostrand E.L., Freese P., Pratt G.A., Wang X., Wei X., Xiao R., Blue S.M., Chen J.-Y., Cody N.A.L., Dominguez D., et al. A large-scale binding and functional map of human RNA-binding proteins. Nature. 2020;583:711–719. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-2077-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Montes M., Sanford B.L., Comiskey D.F., Chandler D.S. RNA Splicing and Disease: Animal Models to Therapies. Trends Genet. 2019;35:68–87. doi: 10.1016/j.tig.2018.10.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sade-Feldman M., Yizhak K., Bjorgaard S.L., Ray J.P., de Boer C.G., Jenkins R.W., Lieb D.J., Chen J.H., Frederick D.T., Barzily-Rokni M., et al. Defining T Cell States Associated with Response to Checkpoint Immunotherapy in Melanoma. Cell. 2018;175:998–1013.e20. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2018.10.038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ferlini A., Goyenvalle A., Muntoni F. RNA-targeted drugs for neuromuscular diseases. Science. 2021;371:29–31. doi: 10.1126/science.aba4515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shuai S., Suzuki H., Diaz-Navarro A., Nadeu F., Kumar S.A., Gutierrez-Fernandez A., Delgado J., Pinyol M., López-Otín C., Puente X.S., et al. The U1 spliceosomal RNA is recurrently mutated in multiple cancers. Nature. 2019;574:712–716. doi: 10.1038/s41586-019-1651-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Alipanahi B., Delong A., Weirauch M.T., Frey B.J. Predicting the sequence specificities of DNA- and RNA-binding proteins by deep learning. Nat. Biotechnol. 2015;33:831–838. doi: 10.1038/nbt.3300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Uhl M., Tran V.D., Heyl F., Backofen R. RNAProt: an efficient and feature-rich RNA binding protein binding site predictor. GigaScience. 2021;10 doi: 10.1093/gigascience/giab054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zhu H., Yang Y., Wang Y., Wang F., Huang Y., Chang Y., Wong K.C., Li X. Dynamic characterization and interpretation for protein-RNA interactions across diverse cellular conditions using HDRNet. Nat. Commun. 2023;14:6824. doi: 10.1038/s41467-023-42547-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sun L., Xu K., Huang W., Yang Y.T., Li P., Tang L., Xiong T., Zhang Q.C. Predicting dynamic cellular protein–RNA interactions by deep learning using in vivo RNA structures. Cell Res. 2021;31:495–516. doi: 10.1038/s41422-021-00476-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Taliaferro J.M., Lambert N.J., Sudmant P.H., Dominguez D., Merkin J.J., Alexis M.S., Bazile C., Burge C.B. RNA Sequence Context Effects Measured In Vitro Predict In Vivo Protein Binding and Regulation. Mol. Cell. 2016;64:294–306. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2016.08.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Vaswani A., Shazeer N., Parmar N., Uszkoreit J., Jones L., Gomez A.N., Kaiser L., Polosukhin I. Attention Is All You Need. arXiv. 2017 doi: 10.48550/arXiv.1706.03762. Preprint at. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Grønning A.G.B., Doktor T.K., Larsen S.J., Petersen U.S.S., Holm L.L., Bruun G.H., Hansen M.B., Hartung A.-M., Baumbach J., Andresen B.S. DeepCLIP: predicting the effect of mutations on protein–RNA binding with deep learning. Nucleic Acids Res. 2020;48:7099–7118. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkaa530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Avsec Ž., Agarwal V., Visentin D., Ledsam J.R., Grabska-Barwinska A., Taylor K.R., Assael Y., Jumper J., Kohli P., Kelley D.R. Effective gene expression prediction from sequence by integrating long-range interactions. Nat. Methods. 2021;18:1196–1203. doi: 10.1038/s41592-021-01252-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Montpetit B., Thomsen N.D., Helmke K.J., Seeliger M.A., Berger J.M., Weis K. A conserved mechanism of DEAD-box ATPase activation by nucleoporins and InsP6 in mRNA export. Nature. 2011;472:238–242. doi: 10.1038/nature09862. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ray D., Kazan H., Cook K.B., Weirauch M.T., Najafabadi H.S., Li X., Gueroussov S., Albu M., Zheng H., Yang A., et al. A compendium of RNA-binding motifs for decoding gene regulation. Nature. 2013;499:172–177. doi: 10.1038/nature12311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tsui S., Dai T., Roettger S., Schempp W., Salido E.C., Yen P.H. Identification of Two Novel Proteins That Interact with Germ-Cell-Specific RNA-Binding Proteins DAZ and DAZL1. Genomics. 2000;65:266–273. doi: 10.1006/geno.2000.6169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Schmidt M.N., Mørup M. 2006. Nonnegative Matrix Factor 2-D Deconvolution for Blind Single Channel Source Separation; pp. 700–707. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gerber A.P., Herschlag D., Brown P.O. Extensive Association of Functionally and Cytotopically Related mRNAs with Puf Family RNA-Binding Proteins in Yeast. PLoS Biol. 2004;2 doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0020079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Landrum M.J., Lee J.M., Benson M., Brown G.R., Chao C., Chitipiralla S., Gu B., Hart J., Hoffman D., Jang W., et al. ClinVar: improving access to variant interpretations and supporting evidence. Nucleic Acids Res. 2018;46:D1062–D1067. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkx1153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Auton A., Abecasis G.R., Altshuler D.M., Durbin R.M., Abecasis G.R., Bentley D.R., Chakravarti A., Clark A.G., Donnelly P., Eichler E.E., et al. A global reference for human genetic variation. Nature. 2015;526:68–74. doi: 10.1038/nature15393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cochran R.L., Cidado J., Kim M., Zabransky D.J., Croessmann S., Chu D., Wong H.Y., Beaver J.A., Cravero K., Erlanger B., et al. Functional isogenic modeling of BRCA1 alleles reveals distinct carrier phenotypes. Oncotarget. 2015;6:25240–25251. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.4595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wilson B.N., John A.M., Handler M.Z., Schwartz R.A. Neurofibromatosis type 1: New developments in genetics and treatment. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 2021;84:1667–1676. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2020.07.105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Baralle D., Baralle M. Splicing in action: assessing disease causing sequence changes. J. Med. Genet. 2005;42:737–748. doi: 10.1136/jmg.2004.029538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Adzhubei I., Jordan D.M., Sunyaev S.R. Predicting Functional Effect of Human Missense Mutations Using PolyPhen-2. Curr. Protoc. Hum. Genet. 2013;76 doi: 10.1002/0471142905.hg0720s76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ng P.C., Henikoff S. SIFT: predicting amino acid changes that affect protein function. Nucleic Acids Res. 2003;31:3812–3814. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkg509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Takada D., Emi M., Ezura Y., Nobe Y., Kawamura K., Iino Y., Katayama Y., Xin Y., Wu L.L., Larringa-Shum S., et al. Interaction between the LDL-receptor gene bearing a novel mutation and a variant in the apolipoprotein A-II promoter: molecular study in a 1135-member familial hypercholesterolemia kindred. J. Hum. Genet. 2002;47:656–664. doi: 10.1007/s100380200101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mozas P., Castillo S., Tejedor D., Reyes G., Alonso R., Franco M., Saenz P., Fuentes F., Almagro F., Mata P., Pocoví M. Molecular characterization of familial hypercholesterolemia in Spain: Identification of 39 novel and 77 recurrent mutations in LDLR. Hum. Mutat. 2004;24:187. doi: 10.1002/humu.9264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lee J.M., Nobumori C., Tu Y., Choi C., Yang S.H., Jung H.-J., Vickers T.A., Rigo F., Bennett C.F., Young S.G., Fong L.G. Modulation of LMNA splicing as a strategy to treat prelamin A diseases. J. Clin. Invest. 2016;126:1592–1602. doi: 10.1172/JCI85908. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zhang C., Lee K.-Y., Swanson M.S., Darnell R.B. Prediction of clustered RNA-binding protein motif sites in the mammalian genome. Nucleic Acids Res. 2013;41:6793–6807. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkt421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.GRAINGER R.J., BEGGS J.D. Prp8 protein: At the heart of the spliceosome. RNA. 2005;11:533–557. doi: 10.1261/rna.2220705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kraus C., Braun-Quentin C., Ballhausen W.G., Pfeiffer R.A. RNA-based mutation screening in German families with Sjögren-Larsson syndrome. Eur. J. Hum. Genet. 2000;8:299–306. doi: 10.1038/sj.ejhg.5200453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sutandy F.X.R., Ebersberger S., Huang L., Busch A., Bach M., Kang H.-S., Fallmann J., Maticzka D., Backofen R., Stadler P.F., et al. In vitro iCLIP-based modeling uncovers how the splicing factor U2AF2 relies on regulation by cofactors. Genome Res. 2018;28:699–713. doi: 10.1101/gr.229757.117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Van Nostrand E.L., Pratt G.A., Shishkin A.A., Gelboin-Burkhart C., Fang M.Y., Sundararaman B., Blue S.M., Nguyen T.B., Surka C., Elkins K., et al. Robust transcriptome-wide discovery of RNA-binding protein binding sites with enhanced CLIP (eCLIP) Nat. Methods. 2016;13:508–514. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.3810. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.ENCODE Project Consortium An integrated encyclopedia of DNA elements in the human genome. Nature. 2012;489:57–74. doi: 10.1038/nature11247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Devlin J., Chang M.-W., Lee K., Toutanova K. BERT: Pre-training of Deep Bidirectional Transformers for Language Understanding. arXiv. 2018 doi: 10.48550/arXiv.1810.04805. Preprint at. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Shaw P., Uszkoreit J., Vaswani A. Self-Attention with Relative Position Representations. arXiv. 2018 doi: 10.48550/arXiv.1803.02155. Preprint at. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ji Y., Zhou Z., Liu H., Davuluri R.V. DNABERT: pre-trained Bidirectional Encoder Representations from Transformers model for DNA-language in genome. Bioinformatics. 2021;37:2112–2120. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btab083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Li M., Zhang T., Chen Y., Smola A.J. Proceedings of the 20th ACM SIGKDD international conference on Knowledge discovery and data mining (ACM) 2014. Efficient mini-batch training for stochastic optimization; pp. 661–670. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Dunn S.D., Wahl L.M., Gloor G.B. Mutual information without the influence of phylogeny or entropy dramatically improves residue contact prediction. Bioinformatics. 2008;24:333–340. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btm604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bailey T.L., Johnson J., Grant C.E., Noble W.S. The MEME Suite. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015;43:W39–W49. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkv416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Giudice G., Sánchez-Cabo F., Torroja C., Lara-Pezzi E. ATtRACT—a database of RNA-binding proteins and associated motifs. Database. 2016;2016 doi: 10.1093/database/baw035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Smialek M.J., Ilaslan E., Sajek M.P., Jaruzelska J. Role of PUM RNA-Binding Proteins in Cancer. Cancers. 2021;13:129. doi: 10.3390/cancers13010129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zhang A., Liu W.-F., Yan Y.-B. Role of the RRM domain in the activity, structure and stability of poly(A)-specific ribonuclease. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 2007;461:255–262. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2007.02.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Olejniczak M., Jiang X., Basczok M.M., Storz G. KH domain proteins: Another family of bacterial RNA matchmakers? Mol. Microbiol. 2022;117:10–19. doi: 10.1111/mmi.14842. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Larsen N.A. The SF3b Complex is an Integral Component of the Spliceosome and Targeted by Natural Product-Based Inhibitors. Subcell. Biochem. 2021;96:409–432. doi: 10.1007/978-3-030-58971-4_12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Rino J., Desterro J.M.P., Pacheco T.R., Gadella T.W.J., Carmo-Fonseca M. Splicing Factors SF1 and U2AF Associate in Extraspliceosomal Complexes. Mol. Cell Biol. 2008;28:3045–3057. doi: 10.1128/MCB.02015-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Lewis C.J.T., Pan T., Kalsotra A. RNA modifications and structures cooperate to guide RNA–protein interactions. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2017;18:202–210. doi: 10.1038/nrm.2016.163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Naganuma T., Nakagawa S., Tanigawa A., Sasaki Y.F., Goshima N., Hirose T. Alternative 3′-end processing of long noncoding RNA initiates construction of nuclear paraspeckles. EMBO J. 2012;31:4020–4034. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2012.251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Frankish A., Diekhans M., Ferreira A.-M., Johnson R., Jungreis I., Loveland J., Mudge J.M., Sisu C., Wright J., Armstrong J., et al. GENCODE reference annotation for the human and mouse genomes. Nucleic Acids Res. 2019;47:D766–D773. doi: 10.1093/nar/gky955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Shen X. Code for the article “Deep learning model for characterizing protein-RNA interactions from sequence at single-base resolution. Zenodo. 2024 doi: 10.5281/zenodo.14027315. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

The table includes detailed information on the dataset, such as RBP targets, cell lines and replication data, providing a comprehensive summary of the data utilized in model development.

(A–F) represent 5-10mer motif signatures, respectively

(A–F), Mutations with increased (A, C, E) and decreased (B, D, F) effects from ClinVar, 1000 Genomes Project, and TCGA, respectively.

(A–C) represent the binding results for PRPF8 with ALDH3A2, PRPF8 with GPC3, and U2AF2 with APTX, respectively.

Data Availability Statement

-

•

Our source code is available at GitHub (https://github.com/xilinshen/Reformer) and has been archived at Zenodo.50 A web server of Reformer is available at https://huggingface.co/spaces/XLS/Reformer.

-

•

The eCLIP-seq experiments used in this article are available at the ENCODE repository (https://www.encodeproject.org/). The motifs of RBPs are available at the ATtRACT database (http://attract.cnic.es). Disease-related variants are available at the ClinVar database (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/clinvar/),19 the 1000 Genomes Project (https://www.internationalgenome.org/),20 and TCGA repository (https://portal.gdc.cancer.gov/).