Abstract

A 66-year-old female, with a history of middle aortic syndrome, who had been treated with aorto-iliac bypass, presented 47 years later with a pseudoaneurysm at the distal anastomosis. She was treated with parallel grafting and preservation of a large lumbar artery via periscope approach. This case highlights the challenges and considerations in managing aortic anastomotic pseudoaneurysms, particularly in patients with complex surgical histories with extra-anatomic debranching bypasses.

Keywords: Aortic pseudoaneurysm, Lumbar artery preservation, Middle aortic syndrome, Parallel grafting, Periscope

Congenital middle aortic syndrome (MAS) is characterized by a segmental narrowing of the aorta, often leading to renovascular hypertension, claudication, and under-development of spinal arteries.1 Open aortic reconstruction or bypass is the mainstay of treatment for MAS, but it carries a risk of late complications, including anastomotic pseudoaneurysms.2, 3, 4 Although rare, aortic pseudoaneurysms can be challenging to manage due to the involvement of multiple vascular territories and the potential for rupture if left untreated. Endovascular repair offers a less invasive alternative to open surgery, especially in patients with prohibitive anatomical risk factors. The patient in this report consented to the publication of the manuscript.

Case report

Patient history

A 66-year-old female with hypertension, hypothyroidism, obstructive sleep apnea, and congenital MAS presented with a pseudoaneurysm at the distal anastomosis of her prior aorto-iliac bypass (1976). On physical examination, she was found to have a pulsatile abdominal mass in the left lower quadrant with palpable pedal pulses bilaterally. At the age of 6, prior to the advent of computed tomography imaging, she had undergone a left exploratory thoracotomy for a presumed thoracic aortic coarctation; however, no coarctation was found. Subsequent angiography revealed long segment abdominal aortic atresia consistent with MAS. She continued to have worsening renovascular hypertension and claudication. At the age of 19, she underwent an end-to-side bypass from the supraceliac aorta to the left common iliac artery (CIA), with a jump graft to the celiac artery, and retrograde bypasses to the bilateral renal arteries from the right CIA using great saphenous vein.

In 2009, she was found to have a 4.5 × 4 cm pseudoaneurysm at the distal anastomosis of her aortic bypass graft. She was told there were no operative options and was monitored over time, and eventually lost to follow-up until 2022, at which point the pseudoaneurysm had enlarged to 6.2 cm. The patient sought second opinions from several other cardiovascular surgeons until she was referred to our practice in 2023, when the pseudoaneurysm had enlarged to 7.4 cm. On imaging, she was also noted to have a dominant 8-mm lumbar artery presumably perfusing the spinal cord with no other spinal artery communications in the atretic portion of the aorta (Fig 1, A-C). Open repair would have been challenging given the complexity of a redo-operative field, her morbid obesity (body mass index, 41 kg/m2), the need to preserve a large lumbar artery perfusing a substantial portion of the spinal cord, and the risk of renal injury with clamp placement proximal to the renal artery bypasses. The patient was offered an endovascular approach involving parallel grafting to preserve the dominant 8-mm lumbar artery near the aortic bifurcation. To facilitate operative planning for this pseudoaneurysm with complex morphology, we printed a three-dimensial anatomical model (Fig 1, D and E).

Fig 1.

(A) Axial, (B) coronal, and (C) three-dimensional views of pseudoaneurysm arising from the distal anastomosis of aortic graft to proximal left common iliac artery. (D) Three-dimensional printed anatomical model for operative planning using J735 polyjet printer (Stratasys). (E) Preoperative rendition of native anatomy and measurements.

Intraoperative details

The procedure was performed using bilateral percutaneous femoral access. After selective catheterization of the lumbar artery with a vertebral catheter, it was confirmed that a significant portion of the spinal cord was perfused via this single artery (Fig 2, A-D). This artery was pre-wired with an 0.018” Steelcore (Abbot). Dryseal sheaths, 18 and 12 Fr (W.L. Gore), were placed in the left and right femoral accesses, respectively. After initial angiogram, the Cydar fusion imaging overlay system was utilized (Cydar Medical). Then a 20 mm × 12 mm × 12 cm Excluder Active Control Endograft (W.L. Gore) was advanced from the left femoral access to the mid portion of the prior bypass graft and deployed. The gate appeared pinched and was pre-dilated with a 10-mm balloon. The lumbar pre-wire was exchanged for a Rosen wire, and a 7 Fr Ansel sheath (Cook Medical) was advanced into the lumbar artery. The proximal portion of the Excluder graft was post-dilated with a molding balloon (Fig 2, E), and the ipsilateral limb and gate were dilated in a kissing fashion with two 10-mm balloons to ensure adequate and equal opening of the limbs (Fig 2, F). A periscope graft was deployed in the lumbar artery with a 6 mm × 75 mm Viabahn (W.L. Gore). Inferior branches originating from the distal aspect of the lumbar artery had to be sacrificed to ensure adequate seal. This was then distally extended with 6 × 79 mm VBX (W.L. Gore) to the area of overlap with the ipsilateral limb. A 16 × 120 mm Gore contralateral limb was deployed to the right CIA, ensuring that the distal end of the graft deployed just proximal to the origin of the renal artery bypass. The VBX was then crushed by dilation of the ipsilateral limb with a molding balloon and re-expanded with a 4 × 80 mm balloon (Fig 2, G) to create an “eye of the tiger” configuration of the parallel graft, thus minimizing the gutter space with the left iliac limb.5 When using parallel endografts, the region of poor apposition naturally assumes a broad crescent or “eye” shape, reflecting the geometry of the overlapping grafts. In this technique, the balloon-expandable stent is deliberately dilated using a smaller balloon to achieve a crescent shape, ensuring optimal conformance and full apposition. Using a larger or same-size balloon preserves the stent’s circular shape, which increases the risk of significant gutter leaks. Completion angiogram showed full exclusion of the pseudoaneurysm, successful preservation of lumbar artery perfusion, and no evidence of type I or III endoleak (Fig 2, H). The patient was awakened from anesthesia in the operating room, with no evidence of spinal cord ischemia (SCI) observed prior to transfer. According to our institutional protocol, if signs of SCI were detected during the examination, a lumbar drain would have been promptly placed by the cardiac anesthesiology team in the operating room. In such cases, the patient would be admitted to the cardiovascular intensive care unit and managed with vasoactive support to maintain elevated mean arterial pressure, supplemented with oxygen therapy, and with a hemoglobin target of greater than 10 g/dL.

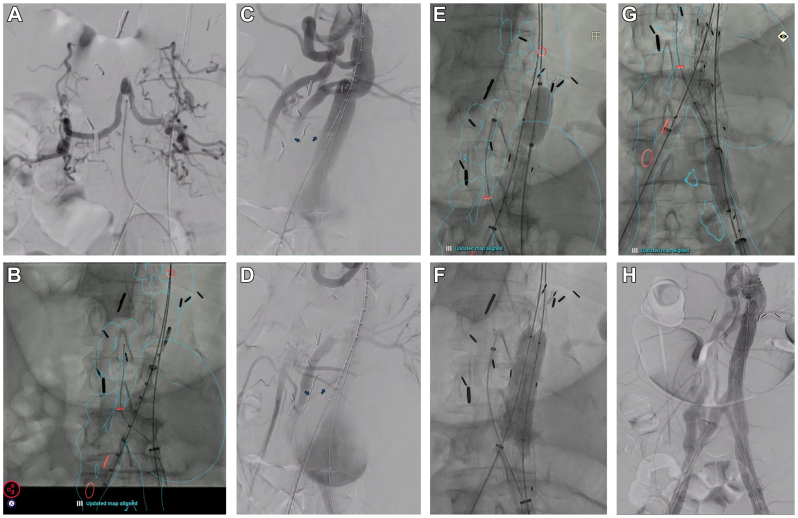

Fig 2.

(A) Selective angiogram of the lumbar artery demonstrating a large-caliber vessel perfusing a significant portion of the spinal cord. (B) Cydar imaging fusion overlay; the red circles, cranially to caudally, mark the origins of celiac artery jump graft, lumbar artery, vein graft bypasses to bilateral renal arteries and right hypogastric. (C and D) Preintervention angiogram. The blue arrows point to pre-wired lumbar artery. (E) Ballooning the proximal seal and (F) and kissing post-dilation with 10 mm × 60 mm balloons. (G) Balloon molding of ipsilateral limb and periscope stent in an eye of the tiger fashion. This involved crushing the VBX by with overdilation the ipsilateral limb with a molding and occlusion balloon and then re-expanding the VBX with a 4 × 80 mm balloon. (H) Completion angiogram showed exclusion of the pseudoaneurysm, patent lumbar periscope stent, and patent supraceliac and renal artery bypasses.

Postoperative course

The patient did not have any neurologic deficits and was discharged home on postoperative day 1 on daily low-dose aspirin. Follow-up imaging at 1 month showed a small gutter endoleak without sac expansion. At 6 months, computed tomography angiography showed resolution of gutter endoleak and confirmed a thrombosed pseudoaneurysm (Fig 3, A and B). A 12-month ultrasound showed a thrombosed pseudoaneurysm measuring 6.4 × 6.4 cm (Fig 3, C). Because there was no endoleak or sac enlargement during the first year, duplex ultrasound at 12-month intervals will be performed. Non-contrast computed tomography scanning of the entire aorta at 5-year intervals will be performed to detect structural abnormalities in the endovascular repair or aneurysmal changes in other aortic segments.

Fig 3.

(A and B) Six-month follow-up imaging showed thrombosed pseudoaneurysm, minimal type 2 endoleak from inferior lumbar branches. (C) Twelve-month follow-up ultrasound showed thrombosed pseudoaneurysm measuring 6.4 × 6.4 cm.

Discussion

Pseudoaneurysm involving a prior aortic bypass graft in the setting of an atretic aorta with atypical spinal perfusion presents a unique operative challenge.3,6,7 Open surgical repair in this patient was associated with unique challenges and risks, given the redo-operative field, morbid obesity, need for clamping of the aorta in the setting of her retrograde iliac to renal artery bypass, and the need for reconstructing her dominant lumbar artery originating just distal to the aortic bifurcation to minimize the risk of SCI. In a comprehensive analysis of patients with chronic aortic pseudoaneurysms, a review of 50 cases demonstrated that these pseudoaneurysms can be effectively treated using a percutaneous plug or occluder approach. This method offers a reasonable expectation of initial success, along with acceptable short- and long-term morbidity and mortality rates.8 However, in our patient, this approach was not feasible due to the presence of a large lumbar artery supplying most of the spinal cord. We opted to revascularize her lumbar artery using a parallel grafting technique. Given the proximity of the origin of the lumbar artery to the aortic bifurcation, we were able to access the artery from the left femoral artery and extend the graft parallel to the left iliac limb, which allowed us to obtain a long overlap and minimize the chances of a gutter leak.

Parallel grafting has been shown to be a safe, efficacious, and off-the-shelf alternative to conventional repair of complex aortic aneurysms, particularly in urgent cases.9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15 This approach is not always an anatomic-best option and may carry the risk of inadequate seal or exclusion with gutter endoleak. Prior experience has demonstrated that in appropriately selected patients, few require reintervention related to gutter endoleaks. Additionally, the presence of such endoleaks does not correlate to increased risk for aneurysm sac growth.16 In fact, gutter-related type Ia endoleaks resolve spontaneously in the majority of cases during early to midterm follow-up, as it did in this patient.16 Although no meta-analysis specifically addresses chimney and snorkel repair for isolated pseudoaneurysms, a recent systematic review and meta-analysis evaluating fenestrated and chimney/snorkel techniques for the endovascular repair of juxtarenal aortic aneurysms revealed both approaches had favorable safety profiles; however, fenestrated approach showed a reduced incidence of type I endoleaks.17 In this case, a fenestrated approach would have necessitated either in-situ laser fenestration or back-table physician modification of the endograft. However, these options were not feasible with the smallest available bifurcated endograft, the conformable Excluder, which is constructed from polytetrafluoroethylene. Careful preoperative planning and the use of advanced imaging techniques, such as fusion overlay, were critical in achieving a successful outcome in this patient.

Conclusion

This case highlights the usefulness of the parallel endograft technique for preserving essential vascular branches during complex endovascular aortic intervention.

Funding

Research support paid directly to Stanford University from W.L. Gore, Medtronic, Cook Medical, Endospan, Terumo, Abbot, Shockwave, and Penumbra.

Disclosures

None.

From the Society for Clinical Vascular Surgery

Footnotes

The editors and reviewers of this article have no relevant financial relationships to disclose per the Journal policy that requires reviewers to decline review of any manuscript for which they may have a conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Cortenbach K.R.G., Yosofi B., Rodwell L., et al. Editor’s choice – therapeutic options and outcomes in midaortic syndrome: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2023;65:120–130. doi: 10.1016/j.ejvs.2022.10.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Musajee M., Gasparini M., Stewart D.J., Karunanithy N., Sinha M.D., Sallam M. Middle aortic syndrome in children and adolescents. Glob Cardiol Sci Pract. 2022;2022 doi: 10.21542/gcsp.2022.20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chaudhary R., Tiwari T., Sharma R., Goyal S. Midaortic syndrome in a middle-age female. BMJ Case Rep. 2021;14 doi: 10.1136/bcr-2021-246530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lazea C., Al-Khzouz C., Sufana C., et al. Diagnosis and management of genetic causes of middle aortic syndrome in children: a comprehensive literature review. Ther Clin Risk Manag. 2022;18:233–248. doi: 10.2147/TCRM.S348366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Minion D. Molded parallel endografts for branch vessel preservation during endovascular aneurysm repair in challenging anatomy. Int J Angiol. 2012;21:081–084. doi: 10.1055/s-0032-1315624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hashizume K., Shimizu H., Koizumi K., Inoue S. Endovascular aneurysm repair using the periscope graft technique for thoracic aortic anastomotic pseudoaneurysm. Interact Cardiovasc Thorac Surg. 2013;16:553–555. doi: 10.1093/icvts/ivs519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Luu H.Y., Pulcrano M.E., Hua H.T. Surgical management of middle aortic syndrome in an adult. J Vasc Surg Cases Innov Tech. 2020;6:38–40. doi: 10.1016/j.jvscit.2019.10.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lewis B.E., Bufalino D.V., Hussein M.H., et al. Percutaneous repair of chronic aortic pseudoaneurysm: a single-center experience. J Soc Cardiovasc Angiogr Interv. 2024;3 doi: 10.1016/j.jscai.2024.102249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lepidi S., Piazza M., Scrivere P., et al. Parallel endografts in the treatment of distal aortic and common iliac aneurysms. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2014;48:29–37. doi: 10.1016/j.ejvs.2014.03.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lobato A.C. Sandwich technique for aortoiliac aneurysms extending to the internal iliac artery or isolated common/internal iliac artery aneurysms: a new endovascular approach to preserve pelvic circulation. J Endovasc Ther. 2011;18:106–111. doi: 10.1583/10-3320.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Alfawaz A.A., Dunphy K.M., Abramowitz S.D., et al. Parallel grafting should be considered as a viable alternative to open repair in high-risk patients with paravisceral aortic aneurysms. Ann Vasc Surg. 2021;74:237–245. doi: 10.1016/j.avsg.2020.12.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Donas K.P., Telve D., Torsello G., Pitoulias G., Schwindt A., Austermann M. Use of parallel grafts to save failed prior endovascular aortic aneurysm repair and type Ia endoleaks. J Vasc Surg. 2015;62:578–584. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2015.04.395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Azevedo Mendes D., Machado R., Pereira C., Castro J., Almeida R. Parallel grafting technique for a complex zone 6 aortic pseudoaneurysm treatment. Angiol Cir Vasc. 2023;19:42–45. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Donas K.P., Lee J.T., Lachat M., Torsello G., Veith F.J., on behalf of the PERICLES investigators Collected World experience about the performance of the snorkel/chimney endovascular technique in the treatment of complex aortic pathologies: the PERICLES registry. Ann Surg. 2015;262:546–553. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000001405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Castro-Ferreira R., Dias P.G., Sampaio S.M., Teixeira J.F., Lobato A.C. Parallel graft technique in a complex aortic aneurysm: the value of intra-operative flexibility from the original operative plan. EJVES Short Rep. 2019;43:37–40. doi: 10.1016/j.ejvssr.2019.03.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ullery B.W., Tran K., Itoga N.K., Dalman R.L., Lee J.T. Natural history of gutter-related type Ia endoleaks after snorkel/chimney endovascular aneurysm repair. J Vasc Surg. 2017;65:981–990. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2016.10.085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Baldeh T., Reilly T., Mansoor T., et al. Systematic review and meta-analysis of fenestrated and chimney/snorkel techniques for endovascular repair of juxtarenal aortic aneurysms. J Endovasc Ther. 2024;32 doi: 10.1177/15266028241231171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]