Abstract

Introduction

Radiofrequency ablation is a treatment for facetogenic low back pain that targets medial branches of lumbar dorsal rami to denervate facet joints. Clinical outcomes vary; optimizing cannula placement to better capture the medial branch could improve clinical outcomes. A novel parasagittal technique was proposed from an anatomic model; this technique was proposed to optimize capture of the medial branch. The anatomic feasibility of the novel technique has not been evaluated.

Objective

To simulate and evaluate the proposed parasagittal technique in its ability to achieve proper cannula placement and proximity of uninsulated cannula tips to the medial branches of the dorsal rami in cadaveric specimens.

Methods

Under fluoroscopic guidance, the parasagittal technique was used to place 14 cannulae targeting the lumbar medial branches of 2 cadavers. Meticulous dissection was undertaken to assess cannula alignment and measure proximities to target nerves with a digital caliper.

Results

The novel parasagittal technique was successfully performed in a cadaveric model in 12 of 14 attempts. The technique achieved close proximity of cannula tips to medial branches (0.8 ± 1.1 mm). In 2 instances, cannulae were placed unsuccessfully; in one instance, the cannula was too far anterior, and in the other, it was too far retracted.

Conclusion

In this cadaveric simulation study, the feasibility of performing the parasagittal technique for lumbar radiofrequency ablation was evaluated. This study suggests that the parasagittal technique is a feasible option for lumbar medial branch radiofrequency ablation.

Keywords: low back pain, back pain, nerve ablation, denervation, radiofrequency ablation, facet joints, lumbar medial branch, cannula angles

Introduction

Treatment expenditures, lost wages, and decreased worker productivity due to chronic low back pain costs the United States approximately $100 billion annually.1 Facetogenic low back pain has an estimated prevalence that ranges between 16% and 89%, contributing substantially to this economic burden.2–5

Radiofrequency ablation (RFA) is a common treatment for facetogenic low back pain and involves ablating the medial branches of the lumbar dorsal rami. It is postulated that the extent of the medial branch that is coagulated (ie, length and thickness of the nerve) correlates with the duration of pain relief after RFA.6 A previous animal study reported in a rat sciatic nerve ablation model that extended length of nerve damage was associated with prolonged loss of nerve function.7 Because of the ovoid morphology of the lesion produced by conventional RFA electrodes, parallel placement of the cannula tip along the medial branch at the superior articular process (SAP) is recommended to adequately coagulate the nerve and prolong the duration of pain relief.8–10 Clinical outcomes with regard to duration and degree of pain relief, however, are variable.11–14 One potential reason for this variability in clinical outcomes is that traditional approaches for cannula placement might not be optimized to adequately achieve parallel needle placement and coagulation of the medial branch.

Although previous anatomic studies recommended placing a cannula at the middle 2 quarters of the lateral neck of the SAP at a 15° to 20° angle lateral to the parasagittal plane (on an anteroposterior view) with a 35° to 40° cranial-to-caudal angulation (on a lateral view),8,15 a more recent anatomic study has demonstrated that these parameters are likely insufficient to achieve parallel placement along the medial branch.16 A technique that targets the posterior portion of the lateral neck of the SAP, and emphasizes minimal to no angulation from the parasagittal plane with a steeper cranial-to-caudal angulation, was proposed16,17 on the basis of anatomic dissection as an RFA technique that would optimize parallel needle placement and coagulation of the medial branch (the parasagittal technique). Although this technique was developed on the basis of the position of the medial branch and surrounding anatomic structures on cadaveric dissection, the feasibility of performing this procedure has not been evaluated—specifically, the ability of an RFA cannula to be placed directly along the medial branch with the parasagittal technique. Therefore, the objective of the present pilot study was to evaluate the ability of the proposed parasagittal RFA technique, when performed in a cadaveric specimen, to achieve optimal parallel placement of the cannula along the medial branches of the lumbar dorsal rami.

Methods

Cannula placement protocol

Two formalin-embalmed cadaveric torsos were procured from Western University’s body bequeathal program (REB# 122089). Under fluoroscopic guidance, 14 cannulae were placed in the specimens, targeting the medial branches of lumbar spinal nerves. Cannulae placed were used as a proxy for any and all electrodes. Cannulae were placed with the previously proposed parasagittal technique,16,17 involving a parasagittal cannula trajectory and increased cranial-to-caudal angulation to target the posterior half of the lateral neck of the SAP (Figure 1A and B). Cannula placement was performed by the senior author, who is a spine pain interventionalist with more than 13 years of experience in lumbar RFA procedures. Placements were confirmed by an anatomist with a decade of experience in this field. The procedure was completed in the facilities of the Canadian Surgical Technologies & Advanced Robotics (CSTAR) lab located in University Hospital, London, Ontario, Canada, with the assistance of a medical radiology technician.

Figure 1.

Osteological and cadaveric images with overlayed schematics representing parasagittal technique and measurement methodology. (A/B) Lateral (A) and superior (B) views of parasagittal technique demonstrating cannula (dark green line) trajectory. (C) Cadaveric image with superimposed schematics of digital caliper measurement methodology. Measurements of nerve–cannula distance (X and light green line) were taken perpendicular to the cannula, 5 mm from the distal tip. 1 = mammillary process of superior articular process; 2 = transverse process; AQ = anterior quarter; PQ = posterior quarter; Ib= intermediate branch; Lb = lateral branch; Mb = medial branch; Ant = anterior; Post = posterior; Inf = inferior; Sup = superior.

After cannula placement at each vertebral level, fluoroscopic images (anteroposterior, 30° oblique, and lateral) were captured and saved for records. Cannulae were glued at their entry to the skin after placement to prevent movement during dissection.

Dissection protocol

Meticulous dissection of tissue surrounding the cannula tips was undertaken to expose the targeted medial branches. A dorsolateral approach was used to remove the skin and underlying fascia of the back to expose the latissimus dorsi muscles. This musculature was removed to reveal the thoracolumbar fascia and serratus posterior inferior muscles. Further removal of these structures revealed the erector spinae muscle group, including the iliocostalis, longissimus, and spinalis muscles and their aponeurosis. The erector spinae group was dissected sequentially, and care was taken to preserve the position of the cannulae. This approach revealed the intertransversarii mediales and laterales muscles, after which portions of these muscles were removed as necessary to reveal medial branches coursing across the lateral necks of the SAPs and the cannula tips. Remaining fascia, adipose tissue, and accompanying blood vessels were removed to reveal the origins of the medial branches. After dissection, NIKON D80 and D3500 cameras were used to take photographic images of all cannula placements in both cadaveric specimens to document cannula position.

Nerve–cannula distance measurement protocol

Portions of the iliac crest and sacrum were carefully removed with an autopsy saw (Mopec BD040) and double-action bone rongeurs (Leur-Stille, SKU# 105-17230) to better visualize structures and provide ease of access for measurements. Measurements of distance between nerves and cannulae were taken from the midpoint of the presumed 10-mm active cannula tip (5 mm from distal tip), as this is the strongest point of the ovoid-shaped heat lesion.18 Rulers were placed along cannulae tips to find the point 5 mm from the tip of each cannula, which was then marked with a surgical pen. A sliding digital caliper (Mastercraft, GS586800) was placed with one jaw aligned at the marked 5-mm point, after which the other jaw was adjusted to align with the middle of each medial branch perpendicular from the marked cannula point (Figure 1C). Digital caliper distance measurements were then recorded in a data chart. Measurements were completed twice with blinding to previous measurements, and the average of each set of 2 measurements was included in the final results.

Data analysis protocol

Qualitative analysis was performed after dissection to assess the parasagittal technique’s ability to achieve parallel alignment with the medial branch. Mean distances of the cannula tip from the medial branches were quantified in Microsoft Excel software. Further analysis was performed by organizing cannula placements into nominal data (ie, yes/no) on the basis of whether the cannula tip was within ∼5 mm of nerve targets. The ∼5-mm distance was based on the predicted lesion radius of a 16-gauge cannula heated to 80° Celsius for 2 minutes or an 18-gauge cannula heated to 90C for 3 minutes, as per the work of Cosman et al.18 In the event that cannula placement was not representative of the parasagittal technique, the cases were excluded from the analysis.

SPSS software (IBM) was used to calculate intra-class correlation coefficients across trials of digital caliper measurements to assess intra-observer reliability. Excel software was used to calculate the mean and standard deviation for distances from cannula tips to medial branches.

Results

Anatomic findings

All 14 dissected medial branches coursed along the lateral neck of the SAP, traveling posterolateral at the anterior half of the SAP and parasagittal at the distal half before diving medially at the mammillo-accessory ligament (MAL). All MALs, although variable in size, bridged the mammillo-accessory notch at the most distal aspect of the SAP. In 2 cases (bilateral L4 in specimen 1), MAL ossification was present. In 5 of 14 cases, the medial branches traveled above the MAL, whereas the remaining 9 medial branches traveled beneath the MAL (Figure 2).

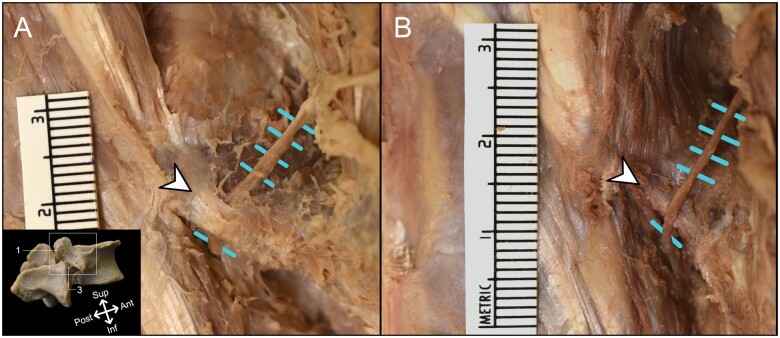

Figure 2.

Cadaveric images of variable medial branch courses. (A) Standard course of lumbar dorsal ramus medial branch (blue hatch marks) traveling beneath the mammillo-accessory ligament (white arrowhead). (B) Anatomic variation observed in 5 dissections of this study, wherein the medial branch travels above the mammillo-accessory ligament. 1 = mammillary process of superior articular process; 3 = accessory process of superior articular process; Ant = anterior; Inf = inferior; Post = posterior; Sup = superior.

Relationship of cannula tips to medial branches

Cannula placements with the parasagittal technique achieved parallel placement with the medial branch in 12 of 14 instances (Figure 3). In 2 of 14 instances, cannulae were not placed appropriately, and therefore all corresponding data were excluded. In the case of specimen 1 placement #4, the final cannula placement was too far retracted, and in the case of specimen 2 placement #3, the cannula was placed too far anteriorly.

Figure 3.

Relationship between cadaveric dissection and fluoroscopic imaging during simulated parasagittal technique RFA procedure. Both image sets 1 (left-sided placement) and 2 (right-sided placement) were taken from the same specimen. (1A/2A) Posterolateral views of osteological structures corresponding to cadaveric image orientation. (1B/2B) Lateral views of cadaveric dissection demonstrating medial branches (blue hatch marks) traveling along lateral necks of superior articular processes (SAPs). (1C/2C) Anteroposterior fluoroscopic views. (1D/2D) Lateral fluoroscopic views. (1E/2E) Oblique (30°) fluoroscopic views. 1= mammillary process of SAP; 3= accessory process of SAP; asterisk= sacral ala; white arrowhead= cannula identification corresponding to images 1B/2B; Ant= anterior; Inf= inferior; Post= posterior; Sup= superior.

There were 2 instances of cannulae piercing the MAL (Figure 4A and B). In one instance, the cannula pierced the medial branch itself (Figure 4C), and in the other instance, the cannula was in direct contact with the medial branch well past 10 mm from the cannula tip. The mean distance between the midpoint of active cannula tips and medial branches of dorsal rami was 0.8 ± 1.1 mm (Table 1). Of the 12 cannulae tips that represented the parasagittal technique, 100% were within 5 mm of the medial branches. The intra-class correlation coefficient between rounds of digital caliper measurements was 0.998 (95% CI: 0.997–0.999).

Figure 4.

Three cadaveric images of cannulae placed with the parasagittal technique. (A) Cannula diving beneath and slightly piercing mammillo-accessory ligament (white arrowheads). (B) Cannula piercing mammillo-accessory ligament. (C) Cannula piercing the medial branch of dorsal ramus (blue hatch marks). 1= mammillary process; 3= accessory process; Ant= anterior; Inf= inferior; Post= posterior; Sup= superior.

Table 1.

Distances from midpoints of active cannula tips to medial branches in mm, as well as frequencies of cannulae being placed within a 5 mm predicted heat lesion radius.

| Needle placement | Distances between medial branches and cannulae, mm | Within 5 mm heat lesion? (yes/no) |

|---|---|---|

| Specimen 1 | ||

| 1 | 0.0 | Yes |

| 2 | 0.0 | Yes |

| 3 | 0.0 | Yes |

| 5 | 2.4 | Yes |

| 6 | 0.0 | Yes |

| 7 | 1.4 | Yes |

| Specimen 2 | ||

| 1 | 1.6 | Yes |

| 2 | 0.0 | Yes |

| 4 | 3.2 | Yes |

| 5 | 0.0 | Yes |

| 6 | 0.0 | Yes |

| 7 | 1.1 | Yes |

| Within 5 mm heat lesion frequency, % | 100 | |

Discussion

Previous literature has postulated that the use of a parasagittal technique is an optimal parallel approach to lumbar medial branch RFA, as it maximizes needle-to-nerve contact and coagulation of the medial branch.16,17 The findings of the present study provide anatomic evidence supporting the feasibility of this procedure. The reported nerve–cannula proximities combined with fluoroscopic and cadaveric images demonstrate the successful placement of cannulae along the medial branches, providing spine pain interventionalists with valuable knowledge to incorporate the technique into their procedural repertoire.

Anatomy of the medial branch

Previous anatomic studies by Bogduk et al.19,20 described the trajectory of medial branches as caudal and dorsal while curving around the lateral neck of the SAP. Medial branches were then found to dive medially at the mammillo-accessory notch bridged by the sometimes ossified MAL, where the articular branches to the facet joints were subsequently found to arise. Lau et al.8 also investigated the anatomy of the medial branches and further emphasized the role of the MAL, stating its potential occlusion of the medial branches at the distal quarter of the neck of the SAP. More recent studies found that the trajectory of the medial branches was posterolateral along the anterior half of the lateral neck of the SAP, before transitioning to a parasagittal trajectory along the posterior half.16,21 Additionally, the present study found that the medial branch coursed under the MAL at the posterior margin of the SAP, not the posterior quarter, such that the MAL would not impede a lesion at the posterior quarter of the SAP. This finding led to the proposal of targeting the medial branch along the posterior half of the lateral neck of the SAP with a parasagittal cannula trajectory.16

In the present study, medial branches consistently traveled along the lateral neck of the SAP in a manner consistent with previous published studies.8,16,19,20 Interestingly, in 5 cases, the medial branch coursed above the MAL, which was not described in the previous literature that was found.8,16,19,20 This could result in a higher capture rate of the medial branches in these situations. The clinical implications of this anatomic variation are unknown but require further investigation.

Parasagittal technique feasibility

Parallel placement of conventional RFA cannula with the medial branch is reported to provide better patient-reported pain relief outcomes for those suffering from facetogenic low back pain.10 It is believed that the parallel alignment of the cannula tip with the medial branch leads to a greater length of the target nerve being coagulated, accounting for better patient outcomes. This assumption is supported by an animal study showing that longer length of nerve damage was associated with prolonged loss of nerve function.7 Conceivably, the parallel placement of the cannula with the nerve would ensure that the longest portion of the prolate spheroid lesions generated by the conventional cannula is aligned along the nerve to coagulate the greatest length possible. Nonparallel or near-parallel placements would not place the longest portion of the lesion parallel with the nerve, thereby reducing the length of nerve coagulated. Therefore, it has been recommended, to achieve parallel placement, that the RFA cannula be inserted at an approximately 20° oblique angulation from the parasagittal plane and a 35° to 40° cranial-to-caudal angulation along the middle 2 quarters of the lateral neck of the SAP.8,15

In more recent studies, targeting the posterior half of the lateral neck of the SAP was proposed on the basis of (1) the geometry of the lateral neck and (2) consideration of the proximity of the intermediate and lateral (IL) branches of the lumbar dorsal ramus to the nerve target.16,21 The proposed parasagittal technique is reported to require a cannula angulation of <10° in the posterior view and a cranial-to-caudal angulation ranging between 40.17° and 64.10° in the lateral view.16,17,22 In the present study, the proposed parasagittal cannula placement technique was performed in cadaveric specimens. The anatomic findings of the present study demonstrated that the fluoroscopy-guided parasagittal technique was successful in placing the cannula tip parallel with and in close proximity (<5 mm) to the medial branches, even piercing the medial branch itself in one instance. Although lesion size can vary on the basis of a number of factors, including gauge, tip length, and duration of the lesion, cannulae placed with the parasagittal technique were in direct contact with the medial branch in this study. Given these results, any gauge of cannula would coagulate the medial branch because of its close proximity.

In 2 instances, cannula placement was unsuccessful and therefore did not accurately represent the parasagittal technique. This was likely due to a misalignment of the fluoroscope’s C-arm that caused a lack of true lateral imaging before cannula placement. As described in previous research by Waring et al.,23 it is paramount to “superimpose the index level’s superior and inferior pedicle margins and align the superior vertebral endplate parallel to the X-ray beam” via the C-arm to consistently and correctly place cannulae for lumbar medial branch RFA.

Importantly, the present study confirms that a more caudal angulation and parasagittal approach can result in placement of the cannula directly along the medial branch. This could improve the efficiency of achieving a successful RFA, as potentially only a single placement would be required to capture a significant portion of the medial branch. Further clinical studies will be required to evaluate the effects of medial branch RFA on pain relief outcomes with the traditional and parasagittal techniques.

Anatomic variability

Although the course of lumbar medial branches is generally consistent in the literature8,16,19,20 (ie, traveling along the lateral neck of the SAP before diving medially beneath the MAL), a degree of individual variation is to be expected. Previous literature reported multiple areas of variation that could influence a medial branch RFA procedure, including the geometric shape of the SAPs,22,26 branching patterns/location of the dorsal ramus into medial branches,8,16,20,21,27 morphology of MALs,28 and lumbar lordosis. Additionally, the present study identified 5 of 14 medial branches traveling superior to the MAL rather than deep. Osteophyte formation and inflammation-mediated joint changes are also common,29,30 which might cause physical restrictions of the cannula and require a unique angulation or technique during lumbar RFA.

As the MAL has considerable variation in anatomy (particularly morphology), a blunt cannula is not necessarily obscured by the MAL when a parasagittal approach is used, even if the cannula does not pierce the MAL. However, using an oblique approach with a blunt cannula might avoid a thicker MAL that obscures the target and that a blunt cannula might not pierce. Therefore, to optimize pain relief outcomes, patient-specific anatomy should be considered in decisions about the use of any technique for lumbar RFA.

Limitations

The present study is limited by the small sample size, which is due to specimen availability and the time-consuming dissections required to complete this work. However, the present feasibility study meets the previously published recommended sample size of 12.31 The present study involved simulation of lumbar RFA, and therefore, further clinical study is required to evaluate effectiveness of the parasagittal technique in providing improved pain relief for patients. Further studies should also evaluate accuracy and efficacy between the parasagittal and conventional techniques.

Conclusions

In this cadaveric simulation study, the feasibility of performing the parasagittal technique for lumbar RFA was evaluated. The parasagittal technique was found to be anatomically feasible in achieving close proximity and parallel placement with the medial branches when performed in a cadaveric specimen. The results of the present study provide spine pain interventionalists with cadaveric and fluoroscopic images to incorporate the parasagittal technique into their procedural repertoire. This study suggests that the parasagittal technique is a feasible option to add to the available techniques for medial branch RFA.

Acknowledgments

The authors first and foremost thank the donors who bequeathed their bodies to Western University’s Human Anatomy Lab. This work would not be possible without their generosity. We also thank Bryn Bhalerao, Sina Chegini, Haley Linklater, and Kevin Walker for contributing their time to assist in this study throughout its iterations.

Contributor Information

Charlotte Jones-Whitehead, Department of Anatomy and Cell Biology, Schulich School of Medicine & Dentistry, Western University, London, Ontario, Canada.

John Tran, Surgery (Division of Anatomy), Temerty Faculty of Medicine, University of Toronto, Toronto, Ontario, Canada; Department of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, Western University, London, Ontario, Canada; Parkwood Institute Research, Lawson Health Research Institute, London, Ontario, Canada.

Timothy D Wilson, Department of Anatomy and Cell Biology, Schulich School of Medicine & Dentistry, Western University, London, Ontario, Canada.

Eldon Loh, Department of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, Western University, London, Ontario, Canada; Parkwood Institute Research, Lawson Health Research Institute, London, Ontario, Canada.

Funding

Partial funding for this study was provided by The Gray Centre for Mobility and Activity Catalyst Grant.

Conflicts of interest: There are no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Ethics approval: This project was approved by Western University’s Human Ethics via Western Research Ethics Manager (WREM), protocol #122089.

References

- 1. Shmagel A, Foley R, Ibrahim H. Epidemiology of chronic low back pain in US adults: National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 2009–2010. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2016;68(11):1688-1694. 10.1002/ACR.22890 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Kalichman L, Li L, Kim DH, et al. Facet joint osteoarthritis and low back pain in the community-based population. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2008;33(23):2560-2565. 10.1097/BRS.0B013E318184EF95 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Falco FJ. An update of the systematic assessment of the diagnostic accuracy of lumbar facet joint nerve blocks. Pain Phys. 2012;15(6):E869-E907. 10.36076/ppj.2012/15/E869 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Ko S, Vaccaro AR, Lee S, Lee J, Chang H. The prevalence of lumbar spine facet joint osteoarthritis and its association with low back pain in selected Korean populations. Clin Orthop Surg. 2014;6(4):385-391. 10.4055/cios.2014.6.4.385 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Cohen SP, Bhaskar A, Bhatia A, et al. Consensus practice guidelines on interventions for lumbar facet joint pain from a multispecialty, international working group. Reg Anesth Pain Med. 2020;45(6):424-467. 10.1136/RAPM-2019-101243 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Bogduk N. Lumbar radiofrequency neurotomy. Clin J Pain. 2006;22(4):409. 10.1097/01.AJP.0000182845.55330.9F [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Zachariah C, Mayeux J, Alas G, et al. Physiological and functional responses of water-cooled versus traditional radiofrequency ablation of peripheral nerves in rats. Reg Anesth Pain Med. 2020;45(10):792-798. 10.1136/rapm-2020-101361 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Lau P, Mercer S, Govind J, Bogduk N. The surgical anatomy of lumbar medial branch neurotomy (facet denervation). Pain Med. 2004;5(3):289-298. 10.1111/j.1526-4637.2004.04042.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Bogduk N, Macintosh J, Marsland A. Technical limitations to the efficacy of radiofrequency neurotomy for spinal pain. Neurosurgery. 1987;20(4):529-535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Loh JT, Nicol AL, Elashoff D, Ferrante FM. Efficacy of needle-placement technique in radiofrequency ablation for treatment of lumbar facet arthropathy. J Pain Res. 2015;8:687-694. 10.2147/JPR.S84913 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Speldewinde GC. Outcomes of percutaneous zygapophysial and sacroiliac joint neurotomy in a community setting. Pain Med. 2011;12(2):209-218. 10.1111/J.1526-4637.2010.01022.X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Schneider BJ, Doan L, Maes MK, Martinez KR, Gonzalez Cota A, Bogduk N; Standards Division of the Spine Intervention Society. Systematic review of the effectiveness of lumbar medial branch thermal radiofrequency neurotomy, stratified for diagnostic methods and procedural technique. Pain Med. 2020;21(6):1122-1141. 10.1093/pm/pnz349 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. MacVicar J, Borowczyk JM, MacVicar AM, Loughnan BM, Bogduk N. Lumbar medial branch radiofrequency neurotomy in New Zealand. Pain Med. 2013;14(5):639-645. 10.1111/pme.12000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Dreyfuss P, Halbrook B, Pauza K, Joshi A, McLarty J, Bogduk N. Efficacy and validity of radiofrequency neurotomy for chronic lumbar zygapophysial joint pain. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2000;25(10):1270-1277. 10.1097/00007632-200005150-00012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Patel AK, Chang JL, Haffey PR, Mainkar O, Gulati A. Characterizing an angle of cannula insertion for lumbar medial branch radiofrequency neurotomy: a retrospective observational study. Interv Pain Med. 2022;1(1):100071. 10.1016/J.INPM.2022.100071 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Tran J, Peng P, Loh E. Anatomical study of the medial branches of the lumbar dorsal rami: implications for image-guided intervention. Reg Anesth Pain Med. 2022;47(8):464-474. 10.1136/RAPM-2022-103653 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Tran J, Loh E. Reply to letter to editor regarding “anatomical study of the medial branches of the lumbar dorsal rami: implications for image guided intervention.” Reg Anesth Pain Med. 2023;48(2):95-96. 10.1136/rapm-2022-104168 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Cosman ER, Dolensky JR, Hoffman RA. Factors that affect radiofrequency heat lesion size. Pain Med. 2014;15(12):2020-2036. 10.1111/pme.12566 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Bogduk N. The innervation of the lumbar spine. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 1983;8(3):286-293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Bogduk N, Wilson AS, Tynan W. The human lumbar dorsal rami. J Anat. 1982;134(2):383-397. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Tran J, Campisi E, Agudelo AR, Agur AM, Loh E. High-fidelity 3D modelling of the lumbar dorsal rami. Interv Pain Med. 2024;3(1):100401-105944. 10.1016/j.inpm.2024.100401 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Tran J, Campisi ES, Agur AMR, Loh E. Quantification of needle angles for traditional lumbar medial branch radiofrequency ablation: an osteological study. Pain Med. 2023;24(5):488-495. 10.1093/PM/PNAC160 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Waring PH, Cohen I, Maus TP, Duszynski B, Furman MB. True lateral imaging during lumbar medial branch radiofrequency neurotomy: interobserver reliability. Interv Pain Med. 2024;3(2):100413. 10.1016/J.INPM.2024.100413 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Bryant DG, Dovgan JT, Hunt C, Beckworth WJ, Waring PH, Rivers WE. Letter to the editor regarding ‘Anatomical study of the medial branches of the lumbar dorsal rami: implications for image-guided intervention.’ Reg Anesth Pain Med. 2023;48(2):94-94. 10.1136/RAPM-2022-104119 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Reddy AT, Goyal N, Cascio M, et al. Abnormal paresthesias associated with radiofrequency ablation of lumbar medial branch nerves: a case report. Cureus. 2023;15(2):e35176. 10.7759/CUREUS.35176 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Tran J, Campisi ES, Agur AMR, Loh E. Quantification of needle angles for lumbar medial branch denervation targeting the posterior half of the superior articular process: an osteological study. Pain Med. 2024;25(1):13-19. 10.1093/PM/PNAD105 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Saito T, Steinke H, Miyaki T, et al. Analysis of the posterior ramus of the lumbar spinal nerve the structure of the posterior ramus of the spinal nerve. Anesthesiology. 2013;118(1):88-94. 10.1097/ALN.0B013E318272F40A [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Bogduk N. The lumbar mamillo-accessory ligament: its anatomical and neurosurgical significance. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 1981;6(2):162-167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Binder DS, Nampiaparampil DE. The provocative lumbar facet joint. Curr Rev Musculoskelet Med. 2009;2(1):15-24. 10.1007/S12178-008-9039-Y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Du R, Xu G, Bai X, Li Z. Facet joint syndrome: pathophysiology, diagnosis, and treatment. J Pain Res. 2022;15:3689-3710. 10.2147/JPR.S389602 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Julious SA. Sample size of 12 per group rule of thumb for a pilot study. Pharm Stat. 2005;4(4):287-291. 10.1002/PST.185 [DOI] [Google Scholar]