Abstract

Currently, there is a lack of a comprehensive understanding of the behavior of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) in complex multimedia urban environmental systems. Taking Urumqi City as a case study, we developed an integrated multimedia urban environmental model to simulate the inter-media transport processes of PAHs across air, water, soil, sediment, vegetation, and impervious surfaces. The predictive results of this model were in good agreement with the actual monitoring data from 2021, confirming its accuracy. Notably, the simulated data for 2021 indicate that the total amount of PAHs in the soil reached 1.06 × 106 kg, accounting for 97.44% of the total PAHs in Urumqi City, highlighting soil as the primary sink for PAHs. Further analysis of transport fluxes revealed that atmospheric transfer pathways to soil and vegetation are the main mechanisms driving the distribution of PAHs in urban environments. Additionally, sensitivity analysis identified temperature, soil, and vegetation-related parameters as the primary factors influencing PAHs. Based on the simulated concentration, the risk assessment results showed that soil PAHs had a higher risk of carcinogenesis to human body. This study deepens our understanding of the behavior of PAHs in urban environments and provides insights into how human activities affect the fate and transformation of these contaminants in multimedia urban systems.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41598-025-88796-6.

Keywords: Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons, Multimedia, Urban environmental model, Fugacity, Emission factors, Risk assessment

Subject terms: Environmental sciences, Environmental impact

Introduction

Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) constitute a category of persistent bioaccumulative toxics1, and represent the most common subclass of polycyclic organic matter2.These compounds are characterized by their structures, comprising two or more aromatic benzene rings fused in linear, angular, or clustered configurations. Among the over 100 known PAHs, 16 are considered priority pollutants by the European Community and the United States Environmental Protection Agency, as indicated in Table S1 (These 16 PAHs are hereinafter termed Σ16PAHs)3. PAHs have natural and anthropogenic origins4 :Natural sources of PAHs emissions are generally negligible, and primarily include volcanic eruptions, forest fires, diagenesis, and hydrothermal processes. Anthropogenic sources are the most significant, as the incomplete combustion and pyrolysis of coal, coke, oil, gasoline, and wood, as well as the volatilization of petroleum products, all contribute to the formation of PAHs5. PAHs persist in various environmental media, including air, water, soil, and sediments, through continuous migration, dissemination, and transformation over extended periods6. In recent years, atmospheric emissions of urban PAHs have primarily involved pollution sources7. The emissions can subsequently accumulate on the ground surface via dry/wet deposition processes8. Some PAHs migrate towards plant roots, involving a sequence from the soil to the rhizosphere, followed by adsorption or absorption on the root surface9,10. However, aged PAHs exhibit low bioavailability in roots. Another pathway involves the transfer of PAHs from the atmosphere to impervious surfaces, exacerbating rainwater contamination and subsequent infiltration into surface soil or water11. PAHs in surface water can deposit in sediments and become sequestered. PAHs in surface soil, surface water, and vegetation undergo volatilization and degradation, ultimately leading to long-distance deposition and migration12. Humans are exposed to contaminated food, soil, and water due to the ubiquitous presence of PAHs in aquatic, terrestrial, and atmospheric environments. Exposure to PAHs can induce acute or chronic health effects through oral ingestion, inhalation, or dermal contact13,14. Densely populated urban areas are significant sites for emissions of PAHs and their impacts on ecological environments and humans. The nature and sources of PAHs collectively determine their widespread presence in air, water, and soil, while their behavior and fate are influenced by various environmental factors15–18. Factors that include changes in population density, the extent of urbanization, specific meteorological conditions, and unique soil properties contribute to the spatially differentiated distribution of PAHs concentrations19. Therefore, it is essential to implement precise and effective model assessments for urban environments.

Baughman and Lassiter proposed that the environmental fate of chemicals could be predicted by placing them in an idealized environment and utilizing physical and mathematical modeling methods20. Mackay adopted the fugacity perspective proposed by Lewis to view environmental processes, which to some extent simplified environmental issues, leading to the establishment of the Multimedia Environmental Fugacity Model21. The model has achieved notable success in its application across several domains, specifically in delineating migratory trajectories, spatial distribution patterns, and ultimate disposition trends of PAHs in both global and regional environments22–24. Furthermore, the model has demonstrated proficiency in precisely anticipating the concentration levels of PAHs in various environmental media, enabling comprehensive risk assessment analyses25,26. Additionally, the model facilitates the accurate forecasting of durations of PAHs within the environment and provides thorough insights into their long-term migration potential across diverse temporal and spatial scales27,28. The Level III Multimedia Fugacity Model can effectively simulate organic pollutants such as PAHs, offering certain advantages in determining the pollution levels of compounds, and exploring their migration, transformation, and fate. Model validation has shown that most models meet the calculation accuracy criteria with good fitting results. The semi-arid climate of the Chinese city of Urumqi contributes to its fragile ecological and production environment, establishing it as an essential central city in northwest China and a State Council-approved international trade center for Central and West Asia. Rapid economic development has led to severe environmental problems worldwide. Nonetheless, existing constraints in monitoring technology, and financial and equipment limitations pose significant challenges to the routine surveillance of PAHs across various environmental phases. Previous studies on the environmental behavior of PAHs in Urumqi have primarily focused on measuring their concentrations in a single environmental medium. Systematic and comprehensive studies have not been performed. Specifically, there is a lack of in-depth and systematic exploration of the distribution, migration, and fate of PAHs in the diverse environmental media (of Urumqi, including the atmosphere, water bodies, soil, and organisms). A comprehensive understanding of the environmental behavior of PAHs in Urumqi necessitates integrating behavioral information from multiple media, sources. To this end, this study introduces an innovative perspective: revealing the migration and transformation mechanisms of PAHs within the complex environmental system of Urumqi by integrating behavioral information from multiple media and sources. This new insight not only facilitates a deeper understanding of the environmental behavior of PAHs but also provides a scientific basis for formulating effective environmental protection strategies.

The primary aims of this study are (1) to ascertain the discharge of PAHs in Urumqi and (2) to assess the conveyance patterns of PAHs across boundary interactions and various environmental stages in Urumqi utilizing the Level III Multimedia Environmental Fugacity Model, with the ultimate intention of elucidating their eventual destinations.

Materials and methods

Survey of the research region and targeted contaminants

Urumqi (86°37′33″-88°58′24″E, 42°45′32″-44°00′00″N), is located in the north-central part of Xinjiang, China, within the hinterland of the Eurasian continent. The city covers a total area of approximately 1.38 × 104 km². The city is narrow from east to west and elongated from north to south, forming a horn-shaped valley plain with an average altitude of approximately 870 m. It has a mid-temperate and semi-arid climate, with southwest and northeast winds prevailing throughout the year. The diurnal temperature variation is significant, with marked differences between the summer and winter seasons. With an annual mean temperature of 6.4 °C, a precipitation level of 280 mm, and an annual average evaporation rate of 2730 mm, Urumqi represents a quintessential oasis in the arid northwest region. Urumqi governs seven districts and one county. According to the 7th National Population Census, the permanent resident population of Urumqi in 2021 is approximately 4.06 million.

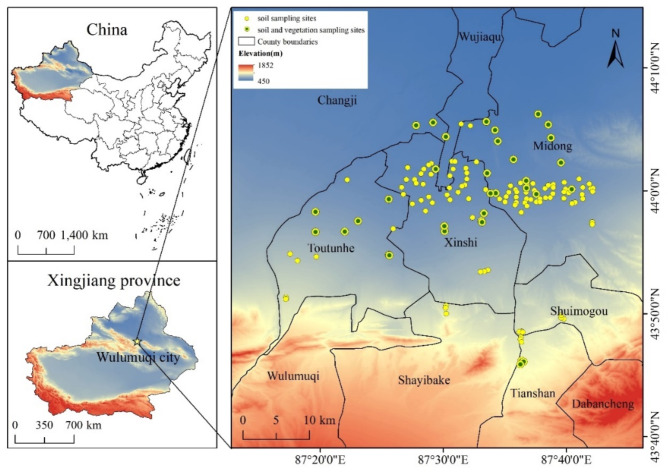

As shown in Fig. 1, sample points were distributed using a grid-based method in ArcGIS software, according to the scope of human activities. A total of 144 soil and 156 vegetation samples were collected. Additional details regarding the experimental procedures and analytical techniques employed are found in our prior research publications29–32.

Fig. 1.

Map of model area and study area (The study area is located in Urumqi, and the sample points are generally distributed in urban areas with intense human activities. The yellow circle is the soil sampling point, and the combination of green and yellow is the common sampling point of soil vegetation. The geographic map of the study area was created using ArcGIS 10.8. (URL: http://36.112.130.153:7777/DSSPlatform/index.html)).

Assessments of generation and emission of PAHs

Previous research conducted by our group has indicated that the primary sources of PAHs in Urumqi are transportation, coal combustion, and biomass burning29,30,32. The quantities of PAHs generated through natural processes are substantially lower than those produced by anthropogenic activities and are typically disregarded. Consequently, our estimation of PAHs emissions focused exclusively on three primary emission source categories: vehicular exhaust, heating emissions from coal/gas combustion and straw burning, and industrial sources. Common methods of estimating pollutant emissions include direct measurements, material balance calculations, and emission factor methods. Considering the characteristics of the pollutants, this study selected the emission factor method to determine the total PAHs emissions in Urumqi33. The specific emission factors are shown in Table S3-5 and the calculation formula is shown in Text S1. The data were sourced from the Urumqi Statistical Yearbook.

Model generalization

Based on the Multimedia Fugacity Model21, a multimedia transport and fate model for PAHs was developed by incorporating the climatic conditions and geographical factors of the Urumqi region. The model assumes that all pollutants are directly emitted into the atmosphere, with advective inputs equal to advective outputs, and initial concentrations set to zero. The model is illustrated in Fig. 2.

Fig. 2.

Fate and migration model of PAHs in Urumqi (In the interphase transport: the black dotted line represents the migration to the atmosphere, the blue solid line represents the migration to the water body, the bright yellow solid line represents the migration to the soil, the green solid line represents the migration to the vegetation, the dark yellow solid line represents the migration to the sediment, and the gray solid line represents the migration to the impervious surface).

Model parameterization

The necessary parameters and equations for the model were derived and assembled by the fugacity approach for environmental multimedia modeling, along with extensive literature reviews. Unless otherwise specified, the default input parameters and coefficients used in the model were obtained from Diamond21. These parameters include the physicochemical properties of PAHs (Table S1), environmental property parameters (Table S2), PAHs emission factor tables (Tables S3-5), formulae for calculating Z-values (Tables S8-9), and calculations of interphase transfer coefficient D-values (Tables S10-11).

Mass balance equation

The model comprehensively considered the processes of PAHs diffusion, dissolution, dry and wet deposition, and surface runoff between adjacent phases. Assuming steady-state conditions, the mass balance equation for each phase can be expressed as follows:

Air

|

1 |

Water:

|

2 |

Soil:

|

3 |

Sediment, Sed

|

4 |

Film:

|

5 |

Vegetation:

|

6 |

where, E (mol·h⁻¹) represents the emission rate of PAHs; fi (Pa) denotes the fugacity of PAHs in medium i; Di−j (mol·(h·Pa)⁻¹) represents the interphase transfer rate of PAHs from medium i to medium j; DR(i) (mol·(h·Pa)⁻¹) represents the degradation rate of PAHs in medium i, where i and j refer to A, F, W, S, Sed, and V, in (1) to (6), respectively.

Model solution

MATLAB software was employed to compute the fugacity of PAHs across various phases using the aforementioned model structure, parameter suite, and equilibrium equations. The equilibrium concentrations, storage capacities, and transport fluxes of PAHs within each phase were determined by resolving the subsequent equations24:

|

7 |

|

8 |

|

9 |

where C (mol/m³) is the pollutant concentration; Z (mol/(m³·Pa)) is the fugacity capacity of each medium; S (t) is the quantity of pollutants stored in the phase; V (m³) is the phase volume; M (g/mol) is the molar mass of the pollutant; and F (mol/h) is the inter-medium transfer flux.

The principal distribution patterns and migration mechanisms of PAHs in Urumqi were elucidated by comparing the comparative analysis of equilibrium concentrations, sequestration capacities, and exchange fluxes across diverse phases.

Model evaluation

Due to their openness, natural systems are constantly dynamic and challenging to replicate precisely34. This characteristic introduces complexity and uncertainty into the model, leading to non-unique prediction outcomes. Such uncertainty limits the direct verification of the model feasibility. We adopted an indirect but feasible method to evaluate the model performance: by comparing the model-predicted concentrations with actual observational data35. To further validate the reliability of the model, we adopted two statistical indicators: the Nash-Sutcliffe Efficiency (NSE) and the Root Mean Squared Error (RMSE), and evaluated them based on comprehensive and accurate observational data of both soil and vegetation. The NSE measures the consistency between model simulations and observed values, with a value close to 1 indicating a high degree of agreement and strong predictive capability36. Conversely, the RMSE reflects the average deviation between predicted and actual values, with smaller values indicating more accurate predictions37. By combining these two statistical methods, we can comprehensively assess the reliability of the model, providing robust support for subsequent optimization and application.

|

10 |

|

11 |

where ‘a’ represents the measured value, ‘b’ represents the simulated value, and ‘n’ represents the number of measured values.

Sensitivity and uncertainty analysis methods

Sensitivity and uncertainty analyses are crucial to accurately delineate the uncertainties and variabilities within environmental fate models38,39. This analysis focused on the direct impact of fluctuations in input parameters on prediction outcomes, with the aim of enhancing prediction accuracy and credibility. To quantify the relative alteration in the output variable Y and thereby assess the isolated impact of the input parameter X, we introduced a 10% variation in each parameter. The sensitivity coefficient S, defined as the ratio of the relative change in the output to the relative change in the input [(Δoutput/output) / (Δinput/input)], emerged as a pivotal metric. The absolute value of S signifies the extent of influence, whereas its sign denotes the direction of impact. For parameters exhibiting high sensitivity (S > 0.5), we used Monte Carlo simulations on the MATLAB platform to quantify the associated uncertainty. This involved calculating the coefficient of variation (CV) through 10,000 iterations and generating random numbers based on the means and standard deviations of the input parameters. A higher CV value indicates greater uncertainty in the model predictions.

Risk assessment

Soil incremental lifetime cancer risk model

For risk assessment, we selected soil, the medium with the highest overall concentration. We employed the Incremental Lifetime Cancer Risk (ILCR) model, which estimates human carcinogenic risk levels from exposure to PAHs through inhalation, dermal contact, and non-dietary ingestion of soil12. Detailed computational methods are provided in Supplementary Material Text S3. Furthermore, to reduce uncertainty in exposure and toxicity assessments arising from variability in exposure parameters, we incorporated the Monte Carlo probabilistic model. In this study, we utilized Crystal Ball software to process the collected data, aiming to obtain more precise simulation results, and set 20,000 iterations for the calculations.

Ecological risk assessment

In the process of ecological risk assessment of PAHs, an important consideration is the toxic equivalent concentration (TEQ). This comprehensive index is derived by weighted summing the concentrations of various PAHs in soil with their respective toxic effects and converting them to the toxic effects of the most representative carcinogen, BaP10. See supplementary text S4 for details.

Results and discussion

Emission inventory of Urumqi PAHs

As a pivotal tool in depicting the pollution landscape resulting from human activities, regional emission inventories elaborate the spatiotemporal characteristics of atmospheric PAHs emissions and enable precise quantification35. In Table 1, under the assumption that all pollutants are directly released into the atmosphere, this study determined that the total annual emissions of 16 major PAHs in Urumqi City in 2021was approximately 1108 t. Road vehicle emissions dominated, with a substantial volume of approximately 1059 t, highlighting that automotive exhaust is the primary source of atmospheric PAHs pollution. This finding is similar to the pattern of PAHs emissions in the Haizhou Bay area but significantly exceeds the estimated emissions of 687.32 t in Haizhou Bay24. This difference in the quantity of emissions emphasizes the interregional differences in pollution characteristics and the urgency of governance in regulating emissions.

Table 1.

Urumqi Air PAHs Emission Inventory (unit: t/y).

| Tail gas | Heat Supply | Industry | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gasoline vehicle | Diesel vehicle | Natural gas | Domestic garbage | Straw discharge | Natural gas | Coal | Gasoline | Diesel oil | Crude oil | Natural gas | Other energy production | Sum | |

| Nap | 1.05 × 101 | 0.00 | 1.59 | 4.87 × 10− 1 | 1.51 × 10− 1 | 1.08 | 4.96 × 10− 4 | 1.34 × 10 − 5 | 1.87 × 10− 5 | 4.70 × 10− 3 | 8.32 × 10− 1 | 3.81 | 1.85 × 101 |

| Acy | 1.32 | 3.28 × 10 − 1 | 1.22 × 10− 1 | 2.42 × 10− 1 | 1.18 × 10− 2 | 8.35 × 10− 2 | 1.94 × 10− 2 | 8.19 × 10 − 6 | 1.70 × 10− 5 | 4.74 × 10− 3 | 6.42 × 10− 2 | 8.18 × 10− 1 | 3.02 |

| Ace | 5.36 | 1.19 | 2.21 | 1.59 × 10− 2 | 7.33 × 10− 5 | 1.51 | 2.07 × 10− 2 | 6.71 × 10 − 6 | 1.14 × 10− 5 | 5.48 × 10− 3 | 1.16 | 2.28 × 10− 1 | 1.17 × 101 |

| Flu | 8.33 | 1.46 | 6.87 × 10− 3 | 4.10 × 10− 3 | 1.86 × 10− 4 | 4.69 × 10− 3 | 1.84 × 10− 2 | 7.92 × 10 − 6 | 1.45 × 10− 5 | 3.77 × 10− 3 | 3.60 × 10− 3 | 3.81 × 10− 1 | 1.02 × 101 |

| Phe | 2.68 × 101 | 1.50 × 101 | 1.95 × 10− 2 | 2.54 | 1.68 × 10− 2 | 1.33 × 10− 2 | 2.34 × 10− 2 | 8.57 × 10 − 6 | 1.71 × 10− 5 | 1.14 × 10− 2 | 1.02 × 10− 2 | 2.47 × 10− 1 | 4.47 × 101 |

| Ant | 5.36 | 1.25 × 101 | 5.99 × 10− 3 | 1.41 | 4.91 × 10− 3 | 4.08 × 10− 3 | 1.93 × 10− 2 | 7.03 × 10 − 6 | 1.14 × 10− 5 | 5.45 × 10− 3 | 3.14 × 10− 4 | 2.28 × 10− 1 | 1.96 × 101 |

| Fla | 3.62 × 101 | 5.71 | 1.19 × 10− 2 | 2.19 | 6.82 × 10− 3 | 8.12 × 10− 3 | 2.23 × 10− 2 | 7.68 × 10 − 6 | 1.59 × 10− 5 | 5.74 × 10− 3 | 6.24 × 10− 3 | 7.61 × 10− 1 | 4.49 × 101 |

| Pyr | 5.19 × 101 | 9.25 | 4.70 × 10− 2 | 2.08 | 6.03 × 10− 3 | 3.21 × 10− 2 | 2.13 × 10− 2 | 7.43 × 10 − 6 | 1.54 × 10− 5 | 2.47 × 10− 3 | 2.46 × 10− 2 | 4.95 × 10− 1 | 6.38 × 101 |

| BaA | 1.41 × 101 | 3.23 × 101 | 1.91 × 10− 2 | 2.09 | 1.84 × 10− 3 | 1.30 × 10− 2 | 1.84 × 10− 2 | 6.05 × 10 − 6 | 1.44 × 10− 5 | 6.25 × 10− 3 | 1.00 × 10− 2 | 8.94 × 10− 2 | 4.86 × 101 |

| Chr | 3.94 × 101 | 1.87 × 101 | 6.96 × 10− 4 | 3.54 | 2.32 × 10− 3 | 4.75 × 10− 4 | 1.88 × 10− 2 | 6.30 × 10 − 6 | 1.19 × 10− 5 | 4.28 × 10− 3 | 3.65 × 10− 4 | 3.23 × 10− 1 | 6.20 × 101 |

| BbF | 4.38 × 102 | 0.00 | 6.45 × 10− 3 | 1.99 | 1.81 × 10− 3 | 4.39 × 10− 3 | 1.64 × 10− 2 | 6.54 × 10 − 6 | 1.19 × 10− 5 | 4.27 × 10− 3 | 3.38 × 10− 3 | 2.09 × 10− 1 | 4.40 × 102 |

| BKF | 7.79 | 5.32 × 101 | 1.60 × 10− 2 | 2.77 | 1.69 × 10− 3 | 1.09 × 10− 2 | 1.71 × 10− 2 | 5.67 × 10 − 6 | 1.23 × 10− 5 | 3.77 × 10− 3 | 8.37 × 10− 3 | 1.54 × 10− 1 | 6.40 × 101 |

| BaP | 8.33 | 1.06 × 102 | 4.40 × 10− 3 | 4.90 | 8.91 × 10− 4 | 3.00 × 10− 3 | 1.52 × 10− 2 | 5.75 × 10 − 6 | 1.10 × 10− 5 | 3.81 × 10− 3 | 2.30 × 10− 3 | 2.28 × 10− 1 | 1.19 × 102 |

| IcdP | 2.51 × 101 | 1.10 × 10− 1 | 3.39 × 10− 3 | 2.66 | 0.00 | 2.31 × 10− 3 | 1.90 × 10− 2 | 5.73 × 10 − 6 | 1.06 × 10− 5 | 4.76 × 10− 3 | 1.78 × 10− 3 | 2.09 × 10− 1 | 2.82 × 101 |

| DahA | 3.72 × 101 | 2.38 × 10− 1 | 1.15 × 10− 3 | 1.24 | 0.00 | 7.85 × 10− 4 | 1.70 × 10− 2 | 4.92 × 10 − 6 | 1.02 × 10− 5 | 5.11 × 10− 3 | 6.03 × 10− 4 | 7.04 × 10− 2 | 3.88 × 101 |

| BghiP | 8.76 × 101 | 2.72 × 10− 2 | 4.86 × 10− 3 | 2.66 | 0.00 | 3.31 × 10− 3 | 1.70 × 10− 2 | 6.38 × 10 − 6 | 1.12 × 10− 5 | 1.25 × 10− 3 | 2.53 × 10− 3 | 1.58 × 10− 1 | 9.05 × 101 |

| ∑16PAHs | 8.04 × 102 | 2.56 × 102 | 4.07 | 3.08 × 101 | 2.06 × 10− 1 | 2.77 | 2.84 × 10− 1 | 1.14 × 10 − 4 | 2.15 × 10− 4 | 7.72 × 10− 2 | 2.13 | 8.41 | 1.11 × 103 |

The composition of PAHs was analyzed in detail, and it was found that BbF was the main single compound emitted, the second and third were BaP and Bghip, respectively, while Acy had the lowest emission. These compounds accounted for 39.74%, 10.7%, 8.17%, and 0.27% of total PAHs, respectively. High-molecular-weight (HMW, 5–6 rings) PAHs predominated, comprising 70.48% of the total emissions. Medium-molecular-weight (MMW, 4 rings) and low-molecular-weight (LMW, 2–3 rings) PAHs accounted for 19.8% and 9.72%, respectively. Particularly alarming is the fact that the annual total emissions of the eight recognized carcinogenic PAHs (BaA, Chr, BbF, BkF, BaP, IcdP, DahA, and BghiP) accounted for 80.47% of the total. These figures suggest that authorities should take immediate steps to increase the proportion of clean energy vehicles in public use.

Model evaluation

The core aspect lies in model evaluation within the modeling process. Given the scarcity of historical monitoring data for environmental media such as water bodies and sediments in Urumqi, this study draws on the model evaluation method employed by Shi, which focuses on comparing the concentrations of PAHs in soil and vegetation, two media with abundant empirical data24. Based on the research by Sun, when the simulated values are within the same order of magnitude as the measured values, they are considered to be within a reasonable range35. By comparing the empirical data on PAHs concentrations in soil and vegetation in Urumqi with existing research findings, we have revealed the limitations of the current model and identified clear directions for future improvements. Tables S13 and Fig. 3 demonstrate that the model-estimated concentrations of PAHs in soil align well with the reasonable range of previously monitored data. Despite the complexity of the model and various potential influencing factors leading to a relatively low NSE value (0.21), it still indicates a correlation between the model’s simulated results and the measured data. Additionally, the RMSE value (112.12 ng/g) highlights the range of error between the model’s simulations and the measured data. We acknowledge these deviations and will conduct an in-depth analysis of the sources of error to explore potential improvements, aiming to enhance the model’s predictive capability and accuracy. For vegetation, except for LMW PAHs, the estimated concentrations also corresponded well with the ranges of previous data. Considering the limited field data and variations in PAHs absorption among vegetation types due to differences in lipid content26, as well as the model’s assumption of zero initial background concentration, which underestimated the concentrations of LMW PAHs in vegetation. The NSE for vegetation reached an impressive value of 0.99, suggesting an extremely high level of accuracy in the model’s predictions. Despite an RMSE of 57.15 ng/g, which is within an acceptable margin, this further supports the model’s reliability. It is worth highlighting that for all soil samples and the majority of vegetation samples, the difference between the measured average concentrations of PAHs and the simulated values did not surpass one logarithmic unit. This underscores the model’s precision and its capability to adapt to the unique environmental characteristics of the Urumqi region. Although limited by the availability of data, this study only utilized data from 2021 to verify the accuracy of the environmental multimedia enrichment model. However, this year’s dataset underwent rigorous screening and validation to ensure its representativeness in reflecting the characteristics of PAHs pollution in Urumqi, the completeness of data records, and the high quality of measurement data.

Fig. 3.

Comparison of simulated and measured PAHs values (a for soil, b for vegetation).

Simulation of distribution characteristics and fate of PAHs using the multimedia Fugacity Model

In order to compare the concentration characteristics of PAHs in different media, the unit is unified as ng/m3, and the specific conversion mode is shown as Text S2. As illustrated in Fig. 4, the distribution characteristics of PAHs in environmental media were notable, with concentrations increasing as the molecular weight increased. The highest concentrations were observed for HMW PAHs, followed Conversely, HMW PAHs by MMW PAHs, and the lowest for LMW PAHs. LMW PAHs, due to their low lipophilicity, persistence, and sorption capacity, LMW PAHs are predominantly present in the gas and aqueous phases40. They are sensitive to photodegradation, which results in a sharp decline in their concentrations under sunlight exposure. Conversely, HMW PAHs, which are characterized by their high molecular weights and low vapor pressures, readily adsorb to particulate matter, forming particulate phase PAHs41. These PAHs are effectively deposited in media, such as soil and vegetation, and accumulate at high concentrations42. Furthermore, they exhibit strong resistance to photodegradation, which exacerbates their enrichment43.

Fig. 4.

Concentrations of 16 PAHs in each environmental chamber.

In the process of in-depth exploration of the concentration distribution of 16 kinds of PAHs (Σ16PAHs) in different environmental media, we found that the concentration was the highest in soil, followed by vegetation, impervious surface, sediment, water, and atmosphere, decreasing in order. This distribution pattern may be attributed to the chemical aging process of PAHs and their short atmospheric lifetimes, which lead to their rapid transformation into the particulate phase and subsequent migration away from their sources over time44. Additionally, dominant reactions with hydroxyl radicals result in the conversion of PAHs by oxidants45, thereby reducing their concentrations in the gas phase. Soil is the primary reservoir for Σ16PAHs, with high concentration levels (5.9 × 102) primarily due to the strong adsorption capacity of the soil medium for PAHs and its extensive surface area. The lower PAHs content in soil from Urumqi compared to soils from Nanjing and Dingshu may be attributed to the relatively lower level of urbanization in Urumqi compared to Nanjing46. In previous studies, soil samples were collected from ornamental vegetation areas in parks and vegetable farmland. Vegetation planting may facilitate the loss of LMW PAHs, diluting their concentrations in the surface soil and promoting their migration into the subsoil47, which explains the slightly higher simulated concentrations of LMW PAHs in the soil compared to the actual measurements. PAHs enter plants through the foliage and roots. The waxy layer of leaves strongly adsorbs PAHs and accumulates them in the air, while stomata also absorb and transport them for metabolism, affecting the concentrations of Σ16PAHs. Roots are the primary pathway for soil entry of PAHs via soil solution/diffusion to the root surface and subsequent passage through cellular membrane mechanisms into the root system. The PAHs are then distributed throughout the plant via the water/nutrient transport network, resulting in widespread accumulation48. Based on the concentration characteristics of Σ16PAHs in various media, precise governance measures can be implemented to optimize environmental quality continuously.

According to formula 8, using the simulated concentrations, we computed the storage quantities for the 16 PAHs across six distinct environmental media, as depicted in Fig. 5. Subsequent to their migration and transformation processes, the cumulative storage of these 16 PAHs in the six media was 1089 t. Analyzing the total quantity (SUM), the storage of PAHs in soil was the most significant, reaching 1.06 × 106 kg, far exceeding that of other media. This could be attributed to the strong adsorption and accumulation capacity of the soil for highly lipid-soluble PAHs6. Once present in the soil, PAHs undergo aging to form non-extractable or bound residues49. Following soil, the storage quantities in vegetation (6.67 × 101 kg), atmosphere (2.73 × 104 kg), and water (4.96 × 102 kg) were notable, while the storage quantities in sediments (1.50 × 10− 4 kg) and impervious surfaces (1.62 × 10− 7 kg) were negligible. Some studies indicate that organic carbon (TOC) content, sediment particle size, and clay content may affect the distribution of PAHs50. In this study, it may be because the geographical location is in the arid urban area, the sediment is mainly sandy soil with poor viscosity, and due to the low precipitation and small water area, the concentration of PAHs in the sediment is low. This clearly indicates that soil is the primary reservoir of PAHs in the natural environment. Although the amount of PAHs stored in the atmosphere is relatively low, they still constitute a non-negligible source of pollution. Vegetation also plays an important role in the storage, migration, and transformation of PAHs, demonstrating its potential as a storage medium. To control environmental PAHs pollution effectively, scientific and reasonable governance measures should be implemented to target specific media and PAHs types.

Fig. 5.

Map of 16 kinds of PAHs storage in each environment chamber.

Simulation of PAHs transboundary migration

This study is grounded in the Level III Fugacity Model for environmental multimedia and innovatively incorporates the unique environmental factors of the Urumqi region to develop a highly adaptable steady-state multimedia model tailored to the arid and semi-arid conditions of this area. By analyzing the degradation rate data of Σ16PAHs (as shown in Fig. 6) across different environmental media, we can delve more deeply into the complexity and influencing factors of PAHs degradation in various media, as well as the potential impacts of these degradation processes on the environment and human health. The slow degradation of PAHs in the atmosphere (4.31 × 10− 3 mol/h) may be attributed to photochemical reactions influenced by light intensity, clouds, and particulate matter. In contrast, oxidation reactions are constrained by the concentrations of oxidants (such as ozone and •OH) affected by meteorological conditions and emission sources51, collectively limiting degradation efficiency. In contrast, the degradation of PAHs in soil occurs at a relatively high rate (1.86 × 103 mol/h), primarily due to the abundant microbial communities and diverse degradation mechanisms. PAHs-degrading bacteria resident in soil (such as Pseudomonas, Sphingomonas, Brevibacterium, Arthrobacter, Nocardia, and Mycobacterium) can metabolize PAHs as sources of carbon and energy52. The degradation of PAHs in sediments is extremely slow (7.28 × 10− 9 mol/h) and is inhibited by low oxygen levels, low light availability, and low exchange rates that suppress microbial activity53,54. Furthermore, PAHs readily adsorb onto particles or are encapsulated within organic matter, which reduces their bioavailability and contributes to their persistence. Vegetation has a significant decomposition rate of PAHs, the specific value can reach 2.36 × 101 mol/h, indicating that vegetation plays an important role in environmental purification. Vegetation in semi-arid regions relies on enhanced oxidoreductase activity to maintain the intracellular environmental balance and enhance tolerance to extreme conditions. Serving as an efficient tool for PAHs degradation, oxidoreductase uniquely combines redox functions, facilitating electron transfer between substrates and receptors to produce intermediates, such as quinones or hydroxylated PAHs, which are gradually degraded into harmless substances55. The relative and absolute abundances of potential PAHs-degrading bacteria in vegetation (such as rice paddies) are higher than those in the rhizosphere soil56.

Fig. 6.

The migration trend of Σ16PAHs in Urumqi city (In the interphase transport: the black dotted line represents the migration to the atmosphere, the blue solid line represents the migration to the water body, the bright yellow solid line represents the migration to the soil, the green solid line represents the migration to the vegetation, the dark yellow solid line represents the migration to the sediment, and the gray solid line represents the migration to the impervious surface).

The observed migration rate from the atmosphere to water bodies was only 8.01 × 10− 6 mol/h, indicating a relatively low transfer efficiency. This is attributed to the fact that atmospheric PAHs primarily enter water bodies through meteorologically driven deposition mechanisms, including dry deposition (e.g., carried by dust) and wet deposition (e.g., washed by rainfall), which are significantly influenced by meteorological fluctuations (wind speed, precipitation intensity) and concentrations of atmospheric PAHs. In addition, physicochemical adsorption at the water surface slows the migration process. In contrast, the migration rate of PAHs from the atmosphere to the soil is high (2.29 × 103 mol/h), with PAHs accumulating and stabilizing in the soil through dry and wet deposition. However, this accumulation is reversible, and PAHs can be released back into the atmosphere under specific conditions, forming a dynamic equilibrium. This process is influenced by environmental temperature, soil organic matter, humidity, and meteorological conditions57. For the migration of PAHs from the atmosphere to impervious surfaces, the rate remained low at 1.26 × 10− 5, reflecting the low adsorption characteristics of impervious materials for PAHs. The migration rate of PAHs from the atmosphere to vegetation, reached 3.35 × 101 mol/h, demonstrating the efficient absorption capacity of plant leaves for PAHs. Mechanisms responsible for transferring PAHs to plant tissues include absorption through the waxy leaf cuticle or stomata, adsorption by soil particles, and absorption by roots through transpiration. Additionally, PAHs can be released into the atmosphere through transpiration or incorporated into the soil at the end of their life cycle, forming a local ecological cycle47,58. PAHs in water bodies migrated to sediments at a rate of 1.64 × 10− 5 mol/h, which, although not fast, reveals a dynamic equilibrium of PAHs at the water-sediment interface. PAHs on impervious surfaces have a limited migration capacity and mainly accumulate through atmospheric deposition, with difficulty in migrating appreciably through other pathways.

Therefore, the soil plays a pivotal role in the degradation and migration of PAHs in the Urumqi region, and its efficient degradation capability is crucial for controlling PAHs contamination. The physicochemical properties of environmental media, molecular structure of PAHs, and physiological activities of vegetation also exert significant influences on their degradation and migration processes. Future research should delve deeper into the degradation mechanisms within the soil, particularly focusing on the roles of microbial communities and their specific enzymes. Additionally, enhanced monitoring and management of the vegetation-soil-atmosphere exchange processes are essential.

Parameter sensitivity and uncertainty

A sensitivity analysis of the model outputs to the concentrations of PAHs in six different media was performed. The results are shown in Fig.S3. The sensitivity analysis revealed a series of key findings. The most critical input data for atmospheric concentrations of PAHs included temperature and parameters describing the soil/vegetation-air interface exchange processes. This can be attributed to the fact that soil and vegetation serve as significant sinks that are capable of storing and accumulating substantial amounts of PAHs from the atmosphere. In aquatic bodies, concentrations of PAHs are significantly influenced by Henry’s constant, temperature, and other soil parameters. Specifically, as the temperature increases, the concentrations of PAHs in water tend to decrease, potentially because of accelerated degradation or volatilization processes59. In the soil media, soil density, organic carbon content, and soil diffusion path length were the primary influencing factors. Changes in soil density may affect soil porosity and moisture content, subsequently influencing the adsorption and migration of PAHs60. Organic carbon, which serves as the primary adsorption site for PAHs in soil, plays a crucial role in immobilizing PAHs61. The soil diffusion path length directly affects the migration speed and distribution range of PAHs in soil. The sensitivity of vegetation to PAHs is influenced by a combination of factors. Notably, vegetation density and lipid content significantly positively affected the PAHs adsorption and accumulation capacities. Increased vegetation density provides more adsorption surface area and sites for PAHs, whereas lipids, owing to their strong affinity for PAHs, make vegetation with a high lipid content more prone to accumulating PAHs. However, when the concentrations of PAHs at the vegetation-air interface reach a certain threshold, the adsorption or accumulation capacity of vegetation may be constrained by saturation or other factors. For PAHs in sediments, sediment density has a significant positive effect on their adsorption or accumulation capacity, whereas temperature and Henry’s constant have significant negative effects. On impervious surfaces, the sensitivity of PAHs is primarily influenced by Henry’s constant, octanol-water partition coefficient, temperature, and organic matter content of the impervious surface. Among these, the octanol-water partition coefficient and organic matter content of impervious surfaces have significant positive effects on the adsorption or accumulation capacity of PAHs, whereas Henry’s constant and temperature have significant negative effects. Multiple factors jointly influence the PAHs concentrations in different media, and the mechanisms and degrees of influence of these factors vary across media. These findings provide crucial insights into our understanding of the migration, transformation, and fate of PAHs in the environment and offer scientific guidance for formulating effective PAHs pollution prevention and control strategies.

The Monte Carlo method was employed during the in-depth analysis of the impact of uncertainty on the prediction of environmental pollutant concentrations for 2021. The coefficients of variation for most of the model input parameters and pollutant concentrations were < 1. This finding indicates that under the current simulation conditions, the fluctuation ranges of both model parameters and pollutant concentrations are relatively narrow, suggesting that the influence of uncertainty on prediction outcomes remains low. Despite the uncertainty, our predictive models maintained high stability and accuracy in most scenarios.

Risk assessment

Soil incremental lifetime cancer risk model

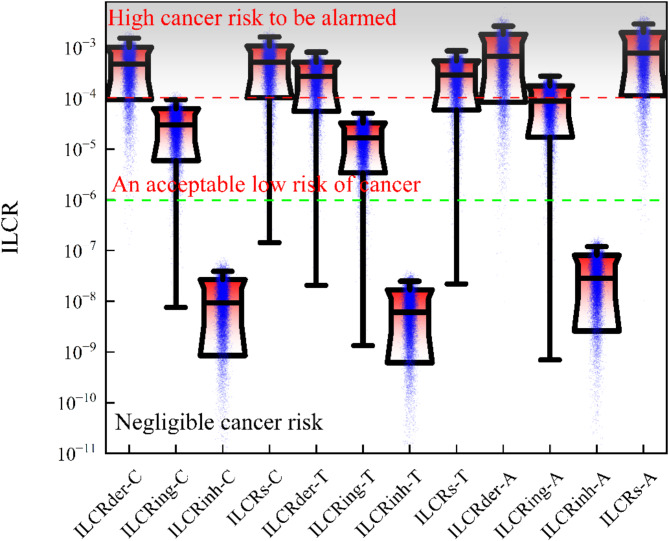

As illustrated in Fig. 7, the conclusion drawn from 20,000 iterations of calculations indicates that the probabilities of high carcinogenic risk (ILCRs > 10− 4) faced by children, adolescents, and adults exposed to soil are 90.7%, 82.06%, and 91.54%, respectively. It is noteworthy that such high probabilities of carcinogenic risk are partly attributed to the overestimation in model simulations. After an in-depth analysis of the potential carcinogenic risk of soil for different age groups, we found that ILCRs in soil was highest in adults, followed by children, and then adolescents. Adults have increased skin contact with soil due to work or outdoor activities, and children are second likely due to accidental ingestion of soil and frequent play behaviors. For all age groups, soil ingestion and skin contact, particularly in adults, are the primary factors contributing to the overall carcinogenic risk, whereas the ILCR resulting from respiratory inhalation is negligible in comparison.

Fig. 7.

Distribution of accidental ingestion (ILCRing), inhalation (ilcrh), skin contact (ILCRder), soil and total cancer risk value (ILCRs) in different age groups(C, T, A representing child, teenager, adult, respectively).

Ecological risk assessment

Based on the toxicity equivalence method, the total toxicity equivalence value (total TEQBaP) for 16 PAHs in the simulated soil is 1.11 × 102 ng/g. The total toxicity equivalence value of these 16 PAHs is primarily contributed by 7 carcinogenic PAHs, accounting for 99% of the total. The Netherlands has established regulations for TEQBaP values in soil, stipulating that a concentration exceeding 33 µg/kg poses a potential ecological risk62. According to this standard, the simulated soil poses a potential ecological risk. However, the concentrations of all individually tested PAHs meet the requirements of the “Soil Environmental Quality Risk Control Standard for Soil Contamination of Agricultural Land” (GB 15618 − 2018) and the “Soil Environmental Quality Risk Control Standard for Soil Contamination of Development Land” (GB36600-2018)63. In view of this, it is suggested that China consider establishing stricter control standards for PAHs in soil to ensure environmental safety.

Conclusions

Utilizing Urumqi as an illustrative example, we devised an exhaustive urban environmental model that encompasses a diverse array of media specifically tailored to simulate the migration pathways of PAHs across air, water bodies, soil matrices, sediment layers, vegetation canopies, and impervious surfaces. The model underwent rigorous validation, yielding predictions that closely agreed with field-monitoring data collected in Urumqi in 2021, substantiating the model’s precision and dependability. Of particular note, the simulation outcomes for that year disclosed that the aggregate quantity of PAHs was 1.06 × 106 kg, constituting 97.44% of the overall inventory of PAHs within this urban milieu. This underscores the central role of soil as the primary repository of PAHs and elucidates a crucial aspect of PAHs distribution patterns in urban settings. By analyzing transport fluxes, we identified atmospheric transport vectors to the soil and vegetation as the primary forces shaping the distribution dynamics of PAHs within an urban environment. This revelation offers new perspectives on the migration, transformation, and intermediate interactions of PAHs in urban ecosystems. Moreover, we performed an in-depth examination of the sensitivity of the concentrations of PAHs across various media. The results reveal that PAHs concentrations in diverse media are influenced by a multitude of factors, with each factor exerting distinct mechanisms and degrees of influence across different media. Temperature and soil- and vegetation-related parameters emerged as significant determinants of PAHs migration and transformation. Risk evaluation showed that soil PAHs had a high carcinogenic risk to human body, and the ecological risk could not be ignored. In this study, we also uncovered some new insights and discoveries, which further enhanced our understanding of the behavior patterns of PAHs in urban environments. Firstly, we revealed that the migration and transformation of PAHs in urban environments is a complex process involving the interaction of multiple media and factors. Secondly, our research emphasized the importance of urban planning and environmental management in reducing PAHs pollution, especially in controlling atmospheric transport and soil accumulation. Lastly, our findings provide a scientific basis for formulating effective PAHs pollution prevention and control strategies, offering significant guidance for future urban environmental management and protection. These new insights and discoveries not only enriched our knowledge of PAHs behavior patterns in urban environments but also paved new directions and ideas for future research. Future studies can further explore the long-term impacts of PAHs in urban environments, the interaction mechanisms between different media, and more effective pollution control strategies.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Special fund project for central guidance of local scientific and technological development [grant No. ZYYD2023A04], National Natural Science Foundation of China [grant No. 51968067], the Fundamental Research Funds for the Autonomous Region Universities [grant No. XJEDU2023P006], Graduate Education Innovation Program of Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region of China [grant No. XJ2024G101], Key Laboratory of Degraded and Unused Land Consolidation Engineering, the Ministry of Natural Resources [grant No. SXDJ2024-14], and the Student Research Training Project of Xinjiang University (China) [grant No. XJ2024G101].

Author contributions

Junxuan Ma: Writing–original draft, Methodology, Investigation, Conceptualization. Nuerla Ailijiang: Writing–original draft, Visualization, Methodology, Investigation, Data curation, Conceptualization. Anwar Mamat: Investigation, Conceptualization. Yixian Wu: Investigation, Conceptualization. Xiaoxiao Luo: Investigation, Conceptualization. Min Li: Investigation, Conceptualization.

Data availability

The authors declare that the data supporting the findings of this study are available within the paper and its Supplementary Information files. Should any raw data files be needed in another format they are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request. Data will be made available from the corresponding author on reasonable request of reader.

Declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Fernández-Martínez, N. F. et al. Relationship between exposure to mixtures of persistent, bioaccumulative, and toxic chemicals and cancer risk: a systematic review. Environ. Res.188, 109787 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Xu, H. et al. Combustion-derived particulate organic matter associated with hemodynamic abnormality and metabolic dysfunction in healthy adults. J. Hazard. Mater.418, 126261 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Liu, J. et al. Environmental dose of 16 priority-controlled PAHs induce endothelial dysfunction: an in vivo and in vitro study. Sci. Total Environ.919, 170711 (2024). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gurgatz, B. M. et al. Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in a natural Heritage Estuary influenced by anthropogenic activities in the South Atlantic: integrating multiple source apportionment approaches. Mar. Pollut Bull.188, 114678 (2023). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tulcan, R. X. S. et al. PAHs contamination in ports: Status, sources and risks. J. Hazard. Mater.475, 134937 (2024). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pi, W. et al. Cross-media transfer of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in the Naples metropolitan area, southern Italy. Sci. Total Environ.941, 173695 (2024). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hites, R. A. Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons in the atmosphere near the Great lakes: why do their concentrations vary? Environ. Sci. Technol.55, 9444–9449 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Garagnon, J., Perrette, Y., Naffrechoux, E. & Pons-Branchu, E. Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon record in an urban secondary carbonate deposit over the last three centuries (Paris, France). Sci. Total Environ.905, 167429 (2023). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yang, H. et al. Novel insights into the Promoted Accumulation of Nitro-Polycyclic Aromatic hydrocarbons in the roots of Legume plants. Environ. Sci. Technol.58, 2058–2068 (2024). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shi, W. et al. Distribution and ecological risk of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in wastewater treatment plant sludge and sewer sediment from cities in Middle and Lower Yangtze River. Sci. Total Environ.10.1016/j.scitotenv.2023.163212 (2023). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cai, T. et al. Effects of total organic carbon content and leaching water volume on migration behavior of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in soils by column leaching tests. Environ. Pollut. 254, 112981 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nuerla, A. et al. Distribution, sources, and risk assessment of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in surface soils and plants from industrial and agricultural areas, Junggar Basin, Xinjiang. J. Environ. Manage.369, 122340 (2024). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mallah, M. A. et al. Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon and its effects on human health: an updated review. Chemosphere.296, 133948 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Venkatraman, G. et al. Environmental impact and human health effects of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons and remedial strategies: a detailed review. Chemosphere.351, 14127 (2024). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Garagnon, J. et al. Impact of land-use on PAH transfer in sub-surface water as recorded by CaCO3 concretions in urban underground structures (Paris, France). Environ. Pollut. 357, 124437 (2024). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lian, X. et al. Measurement of the mixing state of PAHs in individual particles and its effect on PAH transport in urban and remote areas and from major sources. Environ. Res.214, 114075 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Perala-Dewey, J., Orr, K., Hageman, K. J., Zawar-Reza, P. & Shahpoury, P. Atmospheric Transport of Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons into three Alpine valleys: influence of local-scale wind patterns and Chemical partitioning. Environ. Sci. Technol.57, 13114–13123 (2023). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Xu, X. et al. Formation, migration, derivation, and generation mechanism of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons during frying. Food Chem.425, 136485 (2023). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ma, L., Li, Y., Yao, L. & Du, H. Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in soil-turfgrass systems in urban Shanghai: contamination profiles, in situ bioconcentration and potential health risks. J. Clean. Prod.289, 125833 (2021). [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lassiter, R. R., Baughman, G. L., Burns, L. A., FATE OF TOXIC & ORGANIC SUBSTANCES IN THE AQUATIC ENVIRONMENT. Elsevier,. in State-of-the-Art in Ecological Modelling 219–246 (1979). 10.1016/B978-0-08-023443-4.50010-5

- 21.Mackay, D. Finding fugacity feasible. Environ. Sci. Technol.13, 1218–1223 (1979). [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chen, Z. et al. Presence of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons among multi-media in a typical constructed wetland located in the coastal industrial zone, Tianjin, China: occurrence characteristics, source apportionment and model simulation. Sci. Total Environ.800, 149601 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Li, R., Hua, P., Zhang, J. & Krebs, P. Characterizing and predicting the impact of vehicular emissions on the transport and fate of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in environmental multimedia. J. Clean. Prod.271, 122591 (2020). [Google Scholar]

- 24.Shi, W. et al. Analysis of the multi-media environmental behavior of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) within Haizhou Bay using a fugacity model. Mar. Pollut Bull.187, 114603 (2023). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hasanoglu, S. & Göktaş, R. K. Fugacity-based analysis of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon pollution in Izmit Bay, Turkey: an analytical framework for assessment with limited data. Mar. Pollut Bull.182, 113990 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nie, N. et al. Environmental fate and health risks of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in the Yangtze River Delta Urban Agglomeration during the 21st century. J. Hazard. Mater.465, 133407 (2023). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Domínguez-Morueco, N. et al. Application of the Multimedia Urban Model to estimate the emissions and environmental fate of PAHs in Tarragona County, Catalonia, Spain. Sci. Total Environ.573, 1622–1629 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ma, X. et al. Sediment records and multi-media transfer and fate of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in Dianchi Lake over the past 100 years. Ecol. Indic.160, 111774 (2024). [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ailijiang, N. et al. Levels, source apportionment, and risk assessment of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in vegetable bases of northwest China. Environ. Geochem. Health. 45, 2549–2565 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cui, X. et al. Pollution levels, sources and risk assessment of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in farmland soil and crops near Urumqi Industrial Park, Xinjiang, China. Stoch. Environ. Res. Risk Assess.37, 361–374 (2022). [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ailijiang, N. et al. Levels, sources, and risk assessment of PAHs residues in soil and plants in urban parks of Northwest China. Sci. Rep.12, 21448 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Fan et al. Pollution characteristics and risk Assessment of Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons in Farmland Soil and crops in the suburbs of Urumqi. Environ. Sci.44, 4039–4051 (2023). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Das, B. et al. Emission factors and emission inventory of diesel vehicles in Nepal. Sci. Total Environ.812, 152539 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Arhonditsis, G. B. et al. What has been accomplished twenty years after the Oreskes. critique? Current state and future perspectives of environmental modeling in the Great Lakes. J. Gt. Lakes Res.40, 1–7 (2014). (1994).

- 35.Sun, C., Wang, X. & Qiao, X. Multimedia fate simulation of mercury in a coastal urban area based on the fugacity/aquivalence method. Sci. Total Environ.915, 170084 (2024). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Singh, B., Sihag, P. & Singh, K. Comparison of infiltration models in NIT Kurukshetra campus. Appl. Water Sci.8, 63 (2018). [Google Scholar]

- 37.Norouzi, R., Sihag, P., Daneshfaraz, R., Abraham, J. & Hasannia, V. Predicting relative energy dissipation for vertical drops equipped with a horizontal screen using soft computing techniques. Water Supply. 21, 4493–4513 (2021). [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wu, Y. et al. Multimedia fate of sulfamethoxazole (SMX) in a water-scarce city by coupling fugacity model and HYDRUS-1D model. Sci. Total Environ.881, 163331 (2023). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Li, Y. F., Qin, M., Yang, P. F., Hao, S. & Macdonald, R. W. Particle/gas partitioning for semi-volatile organic compounds (SVOCs) in level III multimedia fugacity models: gaseous emissions. Sci. Total Environ.795, 148729 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Li, M. et al. Geochemical characteristics and behaviors of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) in soil, water, and sediment near a typical nonferrous smelter. J. Soils Sediments. 23, 2258–2272 (2023). [Google Scholar]

- 41.Singh, B. P., Kumar, K. & Jain, V. K. Distribution of ring PAHs in particulate/gaseous phase in the urban city of Delhi, India: seasonal variation and cancer risk assessment. Urban Clim.40, 101010 (2021). [Google Scholar]

- 42.Thakur, S. S. et al. Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon (PAH)–Contaminated soil decontamination through Vermiremediation. Water Air Soil. Pollut. 234, 247 (2023). [Google Scholar]

- 43.Nguyen, V. H. et al. Tailored photocatalysts and revealed reaction pathways for photodegradation of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) in water, soil and other sources. Chemosphere.260, 127529 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Zhu, S., Wu, K., Mac Kinnon, M., Wu, J. & Samuelsen, S. Modeling polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) concentrations from wildfires in California. Agric. Meteorol.352, 110043 (2024). [Google Scholar]

- 45.Zhen, Z. et al. Assessment of factors affecting the diurnal variations of atmospheric PAHs based on a numerical simulation. Sci. Total Environ.855, 158975 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wang, C., Zhou, S., Song, J., Tang, J. & Wu, S. Formation mechanism of soil PAH distribution: high and low urbanization. Geoderma.367, 114271 (2020). [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wang, Y. et al. Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) in soils and vegetation near an e-waste recycling site in South China: concentration, distribution, source, and risk assessment. Sci. Total Environ.439, 187–193 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Tarigholizadeh, S. et al. Transfer and degradation of PAHs in the soil–plant system: a review. J. Agric. Food Chem.72, 46–64 (2023). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wei, R. et al. Characteristics and biodegradation of Nonextractable Residues of Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons in historically polluted soils. Water Air Soil. Pollut.235, (2024).

- 50.Zhang, M. et al. Distribution, sources, and risk assessment of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) in surface sediments of the Subei Shoal, China. Mar. Pollut Bull.149, 110640 (2019). [Google Scholar]

- 51.Eagar, J. D., Ervens, B. & Herckes, P. Impact of partitioning and oxidative processing of PAH in fogs and clouds on atmospheric lifetimes of PAH. Atmos. Environ.160, 132–141 (2017). [Google Scholar]

- 52.Lu, C. et al. A PAH-degrading bacterial community enriched with contaminated agricultural soil and its utility for microbial bioremediation. Environ. Pollut. 251, 773–782 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Yan, Z. et al. Biodegradation potential of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in Taihu Lake sediments. Environ. Technol.43, 4554–4562 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Mu, J., Leng, Q., Yang, G. & Zhu, B. Anaerobic degradation of high-concentration polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) in seawater sediments. Mar. Pollut Bull.167, 112294 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Imam, A., Kumar Suman, S., Kanaujia, P. K. & Ray, A. Biological machinery for polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons degradation: a review. Bioresour Technol.343, 126121 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Lu, C. et al. Bacterial community and PAH-degrading genes in paddy soil and rice grain from PAH-contaminated area. Appl. Soil. Ecol.158, 103789 (2021). [Google Scholar]

- 57.Wu, D. et al. Atmospheric concentrations and Air-Soil Exchange of Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons (PAHs) in typical urban-rural fringe of Wuhan-Ezhou Region, Central China. Bull. Environ. Contam. Toxicol.104, 96–106 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Sauret, N., Dugué, L., Poulidor, J., Massi, L. & Ledauphin, J. Air Mapping of Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons and their uptake by crops in the Urban Area of Nice, France. Chempluschem. 87, 202200182 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Marquès, M. et al. Climate change impact on the PAH photodegradation in soils: characterization and metabolites identification. Environ. Int.89–90, 155–165 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Schneckenburger, T. & Thiele-Bruhn, S. Sorption of PAHs and PAH derivatives in peat soil is affected by prehydration status: the role of SOM and sorbate properties. J. Soils Sediments. 20, 3644–3655 (2020). [Google Scholar]

- 61.Diagboya, P. N., Mtunzi, F. M. & Adebowale, K. O. Olu-Owolabi, B. I. Assessment of the effects of soil organic matter and iron oxides on the individual sorption of two polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons. Environ. Earth Sci.80, 227 (2021). [Google Scholar]

- 62.Zhou, W. W., Li, J., Hu, J. & Zhu, Z. Z. Distribution, sources, and Ecological Risk Assessment of Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons (PAHs) in soils of the Central and Eastern Areas of the Qinghai-Tibetan Plateau. Huanjing Kexue. 10.13227/j.hjkx.201707207 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Yao, C. et al. Contents,sources,and Ecological Risk Assessment of Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons (PAHs) in Surface soils of various functional zones in Yangzhou City, China. Huanjing Kexue. 10.13227/j.hjkx.201909065 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The authors declare that the data supporting the findings of this study are available within the paper and its Supplementary Information files. Should any raw data files be needed in another format they are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request. Data will be made available from the corresponding author on reasonable request of reader.