Abstract

Objectives

This study focuses on the preventive and therapeutic effects of Dihydroartemisinin (DHA) on Alzheimer’s disease (AD) model mice and the effects of DHA and donepezil on amyloid β-protein deposition and autophagy in nerve cells.

Methods

Six autophagy related targets were selected for molecular docking with DHA to predict the affinity between DHA and the target. The AD mouse model was established and treated with donepezil and DHA, respectively. Morris water maze was used to detect the spatial learning and memory ability of AD mice. Hematoxylin eosin (he) staining was used to observe the structural changes of cerebral cortical neurons and retina, and transmission electron microscope was used to observe the structural changes of mitochondria and synapses. Immunohistochemistry (IHC) and immunofluorescence staining were used to detect the deposition of amyloid beta protein. Western blot was used to detect the expression of apoptosis and autophagy related proteins in the brain tissue of mice in each group.

Results

The results of molecular docking showed that the selected active compounds had good binding activity with the target. The binding energy between DHA and Aβ, Bcl-2, ATG5, LC3, Caspase3, LAMP1 is −5.7, −7.0, −5.8, −7.2, −6.9 kcal/mol. The water maze test showed that compared with the wild type (WT) group, the spatial memory ability of AD model group mice (5× FAD) was significantly decreased, and the search time (27.62 ± 6.51 s vs. 282.80 ± 17.15 s) and average path (106.30 ± 29.65 cm vs. 993.20 ± 135.80 cm) were significantly prolonged. The application of donepezil and DHA significantly shortened the exploration time and average path (donepezil: 116.10 ± 10.58 s, 529.40 ± 106.00 cm; DHA: 99.71 ± 14.22 s, 373.30 ± 60.97 cm). The path to find the platform in DHA treatment group was shorter than donepezil treatment group (P < 0.05). HE staining showed that the arrangement of nerve cells in 5× FAD mice was disordered, and IHC showed that amyloid β-protein deposition was obvious. DHA and donepezil could improve the damage of cerebral cortex structure and reduce the deposition of extracellular amyloid β-protein in AD mice. Transmission electron microscopy showed that DHA and donepezil could reduce mitochondrial vacuolation and synaptic edema. The above results showed that DHA treatment effect was better than donepezil. Compared with the conventional feeding group, autophagy and apoptosis related proteins B-cell lymphoma-2 (BCL2) and anti-thymocyte globulin (ATG) were significantly down regulated in the 5× FAD group, and the expressions of BCL2 and ATG were increased after treatment with DHA and donepezil.

Conclusions

DHA combined with BCL2 and ATG protein, through promoting autophagy protein, can reduce the damage of cerebral cortex structure in AD mice, reduce the deposition of extracellular β-amyloid protein, and then improve the memory ability of AD model mice. DHA treatment is superior to donepezil monotherapy.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s40001-025-02315-x.

Keywords: Alzheimer’s disease, Age-related macular degeneration, Dihydroartemisinin, Amyloid β-protein deposition

Introduction

Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is a degenerative disease of the central nervous system that seriously endangers the physical and mental health of the elderly. The main pathological changes of AD include senile plaques formed by amyloid β-protein deposition, over phosphorylation of Tau protein, neurofibrillary tangles, neuronal apoptosis, and inflammatory response [1, 2]. Age-related macular degeneration (AMD) is one of the important age-related blindness eye diseases. The main pathological change of AMD is the abnormal metabolism of retinal pigment epithelial cells to form colloidal or transparent vitreous warts, the main component of which is Aβ [3]. AD and AMD have co-pathological changes, such as Aβ deposition, oxidative stress, inflammatory response and complement activation [4]. Similarity of pathological deposits found in retina and brain of patients with AD and AMD [5]. Elevated retinal Aβ levels are associated with progressive retinal neurodegeneration, increased brain Aβ accumulation, and increased disease severity associated with cognitive and visual impairment [6]. Large sample data analysis showed that there was a significant pleiotropy between AD and AMD, and APOC1 and apoE were identified as pleiotropic genes of AD–AMD [7]. The onset of AD is insidious, and there is a lack of specific diagnostic means in clinic. Patients are often in the middle and late stages when diagnosed, and the opportunity for early intervention is lost.

At present, the treatment of AD is mostly symptomatic. Donepezil is a conventional first-line drug for the treatment of mild to moderate AD, and its main mechanism is to inhibit the activity of acetylcholinesterase and reduce the neurotoxicity of Aβ, thereby improving clinical manifestations, such as memory loss and emotional disorders in AD patients [8]. However, donepezil has a long onset period, and long-term oral administration is prone to induce gastrointestinal adverse reactions and abnormal renal function [9], and patients often have difficulty in taking it for a long time. Research on the pathogenesis of AD has important clinical application value. Recent studies have shown that growth differentiation factor 11 (Gdf11) is one of the proteins that lead to the deterioration of AD through the treatment of recombinant Gdf11 (rgdf11), it can enhance the proliferation rate of neural precursor cells and angiogenesis, and improve the prognosis of AD patients [10]. Dihydroartemisinin (DHA) is a derivative of artemisinin, which has low toxicity and rapid action, and has the pharmacological effect of inducing autophagy in vivo [11]. Autophagy plays an important role in removing damaged cells or organelles and long-lived protein aggregates [12]. Studies have shown that autophagy disorder is the important mechanism of Aβ overaccumulation, which can reduce the progression of AD and AMD by inducing autophagy [13]. In the neurons of patients with Alzheimer’s disease, when Aβ was accumulated, mitochondria were damaged, and seriously damaged mitochondria were coated by autophagosome and cleared by selective mitochondrial autophagy. When this function was blocked, there were significant dysfunction in neurons, such as mitochondrial transport and dynamics abnormalities, leading to the aggravation of pathological changes of Alzheimer’s disease [14]. In addition, autophagy plays a key role in the function of retinal pigment epithelial cells (RPE) [15]. In the early stage of AMD, the level of autophagy increased to compensate for damaged organelles and oxidative stress. In human AMD samples and mice AMD models, the levels of microtubule-associated protein 1 light chain 3 (LC3), ATG9 and ATG 7 in RPE and retinal layer increased. However, in the samples from advanced AMD, the levels of LC3, ATG 9 and ATG 7 decreased, and the decreased autophagy activity led to the deterioration of AMD [16]. The latest research shows that, the risk of AMD is slightly reduced after receiving Achei instead of AD [17].

To verify the therapeutic effect of DHA on AD and AMD, we will study the effects of DHA and donepezil on the relief of neurological symptoms and pathophysiological changes of AD and AMD through AD model mice experiment, so as to provide a theoretical basis for the research and development of new DHA related therapeutic schemes for AD and AMD.

Materials and methods

Molecular docking

DHA were docked with the 6 targets associated with autophagy (Aβ, Bcl-2, ATG5, LC3, Caspase3 and LAMP1) by molecular docking. ChemDraw software (Version 19.0, USA) was used to draw the DHA structures, which were transformed into 3D structures using the CS Chem3D model. The 3D structure of the predicted targets was found in the Protein Data Bank (PDB) (https://www.rcsb.org/). Prior to docking analysis, water was removed from the predicted targets and hydrogen was added to it and the predicted targets were selected as receptors; hydrogen was added to DHA and it was selected as ligands using the Auto Dock Tools software (Version 1.5.6., USA). Autodock Vina (Version 1.1.2, USA) was used for docking, while Discovery Studio (Version 3.5, USA) and PyMol software (Version 2.1, USA) were used to visualize the docking results. Mol2 files of DHA was downloaded from the TCMSP Database. The docking parameters were shown in supplementary information D1. Docking was accomplished under the autodock4 program, and six different modes of confirmation were generated with their respective binding energy. The best form of docking with the receptors was obtained according to the level of the binding energy. The hydrogen bonds were identified using Discovery Studio, as were the various interactions between the molecules and receptors, including hydrophobic, hydrophilic, electrostatic, van der Waals, and coordination interactions. Refer to molecular docking and structure based drug design strategies for analysis methods [18, 19].

AD animal model and grouping

5× FAD model mice (n = 15) and wild-type mice (WT) (n = 5) were purchased from Jackson’s laboratory, and all mice were female. 5× FAD mice have a large amount of β-amyloid protein in the brain, which can quickly reproduce the main features of Alzheimer’s disease amyloid lesions, such as amyloid plaque aggregation, neuron loss, glial cell proliferation, etc., which is similar to the pathological process of human Alzheimer’s disease [20]. The model mice of the same sex were selected, and the differences caused by hormone effects were excluded, making the results more comparable. The model mice were divided into the conventional feeding group (n = 5), the donepezil treatment group (n = 5) and the DHA treatment group (n = 5). After feeding for 3 months, the mice were euthanized by isoflurane mask inhalation anesthesia with fresh gas flow of 4 L/min and isoflurane concentration of 2%. In the drug treatment group, the dose was 0.1 mg/kg/day in the donepezil treatment group and 20 mg/kg/day in the DHA treatment group, and gastric administration was given. This study was reviewed by the ethics committee, and the research process met the requirements of animal ethical welfare protection.

| Mice type | Cage number | Number of mice | Feeding mode |

|---|---|---|---|

| WT | 01 | 5 | Normal diet |

| WT | 02 | 5 | Normal diet |

| WT | 03 | 5 | Normal diet |

| 5× FAD | 04 | 5 | Normal diet |

| 5× FAD | 05 | 5 | Donepezil |

| 5× FAD | 06 | 5 | DHA |

Morris water maze

The water temperature shall be controlled at 25 ± 1 °C. Four marks of different shapes are evenly distributed on the wall of the pool for comparison and memory. Therefore, the pool is divided into four quadrants, and P, 0, R, and I represent the platform quadrant, the opposite quadrant relative to the platform quadrant, the right quadrant, and the left quadrant, respectively. A circular platform with a diameter of 10 cm and a height of 29 cm is placed in the middle of the platform quadrant, which is made of transparent Plexiglas and has horizontal lines on the surface. Select any point in the other three quadrants to face the wall of the pool and put the rat into the water. Record the time from entering the water to finding the platform hidden under the water and climbing on the platform, that is, the escape latency. On the first day, the rats were allowed to swim freely twice for 2 min each time to adapt to the water environment. From the second day, the water maze training was conducted once in the morning and in the afternoon, respectively, for three consecutive days, a total of six times. The training time of each mouse is 2 min each time. If the platform is not found within 2 min, it is calculated as 2 min. After each training, the mouse is placed on the platform for 15 s to strengthen memory. After training, the average escape latency of rats was recorded. After the positioning navigation experiment, i.e., the fourth day, the platform was removed, and the rats were put into the water from the same water entry point to test the memory of the original platform. Record the time of the first arrival at the original platform and the swimming time in the quadrant of the original platform [21]. All the experimental groups used the same number of training times to exclude the effect of any learning curve observed during the training on the results.

HE staining

The brain and eyeballs of the mice were taken and placed in 4% formalin solution for tissue fixation. The tissue specimens were embedded in paraffin and made into wax blocks. The German Leica tissue slicer was used for paraffin section, with a thickness of 4 μm. The slices were dewaxed in xylene, hydrated with gradient ethanol (100%, 95%, and 75%), washed with distilled water, stained with hematoxylin, slightly rinsed with tap water, differentiated with 1% hydrochloric acid ethanol, re-stained with eosin after washing, dehydrated with alcohol and transparent xylene, and then dried naturally [22]. Pathologists interpret the results under the light microscope.

Transmission electron microscope scanning (TEM)

The ultrastructure was observed by transmission electron microscope. The fixed specimens were treated with 0.075 mol/l Tris, and then washed with hydrochloric acid. After washing, 1% osmic acid was used to fix the sections, and the sections were dehydrated with gradient ethanol. After dehydration, the embedded agent was soaked, gradient soaked, respectively, with acetone and embedding agent 3:1, 1:1, and 1:3 for several hours, and finally soaked with pure embedding agent overnight. The ultrathin section machine was used for methylene blue and fuchsin staining after sectioning. After observation and positioning, the ultrathin section was made with a thickness of 50 nm, double stained with uranium and lead, and observed by transmission electron microscope (jem-2100f, Hitachi, Japan).

Immunohistochemical staining (IHC)

The slices were soaked in xylene solution for 20 min for dewaxing, and then soaked in gradient alcohol (100%, 95%, and 75%) for 5 min for hydration. The slices were soaked in EDTA solution with pH = 9.0 and heated in a pressure cooker for 5 min after venting. Added 100 μl H2O2 solution dropwise and react at room temperature for 20 min. Added 100 μl of 1:200 diluted Aβ primary antibody dropwise(dilutions1:2000, Article No 803014, Biolegend, USA), place it in a 4 °C constant temperature refrigerator overnight, and rinse it with PBS buffer three times the next day. Added PV-9000 (PV-9000, ZSGB-BIO, China) enhancer dropwise and react at room temperature for 25 min. Added 100 μl of horseradish peroxidase labeled Ig polymer (PV-9000, ZSGB-BIO, China) for 20 min at room temperature, and rinse with PBS buffer for 3 times. Added the prepared DAB and H2O2 solution (1:50) dropwise, and control the color depth under the microscope. After dyeing with hematoxylin dye solution for 2 min, rinse with tap water, dry and seal with neutral gum [23].

Immunofluorescence staining

Immerse the paraffin section in a 0.1 mol/l citric acid solution with a pH of 6, heat it in the microwave oven for 6 min until it boils slightly, and then maintain it for 10 min with medium and low fire power, and then cool it naturally for 20–30 min after stopping heating. Wash with PBS for 2 min twice, plus 0.2% TritonX-100 permeable membrane for 15 min, the samples were washed twice in PBS for a duration of 2 min each. Wipe off the PBS outside the specimen with filter paper, add blocking serum dropwise, and block for 1 h at room temperature in a wet box. After PBS cleaning, add an appropriate concentration of Aβ primary antibody (dilutions1:2000, Article No 803014, Biolegend, USA) and incubate overnight at 4 °C in a wet box. PBS washes off the primary antibody, dropwise adds fluorescent secondary antibody (GB27301, 1:500, Servicebio, China) in a humid box at room temperature and incubates for 1 h PBS to wash off the secondary antibody, and incubate dropwise with DAPI protected from light for 15 min. PBS washes away DAPI. With a seal containing an anti-fluorescent quenching agent, observe under a fluorescence microscope and take pictures.

Western blot

The total proteins of brain tissue and retina were extracted and determined by Bicinchoninic acid (BCA) method [24]. After electrophoresis and electroporation, the protein was transferred to polyvinylidene difluoride (PVDF) membrane, and the non-specific antibody was blocked with blocking solution, and then the first antibody was incubated. Proteins of interest include Aβ (803014, 1:5000, Biolegend, USA), Caspase-3 (dilutions 1:1000, Article No 19677-1-AP, Proteintech, China), BCL-2 (dilutions 1:5000, Article No 12789-1-AP, Proteintech, China), ATG5 (dilutions 1:1000, Article No 10181-2-AP, Proteintech, China), LAMP1 (dilutions 1:2000, Article No 21997-2-AP, Proteintech, China), LC3 (dilutions 1:2000, Article No 14600-1-AP, Proteintech, China), GAPDH as internal reference (dilutions 1:1000, Article No 5174S, CST, USA)The primary antibody was incubated overnight at 4 °C, and the secondary antibody (dilutions 1:1000; Article No 7076S/7074S, Cell Signaling Technology, USA) was incubated the next day. Enhanced chemiluminescence (ECL) method color development, acquisition of pictures and semi-quantitative data.

Statistical analysis

The experimental data were all represented by mean ± standard deviation. SPSS software (Version 21.0, USA) was used for statistical analysis of the data, and the normality test and homogeneity test of variance were conducted for all the data. The measurement data were compared among multiple groups by one-way ANOVA, and the unpaired T test was used for comparison between the two groups. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Data mapping was performed using GraphPad Prism software (Version8.0, USA).

Results

Molecular docking analysis

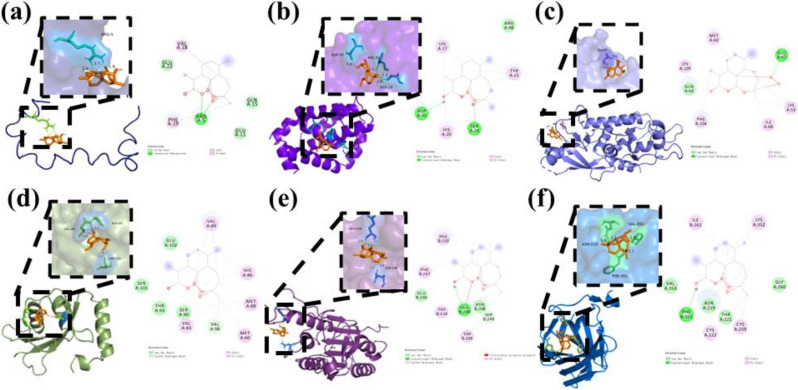

Molecular docking was used to analyze the interaction between DHA and the predicted targets (Aβ, Bcl-2, ATG5, LC3, Caspase3 and LAMP1). The lower the binding free energy of molecular docking, the more stable the binding of ligand and receptor, and the greater the possibility of interaction. When the binding energy is less than 0 kcal/mol, it indicates that the ligand has binding potential with the receptor. When the binding energy is less than −5 kcal/mol, it indicates that the ligand binds to the receptor stably. Among these combinations, the docking results showed that all of them could interact with the receptors. The binding energies are provided in Table 1. All of them is less than −5 kcal/mol. The above results fully indicate that the key components are closely bound to the core target, have high biological affinity, and have high pharmacodynamic activity. The results suggest that DHA may regulate Alzheimer’s disease by acting on Aβ, Bcl-2, ATG5, LC3, Caspase3 and LAMP (Fig. 1).

Table 1.

Binding energy of DHA and receptor

| Ligand | Receptor | Binding energy (kcal/mol) |

|---|---|---|

| DHA | Aβ | −5.7 |

| DHA | Bcl-2 | −7.0 |

| DHA | ATG5 | −5.8 |

| DHA | LC3 | −7.2 |

| DHA | Caspase3 | −6.9 |

| DHA | LAMP1 | −7.6 |

Fig. 1.

Best posture for combinations with binding energy less than −5 kal/mol. Ligands are represented in the green stick model and the receptor residues are represented in the gray stick model. Hydrogen bond interactions are represented as green dotted lines. Pi-alkyl interactions are represented as pink dotted lines. Pi-alkyl interactions are represented as orange dotted lines. Pi-sigma interactions are represented as purple dotted lines. a Aβ-DHA, b Bcl-2-DHA, c ATG5-DHA, d LC3-DHA, e Caspase3-DHA and f LAMP–DHA

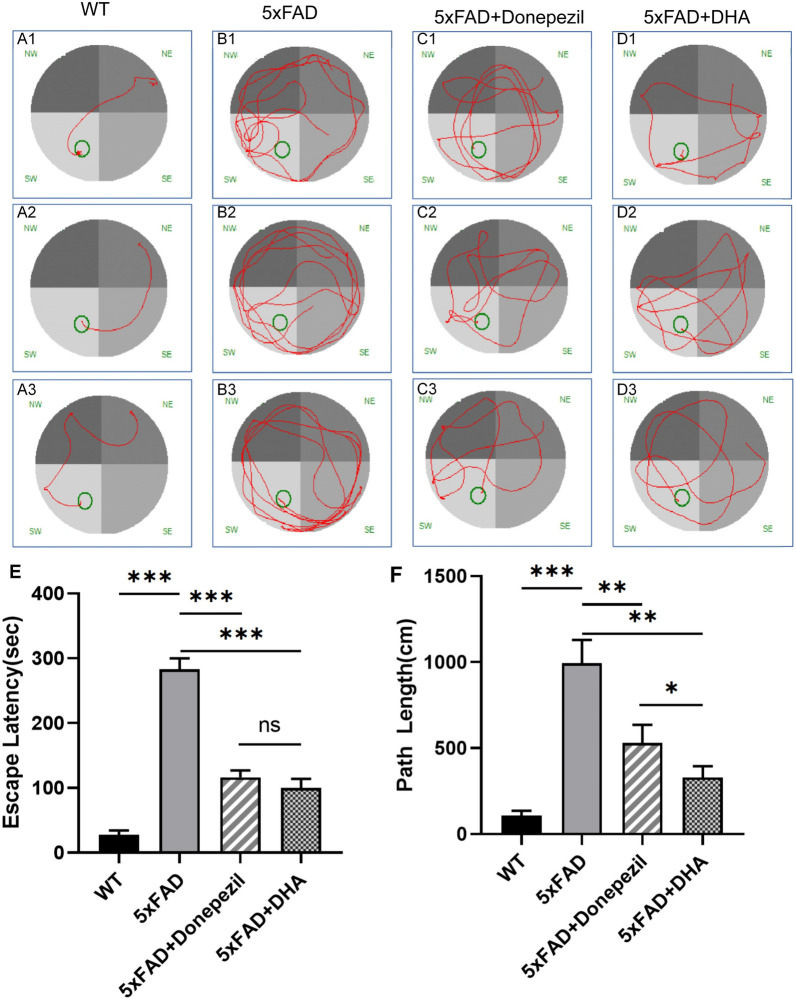

DHA and donepezil can improve the learning and memory ability of 5× FAD mice

Morris water maze experiment was used to determine the effects of donepezil and DHA on spatial learning and memory in AD mice. After 30 days of donepezil or DHA treatment, 5× FAD mice were trained in water maze learning for 3 days, and the time and distance to find the hidden platform were recorded (Fig. 2). The results showed that the searching time of mice in WT group was 27.62 ± 6.51 s, and the average path was 106.30 ± 29.65 cm. The searching time of mice in the model group was 282.80 ± 17.15 s, and the average path was 993.20 ± 135.80 cm. The searching time and distance of mice in the model group were significantly increased, indicating that the spatial learning and memory ability of mice decreased, and the modeling was successful. After donepezil treatment, the platform finding time of mice was 116.10 ± 10.58 s, and the average path was 529.40 ± 106.00 cm. In the DHA treatment group, the search time was 99.71 ± 14.22 s and the average path was 373.30 ± 60.97 cm. Compared with the treatment group, Donepezil treatment and DHA reduced the time (Donepezil P value = 0.0001, DHA P value = 0.0001) and distance (P-donepezil = 0.0096, P-DHA = 0.0016) of 5× FAD mice to find the platform, and the differences were statistically significant. Compared with the donepezil treatment group, the DHA treatment group had a shorter path to find the platform (P = 0.0491).

Fig. 2.

Morris water maze tested the spatial learning and memory abilities of mice. A–D Each group of mice looked for the platform circuit diagram. Routine feeding 5× FAD compared with WT mice, the route of FAD mice was disordered, and donepezil and DHA treatment improved 5× FAD mice route. E Path length of mice in each group to find the platform was analyzed. Routine feeding 5× FAD compared with WT mice, FAD mice’s cost path was significantly increased, and donepezil and DHA treatment improved 5× FAD mouse route. F Analysis of the time spent by each group of mice looking for the platform. Routine feeding 5× FAD compared with WT mice, the time spent in 5× FAD mice was significantly increased, and donepezil and DHA treatment decreased by 5× FAD mice take more time, and DHA is more effective than donepezil

DHA and donepezil improved brain nerve damage in 5× FAD mice

After the behavioral experiment, the mice were euthanized, and the cerebral cortex were removed for morphological studies.

HE staining of cerebral cortex showed that the nerve cells of WT mice were orderly and round, with complete cell structure, clear cell membrane and nucleus, and no obvious swelling and necrosis. In the model group, the arrangement of nerve cells was disordered, the size and shape were irregular, and there were extensive vacuoles and eosinophil structures. Hippocampal pyramidal cells showed granular vacuolar degeneration. Compared with the model group, donepezil and DHA treatment improved 5× FAD mice, the arrangement of nerve cells, vacuoles and other nerve cell damage were reduced, and microglial nodules were reduced (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

HE staining detects structural changes in the cerebral cortex and Hippocampus structure. Compared with WT mice, 5× FAD mice with conventional feeding had structural disorders, and donepezil improved the cortical and Hippocampus structure of 5× FAD with DHA treatment. A1–A3 WT group; B1–B3 arrangement of neurons in the brain and hippocampus was disordered in the 5× FAD group, C1–C3 and D1–D3 after treatment with donepezil or DHA, the disorder of nerve cell arrangement in the cerebral cortex and hippocampus was alleviated compared with the 5× FAD group

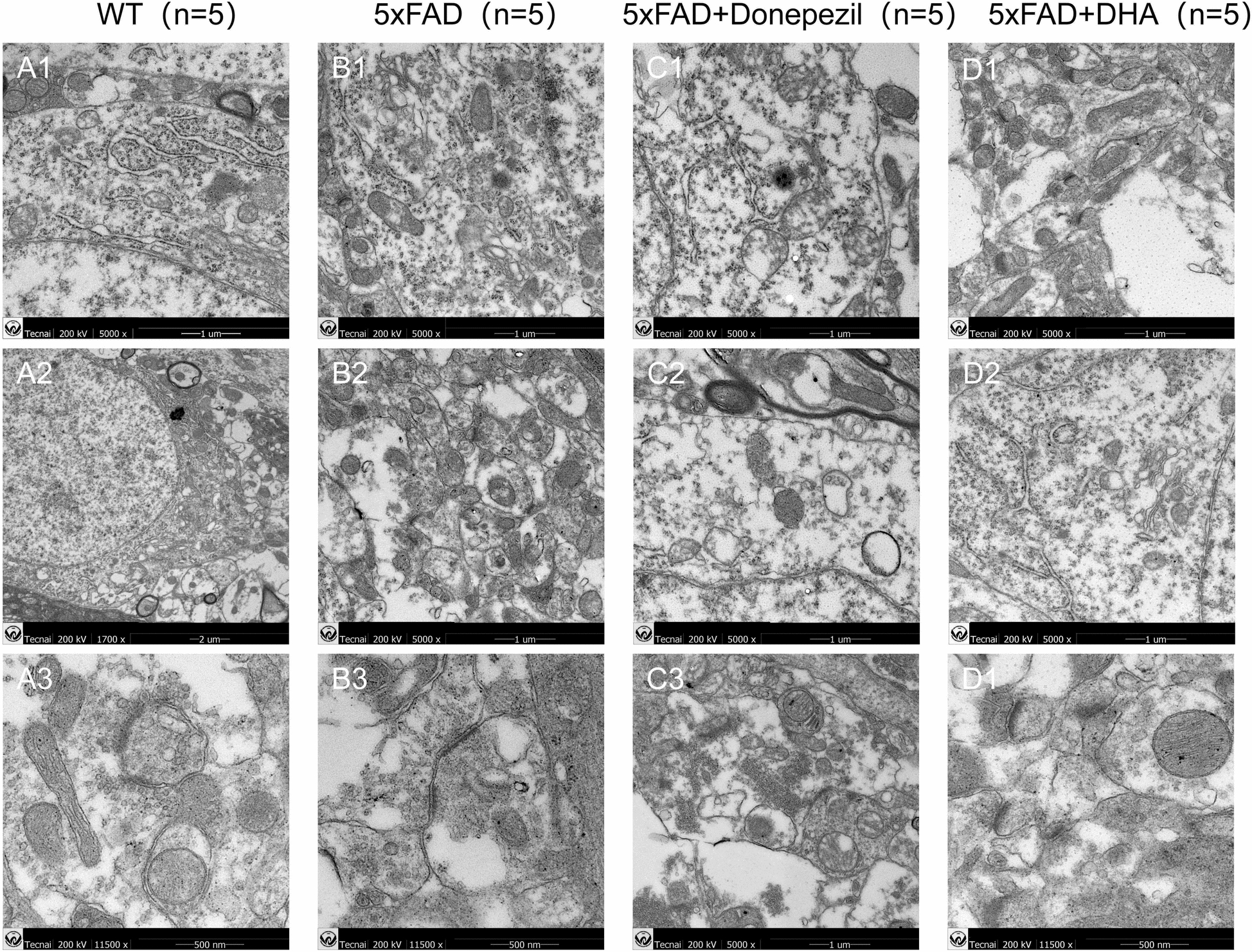

DHA and donepezil improved mitochondrial and synaptic structure in 5× FAD mice

Mitochondrial and synaptic damage is the main pathological basis for cognitive impairment in AD. Compared with WT mice, 5× FAD mice had significant mitochondrial vacuolation, and mitochondrial crest dilation. The synaptic structure of hippocampal neurons is edematous, synaptic vesicles are severely damaged, and the postsynaptic membrane and synaptic cleft are blurred and melted. After treatment with donepezil and DHA, the mitochondrial swelling of 5× FAD mice is reduced, the morphology is improved, the synapses are repaired, that is, the synaptic structure becomes complete, the presynaptic membrane, postsynaptic membrane and synaptic space are distinguishable (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

Observation of synaptic structure of mitochondria and hippocampal neurons in mice by transmission electron microscope. 5× FAD mice had damage to mitochondrial and synaptic structures, and the structures of the two were improved after treatment with donepezil and DHA. A1–A3 Neurons displayed pristine nuclear and nucleolar structures, along with a well-preserved endoplasmic reticulum. B1–B3 Mitochondria were observed to be swollen, and axons presented with aberrant myelin figures. The microtubular architecture was compromised, with autophagic bodies accumulating in the vicinity of the nucleus, signifying heightened early autophagy. C1–C3 Subcellular structures were abnormal, yet the mitochondria remained relatively intact, encircled by lipid droplets and lipofuscin pigments. D1–D3 More distinct and intact cytoplasmic and nuclear outline, featuring autophagic bodies with a double-membrane structure, indicative of robust early autophagy activity, and mitochondria maintained a more intact form

DHA and donepezil reduce Aβ accumulation in cerebral cortex

Aβ deposition was observed by IHC staining and Immunofluorescence staining, and it was found that 5× FAD mice with regular feeding had Aβ deposition in the cerebral cortex (IHC brown–yellow granules, IF red fluorescence), and after treatment with donepezil and DHA, Aβ deposition was reduced (Fig. 5).

Fig. 5.

Immunohistochemistry and immunofluorescence detection of mouse cerebral cortex Aβ-protein deposition. Compared with the WT group, Aβ-protein deposition (IHC orange–yellow dot, IF red fluorescence signal) was also present in the retina of mice in the 5× FAD group, and Aβ-protein deposition was reduced after treatment with donepezil and DHA. A1–A3 No Aβ-protein expression was detected in the WT group; B1–B3 Aβ protein significantly increased in the 5× FAD group; C1–C3 Aβ-protein expression was decreased in donepezil group; D1–D3 Aβ-protein expression was decreased in DHA group

DHA and donepezil reduce Aβ accumulation in retina

The retinal structure of mice was observed by HE staining. The retinal structure of WT mice was clear and the cell morphology was normal. Retinal pigment epithelium (RPE) of 5× FAD mice showed no obvious vacuoles, relatively regular cell arrangement, and no obvious fibrous membrane edema. IHC staining showed that 5 Aβ deposition in 5× FAD mice. After treatment with donepezil and DHA, Aβ deposition was improved (Fig. 6).

Fig. 6.

HE and Immunohistochemistry staining identifies alterations in retina. Compared with WT mice, 5× FAD mice with conventional feeding had a large number of vacuoles in the RPE layer, fibro membrane edema, donepezil and DHA treatment improved the retinal structure of 5× FAD mice. Aβ-protein deposition (IHC orange–yellow dot) was also present in the retina of mice in the 5× FAD group, and Aβ-protein deposition was reduced after treatment with donepezil and DHA. A1–A3 WT group; B1–B3 5× FAD group; C1–C3 donepezil group; D1–D3 DHA group

Autophagy and apoptosis induced by DHA and donepezil

Western Blot results showed that compared with the control group, autophagy apoptotic protein related proteins were found in the brain tissue of 5× FAD group mice that the expression of BCL2, and ATG5 proteins was significantly down-regulated. Aβ expression was up-regulated. After treatment with donepezil or DHA, the protein expressions of BCL2 and ATG5 increased compared with the model group, Aβ expression was down-regulated. Caspase-3, LAMP1, LC3 didn’t differ significantly in each component. The results showed that donepezil and DHA helped promote autophagy and apoptosis in the brain tissues of 5× FAD mice (Fig. 7).

Fig. 7.

Western blot measured the expression levels of apoptosis and autophagy-related proteins in mice brain tissues. Compared with normal fed 5× FAD mice, the expression levels of β-amyloid, BCL-2 and ATG5 treated with donepezil or DHA were statistically significant (P < 0.05). Compared with normal fed 5× FAD mice, the expression levels of Caspase-3, Lamp1 and LC3 treated with donepezil or DHA were not statistically significant

Discussion

AD is the seventh leading cause of death in the world. The 2021 World AD Report shows: (World Alzheimer Report 2021 | Alzheimer’s Disease International (ADI) (alzint.org)), that only 45% of AD patients receive accurate diagnosis and corresponding support at an early stage, and there are some difficulties in clinical diagnosis of AD, including lack of early clinical symptoms, lack of professional clinicians and high treatment costs. The clinical diagnosis methods of AD mainly include neuroimaging examination, neuropsychological assessment, humoral markers and genetic testing, etc. [25]. Currently, the drugs against AD, include cholinesterase inhibitors, such as Donepezil, Rivastin, and galantamine, which can delay the breakdown of acetylcholine in the synaptic space [26]. Most of these drugs work to relieve symptoms, and there is no effective treatment for AD in present. Marwa elsbaey and other scholars chemically synthesized nine new vanillin 1,2,3-triazole conjugates with Aβ docking fraction of −2.9 to −4.7 kcal/mol [27]. This study shows that the binding energy of DHA to Aβ is −5.7 less than −4.7 kcal/mol, and its direct binding ability to ad core protein is better than existing studies. In addition, the docking results showed that the binding energies of DHA to various autophagy related proteins such as Bcl-2, ATG5, LC3, Caspase3, and LAMP were all less than −5 kcal/mol, with the lowest binding energy observed in the LAMP1–DHA group. DHA and LAMP formed hydrogen bonds through the amino acid residue PHE351. Although a compound can achieve good affinity with its target in vitro, it does not mean that desired effect in vivo can be achieved. Poor pharmacokinetic properties and unacceptable toxicity are the main reasons contributing to an unsuccessful clinical trial of candidate drugs [28]. Studies have shown that DHA has good fat solubility, but poor water solubility, and the low oral bioavailability, which may be a key factor limiting its efficacy [29].

AMD is one of the main causes of vision loss in the elderly worldwide, and its pathogenesis is not completely clear [30]. Studies have shown that the apoptosis of RPE and mitochondrial dysfunction are related to the pathogenesis of AMD [31, 32]. Studies have found that AD patients not only have cognitive impairment, but also have abnormal eye structure and function, including visual field damage, retinal structural changes, and thinning of nerve fiber layer thickness [33, 34]. Koronyo Hamaoui et al. [35] studied the brain tissue and retina of normal elderly people and patients with different degrees of AD and found that Aβ amyloid not only appeared on the retina of AD patients, but also the content in the retina was synchronized with the distribution of brain tissue, which was positively correlated with the severity of the disease. In APP/PS1 double-transgenic AD model mice, Aβ deposition in the retina predates brain tissue [36]. This indicates that AD patients’ Aβ pathological aggregation may first appear in the retina which is of great significance for early screening of potential AD patients. Our model confirms the presence of Aβ deposits in the brain nerve tissue and retina tissue of 5× FAD model mice. The pathophysiological mechanisms of both AMD and AD include Aβ deposition, oxidative stress, inflammatory response, neuronal apoptosis and complement activation. Aβ mainly forms age spots in brain tissue in AD and vitreous warts on the retina of AMD patients, which has toxic effects on the nerves of AD and AMD patients, and can lead to synaptic dysfunction, mitochondrial dysfunction, glial cell activation and vascular abnormalities [37]. Aβ imbalance of generation and clearance and accumulation in retina and brain tissue may be the initial factors that promote the pathogenesis of AMD and AD.

Autophagy is an important degradation and recycling mechanism in cells. It wraps and transports intracellular waste, damaged organelles and proteins to lysosomes for degradation by forming autophagosomes. In AD, autophagy is closely related to the development and pathological changes of the disease. Chaperone mediated autophagy (CMA) is a selective autophagy process, which can transfer proteins with specific motifs to lysosome for degradation. In AD, the inactivation of CMA pathway may lead to the accumulation of Aβ and abnormally phosphorylated tau protein in neurons, thus destroying the normal function of cells and accelerating cell death [38]. Mitochondrial autophagy is the mechanism by which cells clear damaged mitochondria. In AD, if the damaged mitochondria are not cleared in time, it will lead to dysfunction and aggravate pathological changes. Enhancing mitochondrial autophagy may help to inhibit the aggregation of Aβ and microtubule associated proteins, and reverse cognitive deficits in AD model [10]. Autophagy dysfunction may lead to toxic protein aggregation and non-degradation in the brain of patients with AD. This study also found that in 5× FAD model mice, there was a decrease in the expression of autophagy-related proteins in brain nerve tissue. Compared with the model group, the expression of BCL2 and ATG5 proteins was upregulated. Verified that decreased levels of self-indulgence promote the occurrence of Alzheimer’s disease.

In recent years, the potential role of traditional Chinese medicine in the prevention and treatment of AD has attracted researchers’ attention. Artemisinin is a traditional Chinese medicine isolated from Artemisia annua. Clinical studies have shown that artemisinin drugs have high efficacy and low toxicity in the treatment of malaria and other protozoan infections. DHA is a artemisinin derivative, which has a strong and rapid killing effect on plasmodium erythrocytic phase, and can quickly control the clinical attack and symptoms [39]. The main therapeutic mechanisms of artemisinin for malaria include: changing the membrane structure of parasites, preventing the earliest energy uptake, blocking the utilization of amino acids, and activating autophagy. Artemisinin drugs have been gradually used in the treatment of many other diseases, such as some infectious diseases, cancer and inflammation because of their ability to correct autophagy. Some studies have pointed out that the concentration of radiolabeled DHA in rat brain tissue is more than twice as high as that in plasma, suggesting that DHA is easy to penetrate the blood–brain barrier [40]. The study also found that DHA has definite curative effect on some brain diseases (such as experimental cerebral malaria in mice) [41]. At present, artemisinin drugs have been found to have effective neuroprotective effects in AD model, such as anti-neuroinflammation and anti-mitochondrial stress activity [42–44]. We observed the effects of donepezil and DHA on spatial learning and memory in AD mice through the Morris water maze experiment, which is consistent with the conclusion of Zhao [45] and Pellegrini [46]. Treatment with donepezil and DHA shortened the time and distance for 5× FAD mice to find a platform. Compared with the donepezil treatment group, the DHA treatment group had a shorter path to finding the platform.

Furthermore, the observation of HE staining sections of brain showed that DHA could effectively improve 5× FAD arrangement of nerve cells in brain tissue, and reduced Aβ deposition. The curative effect is better than donepezil. Through electron microscopy, it was confirmed that the model group mice exhibited significant mitochondrial vacuolization, hippocampal neuronal synaptic structure edema, and severe damage to synaptic vesicles. After treatment with donepezil and DHA, mitochondrial swelling was reduced, morphology improved, and synaptic repair occurred. IHC staining detected Aβ accumulation, and DHA alleviates accumulation of Aβ. Aβ expression was downregulated after treatment with donepezil or DHA. Donepezil and DHA helped promote autophagy and apoptosis in the brain tissue of 5× FAD mice.

However, we did not observe significant changes in the retinal structure of 5× FAD mice. This result is different from the results of cortical experiments, and the reason may be that the accumulation of Aβ in the retina of 5× FAD mice occurs earlier than structural changes, indicating that drug treatment has a more direct effect on alleviating Alzheimer’s disease in the brain. In summary, we believe that DHA has potential clinical application value in the treatment of AD. Possible treatment for AD by promoting autophagy.

Conclusion

DHA has good curative effect on Alzheimer’s disease model mice with age-related macular degeneration, and can reduce Aβ accumulation, inducing autophagy and apoptosis, thus delaying the development of AD, has great therapeutic value.

Supplementary Information

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Abbreviations

- AD

Alzheimer’s disease

- AMD

Age-related macular degeneration

- APP

Amyloid precursor protein

- Aβ

Amyloid β-protein

- CT

Computed tomography

- DHA

Dihydroartemisinin

- IHC

Immunohistochemical staining

- MRI

Magnetic Resonance imaging

- RPE

Retinal pigment epithelial

- TEM

Transmission electron microscope scanning

Author contributions

Yao Hongbo designed this study. Gao Han conducted the experiments and wrote the manuscript. Gong Xuewu and Zhang Meng and Wang Yuejing and Wang Yuchun and Zhang Keshuang performed the experiments and collected data. All authors approved this manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by Natural Science Foundation of Heilongjiang Province of China (LH2021H122).

Availability of data and materials

No datasets were generated or analysed during the current study. All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article.

Declarations

Ethical approval and consent to participate

Report from animal ethical care committee of Qiqihar medical university (QMU-AECC-2021-75).

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Chen J, Fan A, Li S, et al. APP mediates tau uptake and its overexpression leads to the exacerbated tau pathology. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2023;80(5):123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Guo Y, Fan Z, Zhao S, et al. Brain-targeted lycopene-loaded microemulsion modulates neuroinflammation, oxidative stress, apoptosis and synaptic plasticity in β-amyloid-induced Alzheimer’s disease mice. Neurol Res. 2023;45(8):753–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wang Y, Han S, Chen J, et al. PFKFB3 knockdown attenuates Amyloid β-Induced microglial activation and retinal pigment epithelium disorders in mice. Int Immunopharmacol. 2023;115: 109691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Burgaletto C, Platania CBM, Di Benedetto G, et al. Targeting the miRNA-155/TNFSF10 network restrains inflammatory response in the retina in a mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease. Cell Death Dis. 2021;12(10):905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kaštelan S, Nikuševa-Martić T, Pašalić D, Antunica AG, Zimak DM. Genetic and epigenetic biomarkers linking Alzheimer’s disease and age-related macular degeneration. Int J Mol Sci. 2024;25(13):7271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Too LK, Hunt N, Simunovic MP. The role of inflammation and infection in age-related neurodegenerative diseases: lessons from bacterial meningitis applied to Alzheimer disease and age-related macular degeneration. Front Cell Neurosci. 2021;15: 635486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zhang X, Zhu Z, Huang Y, et al. Shared genetic aetiology of Alzheimer’s disease and age-related macular degeneration by APOC1 and APOE genes. BMJ Neurol Open. 2024;6(1): e000570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Handa JT, Cano M, Wang L, et al. Lipids, oxidized lipids, oxidation-specific epitopes, and age-related macular degeneration. Biochim Biophys Acta Mol Cell Biol Lipids. 2017;1862(4):430–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shadfar S, Parakh S, Jamali MS, et al. Redox dysregulation as a driver for DNA damage and its relationship to neurodegenerative diseases. Transl Neurodegener. 2023;12(1):18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.de Liyis BG, Halim W, Widyadharma IPE. Potential role of recombinant growth differentiation factor 11 in Alzheimer’s disease treatment. Egypt J Neurol Psychiatry Neurosurg. 2022;58:49. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zhang N, Gordon ML. Clinical efficacy and safety of donepezil in the treatment of Alzheimer’s disease in Chinese patients. Clin Interv Aging. 2018;13:1963–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kuang H, Tan CY, Tian HZ, et al. Exploring the bi-directional relationship between autophagy and Alzheimer’s disease. CNS Neurosci Ther. 2020;26(2):155–66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Barfejani AH, Jafarvand M, Seyedsaadat SM, et al. Donepezil in the treatment of ischemic stroke: review and future perspective. Life Sci. 2020;263: 118575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Xie C, Zhuang XX, Niu Z, et al. Amelioration of Alzheimer’s disease pathology by mitophagy inducers identified via machine learning and a cross-species workflow. Nat Biomed Eng. 2022;6(1):76–93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mitter SK, Song C, Qi X, et al. Dysregulated autophagy in the RPE is associated with increased susceptibility to oxidative stress and AMD. Autophagy. 2014;10(11):1989–2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wang AL, Lukas TJ, Yuan M, et al. Autophagy and exosomes in the aged retinal pigment epithelium: possible relevance to drusen formation and age-related macular degeneration. PLoS ONE. 2009;4(1): e4160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sutton SS, Magagnoli J, Cummings TH, Hardin JW, Ambati J. Alzheimer disease treatment with acetylcholinesterase inhibitors and incident age-related macular degeneration. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2024;142(2):108–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ferreira LG, Dos Santos RN, Oliva G, Andricopulo AD. Molecular docking and structure-based drug design strategies. Molecules. 2015;20(7):13384–421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jiao X, Jin X, Ma Y, et al. A comprehensive application: molecular docking and network pharmacology for the prediction of bioactive constituents and elucidation of mechanisms of action in component-based Chinese medicine. Comput Biol Chem. 2021;90: 107402. 10.1016/j.compbiolchem.2020.107402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pádua MS, Guil-Guerrero JL, Lopes PA. Behaviour Hallmarks in Alzheimer’s disease 5× FAD mouse model. Int J Mol Sci. 2024;25(12):6766. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Darcet F, Mendez-David I, Tritschler L, et al. Learning and memory impairments in a neuroendocrine mouse model of anxiety/depression. Front Behav Neurosci. 2014;8:136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yu Z, Cao M, Peng J, et al. Lacticaseibacillus casei T1 attenuates Helicobacter pylori-induced inflammation and gut microbiota disorders in mice. BMC Microbiol. 2023;23(1):39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Deng M, Zhang Z, Liu B, et al. Localization of GPSM2 in the nucleus of invasive breast cancer cells indicates a poor prognosis. Front Oncol. 2020;10:227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sang L, Wu X, Yan T, et al. The m6A RNA methyltransferase METTL3/METTL14 promotes leukemogenesis through the mdm2/p53 pathway in acute myeloid leukemia. J Cancer. 2022;13(3):1019–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Arvanitakis Z, Shah RC, Bennett DA. Diagnosis and management of dementia: review. JAMA. 2019;322(16):1589–99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wang H, Zhang H. Reconsideration of anticholinesterase therapeutic strategies against Alzheimer’s disease. ACS Chem Neurosci. 2019;10(2):852–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Elsbaey M, Igarashi Y, Ibrahim MAA, Elattar E. Click-designed vanilloid-triazole conjugates as dual inhibitors of AChE and Aβ aggregation. RSC Adv. 2023;13(5):2871–83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Honório KM, Moda TL, Andricopulo AD. Pharmacokinetic properties and in silico ADME modeling in drug discovery. Med Chem. 2013;9(2):163–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Watson DJ, Laing L, Gibhard L, et al. Toward new transmission-blocking combination therapies: pharmacokinetics of 10-amino-artemisinins and 11-aza-artemisinin and comparison with dihydroartemisinin and artemether. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2021;65(8): e0099021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Deng Y, Qiao L, Du M, et al. Age-related macular degeneration: epidemiology, genetics, pathophysiology, diagnosis, and targeted therapy. Genes Dis. 2022;9(1):62–79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hanus J, Anderson C, Wang S. RPE necroptosis in response to oxidative stress and in AMD. Ageing Res Rev. 2015;24(Pt B):286–98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kaarniranta K, Uusitalo H, Blasiak J, et al. Mechanisms of mitochondrial dysfunction and their impact on age-related macular degeneration. Prog Retin Eye Res. 2020;79: 100858. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hart NJ, Koronyo Y, Black KL, et al. Ocular indicators of Alzheimer’s: exploring disease in the retina. Acta Neuropathol. 2016;132(6):767–87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ashok A, Singh N, Chaudhary S, et al. Retinal degeneration and Alzheimer’s disease: an evolving link. Int J Mol Sci. 2020;21(19):7290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Doustar J, Torbati T, Black KL, Koronyo Y, Koronyo-Hamaoui M. Optical coherence tomography in Alzheimer’s disease and other neurodegenerative diseases. Front Neurol. 2017;8:701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Chintapaludi SR, Uyar A, Jackson HM, et al. Staging Alzheimer’s disease in the brain and retina of B6. APP/PS1 mice by transcriptional profiling. J Alzheimers Dis. 2020;73(4):1421–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Shi H, Koronyo Y, Rentsendorj A, et al. Identification of early pericyte loss and vascular amyloidosis in Alzheimer’s disease retina. Acta Neuropathol. 2020;139(5):813–36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bourdenx M, Martín-Segura A, Scrivo A, et al. Chaperone-mediated autophagy prevents collapse of the neuronal metastable proteome. Cell. 2021;184(10):2696–714.e25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Keating GM. Dihydroartemisinin/Piperaquine: a review of its use in the treatment of uncomplicated Plasmodium falciparum malaria. Drugs. 2012;72(7):937–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Xie LH, Li Q, Zhang J, et al. Pharmacokinetics, tissue distribution and mass balance of radiolabeled dihydroartemisinin in male rats. Malar J. 2009;8:112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Song X, Cheng W, Zhu H, et al. Additive therapy of plasmodium berghei-induced experimental cerebral malaria via dihydroartemisinin combined with rapamycin and atorvastatin. Microbiol Spectr. 2023;11(2): e0231722. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Gao Y, Cui M, Zhong S, et al. Dihydroartemisinin ameliorates LPS-induced neuroinflammation by inhibiting the PI3K/AKT pathway. Metab Brain Dis. 2020;35(4):661–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Guan S, Jin T, Han S, et al. Dihydroartemisinin alleviates morphine-induced neuroinflammation in BV-2 cells. Bioengineered. 2021;12(2):9401–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Qu C, Ma J, Liu X, et al. Dihydroartemisinin exerts anti-tumor activity by inducing mitochondrion and endoplasmic reticulum apoptosis and autophagic cell death in human glioblastoma cells. Front Cell Neurosci. 2017;11:310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Zhao Y, Long Z, Ding Y, et al. Dihydroartemisinin ameliorates learning and memory in Alzheimer’s disease through promoting autophagosome-lysosome fusion and autolysosomal degradation for Aβ clearance. Front Aging Neurosci. 2020;12:47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Pellegrini C, D’antongiovanni V, Fornai M, et al. Donepezil improves vascular function in a mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease. Pharmacol Res Perspect. 2021;9(6): e00871. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

No datasets were generated or analysed during the current study. All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article.