Abstract

Background

Abnormal metabolism is the main hallmark of cancer, and cancer metabolism plays an important role in tumorigenesis, metastasis, and drug resistance. Therefore, studying the changes of tumor metabolic pathways is beneficial to find targets for the treatment of cancer diseases. The success of metabolism-targeted chemotherapy suggests that cancer metabolism research will provide potential new targets for the treatment of malignant tumors.

Purpose

The aim of this study was to systemically review recent research findings on targeted inhibitors of tumor metabolism. In addition, we summarized new insights into tumor metabolic reprogramming and discussed how to guide the exploration of new strategies for cancer-targeted therapy.

Conclusion

Cancer cells have shown various altered metabolic pathways, providing sufficient fuel for their survival. The combination of these pathways is considered to be a more useful method for screening multilateral pathways. Better understanding of the clinical research progress of small molecule inhibitors of potential targets of tumor metabolism will help to explore more effective cancer treatment strategies.

Keywords: Cancer metabolism, Small molecules, Metabolic reprogramming, Drug development, Targeted therapy, Tumor microenvironment

Introduction

As a major public health problem in the world, cancer is the second leading cause of death in the world after cardiovascular diseases. An estimated 10 million deaths occurred worldwide in 2020 (Siegel et al. 2020; Sung et al. 2021). Cancer is one of the major global disease burdens and will become a prominent global health problem (Cao et al. 2021). Cells' inability to cope with stress and repair damage underlies many cancers (Jelic et al. 2021). Despite various cancer treatment strategies, such as chemotherapy, radiotherapy, immunotherapy, and surgery, patients with cancer cannot be fully treated (Zeng 2018). Resistance to previous treatments presents the greatest challenge to the successful treatment of cancer. Currently, the development of highly effective anticancer strategies with few side effects is a top priority. Understanding the disorder of biology and metabolic pathway of cancer can explore new therapeutic targets.

The metabolism of cancer cells is very different from that of normal cells, cancer cells are abnormal cells that can multiply and regenerate rapidly. They are characterized by infinite proliferation, transformation and migration, and can destroy normal cells. In order to meet the needs of cell proliferation and migration, cancer cells obtain molecular substances and energy through unusual metabolic pathways, because their metabolism is more active than that of normal cells. A variety of carcinogenic signaling pathways finally converge to regulate three main metabolic pathways in cancer cells, including glucose, amino acids, and lipid metabolism (Tang et al. 2021). The metabolism of cancer cells is the direct result of the regulation of intracellular signaling pathways, which are destroyed by mutated oncogenes and tumor suppressor genes. Mutated oncogene can directly start cancer cell metabolism. Similarly, mutated metabolic enzymes can promote malignant transformation. Metabolism includes a process of producing energy, in which cells are beneficial to maintaining cell homeostasis, growth, and proliferation (Jang et al. 2013). The unique metabolic characteristics of cancer cells reflect that metabolic changes are indispensable for the occurrence and development of tumor cells. Therefore, targeting the metabolism of cancer cells could have a huge impact on the effectiveness of treatments. Research in recent years has focused on using the metabolic characteristics of tumor cells to distinguish normal cells, uncontrolled unlimited proliferation is an essential feature of tumors (Martinez-Outschoorn et al. 2017; Pavlova et al. 2022). Based on these characteristics, we will find metabolic pathways that are different from those of normal cells, understanding the regulation of cellular metabolism is key to elucidating cancer metabolism as an attractive target for therapeutic development. In particular, we will focus on the typing and precise mechanisms of cancer metabolism, highlighting strategies that may lead to precisely targeted improvements in cancer cell metabolism.

The development of molecular and biochemical techniques has expanded the understanding of changes that occur in specific metabolic pathways in cancer cells. Cancer can reprogram its metabolism to adapt to microenvironment by increasing aerobic glycolysis to maximize ATP production, and increasing glutamine decomposition, lipid and nucleotide metabolism pathways to support bioenergy and biosynthesis during rapid proliferation (Abdel-Wahab et al. 2019; Matés et al. 2020; Broadfield et al. 2021; Hager et al. 2020). Enasidenib and Ivosidenib, selective inhibitors of mutant isocitrate dehydrogenases IDH2 and IDH1, respectively, have been approved for the treatment of R/R AML (Martelli et al. 2020). Inhibitors of glutaminase metabolism, such as CB-839, can be used to control the oncogenicity of triple negative breast cancer (TNBC) (Singleton et al. 2020). TVB-2640 is an oral, potent, and selective reversible first-in-class fatty acid synthase inhibitor (Syed-Abdul et al. 2020). While the exact mechanisms underlying the differing efficacy of existing antimetabolic therapies are unclear, a better understanding of these and other metabolic therapeutic windows may lead to the development of more effective and targeted cancer treatments. Using new biochemical and molecular research tools, the study of cancer cell metabolism deepens our mechanistic and functional understanding of metabolic alterations at various stages of tumorigenesis. A better understanding of tumor metabolism changes and mechanisms will help us explore more effective cancer treatments. In this regard, we provide a concise illustration of the main metabolic pathways for the survival and proliferation of cancer cells, and briefly describe the metabolic pathways of tumor cells from the point of view of nutrition. According to the level of nutritional utilization of cancer cells, we start with glucose, which is the most abundant nutrient in the blood and a major contributor to the cell metabolism and evolution. We continued to study glutamine, which is the second largest nutrient after glucose, and briefly discussed the metabolism of fatty acid and nucleotides. In addition, we also reviewed oxygen as the source of electron acceptor and the role of reactive oxygen species (ROS) in supporting energy generation. Inhibitors of tumor metabolism-related pathways can specifically block the activities of these enzymes and prevent tumor growth and metastasis. We analyzed the latest reports of targeted inhibitors of tumor metabolism and compared the applications of various targeted inhibitors. In this review, we cover the fundamentals of cancer metabolism and focus on small-molecule drug discovery efforts to target cancer.

Aerobic glycolysis and therapeutic targets

Glucose is the main source of energy and the main fuel for cell respiration. In glucose utilization under normal conditions, it is known that 70% of ATP is synthesized by oxidative phosphorylation, and the rest is synthesized by glycolysis. As ATP production varies with cell conditions, the ratio between glycolysis and oxidative phosphorylation also varies with different cells, growth states and microenvironment (Jang et al. 2013). One of the most significant metabolic changes in tumor cells is that even under aerobic conditions, their glycolysis is still abnormally active, which is manifested by massive consumption of glucose and increased secretion of lactate. This phenomenon was first described by the famous German scientist Otto Warburg in 1924. Therefore, later generations called this special glycolysis phenomenon of tumor cells the Warburg effect (Bose et al. 2021), also called aerobic glycolysis. At the molecular level, glucose is transported into tumor cells by glucose transporters and then converted into pyruvate by a series of glycolytic enzymes, which is then catalyzed by lactate dehydrogenase to lactate, and then transported by monocarboxylic acid transporters to the outside of the cell, the consumption of glucose and the secretion of lactic acid are completed, the specific metabolic process is shown in Fig. 1. Aerobic glycolysis plays an important role in tumor progression. High-throughput glycolysis can not only provide energy quickly, but also provide raw materials for the synthesis of various biological macromolecules in tumor cells, because various intermediate metabolites generated in the process of glycolysis are precursors necessary for other metabolic pathways. These intermediate metabolites provide raw materials for biosynthetic pathways such as nucleotides, lipids, amino acids and reduced nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phos phate (NADPH) to meet the material needs of rapid cell proliferation (Vaupel and Multhoff 2021; Ganapathy–Kanniappan, 2018). These metabolic bypass pathways include the pentose phosphate pathway (PPP) for the production of ribonucleic acid and NADPH (Ghanem et al. 2021); Hexosamine pathway, which is used for glycosylation and glycogenogenesis of proteins (Sharma et al. 2020), and Serine biosynthesis pathway, used to produce amino acids, etc. (Geeraerts et al. 2021). Glycolysis plays a central role in cellular metabolic pathways and is the basis of many other metabolic pathways. Therefore, high-throughput glycolysis is compatible with the highly active life activities of tumor cells themselves. In addition, glycolysis also brings other benefits to tumor cells, for example, in the process of aerobic glycolysis in tumor cells, a large amount of pyruvate is converted into lactate without entering the tricarboxylic acid cycle to complete oxidative phosphorylation. On the one hand, it can reduce the production of reactive oxygen species (ROS), thereby Protects mitochondria; on the other hand, long-term maintenance of moderate levels of ROS is beneficial for tumor progression (Moloney and Cotter 2018; Prochownik and Wang 2021). Targeting aerobic glycolysis in tumor cells is a very promising therapeutic strategy. At present, there are many therapeutic targets for tumor glycolysis, mainly including some key enzymes and transporters. Targeting aerobic glycolysis has become a promising chemotherapeutic strategy in the clinic.

Fig. 1.

Tumor cell glycolytic pathway and targeted representative clinical small molecules. Cells take glucose and react to convert it, pyruvic acid has two fates-it enters TCA cycle or is converted into lactic acid. GLUT glucose transporter, HK Hexokinase, PGI glucose phosphate isomerase, PFK1 phosphofructokinase-1, PFKFB3 fructose-2,6-bisphosphatase 3, ALDOA fructose diphosphate aldolase A, TPI triose-phosphate isomerase, PGK1 phosphoglycerate kinase 1, PGM phosphoglycerate mutase, ENO enolase, PK pyruvate kinase, LDHA/B lactate dehydrogenase A/B, MCT monocarboxylic acid transporter

Glucose transporters

There are 14 members of the glucose transporters (GLUT) family, which are usually overexpressed in malignant cells (Ancey et al. 2018). All members can transport hexose and polyols: however, there are still many natural substrates of GLUT that are not clear. At present, only GLUT1 ~ 4 have been studied most deeply, they have the role of glucose and/or fructose transporters in various tissues and cell types (Holman 2020). GLUT1 is the most widely distributed glucose transporter, and its expression is regulated by HIF-1α (Holman 2020). In most tumors, hypoxic tumor microenvironment induces high expression of GLUT1 and improves the ability of tumor cells to absorb glucose, which is also the basis for tumor cells to produce Warburg effect.

Ritonavir, an HIV protease inhibitor, has a pan inhibitory effect on GLUT1/3/4 and is found to be beneficial when used in combination (Hresko and Hruz 2011). The efficacy of Ritonavir in patients with advanced or recurrent high-grade glioma was evaluated in an open phase II trial (Ahluwalia et al. 2018). Ritonavir is well tolerated in refractory HGG patients who have received severe pretreatment, and there is no grade 3 or 4 toxicity. However, the activity under the dosage and regimen used in this study is moderate, and this study has not reached the end point of its efficacy, which needs further clinical trials to verify. Recently, several small molecule inhibitors of GLUT have been found to exert antitumor activity by targeting GLUT to inhibit glycolysis, including BAY-876, STF-31 and WZB117, and have shown promising results in anticancer therapy. BAY-876 is an effective antagonist of glucose transporter type 1 (GLUT1) receptor and has strong inhibitory activity against GLUT1. In cell-free system, IC50 value is as low as 2 nmol/L (Siebeneicher et al. 2016), yet the clinical application of BAY-876 still faces many challenges. First of all, most HCC patients in China suffer from intolerable cirrhosis, and their gastrointestinal function is insufficient/damaged, which leads to poor oral drug absorption (Roca Suarez et al. 2021). Second, oral or intravenous infusion as a route of administration will lead to drug distribution throughout the body, which will not only interfere with the physical uptake of glucose by the human body, but also lead to negligible dosage of BAY-876 at the lesion site of HCC (Wang et al. 2021). In 2021, a study described a new microcrystalline BAY-876 formula to establish a long-acting sustained release preparation of BAY-876, so as to achieve precise dose administration, and play a targeted anti-tumor activity on liver cancer lesions without affecting normal tissues and organs, thus reducing the occurrence of potential side effects, and providing additional options for the treatment of advanced liver cancer (Yang et al. 2021). Polyphenol compound WZB117 is a synthetic small-molecule GLUT1 inhibitor, which has been proved to have anti-cancer activity against a variety of solid tumors, including non-small cell lung cancer, colon cancer and KRAS mutant cancer, providing a promising choice for further development of anti-cancer therapy (Shima et al. 2022). STF-31 is a small-molecule inhibitor of GLUT1 that has been proved to have anti-tumor effect in vivo, but it has a miss target effect. STF-31 can also inhibit nicotinamide phosphoribosyltransferase (NAMPT), and the addition of nicotinic acid or the expression of drug resistant NAMPT mutants can confer resistance to STF-31, which indicates that GLUT1 inhibition is not the only target of STF-31 for tumor inhibition (Adams et al. 2014). The inhibition of glucose loaded polymer micelles loaded with cisplatin targeting GLUT1 on GLUT1 high-level OSC-19 cells and GLUT1 low-level U87MG cells was studied in vitro and in vivo. The results showed that even in tumors with low GLUT1 U87MG, the anti-tumor effect could be improved, simultaneous administration of STF-31 could inhibit the enhancement of these micellar tumor levels. These findings indicate that GLUT1 targeted therapy is a promising method to overcome the vascular barrier and promote the application of nano drugs in tumors (Suzuki et al. 2019).

Hexokinase

Hexokinase (HK) is the first rate-limiting enzyme in glycolysis, so far, four hexokinase isoenzymes have been found in mammals (Jiang et al. 2021). Among these four enzymes, Hexokinase-II (HK-II) has been observed to play a major role in maintaining high-glucose catabolic rate, which is required for the growth of tumor cells (Ciscato et al. 2021). Many HK-II inhibitors, such as 2-deoxy-D-glucose (2-DG), 3-bromopyruvate (3BP), GEN-27, have been found and have shown efficacy in preclinical trials.

2-DG has been explored/tested as an auxiliary reagent of chemotherapy drugs for breast cancer, prostate cancer, ovarian cancer, lung cancer, glioma and other types of cancer (Zhang et al. 2014; Pajak et al. 2019). 2-DG acts as a glucose mimic by inhibiting glucose formation of G6P, leading to decreased ATP production and subsequent cell death. The phosphorylation of 2-deoxyglucose to 2-deoxyglucose-6-phosphate cannot be further metabolized (Wang et al. 2012; Maher et al. 2004). In vitro studies have shown that 2-DG inhibits the growth of many cancer cell lines (Zhang et al. 2006). 2-DG has undergone Phase I/II clinical trials in the treatment of solid tumors and hormone refractory prostate cancer, but tumor growth and toxicity make it impossible to conduct further research (NCT00633087). In order to overcome the above problems and improve the pharmacokinetics and drug sample properties of 2-DG, new 2-DG analogues were synthesized, and potential prodrugs were prepared and tested. 3 -Bromopyruvate (3BP) can kill cancer stem cells, prevent cancer recurrence, and reduce chemotherapy resistance and radiation resistance common in clinical oncology. It is reported that 3BP can significantly improve the treatment effect of a patient with fibrolamellar liver cancer and another patient with metastatic melanoma (Ko et al. 2012; Sayed et al. 2014), the significant improvement faced by these patients in Phase IV strongly suggests the introduction of glycolysis inhibition therapy in the clinical field. 3BP shows its effective effect on cancer cells, which makes it an attractive candidate for cancer patient management. Compared with many anti-cancer drugs, 3BP has the characteristics of high efficiency, safety, low toxicity and good tolerance. However, further clinical trials are needed to explore its full potential as a clinical anti-cancer drug. The genistein derivative, GEN-27, is a synthetic flavonoid that was shown to suppress breast cancer cells via inhibition of HK-II and induction of cell apoptosis (Tao et al. 2017). In addition, a novel selective HK-II inhibitor, benitrobenrizine (BNBZ), exhibits nanomolar inhibitory potency. In vitro, BNBZ directly binds HK-II, induces apoptosis, and inhibits the proliferation of HK-II-overexpressing cancer cells. BNBZ also significantly inhibited glycolysis in SW1990 cells by targeting HK-II. Knocking down or knocking down the expression of HK-II in SW1990 cells reduced their sensitivity to BNBZ. Furthermore, oral BNBZ can effectively inhibit tumor growth in SW1990 and SW480 xenograft models (Zheng et al. 2021). In conclusion, BNBZ can significantly inhibit glycolysis and cancer cell proliferation in vivo and in vitro by directly targeting HK2 with high efficiency and low toxicity. Compared with other HK2 inhibitors, BNBZ can be developed as a new small molecule candidate drug for future cancer treatment.

Phosphofructokinase

Phosphofructokinase 1 (PFK1) is the second rate-limiting enzyme in glycolysis, and its activity is regulated by phosphofructokinase-2/fructose-2,6-bisphosphatase 3 (PFKFB3) regulation (Wang et al. 2020). PFKFB3 is a key rate limiting enzyme for glycolysis. Due to its strong kinase activity, the stable expression of PFKFB3 can improve the rate of glycolysis, thereby promoting the germination of blood vessels and affecting tumor angiogenesis (De Bock et al. 2013). Therefore, the effect of targeting PFKFB3 on endothelial cell (ECs) glycolysis during tumor angiogenesis has become a new research field in tumor therapy (Schoors et al. 2014; Doménech et al. 2015). PFKFB3 is overexpressed in breast, colon, nasopharyngeal, pancreatic, gastric and other tumors, and is associated with lymph node metastasis and survival (Shi et al. 2017).

PFKFB3 inhibitor 3PO and its derivative PFK15 have been proved to reduce glucose metabolism and show effective anti-tumor activity in a variety of human cancer xenotransplantation models, including tongue cancer, gastric cancer and head and neck squamous cell carcinoma (Chen et al. 2016; Zhu et al. 2016; Li et al. 2017). PFK15 is another chalcone compound developed to inhibit PFKFB3. The binding capacity of PFK15 was increased by replacing pyridinyl ring with quinoline ring in 3PO (Wang et al. 2020). This structural modification resulted in an increase in selectivity and inhibition effectiveness (about 100 fold), which led to an increase in apoptosis promoting activity compared with 3PO (Clem et al. 2013). Because of its modification, PFK15 shows better pharmacokinetic properties, such as lower clearance, higher T1/2 and longer stability of microsome (Clem et al. 2013). It is reported that PFK15 does not inhibit other glycolytic enzymes, such as phosphoglucose isomerase, PFK-1, PFKFB4 or hexokinase (Clem et al. 2013). A synthetic derivative and preparation of PFK15 have been studied on the toxicology and safety of the experimental new drug (IND), and the efficacy of PFK15 in patients with advanced cancer has been tested in Phase I clinical trial (Clem et al. 2013). The researchers expect that this new type of antimetabolic drug will produce acceptable therapeutic indicators, and prove that it has synergistic effects with drugs that interfere with tumor signals. Another effective selective PFKBB3 inhibitor, PFK158, is the first PFKBB3 inhibitor approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA). PFK158 has been proved to be effective for gynecological cancer (Mondal et al. 2019) and mesothelioma (Sarkar Bhattacharya et al. 2019). In addition, the compound participated in the Phase I clinical trial of patients with advanced solid malignant tumors. The clinical trial to evaluate the safety of PFK158 (NCT02044861) was started in 2014, and no serious adverse event was reported during the follow-up period of about one year (Lu et al. 2017). Once the maximum tolerable dose is determined, the phase II trial of this optimized PFKFB3 inhibitor will also be used for leukemia treatment (Clem et al. 2013). KAN0,438,757 (KAN) is the latest inhibitor of selective metabolic kinase PFKFB3. It has preliminarily evaluated and verified the role of CRC cells (De Oliveira et al. 2021). It is a key step before in vivo preclinical research, which in turn can establish new therapeutic targets, and can be developed as a new small molecule candidate drug of PFKFB3 for future cancer treatment.

Pyruvate kinase

Pyruvate kinase (PK) has four isoenzymes, M1, M2, L and R, which are the third rate-limiting enzyme in glycolysis. Among them, PKM2 is widely and highly expressed in tumor tissues (İlhan 2022; Zahra et al. 2020). PKM2 exists in different forms, and mostly exists in the form of dimer with low activity in tumors, which can promote tumor growth (Zahra et al. 2020).

Shikonin (a major active chemical component extracted from Lithospermum) is a PKM2 inhibitor, which can prevent cancer cells from glycolysis. In the past 40 years, shikonin has been studied as a potential anti-cancer drug for various aspects of cancer treatment (Wang et al. 2018). In addition, experimental research studies have shown that shikonin is effective in the treatment of patients with advanced lung cancer (Guo XP et al. 1991). The inhibitors in preclinical research include Benserazide (BEN), Compound 3 k (C3k) and Benzoxepane derivatives 10i, which can bind to the allosteric site of PKM2 and inhibit glycolysis (Zhu et al. 2021; Zhou et al.2020; Park et al. 2021).We discussed the recently reported PKM2 inhibitors in order to find a better treatment. Benserazide (BEN) directly binds to PKM2 and blocks its activity, thereby inhibiting aerobic glycolysis and inducing cell death of melanoma and colon cancer cells without affecting normal cells (Zhou et al. 2020; Li et al. 2017). Compound 3 k (C3k) is a selective inhibitor derivative of PKM2 synthesized by a new naphthoquinone (Ning et al. 2017). C3k has nano scale anti-tumor activity on tumor cells (Park et al. 2022). It is reported that naphthoquinone derivatives can inhibit proliferation and migration of tumor cell lines and help to induce autophagy Zhu et al. 2022). 10i is a low toxic and effective benzoxane, it inhibits PKM2 mediated glycolysis in vitro and in vivo through its anti neuritis effect (Gao et al. 2020). Compared with the known PKM2 inhibitor shikonin, this compound has better safety, indicating that it is a major target PKM2 compound for the treatment of inflammation related diseases. These findings provide more ideas for the combined use of drugs to treat tumors; as mentioned above, PKM2 is a potential therapeutic target and highly expressed in different human cancers. As mentioned above, PKM2 is a promising target for cancer treatment, but further research is needed to accurately determine the expression level and function of this enzyme in specific types of cancer.

Lactate dehydrogenase

Lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) catalyzes the last step in glycolysis, the mutual transformation of lactic acid and pyruvate. The isozymes of LDH are composedof three genes (LDHA, LDHB and LDHC), in which LDHA is responsible for converting pyruvate into lactic acid, and LDHB is responsible for converting lactic acid into pyruvate. Tumor cells mainly express LDHA (Feng et al. 2018; Jin et al. 2017), the increase of LDHA in tumors can not only promote glycolysis, but also promote the production of lactic acid, thus reshaping the tumor microenvironment, inhibiting the immune system and promoting immune escape (Serganova et al. 2018). Therefore, LDHA is a promising therapeutic target. Many studies have been devoted to the search for selective inhibitors of LDHA presently.

Gossypol/AT-101 is a derivative of cottonseed oil, which can inhibit LDHA; it has been proved that gossypol has cytotoxic effects on many tumors, including glioma cell lines (Caylioglu et al. 2021). Recently, AT-101 has been found to have a strong anti-tumor effect and improve the survival rate in patients with gastroesophageal cancer (Song et al. 2021), which is consistent with the data in vitro and animal models. A clinical trial analyzed in the review shows that patients with advanced or unresectable or metastatic or refractory tumors of different entities are included; AT-101 is beneficial to some patients and it is recommended to further test AT-101 as an anti-tumor drug (Renner et al. 2022). However, there are still some unresolved problems in these clinical trials, such as the determination of AT-101 administration level, administration frequency and treatment duration; there is no consensus on these parameters presently. So far, gossypol/AT-101 is only used for oral treatment of cancer patients; Compared with other enantiomers, AT-101 has the best therapeutic index (Renner et al. 2022) and is recommended as a candidate drug for further clinical trials. At present, there is no forthcoming or ongoing intervention trial for cancer patients to use gossypol/AT-101. In addition, the minimum recommended dose of gossypol and its exact toxicity characteristics need to be confirmed in further research. A randomized placebo-controlled trial should be conducted to verify these data in the large sample population. FX11 is a promising new gossypol derived specific LDHA small molecule inhibitor, which has recently been marketed. Studies on human lymphoma and pancreatic cancer xenografts have shown that FX11 inhibits tumor progression and induces significant oxidative stress and necrosis (Valvona et al. 2016).However, FX11 has not been proven to be a good candidate drug for the treatment of tumor diseases, because the high reactivity of this molecule may lead to many side effects caused by its biological activity (Rani and Kumar 2016). Galloflavin is an inhibitor of LDH homeotype. The mechanism of action is based on the preferential binding of free enzymes, rather than competing with substrates or cofactors. The toxicity study of Galloflavin showed that it did not cause fatal effects when administered at a maximum dose of 400 mg/kg (Manerba et al. 2012). In vitro studies have shown that Galloflavin has anti-tumor effects on a variety of cancer cell lines, such as endometrial cancer, hepatocellular carcinoma, breast cancer, etc. (Han et al. 2015; Manerba et al. 2017; Farabegoli et al. 2012). Galloflavin combined with metformin has a strong anti-tumor effect on pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma cells under normal and hypoxia conditions. This may be the basis for the treatment of disseminated metastasis of solid tumors (Wendt et al. 2020).

Monocarboxylate transporter

Monocarboxylic acid transporters are lactate/H + co transporters that play a major role in the regulation of H + and lactate efflux and pH homeostasis.The final product of glycolysis is lactic acid; the latest research shows that lactic acid is not "metabolic waste" in the traditional sense. Lactic acid can be used as an energy carrier to provide energy for tumor cells, at the same time, it can also regulate the redox balance by regulating the proportion of nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NAD) and reduced nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NADH). In addition, lactic acid can also modify histones and regulate epigenetics to promote macrophage polarization to M2 type and maintain the immunosuppressive tumor microenvironment (Sun et al. 2017; Wang et al. 2020). Therefore, as a transporter of lactic acid, monocarboxylate transporter (MCT) has become a target for regulating lactic acid. There are 4 members in the MCT family, and 14 MCT subtypes have been identified. Two of them, MCT1 and MCT4, are associated with cancer invasiveness and poor prognosis (Pinheiro et al. 2012; Counillon et al. 2016). MCT1 and MCT4 mainly regulate glycolysis by mediating the transmembrane transport of lactic acid (Benjamin et al. 2018), and glycolysis is an important way for tumor cells to obtain energy. Recent studies have found that MCT1 and MCT4 are highly expressed in many tumor cells and are closely related to tumor proliferation, invasion and prognosis (Wang et al. 2021). Therefore, MCT1 and MCT4 have gradually become the focus of research on the mechanism of tumor genesis and development.

AZD3965, developed by the method of metabolic vulnerability of tumor cells, is an oral bioavailability inhibitor of MCT1. Recent research shows that AZD3965 and structurally related MCT1 inhibitors can prevent the outflow of lactic acid in high glycolytic tumor types lacking MCT4, induce feedback inhibition of glycolytic flow, and thus produce significant anti proliferation effect (Curtis et al. 2017; Doherty et al. 2014). At present, it is in the phase I clinical study (NCT01791595), and its clinical efficacy needs further clinical trials. It is reported that AZ93 can selectively inhibit MCT4 and is currently being used in preclinical studies (Ždralević et al. 2018). Another class of compounds that can effectively reduce the lactate flux is 7-aminocarboxycoumarins (7ACCs), which selectively affect a single part of the MCT cotransporter transport cycle, resulting in inhibition of lactate influx rather than lactate efflux. In mice with tumors, these compounds play an effective anti-cancer role and can also significantly delay tumor recurrence after conventional chemotherapy (Draoui et al. 2014). 7ACCs can delay the growth of cervical cancer, colorectal cancer and breast in situ tumor constructed by tumor cells such as Si HA, HCT116 and MCF-7, and 7ACCs can also inhibit the recurrence of Si HA cervical cancer after cisplatin treatment (Draoui et al. 2014). Importantly, the unique pharmacological characteristics of 7ACC compounds illustrate key advantages, including potential reduction of side effects. Syrosingopine is an antihypertensive reserpine derivative, which can double inhibit MCT1 and MCT4 and has 60 times higher efficacy on MCT4. It was found that in HL60 (promyelocytic leukemia), OPM2 (multiple myeloma) and HT1080 (fibrosarcoma) cells, the combination of syrosingopine with the mitochondrial NADH dehydrogenase inhibitor metformin has interesting anti-cancer properties. The combination of sirosingopine and metformin can induce the loss of NAD + regeneration ability in tumor cells, which is required for the ATP generation step of glycolysis, further leading to glycolysis inhibition, ATP depletion and cell death (Buyse et al. 2022; Benjamin et al. 2018). Therefore, a reasonable combination of metformin and syrosingopine or similar entities with dual inhibitory properties of MCT1 and MCT4 is expected to become an anti-cancer therapy.

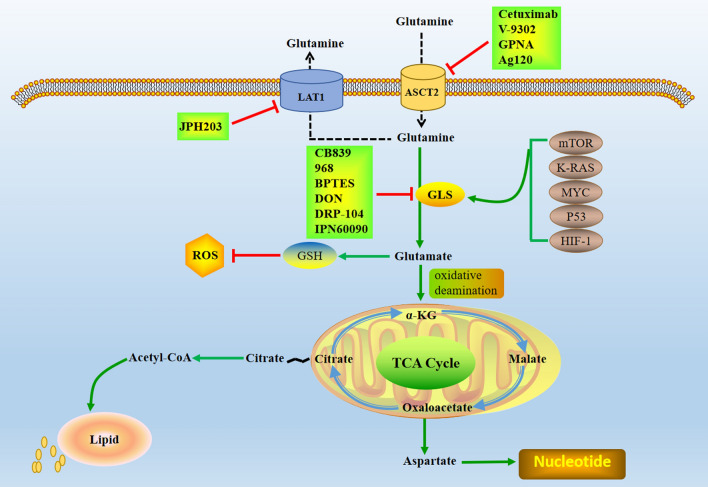

Glutamine reliance in tumor cell metabolism

Glutamine is the second nutrient source for the growth and proliferation of cancer cells, and it is the nitrogen source and carbon source used to construct purine and pyrimidine nucleotides, nonessential amino acids and glucosamine-6-phosphate (Yoo et al. 2020). In addition, glutamine reduces oxidative stress through biosynthesis of NADPH and glutathione and plays a key role in cell antioxidant mechanism (Hayes et al. 2020). Glutamine is the most abundant free amino acid in the body, which can be catalyzed by glutaminase (GLS) to glutamic acid, providing key energy for energy metabolism of tumor cells (Li and Le 2018). Normal cells produce glutamine through self-synthesis, while tumor cells need to ingest glutamine from outside the cell through membrane transporters or enhance the expression and activity of key metabolic enzymes in glutamine metabolic pathway to maintain the rapid proliferation of cells. Glutamine metabolism can provide raw materials for over-activated glycolysis and oxidative phosphorylation of tumor cells and can also induce tumor cells to resist chemotherapeutic drugs by promoting metabolic homeostasis (Hu et al. 2021). In addition to changing glucose metabolism, tumor cells also increase the use and dependence of glutamine, which is beneficial to the growth and survival of tumor cells. Glutamine enters cells via pinocytosis or membrane alanine-serine-cysteine transporter 2 (ASCT2) and macromolecular neutral amino acid transporter (LAT1) (Cormerais et al. 2018). Glutamine entering the cell is broken down into glutamate by GLS catalyzed in mitochondria (Still and Yuneva 2017). Glutamic acid is converted into α-ketoglutarate (α-KG) by oxidative deamination, and then replenished into tricarboxylic acid cycle, which promotes citric acid to be continuously exported from mitochondria and then transported to cytoplasm, producing acetyl CoA, further promoting lipid metabolism, providing energy and lipid for cells, and mediating oxidative metabolism of mitochondria (Koppula et al. 2018). In addition, glutamate is also the raw material for intracellular glutathione (GSH) synthesis, GSH is an important small molecule reducing agent in cells, which can effectively remove ROS in cells (As shown in Fig. 2). Studies have found that glutamine metabolism plays an important role in the redox homeostasis of tumor cells through the synthesis of GSH and NADPH (Long et al. 2021); thus, inhibition of glutamine metabolism is associated with higher ROS levels, which in turn promotes tumor cell apoptosis (Mukha et al. 2021). GLS, as the first key enzyme in glutamine metabolism, has been reported to improve tumor prognosis by silencing or inhibiting GLS (Hamada et al. 2021). However, transporters capable of carrying glutamine are generally up-regulated in malignant tumors, such as ASCT2 and LAT1 (Zhang et al. 2020). ASCT2 is a sodium-dependent transmembrane transporter that transports glutamine and other neutral amino acids through the plasma membrane, ASCT2 is encoded by the SLC1A5 gene and is considered to be the main transporter for glutamine uptake by tumor cells (Teixeira et al. 2021). Overexpression of ASCT2 in tumors such as gastric cancer contributes to tumorigenesis and progression, which in turn leads to metastasis and is associated with poor prognosis (Ye et al. 2018). Therefore, inhibition of ASCT2 may affect the entry of glutamine into cells, thereby inhibiting tumor proliferation, and is very likely to become a new target for anti-tumor therapy. LAT1 is a transporter that takes up neutral amino acids represented by leucine into cells (Lu 2019), LAT1-mediated leucine can activate the target protein of rapamycin (mTOR) after entering cells, so glutamine can indirectly activate mTOR (Martinez et al. 2021). Another study found that the higher the expression level of LAT1, the larger the metastasis of gastric cancer (Häfliger and Charles 2019), indicating that LAT1 plays an important role in promoting the progression of tumor cells.

Fig. 2.

Glutamine metabolism in tumor cells and its effective targets. Glutamine metabolism as a target for cancer therapy, glutamine is imported through transporters and then enters a complex metabolic network through which its carbon and nitrogen are supplied to pathways that promote cell survival and growth. ASCT2 alanine-serine-cysteine transporter 2, LAT1 L-type amino acid transporter 1, GSH glutathione, GLS glutaminase

The dependence of tumor cells on glutamine is largely due to the activation of proto oncogenes and the inactivation of oncogenes. Oncogenes regulate the expression of glutamine metabolism related enzymes or transporters and participate in the demand of tumor cells for glutamine metabolism. It includes hypoxia inducible factor-1 (HIF-1), mTOR, murine sarcoma virus oncogene (K-RAS), cell myelocytoma virus proto oncogene (MYC), P53 and other genes, which can induce the occurrence and development of tumors by participating in the regulation of glutamine metabolism. HIF-1 is regarded as the core molecule of an oxygen sensing mechanism in the body, that is, hypoxia reduces the activity of accumulated mitochondrial ATP synthetase, further increases the GLS activity, and promotes the growth of tumor cells (Pezzuto and Carico 2018). The mitochondrial enzyme complex α-ketoglutarate dehydrogenase (α-KGDH) acts as a glutamine oxidase that decomposes intracellular glutamine. Activation of HIF-1 can inhibit the expression of α-KGDH and further reduce the breakdown of glutamine, thereby providing the energy and lipids required for tumor cells to grow and promoting their growth (He et al. 2019). Therefore, inhibiting the expression of HIF-1 in tumor cells can effectively inhibit the growth of tumor cells and is likely to become a target for tumor therapy. mTOR is a class of highly conserved serine/threonine kinases that can be activated only with the participation of amino acids, and activated mTORC2 can up-regulate glutamine. GLS decomposes glutamine into α-KG and further regulates downstream mTOR to activate and activate its activity, thereby regulating the proliferation of tumor cells (Yamashita et al. 2020). Reducing the expression of mTOR protein in tumor cells can promote tumor cell apoptosis and effectively inhibit the occurrence and development of tumors; therefore, mTOR is a promising target for tumor therapy. KRAS is a gene closely related to cell growth and differentiation, the normal KRAS gene inhibits the occurrence and development of tumors, and the acquired mutation of the KRAS gene is the main driver of malignant transformation of various tissues (Janes et al. 2018). In KRAS mutant tumor cells, the expression of genes related to glutamine metabolism is up-regulated; glutamine is the main carbon source of the TCA cycle, which leads to the increase of glutamine entering the TCA cycle and promotes anabolism (McDonald et al. 2019). Therefore, by regulating the mutation of KRAS to further affect glutamine metabolism, thereby regulating tumor growth, it is expected to be an effective treatment method. As a proto-oncogene that is highly expressed in various tumors, MYC is closely related to cell growth regulation and metabolic processes (McAnulty and DiFeo 2020). It can activate genes related to metabolic processes such as glutamine, thereby regulating the energy metabolism of cells and promoting the occurrence and development of tumors (Wahlström and Henriksson 2015). Studies have shown that MYC can promote the uptake of glutamine by cells and make tumor cells addicted to glutamine, and when glutamine is deficient, cells undergo apoptosis. Furthermore, as a transcription factor, MYC directly binds to the promoter of the glutamine transporter ASCT2 and stimulates its expression, thereby promoting glutamine metabolism (Tambay et al. 2021). It can be seen that the MYC gene is closely related to the metabolism of glutamine, and inhibiting the overexpression of MYC may inhibit tumorigenesis. P53 is a tumor suppressor gene capable of inducing cell cycle arrest and apoptosis under conditions of DNA damage, hypoxia or oncogene activation (Hong et al. 2014). P53 has also been found to regulate metabolic pathways in response to challenges posed by energy or DNA damage in recent years (Chang et al. 2021).

The researchers started looking for inhibitors of the glutamine transporter, which would limit the entry of glutamine into tumor cells. The increase of glutamine metabolism in tumor cells is mainly due to the enhanced activity of transporters and related enzymes, and the most studied inhibitors are mainly directed against these two targets. LAT1 has been considered as a promising therapeutic and diagnostic target for cancer (Kanai 2022). The highest evaluated and clinically advanced LAT1 specific high affinity compound IPH203. More and more preclinical studies have reported the anticancer effect of JPH203 in vitro and in vivo (Kanai 2022; Oda et al. 2010). JPH203 inhibits the proliferation of various cancer cells from different tissues/organs and also inhibits the migration and cell cycle progression of cancer cells in vitro (Nishikubo et al. 2022). JPH203 has been proved in animal models to be able to resist the growth inhibition of thyroid cancer, colorectal cancer, T-cell lymphoblastic lymphoma/T-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia and other tumors (Enomoto et al. 2019; Rosilio et al. 2015; Muto et al. 2019). In the first human phase I clinical trial (UMIN000016546) for patients with advanced solid tumors, JPH203 was well tolerated and provided promising anti biliary cancer activity (Yothaisong et al. 2017). A randomized phase II clinical trial of JPH203 for patients with advanced biliary cancer is currently being conducted in Japan (UMIN000, 034, 080) (Okano et al. 2020). ASCT2 has been identified as an egfr-related protein that can be co-targeted by cetuximab, an egfr antibody approved for the treatment of metastatic human head and neck squamous cell carcinoma by reducing the intracellular level of glutamine, thereby reducing the intracellular level of glutathione, sensitizes cancer cells to ROS-induced apoptosis (Lopes et al. 2021). Research shows that small molecular compounds such as V9302 (Schulte ML et al. 2018), l-γ- Glutamyl p-nitroaniline (GPNA) (Wang et al. 2022) inhibits the influence of ASCT2 on cancer growth. However, each of these methods has some limitations, such as high toxicity and poor solubility. And it is urgent to continue to search for new ASCT2 inhibitors for cancer treatment. Ag120 is also known as ivosidenib. It was first reported in 2022 that Ag120 is an ASCT2 inhibitor in CRC cells of colorectal cancer and inhibits tumor growth by inhibiting glutamine uptake and metabolism (Yu et al. 2022). This study not only broadens the new mechanism of Ag120’s anti-tumor activity, but also supports further exploration of ASCT2 inhibitors for cancer treatment. Inhibiting glutamine transporter and glutamine starvation represents a promising cancer treatment strategy. Another effective therapeutic target in glutamine metabolism is GLS (Edwards et al. 2021), which exists in two isoforms, GLS1 and GLS2. Since GLS2 is likely to catalyze glutamine metabolism, which in turn increases intracellular GSH and NADPH levels, and reduces intracellular ROS levels; therefore, GLS2 is considered to be a tumor suppressor. However, GLS1 may promote tumor development (Liu et al. 2014), its activity can be inhibited by gene silencing or chemical inhibitors. One of the best studied glutaminase inhibitors is 6-diazo-5-oxo-L-leucine (DON), which is a glutamine antagonist. The mechanism of action is based on irreversible covalent bonding with the active site of the enzyme. It also inhibits another glutamine-dependent enzyme, glutamine aminotransferase (Lemberg et al. 2018), which inhibits the metabolism of cancer cells, but at the same time enhances the metabolic adaptability of tumor CD8 + T cells. In a small clinical study, DON showed evidence of anti Hodgkin's lymphoma and other cancer activities (Rais et al. 2016). However, its use in clinical treatment was limited due to unacceptable gastrointestinal toxicity (nausea and vomiting). In view of its clinical potential, DRP-104 (sirpiglenastat) has been designed as a new prodrug of the broad-spectrum glutamine antagonist DON, which is preferentially biologically activated as DON in tumors and inactivated as an inert metabolite in gastrointestinal tissues. In the drug distribution study, compared with gastrointestinal tissues, DRP-104 makes DON 11 times more likely to be exposed to tumors (Rais et al. 2022; Yokoyama et al. 2022). DRP-104 has been used in combination with atezolizumab (anti PD1) in clinical practice, and a positive trial has been conducted for patients with advanced solid tumors (NCT04471415). DRP-104 is now in the clinical trial designated by FDA fast track, which shows that the drug has great clinical application potential as a glutamine antagonist. Compound 968, was found to be an allosteric inhibitor of GLS, and its inhibitory potential on cancer cell migration and proliferation has been reported (Wang et al. 2021). In ovarian cancer, compound 968 significantly inhibited cell proliferation and increased cell sensitivity to paclitaxel treatment (Yuan et al. 2016). The GLS1 inhibitor BPTES targets glutaminolysis to prevent proliferation of the related human breast cancer cell lines MCF7 (estrogen receptor dependent cell line) and MDA-MB231 (triple negative cell line), which are glutamine addicted (Nagana Gowda et al. 2018). CB-839 is another potent oral GLS1 inhibitor that is more effective than BPTES and has anti-tumor activity in vivo. At present, many clinical trials are being conducted in various types of cancer in the status of “recruitment” and “active non recruitment”, among which CB-839 is mainly used in combination with other drugs used in anti-cancer treatment. CB-839 has been evaluated in two complete clinical trials. At present, it is being evaluated in combination with azacytidine for myelodysplastic syndrome (NCT03047993), sapanisertib for non-small cell lung cancer (NCT04250545), nivolumab for melanoma, clear cell (conventional) renal cell carcinoma, and non-small cell lung cancer (NCT02771626) Combined with radiotherapy and temozolomide in the treatment of isocitrate dehydrogenase (IDH)—mediated diffuse astrocytoma (NCT03528642). Disappointingly, when CB-839 was combined with cabozantinib (Tannir et al. 2021), it was not proved to be effective for RCC, and the results of other trials still need to be confirmed. Therefore, another compound was produced by optimizing physicochemical and pharmacokinetic properties from the structure of BPTES eutectic. Compared with CB-839, IPN60090 developed from different stents has better pharmacokinetic characteristics and lower dose in vivo efficacy in NSCLC patients derived xenotransplantation model combined with mTORC1/2 inhibitor (Soth et al. 2020). It is conducting Phase I study on open label (NCT03894540).

Lipid metabolism alterations in cancer cells

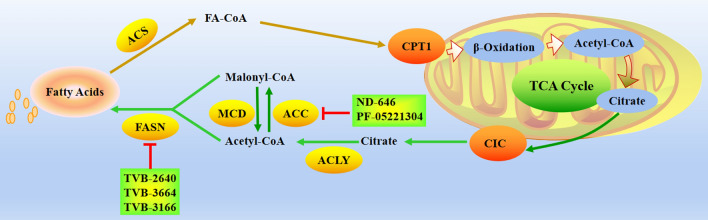

Fatty acids are key components of cell membranes and can also act as signaling molecules or store energy (de Carvalho CCCR and Caramujo 2018). It has been found that different tumor cell types or microenvironment may choose different ways to obtain lipids, such as obtaining lipids from ab initio synthesis, ingesting lipids from blood or hydrolyzing stored triglycerides, all of which play a role in tumor development (Snaebjornsson et al. 2020; Bia et al. 2021). Restricting lipid metabolic pathways can be used as a strategy to treat cancer, such as limiting lipid sources, blocking lipid utilization, and preventing lipid droplet formation. The fatty acid synthesis pathway is currently considered to be the main pathway used by cancer cells to acquire lipids (Koundouros and Poulogiannis 2020), and activation of the de novo fatty acid synthesis pathway is required during carcinogenesis, there is increasing evidence that targeting fatty acid de novo synthesis may be effective in the treatment of certain cancers (Koundouros and Poulogiannis 2020; Jin et al. 2021). Fatty acid synthesis occurs mainly in the cytoplasm: first, the acetyl-CoA group is converted to malonyl-CoA by acetyl-CoA carboxylase (ACC); then, fatty acid synthase (FASN) assembles malonyl-CoA into fatty acid chain palmitate (Fig. 3). While fatty acid synthesis occurs in the cytoplasm, acetyl-CoA is produced from citrate in the mitochondria, which is exported from the mitochondria and cleaved by ATP-citrate lyase (ACLY) in the cytoplasm. Certain tumor cells can also use cytoplasmic acetate to produce acetyl-CoA (Zhao et al. 2021; Bose et al. 2019), for example, some cancers rely on acetyl-CoA synthetase 2 (ACSS2) to convert acetate to acetyl-CoA, making it a potential therapeutic target (Ling et al. 2022). At present, many preparations for inhibiting fatty acid synthesis have been developed, mainly targeting ACLY, ACC and FASN.

Fig. 3.

Fatty acid biosynthesis metabolism in tumor cells and targeted representative clinical small molecules. Acetyl-CoA is converted to malonyl-CoA by ACC, FASN then assembles malonyl-CoA into the fatty acid chain palmitate. CIC citrate carrier, CPT1 carnitine palmitoyltransferase 1, ACLY ATP citrate lyase, ACC acetyl-CoA carboxylase, MCD malonyl-CoA decarboxylase, FASN fatty acid synthase, ACS Acetyl-CoA synthase

ACLY activity is elevated in cancer, and genetic or chemical targeting of ACLY can inhibit xenograft tumor growth (Granchi 2018; Fhu and Ali 2020). Reducing the expression of ACC gene induces apoptosis in cancer cells, and ND-646, an allosteric inhibitor of ACC, also showed antitumor effects in a mouse lung cancer model (Li et al. 2019). Another oral liver targeting ACC1 and ACC2 inhibitor PF-05221304 is currently in the clinical study of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease fibrosis (NCT03248882) (Bergman et al. 2020). In view of its preliminary safety in the Phase I study, that is, mild thrombocytopenia occurs at high doses, it will be of great significance to evaluate the activity of PF-05221304 in the preclinical model, especially the activity of hepatocellular carcinoma. Malonyl coenzyme a produced by ACC is further extended by FASN, so it becomes a unique tumor target. FASN has become a unique tumor target. FASN inhibitors are undergoing preclinical research and are beginning to transition to the first human trial. Early FASN inhibitors have been pre clinically studied, but are limited by their pharmacological properties and side effects. A new generation of molecules, including GSK2194069, JNJ-54302833, IPI-9119 and TVB-2640, are under development, but only TVB-2640 has entered the clinic (Jones SF and Infante JR 2015). TVB-2640 is a small molecule, highly selective oral FASN inhibitor. TVB-2640 is the first FASN inhibitor to enter clinical trials of advanced cancer. The Phase I trial included treatment of patients with colon cancer or other resectable cancers (NCT02980029). Several phase II clinical trials include the treatment of metastatic patients with KRAS mutant non-small cell lung cancer (NCT03808558), the combination of TVB-2640, paclitaxel and trastuzumab in the treatment of HER2 positive metastatic breast cancer patients (NCT03179904), and the combination of TVB-2640 and bevacizumab in the treatment of high-grade astrocytoma patients with the first recurrence (NCT03032484) (Brenner et al. 2015). The other two new FASN inhibitors, TVB-3664 and TVB-3166, have shown anti-tumor activity against various types of tumors in vitro and in vivo. However, there is no report on their application in further clinical trials (Ventura et al. 2015; Zaytseva et al. 2018; Tao et al. 2019).

In tumor cells, the enhancement of fatty acid oxidation (FAO) occurs simultaneously with the enhancement of de novo fatty acid synthesis (Ma et al. 2018; Zhelev et al. 2022). Carnitine acyltransferase 1 (CPT1) is a key enzyme in the FAO process (Schlaepfer and Joshi 2020); fatty acids are first activated to acyl coenzyme A and then transported by CPT1 to mitochondria for FAO to generate acetyl coenzyme A and enter the tricarboxylic acid cycle (Fig. 4). These processes not only produce ATP to supply energy to cells, but also prevent lipid toxicity caused by excessive accumulation of lipids. The acetyl coenzyme A produced enters the cytoplasm to participate in the metabolic reaction of NADPH production and generates a large amount of NADPH to support the redox homeostasis of cells, so as to prevent the oxidative damage of tumor cells (Mikalayeva et al. 2019). FAO plays a key role in tumor cell proliferation and chemotherapy resistance, inhibiting FAO in mitochondria will affect the production of NADPH, increase the production of reactive oxygen species, lead to the consumption of ATP in glioblastoma cells, and cause cell death (Duman et al. 2019). Targeting the key enzyme CPT1 in the FAO pathway can enhance the radiotherapy effect of nasopharyngeal carcinoma patients (Tang et al. 2022). Studies have shown that the reprogramming of mitochondrial FAO is enhanced in breast cancer, and the expression of CPT1A/CPT2 is enhanced in recurrent breast cancer, which is related to the poor prognosis of breast cancer patients (Han et al. 2019).

Fig. 4.

Enhancement of FAO in tumor cells and targeted representative clinical small molecules. Long-chain fatty acids enter cells via fatty acid transporters and then shuttle into mitochondria via the carnitine shuttle system. In mitochondria, fatty acids are oxidized in the form of acetyl-CoA to remove consecutive 2-carbon units. Both the FAO and TCA cycles produce reduced electron carriers (NADH/FADH2), which generate ATP. The carbon and hydrogen sources of acetyl-CoA produced by FAO can be exported to the cytoplasm outside the TCA cycle to participate in NADPH production

Avocacin B is a lipid derivative isolated from avocado fruit and belongs to CPT1 inhibitor. Studies have shown that avocatin B reduces the proliferation and viability of AML cells by inhibiting CPT1 and other ways and will not affect normal hematopoietic stem cells (Lee et al. 2015). Perhexiline is an anti angina drug that has been used since the 1970s. It is a compound that inhibits CPT1 and CPT2 (Liu et al. 2016; Ashrafian et al. 2007). Piperidine is very effective in reducing the viability of chronic lymphocytic leukemia cells in the matrix microenvironment. These results were confirmed in vivo in transgenic mice model of chronic lymphocytic leukemia (Ashrafian et al. 2007). Another CPT1 inhibitor is oxfenicine, and the number of scientific reports on anti-cancer activity is limited (Keung W et al. 2013). The compound showed anti-cancer activity in the study of malignant melanoma HBL cells in vitro (Mascagna et al. 1992). The inhibition of CPT1 by etomoxir (Eto) efficiently slows down the growth of various cancers. Unfortunately, the clinical use of this drug was abandoned because of hepatotoxic effects (Deskeuvre et al. 2022; Reis et al. 2019). ST1326 (Tegliar), as a derivative of other CPT1 inhibitors from aminocarnitine, is currently in the preclinical experimental research stage, which can prevent the growth and treatment of cancer cells in leukemia and lymphoma (Pacilli et al. 2013; Mao et al. 2021). Therefore, drug development for CPT1 target is another key to tumor treatment.

Many lipid signaling molecules are involved in signal transduction cascades, which in turn regulate various oncogenic processes such as cell proliferation, migration, invasion, immune response, and metastasis. Among them, phosphatidylinositol 3,4,5-trisphosphate (PIP3), lysophospholipid, prostaglandin (PG), and platelet-activating factor (PAF) play a role in tumor signal transduction plays a key role (Goncalves et al. 2018; Sipos et al. 2021; Wang et al. 2022; Lordan et al. 2019). PIP3 is an important phosphatidylinositol that regulates cell survival, proliferation, and growth and can be dephosphorylated by the phosphatase PTEN to terminate PI3K signaling. During tumorigenesis, the catalytic domain of PI3K is mutated, i.e., the loss of function of PIK3CA and PTEN mutations results in the inability to dephosphorylate PIP3 to overactivate AKT (Gozzelino et al. 2020), which is central to the immortal proliferation of tumor cells. In addition, the use of kinase inhibitors to inhibit the production of PIP3 may become a new strategy for tumor treatment. Lysophosphatidic acid, an intercellular phospholipid messenger, can promote tumor cell progression by acting on G protein-coupled receptors, and lysophosphatidic acid may serve as a potential predictor for evaluating gemcitabine efficacy in pancreatic cancer patients (Rodríguez-Nogales et al. 2019). In addition, lysophosphatidic acid and lysophosphatidic acid receptors are also highly expressed in various tumor cells such as ovarian cancer, breast cancer and colon cancer (Nam JS et al. 2018; Ishimoto et al. 2021; Cui et al. 2020), suggesting that lysophosphatidic acid may be involved in tumorigenesis. PG is a class of unsaturated fatty acids with 20 carbon atoms, which is closely related to the progression of various tumors besides participating in the inflammatory response (Jara-Gutiérrez and Baladrón 2021). PGE2 plays an important role in the occurrence and development of colorectal cancer by binding to downstream receptors EP1, EP2, EP3, and EP4 to regulate the functions of various immune cells (Mizuno et al. 2019). In addition, the generation of PGE2 through the action of cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2) can promote colon cancer cell proliferation, invasion, metastasis, angiogenesis, drug resistance, inhibit colon cancer apoptosis, and target COX-2/PGE2 The/EP receptor has a good effect on colon cancer (Cai and Gao 2021), and PGE2 mainly promotes tumor progression by promoting tumor angiogenesis, inducing tumor cell proliferation, and inhibiting apoptosis (De Paz Linares et al. 2021). In addition, PAF, as a lipid signaling molecule, is a key pro-inflammatory mediator in tumorigenesis and progression (Lordan et al. 2019). PAF plays an irreplaceable role in suppressing the immune system and promoting tumor growth and metastasis by altering local angiogenesis and cytokine networks. PAF can promote angiogenesis, proliferation and metastasis of ovarian cancer, breast cancer and melanoma (He et al. 2021; Wang et al. 2016; Romer et al. 2018).

Emerging roles of nucleotide synthesis in cancer progression

Nucleotides are the basic structural units of nucleic acids; intracellular free nucleotides are extremely important substances in metabolism and participate in almost all biochemical processes in cells. Some key enzymes in the nucleotide metabolic pathway of tumor cells can also become targets of antitumor drugs. The acquisition of nucleotides is crucial for cell proliferation, the ways of obtaining nucleotides mainly include de novo synthesis and remedial synthesis (Lane and Fan 2015; Chandel 2021). Purine nucleotides are mainly synthesized from simple compounds such as aspartic acid, glycine, glutamine, CO2 and one carbon unit. The first synthesize hypoxanthine nucleotides through 11 steps of enzymatic reaction, and then the hypoxanthine nucleotides are converted into adenosine acid and guanylic acid through amination at different positions (Camici et al. 2019). The first step in the synthesis pathway is the activation of 5-phosphoribosyl 1-pyrophosphate (PRPP) by enzyme catalysis, which is an important reaction; the key enzymes in the synthesis process include PRPP amidotransferase and PRPP synthase, the raw materials for de novo synthesis of pyrimidine nucleotides are glutamine and aspartic acid (Okesli et al. 2017). In mammalian cells, carbamoyl phosphate synthase (CAD) is the main regulator of pyrimidine nucleotide synthesis. Main synthesis process: the pyrimidine ring and 5-PRPP were catalyzed by dihydroorotate dehydrogenase (DHODH) to form the first pyrimidine nucleotide (orotate nucleoside 5 '- monophosphate, OMP), and then uracil nucleotide (UMP) was formed. Under the action of a series of enzymes, UMP produces cyntridini trip phosphate (CTP) (As shown in Fig. 5). De novo synthesis of pyrimidine and purine is essential for mRNA synthesis and DNA replication in growing and proliferating cancer cells; therefore, these pathways contain multiple potential therapeutic targets.

Fig. 5.

Tumor cell nucleotide synthesis and targeted representative clinical small molecules. Purine synthesis is a multi-step, multi enzyme pathway, using PRPP as a scaffold to generate IMP from glutamine, glycine, aspartic acid and cho-thf, further generate amp and GMP. The synthesis of pyrimidine is a multi-step process, using PRPP as a scaffold to produce UDP from glutamine, carbonate and aspartic acid. It is converted into dTMP by TYMS. PRPP phosphoribosyl pyrophosphate, DHFR dihydrofolate reductase, DHODH dihydrowhey dehydrogenase, IMP inosine monophosphate, IMPDH inosine phosphate dehydrogenase, TYMS thymidylate synthase

Clinical trials of some antimetabolic drugs have successfully proved that tumor cells rely on de novo synthesis of nucleotides. Nucleotide biosynthesis is associated with other metabolic pathways. Ribose is obtained from glucose through PPP, the carbon source of nucleotide base comes from amino acid and one carbon cycle, and the nitrogen source comes from aspartic acid and glutamine. Therefore, the metabolism of targeted amino acids and folate will affect the production of nucleotides. For example, restricting serine and aspartic acid and blocking folate pathway will reduce purine biosynthesis (Ducker et al. 2016; Fan et al. 2019; Sullivan et al. 2015). The next research needs to explore whether these pathways have synergistic effects with existing antimetabolic drug therapies.

In addition to obtaining nucleotides through de novo synthesis, cells also reuse nucleotides from the surrounding environment through remediation. Recycled nucleotides often contain various epigenetic modifications; if some nucleotides carrying modified bases are randomly inserted in the replication process, it may have a significant impact on the fidelity of the genome. Normal cells have some mechanisms to avoid this condition. However, some cancer cell lines overexpress cytosine deaminase (CDA). When exposed to two different oxidized forms of 5- methylcytosine, it will be converted into modified uracil and inserted into DNA, resulting in the accumulation of DNA damage, which eventually inducing cell death (Zauri et al. 2015). Therefore, different oxidized forms of 5-methylcytosine can be selectively used to target tumors that overexpress CDA. Nucleotide production is also regulated by some carcinogenic signaling pathways. Activation of mTOR can increase ribose synthesis through PPP (Chi et al. 2020), suggesting that targeting nucleotide metabolism may be more effective in tumors with over activation of mTOR. Cells that activate mTOR signaling pathway by PTEN deletion are more sensitive to the inhibition of DHODH (Mathur et al. 2017). KRAS/LKB1 null lung cancer cells rely more on carbamoyl phosphate synthase-1 (CPS1) in the urea cycle for pyrimidine biosynthesis (Kim et al. 2017).

Early studies found that aminopterin can be used to treat acute lymphoblastic leukemia, and subsequently, it was replaced by methotrexate due to the unpredictability of its toxicity (Ribera Santasusana JM 2020). Methotrexate targeting dihydrofolate reductase plays a key role in the development of cancer chemotherapy. Subsequently, more and more antimetabolic drugs that inhibit nucleotide synthesis have been successfully used in cancer treatment, which is due to the increased demand for DNA replication of tumor cells. Pemetrexed is a new anti-tumor drug based on the classic anti metabolic drugs methotrexate and fluorouracil, which has a multi-target effect on the folic acid dependent pathway (Hochster 2002). In recent years, it has achieved good efficacy in the treatment of non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) (Kenmotsu et al. 2020). Thymidylate synthase (TS) is a key enzyme in DNA synthesis and one of the main targets of pemetrexed (Ding et al. 2017). In addition to the nucleoside antimetabolic drugs used in clinic, efforts have recently been made to develop other drugs to target purine or pyrimidine metabolic enzymes. Although Mycophenolic Acid (MPA) is applied as prodrugs in clinic as an immunosuppressant, it also possesses anticancer activity (Siebert et al. 2021). Mycophenolate mofetil nanoparticles can achieve enhanced anti hepatocellular carcinoma efficacy by targeting tumor-related fibroblasts. Mycophenolate mofetil alone or in combination with tacrolimus inhibits the proliferation of HT-29 human colon adenocarcinoma cell line and may interfere with the occurrence of colon tumors (Ling et al. 2018). At present, IMPDH2 inhibitors have been developed as potential anticancer drugs. Another target is dihydrowhey dehydrogenase (DHODH), the key enzyme of pyrimidine synthesis, which is located in mitochondria; it is the key enzyme of pyrimidine synthesis in nucleic acid catalysis and catalyzes the fourth-step reaction in the de novo biosynthesis pathway of pyrimidine (Zhou et al. 2021). Leflunomide is the first FDA approved DHODH inhibitor; it is a synthetic isoxazole compound used in the clinical treatment of rheumatoid arthritis. Researchers have confirmed that leflunomide can significantly kill tumor cells with MEN 1 mutation in cell models and nude mice transplanted tumor models (Ma et al. 2022). This study may provide new ideas and strategies for the treatment of MEN1 mutant tumors and the safeguarding of patients with MEN1 syndrome. AG-636 is a new and effective small-molecule inhibitor of DHODH, which has good oral administration characteristics in humans. The preclinical data of AG-636 demonstrated the vulnerability of tumor cells from hematology to the inhibition of DHODH support and initiated the phase 1 study of AG-636 for relapsed/refractory lymphoma (NCT03834584). Together with the ongoing clinical studies of other DHODH inhibitors in AML, the potential of DHODH inhibition as a pedigree-based treatment strategy will begin to be clarified (McDonald et al. 2020).

Redox signal regulation and tumor metabolism

Oxidative stress is an important biological feature of tumor cells.Compared with normal cells, tumor cells tend to have higher levels of ROS, resulting in oxidative stress. Oxidative stress with a certain threshold can promote the occurrence and development of tumors by regulating various signal pathways in cells, while excessive oxidative stress can lead to oxidative damage and even tumor cell death (Sies and Jones 2020). Therefore, while tumor cells have a high ROS level; they will also activate the intracellular antioxidant system to relieve oxidative stress, maintain intracellular redox homeostasis and promote tumor cell survival. A large number of studies have shown that tumor cell metabolic reprogramming plays an important role in ROS production, antioxidant system activation and the maintenance of redox homeostasis (Wang et al. 2019).

Uncontrolled accumulation of reactive oxygen species will activate cell death signals. After being triggered, superoxide dismutase protein will convert reactive oxygen species into hydrogen peroxide, which is detoxified by peroxidases (PRXs) or glutathione (Wang et al. 2018). Oxidized PRX and glutathione disulfide are recovered by thioredoxin reductase and glutathione reductase, respectively. NADPH is required as reductant for both circulating metabolism (Sarniak et al. 2016); therefore, cancer cells upregulate NADPH production and metabolism and antioxidant enzymes to maintain redox homeostasis. Cancer cells upregulate the activity of antioxidant nuclear transcription factor NF-E2 related factor (NRF2) to maintain redox homeostasis, which is the main regulator of cellular oxidative stress response (He et al. 2020). Under normal conditions, Kelch-like ECH related protein 1(KEAP1) ubiquitinates NRF2 and promotes its degradation through Culin 3-dependent E3 ligase complex. However, hypoxic environment or oxidative stress can separate KEAP1-NRF2 interaction, thus promoting NRF2 activity (Sajadimajd S and Khazaei 2018). Oncogene signaling (KRAS, B-Raf, and Myc etc.) increases Nrf2 activity by inhibiting KEAP1; NRF2 activates the expression of antioxidant enzymes that induce the synthesis of glutathione, TRX, PRX, and NADPH (Fig. 6).

Fig. 6.

Redox regulation of tumor cells: SOD converts active oxygen into hydrogen peroxide, which is detoxified by PRXs or glutathione, NADPH is required as reductant for both circulatory metabolism. Oncogene signals (such as KRAS, B-Raf and MYC) increase NRF2 activity by inhibiting KEAP1, NRF2 activates the expression of antioxidant enzymes that synthesize glutathione, TRX, PRX and NADPH. BPK-29 can effectively block the interaction between NRF2 regulatory protein NR0B1 and protein. SOD superoxide dismutase protein, PRXs Peroxidases, KEAP1 Kelch like ECH related protein 1, NRF2 antioxidant nuclear transcription factor NF-E2 related factor

The research on redox modification of tumor metabolic enzymes provides a new opportunity for tumor treatment strategies targeting tumor metabolism and oxidative stress. In recent years, a study found that high-dose vitamin C treatment can lead to a large amount of GSH consumption and ROS accumulation, which in turn promotes the glutathione modification of the 152nd cysteine (Cys152) of GAPDH, resulting in the inactivation of GAPDH, and finally kills the colon cancer cells with KRAS and BRAF mutations by inhibiting glycolysis and consuming ATP (Yun et al. 2015). However, the accumulation of ROS induced by vitamin C is a universal effect, which may lead to the oxidation of other proteins except GAPDH, thus producing synergistic effect, neutralization effect and even toxic side effects on normal cells. In order to solve the specificity of targeted protein redox modification, Professor CRAVATT's team developed a competitive isotope tandem orthogonal proteolysis activity-based protein profiling (ISOTOP-ABPP) screening technology. Through competitive isoTOPABPP screening combined with fragment based ligand discovery (FBLD) strategy, BACKUS et al. (Backus et al. 2016) established a library of electrophilic small molecules that can covalently react with cysteine. Subsequently, the research team took NRF2 as the research object. Through screening this library of electrophilic small-molecule compounds, it was found that BPK-29 could specifically covalently bind to the NRF2 regulatory protein NR0B1 position 274 cysteine (Cys274), thus damaging the NR0B1 protein complex and inhibiting the growth of KEAP1 mutant non-small cell lung cancer cells (Bar-Peled et al. 2017). This study confirmed the feasibility of specifically targeting protein redox modification; with the development of this field, small molecule compounds with potential anti-tumor activity and specific target for redox modification of metabolic enzymes will be discovered and developed one after another.

Conclusions and perspectives

Common therapies, such as chemotherapy and hormone therapy, are widely used in cancer treatment; however, the side effects of these methods show the need for alternative target routes. Targeting cancer metabolism with various transformation pathways, enzymes and metabolites seems to be the way forward, it has become a top priority to develop new treatment strategies with high efficiency and little side effects. It has been found that the energy metabolism of cancer cells is highly dynamic and heterogeneous, and the metabolic changes of tumor cells play a key role in the characteristics of cancer such as migration, invasion and metastasis (Pavlova et al. 2022). The new discovery of cancer metabolic reprogramming provides metabolic weakness to promote cancer treatment. Due to the basic metabolic differences between normal cells and cancer cells, targeted altered cell metabolism is also considered as a potential method to achieve therapeutic selectivity, targeting some points in the metabolic pathway can reduce the proliferation of cancer cells. The change of glycolysis, that is, the production of lactic acid rather than the delivery of pyruvate to the TCA cycle, makes tumor cells rely mainly on aerobic glycolysis (Abdel-Wahab et al. 2019). In order to meet the needs of rapid proliferation, tumor cells produce ATP through glutamine-driven oxidative phosphorylation (Matés et al. 2020). In addition, tumor cells can use fatty acid synthesis and lipolysis to meet their needs for fatty acids to provide energy for the growth and development of tumor cells (Broadfield et al. 2021). De novo synthesis of nucleotides is essential for mRNA synthesis and DNA replication in tumor cells (Hager et al. 2020). The key role of some metabolic enzymes in these pathways opens a new window for the fight against uncontrolled cell proliferation. In brief, selectively targeting metabolic reprogramming of tumor cells is an attractive direction for tumor therapy. Therefore, the inhibitory effect of some drugs was examined in the preclinical or clinical stage as presented in Table 1, and the promising results point in the right direction for more progress; however, finding and focusing on ways to improve more selective effects remains challenging. There are many problems with this method presently, because metabolic enzymes on metabolic pathways tend to have multiple isoforms, small-molecule inhibitors may not be able to distinguish between the isoforms of these metabolic enzymes expressed in tumor cells and normal cells. Even if specific inhibitors are developed, resistance to therapy may occur during treatment due to metabolic atrophy of other subtypes. Another reason for the development of treatment resistance is that the tumor will develop another metabolic pathway. Therefore, in order to avoid the adaptive resistance of tumor cells, two metabolic pathway inhibitors can be used in combination, and metabolic inhibitors can also be tried as adjuvant therapy for other treatments. In addition, nanomaterial-loaded micromolecule metabolic inhibitors can be used as adjuvants of conventional anti-tumor drugs to improve the biological safety of metabolic inhibitors. Nanoplatform can also induce cancer cell apoptosis by enhancing ROS production that inhibits tumor growth. Nano-functional materials can not only realize the anti-tumor function of loaded drugs, but also improve cancer treatment (Tang et al. 2021).

Table 1.

Small molecules that target cancer metabolism

| Agent | Target | Pathway | Tumor type | Stage | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BAY-876 | GLUTs | Glycolysis | Hepatocellular carcinoma | Preclinical studies | Yang et al. (2021) |

| WZB117 | NSCLC, colon and KRAS mutation cancer | Preclinical studies | Shima et al. (2022) | ||

| STF‐31 | Renal-cell carcinoma | Preclinical studies | Adams et al. 2014) | ||

| Ritonavir | Progressive or recurrent high-grade gliomas | Phase II clinical trials | Ahluwalia et al. (2011) | ||

|

Deoxyglucose (2-DG) |

HK-II | Glycolysis | Lung, breast, pancreatic and prostate cancer | Preclinical and clinical studies | Zhang et al. (2014); Pajak et al. (2019) |

| 3-bromopyruvate(3BP) | Liver cancer,melanoma | Preclinical and clinical studies | Ko et al. (2012); El Sayed et al. (2014) | ||

| GEN-27 | Human breast cancer cells | Experimental | Tao et al. (2017) | ||

| Benitrobenrizine(BNBZ) | SW1990 cells, SW1990 and SW480 xenograft models | Preclinical studies | Zheng et al. (2021) | ||

| 3PO | PFKFB3 | Glycolysis | HNSCC,tongue and gastric cancer | Preclinical and clinical studies | Li et al. (2017); Wang et al. (2020) |

| PFK158 | Gynecologic cancers, malignant pleural mesothelioma, advanced solid malignancies | Phase I clinical trials | Mondal et al. (2019); Sarkar Bhattacharya et al. (2019); Lu et al. (2017) | ||

| PFK15 | Advanced solid tumors | Phase I clinical trials | Clem et al. (2013) | ||

| KAN0438757 (KAN) | Colorectal cancer cells | Experimental | De Oliveira et al. (2021) | ||

| Shikonin | PKM2 | Glycolysis | Advanced lung cancer | Clinical trials | Guo et al. (1991) |

| Benzoxepane derivatives 10i | No accurate data | Experimental | Gao et al. (2020) | ||

| Compound 3 k (C3k) | U87MG glioma cell lines | Experimental | Park et al. (2022); | ||

| Benserazide(BEN) | Melanoma cell, SW480 cells | Experimental | Zhou et al. (2020); Li et al. (2017) | ||

| FX11 | LDHA | Glycolysis | Human lymphoma and pancreatic cancer xenografts | Preclinical studies | Valvona et al. (2016) |

| Gossypol/AT-101 | Glioma, gastric esophageal carcinoma | Preclinical and clinical studies | Caylioglu et al. (2021); Song et al. (2021) | ||

| Galloflavin | Endometrial carcinoma, breast cancer, hepatocellular carcinoma | Experimental | Han et al., (2015);Manerba et al. (2017); Farabegoli et al. (2012) | ||

| AZD3965 | MCT | Glycolysis | NHL and Burkitt’s lymphoma advanced solid tumors | Phase I clinical trials | Curtis et al. (2017) |

| AZ93 | Gastric cancer, colorectal cancer | Preclinical studies | Ždralević et al. (2018) | ||

| 7ACCs | Cervical, colorectal and breast cancer | Experimental | Draoui et al. (2014) | ||

| Syrosingopine | HL60, OPM2, HT1080 cell lines | Experimental | Buyse et al. (2022); Benjamin et al. (2018) | ||

| Enasidenib | Mutant IDH2 | 2-Hydroxyglutarate synthesis | R/R AML | Clinical practice | Martelli et al. (2020) |

| Ivosidenib | Mutant IDH1 | R/R AML, IDH1mt Cholangio Carcinoma | Clinical practice | Martelli et al. (2020); Yu et al. (2022) | |

| JPH203 | LAT1 | Glutamine | Biliary Tract Cancer, Advanced solid tumors | Phase I /II clinical trials |

Yothaisong et al. (2017); Okano et al. (2020) |

| Cetuximab | ASCT2 | Glutamine | HNSCC | Clinical practice | Lopes et al. (2021) |

| V-9302 | Colorectal cancer | Preclinical studies | Schulte et al. (2018) | ||

| GPNA | Pancreatic cancer | Preclinical studies | Wang et al. (2022) | ||

| Ag120(ivosidenib) | Colorectal cancer | Preclinical studies | Yu et al. (2022) | ||

| DON | GLS1 | Glutamine | Hodgkin lymphoma | Due to unacceptable gastrointestinal toxicity (nausea and vomiting), the use of DON in clinical therapy is limited | Rais et al. (2016) |

| DRP-104 (sirpiglenastat) | NSCLC, NHSCC, advanced solid tumors | Preclinical and clinical studies | Rais et al. (2022);Yokoyama et al. (2022) | ||

| CB-839 | Solid tumors | Clinical trials | Jiang et al. (2022) | ||

| 968 | Ovarian cancer | Preclinical studies | Yuan et al. (2016) | ||

| BPTES | MCF7 and MDA-MB231 cell lines | Preclinical studies | Nagana Gowda et al. (2018) | ||

| IPN60090 | NSCLC | Phase I clinical trials | Soth et al. (2020) | ||

| ND-646 | ACC | Lipid | lung cancer | Experimental | Li et al. (2019 |

| PF-05221304 | No accurate data | Randomized Phase 1 Study | Bergman et al. (2020) | ||