Abstract

The search for therapeutic options for lung cancer continues to advance, with rapid advances in the search for therapies to improve patient prognosis. At present, systemic chemotherapy, immune checkpoint inhibitor therapy, antiangiogenic therapy, and targeted therapy for driver gene positivity are available in the clinic. Common clinical treatments fail to achieve desired outcomes due to immunosuppression of the tumor microenvironment (TME). Tumor immune evasion is mediated by cytokines, chemokines, immune cells, and other cells such as vascular endothelial cells within the tumor immune microenvironment. Tumor-associated macrophages (TAMs) are important immune cells in the TME, inducing tumor angiogenesis, encouraging tumor cell proliferation and migration, and suppressing antitumor immune responses. Thus, TAM targeting becomes the key to lung cancer immunotherapy. This review focuses on macrophage phenotype, polarization mechanism, role in lung cancer, and advances in macrophage centric immunotherapies.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s00432-023-04740-z.

Keywords: Tumor immune microenvironment, Tumor-associated macrophages, Immunotherapy, Therapeutic target, Lung cancer

Background

Lung cancer is one of the cancers with high morbidity and mortality in the world. Since patients do not have overt clinical symptoms and signs in the early stages of their development, they usually progress to advanced disease or distant metastasis before they are detected (Deng et al. 2021). Radiation therapy in combination with molecular targeted therapy is mostly in clinical use and treatment regimens are constantly being optimized, but the prognosis for survival remains poor. Cancer immunotherapy has attracted much attention in recent years, with tumor cells having the capacity to evade the immune system to proliferate malignantly into tumors and metastasize. Immunotherapy aims to enhance the specificity and long-term memory of tissue-adaptive immunity in order to achieve durable tumor regression and eventual cure. The tumor microenvironment is complex and diverse, including blocking T-cell infiltration, reducing T-cell toxicity, recruitment of tumor-associated suppressor macrophages (TAM) and regulatory T cells (Tregs), and secretion of suppressor cytokines and metabolites. This hindrance affects the effectiveness of immunotherapy and is one of the reasons for tumor immune evasion. Thus, it is crucial to look for TME-targeted therapies to break tumor-induced immune tolerance. The tumor microenvironment is composed of myeloid cells, T cells, and macrophages, which are the abundant stromal cell types in the tumor and adjacent lung tissue, with TAMs being the most abundant immune cell in the TME. While macrophages may modulate upstream T cells for cancer immunotherapy. For this reason, the development of immune checkpoint inhibitors that antagonize the negative effects of macrophage function is critical for achieving long-lasting and durable therapeutic outcomes in refractory malignancies including lung cancer.

Overview of macrophages

TME contains a large number of cytokines, chemokines, tumor cells, and various immune cells such as T cells, NK cells, macrophages, dendritic cells, and myeloid-derived suppressor cells. Macrophages are an important component of the immune system and are found in nearly all tissues (Zhu et al. 2022). At the same time, it play a role in all stages of immunity and inflammation (Reyes et al. 2017). Macrophages engulf bacteria, viruses, and so on. The body contains sentries against invading pathogens in every tissue of the human body. They initiate an inflammatory response and collaborate with other immune cells. Cancer-associated fibroblasts (CAFs) are the most prominent component of the stroma that increases the ability of lung cancer cells to upregulate glycolysis pathways and significantly promote the progression of malignancies (Koukourakis et al. 2017; Cruz-Bermudez et al. 2019). CAFs regulate the immune response in the TME, and studies have shown that CAFs isolated from NSCLC inhibit T-cell function (Nazareth et al. 2007). Cross-presentation of CAFs with antigen eliminated the antigen specificity of CD8+ T cells in a murine lung cancer model (Bremnes et al. 2011). Macrophages comprise the bulk of the immune infiltrate in tumors and are the key cell type that links inflammation and cancer. Macrophages are broadly grouped into three populations, including monocyte-derived tumor-associated macrophages (TAM), tissue resident macrophages, and myeloid-derived suppressor cells (MDSC). Studies have shown monocytes to be the major source of TAM (Richards et al. 2013). In solid tumors, TME induces retinoic acid (RA) production by tumor cells, which differentiates intratumor monocytes toward TAMs and away from DCs through the suppression of the Irf4 transcription factor in immunostimulatory dendritic cells (DCs) (Devalaraja et al. 2020). High levels of macrophage infiltration exacerbated the poor prognosis of cancers such as breast, ovarian, cervical, Hodgkin's lymphoma, thyroid, and cutaneous melanomas. But in cancers of the colon, lung, and prostate, macrophage infiltration promoted survival and prognosis (Welsh et al. 2005; Forssell et al. 2007; Ryder et al. 2008; Steidl et al. 2010; Lan et al. 2013; Xu et al. 2013). These differences in the effect of different tumor infiltrates can be attributed to a number of intratumor factors. A number of studies in non-small cell lung cancer (NSLSC) have reported that increased infiltration of TAMs into tumor islands is associated with a good prognosis, while increased levels of TAMs in tumor stroma are associated with poor prognosis.

Plasticity of macrophages

Adaptive immunity such as damaged tissue and pathogens stimulate macrophages to initiate different patterns of gene expression, leading to macrophage formation with different activation states and functional properties (Zhu et al. 2018). The activated macrophages can be divided into two subpopulations, the classically activated M1 macrophages and the alternatively activated M2 macrophage. Differentiation of M1 macrophages occurs in the presence of Toll-like receptor (TLR) activation or in the presence of Th1 helper cytokines and is involved in the Th1 response to pathogens (Sawa-Wejksza and Kandefer-Szerszen 2018). Activation of M1 macrophages by IFN-γ, lipopolysaccharide (LPS), TNF-αor granulocyte–macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF) initiates the production of cytokines in the TME (e.g., LPS binds to Toll-like receptor 4 at the cell surface to activate interferon regulatory factors as well as nuclear factors) (Kawai and Akira 2010). The expression of major histocompatibility complex (MHC) class II is increased in activated macrophages, interleukins (IL-12), and tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNFα), generate reactive oxygen species (ROS) and nitric oxide (NO), and destroy tumor cells by recruiting pro-immunostimulatory leukocytes and phagocytosing tumor cells (Ngambenjawong et al. 2017). M1 macrophages express high levels of antigen-presenting MHC complexes and accelerate the activation of adaptive immune responses (Duan and Luo 2021). Under normal body function, M2 macrophages are associated with an extended wound healing and tissue regeneration phenotype, mediating tissue homeostasis and repair via remodeling and angiogenesis. In the presence of tissue dysfunction, however, macrophages promote the development of disease (Schultze et al. 2015). Tumor macrophages are polarized toward M2 in cancer, correlating with the tumor immunosuppressive microenvironment. More recently, it has been shown that tumor-associated lipid metabolism can create an immunosuppressive environment in which macrophages assist cancer cells in metastasis early in cancer development. In macrophages, increased expression levels of IL6, IL10, IL12, CCL5, CCL22, and CSF-1 have been shown to promote M2 polarization (Sarode et al. 2020). Of these, tumor cell-derived colony-stimulating factor (CSF1) and CC motif chemokine ligand (CCL) 2 lead to increased infiltration of macrophages into the TME. In contrast, Th2 cytokines such as IL4 and IL13 have been shown to induce M2 macrophage polarization and participate in the Th2 immune response (Zhou et al. 2021). M2 macrophages lose their ability to present antigen and are involved in debris removal, wound healing, tissue remodeling, and humoral immunity (Deng et al. 2023). M2 macrophages increase angiogenesis through adrenomedullin secretion and stimulation of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) secretion, express immunosuppressive factors such as programmed cell death ligand (PD-L1) and transforming growth factor beta (TGFβ), and is also known to be involved in cell death. Following tumor progression, M1 macrophages within the TME may progress to M2 macrophages, and chemokines such as CXCL12 may facilitate the switch from M1-like to M2-like macrophages. In the PDAC model, dual blockade of the PI3K-γ pathway and CSF-1/CSF-1R results in a switch from an M2 to M1 state (Li et al. 2020). This suggests that the pro-tumor function of TAMs can be inhibited to reverse the immunosuppressive state in the TME.

The role of TAMs in immune escape in tumor progression

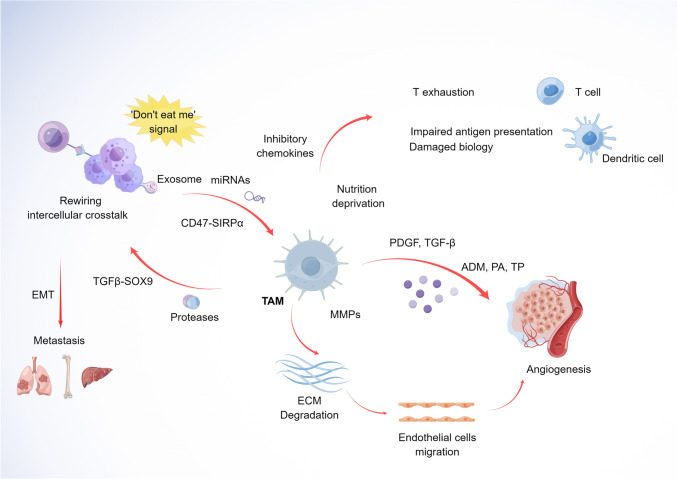

TAMs promote angiogenesis

Angiogenesis is highly dependent on tumor growth. When blood vessels are lacking, tumor cells receive adequate oxygen and nutrients from their environment by spreading, but this behavior is localized and at some point the tumor stops growing and progressively degenerates in the region of missing blood vessels. Alternatively, once it is attached to new blood vessels containing sufficient nutrients, the tumor grows rapidly and metastasizes to other sites. TAMs secrete a variety of factors that regulate angiogenesis, including adrenomedullin (ADM), the urokinase-type fibrinogen activator (PA), thymidine phosphorylase, and others. VEGF-A expression was upregulated by HIF-1α in TAMs under hypoxic conditions. Hypoxia may also promote the infiltration of TAMs into the inner regions of the tumor through the secretion of chemokines such as CC motif ligand 2 (CCL2), CCL5, and CSF-1. TAMs of the M2 type release substances such as MMP-2 and MMP-9 to degrade the extracellular matrix, promote the migration of vascular endothelium, and induce vascular neogenesis. For example, Weichand et al. demonstrated that TAM promotes lung metastasis and angiogenesis of tumor lymphatics via infiltration of S1PR1/NLRP3/IL-1β signaling into tumors in a mouse model of breast cancer (Weichand et al. 2017). Pro-angiogenic growth factors such as PDGF and TGF-β secreted by TAMs can also induce the formation of neointima.

Promotion of tumor cell invasion and metastasis

TAMs promote tumor cell invasion and migration primarily through the secretion of matrix metalloproteinases, serine proteases and histone proteases, resulting in altered cell–cell junctions and disruption of basement membranes. Tumor cells form new tumors in primary cancers after infiltrating the bloodstream and extravasating to ecologically relevant sites of metastasis, a process known as epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition (EMT). TAM secretion of TGF-β induces EMT and directs cancer cells to lose adhesion, which facilitates their entry into the bloodstream (Bonde et al. 2012). TAM promotes the invasion of cancer cells via the TGF-β/SOX9 pathway in non-small cell lung cancer. TAM-derived CCL8 also induces pseudopodia, which are plasma membrane protrusions that enhance cancer cell motility (Harney et al. 2015). The tumor-derived miR-19B-3P exosome has been shown to promote M2 macrophage polarization and secretion of the LINC00273 exostome, thereby promoting metastasis of lung adenocarcinoma through the Hippo pathway (Chen et al. 2021). In cancer cells, TAMs secrete EGF-like ligands/factors that activate the EGFR pathway, thus promoting EMT. Tumor cells treated with JWH 015 can inhibit this process, leading to downregulation of EGFR signaling, thereby reducing macrophage recruitment and attenuation of EMT (Ravi et al. 2016).

Inhibition of T-cell function and antitumor immune responses

T inhibition in macrophages under hypoxia is dependent on HIF-1α/iNOS, which itself can inhibit T-cell function. Nitric oxide and subsequently peroxynitrite can also rapidly block the proliferation of T lymphocytes (Doedens et al. 2010). Many resident macrophages may reduce T-cell activity in the context of cancer through inhibition of immune checkpoint molecules, alteration of antigen presentation, secretion of immunosuppressive cytokines (including IL-10, TGF-β, prostaglandin E2), as well as the depletion of tryptophan and arginine (Cotechini et al. 2021). TAM releases numerous other cytokines into the tumor microenvironment to promote tumor invasion such as M-CSF, MMP, and EGF (Sica et al. 2008). The chemokines released from TAMs may attract other cells into the ecological niche of the tumor, creating an immunosuppressive environment. For example, TAMs have been shown to secrete several chemokines (CCL2, CCL5, CCL20,), cytokines (IL-4, IL-10, VEGF, TGF-β) as well as enzymes (histone K, cyclooxygenases 2, arginase I, matrix metalloproteinases). Chemokines, cytokines, and enzymes can recruit naturally occurring regulatory T cells or deplete L-arginine in the tumor microenvironment to suppress T-cell activity (Wang et al. 2019). Examples include: (i) chemokines such as PGE2 and TGF-β in the tumor microenvironment are detrimental to DC maturation, disrupting the balance between innate and adaptive immunity and inhibiting active T cell and NK cells. (ii) Th2 cell-stimulated M2 macrophages produce immunosuppressive factors such as IL-10 and TGF-β in the TME of the lung, where IL-10 suppresses T-cell function by upregulating PD-L1 expression in tumor macrophages leading to immune tolerance. (iii) TAM produces an increase in arginase I during hypoxia, which depletes its L-arginine microenvironment, thus inhibiting the proliferation of T cells in the G0 and G1 phases of the cell cycle.

TAM reduces the efficacy of radiotherapy and chemotherapy

Following radiotherapy, there is an influx of bone marrow cells with the release of inflammatory factors, soluble factors (VCAM-1, CCL2), and pro-fibrotic immunosuppressive mediators (TGFβ), leading to the recruitment of macrophages and the recurrence of cancer (Mantovani and Allavena 2015). Michael Timaner et al. showed that local radiation promoted the recruitment of macrophages to tumors and increased the expression of MMP9 in these cells, suggesting a role for macrophages in promoting tumor metastasis after radiotherapy (Timaner et al. 2015; Kalbasi et al. 2017; Takahashi et al. 2020). Low-dose gamma irradiation, on the other hand, increases the recruitment of specific T cells in various cancer models and promotes normalization of the tumor vasculature. Macrophages under these conditions are more biased toward antitumor functions and negatively regulate immunosuppressive and angiogenic mediators. M2-like macrophages are also one of the factors hindering the effectiveness of chemotherapy and radiotherapy by suppressing CD8+ T-cell function, resulting in tumor progression and poor outcomes. It is possible that macrophages provide mediating chemoresistant survival factors and/or activate antiapoptotic programs in malignant cells, typically involving soluble macrophage-secreted factors, extracellular matrix deposition, or direct cell–cell interactions (Ruffell and Coussens 2015). IL-34 induced by chemotherapy enhances TAM-mediated chemoresistance in lung cancer (Baghdadi et al. 2016) As a result, chemotherapy is less effective in the treatment of TAM-induced misrepairs.

Immune checkpoint blockade is compromised by macrophages

The currently approved immune checkpoint inhibitors are monoclonal antibodies (mAb) directed against the programmed cell death protein (PD-1) pathway or the cytotoxic T lymphocyte-associated protein 4 (CTLA-4) pathway, and the immune checkpoint using antibodies directed against PD-1 or programmed cell death ligand 1 (PD-L1) blockade (ICB) has been approved for use in the treatment of non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC). PD-1 is upregulated by activated T lymphocytes to induce immune tolerance. PD-L1, a PD-1 ligand, is expressed on tumor cells, APCs, T lymphocytes and macrophages. The binding of PD-L1 on macrophages to PD-1 on T cells leads to T-cell incompetence and immune evasion by tumor cells, and thus activation of the PD-1/PD-L1 axis involves T-cell exhaustion. In addition, PD-1 expression in TAMs was negatively correlated with tumor cell phagocytosis, and blockade of PD-1/PD-L1 in vivo enhanced phagocytosis of macrophages and reduced tumor growth.

"Do not eat me" signaling

The mechanisms controlling macrophages' pro- and antitumor effects are the polarization of different macrophage phenotypes on the one hand, and the balance of stimulatory and suppressive signaling on the other. For example, CD47 is a cell surface molecule that is expressed on the surface of all human solid tumor cells. It is becoming increasingly clear that CD47 expression at the cell surface is a common mechanism by which cells protect themselves from phagocytosis (Fenalti et al. 2021; Zhao et al. 2022). Phagocytosis of cancer cells by macrophages is blocked by the binding of the signal-regulated protein alpha (SIRPα) on macrophages to CD47 on cancer cells (Barclay and Berg 2014; Liu et al. 2020). One mechanism of action is that upon macrophage attachment to CD47, the immunoreceptor tyrosine-based inhibitory motif (ITIM) of SIRPα is phosphorylated, which inhibits the accumulation of phosphotyrosine and myosin, thus preventing phagocytosis driven by actin (Vernon-Wilson et al. 2000; Tsai and Discher 2008) (See Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

A schematic illustrating the pro-tumoral effects of TAM in the tumor microenvironment. ECM extracellular matrix, EMT epithelial–mesenchymal transition (by Figdraw)

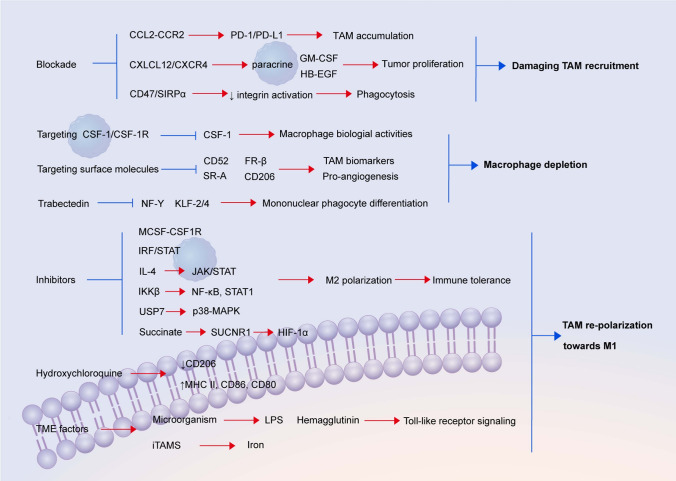

Tumor therapies targeting macrophages

As TAMs typically display a pro-M2 phenotype, they enhance numerous tumor growth processes. Therefore, lung cancer therapy can be delivered by targeting TAMs, consisting primarily of strategies that inhibit recruitment or depletion to suppress TAM infiltration into tumors and strategies that polarize macrophages for activation against the tumors (Sup Table1).

Inhibition of recruitment

Accumulation of macrophages in tumors is a consistent recruitment of monocytes from the circulation by tumor-derived factors (TDF); blocking these signals is therefore considered to be an effective strategy for reducing TAM burden at the tumor site. TDF comprises colony-stimulating factor 1 (CSF-1) and several C–C chemokine ligands. For example, blockade of the CCL2–CCR2 axis may inhibit the accumulation of TAMs in tumors (Anfray et al. 2019). The CCL2–CCR2 pathway recruits TAMs to induce immune evasion via PD-1 signaling in esophageal carcinogenesis, and therefore immune suppression of the PD-1 signaling pathway against tumor effector T cells can be halted by blockade of CCL2. Another TAM axis that is involved in monocyte recruitment and differentiation is the CXLCL12/CXCR4 axis, where macrophages can promote cancer growth through the paracrine secretion of GM-CSF/HB-EGF enhanced by CXCL12 (Rigo et al. 2010; Sanchez-Martin et al. 2011). Activation of macrophages by blocking the CD47/SIRPa axis has been shown to be effective in the treatment of various cancers (Yang et al. 2019).

Depletion of TAM

Targeting the CSF-1/CSF-1R axis has emerged as a potent target for TAM reduction in tumors, since the CSF-1 growth factor is involved in macrophage proliferation, differentiation, and survival. TAM depletion can also be accomplished by targeting surface molecules including CD52, the scavenger receptor (SR-A), the folate receptor beta (FR-β), and CD206 (Dhawan et al. 2013; Ma et al. 2021). Interfering with these targets may result in TAM depletion and thus angiogenesis inhibition. SR-A, also referred to as the macrophage scavenger receptor and differentiation 204 cluster (CD204), is highly expressed on macrophages and dendritic cells (Kelley et al. 2014). M2 macrophages express SR-A, and previous studies have shown SR-A to be involved in a variety of biological pathways and to be associated with inflammation, innate immunity, cardiovascular disease, Alzheimer's disease, bone metabolism, lung injury, and many others (Stifano and Christmann 2016; Cheng et al. 2019). CD204 can be used as an effective prognostic marker for a variety of cancers (colorectal, breast, gastric, non-small cell lung, glioma, etc.), and macrophages expressing CD204 display increased levels of IL-10 and MCP-1, promoting the accumulation of macrophages and polarization of M2 (Gudgeon et al. 2022). CD204 expression on primary mesenchymal macrophages is associated with poor lung cancer prognosis, and elevated CD204 expression can lead to metastasis, then blockade of CD204 cell activity may prevent recurrence in patients with lung cancer after surgery. Trabectedin inactivates the transcription factors NF-Y and KLF-2/4, which are important for the differentiation of mononuclear phagocytes in the TME and have thus been explored for macrophage depletion (Gurtner et al. 2017). In parallel, liposome-mediated depletion of macrophages by clodronate has also shown promise in reducing tumorigenesis.

TAM reprogramming

Reprogramming TAM converts M2 macrophages with pro-tumorigenic properties into M1 macrophages with anti-tumorigenic properties, with the CSF/CSF1R axis being the most appealing target for M2 macrophage reprogramming (Cai et al. 2021). TAM is polarized toward a pro-tumor M2 phenotype, primarily through macrophage colony-stimulating factor receptor 1 (CSF1R)-related factor 1 (M-CSF); thus, therapeutic inhibition of the CSF1R effectively repolarizes macrophages from M2 to M1. IRF/STAT signaling is the central pathway controlling macrophage M1–M2 polarization. Toll-like receptor signaling, in particular TLR4 stimulated by lipopolysaccharide and other microbial ligands, drives the preferential polarization of macrophages toward M1 polarization (Wang et al. 2014). The JAK/STAT signaling pathway also regulates macrophage phenotypic polarization. IL-4-activated STAT6 promotes M2 macrophage activation, while activation of NF-κB and STAT1 promotes M1 macrophage activation, and IKKβ is an important upstream molecule controlling NF-κB activation. Thus, synergistic delivery of STAT6 inhibitors and IKKβ siRNA for targeting M2 could effectively promote TAMs to M1 polarization (Xiao et al. 2020). The MAPK pathway is involved in TAM reprogramming and USP7 (DUB gene) is highly expressed in LUAD, but can be targeted to inhibit USP7 activation of the MAPK p38 pathway in order to reprogram TAMs to M1 macrophages, inhibit the growth of tumors, and induce local antitumor immunity in vivo (Dai et al. 2020). The presence of iron in tumors has a positive impact on the overall survival of patients with lung adenocarcinoma. Iron triggers TAM polarization toward the M1 phenotype, and induction of iron-positive macrophages fine bar in lung cancer patients could serve as a novel anticancer therapy (Costa da Silva et al. 2017). Succinate promotes the metastasis and migration of cancer cells, which can release succinate into their microenvironment and activate signaling through the succinate receptor (SUCNR1) and polarize macrophages to TAMs, promoting a mechanism of metastasis mediated by the PI3K catalytic factor 1α(HIF-1α) axis triggered by SUCNR1. Transcription of immune function genes can be efficiently regulated by extracellular succinate via SUCNR1/GPR91-mediated polarization of Gq signals to M2. Thus, inhibitors of SUCNR1 may promote TAM reprogramming (Wu et al. 2020; Trauelsen et al. 2021). Pseudomonas aeruginosa mannose-sensitive hemagglutinin has also been shown to repolarize M2 macrophages to M1 macrophages. Hydroxychloroquine reduces CD206 (M2 macrophage marker), upregulates the expression of MHCII (M1 macrophage marker), CD86, and CD80, and induces the conversion of M2 macrophages into M1 macrophages, which in turn promotes chemosensitization and exerts suppressive effects (Li et al. 2018) (See Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Therapeutic opportunities targeting TAM. TDF tumor-derived factors

Prospects for macrophage therapy in lung cancer

Immunotherapies are changing the landscape of clinical cancer care. There are three common immune cell therapies for cancer, including chimeric antigen receptor T-cell therapy, natural killer cell therapy, and macrophage therapy. Immunotherapy with CAR-T cells allows T cells to recognize a wider range of target antigens than the naturally occurring T-cell surface receptor (TCR) (Ma et al. 2019). The construction of specific chimeric antigen receptors allows T cells to be genetically transduced to express specific chimeric antigen receptors that specifically recognize the target antigens and thereby kill the target cells. CAR-T cells are primarily used for the treatment of hematologic malignancies. Thus, CAR targeting the CD19 B-cell antigen was first used successfully to treat chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) (Kalos et al. 2011). CAR-T therapy for solid tumors, however, has not progressed well, with heterogeneity, evasion of antigens, tumor infiltration, and the immunosuppressive microenvironment being considered as major factors limiting CAR-T-cell therapy for solid tumors (Sterner and Sterner 2021). Natural killer (NK) cells are cytotoxic lymphocytes of the innate immune system that can kill tumor cells through the secretion of cytokines to promote killing activity, perforin, and granzyme-mediated cytotoxicity. NK cells are still hampered in clinical practice by compromised immunosuppression and high manufacturing costs of immune cells. Macrophages are widely implicated in both intrinsic immunity and adaptive immunity, and their phenotype and function are highly plastic. Macrophages can polarize within the tumor microenvironment and influence other immune cells to participate in tumor development and targeted therapy through the secretion of a variety of factors. Macrophages have been shown to be either directly or indirectly involved in many key features of malignancy, including angiogenesis, invasiveness, metastasis, regulation of the tumor microenvironment, and resistance to therapy. Targeting TAM, immunotherapies for cancer that complement purely regulatory T cells by acting upstream of the T-cell response, such as pericyte therapy and immune checkpoint blockade, have been developed (DeNardo and Ruffell 2019). In recent years, antibodies targeting immune checkpoints, namely cytotoxic T lymphocyte-associated antigen 4 (CTLA-4) and programmed death/ligand 1 (PD-1/PD-L1), have been developed for anticancer therapy.

Also on the rise is nano-immunotherapy, which is achieved by three approaches: targeting cancer cells, targeting the tumor immune microenvironment, and targeting the peripheral immune system. Among these, nanomedicines that target the tumor immune microenvironment improve cancer immunotherapy through the use of immunosuppressive cells and by reducing the expression of immunosuppressive molecules. TAMs are targeted by cancer immune nanomedicines by blocking M2 macrophage survival or by affecting their signaling cascade, restriction of macrophage recruitment to tumors, and reprogramming of tumor promoting M2 macrophages to M1 macrophages (Ovais et al. 2019). Furthermore, nanodrugs may also enhance immune effector cells (e.g., APC) and cytotoxic T cells, both of which enhance the immune cycle of cancer (Shi and Lammers 2019). It is especially important to monitor the size of the immunotherapeutic response in subjects, as the effect of immunotherapy against macrophages varies widely in different cancers. Anujan Ramesh et al. reported a nano NO reporter (NO-NR) based on the fact that NO produced by activated macrophages in an antitumor state is a marker of M1, and it was capable of monitoring macrophage immunotherapeutics both in vivo and in vitro (Ramesh et al. 2020).

Conclusions and perspectives

Lung cancer remains a tremendous threat to human life, but the immune system's response to the disease provides new and improved therapeutic approaches to improve prognosis. Immunotherapies are now being used as a treatment option for various cancers and inflammatory diseases, and macrophages play a critical role in both inflammation and tumors. The role of macrophages in the progression of lung cancer has recently been dissected, and there is substantial evidence that TAMs acquire a pro-tumor phenotype at the time of tumor initiation, promoting angiogenesis. TAMs promote angiogenesis, tumor cell invasion, and metastasis, as well as induce T-cell dysfunction, exert antitumor immune function, and impair the efficacy of immune checkpoint blockade. Given the link between cancer cells and macrophages, extensive research has been conducted to reverse this interaction and to develop TAM-targeted therapies. Drug combinations targeting TAMs and other immunotherapeutic agents have shown promising results in initial clinical trials against various cancers, and both TAM depletion and TAM reprogramming have also improved the effectiveness of immunotherapeutics. Although CAR-T-cell therapy is limited in solid tumors due to factors such as immune suppression and heterogeneity, reprogrammed TAMs can polarize M2 macrophages to M1 macrophages, recruit T cells, and stimulate CD8+T cells for the advancement of immunotherapies. In summary, it is important to further investigate the potential of macrophages as a promising tumor-targeted therapy for antitumor responses to develop individualized therapies and improve prognosis.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Abbreviations

- TME

Tumor microenvironment

- NSCLC

Non-small cell lung cancer

- ROS

Reactive oxygen species

- TGF-β

Transforming growth factor beta

- VEGF

Vascular endothelial growth factor

- PD-1

Programmed cell death protein

- PD-L1

Programmed death ligand 1

- CSF-1

Colony-stimulating factor 1

- CLL

Chronic lymphocytic leukemia

- EMT

Epithelial–mesenchymal transition

- ICB

Immune checkpoint blockade

- TAMs

Tumor-associated macrophages

- TDF

Tumor-derived factor

- LPS

Lipopolysaccharide

Author contributions

QX and YLZ provided the direction and guidance of this manuscript. HM and ZZ wrote the whole manuscript. QH, HC, and GW made significant revisions to the manuscript. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This work has been funded with support from Nantong Science and Technology Bureau.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no potential conflicts of interest.

Ethical approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Huiyun Ma, Zhouwei Zhang and Qin Hu have contributed equally to this work.

Contributor Information

Youlang Zhou, Email: zhouyoulang@ntu.edu.cn.

Qun Xue, Email: xuequnsci@126.com.

References

- Anfray C, Ummarino A, Andon FT, Allavena P (2019) Current strategies to target tumor-associated-macrophages to improve anti-tumor immune responses. Cells 9(1):46 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baghdadi M, Wada H, Nakanishi S, Abe H, Han N, Putra WE et al (2016) Chemotherapy-induced IL34 enhances immunosuppression by tumor-associated macrophages and mediates survival of chemoresistant lung cancer cells. Cancer Res 76(20):6030–6042 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barclay AN, Van den Berg TK (2014) The interaction between signal regulatory protein alpha (SIRPalpha) and CD47: structure, function, and therapeutic target. Annu Rev Immunol 32:25–50 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonde AK, Tischler V, Kumar S, Soltermann A, Schwendener RA (2012) Intratumoral macrophages contribute to epithelial–mesenchymal transition in solid tumors. BMC Cancer 12:35 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bremnes RM, Donnem T, Al-Saad S, Al-Shibli K, Andersen S, Sirera R et al (2011) The role of tumor stroma in cancer progression and prognosis: emphasis on carcinoma-associated fibroblasts and non-small cell lung cancer. J Thorac Oncol 6(1):209–217 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cai H, Zhang Y, Wang J, Gu J (2021) Defects in macrophage reprogramming in cancer therapy: the negative impact of PD-L1/PD-1. Front Immunol 12:690869 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen J, Zhang K, Zhi Y, Wu Y, Chen B, Bai J et al (2021) Tumor-derived exosomal miR-19b-3p facilitates M2 macrophage polarization and exosomal LINC00273 secretion to promote lung adenocarcinoma metastasis via Hippo pathway. Clin Transl Med 11(9):e478 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng C, Hu Z, Cao L, Peng C, He Y (2019) The scavenger receptor SCARA1 (CD204) recognizes dead cells through spectrin. J Biol Chem 294(49):18881–18897 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cotechini T, Atallah A, Grossman A (2021) Tissue-resident and recruited macrophages in primary tumor and metastatic microenvironments: potential targets in cancer therapy. Cells 10(4):960 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cruz-Bermudez A, Laza-Briviesca R, Vicente-Blanco RJ, Garcia-Grande A, Coronado MJ, Laine-Menendez S et al (2019) Cancer-associated fibroblasts modify lung cancer metabolism involving ROS and TGF-beta signaling. Free Radic Biol Med 130:163–173 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dai X, Lu L, Deng S, Meng J, Wan C, Huang J et al (2020) USP7 targeting modulates anti-tumor immune response by reprogramming tumor-associated macrophages in lung cancer. Theranostics 10(20):9332–9347 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- da Silva MC, Breckwoldt MO, Vinchi F, Correia MP, Stojanovic A, Thielmann CM et al (2017) Iron induces anti-tumor activity in tumor-associated macrophages. Front Immunol 8:1479 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeNardo DG, Ruffell B (2019) Macrophages as regulators of tumour immunity and immunotherapy. Nat Rev Immunol 19(6):369–382 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deng P, Zhou R, Zhang J, Cao L (2021) Increased expression of KNSTRN in lung adenocarcinoma predicts poor prognosis: a bioinformatics analysis based on TCGA data. J Cancer 12(11):3239–3248 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deng L, Jian Z, Xu T, Li F, Deng H, Zhou Y et al (2023) Macrophage polarization: an important candidate regulator for lung diseases. Molecules 28(5):2379 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Devalaraja S, To TKJ, Folkert IW, Natesan R, Alam MZ, Li M et al (2020) Tumor-derived retinoic acid regulates intratumoral monocyte differentiation to promote immune suppression. Cell 180(6):1098–114.e16 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dhawan D, Ramos-Vara JA, Naughton JF, Cheng L, Low PS, Rothenbuhler R et al (2013) Targeting folate receptors to treat invasive urinary bladder cancer. Cancer Res 73(2):875–884 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doedens AL, Stockmann C, Rubinstein MP, Liao D, Zhang N, DeNardo DG et al (2010) Macrophage expression of hypoxia-inducible factor-1 alpha suppresses T-cell function and promotes tumor progression. Cancer Res 70(19):7465–7475 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duan Z, Luo Y (2021) Targeting macrophages in cancer immunotherapy. Signal Transduct Target Ther 6(1):127 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fenalti G, Villanueva N, Griffith M, Pagarigan B, Lakkaraju SK, Huang RY et al (2021) Structure of the human marker of self 5-transmembrane receptor CD47. Nat Commun 12(1):5218 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forssell J, Oberg A, Henriksson ML, Stenling R, Jung A, Palmqvist R (2007) High macrophage infiltration along the tumor front correlates with improved survival in colon cancer. Clin Cancer Res 13(5):1472–1479 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gudgeon J, Marin-Rubio JL, Trost M (2022) The role of macrophage scavenger receptor 1 (MSR1) in inflammatory disorders and cancer. Front Immunol 13:1012002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gurtner A, Manni I, Piaggio G (2017) NF-Y in cancer: impact on cell transformation of a gene essential for proliferation. Biochim Biophys Acta Gene Regul Mech 1860(5):604–616 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harney AS, Arwert EN, Entenberg D, Wang Y, Guo P, Qian BZ et al (2015) Real-time imaging reveals local, transient vascular permeability, and tumor cell intravasation stimulated by TIE2hi macrophage-derived VEGFA. Cancer Discov 5(9):932–943 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalbasi A, Komar C, Tooker GM, Liu M, Lee JW, Gladney WL et al (2017) Tumor-derived CCL2 mediates resistance to radiotherapy in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Clin Cancer Res 23(1):137–148 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalos M, Levine BL, Porter DL, Katz S, Grupp SA, Bagg A et al (2011) T cells with chimeric antigen receptors have potent antitumor effects and can establish memory in patients with advanced leukemia. Sci Transl Med 3(95):9573 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawai T, Akira S (2010) The role of pattern-recognition receptors in innate immunity: update on toll-like receptors. Nat Immunol 11(5):373–384 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelley JL, Ozment TR, Li C, Schweitzer JB, Williams DL (2014) Scavenger receptor-A (CD204): a two-edged sword in health and disease. Crit Rev Immunol 34(3):241–261 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koukourakis MI, Kalamida D, Mitrakas AG, Liousia M, Pouliliou S, Sivridis E et al (2017) Metabolic cooperation between co-cultured lung cancer cells and lung fibroblasts. Lab Investig J Tech Methods Pathol 97(11):1321–1331 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lan C, Huang X, Lin S, Huang H, Cai Q, Wan T et al (2013) Expression of M2-polarized macrophages is associated with poor prognosis for advanced epithelial ovarian cancer. Technol Cancer Res Treat 12(3):259–267 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y, Cao F, Li M, Li P, Yu Y, Xiang L et al (2018) Hydroxychloroquine induced lung cancer suppression by enhancing chemo-sensitization and promoting the transition of M2-TAMs to M1-like macrophages. J Exp Clin Cancer Res 37(1):259 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li M, Li M, Yang Y, Liu Y, Xie H, Yu Q et al (2020) Remodeling tumor immune microenvironment via targeted blockade of PI3K-gamma and CSF-1/CSF-1R pathways in tumor associated macrophages for pancreatic cancer therapy. J Control Release 321:23–35 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu J, Xavy S, Mihardja S, Chen S, Sompalli K, Feng D et al (2020) Targeting macrophage checkpoint inhibitor SIRPalpha for anticancer therapy. JCI Insight. 10.1172/jci.insight.134728 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma S, Li X, Wang X, Cheng L, Li Z, Zhang C et al (2019) Current progress in CAR-T Cell therapy for solid tumors. Int J Biol Sci 15(12):2548–2560 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma YF, Chen Y, Fang D, Huang Q, Luo Z, Qin Q et al (2021) The immune-related gene CD52 is a favorable biomarker for breast cancer prognosis. Gland Surg 10(2):780–798 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mantovani A, Allavena P (2015) The interaction of anticancer therapies with tumor-associated macrophages. J Exp Med 212(4):435–445 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nazareth MR, Broderick L, Simpson-Abelson MR, Kelleher RJ Jr, Yokota SJ, Bankert RB (2007) Characterization of human lung tumor-associated fibroblasts and their ability to modulate the activation of tumor-associated T cells. J Immunol 178(9):5552–5562 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ngambenjawong C, Gustafson HH, Pun SH (2017) Progress in tumor-associated macrophage (TAM)-targeted therapeutics. Adv Drug Deliv Rev 114:206–221 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ovais M, Guo M, Chen C (2019) Tailoring nanomaterials for targeting tumor-associated macrophages. Adv Mater 31(19):e1808303 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramesh A, Kumar S, Brouillard A, Nandi D, Kulkarni A (2020) A Nitric Oxide (NO) nanoreporter for noninvasive real-time imaging of macrophage immunotherapy. Adv Mater 32(24):e2000648 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ravi J, Elbaz M, Wani NA, Nasser MW, Ganju RK (2016) Cannabinoid receptor-2 agonist inhibits macrophage induced EMT in non-small cell lung cancer by downregulation of EGFR pathway. Mol Carcinog 55(12):2063–2076 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reyes NJ, O’Koren EG, Saban DR (2017) New insights into mononuclear phagocyte biology from the visual system. Nat Rev Immunol 17(5):322–332 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richards DM, Hettinger J, Feuerer M (2013) Monocytes and macrophages in cancer: development and functions. Cancer Microenviron 6(2):179–191 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rigo A, Gottardi M, Zamo A, Mauri P, Bonifacio M, Krampera M et al (2010) Macrophages may promote cancer growth via a GM-CSF/HB-EGF paracrine loop that is enhanced by CXCL12. Mol Cancer 9:273 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruffell B, Coussens LM (2015) Macrophages and therapeutic resistance in cancer. Cancer Cell 27(4):462–472 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryder M, Ghossein RA, Ricarte-Filho JC, Knauf JA, Fagin JA (2008) Increased density of tumor-associated macrophages is associated with decreased survival in advanced thyroid cancer. Endocr Relat Cancer 15(4):1069–1074 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanchez-Martin L, Estecha A, Samaniego R, Sanchez-Ramon S, Vega MA, Sanchez-Mateos P (2011) The chemokine CXCL12 regulates monocyte-macrophage differentiation and RUNX3 expression. Blood 117(1):88–97 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sarode P, Schaefer MB, Grimminger F, Seeger W, Savai R (2020) Macrophage and tumor cell cross-talk is fundamental for lung tumor progression: we need to talk. Front Oncol 10:324 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sawa-Wejksza K, Kandefer-Szerszen M (2018) Tumor-associated macrophages as target for antitumor therapy. Arch Immunol Ther Exp (warsz) 66(2):97–111 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schultze JL, Schmieder A, Goerdt S (2015) Macrophage activation in human diseases. Semin Immunol 27(4):249–256 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi Y, Lammers T (2019) Combining nanomedicine and immunotherapy. Acc Chem Res 52(6):1543–1554 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sica A, Allavena P, Mantovani A (2008) Cancer related inflammation: the macrophage connection. Cancer Lett 267(2):204–215 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steidl C, Lee T, Shah SP, Farinha P, Han G, Nayar T et al (2010) Tumor-associated macrophages and survival in classic Hodgkin’s lymphoma. N Engl J Med 362(10):875–885 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sterner RC, Sterner RM (2021) CAR-T cell therapy: current limitations and potential strategies. Blood Cancer J 11(4):69 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stifano G, Christmann RB (2016) Macrophage involvement in systemic sclerosis: do we need more evidence? Curr Rheumatol Rep 18(1):2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takahashi R, Ijichi H, Sano M, Miyabayashi K, Mohri D, Kim J et al (2020) Soluble VCAM-1 promotes gemcitabine resistance via macrophage infiltration and predicts therapeutic response in pancreatic cancer. Sci Rep 10(1):21194 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Timaner M, Bril R, Kaidar-Person O, Rachman-Tzemah C, Alishekevitz D, Kotsofruk R et al (2015) Dequalinium blocks macrophage-induced metastasis following local radiation. Oncotarget 6(29):27537–27554 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trauelsen M, Hiron TK, Lin D, Petersen JE, Breton B, Husted AS et al (2021) Extracellular succinate hyperpolarizes M2 macrophages through SUCNR1/GPR91-mediated Gq signaling. Cell Rep 35(11):109246 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsai RK, Discher DE (2008) Inhibition of “self” engulfment through deactivation of myosin-II at the phagocytic synapse between human cells. J Cell Biol 180(5):989–1003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vernon-Wilson EF, Kee WJ, Willis AC, Barclay AN, Simmons DL, Brown MH (2000) CD47 is a ligand for rat macrophage membrane signal regulatory protein SIRP (OX41) and human SIRPalpha 1. Eur J Immunol 30(8):2130–2137 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang N, Liang H, Zen K (2014) Molecular mechanisms that influence the macrophage m1–m2 polarization balance. Front Immunol 5:614 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang J, Li D, Cang H, Guo B (2019) Crosstalk between cancer and immune cells: role of tumor-associated macrophages in the tumor microenvironment. Cancer Med 8(10):4709–4721 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weichand B, Popp R, Dziumbla S, Mora J, Strack E, Elwakeel E et al (2017) S1PR1 on tumor-associated macrophages promotes lymphangiogenesis and metastasis via NLRP3/IL-1beta. J Exp Med 214(9):2695–2713 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Welsh TJ, Green RH, Richardson D, Waller DA, O’Byrne KJ, Bradding P (2005) Macrophage and mast-cell invasion of tumor cell islets confers a marked survival advantage in non-small-cell lung cancer. J Clin Oncol 23(35):8959–8967 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu JY, Huang TW, Hsieh YT, Wang YF, Yen CC, Lee GL et al (2020) Cancer-derived succinate promotes macrophage polarization and cancer metastasis via succinate receptor. Mol Cell 77(2):213–27.e5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiao H, Guo Y, Li B, Li X, Wang Y, Han S et al (2020) M2-Like tumor-associated macrophage-targeted codelivery of STAT6 inhibitor and IKKbeta siRNA induces M2-to-M1 repolarization for cancer immunotherapy with low immune side effects. ACS Cent Sci 6(7):1208–1222 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu J, Escamilla J, Mok S, David J, Priceman S, West B et al (2013) CSF1R signaling blockade stanches tumor-infiltrating myeloid cells and improves the efficacy of radiotherapy in prostate cancer. Cancer Res 73(9):2782–2794 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang H, Shao R, Huang H, Wang X, Rong Z, Lin Y (2019) Engineering macrophages to phagocytose cancer cells by blocking the CD47/SIRPa axis. Cancer Med 8(9):4245–4253 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao H, Song S, Ma J, Yan Z, Xie H, Feng Y et al (2022) CD47 as a promising therapeutic target in oncology. Front Immunol 13:757480 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou D, Luan J, Huang C, Li J (2021) Tumor-associated macrophages in hepatocellular carcinoma: friend or foe? Gut Liver 15(4):500–516 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu L, Jones C, Zhang G (2018) The role of phospholipase C signaling in macrophage-mediated inflammatory response. J Immunol Res 2018:5201759 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu Y, Li X, Wang L, Hong X, Yang J (2022) Metabolic reprogramming and crosstalk of cancer-related fibroblasts and immune cells in the tumor microenvironment. Front Endocrinol (lausanne) 13:988295 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.