Table 5.

How Parental Monitoring Relates to Other Commonly Studied Parenting Constructs

| Construct | Relation to the monitoring construct |

|---|---|

|

Parenting style: The parent’s constellation of attitudes toward the youth that create a global emotional climate for the parent-youth relationship (e.g., authoritative, permissive) (Darling & Steinberg, 1993) |

“Parenting style” could be a cause of or context for parental monitoring behaviors. Parenting style should not be confused with the “style” dimension of monitoring behaviors in our taxonomy, which refers to the manner in which a given monitoring behavior is performed. |

|

Parental strictness: The parent’s general tendency toward surveillance, demandingness, and supervision of the youth (Garcia et al., 2020) |

“Parental strictness” could be a cause of monitoring behaviors. In our taxonomy, parental strictness would be reflected in the style dimension: monitoring behaviors can be performed in more or less strict fashion. |

|

Parental warmth: The parent’s general tendency to show the youth acceptance and affection and to be responsive (Garcia et al., 2020) |

“Parental warmth” could be a cause of monitoring behaviors. In our taxonomy, parental warmth would be reflected in the style dimension: monitoring behaviors can be performed in a warmer or colder fashion. (Olson et al., 2023) |

|

Parent-child relationship quality: “The degree of closeness, understanding, trust, shared decision making, and caring that exists in the parent-child relationship” (Olson et al., 2023) |

“Parent-child relationship quality” could be a context for parental monitoring behaviors. In our taxonomy, parent-child relationship quality could be reflected in the style dimension: the kind of relationship a parent has with their youth may affect the fashion in which they monitor. |

|

Parental knowledge: Information the parent has about the child’s general activities, whereabouts, and company (Stattin & Kerr, 2000) |

“Parental knowledge” is not a set of behaviors, it is information a parent knows about their youth. |

|

Spending time with youth: Time when the parent is in the youth’s physical presence. |

Spending time with youth enables Type 4 monitoring behaviors, if the parent is actively observing the youth. However, parents can spend time with youth without directly observing them, which would not comprise monitoring. |

|

Helicopter parenting: Parenting behaviors that are high in control, high in warmth/support, and low on granting youth autonomy (Padilla-Walker & Nelson, 2012) |

Some “helicopter parenting” behaviors are monitoring behaviors if they are performed to gather information (e.g. asking friends for information about youth’s whereabouts). However, other helicopter parenting behaviors are not monitoring behaviors (e.g., sending the youth jobs they should apply to). |

|

Parent-youth communication: The exchange of information between the parent and the youth. |

Parent communication to the youth can sometimes be a parental monitoring behavior. Youth communication to the parent can never be a parental monitoring behavior because parental monitoring behaviors are only performed by parents. Parent-youth communication that consists of the parent asking the youth about their life and activities is a Type 1 monitoring behavior (Section 4.6.1). Parent-youth communication that consists of the parent communicating a rule designed to gather information is a Type 2 monitoring behavior. When the parent is not communicating with the goal of gathering information about the youth’s activities or life, then that parent-youth communication is not a monitoring behavior. |

|

Parental discipline: The parent delivering a negative consequence when the youth breaks a rule. |

Most “parental discipline” is not parental monitoring because the behaviors are not performed with the goal of gathering information about the youth’s life and activities. However, parental discipline to enforce a rule designed to gather information (e.g., grounding the teen for breaking curfew) would be a Type 2 monitoring behavior. |

|

Parental involvement: Involvement in the child’s life through shared activities (Essau et al., 2006) |

Some forms of “parental involvement” are Type 1 parental monitoring behaviors (e.g., asking the youth about events of their day), but others are not (e.g., planning family activities). |

|

Parental rules: A behavioral criterion for the youth that has been communicated by a caregiver to the youth. |

Setting and enforcing rules is a Type 2 monitoring behavior if the rule is intended to gather information (e.g., a rule that youth must always be reachable by phone when out of the house). Setting and enforcing rules that are not intended to gather information (e.g., a rule against drinking alcohol) do not count as monitoring behaviors. |

|

Parental control: Parents setting of rules about whether youth must seek permission or inform parents about plans and activities when leaving the house (Kerr & Stattin, 2000) |

“Parental control” is encompassed by Type 2 parental monitoring behaviors. Type 2 parental monitoring behaviors are broader than parental control because they include any behavior to set or enforce rules to gather information, rather than only about coming and going as they please. |

|

Parental solicitation: The parent asking youth and others in their life about the youth’s activities, whereabouts, and companions (Kerr & Stattin, 2000) |

“Parental solicitation” is encompassed by Type 1 parental monitoring behaviors. Type 1 parental monitoring behaviors are broader than parental solicitation; they include asking any person for information, rather than just youth, youths’ friends, and youths’ friends’ parents (e.g., teachers, neighbors). |

|

Parental snooping: The parent going through the youth’s belongings (e.g., phone, computer, diary, backpack) or space (e.g., bedroom) without the youth’s permission or knowledge (Hawk et al., 2016) |

“Parental snooping” is encompassed by Type 3 parental monitoring behavior. Type 3 parental monitoring behaviors are broader because they include the parent going through the youth’s belongings with permission or with the youth’s knowledge. In our taxonomy, the style dimension would capture differences between other Type 3 monitoring behaviors and parental snooping. |

|

Parental supervision: The parent’s observation of the youth when co-located with the youth (Coley & Hoffman, 1996) |

“Parental supervision” and Type 4 parental monitoring behaviors are identical. |

|

Positive parenting: Parenting practices that include having warm affect, nurturing a trusting relationship with the youth, nonaversive interactions, attentive involvement and guidance, positive reinforcement, and proactively promoting development. (Dishion et al., 2008) |

“Positive parenting” is a broader construct that parental monitoring is entirely encompassed by. |

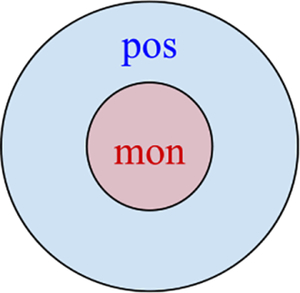

Note. Each row in the table describes the differences and overlap between the parental monitoring construct as we define it (Section 4.1) and a related construct from the broader parenting literature. Definitions of the other constructs are often inconsistent and unclear in the literature, so the first column states the definition we used for each construct when making the comparison to monitoring. In the second column, the Venn diagram shows how each other construct relates to parental monitoring. The depiction is qualitative - the amount of spatial overlap has no quantitative meaning. A Venn diagram is omitted when the nature of the other parenting construct prohibits a meaningful visual depiction of its relation to monitoring. The second column sometimes references aspects of the taxonomy we develop in Section 4 (e.g., Types 1–5 monitoring behaviors, the dimensions of monitoring behaviors)—see Sections 4.6.1 and 4.6.2 for an explanation.