Abstract

Huntingtin-associated protein 1 (HAP1) is the first identified protein whose function is affected by its abnormal interaction with mutant huntingtin (mHTT), which causes Huntington disease. However, the expression patterns of Hap1 and Htt in the rodent brain are not correlated. Here we found that the primate HAP1, unlike the rodent Hap1, is correlatively expressed with HTT in the primate brains. CRISPR/Cas9 targeting revealed that HAP1 deficiency in the developing human neurons did not affect neuronal differentiation and gene expression as seen in the mouse neurons. However, deletion of HAP1 exacerbated neurotoxicity of mutant HTT in the organotypic brain slices of adult monkeys. These findings demonstrate differential HAP1 expression and function in the mouse and primate brains, and suggest that interaction of HAP1 with mutant HTT may be involved in mutant HTT-mediated neurotoxicity in adult primate neurons.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s00018-022-04577-8.

Keywords: Huntington disease, Neurogenesis, Aging, Neurodegeneration, Primate

Introduction

Huntington’s disease (HD) is a dominantly inherited neurodegenerative disorder caused by poly-glutamine (polyQ) expansion in the N-terminal region of huntingtin (HTT). Huntingtin-associated protein1 (HAP1) was reported to interact with HTT in a glutamine length-dependent manner [1]. Both HTT and HAP1 are involved in intracellular trafficking, and abnormal interaction of mutant HTT with HAP1 affects the intracellular transport of selective molecules [2–7], suggesting that abnormal protein–protein interactions may be an important contributor to the pathogenesis of HD.

Mouse models are highly valuable for investigating the pathogenesis of diseases, especially because mouse models can be genetically modified to mimic important human diseases. Previous studies in rodent models have shown that the rodent Hap1 is not enriched in areas that are preferentially affected in HD, such as the striatum, but is highly expressed in the limbic and hypothalamic regions where neurodegeneration rarely occurs [8]. On the other hand, Htt is ubiquitously expressed in various regions of the mouse brain. The difference in the expression patterns of rodent Hap1 and Htt suggests that Hap1 may play a protective role against mutant HTT-mediated neurodegeneration, as HAP1’s expression level is low in the regions susceptible to HD, such as the cortex, striatum, and hippocampus [9–11]. However, how HAP1 is expressed in the brains of primates, such as humans and monkeys, has not been examined.

In addition, although HD is a late-manifesting neurodegenerative disorder, many studies have identified the critical role of Htt and Hap1 for early brain development in mice and suggest that neurodevelopment might be affected by mutant HTT (mHTT) [12–18]. However, whether such defects could be found in primates remains unknown. In the current study, we systematically compared the expression of HTT and HAP1 in different regions of the rodent and primate brains. We found that the expression of HAP1 in the primate brain is more correlated with HTT than that in the mouse brain. Although HAP1 deficiency in the human developing neurons did not affect neuronal differentiation and gene expression as seen in the mouse developing neurons [19], HAP1 deletion exacerbated the neuronal loss caused by mutant HTT in adult monkey neurons. These findings suggest that HAP1 is important for protecting against mutant HTT-mediated neuronal damage in the adult primate brains.

Results

Differential expression of Hap1 in the mouse and primate brains

The expression of Hap1 and Htt in the rodent brains has been characterized by different groups [8–14]. Although our early work detected the expression of HAP1 in human and monkey tissues [20, 21], the brain regional distribution of HAP1 and its relationship with HTT in the primate brain remains to be investigated. We first wanted to verify that antibodies we used could specifically recognize human HAP1 and HTT. To this end, we used knockdown strategy to examine whether antibody immunoreactivity could be reduced when endogenous HAP1 or HTT was targeted by CRISPR/Cas9. We designed human HAP1 gRNAs T2 and T3 to target exon1 of human HAP1 (Supplemental Fig. S1A, B). The human HTT gRNAs (T1 and T3) to target exon1 of human HTT were described in our previous studies [22]. DNA analysis with T7E1 digestion and sequencing revealed that human HAP1 gRNA could efficiently disrupt the HAP1 gene and generated mutations in the targeted region in cultured human embryonic kidney 293 cells (HEK293) (Supplemental Fig. S1C, D). We previously generated rabbit anti-HAP1 antibody (EM39) that can recognize human and monkey HAP1 [21, 23]. The antibody for detecting human HTT was EPR5526 that has been widely used in previous studies [24, 25]. We have tried D7F7 (CST), mAb 2166 (Millipore), and EPR5526 (Abcam) and found that only EPR5526 showed good staining for both primate and mouse HTT. Thus, we used EPR5526 to compare HTT expression in the mouse and primate brains. CRISPR/Cas9 often mediated mosaic mutations in the targeted gene, resulting in incomplete depletion of the targeted proteins. Indeed, Western blotting revealed an obvious reduction of HTT and HAP1 in HEK293 cells (Supplemental Fig. S1E, F), supporting the specific immunoreactivity of antibodies to human HTT and HAP1. It is interesting to note that reduction of HAP1 also decreased HTT (Supplemental Fig. S1E, F), suggesting that HAP1 may be important for the stability of HTT.

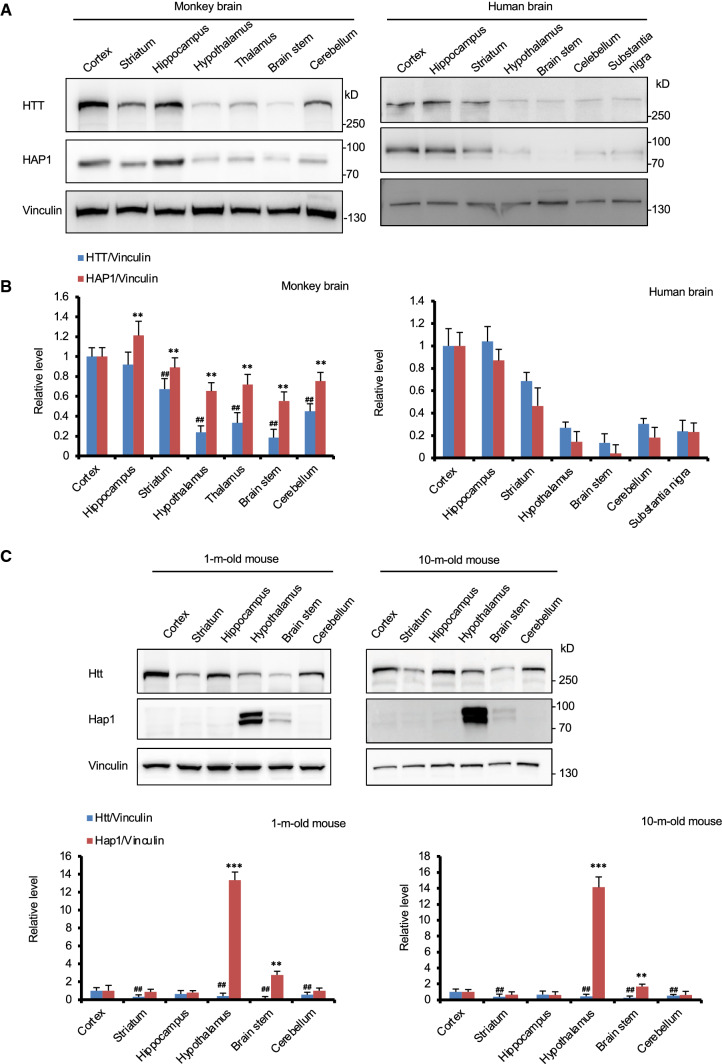

Using adult monkey brains (three 9-year-old and three 10-year-old monkeys) and postmortem human brain tissues from two individuals at 68 and 85 years of age, we examined the expression patterns of HTT and HAP1 in both monkey and human brains (Fig. 1A, B). Western blotting indicated that both HAP1 and HTT were ubiquitously expressed in different regions in the monkey and human brains (Fig. 1A). Moreover, their different expression levels in various brain regions are very similar (Fig. 1B), though the samples of these two human brains did not provide sufficient numbers for quantification analysis. We then performed Western blotting to compare the expression of Hap1 and Htt in different brain regions of mice at young (1 months) and old (10 months) ages (Fig. 1C), which are roughly equivalent to the ages of 1- and 10-year-old monkeys. To detect mouse Hap1 and Htt, we used the antibody EM77 against mouse Hap1 [1, 26] and Htt (EPR5526) antibody for western blotting analysis. The results showed that unlike Htt that was also ubiquitously expressed in different mouse brain regions, Hap1 was enriched in the hypothalamus in the mouse brain regardless of age (Fig. 1C).

Fig. 1.

Differential expression of HAP1 in the mouse and monkey brains. A Representative Western blot results of HTT and HAP1 expression in different brain regions of adult monkeys (9–10 years old) and postmortem human (68 and 85 years old) brains showing similar expression patterns of HAP1 and HTT in the monkey and human brains. B Relative levels of HTT and HAP1 (ratio to vinculin). Mean ± SEM (n = 6 for monkeys; n = 2 for human); One-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s multiple comparison test, **P < 0.01 versus HAP1 in the cortex; ##P < 0.01 versus HTT in the cortex. C Western blot analysis showing the expression of Htt and Hap1 in different brain regions of mice at 1 and 10 months of age. Htt is ubiquitously expressed in different brain regions but Hap1 is enriched in the hypothalamus regardless of age. Vinculin served as an internal control. Data are presented as mean ± SEM (n = 6). One-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s multiple comparison test, **P < 0.01 and ***P < 0.001 versus the cortex of mice at 1 month of age. **P < 0.01 and ***P < 0.001 versus HAP1 in the cortex. ## P<0.01 versus HTT in the cortex

The differential protein expression patterns of HAP1 and HTT were also supported by their mRNA expression revealed by RT-Q-PCR (Supplemental Fig. S2). RT-Q-PCR analysis revealed that both HTT mRNA and HAP1 mRNA were widely expressed in various regions in the monkey brains (Supplemental Fig. S2D–F), though the highest HTT mRNA level was seen in the cerebellum, whereas HAP1 mRNA was at the most abundant level in the hypothalamus (Supplemental Fig. S2E, F). The rodent Hap1 mRNA was almost tenfold higher in the hypothalamus than many of other regions in the mouse brain (Supplemental Fig. S2C), and the expressions of the monkey HAP1 mRNA in the hypothalamus was about 2–3 fold higher than other monkey brain regions (Supplemental Fig. S2F). Thus, Hap1 expression at both mRNA and protein levels in the hypothalamus appears to be species-dependent.

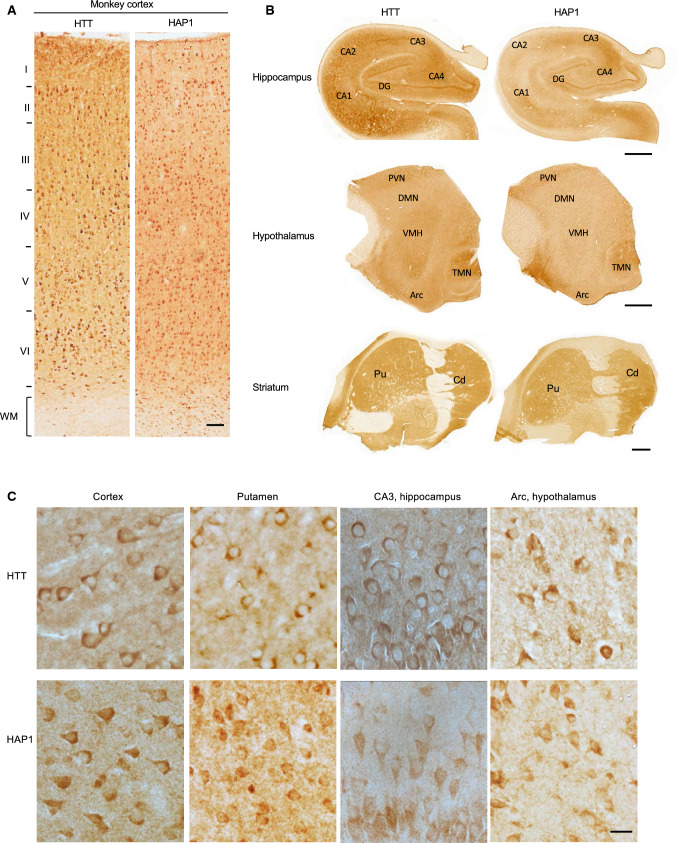

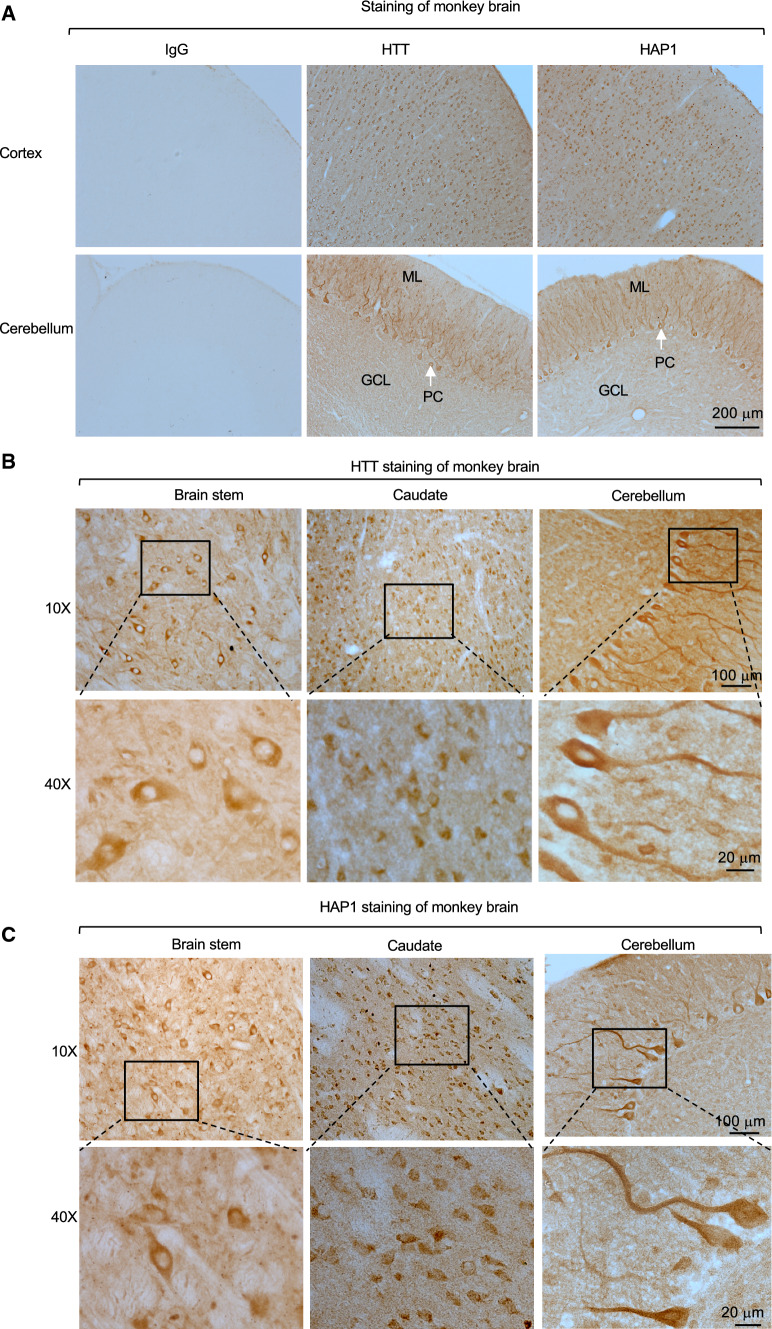

The correlative expression of HAP1 and HTT in the primate brains

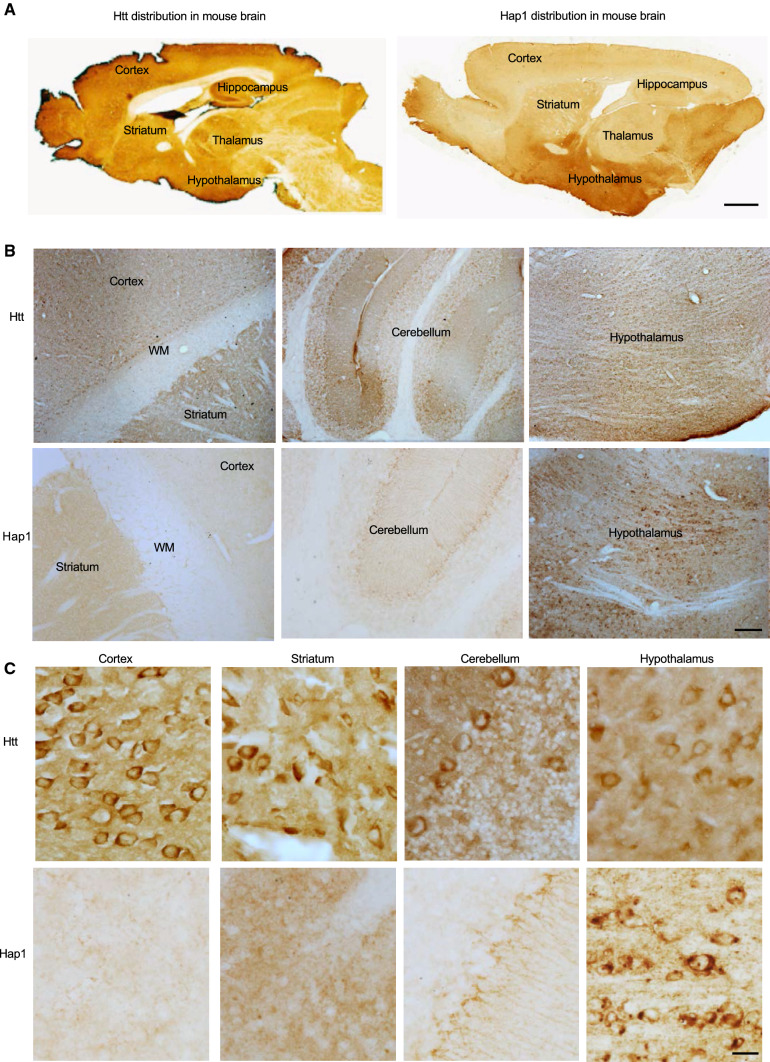

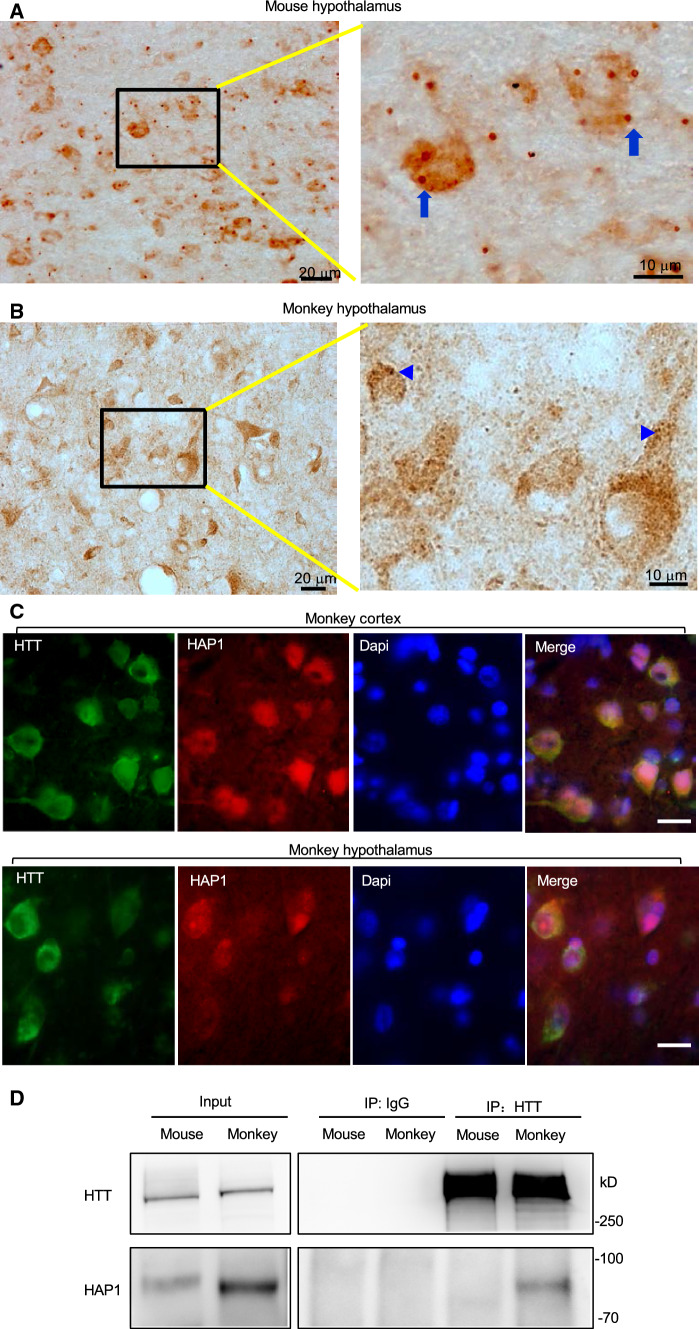

To confirm differential expression of HAP1 in the mouse and primate brains and to further explore the relationship of HAP1 and HTT in the primate brains, we performed immunohistochemical studies of the mouse and monkey brains. Consistent with western blotting results, Htt was ubiquitously expressed in various mouse brain regions, whereas Hap1 was enriched in the mouse hypothalamus (Fig. 2, Supplemental Figs. 3, 4). However, HTT and HAP1 were expressed in a similar manner in different monkey brain regions (cortex, hippocampus, striatum, hypothalamus) (Figs. 3, 4). Both HTT and HAP1 were fairly abundant in the cortex, striatum (putamen and caudate), and hippocampus (Figs. 3, 4). The immunostaining specificity was verified by omission of the primary antibody or inclusion of IgG (Fig. 4A, Supplemental Fig. 3). These results are consistent with differential levels of HAP1 and HTT in the primate brains revealed by western blotting (Fig. 1). In addition, Hap1 was very abundantly expressed in the hypothalamus in the rodent brain and exhibited as cytoplasmic puncta or “stigmoid bodies” (Fig. 5A), a special cellular structure ranged from 0.5 to 4 μm in diameter [27, 28]. Although HAP1 immuno-positive puncta were also seen in the monkey hypothalamus, most of the puncta were often small (< 1 μm in diameter) (Fig. 5B), and HAP1 expression level appeared to be higher in the arcuate nucleus and the tuberomammillary nucleus (TMN) in the monkey brains (Fig. 3B). These differences also support the notion that HAP1 is differentially expressed in the rodent and monkey brains.

Fig. 2.

Expression of Htt and Hap1 in the mouse brain. A The sagittal sections of 6-month-old mouse brain with Htt or Hap1 immunohistochemical staining showing abundant Hap1 expression in the hypothalamus and widespread distribution of Htt. Scale bar: 1 mm. B, C Low (B) and high (C) magnification micrographs of the mouse brain regions that were immunolabeled by antibodies to Htt and Hap1. Scale bar: 100 μm (B), 20 μm (C)

Fig. 3.

Expression of HTT and HAP1 in the monkey brain (cortex, hippocampus, striatum, and hypothalamus). A Low magnification micrographs of the coronal sections of the 8-year-old monkey right cerebral cortex showing widespread distribution of HTT and HAP1 in different layers (I–VI) of the prefrontal cortex. WM: white matter. Scale bar: 100 μm. B Low magnification micrographs of the monkey right brain hippocampus (coronal plane), hypothalamus (sagittal plane) and striatum (coronal plane) that were immunolabeled by antibodies to HTT and HAP1. Arc arcuate nucleus; DMN dorsomedial hypothalamic nucleus; PVN periventricular nucleus; TMN tuberomammillary nucleus; VMH ventromedial hypothalamic nucleus; Pu putamen; Cd caudate. Scale bars: 2 mm. C High magnification micrographs of the monkey brain regions that were immunolabeled by antibodies to HTT and HAP1. Scale bar: 20 μm

Fig. 4.

Expression of HTT and HAP1 in the monkey brains (cortex, brain stem, cerebellum and caudate). A Micrographs of the monkey right brain cortex and cerebellum (both in the coronal plane) that were immunolabeled by antibodies to HTT and HAP1, normal IgG as a control for primary antibodies. ML molecular layer, GCL: granular cell layer, PC Purkinje cell. B, C Representative HTT (B) and HAP1 (C) immuno-stained micrographs of the monkey right brain stem, caudate and cerebellum (all in the coronal plane)

Fig. 5.

Expression of HAP1 in the hypothalamus and its interaction with HTT. A Hap1-immunoreactive cells in the mouse hypothalamus. An enlarged image (right) of the black square region reveals clear stigmoid bodies (arrows). B HAP1 immuno-positive cells in the monkey brain hypothalamus. The enlarged image (right) of the black square region reveals smaller HAP1 positive puncta (arrowheads) are present in the monkey hypothalamic neurons. C Double Immunofluorescent labeling of the monkey cortex (layer III) and hypothalamus showing co-expression of HTT and HAP1 in the same neurons. Scale bar: 20 μm. D In vivo immunoprecipitation of HTT from the cortex tissues of mouse and monkey showing the coprecipitation of HTT and HAP1 in the monkey cortical tissues. HTT was precipitated by anti-HTT (EPR5526). Rabbit IgG served as a control

We also performed immunofluorescent double labeling of the monkey cortex and hypothalamus using antibodies to human HTT(MAB2166) and HAP1(EM39). The results verified that HTT and HAP1 were co-expressed in the same neurons (Fig. 5C). Further, by performing in vivo immunoprecipitation of HTT from the mouse and monkey brain cortex tissues, we found that HAP1 was obviously coprecipitated with HTT in the monkey cortex (Fig. 5D), consistent with the higher levels of HAP1 and HTT in the monkey cortex. Although immunoprecipitation is difficult to quantitatively assess protein–protein interaction, the lack of IgG-immuno-precipitated HAP1 and more abundant HAP1 precipitation in the monkey cortex than the mouse cortex support the idea that more HAP1 is expressed in the monkey cortex to bind HTT. Thus, the parallel expression of both HAP1 and HTT in the primate brain underscores the importance of investigating the roles of HAP1 and HTT in the primate brains.

The expression of HAP1 and HTT in mouse and human NSCs

Many studies have identified the critical roles of Htt and Hap1 in early brain development in mouse [12–18, 29]. However, the roles of HAP1 and HTT in the primate brains remain to be explored, and this issue should be addressed, given the above findings that HAP1 is differentially expressed in the rodent and primate brains. Neural stem cells (NSCs) are self-renewing, multi-potent cells capable of differentiating into the major cell types (neurons and glia) of the nervous system. The availability of human and mouse NSCs allowed us to compare the roles HAP1 and HTT in developing neurons of rodent or primate origin. We therefore cultured mouse cortical NSCs (mNSCs) and human cortical NSCs (hNSCs) as three-dimensional neurospheres proliferated from single-cell suspensions (Supplemental Fig. S5A). Both mNSCs and hNSCs expressed nestin, a neural stem cell marker protein (Supplemental Fig. S5B). They also expressed HAP1 (Supplemental Fig. S5B) and HTT (Supplemental Fig. S5C). Further, both mNSCs and hNSCs could be differentiated into neuron-specific β3-tubulin- (Tuj1-) positive cells (neuron) and glial fibrillary acidic protein- (GFAP-) positive cells (astrocyte) (Supplemental Fig. S5D).

Using Western blotting, we examined Hap1 and Htt expression in mNSCs. We observed the expression of Htt and Hap1 at different time points of neurogenesis, and their expression in neurospheres was significantly increased at 36 h after seeding (Supplemental Fig. S6A, B) and sustained from day 1–7 of differentiation (Supplemental Fig. S6C). These results support the idea that Htt and Hap1 are important to the proliferation and differentiation of mNSCs. Although the expression of GFAP appeared on day 3 and reached the highest level on day 7 of differentiation, the levels of Hap1 and Htt seemed to be decreased on day 7 during this gliogenesis period, suggesting that Hap1 and Htt are more likely to be involved in mouse neurogenesis (Supplemental Fig. S6C, D). Because hNSCs grew and developed much slower than mNSCs, we were unable to obtain enough hNSCs to perform western blotting at different time points so that the levels of HTT and HAP1 during human neurogenesis and gliogenesis remain to be investigated.

Differential roles of HAP1 in mouse and human NSCs

To investigate whether HAP1 plays different roles in mouse and human NSCs, we used CRISPR/Cas9 to deplete the expression of Hap1 and then examined the proliferation and differentiation of mNSCs. The mouse Hap1 gRNAs T2 and T3 were designed to target exon1 of the mouse Hap1 gene as described previously [30, 31]. For comparison, the mouse Htt gRNAs T1 and T3 were designed to target exon1 and 6 of the mouse Htt gene, respectively (Supplemental Fig. S7A). DNA analysis with T7E1 digestion revealed that mouse Htt or Hap1 gRNAs could efficiently disrupt the Htt or Hap1 gene in mNSCs (Supplemental Fig. S7B, C). Western blotting of mNSCs samples showed that Htt and Hap1 were markedly reduced by mouse Hap1 gRNAs and Htt gRNAs targeting (Supplemental Fig. S7D–G).

We found that Htt and Hap1 deficiency significantly decreased the diameters of mouse neurospheres when compared with the control (Supplemental Fig. S8A, B). Western blotting analysis showed that the deletion of Htt and Hap1 reduced the level of Ki67 (Supplemental Fig. S8C, D), a cellular marker for proliferation [32]. These results confirmed that loss of Htt and Hap1 impaired cell proliferation of mNSCs. We then investigated the effect of Htt and Hap1 deficiency on neural development by examining neurite length. After 5 days of spontaneous differentiation of transfected mouse NSCs, there was impairment of neuronal process elongation, revealed by β3-tubulin immunostaining, after targeting Htt and Hap1 (Supplemental Fig. S8E, F). Thus, depleting Htt or Hap1 in mNSCs resulted in similar impairment of neuronal development. However, HAP1 deletion did not affect the neuronal growth of hNSCs, whereas HTT deficiency impaired differentiation and development of hNSCs (Fig. 6A, B).

Fig. 6.

Differential effects of HAP1 and HTT knocking down on human NSCs and cultured monkey neurons. A The representative immunofluorescent labeling of β3 tubulin (green) showing neuronal processes of hNSCs transfected with HTT or HAP1 gRNA and Cas9 plasmids or transfected with the control gRNA and Cas9 plasmids. Scale bar: 20 μm. B HAP1 knocking down did not affect neurite outgrowth (arrowhead) whereas HTT deletion severely affected neurite length (arrow). Twenty images per group were randomly selected for quantification. Mean ± SEM; One-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s multiple comparison test, **P < 0.01 versus control. C Immunofluorescent imaging of cultured primary monkey neurons showing that targeting HAP1 (red and arrows) reduced HAP1 (pink) expression without significant change of neuronal processes labeled by anti-β3 tubulin (green). Scale bar: 20 μm. D GFAP (green) immunofluorescent imaging showing a GFAP-negative neuron (arrow) and a GFAP-positive glial cell (arrowhead), which expressed HAP1 gRNA-RFP, suggesting that HAP1 deletion in cultured primary monkey neurons at DIV7 did not affect neuronal and glial morphology. Scale bar: 20 μm. Nuclei were stained with Dapi (blue)

We also examined the effect of HAP1 deletion on the growth of cultured primary monkey cortical neurons. The cultured neurons at DIV 7 were transfected with Cas9 cDNA and HAP1 gRNA plasmid that also expressed RFP for identification of the targeted cells. Immunofluorescence revealed that the neuronal marker protein β3-tubulin in transfected neuron (arrow in Fig. 6C) remained the same level as untransfected neurons despite obvious reduction in HAP1 expression. The transfected neuron was GFAP-negative and showed intact and elongated neuronal process (upper panel in Fig. 6D) whereas transfected astrocytes that were both GFAP and RFP positive were not affected by HAP1 targeting (lower panel, Fig. 6D). Thus, HAP1 depletion did not affect the morphology of cultured monkey neurons, which supports the finding that HAP1 deficiency does not affect the development of hNSCs.

RNA sequencing (RNA-seq) of mouse and human MSCs after depleting HAP1 or HTT

To further verify the differential roles of HAP1 and HTT in developing rodent and primate neuronal cells, we used RNAseq analysis to examine gene expression profiling of mouse and human NSCs after depleting HAP1 or HTT by CRISPR/Cas9. The NSCs were co-transfected with Cas9 and gRNA plasmids and then grown in differentiated culture medium. The differentiated cells were collected 48 h later for RNA-seq analysis.

We found that a total of 2746 and 1430 genes were significantly differentially expressed in mNSCs with reduced Hap1 or HTT, respectively, and 1134 of these genes overlapped (Fig. 7A, B). Heat map analysis clearly showed that deletion of Hap1 or Htt altered the expression of a large number of genes (Fig. 7C). Many of these differentially expressed genes (DEGs) in Hap1-deficient mNSCs represented gene families associated with neuronal development, such as axonogenesis, synapse organization, actin filament organization, and regulation of cell morphogenesis (Fig. 7D). In Htt-deficient mNSCs, the differentially expressed genes were also involved in synapse organization, regulation of synapse organization, regulation of synapse structure or activity, and post-synapse organization (Fig. 7E). These results further indicate that loss of Hap1 and Htt in mNSCs impairs neural development and survival.

Fig. 7.

Differential transcriptomic expression in HAP1-deficient mouse NSCs. Transcriptomic analysis of mouse NSCs (A–E) after Htt and Hap1 were knocked down (KD) by CRISPR/Cas9. A Volcano plots for DEGs from Hap1 KD group vs control and Htt KD group vs control. The blue and red dots represented the significantly downregulated and upregulated genes, respectively; and the black dots represented the genes without differential expression. B Venn diagram of DEGs showing the numbers of genes that shared the similar alterations or displayed unique alterations in expression. C Heatmap for DEGs generated by Hap1 KD or Htt KD versus control. D GO enrichment classification (biological processes (BP), cellular components (CC) and molecular functions (MF)) analysis for DEGs from Hap1 KD group and control group. E GO enrichment classification analysis for DEGs from Htt KD and control

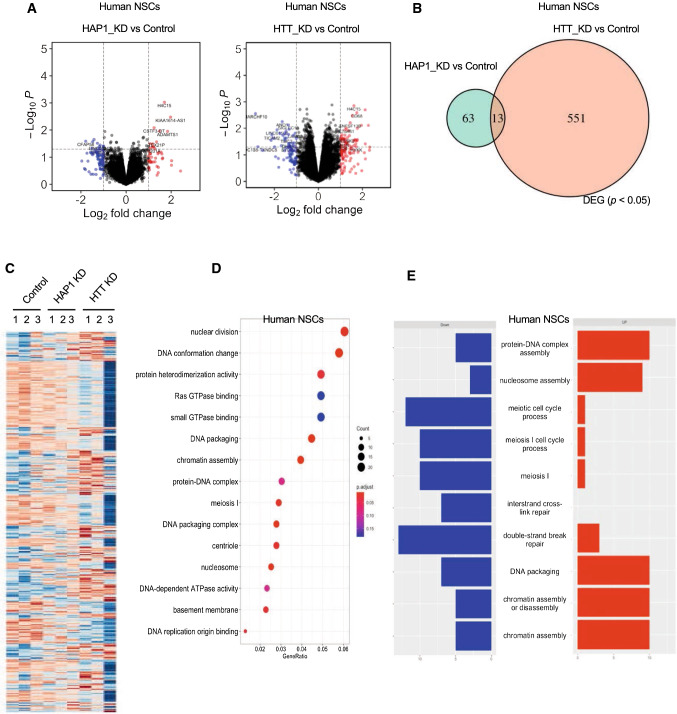

In hNSCs, however, a total of 76 and 564 genes were differentially expressed by depletion of HAP1 and HTT (Fig. 8A, B), and only 13 of them overlapped (Fig. 8B). HTT is known to play critical functions in chromatin remodeling. Therefore, knocking down HTT is expected to have a broad effect on gene transcription. Consistently, the loss of HAP1 did not cause significant gene transcriptome changes, but knocking down HTT had a widespread effect on gene transcription (Fig. 8C). GO analysis of DEGs revealed irregularities in nuclear division, DNA conformation, DNA packing, and double-strand break repair in HTT-deficient hNSCs (Fig. 8D). The top 10 significantly up- and down-regulated DEGs were involved in cell cycle and nuclear assembly signaling (Fig. 8E). These data suggest that HAP1 in the primate neurons may not be critical for early neuronal development but could be important for maintaining the function of mature neurons.

Fig. 8.

Differential transcriptomic expression in HAP1-deficient monkey NSCs. Transcriptomic analysis of HTT- and HAP1-deficient human NSCs (A–E). A Volcano plot for DEGs from HAP1 KD vs control and HTT KD vs control. B Venn diagram of DEGs showing the numbers of genes with similar or unique alteration in expression. C Heatmap for DEGs generated by HAP1 KD, HTT KD versus control. D GO enrichment analysis for DEGs from HTT KD and control groups. E The top 10 enriched pathways identified using GO pathway analysis of DEGs from HTT KD versus control

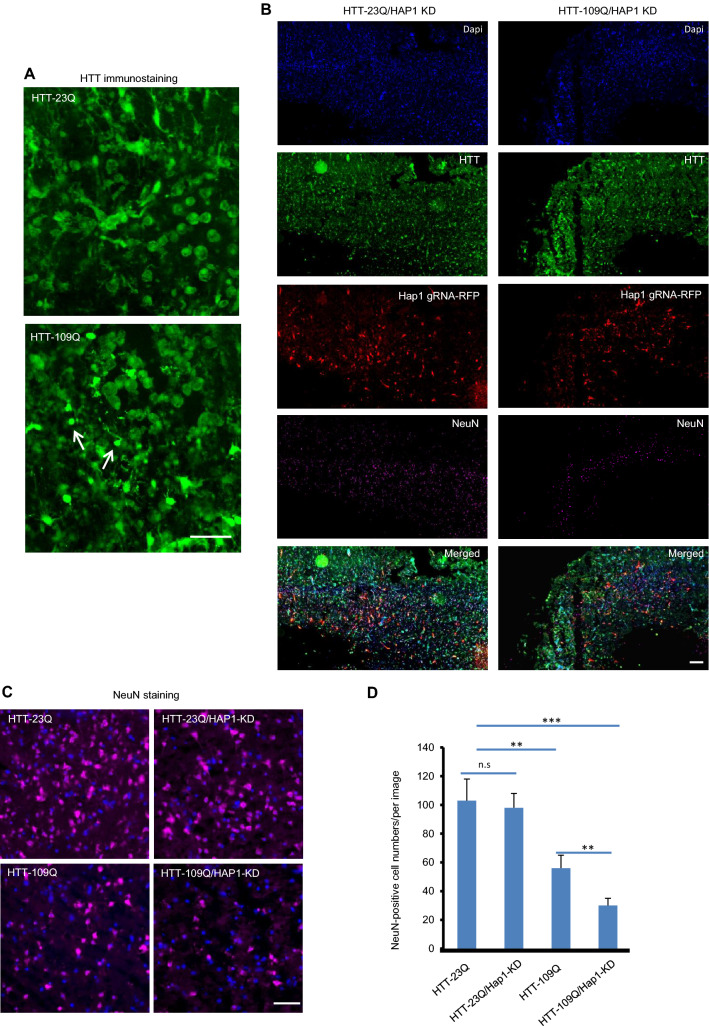

Deletion of HAP1 exacerbated mutant HTT-mediated neuronal degeneration in adult monkey neurons

To examine the role of HAP1 in adult primate neuronal cells, we employed organoid brain slices from adult monkeys, which would allow adult monkey neurons to be cultured in vitro and enable the investigation of effects of knocking down HAP1 in adult monkey neurons. The brain cortical slices were prepared from the freshly isolated brain of a 9-year-old female monkey. Our pilot studies did not reveal significant effects of knocking down HAP1 alone on neuronal cell viability. Because both HTT and HAP1 are involved in intracellular trafficking and because abnormal interaction of mutant HTT with HAP1 affects the intracellular transport of selected molecules [2–7], we focused on the role of HAP1 dysfunction on mutant HTT-mediated neuronal toxicity. To this end, we examined the effects of knocking down (KD) HAP1 on the neuronal toxicity of N-terminal (1–230 amino acids containing 109Q) mutant HTT by comparing with the control N-terminal normal HTT (1–230 amino acids containing 23Q) [33].

To achieve efficient transgene expression in cultured monkey brain slices, the above HTT and HAP1 gRNA as well as Cas9 were expressed by AAV9. We divided the brain slices into four groups: HTT-23Q (brain slices co- infected with AAV-HTT-23Q, AAV-control gRNA and AAV-Cas9), HTT-23Q/HAP1-KD (co-infected with AAV-HTT-23Q, AAV-HAP1 gRNA and AAV-Cas9), HTT-109Q (co-infected with AAV-HTT-109Q, AAV-control gRNA and AAV-Cas9), HTT-109Q/HAP1-KD (co-infected with AAV-HTT-109Q, AAV-HAP1 gRNA and AAV-Cas9). Infected brain slices were then examined 10 days later. We found that aggregated HTT was obviously increased in HTT-109Q group with more degenerated cells than HTT-23Q group (Fig. 9A).Compared with HTT-23Q/HAP1-KD group, the expression of mutant HTT (HTT-109Q) induced a loss of NeuN-positive neurons (Fig. 9B). To further analyze the effect of HAP1 knockdown on HTT-109Q-mediated neuronal degeneration, we compared the density of NeuN-positive cells after expressing HTT-23Q or HTT-109Q alone or with HAP1 knockdown. The results showed that knocking down HAP1 could augment the extent of neuronal loss caused by HTT-109Q (Fig. 9C, D). Thus, HAP1 dysfunction may promote mutant HTT-mediated neurotoxicity, supporting the notion that HAP1’s dysfunction is involved in age-related neurodegeneration in the adult brain when mutant HTT is expressed.

Fig. 9 .

HAP1 deficiency exacerbated the neurotoxicity caused by mutant HTT in monkey brain cortical organotypic culture. HTT-23Q and HTT-109Q were expressed by AAV9 and HAP1 was knocked down (KD) by expressing AAV9-HAP1 gRNA/Cas9 in cultured monkey brain cortical slices. A mEM48 immunostaining showing that aggregated HTT (arrows) were presented in HTT-109Q-expressing neurons compared with HTT-23Q-expressing neurons. Scale bar: 50 μm. B Immunostaining by mEM48 for detecting HTT, anti-RFP for reflecting gRNA expression, and anti-NeuN for labeling neuronal cells showing that the density of NeuN-positive cells (pink) is obviously decreased in the HTT-109Q/HAP1-KD group compared with the HTT-23Q/HAP1-KD group. Scale bar: 200 μm. C Immunostaining showing NeuN-positive cells in HTT-23Q, HTT-23Q/Hap1-KD, HTT-109Q, HTT-109Q/Hap1-KD groups. Scale bar: 50 μm. D Quantification of the numbers of NeuN-positive (from C) in cultured monkey cortex slices. The data were obtained by counting 20 images from 4 cultured monkey cortex slices per group. Mean ± SEM; One-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s multiple comparison test, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001

Discussion

Clinical symptoms of HD, including involuntary movements, dementia and other psychiatric disorders [34], are caused by selective neuronal loss in the striatum, hippocampus, and cerebral neocortex [9–11]. HTT, however, is not specifically restricted in the degenerated regions but is widely expressed through the entire brain in mice and humans [35, 36]. Thus, considerable efforts have been taken to identify and investigate HTT-interacting proteins, such as HAP1, which may contribute to the selective neurodegeneration in HD [37–39].

Previous studies in the rodent animals have shown that Hap1 is not enriched in the areas that are particularly affected in HD, but is preferentially expressed in the limbic and hypothalamic regions where neurodegeneration rarely occurs [8]. These regional differences in Hap1 expression lead to the hypothesis that Hap1 may play a protective role against neurodegeneration [8, 40]. However, our studies did not identify different expression patterns of HTT and HAP1 in the primate brains. Instead, we found that the regional expression pattern of HAP1 in the primate brain is consistent with that of HTT. In the primate brains, HAP1 is abundant in brain regions that also show high HTT expression, while HAP1 is low in the brain regions in which HTT is expressed at a lower level. For example, HAP1 is highly expressed in the cerebral cortex of primates, in contrast to the much lower level of Hap1 in the cerebral cortex of rodents. Consistently, HTT could be obviously coprecipitated with HAP1 in the monkey brain cortex. These results suggest that the interaction of HTT and HAP1 may be more important for the neuronal function in the primate brain, especially in those brain regions that highly express both HAP1 and HTT.

HTT is essential for development, at least in mice [13, 14, 41]. Knocking down HTT by CRISPR/Cas9 shows impaired differentiation in both developing human and mouse neurons. This finding supports the notion that HTT plays a conservative role in different species. In support of this idea, the expression patterns of HTT in the rodent and primate brains are very similar. Unlike HTT, however, HAP1 is expressed differently in the rodent and monkey brains. Knocking down HAP1 in the developing neurons from rodent and primate also yield distinct effects. Hap1 deficiency is known to affect postnatal survive and growth in mice [15, 16], which was found to be due to the impaired neurogenesis that is critical for postnatal development [17]. However, knocking down HAP1 does not appear to affect developing primate neurons. Because both HTT and HAP1 participate in intracellular transport and both proteins are expressed in the same manner in the primate brains, one possibility is that loss of HAP1 function could be compensated by HTT but HAP1 cannot replace HTT because HTT is a much larger protein that interacts with more partners than does HAP1. This possibility, however, remains to be addressed in future studies.

Given the close relationship and interaction of HAP1 and HTT in the adult primate brain, we speculated that interaction of HAP1 with mutant HTT would contribute to age-dependent neuronal dysfunction. In the current study, we demonstrate that mutant HTT caused aggregate formation and neuronal loss in cultured monkey brain slices, which allowed us to investigate the effect of HAP1 deficiency on mutant HTT-mediated toxicity in adult primate neurons. Our findings revealed that HAP1 deletion resulted in a severe neuronal degeneration in brain slices expressing mutant HTT. Thus, the involvement of HAP1 dysfunction in mutant HTT-mediated neuropathology in the primate neuronal cells supports the previous findings that mutant HTT binds HAP1 more tightly to affect cellular functions [1, 3, 6, 42, 43]. However, how the interaction of mutant HTT and HAP1 mediates neuronal dysfunction in the primate brains needs to be further studied, which would require additional animal resources and transgenic HD monkey models.

Our findings revealed differential HAP1 expression in the mouse and primates. The abundant expression of HAP1 in the primate cortex is apparently different from the low level of Hap1 in the rodent brain cortex, highlighting differential effects of HAP1 in the rodent and primate brains. This idea is also supported by differential effects of HTT and HAP1 on gene expression and differentiation of developing primate neurons as well as their interacting effects in monkey brain slices culture. Comparing the expression of HTT and HAP1 in the rodent and primate brains adds another line of evidence for the importance of investigating the expression of disease proteins and their modulators in the primate brains. Our recent studies have shown that caspase-4, which cleaves the ASL disease protein TDP-43, is selectively expressed in the primate brain [44] and that the PD protein, PINK1, is also selectively abundant in the primate brains [45]. Thus, these findings suggest that the disease proteins and their interacting proteins can be expressed differentially in different species, which may account for the selective neuronal vulnerability that may only occur in the human brain. Although different mechanisms may underline such differential expression, investigating the expression and function of disease proteins in non-human primates will provide novel mechanistic insights into disease pathogenesis. Considering that many rodent models of HD, especially HD knock-in mice, do not recapitulate the overt and selective neurodegeneration as seen in HD patients, the differential expression of HAP1 in rodents and primates could contribute to the discrepancy in neuropathology between rodents and humans and may help us to establish a more humanized mouse model to investigate HD pathogenesis.

Materials and methods

Mouse, monkey, and human tissues

Mice at Cyagen Biosciences in Guangzhou, China and the animal facility at Jinan University were used to isolate their tissues for experiments. The monkey tissues were obtained from cynomolgus monkeys that were kept at Guangdong Landao Biotechnology Co., Ltd. These cynomolgus monkeys had body injuries with healthy brain and were required by animal welfare for euthanasia. For isolating embryonic monkey brains, pregnant female monkeys at gestation day 60 were anesthetized to isolate fetuses whose brain tissues were immediately used for culturing primary neuronal cells. Guangdong Landao Biotechnology Co. Ltd is an Association for Assessment and Accreditation of Laboratory Animal Care-accredited facility. All monkey-related protocols were approved in advance by the Animal Care and Use Committee of Guangdong Landau Biotechnology Co. Ltd. This study occurred in strict compliance with the ‘‘Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals of the Institute of Laboratory Animal Science (est. 2006)’’ and ‘‘the use of non-human primates in research of the Institute of Laboratory Animal Science (est. 2006)’’ to ensure the safety of personnel and animal welfare.

Postmortem human tissues were provided by Professor Xiao-Xin Yan in the Department of Anatomy and Neurobiology, Xiangya School of Medicine, Central South University, Changsha, China. The use of postmortem human tissues was approved by the Ethics Committee of Central South University Xiangya School of Medicine. The postmortem brains were assessed for optimal histological integrity following a standard protocol proposed by the China Human Brain Banking Consortium [46, 47]. The postmortem tissues were from two individuals who died of breast cancer at 68 years of age (woman) or stroke at 85 years of age (man). Since these human tissues do not express mutant HTT, we could use them to compare the expression of normal HAP1 and HTT.

Antibodies and reagents

Mouse anti-HTT (mEM48) [21], rabbit anti-human HAP1 (EM39) [21], and guinea pig anti-Hap1 (EM77) [1, 26] have been described previously. We also used the following antibodies: Rabbit anti-Hap1 (TA306425, Origene, MD, USA), mouse anti-HTT (MAB2166, Chemicon, Temecula, CA,USA), rabbit anti-HTT (EPR5526,ab109115, Abcam, Cambrige, UK), mouse anti-Nestin (sc-23927, Santa Cruz Biotechnology, CA, USA), mouse anti-Vinculin (MAB3574, MED millipore, Billerica, MA, USA), mouse anti-tubulin β 3 (TUBB3) (801202, Biolegend, San Diego, CA,USA), rabbit anti-glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP) (ab7260, Abcam, Cambridge, UK), Rabbit anti-NeuN (ab177487, Abcam). Normal rabbit IgG (12-370, MED millipore) was used as a control for rabbit anti-HAP1 and anti-HTT. HRP-labeled secondary antibodies were donkey anti-mouse and donkey anti-mouse (Bosterbio, Wuhan, China), and donkey anti-guinea pig (Bioss, Beijing, China). Fluorescent labeled secondary antibodies were donkey anti-mouse Alexa Fluor 488 or 594, donkey anti-mouse Alexa Fluor 488 or 594, donkey anti-guinea pig Alexa Fluor488 or 594, and donkey anti-mouse Alexa Fluor 647 (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA). Guide RNA (gRNA) backbone vector and Cas9 plasmid were purchased from Addgene (px551, px552).

Cell culture

Cryopreserved human fatal cortical neural stem cells (human NSCs, A15654, Gibco-Thermo Fisher, Grand Island, NY, USA), and mouse cortical NSCs (mouse NSCs, NSC002, R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN, USA) were purchased for culturing neurospheres in complete NSC culture medium, including KnockOut DMEM/F12 (12660012, Gibco), 2% Stempro Neural Supplement (A1050801, Gibco), 2 mM GlutaMax-I supplement (A1286001, Gibco), 20 ng/mL fibroblast growth factor basic (bFGF, 3718-FB, R&D Systems) and epidermal growth factor (EGF, 236-EG, R&D Systems) plus 100 U/mL Pen-Strep (15140122, Gibco). To differentiate NSCs, NSCs were cultured on surfaces coated with Geltrex LDEV-Free hESC-qualified Reduced Growth Factor Basement Membrane Matrix (A1413201, Gibco) in differentiation medium consisting of completed NSC culture medium without bFGF and EGF. The cells were maintained at 37℃ in a 95% air/5% CO2 humidified incubator.

To culture primary monkey neurons, cortical neurons were isolated from embryonic day 60 (E60) cynomolgus macaque brains. Dissected tissues were treated with 20U/mL papain in HBSS solution for 10 min at 37 °C, triturated with 40 µm cell filter, then centrifuged at 500 × g for 5 min. Cells were plated on glass coverslips that had been precoated with 0.1 mg/mL poly-d-lysine and 1 μg/mL laminin, and grown in neurobasal (21103049, Gibco)/B27 (2%, A3582801, Gibco) medium.

Western blotting

Cells or animal tissues were homogenized in RIPA buffer [50 mM Tris, 150 mM NaCl, 0.1% SDS, 0.5% sodium deoxycholate, 1% Nonidet P-40,1 mM EDTA, and protease inhibitor cocktail (78,430, Pierce, Rockford, IL, USA) and 1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride (PMSF) (P-7626, Sigma, St Louis, MO, USA)]. Equal amounts of protein were loaded on GenScript (Nanjing, China) Tris–glycine (8%) gels for SDS–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis. Proteins transferred to nitrocellulose blots were incubated with primary antibodies in 3% bovine serum albumin/PBS overnight at 4℃. Following incubation, the nitrocellulose blots were washed, and secondary HRP-conjugated antibodies (Bosterbio) were added in 5% milk for 1 h. ECL-plus GE Healthcare (Little Chalfont, Buckinghamshire, UK) and the chemiluminescence imaging system (Clinx, Shanghai, China) were then used to reveal immunoreactive bands on the blots.

RT-RCR and Q-PCR

Total RNA was isolated using the RNAeasy kit (Qiagen, Hiden, Germany) according to manufacturers' instruction. Reverse transcriptase reaction for the generation of cDNA was performed using PrimeScript Reverse Transcriptase (Takara Bio, Shiga, Otsu, Japan). PCR was carried out using Veriti™ 96-well thermal cycler PCR system (Thermo Fisher Scintific). See Table 1 for the list of primers used.

Table 1.

qPCR primers used

| Primer | Sequence |

|---|---|

| FW-monkey-HTT | CAACCACGAGAGCACTCACT |

| REV-monkey-HTT | ATGGGAACCAAGCTGACGAG |

| FW-monkey-HAP1 | CCTACATCCGCCAGTCAAA |

| REV-monkey-HAP1 | AAGTCATCCCGCAAGTTCA |

| FW-mouse-Htt | GTCAGAATGGTGGCTGATGAGTGC |

| REV-mouse-Htt | AGCCAGCTCAGCAAACCTCCACAG |

| FW-mouse-Hap1 | ATCATTGGTGATTCGGACGCA |

| REV-mouse-Hap1 | ATTAGGACACAACGCTTCCTG |

FW forward primer, REV reverse primer.

For Q-PCR, real-time quantification with SYBR Green Supermix (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA) was carried out using the Light Cycler 96 Real-Time PCR System (Bio-Rad). Relative expression was calculated with the ΔΔCt method using hypoxanthine–guanine phosphoribosyltransferase (Hprt) to normalize.

Immunofluorescence and immunohistochemistry

Cells and tissues were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde, washed with PBS three times, permeabilized and blocked with 0.3% Triton X-100 and 3% BSA for 2 h, and then incubated with primary antibody overnight at 4 °C. For immunofluorescence, cells and tissues were washed three times with PBS and incubated with the corresponding fluorescent secondary antibody at room temperature for 2 h. Nuclei were counterstained with DAPI (Beyotime, Shanghai, China). Immunohistochemistry was performed using a VECTASTAIN ELITE ABC Universal Kit (Vector Laboratories, Peterborough, United Kingdom). Brain sections were incubated with primary antibody at 4 °C overnight followed by incubation with poly-HRP-conjugated IgG. After rinsing in PBS, sections were detected using a DAB working solution. For the control, immunostaining with IgG or without the primary antibody was performed. Brain sections were examined microscopically. For scanning, the mouse brain sagittal section and monkey brain regions were imaged using an automatized slide scanner (TissueFAXS Whole Slide Scanner; TissueGnostics, Vienna, Austria) fitted with 10X objectives. The images were viewed using TissueFAXS viewer 7.0 (TissueGnostics) and exported as tiff images.

Co-immunoprecipitation

Fresh animal brain cortical tissues were lysed in NP40 buffer (50 mM Tris pH 7.4. 50 mM NaCl, 0.1% Triton X-100, 1% NP40, and protease inhibitor cocktail Pierce 78,430 and 1 mM PMSF, Sigma P-7626). The lysate was centrifuged at 16,000×g at 4 °C for 15 min. The supernatants were precleared by incubation with an excess of protein A agarose beads (Sigma-Aldrich) at 4 °C for 2 h with gentle rocking. Supernatants (1 mg) were then collected and incubated with 2 µg rabbit anti-HTT antibody (EPR5526) at 4 °C overnight. Next, 15 μL of protein A beads was added for an additional hour to pull down the endogenous HTT. Beads were spun down and washed three times with the lysis buffer. After final wash, SDS loading buffer was added to the samples, and the immunoprecipitation products were detected by Western blotting using rabbit anti-HAP1 antibody (EM39) and mouse anti-HTT (MAB2166) antibody.

CRISPR/Cas9 targeting

To deplete HTT or HAP1 in human NSCs and mouse NSCs, we designed the following guide RNA (gRNA) using the CRISPR design tool (crispr.mit.edu): human HTT gRNA sequences T1 (5ʹ-GGC CTT CAT CAG CTT TTC CA-3ʹ, PAM:GGG) and T3 (5ʹ-GGC TGA GGA AGC TGA GGA GG-3ʹ, PAM:CGG) for targeting exon 1 of human HTT gene [22]; mouse Htt gRNA sequences T1 (5ʹ-AAC CCT GGA AAA GCT GAT GA-3ʹ, PAM:AGG) for targeting exon 1 of mouse Htt gene (mouse Htt); T3 (5ʹ-TGC AGC TGT TCC TAA AAT TA, PAM:TGG) for targeting exon 6 of mouse Htt; human HAP1 gRNA T2 (5ʹ-GGA CCC GCT TCG TAT TCC AA, PAM:GGG) and T3 (5ʹ-AAG ACG CCA GCC GCC TAC GT, PAM:TGG) for targeting exon 1 of the human HAP1 gene; mouse Hap1 gRNA T2 (5ʹ-CTC CGG CCG ATG TAC GCG GC-3ʹ, PAM: TGG) and T3 (5ʹ-GCC GCG TAC ATC GGC CGG AG-3ʹ, PAM: AGG) for targeting exon 1 of the mouse Hap1 gene [30, 31]. The gRNA was expressed under the U6 promoter in an adeno-associated virus (AAV) vector that also expressed red fluorescent protein (RFP) driven by the CMV promoter (AAV-U6-Hap1 gRNA/CMV-RFP), and Cas9 was expressed in another AAV vector under the CMV promoter (AAV-CMV-Cas9). Mouse NSCs and human NSCs were co-transfected with Cas9 and HTT or HAP1 gRNA plasmids using Amaxa Mouse NSC Nucleofector Kit (VPG-1004, Amaxa Biosystems, Lonza Cologne GmbH, Köln, Germany) in the Nucleofector™ 2b Device (Lonza, Basel, Switzerland) to delete HTT or HAP1. Cells transfected with the control gRNA (ACC GGA AGA GCG ACC TCT TCT) [22] and Cas9 plasmids were used as a control. After 48 h, western blotting was used to examine the effect of removing HTT or HAP1.

We also designed monkey HAP1 gRNA sequences T1 (5ʹ-TGCATTCTCGGCCATCCAAG-3ʹ, PAM:GGG) and T2 (5ʹ-GGGCCCGCTTCGTATTCCAA-3ʹ, PAM:GGG) targeting exon 1 of the monkey HAP1 gene. Using Nucleofector™ 2b Device, monkey HAP1 gRNA/Cas9 or control gRNA/Cas9 plasmids were transfected in cultured primary monkey cortical neurons. Seven days after transfection, immunofluorescence labeling with EM39 was used to examine the effect of removing HAP1.

Organotypic monkey brain slice culture and AAV viral infection

The brain cortex of a female monkey at age of 9 years was carefully dissected on ice, directly transferred into ice-cold artificial cerebrospinal fluid (ACSF) (SL6630, Coolaber, Beijing, China) equilibrated with carbogen (95% O2, 5% CO2). The tissues were cut to generate brain slices at 300 μm thickness using a Leica VT1200S vibrating blade microtome (Leica, Wetzlar, Germany). The slices were then transferred onto 30 mm Millicell membrane inserts (0.4 μm; Millipore, Bedford, MA, USA) and kept in 6-well cell culture plate containing 1.5 mL media (Neurobasal/DMEM 1:1, 5% Fetal bovine serum, 5% horse serum, 1% N2, 2% B27, 2 mM L-Glutamax, 5 ng/mL GDNF, 100 U/mL Pen-Strep; all from Gibco). The plates were incubated at 37 °C in a 5% CO2 humidified incubator. The medium was replaced with fresh medium 3 times each week. After 6 h of culture, virus infection was carried out according to experimental needs. The viral vectors used were AAV9-Syn-HTT 23Q-GFP and AAV9-Syn-HTT 109Q-GFP that express N-terminal HTT (1–230 amino acids) with 23Q or 109Q [33, 48], AAV9-U6-monkey HAP1 gRNA/CMV-RFP, and AAV9-CMV-Cas9. These viral vectors had been packaged to generate purified viruses. The genomic titer of purified viruses was approximate 1013 vg/ml determined by PCR method.

To examine the effect of knocking down HAP1 on mutant HTT-mediated neurotoxicity, cultured monkey brain slices were divided into following different groups: HTT-23Q (each brain slice infected with 1 µL AAV9-HTT 23Q-GFP, 1 µL AAV9-control gRNA-RFP and 3 µL AAV9-Cas9), HTT-109Q (each brain slice infected with 1 µL AAV9-HTT 109Q-GFP, 1 µL AAV9-control gRNA-RFP and 3 µL AAV9-Cas9), HTT-23Q/HAP1 gRNA (each brain slice infected with 1 µL AAV9-HTT 23Q-GFP, 1 µL AAV9-monkey HAP1 gRNA-RFP and 3 µL AAV9-Cas9), HTT-109Q/HAP1 gRNA (each brain slice infected with 1 µL AAV9-HTT 109Q-GFP, 1 µL AAV9-monkey HAP1 gRNA-RFP and 3 µL AAV-Cas9). These viruses were diluted in culture medium and then added to the brain cortical slices. After 10 days of viral infection, immunofluorescent staining was performed to examine neuronal numbers and morphology.

RNA-seq analysis

Mouse NSCs were divided into 3 groups: Hap1 gRNA (transfected with mouse Hap1 gRNA-RFP and Cas9), Htt gRNA (transfected with mouse Htt gRNA-RFP and Cas9) and control group (transfected with control gRNA-RFP and Cas9). Human NSCs were also divided into 3 groups: HAP1 gRNA (transfected with human HAP1 gRNA-RFP and -Cas9), HTT gRNA (transfected with human HTT gRNA-RFP and Cas9) and control group (transfected with control gRNA-RFP and -Cas9). Three samples in each group were examined. The NSCs were grown in differentiated culture medium. Total RNAs from NSCs were collected 48 h after viral infection. cDNA libraries construction and sequencing were performed by Novogene Co., Ltd (Beijing, China). RNA-seq raw data were produced through paired-end sequence method on llumina HiSeq 2,500 platform. For RNA-seq analysis, gene expression levels were quantified using Salmon (ver 1.5.1) [49] with quasi-mapping method. The batch effects among different samples were removed through ComBat function of “sva” R packages (ver 3.42.0). Expression profiles and differentially expressed genes were analyzed using edgeR package [50–52]. Volcano plots and heatmap were painted with “EnhancedVolcano” (ver 1.12.0) and heatmap.2 function of “gplots” (ver 3.1.1) R packages respectively. “ClusterProflier” (Ver 3.10.1) package was used to analyze GO pathway and plot bubble diagram [53]. All above analyses and plotting were performed on RStudio (ver 1.2.5019).

Statistical analysis

To obtain the gel, blot, or micrograph results, more than three independent experiments were done, and the representative results were shown in figures. Results are presented as mean ± SEM. Statistical significance was assessed using the two-tailed Student’s t test for comparing if there were only two groups. When analyzing multiple groups, we used one-way ANOVA or two-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s multiple comparisons test to determine statistical significance. All statistical analyses were conducted using GraphPad Prism 7 (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA, USA). A significant level was considered with p value < 0.05.

For western blotting, at least three independent experiments were performed, and the ratios of immunoreaction intensity of interesting bands to the loading controls were quantified via densitometry.

For quantitative analysis of immunocytochemistry results, at least 20 images per group were randomly selected for quantification. Positive cells per field were counted manually to generate mean and SE. Quantification of neurosphere diameter and neurite length was measured using ImageJ software.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

We thank Professor Xiao-Xin Yan at Xiangya School of Medicine, Central South University, Changsha, China for providing human postmortem brain tissues, Yuefeng Li at Guangdong Landao Biotechnology Co. Ltd for animal care and experiment. This work was supported by The National Natural Science Foundation of China (81830032, 82071421, 31872779, 81901289), Guangzhou Key Research Program on Brain Science (202007030008), Department of Science and Technology of Guangdong Province (2021ZT09Y007; 2020B121201006; 2018B030337001). XC was funded by Science and Technology Research Project of Education Department of Hubei Province (B2020020). This study was supported by the high performance public computing service platform of Jinan University.

Author contributions

SL and X-JL designed experiments. XC performed all the experiments with the help of YS. LC performed RNA-seq data analysis. X-SC conducted monkey cortical neurons culture. MP conducted organotypic monkey brain slice culture. YZ and QW aided in molecular biological experiments. WY, PY, DH, XG, SY, YZ and S Yan provided important advice, reagents, and experimental samples. XC, X-J L and SL wrote the paper.

Funding

This research was funded by National Natural Science Foundation of China, Grant numbers [82071421, 81830032, 31872779].

Data availability

The raw data from this publication have been deposited. The RNA sequencing data that support the findings of this study are available in NCBI’s sequence read archive (SRA) database through Bioproject Accession number: PRJNA796166 (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/bioproject/PRJNA796166/).

Declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Xiao-Jiang Li, Email: xjli33@jnu.edu.cn.

Shihua Li, Email: lishihuaLIS@jnu.edu.cn.

References

- 1.Li XJ, Li SH, Sharp AH et al (1995) A huntingtin-associated protein enriched in brain with implications for pathology. Nature 378:398–402. 10.1038/378398a0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gauthier LR, Charrin BC, Borrell-Pagès M et al (2004) Huntingtin controls neurotrophic support and survival of neurons by enhancing BDNF vesicular transport along microtubules. Cell 118:127–138. 10.1016/j.cell.2004.06.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Twelvetrees AE, Yuen EY, Arancibia-Carcamo IL et al (2010) Delivery of GABAARs to synapses is mediated by HAP1-KIF5 and disrupted by mutant huntingtin. Neuron 65:53–65. 10.1016/j.neuron.2009.12.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Keryer G, Pineda JR, Liot G et al (2011) Ciliogenesis is regulated by a huntingtin-HAP1-PCM1 pathway and is altered in Huntington disease. J Clin Invest 121:4372–4382. 10.1172/jci57552 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Roux JC, Zala D, Panayotis N et al (2012) Modification of Mecp2 dosage alters axonal transport through the Huntingtin/Hap1 pathway. Neurobiol Dis 45:786–795. 10.1016/j.nbd.2011.11.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wong YC, Holzbaur EL (2014) The regulation of autophagosome dynamics by huntingtin and HAP1 is disrupted by expression of mutant huntingtin, leading to defective cargo degradation. J Neurosci 34:1293–1305. 10.1523/jneurosci.1870-13.2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mackenzie KD, Duffield MD, Peiris H et al (2014) Huntingtin-associated protein 1 regulates exocytosis, vesicle docking, readily releasable pool size and fusion pore stability in mouse chromaffin cells. J Physiol 592:1505–1518. 10.1113/jphysiol.2013.268342 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fujinaga R, Kawano J, Matsuzaki Y et al (2004) Neuroanatomical distribution of Huntingtin-associated protein 1-mRNA in the male mouse brain. J Comp Neurol 478:88–109. 10.1002/cne.20277 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hedreen JC, Folstein SE (1995) Early loss of neostriatal striosome neurons in Huntington’s disease. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol 54:105–120. 10.1097/00005072-199501000-00013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dom R, Malfroid M, Baro F (1976) Neuropathology of Huntington’s chorea. studies of the ventrobasal complex of the thalamus. Neurology 26:64–68. 10.1212/wnl.26.1.64 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Murphy KP, Carter RJ, Lione LA et al (2000) Abnormal synaptic plasticity and impaired spatial cognition in mice transgenic for exon 1 of the human Huntington’s disease mutation. J Neurosci 20:5115–5123. 10.1523/jneurosci.20-13-05115.2000 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nasir J, Floresco SB, O’Kusky JR et al (1995) Targeted disruption of the Huntington’s disease gene results in embryonic lethality and behavioral and morphological changes in heterozygotes. Cell 81:811–823. 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90542-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Duyao MP, Auerbach AB, Ryan A et al (1995) Inactivation of the mouse Huntington’s disease gene homolog Hdh. Science 269:407–410. 10.1126/science.7618107 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zeitlin S, Liu JP, Chapman DL et al (1995) Increased apoptosis and early embryonic lethality in mice nullizygous for the Huntington’s disease gene homologue. Nat Genet 11:155–163. 10.1038/ng1095-155 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chan EY, Nasir J, Gutekunst CA et al (2002) Targeted disruption of Huntingtin-associated protein-1 (Hap1) results in postnatal death due to depressed feeding behavior. Hum Mol Genet 11:945–959. 10.1093/hmg/11.8.945 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Li SH, Yu ZX, Li CL et al (2003) Lack of huntingtin-associated protein-1 causes neuronal death resembling hypothalamic degeneration in Huntington’s disease. J Neurosci 23:6956–6964. 10.1523/jneurosci.23-17-06956.2003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Xiang J, Yang H, Zhao T et al (2014) Huntingtin-associated protein 1 regulates postnatal neurogenesis and neurotrophin receptor sorting. J Clin Invest 124:85–98. 10.1172/jci69206 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sheng G, Chang GQ, Lin JY et al (2006) Hypothalamic huntingtin-associated protein 1 as a mediator of feeding behavior. Nat Med 12:526–533. 10.1038/nm1382 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Xiang J, Yan S, Li SH et al (2015) Postnatal loss of hap1 reduces hippocampal neurogenesis and causes adult depressive-like behavior in mice. PLoS Genet 11:e1005175. 10.1371/journal.pgen.1005175 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Li XJ, Sharp AH, Li SH et al (1996) Huntingtin-associated protein (HAP1): discrete neuronal localizations in the brain resemble those of neuronal nitric oxide synthase. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 93:4839–4844. 10.1073/pnas.93.10.4839 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Li SH, Hosseini SH, Gutekunst CA et al (1998) A human HAP1 homologue. Cloning, expression, and interaction with huntingtin. J Biol Chem 273:19220–19227. 10.1074/jbc.273.30.19220 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yang S, Chang R, Yang H et al (2017) CRISPR/Cas9-mediated gene editing ameliorates neurotoxicity in mouse model of Huntington’s disease. J Clin Invest 127:2719–2724. 10.1172/jci92087 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Li T, Li S, Gao X et al (2019) Expression and localization of Huntingtin-Associated Protein 1 (HAP1) in the human digestive system. Dig Dis Sci 64:1486–1492. 10.1007/s10620-018-5425-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Evers MM, Schut MH, Pepers BA et al (2015) Making (anti-) sense out of huntingtin levels in Huntington disease. Mol Neurodegener 10:21. 10.1186/s13024-015-0018-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Vigont VA, Grekhnev DA, Lebedeva OS et al (2021) STIM2 mediates excessive store-operated calcium entry in patient-specific iPSC-derived neurons modeling a juvenile form of Huntington’s disease. Front Cell Dev Biol 9:625231. 10.3389/fcell.2021.625231 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Li SH, Li H, Torre ER et al (2000) Expression of huntingtin-associated protein-1 in neuronal cells implicates a role in neuritic growth. Mol Cell Neurosci 16:168–183. 10.1006/mcne.2000.0858 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gutekunst CA, Li SH, Yi H et al (1998) The cellular and subcellular localization of huntingtin-associated protein 1 (HAP1): comparison with huntingtin in rat and human. J Neurosci 18:7674–7686. 10.1523/jneurosci.18-19-07674.1998 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Li SH, Gutekunst CA, Hersch SM et al (1998) Association of HAP1 isoforms with a unique cytoplasmic structure. J Neurochem 71:2178–2185. 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1998.71052178.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nguyen GD, Gokhan S, Molero AE et al (2013) Selective roles of normal and mutant huntingtin in neural induction and early neurogenesis. PLoS ONE 8:e64368. 10.1371/journal.pone.0064368 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chen X, Xin N, Pan Y et al (2020) Huntingtin-associated protein 1 in mouse hypothalamus stabilizes glucocorticoid receptor in stress response. Front Cell Neurosci 14:125. 10.3389/fncel.2020.00125 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Liu Q, Cheng S, Yang H et al (2020) Loss of Hap1 selectively promotes striatal degeneration in Huntington disease mice. Proc Natl Acad USA 117:20265–20273. 10.1073/pnas.2002283117 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Scholzen T, Gerdes J (2000) The Ki-67 protein: from the known and the unknown. J Cell Physiol 182:311–322. 10.1002/(sici)1097-4652(200003)182:3%3c311::aid-jcp1%3e3.0.co;2-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zhao T, Hong Y, Li S et al (2016) Compartment-dependent degradation of mutant huntingtin accounts for its preferential accumulation in neuronal processes. J Neurosci 36:8317–8328. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0806-16.2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sun YM, Zhang YB, Wu ZY (2017) Huntington’s disease: relationship between phenotype and genotype. Mol Neurobiol 54:342–348. 10.1007/s12035-015-9662-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bhide PG, Day M, Sapp E et al (1996) Expression of normal and mutant huntingtin in the developing brain. J Neurosci 16:5523–5535. 10.1523/jneurosci.16-17-05523.1996 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Li SH, Schilling G, Young WS 3rd et al (1993) Huntington’s disease gene (IT15) is widely expressed in human and rat tissues. Neuron 11:985–993. 10.1016/0896-6273(93)90127-d [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Harjes P, Wanker EE (2003) The hunt for huntingtin function: interaction partners tell many different stories. Trends Biochem Sci 28:425–433. 10.1016/s0968-0004(03)00168-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Li SH, Li XJ (2004) Huntingtin-protein interactions and the pathogenesis of Huntington’s disease. Trends Genet 20:146–154. 10.1016/j.tig.2004.01.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Borrell-Pagès M, Zala D, Humbert S et al (2006) Huntington’s disease: from huntingtin function and dysfunction to therapeutic strategies. Cell Mol Life Sci 63:2642–2660. 10.1007/s00018-006-6242-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wroblewski G, Islam MN, Yanai A et al (2018) Distribution of HAP1-immunoreactive cells in the retrosplenial-retrohippocampal area of adult rat brain and its application to a refined neuroanatomical understanding of the region. Neuroscience 394:109–126. 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2018.10.029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Reiner A, Dragatsis I, Zeitlin S et al (2003) Wild-type huntingtin plays a role in brain development and neuronal survival. Mol Neurobiol 28:259–276. 10.1385/mn:28:3:259 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Caviston JP, Holzbaur EL (2009) Huntingtin as an essential integrator of intracellular vesicular trafficking. Trends Cell Biol 19:147–155. 10.1016/j.tcb.2009.01.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Rong J, Li SH, Li XJ (2007) Regulation of intracellular HAP1 trafficking. J Neurosci Res 85:3025–3029. 10.1002/jnr.21326 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Yin P, Guo X, Yang W et al (2019) Caspase-4 mediates cytoplasmic accumulation of TDP-43 in the primate brains. Acta Neuropathol 137:919–937. 10.1007/s00401-019-01979-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Yang W, Guo X, Tu Z et al (2022) PINK1 kinase dysfunction triggers neurodegeneration in the primate brain without impacting mitochondrial homeostasis. Protein Cell 13:26–46. 10.1007/s13238-021-00888-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Yan XX, Ma C, Bao AM et al (2015) Brain banking as a cornerstone of neuroscience in China. Lancet Neurol 14:136. 10.1016/s1474-4422(14)70259-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Qiu W, Zhang H, Bao A et al (2019) Standardized operational protocol for human brain banking in China. Neurosci Bull 35:270–276. 10.1007/s12264-018-0306-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Zhang XY, Li J, Li CJ et al (2021) Differential development and electrophysiological activity in cultured cortical neurons from the mouse and cynomolgus monkey. Neural Regen Res 16:2446–2452. 10.4103/1673-5374.313056 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Patro R, Duggal G, Love MI et al (2017) Salmon provides fast and bias-aware quantification of transcript expression. Nat Methods 14:417–419. 10.1038/nmeth.4197 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Robinson MD, McCarthy DJ, Smyth GK (2010) edgeR: a bioconductor package for differential expression analysis of digital gene expression data. Bioinformatics 26:139–140. 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp616 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.McCarthy DJ, Chen Y, Smyth GK (2012) Differential expression analysis of multifactor RNA-Seq experiments with respect to biological variation. Nucleic Acids Res 40:4288–4297. 10.1093/nar/gks042 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Chen Y, Lun AT, Smyth GK (2016) From reads to genes to pathways: differential expression analysis of RNA-Seq experiments using Rsubread and the edgeR quasi-likelihood pipeline. F1000Res 5:1438. 10.12688/f1000research.8987.2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Yu G, Wang LG, Han Y et al (2012) clusterProfiler: an R package for comparing biological themes among gene clusters. OMICS 16:284–287. 10.1089/omi.2011.0118 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The raw data from this publication have been deposited. The RNA sequencing data that support the findings of this study are available in NCBI’s sequence read archive (SRA) database through Bioproject Accession number: PRJNA796166 (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/bioproject/PRJNA796166/).