Abstract

Type 1 diabetes is a T-cell–mediated chronic disease characterized by the autoimmune destruction of pancreatic insulin-producing β cells and complete insulin deficiency. It is the result of a complex interrelation of genetic and environmental factors, most of which have yet to be identified. Simultaneous identification of these genetic factors, through use of unphased genotype data, has received increasing attention in the past few years. Several approaches have been described, such as the modified transmission/disequilibrium test procedure, the conditional extended transmission/disequilibrium test, and the stepwise logistic-regression procedure. These approaches are limited either by being restricted to family data or by ignoring so-called “haplotype interactions” between alleles. To overcome this limit, the present study provides a general method to identify, on the basis of unphased genotype data, the haplotype blocks that interact to define the risk for a complex disease. The principle underpinning the proposal is minimal entropy. The performance of our procedure is illustrated for both simulated and real data. In particular, for a set of Dutch type 1 diabetes data, our procedure suggests some novel evidence of the interactions between and within haplotype blocks that are across chromosomes 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 11, 12, 15, 16, 17, 19, and 21. The results demonstrate that, by considering interactions between potential disease haplotype blocks, we may succeed in identifying disease-predisposing genetic variants that might otherwise have remained undetected.

Introduction

Insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus (IDDM [MIM 222100]), or type 1 diabetes, is a common chronic disease characterized by autoimmune destruction of pancreatic β cells and complete insulin deficiency (Cordell and Todd 1995; Schranz and Lernmark 1998; Friday et al. 1999). The importance of some genetic factors for the etiology of type 1 diabetes, such as human leukocyte antigen (HLA), has been established unequivocally, although their precise mechanism has not been identified. Evidence that the immune system and apoptosis play a role is accumulating. Both processes contribute to the deterioration of β cells in the islets of Langerhans in the pancreas. Despite this information, no definite genetic cause can be determined in most patients, not even in the presence of a positive family history. In this article, we present a method, for testing the influence of haplotype interactions on developing disease, that can be used when unphased genotypes are available for a number of cases and controls, and we apply this method to genotype data of patients with type 1 diabetes and of healthy controls. Here, as in the article by Bugawan et al. (2003), “haplotype interaction” is defined as the statistical dependence between alleles at different loci.

The increasing availability of polymorphic markers such as SNPs, automated genotyping technology, and large collections of family-based (or case-control–based) data have enabled the design of genomewide screens for several populations. Such screens have led to the location of susceptibility loci for type 1 diabetes in various chromosomal regions, suggesting that type 1 diabetes is a multigenic disorder, in the sense that onset of the disease requires the simultaneous presence of a subset of susceptibility genes. Most recent research efforts have concentrated on HLA genes (see Cox et al. [2001] and Pugliese [2001] for reviews). The importance of the HLA class II haplotypes was shown by Noble et al. (2002) in families with at least two children with insulin-dependent diabetes.

Once a disease-predisposing region has been localized, a number of potentially causative genetic variants may exist in the region, including a large number of SNPs. Whereas, for monogenic diseases, one base change in the coding region of a gene very often is sufficient to cause the disease, for multigenic diseases the effect of any single genetic variant on the risk of the disease may be small, which makes identification of these variants difficult (Drysdale et al. 2000). Furthermore, the following questions related to identification of the multiple risk variants arise. First, it is not clear which combination of variants has a causative role in the disease. Second, it remains unknown whether susceptibility for the disease arises because of the effects of these variants acting independently or because of some important interactions between the variants.

These questions have received increasing attention recently (see, for example, Valdes and Thomson 1997; Cox et al. 1999; Dassen et al. 2001; Cordell and Clayton 2002; Bugawan et al. 2003). Cordell and Clayton (2002) proposed a simple but powerful stepwise logistic-regression procedure that allows for testing the dominance effects of different combinations of polymorphisms, as well as genotype interactions in the analysis of case-control data. In particular, they measured genotype interactions in terms of penetrance for developing disease. However, haplotype interactions, since the underlying haplotype pairs of unphased genotypes may have different disease risks, so that there are disease-predisposing interactions, cannot be dealt with in their approach. To illustrate this, for the moment, we consider two diallelic variants of interest in a region: variant 1, with one of the unphased genotypes aa, AA, and aA; and variant 2, with one of the unphased genotypes bb, BB, and bB. There are nine possible combinations (also called “genotypes”) observed at the two variants: aa/bb, aa/bB, aa/BB, AA/bb, AA/bB, AA/BB, aA/bb, aA/bB, and aA/BB, where, for example, aA/bb means that the alleles in variants 1 and 2 are {a,A} and {b,b}, respectively. All of these genotypes except for aA/bB can be uniquely decomposed into a pair of haplotypes. For aA/bB, there are two compatible possible haplotype pairs, (a,b)/(A,B) and (a,B)/(A,b). The pairing described here indicates that allele a is coupled with allele b or allele a is coupled with allele B.

It is only when these two haplotype pairs have different disease risks that there may be potential disease-predisposing interactions between a and b or a and B. As pointed out by a reviewer, even when the haplotype pairs do have different disease risks, it does not necessarily mean that the alleles interact in anything other than a statistical sense, since this phenomenon could occur if alleles a and b, say, were in linkage disequilibrium with (and, thus, marking a haplotype containing) another predisposing variant not included in the analysis. Note that the stepwise logistic-regression procedure takes genotypes as explanatory variables and, therefore, the possible difference between the effects of the underlying haplotypes on the disease is ignored.

An alternative test is called the “haplotype method” (Valdes and Thomson 1997), which compares the relative frequencies of alleles at a secondary locus on haplotypes that are identical at a primary locus (or loci). The problem with the haplotype method is that, often, the haplotypes are not known. Although one can statistically infer the haplotypes from unphased genotypes, it is unclear how to judge the significance of the results from the haplotype method if we want to take into account the possible haplotyping errors. Several other approaches have been described for simultaneous identification of genetic factors through use of unphased genotype data, such as the modified transmission/disequilibrium test procedure (Cucca et al. 2001) and the conditional extended transmission/disequilibrium test (Koeleman et al. 2000). These approaches are also limited, by being restricted either to family data or to haplotype data. This and the fact that there are 2m-1 possible haplotype pairs for a genotype of m heterozygous sites, which results in a considerable number of potential haplotype interactions when m is large, motivated us to develop a special procedure for testing such interactions. The proposed method is based on minimal entropy, reflecting the principle that a good prediction of haplotype interactions should extract a maximum amount of information from data and, thus, most parsimoniously explain the underlying haplotype structure, given unphased genotypes. In general, the computation of the entropy statistic is very intensive. To solve this problem, we have developed a new Markov chain Monte Carlo algorithm called the “structure-annealing algorithm.”

Two types of approaches for the investigation of interaction can be distinguished: those that consider interaction in the sense of linkage disequilibrium between closely linked loci (Wall and Pritchard 2003) and those that consider interaction in the sense of effects on disease risk (Cordell and Todd 1995; Cordell et al. 2001). In this article, we focus on the linkage disequilibrium approach while investigating interaction between all loci and, hence, also between possibly unlinked loci. For any two haplotype blocks, let us denote by p1a and p2b the probabilities of occurrence for allele a at block 1 and for allele b at block 2, respectively. Let pab be the probability of simultaneous occurrence of a and b. We are trying to test whether, for all a and b, pab=p1ap2b. We assess the evidence for interactions between and within (possibly unlinked) haplotype blocks on different chromosomal regions by using a permutation procedure. Since the strength of a linkage disequilibrium pattern is not, typically, a monotonic function of recombination distance when there exist selective forces that favor certain haplotypes over others, as might be the case for type 1 diabetes (Fain and Eisenbarth 2001), we needed to develop an approach that is independent of this distance. Naturally, we are mainly interested in identification of disease-predisposing interactions by comparisons between cases and controls. The disease-predisposing interactions are found in a second stage, by contrasting the interaction patterns observed for patients with the interaction patterns observed for healthy controls. These interactions could facilitate understanding of the pathological mechanisms involved in the disease, as well as the further identification of some haplotype blocks that provide significant association with the disease only when their interactions with other blocks are taken into account.

As an illustration of our method, we present in this article a reanalysis of a set of genotypes that was obtained from a cohort of 89 Dutch patients with type 1 diabetes and 47 healthy control individuals, with a 65-polymorphism detection assay originally designed for unraveling the multigenic cause of atherosclerosis (Dassen et al. 2001). Since both diabetes mellitus and atherosclerosis can be regarded as metabolic diseases with many overlapping biochemical and clinical parameters, the variants that are susceptible to atherosclerosis may also be the cause of type 1 diabetes. Dassen et al. (2001) examined whether certain types of combinations of SNPs confer susceptibility to type 1 diabetes in the cohort by logistic regression and self-learning neural networks. They found that a set of four polymorphisms could predict 79.9% of the cases correctly. However, a significant number of polymorphisms could not be interpreted by their method. Note that all of these variants were selected from the pathways of lipid and homocysteine metabolism, regulation of blood pressure and coagulation, inflammation, cellular adhesion, and matrix integrity. Therefore, we wondered whether the variants that were unexplained in the above-mentioned study may serve as transitive (or supporting) variants, in the sense that they interact with some etiological variants within and between these pathways.

Before we applied the proposed procedure to the above-mentioned Dutch type 1 diabetes data, we evaluated the power of our approach by conducting a simulation study in which four different combinations of mutation and recombination rates were considered. The results are presented below. They suggest that a high accuracy can be achieved if appropriate critical values for our entropy statistics are selected. Note that, although the coalescent model that we have used for our simulations has been shown to be very helpful in modeling haplotype populations (Stephens et al. 2001), it is still not easy to statistically test whether this model fits real data, such as the Dutch type 1 diabetes data. Therefore, the thresholds that were obtained from the simulations were used as a guide to the corresponding parameters as we applied our method to the data. The results of our data analysis show some evidence for a haplotype interaction network that is potentially associated with type 1 diabetes and that includes the up interactions between the haplotype blocks from the chromosomes pairs (1,4), (1,12), (1,19), (6, 7), and (17, 21), as well as the down interactions between blocks from the chromosome pairs (2,7), (3,19), (5,7), (6,21), and (7,11). There are several other less significant pairs. Here, “up interaction” and “down interaction” mean that there exists a significant increase or decrease, respectively, in interaction between two blocks for patients over that for controls. We further found some disease-predisposing intrablock interactions on chromosomes 1, 6, 7, 8, and 11. Finally, we searched for loci interactions that may account for these block interactions. As a result, a total of 25 potential disease-predisposing interactions between loci are predicted, which indicates 19 gene-gene interactions among 19 candidate genes. Having found four dominant variants (Dassen et al. 2001), we predicted, from the interaction network, 19 transitive variants. Our results clearly demonstrate that, by considering interactions between haplotype blocks, we may succeed in identifying disease-predisposing genetic variants that might otherwise have remained undetected.

Methods

Haplotype Likelihood

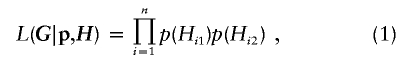

Let G=(G1,…,Gn)T denote the observed genotypes for n individuals from a population, where Gi=(gi1,…,giL)T, gij is the genotype of individual i at locus j, and L is the total number of observed loci per individual. For simplicity, let gij take values of 0, 1, or 2 for the cases in which its genetic haplotype at locus j is homozygous and identical to a prespecified reference, homozygous but different from the reference, or heterozygous, respectively. In addition, we let gij=7 if allele 0 is missing at locus j, gij=8 if allele 1 is missing, and gij=9 if both alleles are missing. A genotype is called “ambiguous” if it has at least two heterozygous sites. Let H=(H1,…,Hn)T, where Hi=(Hi1,Hi2) denotes the unobserved haplotype pair of Gi, and Hi∈ℋi, the set of all possible haplotype pairs compatible to Gi. Given G, under the assumption of Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium (Weir 1996, chapter 3), the “haplotype likelihood” can then be written as

|

where p(·) denotes the population frequency of the corresponding haplotype, and p=(p1,…,pm0). Here we assume that, overall, there are m0 possible haplotypes compatible with G.

Haplotype Entropy

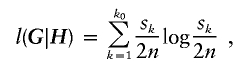

While performing a haplotype inference, we are usually interested only in H, and, hence, p works as a nuisance parameter in equation (1). Here, we follow Zhang et al. (2001) in eliminating the nuisance parameter by a maximization procedure—that is, we replace p in equation (1) with its maximum likelihood estimate (MLE). Thus, we have the following profile log likelihood:

|

where k0 denotes the number of different haplotypes in H, and s1,…,sk0 denote their respective frequencies. We define S(H)=-l(G|H), where S(H) is the entropy of the frequencies of different haplotypes in H, and s(G)=min{S(H):HiscompatiblewithG}. Note that S(H) attains its minimum at  , the MLE of H in equation (1), so that

, the MLE of H in equation (1), so that

For example, suppose that

Then, there are two possible ways to decompose these genotypes into haplotypes—namely,

and

where h1=(0,0,0)T, h3=(0,1,0)T, h5=(1,0,0)T, h7=(1,1,0)T, and h8=(1,1,1)T. The corresponding values of the haplotype likelihood shown in equation (1) are

and

where the unknown population frequencies of the five different haplotypes in equation (3) satisfy the equation

and the unknown population frequencies of the four different haplotypes in equation (4) are constrained by

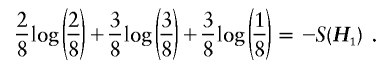

Given H1, and under the constraint of equation (5), the maximum of the logarithm of the likelihood in equation (3) is given by

|

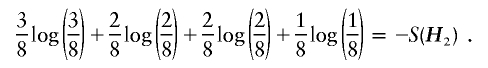

Analogously, given H2 and under the constraint of equation (6), the maximum of the logarithm of the likelihood in equation (3) is equal to

|

Obviously, S(H2)<S(H1). Hence, s(G)=S(H2).

In this article, we call s(G) the haplotype entropy of G. The quantity s(G) measures the diversity of the underlying haplotypes compatible with G, since the entropy is a well-known measure of variation for a system in information theory (Jones 1979). The stronger the interactions among the loci of G, the less diverse the underlying haplotypes, and the smaller the value of s(G). To explain this claim intuitively, we consider only three diallelic loci, at which there are eight possible haplotypes—namely, h1=(0,0,0)T, h2=(0,0,1)T, h3=(0,1,0)T, h4=(0,1,1)T, h5=(1,0,0)T, h6=(1,0,1)T, h7=(1,1,0)T, and h8=(1,1,1)T. Let p(hi) be the population frequency of hi for 1⩽i⩽8. The population haplotype entropy, defined as  is a measure of the diversity of the above haplotype population. In practice, we might have only a sample of genotypes of size n—say, G—which are assumed to be generated from these haplotypes according to the Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium. Then, the haplotype entropy

is a measure of the diversity of the above haplotype population. In practice, we might have only a sample of genotypes of size n—say, G—which are assumed to be generated from these haplotypes according to the Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium. Then, the haplotype entropy  in equation (2) gives rise to an empirical version of the above population entropy. To see how the haplotype entropy changes as the strength of interaction (i.e., dependence) increases, we first calculate this entropy when there are no interactions among the three loci. In this situation, the above eight haplotypes have the equal probability of occurrence 1/8 in individuals. As a result, the haplotype population reaches the highest diversity as the population entropy attains the maximum value of log8 (Jones 1979, chapter 2). Now, we consider the situation in which there exist some dependences among the three loci. Note that these dependences are apparent as increased frequencies of specific haplotypes compared with what would be expected if alleles at the three loci are combined at random. For example, if we set p(h1)=1/2, p(h5)=1/2, and p(hi)=0, i≠1,5, then the three loci are fully determined by the first locus. With the entropy being equal to log2, the resulting haplotype population yields a smaller diversity than the previous one. We observe that, as an empirical version of the population entropy,

in equation (2) gives rise to an empirical version of the above population entropy. To see how the haplotype entropy changes as the strength of interaction (i.e., dependence) increases, we first calculate this entropy when there are no interactions among the three loci. In this situation, the above eight haplotypes have the equal probability of occurrence 1/8 in individuals. As a result, the haplotype population reaches the highest diversity as the population entropy attains the maximum value of log8 (Jones 1979, chapter 2). Now, we consider the situation in which there exist some dependences among the three loci. Note that these dependences are apparent as increased frequencies of specific haplotypes compared with what would be expected if alleles at the three loci are combined at random. For example, if we set p(h1)=1/2, p(h5)=1/2, and p(hi)=0, i≠1,5, then the three loci are fully determined by the first locus. With the entropy being equal to log2, the resulting haplotype population yields a smaller diversity than the previous one. We observe that, as an empirical version of the population entropy,  is close to its population value when n is large. Therefore, in general, the population haplotype entropy—and, thus, its empirical version,

is close to its population value when n is large. Therefore, in general, the population haplotype entropy—and, thus, its empirical version,  —tends to decrease as the strength of these dependences increases.

—tends to decrease as the strength of these dependences increases.

Testing for Interaction between Two Haplotype Blocks

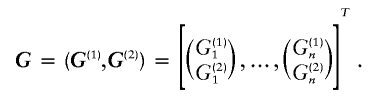

Let G=(G1,…,Gn)T be partitioned into two blocks—say,

|

Suppose that we are interested in testing whether there exists interaction between the two blocks G(1) and G(2). This problem can be stated as testing the hypotheses that the two blocks are independent (i.e., the null hypothesis) versus the hypothesis that the two blocks are dependent (i.e., the alternative hypothesis). As pointed out in the “Haplotype Entropy” subsection, if the null hypothesis is true, s(G) will tend to have a large value; otherwise, it will tend to be small. Hence, s(G) can be used as a test statistic for this test. Because the distribution of s(G) under the null hypothesis is unknown, the following procedure is designed to calculate the P values of the test:

-

Step 1:

Generate n′ random permutations of (G(2)1,…,G(2)n), and denote them by (G(2)j,1,…,G(2)j,n), j=1,…,n′.

-

Step 2:

Form a random sample G*j, j=1,…,n′, where G*j is formed by pairing (G(1)1,…,G(1)n) with (G(2)j,1,…,G(2)j,n).

-

Step 3:

Calculate the haplotype entropy for each G*j. An empirical P value can then be defined by the proportion of values of s(G*j) that are ⩽s(G); that is, #{s(G*j):s(G*j)⩽s(G)}/n′.

The number n′ is usually set to a moderate number. For example, it is 500 and 1,000 in this study.

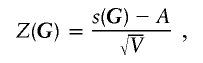

On the basis of the central limit theorem, an empirical Z score statistic,

|

can also be defined for the test, where A and V are the sample mean and variance, respectively, of the values of s(G*j). The empirical P value calculated in step 3 can be used to examine whether the between-block interaction existing in G was obtained by chance, whereas the empirical Z score statistic more sensitively measures the length of the distance between the genotypes under investigation and the population of genotypes without block interactions.

The above procedure will be used below to test the significance of the pairwise interactions among haplotype blocks or loci. In each case, the significance of an interaction will be decided by a threshold for P values. Assessment of the overall significance, to account for multiple testing, is not straightforward, because there are many correlations among the tests. An alternative approach is to control the false discovery rate (FDR), which is defined by the expected proportion of false positives among those called significant: E[V*/R*|R*>0]. Here, for a given threshold, V* is the total number of false positives, and R* is the total number of interactions called significant according the threshold. We opt for the recent proposal of Storey and Tibshirani (2003) to estimate the FDR and calculate the q value, a measure of statistical significance in terms of FDR, for each individual test under dependence.

Structure Annealing Algorithm

In this section, we propose a new algorithm, the so-called “structure annealing algorithm,” to minimize S(H). The algorithm is proposed on the basis of the following observation. Let G=(G(1),G(2)) be a random partition of G, and let H=(H(1),H(2)) be the corresponding partition of H. It is easy to see that, if H is compatible with G, then H(1) is compatible with G(1). Furthermore, if S(H(1)) is a good approximation of s(G(1)), then S(H(1),H(2)) should be a good approximation of s(G), provided that H is compatible with G and the number of loci in G(2) is not large. This observation motivated our use of the following sequential way to minimize the objective function S(H).

Suppose now that G is partitioned into z blocks, G=(G(1),…,G(z)), where G(b) comprises kb loci and  . It is preferable that kb be set to a small number—for example, kb⩽8 for all examples in this article. The structure annealing algorithm consists of two building blocks: a local updating algorithm and an extrapolation algorithm. The local updating algorithm (described in appendix A) is designed to simulate from the distributions

. It is preferable that kb be set to a small number—for example, kb⩽8 for all examples in this article. The structure annealing algorithm consists of two building blocks: a local updating algorithm and an extrapolation algorithm. The local updating algorithm (described in appendix A) is designed to simulate from the distributions

for b=1,…,z, where tb is called the “temperature” of this distribution, and  , which is compatible with

, which is compatible with  . The extrapolation algorithm (described in appendix B) is designed to extrapolate

. The extrapolation algorithm (described in appendix B) is designed to extrapolate  to

to  . The structure annealing algorithm starts with the simulation from

. The structure annealing algorithm starts with the simulation from  by the local updating algorithm, where

by the local updating algorithm, where  . Since the block size of G(1) is usually small, the iteration number of the local updating steps is also moderate at this step. We denote this iteration number by m1, and set m1=10,000 for all examples in this article. Then, the algorithm proceeds for z-1 steps. The (b+1)th step consists of two substeps, which are described as follows.

. Since the block size of G(1) is usually small, the iteration number of the local updating steps is also moderate at this step. We denote this iteration number by m1, and set m1=10,000 for all examples in this article. Then, the algorithm proceeds for z-1 steps. The (b+1)th step consists of two substeps, which are described as follows.

-

1.

Extrapolation: extrapolate the haplotype

, which is obtained at the last iteration of the bth step, to a compatible haplotype pair of

, which is obtained at the last iteration of the bth step, to a compatible haplotype pair of  .

. -

2.

Local updating: simulate from the distribution

by the local updating algorithm for mb+1 steps.

by the local updating algorithm for mb+1 steps.

The mb is a monotone increasing function of b; for example, we set mb=m1×b for b=1,2,…,z-1 and mz=10×m1×z. Here, as in the article by Kirkpatrick et al. (1983), we set a large iteration number for the last step simulation.

Results

Simulated Data Sets

We used a coalescent-based program called MS, by R. Hudson, to simulate haplotypes for the four different situations described by quantities (θ,R)=(4,0),(4,4), (4,20), and (16,16). Here θ=4Neμ, R=4Ner, Ne is the effective population size, μ is the total per-generation mutation rate across the region sequenced, and r is the length, in morgans, of the region sequenced.

For each setting of (θ,R), this generated 40 independent data sets, each containing 40 haplotypes. For each data set, the haplotypes were randomly paired to form 20 genotypes. As a result, for each case of (θ,R), we had 40 sets of 20 genotypes. They are denoted by G1,…,G40, with Gi=(Gi,1,…,Gi,20)T. We split each Gi,j into two parts of equal length, G(1)i,j and G(2)i,j, for i=1,…,40 and j=1,…,20. In total, we have 80 genotype segments. With these segments, 20 new data sets, which are denoted by G*1,…,G*20, are formed, where G*k is formed by attaching the segment G(2)20+k,j to the segment G(1)k,j for k=1,…,20. The above construction procedure shows that there are two independent blocks in each G*k.

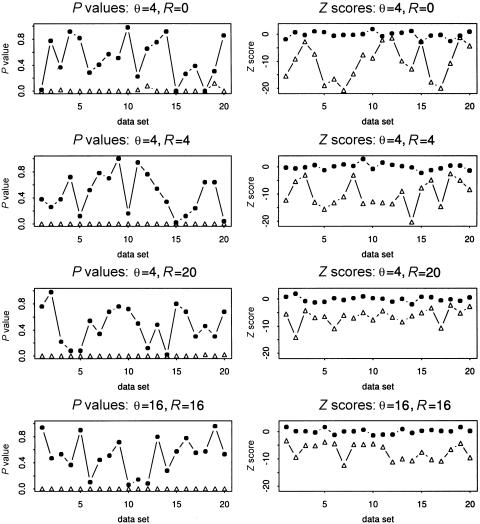

In the following, we will regard G*1,…,G*20 as samples from a population in which the two genotype blocks are independent, whereas we will regard G1,…,G20 as samples from a population in which the two genotype blocks are dependent. To evaluate the power of our procedure, we applied it to these genotype data sets. The resulting P values and Z scores are summarized in figure 1. To find the interesting blocks, we further analyzed these P values by setting lower and upper thresholds of .01 and .15. We say two blocks are dependent if the corresponding P value is ⩽.01, whereas we say they are independent if the corresponding P value is ⩾.15. The performance of our procedure is measured by the proportions of false positives and negatives, Fa and Fn. That is, Fa is the proportion of false rejections of the null hypothesis when the null hypothesis is true, and Fn is the proportion of false nonrejections of the null hypothesis when the alternative is true. For the above simulated data, we have (Fa,Fn)=(0,2/20) when (θ,R)=(4,0), and (Fa,Fn)=(0,0) when (θ,R)=(4,4), (4,20), and (16,16). These results show that our procedure is, indeed, an effective tool for detecting haplotype interactions. As pointed out in the Introduction, the coalescent model can capture certain main features in a haplotype population (Stephens et al. 2001). The above simulated coalescent models might share some common features with real haplotype data. Thus, these thresholds were used to guide our choice of the corresponding thresholds when we applied our method to the Dutch type 1 diabetes data below.

Figure 1.

The P values and Z scores for 40 sets of genotypes with (θ,R)=(4,0), (4,4), (4,20) and (16,16). The dotted lines are for the data sets in which there are interactions between two haplotype blocks, and the lines with small triangles are for the data sets in which there are no interactions between the two haplotype blocks.

Type 1 Diabetes Data

Thirty-six candidate genes, listed in table 1, were selected from pathways that are potentially implicated in the development and progression of atherosclerosis: lipid and homocysteine metabolism, regulation of blood pressure and coagulation, inflammation, cellular adhesion, and matrix integrity (Cheng et al. 1999; Dassen et al. 2001). They have all been reported in the Online Mendelian Inheritance in Man (OMIM) database. Dassen et al. (2001) described an assay, for genotyping a panel of 65 SNPs that represent variation within these genes, that is an early version of RMS Research Assay for Cardiovascular Disease Genetics designed by Roche Molecular Systems. Most of these SNPs have been shown to be implicated with some metabolic diseases, such as cardiovascular disease, coronary artery disease, hypertension, asthma, obesity, atherosclerosis, myocardial infarction, hyperlipidemia, Alzheimer disease, and others (see table 1 and OMIM for more details). The rest of these SNPs are either the polymorphisms at (or close to) the promoter regions that may (directly or indirectly) play certain dysregulation roles for the genes of interest or the polymorphisms at coding regions with nonsynonymous changes (Cheng et al. 1999; Dassen et al. 2001; Flori et al. 2003; Vatay et al. 2003). For example, V67 was selected because it could have a protective role against type 2 diabetes (NIDDM) (Vatay et al. 2003). V66 was included because it often interfered with our ability to call V67 correctly. We had no prior functional information, other than that its proximity to V67 could mean that it would also have impact on the function of the gene TNF. As pointed out in the Introduction, since both diabetes mellitus and atherosclerosis can be regarded as metabolic diseases with many overlapping biochemical and clinical parameters, the variants that are susceptible to atherosclerosis may also be the cause of type 1 diabetes. Therefore, this assay was also applied to a Dutch cohort with diabetes that includes 136 unrelated individuals (89 patients with type 1 diabetes with impaired endothelial function and 47 healthy control individuals). Endothelial function was assessed by measuring changes in forearm blood flow after pharmacological interventions. The DNA samples from the 136 individuals were genotyped by use of PCR. This led to 136 genotypes of 65 loci. Nine loci (V58, V59, V66, V67, V5, V57, V51, V52, and V30) were not used in the following data analysis, since these loci have the so-called “heavy-missing” problem, where ⩾21% of the 136 individual genotypes were incomplete in the PCR experiments. The heavy-missing problem may introduce the bias in our data analysis. The cutoff point of 21% was selected on the basis of our experience. We ended up with a 136×56 data matrix. Each genotype can be divided into 16 blocks, according to their chromosome identities (see table 1 for more details).

Table 1.

SNPs Used in the Present Study[Note]

| Block and Variant (Symbol, dbSNP rs #) | Gene Name (OMIM #) | Location | Reported Implication |

| 1: | |||

| C677T (V36,1801133) | MTHFR (MIM 607093) | 1p36.3 | Risk factor in vascular disease |

| Arg506Gln (V53, 6025) | F5 (MIM 227400) | 1q23 | Activated protein C resistence |

| Ser128Arg (V61, 5361) | SELE (MIM 131210) | 1q23-25 | Coronary artery disease |

| Leu554Phe (V62, 5355) | SELE (MIM 131210) | 1q23-25 | Coronary artery disease |

| Met235Thr (V42, 699) | AGT (MIM 106150) | 1q42-43 | Hypertension |

| Val7Met (V43, 664) | NPPA (MIM 108780) | 1p36.2 | Hypertension |

| T2238C (V44, 2238) | NPPA (MIM 108780) | 1p36.2 | |

| 2: | |||

| Thr71Ile (V8, 1367117) | APOB (MIM 107730) | 2p24 | Increased plasma low-density lipoprotein cholesterol level |

| Arg3500Gln (V9, 5742904) | APOB (MIM 107730) | 2p24 | Hypercholesterolemia |

| 3: | |||

| Pro12Ala (V19, 1801282) | PPARG (MIM 601487) | 3p25 | Nonsynonymous change, type 2 diabetes |

| A1166C (V41, 5186) | AGTR1 (MIM 106165) | 3q21-25 | Hypertension |

| 4: | |||

| Gly460Trp (V45, 4961) | ADD1(MIM 102680) | 4p16.3 | Hypertension |

| G−455A (V58, 1800790)a | FGB (MIM 134830) | 4q28 | Progression of atherosclerosis |

| 5: | |||

| Arg16Gly (V49, 1042713) | ADRB2 (MIM 109690) | 5q32-34 | Asthma |

| Gln27Glu (V50, 1042714) | ADRB2 (MIM 109690) | 5q32-34 | Obesity |

| G873A (V59, 1062535)a | ITGA2 (MIM 192974) | 5q23-31 | Glycoprotein Ia/IIa surface expression |

| 6: | |||

| C93T (V4, 1652503) | LPA (MIM 152200) | 6q27 | Atherosclerosis |

| Thr26Asn (V32, 1041981) | LTA (MIM 153440) | 6p21.3 | Myocardial infarction |

| Thr26Asn (V68, 1041981) | TNFb (MIM 153440) | 6p21.3 | Myocardial infarction |

| G−376A (V64, 1800750) | TNF (MIM 191160) | 6p21.3 | Malaria |

| G−308A (V65, 1800629) | TNF (MIM 191160) | 6p21.3 | Asthma |

| G−244A (V66, 673)a | TNF (MIM 191160) | 6p21.3 | |

| G−238A (V67, 361525)a | TNF (MIM 191160) | 6p21.3 | Protective against type 2 diabetes |

| G121A (V5, 1800769)a | LPA (MIM 152200) | 6q27 | |

| 7: | |||

| A−922G (V37, 1800779) | NOS3 (MIM 163729) | 7q36 | |

| C−690T (V38, 3918226) | NOS3 (MIM 163729) | 7q36 | |

| Glu298Asp (V39, 1799983) | NOS3 (MIM 163729) | 7q36 | Hypertension, Alzheimer disease |

| 5G(−675)4G (V56, 1799768) | PAI1 (MIM 173360) | 7q21.3-22 | Coronary artery disease |

| Met55Leu (V25, 3202100) | PON1 (MIM 168820) | 7q21.3 | Cardiovascular disease |

| Gln192Arg (V26, 662) | PON1 (MIM 168820) | 7q21.3 | Coronary artery disease |

| Ser311Cys (V27, 7493) | PON2 (MIM 602447) | 7q21.3 | Coronary artery disease |

| G11053T (V57, 7242)a | PAI1 (MIM 173360) | 7q21.3-22 | |

| 8: | |||

| Trp64Arg (V18, 4994) | ADRB3 (MIM 109691) | 8p12-11.2 | Type 2 diabetes in some populations |

| T−93G (V21, 1800590) | LPL (MIM 238600) | 8p22 | Combined hyperlipidemia |

| Asp9Asn (V22, 1801177) | LPL (MIM 238600) | 8p22 | Combined hyperlipidemia |

| Asn291Ser (V23, 268) | LPL (MIM 238600) | 8p22 | Combined hyperlipidemia |

| Ser447term (V24, 328) | LPL (MIM 238600) | 8p22 | Type 1 hyperlipidemia |

| 9: | |||

| Thr347Ser (V6, 675) | APOA4 (MIM 107690) | 11q23 | |

| Gln360His (V7, 5110) | APOA4 (MIM 107690) | 11q23 | The metabolism of apolipoprotein B |

| C−641A (V10, 2542052) | APOC3 (MIM 107720) | 11q23 | |

| C−482T (V11, 2854117) | APOC3 (MIM 107720) | 11q23 | Increased plasma triglyceride levels |

| T−455C (V12, 2854116) | APOC3 (MIM 107720) | 11q23 | Increased plasma triglyceride levels |

| C1100T (V13, 4520) | APOC3 (MIM 107720) | 11q23 | Increased plasma triglyceride levels |

| C3175G (V14, 5128) | APOC3 (MIM 107720) | 11q23 | Increased plasma triglyceride levels |

| T3206G (V15, 4225) | APOC3 (MIM 107720) | 11q23 | |

| 5A(−1171) 6A (V51, 3025058)a | MMP3 (MIM 185250) | 11q23 | Coronary heart disease |

| G20210A (V52, 1799963)a | F2 (MIM 176930) | 11p11-q12 | Hyperprothrombinemia |

| 10: | |||

| Trp493Arg (V46, 5742912) | SCNN1A (MIM 600228) | 12p13 | Nonsynonymous change |

| Thr663Ala (V47, 2228576) | SCNN1A (MIM 600228) | 12p13 | Nonsynonymous change |

| C825T (V48, 5443) | GNB3 (MIM 139130) | 12p13 | Hypertension |

| 11: | |||

| −323 10-bp Ins/Del (V54, 5742910) | F7 (MIM 227500) | 13q34 | Hypertension |

| Arg353Gln (V55, 6046) | F7 (MIM 227500) | 13q34 | Myocardial infarction |

| 12: | |||

| C−480T (V20, 1800588) | LIPC (MIM 151670) | 15q21-23 | Regulation of plasma lipids |

| 13: | |||

| C−631A (V29, 1800776) | CETP (MIM 118470) | 16q21 | |

| Ile405Val (V31, 5882) | CETP (MIM 118470) | 16q21 | Plasma high-density lipoprotein cholesterol level |

| Asp442Gly (V33, 2303790) | CETP (MIM 118470) | 16q21 | Cholesteryl ester transfer protein deficiency |

| G+1A (V34, 5742907) | CETP (MIM 118470) | 16q21 | Cholesteryl ester transfer protein deficiency |

| C−629A (V30, 1800775)a | CETP (MIM 118470) | 16q21 | |

| 14: | |||

| Alu element Ins/Del (V40, 1799752) | ACE (or DCP1) (MIM 106180) | 17q23 | Myocardial infarction |

| Leu33Pro (V60) | ITGB3 (MIM 173470) | 17q21.32 | Coronary heart disease |

| 15: | |||

| Cys112Arg (V16, 429358) | APOE (MIM 107741) | 19q13.2 | Hyperlipoproteinemia |

| Arg158Cys (V17, 7412) | APOE (MIM 107741) | 19q13.2 | Hyperlipoproteinemia |

| Gly241Arg (V63, 1799969) | ICAM1 (MIM 147840) | 19p13.3-13.21 | |

| NcoI+/− (V28, 5742911) | LDLR (MIM 606945) | 19p13.2 | Cholesterol homeostasis |

| 16: | |||

| Ile278Thr (V35, 5742905) | CBS (MIM 236200) | 21q22.3 | Homocystinaria |

Note.— A list of references regarding the SNPs in this table can be downloaded from the Research at Brigham and Women's Hospital download site.

Locus was not used in data analysis because of the problem of “heavy missing,” in the sense that at least 21% of the 136 individual genotypes are imcomplete at this locus.

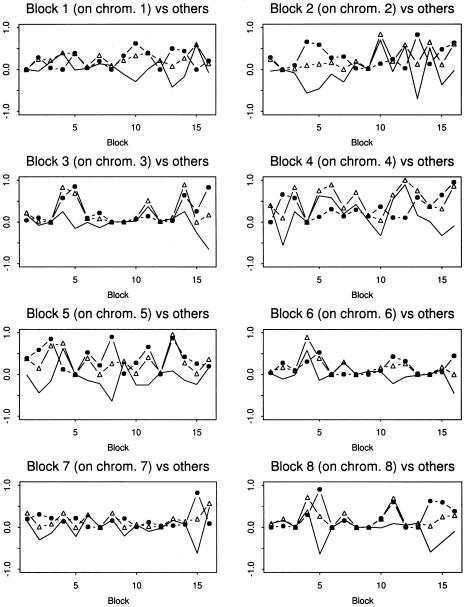

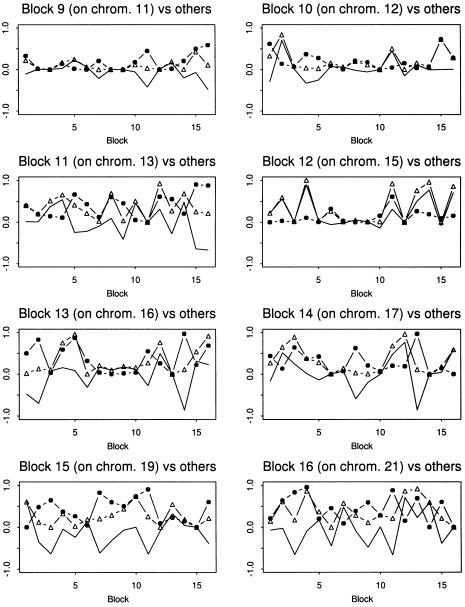

We started with the search for pairwise interactions among these 16 unlinked blocks. The search was performed on the cases and controls separately. The P values for the cases and controls were compared by plotting them in graphs, as shown in figures2 and 3, respectively. We obtained 10 pairs of interacting blocks, located on chromosome pairs (1,4), (1,12), (1,19), (2,7), (3,19), (5,7), (6,7), (6,21), (7,11), and (17,21) (seetable 2 for more details). These block pairs were selected by use of the following criteria: for the up interaction, we claimed that there was an increase in haplotype interaction if the P value of the controls was >.15, the P value of the cases was ⩽.01, and the Z score of the cases was ⩽−2. This says that, in contrast to the healthy individuals, there is a significant interaction between two haplotype blocks under consideration in the individuals with disease. For the down interaction, we claimed that there was a decrease in haplotype interaction if the P value of the cases was >.15, the P value of the controls was ⩽.01, and the Z score of the controls was ⩽−2. This implies that, in contrast to the healthy individuals, there is no significant interaction between two haplotype blocks under consideration in the individuals with disease. Among these selected blocks, the up-interaction pairs for chromosome pairs (1,4), (1,12), (1,15), (1,19), (6,7), and (17,21) indicate that the pathways harboring these variants may have been modified by adding some interactions between some genes in the individuals who had the disease. Analogously, the down-interaction pairs on chromosome pairs (3,19), (2,7), (6,21), (7,11), (5,7), (12,15) indicate that the related pathways may have been changed, since interactions between some genes are disrupted. Note that, with the P value thresholds .01 and .15 for cases and controls, respectively, the corresponding estimated FDRs of these multiple tests for cases and controls are 0.017 and 0.029. There will be more interaction pairs if we take .035 and .2 as the thresholds for cases and controls, respectively. The FDRs will then become 0.040 and 0.048 (see table 2 for more details).

Figure 2.

The P values of testing the interactions of blocks 1–8 with the other blocks, for the cases and controls in the Dutch type 1 diabetes data. The dotted lines are for the cases, and the lines with small triangles are for the controls. The normal line, a contrast between the two lines, is derived by subtracting the corresponding P values of the control from those of the case.

Figure 3.

The P values of testing the interactions of blocks 9–16 with the other blocks, for the cases and controls in the Dutch type 1 diabetes data. The dotted lines are for the cases, and the lines with small triangles are for the controls. The normal line, a contrast between the two lines, is derived by subtracting the corresponding P values of the control from those of the case.

Table 2.

Haplotype Interactions that Predispose to Type 1 Diabetes

|

Cases |

Controls |

|||||

| Block Pair/Chromosomal Locationor Variant Pair/Gene Paira | P Value | q Value | Z Score | P Value | q Value | Z Score |

| (1,4)/(1,4) | .000 | .000 | −2.9732 | .40 | .13 | −.133 |

| (V44:V45)/(NPPA:ADD1) | .01 | −3.4988 | .964 | 1.0808 | ||

| (1,10)/(1,12) | .000 | .000 | −3.5908 | .22 | .1 | −.712 |

| (V62:V46)/(SELE:SCNN1A) | .032 | −5.8305 | 1.00 | .3251 | ||

| (1,15)/(1,19) | .000 | .000 | −3.7758 | .60 | .18 | .243 |

| (V43:V17)/(NPPA:APOE) | .018 | −3.2417 | .93 | .3975 | ||

| (2,7)/(2,7) | .31 | .12 | −.4364 | .01 | .019 | −2.4063 |

| (V8:V39)/(APOB:NOS3) | .35 | −.2049 | .002 | −3.7312 | ||

| (2,8)/(2,8) | .03 | .036 | −2.0210 | .20 | .10 | −.709 |

| (V9:V22)/(APOB:LPL) | .002 | 2.3361 | 1.00 | −.9950 | ||

| (2,12)/(2,15) | .032 | .037 | −2.2290 | .59 | .18 | .315 |

| (V8:V20)/(APOB:LIPC) | .6 | .4021 | .022 | −2.2037 | ||

| (3,15)/(3,19) | .258 | .11 | −.6140 | .00 | .000 | −4.380 |

| (V41:V16)/(AGTR1:APOE) | .528 | .1457 | .0475 | −2.1793 | ||

| (5,7)/(5,7) | .22 | .10 | −.9170 | .000 | .000 | −2.2606 |

| (V50:V38)/(ADRB2:NOS3) | .37 | −.3814 | .01 | −2.7346 | ||

| (6,7)/(6,7) | .01 | .017 | −2.4328 | .30 | .12 | −.6584 |

| (V4:V26)/(LPA:PON1) | .0075 | −3.1221 | .996 | 1.3345 | ||

| (V4:V37)/(LPA:NOS3) | .016 | −3.0343 | .968 | .7989 | ||

| (V4:V39)/(LPA:NOS3) | .636 | .5031 | .046 | −2.6121 | ||

| (V65:V38)/(TNF:NOS3) | .014 | −2.5465 | .85 | 1.0279 | ||

| (V68:V37)/(TNFb:NOS3) | .01 | −3.6194 | .222 | −.6165 | ||

| (6,16)/(6,21) | .45 | .15 | −.4934 | .000 | .000 | −2.0156 |

| (V32:V35)/(TNFb:CBS) | .61 | −.2664 | .0375 | −4.2425 | ||

| (7,9)/(7,11) | .21 | .10 | −.9432 | .000 | .000 | −2.9033 |

| (V38:V7)/(NOS3:APOA4) | .16 | −1.6673 | .000 | −11.3963 | ||

| (V26:V7)/(PON1:APOA4) | .37 | −.3737 | .025 | −2.3077 | ||

| (V25:V10)/(PON1:APOC3) | .51 | −.0683 | .028 | −2.4287 | ||

| (V25:V12)/(PON1:APOC3) | .78 | .8031 | .028 | −2.1233 | ||

| (V38:V11)/(NOS3:APOC3) | .786 | .6522 | .004 | −3.5639 | ||

| (V37:V11)/(NOS3:APOC3) | .78 | .6673 | .028 | −2.6518 | ||

| (V37:V10)/(NOS3:APOC3) | .296 | −.4199 | .002 | −4.8354 | ||

| (V37:V12)/(NOS3:APOC3) | .73 | .7839 | .000 | −4.7122 | ||

| (V38:V13)/(NOS3:APOC3) | .71 | .4653 | .024 | −3.3368 | ||

| (9,13)/(11,16) | .02 | .027 | −2.3164 | .19 | .1 | −.7887 |

| (10,12)/(12,15) | .155 | .09 | −.9611 | .01 | .019 | −2.5475 |

| (V47:V20)/(SCNN1A:LIPC) | .172 | −1.1070 | .002 | −4.7115 | ||

| (14,16)/(17,21) | .000 | .000 | −4.1709 | .59 | .18 | .1466 |

| (V40:V45)/(DCP1:CBS) | .025 | −4.0039 | .697 | .7439 | ||

Block pairs/chromosomal locations are given in the format “(1,4)/(1,4),” and variant pairs/gene pairs are given in the format “(V44:V45)/(NPPA:ADD1).”

To see how these interactions modify the related pathways, we ran our procedure on the pairs of variants on these blocks. Consequently, 25 pairs of variants were found to show certain evidence of susceptibility to the disease. Table 2 indicates that these variants are distributed on 19 genes: NPPA, SELE, ADOB, AGTR1, ADRB2, LPA, TNF, TNFb, DCP1, ADD1, SCNN1A, APOE, NOS3, LPL, LIPC, PON1, CBS, APOA4, and APOC3. Note that APOB, ADRB2, LPA, APOE, LPL, LIPC, PON1, and APOA4 are on the pathway of lipid metabolism; CBS is on the pathway of homocysteine metabolism; NPPA, AGTR1, ADRB2, DCP1, SCNN1A, and NOS3 are on the pathway of blood pressure; SELE is on the pathway of coagulation; SELE, TNF, and TNFb are on the pathway of inflammation; and ADD1 is on the pathway of matrix integrity. Thus, within the pathway of lipid metabolism there are seven up or down interactions, denoted by the symbols (+) and (−) respectively, among some genes. They are V9:V22 (APOB:LPL) (+), V8:V20 (APOB:LIPC) (−), V4:V26 (LPA:PON1) (+), V26:V7 (PON1:APOA4) (−), V25:V10 (PON1:APOC3) (−), and V25:V12 (PON1:APOC3) (−). These interactions are predisposing to the disease. Similarly, within the pathway of blood pressure, there is one down interaction: V50:V38 (ADRB2:NOS3) (−). The rest are related to interactions among the six pathways mentioned above. Here, up interaction (down interaction) is trying to describe the biological phenomenon through which the pathways of lipid metabolism, homocysteine metabolism, blood pressure, inflammation, and matrix integrity are modified, by creating (disrupting) interactions among some genes that lie in these pathways. Similar to what Sudbery (1998, p. 144) has suggested, the up interactions would suggest that those interactions lead to a susceptibility to the disease, whereas the down interactions could imply that the related interactions may have a protective effect on developing the disease. These results indicate a complicated feature of (possibly nonmultiplicative) effects of the interactions on the risk for type 1 diabetes.

Note that Dassen et al. (2001) have identified a set of dominant variants—V4, V15, V28, and V50—that are on chromosomes 6, 11, 19, and 5, respectively. This, combined with the above results, yields the following transitive and disease-predisposing variants, in the sense that there are significant increases (or decreases) of interactions of these variants with some dominant variants: V26, V37, V38, V39, V7, V8, V10, V11, V12, V13, V65, V68, V20, V25, and V47.

In the next step, we screened for interactions in linked regions. For simplicity, we adopted the following strategy. Taking block 1 as example, we sequentially tested six subblock pairs for the cases and controls: the first pair was {1},{2,3,4,5,7}, with 1 being the splitting location; the second pair was {1,2},{3,4,5,7}, with 2 being the splitting location; and so on. Here, the numbers 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, and 7 denote the seven variants in block 1. The six subblock pairs are uniquely defined by six splitting locations: 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, and 6. We compared the resulting six pairs of P values and Z scores in table 3. It suggests that there exists some disease-predisposing interaction between subblock pairs {1,2,3,4} and {5,6,7}. Following the same argument as above, for block 6 we may conclude that variant V64 might be a transitive disease-predisposing variant, because the dominant variant, V4, is at subblock {1,2,3}. The evidence of disease-predisposing interactions within the other blocks is reported in table 4, which yields the transitive variant V14. Note that, in practice, we need to test the interactions for all bipartitions of seven loci, since the strength of linkage disequilibrium patterns is not, typically, a monotonic function of genetic distance. Our procedure can be easily extended to this general setting, since it does not use any information on genetic distances among these loci.

Table 3.

P Values and Z Scores for Testing Interactions within Block 1

|

Cases |

Controls |

|||

| SplittingLocation | P Value | Z Score | P Value | Z Score |

| 1 | .42 | −.0497 | .23 | −.6620 |

| 2 | .06 | −1.5060 | .40 | −.3271 |

| 3 | .07 | −1.6728 | .69 | .5059 |

| 4 | .00 | −2.4910 | .31 | −.4083 |

| 5 | .05 | −1.6461 | .53 | .0784 |

| 6 | .10 | −1.2424 | .33 | −.2145 |

Table 4.

Within-Haplotype Interactions That Predispose to Type 1 Diabetes

|

Cases |

Controls |

|||

| BlockandSplittingLocation | P Value | Z Score | P Value | Z Score |

| 1: | ||||

| 4 | .00 | −2.4910 | .31 | −.4083 |

| 5 | .05 | −1.6461 | .53 | .0784 |

| 6: | ||||

| 3 | .27 | −.5888 | .00 | −4.2116 |

| 7: | ||||

| 5 | .04 | −1.9404 | .26 | −.5867 |

| 8: | ||||

| 1 | .16 | −.7903 | .01 | −2.9411 |

| 2 | .52 | .2147 | .02 | −3.0241 |

| 9: | ||||

| 3 | .11 | −1.3035 | .00 | −7.8697 |

| 4 | .10 | −1.1386 | .00 | −9.2839 |

| 5 | .13 | −.8928 | .00 | −3.6252 |

| 6 | .19 | −.8848 | .00 | −4.8922 |

| 7 | .46 | −.1373 | .02 | −1.7784 |

Discussion

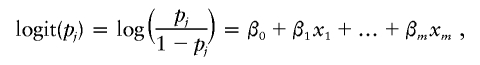

The logistic regression mentioned in the Introduction is a very important genotype-based tool for detecting dominant polymorphisms and epistatic effects (i.e., genotype interactions) that are associated with disease. One disadvantage of this method over some haplotype-based methods is that it ignores the potential disease-predisposing haplotype interactions. To contend with this disadvantage, we have presented a procedure for evaluating the contributions of these haplotype interactions to susceptibility to disease, in which the entropy is used to measure the diversity of a haplotype population. Our procedure can be easily generalized to other measures of the haplotype diversity (Weir 1996; Clayton 2002). Of course, for applications, we should combine these two methods, in order to extract more complete information from unphased genotype data, in the following steps: first, apply the logistic regression to detect dominant disease-predisposing variants and genotype interactions; then, as a complement, use our procedure to find potential haplotype interactions; finally, predict the transitive variants by finding the variants that are interacting with the dominant ones.

In the first step, we assume a sample of n1 cases and n2 controls, each of whom is genotyped at m polymorphisms. Let pj be the probability of individual j being a case rather than a control. Following McCullagh and Nelder (1989), we model pj as

|

where x1,…,xm are covariates depending on the genotypes of the individual, and β0,…,βm are coefficients to be estimated. To examine the effects of a set of polymorphisms, we can test whether the data are significantly better represented when these polymorphisms are included in the model compared with when they are not in the model, through use of likelihood-ratio tests (Cordell and Clayton 2002). This is equivalent to testing whether the corresponding coefficients are significantly different from 0. Similarly, we can account for the genotype interactions by adding some epistatic terms to the above model. A commonly used strategy for evaluation of the effects of the different polymorphisms is to fit these models in a stepwise fashion. Following Cordell and Clayton (2002), for the Dutch type 1 diabetes data, we first code xj=-0.5, 0.5, and 0.5 for genotypes 0, 2, and 1, respectively, and we also code 0.5 for the cases in which genotypes are missing. We set .05 as a nominal significance level for all these tests involved in the stepwise logistic-regression procedure. This yields seven dominant disease-susceptibility alleles on chromosomes 3, 6, 7, 6, 11, 19, and 2, respectively: V41(AA), V4(TT), V26(GG), V64(GG), V15(GG), V28(−), V9(missing), and one genotype interaction between V41(AA) and V64(GG), where, for example, in the notation “V41(AA),” V41 is the name of the variant and (AA) is one of its alleles (see table 5). The result is slightly different from the prediction-based logistic-regression procedure of Dassen et al. (2001); this might be because of different criteria being used.

Table 5.

Results of the Stepwise Logistic Regression for the Dutch Data

| Varianta | Coefficient | SE | ResidualDeviance | P Value |

| Intercept | .93277 | .42811 | 175.35 | |

| V41 | −.04511 | 1.10738 | 170.65 | .0302 |

| V4 | 17.2308 | 1.10738 | 162.98 | .0056 |

| V26 | −1.3954 | .94438 | 158.65 | .0375 |

| V64 | .73047 | 1.21786 | 151.01 | .0057 |

| V15 | 4.58316 | 1.49003 | 141.54 | .0021 |

| V9(missing) | 19.6659 | 73.3194 | 137.1299 | .0357 |

| V28 | −4.8015 | 1.9924 | 129.9424 | .0073 |

| V41:V64 | −11.0055 | 4.3711 | 122.5526 | .0066 |

Variants added sequentially.

In the second step, we start with a search for the haplotype interaction between blocks located on different chromosomes, followed by testing of the interactions within each block. If two blocks are found interacting, we can further narrow the search area to identify which variants in the blocks are involved in this interaction. For the Dutch type 1 diabetes data, in the “Results” section we have shown nine pairs of interacting blocks that are predisposed to type 1 diabetes. Combining with the result from the first step, we can infer some transitive disease-predisposing variants, as shown in the “Results” section. The results demonstrate a complicated gene-gene interaction network, which might predispose to type 1 diabetes through modifying the pathways of lipid metabolism, blood pressure, inflammation, coagulation, and matrix integrity.

Use of interaction between unlinked genomic regions has been suggested for improving power to detect loci of small effect on the disease phenotype; for example, in type 1 diabetes (Cordell et al. 1995, 2000; Bugawan et al. 2003), type 2 diabetes (Cox et al. 1999), and inflammatory bowel disease (Cho et al. 1998). Cordell et al. (1995) reported that there are interactions between the loci IDDM1 (chromosome 6p21) and IDDM2 (chromosome 11p15) and between the loci IDDM1 and IDDM4 (on chromosome 11q13.3), in the context of the logistic regression model. Cox et al. (1999) showed that the loci on chromosomes 2 and 15 interact to increase susceptibility to type 2 diabetes, in the context of a nonparametric LOD score. Cox et al. (2001) performed a systematic screen for correlation between family-specific nonparametric LOD scores to evaluate evidence of interactions between some unlinked regions on chromosomes 1, 2, 3, 4, 6, 11, and 19. These methods are usually restricted to family data. Unlike these authors, we focus here on interactions between genetic variants in a list of potential candidate genes across a number of chromosomes, where some of these variants have already been shown to be associated with some metabolic diseases. Moreover, the proposed approach is specified for unphased genotype data (possibly with missing problems) from case-control studies. Thus, our method could be a valuable contribution to a genomewide association study of a complex disease, especially when direct determination of the molecular haplotypes from experiment or family data is not feasible.

Although significant and consistent linkage evidence was reported for the susceptibility intervals IDDM8 (on chromosome 6q27), IDDM4 (on 11q), and IDDM5 (on 6q25), evidence for most other intervals varies in different data sets, probably because of a weak effect of the disease genes, genetic heterogeneity, random variation, or inappropriate correction for multiple tests (see Pugliese 2001). To reduce the possible effect of genetic heterogeneity, we need to confirm our initial finding by analyzing other populations in future studies. Since we compared correlated variants, it is important to take into account the potential effects of multiple tests on the power of our procedure. For our case, there are 120 pairwise tests among 16 haplotype blocks. A simple Bonferroni (or Dunn-Sidak) correction leads to the adjusted threshold of 4.17×10-4 for P values if we want to achieve the significance level of .05; there are only seven block pairs in table 2 that remained nominally significant after this correction. Such a correction seems too conservative, because of high dependences among these tests. This has been confirmed by Bugawan et al. (2003) on the basis of a permutation procedure. Unfortunately, using resampling methods such as permutation can be computationally prohibitive in our case. However, we have shown that the recently developed procedure of Storey and Tibshirani (2003) is applicable to our setting.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to the Editor, the Deputy Editor, and other members of the Editorial Board, as well as to two anonymous reviewers, for their very constructive comments that have led to improvement of the presentation and results of the present article. We thank Roche Molecular Systems (Alameda, CA) for providing the multiplex genotyping assays, under a research collaboration. We thank Drs. Suzanne Cheng and Paul Schiffers for kindly providing some information on the SNPs used in this paper. We also thank Professors W. van Zwet, W. J. M. Senden, and M. Vingron and Dr. P. Lindsey for useful discussions. This work was partially performed when the first author was working for EURANDOM, in The Netherlands. The work was supported, in part, by the Programme of Computational Molecular Biology of EURANDOM, by the Institute for Mathematical Sciences, National University of Singapore, and by grant No. 01/1/21/19/217 from the Biomedical Research Council of Singapore.

Appendix A : Local Updating

The local updating algorithm includes two operators, ν-mutation and peer learning. In every iteration, they are selected to perform with probability 0.2 and 0.8, respectively. Of course, the probabilities can be tuned by the user, but a large performing probability is usually assigned to the peer learning operator, since it tends to force the haplotypes to coalesce. The two operators are described below.

ν-Mutation Operator

In the ν-mutation operator, a total of max{1,γbν} haplotype pairs at the heterozygous (gij=2) or missing (gij=9,8,7) loci are randomly selected to undergo changes, where γb is the total number of heterozygous and missing loci in  , and ν is the mutation rate specified by the user. The ν is usually set to a small number; for example, we set ν=0.001 for all examples in this article. The changes are accepted or rejected according to the Metropolis-Hastings rule (Metropolis et al. 1953; Hastings 1970)—that is, the new haplotypes

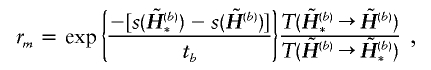

, and ν is the mutation rate specified by the user. The ν is usually set to a small number; for example, we set ν=0.001 for all examples in this article. The changes are accepted or rejected according to the Metropolis-Hastings rule (Metropolis et al. 1953; Hastings 1970)—that is, the new haplotypes  are accepted with probability min(1,rm), where

are accepted with probability min(1,rm), where

|

where T(·→·) denotes the transition probability between the current and new haplotypes. The transition proceeds as follows. If the pair (hb,ij,1,hb,ij,2) is selected to undergo a change and if gij=2, then the values of hb,ij,1 and hb,ij,2 will be simply swapped by setting hb,ij,1=1-hb,ij,1 and hb,ij,2=1-hb,ij,2. If gij=9, one of the pairs (0,0), (0,1), (1,0), and (1,1) are equally likely to be reassigned to (hb,ij,1,hb,ij,2). Similarly, if gij=8 or 7, one of the possible haplotype pairs is also equally likely to be reassigned to (hb,ij,1,hb,ij,2). The other selected haplotype pairs will be mutated in the same way, but independently. It is easy to see that the transition is symmetric, in the sense that  .

.

Peer Learning Operator

The peer learning operator works as follows.

1. Randomly select one haplotype—say, hb,u,v—from the set {hb,1,1,hb,1,2;…;hb,n,1,hb,n,2}.

2. Randomly select one haplotype—say, hb,s,t—from the set

with probability  , where wb,i,j=exp{-d(hb,u,v,hb,i,j)/tsel}, d(hb,u,v,hb,i,j) is the number of different haplotypes at the first

, where wb,i,j=exp{-d(hb,u,v,hb,i,j)/tsel}, d(hb,u,v,hb,i,j) is the number of different haplotypes at the first  loci of hb,u,v and hb,i,j, and tsel is the so-called “selection temperature.”

loci of hb,u,v and hb,i,j, and tsel is the so-called “selection temperature.”

3. For each genotype guj, if guj=0 or 1, we keep hb,uj,v unchanged; if guj=2, 9, 8, or 7 and hb,uj,v=hb,sj,t, we keep hb,uj,v unchanged with probability pl and change hb,uj,v to hb,sj,t with probability 1-pl; if guj=2, 9, 8, or 7 and hb,uj,(v)≠hb,sj,t, we keep hb,uj,v unchanged with probability 1-pl and change hb,uj,v to hb,sj,t with probability pl. We update the complementary pair of hb,u,v accordingly, such that they are compatible with gu.

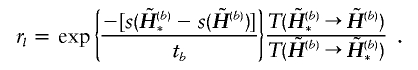

4. According to the Metropolis-Hastings rule, accept the new haplotype pair with probability min{1,rl}, where

|

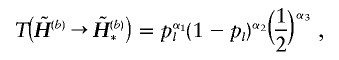

Here, the transition probability equals

|

where α1 is the total number of the common haplotypes of  and

and  at the heterozygous and missing loci, α2 is the total number of the different haplotypes of

at the heterozygous and missing loci, α2 is the total number of the different haplotypes of  and

and  at the heterozygous and missing loci, and α3 counts the total number of times that the haplotype values in the complementary haplotype pair of hb,u,v are randomly assigned. The pl is a user-specified parameter. We set pl=0.9 for all examples in this article. The transition probability

at the heterozygous and missing loci, and α3 counts the total number of times that the haplotype values in the complementary haplotype pair of hb,u,v are randomly assigned. The pl is a user-specified parameter. We set pl=0.9 for all examples in this article. The transition probability  can be computed similarly.

can be computed similarly.

This operator makes it possible for haplotypes to coalesce together very fast if it is feasible.

Appendix B : Extrapolation

The extrapolation operator extrapolates  to

to  by attaching the haplotype pairs compatible with G(b+1). We call a haplotype “original” if it first appears in

by attaching the haplotype pairs compatible with G(b+1). We call a haplotype “original” if it first appears in  in some scanning order—for instance, the natural order (hb,1,1,hb,1,2;…; hb,n,1,hb,n,2) used in this article, where (hb,i,1,hb,i,2) is the haplotype pair of the ith genotype in

in some scanning order—for instance, the natural order (hb,1,1,hb,1,2;…; hb,n,1,hb,n,2) used in this article, where (hb,i,1,hb,i,2) is the haplotype pair of the ith genotype in  ; otherwise, we call it “duplicate.” The extrapolation proceeds, in the prefixed scanning order, as follows. If a haplotype and its complementary pair are both “original,” it is extrapolated independently—that is, if gij is a heterozygous or missing allele, then (hb+1,ij,1,hb+1,ij,2) is equally likely to be set to one of the possible haplotype pairs. If a haplotype is “duplicate,” then it will be extrapolated according to the corresponding original copy. Note that, in this case, the extrapolation for the corresponding original copy has been finished. For example, if hb,u,v is a duplicate of hb,s,t, and if guj is a heterozygous or missing allele, then hb+1,uj,v will be set to the same value as hb+1,sj,t with probability pe and will be set to a value that differs from hb+1,sj,t with probability 1-pe. The complementary pair of hb+1,uj,v will be set accordingly, such that the pair is compatible with gu. We usually set pe to a large value—say, 0.95—for all examples in this article. Obviously, the extrapolation operator will provide a good starting point for the simulation from the distribution

; otherwise, we call it “duplicate.” The extrapolation proceeds, in the prefixed scanning order, as follows. If a haplotype and its complementary pair are both “original,” it is extrapolated independently—that is, if gij is a heterozygous or missing allele, then (hb+1,ij,1,hb+1,ij,2) is equally likely to be set to one of the possible haplotype pairs. If a haplotype is “duplicate,” then it will be extrapolated according to the corresponding original copy. Note that, in this case, the extrapolation for the corresponding original copy has been finished. For example, if hb,u,v is a duplicate of hb,s,t, and if guj is a heterozygous or missing allele, then hb+1,uj,v will be set to the same value as hb+1,sj,t with probability pe and will be set to a value that differs from hb+1,sj,t with probability 1-pe. The complementary pair of hb+1,uj,v will be set accordingly, such that the pair is compatible with gu. We usually set pe to a large value—say, 0.95—for all examples in this article. Obviously, the extrapolation operator will provide a good starting point for the simulation from the distribution  .

.

Electronic-Database Information

The URLs for data presented herein are as follows:

- dbSNP Home Page, http://www.ncbi.nih.gov/SNP/ (for the 65 SNPs in )

- Online Mendelian Inheritance in Man (OMIM), http://www.ncbi.nih.gov/Omim/ (for the 36 candidate genes in )

- Research at Brigham and Women's Hospital download site, http://research.bwh.harvard.edu/ca16ref.doc (for a list of references concerning the 65 SNPs in , in Microsoft Word format)

References

- Bugawan TL, Mirel DB, Valdes AM, Panelo A, Pozzilli P, Erlich HA (2003) Association and interaction of the IL4R, IL4, and IL13 loci with type 1 diabetes among Filipinos. Am J Hum Genet 72:1505–1514 10.1086/375655 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng S, Grow MA, Pallaud C, Klitz W, Erlich HA, Visvikis S, Chen JJ, Pullinger CR, Malloy MJ, Siest G, Kane JP (1999) A multilocus genotyping assay for candidate markers of cardiovascular disease risk. Genome Res 9:936–949 10.1101/gr.9.10.936 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cho JH, Nicolae DL, Gold CT, Fields MC, Labuda MC, Rohal PM, Pickles MR, Qin L, Fu Y, Mann JS, Kirschner BS, Jabs EW, Weber J, Hanauer SB, Bayless TM, Brant SR (1998) Identification of novel susceptibility loci for inflammatory bowel disease on chromosomes 1p, 3q, and 4q: evidence for epistasis is between 1p and IBD1. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 95:7502–7507 10.1073/pnas.95.13.7502 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clayton D (2002) Choosing a set of haplotype tagging SNPs from a larger set of diallelic loci. http://www-gene.cimr.cam.ac.uk/clayton/software/stata/htSNP/htsnp.pdf (accessed November 12, 2003)

- Cordell HJ, Clayton DG (2002) A unified stepwise regression procedure for evaluating the relative effects of polymorphisms within a gene using case/control or family data: application to HLA in type 1 diabetes. Am J Hum Genet 70:124–141 10.1086/338007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cordell HJ, Todd JA, Bennett ST, Kawagushi Y, Farrall M (1995) Two-locus maximum lod score analysis of a multifactorial trait: joint consideration of IDDM2 and IDDM4 with IDDM1 in type 1 diabetes. Am J Hum Genet 57:920–934 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cordell J, Todd JA (1995) Multifactorial inheritance in type 1 diabetes. TIG 11:499–504 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cordell J, Todd JA, Hill NJ, Lord CJ, Lyons PA, Peterson LB, Wicker LS, Clayton DG (2001) Statistical modelling of interlocus interactions in a complex disease: rejection of the multiplicative model of epistasis in type 1 diabetes. Genetics 158:357–367 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cordell HJ, Wedig GC, Jacobs KB, Elston RC (2000) Multilocus linkage tests based on affected relative pairs. Am J Hum Genet 66:1273–1286 10.1086/302847 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cox NJ, Frigge M, Nicolae DL, Concannon P, Hanis CL, Bell GI, Kong A (1999) Loci on chromosomes 2 (NIDDM1) and 15 interact to increase susceptibility to diabetes in Mexican Americans. Nat Genet 21:213–215 10.1038/6002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cox NJ, Wapelhorst B, Morrison VA, Johnson L, Pinchuk L, Spielman RS, Todd JA, Concannon P (2001) Seven regions of the genome show evidence of linkage to type 1 diabetes in a consensus analysis of 767 multiplex families. Am J Hum Genet 69:820–830 10.1086/323501 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cucca F, Dudbridge F, Loddo M, Mulargia AP, Lampis R, Angius E, De Virgiliis, Koeleman BP, Bain SC, Barnett AH, Gilchrist F, Cordell H, Welsh K, Todd JA (2001) The HLA-DPB1-associated component of the IDDM1 and its relationship to the major loci HLA-DQB1, -DQA1, and -DRB1. Diabetes 50:1200–1205 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dassen W, Spiering W, de Leeuw P, Smits P, Dijk WA, Spruijt H, Gommer E, Bonnemayer C, Doevendans PA (2001) Unravelling gene interactions to find the cause of artherosclerosis, a multigenic disease, using an artificial neural network. Comput Cardiol 28:373–376 [Google Scholar]

- Drysdale CM, McGraw DW, Stack CB, Stephens JC Judson RS, Nadabalan K, Arnold K, Ruano G, Liggett SB (2000) Complex promoter and coding region β2-adrenergic receptor haplotypes alter receptor expression and predict in vivo responsiveness. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 97:10483–10488 10.1073/pnas.97.19.10483 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fain PR, Eisenbarth GS (2001) Type 1 diabetes, autoimmunity and the MHC. In: Lowe WL Jr (ed) Genetics of diabetes mellitus. Kluwer Academic Publishers, Boston, pp 43–64 [Google Scholar]

- Flori L, Sawadogo S, Esnault C, Delahaye NF, Fumoux F, Rihet P (2003) Linkage of mild malaria to the major histocompatibility complex in families living in Burkina Faso. Hum Mol Genet 12:375–378 10.1093/hmg/ddg033 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friday RP, Trucco M, Pietropaolo M (1999) Genetics of type 1 diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Nutr Metab 12:3–26 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hastings WK (1970) Monte Carlo sampling methods using Markov chains and their applications. Biometrika 57:97–109 [Google Scholar]

- Jones DS (1979) Elementary information theory. Clarendon Press, Oxford [Google Scholar]

- Kirkpatrick S, Gelatt CD Jr, Vecchi MP (1983) Optimization by simulated annealing. Science 220:671–680 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koeleman BP, Dudbridge F, Cordell HJ, Todd JA (2000) Adaptation of the extended transmission/disequilibrium test to distinguish disease associations of multiple loci: the conditional extended transmission/disequilibrium test. Ann Hum Genet 64:207–213 10.1046/j.1469-1809.2000.6430207.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCullagh P, Nelder JA (1989) Generalized linear models, 2nd ed. Chapman & Hall, London [Google Scholar]

- Metropolis N, Rosenbluth AW, Rosenbluth MN, Teller AH, Teller E (1953) Equations of state calculations by fast computing machine. J Chem Phys 21:1087–1091 [Google Scholar]

- Noble JA, Valdes AM, Bugawan TL, Apple RJ, Thomson G, Erlich HA (2002) The HLA class I A locus affects susceptibility to type 1 diabetes. Hum Immunol 63:657–664 10.1016/S0198-8859(02)00421-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pugliese A (2001) Genetic factors in type 1 diabetes. In: Lowe WL Jr (ed) Genetics of diabetes mellitus. Kluwer Academic Publishers, Boston, pp 25–42 [Google Scholar]

- Schranz DB, Lernmark A (1998) Immunology in diabetes: an update. Diabetes Metab Rev 14:3–29 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stephens M, Smith NJ, Donnelly P (2001) A new statistical method for haplotype reconstruction from population data. Am J Hum Genet 68:978–989 10.1086/319501 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Storey JD, Tibshirani R (2003) Statistical significance for genome-wide experiments. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 100:9440–9445 10.1073/pnas.1530509100 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sudbery P (1998) Human molecular genetics. Addison Wesley Longman, Harlow [Google Scholar]

- Valdes AM, Thomson G (1997) Detecting disease-predisposing variants: the haplotype method. Am J Hum Genet 60:703–716 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vatay A, Yang Y, Chung EK, Zhou B, Blanchong CA, Kovács M, Karádi I, Füst G, Romics L, Varga L, Yu Y, Szalai C (2003) Relationship between complement components C4A and C4B diversities and two TNFA promoter polymorphisms in two healthy Caucasian populations. Hum Immunol 64:543–552 10.1016/S0198-8859(03)00036-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wall JD, Pritchard JK (2003) Haplotype blocks and linkage disequilibrium in the human genome. Nat Rev Genet 4:587–597 10.1038/nrg1123 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weir BS (1996) Genetic data analysis II. Sinauer Associates, Massachusetts [Google Scholar]

- Zhang J, Liang F, Hoehe M, Vingron M (2001) On haplotype reconstruction for diploid organisms. EURANDOM Report-2001-026 [Google Scholar]