Abstract

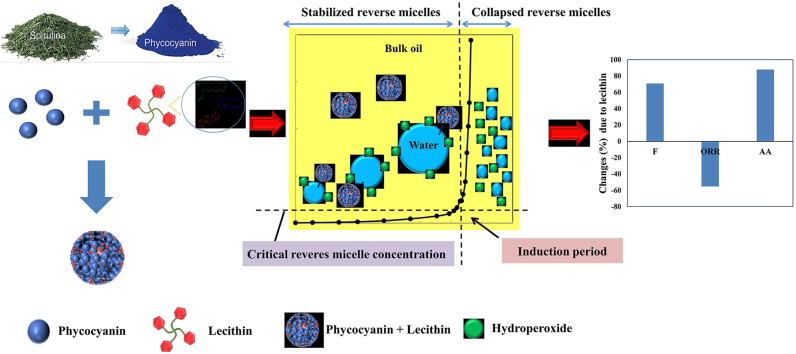

This study compared the inhibitory mechanism of phycocyanin in sunflower oil with its activity in a sunflower oil-in-water emulsion. Additionally, the impact of lecithin on the inhibitory mechanism of phycocyanin in sunflower oil was evaluated. A sigmoidal model effectively described the oxidation kinetics. In both sunflower oil and sunflower oil-in-water emulsion, phycocyanin pro-oxidatively attacked lipid hydroperoxides besides inhibiting lipid hydroperoxides. The antioxidant activity of sunflower oil containing phycocyanin and lecithin was 2.2-fold greater than that of sunflower oil containing lecithin alone. The addition of lecithin enhanced the interfacial activity of phycocyanin and altered its hydrogen donating and electron transfer mechanisms. Also, by comparing the reverse micelles size samples of sunflower oil samples containing lecithin, we discovered that lecithin can enhance the potency of phycocyanin by boosting the ability of reverse micelles to incorporate lipid hydroperoxides within their structure.

Keywords: Interfacial activity, Kinetic parameters, Lecithin, Phycocyanin

Graphical abstract

Highlights

-

•

The antioxidant mechanism of action of phycocyanin on inhibiting the oxidation was investigated.

-

•

Initiation phase and propagation phase kinetic parameters were determined.

-

•

Peroxidation was in parallel with changes in water, interfacial tension, and particle size.

-

•

A synergism was observed between phycocyanin and lecithin as surfactant.

-

•

The impact of interfacial activity of lecithin in phycocyanin's performance was investigated.

1. Introduction

The interaction of oxygen with fats containing double bonds (unsaturated fatty acids) in foods, known as lipid oxidation, significantly degrades the nutritional value and sensory properties of oils and fats (Baydır et al., 2023; Zhao et al., 2024). Sunflower oil contains compounds with surface activity (i.e., diacylglycerols, free fatty acids, monoacylglycerols, lipid hydroperoxides (ROOH), and phospholipids) and little water. In the presence of water, surface active agents induce the formation of reverse micelles within sunflower oil. These structures have a unique internal environment of encapsulated water surrounded by oil-interacting tails. Notably, hydroperoxides (ROOH) formed during oxidation display surface activity. This characteristic drives their accumulation at the oil-water interface of the reverse micelles. Furthermore, metal ions residing within the aqueous core can act as catalysts, promoting the decomposition of interfacial ROOH into free radicals, thereby accelerating the oxidation process (Toorani et al., 2024).

In bulk oil, polar antioxidants have higher affinity than nonpolar ones to locate at the interfacial area of reverse micelles and inhibit lipid oxidation efficiently. Besides, the partitioning of ROOH at interfacial area of reverse micelles in bulk oils creates a concentrated reaction zone, facilitating the targeted action of antioxidants to reduce lipid oxidation efficiently. In oil-in-water emulsions, oxidation is believed to take place at the interface of the oil droplets, where unsaturated fatty acids in the oil phase come together with solubilized compounds of the aqueous phase, such as transition metal ions. Accordingly, surface active antioxidants that have a high affinity for concentrating at the interfacial area of reverse micelles in sunflower oil or interfacial areas of sunflower oil-in-water emulsions can influence the lipid oxidation rate by scavenging free radicals and interfering with hydroperoxide-metal interactions. Therefore, researchers are exploring the manipulation of interfacial composition for enhanced oxidative stability in emulsions. The incorporation of surface active molecules with antioxidant properties emerges as a promising strategy to directly inhibit oxidation at the oil-water interface (Keramat et al., 2023; Lehtinen et al., 2017; Toorani et al., 2024).

Proteins are amphiphilic molecules that can adsorb onto the surfaces of oil droplet surfaces that stabilize them against aggregation. In addition to their physical role in stabilizing emulsions, certain amino acids present in food proteins exhibit antioxidant activity due to their free radical scavenging, binding, or chelating effects. Proteins containing exposed tryptophan, cysteine, and methionine residues have been demonstrated to exhibit antioxidant properties, likely attributed to the free radical scavenging capabilities of these amino acids (Zhu et al., 2018).

Phycocyanin, a natural blue pigment-protein complex derived from spirulina algae, become a safe and versatile food coloring. Phycocyanin boasts a remarkable concentration of 10–17 g per 100 g of cell dry weight. This natural colorant has been approved for use in food by the US Food and Drug Administration and is considered non-toxic according to European Union regulations. The water solubility of phycocyanin makes it an ideal ingredient for a wide range of food and beverage applications. It lends its eye-catching blue hue to everything from ice creams and candies to chewing gum and other sweet treats, adding a touch of vibrancy and visual appeal. Beyond its aesthetic value, phycocyanin offers potential health benefits, making it a compelling choice for health-conscious consumers (Martelli et al., 2014). Research suggests it possesses antioxidant, immune-boosting, neuroprotective, and anticancer properties (Fernandes et al., 2023). These potential health benefits, coupled with its function as a natural blue dye, are driving increased demand for phycocyanin in food and beverage applications (Alavi et al., 2023).

Lecithin is an amphiphilic compound that can protect vegetable oils against oxidation. Studies show that lecithin is a multi-functional protector against this process (Szuhaj, 2019). It helps regenerate antioxidants, traps metals that speed up oxidation and forms a barrier between the oil and air (Lehtinen et al., 2017). Lecithin also aids in creating structures called reverse micelles, further enhancing the oil's resistance to oxidation. These micelles function as small containers, encapsulating and delivering antioxidants, thereby enhancing their ability to neutralize harmful molecules within the oil (Cardenia et al., 2011). The presence of lecithin significantly increases the size and number of these micelles, boosting their effectiveness. Consequently, the acceptance capacity of ROOHs in reverse micelles structure may increase. Due to their precise location in the micro-micelle interfaces, relatively polar antioxidants can interact more with ROOHs. The physical function of lecithin in this process can extend the duration of the induction period (IP) (Mansouri et al., 2020; Xu et al., 2019)

A key area of investigation in lipid oxidation mitigation remains the impact of surface active agents on antioxidant activity at oil-water interfaces. Several studies have been done the biological activity of phycocyanin. However, its inhibitory mechanism in sunflower oil has not yet been investigated. Besides, the impact of lecithin on the inhibitory mechanism and antioxidant pathways of phycocyanin has not yet been studied. This research investigated the antioxidant mechanisms of phycocyanin in sunflower oil compared to that of sunflower oil-in-water emulsion. Also, the inhibitory mechanism of phycocyanin in the presence of lecithin, a phospholipid surfactant, was studied. A sigmoidal model was employed to analyze various oxidation indices, providing insights into the initiation and propagation phases of lipid oxidation. To clarify the physicochemical events occurring during sunflower oil oxidation in the presence of phycocyanin alone and in combination with lecithin, changes in reverse micelles size, water content, and interfacial tension sunflower oil samples were measured.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Materials

Sunflower oil was acquired from Roghan-e-Narges Company (Shiraz, Iran). Food-grade phycocyanin from Spirulina platensis was purchaced from Xian Pincredit Bio -Tech Co. Ltd (Juanjo, China). Lecithin, potassium dihydrogen phosphate, Tween 80, ammonium thiocyanate, sodium carbonate, 1,1-diphenyl-2-picrylhydrazyl (DPPH), di-potassium hydrogen phosphate were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich Company (St. Louis, MO). Methanol, hydrochloric acid, n-heptane, and chloroform were acquired from Merck Company (Darmstadt, Germany).

2.2. Radical scavenging potency (RSP) of phycocyanin

The antioxidant potential of phycocyanin was assessed by measuring its hydrogen atom or electron donation ability using the DPPH assay (Gabr et al., 2020). This assay evaluates the ability of the extract to reduce DPPH radical. picrylhydrazyl (DPPH). Briefly, 3 mL of the phycocyanin sample was blended with methanolic DPPH solution (1 mL, 0.1 mM). After keeping 0.5 h in the dark, the absorbance at 517 nm was determined. Percent scavenging activity was calculated using a standard formula, with a control sample containing only DPPH solution for comparison. The RSP is calculated by Eq. (1).

| Eq. (1) |

A0 represents the absorbance of the sample containing mixture of phycocyanin and DPPH solution, while Ac is the absorbance of the control sample (DPPH solution).

2.3. Partition coefficient (log P) of phycocyanin

A phycocyanin solution (0.3 mM) in 1-octanol was prepared and kept maintained at 60 °C for 60 min. Then the absorbance value was determined at 204 nm (A0). Equal volume of acetate buffer (0.1 M, pH 7) was mixed with phycocyanin solution (0.3 mM). Then, the mixture was vortexed for 60 s. The absorbance value of the 1-octanol layer was measured after 1 h (Ax) (Asnaashari et al., 2014). The log P value of phycocyanin was calculated by Eq. (2).

| Eq. (2) |

2.4. Purification of sunflower oil

An adsorption chromatography column was applied for purification of sunflower oil and eliminating any compounds that might interfere with phycocyanin activity. The purification process was repeated twice (Keramat et al., 2022).

2.5. Sunflower oil preparation

Phycocyanin was solubized in acetone. Then, phycocyanin was incorporated into purified sunflower oil at concentrations of 0%, 0.02%, 0.04%, 0.06%, and 0.08% (w/w oil). In the case of samples containing lecithin, 0.05% (w/w oil) of lecithin was dissolved in ethyl acetate (1:10 (w/v)). Then, the mixture was stirred for 60 min at 45 ± 3 °C. After that, purified sunflower oil was gradually added to the mixture and stirred for 15 min. Ethyl acetate was removed under vacuum. Finally, phycocyanin at 0%, 0.02%, 0.04%, 0.06%, and 0.08% (w/w oil) concentrations was incorporated individually into the purified sunflower oil containing lecithin. The final concentration of lecithin in sunflower oil was 0.05% (Keramat et al., 2022).

2.6. Sunflower oil-in-water emulsion preparation

The emulsion phase inversion method was applied to prepare sunflower oil-in-water emulsion samples. Sunflower oil was mixed with Tween 80 using a magnetic stirrer at 750 rpm. Tween 80 with purified sunflower oil for 30 min. Phycocyanin was dissolved in acetone and added to the mixture of purified sunflower oil and Tween 80 at 0%, 0.02%, 0.04%, 0.06%, and 0.08% (w/w oil) concentration. Then, the acetone was eliminated from the mixture of purified sunflower oil and Tween 80 under a stream of nitrogen. The potassium phosphate buffer solution (0.040 mol/L, pH 7) was added to the above mixture at the rate of 310 μL/min while the mixture was stirred at 750 rpm (Keramat et al., 2022; Ostertag et al., 2012). The s particle size of unflower oil-in-water emulsion was measured to be 181.05 ± 0.49 nm.

2.7. Oxidation experiment

To oxidize the purified sunflower oil, a kinetic regime under atmospheric air conditions was employed, ensuring that the oxygen concentration did not influence the oxidation rate (Farhoosh, 2005). Sunflower oil and sunflower oil-in-water emulsion samples containing 0%, 0.02%, 0.04%, 0.06%, and 0.08% (w/w) phycocyanin as well as sunflower oil samples containing combinations of lecithin (0.05% w/w) and phycocyanin (0%, 0.02%, 0.04%, 0.06%, and 0.08% w/w) were stored at at 55 °C. To study the oxidation kinetics of sunflower oil samples, the oxidation test was conducted until the peroxide value curve plateaued after reaching a specific point. The peroxide value (PV) of each sample was measured during the storage period. For measuring the PV, 300 μL of each sample was collected using a micropipette. The PV (meq/kg) was measured using spectrophotometry at 500 nm (Shantha and Decker, 1994).

2.8. Kinetic study

The kinetic curve of ROOH production in the initiation and propagation phases were described using a sigmoidal model (Eq. (3)).

| Eq. (3) |

where C (mM−1) is the integration constant, nf (h−1) is the pseudo-first-order rate constant of ROOH formation, and nd (mM−1h−1) is the pseudo-second-order rate constant of ROOH decomposition during the propagation phase (Farhoosh, 2021a).

The induction period (IP, h) was calculated using Eq. (4).

| Eq. (4) |

The oxidation rate ratio (ORR), effectiveness factor (F), and antioxidant activity (AA) are were applied to elucidate the effect of antioxidants (AH) on sunflower oil oxidation in the initiation phase (Eq. (5)).

| Eq. (5) |

where IP0 is the IP value of the control sample and IPAH is the IP value of sample containing phycocyanin. Peroxidation rates in the absence (W0) and presence (WAH) of phycocyanin in the initiation phase were determined using the slopes ROOH curves against time in the initiation phase. The W0 and WAH values were stated as mM h−1 (1 meq/kg = 0.504 mM h−1). Eq. (6) was applied to determine the ORR value.

| Eq. (6) |

The antioxidant activity (AA) indicates the ability of phycocyanin to both enhance the IP value and reduce the WAH value, compared to the control sample. This parameter was determined by Eq. (7).

| Eq. (7) |

Eq. (8) was applied to calculate the average rate of phycocyanin consumption (rAH).

| Eq. (8) |

The time when the production rate of ROOH reaches its highest value (Tn) was calculated according to Eq. (9).

| Eq. (9) |

The highest ROOH concentration (ROOHn, mM) was determined according to Eq. (10).

| Eq. (10) |

Eq. (11) was applied to determine the highest rate of ROOH production (Wn, mM h−1).

| Eq. (11) |

Eq. (12) was applied to determine the propagation oxidizability (Wn, h−1).

| Eq. (12) |

Eq. (13) was applied to calculate the time that the propagation phase terminates (EP, h).

| Eq. (13) |

Eq. (14) was applied to calculate the propagation period (PP, h).

| PP = EP-IP | Eq. (14) |

Eq. (15) was applied to calculate the phycocyanin efficiency in the propagation phase (Fp).

| Eq. (15) |

PPc and PPAH values are the PP values of the control sample and sample containing phycocyanin, respectively.

Eq. (16) was applied to calculate the ROOH production rate (ORf) in the propagation phase.

| Eq. (16) |

where nf, AH and nf, C values are the nf values of the sample containing phycocyanin and the nf value of the control sample, respectively.

Eq. (17) was applied to calculate the ROOH decomposition rate in the propagation phase (ORd).

| Eq. (17) |

where nd, AH and nd, C values are the nd values of the sample containing phycocyanin and the nd value of the control sample, respectively.

Eq. (18) was applied to calculate the inhibitory action of phycocyanin against the ROOH production (If).

| Eq. (18) |

Eq. (19) was applied to calculate the inhibitory effect of phycocyanin (Id) against the ROOH decomposition (Farhoosh, 2021b).

| Eq. (19) |

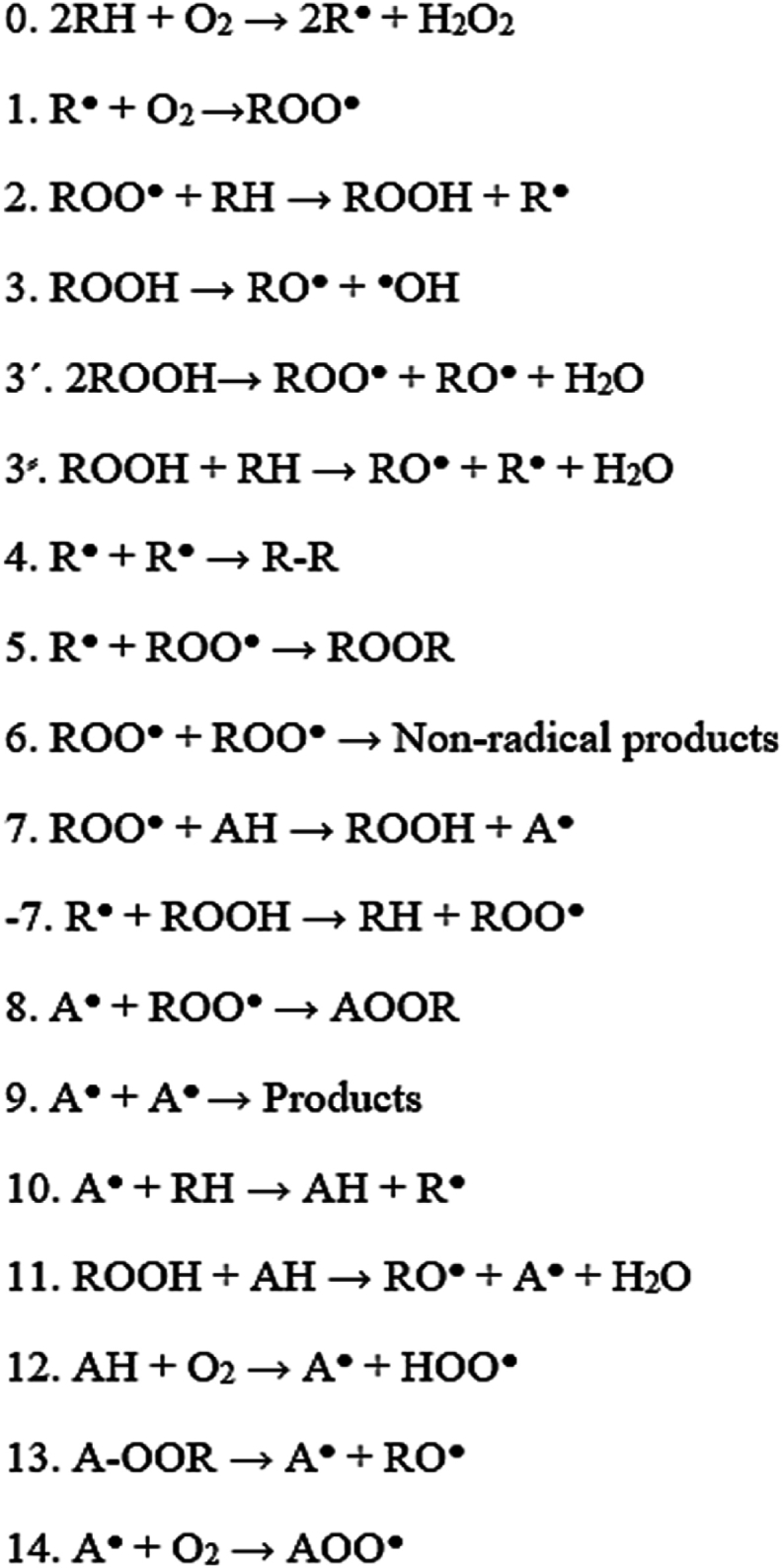

2.9. Inhibitory mechanism of phycocyanin

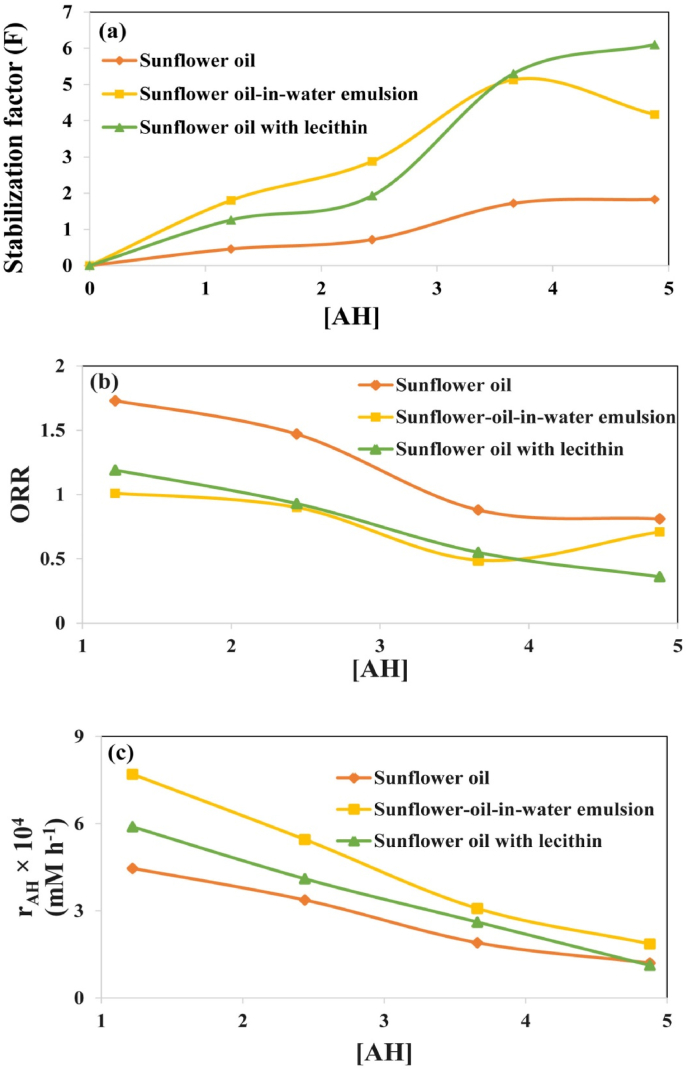

The inhibitory mechanism of phycocyanin is the result of the phycocyanin (A) and radicals (A●) taking part in reactions are shown in Fig. 1. The F value shows the phycocyanin capacity for inhibiting peroxidation by taking part in the primary reaction of chain termination (reaction 7, Fig. 1). A linear correlation between the F value and the initial phycocyanin concentration [AH]0 shows that phycocyanin is primarily involved in reaction 7. A nonlinear correlation between F value and [AH]0 shows that phycocyanin involves in the side reactions of chain initiation (reactions 11 and/or 12 in Fig. 1) in addition to involving in reaction 7.

Fig. 1.

Oxidation reactions in absence (0–6) and presence (7–14) of phycocyanin (AH). ROOH, lipid hydroperoxide; RH, lipid reactant; A●, phycocyanin radical; ROO●, peroxyl radical; R●, lipid radical; RO●, alkoxy radical.

Eq. (20) is applied to elucidate the phycocyanin participation in reactions 11 and 12.

| Eq. (20) |

where Keff is the rate constant of phycocyanin consumption in reactions 11 and 12. The f parameter (stoichiometric coefficient of inhibition) is the number of radicals inhibited by one antioxidant molecule and the Wi (M s−1) value is the mean initiation rate during IP.

A linear correlation between rAH value and phycocyanin concentration (AH) at n = 1 shows that phycocyanin involves in one of the reactions 11 or 12, while a linear correlation between rAH value and phycocyanin concentration at n = 2 shows that phycocyanin involves in both of the reactions 11 and 12.

Eq. (21) can be applied to evaluate the participation of phycocyanin radicals in the chain reaction −7, 10, and 14 (Toorani et al., 2019).

| Eq. (21) |

A linear correlation between WAH value and phycocyanin concentration at n = −1 shows that the phycocyanin radical is not involved in the chain reaction. A linear correlation at n = −0.5 shows that phycocyanin radical is involved in the reaction 10. The nonlinear correlation between WAH value and phycocyanin concentration at n = −1 and n = −0.5 shows that the phycocyanin radicals were involved in more than one reaction of chain propagation (Denisov and Khudyakov, 1987).

2.10. Water content

A coulometric Karl Fischer titrator (KF Titrino, Metrohm, Herisau, Switzerland) was used to measure the changes in the amount of water of sunflower oil samples during storage. This measurement adhered to the established ASTM E1064 standard protocol (ASTM, 2016; Mansouri et al., 2020).

2.11. Particle size

The particle size distribution of sunflower oil samples was determined using dynamic light scattering equipment (SZ-100 Nanopartica Series, Japan). The tests were conducted at 25 °C and a scattering angle of 173°. The refractive index and dielectric constant of sunflower oil were measured to be 1.47 ± 0.02 and 3.79 ± 0.05, respectively (Mansouri et al., 2020).

2.12. Interfacial tension

Interfacial tension measurements between two immiscible liquids were conducted at 25 °C using a modern tensiometer (KSV703D, Germany) equipped with a ring probe (Di Mattia, Sacchetti, Mastrocola, Sarker and Pittia, 2010). The surface tensions of purified sunflower oil and Milli-Q water were measured to be 30.54 ± 0.07 mN/m and 72.75 ± 0.01 mN/m, respectively. While the Milli-Q water's surface tension was assumed to remain constant throughout the experiments, the oil samples were varied based on the specific treatment and peroxidation stage.

2.13. Statistical analysis

All assays were performed in three replicates. Significant differences among the means were identified by one-way analysis of variance. Comparison between the mean values were carried out by Duncan's multiple range test (P < 0.05). SPSS 16 software (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL) was employed for statistical analysis, while Microsoft Excel and Curve Expert softwares were utilized for regression modeling.

3. Results and discussion

3.1. Radical scavenging potency of phycocyanin

The DPPH assay, a common method to assess antioxidant capacity, measures the ability of a molecule to donate a hydrogen atom, neutralizing the stable DPPH radical. This reduction transforms the radical from purple to yellow, and the decrease in absorbance at 517 nm reflects the scavenging activity. Our food-grade phycocyanin solution effectively scavenged DPPH radical, demonstrating its antioxidant properties. The scavenging activity increased by increasing the concentration of phycocyanin. The IC₅₀ value, representing the phycocyanin concentration required to inhibit 50% of the initial DPPH radical concentration (Keramat and Golmakani, 2024), was determined to be 5.10 ± 0.03 mg/mL. The antioxidant activity of phycocyanin depends on the extraction method, species type, and purity. Different techniques can yield phycocyanin with varying structural integrity and purity levels, ultimately affecting its antioxidant capabilities. Studies comparing phycocyanin from different sources support this notion. For instance, Patel et al. (2006) found Lyngbya-derived phycocyanin to be a more potent peroxyl radical inhibitor (IC50 = 6.63 μM) compared to Spirulina sp. (IC50 12.15 μM) and Phormidium sp. (IC50 = 12.74 μM). Renugadevi et al. (2018) demonstrated that the IC50 value of phycocyanin from Geitlerinema sp. TRV57 was found to be 185 μg/mL for anti-lipid peroxidation assay.

3.2. Evaluating kinetic parameters

Our study examined how phycocyanin affects the oxidation of sunflower oil. Fig. 1S shows how phycocyanin alters the rate of PV of sunflower oil samples, sunflower oil samples containing lecithin, and sunflower oil-in-water emulsion samples during storage at 55 °C. Initially, free radicals (alkyl radicals) with low redox potential can only convert to peroxyl radicals. These peroxyl radicals then attack the sunflower oil molecules, initiating the oxidation process (Fig. 1). We assessed the efficiency of phycocyanin in sunflower oil through measuring various parameters (IP (induction period), F (effectiveness factor), ORR (oxidation rate ratio), and AA (antioxidant activity)), summarized in Table 1. The results revealed that phycocyanin significantly extended the IP and decreased the formation rate of peroxides (Table 1, P < 0.05).

Table 1.

The kinetic parameters characterizing the inhibited peroxidation of sunflower oil, sunflower-oil-in water emulsion, and sunflower oil with lecithin in the absence (control) and presence of different concentrations of phycocyanin at 55 °C.

| Kinetic parameter | IP (h) | rAH0 (mM h−1) | F | WAH (mM h−1) | ORR | AA | Keff (s−1) | Wi/f (M s−1) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sunflower oil | ||||||||

| Control | 58.02 ± 5.53ea | – | – | 0.12 ± 0.01a | – | – | – | – |

| Phycocyanin (0.02%, w/w) | 110.33 ± 1.23d | 4.26 ± 0.51a | 0.45 ± 0.11c | 0.09 ± 0.02b | 1.82 ± 0.01a | 0.57 ± 0.20b | 8.96 ± 0.04ba |

2.10 ± 0.12a |

| Phycocyanin (0.04%, w/w) | 149.76 ± 1.29c | 3.77 ± 1.08a | 0.72 ± 0.12b | 0.10 ± 0.01b | 1.47 ± 0.02b | 0.85 ± 0.09b | ||

| Phycocyanin (0.06%, w/w) | 378.56 ± 6.75b | 1.70 ± 2.04b | 1.73 ± 0.82a | 0.06 ± 0.00c | 0.88 ± 0.01c | 3.11 ± 0.10a | ||

|

Phycocyanin (0.08%, w/w) |

404.61 ± 13.12a |

1.38 ± 0.72b |

1.82 ± 0.40a |

0.05 ± 0.00c |

0.81 ± 0.00c |

2.98 ± 0.01a |

||

| Sunflower oil-in-water emulsion | ||||||||

| Control | 40.53 ± 3.01d | – | – | 0.28 ± 0.04a | – | – | – | – |

| Phycocyanin (0.02%, w/w) | 72.25 ± 5.61c | 7.70 ± 0.61a | 1.80 ± 0.11d | 0.27 ± 0.01ab | 1.01 ± 0.26a | 1.70 ± 0.12c | 12.68 ± 0.35a |

1.73 ± 0.00ab |

| Phycocyanin (0.04%, w/w) | 111.50 ± 11.52b | 5.45 ± 0.92b | 2.88 ± 0.23c | 0.23 ± 0.07b | 0.90 ± 0.27ab | 2.89 ± 0.10b | ||

| Phycocyanin (0.06%, w/w) | 196.62 ± 19.02a | 3.88 ± 0.65c | 5.13 ± 0.12a | 0.13 ± 0.08c | 0.49 ± 0.08c | 4.13 ± 0.63a | ||

|

Phycocyanin (0.08%, w/w) |

165.48 ± 8.08ab |

2.16 ± 0.07d |

4.17 ± 0.07b |

0.19 ± 0.02bc |

0.71 ± 0.09b |

4.17 ± 0.41a |

||

| Sunflower oil with lecithin | ||||||||

| Control | 87.25 ± 6.06e | – | – | 0.14 ± 0.01a | – | – | – | – |

| Phycocyanin (0.02%, w/w) | 101.83 ± 3.11d | 5.89 ± 1.35a | 1.26 ± 0.14c | 0.12 ± 0.01b | 1.19 ± 0.11a | 2.98 ± 0.54c | 5.16 ± 0.00c | 1.03 ± 0.08b |

| Phycocyanin (0.04%, w/w) | 156.65 ± 4.60c | 4.10 ± 0.46a | 1.64 ± 0.85c | 0.12 ± 0.01b | 0.93 ± 0.22b | 2.19 ± 1.01c | ||

| Phycocyanin (0.06%, w/w) | 422.30 ± 12.10b | 2.60 ± 0.70b | 2.30 ± 0.11b | 0.10 ± 0.00b | 0.55 ± 0.22c | 5.64 ± 2.18b | ||

| Phycocyanin (0.08%, w/w) | 561.90 ± 7.45a | 1.12 ± 0.12b | 3.11 ± 0.48a | 0.09 ± 0.00b | 0.36 ± 0.00d | 6.60 ± 0.24a | ||

In each section and in each column, means with different superscript lowercase letters are significantly different (P < 0.05). IP: induction period, rAH: average rate of phycocyanin consumption, WAH: pseudo-zero order rate constant at the initiation stage, ORR: oxidation rate ratio during the initiation stage, AA: antioxidant activity, Keff: rate constant of antioxidant consumption in the side reactions of the chain initiation, and Wi/f: mean rate of initiation.

Mean ± SD (n = 3).

In sunflower oil, phycocyanin at 0.06% and 0.08% concentration showed higher AA values than other concentrations. This trend was also observed in the oil-in-water emulsion. In all investigated concentrations, the AA values of phycocyanin in the sunflower oil-in-water emulsion were higher than in the sunflower oil. Sunflower oil-in-water emulsion has a lower viscosity (2.11 ± 0.50 mPa s) than sunflower oil (47.57 ± 0.70 mPa s). This can enhance phycocyanin's mobility, facilitating its movement towards the interfacial area and subsequent reaction with peroxyl radicals in the sunflower oil-in-water emulsion (Keramat et al., 2023).

In sunflower oil, the AA value of phycocyanin reached the maximum amount of 3.11 at a concentration of 0.06%. This antioxidant performance can be related to a high number of hydroxyl groups in the phycocyanin molecule, which contributes to its inhibitory potential. High amounts of aspartic acid, alanine, glutamic acid, isoleucine, serine, glycine, arginine, and threonine were found in phycocyanin (Wu et al., 2016). The most of these compounds have been linked to increased levels of antioxidant activity.

At the concentration of 0.08%, the AA value decreased to 2.98. This reduction in AA value of phycocyanin at higher concentration may be related to the participation of phycocyanin molecules in the chain initiation reactions (reactions 11 and/or 12 in Fig. 1) in addition to its known antioxidant activity (reaction 7). The alkoxyl and hydroperoxyl radicals formed during chain initiation reactions can enhance the peroxidation rate.

To enhance the ability of phycocyanin to interact with reactive free radicals at interfacial area of sunflower oil reverse micelles, lecithin was introduced. Adding lecithin to the sunflower oil resulted in the longest IP (561.9 h) observed at a phycocyanin concentration of 0.08% (w/w), representing a remarkable 6.4-fold increase compared to the control. The effect of lecithin on the F, ORR, and AA values of sunflower oil samples containing 0.08% (w/w) phycocyanin is presented in Fig. 2S. While the ORR value decreased by 55.2%, the F value showed a more significant enhancement, increasing by 70.9% (Fig. 3S). The F value and ORR value are the indicators of hydrogen donating and electron transfer mechanisms of antioxidants, respectively (Toorani et al., 2024). These observations suggest that lecithin primarily influences the hydrogen donating mechanism of phycocyanin. The combined effect of the F value and ORR resulted in an impressive 54% increase in the overall antioxidant activity of phycocyanin at 0.08% (w/w) concentration due to the addition of lecithin. This synergistic effect can be due to the ability of lecithin to transfer hydrophilic phycocyanin (log P = −1.05) to the oil-water interface of reverse micelles, resulting in enhancing phycocyanin accessibility to peroxyl radicals (Keramat et al., 2022).

Fig. 2.

(a) Relationship between effectiveness factor (E) and concentration of phycocyanin [AH] during the peroxidation of sunflower oil with or without lecithin, (b) relationships between oxidation rate ratio (ORR) and concentration of phycocyanin [AH], and (c) relationship between the rate of phycocyanin consumption and [AH].

Fig. 3.

Dependence of WAH on [AH] (concentration of phycocyanin) during peroxidation process of sunflower oil, sunflower oil with lecithin, and sunflower oil-in-water emulsion.

Analysis of parameters related to the propagation phase further supported the antioxidant activity of phycocyanin. Notably, phycocyanin significantly reduced the nf (rate constant of hydroperoxide formation) and nd (rate constant of hydroperoxide decomposition) values during the propagation phase in both sunflower oil and sunflower oil-in-water emulsion (Table 2). In addition, the PP (propagation period) values of sunflower oil samples containing phycocyanin were significantly higher than that of the control sunflower oil sample (Table 2). For instance, at a concentration of 0.08% (w/w), the PP reached nearly 993.2 h, representing more than 2.30 times increase This observation suggests that a significant portion of phycocyanin molecules remained active during the propagation phase, implying that not all molecules were consumed completely during the IP. The effect of phycocyanin on increasing the PP of sunflower oil samples was increased by increasing phycocyanin concentration from 0.02% to 0.08% (w/w) (Table 2). The PP value of sunflower oil containing 0.02% (w/w) phycocyanin was not significantly higher than that of the control sunflower oil sample. This indicates that a significant amount of phycocyanin at 0.02% (w/w) concentration was consumed in the initiation phase.

Table 2.

Oxidation kinetic parameters of the propagation phase of sunflower oil, sunflower-oil- in water emulsion, and sunflower oil with lecithin in the absence (control) and presence of different concentrations of phycocyanin.

| Kinetic parameter | nf × 104 (h−1) | nd × 105 (mM−1 h−1) | Tmax (h) | Wn × 104 (h−1) | PP (h) | EP (h) | If | Id |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sunflower oil | ||||||||

| Control | 7.30 ± 0.19aa | 10.55 ± 2.13a | 315.88 ± 11.24d | 18.07 ± 0.12a | 450.68 ± 12.71d | 590.05 ± 0.61e | – | – |

| Phycocyanin (0.02%, w/w) | 6.50 ± 1.02b | 10.63 ± 1.65a | 396.95 ± 4.67cd | 16.45 ± 2.11b | 471.95 ± 6.51d | 705.82 ± 26.51d | 1.12 ± 0.04b | 1.20 ± 0.06d |

| Phycocyanin (0.04%, w/w) | 5.20 ± 0.19c | 8.91 ± 0.06b | 515.36 ± 6.61c | 12.92 ± 0.09c | 756.17 ± 10.10c | 903.74 ± 8.27c | 2.01 ± 0.19ab | 2.27 ± 0.10c |

| Phycocyanin (0.06%, w/w) | 3.11 ± 0.89d | 7.20 ± 0.23c | 676.70 ± 7.59b | 12.10 ± 1.59cd | 859.24 ± 9.89b | 1006.05 ± 87.62b | 2.57 ± 0.90a | 6.47 ± 0.24b |

| Phycocyanin (0.08%, w/w) | 3.30 ± 0.23d | 5.00 ± 0.54d | 867.54 ± 8.93a | 10.00 ± 1.07d | 993.17 ± 12.60a | 1367.54 ± 18.39a | 3.12 ± 0.77a | 12.45 ± 0.17a |

| Sunflower oil-in-water emulsion | ||||||||

| Control | 13.50 ± 1.12a | 5.01 ± 0.29b | 230.96 ± 5.38d | 27.06 ± 0.20b | 369.03 ± 15.67b | 417.11 ± 18.66ab | – | – |

| Phycocyanin (0.02%, w/w) | 10.89 ± 0.08b | 2.50 ± 0.40b | 258.47 ± 8.06cd | 26.10 ± 0.17b | 382.73 ± 12.13b | 451.82 ± 0.56ab | 1.13 ± 0.02c | 1.15 ± 0.04c |

| Phycocyanin (0.04%, w/w) | 10.50 ± 0.21b | 10.00 ± 0.10a | 279.05 ± 3.22c | 34.52 ± 4.38a | 286.93 ± 36.65d | 425.08 ± 58.13ab | 0.81 ± 0.19c | 1.30 ± 0.01bc |

| Phycocyanin (0.06%, w/w) | 9.00 ± 1.56b | 4.50 ± 0.77b | 414.93 ± 19.72a | 22.42 ± 2.10bc | 441.26 ± 51.49a | 637.46 ± 32.71c | 2.32 ± 0.02a | 2.45 ± 0.01a |

| Phycocyanin (0.08%, w/w) | 7.31 ± 0.11c | 10.12 ± 0.41a | 384.23 ± 23.34b | 16.88 ± 3.67c | 319.29 ± 18.85c | 483.19 ± 43.11bc | 1.67 ± 0.21b | 1.88 ± 0.43b |

| Sunflower oil with lecithin | ||||||||

| Control | 77.92 ± 5.92a | 15.50 ± 0.91a | 375.83 ± 30.91e | 45.00 ± 4.12a | 602.09 ± 17.19d | 684.21 ± 63.02d | – | – |

| Phycocyanin (0.02%, w/w) | 69.10 ± 3.67b | 11.05 ± 7.07b | 435.18 ± 33.70d | 41.47 ± 1.77b | 612.63 ± 9.42d | 598.83 ± 27.00c | 4.17 ± 0.17b | 9.13 ± 0.41c |

| Phycocyanin (0.04%, w/w) | 66.51 ± 7.21b | 9.52 ± 0.30b | 795.28 ± 41.06c | 32.25 ± 0.94bc | 765.19 ± 21.17c | 1119.06 ± 74.73b | 4.96 ± 0.80b | 8.36 ± 0.07c |

| Phycocyanin (0.06%, w/w) | 51.56 ± 9.10c | 5.25 ± 0.19c | 839.34 ± 19.05b | 27.87 ± 0.13c | 895.19 ± 20.04b | 1104.62 ± 28.87b | 10.18 ± 0.31a | 22.90 ± 0.13b |

| Phycocyanin (0.08%, w/w) | 25.36 ± 2.60d | 5.54 ± 0.54c | 948.91 ± 11.25a | 17.62 ± 0.34d | 1340.82 ± 27.20a | 1348.11 ± 45.52a | 11.11 ± 0.14a | 28.90 ± 0.28a |

In each column and in each section, means with different superscript lowercase letters are significantly different (P < 0.05). nf: pseudo-first order rate constant of lipid hydroperoxide formation, nd: pseudo-second order rate constant of lipid hydroperoxide decomposition, Tmax: the time when the rate of lipid hydroperoxide production reaches its maximum value, Wn: propagation oxidizability, PP: propagation period, EP: end time of propagation period, If: inhibitory effect of phycocyanin against lipid hydroperoxide production, and Id: inhibitory effect of phycocyanin against lipid hydroperoxide decomposition.

Mean ± SD (n = 3).

The PP values of sunflower oil samples containing combination of lecithin and phycocyanin were higher than those containing phycocyanin alone. The PP value of the sunflower oil sample containing a combination of lecithin and 0.08% phycocyanin was 2.2 times higher than that of the control sample, while the increase in IP length compared to the control was 3.1-fold. This observation suggests that a significant portion of the antioxidant molecules remained unutilized during the initiation phase at higher phycocyanin concentrations. Essentially, increasing the concentration of phycocyanin primarily shifts the consumption of these molecules from the IP to the PP. While antioxidant activity during the PP offers limited practical benefit, elucidating the pathways and events occurring in this phase could inform the development of strategies to divert antioxidant consumption towards the more crucial initiation phase.

The Tmax value shows the time when ROOH production rate reaches its maximum value (Farhoosh, 2021a). The Tmax value of sunflower and sunflower oil-in-water emulsion samples containing phycocyanin was substantially higher than that of the control sample (P < 0.05) (Table 2). While phycocyanin and lecithin were incorporated into the sunflower oil sample, the Tmax values of these samples were considerably higher than that of the sunflower oil sample without lecithin. The Wn value indicates propagation oxidizability (Farhoosh, 2021b; Toorani et al., 2020). The higher Wn value shows a higher sensitivity to peroxidation. Phycocyanin significantly reduced the Wn values of sunflower oil, sunflower oil-in-water emulsion, and sunflower oil containing lecithin compared to the control sample. Therefore, some phycocyanin molecules were active during the propagation phase.

Changes in water content and reverse micelles size of sunflower oil samples are presented in Table 3. In all sunflower oil samples, the size of reverse micelles and water content were increased during IP. As the oxidation process progresses, an accumulation of oxidation products (such as hydroperoxides) and their byproducts (like water) is observed in the reverse micelles structure. This accumulation leads to a corresponding increase in the size of the reverse micelles during the IP (Budilarto and Kamal-Eldin, 2015). At the end of IP, the size of reverse micelles reached a maximum value. After the IP point, the reverse micelles became destabilized and collapsed, resulting in a reduction in their size (Laguerre et al., 2015; Shim and Lee, 2011). For all samples, increasing water content caused a continuous rise in reverse micelle size until reaching a stopping point at the end of the initiation phase (Table 3). During the IP, the reverse micelles size and water content of sunflower oil samples containing lecithin were significantly higher than those without lecithin. This can be due to the capacity of lecithin to reduce the interfacial tension. Overall, lecithin addition led to an increase in all kinetic parameters, as shown in Table 1. This increase in the kinetic parameters can be related to the enhancement in the size of reverse micelles by lecithin, which can enhance the acceptance capacity of ROOHs in reverse micelles structures. Therefore, the effective collisions between phycocyanin and ROOHs can be increased with lecithin.

Table 3.

Reverse micelles size and water content of sunflower oil samples with phycocyanin in the presence and absence of lecithin.

| Sample | Reverse micelles size ( × 10−2) (nm) |

Water content (μg g−1) |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BIO | BIP | IP | AIP | PP | BIO | IP | PP | |

| Sunflower oil | ||||||||

| Control | 0.90 ± 0.03aa | 5.45 ± 0.01b | 9.87 ± 1.12d | 1.63 ± 0.51c | 12.91 ± 0.62d | 92.33 ± 1.95b | 110.20 ± 1.74e | 182.00 ± 4.30d |

| Phycocyanin (0.02%, w/w) | 0.21 ± 0.01c | 2.94 ± 0.37c | 12.82 ± 1.08c | 1.79 ± 0.85c | 13.10 ± 1.11d | 93.10 ± 1.50b | 145.43 ± 9.05d | 230.00 ± 3.22c |

| Phycocyanin (0.04%, w/w) | 0.83 ± 0.04b | 5.87 ± 1.50b | 13.15 ± 0.18c | 1.94 ± 0.06c | 16.50 ± 0.50c | 101.62 ± 0.61a | 170.05 ± 7.83c | 246.00 ± 6.41c |

| Phycocyanin (0.06%, w/w) | 0.18 ± 0.01c | 6.54 ± 0.41a | 17.30 ± 0.39b | 2.84 ± 0.19b | 21.95 ± 0.70b | 100.09 ± 1.71a | 245.72 ± 5.10b | 467.00 ± 5.23b |

| Phycocyanin (0.08%, w/w) | 0.56 ± 0.02b | 7.06 ± 0.06a | 20.13 ± 0.70a | 4.48 ± 0.34a | 25.13 ± 1.00a | 100.52 ± 1.38a | 300.94 ± 8.55a | 525.00 ± 2.06a |

| Sunflower oil with lecithin | ||||||||

| Phycocyanin (0.02%, w/w) | 1.67 ± 0.13a | 10.17 ± 0.90b | 20.19 ± 0.14c | 6.97 ± 0.05c | 24.70 ± 0.77c | 110.75 ± 3.28c | 128.11 ± 5.30d | 280.00 ± 11.79d |

| Phycocyanin (0.04%, w/w) | 0.80 ± 0.10b | 9.35 ± 0.75c | 27.05 ± 0.35b | 9.59 ± 0.51b | 33.73 ± 1.12b | 110.11± 2.06c | 161.22 ± 8.06c | 523.88 ± 5.10c |

| Phycocyanin (0.06%, w/w) | 1.87 ± 0.01a | 12.10 ± 0.30a | 29.87 ± 1.60a | 11.36 ± 0.91a | 36.50 ± 1.56b | 113.21 ± 4.17b | 235.61 ± 1.72b | 640.40 ± 6.31b |

| Phycocyanin (0.08%, w/w) | 1.61 ± 0.04a | 12.55 ± 0.21a | 30.14 ± 0.45a | 11.10 ± 0.72a | 49.00 ± 1.20a | 117.92 ± 9.33a | 432.23 ± 6.65a | 715.07 ± 1.00a |

In each column and for each sample, means with different superscript lowercase letters are significantly different (P < 0.05). BIO: at the beginning of the oxidation (T = 0 h), BIP: before the induction period (24 h before induction period), IP: at the induction period (Table 1), AIP: after the induction period (24 h after the induction period), and PP: at the propagation phase (at the time of Tmax (the time when the rate of lipid hydroperoxide production reaches its maximum value, Table 2)).

Mean ± SD (n = 3).

The water content of sunflower oil samples containing phycocyanin was significantly higher than that of the control sample. This may be attributed to the involvement of a phycocyanin in side reactions of the chain initiation (reaction 11, Fig. 1), which produce water. These water molecules strongly interact with the hydrophilic groups of lecithin, resulting in a reduction in interfacial tension (Toorani and Golmakani, 2021). This phenomenon likely accelerates reverse micelle formation by creating initial cores from the water produced. Consequently, the increased number of microreactors enhances the accessibility of existing antioxidants to the interface, where they can scavenge free radicals more effectively.

Fig. 3S reveals a positive correlation between water production during initiation and the F factor, suggesting that the hydrogen donation mechanism of antioxidants is enhanced by increasing the water content. Notably, while both water and ROOH production increase uniformly throughout oxidation, water molecules likely migrate faster towards the micelle core compared to ROOHs reaching the interface. This difference can be attributed to the smaller size of water molecules and the potentially stronger driving force of these molecules. These events may lead to a rapid expansion of the micelle core, surpassing the capacity of existing surfactants and prompting the generation of ROOHs to maintain interfacial coverage. At the beginning of the experiment, the interfacial tension values of sunflower oil, sunflower oil with lecithin, and phycocyanin (0.02%, w/w) with lecithin samples were 17.40 ± 1.12, 15.24 ± 0.68, and 15.63 ± 0.45 mN/m, respectively. At the IP point, the interfacial tension values of sunflower oil, sunflower oil with lecithin, and phycocyanin (0.02%, w/w) with lecithin samples were 8.71 ± 0.57, 7.16 ± 0.55, and 6.39 ± 0.15 mN/m, respectively. Therefore, a significant reduction in the interfacial tension of all sunflower oil samples was found at the IP point. This reduction in the interfacial tension can be related to the increase in the concentration of surface active ROOH at the IP point (Mansouri et al., 2020). After the IP point, the interfacial tension values of sunflower oil, sunflower oil with lecithin, and phycocyanin (0.02%, w/w) with lecithin samples were 8.03 ± 0.29, 6.39 ± 0.15, and 5.11 ± 0.15 mN/m, respectively. Accordingly, a further reduction in the interfacial tension of all sunflower oil samples was found after the IP point. This result can be related to the generation of more ROOH molecules and surface-active secondary oxidation products after IP point (Mansouri et al., 2020).

Sunflower oil with antioxidants showed lower interfacial tension, suggesting better dispersion and effectiveness. Lecithin played a key role in reducing interfacial tension and potentially increasing the accessibility of phycocyanin to the oil-water interface of reverse micelles, the primary site of oxidation. Lecithin might also form complexes with antioxidants and slightly enhance their solubility in sunflower oil. Phycocyanin and lecithin together had a stronger antioxidant effect than either alone. This aligns with previous research on the ability of lecithin to improve the antioxidant efficiency of gallic acid and methyl gallate in sunflower oil (Mansouri et al., 2020).

3.3. Mechanism of action of phycocyanin

A non-linear relationship was found between parameter F and phycocyanin concentration [AH] in sunflower oil, sunflower oil with lecithin, and sunflower oil-in-water emulsion samples (Fig. 2a). This nonlinear relationship shows a mismatch between phycocyanin's hydrogen donation mechanism and sunflower oil's ROOH production. This indicates that phycocyanin does not only take part in the main termination reaction ((reaction 7 (Fig. 1)). Phycocyanin might be involved in the initiation chain reactions (reactions 11 and/or 12 (Fig. 1)) (Keramat and Golmakani, 2024).

Analysis of the data in Fig. 2b revealed non-linear relationships between ORR and phycocyanin concentration in sunflower oil as well as sunflower oil with lecithin and sunflower oil-in-water emulsion samples. This result indicates that the phycocyanin radical formed after hydrogen donation deviates from the standard pathway and participates in beneficial reactions like propagation chain termination (A• + ROO• → A-OOR) (Toorani et al., 2024).

The participation of phycocyanin in reactions 11 and 12 was investigated by Eq. (20) (Toorani et al., 2024). The linear relationship between the rAH value (average rate of phycocyanin consumption) and phycocyanin concentration observed in Fig. 2c (at n = 1) indicates phycocyanin involvement in one of the initiation chain side reactions, i.e., reactions 11 or 12. Phycocyanin can participate in reaction 11 when a significant amount of unsaturated ROOHs are present in the lipid system. Sunflower oil contains significant amounts of linoleic acid that can generate reactive free radicals (Mansouri et al., 2020). This finding suggests that reaction 11 is the primary mechanism, where phycocyanin reacts with ROOHs to generate free radicals (A•) and water.

Besides, the lower keff value (rate constant of phycocyanin consumption in reaction 11) of sunflower oil samples containing a combination of phycocyanin and lecithin than those samples containing phycocyanin alone confirms this claim since reaction 11 is the reaction of phycocyanin molecules with O2 (AH + O2 → A• + HOO•), which is not expected to be altered by incorporating lecithin in sunflower oil (Toorani et al., 2024).

The keff and Wi/f values (extent of phycocyanin involvement in reaction 11) of sunflower oil samples containing a combination of phycocyanin and lecithin were significantly lower than those of samples containing phycocyanin alone (Table 1). This indicates that lecithin can reduce the rate constant and extent of participation of phycocyanin molecules in reaction 11. Reaction 11 (ROOH + AH → RO● + A● + H2O) generates a highly reactive alkoxyl radical, which can involve in a beta-scission reaction or abstract hydrogen from fatty acids, ultimately propagating the oxidation chain reaction (Shahidi, 2005). Sunflower oil contains a high amount of linoleic acid. The presence of bis-allylic carbons in these fatty acids makes them susceptible to degradation into peroxyl radicals (Shahidi, 2005; Shahidi and Zhong, 2010). These radicals exhibit a strong affinity for migrating toward reverse micelles, structures known to be active oxidation sites. Lecithin, as a surfactant, can enhance the number and size of these reverse micelles. This increase in the number and size of reverse micelles can improve the interaction between phycocyanin and peroxyl radicals (Toorani and Golmakani, 2021). Accordingly, in the presence of lecithin, the number of phycocyanin molecules participating in the main reaction of chain termination (reaction 7, Fig. 1) is increased, while the number of phycocyanin molecules involved in reaction 11 is decreased. This suggests that lecithin, while improving the formation of reaction sites, might also influence the specific interactions between antioxidant and reactive species, potentially leading to a more favorable antioxidant environment within the system. In other words, the addition of lecithin not only helps to control the oxidation process but also enhances the hydrogen donation mechanism of phycocyanin by reducing its involvement in reaction 11. By reducing participation in reaction 11, lecithin not only improves the oxidation process but also enhances the phycocyanin hydrogen-donating mechanism.

The keff value of the sunflower oil-in-water emulsion sample was significantly higher than that of sunflower oil. This could be related to the fact that sunflower oil has a higher viscosity than sunflower oil-in-water emulsion, which reduces the ability of phycocyanin to react with ROOH molecules. According to Fig. 3, nonlinear correlation between WAH value (pseudo-zero order rate constant at the initiation stage) and phycocyanin concentration at n = −0.5 and n = −1 was observed in all samples. Therefore, phycocyanin radicals are participated in more than one chain propagation reaction (−7, 10, and 14).

4. Conclusion

In this study, the antioxidant capacity of phycocyanin in sunflower oil and sunflower oil-in-water emulsion during the initiation and propagation phases was investigated. Phycocyanin significantly enhanced the AA value at a concentration of 0.08% (w/w). The antioxidant activity of phycocyanin in the emulsion was higher than that of the bulk oil. The presence of phycocyanin significantly extended the PP value compared to the control sample. During the propagation phase, phycocyanin was active and showed antioxidant activity. Incorporating lecithin into sunflower oil significantly enhanced the antioxidant potency and interfacial activity of phycocyanin. The inhibitory mechanism of phycocyanin improved in the presence of lecithin. The addition of lecithin to sunflower oil significantly altered the hydrogen donation mechanism of phycocyanin, resulting in increased IP, F, and AA values, while reducing ORR and WAH values. Measuring the water produced as a consequence of oxidation showed that the water content of the samples containing high phycocyanin concentration rose noticeably as oxidation proceeded. Lecithin demonstrably decreased the rate and extent of phycocyanin involvement in side reactions during the initiation phase. This effect is likely due to the ability of lecithin to modify and organize the oxidation micro-reactors as well as facilitating more productive interactions between phycocyanin molecules and free radical. Consequently, the improved organization of these microenvironments changed the inhibitory pathways of phycocyanin, effectively preventing its radical participation in detrimental chain reactions. Overall, these findings support the exploration of lecithin alongside thesurface active antioxidants such as phycocyanin. This combination holds promise for development of a new generation of antioxidants with significant implications in edible oil industry. Future studies should prioritize the development of strategies to optimize the delivery of natural antioxidant molecules to these interfaces. This optimized delivery has the potential to fully exploit the inherent inhibitory power of these antioxidants, leading to more effective inhibition of peroxidation in lipid systems.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Elham Ehsandoost: Investigation, Data curation, Formal analysis, Software, Methodology, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Validation. Mohammad Hadi Eskandari: Supervision, Project administration, Funding acquisition, Writing – review & editing. Malihe Keramat: Conceptualization, Investigation, Data curation, Writing – review & editing, Formal analysis. Mohammad-Taghi Golmakani: Supervision, Funding acquisition, Project administration, Conceptualization, Writing – review & editing.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgments

This research project was financially supported by Shiraz University.

Handling Editor: Professor Aiqian Ye

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.crfs.2025.100981.

Contributor Information

Mohammad Hadi Eskandari, Email: eskandar@shirazu.ac.ir.

Mohammad-Taghi Golmakani, Email: golmakani@shirazu.ac.ir.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following is the Supplementary data to this article.

Data availability

Data will be made available on request.

References

- Alavi N., Golmakani M.-T., Hosseini S.M.H., Niakousari M., Moosavi-Nasab M. Enhancing phycocyanin solubility via complexation with fucoidan or κ-carrageenan and improving phycocyanin color stability by encapsulation in alginate-pregelatinized corn starch composite gel beads. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2023;242 doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2023.124762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asnaashari M., Farhoosh R., Sharif A. Antioxidant activity of gallic acid and methyl gallate in triacylglycerols of Kilka fish oil and its oil-in-water emulsion. Food Chem. 2014;159:439–444. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2014.03.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ASTM . 203-16. Standard Test Method for Water Using Volumetric. Karl Fischer Titration. ASTM International; West Conshohocken, PA, USA: 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Baydır A.T., Soltanbeigi A., Maral H. The antioxidant effect of rosemary on the oxidation stability of refıned sunflower oil. Avrupa Bilim ve Teknoloji Dergisi. 2023;(50):60–65. [Google Scholar]

- Budilarto E.S., Kamal‐Eldin A. The supramolecular chemistry of lipid oxidation and antioxidation in bulk oils. Eur. J. Lipid Sci. Technol. 2015;117(8):1095–1137. doi: 10.1002/ejlt.201400200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cardenia V., Waraho T., Rodriguez-Estrada M.T., Julian McClements D., Decker E.A. Antioxidant and prooxidant activity behavior of phospholipids in stripped soybean oil-in-water emulsions. J. Am. Oil Chem. Soc. 2011;88:1409–1416. [Google Scholar]

- Denisov E.T., Khudyakov I. Mechanisms of action and reactivities of the free radicals of inhibitors. Chem. Rev. 1987;87(6):1313–1357. [Google Scholar]

- Di Mattia C.D., Sacchetti G., Mastrocola D., Sarker D.K., Pittia P. Surface properties of phenolic compounds and their influence on the dispersion degree and oxidative stability of olive oil O/W emulsions. Food Hydrocolloids. 2010;24(6–7):652–658. [Google Scholar]

- Farhoosh R. Antioxidant activity and mechanism of action of butein in linoleic acid. Food Chem. 2005;93(4):633–639. [Google Scholar]

- Farhoosh R. Initiation and propagation kinetics of inhibited lipid peroxidation. Sci. Rep. 2021;11(1):6864. doi: 10.1038/s41598-021-86341-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farhoosh R. New insights into the kinetic and thermodynamic evaluations of lipid peroxidation. Food Chem. 2021 doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2021.131659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernandes R., Campos J., Serra M., Fidalgo J., Almeida H., Casas A.…Barros A.I. Exploring the benefits of phycocyanin: from Spirulina cultivation to its widespread applications. Pharmaceuticals. 2023;16(4):592. doi: 10.3390/ph16040592. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gabr G.A., El-Sayed S.M., Hikal M.S. Antioxidant activities of phycocyanin: a bioactive compound from Spirulina platensis. Journal of Pharmaceutical Research International. 2020;32(2):73–85. [Google Scholar]

- Keramat M., Ehsandoost E., Golmakani M.-T. Recent trends in improving the oxidative stability of oil-based food products by inhibiting oxidation at the interfacial region. Foods. 2023;12(6):1191. doi: 10.3390/foods12061191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keramat M., Golmakani M.T. Antioxidant potency and inhibitory mechanism of curcumin and its derivatives in oleogel and emulgel produced by linseed oil. Food Chem. 2024;445 doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2024.138754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keramat M., Golmakani M.-T., Niakousari M. Effect of polyglycerol polyricinoleate on the inhibitory mechanism of sesamol during bulk oil oxidation. Sci. Rep. 2022;12(1) doi: 10.1038/s41598-022-16201-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laguerre M., Bayrasy C., Panya A., Weiss J., McClements D.J., Lecomte J.…Villeneuve P. What makes good antioxidants in lipid-based systems? The next theories beyond the polar paradox. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2015;55(2):183–201. doi: 10.1080/10408398.2011.650335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lehtinen O.-P., Nugroho R.W.N., Lehtimaa T., Vierros S., Hiekkataipale P., Ruokolainen J.…Österberg M. Effect of temperature, water content and free fatty acid on reverse micelle formation of phospholipids in vegetable oil. Colloids Surf. B Biointerfaces. 2017;160:355–363. doi: 10.1016/j.colsurfb.2017.09.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mansouri H., Farhoosh R., Rezaie M. Interfacial performance of gallic acid and methyl gallate accompanied by lecithin in inhibiting bulk phase oil peroxidation. Food Chem. 2020;328 doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2020.127128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martelli G., Folli C., Visai L., Daglia M., Ferrari D. Thermal stability improvement of blue colorant C-Phycocyanin from Spirulina platensis for food industry applications. Process Biochem. 2014;49(1):154–159. [Google Scholar]

- Ostertag F., Weiss J., McClements D.J. Low-energy formation of edible nanoemulsions: factors influencing droplet size produced by emulsion phase inversion. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2012;388(1):95–102. doi: 10.1016/j.jcis.2012.07.089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patel A., Mishra S., Ghosh P. Phormidium and Spirulina Spp. 2006. Antioxidant potential of C-phycocyanin isolated from cyanobacterial species Lyngbya. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Renugadevi K., Nachiyar C.V., Sowmiya P., Sunkar S. Antioxidant activity of phycocyanin pigment extracted from marine filamentous cyanobacteria Geitlerinema sp TRV57. Biocatal. Agric. Biotechnol. 2018;16:237–242. [Google Scholar]

- Szuhaj B.F. In World Soybean Research Conference II. CRC Press; 2019. Food and industrial uses of soybean lecithin; pp. 681–691. [Google Scholar]

- Shahidi F. vol. 5. John Wiley & Sons; 2005. (Bailey's Industrial Oil and Fat Products, Edible Oil and Fat Products: Processing Technologies). [Google Scholar]

- Shahidi F., Zhong Y. Lipid oxidation and improving the oxidative stability. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2010;39(11):4067–4079. doi: 10.1039/b922183m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shantha N.C., Decker E.A. Rapid, sensitive, iron-based spectrophotometric methods for determination of peroxide values of food lipids. J. AOAC Int. 1994;77(2):421–424. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shim S.D., Lee S.J. Shelf‐life prediction of perilla oil by considering the induction period of lipid oxidation. Eur. J. Lipid Sci. Technol. 2011;113(7):904–909. [Google Scholar]

- Toorani M.R., Farhoosh R., Golmakani M., Sharif A. Antioxidant activity and mechanism of action of sesamol in triacylglycerols and fatty acid methyl esters of sesame, olive, and canola oils. Lwt. 2019;103:271–278. [Google Scholar]

- Toorani M.R., Golmakani M.-T. Investigating relationship between water production and interfacial activity of γ-oryzanol, ethyl ferulate, and ferulic acid during peroxidation of bulk oil. Sci. Rep. 2021;11(1) doi: 10.1038/s41598-021-96439-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toorani M.R., Golmakani M.-T., Gahruie H.H. Antioxidant activity and inhibitory mechanism of γ-oryzanol as influenced by the unsaturation degree of lipid systems. Lwt. 2020;133 [Google Scholar]

- Toorani M.R., Jokar M., Nateghi L., Golmakani M.-T. Antioxidant functions of quercetin in supramolecular oxidation of bulk oil: role of polyglycerol polyricinoleate in the mass transfer network. Lwt. 2024;195 doi: 10.1111/1750-3841.16905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu H.-L., Wang G.-H., Xiang W.-Z., Li T., He H. Stability and antioxidant activity of food-grade phycocyanin isolated from Spirulina platensis. Int. J. Food Prop. 2016;19(10):2349–2362. [Google Scholar]

- Xu N., Shanbhag A.G., Li B., Angkuratipakorn T., Decker E.A. Impact of phospholipid–tocopherol combinations and enzyme-modified lecithin on the oxidative stability of bulk oil. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2019;67(28):7954–7960. doi: 10.1021/acs.jafc.9b02520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao S., Pu W., Li Y., Jiang Q., Yuan C., Varfolomeev M.A., Xu C. Oxidation behavior and kinetics of shale oil under different oxygen concentrations. Fuel. 2024;361 [Google Scholar]

- Zhu Z., Zhao C., Yi J., Liu N., Cao Y., Decker E.A., McClements D.J. Impact of interfacial composition on lipid and protein co-oxidation in oil-in-water emulsions containing mixed emulisifers. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2018;66(17):4458–4468. doi: 10.1021/acs.jafc.8b00590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Data will be made available on request.