Abstract

Purpose

SBRT demonstrated to increase survival in oligometastatic patients. Nevertheless, little is known regarding the natural history of oligometastatic disease (OMD) and how SBRT may impact the transition to the polymetastatic disease (PMD).

Methods

97 liver metastases in 61 oligometastatic patients were treated with SBRT. Twenty patients (33%) had synchronous oligometastases, 41 (67%) presented with metachronous oligometastases. Median number of treated metastases was 2 (range 1–5).

Results

Median follow-up was 24 months. Median tPMC was 11 months (range 4–17 months). Median overall survival (OS) was 23 months (range 16–29 months). Cancer-specific survival predictive factors were having further OMD after SBRT (21 months versus 15 months; p = 0.00), and local control of treated metastases (27 months versus 18 months; p = 0.031). Median PFS was 7 months (range 4–12 months). Patients with 1 metastasis had longer median PFS as compared to those with 2–3 and 4–5 metastases (14.7 months versus 5.3 months versus 6.5 months; p = 0.041). At the last follow-up, 50/61 patients (82%) progressed, 16 of which (26.6%) again as oligometastatic and 34 (56%) as polymetastatic.

Conclusion

In the setting of oligometastatic disease, SBRT is able to delay the transition to the PMD. A proportion of patients relapse as oligometastatic and can be eventually evaluated for a further SBRT course. Interestingly, those patients retain a survival benefit as compared to those who had PMD. Further studies are needed to explore the role of SBRT in OMD and to identify treatment strategies able to maintain the oligometastatic state.

Keywords: Stereotactic body radiotherapy, SBRT, Liver metastases, Oligometastatic disease

Introduction

The liver is one of the most common sites of metastases from solid tumors, and local approaches represent a viable therapeutic option in the case of a limited number of lesions (Abdalla et al. 2004). This last clinical scenario, also known as oligometastatic disease (OMD), was firstly formulated by Hellman and Weichselbaum to delineate an intermediate step in the natural history of tumors characterized by a limited number of metastases (≤ 5) where local treatment may favorably impact on clinical outcomes (Hellman and Weichselbaum 1995). In the case of the liver, several therapeutic strategies have shown remarkable results both in terms of tolerance and efficacy (Meijerink et al. 2018; Petrelli et al. 2018; Mazzola et al. 2018a; Alongi et al. 2012). Among these, stereotactic body radiation therapy (SBRT) proved to be an attractive option for unresectable disease or for patients medically unfit for a surgical approach. Several phase II studies reported a survival advantage provided by SBRT in oligometastatic patients (Robin et al. 2018; Rusthoven et al. 2009; Hoyer et al. 2006; Clerici et al. 2019).

The ground-breaking results of the SABR-COMET study (Palma et al. 2019), pointed out the need to better understand the natural history of oligometastatic tumors, in particular, the biological mechanisms that lead to the polymetastatic disease (PMD) development, defined by the presence of ≥ 6 lesions, thus no longer suitable for local ablative treatments.

Some authors have hypothesized that the transition to the polymetastatic state is preceded by the so-called sequential oligometastatic disease (SOMD), a further oligometastatic progression for whom second SBRT courses are still feasible (Milano et al. 2012, 2009; Adam et al. 2003). In this setting, the goal of proposing further ablative treatment courses is to cure the tumor before the progression to the PMD takes place.

This is also confirmed by a recent study by Greco et al. (2019), who observed that based on pre-treatment metabolic imaging, the OMD can be categorized in three subgroups, allowing the identification of those patients for whom the use of further SBRT courses leads to better clinical outcomes. The findings of this study may lay the foundations for overcoming the OMD number-based concept, in favor of a biological model to apply for the decision-making strategy. Nevertheless, to date, this issue remains under investigation.

The aim of the present study is to evaluate the role of liver SBRT in delaying the transition from the oligo- to the polymetastatic disease, and how this has an effect on survival.

Materials and methods

Inclusion criteria for the present retrospective analysis were: (1) OMD liver patients underwent SBRT; (2) performance status ECOG (Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group Criteria) ≤ 2; (3) no other active sites of disease or distant metastases outside the liver; (4) patients ineligible for surgery or radiofrequency ablation because of advanced age, comorbidities or procedure refusal; (5) adequate liver function defined as total bilirubin < 3 mg/dL, albumin > 2.5 g/dL, normal prothrombin time (PT)/partial thromboplastin time (PTT) unless on anticoagulants, and serum levels of aspartate aminotransferase (AST) and alanine aminotransferase (ALT) less than three times the upper limit of normality.

Pre-treatment evaluation included clinical examination, total blood count and liver function examination, total body computed tomography (CT) scan with contrast medium, Magnetic resonance Imaging and/or 18-fluorodeoxyglucose-positron emission tomography (FDG-PET/CT). The current study was carried out according to the Declaration of Helsinki (1964) and was approved by the Internal Review Board (Department of Advanced Radiation Oncology, IRCCS Sacro Cuore Don Calabria Hospital, Negrar—Verona). Written informed consent was obtained by all patients.

Treatment characteristics

A planning CT scan with contrast medium was acquired. Patients were positioned supine with arms raised above the head and were immobilized by means of a thermoplastic body mask including a Styrofoam block for abdominal compression to minimize internal organ motion. Contrast-free and three-phase contrast-enhanced were acquired in free-breathing mode at 3 mm slice thickness. Planning CT images were co-registered with three-phase contrast-enhanced CT to identify the gross tumor volume (GTV). The clinical target volume was defined as equal to the GTV. The planning target volume (PTV) was generated from the GTV by adding a 7–10 mm margin in the craniocaudal axis and 4–6 mm in the anteroposterior and lateral axes (Mazzola et al. 2018a; Scorsetti et al. 2013). The median prescribed dose was 48 Gy (range 30–75 Gy) delivered in a median of six fractions (range 3–10) on consecutive working days. The normal liver dose constraint was set at more than 700 cm3 of normal liver receiving less than 15 Gy. Image-guided SBRT was performed by means of a megavoltage Cone-beam CT before each daily session to minimize set up uncertainties. All plans were performed by Rapid Arc, v. 10.0.28 (Varian Inc., Palo Alto, CA) volumetric modulated arc therapy.

Follow-up and response assessment

The first follow-up was performed 6–8 weeks after SBRT with a contrast-enhanced CT scan. Afterward, follow-up was performed with a total body computed tomography (CT) scan with contrast medium every three months for the first 2 years after SBRT and every 6 months starting from the third year. MRI or 18-fluorodeoxyglucose-positron emission tomography (FDG-PET/CT) were performed in the case of suspected progressive disease on CT scan. Moreover, physical examination and basal blood chemistry analyses were performed 21 days after SBRT and then at each follow-up. After SBRT, when disease progression was observed during the follow-up period, patients were evaluated to receive: further local ablative therapy, systemic therapy or best supportive care based on physician’s choice. Tumor response was defined according to the Response Evaluation Criteria In Solid Tumors (RECIST) 1.1 (Eisenhauer et al. 2009), or PET Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors (PERCIST) (Pinker et al. 2017). Treatment-related adverse effects were assessed at each follow-up according to the Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (CTCAE) v 4.0.

Study end-points and statistics

The primary end-point was to estimate the time to PMD conversion (tPMC) after SBRT. Secondary end-points were overall survival (OS), cancer-specific survival (CSS) progression-free survival (PFS), SOMD rate and local progression-free survival (LPFS).

tPMC was defined as the time from the SBRT to the occurrence of > 5 new metastatic lesions. OS was defined as the time from the SBRT to death or last follow-up. PFS was defined as the time from the SBRT to local/distant progression or death. SOMD rate was defined as the occurrence of ≤ 5 new metastatic lesions after SBRT. LPFS was defined as the time to the occurrence of in-field or marginal disease regrowth or death. Moreover, in-field recurrence was defined as any recurrence occurred within the 95% isodose curve and marginal recurrence as any recurrence occurred within the 50% isodose curve.

Survivals were estimated using the Kaplan–Meier method. Prognostic factors such as age, sex, number of treated lesions, primary histology, lesion diameter, GTV size, PTV size, type of response were included in the statistical analysis. Univariate analysis was performed to determine significant prognostic factors using the log-rank test or the Cox method for continuous variables. The multivariate analysis was performed with the multiple logistic regression method and the log-rank test to identify predictive factors; we included in the analysis all the clinically relevant variables. Variables were included in the multivariate analysis according to the correlation at the univariate analysis (P ≤ 0.2). Statistical analysis was performed using the SPSS statistical software package version 22.0 (SPSS Inc, Chicago, IL). A p-value ≤ 0.05 indicated a significant association.

Results

Patients' and lesions' characteristics

The study population was represented by 97 liver oligometastases in 61 patients. The mean age was 70 years (range 38–89 years). Primary tumor histologies were colon-rectum (Pinker et al. 2017), breast (Clerici et al. 2019), pancreas (Robin et al. 2018), lung (Mazzola et al. 2018a), stomach (Mazzola et al. 2018a), biliary tract (Mazzola et al. 2018a), gynecological (Meijerink et al. 2018), other (Rusthoven et al. 2009). Oligometastases were synchronous in 20 patients (33%) and metachronous in 41 cases (67%). The median number of treated lesions was 2 (range 1–5). The median lesion diameter was 20 mm (range 5–50 mm). The median time to the oligometastatic disease after initial curative treatment was 19 months (range 4–217 months). Systemic treatment (ST) was administered before SBRT in 42 patients (69%), while 19 (31%) were treated with SBRT alone. Patient, tumor, and treatment characteristics are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Patients’ characteristics

| Characteristic | N (%) or median value (range) |

|---|---|

| Gender | |

| Male | 37 (60.4%) |

| Female | 24 (39.3%) |

| Age | 70 years (38–89) |

| Primary histology | |

| Colorectal | 18 (34%) |

| Lung | 5 (10.3%) |

| Breast | 10 (10.3%) |

| Upper GI | 15 (27.8%) |

| Gynaecological | 3 (5.2%) |

| Other | 8 (12.4%) |

| Type of metastases | |

| Synchronous | 20 (33%) |

| Metachronous | 41 (67%) |

| Primary in control at SBRT time | |

| Yes | 17 (27%) |

| No | 44 (63%) |

| Chemotherapy prior to SBRT | |

| Yes | 42 (68%) |

| No | 19 (32%) |

| Number of liver lesions | |

| 1 | 39 (64%) |

| 2 | 12 (19.5%) |

| 3 | 6 (10%) |

| 4 | 4 (6.5%) |

| Lesion diameter (mm) | 20 mm (5–50) |

| GTV (cc) | 10 cc (1–57) |

| PTV (cc) | 27 cc (5–140) |

| Dose per fraction (Gy) | 8 Gy (5–25) |

| Total dose (Gy) | 48 Gy (30–75) |

GI gastrointestinal, SBRT stereotactic body radiotherapy, GTV gross tumor volume, PTV planning treatment volume

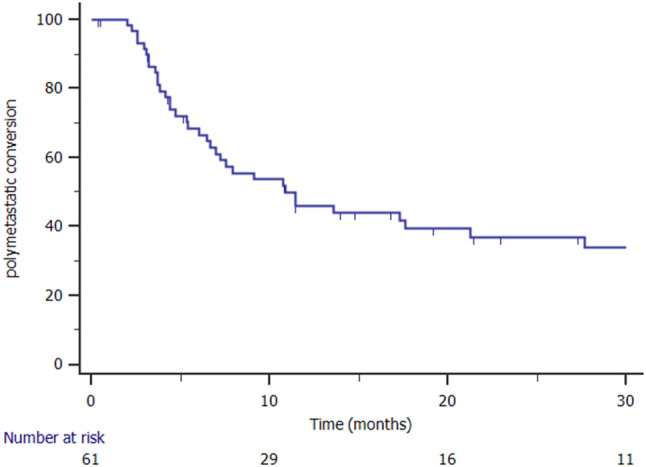

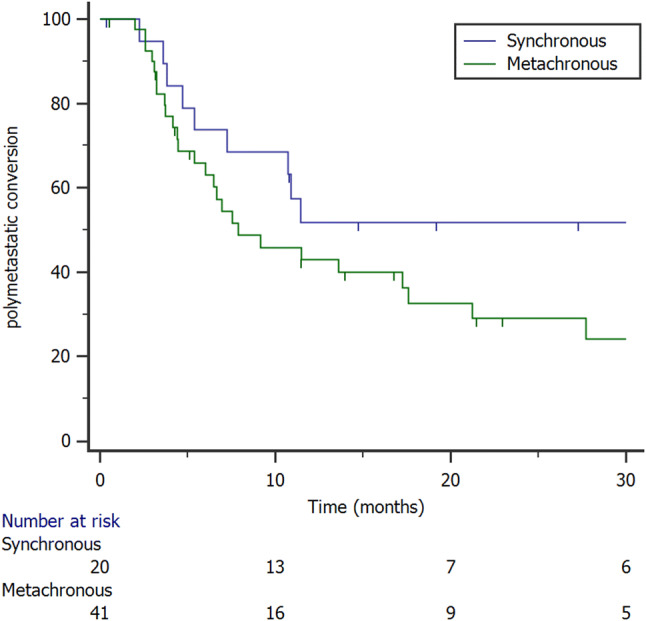

Time to polymetastatic disease conversion

The median tPMC was 11 months (range 4–17 months) and the 1- and 2-year tPMC were 46% and 36.9%, respectively (Fig. 1). At the univariate analysis, metachronous oligometastases were predictive for a longer tPMC (p = 0.05, Fig. 2), and ST before SBRT did not improve tPMC (median 11 months versus 9 months; p = 0.8). Univariate analysis results are reported in Table 2.

Fig. 1.

Kaplan Meier curve showing polymetastatic conversion

Fig. 2.

Kaplan Meier curve showing polymetastatic conversion stratified to metastases timing (synchronous versus metachronous)

Table 2.

Univariate analysis

| Factor | tPMC | CSS | LPFS | OS | PFS |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| p | p | p | p | p | |

| Primary site | 0.48 | 0.345 | 0.005 | 0.62 | 0.51 |

| Metachronous versus synchronous metastases | 0.050 | 0.008 | 0.596 | 0.005 | 0.055 |

| Primary tumor controlled at SBRT time | 0.696 | 0.349 | 0.918 | 0.76 | 0.94 |

| Chemotherapy prior to SBRT | 0.862 | 0.14 | 0.003 | 0.058 | 0.19 |

| Local control | 0.119 | 0.031 | – | 0.08 | 0.07 |

| Primary histology | 0.208 | 0.02 | 0.360 | 0.01 | 0.037 |

| Gender | 0.57 | 0.344 | 0.347 | 0.21 | 0.91 |

| Stage of primary at diagnosis | 0.28 | 0.146 | 0.268 | 0.095 | 0.15 |

| Type of progression (oligo vs polymetastatic) | 0.00 | 0.031 | 0.09 | 0.001 | – |

| Polymetastatic conversion | – | 0.00 | 0.039 | 0.00 | – |

| Number of treated metastases | 0.551 | 0.649 | – | 0.617 | 0.041 |

| Lesion diameter < 27 mm | 0.46 | 0.034 | 0.018 | 0.057 | 0.68 |

| PTV < 44 cc | 0.5 | 0.23 | 0.007 | 0.14 | 0.43 |

Bold values indicate significant correlations

SBRT stereotactic body radiotherapy, PTV planning treatment volume

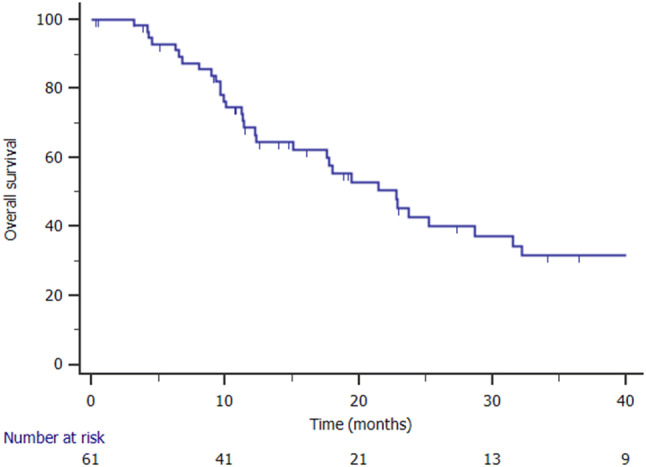

Survival and local control

The median OS was 23 months (range 16–29 months). The 1- and 2-year OS were 68.6% and 42.7%, respectively (Fig. 3). At the univariate analysis factors associated with OS were: having metachronous oligometastases (p = 0.005), SOMD (p = 0.001), and PMC (p = 0.00). The median CSS was 23 months (range 15–30 months). At the univariate analysis, factors associated with longer CSS were: local control of treated metastases (median 27 months versus 18 months; p = 0.031, Fig. 4), and having a SOMD after primary SBRT (median 21 months versus 15 months; p = 0.00).

Fig. 3.

Kaplan Meier curve showing overall survival

Fig. 4.

Kaplan Meier curve showing cancer-specific survival stratified to local control of treated lesions

The median LPFS was not reached and the 1- and 2-year LPFS were 72.6% and 61.2%, respectively. At the last follow-up, 27 (27.8%) out of 97 lesions in 14 patients locally progressed. The predictive factor of LPFS at the univariate analysis was ST before SBRT (p = 0.03). Moreover, at the ROC curve analysis, lesion diameter < 27 mm and PTV volume < 44 cc were predictive of improved LPFS (p = 0.018 and p = 0.007, respectively).

Disease progression, sequential oligometastatic disease, and relapse treatment

Median PFS was 7 months (range 4–12 months). Patients with 1 metastasis had longer median PFS as compared to those with 2–3 and 4–5 metastases (14.7 months versus 5.3 months versus 6.5 months; p = 0.041). At the last follow-up 11 patients (18%) were free from disease, 16 patients (26%) had SOMD and 34 (56%) PMD. Patients who developed SOMD were evaluated for a new SBRT course (3 cases) or ST (13 cases), while among patients with PMD 20 (32.7%) were submitted to best supportive care due to poor clinical conditions or comorbidities, and 14 (23%) received further ST.

Multivariate analysis

At the multivariate analysis SOMD after SBRT was associated with improved OS (p = 0.014; HR 0.386, I.C. 0.181–0.824) and CSS (p = 0.003; HR 0.276, I.C. 0.120–0.637). A PTV lesion < 44 cc was predictive of better LPFS (p = 0.048; HR 0.293, I.C. 0.087–0.987). The results of multivariate analysis are reported in Table 3.

Table 3.

Multivariate analysis

| Factor | tPMC | CSS | LPFS | OS |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| P | p | p | p | |

| Primary site | ||||

| Metachronous or synchronous metastases | 0.147 (HR = 0.557; CI = 0.252–1.22) | |||

| Chemotherapy prior to SBRT | 0.109 (HR:2.65; CI = 0.803–8.75) | |||

| Primary controlled | 0.059 (HR:2.32; CI = 0.96–5.60) | |||

| Local control | 0.402 (HR = 0.735; CI = 0.359–1.75) | 0.59 (HR:0.772; CI = 0.338–0.637) | 0.414 (HR:0.724; CI = 0.332–1.58) | |

| Primary histology | ||||

| Gender | 0.161 (HR = 1.68; CI = 0.812–3.51) | 0.573 (HR:0.777; CI = 0.323–1.86) | 0.497 (HR:1.71;CI = 0.36–8.151) | 0.441 (HR:0.726; CI = 0.314–1.65) |

| Type of progression (oligo vs polymetastatic) | 0.003 (HR:0.276; CI = 0.120–0.637) | 0.014 (HR:0.386, CI = 0.181–0.824) | ||

| PTV < 44 cc | 0.048 (HR:0.293, CI = 0.087–0.987 |

tPMC time to polymetastatic conversion, CSS cancer-specific survival, LPFS local progression-free survival, OS overall survival

Discussion

Results of recent randomized trials on the use of SBRT in the oligometastatic disease are raising the interest in exploiting this last therapeutic approach in daily clinical practice. In a recent randomized phase II trial, SBRT administered before ST was able to significantly improve median survival from 28 to 41 months in patients affected by OMD from different solid tumors (Palma et al. 2019). The biological rationale of adding local ablative treatments to OMD relies on the finding that metastases have the potential to metastasize themselves through metastases neo-vasculature (Gundem et al. 2015). The spatial synergy between local and systemic treatments has several advantages. Systemic treatments are effective in controlling the microscopic disease, but this impact may be limited for the macroscopic disease; conversely, local treatments may provide very high local control rates for the macroscopic lesions, with no direct effects on the microscopic disease. Furthermore, SBRT may overcome the issue of the selection of drug-resistant clones induced by ST, given the ablative action to the entirety of the lesion (Arneth 2018; Iijima et al. 2018).

Interestingly, when metastases-directed therapy for OMD is administered as up-front therapeutic option instead of ST Real-Life data report a favorable impact on distant progression free-survival and systemic-treatment free-survival (Valentí et al. 2019; Mihai et al. 2017; Mazzola et al. 2018b; Nicosia et al. 2019; Triggiani et al. 2017; Franzese et al. 2019).

It remains field of translational research to explore: (1) the new concept of SOMD after SBRT, potentially amenable of new local ablative courses (Mazzola et al. 2018a; Greco et al. 2019; Osti et al. 2018), (2) how local therapy might influence the transition to a polymetastatic disease amenable to systemic therapies only.

To our knowledge, literature lacks to report specific data regarding these last oncologic outcomes in case of liver OMD patients. Thus, the present study is the first to report the role of liver SBRT in delaying the transition from the oligo- to the polymetastatic disease.

In the present series, ST was administered before SBRT in 42 patients (69%), while 19 (31%) were treated with SBRT alone. The median tPMC was 11 months. This survival end-point is still a novel finding and relates to the SBRT potential of keeping the disease in an OM state. Interestingly, SOMD occurred in 26% of patients and 18% are free from disease at the last follow-up. In the study of Greco et al. PMC occurred after a median time of 11 months, similar to the present series. Moreover, we reported metachronous oligometastatic patients having a better tPMC compared to synchronous ones. This finding is in agreement with a recent review of 17 paper assessing the outcomes of 869 patients treated with SBRT for lung oligometastases, detecting better OS rates in those patients with a disease-free interval ≥ 24 months, highlighting the hypothesis of a prognostic difference between synchronous and metachronous secondary lesions (Alongi et al. 2018).

In our experience, ST given before SBRT produced a significant advantage in terms of LC. Moreover, LC significantly related to better OS and CSS rates, and, notably, those patients who progressed after SBRT in a further oligometastatic disease kept a survival advantage compared to those who progressed in a poly-metastatic state. At the same time, we observed no impact of ST on delaying the conversion to the PMD state. This evidence may be influenced by the small sample size. Despite many trials are currently ongoing and investigating the optimal combination of SBRT with ST, it is hard to draw definitive conclusions regarding the real benefit of one treatment over the other one, thus focusing the need of a deeper understanding of the natural history of the oligo- and poly-metastatic disease (Al-Shafa et al. 2019).

In a study by Milano et al. (2009), patients affected by OMD were safely treated with multiple SBRT courses in case of further oligoprogression. This aggressive approach has led to a PFS improvement, as compared to patients treated with a single SBRT course. In our series, SOMD was predictive of better OS and CSS, underlying the importance to maintain the OM state to increase patient clinical outcomes.

In a retrospective multicenter study on 500 lung and liver colorectal metastases treated with SBRT, local progression negatively affected survival (Klement et al. 2019). Similarly, in the present series, OS and CSS were favorably influenced by local control. Nevertheless, the correlation was not confirmed by the multivariate analysis, while only the SOMD remains a predictive factor of survival. This finding naturally leads to the question: which are the best candidates to develop SOMD? There are actually limited available factors predicting this patient category. In a previous paper, three OMD categories were identified according to the disease volume and the PET signal (Greco et al. 2019). Category 1 was the less prone to develop PMD and was virtually the real “oligometastatic disease”, while category 3, even if presenting with apparent “low disease burden”, unavoidably evolved to PMD. Two main hypotheses regarding the origin and the natural history of OMD are currently under investigation; the first one is based on the theory of an origin from clones exhibiting an ab initio “oligo” or “poly” phenotype, while the second one postulates a reiterative mutational process where the OMD sequentially progress to the PMD (Campbell et al. 2010; Yachida et al. 2010; Klein 2013; Kim et al. 2009). Both hypotheses are plausible and supported yet by genomic studies.

Limitations of the present study are the retrospective nature and the primary tumor histology heterogeneity. Points of strength are the good selection of candidates and the limited number of metastatic sites. The knowledge of the oligometastatic disease is rapidly evolving, but a better understanding of the OMD molecular basis is needed to upstage the actual number-based concept and to personalize treatment indications.

Conclusion

SBRT is a useful tool in the multimodal management of oligometastatic disease. Its use might delay the transition to the polymetastatic disease and provide long remission time in some cases. Nevertheless, a proportion of patients seems not to clearly benefit from SBRT and rapidly develop a polymetastatic disease. Local control seems to relate to longer survival, therefore, is crucial to maximize the local effectiveness. The results of the present study highlight the need for large prospective trials aimed to identify clinical and biological factors useful for patient selection.

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical approval

This article does not contain any studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

Informed consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- Abdalla EK, Vauthey JN, Ellis LM et al (2004) Recurrence and outcomes following hepatic resection, radiofrequency ablation, and combined resection/ablation for colorectal liver metastases. Ann Surg 239(6):818–825 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adam R, Pascal G, Azoulay D, Tanaka K, Castaing D, Bismuth H (2003) Liver resection for colorectal metastases: the third hepatectomy. Ann Surg 238:871–883 (discussion: 83–84) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alongi F, Arcangeli S, Filippi AR, Ricardi U, Scorsetti M (2012) Review and uses of stereotactic body radiation therapy for oligometastases. Oncologist 17(8):1100–1107. 10.1634/theoncologist.2012-0092 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alongi F, Mazzola R, Figlia V, Guckenberger M (2018) Stereotactic body radiotherapy for lung oligometastases: literature review according to PICO criteria. Tumori 104(3):148–156. 10.1177/0300891618766820 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Al-Shafa F, Arifin AJ, Rodrigues GB, Palma DA, Louie AV (2019) A review of ongoing trials of stereotactic ablative radiotherapy for oligometastatic cancers: where will the evidence lead? Front Oncol 9:543. 10.3389/fonc.2019.00543 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arneth B (2018) Comparison of Burnet's clonal selection theory with tumor cell-clone development. Theranostics 8(12):3392–3399. 10.7150/thno.24083 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell PJ, Yachida S, Mudie LJ, Stephens PJ, Pleasance ED, Stebbings LA, Morsberger LA, Latimer C, McLaren S, Lin M-L, McBride DJ, Varela I, Nik-Zainal SA, Leroy C, Jia M, Menzies A, Butler AP, Teague JW, Griffin CA, Burton J, Swerdlow H, QuailMA SMR, Iacobuzio-Donahue C, Futreal PA (2010) Thepatterns and dynamics of genomic instability in metastatic pancreatic cancer. Nature 467:1109–1113. 10.1038/nature0946017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clerici E, Comito T, Franzese C, Di Brina L, Tozzi A, Iftode C, Navarria P, Mancosu P, Reggiori G, Tomatis S, Scorsetti M (2019) Role of stereotactic body radiation therapy in the treatment of liver metastases: clinical results and prognostic factors. Strahlenther Onkol. 10.1007/s00066-019-01524-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisenhauer E, Therasse P, Bogaerts J et al (2009) New response evaluation criteria in solid tumors: revised RECIST guideline (version 1.1). Eur J Cancer 45:228–247 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franzese C, Comito T, Toska E, Tozzi A, Clerici E, De Rose F, Franceschini D, Navarria P, Reggiori G, Tomatis S, Scorsetti M (2019) Predictive factors for survival of oligometastatic colorectal cancer treated with stereotactic body radiation therapy. Radiother Oncol 133:220–226. 10.1016/j.radonc.2018.10.024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greco C, Pares O, Pimentel N, Louro V, Morales J, Nunes B, Castanheira J, Oliveira C, Silva A, Vaz S, Costa D, Zelefsky M, Kolesnick R, Fuks Z (2019) Phenotype-oriented ablation of oligometastatic cancer with single dose radiation therapy. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 104(3):593–603. 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2019.02.033 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gundem G, Loo P, Kremeyer B, Alexandrov LB, Tubio JMC, Papaemmanuil E, Brewer DS, Kallio HML, Högnäs G, Annala M, Kivinummi K, Goody V, Latimer C, Omeara S, Dawson KJ, Isaacs W, Emmert-Buck MR, Nykter M, Foster C, Kote-Jarai Z, Easton D, Whitaker HC, Neal DE, Cooper CS, Eeles RA, Visakorpi T, Campbell PJ, Mcdermott U, Wedge DC, Bova GS (2015) The evolutionary history of lethal metastatic prostate cancer. Nature 520(7547):353–357. 10.1038/nature14347 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hellman S, Weichselbaum RR (1995) Oligometastases. J Clin Oncol 13:8–10 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoyer M, Roed D, Traberg Hansen A et al (2006) Phase II study on stereotactic body radiotherapy of colorectal metastases. Acta Oncol 45:823–830 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iijima Y, Hirotsu Y, Mochizuki H, Amemiya K, Oyama T, Uchida Y, Kobayashi Y, Tsutsui T, Kakizaki Y, Miyashita Y, Omata M (2018) Dynamic changes and drug-induced selection of resistant clones in a patient with EGFR-mutated adenocarcinoma that acquired T790M mutation and transformed to small-cell lung cancer. Clin Lung Cancer 19(6):e843–e847. 10.1016/j.cllc.2018.07.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim MY, Oskarsson T, Acharyya S, Nguyen DX (2009) Tumor self-seeding by circulating cancer cells. Cell 139(7):1315–1326 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klein CA (2013) Selection and adaptation during metastatic cancer progression. Nature 501:365–372. 10.1038/nature12628 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klement RJ, Abbasi-Senger N, Adebahr S, Alheid H, Allgaeuer M, Becker G, Blanck O, Boda-Heggemann J, Brunner T, Duma M, Eble MJ, Ernst I, Gerum S, Habermehl D, Hass P, Henkenberens C, Hildebrandt G, Imhoff D, Kahl H, Klass ND, Krempien R, Lewitzki V, Lohaus F, Ostheimer C, Papachristofilou A, Petersen C, Rieber J, Schneider T, Schrade E, Semrau R, Wachter S, Wittig A, Guckenberger M, Andratschke N (2019) The impact of local control on overall survival after stereotactic body radiotherapy for liver and lung metastases from colorectal cancer: a combined analysis of 388 patients with 500 metastases. BMC Cancer 19(1):173. 10.1186/s12885-019-5362-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mazzola R, Fersino S, Alongi P, Di Paola G, Gregucci F, Aiello D, Tebano U, Pasetto S, Ruggieri R, Salgarello M, Alongi F (2018a) Stereotactic body radiation therapy for liver oligometastases: predictive factors of local response by (18)F-FDG-PET/CT. Br J Radiol 91(1088):20180058. 10.1259/bjr.20180058 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mazzola R, Fersino S, Ferrera G, Targher G, Figlia V, Triggiani L, Pasinetti N, Lo Casto A, Ruggieri R, Magrini SM, Alongi F (2018b) Stereotactic body radiotherapy for lung oligometastases impacts on systemic treatment-free survival: a cohort study. Med Oncol 35(9):121. 10.1007/s12032-018-1190-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meijerink MR, Puijk RS, van Tilborg AAJM, Henningsen KH, Fernandez LG, Neyt M, Heymans J, Frankema JS, de Jong KP, Richel DJ, Prevoo W, Vlayen J (2018) Radiofrequency and microwave ablation compared to systemic chemotherapy and to partial hepatectomy in the treatment of colorectal liver metastases: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol 41(8):1189–1204. 10.1007/s00270-018-1959-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mihai A, Mu Y, Armstrong J, Dunne M, Beriwal S, Rock L, Thirion P, Heron DE, Bird BH, Westrup J, Murphy CG, Huq MS, McDermott R (2017) Patients with colorectal lung oligometastases (L-OMD) treated by dose adapted SABR at diagnosis of oligometastatic disease have better outcomes than patients previously treated for their metastatic disease. J Radiosurg SBRT 5(1):43–53 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milano MT, Philip A, Okunieff P (2009) Analysis of patients with oligometastases undergoing two or more curative-intent stereotactic radiotherapy courses. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 73:832–837 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milano MT, Katz AW, Zhang H, Okunieff P (2012) Oligometastases treated with stereotactic body radiotherapy: long-term follow-up of prospective study. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 83:878–886 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nicosia L, Franzese C, Mazzola R, Franceschini D, Rigo M, Dagostino G, Corradini S, Alongi F, Scorsetti M (2019) Recurrence pattern of stereotactic body radiotherapy in oligometastatic prostate cancer: a multi-institutional analysis. Strahlenther Onkol. 10.1007/s00066-019-01523-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osti MF, Agolli L, Valeriani M, Reverberi C, Bracci S, Marinelli L, De Sanctis V, Cortesi E, Martelli M, De Dominicis C, Minniti G, Nicosia L (2018) 30 Gy single dose stereotactic body radiation therapy (SBRT): report on outcome in a large series of patients with lung oligometastatic disease. Lung Cancer 122:165–170. 10.1016/j.lungcan.2018.06.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palma DA, Olson R, Harrow S, Gaede S, Louie AV, Haasbeek C, Mulroy L, Lock M, Rodrigues GB, Yaremko BP, Schellenberg D, Ahmad B, Griffioen G, Senthi S, Swaminath A, Kopek N, Liu M, Moore K, Currie S, Bauman GS, Warner A, Senan S (2019) Stereotactic ablative radiotherapy versus standard of care palliative treatment in patients with oligometastatic cancers (SABR-COMET): a randomised, phase 2, open-label trial. Lancet 393(10185):2051–2058. 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)32487-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petrelli F, Comito T, Barni S, Pancera G, Scorsetti M, Ghidini A (2018) SBRT for CRC liver metastases. Stereotactic body radiotherapy for colorectal cancer liver metastases: a systematic review. Radiother Oncol. 129(3):427–434. 10.1016/j.radonc.2018.06.035 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pinker K, Riedl C, Weber WA (2017) Evaluating tumor response with FDG PET: updates on PERCIST, comparison with EORTC criteria and clues to future developments. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging 44(Suppl 1):55–66. 10.1007/s00259-017-3687-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robin TP, Raben D, Schefter TE (2018) A contemporary update on the role of stereotactic body radiation therapy (SBRT) for liver metastases in the evolving landscape of oligometastatic disease management. Semin Radiat Oncol 28(4):288–294. 10.1016/j.semradonc.2018.06.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rusthoven KE, Kavanagh BD, Cardenes H et al (2009) Multiinstitutional phase I/II trial of stereotactic body radiation therapy for liver metastases. J Clin Oncol 27:1572–1578 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scorsetti M, Arcangeli S, Tozzi A, Comito T, Alongi F, Navarria P, Mancosu P, Reggiori G, Fogliata A, Torzilli G, Tomatis S, Cozzi L (2013) Is stereotactic body radiation therapy an attractive option for unresectable liver metastases? A preliminary report from a phase 2 trial. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 86(2):336–342. 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2012.12.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Triggiani L, Alongi F, Buglione M, Detti B, Santoni R, Bruni A, Maranzano E, Lohr F, D'Angelillo R, Magli A, Bonetta A, Mazzola R, Pasinetti N, Francolini G, Ingrosso G, Trippa F, Fersino S, Borghetti P, Ghirardelli P, Magrini SM (2017) Efficacy of stereotactic body radiotherapy in oligorecurrent and in oligoprogressive prostate cancer: new evidence from a multicentric study. Br J Cancer 116(12):1520–1525. 10.1038/bjc.2017.103 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valentí V, Ramos J, Pérez C, Capdevila L, Ruiz I, Tikhomirova L, Sánchez M, Juez I, Llobera M, Sopena E, Rubió J, Salazar R (2019) Increased survival time or better quality of life? Trade-off between benefits and adverse events in the systemic treatment of cancer. Clin Transl Oncol. 10.1007/s12094-019-02216-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yachida S, Jones S, Bozic I, Antal T, Leary R, Fu B, KamiyamaM HRH, Eshleman JR, Nowak MA, Velculescu VE, Kinzler KW, Vogelstein B, Iacobuzio-Donahue CA (2010) Distant metastasis occurs late during the genetic evolution of pan-creatic cancer. Nature 467:1114–1117. 10.1038/nature09515 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]