Abstract

Purpose

Thyroid cancer (TC), the most common endocrine malignancy, increases its incidence worldwide. MicroRNAs have been shown to be abnormally expressed in tumors and could represent valid diagnostic markers for patients affected by TC. Our aim was to analyze the expression of tumorsuppressor hsa-let7b-5p and hsa-let7f-5p, together with their predicted targets SLC5A5 (NIS) and HMGA2, in papillary (PTC), follicular (FTC) and anaplastic (ATC).

Methods

8 FTC, 14 PTC, 12 ATC and three normal thyroid tissue samples were analyzed for the expression of pre-let7b, hsa-let7b-5p and hsa-let7f-5p as SLC5A5 and HMGA2 by RT-qPCR. Data were analyzed by REST 2008.

Results

FTC patients showed a significant down-regulation of hsa-let7b-5p and its precursor. hsa-let7f-5p was overexpressed, and SLC5A5 was strongly suppressed. HMGA2 was overexpressed, reflecting no correlation with its regulatory let7 miRNAs. PTC samples were characterized by up-regulation of hsa-let7b-5p, its precursor and hsa-let7f-5p. SLC5A5 was strongly suppressed in comparison with normal thyroid tissue. HMGA2 was overexpressed, as shown in FTC, also. ATC samples showed a similar miRNAs profile as PTC. In contrast with FTC and PTC, these patients showed a stable or up-regulated SLC5A5 and HMGA2.

Conclusions

Expression of HMGA2 is not correlated with the regulatory let7 miRNAs. Interestingly, SLC5A5 was down-regulated in FTC and PTC. Its expression could be modulated by hsa-let-7f-5p. ATC showed a loss of SLC5A5/hsa-let7f-5p correlation. SLC5A5, in ATC, needs further investigation to clarify the genetic/epigenetic mechanism altering its expression.

Keywords: miRNAs, let7, Thyroid cancer, Diagnostic markers, Epigenetic

Introduction

Thyroid cancer (TC) is the most common endocrine malignant tumor, and its incidence is increasing worldwide (Jemal et al. 2011; Pellegriti et al. 2013). The majority of these tumors is classified as differentiated thyroid carcinomas (DTCs) and can be distinguished by histopathological characteristics in follicular (FTC) and papillary (PTC) thyroid cancer. For these cancers, well-established therapy options, leading to favorable prognosis, are available. Poorly differentiated thyroid carcinomas (PDTC) and anaplastic thyroid cancer (ATC) are characterized by further dedifferentiation, high metastatic potential and failure of radioiodine response (Hsu et al. 2014), resulting in poor patient outcome and short survival rate.

Resistance to radioiodine is caused by dysfunction of the sodium–iodide symporter (NIS), mainly due to suppression or loss of NIS gene (SLC5A5) (Dohan and Carrasco 2003; Dohan et al. 2003; Filetti et al. 1999) or even for a distorted alignment of NIS protein at the cytosolic membrane site, as previously shown (Wapnir et al. 2003). However, whereas NIS expression can be used to assess patients’ risk and response to therapy, its value as diagnostic and prognostic marker is uncertain.

In recent years, the role of microRNAs (miRNAs) in various malignant tumors has been intensely studied (Gottardo et al. 2007). Several observations suggest for miRNAs a diagnostic, prognostic and therapeutical potential (Croce 2008). Further studies also highlighted the occurrence of miRNAs cluster mutations as a main cause of cancer development (Calin and Croce 2006). Concerning TC, miRNAs profile was analyzed in tissue biopsies and fine-needle aspirations (FNA) in order to classify the histological tumor types. As shown by Keutgen XM et al., a combination of three to four miRNAs could represent an efficient diagnostic value. In particular, the expression of hsa-miR-222, hsa-miR-328, hsa-miR-197 and hsa-miR-215, in fine-needle aspiration of thyroid nodules, could discriminate between malignant and benign indeterminate lesions with a sensitivity of 100 % (Keutgen et al. 2012).

The function exerted by miRNAs is based on the translational repression of their target mRNA. Recently, SLC5A5 has been suggested to be a target of miRNAs hsa-miR-146b (Li et al. 2015) and hsa-miR-339-5p (Lakshmanan et al. 2015) and in silico analysis also revealed SLC5A5 as putative target of hsa-let7f-5p.

Similar to the loss or dysfunction of NIS, HMGA2, belonging to a family of small chromatin associated non-histone proteins that act as architectural transcription factor, is positively correlated with malignant phenotype in human thyroid neoplasias (Chiappetta et al. 2008; Jin et al. 2011). HMGA2 is normally expressed during embryogenesis and tissue development and suppressed in normal differentiated tissue. Its over-expression has been shown in several benign and malignant tumors, and it is inversely correlated with the expression of Let-7 family miRNAs (Di Fazio et al. 2012; Pallante et al. 2015). Let-7 family miRNAs have been shown to be highly expressed in normal thyroid tissue (Marini et al. 2011). Up to now, the correlation between HMGA2 and let-7 miRNAs in TC has not been analyzed yet.

In this study, we aimed to analyze the expression of let7 miRNAs and their related targets NIS and HMGA2 in a panel of TC samples with different histopathological characteristics. Possible differences in miRNAs expression in relation with the various TC entities could improve the diagnostic and pre-operative staging of patients affected by thyroid malignancies.

Materials and methods

Sample collection

Tissue samples were randomly collected and stored at low temperature from only 10 % of patients affected by thyroid malignancy, whose underwent surgical operation at the University Hospital of Marburg. 14 PTC, 8 FTC and 12 ATC tissue samples were included in the study from samples collected between 1998 and 2012. Normal thyroid tissue from regions, adjacent to the tumor area, was collected as well and served as control tissue. All samples were snap-frozen and stored at −80 °C. Only, two FTC and one ATC tissue samples were excluded from the study because the RNA was not measurable. The study was conducted under the approval of the ethic committee of Marburg University Hospital (Nr. 166/09), and all patients signed out the inform consent.

RNA isolation

Total RNA, including short RNA, was isolated from FTC, PTC and ATC tissue samples. Directly after thawing, 50 mg of tissue was suspended in 1 ml Qiazol (Qiagen) and lysed with Fast-Prep 24 (MPBio) tissue homogenizer at 4 m/s speed for 60 s. Lysates were processed with miRNeasy Mini Kit (Qiagen) by following the manufacturer protocol. Total RNA amount was measured with Nanodrop, and its quality was assessed by the 260/280 absorbance ratio.

In silico analysis

In order to reveal potential targets of these miRNAs, we performed in silico analysis in four independent databases: miRanda (http://www.microrna.org), miRDB (http://mirdb.org/miRDB/), RNA22-HSA (https://cm.jefferson.edu/rna22/) and TargetScanHuman (http://www.targetscan.org).

RT-qPCR

miRNA-enriched RNA lysates were reverse transcribed with miScript II RT Kit (Qiagen). cDNA was amplified with miScript SYBR Green PCR Kit by using Pre-let7b (MP00000028) hsa-let-7b-5p (MS00003122) and hsa-let-7f-5p (MS00006489 miScript Primer Assays (Qiagen). RNU6B (MS00029204) was amplified as internal control miRNA as previously published (Keutgen et al. 2012).

For the amplification of HMGA2 and NIS, Sso Fast Eva Green from Bio-Rad was used. HMGA2 (QT01157674), NIS (PPH10926A) and GAPDH (QT01192646) were purchased from Qiagen; qPCR was run on CFX96 (Bio-Rad). GAPDH was amplified as housekeeping gene transcript and used for normalization of target genes expression. Normal thyroid tissue was also processed for miRNAs and targets expression.

For final representation, PCR data (fold change compared to normal thyroid tissue) were classified as follows: ↑ 10, ↑↑ 100, ↑↑↑ 1000, ↑↑↑↑ > 100-fold and ↓ < 0.5, ↓↓ < 0.1, ↓↓↓ < 0.01-fold.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis of PCR results was performed using CFX Manager (Bio-Rad) and Rest 2008. Significance was calculated using the t-test for paired samples. p < 0.01 and p < 0.05 were regarded as significant.

Results

In silico analysis reveals potential targets of hsa-let7b-5p and hsa-let7f-5p

In order to reveal potential targets of these miRNAs, we performed in silico analysis in four independent databases: miRanda (http://www.microrna.org), miRDB (http://mirdb.org/miRDB/), RNA22-HSA (https://cm.jefferson.edu/rna22/) and TargetScanHuman (http://www.targetscan.org). HMGA2 was found as validated target of hsa-let7b-5p and hsa-let7f-5p. SLC5A5 was found to be target of hsa-let7f-5p (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

In silico analysis of miRNAs predicted targets. Here is listed the number of predicted targets of hsa-let7b-5p and hsa-let7f-5p

Expression of let7 family miRNAs in follicular, papillary and anaplastic thyroid cancer

Expression of hsa-let7b-5p and its precursor form as well as hsa-let7f-5p were analyzed in FTC, PTC and ATC samples in comparison with normal thyroid tissue. As shown in Fig. 2, upper panel, hsa-let7b-5p and pre-let7b were strongly suppressed in 7 out of 8 FTC samples and slightly (about tenfold) over-expressed in one sample.

Fig. 2.

miRNAs expression in papillary, follicular and anaplastic thyroid cancer. Expression of Pre-let-7b, hsa-let-7b-5p and hsa-let-7f-5p was performed in follicular (upper panel), papillary (lower left panel) and anaplastic (lower right panel) thyroid cancer samples by RT-qPCR. MiRNAs expression was normalized to RNU6B, and results are expressed relative to normal thyroid tissue set at 1.0. Shown are mean ± SEM of three independent experiments performed in triplicates

PTC samples (Fig. 2, lower left panel) were characterized by a significant over-expression of hsa-let7b-5p and its precursor Pre-let7b in 12 out of 14 samples.

In the ATC group, hsa-let7b-5p was not detectable in 3 out of 12 samples. All other samples showed a stable or slightly (<0.5-fold) down-regulated level of hsa-let7b-5p and its precursor Pre-let7b (Fig. 2, lower right panel).

In conclusion, it was observed that hsa-let7b-5p and its precursor form were strongly suppressed in FTC only, whereas they are stable (ATC) or even over-expressed in PTC samples.

Concerning hsa-let7f-5p, it was homogeneously over-expressed in all FTC samples (about tenfold, one sample >100-fold) (Fig. 2, upper panel).

As shown in Fig. 2 (lower left panel), the PTC group was characterized by a significant over-expression of hsa-let7f-5p (about 100-fold, two times up to 106-fold).

Moreover, in ATC samples, hsa-let7f-5p was strongly overexpressed (over 100-fold change) in 9 out of 12 samples, while it was not detectable in three samples only.

In conclusion, hsa-let7f-5p was found to be generally over-expressed in TC samples with higher levels in the PTC and ATC compared to the FTC group (see Table 1).

Table 1.

Schematic representation of HMGA2, SLC5A5, pre-let7-b, hsa-let7b-5p, hsa-let7f-5p in PTC, FTC and ATC samples

PCR data (fold change compared to normal thyroid tissue) were classified as follows: ↑ 10, ↑↑ 100, ↑↑↑ 1000, ↑↑↑↑ > 100-fold and ↓ < 0.5, ↓↓ < 0.1, ↓↓↓ < 0.01-fold

HMGA2 expression in follicular, papillary and anaplastic thyroid cancer tissue

In patients affected by FTC (Fig. 3, upper panel), only one showed no expression of HMGA2. One patient had a significant down-regulation, while all other samples (6/8) showed a significant over-expression (10- to 1000-fold) in comparison with normal thyroid tissue.

Fig. 3.

HMGA2 in thyroid cancer. RT-qPCR of HMGA2 transcript in samples of follicular (upper panel), papillary (lower left panel) and anaplastic (lower right panel) thyroid cancer. MRNA expression was normalized to GAPDH, and results are expressed relative to normal thyroid tissue set at 1.0. Shown are mean ± SEM of three independent experiments performed in triplicates

HMGA2 was expressed in 13 out of 14 patients suffering from PTC (Fig. 3, lower left panel). Tissue samples of two patients showed a significant down-regulation (<0.5) of HMGA2 and one patient a stable expression. The majority of analyzed samples (10 out of 13) showed an overall significant overexpression (up to 100-fold) of HMGA2.

In ATC patients (Fig. 3, lower right panel), HMGA2 expression was heterogeneous: five samples showed no HMGA2 expression; in 6 out of 12 samples, HMGA2 resulted significantly overexpressed (about 100-fold); one patient showed a stable expression of the HMGA2 transcript only.

In conclusion, almost all PTC and FTC patient samples showed an overexpression of HMGA2. In ATC samples, HMGA2, if detectable, was over-expressed also (see Table 1).

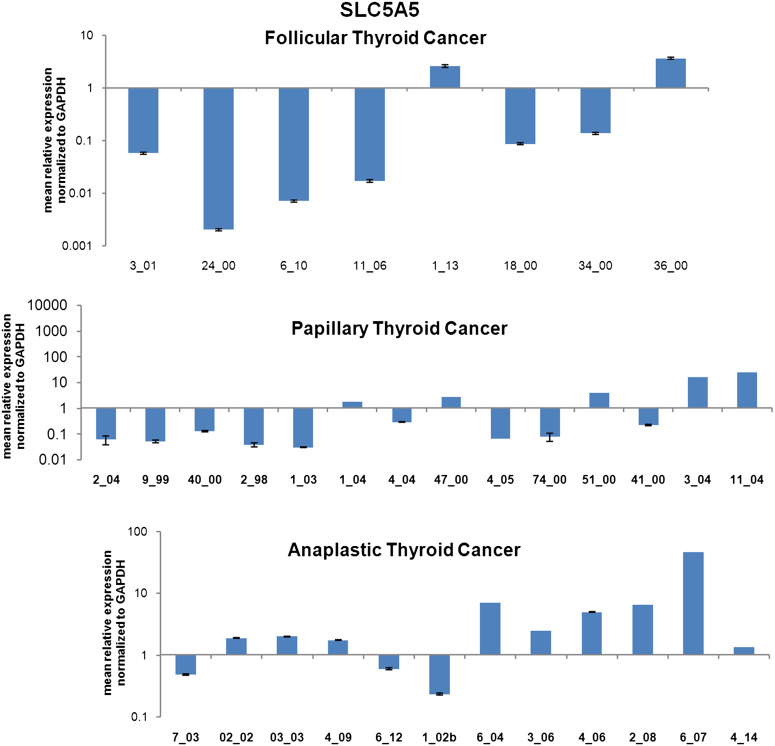

SLC5A5 expression in follicular, papillary and anaplastic thyroid cancer tissue

In the FTC group, 6 out of 8 samples were characterized by a significant suppression (<0.5-fold to <0.01-fold) of SLC5A5 transcript. Only, two samples showed a stable expression of SLC5A5 compared to normal thyroid tissue (Fig. 4, upper panel).

Fig. 4.

SLC5A5 (NIS) expression in thyroid cancer. RT-qPCR of SLC5A5 transcript in samples of follicular (upper panel), papillary (middle panel) and anaplastic (lower panel) thyroid cancer. MRNA expression was normalized to GAPDH, and results are expressed relative to normal thyroid tissue set at 1.0. Shown are mean ± SEM of three independent experiments performed in triplicates

Ten out of fourteen samples from PTC patients showed a potent suppression of SLC5A5 (<0.5- to <0.1-fold), while four showed a stable expression or a slight up-regulation of its transcript (Fig. 4, middle panel).

In the ATC group, SLC5A5 was differently expressed. Five out of twelve patients showed a significant over-expression (onefold to tenfold), three a significant down-regulation (<0.5-fold) and four a stable expression of the SLC5A5 transcript.

As shown, SLC5A5 is strongly suppressed in FTC and PTC patients, whereas it showed a stable or up-regulated expression in the majority of ATC analyzed samples (see Table 1).

Discussion

In the last decades, several studies have shown that miRNAs are implicated in thyroid tumorigenesis and indicated them as potential tumor markers to ameliorate the preoperative medical decision. Let-7 family miRNAs are well known for their tumor suppressor activity, and they are expressed in normal thyroid gland (Marini et al. 2011). Our study focused on the analysis of hsa-let7b-5p and hsa-let7f-5p, together with their predicted targets HMGA2 and SLC5A5, in PTC and, for the first time, in FTC and ATC also.

hsa-let-7b-5p and its precursor form were suppressed in FTC samples. Interestingly, an over-expression of hsa-let7b-5p was found in the majority of analyzed PTC and a stable expression of it in the majority of ATC samples. Consequently, hsa-let-7b-5p expression could be assumed as valid diagnostic biomarker for the classification of PTC and ATC in contrast to FTC.

hsa-let7f-5p, another member of let7 miRNA family, was found upregulated in all histopathological subgroups of TC. hsa-let7f-5p exerts a tumorsuppressor role by reducing cell proliferation and inducing thyroid differentiation markers in TPC1 papillary thyroid cancer cell line (Ricarte-Filho et al. 2009). So, it could be possible that the over-expression of hsa-let-7f-5p mitigates the tumor aggressiveness of PTC- and FTC-affected patients used for our study. Surprisingly, hsa-let-7f-5p was over-expressed in the more aggressive ATCs as well, which is in contrast with the general observed expression of let7 family miRNAs in solid tumors (Gottardo et al. 2007).

This study focused also on some of the deputed targets of the previously mentioned miRNAs. In particular, HMGA2, a non-transcriptional factor with oncogenic property, has been predicted by miRNA databases as best putative target for all miRNAs belonging to let7 family. Furthermore, HMGA2 has been found to be inversely correlated with the expression of let7 family miRNAs (Di Fazio et al. 2012; Madison et al. 2015), and its overexpression is associated with poor outcome and worse prognosis in solid malignancies (Chiappetta et al. 2008; Pallante et al. 2015). Here, HMGA2 was found overall up-regulated in samples of patients suffering from FTC, PTC and ATC and, as previously described it can be a valid diagnostic marker for thyroid malignancies, especially by quantification of its PCR product in tumor tissue samples and fine-needle aspirates (Chiappetta et al. 2008; Lappinga et al. 2010).

However, the well-known inverse correlation between HMGA2 and let-7 miRNAs could not be confirmed for TC samples included in this study. All three thyroid tumor subtypes showed an over-expression of at least hsa-let-7f-5p and HMGA2 at the same time. Maybe, the significant overexpression of HMGA2 can be attributed to an inhibition of its interaction with let-7 miRNAs caused by the long non-coding RNA H19, as it has been shown in pancreatic cancer already (Ma et al. 2014). Furthermore, it was reported that repression of HMGA2 by let-7 can be disrupted by mutation of the HMGA2 gene, which leads to a HMGA2 transcript missing the binding site for let-7. (Mayr et al. 2007). Therefore, further investigations are necessary to clarify the functional relationship between let-7 miRNAs and HMGA2, especially with regard to possible therapeutic approaches.

To further characterize the effect of miRNAs expression in thyroid malignancies, SLC5A5 expression was quantified in FTC, PTC and ATC samples. SLC5A5 was found to be the best predicted target of hsa-let-7f-5p. Interestingly, the majority of FTC and PTC samples showed a significant down-regulation of SLC5A5 expression. Thus, it inversely correlates with hsa-let-7f-5p overexpression. In addition, it could not be excluded that a mutation of B-RAF at the codon V600 occurred in these patients, contributing to SLC5A5 suppression (Choi et al. 2014). In contrast, half of the ATC samples showed an up-regulation of SLC5A5, thus lacking any distinct correlation with hsa-let-7f-5p. The misleading result concerning SLC5A5 (NIS) expression in the radio iodide-resistant ATC could be attributed to an aberrant overexpression of SLC5A5 bearing a mutation causing a loss of function, as previously shown, leading to iodine trapping defect (Liang et al. 2005).

Nowadays, it has been shown that epigenetic modifications occurring at histone and non-histone proteins could preferentially induce the re-expression of tumorsuppressor miRNAs and genes in several malignancies (Di Fazio et al. 2012; Ngamphaiboon et al. 2015), including thyroid cancer (Baldan et al. 2015; Jang et al. 2015). In particular, the use of deacetylase inhibitors promotes the re-expression of functional sodium–iodide symporter and induces differentiation in poorly differentiated thyroid tumors (Zhang et al. 2015), with regression of metastatic potential (Zhang et al. 2015) and promotion of cell death (Kim et al. 2015; Weinlander et al. 2014).

In our study, hsa-let-7b-5p was suppressed in FTC samples. The possibility to promote its re-expression by the use of deacetylase inhibitors could represent a new strategy for the treatment of this thyroid malignancy, assuming that hsa-let-7b-5p could inhibit HMGA2 leading to a differentiated status of FTC. Additionally, the stable expression of this miRNA in PTC and ATC samples, shown here for the first time, could give an advantage to classify those tumors bearing an expression of hsa-let-7b-5p.

Further studies are needed to better clarify the role of hsa-let7f-5p in thyroid cancer and how its modulation could balance the expression of an oncogene like HMGA2 and the differentiation marker for thyroid cancer like SLC5A5.

Further studies are needed to better understand the status of SLC5A5 in thyroid cancer. The analysis of the genetic alteration of the sodium–iodide symporter could clarify its aberrant expression in FTC, PTC and its possible loss of function in anaplastic thyroid cancer.

Acknowledgments

SE was supported by a grant from Kempkes Foundation.

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Ethical approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Footnotes

Alexander I. Damanakis and Sabine Eckhardt have contributed equally to this article.

References

- Baldan F, Mio C, Allegri L, Puppin C, Russo D, Filetti S, Damante G (2015) Synergy between HDAC and PARP inhibitors on proliferation of a human anaplastic thyroid cancer-derived cell line. Int J Endocrinol 2015:978371. doi:10.1155/2015/978371 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calin GA, Croce CM (2006) MicroRNA signatures in human cancers. Nat Rev Cancer 6:857–866. doi:10.1038/nrc1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiappetta G et al (2008) HMGA2 mRNA expression correlates with the malignant phenotype in human thyroid neoplasias. Eur J Cancer 44:1015–1021. doi:10.1016/j.ejca.2008.02.039 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi YW et al (2014) B-RafV600E inhibits sodium iodide symporter expression via regulation of DNA methyltransferase 1. Exp Mol Med 46:e120. doi:10.1038/emm.2014.68 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Croce CM (2008) Oncogenes and cancer. N Engl J Med 358:502–511. doi:10.1056/NEJMra072367 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Fazio P et al (2012) Downregulation of HMGA2 by the pan-deacetylase inhibitor panobinostat is dependent on hsa-let-7b expression in liver cancer cell lines. Exp Cell Res 318:1832–1843. doi:10.1016/j.yexcr.2012.04.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dohan O, Carrasco N (2003) Advances in Na(+)/I(-) symporter (NIS) research in the thyroid and beyond. Mol Cell Endocrinol 213:59–70. doi:10.1016/j.mce.2003.10.059 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dohan O et al (2003) The sodium/iodide Symporter (NIS): characterization, regulation, and medical significance. Endocr Rev 24:48–77. doi:10.1210/er.2001-0029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Filetti S, Bidart JM, Arturi F, Caillou B, Russo D, Schlumberger M (1999) Sodium/iodide symporter: a key transport system in thyroid cancer cell metabolism. Eur J Endocrinol 141:443–457. doi:10.1530/eje.0.1410443 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gottardo F et al (2007) Micro-RNA profiling in kidney and bladder cancers. Urol Oncol 25:387–392. doi:10.1016/j.urolonc.2007.01.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsu KT et al (2014) Novel approaches in anaplastic thyroid cancer therapy. Oncologist 19:1148–1155. doi:10.1634/theoncologist.2014-0182 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jang S et al (2015) Novel analogs targeting histone deacetylase suppress aggressive thyroid cancer cell growth and induce re-differentiation. Cancer Gene Ther 22:410–416. doi:10.1038/cgt.2015.37 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jemal A, Bray F, Center MM, Ferlay J, Ward E, Forman D (2011) Global cancer statistics. CA Cancer J Clin 61:69–90. doi:10.3322/caac.20107 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jin L et al (2011) HMGA2 expression analysis in cytological and paraffin-embedded tissue specimens of thyroid tumors by relative quantitative RT-PCR. Diagn Mol Pathol 20:71–80. doi:10.1097/PDM.0b013e3181ed784d [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keutgen XM et al (2012) A panel of four miRNAs accurately differentiates malignant from benign indeterminate thyroid lesions on fine needle aspiration. Clin Cancer Res 18:2032–2038. doi:10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-11-2487 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim SH, Kang JG, Kim CS, Ihm SH, Choi MG, Yoo HJ, Lee SJ (2015) Novel heat shock protein 90 inhibitor NVP-AUY922 synergizes with the histone deacetylase inhibitor PXD101 in induction of death of anaplastic thyroid carcinoma cells. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 100:E253–E261. doi:10.1210/jc.2014-3101 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lakshmanan A, Wojcicka A, Kotlarek M, Zhang X, Jazdzewski K, Jhiang SM (2015) microRNA-339-5p modulates Na+/I− symporter-mediated radioiodide uptake. Endocr Relat Cancer 22:11–21. doi:10.1530/ERC-14-0439 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lappinga PJ, Kip NS, Jin L, Lloyd RV, Henry MR, Zhang J, Nassar A (2010) HMGA2 gene expression analysis performed on cytologic smears to distinguish benign from malignant thyroid nodules. Cancer Cytopathol 118:287–297. doi:10.1002/cncy.20095 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li L et al (2015) Inhibition of miR-146b expression increases radioiodine-sensitivity in poorly differential thyroid carcinoma via positively regulating NIS expression. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 462:314–321. doi:10.1016/j.bbrc.2015.04.134 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liang JA, Chen CP, Huang SJ, Ho TY, Hsiang CY, Ding HJ, Wu SL (2005) A novel loss-of-function deletion in sodium/iodide symporter gene in follicular thyroid adenoma. Cancer Lett 230:65–71. doi:10.1016/j.canlet.2004.12.036 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma C, Nong K, Zhu H, Wang W, Huang X, Yuan Z, Ai K (2014) H19 promotes pancreatic cancer metastasis by derepressing let-7’s suppression on its target HMGA2-mediated EMT. Tumour Biol 35:9163–9169. doi:10.1007/s13277-014-2185-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Madison BB, Jeganathan AN, Mizuno R, Winslow MM, Castells A, Cuatrecasas M, Rustgi AK (2015) Let-7 represses carcinogenesis and a stem cell phenotype in the intestine via regulation of Hmga2. PLoS Genet 11:e1005408. doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.1005408 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marini F, Luzi E, Brandi ML (2011) MicroRNA role in thyroid cancer development. J Thyroid Res 2011:407123. doi:10.4061/2011/407123 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mayr C, Hemann MT, Bartel DP (2007) Disrupting the pairing between let-7 and Hmga2 enhances oncogenic transformation. Science 315:1576–1579. doi:10.1126/science.1137999 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ngamphaiboon N et al (2015) A phase I study of the histone deacetylase (HDAC) inhibitor entinostat, in combination with sorafenib in patients with advanced solid tumors. Invest New Drugs 33:225–232. doi:10.1007/s10637-014-0174-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pallante P, Sepe R, Puca F, Fusco A (2015) High mobility group a proteins as tumor markers. Front Med (Lausanne) 2:15. doi:10.3389/fmed.2015.00015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pellegriti G, Frasca F, Regalbuto C, Squatrito S, Vigneri R (2013) Worldwide increasing incidence of thyroid cancer: update on epidemiology and risk factors. J Cancer Epidemiol 2013:965212. doi:10.1155/2013/965212 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ricarte-Filho JC, Fuziwara CS, Yamashita AS, Rezende E, da-Silva MJ, Kimura ET (2009) Effects of let-7 microRNA on cell growth and differentiation of papillary thyroid cancer. Transl Oncol 2:236–241 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wapnir IL et al (2003) Immunohistochemical profile of the sodium/iodide symporter in thyroid, breast, and other carcinomas using high density tissue microarrays and conventional sections. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 88:1880–1888. doi:10.1210/jc.2002-021544 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weinlander E et al (2014) The novel histone deacetylase inhibitor thailandepsin A inhibits anaplastic thyroid cancer growth. J Surg Res 190:191–197. doi:10.1016/j.jss.2014.02.042 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang L et al (2015) Dual inhibition of HDAC and EGFR signaling with CUDC-101 induces potent suppression of tumor growth and metastasis in anaplastic thyroid cancer. Oncotarget 6:9073–9085 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]