Abstract

The ventrolateral pallial (VLp) excitatory neurons in the claustro-amygdalar complex and piriform cortex (PIR; which forms part of the palaeocortex) form reciprocal connections with the prefrontal cortex (PFC), integrating cognitive and sensory information that results in adaptive behaviours1–5. Early-life disruptions in these circuits are linked to neuropsychiatric disorders4–8, highlighting the importance of understanding their development. Here we reveal that the transcription factors SOX4, SOX11 and TFAP2D have a pivotal role in the development, identity and PFC connectivity of these excitatory neurons. The absence of SOX4 and SOX11 in post-mitotic excitatory neurons results in a marked reduction in the size of the basolateral amygdala complex (BLC), claustrum (CLA) and PIR. These transcription factors control BLC formation through direct regulation of Tfap2d expression. Cross-species analyses, including in humans, identified conserved Tfap2d expression in developing excitatory neurons of BLC, CLA, PIR and the associated transitional areas of the frontal, insular and temporal cortex. Although the loss and haploinsufficiency of Tfap2d yield similar alterations in learned threat-response behaviours, differences emerge in the phenotypes at different Tfap2d dosages, particularly in terms of changes observed in BLC size and BLC–PFC connectivity. This underscores the importance of Tfap2d dosage in orchestrating developmental shifts in BLC–PFC connectivity and behavioural modifications that resemble symptoms of neuropsychiatric disorders. Together, these findings reveal key elements of a conserved gene regulatory network that shapes the development and function of crucial VLp excitatory neurons and their PFC connectivity and offer insights into their evolution and alterations in neuropsychiatric disorders.

Subject terms: Developmental biology, Neuronal development, Evolution

A conserved gene regulatory network involving SOX4, SOX11 and TFAP2D shapes the development of excitatory neurons in ventrolateral pallium and their connectivity with the prefrontal cortex.

Main

During embryonic development, pallial–subpallial boundary (PSB) progenitors give rise to immature excitatory neurons, which migrate via the lateral cortical stream (LCS) towards VLp, into the BLC and PIR primordia9–18. Although the patterning and differentiation of these progenitors are well studied, the molecular mechanism governing the specification and connectivity of excitatory neurons within these VLp structures has remained largely unexplored. Here we identify an evolutionarily divergent yet parallel gene regulatory network comprising SOX4, SOX11 and TFAP2D, which orchestrates the post-mitotic, cell-autonomous specification of BLC and PIR excitatory neuron features, including their projections to the PFC, and their functional contributions.

SOX4 and SOX11 regulate VLp development

In prior observations, we noted that depletion of the transcription factors SOX4 and SOX11 from Emx1-expressing cortical progenitors resulted in notable developmental defects in the cerebral cortex19. These defects included the loss of Fezf2 expression, disruption laminar specification of excitatory neurons, and impaired corticospinal tract formation. Furthermore, SOX4 and SOX11 are expressed in immature cerebral excitatory neurons, yet their specific post-mitotic functions remain poorly understood beyond these phenotypes19–21. To investigate these functions, we bred Neurod6-cre;CAT-Gfp mice with Sox4fl/fl and Sox11fl/fl mice to selectively eliminate post-mitotic expression of both Sox4 and Sox11 from cerebral excitatory neurons (Sox4/Sox11 conditional double knockout (cdKO)) while simultaneously marking these cells with green fluorescent protein (GFP). Given the observed redundancy in the function of SOX4 and SOX1119,20, Sox4-conditional knockout (cKO) and Sox11-cKO mice did not exhibit noticeable phenotypic defects compared with control littermates at postnatal day 0 (PD0) (Fig. 1a and Extended Data Figs. 1a,b and 2a,c). Similar to our previous observations19, brains of Sox4/Sox11-cdKO mice showed phenotypic defects in corticospinal tract and cortical layer formation, highlighting post-mitotic functions of SOX4 and SOX11 (Extended Data Fig. 1a,b). Further, in Sox4/Sox11-cdKO mice, we observed pronounced reduction of VLp size, encompassing the BLC, CLA and PIR (Fig. 1a and Extended Data Fig. 1a). Notably, these structures also express both Sox4 and Sox11 during development19. Nissl staining, in situ hybridization and immunostaining for markers outlining nuclei of the amygdala confirmed that Sox4/Sox11-cdKO mice almost entirely lacked BLC, which comprises the basolateral (BLA), lateral (LA) and basomedial (BMA) nuclei, at PD0 (Fig. 1a and Extended Data Fig. 2a). Specifically, Lmo3 and SATB1 comprehensively delineated the entire BLC; Etv1 and Mef2c distinctly marked BLA and LA, respectively; and Cyp26b1 prominently labelled both the BLA and the central amygdala nuclei18,19,22. Additionally, NR4A2 (also known as NURR1) immunostaining revealed a reduction in the size of the endopiriform nucleus (EP) and CLA in Sox4/Sox11-cdKO brains (Extended Data Fig. 2a).

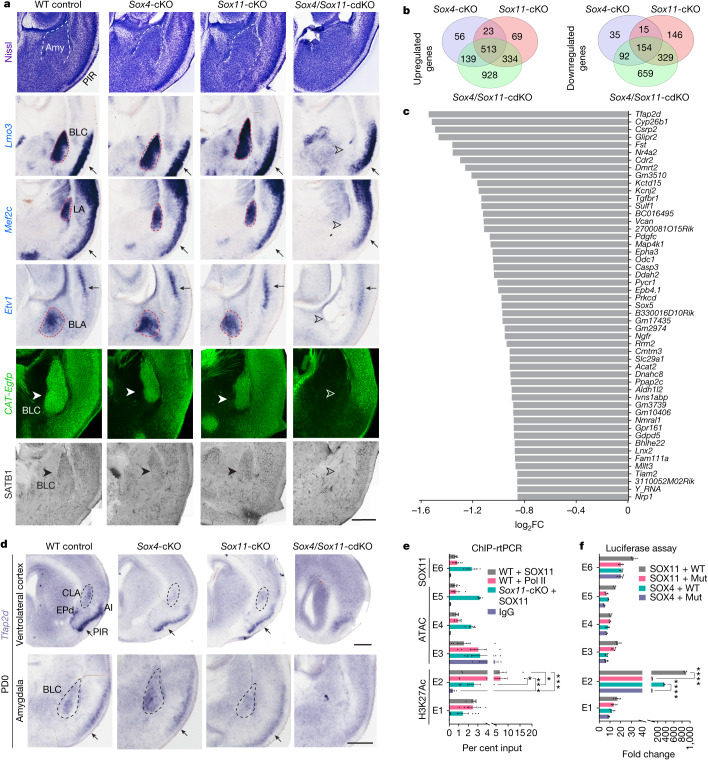

Fig. 1. Regulation of VLp development and Tfap2d expression by SOX4 and SOX11.

a, Coronal sections from VLp of mouse brains from wild-type (WT), Sox4-cKO, Sox11-cKO and Sox4/Sox11-cdKO mice. Nissl staining highlights the BLC. In situ hybridization for Lmo3, Mef2c and Etv1 marks BLC, LA and BLA, whereas GFP and SATB1 immunostaining labels BLC. White and black filled arrowheads highlight normal phenotypes and open arrowheads highlight defective phenotypes. Scale bar, 200 μm. b, Intersection of differentially expressed genes in Sox4-cKO, Sox11-cKO and Sox4/Sox11-cdKO cortex and amygdala compared with controls (n = 3 per genotype). c, Top 50 genes with decreased expression in Sox4/Sox11-cdKO samples over Sox4-cKO, Sox11-cKO and control samples. FC, fold change. d, In situ hybridization for Tfap2d in the VLp of control, Sox4-cKO, Sox11-cKO and Sox4/Sox11-cdKO brains. Scale bars, 500 μm. e, Quantitative PCR showing the percentage of input of six potential Tfap2d enhancers (E1–E6) after ChIP on PCD15.5 wild-type and Sox11-cKO cortices, targeting IgG, SOX11 or Pol II. Two-way ANOVA with multiple comparisons and Tukey’s correction. Data are mean ± s.e.m. WT + SOX11 immunoprecipitation versus IgG: P = 0.0006; WT + Pol II immunoprecipitation versus IgG: P = 0.0003; WT + SOX11 immunoprecipitation versus Sox11-cKO: P = 0.033; WT + Pol II immunoprecipitation versus Sox11-cKO: P = 0.018. SOX11 and Pol II: n = 6; IgG: n = 3. f, Luciferase activity driven by the Tfap2d enhancers E1–E6 and mutants (Mut) for SOX4 and SOX11 binding sites in the presence SOX4 or SOX11 as measured by firefly luciferase/Renilla luciferase ratio. Data are normalized to enhancer activity in the absence of SOX4 or SOX11. Two-way ANOVA with Tukey’s correction. Data are mean ± s.e.m. n = 3 per condition. Detailed statistics are presented in Supplementary Table 6. AI, anterior insula; Amy, amygdala; EPd, EP, dorsal part. ****P < 0.0001. In a,d, slanted arrows point to PIR; horizontal arrows point to neocortex; and hollow arrowheads point to loss of BLC in Sox4/Sox11-cdKO.

Extended Data Fig. 1. Loss of Sox4 and Sox11 disrupts laminar organization and axonal projections of cortical excitatory neurons.

a) Serial sections of control, Sox4-cKO, Sox11-cKO and Sox4; Sox11-cdKO mice brains at PD 0. Filled arrows point to normal phenotype and open arrowhead point to defective phenotypes in the knockouts. b) Representative images illustrate immunostaining for CUX1 and BCL11B in the cerebral cortex, highlighting disrupted laminar organization and decreased density nuclei with pronounced BCL11B immunosignal in the Sox4; Sox11-cdKO brains, in contrast to control, Sox4-cKO, and Sox11-cKO samples. AC, anterior commissure; CC, corpus callosum; CP, cerebral peduncles; CST, corticospinal tract; CTA, corticothalamic axons; HC, hippocampal commissure; HIP, hippocampus; IC, internal capsule; L, layer.

Extended Data Fig. 2. Sox4 and Sox11 orchestrate VLC formation by regulating Tfap2d expression for cell survival, and development of VLp.

a) Coronal sections of the in situ hybridization for Cyp26b1 (upper panel) and immunostaining for NR4A2 validating their downregulation in the ventrolateral cortical structures- including BLC, CLA, and ENTI in Sox4; Sox11-cdKO as compared to control, Sox4-cKO, and Sox11-cKO brains. In all genotypes, Cyp26b1 expression is robust in the CEA, the GABAergic inhibitory center of amygdala. b) Bar graph showing top 50 genes that have increased in expression in Sox4; Sox11-cdKO samples as compared to Sox4-cKO, Sox11-cKO and control within cortex and amygdala at PD 0. c) Representative images showing the immunostaining for GFAP and IBA1 along with TUNEL assay to depict the cell damage, astrocytes and microglia invasion in the Sox4; Sox11-cdKO as compared to the control and Sox4-cKO, Sox11-cKO cortices at PD 0. CEA, central nucleus of the amygdala; CLA, claustrum; ENTI, entorhinal cortex; LA, lateral nucleus of the amygdala. d) Line graphs showing the forebrain H3K27ac32 and ATAC peaks33 and SOX11 ChIP-seq sites29 from ages PCD 11-16, and PD 0 at the Tfap2d genomic locus ATAC peaks from heart (bottom tract) samples depict that the mechanism is forebrain specific. The blue boxes highlight putative enhancers (E) harboring predicted binding sites for SOX11, spanning from E1 to E6, with ChIP-seq confirmation of binding specifically within E6. e) Validation of the anti-SOX11 antibody involved examining coronal sections of PDC 15.5 brains. In WT control brains, SOX11 immunostaining (red) was observed, while in the SOX11-cKO, expression from all GFP+ excitatory neurons was lost (indicated by open arrowheads). Filled arrowheads point to SOX11 immunopositive nuclei within the cortical plate and in SVZ. ATAC; Assay for Transposase-Accessible Chromatin. SVZ, subventricular zone; VZ, ventricular zone; WT, wildtype.

SOX4 and SOX11 regulate Tfap2d expression in VLp

To investigate downstream genes regulated by SOX4 and SOX11, we performed bulk tissue RNA-sequencing (RNA-seq) analysis on pooled cerebral cortex and amygdala tissue obtained from PD0 in Sox4/Sox11-cdKO, Sox4-cKO and Sox11-cKO mice and control littermates. We identified 958 and 659 genes that were uniquely upregulated and downregulated, respectively, in the Sox4/Sox11-cdKO brains (Fig. 1b and Supplementary Tables 1 and 2). Because neuroinflammation-associated genes were upregulated in the Sox4/Sox11-cdKO brains, we next assessed whether deletion of Sox4 or Sox11, or both led to increased microglia and astroglia invasion (Extended Data Fig. 2b and Supplementary Table 1). Increased labelling of the glial markers IBA1 and GFAP by immunofluorescence confirmed microglia and astroglia invasion, respectively (Extended Data Fig. 2c). In addition, TUNEL staining provided evidence for DNA fragmentation, suggesting cell damage (Extended Data Fig. 2c). These data corroborate previously reported functions of SOX4 and SOX11 in neuron differentiation and survival20,21.

Because the severe defects in the VLp were seen only in the Sox4/Sox11-cdKO mice, we focused on downregulated genes (Fig. 1b and Supplementary Table 2). Among these, many have been previously shown23–27 to be enriched in BLC, CLA or PIR, including Cyp26b1, Glipr2, Fst and Nr4a2 (Fig. 1c and Extended Data Fig. 2a). The most downregulated gene in Sox4/Sox11-cdKO mice encodes the transcription factor TFAP2D (also known as AP-2 delta) (Fig. 1c and Supplementary Table 2), which was previously shown to be enriched in human and non-human primate amygdala23,24,28,29. Although TFAP2D has previously been implicated in development of dorsal midbrain25 and retina26, its role in development of amygdala or other VLp structures has not been studied. In situ hybridization and transcriptomic analysis revealed that Tfap2d exhibits increased expression in developing excitatory neurons in the BLC and neighbouring VLp structures, such as the PIR, CLA, EP anterior olfactory nucleus and anterior insula (Figs. 1d and 2e, Extended Data Fig. 5c and Supplementary Table 2). In accordance with the results of the RNA-seq analysis, expression of Tfap2d was almost absent in these structures of Sox4/Sox11-cdKO mice when assessed at PD0 (Fig. 1d).

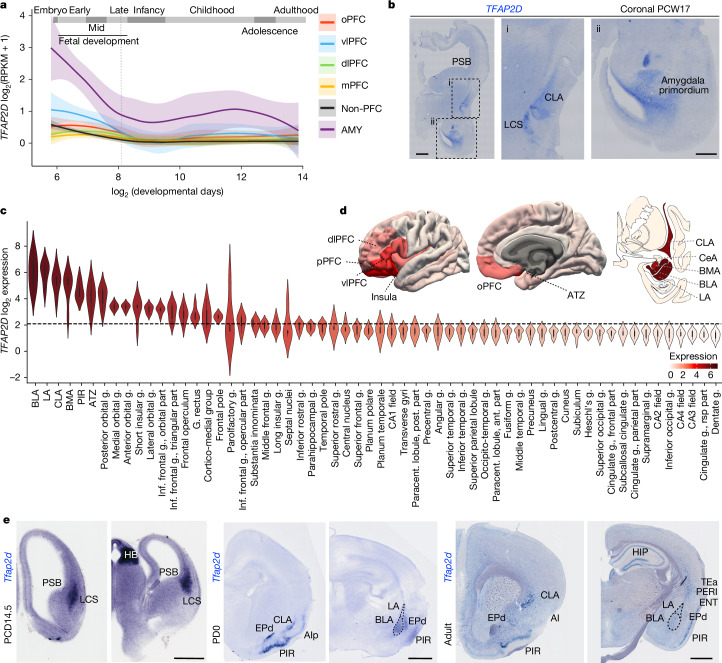

Fig. 2. Conserved expression pattern of TFAP2D in human and mouse brain.

a, Expression of TFAP2D across developmental ages in the human amygdala (AMY), orbital PFC (oPFC), ventral PFC (vPFC), dorsolateral PFC (dlPFC), medial PFC (mPFC) and non-PFC28,29. Data are mean ± s.e.m. b, Coronal section of a human brain at PCW17, showing the expression of TFAP2D in the LCS, CLA and amygdala primordium. Scale bars, 2 mm (left), 1 mm (right). c, TFAP2D expression pattern across frontal cortical regions, VLp and subcortical regions in adult human brain as derived from publicly available microarray data31. The dashed line represents the mean of TFAP2D expression across all regions represented here. Ant., anterior; g., gyrus; inf., inferior; paracent., paracentral; post., posterior; rsp., retrospinal. d, Human brain images showing TFAP2D expression gradients across the adult brain. Correspondence between the Desikan–Killiany atlas and the Allen Brain Atlas probes51 was used to visualize TFAP2D expression. Subcortical regions were visualized using data from http://atlas.brain-map.org. ATZ, amygdalohippocampal transition zone; CEA, central nucleus of the amygdala. e, In situ hybridization for Tfap2d in coronal sections of wild-type mice at PCD14.5, PD0 and in adult. Scale bars, 200 μm. AIp, AI, posterior part; ENTI, entorhinal cortex; HB, habenula; HIP, hippocampus; PERI, perirhinal cortex; pPFC, polar PFC.

Extended Data Fig. 5. Expression of Tfap2d in the macaque and mouse brain.

a) Plot of TFAP2D expression across developmental ages in the macaque AMY, OFC, DFC, VFC, MFC and nonPFC areas within the forebrain26,27. Mean ± s.e.m depicted. b) Coronal section of a macaque brain at PCD 105 showing TFAP2D expression in the LCS, and amygdala primordium detected by in situ hybridization. c) Representative serial coronal sections showing Tfap2d expression within wildtype mouse PCD 14.5, PD 0 and adult brains detected by in situ hybridization. At PCD 14.5, Tfap2d expression is restricted to the LCS and Hb primordium. At PD 0 and in adults Tfap2d expression is seen in the BLC, CLA, EPd, EPv PIR, and SC. In adults, deep layer neurons in the AUD, GUS, and TEA show sporadic expression of Tfap2d. Representative images from this panel are used in Fig. 2e. d-e) UMAP showing the subclasses of glutamatergic neurons in the adult mouse cerebrum (left) and the expression of Tfap2d within the subclasses representing the BLC, PIR, AON, CLA37. f) Coronal sections of the E17 chicken brain showing Tfap2d (red) expression in the nidopallium and arcopallial amygdala detected by RNAscope. AA, arcopallium amygdala; AON, anterior olfactory nucleus; AUD, auditory cortex; EPv, EP, ventral part; GUS, gustatory cortex; H, hyperpallium; LGE, lateral ganglionic eminence; M, mesopallium; MGE, medial ganglionic eminence; N, nidopallium; SC, superior colliculus; Se, septum; Str, striatum.

We investigated SOX4 and SOX11 regulation of Tfap2d by integrating chromatin immunoprecipitation with sequencing (ChIP–seq) for H3K27ac27 and assay for transposase-accessible chromatin using sequencing (ATAC-seq)30 from the mouse forebrain (post-conception day (PCD) 11.5 to PD0), with predicted SOX-binding motifs and SOX11 ChIP–seq data21 (Extended Data Fig. 2d). Using this analysis, we identified six putative enhancers (E1–E6) associated with Tfap2d expression, which also showed increased accessibility starting at PCD13.5, which coincides with the migration of immature amygdalar excitatory neurons13,18. To validate these in silico findings, we conducted chromatin immunoprecipitation followed by real-time PCR (rtPCR) using a SOX11 antibody that we validated in Sox11-cKO brains (Extended Data Fig. 2e), and crosslinked chromatin from PCD16.5 wild-type and Sox11-cKO cortices and amygdalae. We could not identify a suitable SOX4 antibody for immunohistochemistry or ChIP assays. Our ChIP results revealed strong binding of SOX11 and RNA polymerase II (Pol II) to E2 (Fig. 1e), indicating its active involvement in SOX11-dependent Tfap2d transcription. Further, by performing luciferase reporter assays for all six enhancers (E1–E6) in Neuro2a cells, we show that SOX4 and SOX11 expression increased the luciferase activity of the E2 enhancer, whereas mutating putative SOX4 and SOX11 sites markedly reduced this activity (Fig. 1f). These results strongly suggest that SOX11 and SOX4 directly regulate Tfap2d via the E2 enhancer, highlighting their pivotal role in this regulatory mechanism. Consistent with these findings, Sox4, Sox11 and Tfap2d are co-expressed in BLC excitatory neurons (Extended Data Figs. 4c,d, 7a–d and 8a–d). Collectively, these findings indicate that SOX11 directly regulates the expression of Tfap2d in the VLp.

Extended Data Fig. 4. Expression of TFAP2D in the human brain.

a) TFAP2D expression pattern across frontal cortical regions, ventrolateral cortical structures, and subcortical regions in prenatal human brain35. The dotted line represents the mean of TFAP2D expression across all the regions represented here. X-axis depicts the regions and y-axis depicts the log 2 value for the expression pattern. b) Barplot showing the expression of TFAP2D in the claustrum, amygdala, striatum and neocortex detected by dd-PCR in adult human tissue (n = 3). c) Violin plot generated using publicly snRNA-seq available data36 showing TFAP2D, SOX4, and SOX11 expression in the ExNs (Excitatory neurons) of the human amygdala with highest enrichment in the Excit_B class. y-axis depict the log2 expression values and x-axis depicts the different classes of neurons within the human amygdala. d) Dot plot showing the percentage of cells that express the top 30 genes within the Excit_B class. Color represents the average expression level and size of the circle represents the percentage of cells. For detailed statistics, please see Supplementary Table 13.

Extended Data Fig. 7. Profiling of Sox4, Sox11 and Tfap2d expression in BLC excitatory neurons subclusters across mammalian and non-mammalian species.

a-d) Dot plot annotations showing the top 10 genes marker genes expressed by the ExN clusters Sox11, Sox4 and Tfap2d within human, macaque, mouse and chicken38.

Extended Data Fig. 8. Conservation analysis of Tfap2d-associated enhancers across species.

a) Heatmap illustrating the pairwise alignment distances between various species of vertebrates for the six putative enhancers within the Tfap2d locus. X indicates the absence of orthologous sequence. b) Line graph for three SOX11 binding sites within the Tfap2d-E2 enhancer depicting their conservation across species using MULTIZ alignment. c) Line graph displaying the mouse E2 enhancer and the putative human E2 enhancer, obtained through lift-over of the human genome (hg38). Predictions for SOX4 and SOX11 binding sites are included, based on JASPAR 2022 and 2024 release.

To determine the cause of PD0 VLp defects, we analysed Sox4/Sox11-cdKO mice and littermate controls at PCD16.5. Co-deletion of Sox4 and Sox11 induced premature apoptosis along LCS and VLp, as illustrated by increased numbers of cells containing cleaved caspase-3 (CC3), a marker of dying cells, and ADGRE1 (also known as F4-80), which labels infiltration and activation of microglia, compared with littermate wild-type controls, Sox4-cKO or Sox11-cKO mice (Extended Data Fig. 3a). To investigate whether altered neuronal migration contributed to these defects, we performed RNAscope with probes targeting Tbr1, Neurog2 and Sema5a mRNAs, which are markers that have been shown to label LCS, BLC and PIR neurons11. In Sox4/Sox11-cdKO mice, we observed a significant reduction, but not misrouting, of neurons migrating along the LCS, BLC and PIR primordia that were labelled for Tbr1, Neurog2 and Sema5a as well as BHLHE22 (Extended Data Fig. 3b–e). Together, these data suggest that the disruption in the VLp in Sox4/Sox11-cdKO mice is driven by prenatal apoptosis rather than neuronal misrouting.

Extended Data Fig. 3. Loss of SOX4 and SOX11 leads to extensive premature apoptosis in the LCS and VLp.

a) Quantifications of the cleaved caspase3 (CC3)- and ADGRE1-immunopositive cells compared to the DAPI-positive cells in the LCS, BLC and PIR of the WT controls, Sox4-cKO, Sox11-cKO and Sox4; Sox11-cdKO. The data is normalized to the WT controls. Two-way ANOVA with multiple comparisons and Tukey’s correction was applied. Mean ± s.e.m. depicted. ****, **, * represents P < 0.0001, 0.01, 0.05 respectively. n = 3/genotype. b) Coronal sections from the ventrolateral cortical region of WT controls, Sox4-cKO, Sox11-cKO and Sox4; Sox11-cdKO mice brains at PCD 16.5. The LCS, BLC and PIR are depicted using RNAscope for Tbr1, Ngn2, and Sema5a. Filled arrowheads point to normal phenotypes and open arrowheads point to defective phenotypes in the knockouts. c) Quantifications of the expression of Tbr1, Ngn2 and Sema5a over DAPI in the LCS, BLC and PIR. Two-way ANOVA with multiple comparisons and Tukey’s correction was applied. Mean ± s.e.m. depicted. ***, **,* represents P value < 0.001, 0.01, 0.05, respectively. n = 3/genotype. d) Coronal sections from the ventrolateral cortical region of WT controls, Sox4-cKO, Sox11-cKO and Sox4; Sox11-cdKO mice brains at PCD 16.5 stained for BHLHE22. Filled arrowheads point to normal phenotype and open arrowhead point to defective phenotypes in the knockouts. e) Quantifications of the expression of BHLHE22 over DAPI in the BLC and PIR. Two-way ANOVA with multiple comparisons and Tukey’s correction was applied. Mean ± s.e.m. depicted. **, * represents P value < 0.01 and 0.05, respectively. n = 3/genotype. For detailed statistics, please see Supplementary Table 12.

Conserved expression of Tfap2d in VLp excitatory neurons

Our previous transcriptomic analyses23,24,28,29 revealed an enrichment of TFAP2D in the human and non-human primate prenatal amygdala that declines steadily until infancy and persists at lower levels thereafter (Fig. 2a). We corroborated TFAP2D expression in the human brain at post-conception week (PCW) 17, specifically in the LCS, as well as in the claustro-amygdalar primordia (Fig. 2b). Furthermore, our analysis of microarray datasets from midfetal and adult human brains31,32 revealed a gradient of TFAP2D expression, with higher levels observed in BLA, LA, CLA, BMA and PIR, followed by the peripalaeocortical subdivisions of the frontal, insular and temporal cortex, and the orbito-lateral transitional neocortical PFC areas (Fig. 2c,d and Extended Data Fig. 4a). We further confirmed the TFAP2D expression pattern in the amygdala and CLA by digital droplet PCR (Extended Data Fig. 4b). Using publicly available human amygdala single-nucleus RNA-seq (snRNA-seq) data33, we demonstrated that TFAP2D is highly expressed in the amygdala excitatory neurons subclass that also co-expresses SOX4, SOX11, TBR1, NEUROD2 and SLC17A6 (Extended Data Fig. 4c,d).

RNA-seq datasets sourced from developing and adult macaque and chimpanzee brain regions23,24 showed pronounced prenatal expression of TFAP2D in the amygdala, which progressively diminishes with advancing age (Extended Data Fig. 5a), similar to the human data. To ascertain the conservation of TFAP2D expression patterns in the developing VLp across species, we conducted in situ hybridization experiments in rhesus macaques and mice. We observed TFAP2D expression in the macaque LCS and in the amygdala primordium at PCD105 (Extended Data Fig. 5b). In mouse, we performed in situ hybridization at PCD14.5, PD0 and PD60. At PCD14.5, we observed Tfap2d in neurons migrating along the LCS and in the amygdala primordium (Fig. 2e and Extended Data Fig. 5c). Notably, Tfap2d expression was not observed in the proliferative zones at the PSB (Fig. 2e and Extended Data Fig. 5b,c). This finding indicates that Tfap2d expression initiates in immature post-mitotic excitatory neurons migrating along the LCS. At both PD0 and PD60, Tfap2d is expressed in the BLC, CLA and anterior insula (Fig. 2e and Extended Data Fig. 5c), resembling humans (Fig. 2c), as well as in the EP and PIR (Fig. 2e and Extended Data Fig. 5c). At PD60, we also observed a sporadic expression pattern of Tfap2d in the deep layers of the anterior insula, insular gustatory (GUS), temporal association (TEa) and auditory (AUD) cortex (Extended Data Fig. 5c). We further corroborated this expression pattern in mouse using a publicly available cerebrum snRNA-seq dataset34 (Extended Data Fig. 5d,e). Using RNAscope, we detected Tfap2d expression in the nidopallium and mesopallium of chicken forebrain on embryonic day (E) 17, including in the PIR and arcopallial amygdala (Extended Data Fig. 5f). These regions are homologues of the mammalian VLp structures, including BLC, CLA and PIR. This evidence indicates that Tfap2d expression is highly conserved across a broad spectrum of species, including humans, non-human primates, mice and chickens.

Further, our analysis of publicly available amygdala snRNA-seq datasets from human, macaque, mouse and chicken35 reveal increased and consistent expression of Tfap2d in the BLC and major excitatory neuron subclasses across all profiled species (Extended Data Figs. 6a–d and 7a–d). In human, TFAP2D is most highly expressed in LAMP5 -expressing excitatory neuron clusters (Extended Data Figs. 6a and 7a), which were dominant in the human BLC35. Additionally, we observed SOX4, SOX11 and TFAP2D expression in the paralaminar nucleus in humans (Extended Data Fig. 6a), which, as previously shown, harbours immature SOX11-positive excitatory neurons in adulthood17. In mice, the Rspo excitatory neuron subclass exhibited the highest expression of Tfap2d and Sox11 (Extended Data Figs. 6c and 7c), a cell type that is known to regulate anxiety-like behaviours in mice36. The similarity of the TFAP2D expression pattern across human, macaque, mouse and chicken suggests that there may be a conserved TFAP2D-dependent regulatory network for VLp excitatory neurons specification. In contrast to the conserved co-expression of Sox4, Sox11 and Tfap2d expression across species, the SOX4 and SOX11-regulated E2 enhancer, which showed activity in mice, is found exclusively in placental mammals (Extended Data Fig. 8a). The SOX4 and SOX11 binding sites in E2 are partially conserved in placental mammals (Extended Data Fig. 8b). Furthermore, the orthologous human E2 enhancer lacks the putative SOX4 and SOX11 binding sites from mice, but exhibits additional ones as predicted by JASPAR (Extended Data Fig. 8c). Yet, the conserved co-expression of Tfap2d with Sox11 or Sox4 in BLC excitatory neurons across species hints at potential evolutionary divergence while maintaining a parallel mechanism for Tfap2d regulation by SOX4 and SOX11 across species. Together, these results, which corroborate previous findings37, suggest that despite changes in SOX4 and SOX11 binding sites across species, Tfap2d regulation by SOX4 and SOX11 may be maintained through regulatory mechanisms that are independent of strict DNA sequence constraints.

Extended Data Fig. 6. Conserved Tfap2d expression in BLC excitatory neurons across mammalian and non-mammalian Species.

a-d) Dot plot annotations showing the expression of Sox11, Sox4 and Tfap2d within 1) the major amygdala cell types in all species, 2) the amygdala nuclei in human, macaque, mouse (space annotations), and 3) ExN clusters within the BLC in human, macaque, mouse and within the caudal dorso-ventral ridge (DVR) of chicken, region homologous to mammalian amygdala38. In all species, Tfap2d exhibited high expression in ExN within the amygdala. IA, intercalated cell masses; InN, Inhibitory neurons; MEA, medial nucleus of the amygdala; OPC, oligodendrocyte progenitor cells; PL, paralaminar nucleus of the amygdala.

Tfap2d regulates BLA and LA development

To examine the effect of Tfap2d deletion on VLp development, we analysed mice with a targeted disruption of Tfap2d. We first investigated Tfap2d lacZ mice, in which a β-galactosidase–neomycin cassette, interrupting exon 1 of the Tfap2d gene, abolishes Tfap2d expression30 (Extended Data Fig. 9a). Additionally, given the previously reported Tfap2d expression and function in the superior colliculus30, we also developed Tfap2d-floxed mice (Extended Data Fig. 10a,b and Supplementary Table 3). We crossed these mice with Neurod6-cre;CAT-Gfp mice to delete Tfap2d in post-mitotic cerebral excitatory neurons, yielding conditional mutant groups (Tfap2d-cKO, Tfap2d conditional heterozygous (cHet) and wild-type control) that express a GFP reporter in cerebral excitatory neurons. In Tfap2d-knockout (KO) and Tfap2d-cKO mice, Tfap2d expression was absent in VLp, including in the BLC, PIR, CLA and EP, however, expression in the superior colliculus remained unaffected in the Tfap2d-cKO mice (Fig. 3a and Extended Data Fig. 10c). Mice of all these genotypes survived to adulthood.

Extended Data Fig. 9. Whole-body knockout of Tfap2d results in BLC deficits.

a) Schematic depicting the Tfap2d WT allele and the KO allele with the insertion of LacZ cassette within the exon (Ex) 130. b) Coronal sections of the ventrolateral pallial regions of the WT control, Tfap2d-Het and Tfap2d-KO brains showing the expression of Lmo3, Etv1 and Mef2c by in situ hybridizations and NR4A2 by immunostaining at PD 4. Reduction in the size of BLC is seen by Lmo3, the most affected region is the Etv1 labelled BLA. c) Nissl staining of the coronal sections of the adult WT control, Tfap2d-Het and Tfap2d-KO brains. d) Coronal sections of the ventrolateral cortical regions of the adult WT control, Tfap2d-Het and Tfap2d-KO brains showing the AChE staining used to label the BLA. e) Stereological measurements of the volume of LA and BLA in the adult WT control, Tfap2d-Het and Tfap2d-KO brains. Mean ± s.e.m. depicted. Two-way ANOVA with Tukey’s correction was applied. ** and * represents p values < 0.01, <0.05 respectively. n = 5 (WT), 6 (Het), 7 (KO). For detailed statistics, please see Supplementary Table 14.

Extended Data Fig. 10. Development of floxed Tfap2d allele for conditional post-mitotic deletion of Tfap2d in cerebral excitatory neurons that leads to BLC formation deficits.

a) Schematic depicting the Tfap2d wildtype allele (above) and the floxed allele (below) carrying the insertion of flox (fl) cassettes within intron (In) 1 and In 3 of the Tfap2d locus. The regions amplified by PCR using genotyping primers are indicated. b) Genotyping agarose gel showing the sizes of the amplified PCR products that can distinguish the fl/fl, fl/+ and +/+ genotypes. c) Serial coronal sections of WT control, Tfap2d-cHet and Tfap2d-cKO brains at PD 0 showing reduced expression of Tfap2d in the ventrolateral pallial structures (CLA, EPd, PIR, BLC) but not in the midbrain (SC, superior colliculus) of cKO mice. Representative images from this panel are also used in Fig. 3a. d) Serial sections of the WT control, Tfap2d-cHet and Tfap2d-cKO brains at PD 0 depicting their gross morphology via visualization of GFP expression driven by the Neurod6 (Nex1)-Cre driver. e) Immunostaining showing the expression of TBR1 and SATB1 in the WT control, Tfap2d-cHet and Tfap2d-cKO brains at PD 0, highlighting the deficits seen in the BLC. f) Immunostaining showing the expression of NR4A2 in the CLA of WT control, Tfap2d-cHet and Tfap2d-cKO brains at PD 0. Filled arrows indicate normal morphology whereas open arrows indicated altered BLC structure.

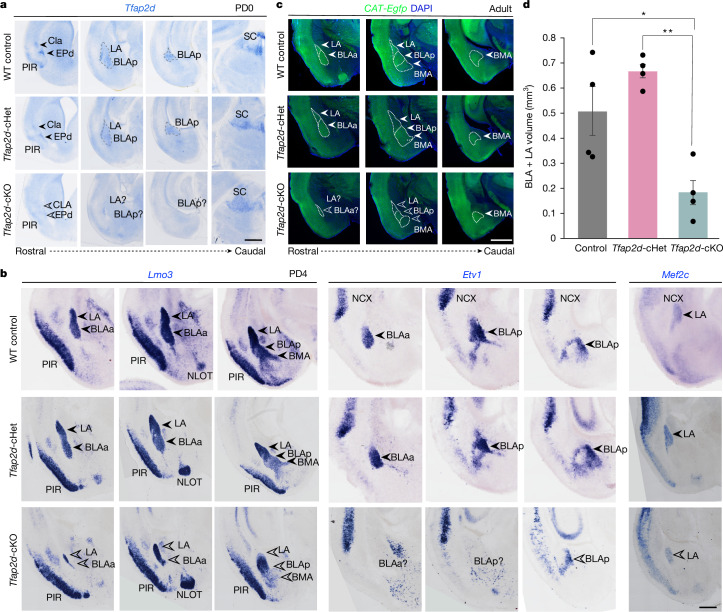

Fig. 3. Post-mitotic deletion of Tfap2d in cerebral excitatory neurons leads to reduced BLC.

a, Coronal sections of wild-type control Tfap2d-cHet and Tfap2d-cKO mice, demonstrating that the specificity of deletion of Tfap2d expression is reduced in the VLp (encompassing CLA, EPd, PIR and BLC) but not in the SC in the midbrain. Scale bar, 500 μm. BLAp, BLA, posterior part; SC, superior colliculus. b, In situ hybridization for Lmo3, Etv1 and Mef2c in coronal sections of wild-type control, Tfap2d-cHet and Tfap2d-cKO VLp at PD4. Scale bar, 500 μm. NCX, neocortex; NLOT, nucleus of lateral olfactory tract. c, Coronal sections of adult wild-type control, Tfap2d-cHet and Tfap2d-cKO VLp showing the cytoarchitecture of the brain in adults. Scale bar, 1 mm. BLAa, BLA, anterior part. In a–c, white and black filled arrowheads highlight normal Tfap2d expression and open arrowheads highlight loss of Tfap2d expression. d, Stereological measurements of the combined volume of BLA and LA in adult wild-type control, Tfap2d-cHet and Tfap2d-cKO brains. Data are mean ± s.e.m. Two-way ANOVA with Tukey’s correction. **P = 0.0022, *P = 0.024; n = 4 per genotype. Detailed statistics are presented in Supplementary Table 7.

To assess whether VLp development is altered following Tfap2d loss, we conducted a comprehensive analysis of perinatal mouse brains. No notable defects were observed in neocortical or archicortical structures, including in GFP-labelled long-range subcerebral and interhemispheric projections in the Tfap2d-cKO mice (Extended Data Fig. 10d), aligning with the restricted expression pattern of Tfap2d to claustro-amygdalar and palaeocortical excitatory neurons. However, Nissl and acetylcholinesterase staining in Tfap2d-KO and GFP expression in Tfap2d-cKO indicated a marked reduction in BLC size (Fig. 3c,d and Extended Data Fig. 9c–e). Further, immunostaining for TBR1 and SATB1 (Extended Data Fig. 10e) and in situ hybridization for Lmo3, Etv1 and Mef2c (Fig. 3b and Extended Data Fig. 9b), confirmed a near-complete loss of BLA, partial loss of LA, but no obvious loss of BMA in Tfap2d-KO and Tfap2d-cKO mice compared with their respective heterozygous and wild-type controls. Immunostaining for NR4A2, which labels CLA excitatory neurons, showed no noticeable differences in CLA across genotypes (Extended Data Figs. 9b and 10f). In adults, no appreciable anatomical abnormalities were observed in other VLp structures in Tfap2d-cKO or Tfap2d-KO mice (Fig. 3c and Extended Data Fig. 10c,d). These findings indicate that Tfap2d has an essential cell-autonomous role in the post-mitotic development of LA and BLA excitatory neurons.

To determine the origin of the developmental deficits in Tfap2d-cKO BLA, we conducted a detailed analysis of cell death and migration defects, similar to the analysis performed with Sox4/Sox11-cdKO mice. Similar to Sox4/Sox11-cdKO mice, Tfap2d-cKO brains showed increased cell death and activated microglia compared with littermate wild-type and Tfap2d-cHet brains (Extended Data Fig. 11a). This increased cell death resulted in fewer neurons migrating along the LCS and in BLC and PIR, as labelled by BHLHE22, Tbr1, Neurog2 and Sema5a (Extended Data Fig. 11b–d,g). However, unlike Sox4/Sox11-cdKO mice, Tfap2d-cKO mice also exhibited migration defects, specifically in the ventral LCS. A small stream of Ngn2-positive excitatory neurons (Ngn2 typically labels LCS and BLC neurons), which also express Tbr1, reached the ventromedial PIR (Extended Data Fig. 11b), unlike in littermate wild-type controls and Tfap2d-cHet mice. Furthermore, BHLHE22 staining revealed increased clustering at the ventromedial PIR in Tfap2d-cKO mice compared with littermate controls (Extended Data Fig. 11d–g). These findings suggest that Tfap2d deletion results in premature apoptosis of some LCS, BLC and PIR excitatory neurons. Additionally, some excitatory neurons exhibited migration defects that rather than entering BLC primordia, continued to migrate ventrally towards the PIR. These early embryonic migration defects may also cause potential alterations in the VLp connections and functioning.

Extended Data Fig. 11. Loss of Tfap2d leads to premature apoptosis in the LCS and VLp downstream of Sox4 and Sox11.

a) Quantifications of the CC3-positive and ADGRE1-positive cells over the DAPI-positive cells detected in the LCS, BLC and PIR of the WT controls, Tfap2d-cHET, and Tfap2d-cKO. The data is normalized to the WT controls. Two-way ANOVA with multiple comparisons and Tukey’s correction was applied. Mean ± s.e.m. depicted. **, * represents P < 0.01, 0.05. n = 4 (WT), 3(cHET), 6(cKO) for CC3 and 4(WT), 3(cHET) and 5(cKO) for ADGRE1. b) Coronal sections from the ventrolateral cortical region of WT controls, Tfap2d-cHET, and Tfap2d-cKO mice brains at PCD 16.5. The LCS, BLC and PIR are depicted using RNAscope for Tbr1, Ngn2, and Sema5a. Filled arrowheads point to normal phenotype and open arrowhead point to defective phenotypes in the knockouts. c) Quantifications of the expression of Tbr1, Ngn2 and Sema5a over DAPI in the LCS, BLC and PIR. Two-way ANOVA with multiple comparisons and Tukey’s correction was applied. Mean ± s.e.m. depicted. **, * represents P < 0.01, 0.05. n = 3 (WT), 4(cHET), 4(cKO) for Tbr1 and 3(WT), 4(cHET) and 3(cKO) for Sema5a and Ngn2. d) Coronal sections from WT controls, Tfap2d-cHET, and Tfap2d-cKO mice brains at PCD 16.5 stained for BHLHE22. Filled arrowheads point to normal phenotype and open arrowhead point to defective phenotypes in the knockouts. e) Quantifications of the BHLHE22 intensity per bin normalized to total intensity with PIR. Two-way ANOVA with multiple comparisons and Tukey’s correction was applied. Mean ± s.e.m. depicted. Pinteraction < 0.0001 n = 8 (WT), 6(cHET), 10(cKO). f) Quantifications of the BHLHE22 intensity per 50 bins normalized to total intensity with PIR. Two-way ANOVA with multiple comparisons and Tukey’s correction was applied. Mean ± s.e.m. depicted. ***, ** represents P value < 0.001, 0.01. n = 8 (WT), 6(cHET), 10(cKO). g) Quantifications of the BHLHE22 ExNs over the DAPI-positive cells detected in the BLC and PIR of the WT controls, Tfap2d-cHET, and Tfap2d-cKO. Two-way ANOVA with multiple comparisons and Tukey’s correction was applied. Mean ± s.e.m. depicted. **, * represents P < 0.01, 0.05. n = 4 (WT), 3 (cHET), 5 (cKO). h) Coronal sections from Sox4 fl/fl; Sox11 fl/fl mice brains at PCD 16.5 stained for GFP, CC3 and ADGRE1 that were injected with p Neurod1-Cre and pCalnl-Gfp (negative control) or pCalnl-Tfap2d-ires-Gfp (Tfap2d rescue) at PCD 12.5 by in utero electroporation. Open arrowheads point to CC3 positive dying cells whereas filled arrowheads point to the GFP positive cells migrating along the LCS and reaching BLC. Double empty arrowheads point to CC3 and GFP positive dying cells in the adjacent cortex i) Quantifications of the CC3 positive and ADGRE1 positive cells over the GFP positive cells detected in the LCS, BLC, PIR and ventrolateral cortical regions (AUD/GUS + TEA). The data is normalized to the GFP positive cells seen in the negative controls. Multiple unpaired two-tailed t-test was applied. Mean ± s.e.m. depicted. **, * represents P < 0.01, 0.05. n = 3 (negative control), n = 4 (Tfap2d rescue). For detailed statistics, please see Supplementary Table 15.

The predisposition of Sox4/Sox11-cdKO cells to undergo apoptosis (Extended Data Fig. 3a) may be due to disruption of Tfap2d expression. To access this, we selectively deleted Sox4 and Sox11 expression while concurrently rescuing Tfap2d in a subset of post-mitotic excitatory neurons originating at the PSB, which migrate to the BLC, PIR and neighbouring cortical regions (AUD/GUS and TEA) by performing in utero electroporation at PCD12.5. As negative controls, we performed similar Sox4 and Sox11 deletion with no rescue (Extended Data Fig. 11h). Analysis at PCD16.5, showed a markedly reduced number of CC3-positive dying cells in the LCS, BLC and PIR, but not in neighbouring cortical regions, of Tfap2d-rescued brains compared with negative controls (Extended Data Fig. 11h,i). GFP-negative cells also underwent apoptosis, probably owing to the loss of GFP expression in dying cells or cell-extrinsic factors. These findings suggest that in LCS, BLC and PIR, Tfap2d prevents Sox4 and Sox11 deletion-associated apoptosis. However, in the neocortex, Sox4 and Sox11 operate through Tfap2d-independent pathways.

Tfap2d loss or haploinsufficiency disrupts BLC–PFC connections

BLC excitatory neurons form extensive long-range connections to multiple brain regions, including the PFC, thalamus (TH) and hippocampus38, which encode salient cues from the environment1–3,5. Prompted by the observed reduction of BLC in Tfap2d-deficient mice, we investigated the influence of Tfap2d expression on long-range axonal projections from BLC. Using diffusion tensor imaging (DTI) on control, Tfap2d-heterozygous (Het) and Tfap2d-KO brains, we found a marked impairment of BLC–PFC connectivity in Tfap2d-KO mice (Fig. 4a). Notably, despite a significant reduction in BLC–PFC connectivity in Tfap2d-Het brains compared with wild-type controls, these brains exhibited significantly increased connectivity relative to Tfap2d-KO brains, indicating a dosage-dependent, intermediate effect of Tfap2d haploinsufficiency on BLC–PFC connections (Fig. 4c). However, we observed no significant differences in BLC–TH, BLC–hippocampus, or contralateral cortical–cortical connections in the somatosensory cortex, primary motor cortex and PFC across the genotypes (Fig. 4a–c). This suggests a targeted effect of Tfap2d deficiency on specific BLC-related neural pathways.

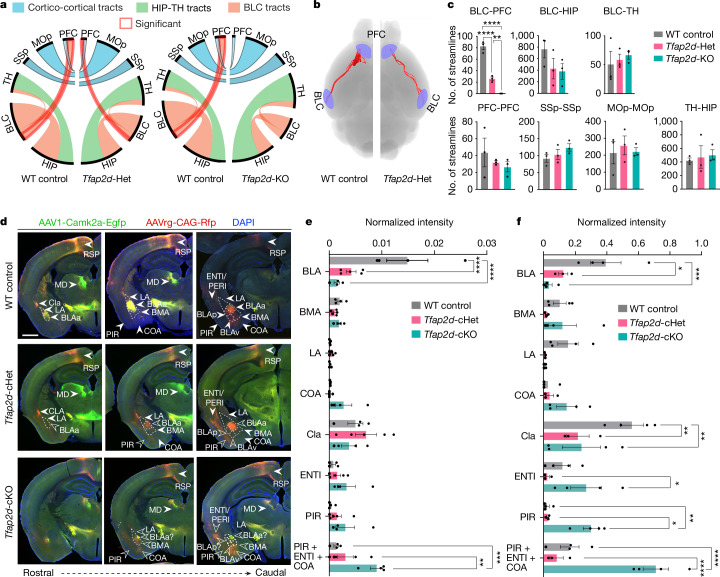

Fig. 4. Tfap2d loss or haploinsufficiency alters connections between BLC and PFC.

a, Streamlines generated as a connectivity measurement between the BLC and mPFC, HIP and TH at PD120–PD180 in Tfap2d-KO mice using DTI (n = 3 per genotype). MOp, primary motor cortex; SSp, primary somatosensory cortex. b, Visualization of streams connecting the BLC and mPFC in wild-type control and Tfap2d-Het brains. c, Number of streamlines between BLC and mPFC, HIP and TH and between contralateral cortical areas in wild-type control, Tfap2d-Het and Tfap2d-KO mice. One-way ANOVA with Bonferroni’s multiple comparisons test. ****P < 0.0001, **P = 0.0074; n = 3 per genotype. d, Representative images of wild-type control, Tfap2d-cHet and Tfap2d-cKO brains with efferent and afferent projections traced from the mPFC using AAV1-Camk2a-Egfp (anterograde) and AAVrg-CAG-Rfp (retrograde) at PD90. Open arrowheads indicate reduced or misdirected projections from and to the mPFC; filled arrowheads indicate typical projection pattern from mPFC. Scale bar, 500 μm. BLAv, BLA, ventral; MD, mediodorsal nucleus of the TH; RSP, retrosplenial cortex. e,f, Normalized intensity of retrograde tracings (e; AAVrg-CAG-Rfp labelling in d) and anterograde tracings (f; AAV1-Camk2a-Egfp labelling in d) in VLp, including BLC, CLA, COA, PIR and ENTI/PERI in wild-type control, Tfap2d-cKO and Tfap2d-cHet mice. Data are mean ± s.e.m. Two-way ANOVA with Tukey’s correction. e, PIR + ENTI + COA, Tfap2d-cHet versus Tfap2d-cKO: **P = 0.0028. ***P = 0.0002; ****P < 0.0001. n = 4 (wild type), 5 (cHet) and 4 (cKO) mice. f, BLA, wild type versus Tfap2d-cHet: *P = 0.0129; ENTI, Tfap2d-cHet versus Tfap2d-cKO: *P = 0.025; PIR, Tfap2d-cHet versus Tfap2d-cKO: *P = 0.0115; Cla, wild type versus Tfap2d-cHet: **P = 0.0012; Cla, wild type versus Tfap2d-cKO: **P = 0.0011; PIR, wild type versus Tfap2d-cHet: **P = 0.0051. ***P = 0.0002; ****P < 0.0001. n = 4 (wild type), 3 (cHet) and 4 (cKO). Detailed statistics are presented in Supplementary Table 8.

To further corroborate the deficits in BLC–PFC connectivity observed by DTI, we used adeno-associated virus (AAV) based tract tracing in Tfap2d-deficient mice. Given the significant reduction in BLC size in Tfap2d-deficient mice, we introduced both anterograde and retrograde AAV tracers into the medial PFC (mPFC), broadly targeting both the prelimbic (PL) and infralimbic (ILA) areas, regions that showed significant alterations in BLC connectivity in the DTI analysis. Consistent with the DTI observations, all genotypes with reduced or absent Tfap2d expression (Tfap2d-cHet, Tfap2d-HET, Tfap2d-cKO and Tfap2d-KO) exhibited a significant decrease in BLA–mPFC and mPFC–BLA projections compared with wild-type controls (Fig. 4d–f and Extended Data Fig. 12a–c). In addition to the reduced BLA–mPFC connections, we observed a dispersed projection pattern from the cortical amygdalar area (COA), PIR and perirhinal cortex to the PFC in Tfap2d-KO and Tfap2d-cKO mice compared with wild-type counterparts (Fig. 4d–f and Extended Data Fig. 12a–c). This shift in projection patterns is probably due to the migration defects in prenatal excitatory neurons causing their aberrant accumulation in ventral PIR (Extended Data Fig. 11b–g) in Tfap2d-deficient mice. In addition to a general decrease in BLA–PFC connectivity, Tfap2d-Het and Tfap2d-cHet mice also exhibited individual variations in atypical projection patterns involving the PIR, COA and PFC. Collectively, these findings underscore that the absence of one or both Tfap2d alleles results in altered BLA–mPFC connections, highlighting the critical role of Tfap2d gene dosage in maintaining proper neural circuitry.

Extended Data Fig. 12. Tfap2d loss or haploinsufficiency impairs BLC-mPFC connectivity.

a) Serial coronal sections of WT control, Tfap2d-Het and Tfap2d-KO adult brains whose efferent and afferent projections from the mPFC were traced using AAV1-Camk2a-Egfp (green; anterograde) and AAVrg-Cag-Rfp (red; retrograde), respectively. b-c) Bar graphs depicting the normalized intensity of the number of cells carrying AAVrg-Cag-Rfp tracer (b) or mean intensity fluorescence for the axons labelled with AAV1-Camk2a-Egfp (c) normalized to the intensity of the tracer at injection sites in various ventrolateral cerebral brain regions of control, Tfap2d-Het and Tfap2d-KO adult mice. Mean ± s.e.m. depicted. Two-way ANOVA with Tukey’s correction was applied. ****P < 0.0001,***P = 0.0001, **P = 0.0059 (PIR[b], HET vs KO; = 0.0039 BLAa[c], WT vs KO; =0.0034 BLAp[c], WT vs KO *P = 0.0208, 0.0124 (BLAa [b], WT vs HET, HET vs KO); =0.0309 (BLAp[b], 0.019 (BLAv[b] WT vs HET; = 0.0128 (BLAa [c] WT vs HET; = 0.0169 (BLAp [c] WT vs HET). (n = 5 (WT), 5 (Het), 4 (KO). Str, striatum; St, stria terminalis; PVT, paraventricular thalamus; ACA, anterior cingulate area. For detailed statistics, please see Supplementary Table 16.

Tfap2d-related BLC deficits increase threat response

The BLC has a crucial role in encoding the valence of environmental cues, transmitting this critical information to other brain regions tasked with triggering behavioural responses5. To investigate the effect of Tfap2d-driven BLC-related deficits on adult exploratory behaviour, we conducted open-field and zero-maze behavioural tests on adult Tfap2d-KO and Tfap2d-cKO mice and their wild-type and Tfap2d-Het littermates (Extended Data Fig. 13a,b,f–k). The findings reveal that Tfap2d-KO and Tfap2d-cKO mice exhibit a tendency to spend less time in the centre of the open field relative to their wild-type and Tfap2d-Het littermates (Extended Data Fig. 13a,f–h). All genotypes travelled the same distance, indicating no gross motor deficits in the Tfap2d-KO or Tfap2d-cKO mice (Extended Data Fig. 13a,h). In the zero-maze test, Tfap2d-KO, Tfap2d-cKO and Tfap2d-cHet mice spent more time in the closed arm of the zero maze compared with their respective wild-type groups (Extended Data Fig. 13b,i–k). Tfap2d-KO mice exhibited fewer entries to the light side of the light-dark box test than wild-type or Tfap2d-Het mice but displayed no differences in the forced swim test and tail suspension test, behavioural assays related to depression-like behaviours (Extended Data Fig. 13c–e). These data demonstrate that Tfap2d-dependent deficits in BLC formation and connectivity leads to alterations in threat behaviours in adults, in which Tfap2d-KO mice consistently avoided stressful areas across various behavioural tests. This indicates that the lack of Tfap2d during development promotes heightened ‘trait’ anxiety-like behaviour. The absence of differences in the forced swim test and tail suspension test suggests that this is specific to anxiety, and does not include depression-like behaviours. Anxiety-like behaviour is often linked to amygdalar hyperexcitability39, which aligns with disrupted BLA–PFC connections in Tfap2d-cKO mice, suggesting that reduced PFC activity may leads to increasing amygdala activity, stress reactivity and anxiety5,6.

Extended Data Fig. 13. Loss or Haploinsufficiency of Tfap2d alters non-Learned exploratory behaviors.

a) Bar graph showing the cumulative time spent (sec) and distance moved (cm) in the center vs border analysis. Tfap2d-KO spent significantly more time in the border and moved less in the center, as compared to the WT control, and Tfap2d-Het. Mean ± s.e.m. depicted. Two-way ANOVA with Tukey’s correction was applied. * represents p values, <0.05. n = 16 (WT control), 33 (Tfap2d-Het), and 29 (Tfap2d-KO). b) Cumulative time spent (seconds) and number (#) of entries in the open arm vs closed arm analysis of the o-maze test. Tfap2d-KO animals spent significantly more time in the closed arm and had more entries in the closed arm as compared to the WT control and or Tfap2d-Het animals. Mean ± s.e.m. depicted. Two-way ANOVA with Tukey’s correction was applied. ** represents p values < 0.05. n = 14 (WT control), 38 (Tfap2d-Het), 27 (Tfap2d-KO). c) Number of entries and cumulative amount of time that spent on the light side of the light-dark box. One-way ANOVA with Tukey’s correction was applied. ** and * represents p values < 0.01, <0.05 respectively. n = 10 (WT control), 10 (Tfap2d-Het), and 7 (Tfap2d-KO). d) Cumulative amount of time that animal spent immobile in the forced swim test. One-way ANOVA with Tukey’s correction was applied. n = 20 (WT control), 23 (Tfap2d-Het) and 13 (Tfap2d-KO). e) Cumulative amount of time that animal spent immobile in the tail suspension test. One-way ANOVA with Tukey’s correction was applied. n = 18 (WT control), 24 (Tfap2d-Het), and 13 (Tfap2d-KO). For detailed statistics, please see Supplementary Table 17. f) Representative heatmaps showing the cumulative movement of WT control, Tfap2d-cHet and Tfap2d-cKO animals in the open field test for 20 min. g-h) Cumulative time spent (b) and distance moved (c) in the center vs border analysis, showing the Tfap2d-cKO spent significantly more time in the border and moved less in the center, as compared to the WT control, and Tfap2d-cHet animals. Mean ± s.e.m. depicted. Two-way ANOVA with Tukey’s correction was applied. ** and * represent p values < 0.01, <0.05 respectively. n = 14 (WT control), 14 (Tfap2d-cHet) and 15 (Tfap2d-cKO). i) Representative heatmap showing the cumulative movement of WT control, Tfap2d-cHet and Tfap2d-cKO animals in the o maze test for 6 min. j-k) Cumulative time spent and number of entries in the open arm vs closed arm analysis, showing the Tfap2d-cKO and Tfap2d-cHet spent significantly more time in the closed arm and Tfap2d-cKO had more entries in the closed arm as compared to the WT control. Mean ± s.e.m. depicted. Two-way ANOVA with Tukey’s correction was applied. ** and * represents p values < 0.01, <0.05 respectively. n = 19 (WT control), 13 (Tfap2d-cHet) and 16 (Tfap2d-cKO). For detailed statistics, please see Supplementary Table 18.

The BLC has a pivotal role in facilitating the learning of associations between neutral environmental cues and adverse outcomes, such as fear conditioning1–3,5. To test the effects of Tfap2d-driven BLC-related deficits on negative-association learning, we performed fear conditioning (Fig. 5a–c and Extended Data Fig. 14a–c). Tfap2d-KO and Tfap2d-cKO mice learned this association at the same rate as their respective heterozygous and wild-type groups (Fig. 5a and Extended Data Fig. 14a). During the contextual conditioning test, Tfap2d-Het mice spent significantly less time freezing compared with wild-type mice (Fig. 5b and Extended Data Fig. 14b). During the cued conditioning test, Tfap2d-KO and Tfap2d-cKO mice and their respective heterozygous controls displayed consistently higher levels of freezing compared with wild-type mice, indicating that loss or haploinsufficiency of Tfap2d causes alterations in the expression of learned threat responses (Fig. 5c and Extended Data Fig. 14c). Of note, mice that were heterozygous for Tfap2d displayed intermediate phenotypes, suggesting that limited Tfap2d expression was sufficient to mitigate the heightened cued fear freezing seen in Tfap2d-KO mice, but insufficient to restore behaviour to wild-type levels. Conversely, contextual freezing was decreased in Tfap2d-Het mice, suggesting that the regions involved in contextual freezing, hippocampal or PFC circuitry, were more affected by the reduction in Tfap2d dosage rather than its developmental loss, which may result in compensatory plasticity that masks the phenotype in Tfap2d-cKO mice. Similar phenomena have been observed in neuronal haploinsufficiency of other mouse knockout models of AP-2 family transcription factors40, although the functions of other AP-2 genes on BLC development are not known. Together, these results suggest that haploinsufficiency or loss of Tfap2d leads to nuanced changes associated with the interpretation of salient cues that may stem from alterations in BLC-related circuitry.

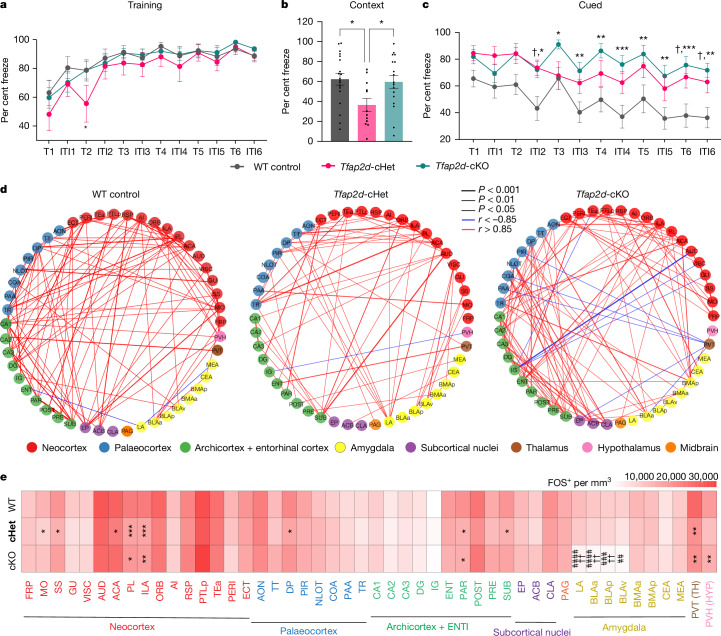

Fig. 5. Tfap2d loss or haploinsufficiency increases threat responding in learned behaviours and alters functional connectivity.

a, The percentage of time wild-type control, Tfap2d-cHet and Tfap2d-cKO mice freeze during the learning (training) period of the fear conditioning test during inter-tone interval (ITI) and tone (75 decibels, 20 s) (T) followed by a 2-s shock at 0.5 mA. b, The percentage of time wild-type control, Tfap2d-cHet and Tfap2d-cKO mice freeze during conditioned responses while in the training context. One-way ANOVA with Tukey’s correction. *P < 0.05. c, The percentage of time wild-type control, Tfap2d-cHet and Tfap2d-cKO mice freeze during trial and ITI without shock during cued responses. Data are mean ± s.e.m. Two-way ANOVA with repeated measures and multiple comparison Tukey’s correction. ***P < 0.001, **P < 0.01, *P < 0.05 for wild type versus Tfap2d-cKO; †P < 0.05 for wild type versus Tfap2d-cHet. n = 16 (wild-type control), 12 (Tfap2d-cHet) and 16 (Tfap2d-cKO). Detailed statistics are presented in Supplementary Table 9. d, Network graph depicting interregional correlation between brain regions as measured by the number of FOS-positive cells in wild-type control, Tfap2d-cHet and Tfap2d-cKO brains. Nodes, represent brain regions, edges indicate significant correlation scores (P < 0.05 and r > 0.85) and colours correspond to broader brain areas. Detailed statistics are presented in Supplementary Table 10. e, Heat map depicting the number of FOS-positive cells detected per unit area in the different brain regions of the wild-type control, Tfap2d-cHet and Tfap2d-cKO brains isolated after 60–90 min of cued test. Data are mean ± s.e.m. Two-way ANOVA with Tukey’s correction. ***P < 0.001, **P < 0.01, *P < 0.05 for n = 4 per genotype. LA, BLAa, BLAp and BLAv, wild type versus Tfap2d-cKO: ####P < 0.0001, ###P < 0.001, ##P < 0.01. Tfap2d-cHet versus Tfap2d-cKO: ††P < 0.01. Detailed statistics are presented in Supplementary Table 11. Brain region abbreviations for d,e are listed in Supplementary Table 4.

Extended Data Fig. 14. Whole-body Tfap2d loss or haploinsufficiency alters threat response in the fear conditioning test.

a) Line plot showing that during learning phase WT control, Tfap2d Het and Tfap2d KO mice freeze for same amount of time by tone 6. Mean ± s.e.m. depicted. Two-way ANOVA with Tukey’s correction was applied. b) Bar plot showing conditioned responses of the WT control, Tfap2d-cHet and Tfap2d-cKO mice as percent of time the animals froze while in the training context. Mean ± s.e.m. depicted. One-way ANOVA with Tukey’s correction for multiple comparisons was applied. * represent p values < 0.05. c) Line plot showing cued responses of the WT control, Tfap2d-cHet and Tfap2d-cKO mice. Mean ± s.e.m. depicted. Two-way ANOVA with Tukey’s correction was applied. *** and ** represent p values < 0.001, <0.01 respectively for WT vs cKO and ^^^^, ^^^ and ^^ represent p values < 0.0001, <0.001 and <0.01 respectively for WT vs cHET. n = 27 (WT control), 38 (Tfap2d Het), 26 (Tfap2d KO). d) Representative image of the mPFC showing immunostaining for FOS performed on the WT control, Tfap2d-cHet and Tfap2d-cKO brains isolated after 60-90 min of cued memory test. e) Graph depicting the number of FOS positive cells per mm2 detected within the different brain regions of the WT control, Tfap2d-cHet and Tfap2d-cKO brains isolated after 60-90 min of cued test. Mean ± s.e.m. depicted. Two-way ANOVA with Tukey’s correction was applied. ***, **, * represents p values < 0.001, <0.01, <0.05 respectively. For detailed statistics, please see Supplementary Table 19.

To discern the patterns of coordinated brain activity among multiple brain regions that are associated with fear expression during cued test41 and that may be impaired by Tfap2d haploinsufficiency or loss, we computed interregional correlations of FOS density, a measure of gross neuronal activity. We correlated FOS density between regions that are associated with cued fear such as the amygdala, neocortex, hippocampus and TH (Fig. 5d and Extended Data Fig. 15a–c). We found that significant correlations between cortical regions and the hippocampus formation in wild type mice were reduced or altered in Tfap2d-cHet and Tfap2d-cKO mice. In wild-type control mice, the FOS densities of LA and PL were negatively correlated, whereas this trend was absent in Tfap2d-cHet mice and remained insignificant in the Tfap2d-cKO mice (Fig. 5d and Extended Data Fig. 15a,b). Notably, there was a shift within the amygdala in the FOS correlation matrix for the Tfap2d-cKO mice compared with wild-type mice. In wild-type mice, FOS density in BLA was correlated with IL or mPFC; however, in Tfap2d-cKO mice, which were deficient in BLA, we observed a significant correlation in FOS density between the palaeocortical regions, including perirhinal and entorhinal cortex, and BMA with mPFC, which comprises PL, ILA and ACA (Fig. 5d and Extended Data Fig. 15a–c). These results align with the circuit alterations seen in the Tfap2d-cKO mice. However, these altered circuits do not seem to compensate for the loss of BLA, as evidenced by the altered functional connectivity and disrupted threat responses observed in the cued tests. Network graph analysis indicated a substantial reduction in the significant correlations among brain regions involved in threat response in Tfap2d-cHet mice, whereas in Tfap2d-cKO mice, we observed a shift in this connectivity compared with the wild type (Fig. 5d). These differences are consistent with the observed circuit deficits and indicate that Tfap2d haploinsufficiency alters functional connectivity of the threat-associated regions in a different manner to a total loss of Tfap2d.

Extended Data Fig. 15. Alterations in functional connectivity following cued testing due to Tfap2d deficiency in the post mitotic excitatory neurons.

a) Pearson correlation heatmap showing the functional connectivity between different brain regions measured by the FOS immunostaining of the WT control, Tfap2d-cHet and Tfap2d-cKO mice after the cued test. ***, **, * represents p values < 0.001, <0.01, <0.05, respectively (n = 4/genotype). Correlations were calculated using a two-tailed Pearson’s correlation test. For detailed statistics, please see Supplementary Table 10. b) Pearson correlation heatmap showing the functional connectivity between different brain regions measured by the FOS immunostaining of the WT control, Tfap2d-cHet and Tfap2d-cKO mice after the cued test. ***, **, * represents p values < 0.001, <0.01, <0.05, respectively (n = 4/genotype). Correlations were calculated using a two-tailed Pearson’s correlation test. c) Heatmap showing the differences seen in the Pearson correlations between WT controls, Tfap2d-cHet and Tfap2d-cKO calculated by Fisher’s z-transformations. ***, **, * represents p values < 0.001, <0.01, <0.05, respectively (n = 4/genotype). Highlighted in bold are the regions that express Tfap2d. Statistical significance of correlations was assessed using Fisher’s Z transformations, with a two-tailed test applied to compare correlation coefficients d. For abbreviations and details of regions grouped please refer to Supplementary Table 5. For detailed statistics, please see Supplementary Tables 20 and 21.

Concurrently, we observed significantly fewer FOS-positive cells in the mPFC (ILA and PL) in Tfap2d-KO and Tfap2d-Het mice, as well as in Tfap2d-cKO and Tfap2d-cHet mice, compared with the respective wild-type groups (Fig. 5e and Extended Data Fig. 14d,e). We note that this pattern of FOS expression was not observed in the amygdala, where there were fewer FOS-positive cells in LA, BLAa and BLAp in Tfap2d-KO and Tfap2d-cKO mice compared with the respective heterozygous and wild-type mice. These data suggests that haploinsufficiency of Tfap2d in early life, although it is not sufficient to impair BLC formation, may nevertheless lead to differences in the expression of, but not the acquisition of, learned defensive behaviours, which are also reflected in differences in FOS levels across the brain.

Discussion

This study advances our understanding of the development and evolution of the VLp. The key findings of this study are the identification of the SOX4-, SOX11- and TFAP2D-dependent gene regulatory network, which is essential for the proper development of VLp excitatory neurons. We highlight the nuanced role of TFAP2D gene dosage, which affects brain structure development, behaviour and connectivity. Although Tfap2d expression is conserved across species, its regulatory networks show key differences. The presence of an Alu cassette in the human TFAP2D locus suggests potential human-specific variations in its expression42, which may contribute to unique characteristics in these brain regions. These adaptations are likely to fine tune Tfap2d dosage, which is crucial for BLC development and connectivity.

These findings lay a foundation for future research on Tfap2d-dependent mechanisms, their association with neurodevelopmental disorders and the development of tools to selectively target specific brain regions. Mutations in SOX4 and SOX11 cause intellectual disability and other neurodevelopmental alterations43–45, and variants in the TFAP2D locus are associated with bipolar disorder and emotional dysregulation46–50. Our work thus opens new avenues for investigating the molecular mechanisms that underlie development of BLC and palaeocortex in the context of disease. This exploration may uncover how alterations in these processes contribute to neural traits and disease conditions and offer novel insights into pathogenesis.

Methods

Animals

All experiments were carried out with the protocol approved by the Committee on Animal Research at Yale University. The research methodologies for the use of mice (Mus musculus) and rhesus macaques (Macaca mulatta) were implemented following the guidelines sanctioned by the Yale University Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) and the directives of the US National Institutes of Health. The care and management of the animals were conducted within the precincts of the Yale Animal Resource Center, ensuring controlled environments for both prenatal and postnatal development stages of mouse and primate specimens. The mice were group-housed, maintaining a density of fewer than five individuals per cage, under environmental conditions regulated at 25 °C and 56% relative humidity, complemented by a photoperiod consisting of 12 h of light and 12 h of darkness. Nutritional needs were met ad libitum, coupled with veterinary oversight provided by the centre’s staff. The genetic lineage of the subjects was maintained on a C57BL/6 J strain, with experimental cohorts comprising both genders, randomly designated to respective studies. The detection of a vaginal plug in the mouse subjects was recorded as gestational day 0.5, marking the initiation of the experimental timeline. The Sox4fl/fl and Sox11fl/fl mice were a kind gift from V. Lefebvre. The Tfap2d-Lacz mice were a kind gift from M. Moser and the generation and genotyping were previously described30 (Extended Data Fig. 7a). These mice were generated by inserting a Lacz cassette that disrupts the exon 1 of the Tfap2d locus, abolishing the proper expression of the trapped allele, Tfap2d. The Nex1-Cre (Neurod6-cre) were a kind gift from the laboratory of K.-A. Nave and CAT-Gfp mice were procured from Jackson Laboratories52. We bred these mice with Sox4fl/fl and Sox11fl/fl to obtain controls (Sox4fl/+; Sox11fl/+; Neurod6-cre; CAT-Gfp or Sox4fl/fl; Sox11fl/fl), Sox4-cKO (Sox4fl/fl; Sox11fl/+; Neurod6-cre; CAT-Gfp), Sox11-cKO (Sox4fl/+; Sox11fl/fl; Neurod6-cre; CAT-Gfp) and Sox4/Sox11-cdKO (Sox4fl/fl; Sox11fl/fl; Neurod6-cre; CAT-Gfp). Further we also bred Tfap2dfl/fl and obtained wild-type control (Tfap2d+/+; Neurod6-cre; CAG-CAT-Gfp or Tfap2dfl/fl) Tfap2d-cHet (Tfap2dfl/+; Neurod6-cre; CAG-CAT-Gfp) and Tfap2d-cKO (Tfap2dfl/fl; Neurod6-cre; CAG-CAT-Gfp). Refer to Supplementary Table 3 for genotyping details. Although blinding was not relevant for the primary mutant versus control comparison, other aspects of the study required careful design to minimize bias. Randomization was implemented while acquiring the data, including the behaviour data. Littermates (WT, HET and KO) were housed together, to avoid confounding housing effects on statistical analyses. The experimental cohort comprised male and female littermates aged between PD 120 and 180. Including samples from multiple litters further enhanced reproducibility.

Postmortem human and macaque brain tissue

Human brain samples were collected postmortem at PCW17. Rhesus macaque brain samples were collected postmortem at PCD105. Whole slabs or whole hemispheres were post-fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA) for 48 h and then cryoprotected in an ascending gradient of sucrose (10%, 20%, 30%). Tissue was handled in accordance with ethical guidelines and regulations for the research use of human brain tissue set forth by the NIH (http://bioethics.od.nih.gov/humantissue.html) and the World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki (http://www.wma.net/en/30publications/10policies/b3/index.html). All experiments using non-human primates were carried out in accordance with a protocol approved by Yale University’s Committee on Animal Research and NIH guidelines.

Generation of Tfap2d-floxed mice

Guide RNA sequences (gRNAs) to insert flox sites were designed using an online program (http://zlab.bio/guide-design-resources)53. gRNAs with the minimum off-target effects were selected, and DNA oligonucleotides carrying guide RNA sequences were cloned into pX330 vector. The sequences of the guide oligonucleotides used are listed in Supplementary Table 3. Cas9 mRNA were in vitro transcribed from vector px330 linearized by restriction enzyme NotI-HF (New England Biolabs, R3189S) and purified by phenol/chloroform extraction. We inserted the flox sites into intron 1 and intron 3. Founders were genotyped and bred at least 3 generations to exclude chimeras. Genotyping of mice for floxed allele was performed using primers listed in Extended Data Fig. 8a,b, Supplementary Fig. 1 and Supplementary Table 3.

In situ hybridization

The cDNA (Tfap2d human: ENSG00000008197; Tfap2d mouse:; Tfap2d macaque: ENSMMUT00000004057; Lmo3: ENSMUSG00000030226; Etv1: ENSMUST00000095767; Mef2c: ENSMUST00000163888, Cyp26b1: ENSMUST00000077705) for generating the human and mice probes was procured from Dharmacon and the plasmid was cut using NotI-HF enzyme. For the Tfap2d mouse probe, three different probes were amplified from PD0 and adult cDNA using the primers listed in Supplementary Table 3. The Tfap2d V3 probe worked best across ages and was used in the manuscript for detection of Tfap2d expression. The macaque probe was generated using respective neocortical tissues cDNA as a template by TA-cloning kit (Invitrogen, K202020). The cDNA clones were purified through the Qiagen clean up kit (Qiagen, 28104) and in vitro transcription (Millipore Sigma- Roche, 10999644001) was performed per the manufacturer’s instructions. Templates were purified by phenol/chloroform extraction and digoxigenin-labelled probes were synthesized using T3 (Roche, RPOLT3-RO) and T7 RNA polymerases (Roche, RPOLT7-RO) respectively, and RNA labelling mix (Roche, 11277073910) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Probes were purified by ethanol precipitation, quantified, quality controlled and stored at −80 °C until hybridization. For in situ hybridization, slide-mounted cryo-sections at 60–70 μm thickness were processed. In brief, brains were fixed overnight at 4 °C in 4% PFA (Electron Microscopy Sciences, 15711) diluted in Dulbecco’s phosphate buffer (DPBS) (Thermo Fisher Scientific, 14190144), equilibrated for 12 h at 4 °C in 10% sucrose, and another 12 h at 4 °C in 30% sucrose in DPBS. Fixed brains were then embedded in OCT (Scigen, 23-730-571) and sliced on a cryostat (Leica Biosystem, CM1800). Slides were stored at −80 °C until processed for in situ hybridization. Sections were first post-fixed in 4% PFA in PBS for 15 min at room temperature, washed with PBS, and treated with 0.5 μg ml−1 proteinase K solution (15 min at room temperature for P0 and 30 min at room temperature for adults). Slides were post-fixed in 4% PFA in PBS for 15 min at room temperature, washed with PBS. Slides were treated with acetic acid and triethonalamine solution for 10 min, followed by PBS washes. Slides were then submerged in hybridization buffer (5× SSC, 50% formamide, 20% SDS and 250 μg ml−1 of Torula yeast RNA, aBSA (25 mg ml−1), heparin stock (50 mg ml−1)) supplemented with 1,000 ng ml−1 of the appropriate digoxigenin-labelled probe at 70 °C overnight. Sections were washed 3 times for 45 min at 70 °C in 2× SSC, 50% formamide, 1% SDS, and then three times with TBST and incubated overnight at 4 °C with an anti-digoxigenin antibody conjugated to alkaline phosphatase (1:5,000, Roche, 11093274910). Sections were washed and then rinsed in the substrate buffer (100 mM Tris-Cl pH9.5, 100 mM NaCl, 50 mM MgCl2, 0.1% Tween-20) before being overlaid with NBT/BCIP substrate (Roche). Colour development was done at room temperature in the dark until the desired signal was reached. Finally, sections were rinsed in EDTA solution and DPBS, washed in water and mounted with VectaMount AQ Aqueous Mounting Medium (Vector Laboratories, H-5501-60).

RNA in situ hybridization (RNAscope) analysis on mouse and chicken brain tissue

Brains from the embryonic chicken (PCD17) and mouse (PCD16.5) were fixed in 4% PFA overnight at 4 °C. They were sectioned at 20 μm and slides were stored in −80 °C until use. RNAscope was performed as per RNAscope Multiplex FL v2 protocol and kit (323270) from ACD (Advanced Cell Diagnostics bio) with slight modification. In brief, the slides were thawed and washed with 1× PBS for 5 min at room temperature, followed by incubation at 60 °C for 30 min in the HybEZ hybridization system (321711). Slides were fixed for 30 min at 4 °C, followed by dehydration with ethanol (50%, 70%, and 100%, each for 5 min). Slides were then air dried for 5 min and then incubated at 60 °C for 15 min. Slides were treated with hydrogen peroxide for 10 min and washed with distilled water twice for 2 min. They were again incubated at 60 °C for 15 min and then washed with boiling water for 10 s. Further, target retrieval was performed using the RNAscope target retrieval reagents for 5 min in a boiling beaker. The samples were washed with distilled water again and then incubated with 100% ethanol for 5 min. Slides were incubated at 60 °C for 15 min. Using a barrier pen a boundary was created and the slides are incubated with 5 drops of the RNAscope protease III for 30 min. Samples are then washed with distilled water and incubated with the C1, C2, C3 probes for 2 h at 40 °C. After that samples were incubated sequentially with RNAscope Multiplex FL v2 Amp 1, Amp 2 and Amp 3 for 30 min each with intermittent washes with 1× wash buffer twice for 2 min. The slides were then incubated with horseradish peroxidase–C1, followed by tyramide signal amplification, horseradish peroxidase blocker each with intermittent washes with 1× wash buffer twice for 2 min. These steps were repeated for C2, C3 and slides were mounting. Slides were imaged on the VS 200 microscope (Olympus Microscopy). For mice tissue, milder conditions were used. We used 1 h fixation, 2 min target retrieval treatment and proteinase plus 10 min. We used the following probes: chicken Tfap2d (NPR-0050976, ACD) and mouse Tbr1 (413301, ACD), Ngn2 (417291, ACD) and Sema5a (508091, ACD).

Immunohistochemistry

Brains isolated from prenatal and early postnatal mice were fixed overnight in paraformaldehyde (PFA) at 4 °C. Immunostaining was performed on the sections of 60–70 μm thickness cut on vibratome. Sections were blocked for 1 h at room temperature with blocking buffer consisting of 10% Donkey serum (Jackson ImmunoResearch, AB_2337258), 1% BSA (Millipore Sigma, A4612), 0.3% Triton X-100 (ThermoFisher, A16046.AP) in 1× PBS. After blocking, sections were incubated overnight at 4 °C with primary antibodies for SATB1 (1:500, Santacruz, sc-5989), TBR1 (1:1,000, Abcam, ab183032), NR4A2 (1:500, R&D systems, AF2156), CUX1 (1:1,000, Santacruz, sc-13024), BCL11B (1:2,000, Abcam, ab18465), FOS (1:500, Cell Signalling, 2250), BHLHE22 (1:1,000; Abcam, ab204791), GFP (1:500; Abcam, ab13970) and RFP (1:500, Abcam, ab124754). Sections were washed with washing buffer (0.3% Triton X-100 in 1× PBS) 3 times, 10 min each and were incubated with secondary antibodies (Jackson ImmunoResearch) for 1 h at room temperature, followed by 3 washes with washing buffer for 10 min each. Sections were mounted onto glass slides with vector shield (Vector labs, H-1000) and sealed with nail polish. All the slides were stored at −20 °C for further analyses. Antigen retrieval was performed on the brain sections prior to NR4A2 and TBR1 immunostaining (Dako Antigen Retrieval Solution, GV80511-2). For acquiring the images, LSM 800 (Zeiss Microsystems) and VS 200 microscope (Olympus Microscopy) were used. Analyses of the images was done using ZEN software, Qupath54, OlyVIS or Fiji55 using BioFormats plugin.

In utero electroporation

In utero electroporation was performed on PCD12.5 Sox4fl/fl; Sox11fl/fl timed-pregnant females with pNeurod1-cre and pCalnl-Tfap2d-Gfp on the right-side uterine horns and with pNeurod1-cre and pCalnl-Gfp into the left side uterine horns. Nearly 50% of all the embryos were injected with 0.5 μl DNA preparation (4 μg μl−1 DNA mixed with 0.05% Fast Green FCF dye (Sigma-Aldrich)). The DNA was injected into the lateral ventricle of the embryos and guided for electroporation to the pallial–subpallial boundary using gene paddle electrode (EC1 45-0122 3 × 5 mm, Harvard apparatus) and square-wave pulse electroporator (Harvard Apparatus) at 30–33 V, 5 pulses, 50 ms ON and 950 ms OFF At PCD16.5, viability of the electroporated pups was screened and the embryos in healthy conditions were used for further analysis. GFP expression was grossly determined by NIGHTSEA Full System with UV (EMS, SFA-UV). Embryos with the fluorescence signal were dissected to isolated brains and were fixed for 24 h in 4% PFA overnight at 4 °C, and brains were analysed as previously described. The brains were sectioned at 70 µm into 5 wells of a 24-well plate serially and all the sections from 1 well were stained for GFP, CC3 (1:1,000, Cell Signaling (Asp175) Antibody 9661), which marks dying cells and ADGRE1 (1:500, Bio-Rad, MCA497RT), which labels infiltration and activation of microglia56, using the protocol described above. For image acquisition, LSM 800 (Zeiss Microsystems) and VS 200 microscope (Olympus Microscopy) were used. Image analysis was done using ZEN software, Qupath54, OlyVIS or Fiji55 using the BioFormats plugin.

Quantification of RNAscope and immunostaining

Images were acquired using the VS 200 microscope and analysed with QuPath. The images were opened directly in QuPath, and regions of interest (ROIs) were outlined using the Allen Brain Atlas or Mouse Developing Brain Atlas as references. For quantification, 5–6 coronal sections per brain, spanning from the anterior to posterior axis, were analysed. As we collected 70-µm sections into 5 wells, the sections analysed were nearly 400 µm apart. For RNAscope, the brains were sectioned at 20 µm and collected onto 10 slides. The number of cells above a set threshold in their respective channel and DAPI-positive cells within the ROI were quantified in QuPath and their ratio to DAPI was then calculated. Data from mutant brains were normalized to the wild-type littermates for CC3 and ADGRE1. For the quantification of BHLHE22 intensity, regions were analysed using the straighten plugin in ImageJ. A custom-made ImageJ program was used to divide the straightened PIR into 200 equal bins. The BHLHE22 intensity distribution was determined by calculating the intensity per bin relative to the total intensity across all bins. The data were plotted into graphs using GraphPad Prism version 10.0.0 for Windows (GraphPad Software). For statistics, the two-way ANOVA, one-way ANOVA or pairwise comparisons were directly performed in the GraphPad Prism.

Generation and analysis of RNA-seq data

The cerebral cortex and amygdala from P0 Sox4/Sox11-cdKO, Sox11-cKO, Sox4-cKO and littermate control pups were collected (n = 3). Total mRNA was extracted using mirVANA Kit and DNAse digestion was performed using Tubro DNAse. Libraries were prepared with Illumina TruSeq mRNA preparation kit (Illumina RS-122-2101) for whole cortices, per the manufacturer’s instructions. Libraries were quality controlled by Tapestation/Bioanalyzer analysis and sequenced on the Illumina HiSeq 2000 platform at Yale Center for Genome Analysis (YCGA) to generate 75 bp single reads. Sequencing data were quality controlled by FastQC and aligned to the mouse genome (NCBI37/mm9) using STAR (v2.4.0e) (10.1093/bioinformatics/bts635). To improve the mapping quality of splice junction reads, mouse gene annotation retrieved from the GENCODE project (version M1) was additionally provided (10.1101/gr.135350.111). The command line “–sjdbOverhang 74” was used to construct a splice junction library. At least ten million uniquely mapped reads were obtained for each sample. Differential gene expression DEX analysis was performed by the R package DESeq2 (10.1186/gb-2010-11-10-r106) and principal components analysis was performed by the R package prcomp. Genes with |log2 fold change| ≥ 0.5 and a false discovery rate < 0.01 were classified as DEX. Integrated analysis was performed to identify the number of common or distinct DEX between Sox4/Sox11-cdKO, Sox11-cKO and Sox4-cKO. In total, 928 uniquely upregulated and 659 uniquely downregulated in Sox4/Sox11-cdKO were selected as candidate downstream targets, as shown in Supplementary Tables 1 and 2.