Summary

Background

Synuclein pathology in neurodegenerative diseases, such as Parkinson’s disease (PD) and Dementia with Lewy bodies (DLB), begins years before motor or cognitive symptoms arise. Alpha-Synuclein seed amplification assays (α-syn SAA) may detect aggregated synuclein before symptoms occur.

Methods

Data from the Parkinson Associated Risk Syndrome Study (PARS) have shown that individuals with hyposmia, without motor or cognitive symptoms, are enriched for dopamine transporter imaging (DAT) deficit and are at high risk to develop clinical parkinsonism or related synucleinopathies. α-syn aggregates in CSF were measured in 100 PARS participants using α-syn SAA.

Findings

CSF α-syn SAA was positive in 48% (34/71) of hyposmic compared to 4% (1/25) of normosmic PARS participants (relative risk, 11.97; 95% CI, 1.73–82.95). Among α-syn SAA positive hyposmics 65% remained without a DAT deficit for up to four years follow-up. α-syn SAA positive hyposmics were at higher risk of having DAT deficit (12 of 34) compared to α-syn SAA negative hyposmics (4 of 37; relative risk, 3.26; 95% CI, 1.16–9.16), and 7 of 12 α-syn SAA positive hyposmics with DAT deficit developed symptoms consistent with synucleinopathy.

Interpretation

Approximately fifty percent of PARS participants with hyposmia, easily detected using simple, widely available tests, have synuclein pathology detected by α-syn SAA. Approximately, one third (12 of 34) α-syn SAA positive hyposmic individuals also demonstrate DAT deficit. This study suggests a framework to investigate screening paradigms for synuclein pathology that could lead to design of therapeutic prevention studies in individuals without symptoms.

Funding

The study was funded by the U.S. Department of Defense, the Helen Graham Foundation and the Michael J. Fox Foundation for Parkinson's Research.

Keywords: Parkinson’s disease, Biomarkers, Dopamine transporter imaging, Prodromal

Research in context.

Evidence before this study

We searched PubMed with the terms Parkinson’s disease (PD), prodromal, non-manifest carriers, REM sleep behaviour disorder (RBD), GBA, LRRK2 and dopamine transporter imaging and real-time quaking induced conversion (RT-QuIC), protein misfolding cyclic amplification (PMCA), and seed amplification assay (SAA) for articles published in English on or before Dec 1, 2023, in any field. This is a large and rapidly growing literature, and a number of studies were identified, including studies of older heathy individuals and case-series of patients with PD with and without genetic variants, individuals with isolated RBD, and a small number of studies (4) of non-manifesting carriers of genetic variants associated with PD.

Added value of this study

This report demonstrates that approximately 50% of otherwise healthy hyposmic older individuals may be α-syn SAA positive. While this is a small sample, the strengths of our data are the comprehensive participant evaluation including dopamine transporter imaging and long duration of follow-up after the CSF α-syn SAA data was acquired. These data are enhanced in value because of the availability of a comparison group of normosmic individuals similarly assessed. The key findings in this study include: 1) a higher relative risk (11.97; 95% CI, 1.73–82.95) of α-syn SAA positive results in older otherwise healthy hyposmic individuals compared to normosmic individuals; 2) a higher relative risk (3.26; 95% CI, 1.16–9.16) of DAT deficit in hyposmic α-syn SAA positive individuals compared to hyposmic α-syn SAA negative individuals and in turn a higher relative risk (12.83; 95% CI, 1.78–92.37) of clinical manifestations of PD in hyposmic α-syn SAA positive DAT deficit individuals compared to hyposmic α-syn SAA positive individuals without DAT deficit.

Implications of all the available evidence

These data suggest that olfactory function testing may be a simple and easily accessible tool to enrich for α-syn SAA positive individuals. These results provide preliminary data to further investigate a model in which synuclein pathology may occur before dopamine pathology and that both synuclein and dopamine pathology are in turn necessary for development of clinical symptoms. This study therefore provides a framework to investigate a screening paradigm to clarify the prevalence of synuclein pathology, to understand the pre-symptomatic biomarker signatures of disease progression and to design prevention studies in individuals with biomarker evidence of parkinsonism and related synucleinopathies.

Introduction

Overwhelming evidence from longitudinal population and biomarker studies demonstrates that the pathological process underlying neurodegenerative diseases, such as Parkinson’s disease (PD) and Dementia with Lewy bodies (DLB), begins years before motor symptoms arise.1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6 Recent data has further shown that biomarker signals detected prior to symptoms may provide a temporal signature of early synuclein pathology and dopaminergic dysfunction.7

Identifying individuals with biomarker evidence of disease prior to symptoms will enable therapeutic studies targeting early pathology that offer the promise of slowing or prevention of symptom onset.8,9

Αlpha-synuclein (α-syn) seed amplification assays (SAA) have emerged as a tool to reliably detect α-syn pathology in life.10 Studies have shown that α-syn SAA in cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) has high accuracy for identifying individuals diagnosed with PD or DLB compared to healthy controls or other non-synuclein degenerative disorders11, 12, 13 and is highly correlated with α-synuclein pathology at autopsy.4,14 Importantly, α-syn SAA can detect pathology in individuals with REM sleep behaviour disorder (RBD) and/or severe loss of olfactory function (hyposmia) at high risk of developing PD, DLB or other synucleinopathies.6,7,15

The Parkinson Associated Risk Syndrome Study (PARS) is a longitudinal, observational study designed to investigate a sequential biomarker strategy.1 Data from PARS have shown that individuals with hyposmia are enriched for DAT deficit and in turn those individuals with hyposmia and DAT deficit are at high risk to develop clinical parkinsonism and related synucleinopathies. We now report additional data from the PARS study on the frequency of positive CSF α-syn SAA in individuals with and without hyposmia. We further examine the temporal relationship between α-syn SAA status, DAT deficit and onset of clinical synucleinopathy. We propose that a biomarker signature for PD can be detected that may enable screening and therapeutic interventions early in the pathological process prior to onset of motor or cognitive symptoms.

Methods

Ethics

Details of the PARS study design have been reported previously.1 The study was coordinated at the Institute for Neurodegenerative Disorders (IND; New Haven, CT) and includes 15 clinical centers in the US. Informed consent was obtained from all study participants prior to collection of any study data. The protocol received approval by the Western Institutional Review Board (WIRB Protocol #20061587) and the Human Research Protection Office (HRPO) at the U.S. Army Medical Research Material and Command (USAMRMC) (USAMRMC HRPO # A-13976.a).

Participant selection

Participants were initially contacted by mail and completed olfactory testing at home. Details of the cohort contacted by mail have been described previously.16 Briefly, the PARS cohort was recruited from both neurology practices targeting relatives of patients with PD and widespread direct mailings to organizations including veterans, nurses, and members of community organizations without regard for family history. The 303 participants from the PARS clinical cohort (enrolled from Oct 2007 to Oct 2009) included 100 normosmic and 203 hyposmic individuals. Individuals age ≥50 years old or within 10 years of age of onset of an affected first-degree relative with PD and with no known reason for abnormal olfaction were considered eligible for participation. Those with an established diagnosis of PD, evidence of cognitive impairment, or parkinsonism on baseline assessment were excluded from participation. Hyposmia was defined as a University of Pennsylvania Smell Identification Test (UPSIT) score that was at or below the 15th percentile for age and sex (self reported) based on cohort-specific norms.17

Clinical evaluations

Clinical evaluations were conducted at baseline and annually for up to ten years in hyposmics and included a neurological examination and a diagnostic questionnaire. The majority of the normosmics were followed for only two years due to funding constraints. Participants were also assessed for features associated with risk of PD and related synucleinopathies including: constipation,18 subtle parkinsonism signs using the PD Symptom Rating Scale (SRS),19 and REM sleep behaviour disorder (RBD).20 Other clinical assessments included the Unified Parkinson’s Disease Rating Scale (UPDRS)21 and the Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE).22 All clinical assessments were conducted by investigators blind to both olfactory and imaging data. Conversion to clinical parkinsonism or related synucleinopathy was determined by a movement disorders neurologist at annual clinical visits. All PARS participants underwent whole genome sequencing and none of the participants has a LRRK2 variant.23 A subset of individuals (n = 100) had CSF collection, which could occur at any study visit. CSF was processed according to the Parkinson Progression Marker initiative (PPMI) biologic sample manual 7.0 (https://www.ppmi-info.org).

[123I]β-CIT SPECT imaging

DAT imaging, using [123I] β-CIT SPECT, was obtained at baseline and biennially up to six years for a total of four imaging visits: baseline, year 2 (2.1 ± 0.3 years), year 4 (4.3 ± 0.5 years), and year 6 (6.2 ± 0.4 years). The lowest putamen specific binding ratio (SBR) was determined as previously described.24 The percent of age-expected lowest putamen SBR was used to define imaging groups.25 For this analysis, percent of age-expected lowest putamen was categorized as: DAT deficit defined as <70% expected and no DAT deficit defined as ≥70% expected. For participants who had no DAT deficit at baseline, image conversion was defined as progressing to an age-expected lowest putamen reduction of <70% at any visit. The cutoff of <70% is modified from prior studies in which the DAT deficit cutoff was <65%. This is based on longitudinal DAT data in a group of PARS participants with baseline age-expected lowest putamen between 65% and 70% of normal that all demonstrated DAT deficit <60% on follow-up scans.26 All imaging analyses were performed without access to clinical or diagnostic information.

α-syn seed amplification assay

The α-syn seed amplification assay developed by Concha-Marambio and colleagues at Amprion Inc., was performed as previously reported with some modifications.7,27 Briefly, CSF samples were tested in triplicate (40 μL/well) using a clear bottom 96-well plate. The final 100 μl reaction mixture included 0.3 mg/mL recombinant α-syn (Amprion, cat# S2020), 100 mM PIPES pH 6.50 (Sigma, cat# 80,635), 500 mM NaCl (Lonza, cat# 51,202), 10 μM ThT (Sigma, cat# T3516), and 2 1/8” Si3N4 bead (Tsubaki Nakashima). Plates were intermittently shaken at 800 rpm for 1 min every 15 min cycles in a BMG FLUOstar Omega shaker/reader at 42 °C. Sample result was determined using the maximum fluorescence (Fmax) from the three replicates. All α-syn SAA analyses were performed without any knowledge of participant demographic, clinical and imaging data.

Statistics

Statistical analyses were performed using SAS v9.4 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC) and R 4.3.1 (R Core Team, Vienna, Austria). Since prior findings have suggested that the presence of hyposmia is linked with a higher risk of developing clinical PD,1 and that CSF α-syn SAA is a useful biomarker for PD,7 we set out to try to replicate these associations. All available samples were included in the analysis. Because the analytic samples had already been collected and the sample size was fixed by the number of previously collected CSF samples, formal sample size calculation were not prospectively performed. However, post-hoc calculations were conducted in a conservative manner to assess the maximum expected width of the 95% confidence intervals for estimating the positivity rate among hyposmics and normosics. With a sample size of 71 hyposmic and 25 normosmic participants, the maximum expected width of the 95% confidence intervals were determined to be ±12% and ±20% respectively. While these widths are quite large, it was felt that they still provided sufficient information to examine the positivity rates to help inform future screening and ultimately early therapeutic interventions. Since CSF was acquired at various visits (i.e., baseline or follow-up imaging), analyses were aligned such that time of CSF collection corresponded to time zero. Descriptive statistics are reported as median (IQR) due to skewness of the data and frequency (percentage) for continuous and categorical measures, respectively. To estimate and compare the frequency of CSF α-syn SAA positivity by olfactory status, a modified Poisson regression model with robust error estimation was used to compute the relative risk and associated 95% confidence interval, with adjustment for 1st-degree family history of PD. Otherwise, unadjusted point estimates are reported alongside 95% confidence intervals. For continuous measures, median differences were calculated with bootstrap confidence intervals derived using a resampling procedure with 10,000 iterations. For categorical variables, relative risks with Wald confidence intervals are reported; in the event of zero cell counts, a value of 0.5 was added to each cell. As the widths of these intervals have not been adjusted for multiplicity, they should not be used to infer definitive group effects.

Role of funders

None of the funders had a role in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript; and decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Results

Baseline characteristics in PARS participants with CSF

CSF was acquired from 100 of 303 PARS participants. Comparison of the PARS participants with CSF to participants without CSF showed that participants with CSF were more likely to be male and to have a family history of PD, but were similar in age, olfactory status, percent with DAT deficit and percent with subsequent parkinsonism or related synucleinopathy (data not shown).

CSF, which could be obtained at any PARS visit, was acquired at study baseline in 15 participants, year 2 in 79 participants, year 4 in 4 participants, year 6 in 1 participant, and year 8 in 1 participant. In this analysis, the PARS study visit at which CSF was obtained has been designated as a reference visit time 0 and PARS visits prior to and following are timed to the CSF visit. CSF visits occurred coincident with DAT imaging visit in 99 of 100 participants. For one participant, CSF acquisition occurred two years after the last DAT imaging visit.

α-syn SAA in hyposmic and normosmic PARS participants

α-syn SAA was positive in 48% (34/71) of hyposmic compared to 4% (1/25) of normosmic PARS participants (Table 1) with 4 inconclusive participants excluded (relative risk, adjusted for 1st-degree family history of PD, 12.15; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.77–83.32).

Table 1.

Characteristics of PARS SAA participants by olfactory status.a

| Characteristic | Hyposmic (N = 71) | Normosmic (N = 25) | Estimate (95% CI)b |

|---|---|---|---|

| Demographics | |||

| Median age at CSF collection (IQR) — yr | 65 (62–74) | 63 (55–66) | 1.93 (−2.35 to 6.22) |

| Male sex — no. (%) | 46 (65) | 12 (48) | 1.35 (0.87–2.10) |

| Race or ethnic group — no. (%)c | 1.13 (0.96–1.33) | ||

| White, non-Hispanic | 65 (92) | 20 (80) | |

| Hispanic or Latinx | 0 (0) | 3 (12) | |

| Black, non-Hispanic | 1 (1) | 0 (0) | |

| Missing data | 5 (7) | 2 (8) | |

| 1st-degree relative(s) with PD — no. (%) | 35 (49) | 19 (76) | 0.65 (0.47–0.90) |

| Key baseline biomarker | |||

| α-syn SAA result — no. (%)d | 11.97 (1.73–82.95) | ||

| Positive | 34 (48) | 1 (4) | |

| Negative | 37 (52) | 24 (96) |

IQR denotes interquartile range.

Estimates (median differences for continuous measures, relative risks for categorical measures) and 95% confidence intervals have not been adjusted for multiplicity and should not be used in place of hypothesis testing.

Race or ethnic group was reported by the participants. The associated relative risk compares non-Hispanic White to all other non-missing groups.

Adjustment for 1st-degree relative(s) with PD yielded a similar relative risk (95% CI): 12.15 (1.77–83.32). For simplicity, the unadjusted values are reported.

α-syn SAA positive hyposmic participants were significantly older (median difference, 7.56 years; 95% CI, 3.59–11.54) and more likely to be male (82% vs. 49%; relative risk, 1.69; 95% CI, 1.17–2.44) compared to α-syn SAA negative hyposmic participants (Supplementary Table S1). There was no difference between the hyposmic groups in UPDRS part III, MMSE, RBD symptom frequency, or bowel movement frequency (Table 2) or in first degree family member status (Supplementary Table S1).

Table 2.

Baseline clinical and biomarker characteristics of hyposmic PARS SAA participants.a

| Characteristic | SAA + Hyposmicb (N = 34) | SAA- Hyposmic (N = 37) | Estimate (95% CI)c |

|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline clinical measures | |||

| Median UPDRS III score (IQR)d | 1 (0–3) | 1 (0–3) | 0e |

| Median MMSE score (IQR)f | 29 (28–30) | 29 (28–30) | 0e |

| Missing data | 7 | 8 | |

| 1 RBD symptom per month or more — no. (%)g | 9 (26) | 6 (16) | 1.36 (0.59–3.15) |

| Missing data | 12 (35) | 17 (46) | |

| Less than 1 bowel movement per day — no. (%)g | 7 (21) | 5 (14) | 1.59 (0.56–4.48) |

| Missing data | 4 (12) | 3 (8) | |

| Baseline biomarker measures | |||

| Median % age-expected DAT lowest putamen SBR (IQR) | 0.89 (0.69–1.09) | 0.95 (0.86–1.06) | −0.05 (−0.17 to 0.08) |

| DAT < 70% at baseline — no. (%) | 9 (26) | 3 (8) | 3.26 (0.96–11.07) |

IQR denotes interquartile range.

One participant had CSF collected after completing all imaging visits; the last completed imaging visit was used to impute baseline measures.

Estimates (median differences for continuous measures, relative risks for categorical measures) and 95% confidence intervals have not been adjusted for multiplicity and should not be used in place of hypothesis testing.

Scores on part III of the Unified Parkinson’s Disease Rating Scale (UPDRS) range from 0 to 108, with higher scores indicating worse motor function.

For point estimates of 0, no confidence intervals are provided.

Scores on the Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) range from 0 to 30, with lower scores indicating poorer cognition.

The associated relative risk compares participants with non-missing values only.

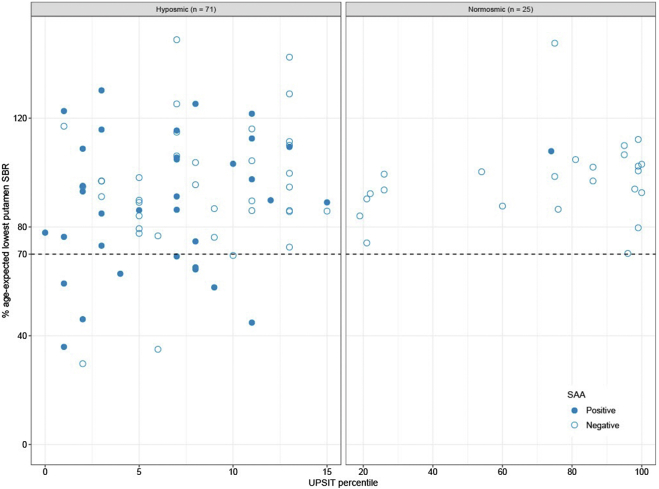

The majority of both α-syn SAA positive (74%) and α-syn SAA negative (92%) hyposmics had no DAT deficit in their lowest putamen SBR at the baseline visit (Fig. 1). There were 9 (26%) α-syn SAA positive compared to 3 (8%) α-syn SAA negative individuals with DAT deficit at baseline (Table 2). There were no α-syn SAA positive DAT deficit normosmic individuals at baseline (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

α-syn SAA Status and DAT binding in PARS hyposmics vs. normosmics. Comparison of PARS participants by olfactory status with hyposmia defined as <15th UPSIT percentile by age and sex. DAT deficit is defined as <70% of age expected lowest putamen specific binding ratio (SBR).

Longitudinal DAT and clinical diagnosis in α-syn SAA positive and α-syn SAA negative hyposmics

PARS participants were followed for up to 10 years with clinical assessments. The median (IQR) follow-up from their baseline CSF visit was 4.1 (3.4, 4.7) years for α-syn SAA positive and 4.1 (2.9, 4.6) years for α-syn SAA negative hyposmic participants. While the majority of α-syn SAA positive hyposmic participants remained in the no DAT SBR deficit category during the entire follow-up period, as shown in Fig. 2, 8 of 9 participants with a DAT deficit at baseline continued to have a DAT deficit. Furthermore, an additional 3 α-syn SAA positive hyposmic participants developed a DAT deficit. By comparison, among the α-syn SAA negative hyposmic participants, 3 individuals with DAT deficit at baseline maintained a DAT deficit, and an additional one participant had reduced DAT SBR during follow-up. Over the course of the study, α-syn SAA positive hyposmics had a higher risk to have a DAT deficit compared to α-syn SAA negative hyposmics (35% vs. 11%; relative risk, 3.26; 95% CI, 1.16–9.16). All but one of the normosmic participants had DAT low putamen SBR within the no DAT deficit range, but they had more limited follow-up (data not shown).

Fig. 2.

Longitudinal DAT imaging in hyposmic α-syn SAA positive and α-syn SAA negative PARS participants. Time 0 reflects the time of acquisition of CSF. Circles (o) refer to time of clinical parkinsonism onset (if time of DAT imaging and clinical parkinsonism onset overlapped). In the two remaining cases, the last imaging visit occurred approximately four years prior to clinical parkinsonism onset.

PARS neurologists blinded to DAT and olfactory status determined that 8 of 34 α-syn SAA positive hyposmics (Table 3) developed a clinical diagnosis of parkinsonism during their follow-up assessments, of whom 7 also had a DAT deficit. The participant with clinical symptoms of parkinsonism without DAT deficit developed clinical symptoms at year 10. This was four years after the last DAT scan so a DAT deficit prior to symptoms may have been missed. There was a higher relative risk (12.83; 95% CI, 1.78–92.37) of clinical manifestations of PD in hyposmic α-syn SAA positive DAT deficit individuals compared to hyposmic α-syn SAA positive individuals without DAT deficit. There was no difference in the change in UPDRS III in α-syn SAA positive hyposmics compared to α-syn SAA negative hyposmics except for those participants diagnosed with clinical symptoms who demonstrated a typical increase in UPDRS associated with clinical diagnosis (Supplementary Fig. S1). None of the α-syn SAA positive hyposmics developed clinical symptoms of other synucleinopathies.

Table 3.

Longitudinal clinical and biomarker outcomes of hyposmic PARS SAA participants.a

| Characteristic | SAA + Hyposmic (N = 34) | SAA- Hyposmic (N = 37) | Estimate (95% CI)b |

|---|---|---|---|

| Median change in UPDRS III score at 2-year visit (IQR)c | 0 (0–3) | 0 (−1 to 1) | 0d |

| Missing data | 4 | 4 | |

| Median change in UPDRS III score at 4-year visit (IQR)c | 2 (0–8) | 0 (−1 to 0) | 2.00 (−0.14 to 4.14) |

| Missing data | 14 | 19 | |

| DAT <70% at any visit — no. (%) | 12 (35) | 4 (11) | 3.26 (1.16–9.16) |

| Clinical Parkinsonism — no. (%)e | 8 (24) | 0 (0) | 18.46 (1.11–308.10) |

IQR denotes interquartile range.

Estimates (median differences for continuous measures, relative risks for categorical measures) and 95% confidence intervals have not been adjusted for multiplicity and should not be used in place of hypothesis testing.

Scores on part III of the Unified Parkinson’s Disease Rating Scale (UPDRS) range from 0 to 108, with higher scores indicating worse motor function.

For point estimates of 0, no confidence intervals are provided.

To compute the relative risk, 0.5 was added to all cells.

None of the α-syn SAA negative hyposmics including those with DAT deficit developed parkinsonism or related synucleinopathy (24% vs. 0%; relative risk, 18.46; 95% CI, 1.11–308.10). Similarly, there were no normosmic participants with clinical symptoms of parkinsonism or related synucleinopathy.

Discussion

The PARS study has previously shown that enriching a community population for olfactory dysfunction increases the likelihood of a DAT deficit and subsequent onset of clinical parkinsonism and related synucleinopathies.1 We now report that PARS participants with hyposmia are at high risk to be CSF α-syn SAA positive, a biomarker for synuclein, the key pathology for PD and related disorders.28 Hyposmia has been associated with CSF α-syn SAA in individuals with PD symptoms.7 These PARS data suggest that olfactory function testing may be a simple and easily accessible tool to enrich for α-syn SAA positive individuals before cognitive or motor symptoms occur.

Extrapolation of the number of hyposmic α-syn SAA positive individuals in our study would suggest that approximately 50 percent of the population over age 60 in the lowest 15th percentile of olfactory function or about 7% of those over 60 may be α-syn SAA positive. While these numbers are substantially higher than estimates of PD prevalence,29 they are consistent with estimates of the prevalence of α-synuclein pathology post mortem in individuals without motor or cognitive symptoms (often known as incidental Lewy body disease (ILBD)) of 3.8% of people in the 6th decade, rising to 12.8% by the 9th decade.30, 31, 32 More directly relevant are data from the Biofinder study showing that 8% of an unimpaired study population aged 70 were CSF α-syn SAA positive.33 The prevalence of synuclein pathology also mirrors the known postmortem age-related increase in amyloid and tau reflected in biofluid and imaging biomarkers studies in individuals without symptoms of dementia.34, 35, 36

Dopamine dysfunction, measured by DAT imaging, is a second key pathology in PD and related disorders.24 Our data show that the majority of hyposmic α-syn SAA positive individuals did not have DAT deficit at CSF α-syn SAA baseline. Longitudinal DAT imaging data further show that most hyposmic α-syn SAA positive individuals without DAT deficit remain in the no DAT deficit category for at least several years. However, about 35% of α-syn SAA positive compared to 11% of α-syn SAA negative hyposmics did have DAT deficit either at baseline and/or demonstrate progressive loss of DAT during longitudinal follow-up. Further, among those with DAT deficit, longitudinal clinical assessment demonstrates that 7 of 12 hyposmic α-syn SAA positive with DAT deficit individuals developed clinical parkinsonism within 10 years of follow-up. All but one of the 8 individuals who developed clinical parkinsonism or related disorders were hyposmic α-syn SAA positive DAT deficit. One individual was hyposmic α-syn SAA positive without DAT deficit, but clinical symptoms arose four years after the last DAT imaging so possibly DAT deficit developed during that four year interval. No hyposmic α-syn SAA negative individuals developed clinical parkinsonism or symptoms of synucleinopathy despite three individuals with DAT deficit at baseline and one developing DAT deficit over time.

The results of this study provide insight into the temporal pattern of alterations in synuclein and DAT biomarkers prior to onset of clinical symptoms of synucleinopathies. Our data demonstrates that many individuals who are α-syn SAA positive do not show DAT deficit. These data suggest acquisition of additional data to further investigate a model in which both synuclein and dopamine pathology are in turn necessary for development of clinical symptoms. More data are required to clarify the timing of synuclein pathology, dopamine pathology and clinical symptoms. It is unclear whether dopamine pathology is always required prior to clinical symptoms, particularly for early cognitive symptoms. The relationship between α-syn SAA status and age needs a larger dataset particularly to determine the age at which synuclein pathology is likely to begin.

Our data showing that hyposmia can be utilized to identify individuals who are likely α-syn SAA positive without clinical symptoms provides an opportunity to develop a screening paradigm for α-syn SAA pathology to rapidly expand the current α-syn SAA pre-symptomatic data. Olfactory function testing is a widely available, relatively inexpensive and easy to administer at-home tool that has already been successfully deployed worldwide to thousands of study participants in PARS and in the Parkinson’s Progression Markers Initiative (PPMI). While the molecular rationale for the relationship between olfactory dysfunction and synuclein pathology is unclear, there is convincing data to show that hyposmia is strongly associated with synuclein pathology. This strategy would allow us to identify the α-syn SAA positive population needed to further investigate a pre-clinical biomarker model for synucleinopathy.37

Studies of α-syn SAA positive hyposmic individuals may also provide insight to the molecular events at the start of synuclein pathology. These studies could elucidate the overall risk and the specific triggers for α-syn SAA positive individuals to develop dopamine pathology and in turn those with synuclein and dopamine pathology to develop clinical motor and/or cognitive symptoms. Identification of α-syn SAA positive individuals offers an opportunity for therapeutic intervention to slow or prevent disease potentially even prior to symptom onset. The availability of a reliable tool to accurately identify early synuclein pathology provides a new roadmap for therapeutic development and will enable further studies to elucidate molecular disease subsets and ultimately more precise therapeutic targets based on disease biology.

We recognize that there are important limitations to this study and to our proposed biomarker screening model. This is a cross-sectional α-syn SAA analysis with a small study sample that is a cohort of convenience with CSF collected several year prior to analysis. The lack of α-syn SAA longitudinal data limits interpretation of the temporal pattern of biomarkers prior to symptoms. The sample reflects a single age range and lacks ethnic and racial diversity. The lack of diversity is a key limitation to generalizing these data and additional studies are required in a broad population. The data suggest but cannot confirm that subgroups including males and older participants may be at particularly high risk to be CSF α-syn SAA positive. The data includes a large number of first-degree family members but with no participants with LRRK2 variants. It appears that first-degree family members may not demonstrate increased risk of DAT deficit or synuclein, but this potential confound limits the interpretation of the results. The timing of α-syn SAA positive and DAT deficit to clinical signs and symptoms is not known, but apparently can take years or may never occur. The current α-syn SAA requires CSF restricting the utility of the assay for screening, although efforts are underway, but not currently independently validated, to enable α-syn SAA to be assayed in skin or blood, both of which would enable widespread use.38, 39, 40, 41 The α-syn SAA data is not quantitative. A quantitative assay may allow monitoring of disease progression and response to therapeutics, but even as a qualitative outcome α-syn SAA provides a valuable measure of synuclein pathology. Finally, misfolded synuclein is very often a component of mixed aggregated protein pathology and the disease characteristics attributable to synuclein pathology may be uncertain. α-syn SAA positive individuals without symptoms but with other pathology may have a different time course and disease characteristics.42 An ultimate goal would be to develop biomarkers to detect both pathology and disease progression associated with the accumulation of multiple proteins, including also amyloid β, tau, and TDP43.

In conclusion, we present data showing that about 50% of older individuals with hyposmia, easily detected using simple tests of olfactory function, but without motor or cognitive symptoms, have synuclein pathology measured by α-syn SAA. While most α-syn SAA positive individuals have neither DAT decifit or clinical symptoms, some α-syn SAA positive individuals also have dopamine pathology and ultimately clinical symptoms of parkinsonism and related synucleinopathies. This study provides the framework for additional research that might lead to a screening paradigm to clarify the prevalence of synuclein pathology, to understand the temporal pattern of biomarker signatures of disease progression and in future to potentially design therapeutic studies to slow or prevent onset of symptoms in individuals with biomarker evidence of parkinsonism and related synucleinopathies.

Contributors

Marek had full access to all of the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. All authors read and approved the final version of the manuscript. Marek, Russell, Concha-Marambio, Stern, Soto and Siderowf contributed to the study concept and design. All authors contributed to drafting and critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content as well as acquisition, analysis, or interpretation of data. Marek, Russell, Concha-Marambio, Choi, Brumm, Coffey, Brown and Siderowf contributed to statistical analysis. Marek and Siderowf acquired funding. Marek, Russell, Concha-Marambio, Seibyl, Soto and Siderowf provided supervision as well as administrative, technical, or material support. All authors had full access to and verified the underlying data.

Data sharing statement

PARS clinical data were obtained in openclinica. The entire PARS dataset including demographic, and longitudinal clinical, biofluid, genetic and imaging data are available as a CSV file upon request to Kenneth Marek (kmarek@indd.org).

Declaration of interests

Marek reports payments to his institution from The Michael J. Fox Foundation and the Department of Defense as well as consulting fees from Invicro, The Michael J. Fox Foundation, Roche, Calico, Coave, Neuron23, Orbimed, Biohaven, Ixico, Koneksa, Merck, Lilly, Inhibikase, Neuramedy, IRLabs, Prothena and Mitro and stock ownership in Mitro, Realm. Russell declares employment at Invicro, LLC. Concha-Marambio declares employment for and employee stock options in Amprion, grants 16712 and 21233 from The Michael J. Fox Foundation to his institution; grant U44NS111672 from NIH to his institution; and patents or patent application numbers US 20210277076A1, US 20210311077A1, US 20190353669A1 and US 20210223268A1. Choi has no disclosures to report. Jennings declares employment for and employee stock options from Denali Therapeutics. Brumm declares travel grants and payments to his institution from The Michael J. Fox Foundation. Coffey declares grants to his institution from The Michael J. Fox Foundation and NIH/NINDS. Brown declares grant support to his institution from The Michael J. Fox Foundation, National Institute of Health and Gateway LLC, consulting fees from Guidepoint Consulting, and travel support for meeting attendance from The Michael J. Fox Foundation. Seibyl declares consultancies from Invicro, Biogen, and Abbvie; and stock ownership from RealmIDX, MNI Holdings, and LikeMinds as well as grants from The Michael J. Fox Foundation. Stern declares consultancies for Mediflix, Inc., Health and Wellness Partners; Neurocrine, Luye Pharma and Acorda; honoraria from Atria Foundation, International Parkinsons and Movement Disorder Society; serves on advisory board at Neuroderm, Alexza, Alexion and Biogen. Soto declares employment for Amprion; stock ownership for Amprion; honoraria (will receive royalties for the sale of seed amplification assay [SAA]) from Amprion; and patents or patent applications, awarded and amplified in conjunction with Amprion for the SAA assay, NIH grants RO1AG055053, U24AG079685, RO1AG079685. Siderowf declares consultancies for SPARC Therapeutics, Capsida Therapeutics and Parkinson Study Group; honoraria from Bial; grants from National Institutes of Health and The Michael J. Fox Foundation (member of PPMI Steering Committee); and participation on board at Wave Life Sciences, Inhibikase, Prevail, Huntington Study Group and Massachusetts General Hospital.

Acknowledgements

The study was funded by the U.S. Department of Defense, the Helen Graham Foundation and the Michael J. Fox Foundation for Parkinson’s Research.

Footnotes

Supplementary data related to this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ebiom.2025.105567.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

References

- 1.Jennings D., Siderowf A., Stern M., et al. Conversion to Parkinson disease in the PARS hyposmic and dopamine transporter–deficit prodromal cohort. JAMA Neurol. 2017;74(8):933–940. doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2017.0985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Horimoto Y., Matsumoto M., Nakazawa H., et al. Cognitive conditions of pathologically confirmed dementia with Lewy bodies and Parkinson's disease with dementia. J Neurol Sci. 2003;216(1):105–108. doi: 10.1016/s0022-510x(03)00220-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Savica R., Rocca W.A., Ahlskog J.E. When does Parkinson disease start? Arch Neurol. 2010;67(7):798–801. doi: 10.1001/archneurol.2010.135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rossi M., Candelise N., Baiardi S., et al. Ultrasensitive RT-QuIC assay with high sensitivity and specificity for Lewy body-associated synucleinopathies. Acta Neuropathol. 2020;140(1):49–62. doi: 10.1007/s00401-020-02160-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Postuma R.B., Iranzo A., Hu M., et al. Risk and predictors of dementia and parkinsonism in idiopathic REM sleep behaviour disorder: a multicentre study. Brain. 2019;142(3):744–759. doi: 10.1093/brain/awz030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Iranzo A., Fairfoul G., Ayudhaya A.C.N., et al. Detection of α-synuclein in CSF by RT-QuIC in patients with isolated rapid-eye-movement sleep behaviour disorder: a longitudinal observational study. Lancet Neurol. 2021;20(3):203–212. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(20)30449-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Siderowf A., Concha-Marambio L., Lafontant D.-E., et al. Assessment of heterogeneity among participants in the Parkinson's Progression Markers Initiative cohort using α-synuclein seed amplification: a cross-sectional study. Lancet Neurol. 2023;22(5):407–417. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(23)00109-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Crotty G.F., Keavney J.L., Alcalay R.N., et al. Planning for prevention of Parkinson disease: now is the time. Neurology. 2022;99(7 Suppl 1):1–9. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000200789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rajan S., Kaas B. Parkinson's disease: risk factor modification and prevention. Semin Neurol. 2022;42(5):626–638. doi: 10.1055/s-0042-1758780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Concha-Marambio L., Pritzkow S., Shahnawaz M., Farris C.M., Soto C. Seed amplification assay for the detection of pathologic alpha-synuclein aggregates in cerebrospinal fluid. Nat Protoc. 2023;18(4):1179–1196. doi: 10.1038/s41596-022-00787-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bongianni M., Ladogana A., Capaldi S., et al. α-Synuclein RT-QuIC assay in cerebrospinal fluid of patients with dementia with Lewy bodies. Ann Clin Transl Neurol. 2019;6(10):2120–2126. doi: 10.1002/acn3.50897. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fairfoul G., McGuire L.I., Pal S., et al. Alpha-synuclein RT-Qu IC in the CSF of patients with alpha-synucleinopathies. Ann Clin Transl Neurol. 2016;3(10):812–818. doi: 10.1002/acn3.338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shahnawaz M., Tokuda T., Waragai M., et al. Development of a biochemical diagnosis of Parkinson disease by detection of α-synuclein misfolded aggregates in cerebrospinal fluid. JAMA Neurol. 2017;74(2):163–172. doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2016.4547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Arnold M.R., Coughlin D.G., Brumbach B.H., et al. Alpha-synuclein seed amplification in CSF and brain from patients with different brain distributions of pathological alpha-synuclein in the context of Co-pathology and non-LBD diagnoses. Ann Neurol. 2022;92(4):650–662. doi: 10.1002/ana.26453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Concha-Marambio L., Weber S., Farris C.M., et al. Accurate detection of alpha-synuclein seeds in cerebrospinal fluid from isolated rapid eye movement sleep behavior disorder and patients with Parkinson's disease in the DeNovo Parkinson (DeNoPa) cohort. Mov Disord. 2023;38(4):567–578. doi: 10.1002/mds.29329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Siderowf A., Jennings D., Eberly S., et al. Impaired olfaction and other prodromal features in the Parkinson At-Risk Syndrome Study. Mov Disord. 2012;27(3):406–412. doi: 10.1002/mds.24892. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jennings D., Siderowf A., Stern M., et al. Imaging prodromal Parkinson disease: the Parkinson associated risk syndrome study. Neurology. 2014;83(19):1739–1746. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000000960. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Petrovitch H., Abbott R.D., Ross G.W., et al. Bowel movement frequency in late-life and substantia nigra neuron density at death. Mov Disord. 2009;24(3):371–376. doi: 10.1002/mds.22360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ross G.W., Abbott R.D., Petrovitch H., Tanner C.M., White L.R. Pre-motor features of Parkinson's disease: the honolulu-Asia aging study experience. Parkinsonism Relat Disord. 2012;18(Suppl 1):S199–S202. doi: 10.1016/S1353-8020(11)70062-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Heinzel S., Berg D., Gasser T., Chen H., Yao C., Postuma R.B. Update of the MDS research criteria for prodromal Parkinson's disease. Mov Disord. 2019;34(10):1464–1470. doi: 10.1002/mds.27802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fahn S., Elton R.L. In: Recent developments in Parkinson's disease. Fahn S., Marsden C.D., Calne D., Goldstein M., editors. Macmillan Health Care Information; Florham Park, NJ: 1987. Unified Parkinson's disease rating scale; pp. 153–164. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Folstein M.F., Folstein S.E., McHugh P.R. Mini-mental state: a practical method for grading the cognitive state of subjects for the clinician. J Psychiatr Res. 1975;12:189–198. doi: 10.1016/0022-3956(75)90026-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nalls M.A., McLean C.Y., Rick J., et al. Diagnosis of Parkinson's disease on the basis of clinical and genetic classification: a population-based modelling study. Lancet Neurol. 2015;14(10):1002–1009. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(15)00178-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Seibyl J.P., Marek K., Sheff K., et al. Iodine-123-beta-CIT and iodine-123-FPCIT SPECT measurement of dopamine transporters in healthy subjects and Parkinson's patients. J Nucl Med. 1998;39(9):1500–1508. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Marek K., Seibyl J., Eberly S., et al. Longitudinal follow-up of SWEDD subjects in the PRECEPT Study. Neurology. 2014;82(20):1791–1797. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000000424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Siderowf A., Jennings D., Stern M., et al. Clinical and imaging progression in the PARS cohort: long-term follow-up. Mov Disord. 2020;35(9):1550–1557. doi: 10.1002/mds.28139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bellomo G., Toja A., Paolini Paoletti F., et al. Investigating alpha-synuclein co-pathology in Alzheimer's disease by means of cerebrospinal fluid alpha-synuclein seed amplification assay. Alzheimers Dement. 2024;20(4):2444–2452. doi: 10.1002/alz.13658. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Braak H., Del Tredici K., Rub U., de Vos R.A., Jansen Steur E.N., Braak E. Staging of brain pathology related to sporadic Parkinson's disease. Neurobiol Aging. 2003;24(2):197–211. doi: 10.1016/s0197-4580(02)00065-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Van Den Eeden S.K., Tanner C.M., Bernstein A.L., et al. Incidence of Parkinson's disease: variation by age, gender, and race/ethnicity. Am J Epidemiol. 2003;157(11):1015–1022. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwg068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gibb W.R., Lees A.J. The relevance of the Lewy body to the pathogenesis of idiopathic Parkinson's disease. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1988;51:745–752. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.51.6.745. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Adler C.H., Connor D.J., Hentz J.G., et al. Incidental Lewy body disease: clinical comparison to a control cohort. Mov Disord. 2010;25(5):642–646. doi: 10.1002/mds.22971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ross G.W., Abbott R.D., Petrovitch H., et al. Association of olfactory dysfunction with incidental Lewy bodies. Mov Disord. 2006;21(12):2062–2067. doi: 10.1002/mds.21076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Palmqvist S., Rossi M., Hall S., et al. Cognitive effects of Lewy body pathology in clinically unimpaired individuals. Nat Med. 2023;29(8):1971–1978. doi: 10.1038/s41591-023-02450-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Beach T.G. A history of senile plaques: from alzheimer to amyloid imaging. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 2022;81(6):387–413. doi: 10.1093/jnen/nlac030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rodrigue K.M., Kennedy K.M., Devous MD, Sr., et al. beta-Amyloid burden in healthy aging: regional distribution and cognitive consequences. Neurology. 2012;78(6):387–395. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e318245d295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Strikwerda-Brown C., Hobbs D.A., Gonneaud J., et al. Association of elevated amyloid and tau positron emission tomography signal with near-term development of alzheimer disease symptoms in older adults without cognitive impairment. JAMA Neurol. 2022;79(10):975–985. doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2022.2379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Simuni T., Chahine L.M., Poston K., et al. A biological definition of neuronal α-synuclein disease: towards an integrated staging system for research. Lancet Neurol. 2024;23(2):178–190. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(23)00405-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kluge A., Bunk J., Schaeffer E., et al. Detection of neuron-derived pathological alpha-synuclein in blood. Brain. 2022;145(9):3058–3071. doi: 10.1093/brain/awac115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kuzkina A., Rossle J., Seger A., et al. Combining skin and olfactory alpha-synuclein seed amplification assays (SAA)-towards biomarker-driven phenotyping in synucleinopathies. NPJ Parkinsons Dis. 2023;9(1):79. doi: 10.1038/s41531-023-00519-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Okuzumi A., Hatano T., Matsumoto G., et al. Propagative α-synuclein seeds as serum biomarkers for synucleinopathies. Nat Med. 2023;29(6):1448–1455. doi: 10.1038/s41591-023-02358-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wang Z., Becker K., Donadio V., et al. Skin α-synuclein aggregation seeding activity as a novel biomarker for Parkinson disease. JAMA Neurol. 2020;78(1):1–11. doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2020.3311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Quadalti C., Palmqvist S., Hall S., et al. Clinical effects of Lewy body pathology in cognitively impaired individuals. Nat Med. 2023;29(8):1964–1970. doi: 10.1038/s41591-023-02449-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.