Abstract

Reversible electroporation (EP) refers to the use of high-voltage electrical pulses on tissues to increase cell membrane permeability. It allows targeted delivery of high concentrations of chemotherapeutic agents including cisplatin and bleomycin, a process known as electrochemotherapy (ECT). It can also be used to deliver toxic concentrations of calcium and gene therapies that stimulate an anti-tumour immune response. ECT was validated for palliative treatment of cutaneous tumours. Evidence to date shows a mean objective response rate of ∼80% in these patients. Regression of non-treated lesions has also been demonstrated, theorized to be from an in situ vaccination effect. Advances in electrode development have also allowed treatment of deep-seated metastatic lesions and primary tumours, with safety demonstrated in vivo. Calcium EP and combination immunotherapy or immunogene electrotransfer is also feasible, but research is limited. Adverse events of ECT are minimal; however, general anaesthesia is often necessary, and improvements in modelling capabilities and electrode design are required to enable sufficient electrical coverage. International collaboration between preclinical researchers, oncologists, and interventionalists is required to identify the most effective combination therapies, to optimize procedural factors, and to expand use, indications and assessment of reversible EP. Registries with standardized data collection methods may facilitate this.

Keywords: reversible, electroporation, electrochemotherapy, electropermeabilisation, electrotransfer, immunotherapy, ablation, intervention, oncology, calcium

Introduction

Electroporation (EP) refers to the targeted use of high-voltage electrical pulses on tissues to increase cell membrane permeability. It may be “irreversible” or “reversible”: the former has permanent effects on cellular homeostasis and leads to apoptosis, while the latter causes transient change to allow intracellular migration of large molecules or hydrophilic compounds.1 Electrochemotherapy (ECT) refers to the specific use of reversible EP to provide targeted delivery of chemotherapeutic agents to tumours, with clinical efficacy first demonstrated for head and neck cancer in the early 1990s.2

ECT is most established in the palliative treatment of cutaneous and subcutaneous tumours. The updated European Standards of Practice for Electrochemotherapy (ESOPE) published in 2018 defined the key indications for ECT, including the treatment of symptomatic cutaneous metastases or refractory primary skin tumours.3 However, ECT is increasingly being used for the treatment of deep-seated primary and metastatic solid tumours, with a review in 2023 identifying early-stage studies of ECT on liver, kidney, pancreas, bone, and gastric tumours.4 Additionally, reversible EP is now being used to deliver alternative anti-tumoural therapies, with strategies such as calcium EP and gene electrotransfer.5

This article provides a narrative review of the theoretical basis, practical considerations, and clinical evidence base of reversible EP and associated anti-tumoural therapies. Information is collated from the most recent and relevant review articles (Table 1) with much of the primary evidence derived from small, early stage-clinical trials, although some larger cohort studies have investigated ECT in cutaneous and certain deep-seated tumours.

Table 1.

A summary of key reviews on reversible electroporation for cancer therapy.

| Review focus | Review title | Year of publication |

|---|---|---|

| Electrochemotherapy |

|

2022 |

|

2023 | |

|

2023 | |

| Calcium electroporation | A comprehensive review of calcium electroporation—a novel cancer treatment modality.8 | 2020 |

| Gene electrotransfer and immunotherapy | Electrochemotherapy combined with immunotherapy—a promising potential in the treatment of cancer.9 | 2023 |

| Research directions | Pulsed electric fields in oncology: a snapshot of current clinical practices and research directions from the 4th World Congress of Electroporation.10 | 2023 |

Theoretical basis

The prevailing theory of reversible EP is that external electric fields induce a voltage across cell membranes that leads to the incorporation of water molecules within their lipid bilayer and the formation of nanopores. Pore resealing takes several orders of magnitude longer than pore formation, creating a window for transmembrane mass transport, with cancer cells resealing more slowly than normal cells in vitro.11 If the resealing is too slow, or there is excess mass transport, then cell death can occur (irreversible EP). Higher field strengths and pulse durations increase the likelihood of irreversible effects, and cell size and cell medium can also affect this probability.12 Importantly, some effects of EP on cell membranes are mediated by direct effects on membrane lipids and transmembrane proteins, rather than the movement of water molecules.13 This process is summarized in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

An illustration of the theoretical basis of reversible and irreversible EP. Abbreviation: EP = electroporation.

Bleomycin and cisplatin are the only well-established chemotherapeutic agents that demonstrate increased toxicity when delivered by reversible EP.14 Both drugs are poorly permeable under normal circumstances but have high intrinsic cytotoxicity and a high therapeutic index when used in ECT—bleomycin toxicity is increased almost 800-fold, while cisplatin toxicity is increased 80-fold.15 Bleomycin is most used clinically and may be more useful than cisplatin in radiotherapy resistant tumours16 although it may be less effective than cisplatin in cancers associated with human papilloma virus.17

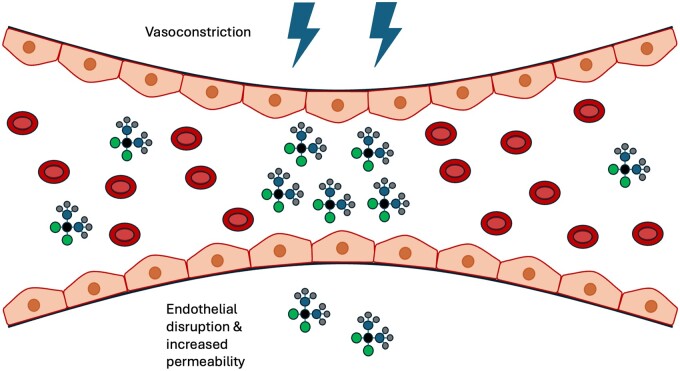

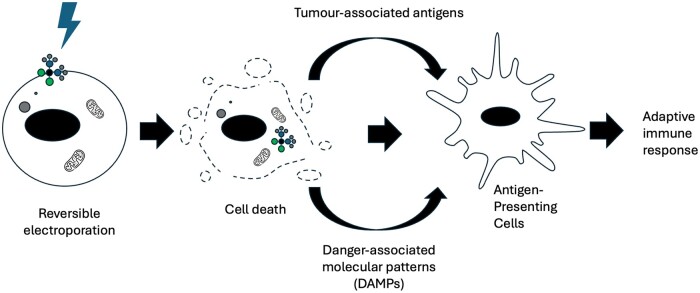

Notably, chemotherapeutic toxicity of ECT in vivo is greater than that seen in vitro, which has been attributed to additional vascular and immune effects of ECT.18 Specifically, ECT disrupts tumour vascular endothelial cells and induces vasoconstriction that reduces both tumour blood flow and drug washout, increasing local chemotherapeutic concentration (a “vascular-lock” effect) as shown in Figure 2.18 ECT also induces T-cell dependent tumour cell death by stimulating the release of damage-associated molecular patterns and tumour associated antigens, establishing an anti-tumoural immune response as shown in Figure 3.21 This may be necessary for treatment success; a study of ECT in mice found that curability was not achieved in immunodeficient mice, with tumour growth delay being half as long compared to immunocompetent mice.21 The anti-tumoural immune response may additionally explain abscopal effects—systemic anti-cancer effects following localized treatments—which have occasionally been observed in ECT studies.22 These effects have been more extensively documented in localized radiotherapy, where an immune-mediated mechanism is similarly thought to be the underlying cause.23

Figure 2.

A depiction of the “vascular lock” phenomenon, whereby the electric field applied during ECT causes vasoconstriction that reduces tumour blood flow and decreases drug washout. It also disrupts endothelial cells, increasing delivery of chemotherapeutic agents.18 Figure adapted from Jenkins et al19 under Creative Commons license BY 4.0. Abbreviation: ECT = electrochemotherapy.

Figure 3.

A summary of the process by which ECT establishes an anti-tumoural immune response. Cell death induced by ECT results in the recruitment and activation of antigen-presenting cells through the release of damage-associated molecular patterns and tumour-associated antigens. These cells subsequently stimulate an adaptive anti-tumoural immune response.20 Abbreviation: ECT = electrochemotherapy.

Gene electrotransfer and calcium EP are emerging treatment methods built upon the early evidence of ECT. They respectively refer to the use of reversible EP to deliver gene therapies and toxic concentrations of calcium to tissues. In cancer treatment, gene electrotransfer is most commonly used to develop innate and adaptive anti-tumoural immune responses by delivery of immune-stimulating cytokines (e.g. interleukin-12) and checkpoint-inhibiting antibodies, sometimes in combination with bleomycin or cisplatin.5,24 Conversely, calcium EP induces ATP depletion and selective cancer cell death by leveraging altered calcium homeostasis in cancer cells. It also benefits from similar vascular and immune effects as traditional ECT.8,25 Notably, calcium EP is non-mutagenic, relatively inexpensive, and may have fewer treatment-related adverse events (ulceration, exudation, itching, hyper-pigmentation) compared to treatment with bleomycin.26

Practical considerations

The ESOPE published in 2006 provided the first practical framework for reversible EP therapy, specifically for ECT of cutaneous and subcutaneous tumours smaller than 3 cm.27 It provided numerous practical protocols, all of which involved administration of bleomycin or cisplatin followed by a series of electrical pulses (8 pulses at 100 microseconds each) delivered by electrodes inserted into the tumour. Plate or needle row electrodes were recommended for smaller, superficial nodules, and hexagonal needle electrodes were recommended for larger nodules due to better coverage (albeit a higher risk of hyper-pigmentation). General anaesthetic was preferred over local anaesthetic if multiple nodules or nodules larger than 0.8 cm were being treated. As the evidence base for ECT expanded, the ESOPE guidelines were updated in 2018 to include guidance for superficial tumours larger than 3 cm.3

The guidelines do not yet include the use of variable electrode geometry electrodes, which allow the treatment of deep-seated tumours through adjustable axial displacement.28 These treatments are usually performed under image guidance and require both modelling and individualized treatment planning to determine the electrode positions that provide the required electrical field coverage and distribution.29 Newer pulse generators also allow the electrical field to be varied according to tumour size and geometry.30 Unfortunately, variations in electrical conductivity in different tissues and in regions affected by necrosis, vasculature, and micro-heterogeneities can limit the reliability of numerical models, reducing the accuracy of electrode positioning and subsequent clinical success of treatment.31

Compared to other minimally invasive oncological treatments such as radiofrequency ablation, ECT is a non-thermal technique that does not damage surrounding organs or vessels.28 However, ECT procedures can be of longer duration, limiting utility for multifocal tumours. Additionally, side effects from the chemotherapeutic agents used in ECT (eg, bleomycin-induced pulmonary fibrosis) may occur despite use of relatively small doses, and there are theoretical risks of arrhythmia induction if ECT is performed close to the heart, although this may be mitigated by electrocardiogram synchronization.32

Research to optimize ECT protocols is ongoing. Recent studies favour nanosecond electrical pulses over microsecond pulses due to proposed advantages including reduced muscle contraction during treatment delivery, less thermal damage to tissues, and less electrolysis of electrodes.33 Moreover, ECT success likely depends upon histological tumour type34 which does not yet factor in ECT protocols. Trials have also demonstrated the feasibility of lowering the bleomycin dose currently used in ECT to reduce the risk of side effects, particularly in older patients or those with impaired renal or respiratory function.6

Evidence base

Figure 4 provides an approximate timeline of the evidence base around reversible EP for cancer therapy. Neuman and Rosenheck35 first demonstrated a transient increase in cell membrane permeability following electrical pulse administration in vitro in 1972. Mir et al2 then performed the first clinical trial of ECT in 8 patients with head and neck squamous cell cancer in 1991, treating 40 nodules with a complete clinical response rate of 57%. Numerous studies have since evaluated the effectiveness of ECT for: cutaneous and subcutaneous tumours, deep-seated metastatic malignancies, and deep-seated primary tumours. Studies have also evaluated calcium EP, immunotherapy, and gene electrotransfer for cancer therapy. The evidence base of these treatments has been evaluated below, with a focus on human trials.

Figure 4.

A timeline of research on reversible electroporation for cancer therapy.

Cutaneous and subcutaneous metastasis

Following the first trial by Mir et al,2 several early-stage clinical trials evaluated the feasibility and optimal dosage of ECT for various cutaneous and subcutaneous tumours, primarily malignant melanoma. This culminated in the publication of the first ESOPE guidelines in 2006 which standardized treatment protocols.36 The protocols were validated with a prospective study on 41 patients with progressive cutaneous and subcutaneous metastases. Results showed an objective response rate of 85% (at least partial tumour reduction) and a complete response rate of 74% (total tumour eradication). Minimal adverse events were reported.36

Subsequent studies corroborated those results. A systematic review published in 2022 identified 55 studies evaluating ECT with intravenous bleomycin on patients with cutaneous malignancies.6 The mean objective response rate in all 3729 patients was determined to be 81.9%. Only 1 patient had a serious adverse event related to ECT (sepsis post-treatment in a patient with a large ulcerated tumour37) the only other adverse events described included mild pain and skin hyperpigmentation. A significant proportion of studies included in this review were part of the influential International Network for Sharing Practice in ECT (INSPECT) pan-European Collaborative which prospectively collected data on the use of ECT for cutaneous malignancy over 11 years.38

Importantly, these studies highlighted numerous factors that influence response rate, including tumour size, histological type, number of lesions, previous radiotherapy, and number of electrode applications and ECT cycles. In particular, larger tumours which had been previously irradiated showed reduced responses to ECT, theorized to be due to disrupted vasculature in irradiated tissues reducing chemotherapeutic uptake and fibrotic skin reducing current delivery.6

Questions remain regarding the impact of ECT on quality of life which is of particular importance in treatments with palliative intent. One study which assessed quality of life in 378 patients with melanoma treated with ECT found no significant change following treatment.39 Additionally, there is minimal data directly comparing the effectiveness of ECT to alternative palliative treatments for cutaneous and subcutaneous tumours such as radiotherapy, isolated limb perfusion, intralesional therapies, or systemic chemotherapy. Notably, ECT only requires a single treatment session and is relatively cost- and time-efficient,40 however, multifocal tumour ECT treatments may necessitate prolonged treatment times compared to other ablative treatments.10

Deep-seated tumours

Since the first study investigating the use of ECT on colorectal liver metastases in 2011,41 the safety and feasibility of ECT for a variety of deep-seated tumours (primarily palliative or treatment-refractory tumours) has been investigated extensively, as summarized in a recent systematic review.10

Importantly, challenges of ECT described previously are more pronounced in the treatment of deep-seated tumours, with conductivity variations, electrode positioning, cardiac synchronization, and the need for general anaesthesia being particularly relevant.42,43 Some of the key evidence has been highlighted below, with unique factors for intra-abdominal tumours, bone tumours, and endoluminal treatments.

Intra-abdominal tumours

Intra-abdominally, ECT has been used most extensively in the treatment of metastatic and locally advanced hepatic malignancy,4 with evidence highlighting a good safety profile despite complex anatomy and frequent associations with parenchymal disease.43,44 Indeed, studies have investigated both percutaneous and intraoperative treatment, and shown feasibility of ECT for hepatocellular carcinoma, cholangiocarcinoma, colorectal liver metastases, and other metastases.10 A 2023 systematic review identified 8 studies investigating the effect of ECT on primary and secondary liver malignancies, the largest of which included treatment of 39 liver tumours.7 Reported complete response rates varied widely from 55% to 100%. The review highlighted the absence of risk to large vessels (>5 mm) and bile ducts after ECT treatment, reinforcing the evidence from animal studies that ECT does not affect the function or architecture of larger tumour vessels or healthy liver parenchyma.45 This contrasts with existing thermal and non-thermal ablation techniques with which ECT has comparable effectiveness.7 While transarterial chemoembolization may be used in similar patient cohorts and allows locally controlled chemotherapy, it does not enhance chemotherapeutic drug uptake.43

Pancreatic adenocarcinoma and renal cell carcinoma have also been investigated, but on a much smaller scale. Two studies investigated the feasibility of ECT for locally advanced pancreatic adenocarcinoma using an open surgical approach and reported no serious adverse events.46,47 A few small studies trialled ECT for stage 3 advanced and stage 4 metastatic pancreatic adenocarcinoma, but response rates were variable, although results suggested improvements in quality of life.48–51 ECT of stage 3 renal cell carcinoma has been described separately in 2 individual case reports with complete response on post-treatment CT imaging; however, treatment was not standardized.52,53 There remains little evidence for ECT in these tumours, and further research is required before clinical adoption.

Bone tumours

Bone tumours are relatively rare and can be difficult to treat with ECT if located in the vertebrae due to the need for the active tips of electrodes to be parallel to each other.54 However, ECT of bone metastases is of particular interest because of their associated pain, either from nerve compression, fractures, or impaired mobility.10 One study of ECT in 38 patients with bone metastases demonstrated an objective response rate in 29% and disease stabilization in 59% of subjects.54 Another study found a significant decrease in pain in 23/29 subjects with bone metastasis, with a median visual numeric scale pain control score reduction of 2.3.55 Unlike other treatments, ECT does not cause bone necrosis and therefore preserves bone architecture, mechanical stability and healing capability in case of fracture or need for surgical intervention.54 However, it cannot be performed if any metal implants are in place.

Endoluminal ECT

Endoscopic ECT is being explored for oesophageal and colorectal cancer, with phase 1 studies in 2018 and 2020 showing promise.56,57 Both used the EndoVE® device (Mirai Medical, Galway, Ireland) and demonstrated feasibility and safety of treatment, although there were issues with tumour coverage. The device used consisted of electrodes attached to an endoscope—tumour tissue was brought into contact with the electrodes by use of a vacuum. Newer devices such as the Stinger® device (IGEA S.p.A., Modena, Italy) have since been developed and investigated.58 If electrode positioning can be optimized for complete tumour coverage, endoluminal ECT may hold significant promise.

Calcium electroporation

Calcium EP was first tested in humans in 2017 in a phase 2 study of 7 patients with a total of 47 cutaneous metastatic lesions.26 Metastases were randomized to receive calcium EP or ECT with intratumoural bleomycin in a test of non-inferiority, with a threshold of a 15% difference in response rates. No statistically significant difference was found between the treatments with objective response rates for calcium EP and ECT being 72% and 84%, respectively. Both treatments were less successful in tumours that had previously been irradiated, and calcium EP was associated with less adverse hyperpigmentation than ECT. Abscopal effects were also noted in one patient with malignant melanoma who received both ECT and calcium EP for metastatic lesions, with complete remission of malignancy 9 months after treatment.

Non-inferiority of calcium EP to ECT was confirmed in another phase 2 trial with 7 patients in 2020 (with a threshold of 20% response rate difference)59 and subsequent studies have demonstrated the feasibility of calcium EP in the treatment of advanced oesophageal cancer,60 colorectal cancer,61 recurrent head and neck cancer,62 and cutaneous manifestations of gynaecological cancers63 albeit with mixed tumour responses. A larger-scale superiority trial comparing calcium EP against ECT is required to determine the precise utility of calcium EP. If suitably effective, it may provide a viable alternative to ECT and may be associated with fewer cosmetic side effects, lower costs, and less storage/handling difficulty.

Gene electrotransfer and immunotherapy

In 2008, Daud et al64 tested gene electrotransfer of an immune-stimulating IL-12 plasmid in a phase 1 trial of 24 patients with malignant melanoma, which otherwise had significant toxicity concerns when delivered systemically. Two patients demonstrated complete cancer regression (including non-treated lesions), while another 8 patients had a partial response to therapy. Transient pain was the only recorded adverse event. A marked CD4+ CD8+ infiltrate was demonstrated on biopsy, indicative of anti-tumoural immune response generation.

A subsequent phase 2 trial in patients with melanoma65 and other trials of IL-12 EP for the treatment of Merkel cell carcinoma66 and triple-negative breast tumours67 confirmed safety of treatment with partial tumour responses. The latter trial highlighted how IL-12 increases tumour antigen presentation and T-cell response, and also sensitizes cells to treatment with anti-PD-1/anti-PD-L1 immune checkpoint inhibitors. This was demonstrated clinically in the same study; one patient who had previously been resistant to anti-PD-1/anti-PD-L1 therapy demonstrated response to this therapy following IL-12 EP. Combination treatment (anti-PD-1/anti-PD-L1 therapy and IL-12 gene electrotransfer) was therefore directly tested in a phase 2 trial of patients with metastatic melanoma.68 Combined IL-12 and anti-PD-1 therapy significantly increased tumour immune infiltration and resulted in an anti-tumoural immune response with an objective response rate of 41%.

Immunotherapies have been also tested with ECT, independent from gene electrotransfer. ECT is thought to generate an anti-tumoural immune response which has been dubbed a form of “in situ vaccination”, and may be enhanced by checkpoint inhibitors (anti-CTLA4 or anti-PD-1).69 A 2023 review identified 7 studies which had investigated such effects on cancers including melanoma, breast cancer, hepatocellular carcinoma, and squamous cell carcinoma.9 Studies on melanoma and breast cancer that compared effectiveness of ECT combined with immunotherapy demonstrated increased efficacy of ECT with immunotherapy compared to either therapy alone. However, the studies included small numbers of participants and were not randomized.

This area remains a very active field of research, with pre-clinical studies investigating gene electrotransfer of other cytokines such as TNFα and IL-25 and combination therapy of calcium EP and cytokine gene electrotransfer.70 Gene electrotransfer has also been investigated as a means for the delivery of cancer-specific antigens as a form of DNA vaccine, particularly for urological cancers.71

Conclusions and future directions

The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) in the United Kingdom approved the use of ECT for the palliative treatment of cutaneous and subcutaneous metastases in 2013.72 Evidence since then suggests that reversible EP cancer therapies are a safe treatment option even for primary deep-seated tumours and may be particularly effective when combined with immunotherapies and gene electrotransfer to take advantage of the abscopal effect. A greater understanding of the most effective combination therapies and protocols for different tumour histotypes may enable use of reversible EP as an adjuvant or neoadjuvant tumour therapy outside of the palliative setting, particularly if biomarkers can identify those most likely to respond to treatment. This may facilitate individualized treatments whereby combination reversible EP therapies are personalized to a patient’s tumour factors and likelihood of response. In 2021, Falk et al developed a research roadmap highlighting potential biological factors that may predict response to ECT, including specific tumour cell characteristics and tumour microenvironment factors.69

There remains scope to optimize reversible EP protocols and techniques. Use of nanosecond electrical pulses, calcium EP and lower bleomycin doses in ECT may reduce the rare adverse events associated with reversible EP therapies. Conscious sedation may provide a feasible and more accessible alternative to general anaesthesia in the treatment of multiple/larger tumours in specific cases, as demonstrated by a recent small prospective study.73 In vivo experiments are also ongoing to improve models of electrical field distribution in heterogenous tissues, such as a 2023 study which developed a model that can account for temperature variation and non-parallel electrodes.74 It may even be possible to monitor and adjust EP therapies in real-time using techniques such as rapid impedance spectroscopy.75 Many of these key research directions were highlighted and categorized following the World Congress on Electroporation in 2022, with the subsequent collaborative publication providing a good summary of the limitations of evidence to date.10

International collaboration between medical device developers, preclinical scientists, oncologists and interventional radiologists is needed to focus efforts on the most promising treatment protocols and combination therapies in the field, particularly looking at the treatment of deep-seated tumours, where reversible EP has significant advantages over current minimally invasive treatment methods. Increased awareness of reversible EP therapies among oncologists and referring clinicians will also increase the volume of reversible EP cases available for analysis. Ideally, cases should be recorded in an international registry with standardized data collection and reporting methods, like the previously described InspECT registry.39 This will enable validation of proposed protocols through large-scale observational studies with reduced heterogeneity, which may in turn justify comparative trials that evaluate reversible EP therapies against existing palliative and adjuvant or neoadjuvant therapies. A multicentre European observational study has already been established to assess the effectiveness of percutaneous ECT for primary or secondary liver cancer, with data being collected in the RESPECT (REgiStry for Percutaneous ElectroChemoTherapy) registry.76 The primary endpoint is to assess local tumour control 12 months after treatment, with a view to including 250 patients. This collaboration is an important first step in providing broader validation for reversible EP therapies.

Contributor Information

Taha Shiwani, Department of Diagnostic and Interventional Radiology, St. James’s University Hospital, Leeds Teaching Hospitals NHS Trust, Beckett St, Leeds, LS9 7TF, United Kingdom.

Simran Singh Dhesi, Department of Diagnostic and Interventional Radiology, St. James’s University Hospital, Leeds Teaching Hospitals NHS Trust, Beckett St, Leeds, LS9 7TF, United Kingdom.

Tze Min Wah, Department of Diagnostic and Interventional Radiology, St. James’s University Hospital, Leeds Teaching Hospitals NHS Trust, Beckett St, Leeds, LS9 7TF, United Kingdom.

Funding

None declared.

Conflicts of interest

None declared.

References

- 1. Aycock KN, Davalos RV. Irreversible electroporation: background, theory, and review of recent developments in clinical oncology. Bioelectricity. 2019;1(4):214-234. 10.1089/bioe.2019.0029 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Mir LM, Belehradek M, Domenge C, et al. Electrochemotherapy, a new antitumor treatment: first clinical trial. C R Acad Sci III. 1991;313(13):613-618. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Gehl J, Sersa G, Matthiessen LW, et al. Updated standard operating procedures for electrochemotherapy of cutaneous tumours and skin metastases. Acta Oncol. 2018;57(7):874-882. 10.1080/0284186X.2018.1454602 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Martin CH, Martin RCG. Optimal dosing and patient selection for electrochemotherapy in solid abdominal organ and bone tumors. Bioengineering. 2023;10(8):975. 10.3390/bioengineering10080975 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Calvet CY, Mir LM. The promising alliance of anti-cancer electrochemotherapy with immunotherapy. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 2016;35(2):165-177. 10.1007/s10555-016-9615-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Bastrup FA, Vissing M, Gehl J. Electrochemotherapy with intravenous bleomycin for patients with cutaneous malignancies, across tumour histology: a systematic review. Acta Oncol. 2022;61(9):1093-1104. 10.1080/0284186X.2022.2110385 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Granata V, Fusco R, D'Alessio V, et al. Percutanous electrochemotherapy (ECT) in primary and secondary liver malignancies: a systematic review. Diagnostics (Basel). 2023;13(2):209. 10.3390/diagnostics13020209 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Frandsen SK, Vissing M, Gehl J. A comprehensive review of calcium electroporation—a novel cancer treatment modality. Cancers (Basel). 2020;12(2):290. 10.3390/cancers12020290 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Hadzialjevic B, Omerzel M, Trotovsek B, et al. Electrochemotherapy combined with immunotherapy—a promising potential in the treatment of cancer. Front Immunol. 2023;14:1336866. 10.3389/fimmu.2023.1336866 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Campana LG, Daud A, Lancellotti F, et al. Pulsed electric fields in oncology: a snapshot of current clinical practices and research directions from the 4th World Congress of Electroporation. Cancers (Basel). 2023;15(13):3340. 10.3390/cancers15133340 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Frandsen SK, McNeil AK, Novak I, McNeil PL, Gehl J. Difference in membrane repair capacity between cancer cell lines and a normal cell line. J Membr Biol. 2016;249(4):569-576. 10.1007/s00232-016-9910-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Yarmush ML, Golberg A, Serša G, Kotnik T, Miklavčič D. Electroporation-based technologies for medicine: principles, applications, and challenges. Annu Rev Biomed Eng. 2014;16(1):295-320. 10.1146/annurev-bioeng-071813-104622 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Rakoczy K, Kisielewska M, Sędzik M, et al. Electroporation in Clinical Applications—The Potential of Gene Electrotransfer and Electrochemotherapy. 25 October 2022. Accessed July 15, 2024. https://www.mdpi.com/2076-3417/12/21/10821

- 14. Miklavčič D, Mali B, Kos B, Heller R, Serša G. Electrochemotherapy: from the drawing board into medical practice. Biomed Eng Online. 2014;13(1):29. 10.1186/1475-925X-13-29 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Mir LM. Bases and rationale of the electrochemotherapy. Eur J Cancer Suppl. 2006;4(11):38-44. 10.1016/j.ejcsup.2006.08.005 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Zakelj MN, Prevc A, Kranjc S, et al. Electrochemotherapy of radioresistant head and neck squamous cell carcinoma cells and tumor xenografts. Oncol Rep. 2019;41(3):1658-1668. 10.3892/or.2019.6960 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Prevc A, Niksic Zakelj M, Kranjc S, et al. Electrochemotherapy with cisplatin or bleomycin in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma: improved effectiveness of cisplatin in HPV-positive tumors. Bioelectrochemistry. 2018;123:248-254. 10.1016/j.bioelechem.2018.06.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Jarm T, Cemazar M, Miklavcic D, Sersa G. Antivascular effects of electrochemotherapy: implications in treatment of bleeding metastases. Expert Rev Anticancer Ther. 2010;10(5):729-746. 10.1586/era.10.43 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Jenkins EPW, Finch A, Gerigk M, Triantis IF, Watts C, Malliaras GG. Electrotherapies for glioblastoma. Adv Sci (Weinh). 2021;8(18):e2100978. 10.1002/advs.202100978 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Bendix MB, Houston A, Forde PF, Brint E. Electrochemotherapy and immune interactions; a boost to the system? Eur J Surg Oncol. 2022;48(9):1895-1900. 10.1016/j.ejso.2022.05.023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Serša G, Miklavčič D, Čemažar M, Belehradek J, Jarm T, Mir LM. Electrochemotherapy with CDDP on LPB sarcoma: comparison of the anti-tumor effectiveness in immunocompotent and immunodeficient mice. Bioelectrochem Bioenerg. 1997;43(2):279-283. 10.1016/S0302-4598(96)05194-X [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Falk H, Lambaa S, Johannesen HH, Wooler G, Venzo A, Gehl J. Electrochemotherapy and calcium electroporation inducing a systemic immune response with local and distant remission of tumors in a patient with malignant melanoma—a case report. Acta Oncol. 2017;56(8):1126-1131. 10.1080/0284186X.2017.1290274 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Nabrinsky E, Macklis J, Bitran J. A review of the abscopal effect in the era of immunotherapy. Cureus. 2022;14(9):e29620. 10.7759/cureus.29620 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Tugues S, Burkhard SH, Ohs I, et al. New insights into IL-12-mediated tumor suppression. Cell Death Differ. 2015;22(2):237-246. 10.1038/cdd.2014.134 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Gibot L, Montigny A, Baaziz H, Fourquaux I, Audebert M, Rols MP. Calcium delivery by electroporation induces in vitro cell death through mitochondrial dysfunction without DNA damages. Cancers (Basel). 2020;12(2):425. 10.3390/cancers12020425 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Falk H, Matthiessen LW, Wooler G, Gehl J. Calcium electroporation for treatment of cutaneous metastases; a randomized double-blinded phase II study, comparing the effect of calcium electroporation with electrochemotherapy. Acta Oncol. 2018;57(3):311-319. 10.1080/0284186X.2017.1355109 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Mir LM, Gehl J, Sersa G, et al. Standard operating procedures of the electrochemotherapy: instructions for the use of bleomycin or cisplatin administered either systemically or locally and electric pulses delivered by the CliniporatorTM by means of invasive or non-invasive electrodes. Eur J Cancer Suppl. 2006;4(11):14-25. 10.1016/j.ejcsup.2006.08.003 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Ottlakan A, Lazar G, Olah J, et al. Current updates in bleomycin-based electrochemotherapy for deep-seated soft-tissue tumors. Electrochem. 2023;4(2):282-290. 10.3390/electrochem4020019 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Pavliha D, Kos B, Marčan M, Zupanič A, Serša G, Miklavčič D. Planning of electroporation-based treatments using web-based treatment-planning software. J Membr Biol. 2013;246(11):833-842. 10.1007/s00232-013-9567-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Simioni A, Valpione S, Granziera E, et al. Ablation of soft tissue tumours by long needle variable electrode-geometry electrochemotherapy: final report from a single-arm, single-centre phase-2 study. Sci Rep. 2020;10(1):2291. 10.1038/s41598-020-59230-w [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Miklavcic D, Davalos RV. Electrochemotherapy (ECT) and irreversible electroporation (IRE) -advanced techniques for treating deep-seated tumors based on electroporation. Biomed Eng Online. 2015;14 Suppl 3(Suppl 3):I1. 10.1186/1475-925X-14-S3-I1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Mali B, Jarm T, Corovic S, et al. The effect of electroporation pulses on functioning of the heart. Med Biol Eng Comput. 2008;46(8):745-757. 10.1007/s11517-008-0346-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Balevičiūtė A, Radzevičiūtė E, Želvys A, et al. High-frequency nanosecond bleomycin electrochemotherapy and its effects on changes in the immune system and survival. Cancers (Basel). 2022;14(24):6254. 10.3390/cancers14246254 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Mali B, Jarm T, Snoj M, Sersa G, Miklavcic D. Antitumor effectiveness of electrochemotherapy: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2013;39(1):4-16. 10.1016/j.ejso.2012.08.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Neumann E, Rosenheck K. Permeability changes induced by electric impulses in vesicular membranes. J Membr Biol. 1972;10(3):279-290. 10.1007/BF01867861 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Gehl J, Sersa G, Garbay J, et al. Results of the ESOPE (European Standard Operating Procedures on Electrochemotherapy) study: efficient, highly tolerable and simple palliative treatment of cutaneous and subcutaneous metastases from cancers of any histology. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24(18_suppl):8047-8047. 10.1200/jco.2006.24.18_suppl.8047 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Bertino G, Sersa G, Terlizzi FD, et al. European Research on Electrochemotherapy in Head and Neck Cancer (EURECA) project: results of the treatment of skin cancer. Eur J Cancer. 2016;63(1):41-52. 10.1016/j.ejca.2016.05.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Clover AJP, de Terlizzi F, Bertino G, et al. Electrochemotherapy in the treatment of cutaneous malignancy: Outcomes and subgroup analysis from the cumulative results from the pan-European International Network for Sharing Practice in Electrochemotherapy database for 2482 lesions in 987 patients (2008–2019). Eur J Cancer. 2020;138(1):30-40. 10.1016/j.ejca.2020.06.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Campana LG, Quaglino P, de Terlizzi F, et al. ; InspECT Melanoma and QoL Working Groups. Health-related quality of life trajectories in melanoma patients after electrochemotherapy: real-world insights from the InspECT register. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2022;36(12):2352-2363. 10.1111/jdv.18456 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. McMillan AT, McElroy L, O'Toole L, Matteucci P, Totty JP. Electrochemotherapy vs radiotherapy in the treatment of primary cutaneous malignancies or cutaneous metastases from primary solid organ malignancies: a systematic review and narrative synthesis. PLoS One. 2023;18(7):e0288251. 10.1371/journal.pone.0288251 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Edhemovic I, Gadzijev EM, Brecelj E, et al. Electrochemotherapy. Technol Cancer Res Treat. 2011;10(5):475-485. 10.7785/tcrt.2012.500224 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Kovács A, Iezzi R, Cellini F, et al. Critical review of multidisciplinary non-surgical local interventional ablation techniques in primary or secondary liver malignancies. J Contemp Brachytherapy. 2019;11(6):589-600. 10.5114/jcb.2019.90466 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Kovács A, Bischoff P, Haddad H, et al. Long-term comparative study on the local tumour control of different ablation technologies in primary and secondary liver malignancies. J Pers Med. 2022;12(3):430. 10.3390/jpm12030430 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Orcutt ST, Anaya DA. Liver resection and surgical strategies for management of primary liver cancer. Cancer Control. 2018;25(1):1073274817744621. 10.1177/1073274817744621 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Zmuc J, Gasljevic G, Sersa G, et al. Large liver blood vessels and bile ducts are not damaged by electrochemotherapy with bleomycin in pigs. Sci Rep. 2019;9(1):3649. 10.1038/s41598-019-40395-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Granata V, Fusco R, Piccirillo M, et al. Electrochemotherapy in locally advanced pancreatic cancer: Preliminary results. Int J Surg. 2015;18:230-236. 10.1016/j.ijsu.2015.04.055 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Granata V, Grassi R, Fusco R, et al. Local ablation of pancreatic tumors: state of the art and future perspectives. World J Gastroenterol. 2021;27(23):3413-3428. 10.3748/wjg.v27.i23.3413 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Casadei R, Ricci C, Ingaldi C, et al. Intraoperative electrochemotherapy in locally advanced pancreatic cancer: indications, techniques and results—a single-center experience. Updates Surg. 2020;72(4):1089-1096. 10.1007/s13304-020-00782-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Granata V, Fusco R, Setola SV, et al. Diffusion kurtosis imaging and conventional diffusion weighted imaging to assess electrochemotherapy response in locally advanced pancreatic cancer. Radiol Oncol. 2019;53(1):15-24. 10.2478/raon-2019-0004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Rudno-Rudzińska J, Kielan W, Guziński M, Płochocki M, Antończyk A, Kulbacka J. New therapeutic strategy: personalization of pancreatic cancer treatment-irreversible electroporation (IRE), electrochemotherapy (ECT) and calcium electroporation (CaEP)—a pilot preclinical study. Surg Oncol. 2021;38:101634. 10.1016/j.suronc.2021.101634 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Izzo F, Granata V, Fusco R, et al. Clinical Phase I/II Study: Local Disease Control and Survival in Locally Advanced Pancreatic Cancer Treated with Electrochemotherapy. March 22, 2021. Accessed July 15, 2024. https://www.mdpi.com/2077-0383/10/6/1305 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 52. Andresciani F, Faiella E, Altomare C, Pacella G, Beomonte Zobel B, Grasso RF. Reversible electrochemotherapy (ECT) as a treatment option for local RCC recurrence in solitary kidney. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol. 2020;43(7):1091-1094. 10.1007/s00270-020-02498-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Mastrandrea G, Laface C, Fazio V, et al. A case report of cryoablation and electrochemotherapy in kidney cancer. Medicine (Baltimore). 2021;100(45):e27730. 10.1097/MD.0000000000027730 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Campanacci L, Cevolani L, De Terlizzi F, et al. Electrochemotherapy is effective in the treatment of bone metastases. Curr Oncol. 2022;29(3):1672-1682. 10.3390/curroncol29030139 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Cevolani L, Campanacci L, Staals EL, et al. Is the association of electrochemotherapy and bone fixation rational in patients with bone metastasis? J Surg Oncol. 2023;128(1):125-133. 10.1002/jso.27247 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Egeland C, Baeksgaard L, Johannesen HH, et al. Endoscopic electrochemotherapy for esophageal cancer: a phase I clinical study. Endosc Int Open. 2018;6(6):E727-E734. 10.1055/a-0590-4053 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Falk Hansen H, Bourke M, Stigaard T, et al. Electrochemotherapy for colorectal cancer using endoscopic electroporation: a phase 1 clinical study. Endosc Int Open. 2020;8(2):E124-E132. 10.1055/a-1027-6735 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Schipilliti FM, Onorato M, Arrivi G, et al. Electrochemotherapy for solid tumors: literature review and presentation of a novel endoscopic approach. Radiol Oncol. 2022;56(3):285-291. 10.2478/raon-2022-0022 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Ágoston D, Baltás E, Ócsai H, et al. Evaluation of calcium electroporation for the treatment of cutaneous metastases: a double blinded randomised controlled phase II trial. Cancers (Basel). 2020;12(1):179. 10.3390/cancers12010179 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Egeland C, Baeksgaard L, Gehl J, Gögenur I, Achiam MP. Palliative treatment of esophageal cancer using calcium electroporation. Cancers (Basel). 2022;14(21):5283. 10.3390/cancers14215283 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Broholm M, Vogelsang R, Bulut M, et al. Endoscopic calcium electroporation for colorectal cancer: a phase I study. Endosc Int Open. 2023;11(5):E451-E459. 10.1055/a-2033-9831 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Plaschke CC, Gehl J, Johannesen HH, et al. Calcium electroporation for recurrent head and neck cancer: a clinical phase I study. Laryngoscope Investig Otolaryngol. 2019;4(1):49-56. 10.1002/lio2.233 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Ahmed-Salim Y, Saso S, Meehan HE, et al. A novel application of calcium electroporation to cutaneous manifestations of gynaecological cancer. Eur. J. Gynaecol. Oncol. 2021;42(4):662-672. 10.31083/j.ejgo4204102 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Daud AI, DeConti RC, Andrews S, et al. Phase I trial of interleukin-12 plasmid electroporation in patients with metastatic melanoma. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26(36):5896-5903. 10.1200/JCO.2007.15.6794 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Algazi A, Bhatia S, Agarwala S, et al. Intratumoral delivery of tavokinogene telseplasmid yields systemic immune responses in metastatic melanoma patients. Ann Oncol. 2020;31(4):532-540. 10.1016/j.annonc.2019.12.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Bhatia S, Longino NV, Miller NJ, et al. Intratumoral delivery of plasmid IL12 via electroporation leads to regression of injected and noninjected tumors in merkel cell carcinoma. Clin Cancer Res. 2020;26(3):598-607. 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-19-0972 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Telli ML, Nagata H, Wapnir I, et al. Intratumoral plasmid IL12 expands CD8+ T cells and induces a CXCR3 gene signature in triple-negative breast tumors that sensitizes patients to anti-PD-1 therapy. Clin Cancer Res. 2021;27(9):2481-2493. 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-20-3944 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Algazi AP, Twitty CG, Tsai KK, et al. Phase II trial of IL-12 plasmid transfection and PD-1 blockade in immunologically quiescent melanoma. Clin Cancer Res. 2020;26(12):2827-2837. 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-19-2217 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Sersa G, Ursic K, Cemazar M, Heller R, Bosnjak M, Campana LG. Biological factors of the tumour response to electrochemotherapy: review of the evidence and a research roadmap. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2021;47(8):1836-1846. 10.1016/j.ejso.2021.03.229 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Lisec B, Markelc B, Ursic Valentinuzzi K, Sersa G, Cemazar M. The effectiveness of calcium electroporation combined with gene electrotransfer of a plasmid encoding IL-12 is tumor type-dependent. Front Immunol. 2023;14:1189960. 10.3389/fimmu.2023.1189960 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Kiełbik A, Szlasa W, Saczko J, Kulbacka J. Electroporation-based treatments in urology. Cancers (Basel). 2020;12(8):2208. 10.3390/cancers12082208 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Electrochemotherapy for Metastases in the Skin from Tumours of Non-Skin Origin and Melanoma. March 27, 2013. Accessed July 15, 2024. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ipg446/chapter/1-Guidance

- 73. Benedik J, Ogorevc B, Brezar SK, Cemazar M, Sersa G, Groselj A. Comparison of general anesthesia and continuous intravenous sedation for electrochemotherapy of head and neck skin lesions. Front Oncol. 2022;12:1011721. 10.3389/fonc.2022.1011721 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Perera-Bel E, Aycock KN, Salameh ZS, et al. PIRET—a platform for treatment planning in electroporation-based therapies. IEEE Trans Biomed Eng. 2023;70(6):1902-1910. 10.1109/TBME.2022.3232038 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Lorenzo MF, Bhonsle SP, Arena CB, Davalos RV. Rapid impedance spectroscopy for monitoring tissue impedance, temperature, and treatment outcome during electroporation-based therapies. IEEE Trans Biomed Eng. 2021;68(5):1536-1546. 10.1109/TBME.2020.3036535 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. RESPECT. CIRSE. Accessed July 15, 2024. https://www.cirse.org/research/research-projects/respect/