Abstract

Within the established framework of structure formation, galaxies start as systems of low stellar mass and gradually grow into far more massive galaxies. The existence of massive galaxies in the first billion years of the Universe, as suggested by recent observations, seems to challenge this model, as such galaxies would require highly efficient conversion of baryons into stars. An even greater challenge in this epoch is the existence of massive galaxies that have already ceased forming stars. However, robust detections of early massive quiescent galaxies have been challenging due to the coarse wavelength sampling of photometric surveys. Here we report the spectroscopic confirmation with the James Webb Space Telescope of the quiescent galaxy RUBIES-EGS-QG-1 at redshift z = 4.90, 1.2 billion years after the Big Bang. Deep stellar absorption features in the spectrum reveal that the stellar mass of the galaxy of 1011 M⊙ formed in a short 200 Myr burst of star formation, after which star formation activity dropped rapidly and persistently. According to current galaxy formation models, systems with such rapid stellar mass growth and early quenching are too rare to plausibly occur in the small area probed spectroscopically with JWST. Instead, the discovery of RUBIES-EGS-QG-1 implies that early massive quiescent galaxies can be quenched earlier or exhaust gas available for star formation more efficiently than assumed at present.

Subject terms: Galaxies and clusters, Early universe

RUBIES-EGS-QG-1 is an exceptionally massive and mature galaxy discovered just 1.2 billion years after the Big Bang. Its stars formed in an extremely rapid burst, posing a major challenge to all current theoretical models.

Main

Recent observations with the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) have unveiled a surprising number of massive galaxies in the early Universe, reaching stellar masses of up to 1011 M⊙ only 800 Myr after the Big Bang1. The rapid growth of these massive systems implies a very high conversion efficiency of baryons into stars, which poses a challenge to theoretical models of galaxy formation and possibly even strains the standard cosmological model2–4. Even more puzzling is that many of these massive galaxies seem to be quiescent5–7, whereas most galaxies in this early epoch have high star formation activity8. However, to date, few high-redshift (z > 4) massive quiescent galaxies have been confirmed spectroscopically, leaving open major questions regarding their nature and their formation.

RUBIES-EGS-QG-1 was identified in the extended Groth strip (EGS) as a candidate massive quiescent galaxy at z > 4.5 based on its red colour, as measured from photometry across 1–5 μm obtained with the near-infrared camera (NIRCam) onboard JWST9–11. The source was subsequently selected as a target for a spectroscopic follow-up with the near-infrared spectrograph (NIRSpec) also onboard JWST because of its red colour, F150W − F444W = 2.35, and bright apparent magnitude at long wavelengths, F444W = 22.5. The low-resolution PRISM spectrum of RUBIES-EGS-QG-1 obtained with JWST/NIRSpec (Fig. 1) reveals deep Balmer absorption lines and a strong spectral break at a rest-frame wavelength of 4,000 Å, indicating a lack of star formation in its recent history.

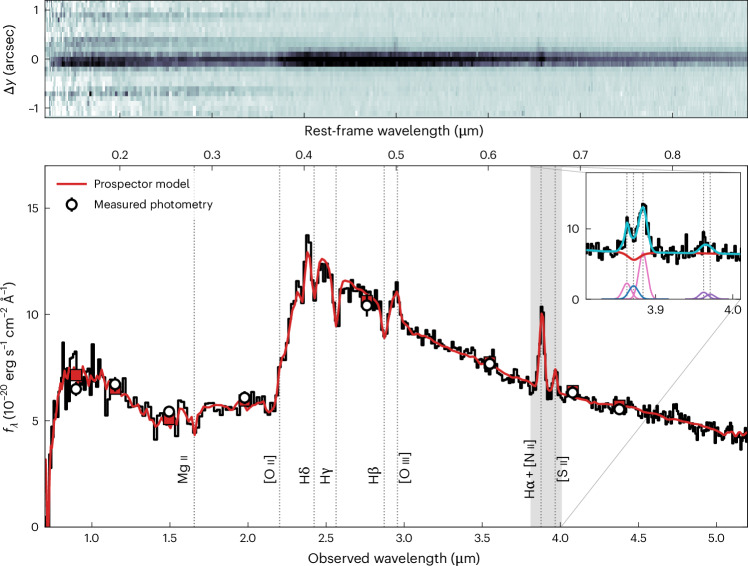

Fig. 1. JWST/NIRSpec PRISM spectrum of the massive quiescent galaxy RUBIES-EGS-QG-1 at a redshift of z = 4.8976.

The 1D spectrum (flux density fλ; bottom panel) shows deep Balmer absorption lines, like those of post-starburst galaxies at lower redshifts, which implies a lack of star formation in its recent history. Inset, medium-resolution (NIRSpec G395M) spectrum around the wavelength of Hα. Both spectra were calibrated to the measured photometry (error bars on the photometric data points reflect 1σ measurement uncertainties) using Prospector. The presence of the emission-line doublets [O iii], [N ii] and [S ii] and the minimal inferred infilling of the Hα absorption line are consistent with AGN activity. The 2D spectrum (top panel) shows the spatial distribution of the emission in the cross-dispersion direction (Δy). In addition to the compact massive quiescent galaxy, we identify the [O III] and Hα emission of a faint companion source that is offset by approximately +0.2 arcsec and -600 km s−1 (rest-frame velocity).

We detected the [O iii]λλ4960,5008, [S ii]λλ6718,6733 and blended Hα and [N ii]λλ6549,6585 emission lines in the PRISM spectrum. A grating spectrum of RUBIES-EGS-QG-1 with higher spectral resolution across 2.9–5.2 μm revealed weak Hα emission infilling the stellar absorption feature and strong [N ii] emission at a redshift of (Methods). A marginal detection of Hα implies log([N ii]λ6585/Hα) ≈ 0.5 and exceeds the ratio that can be explained by photoionization from massive stars by a factor of 3 (ref. 12). Therefore, the emission lines do not seem to be connected to continuing star formation activity but rather suggest the presence of an active galactic nucleus (AGN), although we cannot rule out the presence of shocked gas13. Despite evidence for an AGN, the deep Balmer lines, indicative of a post-starburst system14, suggest that the continuum emission of the spectrum is dominated by an evolved stellar population.

The high redshift of RUBIES-EGS-QG-1 allows for stringent constraints on its star formation history in the first billion years of the Universe. To measure the star formation history, we used Prospector15 to jointly fit a 21-parameter model to the PRISM spectrum and the observed photometry from the Hubble Space Telescope and JWST (see Methods for a complete description). In brief, the model star formation history was parameterized as 14 time bins of constant star formation, with a common metallicity, dust attenuation, intrinsic velocity dispersion and stellar initial mass function. We fitted nebular emission lines using a simple model in which lines are approximated by Gaussian profiles, but no assumption was made about the origin of the emission. We used a sixth-order polynomial to account for uncertainty in the flux calibration of the spectrum. We explore the effect of deviations in choices from our fiducial model in Methods.

The median model of the sampled posterior is shown in red in Fig. 1. We found a high stellar mass of and a low star formation rate in the past 100 Myr, M⊙ yr−1. Together, these correspond to a low specific star formation rate of , cementing RUBIES-EGS-QG-1 as the highest-redshift spectroscopic confirmation of a massive quiescent galaxy to date. We inferred low attenuation by dust, with the V-band attenuation from our modelling . The spectrum unambiguously demonstrates the red rest-frame optical colour is dominated by old stars rather than dust-obscured star formation. This was corroborated by a non-detection in observations by the Northern Extended Millimeter Array (NOEMA) at 1.1 mm, which implies a 3σ upper limit on the dust-obscured star formation rate of 120 M⊙ yr−1.

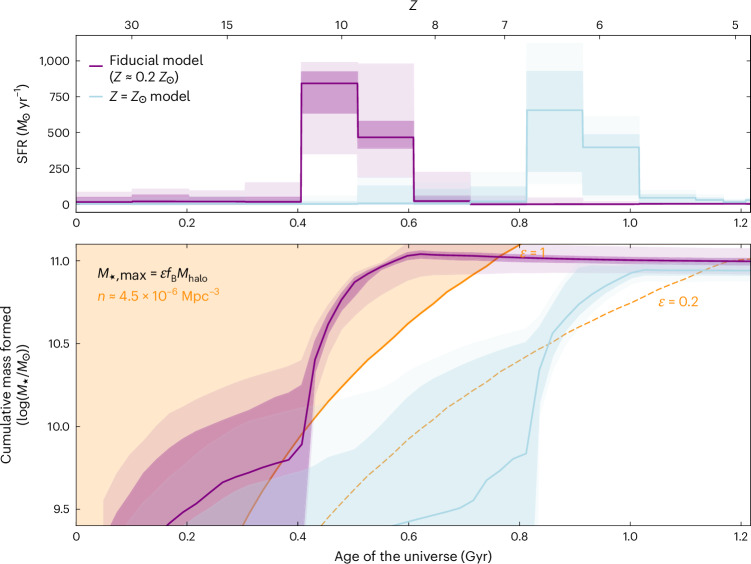

We show the resulting star formation history of the galaxy in the top panel of Fig. 2 in purple. RUBIES-EGS-QG-1 assembled its stellar mass within a short burst of star formation, Myr, which peaked at a star formation rate . For our fiducial model, half of the stellar mass was formed in the first Myr of cosmic time, which would mark it as one of the earliest-forming massive galaxies observed. We measured a corresponding quenching timescale Myr (where t90 is the time at which 90% of stellar mass formed), indicating that the decline in star formation from its peak in RUBIES-EGS-QG-1 was extremely rapid.

Fig. 2. History of stellar mass growth in RUBIES-EGS-QG-1.

Top, Star formation history inferred from the modelling to the PRISM spectrum and photometry for the fiducial (free-metallicity) model (purple) and the fixed-solar-metallicity model (blue). Dark (light) shaded regions indicate the 1σ (2σ) confidence intervals of the posterior distributions. Bottom, Cumulative mass history inferred from the star formation history of the two models. Marked in orange is the maximum stellar mass (M*,max) formed for the halo mass (Mhalo) of a typical halo at the observed number density of massive quiescent galaxies at z > 4 (ref. 9), assuming a universal baryon-to-total matter ratio (fB) and different baryon-to-stellar conversion factors (ε). This indicates that a short burst (~300 Myr) of star formation with high efficiency of ε > 0.2 is required to form RUBIES-EGS-QG-1, corresponding to an efficiency at or greater than the peak of the stellar–halo mass relation29.

Crucially, we found that the inferred stellar mass, the duration of the star formation burst and the lack of recent star formation activity were largely robust against choices made in the model parameterization and star formation history priors. A full description of models tested can be found in Methods. However, we found that the age of the stellar population depended strongly on the assumed metallicity of the system. Our fiducial fit with the metallicity as a free parameter indicates a low stellar metallicity (~0.2 Z⊙) and an old stellar population that formed as early as and stopped growing by z ≈ 8.6. Recent work has shown that the elemental abundance patterns in high-redshift quiescent galaxies differ from the solar abundance patterns typically used in stellar population modelling, which can lead to incorrectly inferred stellar metallicities16. When we instead fixed the metallicity of the stellar population to the solar value, we inferred a substantially younger population with a formation redshift of as well as more recent quenching (shown as the blue curve in Fig. 2). Although we could not robustly differentiate between these two star formation histories with our current data, we stress that the stellar mass, the timescale and peak of the burst of star formation, and the quenching timescale do not depend significantly on metallicity.

We estimated the dynamical mass of the system using the observed widths of the emission lines and the half-light radius measured from the F444W image, re = 0.55 ± 0.01 kpc (rest-frame wavelength of 0.75 μm; Methods). We found that is consistent with RUBIES-EGS-QG-1 being a very massive galaxy. The dynamical mass is a factor 3 higher than the stellar mass estimate, although note that the estimated dynamical mass may be elevated by a factor of 2–3 due to non-gravitational motions of the ionized gas that we have not accounted for. The centres of high-redshift massive galaxies are expected to be dominated by stellar mass within the effective radius17, which suggests that the stellar mass was not substantially under- or overestimated, despite uncertainties in the initial mass function assumed in our modelling.

The stellar mass surface density within the estimated half-light radius of is high but well within theoretical limits for the maximum surface density achievable in a short burst of star formation18,19. It is also in line with previous work at z < 3, which demonstrated a strong link between low specific star formation rates and high central mass densities, with a threshold density for quiescence that increases toward higher redshift20,21. This connection between galaxy structure and the star formation history has been interpreted as a compaction event followed by quenching due to feedback from intense star formation and an AGN22, and it is consistent with the high [N ii]/Hα ratio observed in RUBIES-EGS-QG-1, which is indicative of an AGN or shocked gas.

With a peak star formation rate of ~870 M⊙ yr−1 at z > 6, RUBIES-EGS-QG-1 had a higher star formation activity than a large sample of the 40 most ultraviolet-luminous sources at z ≈ 7 discovered over an area of 7 degrees squared (ref. 23). Interestingly, the star formation rate and its star formation rate surface density (ΣSFR ≈ 450 M⊙ yr−1 kpc−2) are like those of the dusty star-forming galaxy G09 83808 at z ≈ 6, which resembles a local ultra-luminous infrared galaxy24, and the submillimetre galaxy SPT0311-58 at z = 6.9 (ref. 25). The star formation history of RUBIES-EGS-QG-1 also matches well with the inferred star formation histories of the brightest red sources found with JWST26 at z ≈ 7, provided that the light emitted by these sources originates from stars. These different observations suggest that the burst of star formation that formed RUBIES-EGS-QG-1 could too have been strongly obscured by dust. Such a link has also been suggested for the other spectroscopically confirmed massive quiescent galaxy at z > 4.5 (ref. 7), observed at z = 4.658 with a stellar mass of ~3.8 × 1010 M⊙ that formed at zform = 6.9 ± 0.2. In comparison with this source, however, RUBIES-EGS-QG-1 stands out for being more than twice as massive. On the other hand, a dust-obscured period of star formation may be difficult to reconcile with the inferred low metallicity and that to date no submillimetre galaxy has been found at z > 8 with a star formation rate >200 M⊙ yr−1 (refs. 23,27). Therefore, this could, instead, imply that RUBIES-EGS-QG-1 is an exceptionally rare source or that its star formation history is either considerably more extended or more bursty than inferred from our modelling. In the latter scenario, finding ultraviolet-luminous progenitors at z ≈ 10 may be difficult, as the probability of discovery depends on both the low number density of extremely massive high-redshift galaxies and on the duty cycle of star formation.

The mere existence of RUBIES-EGS-QG-1 provides an essential constraint on the growth of the most massive galaxies in the early Universe. The bottom panel of Fig. 2 shows the cumulative mass assembly history of the galaxy derived from the modelled star formation history, after subtracting mass returned to the interstellar medium through stellar evolution, as a function of the age of the Universe. The small area targeted with JWST spectroscopy in the RUBIES survey (~100 arcmin2 thus far) implies an observed number density of n ≈ 3 × 10−6 Mpc−3 at 4.5 < z < 5.5. Based on the photometric selection of candidate massive quiescent galaxies in JWST imaging9, the comoving number density of quiescent galaxies of similar mass to RUBIES-EGS-QG-1 (M* > 1011 M⊙) is approximately equally low, n ≈ 4.5 × 10−6 Mpc−3 at 4 < z < 5. Hence, we used this number density to estimate the typical dark matter halo mass (Mhalo) at a fixed redshift and derive an approximate limit on the total baryonic mass available within the halo3. This was then converted to a maximum stellar mass at a given redshift by assuming M*(z) = εfBMhalo(z), where fB is the cosmic baryon fraction (15.6%)28 and ε is the baryon-to-star conversion efficiency. We plotted this expected stellar mass for two values of the baryon efficiency: ε = 1 (assuming the total conversion of baryons to stars) and the efficiency at the peak of the stellar–halo mass relation of ε = 0.2 (ref. 29). The cumulative mass assembly history of RUBIES-EGS-QG-1 implies a high efficiency of star formation of ε > 0.2. The low-metallicity model even suggests that the galaxy was converting baryons to stars with near-perfect efficiency.

Neither the extremely rapid mass assembly nor the early quenching of RUBIES-EGS-QG-1 are consistent with predictions from large-volume (2003 to 8003 Mpc3) cosmological hydrodynamical (FLARES30, Magneticum Pathfinder31 and TNG30032) and semi-analytic (GAEA33 and SHARK34) simulations of galaxy formation. Although some of these models can produce galaxies that are quiescent at z ≈ 4.5–5.0 and are as massive as RUBIES-EGS-QG-1, such systems are extremely rare. The comoving number densities were approximately 1 to 10 × 10−8 Mpc−3 in the different simulations and correspond to very massive haloes. In comparison with the estimated number density of RUBIES-EGS-QG-1, this implies a probability of 1% (2σ outlier) that such a source is observed in the small area probed spectroscopically with JWST (~100 arcmin2 for the RUBIES programme). However, at higher redshifts, the comoving number density of quiescent galaxies with stellar masses M* > 1011 M⊙ decreases dramatically, with most simulations containing zero such galaxies at z ≥ 5. The inferred star formation history of RUBIES-EGS-QG-1, for which star formation is quenched at z ≳ 5.5, therefore, implies that it would be a significant outlier at earlier times.

This indicates that the star formation and feedback recipes in the simulations do not accurately capture the formation and quenching processes of early massive galaxies. Alternatively, to reconcile the formation history of RUBIES-EGS-QG-1 with simulations requires that our estimated observed number density is substantially overestimated and that the galaxy, instead, resides in a very rare and, therefore, massive halo (Mhalo ≳ 1013 M⊙ by z ≈ 5). The effects of cosmic variance may be large for the relatively small area targeted spectroscopically with JWST. Although unlikely, it is possible that the observation of RUBIES-EGS-QG-1 is an ≳3σ chance finding and that it, indeed, resides in a very massive halo.

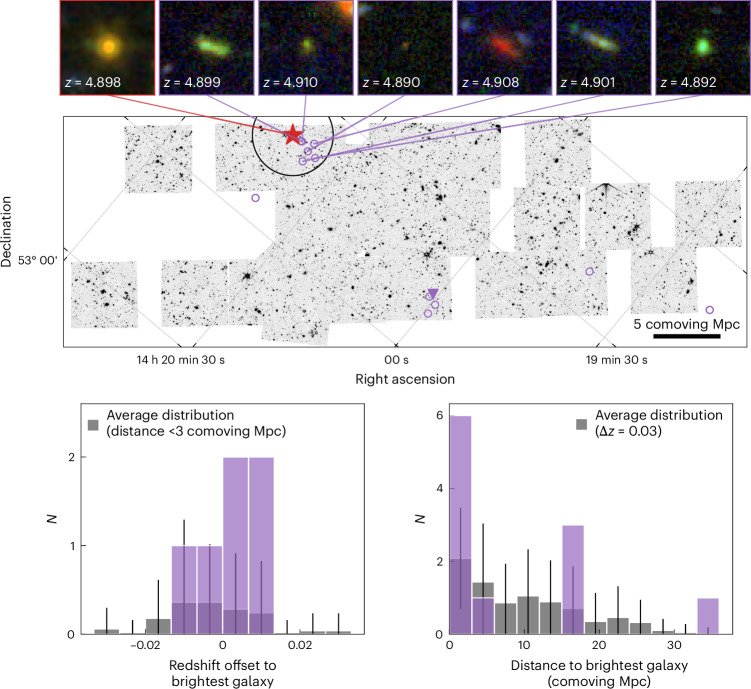

We examined the environment of RUBIES-EGS-QG-1 for evidence of such a large-scale overdensity by compiling all sources in the EGS with robust redshifts from JWST spectroscopy, obtained from a mixture of JWST cycle 1 and 2 programmes using the DAWN JWST Archive (DJA; Methods). We found six sources in the direct vicinity of RUBIES-EGS-QG-1 with a redshift separation Δz < 0.013 and projected separation of <1 arcmin (<2 comoving Mpc) and another seven sources spread across the field at the same redshift but with larger angular separation (Fig. 3). Notably, we found a clustering of four sources at a distance of ~16 comoving Mpc from RUBIES-EGS-QG-1, of which the brightest galaxy (measured at 4 μm) is a submillimetre galaxy identified previously in SCUBA-2 data35. In comparison with the average density of the 4 < z < 6 galaxy population, we found clear evidence for an overdensity at z = 4.90 within an aperture of π × 3 Mpc2 (as also suggested in the literature36,37), which forms the highest-redshift overdensity containing a massive quiescent galaxy found thus far38. However, based on these data alone, we cannot conclusively determine whether the region, indeed, represents an extremely massive halo or whether the other seven sources are associated with the overdensity.

Fig. 3. Spatial clustering of spectroscopically confirmed sources at z ≈ 4.90 around RUBIES-EGS-QG-1.

Middle, There are 13 sources (circles) at approximately the same redshift as the quiescent galaxy (red star), six of which are nearby neighbours. The submillimetre galaxy, the brightest source among the group of four at a projected distance of 16 comoving Mpc, is indicated by a purple triangle. The background image shows the NIRCam F444W mosaic of the EGS field. Bottom, Grey histograms show the mean projected spatial clustering (within redshift ranges Δz = 0.03) and redshift clustering (within apertures of radius <3 Mpc) for galaxies in the redshift range 4 < z < 6 with robust redshifts from JWST spectroscopy. Error bars show the standard deviation. RUBIES-EGS-QG-1 clearly resides in an overdense environment, forming the highest redshift known overdensity hosting a massive quiescent galaxy. Top, False-colour images (created from NIRCam F150W, F277W and F444W images) of RUBIES-EGS-QG-1 and its six nearby neighbours.

That the galaxy resides in an overdense environment may also point to substantial ex situ mass accretion, in addition to in situ star formation. A major merger between two approximately equally massive systems would provide a rapid accretion of stellar mass, allowing for more conventional star formation efficiencies. Moreover, major mergers have been proposed as a quenching mechanism39. However, equal-mass mergers between massive galaxies are exceptionally rare at z > 5, as the simulations predicted a number density of ≲10−8 Mpc−3 for such systems. We also did not find signatures of recent merging in the morphology of RUBIES-EGS-QG-1 (Fig. 3 and Methods).

Clearly, the rapid assembly of RUBIES-EGS-QG-1 and its early quenching requires an extreme formation scenario. In the context of recent studies that have reported candidate massive galaxies at z > 6 (ref. 1) and massive quiescent galaxies with formation times at z ≳ 6 (refs. 10,40–42), RUBIES-EGS-QG-1 stands out for its very high stellar mass, high redshift and deep Balmer absorption features, which unambiguously set its formation at z > 6. Theoretical models can form extremely massive galaxies at early epochs, and some also produce quiescent galaxies at z > 5. However, the number densities of these sources are extremely low. This may indicate that RUBIES-EGS-QG-1 lies in an extremely rare, massive halo for its redshift or the exceptional detection of a major merger between two massive galaxies. However, both of these scenarios are expected to be very rare (≲0.1 per degree squared), and the area covered by JWST spectroscopy thus far is small. The direct implication of the existence of RUBIES-EGS-QG-1 is, therefore, that the star formation and feedback prescriptions in theoretical models require revision, as the model universes cannot at present reproduce the stellar mass growth and early quenching required to match the inferred abundance of massive quiescent galaxies.

Methods

Spectroscopic data

The RUBIES programme (GO-4233; principal investigators (PIs) A. de Graaff and G. Brammer) is a JWST cycle 2 programme using the NIRSpec microshutter array (MSA)43 to observe galaxies in the CANDELS EGS and Ultra Deep Survey (UDS) extragalactic deep fields44,45. Specifically, RUBIES targets galaxies detected in F444W from JWST/NIRCam imaging in the Cosmic Evolution Early Release Science (CEERS; Programme 1345; PI S. Finkelstein) and Public Release Imaging for Extragalactic Research (Programme 1837; PI J. Dunlop) surveys, and it is optimized to reach high spectroscopic completeness for bright and red sources at z > 3. Thus far, the survey has targeted an area of approximately . Details of target selection and prioritization are given in ref. 46.

RUBIES-EGS-QG-1 (right ascension 214.9155459°, declination 52.9490183°) was observed in March 2024 as part of the observations in the EGS field. The MSA pointings were observed for 48 min each in the PRISM/CLEAR and the G395M/F290LP spectroscopic modes. Each target was observed in a 1 × 3 configuration of open microshutters with a three-point nodding pattern. The spectra were allowed to overlap on the detector in the G395M exposures as most sources have faint enough continua so as not to severely contaminate other spectra.

The NIRSpec data were reduced using the msaexp47 pipeline version 3, as described in ref. 46. Briefly, in comparison to version 2 of the pipeline described in ref. 48, we used updated reference files to improve flux calibration. In addition, we leveraged empty sky shutters from the RUBIES programme to derive custom bar shadow corrections, which provided a substantial improvement over the default reference files by removing strong (~10% level) unphysical discontinuities in the extracted spectrum. We also used the empty sky shutters to construct a global background subtraction for the PRISM spectra. We used local background subtraction from the nodded exposures for the G395M spectrum, as the overlapping traces on the detector in this mode made it difficult to construct a global background solution. A Gaussian profile was fitted to the two-dimensional PRISM spectra to estimate the intrinsic width and centroid of the trace. The one-dimensional spectra for both dispersers were then extracted using this Gaussian profile with an optimal weighting49. We scaled up the 1σ errors on the one-dimensional extracted spectrum by a factor of 1.7 to account for underestimated uncertainties when comparing the pixel-to-pixel variations with the msaexp-derived errors, as described in ref. 50. The final flux calibration of the RUBIES-EGS-QG-1 spectrum was performed by matching the continuum level in PRISM to the multi-band photometry from Hubble Space Telescope and JWST/NIRCam, as described in ‘Photometric data’.

Photometric data

We used publicly available JWST/NIRCam imaging from the CEERS programme51 as well as programme GO-2234 (PI Bañados; Khusanova et al. in preparation), which combined provided eight photometry bands (F090W, F115W, F150W, F200W, F277W, F356W, F444W and F410M).

We used the reduced image mosaics from the DJA (v.7.4). All images were reduced using grizli52 and have a pixel scale of 0.04 arcsec pix−1 (see ref. 9 for further details of the reduction). Next, we used empirical point spread function (PSF) models to construct mosaics that were PSF-matched to the F444W mosaic, as described in ref. 53. We measured fluxes in circular apertures with a radius of 0.25 arcsec from the PSF-matched photometry, which was centred on the centroid position estimated by running SourceExtractor54 on an inverse-variance weighted stack of the F277W, F356W and F444W bands.

We show image cut-outs of the F115W and F444W NIRCam filters in Supplementary Fig. 1 and include the positions of the NIRSpec microshutters. The centroid of RUBIES-EGS-QG-1 was at the bottom of a microshutter, with some of the light falling on the bar between two microshutters. Due to the large variation in the PSF width as a function of wavelength, the slit losses introduced by the bar shadow were highly complex, the effect of which we discuss further in ‘SED modelling’. We also found a faint blue clump in the F115W image, located ~0.2 arcsec from RUBIES-EGS-QG-1. In ‘Fitting the emission lines’, we show that emission lines from this source reveal that it is a satellite with a velocity separation of ~600 km s−1.

SED modelling

To measure the stellar population properties of RUBIES-EGS-QG-1, we used the Bayesian spectral energy distribution (SED) fitting code Prospector15,55,56 to fit non-parametric star formation histories to the NIRSpec/PRISM spectrum and the JWST/NIRCam photometry of this galaxy. We enforced a signal-to-noise ceiling of 20 on our photometric measurements to account for systematic uncertainties in the underlying stellar population models. We used flexible stellar population synthesis models57,58, the MILES spectral library59 and MIST isochrones60,61. We assumed a Chabrier initial mass function62 and fixed the model redshift to zprism = 4.906, the PRISM spectroscopic redshift estimated with msaexp, which differs slightly from the redshift derived from the G395M spectrum due to wavelength calibration uncertainties between the NIRSpec dispersers63. We masked the outer edges of the spectrum to avoid uncertainties in modelling absorption from the intergalactic medium (blueward of rest frame 1,200 Å) and the absolute flux calibration at the edge of the NIRSpec CLEAR filter where we did not have photometric coverage (>5.1 μm).

Our parameterization for the fiducial star formation history was a 14-bin non-parametric model using the Prospector continuity prior, with the logarithmic ratio between neighbouring bins fitted with a Student’s t-distribution prior centred at 0 with a width of 0.3 and ν = 2 following ref. 64. We divided the most recent 100 Myr of star formation into three bins of widths 5, 25 and 75 Myr, respectively, to provide fine sampling of the most recent star formation history, and we filled the remaining age of the Universe with 11 linearly spaced 100 Myr bins. We assumed a two-parameter dust law with free Av and dust index spanning [0, 2.5] and [−1, 0.4] respectively65, and we fixed the attenuation around young stars (t < 107 Myr) to be twice that of the older populations. We fitted for a free logarithmically sampled stellar metallicity in the range [0.1 Z⊙, 2 Z⊙]. We performed sampling using the dynesty nested sampling package66.

To account for the NIRSpec/PRISM resolution, we convolved all models using the PRISM resolution curve provided in the JWST User Documentation (https://jwst-docs.stsci.edu), scaled by a multiplicative factor of 1.3 as in ref. 67, which approximated the line spread function (LSF) of a compact source. As RUBIES-EGS-QG-1 is very massive, we expected there to be substantial intrinsic broadening of the stellar continuum due to the random motions of stars. As such, we fitted for another free continuum velocity dispersion, with a deliberately large prior (σsmooth = [0, 1,000] km s−1), which can also account for uncertainty in the precise normalization of the NIRSpec LSF. We also accounted for uncertainty in the NIRSpec flux calibration by fitting with the Prospector PolySpecModel prescription, which marginalized out a sixth-order multiplicative polynomial to rectify the observed spectrum to the model during each likelihood call. The choice to calibrate out such a high-order polynomial was motivated by the large wavelength baseline (~5 μm) of the PRISM spectrum coupled with the considerable uncertainty in the flux calibration on small scales due to the effect of differential slit losses. Because the source was partially on the bar between two shutters (Supplementary Fig. 1) and the PSF of JWST depends strongly on wavelength, the effect of the bar shadows also had a strong wavelength dependence. Our empirical bar shadow correction (‘Spectroscopic data’) derived from blank sky shutters provided only a first-order correction of this effect, as the sky emission filled the slit uniformly but the morphology of RUBIES-EGS-QG-1 followed a steep Sérsic profile (‘Size measurements’). This conservative approach used the spectrum only for sharp spectral features, such as emission or absorption lines and spectral breaks, and relied on the better-calibrated photometry to fix the shape of the SED. Note that using a lower-order polynomial (for example n = 1) yielded a similarly old, low-metallicity, stellar population (see also ‘Testing the star formation history’), although with a marginally lower stellar mass and more extended star formation history than our fiducial fit. However, this fit had a significantly higher χ2 value () and there were oscillatory features in the residuals, indicative of flux calibration issues.

Finally, we accounted for nebular emission in key emission lines (Lyα1216, [O ii]λλ3727,3729, [O iii]λλ4960,5008, Hδλ4103, Hγλ4342, Hβλ4864, Hαλ6564, [N ii]λλ6549,6585 and [S ii]λλ6718,6733) using the Prospector nebular marginalization procedure, which fitted for emission lines in the residual spectrum using a least squares algorithm and incorporated those models in each likelihood call. This procedure allowed the emission lines to be produced without ascribing the emission to a specific source, which was important given the strong evidence for non-star formation sources of ionizing radiation (‘Fitting the emission lines’), although our conclusions were unchanged when we allowed for physical nebular infilling of the Balmer absorption lines. As for the stellar continuum, we convolved all emission lines with a free emission-line velocity dispersion σgas = [0, 1,000] km s−1, where we assumed that all emission lines have the same width. Supplementary Fig. 2 shows the covariant posteriors for key parameters characterizing RUBIES-EGS-QG-1 and demonstrates that the fits were well converged.

Testing the star formation history

The central result of fitting the star formation history of RUBIES-EGS-QG-1 was the finding that the galaxy assembled its high stellar mass (~1011 M⊙) and ceased forming stars within only the first billion years of cosmic time, thus straining galaxy evolution models. Here, we explore how different choices for the parameterization of the star formation history or our priors could impact the inferred age of this system.

First, we examined the impact of choosing a different parameterization for the star formation history. Non-parametric models for the star formation history are commonly chosen because of their flexibility to account for a wide range of star formation history shapes, but such parameterizations systematically measure older ages with increased uncertainty68. As a soundness check, we performed our fiducial fit with a star formation history parameterized with the commonly used delayed τ (SFR ∝ te−t/τ) with just three free parameters describing the star formation history rather than 14. We found that this parametric star formation history almost identically recovers that of the non-parametric model, measuring Myr and recovering similar posteriors for the star formation rate, stellar mass, metallicity and t90 (Supplementary Fig. 3 and Supplementary Table 1), albeit with a slightly longer difference between the formation time of 10% and 90% of the total stellar mass, t90 − t10.

Second, we tested our non-parametric star formation history against the choice of prior to mitigate the concern that the inferred star formation history was prior-driven64,69. Instead of the flat prior assumed in our fiducial set-up, we imposed a rising star formation history prior, as expected from, for example, refs. 70,71, by shifting the mean logarithmic ratio of our Student’s t prior from 0.0 to 0.3 and rerunning our fiducial fit. We found that our measurement of tform was largely insensitive to the imposition of this prior and that the galaxy was still fitted as ~550 Myr old, despite a slight increase in the implied star formation rate and formation time.

We found that both the fiducial fit (insensitive to the prior for the star formation history) and delayed τ fits converged to subsolar metallicities, with all models suggesting that the metallicity of RUBIES-EGS-QG-1 is 15–20% solar. Our measurements of metallicity were indirect, in the sense that they were sensitive to the shape of the SED rather than specific spectral features due to the low resolution of the PRISM spectrum and the relative weakness of metal-sensitive features compared to the bright A-type stars that dominate the light of RUBIES-EGS-QG-1. However, these measurements are qualitatively consistent with the finding that massive quiescent galaxies at z > 1.4 are metal poor relative to solar abundances16,72 and with comparably high-redshift massive systems10. On the other hand, because of a lack of very young metal-poor stars in the Milky Way, empirical model libraries suffer from calibration issues for young ages and low metallicities, which together with uncertainties in the stellar isochrones can have a strong effect on the shape of the continuum of the resulting stellar population synthesis models73,74. We found that fits made using the C3K theoretical stellar libraries75 rather than the empirical MILES libraries resulted in low-metallicity solutions within ~0.1 dex of our fiducial runs and with comparable age measurements, highlighting that the preference of our fits to these low-metallicity solutions is insensitive to the choice of model libraries. Importantly, however, these model libraries all assume solar abundance patterns. Recent results indicate that deviations in the elemental abundance patterns from the solar abundances used in the stellar population synthesis models can also lead to incorrectly inferred metallicities16. Given that we measured very high [N ii]/Hα, which can locally be produced only in an AGN with high metallicity76, we also fitted the galaxy under the assumption of solar metallicity to quantify the effect that a model mismatch would have on the star formation history we inferred.

We found that fixing the metallicity to solar affected the goodness of fit, as evidenced by the slightly worse values of the fit (where Ndata is the number of data points in the spectrum, Supplementary Fig. 3). However, this difference was largely driven by differences in the subtle shape of the rest ultraviolet, where the NIRSpec PRISM resolution is worst and where stellar population libraries differ substantially. As such, it was difficult to reject this solution, even if the models formally favoured low-metallicity solutions. Choosing to fix the metallicity to solar had a negligible effect on the measured stellar mass, moving the median value by ~0.05 dex, but had a considerable impact on the inferred star formation history. At solar metallicity, the observed spectrum and photometry of RUBIES-EGS-QG-1 is best described by a stellar population that formed 50% of its mass ~400 Myr later than the low-metallicity fiducial model. The fit still implies that the galaxy assembled most of its mass within the first gigayear of cosmic time at the 2σ level, but the measured redshift where the galaxy had assembled 90% of its mass (and can be considered to have quenched) shifted from in the fiducial model to in the fixed-metallicity model. The fixed-metallicity fit also implies a very similar burst shape to the fiducial fit. Despite the later formation time, the estimated peak star formation rate, star formation duration and star formation decline timescale (bottom panels in Supplementary Fig. 3) match closely between all models. Finally, the fixed-metallicity star formation history still implies an extremely efficient star formation history, requiring ε > 0.2 for the estimated number density of the source (Fig. 2).

Future deep observations that can directly measure metal-sensitive features and that are less beholden to the low resolution of the NIRSpec/PRISM may enable us to place more robust constraints on the precise age, metallicity and dust content of this system. However, despite uncertainty in the exact age of the stellar population, the observed PRISM spectrum and photometry unambiguously demonstrate that RUBIES-EGS-QG-1 is a massive quiescent galaxy (M* ≈ 1011 M⊙) that assembled most of its mass within the first ~1 Gyr of cosmic time before rapidly quenching at z > 5.5, which strains current theoretical models (‘Theoretical predictions’).

Fitting the emission lines

The G395M spectrum obtained with JWST/NIRSpec (Supplementary Fig. 4) has a higher spectral resolution (R ≈ 1,000–1,500) and resolves the emission-line doublets and the Hα and [N ii] complex that are blended in the PRISM spectrum. We also found several emission lines that were spatially offset from the spectrum of RUBIES-EGS-QG-1. Crucially, we found that the lines at 2.95 and 3.85 μm were present in both the PRISM and G395M two-dimensional spectra. We identified these lines as [O iii] and Hα emission from the faint blue source in the F115W image (Supplementary Fig. 1). Additionally, one emission line in the spectrum at 3.80 μm was not seen in the PRISM spectrum. This implies that it originated from a different source on the NIRSpec MSA: the two-dimensional spectra for the two sources overlapped on the detector because the G395M spectra are longer than the PRISM traces.

We performed a simultaneous fitting to the continuum and the [O iii], [N ii] and [S ii] doublets. Although the extraction kernel used to obtain the one-dimensional spectrum mitigated contamination from the satellite and spurious sources, there was still some emission from these sources. We, therefore, masked the contaminant emission line at 3.80 μm but explicitly included the [O iii] and Hα lines of the satellite source in our model. We modelled each emission line with a Gaussian line profile. The line ratio of [N ii] was fixed to 1:2.94 and that of [O iii] to 1:2.98. Given the limited signal-to-noise ratio of the emission lines, we assumed that all emission (and absorption) lines have the same velocity dispersion, which was a free parameter in the fit. We also included a Hα emission-line component to estimate the infilling of the Balmer absorption line. As the Hα emission may have a different origin from the other emission lines, we left its velocity dispersion as another free parameter. To model the continuum, we used the deconvolved median posterior model from our Prospector fitting to the PRISM spectroscopy. We fitted a first-order polynomial between this continuum and the G395M spectrum to flux calibrate the spectrum. We assumed all components (except for the satellite source) were at the same redshift.

The model was convolved with a custom LSF tailored to the morphology of RUBIES-EGS-QG-1 based on the Sérsic fit at 4 μm (ref. 77). We allowed for uncertainty in the LSF following the method described in ref. 78. To estimate the posterior distributions of the parameters, we used the emcee package to perform Markov chain Monte Carlo sampling. We adopted uniform priors for all parameters, allowing for velocity dispersions in the range σgas ∈ [0, 750] km s−1. We set a broader prior for the Hα velocity dispersion, σHα ∈ [0, 1,500] km s−1, to test whether there was evidence for a broad-line AGN.

The emission-line fluxes are reported in Supplementary Table 2. We show the median posterior model of the combined continuum and emission-line fitting in Supplementary Fig. 4 as well as the individual emission-line and continuum components. From the fitting, we obtained a redshift of and ionized-gas velocity dispersion of . The velocity dispersion of the Hα line converged to a similar value, . The satellite source has a redshift of and is, thus, offset by approximately 600 km s−1 in the rest frame.

We found very weak Hα emission, marginally detected at the 2σ level. We, hence, measured the emission-line ratio log([N ii]λ6585/Hα) . Although the Hβ line falls outside the wavelength range covered by the G395M spectrum, we obtained a lower limit on the Hβ emission-line flux by assuming case B recombination (Hα/Hβ = 2.86). In this case, the lower limit on the ratio ([O iii]λ5008/Hβ) = . These line ratios indicate that the line emission in RUBIES-EGS-QG-1 did not originate from star formation12. Although shocked gas also results in high [N ii]/Hα line ratios, the ratio inferred from the spectrum and lower limit on the [O iii]/Hβ ratio are most probably consistent with ionization by an AGN13,79,80.

We used the ionized-gas velocity dispersion to estimate the dynamical mass using the methodology presented by ref. 81 so that we could relate the gas kinematics to the gravitational potential for compact quiescent galaxies. This assumed that the gas forms a rotating disk, with a rotational velocity that is related to the integrated gas velocity dispersion and the inclination (i) of the disk: , where α ≈ 0.8. Based on our morphological modelling (‘Size measurements’), we found that the projected axis ratio q ≈ 0.85. Assuming an intrinsic disk thickness of q0 = 0.2, this implies i = 32.5°. The dynamical mass was computed as , where re is the inferred half-light radius (‘Size measurements’) and G the gravitational constant. With re = 0.55 ± 0.01 kpc, we found , a factor ~3 higher than the measured stellar mass. Note that the gas kinematics may be a biased tracer of the gravitational potential, as the observed stellar and ionized-gas kinematics for a large sample of galaxies at z ≈ 1 have been shown to agree well on average82 but with a systematic offset of approximately 0.2 dex for σgas ≈ 400 km s−1. This may imply that the dynamical mass is overestimated by 0.4 dex (a factor of 2.5, Mdyn ≈ 1.1 × 1011 M⊙), which is consistent with the estimated stellar mass.

Size measurements

We measured the effective radius (re) of RUBIES-EGS-QG-1 as a function of wavelength using the GALFIT83,84 single-component Sérsic fitting methods from ref. 85 in all available filters (F115W, F150W, F200W, F277W, F356W, F410M and F444W), corresponding to rest-frame wavelengths in the range ~2,000 to 7,500 Å.

All filters were processed following the procedure described in ref. 86. The parameters were constrained in the model fits as follows. The magnitude could range ±3 mag from the photometric catalogue value, the radius could vary over 0.01 < re < 400 pixels, the Sérsic index could range from n = 0.2 to 10, and axis ratio could range from q = 0.0001 (flat) to q = 1 (round).

Next, sizes were corrected to account for residual flux using the methods of ref. 87. The growth curve from the best-fitting Sérsic model (deconvolved from the PSF) was added to the GALFIT residual growth curve. We extrapolated the combined growth curve using the Sérsic model alone when the annular signal-to-noise ratio <3 for the science image. The corrected radius was then defined as the radius where the residual plus unconvolved Sérsic growth curve reached 50%.

We found that RUBIES-EGS-QG-1 is remarkably compact, although we unambiguously resolved this galaxy in F356W, F410M and F444W. The F444W fit is shown in Supplementary Fig. 5, which suggests that it has a very compact profile (n = 8.80 ± 0.14) and a corrected half-light radius re = 0.55 ± 0.01 kpc (consistent with ref. 88). The F356W and F410M fits gave similar Sérsic indices (8.77 and 8.15, respectively) and corrected radii (0.50 and 0.58 kpc), indicating a flat colour gradient in the rest-frame optical (3,400 to 7,500 Å). Given the rapid assembly and quenching of RUBIES-EGS-QG-1, it was not surprising to find a flat colour gradient. See, for example, ref. 89. The shorter wavelength images (rest frame <3,000 Å) are very compact, and we had trouble converging them to accurate fits without hitting the n = 10 upper limit.

Environment at z = 4.9

Recent studies have speculated about the existence of an overdensity at z ≈ 5 in the EGS field, based on a clustering of photometric redshifts37 and a sample of four spectroscopic redshifts at z ≈ 4.90 obtained with JWST/NIRSpec36. With the addition of RUBIES-EGS-QG-1, this gives a sample of five spectroscopic redshifts.

To search for further evidence of a large-scale overdensity, we leveraged all available spectroscopic redshifts from JWST/NIRSpec in the EGS field. These spectra come from different JWST cycle 1 and 2 programmes: the CEERS programme, a director’s discretionary time programme (ID 2750; PI Arrabal Haro) and the RUBIES programme. All data from the DJA were reduced using the msaexp pipeline47, in the same manner as described in ‘Spectroscopic data’. Redshifts were obtained from the spectra using χ2 minimization template fitting with msaexp and visually inspected to evaluate the quality of the redshifts. The redshifts were predominantly derived from PRISM spectroscopy, although approximately half of the sources in CEERS were observed with the medium-resolution gratings only. We began by compiling all sources with robust redshifts (grade 3 from visual inspection) in the range 4 < z < 6 from the DJA, which resulted in 193 sources from RUBIES, 123 from CEERS and another 20 from the director’s discretionary time programme. Of these 336 sources, 289 were detected in NIRCam imaging, with the remainder falling outside the NIRCam footprint.

We selected galaxies within Δz = ±0.0135 (Δv = 4,000 km s−1) from the redshift of RUBIES-EGS-QG-1, chosen based on the typical redshift ranges used to search for overdensities (from the compilation in ref. 90), which is sufficiently large to account for systematic uncertainties in the wavelength calibration of NIRSpec63. We found 13 sources in this velocity range around RUBIES-EGS-QG-1 (Supplementary Fig. 6 and Supplementary Table 3), four of which were published previously. Of these 13 sources, six have a close angular separation to RUBIES-EGS-QG-1 of <1 arcmin, corresponding to <400 kpc or <2 comoving Mpc. We identified another clustering of four sources at a distance of ~7 arcmin (~16 comoving Mpc) from RUBIES-EGS-QG-1. Interestingly, the brightest source in the F444W imaging among these four (RUBIES-EGS-14295) is a submillimetre galaxy identified from SCUBA-2 850 μm data (S2CLS-EGS-850.061)35, which implies a high star formation rate. The remaining three sources were scattered across the field at varying distances.

The typical NIRSpec MSA can target approximately ~200 sources simultaneously, which generally leads to a complex selection function such that high-priority targets have a high probability of being allocated a shutter whereas an individual galaxy in the broader population has a low probability of being observed43,63,91. As a result, the spectroscopic completeness is probably low at intermediate redshift, as the science objective of moist programmes focuses on galaxies at z > 6. Because of this incompleteness, it was difficult to quantify the overdensity of the spectroscopic targets at the redshift of RUBIES-EGS-QG-1 to estimate its halo mass. However, we used the 4 < z < 6 galaxy population with robust spectroscopy to assess qualitatively whether RUBIES-EGS-QG-1 is probably part of an overdensity. Under the assumption that sources in this redshift range are targeted with approximately equal probability, we estimated the typical clustering of galaxies in redshift space at the projected distance.

To assess the expected clustering in redshift space, we selected the 50 brightest sources in F444W NIRCam imaging among the 336 spectroscopic targets. We then searched for sources within a radius of 3 comoving Mpc, approximately three times the virial radius of a moderately sized cluster at z = 0 (Mhalo ≈ 1014.5 M⊙), and we computed the redshift separation between each source and the brightest galaxy. The corresponding distribution in the redshift space peaked at Δz = 0 but was very broad (Fig. 3). Within the range Δz = 0.027, we found that the overdensity around RUBIES-EGS-QG-1 is significantly (3.1σ) above this background level. When we used a larger aperture, we found only marginal detections of 2.2σ (5 Mpc), 1.5σ (10 Mpc) and 1.6σ (20 Mpc).

Similarly, we selected all sources in narrow redshift windows of Δz = 0.027, stepping between z = 4.0 and 6.0, and we measured the angular separation with respect to the brightest source in the redshift slice. We again found a broad distribution in the projected distance, which we used to estimate the significance of the clustering of sources around RUBIES-EGS-QG-1. Within a radius of 3 Mpc, the neighbours of RUBIES-EGS-QG-1 were 2.8σ above the expected level. As before, this decreased when searching within larger apertures: 2.0σ within 5 Mpc, 1.0σ within 10 Mpc and 1.44σ within 20 Mpc.

We concluded that RUBIES-EGS-QG-1, indeed, resides in an overdense environment, at least within an aperture of 3 comoving Mpc. At present, this is the highest-redshift overdensity containing a massive quiescent galaxy38. However, based on these findings we could not determine whether RUBIES-EGS-QG-1 resides in a massive halo or in the extremely massive halo needed to reconcile the observed number density of the galaxy with expectations from galaxy formation simulations. Further spectroscopic follow-up observations will be critical for performing the thorough analysis of the spectroscopic completeness needed to obtain a robust estimate of the halo mass at the observed redshift and the projected evolution to the present day.

Theoretical predictions

We compared the existence and properties of RUBIES-EGS-QG-1 with five different large-volume simulations from recent literature, all of which simulated galaxy formation and evolution within the Λ cold dark matter (CDM) cosmological model. First, we evaluated the number density of massive quiescent galaxies in the different models:

The First Light and Reionisation Epoch Simulations (FLARES)92,93 uses the EAGLE model94,95 to perform hydrodynamical zoom simulations of regions in a volume of 3.2 comoving Gpc3, thereby probing rare haloes that would not appear in the EAGLE simulation. Using the measurements of ref. 30 based on the combination of FLARES and EAGLE, the predicted surface density of quiescent galaxies at z ≈ 4.5–5 and apparent magnitude like that of RUBIES-EGS-QG-1 (F200W < 24.5) is approximately 0.1–1 per degree squared or n ≈ 1 to 10 × 10−8 Mpc−3.

In the cosmological hydrodynamical simulation TNG300 of the IllustrisTNG project96–101, which simulated a comoving volume of 302 Mpc3 using the IllustrisTNG model, the population of massive quiescent galaxies appears in the simulation only at z ≈ 4.2 (ref. 32). At z = 5, we found a single system in the simulation that lies within the 3σ contours of the stellar mass and star formation rate of RUBIES-EGS-QG-1 (as measured within an aperture of twice the three-dimensional stellar half-mass radius), corresponding to a comoving number density of n = 3 × 10−8 Mpc−3.

In the cosmological hydrodynamical simulation Magneticum Pathfinder with a comoving volume of 180 Mpc3, lower-mass quiescent galaxies are present with number densities consistent with observations31, but no systems were reported at M* ≈ 1011 M⊙ at z ≈ 5, setting an upper limit on the number density of n < 1 × 10−7 Mpc−3.

The latest version of the semi-analytic Galaxy Evolution and Assembly (GAEA) model33,102–104 was run on the Millennium Simulation105 with a box length of 500 Mpc/h (where h = 0.73). Within this large volume, there were 14 quiescent galaxies with at z ≈ 4.9, that is n = 4 × 10−8 Mpc3.

The semi-analytic model SHARK v.2.0 (ref. 34) was run for the SURFS106 dark matter-only simulation volume with a box length of 210 Mpc/h where h = 0.6751. Following the methodology of ref. 34, which includes an estimate of the observational uncertainty of 0.25 dex on the inferred number density, the number density of massive () quiescent galaxies n = 2 × 10−8 Mpc3 at z = 5.

In summary, the different models all predict the existence of massive quiescent galaxies at high redshifts but with very low number densities at the redshift of RUBIES-EGS-QG-1 and with a typical value of n ≈ 5 × 10−8 Mpc−3 across the simulations. With an estimated observed number density of n ≈ 4 × 10−6 Mpc−3, RUBIES-EGS-QG-1 is, therefore, an outlier at the 2σ level at z ≈ 5, if we assume the theoretical model predictions to be accurate. It also implies that, instead of residing in a halo with Mhalo ≈ 1012 M⊙, the halo mass of RUBIES-EGS-QG-1 would be among the most massive haloes at z = 5, as Mhalo ≈ 1012.5–13 M⊙ in the simulations.

However, at higher redshift, the tension increases. Even for the solar-metallicity model, RUBIES-EGS-QG-1 formed its stars and quenched at z ≳ 5.5. The FLARES simulation predicted an extremely low source density of n < 1 × 10−8 Mpc−3 at z ≥ 5.5 (≲0.1 per degree squared), and the GAEA simulations predicted similarly low numbers (n = 6 × 10−9 Mpc−3 at z ≈ 6). Both reported zero such galaxies at z ≈ 7, which implies that n(z = 7) ≲ 1 × 10−9 Mpc−3. The relatively smaller volumes (TNG300 and Magneticum Pathfinder) do not seem to contain any quiescent galaxies more massive than M* > 1010.9 M⊙ at z ≥ 5 and do not contain any such massive galaxies at z > 6, even when considering star-forming galaxies. Therefore, if we also account for the unusual formation history of RUBIES-EGS-QG-1, this implies that the probability of finding a source like RUBIES-EGS-QG-1 within the small volume of the NIRCam imaging explored for the RUBIES survey thus far is approximately 0.03% (an outlier at the >2.8σ level), which strains current theoretical models.

Finally, we used the GAEA and TNG300 simulations to explore the possibility that RUBIES-EGS-QG-1 formed through a rapid, major merger of two moderately massive galaxies. We estimated a merger timescale of ~200–300 Myr (ref. 107). Because we did not find any signatures of a recent merger in the NIRCam imaging, the merger must have occurred at z > 6. We, therefore, searched for the nearest massive neighbour of galaxies with in the simulations at z ≳ 6. For GAEA, we found two massive pairs that are separated by <0.5 comoving Mpc at z = 6.2 and six such pairs at z = 5.7, corresponding to a number density of 6 to 20 × 10−9 Mpc−3. In TNG300, we found a single pair of massive galaxies at z = 6.0, which implies a number density for such equal-mass mergers of 3 × 10−8 Mpc−3. However, when tracing their merger history, we found that the pair did not merge until z = 5.0, which is inconsistent with the lack of merger signatures in the morphology of RUBIES-EGS-QG-1. These low number densities are, therefore, upper limits on the expected rate of equal-mass mergers of massive galaxies at high redshift, and they indicate that the formation of RUBIES-EGS-QG-1 through such a scenario is expected to be extremely rare.

NOEMA non-detection

RUBIES-EGS-QG-1 was also covered by NOEMA observations as part of project W20CK (PIs Buat and Zavala), which was originally designed to target dusty star-forming galaxy candidates at z > 3 (see ref. 108 for further details and the data reduction process). These observations allowed us to derive a 3σ upper limit at 1.1 mm of <1 mJy. Assuming a typical SED (a modified black-body function with a dust temperature of TD = 35 K and a dust emissivity index of β = 1.8) at z = 4.9, this flux density upper limit corresponds to an infrared luminosity of <8 × 1011 L⊙. Assuming the calibration between star formation rate and infrared luminosity of ref. 109, this implies a dust-obscured star formation rate of <120 M⊙ yr−1.

Supplementary information

Supplementary Figs. 1–6 and Tables 1–3.

Acknowledgements

We thank V. Buat, D. Burgarella and J. Zavala for sharing their NOEMA data and constraints on the dust-obscured star formation of RUBIES-EGS-QG-1. This work is partially based on observations carried out under project number W20CK with the IRAM NOEMA Interferometer. IRAM is supported by INSU/CNRS (France), MPG (Germany) and IGN (Spain). We thank C. Lagos for providing measurements from the SHARK simulation. This research was supported by the International Space Science Institute (ISSI) in Bern, through ISSI International Team Project No. 562. M.V.M., J.L. and B.W. acknowledge funding support from NASA through JWST-GO-4233. The Cosmic Dawn Center is funded by the Danish National Research Foundation (Grant No. DNRF140 to G.B., P.A.O. and K.E.W.). This work has received funding from the Swiss State Secretariat for Education, Research and Innovation (Contract No. MB22.00072) and the Swiss National Science Foundation (Project Grant No. 200020_207349 to P.A.O.). Support for this work was provided by the Brinson Foundation through a Brinson Prize Fellowship grant (D.J.S.). K.A.S. is a NHFP Hubble Fellow. Support for this work was provided by NASA through the NASA Hubble Fellowship Grant No. HST-HF2-51515.001-A awarded by the Space Telescope Science Institute, which is operated by the Association of Universities for Research in Astronomy, Incorporated, under NASA contract NAS 5-26555 (R.P.N.). This work is based on observations made with the NASA/ESA/CSA JWST. The data were obtained from the Mikulski Archive for Space Telescopes at the Space Telescope Science Institute, which is operated by the Association of Universities for Research in Astronomy, Inc., under NASA contract NAS 5-03127 for JWST. The observations in this work are associated with programmes ERS-1345, GO-2234, DDT-2750 and GO-4233. We gratefully acknowledge the CEERS and DDT-2750 teams for developing their observing programme with a zero-exclusive-access period.

Author contributions

A.d.G. and G.B. designed the NIRSpec MSA observations. A.d.G. drafted the main text and led the emission-line, environment and simulation analyses. D.J.S. led the stellar population analysis. G.B. performed the image and spectroscopic data reduction. S.C. led the morphological analysis. A.W. and I.L. measured the JWST and Hubble Space Telescope photometry. K.A.S., J.L. and M.V.M. contributed to the stellar population analysis. K.A.S., S.H.P. and K.E.W. contributed to the morphological analysis. F.V. provided the number density estimate. G.D.L. and M.H. provided measurements from the GAEA simulation. R.B., L.A.B., N.J.C., M.F., J.E.G., J.M., I.M., R.N., P.A.O., H-.W.R., F.V., B.W. and C.C.W. aided in the interpretation of the results. All authors contributed to the main text and Methods.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Astronomy thanks the anonymous reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Funding

Open access funding provided by Max Planck Society.

Data availability

The unprocessed JWST data are available through the Mikulski Archive for Space Telescopes. Reduced data from JWST underlying this work are publicly available in the DJA (https://dawn-cph.github.io/dja/), as described in refs. 9,46.

Code availability

All software packages used in this work are publicly available from GitHub: grizli52, msafit77, msaexp47 and Prospector15,55,56. The GALFIT software can be found on https://users.obs.carnegiescience.edu/peng/work/galfit/galfit.html.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41550-024-02424-3.

References

- 1.Labbé, I. et al. A population of red candidate massive galaxies 600 Myr after the Big Bang. Nature616, 266–269 (2023). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Behroozi, P. & Silk, J. The most massive galaxies and black holes allowed by ΛCDM. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc.477, 5382–5387 (2018). [Google Scholar]

- 3.Boylan-Kolchin, M. Stress testing ΛCDM with high-redshift galaxy candidates. Nat. Astron.7, 731–735 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Xiao, M. et al. Accelerated formation of ultra-massive galaxies in the first billion years. Nature635, 311–315 (2024). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Glazebrook, K. et al. A massive, quiescent galaxy at a redshift of 3.717. Nature544, 71–74 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Valentino, F. et al. Quiescent galaxies 1.5 billion years after the Big Bang and their progenitors. Astrophys. J.889, 93 (2020). [Google Scholar]

- 7.Carnall, A. C. et al. A massive quiescent galaxy at redshift 4.658. Nature619, 716–719 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Madau, P. & Dickinson, M. Cosmic star-formation history. Annu. Rev. Astron. Astrophys.52, 415–486 (2014). [Google Scholar]

- 9.Valentino, F. et al. An atlas of color-selected quiescent galaxies at z > 3 in public JWST fields. Astrophys. J.947, 20 (2023). [Google Scholar]

- 10.Carnall, A. C. et al. A surprising abundance of massive quiescent galaxies at 3 < z < 5 in the first data from JWST CEERS. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc.520, 3974–3985 (2023). [Google Scholar]

- 11.Urbano Stawinski, S. M. et al. Spectroscopic confirmation of an ultra-massive galaxy in a protocluster at z ~ 4.9. Open J. Astrophys.7, 46 (2024). [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kewley, L. J., Dopita, M. A., Sutherland, R. S., Heisler, C. A. & Trevena, J. Theoretical modeling of starburst galaxies. Astrophys. J.556, 121–140 (2001). [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kewley, L. J., Groves, B., Kauffmann, G. & Heckman, T. The host galaxies and classification of active galactic nuclei. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc.372, 961–976 (2006). [Google Scholar]

- 14.Goto, T. A catalogue of local E+A (post-starburst) galaxies selected from the Sloan Digital Sky Survey Data Release 5. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc.381, 187–193 (2007). [Google Scholar]

- 15.Johnson, B. et al. dfm/python-fsps: python-fsps v0.4.0. Zenodohttps://zenodo.org/records/4577191 (2021).

- 16.Beverage, A. G. et al. Carbon and iron deficiencies in quiescent galaxies at z = 1–3 from JWST-SUSPENSE: implications for the formation histories of massive galaxies. Astrophys. J. (in the press).

- 17.de Graaff, A., Pillepich, A. & Rix, H-W. An early dark matter-dominated phase in the assembly history of Milky Way-mass galaxies suggested by the TNG50 simulation and JWST observations. Astrophys. J. Lett.967, L40 (2024). [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hopkins, P. F., Murray, N., Quataert, E. & Thompson, T. A. A maximum stellar surface density in dense stellar systems. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc.401, L19–L23 (2010). [Google Scholar]

- 19.Grudić, M. Y., Hopkins, P. F., Quataert, E. & Murray, N. The maximum stellar surface density due to the failure of stellar feedback. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc.483, 5548–5553 (2019). [Google Scholar]

- 20.Franx, M. et al. Structure and star formation in galaxies out to z = 3: evidence for surface density dependent evolution and upsizing. Astrophys. J.688, 770–788 (2008). [Google Scholar]

- 21.Whitaker, K. E. et al. Predicting quiescence: the dependence of specific star formation rate on galaxy size and central density at 0.5 < z < 2.5. Astrophys. J.838, 19 (2017). [Google Scholar]

- 22.Barro, G. et al. CANDELS: the progenitors of compact quiescent galaxies at z ~ 2. Astrophys. J.765, 104 (2013). [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bouwens, R. J. et al. Reionization era bright emission line survey: selection and characterization of luminous interstellar medium reservoirs in the z > 6.5 Universe. Astrophys. J.931, 160 (2022). [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zavala, J. A. et al. A dusty star-forming galaxy at z = 6 revealed by strong gravitational lensing. Nat. Astron.2, 56–62 (2018). [Google Scholar]

- 25.Strandet, M. L. et al. ISM properties of a massive dusty star-forming galaxy discovered at z ~ 7. Astrophys. J. Lett.842, L15 (2017). [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wang, B. et al. RUBIES: evolved stellar populations with extended formation histories at z ~ 7–8 in candidate massive galaxies identified with JWST/NIRSpec. Astrophys. J. Lett.969, L13 (2024). [Google Scholar]

- 27.Schouws, S. et al. Significant dust-obscured star formation in luminous Lyman-break galaxies at z ~ 7–8. Astrophys. J.928, 31 (2022). [Google Scholar]

- 28.Planck Collaboration. Planck 2018 results. VI. Cosmological parameters. Astron. Astrophys.641, A6 (2020). [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wechsler, R. H. & Tinker, J. L. The connection between galaxies and their dark matter halos. Annu. Rev. Astron. Astrophys.56, 435–487 (2018). [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lovell, C. C. et al. First light and reionisation epoch simulations (FLARES). VIII. The emergence of passive galaxies at z ≥ 5. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc.525, 5520–5539 (2023). [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kimmig, L. C. et al. Blowing out the candle: how to quench galaxies at high redshift – an ensemble of rapid starbursts, AGN feedback and environment. Preprint at https://arxiv.org/abs/2310.16085 (2023).

- 32.Hartley, A. I. et al. The first quiescent galaxies in TNG300. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc.522, 3138–3144 (2023). [Google Scholar]

- 33.De Lucia, G., Fontanot, F., Xie, L. & Hirschmann, M. Tracing the quenching journey across cosmic time. Astron. Astrophys.687, A68 (2024).

- 34.Lagos, Cd. P. et al. Quenching massive galaxies across cosmic time with the semi-analytic model SHARK V2.0. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc.531, 3551–3578 (2024). [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zavala, J. A. et al. The SCUBA-2 cosmology legacy survey: the EGS deep field. I. Deep number counts and the redshift distribution of the recovered cosmic infrared background at 450 and 850 μm. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc.464, 3369–3384 (2017). [Google Scholar]

- 36.Arrabal Haro, P. et al. Confirmation and refutation of very luminous galaxies in the early Universe. Nature622, 707–711 (2023). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Naidu, R. P. et al. Schrodinger’s galaxy candidate: puzzlingly luminous at z ≈ 17, or dusty/quenched at z ≈ 5? Preprint at https://arxiv.org/abs/2208.02794 (2022).

- 38.Kakimoto, T. et al. A massive quiescent galaxy in a group environment at z = 4.53. Astrophys. J.963, 49 (2024). [Google Scholar]

- 39.Di Matteo, T., Springel, V. & Hernquist, L. Energy input from quasars regulates the growth and activity of black holes and their host galaxies. Nature433, 604–607 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Nanayakkara, T. et al. A population of faint, old, and massive quiescent galaxies at 3 < z < 4 revealed by JWST NIRSpec spectroscopy. Sci. Rep.14, 3724 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Glazebrook, K. et al. A massive galaxy that formed its stars at z ≈ 11. Nature628, 277–281 (2024). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 42.Antwi-Danso, J. et al. The FENIKS survey: spectroscopic confirmation of massive quiescent galaxies at z ~ 3-5. Preprint at https://arxiv.org/abs/2307.09590 (2023).

- 43.Ferruit, P. et al. The near-infrared spectrograph (NIRSpec) on the James Webb Space Telescope. II. Multi-object spectroscopy (MOS). Astron. Astrophys.661, A81 (2022). [Google Scholar]

- 44.Koekemoer, A. M. et al. CANDELS: The Cosmic Assembly Near-infrared Deep Extragalactic Legacy Survey—The Hubble Space Telescope observations, imaging data products, and mosaics. Astrophys. J. Suppl. Ser.197, 36 (2011). [Google Scholar]

- 45.Grogin, N. A. et al. CANDELS: The Cosmic Assembly Near-infrared Deep Extragalactic Legacy Survey. Astrophys. J. Suppl. Ser.197, 35 (2011). [Google Scholar]

- 46.de Graaff, A. et al. RUBIES: a complete census of the bright and red distant Universe with JWST/NIRSpec. Preprint at https://arxiv.org/abs/2409.05948 (2024).

- 47.Brammer, G. msaexp: NIRSpec analysis tools. Zenodo10.5281/zenodo.7299500 (2023).

- 48.Heintz, K. E. et al. The JWST-PRIMAL legacy survey. A JWST/NIRSpec reference sample for the physical properties and Lyman-α absorption and emission of ~500 galaxies at z = 5.5–13.4. Preprint at https://arxiv.org/abs/2404.02211 (2024).

- 49.Horne, K. An optimal extraction algorithm for CCD spectroscopy. Publ. Astron. Soc. Pac.98, 609–617 (1986). [Google Scholar]

- 50.Maseda, M. V. et al. JWST/NIRSpec measurements of extremely low metallicities in high equivalent width Lyα emitters. Astrophys. J.956, 11 (2023). [Google Scholar]

- 51.Bagley, M. B. et al. CEERS epoch 1 NIRCam imaging: reduction methods and simulations enabling early JWST science results. Astrophys. J. Lett.946, L12 (2023). [Google Scholar]

- 52.Brammer, G. grizli. GitHubhttps://github.com/gbrammer/grizli/ (2023).

- 53.Weibel, A. et al. Galaxy build-up in the first 1.5 Gyr of cosmic history: insights from the stellar mass function at z ~ 4–9 from JWST NIRCam observations. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc.533, 1808–1838 (2024).

- 54.Bertin, E. & Arnouts, S. SExtractor: software for source extraction. Astron. Astrophys. Suppl. Ser.117, 393–404 (1996). [Google Scholar]

- 55.Johnson, B. & Leja, J. Bd-J/Prospector: initial release. GitHubhttps://github.com/bd-j/prospector (2017).

- 56.Leja, J., Johnson, B. D., Conroy, C., van Dokkum, P. G. & Byler, N. Deriving physical properties from broadband photometry with Prospector: description of the model and a demonstration of its accuracy using 129 galaxies in the local Universe. Astrophys. J.837, 170 (2017). [Google Scholar]

- 57.Conroy, C., Gunn, J. E. & White, M. The propagation of uncertainties in stellar population synthesis modeling. I. The relevance of uncertain aspects of stellar evolution and the initial mass function to the derived physical properties of galaxies. Astrophys. J.699, 486–506 (2009). [Google Scholar]

- 58.Conroy, C. & Gunn, J. E. The propagation of uncertainties in stellar population synthesis modeling. III. Model calibration, comparison, and evaluation. Astrophys. J.712, 833–857 (2010). [Google Scholar]

- 59.Sánchez-Blázquez, P. et al. Medium-resolution Isaac Newton Telescope library of empirical spectra. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc.371, 703–718 (2006). [Google Scholar]

- 60.Choi, J. et al. Mesa Isochrones and Stellar Tracks (MIST). I. Solar-scaled models. Astrophys. J.823, 102 (2016). [Google Scholar]

- 61.Dotter, A. MESA Isochrones and Stellar Tracks (MIST) 0: methods for the construction of stellar isochrones. Astrophys. J. Suppl. Ser.222, 8 (2016). [Google Scholar]

- 62.Chabrier, G. Galactic stellar and substellar initial mass function. Publ. Astron. Soc. Pac.115, 763–795 (2003). [Google Scholar]

- 63.Bunker, A. J. et al. JADES NIRSpec initial data release for the Hubble ultra deep field: redshifts and line fluxes of distant galaxies from the deepest JWST cycle 1 NIRSpec multi-object spectroscopy. Astron. Astrophys.690, A288 (2024).

- 64.Leja, J., Carnall, A. C., Johnson, B. D., Conroy, C. & Speagle, J. S. How to measure galaxy star formation histories. II. Nonparametric models. Astrophys. J.876, 3 (2019). [Google Scholar]

- 65.Kriek, M. & Conroy, C. The dust attenuation law in distant galaxies: evidence for variation with spectral type. Astrophys. J. Lett.775, L16 (2013). [Google Scholar]

- 66.Speagle, J. S. DYNESTY: a dynamic nested sampling package for estimating Bayesian posteriors and evidences. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc.493, 3132–3158 (2020). [Google Scholar]

- 67.Curtis-Lake, E. et al. Spectroscopic confirmation of four metal-poor galaxies at z = 10.3–13.2. Nat. Astron.7, 622–632 (2023). [Google Scholar]

- 68.Leja, J. et al. An older, more quiescent Universe from panchromatic SED fitting of the 3D-HST survey. Astrophys. J.877, 140 (2019). [Google Scholar]

- 69.Wang, B. et al. Quantifying the effects of known unknowns on inferred high-redshift galaxy properties: burstiness, IMF, and nebular physics. Astrophys. J.963, 74 (2024). [Google Scholar]

- 70.Papovich, C., Finkelstein, S. L., Ferguson, H. C., Lotz, J. M. & Giavalisco, M. The rising star formation histories of distant galaxies and implications for gas accretion with time. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc.412, 1123–1136 (2011). [Google Scholar]

- 71.Behroozi, P., Wechsler, R. H., Hearin, A. P. & Conroy, C. UniverseMachine: The correlation between galaxy growth and dark matter halo assembly from z = 0–10. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc.488, 3143–3194 (2019). [Google Scholar]

- 72.Beverage, A. G. et al. The heavy metal survey: the evolution of stellar metallicities, abundance ratios, and ages of massive quiescent galaxies since z ~ 2. Astrophys. J.966, 234 (2024).

- 73.Conroy, C. Modeling the panchromatic spectral energy distributions of galaxies. Annu. Rev. Astron. Astrophys.51, 393–455 (2013). [Google Scholar]

- 74.Whitler, L. et al. Star formation histories of UV-luminous galaxies at z ≃ 6.8: implications for stellar mass assembly at early cosmic times. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc.519, 5859–5881 (2023). [Google Scholar]

- 75.Conroy, C. & van Dokkum, P. G. The stellar initial mass function in early-type galaxies from absorption line spectroscopy. II. Results. Astrophys. J.760, 71 (2012). [Google Scholar]

- 76.Groves, B. A., Heckman, T. M. & Kauffmann, G. Emission-line diagnostics of low-metallicity active galactic nuclei. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc.371, 1559–1569 (2006). [Google Scholar]

- 77.de Graaff, A. et al. Ionised gas kinematics and dynamical masses of z ≳ 6 galaxies from JADES/NIRSpec high-resolution spectroscopy. Astron. Astrophys.684, A87 (2024).

- 78.Wang, B. et al. RUBIES: JWST/NIRSpec Confirmation of an infrared-luminous, broad-line little red dot with an ionized outflow. Preprint at https://arxiv.org/abs/2403.02304 (2024).

- 79.Veilleux, S. & Osterbrock, D. E. Spectral classification of emission-line galaxies. Astrophys. J. Suppl. Ser.63, 295 (1987). [Google Scholar]

- 80.Newman, A. B., Belli, S., Ellis, R. S. & Patel, S. G. Resolving quiescent galaxies at z ≳ 2. I. Search for gravitationally lensed sources and characterization of their structure, stellar populations, and line emission. Astrophys. J.862, 125 (2018). [Google Scholar]

- 81.van Dokkum, P. G. et al. Forming compact massive galaxies. Astrophys. J.813, 23 (2015). [Google Scholar]

- 82.Bezanson, R. et al. 1D kinematics from stars and ionized gas at z ~ 0.8 from the LEGA-C spectroscopic survey of massive galaxies. Astrophys. J. Lett.868, L36 (2018). [Google Scholar]

- 83.Peng, C. Y., Ho, L. C., Impey, C. D. & Rix, H.-W. Detailed structural decomposition of galaxy images. Astron. J.124, 266–293 (2002). [Google Scholar]

- 84.Peng, C. Y., Ho, L. C., Impey, C. D. & Rix, H.-W. Detailed decomposition of galaxy images. II. Beyond axisymmetric models. Astron. J.139, 2097–2129 (2010). [Google Scholar]

- 85.van der Wel, A. et al. Structural parameters of galaxies in CANDELS. Astrophys. J. Suppl. Ser.203, 24 (2012). [Google Scholar]

- 86.Cutler, S. E. et al. Two distinct classes of quiescent galaxies at cosmic noon revealed by JWST PRIMER and UNCOVER. Astrophys. J. Lett.967, L23 (2024).

- 87.Szomoru, D. et al. Confirmation of the compactness of a z = 1.91 quiescent galaxy with Hubble Space Telescope’s wide field camera 3. Astrophys. J. Lett.714, L244–L248 (2010). [Google Scholar]

- 88.Ito, K. et al. Size–stellar mass relation and morphology of quiescent galaxies at z ≥ 3 in public JWST fields. Astrophys. J.964, 192 (2024).

- 89.Suess, K. A., Kriek, M., Price, S. H. & Barro, G. Color gradients along the quiescent galaxy sequence: clues to quenching and structural growth. Astrophys. J. Lett.899, L26 (2020). [Google Scholar]

- 90.Harikane, Y. et al. SILVERRUSH. VIII. Spectroscopic identifications of early large-scale structures with protoclusters over 200 Mpc at z ~ 6–7: strong associations of dusty star-forming galaxies. Astrophys. J.883, 142 (2019). [Google Scholar]

- 91.Maseda, M. V. et al. The NIRSpec wide GTO survey. Astron. Astrophys.689, A73 (2024).

- 92.Vijayan, A. P. et al. First Light And Reionization Epoch Simulations (FLARES). II. The photometric properties of high-redshift galaxies. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc.501, 3289–3308 (2021). [Google Scholar]

- 93.Lovell, C. C. et al. First Light And Reionization Epoch Simulations (FLARES). I. Environmental dependence of high-redshift galaxy evolution. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc.500, 2127–2145 (2021). [Google Scholar]

- 94.Crain, R. A. et al. The EAGLE simulations of galaxy formation: calibration of subgrid physics and model variations. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc.450, 1937–1961 (2015). [Google Scholar]

- 95.Schaye, J. et al. The EAGLE project: simulating the evolution and assembly of galaxies and their environments. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc.446, 521–554 (2015). [Google Scholar]

- 96.Nelson, D. et al. First results from the IllustrisTNG simulations: the galaxy colour bimodality. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc.475, 624–647 (2018). [Google Scholar]

- 97.Nelson, D. et al. The IllustrisTNG simulations: public data release. Comput. Astrophys. Cosmol.6, 2 (2019). [Google Scholar]

- 98.Pillepich, A. et al. First results from the IllustrisTNG simulations: the stellar mass content of groups and clusters of galaxies. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc.475, 648–675 (2018). [Google Scholar]

- 99.Springel, V. et al. First results from the IllustrisTNG simulations: matter and galaxy clustering. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc.475, 676–698 (2017). [Google Scholar]

- 100.Marinacci, F. et al. First results from the IllustrisTNG simulations: radio haloes and magnetic fields. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc.480, 5113–5139 (2018). [Google Scholar]

- 101.Naiman, J. P. et al. First results from the IllustrisTNG simulations: a tale of two elements – chemical evolution of magnesium and europium. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc.477, 1206–1224 (2018). [Google Scholar]

- 102.Hirschmann, M., De Lucia, G. & Fontanot, F. Galaxy assembly, stellar feedback and metal enrichment: the view from the GAEA model. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc.461, 1760–1785 (2016). [Google Scholar]