Abstract

Background

Extracting structured data from free-text medical records is laborious and error-prone. Traditional rule-based and early neural network methods often struggle with domain complexity and require extensive tuning. Large language models (LLMs) offer a promising solution but must be tailored to nuanced clinical knowledge and complex, multipart entities.

Methods

We developed a flexible, end-to-end LLM pipeline to extract diagnoses, per-specimen anatomical-sites, procedures, histology, and detailed immunohistochemistry results from pathology reports. A human-in-the-loop process to create validated reference annotations for a development set of 152 kidney tumor reports guided iterative pipeline refinement. To drive nuanced assessment of performance we developed a comprehensive error ontology—categorizing by clinical significance (major vs. minor), source (LLM, manual annotation, or insufficient instructions), and contextual origin. The finalized pipeline was applied to 3,520 internal reports (of which 2,297 had pre-existing templated data available for cross referencing) and evaluated for adaptability using 53 publicly available breast cancer pathology reports.

Results

After six iterations, major LLM errors on the development set decreased to 0.99% (14/1413 entities). We identified 11 key contexts from which complications arose- including medical history integration, entity linking, and specification granularity- which provided valuable insight in understanding our research goals. Using the available templated data as a cross reference, we achieved a macro-averaged F1 score of 0.99 for identifying six kidney tumor subtypes and 0.97 for detecting metastasis. When adapted to the breast dataset, three iterations were required to align with domain-specific instructions, attaining 89% agreement with curated data.

Conclusion

This work illustrates that LLM-based extraction pipelines can achieve near expert-level accuracy with carefully constructed instructions and specific aims. Beyond raw performance metrics, the iterative process itself—balancing specificity and clinical relevance—proved essential. This approach offers a transferable blueprint for applying emerging LLM capabilities to other complex clinical information extraction tasks.

Introduction:

Extracting structured information from free-text electronic medical records (EMR) is challenging due to their narrative structure, specialized terminology, and inherent variability.1 Historically, this process has been labor-intensive and error-prone, requiring manual review by medical professionals,2–4 thereby hindering large-scale retrospective studies and real-world evidence generation.5 Consequently, there is a pressing need for automated and reliable methods to distill clinically relevant information from unstructured EMR text.6

Natural language processing (NLP) solutions, including rule-based systems and early neural models, have struggled with the nuances of the medical domain.7,8 While transformer-based architectures like ClinicalBERT,9 GatorTron,10 and others,11–13 furthered the state-of-the art, they often require extensive fine-tuning on large annotated datasets, which are costly and time-consuming to create.14,15 The challenge is particularly acute in specialized tasks like extraction of immunohistochemistry (IHC) results from pathology reports, which requires identifying and linking pairs of tests and results to the correct specimen, resolving synonyms, and navigating diverse terminology.

The rapid emergence of generative large language models (LLMs)16 offers a transformative approach. Their vast parameter counts and ability to process extensive context windows enable them to retain and “reason” over substantial amounts of domain-specific knowledge without fine-tuning.17–20 Natural language prompts further allow flexible modification, enabling rapid iteration and adaptation to new entities and instructions.21,22

Recent studies report promising results using LLMs for text-to-text medical information extraction.23 Initial efforts have successfully extracted singular/non-compound report-level information, such as patient characteristics from clinical notes,24 and tumor descriptors/diagnosis from radiology25 and pathology reports.26,27 Studies have also demonstrated the potential for extracting inferred conclusions such as classifying radiology findings28 and cancer-related symptoms4. However, challenges remain, particularly factually incorrect reasoning,29,30 and the potential for information loss when forcing complex medical concepts into discrete categories.31

Evaluating LLM performance is complicated by the lack of standardized error categorization that accounts for clinical significance and the limitations of traditional metrics like exact match accuracy, which are ill-suited for open-ended generation.32–36 For example, misclassifying a test result as “negative” versus “positive” is substantially different than minor grammatical discrepancies between labels e.g. “positive, diffusely” versus “diffuse positive”. Furthermore, many existing clinical NLP datasets utilize BERT-style entity tagging, limiting their use for benchmarking end-to-end information extraction.33,37 Nonetheless, our lack of pre-annotated data, high degree of entity complexity, and desire for flexibility- coupled with the rapidly improving performance of LLMs38- prompted us to explore their potential.

We present a novel approach to end-to-end information extraction from real-world clinical data that addresses these challenges through three key innovations: flexible prompt templates with a centralized schema for standardized terminology, multi-step LLM interactions with chain-of-thought reasoning, and a comprehensive error ontology developed through iterative “human in the loop”39 refinement. We demonstrate this approach on renal cell carcinoma (RCC) pathology reports, extracting and normalizing report-level diagnosis, per-subpart/specimen histology, procedure, anatomical site, and detailed multipart IHC results for 30+ assays at both the specimen and tissue-block level—a complex multi-entity extraction task that tests the limits of current approaches. We focus on RCC given the high volume of RCC patients treated at UT Southwestern, the diversity of RCC subtypes and wide variety of ancillary studies used for subtyping, and a multidisciplinary UTSW Kidney Cancer Program recognized with a Specialized Program of Research Excellence (SPORE) award from the National Cancer Institute.

First, we detail our pipeline development through the creation of a validated “gold-label” dataset using 152 kidney tumor pathology reports. Within this we explore our error ontology, used to classify discrepancies based on clinical significance, source (LLM, manual annotation, or insufficient instructions), and crucially, the contexts from which errors arose. We then apply and validate our pipeline using a set of 3,520 internal kidney tumor reports. Finally, we assess portability using 53 invasive breast cancer pathology reports from an independent, public repository.

Beyond the technical specifics of our pipeline, we regard the broader considerations arising during development as particularly important. Specifically, our focus shifted from engineering prompts that could extract information, to precisely defining what information to extract and why. This experience underscores that, as AI approaches human-level intelligence in many domains,38 success will increasingly hinge on the clear articulation of objectives, rather than on singular workflow methodologies. As such, by detailing both our success and pitfalls, we hope to provide a roadmap of generalizable context and considerations for future AI-powered clinical information extraction workflows.

Methods:

Defining the Task

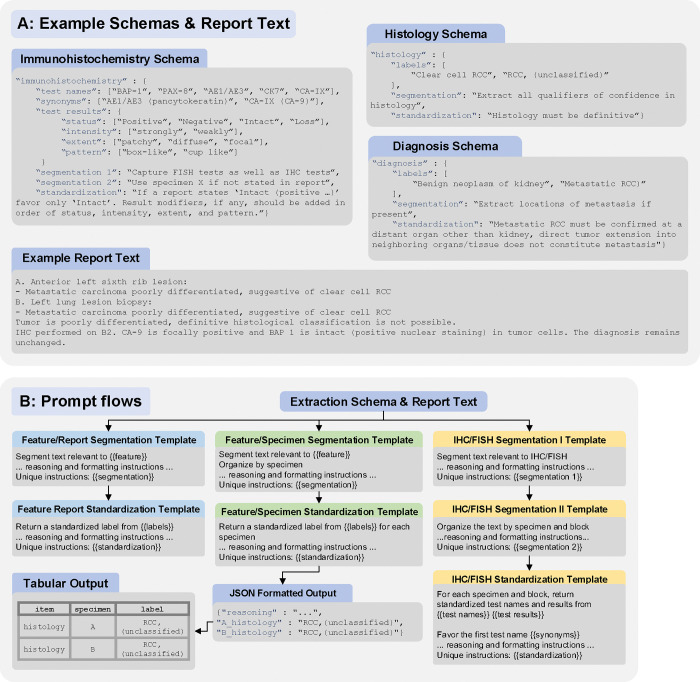

Initial entities to extract and normalize from reports included: (1) report-level ICD-10 diagnosis code; (2) per-subpart histology, procedure type, and anatomical site; and (3) detailed specimen and tissue block-level IHC/FISH (fluorescence in situ hybridization) test names and results. We first defined an “extraction schema”, outlining standardized labels, a structured vocabulary of terms and preferred synonyms for IHC results, and unique instructions for each entity; see Figure 1A.

Figure 1:

(A) Abbreviated examples of the extraction schema for immunohistochemistry [IHC] and fluorescence in-situ hybridization [FISH]), histology, and diagnosis, demonstrating the inclusion of item specific instructions, standardized labels, and a structured vocabulary for IHC test reporting. An abbreviated report text is included for reference. (B) Overview of pipeline steps. Each set included base instructions consistent across entities, and placeholders for entity-specific instructions and labels that could be easily “hot-swapped”, with the {{}} indicating where information from the schema is pasted in. All template sets include initial prompts to segment and organize text, a subsequent standardization prompt to normalize labels and produce structured output, and a final python step for parsing into tabular data. The full output from segmentation steps, both reasoning and the segmented text, is passed to subsequent steps.

Labels for procedure and histology were derived from the contemporary College of American Pathologists (CAP) Cancer Protocol Templates for kidney resection and biopsy.40,41 Labels for anatomical site and IHC, along with specialized labels such as the diagnosis “Metastatic RCC” were developed with guidance from kidney cancer and pathology experts.

Prompt Templates

We used Microsoft Prompt flow42 to organize the workflow as a directed acyclic graph, where each node represents either a Python code execution or an LLM request using a specific prompt template. To enhance portability across different reports and entities, we designed reusable prompt templates with a modular structure. We developed three distinct template sets, each optimized for a specific class of entity: The “feature report” set for entities with a single label per report, such as diagnosis; The “feature specimen” set for entities with one label per specimen/subpart; And an IHC/FISH specific set as it uniquely requires matching any number of specimens, blocks, test names, and test results; see Figure 1B.

Importantly, all prompts included instructions to provide “reasoning”, and this output is passed along to subsequent prompts to develop a “chain-of-thought”. This both enhances performance,43 as well as furthers our understanding of both specific limitations and usage of the instructions. Full schema and templates are included in the supplement and a GitHub repository for implementation can be found at github.com/DavidHein96/prompts_to_table.

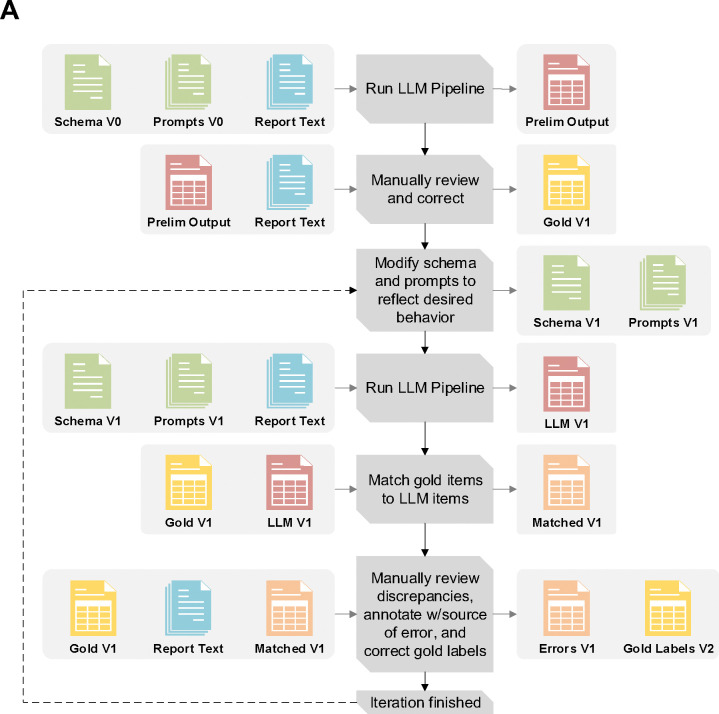

Creating a Gold-Label Set

We first selected 152 reports representing a spectrum of differing contexts (multi-part/multiple specimens, inhouse and outside consultations, biopsies and surgical nephrectomy specimens) using a predefined list of known RCC patients. All data was collected under IRB STU 022015–015. We then adopted an iterative approach, working in partnership with the LLM, to refining the gold-label annotations and pipeline; Figure 2A.39 Preliminary prompts and schemas pipeline processed the 152 reports to generate rough tabular outputs, allowing for expedited manual review and reducing initial annotation burden for creating the initial gold-label set. As iterations progressed, discordant outputs between the LLM and gold-labels informed both adjustments to prompts/schemas and our understanding of error contexts. All development used GPT-4o 2024–05-13 via a secure HIPAA compliant Azure API.44

Figure 2:

(A) Overview of the iterative pipeline improvement and gold label set creation process. After completing each iteration, the schema, prompts, LLM outputs, and gold labels are incrementally versioned e.g. V1, V2, V3 etc. (B) Flow chart for documenting discrepancy source and severity for an iteration. Issue contexts are introduced as questions needing to be asked about both workflow requirements and how certain kinds of deviations from instructions might need to be addressed. For the final two contexts: “Formatting only” refers to discrepancies that are purely due to standardized spellings/punctuation (BAP-1 vs BAP1), while “Blatantly Incorrect Reasoning” refers to errors not arising from any given nuanced context (e.g. hallucinating a test result not present in the report text)

Creating an Error Ontology

A structured error ontology was developed to provide a framework for classifying the sources, severity, and context of discrepancies between the LLM outputs and the gold-labels. The ontology comprises three sources of discrepancy: LLM, manual annotations (errors introduced to the gold-label set by incorrect or insufficient annotation in a prior step), and schema issues. Both LLM and manual annotation discrepancies were further subclassified as of “major” or “minor” severity based on their potential impact on clinical interpretation or downstream analysis. Schema issues represent instances where the LLM and gold-labels were discordant, yet both appeared to have adhered to the provided instructions. In these cases, the instructions themselves were found to be insufficient or ambiguous.

To provide finer details on the issues we encountered, we documented the contexts in which discrepancies arose. A flow chart for defining and documenting discrepancies as well as a brief introduction to the error context is provided in Figure 2B. Detailed examples for a subset of contexts are given in Table 1, with the remainder plus additional examples in STable1. For each context, we first provide two potential labels for an entity arising from insufficient instructions in the given context. This is followed by our addressing methodology, and further examples of LLM or annotation error severity in similar contexts- provided that we found our instructions to be sufficient.

Table 1:

Issue Context Examples and Corrective Actions

| 1.1 Integrating Medical History | |||

| Report Text † |

A. Soft tissue mass, parasplenic

- Poorly differentiated carcinoma, consistent with known renal cell carcinoma Note: Prior history of papillary renal cell carcinoma is noted. |

||

| Discordant Labels | A_histology: Papillary renal cell carcinoma | A_histology: Poorly differentiated carcinoma | |

| Context | - Should we label this specimen as papillary RCC inferring from the medical history, or only use the current report histology (poorly differentiated carcinoma)? - The goal is to avoid automatically applying historical findings unless they are truly consistent with current specimen details. |

||

| Addressing Action | - Added to histology standardization instructions: “If a specimen is consistent or compatible with a known histology you may use that histology as part of your choice of a label, but ensure that the histology you choose is still applicable to the current specimen.” | ||

| Continued Error Severity Examples | - Major: If the report were to instead lack the “consistent with known renal cell carcinoma” modifier, then the histology “Papillary RCC” would be a major error as it would be reporting medical history alone. - Minor: Labeling the specimen “RCC, no subtype specified” instead of “papillary RCC,” even though the text leans toward papillary (note the specimen is only consistent with renal cell carcinoma- no subtype specified). While not optimal, it does not fundamentally misclassify the specimen. |

||

| 1.2 Mixed Known/Unknown Entity Linking | |||

| Report Text |

Review of outside slides

A. Skin, abdomen - Metastatic carcinoma, IHC profile suggestive of renal primary B. Skin, upper back - Metastatic carcinoma, IHC profile suggestive of renal primary . . . IHC slides are positive for CK7, . . . IHC stains were performed on block A2 and showed the following reactivity: PAX8 * Positive |

||

| Discordant Labels |

X_block_X0_IHC_CK7: Positive

A_block_A2_IHC_PAX-8: Positive |

A_block_A0_IHC_CK7: Positive

B_block_B0_IHC_CK7: Positive A_block_A2_IHC_PAX-8: Positive |

|

| Context | - The initial schema instructed the use of specimen “X” as a stand-in when it is not clear which specimen was used for a test. - In cases with multiple specimens of identical histology, for IHC tests lacking a specified specimen the LLM would continue to provide a duplicate set of results for all specimens. |

||

| Addressing Action | - A brief description of this situation along with a properly constructed output was added to the IHC/FISH segmentation II and standardization prompt. This new example provided additional reinforcement to maintain using X when specimen/block is not specified and the provided names only for the tests for which specimen/block correspondence is explicit. | ||

| Continued Error Severity Examples | - Major: If the duplicated set of results was returned for both A & B but B was benign tissue. - Minor: Continued duplicated results, but only in the context of both specimens containing identical histology. |

||

| 1.3 Relevance of Multiple Labels | |||

| Report Text |

A. Right kidney and adrenal gland, radical nephrectomy:

- Renal cell carcinoma, clear-cell type - Adrenal gland, negative for malignancy |

||

| Discordant Labels | A_anatomical-site: Kidney, right; Adrenal gland | A_anatomical-site: Kidney, right | |

| Context | - The original instructions required listing all anatomical sites in the specimen, as some specimens have multiple anatomical sites. - In the above report, the adrenal gland and kidney are anatomical sites in the same subpart- however only the kidney is positive for RCC. - Ambiguity arose over whether to include both sites in the label for such contexts. |

||

| Addressing Action | - It was decided that for our purposes, we wanted the “anatomical site” field to continue to capture the primary organs/tissues removed for a specimen with no carve outs for histology. As such, in this case we would rely on the diagnosis and histology fields to guide our understanding that this was NOT a case of adrenal metastasis. | ||

| Continued Error Severity Examples | - Major: An anatomical site of only “Adrenal gland”, omitting the more important site. - Minor: An anatomical site of only “Right kidney”. Although the adrenal gland is missing, because it is only benign tissue and not an RCC metastasis, its omission does not substantially affect planned downstream analysis. |

||

| 1.4 Specification Issue- Granularity | |||

| Report Text | IHC performed on A2. Tumor cells are diffusely positive for CAIX in a membranous pattern | ||

| Discordant Labels | A_block_A2_IHC_CAIX: Positive, diffuse membranous | A_block_A2_IHC_CAIX: Positive, diffuse | |

| Context | - In our original schema, we attempted to provide a list of all possible IHC results to choose from. - After review we found this to be entirely impractical as the space of possible test results became enormous. - We needed to precisely define the granularity of test results that we were interested in. |

||

| Addressing Action | - We shifted to a more modular schema comprising four dimensions—status, intensity, extent, and pattern—each with its own controlled vocabulary (see Figure 1A for an example). - Under this new approach, the LLM is instructed to sequentially append any applicable modifiers (intensity, then extent, then pattern) to the primary status label, omitting those not present. |

||

| Continued Error Severity Examples | - Major: Returning only “Positive” as in RCC, we are very interested in detailed CAIX staining patterns. - Minor: If in the example report CAIX had additional describers/modifiers that we are not interested in, thus are not in the schema, and are then returned by the LLM. These additional modifiers would not be factually incorrect, but would be beyond the standardized level of detail that we desire. |

||

| 1.5 Specification Issues- Ontology | |||

| Report Text |

C. Peripancreatic mass, excision:

- Metastatic renal cell carcinoma, clear cell type |

||

| Discordant Labels | C_anatomical-site: Other-peripancreatic mass | C_anatomical-site: Pancreas | |

| Context | - Because the mass is described as being peripancreatic, is it precise to label the site as pancreas? - Additionally, in the context of metastasis, the histology of a tissue specimen should not be mistaken for its anatomical site |

||

| Addressing Action | - Added to anatomical site standardization instructions: “Analyze whether there are any position or direction terms that are relevant, for example a ‘peripancreatic mass’ would not be captured as ‘Pancreas’ as this refers to a mass in the tissue surrounding the pancreas. ... renal cell carcinoma that has metastasized to the left lung would ONLY have the anatomical site ‘Lung, left’ if the specimen ONLY contains lung tissue.” | ||

| Continued Error Severity Examples | - Major: Continued use of the label “pancreas” would be considered major as we have now instructed that the anatomical site must be consistent with the originating tissue. - Minor: In some cases, continued usage of the “Other” label vs a specific provided label can be justified as an minor error if the site listed in the text does not cleanly map to labels in the schema. For example, an “intradural tumor” develops within the spinal cord, thus does not cleanly map to our schema label of “Spine, vertebral column” as this has a connotation of a tumor developing in bone tissue- although for our purpose we find this mapping acceptable. |

||

Note that report text details and exact wording have been modified for brevity and to further enhance anonymization.

Final Performance & Stopping Criteria

Gold-label set creation and refinement process was concluded upon reaching zero major manual annotation errors, a near-zero rate of minor annotation discrepancies, a major LLM error rate near or below 1%, and an elimination of most schema errors, except those arising from complex cases deemed requiring human review. To quickly assess LLM backbone interoperability, we compared results from GPT-4o, Llama 3.3 70B Instruct,45 and Qwen2.5 72B Instruct46 (running locally) to the final gold-labels (plus concatenated specimen/block/test name when applicable) using the ROUGE-L metric, which measures the longest common subsequence between text pairs.

Internal Application & Validation

Our final pipeline was run on the free text portion (final diagnosis, ancillary studies, comments, addendums) of 3,520 internal pathology reports containing evidence of renal tumors spanning April 2019-November 2024 [SFigure 1]. Of these reports, 2,297 utilized additional discrete EMR fields, corresponding to CAP kidney resection/biopsy and internal metastatic RCC pathology templates, that could be pulled separately from the report text. This templated discrete field data was then used to cross reference the LLM outputs for metastatic RCC status and the presence or absence of six kidney tumor subtypes- clear cell RCC, chromophobe RCC, papillary RCC, clear cell papillary renal cell tumor (CCPRCT), TFE3-rearranged RCC, and TFEB-altered RCC. Discrepancies were manually reviewed using the free-text report as ground truth. For TFE3 and TFEB related RCC, the templated data primarily used the histologies from CAP Kidney 4.1.0.0, in which the term “MiT family translocation RCC” can refer to either, thus requiring the LLM to infer the proper updated subtype.

To attempt scalable validation of LLM extracted histology and IHC results across all reports, including those with no available templated data, we selected all extracted subparts/specimens with a single histology of the above six for which IHC results were also extracted. We then assessed consistency of the histological subtype with the expected IHC/FISH pattern for 5 common markers used to differentiate RCC subtypes; CA-IX, CD117, Racemase, TFE3, and TFEB.47 Unexpected findings were then subject to manual review of the report text.

Assessing Interoperability

Ease of accommodation to different clinical domains was evaluated using TCGA Breast Invasive Carcinoma pathology reports that had undergone image to optical character recognition (OCR) processing and had corresponding tabular clinical data available.48,49 Specifically, we attempted to extract results for HER2 (both FISH and IHC separately), progesterone receptor (PR), and estrogen receptor (ER).49,50 We restricted the reports to those containing the words “immunohistochemistry” and “HER2” to ensure IHC results were present in the OCR processed text as well as to reduce manual review burden. To gauge generalization, only the IHC/FISH schema was modified, and iterative improvements were performed only until most schema issues were reduced. All external and internal validation was done using GPT-4o 2025–08-06 via Azure, and across all tasks a temperature of 0 was used.

Results

Gold-Label Iterations

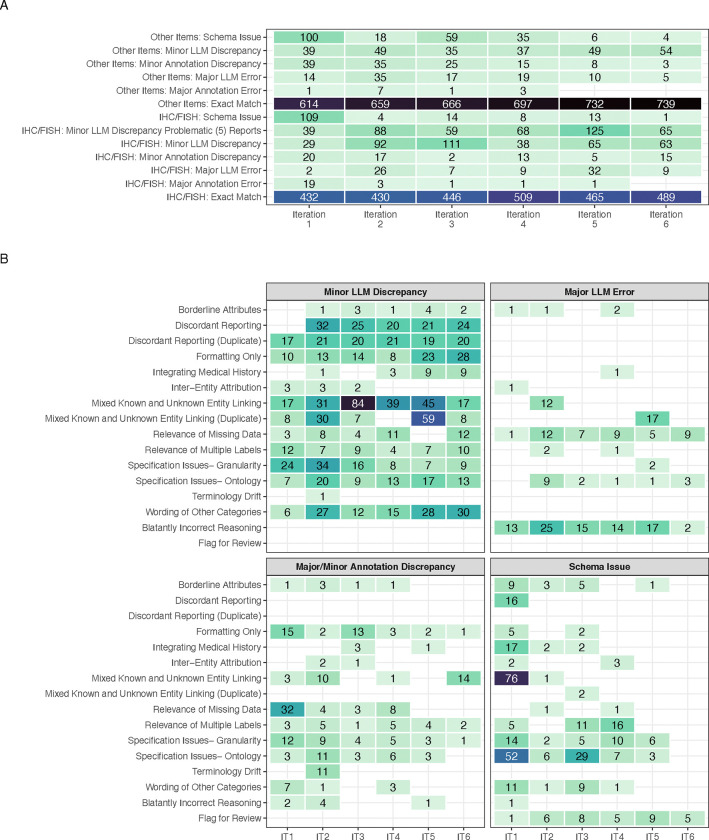

After six iterative rounds, stopping criteria were met. The final gold-label set comprised 1,413 distinct entities. This included 152 diagnoses for each report, 651 specimen/subpart-level labels (histology, procedures, and anatomical sites), and 610 IHC/FISH results. By the final iteration no major annotation errors were found and only 14 major LLM errors were noted-amounting to 0.99% of total gold-label entities. Importantly, schema errors outside of flagging for review were eliminated (Figure 3A) [SFigures 2–4]. Notably, in the last three iterations, the majority of minor IHC discrepancies were produced by only 5 reports (denoted “problematic reports”). Many discrepancies arose from difficulties in entity linking, as well as the following: variations in the wording of “Other” categories, formatting only mistakes, and mismatches due to discordant reporting of specimen names in outside consultation reports (e.g. specimen 1 vs UTSW convention of specimen A) [Figure 3B]. Notes on fluctuating error numbers along with additional comments on major updates to the prompts/schema between iterations, are documented in STable 2.

Figure 3:

(A) Error/discrepancy source, severity, and entity type across iterations. Counts of 0 are left blank. Column totals are not equal across all iterations due to duplicate IHC/FISH entities and variations in missingness (B) Error/discrepancy contexts by source and severity across iterations (IT). Counts of 0 are left blank. Due to the lower number of major annotation errors, they have been grouped with minor annotation discrepancies for ease of visualization. For all panels, the fill color scale is maintained with a maximum at 84 and minimum of 1.

These results demonstrate continued difficulty in IHC/FISH extraction, however minor LLM discrepancy rates are quite conservative- for IHC any discrepancy in the full linking of the components (specimen, block, test name, and test result), standardization of the test name, or utilization of the structured result vocabulary causes the entire entry to be counted as a minor error.

The workflow proved flexible across LLM backbones- in comparing LLM outputs to the final gold-labels mean ROUGE-L scores of 0.93, 0.91, and 0.87 were obtained for GPT-4o 2024–08-06, Qwen-2.5 72B Instruct, and Llama 3.3 70B respectively [SFigure 5].

Internal Application & Validation

Cross reference of GPT-4o 2024–08-06 output to structured data from templated EMR fields was available for 2,297 reports. For these, a macro-averaged F1 score of 0.99 for identifying the six kidney tumor subtypes and an F1 score of 0.97 for identifying metastatic RCC was obtained using Table 2.1. In 27 instances, the pipeline was able to accurately provide updates to the pre-existing templated data; STable 3.1. Conversion from historical TFEB/TFE3 terminology to updated terms was also successful in all instances.

Table 2.1:

Consistency Between Preexisting Data and Extracted Histology and Diagnosis of Metastatic RCC

| Clear cell RCC | Actual | ||||

| Absent | Contains | ||||

| Predicted | Absent | 576+1† | 32 | F1: 0.99 | |

| Contains | 4 | 1671+13‡ | |||

| Papillary RCC | Actual | ||||

| Absent | Contains | ||||

| Predicted | Absent | 2061+1 | 2 | F1: 0.99 | |

| Contains | 0 | 232+1 | |||

| Clear cell papillary renal cell tumor (CCPRCT) | Actual | ||||

| Absent | Contains | ||||

| Predicted | Absent | 2247 | 0 | F1: 0.98 | |

| Contains | 2 | 46+2 | |||

| Chromophobe RCC | Actual | ||||

| Absent | Contains | ||||

| Predicted | Absent | 2188 | 1 | F1: 0.99 | |

| Contains | 0 | 105+3 | |||

| TFE3-Rearranged RCC ‡ | Actual | ||||

| Absent | Contains | ||||

| Predicted | Absent | 2289 | 0 | F1: 1 | |

| Contains | 0 | 7+1 | |||

| TFEB-Altered RCC ‡ | Actual | ||||

| Absent | Contains | ||||

| Predicted | Absent | 2287 | 0 | F1: 1 | |

| Contains | 0 | 6+4 | |||

| Metastatic RCC | Actual | ||||

| Metastatic RCC | Non-Metastatic | ||||

| Predicted | Metastatic RCC | 230+1 | 14 | F1: 0.97 | |

| Non-Metastatic | 2 | 2050 | |||

The digit after the plus here indicates the number of instances where after review of the report free text, the LLM provided an updated label (See STable 3.1 for details)

TFE3 was additionally matched to the older terminology- Xp11 translocation RCC. Similarly TFEB was matched to t(6,11) translocation RCC. These terms were used in previous versions of CAP kidney cancer templates.

From the 3,520 total reports, 2,464 subparts/specimens were identified to contain any of the histologies of interest. Of these, 1,906 were identified to have only a single histology and corresponding IHC results for the same subpart (SFigure 1). The pipeline showed a high degree of consistency, for example, 87/87 CD117 tests on specimens with chromophobe RCC were positive, and accurate extraction of the CA-IX “cup-like” expected staining pattern for CCPRCT was demonstrated; Table 2.2. The two “box-like” results found for CCPRCT corresponded to two tumors in a single report, wherein the LLM was consistent with the report text. The case was subsequently reviewed and found to have a “cup-like” pattern and a correction was issued [STable 3.2].

Table 2.2:

Consistency Between Extracted Histology and IHC/FISH Results

| Chromophobe RCC | Papillary RCC | CCPRCT | Clear cell RCC | TFE3 Rearranged RCC | TFEB Altered RCC | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total Number of Specimens † | 84 | 119 | 62 | 1630 | 6 | 5 | |

| CAIX | Expected | Negative | Focal/Patchy Positive or Negative | Positive (Cup-Like) | Positive or Positive (Box-Like) | Negative | Negative |

| Positive (Cup-Like) | 0 | 1^ | 61 | 3^ | 0 | 0 | |

| Positive (Box-Like) | 0 | 0 | 2* | 164 | 0 | 0 | |

| Focal/Patchy Positive | 0 | 22 | 0 | 6* | 0 | 1 | |

| Other Positive‡ | 0 | 6 | 3 | 548 | 0 | 0 | |

| Negative | 24 | 15 | 0 | 2* | 5 | 3 | |

| CD117 | Expected | Positive | Negative | Negative | Negative | Negative | Negative |

| Positive | 87 | 0 | 0 | 1^ | 0 | 1* | |

| Negative | 0 | 4 | 6 | 26 | 2 | 3 | |

| Racemase | Expected | Negative | Positive | Negative | Mixed | Mixed | Mixed |

| Focal/Patchy Positive | 0 | 2 | 0 | 7 | 0 | 0 | |

| Positive/Diffuse Positive | 2* | 99 | 0 | 9 | 1 | 2 | |

| Negative | 3 | 0 | 13 | 4 | 0 | 0 | |

| TFE3 | Expected | Negative | Negative | Negative | Negative | Rearranged | Negative |

| Rearranged | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 6 | 0 | |

| Negative | 2 | 7 | 0 | 6 | 0 | 4 | |

| TFEB | Expected | Negative | Negative | Negative | Negative | Negative | Rearranged/Amplified |

| Rearranged/Amplified | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 5 | |

| Negative | 2 | 6 | 0 | 4 | 6 | 0 | |

Single specimens may have multiple tests, thus column totals may be higher than the number of specimens

Includes “Positive” alone, or with other modifiers not explicitly Focal/Patchy, Cup-Like, or Box-Like

Report reviewed and the LLM corrected a typographic mistake (STable3.2 for details)

Report reviewed and the LLM found to have made a mistake (STable3.2 for details)

Assessing Interoperability

Of the 757 TCGA available breast cancer reports, 53 contained the words “immunohistochemistry” and “HER2” in the OCR text. Only three iterations were required to greatly minimize schema errors. The pipeline (with GPT-4o 2024–08-06) achieved 89% agreement on HER2 (IHC and FISH), PR, and ER status when compared to the curated TCGA clinical data (9 results in the clinical data that did not appear in report text were excluded from agreement calculations) [STable 4]. Notably, after reviewing report texts, what at first appeared to be an LLM false positive was instead found to reflect the ambiguity of whether ER staining of 1–9% is considered negative or a heterogeneous “low positive” category.51

Discussion

This study demonstrates that high accuracy in automated pathology report information extraction with large language models (LLMs) is possible but hinges on careful task definition and refinement. Although our pipeline yielded strong performance—demonstrating, for instance, a macro-averaged F1 score of 0.99 on identifying important RCC histological subtypes—our experience suggests that the questions we needed to ask to arrive at this performance were more significant and broader application than the performance metrics or workflow technicalities.

It became clear that the model’s success depended heavily on the clarity and depth of our schema and prompt instructions. Thus, a multidisciplinary team with domain expertise in NLP and LLMs, downstream statistical analysis, and clinical pathology became instrumental in achieving success. Our iterative approach to schema definition and revision (Table 1 and STable 1) revealed a spectrum of challenges that went far beyond entity detection and linking. Particularly, how clinical history and ambiguity, proper specification in instructions, and complexities in reports and desired entities, must all be carefully managed to ensure alignment with researcher goals.

Medical History and Ambiguity

Mirroring issues faced by pathologists when encountering uncertainty, managing the integration of medical history was a persistent challenge, particularly when ambiguity was present. Assessing how much and what kinds of information to infer from broader medical histories required careful collaboration between data scientists and clinicians. For example, the pathologist on our team clarified that terms like “consistent with” or “compatible with” often carry more conclusive meaning in than in general parlance, resulting in adjustments to instructions regarding the level certainty provided by these terms (STable 1.1).52 Furthermore, we found that well-meaning instructions like “focus on the current specimen in the report, not past medical history” led to instances of “malicious compliance” where the LLM followed our instructions too literally- resulting in important information being discarded. Rectifying this required reflection on how instructions would be interpreted, prompting us to add greater specificity to our instructions (Table 1.1, STable 1.2).

In such contexts review of the LLM’s “reasoning” output proved vital, as we could peer into the steps that led to certain “decisions” being made. For example, in one report containing carcinoma of unknown origin from a lymph node biopsy, the LLM incorrectly justified its choice of metastatic RCC based on the presence of “malignant cells outside the kidney”. This led us to add further instructions clarifying that an RCC histology must be confirmed in order to utilize the metastatic RCC diagnosis.

Specification

Task specification proved to be a significant undertaking, with numerous “grey areas” requiring careful consideration and team consensus. We found that balancing the amount and type of information extracted was particularly important—a trade-off between completeness and specificity (STable 1.4–5). This was particularly evident in entities that commonly required multiple labels, such as anatomical sites (Table 1.3). Furthermore, understanding our preferred level of granularity necessitated some trial and error. For example, determining the appropriate level of detail for IHC results required a shift from an exhaustive list of all possible results to a more structure vocabulary with separate dimensions for status, intensity, extent, and pattern (Table 1.4) allowing for more flexible and concise representations. The level of detail afforded by our pipeline should allow for accelerated retrospective studies of biomarkers, such as Ki-67 (which we capture as a proliferative index), which can be systematically evaluated for their role in in the management of various contexts and RCC subtypes.53

Further specification issues arose regarding the ontology of anatomical sites, leading to nuanced discussions about how the data would be used in downstream analysis. For example, in our particular use cases, a “peripancreatic mass” should not be interpreted as a metastasis in the pancreas itself (Table 1.5). This distinction is important for determining surgical resection procedures and prognosis.54 We also encountered issues with ontological overlap of labels—situations where multiple labels could be considered correct— requiring consideration of prioritization. A common occurrence of this was the primary status result for the IHC test BAP-1, which was described with either or both of “Positive” and “Intact” (STable 1.6).55 Additional consideration was needed in determining if “Other- fill in the blank categories” should be used in our workflow, as these open ended fields necessitate higher levels of manual review due to the difficulty of matching the LLM output verbatim to gold-label annotations (STable 1.7). However, the desire to not force potentially borderline or complex entities into discrete categories motivated the inclusion of this open-ended option. Further difficulties, such as handling changes in terminology, gauging the relevance of missing data, and delineating local vs distant lymph node involvement are detailed in the supplement (STables 1.8–11).

Complexity

Report complexities, particularly in instances where the block or specimen used for an IHC test is not identified, were and remain a significant source of errors. For instance, when multiple specimens shared the same histology, any IHC test lacking a specified specimen caused the LLM to duplicate results across all similarly histological specimens (Table 1.2). While adding illustrative examples to the prompts helped mitigate this issue, it also underscored the importance of precision in reporting. Comparable challenges arose with discordant reporting conventions, especially in outside consultations that used different naming systems (STable 1.3), highlighting both the benefits and the difficulties of data harmonization across institutions.

Despite these mitigations, as shown in Figure 3A, a small subset of reports featuring these complexities continued to generate numerous discrepancies. Introducing a pipeline step to flag such reports for review could substantially reduce the noise they produce and remains a key goal moving forward. Moreover, the increase in entity linking discrepancies observed between iterations 4 and 5 demonstrates how modifying instructions can lead to large, unexpected side effects. In that specific instance, the instructions were altered to use the aforementioned structured vocabulary for IHC results, and inadvertently resulted in a higher rate of duplicated results. To address this, we added an additional example, illustrating the proper response format in such cases, to the IHC standardization instructions for iteration six [STable2].

Internal Application, Validation, & Generalizability

Cross reference of our pipeline output with pre-existing templated data proved successful, however demonstrated areas for improvement (Table 2.1). A brief review of the mistakes showed continued difficulty with integrating medical history; of the 32 missing clear cell histologies, 28 were labeled with unclassified RCC stemming from an improper utilization of a patient’s prior history of clear cell RCC [STable3.1]. The lower performance in diagnosing metastatic RCC was also primarily attributable to false positives due to misinterpreting medical history (6), local tumor extension (5), and differentiation of regional vs distant lymph node metastasis (3). These results often occur in reports with high complexity and ambiguity, and furthers the need for pipeline steps to tag complex cases for human review. Finally, through cross referencing extracted histology vs IHC test results, the pipeline showed high utility for extracting precise results- and even helped identify the typographical mistake mentioned in the results; Table 2.2 [STable 3.2]. 53

In terms of generalizability, while all development was done with GPT-4o, high ROUGE-L scores were obtained with the open-weight models Llama 3.345 and Qwen2.546, suggesting that well-structured instructions and robust schema design can translate across LLMs. We further demonstrate adaptability of the prompt template approach to new domains through our external validation set. Adapting the pipeline to this new task required only three iterations to the IHC/FISH schema, crucially with input from clinicians, without any changes to the core prompt templates.

Limitations and Future Directions

We do acknowledge that our distinction between schema issues, major, and minor errors relied on contextual interpretation and our specific use case, thus we do not place too much emphasis on the “performance numbers” of our pipeline. Rather, we argue that pipelines be interpreted more holistically by the clinical significance of committed errors and their potential impact on downstream analysis. These interpretations could be different for different groups; what constitutes a serious “major” error in one research or clinical setting might be a “minor” one elsewhere.

Furthermore, we found ourselves continually adding “one-off” rules to the schema instructions, risking the potential for unbounded complexity and reduced generalizability. To mitigate this, we aimed to keep our instructions as generalizable as possible. For example, instead of adding a rule only specifically mentioning “peripancreatic” masses, we added general instruction to consider “directional terms” when determining anatomical sites, with “peripancreatic” as only one such example (Table 1.5). Also, our iterative approach was time-intensive; each round required not only LLM re-prompting but also comprehensive human review. One might ask whether an end-to-end manual annotation followed by a traditional fine-tuned transformer model would have been easier. However, such an approach may have still demanded extensive labeling,4 no guarantee of easily handling both the wide variety and complexity of “error inducing” contexts that we encountered, and would not have spurred as much insight into refining our information extraction goals. Moreover, generative LLM technology is evolving rapidly, and our flexible, prompt-based pipeline should remain more adaptable to new capabilities or model upgrades than a static, fine-tuned architecture.

Conclusions

In summary, our LLM-based pipeline for pathology report information extraction highlights not only strong performance metrics, but also the intricate processes required to achieve them. Our experience illustrates the importance of thoroughly understanding one’s intentions and goals for information extraction, and how collaboration between domain experts-and even the LLMs themselves- are crucial to this process. By documenting these complexities, we aim to provide a set of generalizable considerations that can inform future pipelines. As generative AI continues to mature, flexible, human-in-the-loop strategies may prove essential to ensuring workflows remain grounded in real-world clinical objectives.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments.

This work was supported by the NIH sponsored Kidney Cancer SPORE grant (P50CA196516) and endowment from Jan and Bob Pickens Distinguished Professorship in Medical Science and Brock Fund for Medical Science Chair in Pathology.

Footnotes

Disclosure of Interests.

Azure compute credits were provided to Dr. Jamieson by Microsoft as part of the Accelerating Foundation Models Research initiative.

The authors have no otherwise competing interests to declare that are relevant to the content of this article.

References

- 1.Li I, Pan J, Goldwasser J, et al. Neural Natural Language Processing for unstructured data in electronic health records: A review. Comput Sci Rev. 2022;46:100511. doi: 10.1016/j.cosrev.2022.100511 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zozus MN, Pieper C, Johnson CM, et al. Factors Affecting Accuracy of Data Abstracted from Medical Records. Faragher EB, ed. PLOS ONE. 2015;10(10):e0138649. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0138649 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brundin-Mather R, Soo A, Zuege DJ, et al. Secondary EMR data for quality improvement and research: A comparison of manual and electronic data collection from an integrated critical care electronic medical record system. J Crit Care. 2018;47:295–301. doi: 10.1016/j.jcrc.2018.07.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sushil M, Kennedy VE, Mandair D, Miao BY, Zack T, Butte AJ. CORAL: Expert-Curated Oncology Reports to Advance Language Model Inference. NEJM AI. 2024;1(4). doi: 10.1056/AIdbp2300110 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jee J, Fong C, Pichotta K, et al. Automated real-world data integration improves cancer outcome prediction. Nature. 2024;636(8043):728–736. doi: 10.1038/s41586-024-08167-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sedlakova J, Daniore P, Horn Wintsch A, et al. Challenges and best practices for digital unstructured data enrichment in health research: A systematic narrative review. Sarmiento RF, ed. PLOS Digit Health. 2023;2(10):e0000347. doi: 10.1371/journal.pdig.0000347 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Xu H, Anderson K, Grann VR, Friedman C. Facilitating cancer research using natural language processing of pathology reports. Stud Health Technol Inform. 2004;107(Pt 1):565–572. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hripcsak G, Friedman C, Alderson PO, DuMouchel W, Johnson SB, Clayton PD. Unlocking clinical data from narrative reports: a study of natural language processing. Ann Intern Med. 1995;122(9):681–688. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-122-9-199505010-00007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Alsentzer E, Murphy JR, Boag W, et al. Publicly Available Clinical BERT Embeddings. Published online 2019. doi: 10.48550/ARXIV.1904.03323 [DOI]

- 10.Yang X, Chen A, PourNejatian N, et al. A large language model for electronic health records. Npj Digit Med. 2022;5(1):194. doi: 10.1038/s41746-022-00742-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rasmy L, Xiang Y, Xie Z, Tao C, Zhi D. Med-BERT: pretrained contextualized embeddings on large-scale structured electronic health records for disease prediction. Npj Digit Med. 2021;4(1):86. doi: 10.1038/s41746-021-00455-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lee J, Yoon W, Kim S, et al. BioBERT: a pre-trained biomedical language representation model for biomedical text mining. Wren J, ed. Bioinformatics. 2020;36(4):1234–1240. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btz682 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Peng Y, Yan S, Lu Z. Transfer Learning in Biomedical Natural Language Processing: An Evaluation of BERT and ELMo on Ten Benchmarking Datasets. Published online 2019. doi: 10.48550/ARXIV.1906.05474 [DOI]

- 14.Su P, Vijay-Shanker K. Investigation of improving the pre-training and fine-tuning of BERT model for biomedical relation extraction. BMC Bioinformatics. 2022;23(1):120. doi: 10.1186/s12859-022-04642-w [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Li Y, Wehbe RM, Ahmad FS, Wang H, Luo Y. A comparative study of pretrained language models for long clinical text. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2023;30(2):340–347. doi: 10.1093/jamia/ocac225 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Brown TB, Mann B, Ryder N, et al. Language Models are Few-Shot Learners. Published online 2020. doi: 10.48550/ARXIV.2005.14165 [DOI]

- 17.Liu H, Ning R, Teng Z, Liu J, Zhou Q, Zhang Y. Evaluating the Logical Reasoning Ability of ChatGPT and GPT-4. Published online 2023. doi: 10.48550/ARXIV.2304.03439 [DOI]

- 18.Nori H, King N, McKinney SM, Carignan D, Horvitz E. Capabilities of GPT-4 on Medical Challenge Problems. Published online 2023. doi: 10.48550/ARXIV.2303.13375 [DOI]

- 19.Singhal K, Azizi S, Tu T, et al. Large language models encode clinical knowledge. Nature. 2023;620(7972):172–180. doi: 10.1038/s41586-023-06291-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Agrawal M, Hegselmann S, Lang H, Kim Y, Sontag D. Large Language Models are Few-Shot Clinical Information Extractors. Published online 2022. doi: 10.48550/ARXIV.2205.12689 [DOI]

- 21.Hu Y, Chen Q, Du J, et al. Improving large language models for clinical named entity recognition via prompt engineering. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2024;31(9):1812–1820. doi: 10.1093/jamia/ocad259 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sivarajkumar S, Kelley M, Samolyk-Mazzanti A, Visweswaran S, Wang Y. An Empirical Evaluation of Prompting Strategies for Large Language Models in Zero-Shot Clinical Natural Language Processing: Algorithm Development and Validation Study. JMIR Med Inform. 2024;12:e55318. doi: 10.2196/55318 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Peng C, Yang X, Chen A, et al. Generative large language models are all-purpose text analytics engines: text-to-text learning is all your need. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2024;31(9):1892–1903. doi: 10.1093/jamia/ocae078 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Burford KG, Itzkowitz NG, Ortega AG, Teitler JO, Rundle AG. Use of Generative AI to Identify Helmet Status Among Patients With Micromobility-Related Injuries From Unstructured Clinical Notes. JAMA Netw Open. 2024;7(8):e2425981. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2024.25981 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hu D, Liu B, Zhu X, Lu X, Wu N. Zero-shot information extraction from radiological reports using ChatGPT. Int J Med Inf. 2024;183:105321. doi: 10.1016/j.ijmedinf.2023.105321 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Huang J, Yang DM, Rong R, et al. A critical assessment of using ChatGPT for extracting structured data from clinical notes. Npj Digit Med. 2024;7(1):106. doi: 10.1038/s41746-024-01079-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Johnson B, Bath T, Huang X, et al. Large language models for extracting histopathologic diagnoses from electronic health records. Published online November 28, 2024. doi: 10.1101/2024.11.27.24318083 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Le Guellec B, Lefèvre A, Geay C, et al. Performance of an Open-Source Large Language Model in Extracting Information from Free-Text Radiology Reports. Radiol Artif Intell. 2024;6(4):e230364. doi: 10.1148/ryai.230364 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Liu F, Li Z, Zhou H, et al. Large Language Models Are Poor Clinical Decision-Makers: A Comprehensive Benchmark. Published online April 25, 2024. doi: 10.1101/2024.04.24.24306315 [DOI]

- 30.Omiye JA, Gui H, Rezaei SJ, Zou J, Daneshjou R. Large Language Models in Medicine: The Potentials and Pitfalls: A Narrative Review. Ann Intern Med. 2024;177(2):210–220. doi: 10.7326/M23-2772 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sushil M, Zack T, Mandair D, et al. A comparative study of large language model-based zero-shot inference and task-specific supervised classification of breast cancer pathology reports. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2024;31(10):2315–2327. doi: 10.1093/jamia/ocae146 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wang LL, Otmakhova Y, DeYoung J, et al. Automated Metrics for Medical Multi-Document Summarization Disagree with Human Evaluations. Proc Conf Assoc Comput Linguist Meet. 2023;2023:9871–9889. doi: 10.18653/v1/2023.acl-long.549 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wornow M, Xu Y, Thapa R, et al. The shaky foundations of large language models and foundation models for electronic health records. Npj Digit Med. 2023;6(1):135. doi: 10.1038/s41746-023-00879-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tang L, Sun Z, Idnay B, et al. Evaluating large language models on medical evidence summarization. Npj Digit Med. 2023;6(1):158. doi: 10.1038/s41746-023-00896-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Reichenpfader D, Müller H, Denecke K. A scoping review of large language model based approaches for information extraction from radiology reports. Npj Digit Med. 2024;7(1):222. doi: 10.1038/s41746-024-01219-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tian S, Jin Q, Yeganova L, et al. Opportunities and challenges for ChatGPT and large language models in biomedicine and health. Brief Bioinform. 2023;25(1):bbad493. doi: 10.1093/bib/bbad493 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Fleming SL, Lozano A, Haberkorn WJ, et al. MedAlign: A Clinician-Generated Dataset for Instruction Following with Electronic Medical Records. Published online 2023. doi: 10.48550/ARXIV.2308.14089 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zhong T, Liu Z, Pan Y, et al. Evaluation of OpenAI o1: Opportunities and Challenges of AGI. Published online 2024. doi: 10.48550/ARXIV.2409.18486 [DOI]

- 39.Goel A, Gueta A, Gilon O, et al. LLMs Accelerate Annotation for Medical Information Extraction. Published online 2023. doi: 10.48550/ARXIV.2312.02296 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Murugan P. Protocol for the Examination of Resection Specimens from Patients with Renal Cell Carcinoma. Published online June 2024. https://documents.cap.org/protocols/Kidney_4.2.0.0.REL_CAPCP.pdf

- 41.Murugan P. Protocol for the Examination of Biopsy Specimens from Patients with Renal Cell Carcinoma. Published online June 2024. https://documents.cap.org/protocols/Kidney.Bx_4.2.0.0.REL_CAPCP.pdf

- 42.Prompt flow. https://github.com/microsoft/promptflow?tab=readme-ov-file

- 43.Wei J, Wang X, Schuurmans D, et al. Chain-of-Thought Prompting Elicits Reasoning in Large Language Models. Published online 2022. doi: 10.48550/ARXIV.2201.11903 [DOI]

- 44.OpenAI, Hurst A, Lerer A, et al. GPT-4o System Card. Published online 2024. doi: 10.48550/ARXIV.2410.21276 [DOI]

- 45.Grattafiori A, Dubey A, Jauhri A, et al. The Llama 3 Herd of Models. Published online 2024. doi: 10.48550/ARXIV.2407.21783 [DOI]

- 46.Yang A, Yang B, Hui B, et al. Qwen2 Technical Report. Published online 2024. doi: 10.48550/ARXIV.2407.10671 [DOI]

- 47.Kim M, Joo JW, Lee SJ, Cho YA, Park CK, Cho NH. Comprehensive Immunoprofiles of Renal Cell Carcinoma Subtypes. Cancers. 2020;12(3):602. doi: 10.3390/cancers12030602 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Gao J, Aksoy BA, Dogrusoz U, et al. Integrative Analysis of Complex Cancer Genomics and Clinical Profiles Using the cBioPortal. Sci Signal. 2013;6(269). doi: 10.1126/scisignal.2004088 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kefeli J, Tatonetti N. TCGA-Reports: A machine-readable pathology report resource for benchmarking text-based AI models. Patterns. 2024;5(3):100933. doi: 10.1016/j.patter.2024.100933 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ciriello G, Gatza ML, Beck AH, et al. Comprehensive Molecular Portraits of Invasive Lobular Breast Cancer. Cell. 2015;163(2):506–519. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.09.033 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Makhlouf S, Althobiti M, Toss M, et al. The Clinical and Biological Significance of Estrogen Receptor-Low Positive Breast Cancer. Mod Pathol. 2023;36(10):100284. doi: 10.1016/j.modpat.2023.100284 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Oien KA, Dennis JL. Diagnostic work-up of carcinoma of unknown primary: from immunohistochemistry to molecular profiling. Ann Oncol. 2012;23:x271–x277. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mds357 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Zhao J, Ding X, Peng C, et al. Assessment of Ki-67 proliferation index in prognosis prediction in patients with nonmetastatic clear cell renal cell carcinoma and tumor thrombus. Urol Oncol Semin Orig Investig. 2024;42(1):23.e5-23.e13. doi: 10.1016/j.urolonc.2023.11.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Lavu H, Yeo CJ. Metastatic renal cell carcinoma to the pancreas. Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2011;7(10):699–700. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Kapur P, Rajaram S, Brugarolas J. The expanding role of BAP1 in clear cell renal cell carcinoma. Hum Pathol. 2023;133:22–31. doi: 10.1016/j.humpath.2022.07.022 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.